Validating Thermodynamic Stability Through Phase Diagram Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for employing phase diagram analysis to validate thermodynamic stability in pharmaceutical development.

Validating Thermodynamic Stability Through Phase Diagram Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for employing phase diagram analysis to validate thermodynamic stability in pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of thermodynamics and phase behavior, explores advanced methodological applications including empirical phase diagrams and machine learning, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes robust validation protocols. By synthesizing current research and practical case studies, this guide aims to enhance the efficiency of developing stable, safe, and effective drug formulations, from early discovery to regulatory submission.

The Essential Role of Thermodynamic Stability and Phase Behavior in Drug Design

The interplay between Gibbs free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) forms the foundational framework for understanding molecular stability and interaction across scientific disciplines. These parameters are connected by the fundamental equation: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, where T is the absolute temperature. This relationship dictates the spontaneity of molecular processes, with negative ΔG values indicating favorable reactions. In molecular interactions, these thermodynamic parameters collectively determine binding affinity, specificity, and stability under varying environmental conditions.

The significance of these driving forces extends from biological systems to materials science. In protein-ligand interactions, thermodynamic trade-offs enable adaptability across evolutionary timeframes, including rapid viral evolution [1]. In materials science, accurate prediction of compound stability through these parameters is essential for discovering new inorganic compounds and functional materials [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how ΔG, ΔH, and TΔS govern molecular interactions across diverse systems, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols.

Comparative Analysis of Thermodynamic Parameters Across Molecular Systems

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameter Comparison Across Molecular Systems

| System Type | Typical ΔG Range (kJ/mol) | Enthalpy (ΔH) Contribution | Entropy (TΔS) Contribution | Primary Stabilizing Forces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand Binding | -20 to -50 | Variable: Can be favorable (negative) or unfavorable (positive) | Often unfavorable at interface but favorable from solvent effects | Hydrogen bonding, van der Waals, hydrophobic effect |

| Antibody-Antigen Interactions | -25 to -60 | Can be strongly negative for high-affinity antibodies | Can be unfavorable due to reduced flexibility | Shape complementarity, electrostatic interactions |

| Inorganic Compounds (Stable) | <-50 (per atom) | Dominates stability in crystalline materials | Minor contribution at room temperature | Covalent/ionic bonding, lattice energy |

| Polymer Crystallization | Negative but small per repeat unit | Exothermic (negative ΔH) during crystallization | Entropy-driven melting at high temperature | Chain folding, van der Waals interactions |

The compensation between enthalpy and entropy represents a crucial phenomenon across molecular systems. In protein-ligand interactions, entropy-enthalpy compensation enables proteins to maintain optimal binding affinity despite temperature fluctuations [1]. This compensation mechanism creates a fundamental trade-off where favorable enthalpy changes often accompany unfavorable entropy changes, and vice versa. Evolutionary studies reveal that ancient proteins likely exhibited entropically favored, flexible binding modes, while modern proteins increasingly rely on enthalpically driven specificity [1].

In synthetic polymer systems like poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), thermodynamic parameters determine crystallinity degrees that directly impact material performance. The equilibrium melting enthalpy (ΔH⁰) for P3HT has been measured at approximately 68 J·g⁻¹, with this thermodynamic parameter serving as essential for quantifying crystallinity in semiconducting polymer systems [3].

Experimental Methodologies for Thermodynamic Parameter Determination

Phase Diagram Analysis for Inorganic Systems

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Thermodynamic Parameter Determination

| Methodology | Measured Parameters | System Applications | Key Instrumentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) | Phase transition temperatures, melting points | Cr-Ta binary system, inorganic compounds | Differential Thermal Analyzer (DTA) |

| Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA) | Phase equilibrium compositions | High-temperature materials, binary alloys | Field-Emission EPMA with WDS |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Direct ΔG, ΔH, KD, TΔS | Protein-ligand, antibody-antigen interactions | Microcalorimetry systems |

| Hoffman-Weeks Extrapolation | Equilibrium melting temperature (Tm⁰) | Semicrystalline polymers | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) |

The CALculation of PHAse Diagrams (CALPHAD) technique provides a powerful computational framework for thermodynamic assessment of complex systems. Researchers applying this method to the Cr-Ta binary system have determined phase equilibria at temperatures up to 2100°C, deriving self-consistent thermodynamic parameters that accurately predict phase behavior [4]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Alloy Preparation: Creating homogeneous Cr-Ta alloys with carefully controlled compositions

- Heat Treatment: Application of specific temperature regimes to establish equilibrium states

- Composition Profiling: Using wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (WDS) with field-emission electron probe microanalysis to determine phase boundaries

- Thermal Analysis: Employing differential thermal analysis (DTA) to identify invariant reaction temperatures

- Parameter Optimization: Deriving self-consistent thermodynamic parameters that reproduce experimental data

This methodology revealed that single-phase regions of C14 and C15 Cr₂Ta phases extend from stoichiometry to both Cr-rich and Ta-rich sides, with phase boundaries existing at higher temperatures than previously reported [4].

Biomolecular Interaction Analysis

For antibody-antigen interactions in Western blotting applications, thermodynamic analysis provides a framework for optimizing experimental conditions. The binding affinity is quantified by the dissociation constant (KD = koff/kon), which relates directly to Gibbs free energy through ΔG = RTln(KD) [5]. Key experimental considerations include:

- Antibody Concentration: Higher concentrations increase association rates but may elevate non-specific binding

- Incubation Time: Must allow for near-equilibrium conditions without excessive experimental duration

- Temperature Control: Affects both kinetic rates and thermodynamic parameters

- Buffer Composition: Influences molecular interactions through ionic strength and pH effects

The conceptual energy landscape differentiates specific binding (characterized by deep energy wells with highly negative ΔG) from non-specific interactions (shallow energy troughs with ΔG near zero) [5]. This distinction explains why high-affinity antibodies with very negative ΔG values produce specific signals with low background in Western blotting applications.

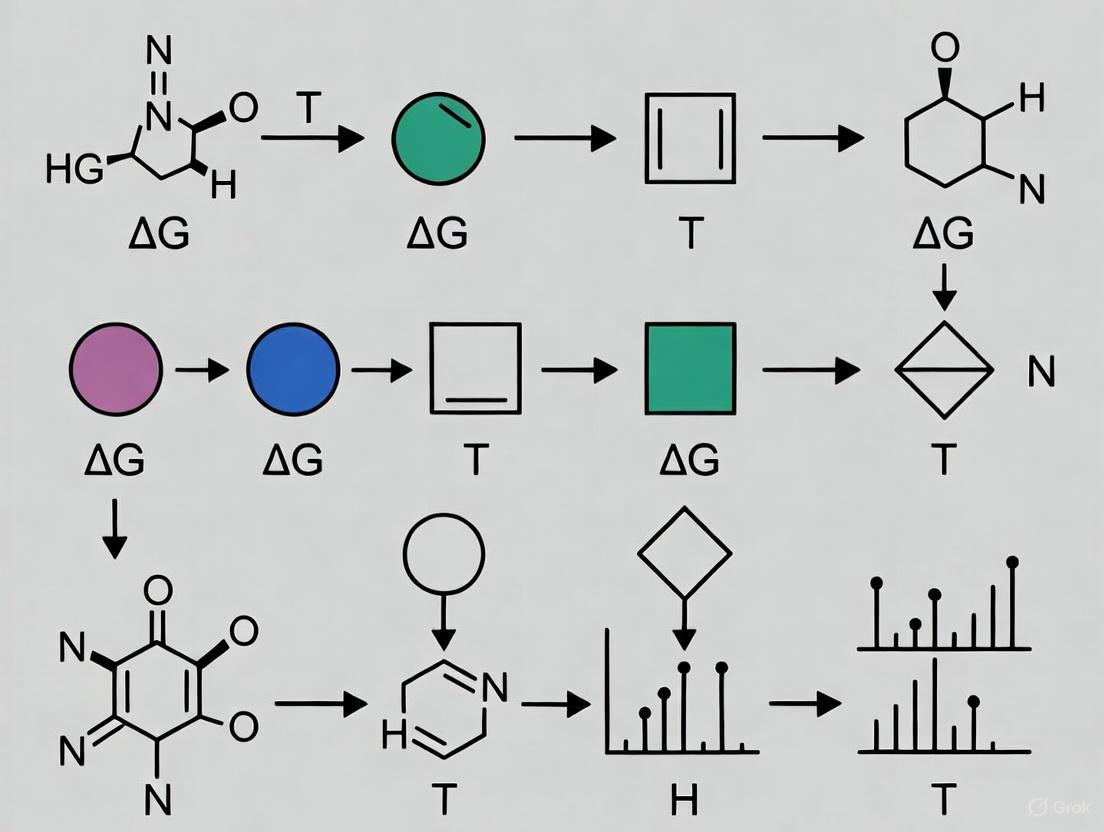

Diagram 1: Thermodynamics of molecular binding equilibrium. The relationship between kinetic constants (k_on, k_off), dissociation constant (K_D), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG) governs binding spontaneity.

Computational Approaches for Stability Prediction

Machine Learning for Compound Stability

Machine learning frameworks have emerged as powerful tools for predicting thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds. Current approaches include:

- Composition-based models: Utilize elemental composition without structural information

- Structure-based models: Incorporate geometric arrangements of atoms

- Ensemble methods: Combine multiple models to reduce inductive bias

The critical challenge in stability prediction lies in the distinction between formation energy (ΔHf) and decomposition energy (ΔHd). While ΔHf quantifies energy relative to elemental references, ΔHd represents the energy difference between a compound and competing phases in the relevant chemical space [6]. This distinction is crucial because ΔHd typically spans much smaller energy ranges (0.06 ± 0.12 eV/atom) compared to ΔHf (-1.42 ± 0.95 eV/atom), making it more sensitive to prediction errors [6].

Recent advances include the Electron Configuration models with Stacked Generalization (ECSG) framework, which integrates domain knowledge across interatomic interactions, atomic properties, and electron configurations. This approach achieves an Area Under the Curve score of 0.988 in stability prediction and demonstrates exceptional efficiency, requiring only one-seventh of the data used by existing models to achieve comparable performance [2].

Metabolic Network Thermodynamics

In metabolic engineering, thermodynamic analysis reveals fundamental design principles of microbial carbon metabolism. Key insights include:

- Energy-enzyme tradeoffs: Thermodynamic analyses reveal energy yield versus enzyme burden tradeoffs [7]

- Near-equilibrium reactions: Reactions operating near equilibrium possess spare enzyme capacity that allows rapid flux changes in response to metabolic demands [7]

- Pathway design: Thermodynamic constraints inform synthetic pathway design by identifying kinetic bottlenecks and irreversible steps

Isotope tracer methods provide experimental approaches for measuring reaction reversibility and thermodynamic parameters in living systems [7]. These computational and experimental approaches enable researchers to optimize metabolic pathways for industrial biotechnology applications.

Diagram 2: Computational frameworks for stability prediction. Ensemble methods like ECSG integrate multiple approaches to enhance prediction accuracy.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Thermodynamic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification Purpose | Application Examples | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cr-Ta Binary Alloys | Phase diagram determination | High-temperature materials research | Model system for intermetallic phase stability |

| Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) | Polymer crystallization studies | Organic semiconductor development | Model semicrystalline polymer for thermodynamics |

| [6,6]-phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) | Electron acceptor component | Polymer blend miscibility studies | Enables Flory-Huggins interaction parameter determination |

| Specific Antibodies | High-affinity binding agents | Western blotting optimization | Provide low KD values for sensitive detection |

| CALPHAD Software | Thermodynamic parameter optimization | Phase diagram calculation | Enables self-consistent thermodynamic assessment |

Understanding the interplay between ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS across molecular systems provides researchers with powerful predictive capabilities for stability assessment. Key integrative principles emerge:

First, the universal phenomenon of entropy-enthalpy compensation creates adaptive trade-offs that enhance functional resilience, observed from protein evolution to materials design. Second, accurate stability prediction requires moving beyond formation energy to consider decomposition energy within competitive compositional spaces. Third, combining computational approaches with experimental validation through phase diagram analysis creates a robust framework for thermodynamic stability assessment.

These principles unite diverse fields through shared thermodynamic language, enabling researchers to design molecular interactions with tailored stability properties for specific applications from drug development to materials synthesis. The continuing refinement of machine learning approaches, coupled with rigorous experimental methodologies, promises enhanced predictive capabilities for thermodynamic stability across the molecular sciences.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the crystalline form of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is not merely a matter of molecular arrangement but a critical determinant of drug product quality, efficacy, and safety. Polymorphism, the ability of a solid substance to exist in more than one crystalline form, introduces significant variability in critical drug properties, including solubility, dissolution rate, physical stability, and bioavailability [8]. The most stable polymorphic form is typically preferred for formulation due to its predictable long-term stability, yet metastable forms are often exploited for their enhanced solubility, despite the inherent risk of conversion to a more stable form [8]. Navigating this landscape requires a deep understanding of relative stability, guided by rigorous experimental screening and advanced computational prediction. This guide examines the pivotal role of polymorphism in drug development, underscored by comparative data and experimental protocols essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Critical Impact of Polymorphism on Drug Properties

The selection of an API's solid form is a foundational decision that reverberates throughout a drug's lifecycle. Different polymorphs, while chemically identical, possess distinct three-dimensional structures that directly influence their physicochemical properties.

- Solubility and Bioavailability: A metastable polymorph typically exhibits higher solubility and a faster dissolution rate than its stable counterpart. This can significantly enhance the rate and extent of oral absorption, a crucial factor for drugs with poor aqueous solubility. Amorphous forms, which lack long-range molecular order, tend to have the highest dissolution rate and solubility among solid forms [8]. However, this advantage is often traded off against lower physical stability.

- Physical and Chemical Stability: The most thermodynamically stable polymorph is less likely to undergo solid-form transformation during storage, ensuring consistent product performance over its shelf life. Formulating a metastable form requires careful selection of stabilizing excipients and control over processing conditions to kinetically hinder transformation [8].

- Manufacturing and Process Control: Processes such as compression, grinding, and milling during drug product manufacturing can induce polymorphic transformations [9]. For instance, the tableting process can generate sufficient pressure to trigger a form change, as demonstrated with Hydrochlorothiazide, where a transition was observed at pressures of 300-500 MPa [10]. Furthermore, exposure to solvents or humidity during manufacturing can lead to the formation of solvates or hydrates, complicating the process and potentially compromising the final product's quality.

The consequences of inadequate polymorph control are starkly illustrated by the case of ritonavir. This antiviral drug was initially marketed as a solution using a single polymorph (Form I). Months later, a new, more stable but less soluble polymorph (Form II) emerged unexpectedly in the manufacturing process, precipitating from the solution and drastically reducing the drug's bioavailability. This necessitated an emergency product withdrawal and a costly reformulation, estimated at $250 million, underscoring the immense financial and patient risks associated with unanticipated polymorphic transitions [8] [9].

Comparative Analysis of Polymorphic Properties

A direct comparison of polymorphic forms reveals how profoundly solid-state structure impacts material properties. The following table summarizes key differences between a stable polymorph, a metastable polymorph, and an amorphous form, using buspirone hydrochloride and other referenced APIs as illustrative examples.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Different API Solid Forms

| Property | Stable Polymorph | Metastable Polymorph | Amorphous Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | Highest (most negative lattice energy) | Intermediate | Lowest (thermodynamically unstable) |

| Solubility & Dissolution Rate | Lowest | Higher than stable form | Highest |

| Physical Stability | High; low risk of conversion | Low; may convert to stable form | Very low; prone to crystallization |

| Process-Induced Transformation Risk | Low | High during milling/compression | Very high |

| Example & Observed Behavior | Buspirone HCl Form 1 [11] | Buspirone HCl Form 2 (converts to Form 1 under stress) [11] | Amorphous indomethacin and clotrimazole [8] |

Quantitative data from specific case studies further elucidates these differences. For instance, a study on commercial buspirone hydrochloride samples from different suppliers found that one sample contained a mixture of Forms 1 and 2, while another consisted exclusively of Form 2. When stored under stress conditions (75% relative humidity and 50°C), Form 2 completely converted to the more thermodynamically stable Form 1 in open vials, confirming Form 1's superior stability [11]. Both polymorphs exhibited pH-dependent solubility, with the highest dissolution occurring at pH 1.2 [11].

Table 2: Experimental Data from Buspirone Hydrochloride Polymorphism Study

| Sample | Initial Form | Condition (48 days) | Final Form | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample I (India) | Mixture (Forms 1 & 2) | 50°C / 75% RH (Open Vial) | Form 1 | Complete conversion to stable form |

| Sample II (Finland) | Pure Form 2 | 50°C / 75% RH (Open Vial) | Form 1 | Complete conversion to stable form |

| Sample II (Finland) | Pure Form 2 | 50°C / 75% RH (Closed Vial) | Mixture (Forms 1 & 2) | Partial conversion, moisture-dependent |

Experimental Protocols for Solid Form Characterization

A robust polymorph screening and characterization strategy employs a suite of complementary analytical techniques. The following are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in recent literature.

Stability and Interconversion Studies

- Objective: To monitor the physical stability of polymorphs and their propensity to interconvert under stress conditions.

- Protocol: As detailed in the buspirone hydrochloride study, samples are stored in controlled climate chambers under accelerated stress conditions, such as 75% relative humidity (RH) and 50°C [11]. Samples are prepared in both open and closed vials to differentiate between the effects of temperature and moisture. After a defined period (e.g., 48 days), the samples are analyzed using techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) to identify any solid-form changes [11].

Real-Time Polymorphic Assessment at Tabletting Pressures

- Objective: To assess the risk of pressure-induced polymorphic transition during compression using minimal API.

- Protocol: A Diamond Anvil Cell (DAC) can be used to apply high pressures to microgram quantities of API without a pressure-transmitting medium. The sample is loaded directly into the DAC sample chamber, and Raman spectroscopy is used to monitor form changes in real-time as pressure increases. This method has been successfully employed to detect a transition in Hydrochlorothiazide starting at 300 MPa, commensurate with changes observed in larger-scale texture analyzer experiments [10].

Spray Drying for Novel Polymorph Isolation

- Objective: To discover new polymorphic forms through a controlled, rapid drying process.

- Protocol: As demonstrated with chlorothiazide (CTZ), a solution of the API (e.g., 3.85 mg/ml in acetone) is processed using a spray dryer with a two-fluid nozzle [12]. Key parameters like the atomising gas flowrate are varied. The resulting solids are collected and characterized by PXRD, Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA), and DSC. This technique led to the isolation of a novel form, CTZ Form IV, which was pure at lower atomising gas flowrates and converted to the stable Form I under accelerated stability conditions (40°C/75% RH) [12].

Computational and Informatics Approaches for De-risking

Computational methods have become indispensable for complementing experimental polymorph screening, offering a proactive strategy to identify potential stability risks.

- Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP): Advanced CSP methods combine systematic crystal packing search algorithms with machine learning force fields and periodic Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to predict all low-energy polymorphs of a given API [13]. One such method was validated on a large set of 66 molecules, successfully reproducing 137 known polymorphs and, crucially, suggesting new low-energy polymorphs not yet discovered experimentally [13]. This capability allows for the "derisking" of a development candidate by flagging potential for more stable forms to emerge later.

- Solid Form Informatics (Health Check): An informatics-based risk assessment compares the crystal structure of a development form to knowledge bases like the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [14]. This "Health Check" analyzes intramolecular geometry and hydrogen-bonding networks to identify high-energy conformations or suboptimal interactions that might indicate latent instability or the possibility of a better-packed, more stable crystal form [14]. For example, this approach was applied to four polymorphs of PF-06282999 to understand their relative stability and packing efficiency [14].

The synergy between these computational approaches and experimental data creates a powerful framework for solid-form selection, as visualized in the following workflow.

Integrated Workflow for Solid Form Derisking

The Role of Phase Diagrams in Validating Thermodynamic Stability

Within the context of validating thermodynamic stability, phase diagram analysis provides a fundamental framework. The CALculation of PHAse Diagrams (CALPHAD) methodology is a powerful computational tool used to model the thermodynamic relationships and stability ranges of different phases in a system [4] [15]. While traditionally applied in metallurgy and materials science, the underlying principles are directly relevant to pharmaceutical systems involving APIs, co-formers, and solvents.

- Experimental Basis: The CALPHAD method relies on robust experimental data. For instance, phase equilibria in the Cr-Ta binary system were determined at temperatures up to 2100°C using techniques like Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) and composition measurement via Field-Emission Electron Probe Microanalyzer (FE-EPMA) with Wavelength-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (WDS) [4]. Similar methods, adapted for lower temperature ranges, can be applied to study API-co-former systems.

- Thermodynamic Modeling: The experimental data are used to optimize a set of self-consistent thermodynamic parameters for the system. The calculated phase diagram, built from these parameters, should be in good agreement with the experimentally determined phase equilibrium data [4]. This model can then predict the system's behavior under conditions not explicitly tested, identifying regions of stability for specific solid forms.

This approach ensures that the relative stability of different solid forms is not just empirically observed but is understood within a rigorous thermodynamic framework, providing greater confidence in the selection of the most appropriate form for development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for conducting polymorph screening and stability analysis, as referenced in the studies discussed.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Polymorph Studies

| Item / Technique | Function in Polymorphism Research | Specific Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Characterizes thermal events (melting, crystallization, solid-solid transitions); distinguishes polymorphic forms by their unique thermal fingerprints. | Used to identify pure forms and mixtures in buspirone HCl, proving most effective for distinction [11]. |

| Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Provides a fingerprint of the crystal structure; identifies different polymorphs based on their unique diffraction patterns. | Used to confirm the novel structure of CTZ Form IV and monitor its transformation [12]. |

| Diamond Anvil Cell (DAC) | Applies high pressure to microgram API quantities to simulate tableting forces and monitor pressure-induced form changes. | Detected Hydrochlorothiazide transition at 300 MPa, a material-sparing alternative to compaction simulators [10]. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Probes molecular vibrations and crystal lattice modes; used for real-time, in-situ monitoring of polymorphic transitions. | Coupled with DAC to monitor Hydrochlorothiazide transformation in real-time [10]. |

| Spray Dryer | Provides a controlled, rapid drying environment to isolate metastable polymorphs or amorphous forms not accessible by slow crystallization. | Used to isolate the novel metastable form of chlorothiazide (Form IV) from an acetone solution [12]. |

| Climate Chamber | Subjects solid forms to controlled stress conditions (temperature and humidity) to assess their physical stability and propensity for transformation. | Used for stability testing of buspirone HCl samples at 50°C/75% RH [11]. |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Identifies functional groups and hydrogen bonding patterns, which can differ between polymorphs. | Employed for structural characterization of buspirone HCl samples [11]. |

The strategic navigation of API polymorphs and their relative stability is a cornerstone of modern drug development. As evidenced by historical challenges and ongoing research, a comprehensive understanding of the solid-form landscape is non-negotiable for ensuring the consistent quality, safety, and efficacy of a drug product. A holistic strategy that integrates robust experimental screening, advanced computational predictions, and a fundamental thermodynamic understanding through techniques like phase diagram analysis is essential. By leveraging the detailed experimental protocols and comparative data outlined in this guide, scientists and drug development professionals can make informed decisions, mitigate the risks of late-appearing polymorphs, and select the most robust solid form for successful pharmaceutical development.

The Critical Link Between Thermodynamic Stability, Solubility, and Bioavailability

Drug bioavailability is a crucial aspect of pharmacology, affecting the therapeutic effectiveness of pharmaceutical treatments. Bioavailability determines the proportion and rate at which an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is absorbed from a dosage form and becomes available at the site of action. A drug can only produce its expected therapeutic effect when adequate concentration levels are achieved at the desired target within the patient's body [16]. For orally administered drugs, this journey is particularly challenging as the compound must first dissolve in gastrointestinal fluids before it can permeate through the intestinal barrier and reach systemic circulation. The aqueous solubility of a drug substance therefore serves as a fundamental prerequisite for its absorption and subsequent bioavailability [17].

The relationship between thermodynamic stability, solubility, and bioavailability represents one of the most significant challenges in modern pharmaceutical development. An estimated 70-90% of drug candidates in the development stage, along with approximately 40% of commercialized products, are classified as poorly water-soluble, leading to suboptimal bioavailability, diminished therapeutic effects, and frequently requiring dosage escalation [17]. This challenge is systematically categorized through the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS), which classifies drug substances into four categories based on their solubility and intestinal permeability characteristics. BCS Class II drugs (low solubility, high permeability) and BCS Class IV drugs (low solubility, low permeability) present the most formidable development hurdles, as their therapeutic potential is limited by dissolution rate and absorption challenges rather than intrinsic pharmacological activity [17].

Understanding and controlling the thermodynamic aspects of drug substances has become a priority in pharmaceutical development. The thermodynamic stability of a specific solid form directly governs its solubility behavior through the balance of energetic forces between the crystal lattice and the solvation environment. This article explores the critical interrelationship between thermodynamic stability, solubility, and bioavailability, examining current formulation strategies, advanced characterization methodologies, and experimental approaches for optimizing drug product performance.

Thermodynamic Principles Governing Drug Solubility and Stability

Fundamental Thermodynamic Concepts in Pharmaceutical Systems

The thermodynamic behavior of pharmaceutical systems is governed by the fundamental principles of energy transfer and transformation during molecular interactions. The crucial parameter describing molecular interactions is the Gibbs free energy (ΔG), where both magnitude and sign determine the spontaneity of biomolecular events. A binding event described by a negative free energy (exergonic process) occurs spontaneously to an extent governed by the magnitude of ΔG, while positive ΔG values (endergonic process) indicate that binding requires external energy input [18]. The equilibrium binding constant, or binding affinity (K~a~), provides access to ΔG through the relationship ΔG° = -RT ln K~a~, where ΔG° refers to the standard Gibbs free energy change [18].

The free energy provides only part of the thermodynamic picture, as it is composed of enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) components according to the equation ΔG = ΔH - TΔS. Enthalpy reflects heat differences between reactants and products of a binding reaction resulting from net bond formation or breakage. Entropy reveals the distribution of energy among molecular energy levels, with positive values associated with increased disorder [18]. This separation is critically important in pharmaceutical development because similar ΔG values can mask radically different ΔH and ΔS contributions, representing entirely different binding modes and stability mechanisms with significant implications for drug formulation [18].

The thermodynamic solubility of a compound is defined as the maximum quantity of that substance that can be completely dissolved in a given amount of solvent at specified temperature and pressure, with the solid phase existing in equilibrium with the solution phase. This represents a true equilibrium measurement distinct from kinetic solubility, which reflects metastable conditions where solute concentration temporarily exceeds the equilibrium solubility [19]. The distinction is crucial in pharmaceutical development, as kinetic solubility measurements may provide misleading data that does not reflect the long-term stability and performance of the formulated product.

Polymorphism and Solid Form Stability

The solid-state form of an active pharmaceutical ingredient profoundly impacts its thermodynamic stability and solubility profile. Polymorphic systems are classified into two primary types based on their phase transformation behavior [19]:

Enantiotropic systems feature reversible transformations where one polymorph represents the most stable phase within a specific temperature and pressure range, while another form is more stable under different conditions. The temperature at which the solubility curves of enantiotropic polymorphs intersect is termed the transition point.

Monotropic systems display irreversible transformations where only one polymorph remains stable at all temperatures below the melting point, with all other forms being metastable throughout the temperature range.

The intrinsic lattice energies of different polymorphs manifest in different enthalpies of fusion and melting points, yielding different slopes and intercepts for ideal solubility lines. The practical implication is that at any given temperature, the polymorph with the lower solubility represents the more thermodynamically stable form [19]. This relationship directly impacts bioavailability, as metastable forms with higher apparent solubility may initially enhance dissolution rates but eventually convert to more stable, less soluble forms, leading to inconsistent exposure.

Amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) represent an important formulation approach that leverages metastable states to enhance solubility. Amorphous compounds lack long-range molecular order and exhibit significantly higher thermodynamic properties, including volume, enthalpy, and entropy, compared to their crystalline counterparts. This enhanced thermodynamic state is key to their higher solubility, but comes with inherent physical instability risks, including tendency for devitrification (conversion to crystalline form) [20]. The dissolution of amorphous compounds often follows the "spring and parachute effect," where an initial spike in drug concentration (spring) is followed by a decline (parachute) due to crystallization [20].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters and Their Pharmaceutical Significance

| Parameter | Symbol | Pharmaceutical Significance | Impact on Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy | ΔG | Determines spontaneity of dissolution process | Dictates inherent solubility limitations |

| Enthalpy | ΔH | Reflects energy changes from bond formation/breakage | Influences temperature-dependent solubility behavior |

| Entropy | ΔS | Measures system disorder changes | Affects solvation and desolvation processes |

| Heat Capacity | ΔCp | Indicates temperature dependence of enthalpy | Signals hydrophobic interactions and conformational changes |

| Configurational Entropy | S~conf~ | Measures molecular arrangement disorder | Correlates with physical stability of amorphous systems |

Experimental Approaches for Phase Behavior Analysis

Phase Diagram Determination Methods

Phase diagram determination represents a fundamental methodology for understanding the stability domains of different solid forms and their interconversion boundaries. Traditional phase diagram construction involves preparing alloys or mixtures of required constituents, heat treating at various temperatures to establish equilibrium states, and subsequently identifying phases to determine transition boundaries such as liquidus temperatures, solidus temperatures, and solubility lines [21]. Techniques including thermal analysis, metallography, X-ray diffraction, dilatometry, and electrical conductivity measurements are employed based on the principle that phase transitions induce changes in physical and chemical properties [21].

The process of phase diagram determination has been described as "somewhat a never-ending task," particularly for complex systems, as subtle crystal structure changes may be missed without advanced facilities, and specimen purity variations can introduce discrepancies requiring further investigation [21]. This challenge is exemplified by the Ti-Al binary system, whose phase diagram determination began in 1923 and has undergone multiple assessments based on hundreds of references, representing a multimillion-dollar research investment [21].

Recent technological advances have introduced more efficient approaches to phase behavior analysis. The PhaseXplorer platform combines microfluidics, microscopy, and machine learning to autonomously design, generate, and analyze samples in a closed-loop active learning workflow. This system can create high-dimensional phase diagrams up to 100 times faster than traditional methods while consuming 10,000 times less material [22]. The platform operates by mixing aqueous solutions into fluorinated oil to form picoliter-scale droplets, with composition controlled by adjusting relative flow rates. After incubation, phase separation in droplets is detected using fluorescent dyes and a pretrained convolutional neural network that can identify phase separation in less than 1 millisecond per droplet [22].

Thermodynamic Modeling and Computational Approaches

The ever-increasing interplay of modeling and experiment has transformed phase diagram determination in pharmaceutical development. Thermodynamic modeling approaches, particularly the CALPHAD (Calculation of Phase Diagrams) method, enable efficient determination by integrating approximate thermodynamic descriptions based on constituent systems with strategically selected experimental data points to maximize information value [21]. This iterative process begins with preliminary assessment assuming no ternary or higher-order compounds and negligible solubilities of additional elements in binary intermediates, then incorporates key experimental information to refine thermodynamic parameters [21].

Gaussian process regression (GPR) has emerged as a valuable tool for constructing probability distributions of phase behavior across parameter space. GPR yields uncertainty estimates along with predictions, providing essential guidance for acquisition functions that balance exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of known phase boundaries [22]. In active learning cycles, GPR models use collected data to predict phase behavior probability across the entire experimental space, then employ acquisition functions to select the most informative subsequent samples [22].

For solubility modeling in supercritical fluid systems, both density-based models (Chrastil, Bartle, K-J, MST) and thermodynamically rigorous equations of state (PC-SAFT, Peng-Robinson, Soave-Redlich-Kwong) have demonstrated utility. In the case of sumatriptan solubility in supercritical CO~2~, the K-J density-based model yielded the best correlation (AARD = 8.21%, R~adj~ = 0.991), while PC-SAFT provided the most accurate thermodynamic modeling (AARD = 11.75%, R~adj~ = 0.988) [23]. These models also enable estimation of thermal parameters including total enthalpy, vaporization enthalpy, and solvation enthalpy, providing comprehensive thermodynamic characterization [23].

Diagram 1: Active Learning Workflow for Phase Diagram Determination. This process integrates microfluidics, automated imaging, and machine learning to efficiently map phase boundaries through iterative sample selection.

Formulation Strategies to Modulate Thermodynamic Properties

Amorphous Solid Dispersions and Stabilization Approaches

Amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) have emerged as transformative formulation strategies for addressing the persistent challenges posed by poorly water-soluble drugs. By dispersing amorphous drugs within polymer matrices, ASDs stabilize the inherently unstable amorphous state, preventing devitrification while maintaining solubility advantages [20]. The historical development of ASDs dates to 20th-century eutectic mixtures, with significant commercial advancement in the 1990s with Sporanox (itraconazole), followed by FDA approvals of Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) and Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir). From 2012 to 2023, the FDA approved 48 ASD-based formulations, signaling a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical development [20].

The stability of ASD formulations depends on multiple factors, including the glass transition temperature (T~g~), molecular mobility, drug-polymer miscibility, manufacturing methods, and environmental conditions such as moisture. The crystallization inhibition capacity of ASDs is often evaluated through the reduced glass transition temperature (T~rg~ = T~g~/T~m~), which determines the glass-forming ability of the system. Polymers function as anti-plasticizers by increasing system viscosity, reducing molecular mobility, and raising T~g~, thereby enhancing ASD stability [20]. Drug-polymer interactions, including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic or hydrophobic interactions, further contribute to stability, though these interactions are highly dependent on drug-polymer miscibility and their relative ratios [20].

Table 2: Formulation Technologies for Solubility Enhancement

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Thermodynamic Principle | Representative Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorphous Solid Dispersions | Molecular dispersion in polymer matrix | Metastable amorphous state with higher free energy | Sporanox, Gleevec, Kaletra |

| Lipid-Based SEDDS | Self-emulsification increases surface area | Interfacial thermodynamics at oil-water interface | Neoral, Norvir |

| Nanocrystals | Increased surface area to volume ratio | Ostwald-Freundlich equation for solubility | Rapamune, Tricor |

| Cyclodextrin Complexation | Host-guest inclusion complexes | Selective molecular encapsulation | Sporanox IV, Vfend |

| Salt Formation | Alters lattice energy and ionization | Proton transfer equilibrium | Most APIs (>50%) |

Lipid-Based Self-Emulsifying Systems

Lipid-based self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) represent another prominent approach for enhancing the oral delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs. These systems improve drug solubilization, absorption, and bioavailability through self-emulsification processes that generate fine colloidal dispersions upon contact with gastrointestinal fluids [24]. The performance of SEDDS is governed by the physicochemical profile of excipients—including lipids, surfactants, and cosurfactants—which directly influence critical formulation behaviors such as drug loading, self-emulsification capacity, droplet size, and colloidal stability [24].

Parameters including hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB), polarity, viscosity, and interfacial tension dictate intermolecular interactions at the oil-water interface, impacting both thermodynamic stability and emulsification kinetics. Advances such as supersaturable SEDDS and mucoadhesive systems, combined with solidification technologies like spray drying, adsorption, and 3D printing, have expanded the applicability and stability of these formulations [24]. Understanding these physicochemical interactions and their synergistic effects is indispensable for rational system design and successful clinical translation.

Characterization and Analytical Methods

Solid-State Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of pharmaceutical solids employs multiple analytical techniques to assess solid-state properties, stability, and potential phase transformations. Advanced analytical methods provide critical insights into the physical and chemical stability of complex systems like amorphous solid dispersions [20]. There is no single technique that provides comprehensive information on both solid-state and solution-state properties, necessitating a complementary analytical approach [20].

Key characterization techniques include:

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Measures thermal transitions including glass transition temperature (T~g~) and melting point (T~m~), helping evaluate stability and recrystallization tendencies [20].

Isothermal Microcalorimetry (IMC): Provides sensitive measurement of heat flow associated with physical and chemical processes under constant temperature conditions [20].

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Identifies drug-polymer interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding, through characteristic vibrational frequency shifts [20].

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD): Distinguishes between crystalline and amorphous states and detects recrystallization in stored samples [20].

Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (ssNMR): Provides molecular-level information about drug-polymer miscibility and molecular mobility [20].

These techniques, combined with innovations in formulation approaches, enhance scalability and address reproducibility challenges in pharmaceutical development [20].

Thermodynamic Parameter Assessment

The assessment of thermodynamic parameters provides fundamental insights into the stability behavior of pharmaceutical systems. Both kinetic and thermodynamic factors can be correlated with physical stability to develop predictive models. Key parameters include [25]:

Relaxation time (τ): Represents the timescale of molecular motions and reorganization processes in amorphous systems.

Fragility index (D): Describes the temperature dependence of viscosity or relaxation time as the glass transition is approached.

Configurational thermodynamic properties: Including configurational enthalpy (H~conf~), entropy (S~conf~), and Gibbs free energy (G~conf~), which represent the differences between amorphous and crystalline states.

Research has demonstrated that above T~g~, reasonable correlations exist between thermodynamic parameters and stability, with configurational entropy exhibiting the strongest correlation (r² = 0.685) [25]. However, below T~g~, no clear relationship between these factors and physical stability has been established, indicating that stability predictions based solely on relaxation time may be inadequate [25].

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Thermodynamic Stability Assessment. This comprehensive characterization approach connects solid-state analysis with stability parameters and ultimate performance evaluation.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Key Experimental Methodologies

Solubility Measurement Protocol (Gravimetric Method): The equilibrium solubility of drug substances is routinely determined as part of preformulation programs, with the analytical method being the most common approach [19] [23]. The detailed procedure involves:

System Preparation: Use a specialized high-pressure system with a vessel capable of withstanding pressures up to 40 MPa and temperatures up to 423 K. Verify all seals, valves, and fittings are properly installed and leak-free [23].

Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh the drug substance (approximately 2000 mg) using an analytical balance with 0.01 mg sensitivity. For compact systems, compress powder into tablets with uniform diameter (~5 mm) to ensure consistent volume and structural integrity [23].

Equilibration Process: Gradually introduce solvent (e.g., CO~2~ for supercritical systems) by increasing pressure in 0.1 MPa increments to avoid sudden surges. Maintain stable temperature within ±0.1 K with continuous stirring at 250 rpm to promote uniform mixing [23].

Equilibrium Confirmation: Allow the system to equilibrate with continuous stirring for sufficient time (typically 300 minutes) to reach solubility equilibrium. Periodically monitor pressure and temperature to ensure stability within specified ranges [23].

Sample Collection and Analysis: After equilibration, rapidly depressurize the vessel to ambient conditions to halt dissolution. Carefully remove and weigh undissolved drug using an analytical balance. Perform replicate experiments (minimum three runs) to ensure reproducibility [23].

Calculation: Determine dissolved drug mass using: m~dissolved~ = m~initial~ - m~undissolved~. Calculate mole fraction incorporating molecular weights of drug and solvent [23].

Phase Diagram Mapping Protocol: For traditional phase diagram determination:

Alloy Preparation: Prepare alloys of required constituents through weighing, mixing, and appropriate homogenization techniques [21].

Heat Treatment: Subject alloys to controlled heat treatment at high temperatures to reach equilibrium states. The specific temperature profile depends on the system under investigation [21].

Phase Identification: Employ multiple characterization techniques including thermal analysis, metallography, and X-ray diffraction to identify phases present under different conditions [21].

Boundary Determination: Determine phase transition boundaries (liquidus temperatures, solidus temperatures, solubility lines) based on detected changes in physical and chemical properties at different compositions and temperatures [21].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Stability Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Supercritical CO~2~ | Environmentally friendly solvent for particle engineering | Sumatriptan solubility measurement [23] |

| Polymer Carriers | Stabilize amorphous dispersions, inhibit crystallization | HPMC, PVP, copovidone in ASDs [20] |

| Lipid Excipients | Enhance solubilization in SEDDS | Medium-chain triglycerides, mixed glycerides [24] |

| Surfactants | Reduce interfacial tension, promote self-emulsification | Polysorbates, polyoxylglycerides in SEDDS [24] |

| Cryoprotectants | Stabilize formulations during freezing processes | Trehalose, sucrose in lyophilized products |

| Thermodynamic Model Compounds | Validate computational predictions | Poly rA for phase separation studies [22] |

The critical relationship between thermodynamic stability, solubility, and bioavailability represents both a fundamental challenge and opportunity in pharmaceutical development. The thermodynamic profile of an active pharmaceutical ingredient dictates its intrinsic solubility limitations, while strategic formulation approaches can modulate these properties to enhance bioavailability without compromising long-term stability. The continuing evolution of characterization technologies, particularly those enabling high-throughput phase diagram mapping and real-time stability assessment, promises to accelerate development timelines while improving product performance.

Future advancements will likely focus on integrated computational and experimental approaches that leverage machine learning algorithms, molecular modeling, and predictive thermodynamics to guide formulation design. The ongoing refinement of amorphous solid dispersions, lipid-based systems, and other solubility-enabling technologies will continue to expand the formulation toolkit for challenging drug candidates. However, the field must also address scalability and reproducibility challenges associated with these advanced approaches to ensure consistent product quality and performance.

As pharmaceutical research increasingly focuses on complex molecules with inherent solubility challenges, the fundamental principles of thermodynamic stability will remain essential for rational formulation design. By continuing to advance our understanding of the energetic basis of molecular interactions and their impact on drug absorption, the pharmaceutical field can overcome bioavailability barriers and fully realize the therapeutic potential of new molecular entities.

Phase diagrams are fundamental tools in materials science, providing a visual representation of the equilibrium states of a material system under varying conditions of temperature, pressure, and composition. For researchers and scientists, the ability to accurately interpret these diagrams is crucial for predicting material behavior, designing alloys, and validating thermodynamic stability. This guide focuses on three critical transformation types—eutectics, peritectics, and solid solutions—that govern microstructure development in metallic and ceramic systems. Understanding these transformations enables professionals to tailor material properties for specific applications, from high-temperature alloys to pharmaceutical compounds.

The analysis of phase transformations extends beyond theoretical prediction to experimental validation through advanced characterization techniques. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of coupling experimental data with computational thermodynamics, such as the CALPHAD technique, to develop self-consistent phase diagrams [26] [4]. This integrated approach ensures greater accuracy in predicting phase stability regions, transformation temperatures, and microstructural evolution, providing a reliable foundation for materials design in research and industrial applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Key Phase Transformations

Eutectic Transformations

Eutectic transformations represent a fundamental type of invariant reaction in which a single liquid phase simultaneously transforms into two different solid phases upon cooling. This transformation occurs at a specific composition and temperature known as the eutectic point, which is the lowest melting point in the system. The general reaction can be represented as: Liquid → α + β, where α and β are distinct solid phases. Eutectic systems are characterized by their lamellar or rod-like microstructures, which form through a cooperative growth mechanism of the two solid phases from the melt.

The distinguishing feature of eutectic growth is the simultaneous nucleation and growth of both solid phases with distinct crystalline structures and compositions. Recent research on ternary Fe-Ni-Ti alloys has provided direct evidence of this mechanism, showing that "the eutectic in the mushy zone had multiple orientation relationships" [27], indicating independent nucleation events. This differs significantly from peri-eutectic growth, where phases maintain crystallographic relationships with primary solids. Eutectic alloys are particularly valuable in materials design because they often exhibit fine, uniform microstructures and excellent casting properties, making them ideal for applications requiring consistent mechanical behavior and low melting points.

Peritectic Transformations

Peritectic transformations represent another critical invariant reaction in phase diagrams, occurring when a liquid phase reacts with a primary solid phase to form a new secondary solid phase upon cooling. The general peritectic reaction can be represented as: Liquid + α → β, where α is the primary solid phase and β is the new solid phase formed through the reaction. Unlike eutectic transformations that involve a liquid decomposing into two solids, peritectic systems feature a reaction between existing solid and liquid phases to create a different solid phase.

These transformations are particularly important in industrial processes such as steel production and alloy solidification, where they significantly influence final microstructure and material properties. The peri-eutectic transition observed in ternary Fe-Ni-Ti alloys exemplifies the complexity of these reactions, with researchers finding that "the primary phase and the peri‑eutectic in the solid region had a common orientation relationship" [27], indicating that the peri-eutectic phase nucleates from the primary phase and grows cooperatively. This crystallographic relationship distinguishes peritectic-type transformations from true eutectic growth and affects the resulting mechanical properties. Peritectic solidification often presents challenges in manufacturing due to the tendency for the new phase to form a shell around the primary phase, potentially limiting complete transformation and creating compositional inhomogeneities.

Solid Solution Formation

Solid solutions represent perhaps the most common phase relationship in materials systems, occurring when two or more elements share the same crystal lattice while maintaining a single phase across a range of compositions. In a solid solution, atoms of the solute element incorporate into the crystal structure of the solvent element, either through substitutional (replacing solvent atoms) or interstitial (occupying spaces between solvent atoms) mechanisms. The Co-Cr and Cr-Ta binary systems provide excellent examples of extensive solid solution formation, with continuous solid solubility influencing high-temperature properties and corrosion resistance.

The formation of solid solutions is governed by factors including atomic size differences, electronegativity, and crystal structure compatibility between elements. Complete solid solubility, as observed in the Cr-Ta system, requires that the components have the same crystal structure and similar atomic radii [4]. Partial solid solutions, more common in industrial alloys, exist within specific compositional ranges bounded by phase boundaries known as solvus lines. Solid solutions strengthen materials through mechanisms such as lattice strain and modulus mismatch, making them fundamental to alloy design for structural applications. The thermodynamic stability of solid solutions is validated through precise measurement of phase boundaries using techniques like electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA), which provide experimental data for CALPHAD assessments [26] [4].

Experimental Data Comparison of Transformation Types

The table below summarizes key experimental data and characteristics for eutectic, peritectic, and solid solution transformations, providing a quantitative comparison for researchers.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key phase transformations in metallic systems

| Transformation Type | General Reaction | Key Characteristics | Example Systems | Transformation Temperature/Energy | Experimental Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eutectic | Liquid → α + β | Simultaneous formation of two solids; Multiple orientation relationships | Fe-Ni-Ti, Sn-Pb, Al-Si | Fe-Ni-Ti: Peri-eutectic transition at specific composition [27] | Directional solidification, Microstructural analysis (EPMA) [27] |

| Peritectic | Liquid + α → β | Reaction between liquid and primary solid; Common orientation with primary phase | Fe-Ni-Ti, Fe-C, Cu-Zn | Fe-Ni-Ti: Peri-eutectic growth with primary phase orientation [27] | Directional solidification, Crystallographic analysis [27] |

| Solid Solution | α → α (variable composition) | Continuous solubility; Single-phase region; Uniform crystal structure | Co-Cr, Cr-Ta | Co-Cr: γ(Co) + α(Cr) phase boundaries at high temperatures [26]; Cr-Ta: Liquidus up to 2100°C [4] | EPMA/WDS, DTA, Diffusion couples [26] [4] |

Table 2: Experimental methodologies for phase boundary determination

| Experimental Technique | Application in Phase Diagram Determination | Key Measurements | Limitations/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA) with Wavelength-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (WDS) | Determining equilibrium compositions in two-phase alloys; Measuring composition profiles in diffusion couples | Phase boundaries; Compositional ranges of intermediate phases | Requires careful sample preparation and standardized heat treatment conditions [26] [4] |

| Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) | Measuring transformation temperatures (liquidus, solidus, invariant reactions) | Transformation temperatures; Reaction enthalpies | Limited by sample container interactions at very high temperatures; Requires calibration with standard materials [4] |

| Directional Solidification | Studying solidification morphology and crystallographic relationships | Orientation relationships between phases; Growth mechanisms | Creates non-equilibrium conditions; Results depend on solidification velocity [27] |

| Diffusion Couples | Determining phase equilibria and interdiffusion coefficients | Phase sequence; Composition ranges; Interdiffusion coefficients | Requires long annealing times to establish local equilibrium; Limited by formation of interfacial reaction layers [4] |

Case Studies in Phase Diagram Analysis

Peri-eutectic vs. Eutectic Transformation in Fe-Ni-Ti Alloys

Recent investigation of the ternary Fe-Ni-Ti system has provided remarkable insights into the distinction between peri-eutectic and eutectic growth mechanisms. In the Fe66.5Ni17.6Ti15.9 alloy, researchers observed a peri-eutectic transition following the reaction L+δ-Fe→γ-Fe(Ni)+Fe2Ti during directional solidification [27]. Microstructural and crystallographic analysis revealed that "the primary phase and the peri‑eutectic in the solid region had a common orientation relationship, while the eutectic in the mushy zone had multiple orientation relationships" [27]. This fundamental difference provides direct evidence for distinct growth mechanisms: peri-eutectic phases nucleate from the primary phase and grow cooperatively under near-equilibrium conditions, while eutectic phases form through independent nucleation events, particularly under non-equilibrium conditions such as quenching.

The practical implications of these different transformation mechanisms are significant for materials design. The peri-eutectic structure in Fe-Ni-Ti alloys, characterized by a quaternary junction at the phase boundaries, results in a more coherent interface structure that influences mechanical properties [27]. Subsequent solid-state transformations, where "the primary δ-Fe phase transformed to the lamellar α-Fe phase with different orientations after peri‑eutectic transition" [27], further complicate the final microstructure. Understanding these subtle differences enables materials scientists to better control solidification processes to achieve desired microstructural features, particularly in complex ternary and higher-order systems where multiple transformation pathways may compete during solidification.

High-Temperature Phase Stability in Co-Cr and Cr-Ta Systems

The Co-Cr and Cr-Ta binary systems exemplify the importance of accurate phase diagram determination for high-temperature applications. Recent experimental reinvestigation of the Cr-Ta system revealed significant deviations from previously accepted phase boundaries, particularly for the C14 and C15 Cr2Ta intermetallic phases [4]. Using field-emission EPMA combined with WDS, researchers discovered that "the single-phase regions of the C14 and C15 Cr2Ta phases extended from the stoichiometry (x(Ta) = 0.333) to both the Cr-rich and Ta-rich sides" [4], indicating broader homogeneity ranges than previously reported. Furthermore, the phase boundaries between these intermetallic phases existed at higher temperatures than indicated in earlier studies, highlighting how improved experimental techniques can revise fundamental materials data.

Similarly, in the Co-Cr system, experimental determination of phase equilibria across the complete composition range yielded updated thermodynamic parameters [26]. Measurements revealed that "liquidus and solidus temperatures, measured up to 1800°C using a differential thermal analyzer and differential scanning calorimeter, were slightly higher than those reported in the literature" [26]. These systematic differences underscore the necessity of contemporary experimental methods with better temperature measurement accuracy and compositional analysis capabilities. In both systems, researchers employed the CALPHAD technique to develop self-consistent thermodynamic descriptions based on the new experimental data, demonstrating the iterative process of phase diagram assessment and refinement that remains essential for materials development, particularly for high-temperature structural applications.

Experimental Protocols for Phase Diagram Determination

Alloy Preparation and Heat Treatment

The foundation of accurate phase diagram determination lies in careful alloy preparation and controlled heat treatment. For the Cr-Ta system, alloys are typically prepared from high-purity starting materials (generally >99.9%) using arc-melting or induction melting under an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation [4]. To ensure homogeneity, ingots are often turned and remelted multiple times. For equilibrium studies, samples are subsequently encapsulated in quartz tubes under vacuum or inert gas and subjected to prolonged annealing at target temperatures. The specific heat treatment conditions are critical, as they must be sufficient to establish equilibrium without introducing secondary effects such as excessive grain growth or contamination. In the Cr-Ta system, researchers paid particular attention to heat treatment conditions, annealing samples at temperatures up to 2100°C to accurately determine high-temperature phase equilibria [4].

Following heat treatment, rapid quenching is often employed to preserve high-temperature phases for room-temperature analysis. The cooling method must be sufficiently rapid to prevent solid-state transformations during cooling while avoiding thermal shock that could crack the samples. For some systems, particularly those with sluggish transformations, alternative approaches such as diffusion couples may be preferable. In the Cr-Ta system, researchers utilized diffusion couples consisting of pure Cr and Ta blocks annealed at target temperatures to establish local equilibrium at the interface [4]. This approach efficiently determines phase sequences and approximate composition ranges across the entire system, complementing data from individual alloy samples.

Microstructural and Compositional Analysis

Microstructural characterization forms the core of experimental phase diagram determination, with electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) coupled with wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (WDS) serving as the primary technique for quantitative compositional measurement. Modern field-emission EPMA instruments provide high spatial resolution and analytical sensitivity, enabling accurate measurement of phase compositions in multiphase microstructures [26] [4]. For reliable results, samples must be meticulously prepared using standard metallographic techniques followed by appropriate etching to reveal phase boundaries. Measurement standards matched to the system of interest are essential for quantitative analysis, with multiple measurements taken for each phase to account for microsegregation and establish statistical significance.

Complementary microstructural analysis typically includes X-ray diffraction for phase identification and scanning electron microscopy for examination of morphological features. In directional solidification studies, such as the Fe-Ni-Ti system investigation, electron backscatter diffraction may be employed to determine crystallographic orientation relationships between phases [27]. For temperature measurement, differential thermal analysis provides data on transformation temperatures, though container interactions at very high temperatures can introduce errors that require careful calibration [4]. The integration of data from these multiple experimental techniques provides a comprehensive basis for phase boundary determination and validation of thermodynamic stability in complex systems.

Computational Thermodynamic Assessment

The CALPHAD method represents the state of the art in computational thermodynamic assessment of phase diagrams. This approach involves developing mathematical models for the Gibbs energy of each phase in a system and optimizing model parameters to reproduce experimental data [26] [4]. The thermodynamic models account for contributions from pure elements, mechanical mixing, and excess Gibbs energy due to interactions between components. For solid solutions, models such as the substitutional solution model are typically employed, while intermetallic phases may be modeled using compound energy formalism.

The optimization process seeks to find the set of parameters that best reproduces all available experimental data, including phase equilibria, thermodynamic properties, and crystal structure information. As demonstrated in both the Co-Cr and Cr-Ta systems, this results in "a set of self-consistent thermodynamic parameters" that enable calculation of the complete phase diagram [26] [4]. The key advantage of the CALPHAD approach is its predictive capability for multicomponent systems based on binary and ternary data, making it invaluable for materials design. Furthermore, the calculated phase diagrams can be used to simulate non-equilibrium solidification processes using Scheil-Gulliver models, bridging the gap between equilibrium thermodynamics and practical processing conditions.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The table below details key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for experimental phase diagram determination, providing researchers with a comprehensive overview of field requirements.

Table 3: Essential research materials and equipment for phase diagram analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Materials | Pure metals (Cr, Ta, Co, etc.) | Starting materials for alloy preparation | Purity >99.9% (often 99.99%+) to minimize impurity effects [26] [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Arc melter/Induction furnace | Alloy synthesis | Water-cooled copper hearth, Inert atmosphere (Ar) [4] |

| Heat Treatment | Vacuum encapsulation system | Sample annealing at high temperatures | Quartz tubes, High vacuum system (<10⁻³ Pa) [4] |

| Microstructural Analysis | Field-Emission Electron Probe Microanalyzer (FE-EPMA) | Quantitative compositional measurement | WDS detection, High spatial resolution (<1 μm) [4] |

| Thermal Analysis | Differential Thermal Analyzer (DTA) / Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Transformation temperature measurement | High-temperature capability (up to 1800°C+) [26] |

| Computational Tools | CALPHAD software | Thermodynamic modeling and phase diagram calculation | PARROT module in Thermo-Calc or similar optimization tools [26] [4] |

The decoding of phase diagrams through accurate interpretation of eutectics, peritectics, and solid solutions remains fundamental to materials research and development. As demonstrated by recent studies of Fe-Ni-Ti, Co-Cr, and Cr-Ta systems, advances in experimental techniques and computational methods continue to refine our understanding of phase transformations and thermodynamic stability [26] [4] [27]. The integration of sophisticated characterization tools like FE-EPMA with directional solidification studies and CALPHAD modeling provides researchers with a powerful methodology for validating and predicting phase behavior in complex systems.

For research professionals, mastering these interpretation skills enables more effective materials design across diverse applications from high-temperature alloys to functional materials. The comparative analysis presented in this guide highlights both the distinctive characteristics of different transformation types and the experimental approaches required for their accurate determination. As phase diagram research continues to evolve, particularly with the integration of machine learning and high-throughput computational methods, the fundamental principles of eutectic, peritectic, and solid solution behavior will continue to provide the foundation for understanding and predicting materials stability in both conventional and emerging material systems.

In the pursuit of designing high-affinity drug candidates, lead optimization traditionally focuses on improving the binding affinity, often quantified by the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG). However, this approach can be thwarted by a pervasive thermodynamic phenomenon known as entropy-enthalpy compensation (EEC). In this process, favorable changes in binding enthalpy (ΔH) are counterbalanced by unfavorable changes in binding entropy (-TΔS), or vice versa, resulting in minimal net improvement in binding affinity (ΔG) despite significant structural modifications [28]. This compensation phenomenon represents a critical pitfall in rational drug design, frustrating optimization efforts by effectively creating a thermodynamic "ceiling" that limits affinity gains.

Understanding EEC is particularly crucial when validating thermodynamic stability through phase diagram analysis in complex biological systems. Just as computational materials scientists use tools like PhaseForge to predict phase stability in high-entropy alloys by integrating machine learning potentials with thermodynamic databases [29], drug discovery researchers must account for similar thermodynamic principles when optimizing lead compounds. The prevalence of EEC in aqueous solutions, especially those involving biological macromolecules, underscores its fundamental importance in pharmaceutical development [30]. This review examines the evidence for EEC, its physical origins, experimental characterization, and strategic approaches to mitigate its impact on lead optimization campaigns.

The Physical Basis and Evidence of Compensation

Fundamental Thermodynamic Principles

The binding affinity of a ligand to its biological target is governed by the Gibbs free energy equation:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

Where ΔG represents the binding free energy, ΔH the enthalpy change, T the absolute temperature, and ΔS the entropy change [28]. In thermodynamic terms, the enthalpic component (ΔH) quantifies changes in heat associated with binding, primarily reflecting the formation of favorable non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces). The entropic component (-TΔS) quantifies changes in system disorder, encompassing both the ligand and receptor conformational entropy and solvation effects [28].

Entropy-enthalpy compensation occurs when ligand modifications produce a favorable enthalpic change (ΔΔH) that is partially or fully offset by an unfavorable entropic change (TΔΔS), resulting in minimal net improvement in binding affinity (ΔΔG ≈ 0). For strong compensation, ΔΔH ≈ TΔΔS, with both changes sharing the same sign [28].

Experimental Evidence and Manifestations

Calorimetric studies have provided compelling evidence for EEC in various protein-ligand systems. A striking example comes from HIV-1 protease inhibitor optimization, where introducing a hydrogen bond acceptor resulted in a 3.9 kcal/mol enthalpic gain that was completely offset by a compensating entropic penalty, yielding no net affinity improvement [28]. Similar compensation has been observed in trypsin inhibitors, where para-substituted benzamidinium derivatives showed large enthalpic and entropic variations with nearly constant binding free energy [28].

Meta-analyses of protein-ligand binding thermodynamics further support the prevalence of EEC. An analysis of approximately 100 protein-ligand complexes from the BindingDB database revealed a linear relationship between ΔH and TΔS with a slope接近 1, characteristic of compensation behavior [28]. This phenomenon appears fundamental to processes in aqueous solutions, particularly those involving biological macromolecules, with water playing a pivotal role through its unique hydration thermodynamics [30].

Table 1: Documented Cases of Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation in Lead Optimization

| Target System | Ligand Modification | ΔΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Protease | Introduction of H-bond acceptor | -3.9 | +3.9 | ~0 | [28] |

| Trypsin | para-substituted benzamidinium | Variable | Compensatory | Minimal | [28] |

| Calcium-binding proteins | Various modifications | Large variations | Compensatory | Minimal | [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Compensation

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Methodology

Protocol Overview: ITC represents the gold standard for characterizing binding thermodynamics as it directly measures the heat changes associated with molecular interactions in solution. Modern microcalorimeters can simultaneously determine the association constant (K~a~), enthalpy change (ΔH), and binding stoichiometry (n) in a single experiment, from which ΔG and TΔS can be derived [28].

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely degas all solutions to eliminate air bubbles that interfere with thermal measurements. The protein/buffer system should be meticulously matched to avoid heats of dilution artifacts.

- Experimental Setup: Load the sample cell with target protein (typically 10-100 μM) and the syringe with ligand solution (typically 10-20 times higher concentration). Maintain constant stirring (250-300 rpm) to ensure rapid mixing.

- Titration Protocol: Program a series of injections (typically 10-25 injections of 1-10 μL each) with sufficient time between injections (180-300 seconds) for the signal to return to baseline.

- Data Analysis: Integrate the heat peaks from each injection and fit the binding isotherm to an appropriate model to extract K~a~, ΔH, and n. Calculate ΔG = -RTlnK~a~ and TΔS = ΔH - ΔG.

Critical Considerations: ITC measurements are particularly valuable when performed across a temperature series, enabling heat capacity (ΔC~p~) determinations that provide additional insight into binding mechanisms [28]. However, researchers must be aware of the significant correlation between errors in measured entropic and enthalpic contributions, which can create the appearance of compensation where none exists [28].

Integrating Thermodynamic Characterization with Structural Biology

Complementary Approaches:

- X-ray Crystallography: Provides atomic-level structural context for thermodynamic observations, revealing structural basis for enthalpic gains (e.g., new hydrogen bonds) and entropic penalties (e.g., conformational restriction).

- Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA): Validates target engagement in physiologically relevant environments (intact cells, tissues) by measuring thermal stabilization of drug-target complexes [31].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Captures the dynamic behavior of protein-ligand complexes and solvation changes that contribute to entropic components.

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for characterizing entropy-enthalpy compensation combining experimental and computational approaches.

Computational Strategies to Overcome Compensation

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Calculations