Validating Reaction Energetics with DFT: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating reaction energetics using Density Functional Theory (DFT).

Validating Reaction Energetics with DFT: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating reaction energetics using Density Functional Theory (DFT). It explores the foundational quantum mechanical principles of DFT, details its methodological applications in predicting drug-excipient interactions and reaction mechanisms, addresses troubleshooting common limitations like solvation effects, and outlines rigorous validation and benchmarking strategies against experimental and high-level computational data. The integration of DFT with machine learning and multiscale frameworks is highlighted as a transformative approach for accelerating data-driven formulation design and reducing experimental validation cycles in pharmaceutical development.

Quantum Foundations: Understanding DFT's Core Principles for Energetic Predictions

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a cornerstone of computational quantum chemistry and materials science, providing the fundamental framework for investigating electronic structure in atoms, molecules, and condensed phases. The Hohenberg-Kohn (HK) theorems, established in 1964, form the rigorous mathematical foundation that legitimizes the use of electron density—rather than the complex many-body wavefunction—as the central variable for determining all ground-state properties of a quantum system [1] [2]. This theoretical breakthrough addressed Paul Dirac's earlier observation that while "the underlying physical laws necessary for the mathematical theory of a large part of physics and the whole of chemistry are thus completely known," the exact application of these laws leads to equations far too complicated to be soluble [3]. Before HK, precursor models like the Thomas-Fermi model (1927) and Thomas-Fermi-Dirac model (1930) attempted to use electron density but proved too inaccurate for chemical applications [3].

The revolutionary insight of Hohenberg and Kohn was to prove that a method based solely on electron density could, in principle, be exact [3]. This theoretical validation enabled the development of practical computational methods that have since transformed computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. The subsequent formulation of the Kohn-Sham equations in 1965 provided the practical machinery that made DFT calculations feasible, for which Walter Kohn received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1998 [3]. This guide examines the core principles of the HK theorems, their modern implementations, and their critical role in validating reaction energetics across scientific domains.

Theoretical Framework: The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

The First Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem

The first HK theorem establishes a fundamental one-to-one correspondence between the external potential acting on a many-electron system and its ground-state electron density [1] [2]. For an isolated molecular system with N electrons, the electronic ground state is described by an anti-symmetric N-electron wave function Ψ₀(r₁, r₂, ..., r_N) that satisfies the time-independent Schrödinger equation ĤΨ₀ = E₀Ψ₀, where E₀ is the electronic energy and Ĥ is the electronic Hamiltonian [1]. The Hamiltonian comprises three essential operators:

- Kinetic energy operator (T): Accounts for the motion of electrons

- Electron-electron repulsion operator (U): Describes Coulomb interactions between electrons

- External potential operator (V): Represents attractions between electrons and nuclei, defined for molecular systems as v(r) = -ΣK [ZKe²/(4πε₀|r - RK|)] where ZK is the proton number of atom K at position R_K [1]

The first HK theorem demonstrates that the external potential v(r) is uniquely determined by the ground-state electron density n₀(r), to within an additive constant [1]. Mathematically, this establishes that there exists a unique mapping between the ground-state wave function and its one-electron density, formally expressed as n₀(r) v(r) [4]. Consequently, knowledge of n₀(r) alone is sufficient to determine the ground-state energy and all other ground-state properties of the molecular system [1].

This theorem enables a crucial separation of the total energy functional into distinct components:

Where V[n₀(r)] = ∫v(r)n₀(r)d³r represents the system-dependent external potential contribution, and FHK[n₀(r)] = T[n₀(r)] + U[n₀(r)] is the universal Hohenberg-Kohn functional comprising the kinetic (T) and electron repulsion (U) energy components [1]. The universality of FHK signifies that it has the same functional form for all systems, independent of the specific external potential [1] [2].

The Second Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem

The second HK theorem introduces a variational principle for the electron density, analogous to the variational principle in wave function theory [1]. It states that for any trial electron density ñ₀(r) that is v-representable (meaning it corresponds to some external potential), the ground-state energy E₀ satisfies the inequality:

This provides a rigorous theoretical foundation for determining the ground-state energy through density-based variational minimization [1]. The minimization must be performed over all v-representable densities that satisfy the conditions ∫ñ₀(r)d³r = N and ñ₀(r) ≥ 0 [1].

Mathematical Formulation and Extensions

The original HK theorems were formulated for non-degenerate ground states in the absence of magnetic fields but have since been generalized to encompass these cases [2]. A significant extension came from Levy's constrained-search formulation, which expanded the theory to N-representable densities—those obtainable from some anti-symmetric wave function [1]. This formulation defines a universal variational functional through a constrained minimization over all wave functions yielding a given density:

For v-representable densities, F[n(r)] equals the original HK functional, while for N-representable densities, F[n(r)] + V[n(r)] ≥ E₀, establishing a variational principle with respect to N-representable densities [1]. The minimization condition can be expressed using a Lagrangian multiplier approach:

where the Lagrange multiplier μ represents the chemical potential of the system (μ = dE/dN) [1]. This leads to the stationary condition μ = v(r) + δF[n(r)]/δn(r) [1].

Table 1: Core Components of the Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| First HK Theorem | n₀(r) v(r) | One-to-one mapping between density and external potential |

| HK Energy Functional | E[n₀(r)] = F_HK[n₀(r)] + ∫v(r)n₀(r)d³r | Separation into universal and system-dependent parts |

| Universal Functional | F_HK[n₀(r)] = T[n₀(r)] + U[n₀(r)] | Contains kinetic and electron-electron interaction energies |

| Second HK Theorem | E₀ = min_{ñ₀(r)} E[ñ₀(r)] | Variational principle for electron density |

| Constrained Search Formulation | F[n(r)] = min_{Ψ→n(r)} 〈Ψ|T̂ + Û|Ψ〉 | Extension to N-representable densities |

From Theory to Practice: The Kohn-Sham Equations

Bridging Theory and Practical Computation

While the HK theorems provide a rigorous theoretical foundation, they do not offer a practical computational scheme because the exact form of the universal functional F_HK[n(r)] remains unknown [5]. Specifically, the kinetic energy functional T[n(r)] is particularly challenging to express directly in terms of the density [2]. The Kohn-Sham approach, introduced in 1965, ingeniously circumvented this limitation by replacing the original interacting system with a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that exactly reproduces the same ground-state density [2] [3].

The Kohn-Sham scheme introduces a set of one-electron orbitals {φi} (the Kohn-Sham orbitals) from which the electron density is constructed as n(r) = Σi |φ_i(r)|² [2]. This allows an exact treatment of the kinetic energy for the non-interacting system, with the total energy functional expressed as:

Where:

- T_s[n] is the kinetic energy of the non-interacting electrons

- E_ext[n] = ∫v(r)n(r)d³r is the external potential energy

- E_H[n] = ½∫∫[n(r)n(r')/|r-r'|]d³rd³r' is the Hartree (electrostatic) energy

- E_xc[n] is the exchange-correlation energy functional that captures all remaining electronic interactions [2] [5]

The Kohn-Sham equations are derived by applying the variational principle to this energy expression, resulting in a set of self-consistent one-electron Schrödinger-like equations:

Where the effective potential veff(r) = vext(r) + vH(r) + vxc(r) includes the external, Hartree, and exchange-correlation potentials [2]. The exchange-correlation potential vxc(r) = δExc[n]/δn(r) is the functional derivative of the exchange-correlation energy [2].

The Exchange-Correlation Functional

The accuracy of Kohn-Sham DFT calculations depends entirely on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional E_xc[n] [2] [3]. The search for increasingly accurate functionals has followed what Perdew termed "Jacob's Ladder" of DFT, ascending from basic to more sophisticated approximations [3]:

Table 2: Jacob's Ladder of DFT Exchange-Correlation Functionals

| Rung | Functional Type | Ingredients | Representative Examples | Accuracy/Speed Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Local density n(r) | SVWN5 | Fast but inaccurate for molecules |

| 2 | Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Density + gradient | PBE, BLYP | Reasonable accuracy, widely used |

| 3 | Meta-GGA | Density + gradient + kinetic energy density | TPSS, SCAN | Improved accuracy for diverse systems |

| 4 | Hybrid | GGA + exact Hartree-Fock exchange | B3LYP, PBE0 | Good accuracy, computational expense |

| 5 | Double Hybrid | Hybrid + perturbative correlation | B2PLYP | High accuracy, significant cost |

The local density approximation (LDA), introduced alongside the Kohn-Sham equations, assumes the exchange-correlation energy at point r depends only on the density at that point: Exc^LDA[n] = ∫n(r)εxc(n(r))d³r, where ε_xc is the exchange-correlation energy per particle of a uniform electron gas [3]. While reasonably accurate for simple metals, LDA proved insufficient for chemical applications due to its overbinding tendency and poor description of molecular properties [3].

The development of generalized gradient approximations (GGAs) in the 1980s, which incorporate the density gradient ∇n(r) in addition to the density itself, marked a significant improvement, making DFT useful for chemical applications [3]. Hybrid functionals, introduced by Becke in 1993, mix a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with GGA exchange and correlation, further improving accuracy for many chemical systems [3].

Experimental Validation and Computational Protocols

Validating DFT Predictions Against Experimental Data

The accuracy of DFT methodologies grounded in the HK framework must be rigorously validated against experimental data. A recent innovative approach integrates whispering-gallery mode (WGM) microresonators with gold nanorods to enable real-time, label-free detection of molecular interactions at single-molecule sensitivity [6]. In a study examining glyphosate binding to gold nanorods across a pH gradient, researchers bridged WGM sensing with DFT calculations to resolve pH-dependent binding kinetics and thermodynamics [6]. The DFT framework, validated against experimental resonance shifts and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy data, successfully quantified interaction energies and revealed competition between glyphosate and buffer molecules for gold surface sites [6]. The strong agreement between computational predictions and experimental observations validated the molecular-level mechanisms of these interactions, demonstrating the robustness of properly parameterized DFT methods [6].

Computational Protocols for Drug Discovery Applications

In pharmaceutical research, DFT calculations are typically performed using software packages like Material Studio with the DMol³ module [7]. Standard protocols employ the B3LYP hybrid functional with the 6-31G(d,p) basis set, which incorporates a mixture of Hartree-Fock exchange with density functional exchange and correlation [7]. These calculations generate optimized molecular geometries and key electronic properties including [7]:

- Highest Occupied and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO-LUMO) energies

- Electron density mapped with electrostatic potential (ESPM)

- Density of states (DOS) plots

- Various thermodynamic parameters (dipole moment, zero-point vibrational energy, molar entropy, heat capacity, etc.)

These DFT-derived parameters are subsequently correlated with molecular structure descriptors through Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) analysis [7]. Topological indices such as the Wiener index, Gutman index, and Harary index serve as structural descriptors that capture essential molecular connectivity patterns [7]. Curvilinear regression models, particularly quadratic and cubic fitting, have demonstrated enhanced prediction capability for analyzing thermodynamical properties of drugs compared to simple linear models [7].

Comparative Analysis: DFT Alternatives and Enhancements

Neural Network Potentials and Machine Learning Approaches

While DFT represents a significant computational advantage over wavefunction-based methods like Hartree-Fock and post-Hartree-Fock approaches, recent years have witnessed the emergence of neural network potentials (NNPs) as efficient alternatives to direct DFT calculations [8]. The EMFF-2025 model, for instance, is a general NNP for C, H, N, O-based high-energy materials that leverages transfer learning with minimal data from DFT calculations [8]. This approach achieves DFT-level accuracy in predicting structures, mechanical properties, and decomposition characteristics while offering superior computational efficiency [8].

Machine learning has also been applied directly to learn the Hohenberg-Kohn map itself [4]. This approach bypasses the need to solve the Kohn-Sham equations by directly learning the functional relationship between external potential and electron density [4]. The machine-learned Hohenberg-Kohn (ML-HK) map can be extended to excited states in a multistate framework (ML-MSHK), allowing simultaneous prediction of excited-state densities and energies with comparable accuracy to the ground state [4]. This development opens the door to highly efficient excited-state dynamics simulations, as demonstrated in studies of excited-state intramolecular proton transfer in malonaldehyde [4].

Novel Theoretical Frameworks

A recent theoretical development proposes an independent atom reference state as an alternative to the conventional independent electron reference state in DFT [9]. This approach uses atoms rather than electrons as fundamental units, providing a more realistic approximation that requires less processing power [9]. When validated on diatomic molecules (O₂, N₂, F₂), this method reproduced bond lengths and energy curves with accuracy comparable to established quantum methods, performing particularly well for separated atoms where many conventional models fail [9].

Another innovation, spherical DFT, reformulates the classic HK theorems by replacing the total electron density with a set of sphericalized densities constructed by spherically averaging the total electron density about each atomic nucleus [10]. For Coulombic systems, this set of sphericalized densities uniquely determines the total external potential, exactly as in standard Hohenberg-Kohn DFT [10]. This approach provides a rationale for using sphericalized atomic basis densities when designing classical or machine-learned potentials for atomistic simulation [10].

Table 3: Comparison of Computational Methods for Electronic Structure

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Computational Scaling | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock | Wavefunction theory | N³-N⁴ | Well-defined, systematic | No electron correlation, poor accuracy |

| Post-Hartree-Fock | Wavefunction theory | N⁵-N⁷ | High accuracy, systematic | Computationally expensive |

| Kohn-Sham DFT | Hohenberg-Kohn theorems | N³ | Good accuracy/efficiency balance | Exchange-correlation approximation error |

| Neural Network Potentials | Machine learning trained on DFT | N (after training) | High efficiency after training | Training data requirements, transferability |

| Spherical DFT | Modified HK theorems | Similar to DFT | Simplified basis sets | Emerging method, limited validation |

| Independent Atom Reference | Modified reference state | Potentially lower than KS-DFT | Mathematical simplicity | Limited testing on complex systems |

Research Applications and Case Studies

Energetic Materials Design

The EMFF-2025 neural network potential exemplifies how DFT-based approaches accelerate materials discovery [8]. Applied to high-energy materials (HEMs) containing C, H, N, O elements, this model successfully predicts crystal structures, mechanical properties, and thermal decomposition behaviors of 20 different HEMs [8]. Integrating the model with principal component analysis and correlation heatmaps enabled researchers to map the chemical space and structural evolution of these materials across temperatures [8]. Surprisingly, the simulations revealed that most HEMs follow similar high-temperature decomposition mechanisms, challenging conventional views of material-specific behavior [8]. This application demonstrates how DFT-level accuracy, when combined with efficient sampling algorithms, can provide fundamental insights into material behavior across conditions difficult to access experimentally.

Drug Development and Chemotherapy Optimization

DFT-based structural modeling has proven valuable in pharmaceutical development, particularly in optimizing chemotherapy drugs [7]. Researchers employ DFT to compute thermodynamical and electronic characteristics of chemotherapeutic agents, then utilize distance-based topological descriptors to assess molecular structure [7]. These descriptors serve in curvilinear regression models to forecast essential thermodynamical attributes and biological activities [7]. Studies have examined drugs including Gemcitabine (DB00441), Cytarabine (DB00987), Fludarabine (DB01073), and Capecitabine (DB01101), correlating their DFT-derived electronic properties with therapeutic efficacy [7]. This approach has demonstrated that curvilinear regression models, especially those with quadratic and cubic curve fitting, markedly enhance prediction capability for analyzing thermodynamical properties of drugs [7].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DFT Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Software Packages | Material Studio (DMol³) | Perform DFT calculations | Electronic structure optimization |

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | B3LYP, PBE, SCAN | Approximate quantum interactions | Balanced accuracy for diverse systems |

| Basis Sets | 6-31G(d,p), def2-TZVP | Represent molecular orbitals | Flexibility in electron distribution description |

| Neural Network Potentials | EMFF-2025, DP-GEN framework | Efficient force field generation | Large-scale molecular dynamics simulations |

| Topological Indices | Wiener index, Gutman index | Molecular structure characterization | QSPR modeling in drug design |

| Validation Tools | WGM microresonators, SERS | Experimental validation of DFT predictions | Single-molecule sensing and binding studies |

Logical Flow of Hohenberg-Kohn to Kohn-Sham Implementation

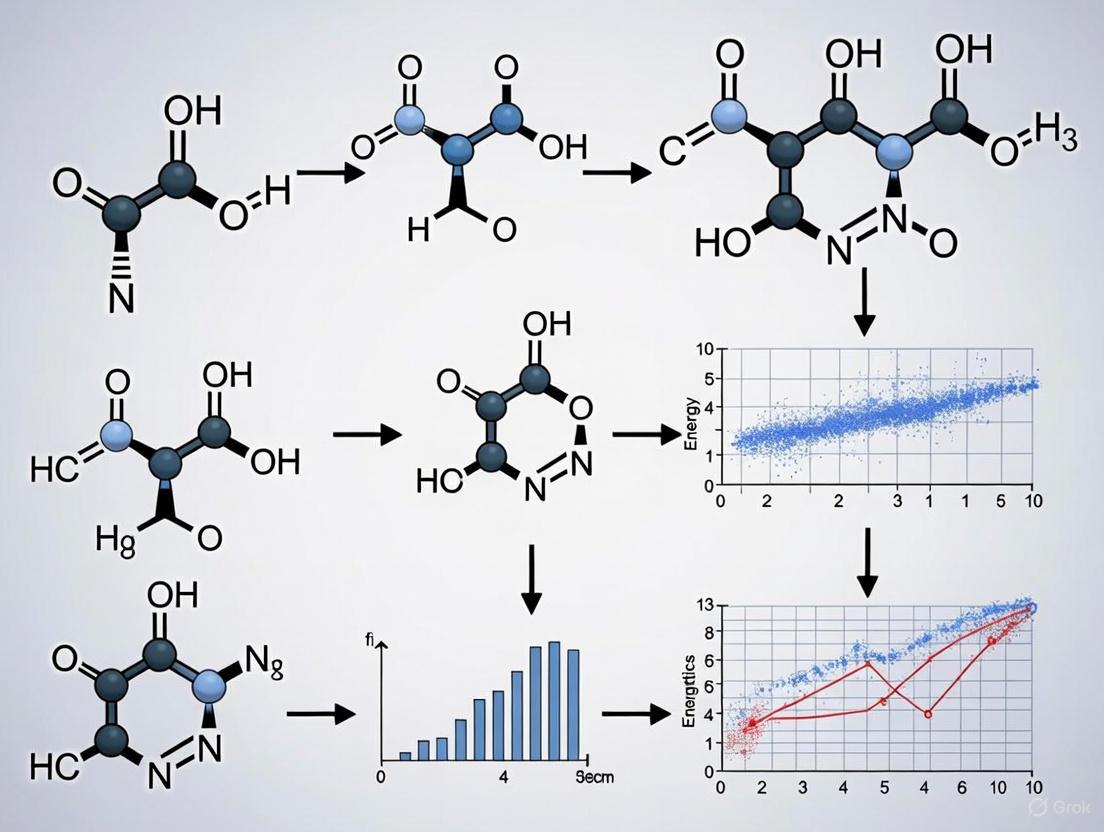

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression from the fundamental Hohenberg-Kohn theorems to practical Kohn-Sham implementation and modern computational applications:

Diagram 1: Logical pathway from Hohenberg-Kohn theorems to computational applications

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems continue to provide the fundamental theoretical foundation for an expanding ecosystem of electronic structure methods. While Kohn-Sham DFT with standard exchange-correlation functionals remains the workhorse for most computational studies of molecular and materials systems, new approaches are pushing the boundaries of accuracy and efficiency [3]. Machine learning techniques are being applied both to learn the HK map directly and to develop neural network potentials that offer DFT-level accuracy at significantly reduced computational cost [8] [4].

Recent theoretical innovations, such as the independent atom reference state and spherical DFT, offer promising alternatives that may overcome limitations of conventional approaches [10] [9]. Meanwhile, advanced experimental validation methods, particularly single-molecule sensing techniques, are providing unprecedented opportunities to test and refine DFT predictions against empirical data [6]. As these developments converge, the accuracy and applicability of density-based computational methods continue to expand, solidifying the legacy of the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems as a transformative contribution to theoretical chemistry and materials science.

The Kohn-Sham equations represent the computational cornerstone of modern density functional theory (DFT), providing a workable framework for solving the electronic structure problem for diverse systems ranging from simple molecules to complex solid-state materials [11]. By transforming the intractable many-body Schrödinger equation into a series of single-electron problems, the Kohn-Sham approach enables practical calculations of quantum mechanical systems while maintaining a rigorous theoretical foundation based on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems [12]. This formal equivalence between the original interacting system and an auxiliary non-interacting system has made DFT, through the Kohn-Sham scheme, one of the most popular and versatile quantum mechanical methods across materials science, chemistry, and drug discovery [13].

In pharmaceutical sciences, where molecular-level precision is increasingly replacing traditional empirical approaches, Kohn-Sham DFT has emerged as a transformative tool for elucidating the electronic nature of molecular interactions [12]. The method's ability to solve electronic structures with precision up to 0.1 kcal/mol enables accurate reconstruction of molecular orbital interactions, providing critical theoretical guidance for optimizing drug-excipient composite systems [12]. For drug development professionals, this quantum mechanical precision offers systematic understanding of complex behaviors in pharmaceutical formulations, addressing the critical challenge that more than 60% of formulation failures for BCS II/IV drugs stem from unforeseen molecular interactions between active pharmaceutical ingredients and excipients [12].

Theoretical Foundations of the Kohn-Sham Equations

Mathematical Formalism

The Kohn-Sham equation for the electronic structure of matter is given by:

[\left( -\frac{\hbar^2\nabla^2}{2m} + V{\text{pion}}(\mathbf{r}) + VH(\mathbf{r}) + V{\text{xc}}[\rho(\mathbf{r})] \right) \phii(\mathbf{r}) = Ei \phii(\mathbf{r}) \quad [11]]

Here, (V{\text{pion}}) represents the ion core pseudopotential, (VH) is the Hartree or Coulomb potential, and (V_{\text{xc}}) is the exchange-correlation potential [11]. The Hartree potential is obtained from the Poisson equation:

[\nabla^2 V_H(\mathbf{r}) = -4\pi e \rho(\mathbf{r}) \quad [11]]

where the electron charge density (\rho(\mathbf{r})) is constructed from the Kohn-Sham orbitals:

[\rho(\mathbf{r}) = -e \sum{i,\text{occup}} |\phii(\mathbf{r})|^2 \quad [11]]

The summation extends over all occupied states, which correspond to valence states when pseudopotentials are employed [11].

The Self-Consistent Field Cycle

The Kohn-Sham equations are solved using a self-consistent field (SCF) approach, which iteratively refines the solution until convergence is achieved [11] [12]. This systematic procedure ensures that the input and output charge densities (or potentials) become identical within a prescribed tolerance, yielding consistent ground-state electronic structure parameters [12].

The following diagram illustrates the iterative SCF cycle for solving the Kohn-Sham equations:

Computational Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Traditional Approaches to Solving the Kohn-Sham Equations

Various computational methodologies have been developed to solve the Kohn-Sham equations, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and application domains. The choice of method depends on factors including system size, chemical complexity, and desired accuracy.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Computational Methods for Solving Kohn-Sham Equations

| Method | Key Features | Accuracy Considerations | Computational Cost | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Potential Linear Muffin-Tin Orbital (FP-LMTO) | No geometrical constraints on effective potential; employs Bloch's theorem for periodic systems [11] | High accuracy; total energy error <0.1 eV/atom in favorable cases [11] | Moderate to high | Bulk materials, surface systems, accurate property prediction |

| Muffin-Tin Approximation | Potential assumed spherically symmetric inside atomic regions and constant in-between [11] | Introduces errors up to 1 eV in total energy for 5d transition metals [11] | Lower than full-potential | High-throughput screening, initial structural optimization |

| Atomic Sphere Approximation (ASA) | Replaces Veff with spherically symmetric potentials in space-filling spheres [11] | Accuracy approaching full-potential methods [11] | Relatively fast | Complex alloys, systems with high atomic packing density |

| Jellium Model | Smears out ionic charge into homogeneous positive background; disregards atomic structure [11] | Qualitative for simple metals; misses chemical specificity [11] | Low | Simple metal clusters, educational purposes, initial explorations |

Advanced and Machine Learning Approaches

Recent methodological innovations have substantially expanded the toolkit available for electronic structure calculations, particularly through machine learning acceleration and hybrid approaches.

Table 2: Emerging and Machine Learning Methods for Electronic Structure Calculations

| Method | Key Innovation | Accuracy Performance | Speed Advantage | Applications Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Modeling AI Framework | Linear ensemble of 147 disparate ML models trained on DFT data [14] | Accurate KS total energy prediction for TiO₂ nanoparticles [14] | Orders of magnitude faster than traditional DFT [14] | Nanoparticle property prediction, temperature-dependent studies |

| Neural Network Surrogate Models | Maps atomic environment to electron density and LDOS using rotationally invariant fingerprints [13] | Remarkable verisimilitude for Al and polyethylene systems [13] | Strictly linear-scaling with system size [13] | Large systems, molecular dynamics with electronic structure |

| Meta's eSEN Models | Transformer-style architecture with equivariant spherical-harmonic representations [15] | Exceeds previous state-of-the-art NNP performance [15] | Conservative-force training reduces wallclock time by 40% [15] | Biomolecules, electrolytes, metal complexes |

| Universal Models for Atoms (UMA) | Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) architecture for multi-dataset training [15] | Matches high-accuracy DFT performance on molecular energy benchmarks [15] | Knowledge transfer across datasets improves data efficiency [15] | Universal applications across chemical space |

Exchange-Correlation Functionals: Performance Benchmarks

The accuracy of Kohn-Sham DFT calculations critically depends on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional. Different functionals offer varying trade-offs between accuracy, computational cost, and applicability across diverse chemical systems.

Table 3: Comparison of Exchange-Correlation Functionals in Kohn-Sham Calculations

| Functional | Theoretical Rigor | Accuracy Domains | Known Limitations | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Based on homogeneous electron gas [12] | Metallic systems, crystal structures [12] | Poor description of weak interactions (hydrogen bonding, van der Waals) [12] | Simple metals, bulk structural properties |

| Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Incorporates density gradient corrections [11] [12] | Molecular properties, hydrogen bonding systems, surfaces/interfaces [12] | Underestimates band gaps; limited for strongly correlated systems [12] | Most molecular systems, surface adsorption studies |

| Hybrid Functionals (B3LYP, PBE0) | Mixes Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation [12] [7] | Reaction mechanisms, molecular spectroscopy [12] | Higher computational cost; grid dependence for numerical integration [12] | Molecular thermochemistry, reaction barrier prediction |

| meta-GGA | Incorporates kinetic energy density [12] | Atomization energies, chemical bond properties, complex molecular systems [12] | Implementation complexity; limited availability in some codes | Detailed bond analysis, systems with intermediate correlation |

| ωB97M-V | Range-separated meta-GGA with nonlocal correlation [15] | Avoids band-gap collapse; accurate for diverse systems [15] | High computational cost; large integration grid requirements [15] | High-accuracy benchmarks, training data for ML models |

| Double Hybrid Functionals (DSD-PBEP86) | Incorporates second-order perturbation theory corrections [12] | Excited-state energies, reaction barrier calculations [12] | Very high computational cost; limited to moderate system sizes | High-accuracy thermochemistry, spectroscopic properties |

Experimental Protocols and Computational Setups

Standard Protocol for Kohn-Sham DFT Calculations in Pharmaceutical Applications

For drug development applications, a typical Kohn-Sham DFT workflow follows these methodical steps:

System Preparation and Geometry Optimization: Initial molecular structures are optimized using semi-empirical methods or molecular mechanics before DFT treatment. For the antineoplastic drug Gemcitabine (DB00441) and related compounds, this typically involves conformational sampling to identify low-energy structures [7].

Electronic Structure Calculation: The Kohn-Sham equations are solved using hybrid functionals such as B3LYP with basis sets like 6-31G(d,p) implemented in software packages like Materials Studio [7]. The SCF procedure is run with convergence criteria of 10⁻⁶ Ha for energy and 0.002 Ha/Å for forces.

Property Evaluation: Key electronic properties including HOMO-LUMO energies, electrostatic potential maps, density of states, and orbital populations are computed from the converged Kohn-Sham solution [7]. Fukui functions may be calculated for reactivity analysis [12].

Solvation Effects: Continuum solvation models such as COSMO are employed to simulate polar environmental effects on drug release kinetics, providing critical thermodynamic parameters (e.g., ΔG) for controlled-release formulation development [12].

Validation: Results are benchmarked against experimental data or higher-level theoretical calculations when available. For the OMol25 dataset, this validation includes comparison with experimental molecular energies and structural parameters [15].

Machine Learning-Accelerated Workflow

The integration of machine learning with Kohn-Sham DFT follows a distinct protocol:

Reference Data Generation: High-quality DFT calculations are performed on diverse chemical systems. The OMol25 dataset, for instance, contains over 100 million quantum chemical calculations requiring 6 billion CPU-hours, performed at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory [15].

Feature Engineering: Rotationally invariant representations encode atomic environments around grid-points. This includes scalar, vector, and tensor invariants derived from Gaussian functions of varying widths centered on grid-points [13].

Model Training: Neural networks with multiple hidden layers (e.g., 3 layers with 300 neurons each) learn the mapping between atomic environment fingerprints and electronic structure properties [13].

Prediction and Validation: The trained models predict electronic structures for new systems, with rigorous validation against held-out DFT data. Successful models achieve essentially perfect performance on molecular energy benchmarks [15].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow:

Successful implementation of Kohn-Sham calculations requires careful selection of computational "reagents" - the software, pseudopotentials, and numerical settings that constitute the practical toolkit for electronic structure simulations.

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Kohn-Sham Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Software Packages | Materials Studio [7], DFTB+ [14] | Provides implementations of Kohn-Sham solver with various functionals and basis sets | Varying scalability; GPU acceleration increasingly important for large systems |

| Pseudopotentials | Norm-conserving, ultrasoft, PAW datasets [16] | Replace core electrons with effective potential; reduce computational cost | Quality significantly impacts accuracy; atomic-level adjustment reduces errors [16] |

| Basis Sets | 6-31G(d,p) [7], def2-TZVPD [15] | Mathematical functions to represent Kohn-Sham orbitals | Larger basis sets improve accuracy but increase computational cost exponentially |

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | B3LYP [7], ωB97M-V [15], PBE [12] | Approximate the quantum mechanical exchange-correlation energy | Functional choice often dominates error budget; system-specific selection crucial |

| Neural Network Potentials | eSEN models [15], UMA architectures [15] | Machine-learned surrogates for DFT potential energy surfaces | Conservative-force models provide better molecular dynamics behavior [15] |

| Solvation Models | COSMO [12], PCM, SMD | Simulate solvent effects through continuum dielectric models | Critical for pharmaceutical applications; parametrization affects transferability |

The diverse methodologies for solving the Kohn-Sham equations present researchers with a spectrum of options balancing accuracy, computational efficiency, and application specificity. Traditional approaches like FP-LMTO offer high accuracy for material systems, while emerging machine learning techniques provide unprecedented speedups for large systems and high-throughput screening. For drug development professionals, the strategic selection of computational protocols depends critically on the specific application: formulation stability optimization benefits from hybrid functional accuracy with solvation models, while binding site identification may prioritize electrostatic potential mapping through efficient GGA calculations. The ongoing integration of multiscale computational paradigms, particularly through machine learning potentials trained on massive datasets like OMol25, promises to further expand the accessibility and application scope of Kohn-Sham DFT across pharmaceutical sciences and materials engineering. As these methodologies continue to evolve, the core Kohn-Sham framework remains indispensable for connecting fundamental quantum mechanics with practical material and molecular design challenges.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become a cornerstone computational method in quantum chemistry, providing powerful capabilities for predicting key molecular properties such as bond lengths, vibrational frequencies, and orbital energies. The accuracy of these outputs is critical for validating reaction energetics in research fields ranging from drug discovery to materials science. This guide compares the performance of different DFT methodologies in calculating these essential properties, providing a structured overview of protocols, benchmarks, and practical applications.

Methodological Protocols for DFT Calculations

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

DFT is a computational method based on quantum mechanics that describes the properties of multi-electron systems through electron density, avoiding the complexity of directly solving the Schrödinger equation [12]. The Hohenberg-Kohn theorem establishes that ground-state properties are uniquely determined by electron density [12]. Practical implementations typically use the Kohn-Sham equations, which reduce the multi-electron problem to a single-electron approximation by using a framework of non-interacting particles to reconstruct the electron density distribution of the real system [12]. The typical computational workflow involves several key steps that transform molecular structure inputs into validated quantum mechanical outputs.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

DFT calculations require careful selection of computational parameters, which function similarly to research reagents in experimental protocols. The table below details these essential "research reagents" and their functions in calculating molecular properties.

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | Approximate electron interactions; critically determine accuracy [12] [17] | GGA (PBE), Hybrid (B3LYP, PBE0), Double Hybrid (DSD-PBEP86) [12] [17] |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical functions representing electron orbitals; size affects precision [12] | 6-311G(d,p), cc-pVDZ, correlation-consistent basis sets [18] |

| Dispersion Corrections | Account for weak van der Waals forces missing in standard functionals [18] | Grimme's DFT-D3 with Becke-Johnson damping (D3(BJ)) [18] |

| Solvation Models | Simulate solvent effects on molecular structure and reactivity [12] [18] | Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM), COSMO [12] [18] |

| Software Platforms | Implement numerical algorithms for solving Kohn-Sham equations [18] | Gaussian 09, Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, ORCA [18] |

Performance Comparison of DFT Methodologies

Assessment of Bond Length Calculations

Bond length predictions are fundamental for validating molecular geometry. A systematic study assessed the performance of seven exchange-correlation functionals for predicting bond lengths of 45 diatomic molecules containing atoms from Li to Br [17]. The results demonstrate significant variation in accuracy depending on the functional chosen and the chemical system studied.

| Computational Method | Functional Type | Average Bond Length Error (Å) (Excluding Alkali Dimers) | Average Bond Length Error (Å) (All 45 Diatomics) | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/4 Functional | Hybrid | Not reported | Best overall performance | Particularly accurate for alkali metal dimers [17] |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | ~0.014 [17] | ~0.014 [17] | Comparable to MP2 for general accuracy [17] |

| MP2 | Post-Hartree-Fock | ~0.014 [17] | ~0.014 [17] | Reference ab initio method [17] |

| B97-2 | Hybrid | ~0.014 [17] | ~0.017 [17] | Good general performance [17] |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | ~0.016 [17] | ~0.019 [17] | Popular choice but errors increase with alkali metals [17] |

| HCTH407 | GGA | ~0.020 [17] | ~0.023 [17] | Moderate performance [17] |

| PBE | GGA | ~0.020 [17] | ~0.022 [17] | Moderate performance [17] |

| HCTH93 | GGA | ~0.020 [17] | ~0.021 [17] | Moderate performance [17] |

Assessment of Vibrational Frequency Calculations

Vibrational frequencies are sensitive probes of molecular structure and bonding environments. The "ball and spring" model provides an intuitive framework where atoms represent masses connected by bonds acting as springs [19]. According to this model, increasing atomic mass decreases vibrational frequency, while strengthening bonds (increasing spring tension) increases frequency [19]. DFT calculations of harmonic vibrational frequencies show functional-dependent accuracy, with hybrid functionals generally outperforming GGAs [17].

| Computational Method | Functional Type | Typical Frequency Error | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | Hybrid | Lower error vs. GGA [17] | Includes exact Hartree-Fock exchange [12] |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | Lower error vs. GGA [17] | 25% Hartree-Fock exchange mixture [17] |

| GGA Functionals | GGA | Higher error vs. hybrids [17] | Lack of exact exchange [12] |

| DFT-D3 | Dispersion-Corrected | Improved for weak interactions [18] | Accounts for van der Waals forces [18] |

Infrared spectroscopy typically measures vibrational modes in the wavelength range of 2500-25000 nm [19], which corresponds to the mid-infrared region. The energies involved in these vibrational transitions are significantly smaller than those in electronic transitions studied by UV-Vis spectroscopy [19].

Assessment of Orbital Energy Calculations

Orbital energies and electronic properties are essential for understanding chemical reactivity and material behavior. Key outputs include Frontier Molecular Orbital energies (HOMO and LUMO), Density of States (DOS), and band structures, which help predict conductivity and reactive sites [12] [20].

| Computational Method | Bandgap Accuracy | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA/GGA | Underestimates by ~40% [20] | Fast computation; good for metals [12] | Systematic bandgap error [20] |

| Hybrid (HSE06, B3LYP) | High accuracy [20] | Improved electronic properties [12] [20] | Higher computational cost [12] |

| Meta-GGA | Moderate to high [12] | Good for complex systems [12] | Functional-dependent performance [12] |

| Double Hybrid | High [12] | Includes perturbation theory [12] | Very high computational cost [12] |

The Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) and Average Local Ionization Energy (ALIE) are critical parameters for predicting drug-target binding sites, identifying electron-rich (nucleophilic) and electron-deficient (electrophilic) regions [12]. Projected DOS (PDOS) analysis enables assessment of contribution weights from specific atomic orbitals and reveals orbital hybridization characteristics that influence conductivity and magnetic properties [20].

Advanced Applications and Integration Frameworks

Drug Development Applications

DFT has demonstrated significant utility in pharmaceutical research, particularly through the calculation of bond lengths, vibrational frequencies, and orbital energies to optimize drug formulations and delivery systems.

Drug-Biopolymer Interactions: A dispersion-corrected DFT study (B3LYPD3(BJ)/6-311G) of the Bezafibrate-pectin complex revealed strong hydrogen bonding with bond lengths of 1.56 Å and 1.73 Å, and an adsorption energy of -81.62 kJ/mol, confirming favorable binding for drug delivery applications [18].

Solid Dosage Form Optimization: DFT clarifies electronic driving forces governing API-excipient co-crystallization, predicting reactive sites and guiding stability-oriented co-crystal design with accuracy up to 0.1 kcal/mol in energy calculations [12].

COVID-19 Drug Modeling: DFT has been extensively applied to study electronic properties of potential SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors, calculating frontier orbital energies and molecular electrostatic potentials to predict binding interactions and reaction mechanisms with viral proteins [21].

Multiscale Integration and AI Enhancements

The integration of DFT with other computational methods and artificial intelligence represents the cutting edge of computational chemistry, addressing fundamental limitations while expanding application scope.

Recent initiatives like the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset provide unprecedented resources for training AI models, containing over 100 million 3D molecular snapshots with DFT-calculated properties [22]. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) trained on such DFT data can predict properties with DFT-level accuracy but approximately 10,000 times faster, enabling simulations of large atomic systems previously out of computational reach [22].

The calculated outputs of bond lengths, vibrational frequencies, and orbital energies form a critical triad for validating reaction energetics in DFT research. Accuracy in predicting these properties establishes confidence in computational models of reaction mechanisms, transition states, and catalytic processes. The systematic comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that functional selection profoundly influences results, with hybrid functionals like PBE0 and B3LYP generally providing superior accuracy for molecular properties, particularly when enhanced with dispersion corrections. The ongoing integration of DFT with machine learning and multiscale simulation frameworks promises to further expand the scope and accuracy of computational predictions, solidifying DFT's role as an indispensable tool for validating reaction energetics across chemical and pharmaceutical research.

In the realm of density functional theory (DFT), the exchange-correlation (XC) functional is the pivotal, yet unknown, component that encapsulates the complexities of many-body electron interactions. The accuracy of DFT simulations in predicting reaction energetics, electronic structures, and material properties is profoundly influenced by the choice of the XC functional approximation [23] [24]. This guide provides an objective comparison of XC functional performance across various categories, supported by experimental and benchmarking data, to aid researchers in selecting the appropriate functional for validating reaction energetics in their computational work.

Decoding the Functional Hierarchy: A Guide to Jacob's Ladder

The development of XC functionals is often conceptualized using Perdew's "Jacob's Ladder" classification, where each ascending rung incorporates more physical information into the functional, theoretically leading to increased accuracy [23] [25].

- Local Spin Density Approximations (LSDA): The first rung, LDA uses only the local electron density. It often provides reasonable structural properties but tends to overbind, resulting in underestimated bond lengths and lattice parameters [23] [26].

- Generalized Gradient Approximations (GGA): The second rung improves upon LDA by including the gradient of the electron density. Examples include PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof). While generally more accurate than LDA for molecules, some GGAs can underestimate binding energies on surfaces [23] [24].

- Meta-Generalized Gradient Approximations (meta-GGA): The third rung adds the kinetic energy density, which helps in detecting the local bonding character (e.g., atoms, bonds, and surfaces). This allows meta-GGAs to simultaneously improve performance for reaction energies and lattice properties [24].

- Hybrid Functionals: The fourth rung mixes in a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with semi-local DFT exchange. Range-Separated Hybrids (RSH) use a distance-dependent mix. Hybrids can significantly improve the description of molecular thermochemistry but at a higher computational cost [23].

- Double Hybrids: The fifth rung incorporates a perturbation theory-based correlation correction on top of hybrid exchange, pushing the accuracy closer to high-level ab initio methods [23].

Table 1: Categories of Exchange-Correlation Functionals and Their Key Characteristics.

| Functional Rung | Key Ingredients | Example Functionals | General Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSDA | Local electron density | SVWN | Tends to overbind, underestimating lattice parameters [26]. |

| GGA | Density + its gradient | PBE [24], BLYP | Better than LDA for molecules; can underbind on surfaces [24]. |

| meta-GGA | Density, gradient, kinetic energy density | SCAN [23], TPSS [23], MCML [24] | Can offer a good balance for diverse properties like reaction energies and bulk materials [24]. |

| Hybrid | Adds exact HF exchange to semi-local | B3LYP, PBE0 | Improved molecular thermochemistry and band gaps; higher cost [23]. |

| Double Hybrid | Adds PT2 correlation to hybrid | — | Among the most accurate in DFT; highest computational cost [23]. |

Comparative Performance Analysis: Key Metrics

The performance of an XC functional is not universal; it varies significantly depending on the chemical system and property under investigation. The following data summarizes key findings from comparative studies.

Electronic Structure and Magnetic Properties in Solids

A first-principles study on the L1₀-MnAl compound, a rare-earth-free permanent magnet material, highlights the functional dependence for solid-state properties.

- Lattice Parameters: GGA (PBE) showed closer agreement with reported theoretical lattice parameters, while LDA tended to underestimate them [26].

- Electronic and Magnetic Structure: The study concluded that the calculated electronic structure and magnetic properties, including magnetic moments, were significantly influenced by the choice of XC functional [26].

Table 2: Functional Performance in a Solid-State Study of L1₀-MnAl [26].

| Functional | Lattice Parameter (Å) | Magnetic Moment (μB/Mn) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | Underestimated | Differed from GGA | Different electronic structure and density of states vs. GGA. |

| GGA (PBE) | Good agreement with theory | Differed from LDA | Different electronic structure and density of states vs. LDA. |

Surface Chemistry and Binding Energies

For processes like catalysis, the accurate prediction of adsorption energies is critical. A benchmarking study evaluated the performance of various GGAs and meta-GGAs for binding energies on transition metal surfaces against experimental data.

- Error Range: The mean absolute error for chemisorption and physisorption binding energies varied significantly across different functionals [24].

- Top Performers: The machine-learned MCML meta-GGA functional demonstrated the lowest combined error for both chemisorption and physisorption binding energies among the tested functionals [24].

Strong Correlation and the Challenge of Static Correlation

Standard DFT functionals struggle with strongly correlated systems characterized by significant multi-reference character (static correlation). A hybrid approach combining KS-DFT with 1-electron Reduced Density Matrix Functional Theory (DFA 1-RDMFT) has been developed to address this at a mean-field computational cost [23] [27].

- Methodology: This method uses a reduced density matrix functional to capture strong correlation and a standard XC functional to capture the remaining dynamical correlation [23].

- Benchmarking: A systematic benchmark of nearly 200 XC functionals within the DFA 1-RDMFT framework identified optimal functionals for this hybrid approach and revealed fundamental trends in how different functionals respond to strong correlation [23] [27].

Experimental & Benchmarking Protocols

The comparative data presented herein relies on rigorous computational protocols. Reproducibility is key for validation.

- Software: Calculations performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP).

- XC Functionals: LDA (Ceperley-Alder parameterized by Perdew and Zunger) and GGA (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof - PBE).

- Geometry Relaxation: Structures are relaxed until forces on atoms are below 0.01 eV/Å.

- Plane-Wave Cutoff: A kinetic energy cutoff of 600 eV is used for the plane-wave basis set.

- k-point Sampling: Brillouin zone integration is performed with a Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh.

- Property Calculation: After convergence, electronic structure and magnetic properties are computed from the self-consistent ground state.

- Benchmark Data: Experimental benchmarks for chemisorption and physisorption binding energies on transition metal surfaces are curated from literature.

- DFT Calculations: Binding energies are computed for each XC functional under comparison.

- Error Analysis: The mean absolute error (MAE) and signed errors (over/under-binding) for each functional are calculated against the experimental benchmark set.

- Computational Framework: Calculations are performed using both unrestricted KS-DFT (UKS-DFT) and the hybrid DFA 1-RDMFT approach.

- Functional Library: Nearly 200 XC functionals from the LibXC library are tested.

- System Selection: Performance is evaluated on systems with known strong correlation effects.

- Trend Identification: Errors are analyzed to identify optimal XC functionals for use with DFA 1-RDMFT and to elucidate scaling parameters that describe a functional's response to multi-reference character.

Visualizing Functional Relationships and Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the hierarchical structure of Jacob's Ladder and a typical benchmarking workflow.

Jacob's Ladder of DFT Functionals

XC Functional Benchmarking Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key computational "reagents" and resources used in the development and benchmarking of XC functionals.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources for XC Functional Research.

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| LibXC Library [23] | Software Library | Provides a standardized, extensive collection of ~200 XC functionals. | Systematic benchmarking studies across functional types [23]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Methodology | Trains models to predict the XC energy or improve existing functionals from high-accuracy data. | Creating specialized functionals like NeuralXC [25] or MCML [24] for improved accuracy on target systems. |

| Benchmark Datasets | Data | Curated sets of experimental or high-level ab initio data for key chemical properties. | Used as a reference for training ML functionals [25] or evaluating functional performance [24]. |

| Hybrid 1-RDMFT [23] | Methodology | A hybrid theory combining DFT with Reduced Density Matrix Functional Theory. | Capturing strong correlation effects in systems where standard DFT fails, at mean-field cost [23]. |

DFT in Action: Practical Methods for Predicting Drug Stability and Reaction Pathways

Identifying Reactive Sites with Fukui Functions and Molecular Electrostatic Potentials

Predicting molecular reactivity is a cornerstone of rational drug design and materials science. The ability to accurately identify the most reactive sites within a molecule allows researchers to anticipate reaction pathways, design novel catalysts, and optimize synthetic routes for pharmaceutical compounds. Within the framework of Density Functional Theory (DFT), two powerful complementary tools have emerged for this task: the Fukui Function (FF) and the Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP). The Fukui function describes the local changes in electron density when a system gains or loses electrons, making it a key descriptor in frontier molecular orbital theory. In contrast, the Molecular Electrostatic Potential provides a map of the electrostatic forces a molecule exerts on its surroundings, representing the electrostatic component of chemical reactivity [28]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies, detailing their theoretical foundations, computational protocols, and performance in predicting regioselectivity, particularly for pharmacologically relevant nitrogen heteroarenes undergoing radical C—H functionalization.

The Fukui Function and Molecular Electrostatic Potential probe different, yet complementary, aspects of a molecule's reactivity profile.

Fukui Function (FF): This is a local reactivity descriptor defined as the derivative of the electron density ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ) with respect to the number of electrons ( N ) at a constant external potential ( \nu ): ( f(\mathbf{r}) = \left( \frac{\partial \rho(\mathbf{r})}{\partial N} \right)_\nu ) [28]. In practice, three finite-difference approximations are used to condense the Fukui function onto atomic sites ( \alpha ):

- ( f\alpha^- = q\alpha(N) - q_\alpha(N-1) ): For sites susceptible to electrophilic attack.

- ( f\alpha^+ = q\alpha(N+1) - q_\alpha(N) ): For sites susceptible to nucleophilic attack.

- ( f\alpha^0 = \frac{1}{2} [f\alpha^+ + f_\alpha^-] ): For sites susceptible to radical attack [29]. The atom with the highest condensed Fukui function value is predicted to be the most reactive for the corresponding attack type.

Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP): The MEP, ( V(\mathbf{r}) ), at a point ( \mathbf{r} ) in space is defined as the energy of interaction of a point positive charge (a proton) with the unperturbed charge distribution of the molecule. It provides a visual and quantitative map of regions where a molecule appears most positive (electrophilic) or most negative (nucleophilic) to an approaching reactant [28].

The Radical General-Purpose Reactivity Indicator (R-GPRI): Developed to address limitations of the standard radical Fukui function (RFF), the R-GPRI is an advanced descriptor that incorporates both electrostatic and electron-transfer contributions to reactivity. For a nucleophile-like molecule undergoing electrophilic radical attack, the condensed R-GPRI for atom ( \alpha ) is given by: ( \Xi{\text{nucleophile},\alpha}^0 = (\kappa + 1) q{\text{nucleophile},\alpha}^0 - \Delta N (\kappa - 1) f_{\text{nucleophile},\alpha}^0 ) [29]. The parameters ( \kappa ) and ( \Delta N ) modulate the weight of the charge and Fukui function terms, allowing the model to describe reactions ranging from charge-controlled (( \kappa \approx 1 )) to electron-transfer-controlled (( \kappa \approx -1 )) mechanisms.

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and applying these reactivity descriptors.

Performance Comparison: Fukui Function vs. R-GPRI

While the condensed Radical Fukui Function (RFF) is a straightforward tool for predicting regioselectivity in radical reactions, recent studies show that the R-GPRI offers superior performance, especially for discerning secondary reactive sites.

Quantitative Performance Data

A 2025 comparative study applied both the condensed R-GPRI and condensed RFF to identify the two most reactive atoms in 14 nitrogen heteroarenes subjected to attack by •CF₃ (trifluoromethyl) and •i‑Pr (isopropyl) radicals. The results were benchmarked against experimental data and calculated activation barriers [29].

Table 1: Performance Comparison in Predicting Reactive Sites in Nitrogen Heteroarenes [29]

| Descriptor | Theoretical Foundation | Key Performance Finding (vs. Experiment) | Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical Fukui Function (RFF) | Condensed form ( f_\alpha^0 ), computed via Hirshfeld population analysis. | Similar performance to R-GPRI for predicting the first most reactive atom. | Simple to compute and interpret; standard tool in many computational codes. | Poor performance in predicting the second most reactive site; fails for atoms with large charge but small RFF. |

| Radical General-Purpose Reactivity Indicator (R-GPRI) | ( \Xi{\text{nucleophile},\alpha}^0 ) combining atomic charge ( q\alpha^0 ) and RFF ( f_\alpha^0 ). | Superior for identifying the second major product site; robust for disubstituted heteroarenes. | Appropriately incorporates both charge and frontier-orbital (RFF) contributions. | Performance depends on parameters ( \kappa ) and ( \Delta N ), requiring the construction of Reactivity Transition Tables. |

Case Study: MEP and FF in Catalysis Design

The synergy and contrasting predictions of MEP and FF are exemplified in a study investigating the binding mode of methyl acrylate to Pd- and Ni-diimine catalysts. The preference for π-complexation (active catalyst) over σ-complexation (catalyst poisoning) in the Pd-system was analyzed using both descriptors [28].

Table 2: MEP vs. FF in Predicting Methyl Acrylate Binding Mode [28]

| Descriptor | Prediction for Pd-Catalyst (Active) | Prediction for Ni-Catalyst (Inactive) | Insight Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) | The Pd center is significantly more electrophilic (positive MEP). | The Ni center is less electrophilic. | The more electrophilic Pd center favors interaction with the electron-rich C=C bond of methyl acrylate. |

| Fukui Function for Electron Removal (( f^- )) | The Pd center has a low ( f^- ) value. | The Ni center has a high ( f^- ) value. | A high ( f^- ) on Ni favors coordination from the nucleophilic carbonyl oxygen (σ-complex), poisoning the catalyst. |

| Two-Reactant Fukui Function | Correctly predicts preference for π-complex. | Correctly predicts preference for σ-complex. | Accounts for electronic perturbation between reactants, providing more accurate predictions than single-reactant FF. |

This case highlights that while single-reactant descriptors provide valuable initial insights, their predictions can be misleading. The two-reactant Fukui function, which considers the mutual polarization of the reaction partners, was necessary to correctly predict the binding mode, underscoring the importance of methodology choice [28].

Detailed Computational Protocols

Protocol for Condensed Fukui Function and R-GPRI Analysis

This protocol is tailored for predicting sites of radical attack on nitrogen heteroarenes, as described in the 2025 study [29].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the neutral (N-electron) target molecule, as well as its cation (N-1-electron) and anion (N+1-electron) states using a suitable DFT method (e.g., B3LYP/6-31+G) and a continuum solvation model (e.g., DMSO).

- Population Analysis: For each optimized structure (neutral, cation, anion), perform a Hirshfeld population analysis to compute the atomic charges ( q\alpha(N) ), ( q\alpha(N-1) ), and ( q_\alpha(N+1) ) for all atoms ( \alpha ).

- Compute Condensed Fukui Functions: Calculate the condensed radical Fukui function ( f\alpha^0 ) for each atom using the equation: ( f\alpha^0 = \frac{1}{2}[ (q\alpha(N) - q\alpha(N+1)) + (q\alpha(N-1) - q\alpha(N)) ] ) [29].

- Identify Reactive Sites (RFF): The atom with the highest value of ( f_\alpha^0 ) is predicted as the most susceptible to radical attack. The atom with the second-highest value is the second most reactive.

- Compute Condensed R-GPRI: Using the atomic charges ( q\alpha^0 ) (from the neutral molecule) and the computed ( f\alpha^0 ) values, calculate the R-GPRI ( (\Xi_{\text{nucleophile},\alpha}^0) ) across a range of ( \kappa ) (e.g., -1 to 1) and ( \Delta N ) (e.g., -1 to 0) values. The parameters ( \kappa ) and ( \Delta N ) are associated with the atomic charge and Fukui function of the attacking radical and the extent of electron transfer, respectively [29].

- Construct Reactivity Transition Tables (RTTs): For each combination of ( \kappa ) and ( \Delta N ), identify the atom with the smallest ( \Xi_{\text{nucleophile},\alpha}^0 ) value as the "first choice" and the atom with the second smallest value as the "second choice." Compile these results into RTTs to determine the consensus most reactive sites [29].

Protocol for MEP and Two-Reactant FF Analysis

This protocol, based on the study of catalyst-methyl acrylate complexes, is useful for understanding binding preferences [28].

- System Preparation: Optimize the geometries of the isolated reactants (e.g., the catalyst and methyl acrylate) as well as the proposed complex structures (e.g., π- and σ-complexes).

- Molecular Electrostatic Potential Map: Using the wavefunction of the isolated catalyst, compute and visualize the MEP on a molecular surface (e.g., an electron density isosurface). Regions of low (negative, red) MEP are nucleophilic, while regions of high (positive, blue) MEP are electrophilic.

- Single-Reactant Fukui Function: For the isolated methyl acrylate molecule, compute the Fukui function for electron removal ( f^-(\mathbf{r}) ) and condense it onto atomic sites. This identifies the atoms in the molecule that are most prone to donate electron density.

- Two-Reactant (Charge-Transfer) Fukui Function: For each proposed complex structure, perform a charge sensitivity analysis or the scheme proposed by Korchowiec and Uchimaru [28] to compute the two-reactant Fukui function. This descriptor incorporates the electronic structure of both the catalyst and the ligand in the complexed state.

- Binding Mode Prediction: Compare the computed MEP of the catalyst and the two-reactant FF analysis with the relative energies of the different complexes. The MEP indicates initial electrostatic steering, while the two-reactant FF explains the preferred binding mode after charge transfer and polarization are accounted for.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful application of these predictive models relies on a combination of software, computational methods, and data resources.

Table 3: Key Resources for Reactivity Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Usage Note |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, PySCF) | Performs quantum chemical calculations for geometry optimizations, frequency analysis, and electronic property calculations. | Essential for generating the wavefunction files needed to compute MEP, atomic charges, and Fukui functions. |

| Population Analysis Scheme (Hirshfeld) | Partitions the total electron density of a molecule onto its constituent atoms to compute atomic charges. | The Hirshfeld scheme was found to enhance the performance of the RFF for nitrogen heteroarenes [29]. |

| Continuum Solvation Model (e.g., SMD, COSMO) | Mimics the effect of a solvent environment on the molecular electronic structure. | Crucial for obtaining results relevant to solution-phase chemistry, as used with the DMSO model in [29]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine-learning models trained on high-accuracy DFT data that provide quantum-mechanical quality energies at a fraction of the computational cost. | Models trained on Meta's OMol25 dataset enable rapid computations on large systems like biomolecules [15]. |

| High-Accuracy Dataset (OMol25) | A massive dataset of over 100 million quantum chemical calculations at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory. | Serves as a benchmark and training resource for developing and validating new models and methods [15]. |

| Visualization Software (e.g., VMD, GaussView, Jmol) | Renders 3D molecular structures and properties like MEP maps and Fukui function isosurfaces. | Critical for the intuitive interpretation and presentation of reactivity descriptors. |

The comparative analysis reveals that no single descriptor is universally superior. The Molecular Electrostatic Potential excels in mapping the initial electrostatic steering of a reaction. The Fukui Function provides crucial insight into frontier-orbital controlled, electron-transfer processes. However, for challenging predictions, such as the second reactive site in radical functionalization or the binding mode in catalytic systems, more sophisticated tools are required. The Radical General-Purpose Reactivity Indicator (R-GPRI) demonstrates clear superiority over the standard Radical Fukui Function by synergistically combining charge and orbital control, leading to more robust predictions validated against experimental data. Furthermore, the two-reactant Fukui function proves essential when the electronic structure of the target is significantly perturbed by its reaction partner. For researchers validating reaction energetics with DFT, the strategic selection and application of these complementary descriptors are fundamental to accelerating the discovery and development of new pharmaceutical compounds and catalytic systems.

Modeling API-Excipient Co-crystallization for Solid Dosage Form Stability

In modern pharmaceutical development, co-crystallization has emerged as a powerful crystal engineering strategy to enhance the stability and physicochemical properties of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in solid dosage forms. This approach involves forming crystalline materials comprising API and pharmaceutically acceptable coformers in a defined stoichiometric ratio within the same crystal lattice [30]. Unlike salt formation, which requires ionizable functional groups, co-crystallization can be applied to a wider range of APIs, including those with limited ionization capability [30]. The strategic design of pharmaceutical co-crystals addresses critical stability challenges—particularly for moisture-sensitive compounds—where traditional approaches often fall short [31].

The investigation of co-crystal stability is increasingly grounded in computational modeling, with Density Functional Theory (DFT) providing quantum mechanical insights into the electronic driving forces governing API-excipient interactions [12]. By solving the Kohn-Sham equations with precision up to 0.1 kcal/mol, DFT enables accurate reconstruction of molecular orbital interactions and facilitates stability-oriented co-crystal design through prediction of reactive sites and interaction energies [12] [32]. This molecular-level understanding represents a paradigm shift from empirical trial-and-error approaches toward data-driven formulation design, substantially reducing experimental validation cycles [12].

Computational Foundation: DFT in Co-crystal Modeling

Fundamental Principles of DFT in Pharmaceutical Applications

Density Functional Theory provides a computational method based on quantum mechanics that describes multi-electron systems through electron density rather than wavefunctions [12]. The Hohenberg-Kohn theorem establishes that ground-state properties of a system are uniquely determined by its electron density, while the Kohn-Sham equations reduce the complex multi-electron problem to a more tractable single-electron approximation [12]. The self-consistent field (SCF) method iteratively optimizes Kohn-Sham orbitals until convergence is achieved, yielding critical electronic structure parameters including molecular orbital energies, geometric configurations, vibrational frequencies, and dipole moments [12].

The remarkable accuracy of DFT in modeling co-crystallization phenomena stems from its ability to quantify key interaction types:

- Hydrogen bonding: DFT calculates binding energies and orbital interactions that stabilize co-crystal structures [12]

- van der Waals forces: Critical for predicting co-crystal packing arrangements and stability [12]

- π-π stacking: Important for aromatic API systems, with DFT enabling precise energy calculations [12]

- Electrostatic interactions: Modeled through Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps that identify electron-rich and electron-deficient regions [12]

Functional Selection for Pharmaceutical Co-crystals

The accuracy of DFT calculations depends critically on appropriate functional selection. For co-crystal modeling, different functionals offer specific advantages:

Table 1: DFT Functionals for Co-crystal Applications

| Functional Type | Best Applications in Co-crystal Design | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGA (PBE, BLYP) | Hydrogen bonding systems, molecular property calculations | Accurate for most biomolecular systems; incorporates density gradient corrections | Less accurate for weak interactions |

| Meta-GGA | Atomization energies, chemical bond properties, complex molecular systems | Improved accuracy for diverse molecular systems | Higher computational cost than GGA |

| Hybrid (B3LYP, PBE0) | Reaction mechanisms, molecular spectroscopy | Excellent for reaction energetics and electronic properties | Significant computational resources required |

| Double Hybrid Functionals | Excited-state energies, reaction barrier calculations | Incorporates second-order perturbation theory corrections | Very computationally intensive |

For co-crystal stability prediction, hybrid functionals such as B3LYP often provide the optimal balance between accuracy and computational feasibility when studying API-coformer interactions [12].

Comparative Analysis: Computational Prediction Methods

The rational design of stable co-crystals employs various computational approaches beyond DFT, each with distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications in pharmaceutical development.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Co-crystal Prediction

| Method | Key Features | Accuracy & Information Obtained | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanical Methods (DFT) | Calculates electronic structure; solves Kohn-Sham equations; uses functionals (GGA, hybrid) | High accuracy (up to 0.1 kcal/mol); provides interaction energies, electronic properties, reactivity sites | Very high | Stability prediction; interaction mechanism studies; reaction energetics validation |

| Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) | Analyzes electrostatic potential distribution around molecules | High for predicting interaction sites and complementarity | Medium (when combined with DFT) | Initial coformer screening; hydrogen bonding prediction |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Uses algorithms trained on structural and energetic data | Rapid screening with moderate to high accuracy depending on training data | Low (after training) | High-throughput screening of large coformer libraries |

| Lattice Energy Minimization | Predicts crystal packing by minimizing energy of proposed structures | Moderate to high for crystal structure prediction | Medium | Polymorph prediction; crystal structure determination |

| Solubility Parameter Calculations | Calculates Hansen/Hildebrand solubility parameters | Moderate for miscibility prediction | Low | Preliminary coformer compatibility screening |

Integrated Workflow for Rational Co-crystal Design

A systematic approach combining multiple computational methods provides the most efficient strategy for co-crystal development [33]. The integrated workflow leverages the strengths of each technique while mitigating their individual limitations.

Figure 1: Rational co-crystal design workflow integrating computational and experimental approaches. This systematic process begins with API selection and proceeds through coformer screening, computational prediction, experimental validation, and model refinement [33].

Experimental Validation of Co-crystal Stability

Co-crystal Preparation Methodologies

While computational predictions guide candidate selection, experimental preparation and characterization remain essential for validating co-crystal stability. Several established techniques enable co-crystal synthesis with control over critical material attributes:

- Solution-based crystallization: Traditional method involving solvent evaporation; allows control over crystal habit and size but requires optimization of solvent system [34]

- Hot-melt extrusion: Continuous process applicable to thermostable compounds; enables direct formulation but may lack control over crystal form [34]

- Grinding techniques: Includes neat and liquid-assisted grinding; simple and scalable but may yield variable crystallinity [33]

- Supercritical fluid technology: Uses supercritical CO₂ as anti-solvent; produces high-purity co-crystals with controlled particle size [34]

Recent advances in process optimization have demonstrated enhanced control over co-crystal properties. For instance, quasi-emulsion solvent diffusion-based spherical co-crystallization simultaneously improved both the manufacturability and dissolution of indomethacin, while careful control of supersaturation levels directly influenced final crystal qualities during co-crystallization processes [34].

Stability Assessment Protocols

Comprehensive stability evaluation of pharmaceutical co-crystals involves multiple complementary analytical techniques:

- Hygroscopicity testing: Gravimetric measurement of moisture uptake under controlled humidity; co-crystals often show reduced hygroscopicity compared to pure API [31]

- Chemical stability studies: Monitoring API degradation under stress conditions (elevated temperature, humidity, light); co-crystals typically demonstrate enhanced stability [35]

- Physical stability assessment: Evaluation of polymorphic transitions, crystallinity, and dissociation tendencies during storage and processing [34]

- Dissolution testing: Analysis of dissolution profiles under physiologically relevant conditions; co-crystals often show modified release kinetics [12]

For moisture-sensitive compounds, co-crystallization has proven particularly effective. Studies have documented numerous cases where co-crystals exhibited significantly reduced hygroscopicity compared to pure API, thereby improving product stability and shelf-life [31].

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Successful implementation of co-crystal stability modeling requires specific computational and experimental resources. The following toolkit outlines critical components for comprehensive investigation.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Co-crystal Stability Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | Gaussian | Quantum chemical calculations including DFT | Various electronic structure calculations; molecular property prediction |

| CASTEP | First-principles materials modeling | DFT with plane-wave basis set; periodic boundary conditions | |

| Databases | Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Crystal structure information | Curated repository of experimental crystal structures; interaction analysis |

| ZINC, PubChem | Coformer libraries | Virtual screening of potential coformers | |