Validating Generative AI for Materials Discovery: A DFT-Based Framework for Stability and Property Prediction

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on validating generative models for materials discovery using Density Functional Theory (DFT).

Validating Generative AI for Materials Discovery: A DFT-Based Framework for Stability and Property Prediction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on validating generative models for materials discovery using Density Functional Theory (DFT). It explores the foundational need for robust validation beyond simple metrics, details methodological advances in diffusion models and conditional generation for targeted design, addresses key challenges like data scarcity and computational costs, and establishes rigorous benchmarking and comparative frameworks. By synthesizing current best practices and future directions, it aims to enhance the reliability and adoption of generative AI in accelerating the design of novel functional materials for biomedical and clinical applications.

The Critical Need for Validating Generative Models in Materials Science

In the pursuit of novel materials and drug compounds, generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has emerged as a transformative tool, enabling researchers to explore vast chemical spaces with unprecedented efficiency. The field has largely been dominated by heuristic optimization techniques and autoregressive predictions that prioritize easily calculable metrics such as molecular validity and uniqueness [1]. While these metrics provide a foundational check of model performance, they create a dangerous illusion of progress, often correlating poorly with real-world experimental success. This guide examines the critical limitations of these heuristic approaches through a comparative analysis of validation methodologies, demonstrating why integration with density functional theory (DFT) calculations and prospective experimental validation represents the only path toward reliable molecular and materials design.

The fundamental challenge lies in the disconnect between algorithmic performance and practical utility. As evidenced by real-world case studies, generative models can achieve impressive scores on standard benchmarks while failing to produce functionally useful compounds or materials [2]. This discrepancy stems from the complex, multi-parameter optimization required in actual research environments, where factors such as synthetic feasibility, biological activity, stability, and cost must be balanced simultaneously—considerations largely absent from heuristic metric evaluation [1].

The Validation Hierarchy: From Basic Metrics to Functional Assessment

Limitations of Standard Heuristic Metrics

Traditional metrics for evaluating generative models focus primarily on computational efficiencies rather than practical applications:

- Validity: Measures whether generated structures conform to chemical rules but doesn't assess functionality or novelty [2]

- Uniqueness: Ensures diversity in output but doesn't guarantee improved properties or synthetic accessibility [2]

- Novelty: Assesses structural difference from training data but provides no information about performance advantages [2]

- Fréchet ChemNet Distance: Evaluates distributional similarity to known molecules but correlates poorly with functional potential [1]

These metrics form only the base level of a comprehensive validation hierarchy, essentially serving as necessary filters rather than sufficient indicators of success.

Toward Functional Validation: The DFT Bridge

Density functional theory calculations provide a crucial bridge between heuristic metrics and experimental validation by enabling the assessment of functional properties prior to synthesis. DFT moves beyond structural evaluation to probe electronic properties, stability, and activity—key considerations for practical applications [3] [4]. The integration of DFT into the validation pipeline represents a significant advancement over heuristic-only approaches, though it still operates as a computational proxy rather than final confirmation.

Comparative Analysis: Validation Approaches Across Domains

Performance Comparison of Validation Methodologies

Table 1: Comparative performance of generative model validation approaches across materials science and drug discovery domains

| Validation Method | Materials Science Applications | Drug Discovery Applications | Computational Cost | Predictive Accuracy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heuristic Metrics Only (Validity, Uniqueness) | Limited to structural assessment | Fails to capture bioactivity | Low | Poor for functional prediction | No correlation with experimental outcomes |

| DFT Validation | Successful for superconductor design [3] | Moderate for molecular properties | Medium-High | Good for electronic properties | Limited to computable properties |

| Prospective Experimental | Gold standard for functional materials [3] | Essential for lead optimization [2] | Very High | Direct measurement | Resource intensive and slow |

| Retrospective Time-Split | Not commonly applied | Poor performance (0.03-0.04% recovery) [2] | Medium | Questionable real-world relevance | Artificial benchmark conditions |

Case Study: Superconductor Design with Integrated DFT Validation

A landmark study demonstrating the power of integrated validation utilized a crystal diffusion variational autoencoder (CDVAE) trained on approximately 1,000 superconducting materials from the Joint Automated Repository for Various Integrated Simulations (JARVIS) database [3]. The methodology employed a multi-stage validation process that progressively moved beyond heuristic metrics:

- Initial Generation: The model generated 3,000 novel candidate structures

- ALIGNN Pre-screening: Pre-trained atomistic line graph neural networks provided initial property assessments

- DFT Validation: Top candidates underwent rigorous density functional theory calculations

- Experimental Confirmation: Selected candidates were synthesized and tested

This approach yielded 61 promising candidates through computational screening, with DFT validation successfully identifying materials with predicted high critical temperatures (T_c)—a key functional property that simple validity metrics cannot assess [3]. The success rate of this integrated approach significantly exceeded what would be expected from heuristic metrics alone, demonstrating the critical importance of physics-based validation.

Case Study: Drug Discovery Validation Gap

A comprehensive analysis of generative models in drug discovery revealed a significant disconnect between heuristic performance and practical utility [2]. Using REINVENT—a widely adopted RNN-based generative model—researchers evaluated the ability to recover middle/late-stage project compounds when trained only on early-stage compounds across both public and proprietary datasets:

Table 2: Recovery rates of middle/late-stage compounds from generative models trained on early-stage data

| Dataset Type | Top 100 Compounds | Top 500 Compounds | Top 5000 Compounds | Nearest Neighbor Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Projects | 1.60% | 0.64% | 0.21% | Higher between active compounds |

| In-House Projects | 0.00% | 0.03% | 0.04% | Higher between inactive compounds |

The stark performance difference between public and proprietary data underscores a critical limitation of heuristic validation: public datasets often contain structural biases that make compound recovery appear more feasible than in real-world discovery environments [2]. The near-zero recovery rates in proprietary projects highlight the fundamental challenge of mimicking human drug design through purely algorithmic approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Validation

Integrated DFT Validation Workflow

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive methodology for validating generative models with DFT calculations, adapted from successful implementations in materials science [3]:

Training Data Curation

- Source from established computational databases (JARVIS, Materials Project)

- Include functional properties (e.g., formation energy, band gap, T_c)

- Apply strict quality controls and standardization procedures

Model Training with Multi-Objective Optimization

- Implement architecture-specific training (CDVAE for crystals, RNN/Transformer for molecules)

- Incorporate property prediction heads for joint structure-property learning

- Utilize reinforcement learning for goal-directed generation [1]

Candidate Generation and Screening

- Generate large candidate libraries (thousands of structures)

- Apply validity and uniqueness filters as baseline quality control

- Employ rapid machine learning potentials (ALIGNN) for initial property screening [3]

DFT Validation Protocol

- Perform geometry optimization using established exchange-correlation functionals

- Calculate electronic structure properties relevant to application

- Assess thermodynamic stability through phase diagram analysis

- Compute application-specific properties (e.g., superconducting properties, catalytic activity)

Experimental Validation

- Synthesize top candidates based on DFT predictions

- Measure functional properties under application-relevant conditions

- Compare with baseline materials to establish improvement

Drug Discovery Validation Protocol

For pharmaceutical applications, the following time-split validation protocol provides more realistic assessment than standard benchmarks [2]:

Dataset Preparation

- Collect project data with temporal annotations (early, middle, late stage)

- Include all measured properties (activity, selectivity, ADME, toxicity)

- Process using canonical SMILES and standardized descriptors

Model Training

- Train on early-stage compounds only

- Implement multi-parameter optimization reflecting real-world constraints [2]

- Use appropriate molecular representations (SMILES, SELFIES, graphs)

Prospective Evaluation

- Generate novel compounds predicted to meet late-stage criteria

- Evaluate using medicinal chemistry expertise and computational tools

- Prioritize candidates for synthesis and testing

Experimental Validation

- Synthesize top candidates

- Test in relevant biological assays

- Compare performance to existing compounds and negative controls

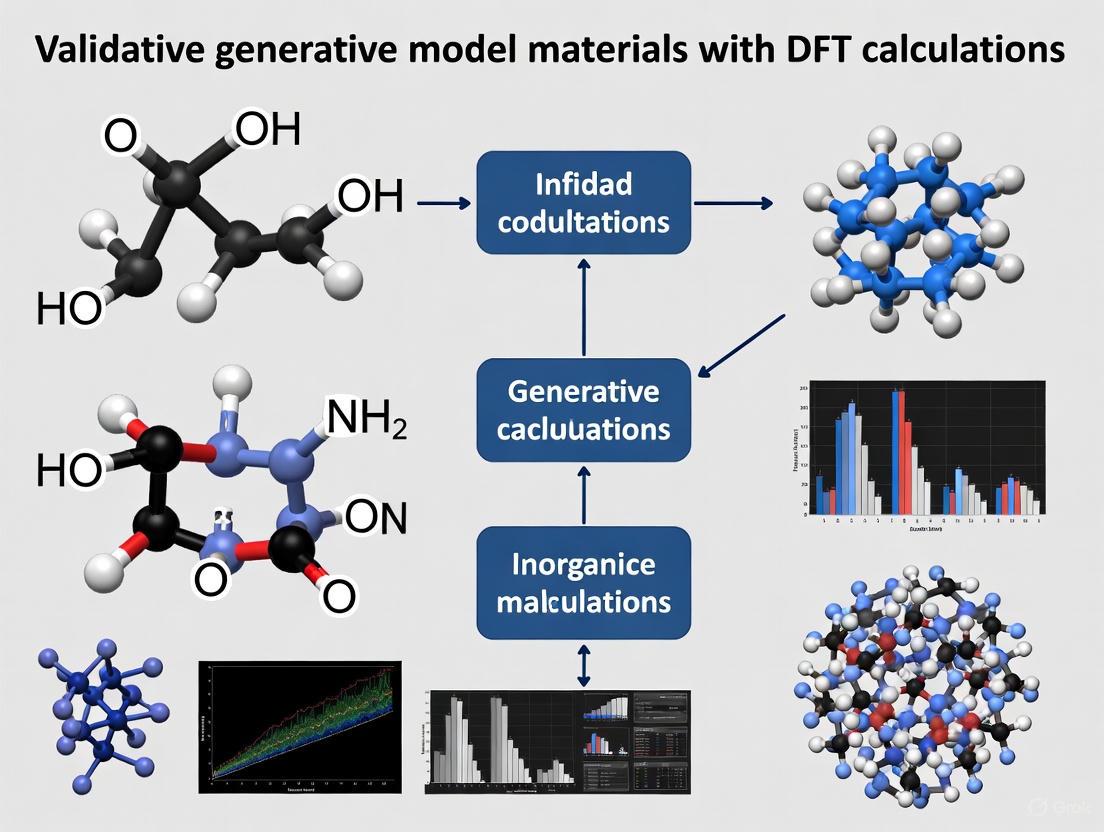

Visualization of Workflows

Integrated Generative AI and DFT Validation Pipeline

Drug Discovery Validation Challenge

Table 3: Essential resources for rigorous generative model validation in materials and drug discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function in Validation Pipeline | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | CDVAE (Crystal Diffusion VAE) [3], REINVENT [2], GANs [1], Transformers [1] | De novo structure generation with target properties | Superconductor design, lead optimization, molecular generation |

| Validation Databases | JARVIS-DFT [3], ExCAPE-DB [2], ChEMBL [2] | Provides training data and benchmark standards | Superconducting materials, bioactive molecules, target proteins |

| Property Prediction | ALIGNN [3], Pre-trained GNNs, QSAR models | Rapid screening of generated candidates | Materials properties, biological activity, ADMET prediction |

| DFT Calculations | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CASTEP | First-principles validation of stability and properties | Electronic structure, formation energy, superconducting T_c |

| Molecular Representation | SMILES [1], SELFIES [1], Graph Representations | Standardized chemical structure encoding | Compound generation, similarity analysis, feature calculation |

| Analysis Tools | RDKit [2], DataWarrior [2], PCA methods [2] | Chemical space visualization and metric calculation | Diversity analysis, temporal splitting, chemical space mapping |

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that heuristic metrics alone provide insufficient guidance for developing functionally useful materials and compounds. While validity and uniqueness offer convenient computational checkpoints, they correlate poorly with experimental success and can create misleading performance benchmarks. The integration of DFT validation and prospective experimental testing represents the only path toward reliable generative design, bridging the gap between algorithmic performance and practical utility.

Moving forward, the field must adopt more rigorous validation standards that prioritize functional assessment over computational convenience. This includes embracing multi-parameter optimization that reflects real-world constraints, implementing temporal validation splits that better simulate project progression, and acknowledging the fundamental differences between public benchmark performance and proprietary application success. Only by moving beyond heuristic metrics can we fully harness the transformative potential of generative AI for materials and drug discovery.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has established itself as the cornerstone computational method in materials science, providing the fundamental benchmark for predicting material stability and properties. As the field undergoes a transformation through the integration of generative artificial intelligence (AI) and high-throughput computing, DFT's role has evolved from a primary discovery tool to the essential validation mechanism for AI-generated candidates. This paradigm shift allows researchers to navigate the vast chemical space more efficiently by using generative models to propose novel structures, while relying on DFT's quantum mechanical foundations to verify thermodynamic stability and functional properties. The enduring value of DFT lies in its ability to provide quantitatively accurate predictions of formation energies, electronic band structures, and mechanical properties without empirical parameters, making it indispensable for separating viable materials from unstable configurations. Within modern materials informatics pipelines, DFT calculations provide the critical "ground truth" data for training machine learning potentials and for the final validation of generative model outputs, creating a synergistic relationship between accelerated AI-driven exploration and rigorous physical validation.

DFT as a Validation Tool for Generative Materials Design

The Generative AI Revolution and Its Validation Challenge

The emergence of generative models for materials design represents a paradigm shift from traditional discovery approaches. Models such as MatterGen utilize diffusion processes to generate stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table by gradually refining atom types, coordinates, and periodic lattice structures [5]. These AI-driven approaches significantly accelerate the exploration of chemical space, but create a critical validation challenge: determining which generated structures represent physically viable materials. Without rigorous validation, generative models can propose structures that are thermodynamically unstable, mechanically unsound, or otherwise non-synthesizable.

DFT addresses this validation gap by providing quantitative stability metrics through calculation of formation energies and energy above the convex hull. In the case of MatterGen, generated structures undergo DFT relaxation to evaluate their stability, with successful candidates demonstrating energy within 0.1 eV per atom above the convex hull of known materials [5]. This stringent criterion ensures that generative model outputs correspond to realistically synthesizable materials rather than merely computationally possible structures. The integration of DFT validation has enabled MatterGen to more than double the percentage of generated stable, unique, and new (SUN) materials compared to previous generative models while producing structures that are more than ten times closer to their DFT local energy minimum [5].

Synthesizability Prediction Beyond Basic Stability

Recent advances have extended beyond basic thermodynamic stability to predict synthesizability more directly. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework demonstrates how machine learning can leverage DFT-derived data to predict not just stability but actual synthesizability, achieving 98.6% accuracy in classifying synthesizable crystal structures [6]. This approach significantly outperforms traditional synthesizability screening based solely on thermodynamic stability (74.1% accuracy) or kinetic stability from phonon spectra analyses (82.2% accuracy) [6]. By training on a comprehensive dataset of experimentally verified structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) alongside theoretical structures, these models learn the subtle structural and compositional features that distinguish synthesizable materials from those that merely appear stable in computational simulations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Formation Energy (≤0.1 eV/atom above hull) | 74.1% | Strong theoretical foundation, quantitative | Misses metastable synthesizable materials |

| Phonon Stability (lowest frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% | Accounts for kinetic stability | Computationally expensive, still imperfect correlation |

| CSLLM Framework | 98.6% | High accuracy, includes synthesis method prediction | Requires extensive training data, complex model [6] |

Benchmarking DFT Performance Across Material Classes

Accuracy for Structure and Property Prediction

The performance of DFT varies significantly across different material classes and properties, necessitating careful benchmarking for reliable application. For framework materials like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), DFT functionals including PBE-D2, PBE-D3, and vdW-DF2 predict structures with high accuracy, typically reproducing experimental pore diameters within 0.5 Å [7]. However, elastic properties show greater functional dependence, with predicted minimum shear and Young's moduli differing by averages of 3 and 9 GPa, respectively, for rigid MOFs [7]. These variations highlight the importance of functional selection based on the material system and target properties.

For electronic property prediction, particularly band gaps, standard DFT approximations exhibit systematic limitations due to the inherent underestimation of electron-electron interactions [8]. This deficiency has driven the development of advanced correction schemes, including the Hubbard U term for accounting Coulomb interactions in transition metal atoms and hybrid functionals like HSE06 that incorporate exact exchange energy [8]. In studies of transition metal dichalcogenides like MoS₂, these corrections have proven essential for obtaining band gaps that align with experimental measurements, though optimal parameter selection remains material-dependent [8].

Comparative Benchmarking with Many-Body Perturbation Theory

Systematic benchmarking against higher-level theoretical methods provides crucial perspective on DFT's accuracy and limitations. Recent large-scale comparisons between DFT and many-body perturbation theory (specifically GW approximations) reveal that while advanced DFT functionals like HSE06 and mBJ offer reasonable accuracy for band gaps, more sophisticated GW methods can provide superior performance, particularly when including full-frequency integration and vertex corrections [9].

The QSGW^ method, which incorporates vertex corrections into quasiparticle self-consistent GW calculations, achieves exceptional accuracy that can even flag questionable experimental measurements [9]. However, this improved accuracy comes at substantially higher computational cost, making DFT the preferred method for high-throughput screening and large-scale materials discovery initiatives. The practical approach emerging from these benchmarks utilizes DFT for initial screening and exploration, reserving higher-level methods for final validation of promising candidates.

Table 2: Method Performance for Band Gap Prediction (472 Materials Benchmark)

| Method | Mean Absolute Error (eV) | Computational Cost | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard DFT (PBE) | ~1.0 eV (severe underestimation) | Low | Preliminary screening |

| HSE06 Hybrid Functional | ~0.3 eV [9] | Medium-high | High-throughput screening |

| mBJ Meta-GGA | ~0.3 eV [9] | Medium | Solid-state properties |

| G₀W₀-PPA | ~0.3 eV (marginal gain over best DFT) [9] | High | Targeted validation |

| QSGW^ | ~0.1 eV (highest accuracy) [9] | Very High | Final validation |

Experimental Protocols: DFT Validation Workflows

Standard Workflow for Validating Generative Model Outputs

The validation of AI-generated materials through DFT follows a systematic workflow that progresses from initial structural assessment to detailed property calculation:

Structure Relaxation: Generated crystal structures undergo full DFT relaxation of atomic positions, cell shape, and volume to find the nearest local energy minimum. This step identifies structures that correspond to stable configurations rather than high-energy metastable states.

Stability Assessment: Formation energies are calculated relative to standard reference states, with the energy above the convex hull (E({}{\text{hull}})) serving as the primary stability metric. Structures with E({}{\text{hull}}) ≤ 0.1 eV/atom are typically considered potentially synthesizable, while those with negative E({}_{\text{hull}}) are thermodynamically stable [5].

Property Prediction: Electronic structure properties (band gap, density of states), mechanical properties (elastic constants, bulk and shear moduli), and magnetic properties are calculated using appropriate DFT functionals and parameters.

Synthesizability Screening: Advanced workflows incorporate additional analyses including phonon calculations to assess dynamic stability, molecular dynamics simulations to verify thermal stability, and surface energy calculations to evaluate relative phase stability.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this validation pipeline:

Case Study: Validating a Generated Material with Target Properties

A concrete example of this validation process comes from the MatterGen model, which generated a novel material structure targeting specific magnetic properties [5]. The validation protocol included:

Structural Optimization: Using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) with projector augmented-wave pseudopotentials and the PBE functional, with an energy cutoff of 520 eV and k-point spacing of 0.03 Å⁻¹.

Convergence Criteria: Electronic self-consistency threshold of 10⁻6 eV, and ionic relaxation convergence to 0.01 eV/Å force on each atom.

Stability Verification: Calculation of the energy above the convex hull using the Materials Project reference data, confirming E({}_{\text{hull}}) < 0.1 eV/atom.

Property Validation: Calculation of magnetic moments using spin-polarized DFT, with results within 20% of the target property values.

Experimental Synthesis: Successful synthesis and measurement of the generated material confirmed the DFT predictions, demonstrating the real-world validity of the combined generative AI-DFT approach [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for DFT Validation

The effective implementation of DFT validation workflows requires a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources:

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software Packages | Quantum ESPRESSO [8], VASP, CASTEP | Perform core DFT calculations including structure relaxation, electronic structure, and property prediction |

| Phonon Calculation Tools | Phonopy, ABINIT, Quantum ESPRESSO | Evaluate dynamic stability through phonon spectrum calculation, identifying imaginary frequencies |

| Materials Databases | Materials Project [5], ICSD [6], OQMD [6] | Provide reference structures and formation energies for convex hull construction |

| High-Throughput Workflow Managers | mkite, AiiDA, Atomate | Automate complex computational workflows across computing resources |

| Analysis & Visualization | pymatgen, VESTA, Sumo | Process calculation results, extract key properties, and visualize crystal structures |

| Specialized Functionals | HSE06 [8] [9], PBE-D3 [7], mBJ [9] | Address specific limitations like band gap underestimation or van der Waals interactions |

Emerging Integration Frameworks

The growing synergy between generative AI and DFT has spurred the development of integrated frameworks that streamline the validation process. Physics-informed machine learning approaches combine deep learning with physical principles to maintain interpretability while improving prediction accuracy [10]. Multi-modal models incorporate various materials representations including graph-based structures, volumetric data, and symmetry information to enhance prediction reliability [11]. Transfer learning techniques leverage small datasets of high-fidelity DFT calculations to refine machine learning models initially trained on larger but less accurate data [9]. These emerging solutions address the critical challenge of ensuring that AI-generated materials not only appear valid statistically but also conform to fundamental physical principles as verified through DFT.

Despite the rapid advancement of generative AI models for materials discovery, Density Functional Theory maintains its position as the indispensable benchmark for stability and property prediction. The quantitative rigor provided by DFT calculations remains essential for validating generative model outputs, training machine learning potentials, and ultimately bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization. While specialized AI models now achieve remarkable accuracy in predicting synthesizability and specific properties, their development and validation still fundamentally rely on DFT-derived data. The most effective modern materials discovery pipelines leverage the respective strengths of both approaches: generative AI for rapid exploration of chemical space, and DFT for rigorous physical validation. As generative models continue to evolve, DFT's role as the quantitative anchor ensuring physical validity becomes increasingly crucial, maintaining its status as the gold standard for computational materials validation.

The advent of generative models has revolutionized the field of inverse materials design, enabling the direct creation of novel crystal structures tailored to specific property constraints. However, the true measure of these models' success lies not just in their generative capacity, but in the * stability, *uniqueness, and novelty of their outputs—collectively known as the SUN criteria. This framework provides a rigorous methodology for validating whether computationally discovered materials are both physically plausible and genuinely innovative. Within the broader thesis of validating generative models with Density Functional Theory (DFT), SUN metrics serve as the essential bridge between raw computational output and scientifically valuable discoveries, offering a standardized approach for researchers to benchmark performance across different algorithms and research groups.

Performance Comparison of Generative Models

The evaluation of generative models for materials discovery relies on standardized metrics that quantify their ability to propose viable candidates. The SUN criteria provide this foundation, with Stable materials exhibiting energy above hull (Ehull) below 0.1 eV/atom, Unique structures avoiding duplicates within the generated set, and Novel materials absent from established crystal databases [12]. Performance benchmarks across state-of-the-art models reveal significant differences in their generative capabilities.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Generative Models for Materials Design

| Model | SUN Rate (%) | Average RMSD from DFT Relaxed (Å) | Property Optimization Approach | Training Data Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatterGen | 75.0% | <0.076 | Adapter modules with classifier-free guidance | 607,683 structures (Alex-MP-20) |

| MatInvent | Not explicitly stated | Not explicitly stated | Reinforcement learning with reward-weighted KL regularization | Pre-trained on large-scale unlabeled data |

| CDVAE | Lower than MatterGen | ~0.8 (approx. 10x higher than MatterGen) | Limited property optimization | MP-20 dataset |

| DiffCSP | Lower than MatterGen | Higher than MatterGen | Limited property optimization | MP-20 dataset |

Table 2: Single-Property Optimization Performance of MatInvent

| Target Property | Property Type | Convergence Iterations | Property Evaluations | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band gap (3.0 eV) | Electronic | <60 | ~1,000 | DFT calculations |

| Magnetic density (>0.2 Å⁻³) | Magnetic | <60 | ~1,000 | DFT calculations |

| Specific heat capacity (>1.5 J/g/K) | Thermal | <60 | ~1,000 | MLIP simulations |

| Minimal co-incident area (<80 Ų) | Synthesizability | <60 | ~1,000 | MLIP simulations |

| Bulk modulus (300 GPa) | Mechanical | <60 | ~1,000 | ML prediction |

| Total dielectric constant (>80) | Electronic | <60 | ~1,000 | ML prediction |

MatterGen demonstrates superior performance in generating stable materials, with 75% of its outputs falling below the 0.1 eV/atom energy above hull threshold when evaluated against the combined Alex-MP-ICSD reference dataset [12]. Furthermore, its structural precision is notable, with 95% of generated structures exhibiting an RMSD below 0.076 Å from their DFT-relaxed configurations— nearly an order of magnitude smaller than the atomic radius of hydrogen [12]. The model also maintains impressive diversity, retaining 52% uniqueness even after generating 10 million structures, with 61% qualifying as novel relative to established databases [12].

MatInvent employs a different approach through reinforcement learning (RL), demonstrating rapid convergence to target property values across electronic, magnetic, mechanical, thermal, and physicochemical characteristics [13]. This RL workflow achieves robust optimization typically within 60 iterations (approximately 1,000 property evaluations), substantially reducing the computational burden compared to conditional generation methods [13]. Its compatibility with diverse diffusion model architectures and property constraints makes it particularly adaptable for multi-objective optimization tasks, such as designing magnets with low supply-chain risk or high-κ dielectrics [13].

Experimental Protocols for SUN Validation

DFT Validation Methodology

The validation of generative model outputs requires a rigorous, multi-stage computational workflow to assess stability, uniqueness, and novelty:

- Initial Structure Generation: Models generate candidate crystal structures defined by their unit cell parameters, including atom types (chemical elements), fractional coordinates, and periodic lattice matrices [12].

- Geometry Optimization: Generated structures undergo relaxation using universal machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) to approximate local energy minima before expensive DFT calculations [13].

- DFT Single-Point Energy Calculation: Optimized structures are evaluated using DFT to compute precise total energies, electronic structures, and other target properties [12].

- Stability Assessment (Ehull Calculation):

- Formation energy is calculated relative to elemental phases.

- Energy above hull (Ehull) is determined from the convex hull of known stable phases in the chemical space.

- Materials with Ehull < 0.1 eV/atom are considered "stable" and likely synthesizable [12].

- Uniqueness and Novelty Checking:

- Uniqueness: Determined by comparing generated structures against each other using structure matching algorithms to eliminate duplicates [12].

- Novelty: Assessed by comparing against established materials databases (e.g., Materials Project, Alexandria, ICSD) using ordered-disordered structure matchers [12].

Reinforcement Learning Workflow for Inverse Design

MatInvent implements an RL framework that reframes the denoising process of diffusion models as a multi-step Markov decision process [13]. The experimental protocol includes:

- Prior Model Initialization: Start with a diffusion model pre-trained on large-scale unlabeled crystal structure data [13].

- Batch Generation: The model randomly generates a batch of crystal structures each RL iteration [13].

- SUN Filtering: Apply geometry optimization and SUN filtering, retaining only structures that are Stable, Unique, and Novel [13].

- Property Evaluation & Reward Assignment: Calculate material properties via DFT, ML simulations, or empirical calculations, then assign rewards based on target objectives [13].

- Model Fine-tuning: Use top-performing samples to fine-tune the diffusion model via policy optimization with reward-weighted Kullback-Leibler regularization to prevent overfitting [13].

- Experience Replay & Diversity Filtering: Incorporate high-reward crystals from past iterations and apply linear penalties to non-unique structures to enhance sample efficiency and diversity [13].

MatInvent employs a reinforcement learning workflow that iteratively optimizes a pre-trained diffusion model toward target properties while maintaining structural stability, uniqueness, and novelty.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for SUN Validation

The experimental validation of SUN materials requires specialized computational tools and resources that function as "research reagents" in a virtual laboratory environment.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SUN Materials Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to SUN Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP/Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT Code | Electronic structure calculations | Determines formation energies, electronic properties, and energy above hull for stability assessment |

| MLIPs (M3GNet, CHGNet) | Machine Learning Force Fields | Accelerated structure relaxation | Pre-optimizes generated structures before DFT calculations, reducing computational cost |

| Pymatgen | Python Library | Materials analysis | Structure manipulation, analysis, and integration with materials databases |

| Materials Project/Alexandria | Database | Crystalline materials data | Reference datasets for novelty checking and convex hull construction |

| Structure Matcher | Algorithm | Crystal structure comparison | Quantifies uniqueness and novelty by detecting duplicate structures |

The SUN criteria provide an essential framework for quantitatively evaluating the performance of generative models in materials science. Through rigorous DFT validation and standardized metrics, researchers can objectively compare different algorithmic approaches and assess their true potential for materials discovery. Current state-of-the-art models like MatterGen and MatInvent demonstrate significant advances in generating stable, diverse materials with targeted properties, with MatterGen excelling in structural stability and precision, while MatInvent offers efficient property optimization through reinforcement learning. As the field progresses, the SUN framework will continue to serve as a critical validation methodology, ensuring that computationally discovered materials are not only novel but also physically plausible and synthetically accessible—ultimately accelerating the translation of generative design into real-world materials solutions.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Core Challenges in Validating Generative Materials

- Systematic Validation Protocols

- Comparative Performance of Generative and Validation Models

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

- Integrated Workflows for Robust Material Discovery

The discovery of new materials, particularly those with ultrahigh functional properties like thermal conductivity, is crucial for advancing technology in thermal management and energy conversion [14]. Traditional methods, such as trial-and-error experiments and direct ab initio random structure searching (AIRSS), are limited by high computational costs and slow throughput [14]. Generative deep learning models have emerged as a powerful solution, enabling the rapid exploration of a vast chemical space by learning the joint probability distribution of known materials and sampling new structures from it [14]. However, a significant gap persists between the theoretical design of new materials by these algorithms and their reliable real-world application. A primary source of this gap is the over-reliance on Density Functional Theory (DFT) for both training data and validation, which introduces known inaccuracies and inconsistencies [15]. This guide objectively compares current approaches and provides a framework for rigorously validating generative model outputs against higher-fidelity standards to bridge this gap.

Core Challenges in Validating Generative Materials

Navigating the path from a computationally generated material to a validated, viable candidate requires overcoming several key pitfalls.

The DFT Bottleneck in Training and Validation: Many generative models and the machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) used to validate them are trained exclusively on DFT-generated data [15]. DFT, while computationally tractable, is itself an approximation. Its results can vary significantly based on the chosen functional (e.g., PBE or B3LYP), leading to variances in simulation results and making MLIPs trained solely on this data less reliable for real-world prediction [15]. This creates a circular dependency where models are never validated against a higher standard.

Ensuring Thermodynamic Stability: Generative models like the Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoder (CDVAE) can incorporate physical inductive biases to encourage stability, but this remains an approximation [14]. They cannot guarantee that all generated materials will be thermodynamically stable in a broader chemical space. Without rigorous stability checks using optimized structures, the generated candidates may be physically unrealizable [14].

The Confabulation of Generative AI: All AI models, including large language models (LLMs) used for data extraction and generative models for materials, can "confabulate"—generate fabricated information that seems logically sound but has no basis in the input data [16]. In materials science, this could manifest as predicting a material with favorable properties that does not correspond to a local energy minimum.

Inadequate Evaluation Metrics: Current benchmarks for Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) often fail to evaluate their performance in large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that model experimentally measurable properties [15]. A model might perform well on energy regression tasks but fail to reliably simulate properties like lattice thermal conductivity over time and under varying conditions.

Systematic Validation Protocols

To address these pitfalls, researchers must adopt comprehensive validation protocols. The following experiments are critical for assessing the real-world applicability of generatively designed materials.

Experiment 1: Latent Space Interpolation Stability Check

- Objective: To evaluate the thermodynamic stability of materials generated by interpolating between two known stable structures in the model's latent space. This tests the model's ability to produce viable intermediates, not just reconstruct training data.

- Methodology:

- Select two known stable crystal structures from the validation set (e.g., diamond and graphite for carbon).

- Encode them into the latent space ( Z ) of a generative model (e.g., CDVAE).

- Linearly interpolate between these two points to generate ( N ) new latent vectors.

- Decode these vectors to produce ( N ) new candidate structures.

- Relax all generated structures using a high-fidelity MLIP or, ideally, a quantum-mechanical method like CCSD(T) for small systems.

- Calculate the energy above the hull (( E{\text{hull}} )) for each relaxed structure. A positive ( E{\text{hull}} ) indicates instability.

- Metrics: Percentage of generated materials with ( E_{\text{hull}} < 0.1 \ \text{eV/atom} ), which are considered potentially stable.

Experiment 2: MLIP Fidelity under Active Learning

- Objective: To quantify the improvement in lattice thermal conductivity (( \kappa_L )) prediction when MLIPs are refined using active learning, moving beyond static DFT-trained models.

- Methodology:

- Start with an MLIP pre-trained on a broad DFT dataset (e.g., the Materials Project).

- Generate a set of candidate materials using a generative model.

- Use a protocol like Query by Committee (QBC) to select structures for which the MLIP committee shows high predictive uncertainty [14].

- Run high-fidelity (e.g., CCSD(T)) calculations on these selected structures and add them to the training data.

- Fine-tune the MLIP on this expanded, targeted dataset.

- Use the refined MLIP to perform molecular dynamics simulations and predict ( \kappa_L ) for the full set of candidates.

- Metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in ( \kappa_L ) predictions compared to experimental values or high-fidelity simulation results; the reduction in model uncertainty on the final candidate set.

Experiment 3: Generative Model Robustness to Data Scarcity

- Objective: To test a generative model's ability to produce valid and diverse structures when trained on a limited subset of available data, simulating real-world scenarios for novel material classes.

- Methodology:

- Take a large dataset of known structures (e.g., the 101,529 carbon allotropes generated by AIRSS [14]).

- Train the generative model on a small, random fraction (e.g., 10%) of the dataset.

- Generate a large number of new structures (e.g., 100,000).

- Evaluate the validity (e.g., correct stoichiometry, realistic bond lengths), diversity (via structural similarity metrics), and novelty (structures not in the full original dataset) of the outputs.

- Metrics: Validity rate, diversity index (based on structural fingerprint analysis), and novelty rate.

Comparative Performance of Generative and Validation Models

The following tables summarize quantitative data from studies that highlight the performance and limitations of different components in the generative materials discovery pipeline.

Table 1: Performance of AI Tools in Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews. This demonstrates a common challenge—confabulation—that can also affect AI in materials science.

| AI Tool | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Confabulation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elicit | 92% | 92% | 92% | ~4% |

| ChatGPT | 91% | 89% | 90% | ~3% |

Source: Comparison of Elicit and ChatGPT against human-extracted data as a gold standard [16].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Quantum-Accurate Simulation Methods for MLIP Training.

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Computational Scaling | Considered Accuracy | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electron Density Approximation | ( \mathcal{O}(N^3 - N^5) ) | High (Approximate) | Variances based on functional choice; known systematic inaccuracies [15] |

| Coupled Cluster Theory (CCSD(T)) | Wavefunction Theory | ( \mathcal{O}(N^7) ) | Gold Standard | Prohibitively high cost for large systems [15] |

Source: Analysis of methods for creating high-accuracy MLIP training data [15].

Table 3: Data Augmentation Performance for Insufficient Clinical Trial Accrual. This demonstrates the potential of generative models to compensate for missing data in scientific contexts.

| Generative Model | Max. Patient Removal Tolerated | Decision Agreement with Full Trial | Estimate Agreement with Full Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Synthesis | Up to 40% | 88% to 100% | 100% |

| Sampling with Replacement | Not Specified | 78% to 89% | Lower than Sequential Synthesis |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | Lower than Sequential Synthesis | Lower than Sequential Synthesis | Lower than Sequential Synthesis |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Lower than Sequential Synthesis | Lower than Sequential Synthesis | Lower than Sequential Synthesis |

Source: Evaluation of generative models to simulate patients for underpowered clinical trials [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in the process of generating and validating new materials.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Generative Materials Validation.

| Item Name | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Generative Model (e.g., CDVAE) | Learns the joint probability distribution of existing materials and samples new candidate structures from this distribution, enabling rapid exploration of chemical space [14]. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) | A fast, surrogate model that approximates quantum-mechanical potential energy surfaces, allowing for the efficient relaxation and simulation of generated structures without constant DFT calculations [14] [15]. |

| Active Learning Protocol (e.g., QBC) | A strategy to selectively run high-fidelity calculations on data points where the model is most uncertain, maximizing the information gain from expensive computations and improving model fidelity [14]. |

| High-Fidelity Reference Method (e.g., CCSD(T)) | Considered the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry, it provides highly accurate training and validation data to correct and refine MLIPs, mitigating the DFT bottleneck [15]. |

| Structural Similarity Metric | Quantifies the diversity of generated structures and helps identify and remove duplicates, ensuring a broad exploration of the structural space [14]. |

| Stability Metric (Energy Above Hull) | Calculates the energy difference between a material and the most stable combination of other phases at the same composition; a primary measure of thermodynamic stability [14]. |

Integrated Workflows for Robust Material Discovery

The following diagrams, created using the specified color palette, illustrate a proposed robust workflow that integrates generative design with high-fidelity validation to bridge the gap between algorithmic design and real-world application.

High-Fidelity Material Discovery Workflow

Active Learning Protocol for MLIP Refinement

Generative Architectures and Conditional Design for Targeted Material Properties

The discovery and design of novel materials and drug compounds represent a monumental challenge in scientific research. Traditional computational methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), provide accurate energy evaluations but at a prohibitive computational cost, especially for screening millions of potential candidates [18]. Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) has emerged as a powerful paradigm to accelerate this exploration by learning underlying patterns from existing data to propose new, valid candidates with high probability. This guide objectively compares four leading generative model families—Diffusion Models, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Generative Flow Networks (GFlowNets)—within the critical context of scientific discovery, where generated candidates must ultimately be validated through high-fidelity methods like DFT.

Model Paradigms at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core principles, strengths, and weaknesses of each generative model paradigm.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Leading Generative Model Paradigms

| Model Paradigm | Core Principle | Key Strengths | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Probabilistic encoder-decoder framework that learns a latent distribution of the data [19]. | Stable training; enables efficient representation learning and interpolation in latent space [20] [19]. | Often produces blurry or fuzzy outputs; can suffer from "posterior collapse" [20] [21]. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Two neural networks, a generator and a discriminator, are trained in an adversarial game [20]. | Capable of producing outputs with high perceptual quality and sharpness [20] [21]. | Training can be unstable and suffer from mode collapse [20] [21]. |

| Diffusion Models | Iteratively denoise a random variable, reversing a forward noising process, to generate data [21]. | High-quality, diverse outputs with strong semantic coherence; training stability [22] [21]. | Computationally intensive and slow inference due to many iterative steps [22] [21]. |

| Generative Flow Networks (GFlowNets) | Learns a stochastic policy to generate compositional objects through a sequence of actions, with probability proportional to a given reward [23]. | Efficiently explores high-dimensional combinatorial spaces; generates diverse candidates [23]. | Primarily demonstrated in static environments; adaptation to dynamic conditions requires meta-learning [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Validating the effectiveness of generative models in scientific domains requires robust, domain-specific protocols. The core workflow involves generating candidates with the model and then verifying their quality and physical plausibility, often using DFT as a ground truth.

Key Experimental Components

- Training Data Curation: Models are trained on large, structured datasets. For materials, this might be crystal structure databases (e.g., the Materials Project) [24]. For drug discovery, molecular databases like ChEMBL are standard [25] [19].

- Model-Specific Training:

- VAEs/GANs/Diffusion: Trained to reconstruct or generate data that matches the distribution of the training set. Their outputs are then scored by a separate property predictor [25] [21].

- GFlowNets: Trained with a reward function, which can be the output of a predictive model (e.g., a QSAR model for bioactivity or a formation energy predictor for materials). The policy is optimized to sample high-reward candidates with probability proportional to the reward [23].

- Candidate Generation and Pre-screening: Thousands of candidates are sampled from the trained model. Before costly DFT validation, they are typically pre-screened using fast machine learning potentials (like ANI-1x or ANI-1ccx) [18] or other predictive models to filter out invalid or low-probability candidates.

- High-Fidelity DFT Validation: The shortlist of promising candidates is validated using DFT calculations. This step assesses the generated material's or molecule's stability, electronic properties, and other quantum mechanical attributes, providing a ground-truth evaluation of the model's design capabilities [18].

Comparative Performance and Experimental Data

Empirical evidence from various scientific domains highlights the trade-offs between these model paradigms.

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Performance Across Domains

| Domain | Model | Performance Highlights | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Science (SST Map Generation) [26] | GAN | Generated emulations most consistent with observed data. | Statistical consistency with observations |

| VAE | Performance was generally lower than GAN and Diffusion. | Statistical consistency with observations | |

| Diffusion | Matched GAN performance in some specific cases. | Statistical consistency with observations | |

| Scientific Imaging [21] | GAN (StyleGAN) | Produced images with high perceptual quality and structural coherence. | Expert-driven qualitative assessment |

| Diffusion (DALL-E 2) | Delivered high realism and semantic alignment but sometimes struggled with scientific accuracy. | Expert-driven qualitative assessment | |

| Drug Discovery (Molecular Generation) [25] | RNN + RL | Overcame sparse reward problem; discovered novel EGFR inhibitors validated by experimental bioassay. | Experimental bioactivity validation |

| Materials Science (Potential Energy) [18] | NN Potentials (ANI-1ccx) | Outperformed DFT on reaction thermochemistry test cases and was more accurate than the gold-standard OPLS3 force field. | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) vs. high-level quantum methods |

Analysis of Key Results

- Generative vs. Discriminative Learning in Drug Discovery: A study on designing EGFR inhibitors demonstrated that a naïve generative model failed due to sparse rewards from a QSAR predictor [25]. Success was achieved by augmenting reinforcement learning (RL) with transfer learning, experience replay, and reward shaping, enabling the model to rediscover known active scaffolds and generate novel compounds that were experimentally validated [25]. This underscores that the training strategy can be as critical as the model architecture itself.

- Bridging the Accuracy-Speed Gap with ML Potentials: The ANI (Accurate Neural Network) potential exemplifies a hybrid approach. ANI-1x, a neural network potential trained on DFT data, provides accuracy better than MP2 quantum mechanics and the OPLS3 force field at a fraction of the computational cost of advanced quantum methods [18]. Furthermore, ANI-1ccx used transfer learning on a small, highly accurate CCSD(T)/CBS dataset to achieve "chemical accuracy," outperforming DFT on reaction energies [18]. These models act as highly efficient surrogates for DFT in the pre-screening stage of the generative pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following reagents, datasets, and software are essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Database | A large, open-access database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for training generative models in drug discovery. | [25] |

| ANI-1x / ANI-1ccx | ML Potential | High-accuracy, transfer-learned neural network potentials used for fast energy and force evaluation of organic molecules, serving as a proxy for DFT. | [18] |

| QP (Quantum Pressure) | Benchmark | A standard benchmark collection (e.g., GuacaMol) used to evaluate the performance of generative models on objectives like drug-likeness (QED). | [25] [18] |

| GFlowNet Library | Software | Publicly available codebase for training and benchmarking GFlowNets and diffusion samplers, providing a unified framework for comparative studies. | [22] |

| Crystal Structure Databases | Database | Databases (e.g., from the Materials Project) containing known crystal structures used for training generative models for materials design. | [24] |

The choice of a generative model paradigm is highly context-dependent. GANs can produce high-quality, sharp outputs but require careful handling of their training dynamics. VAEs offer stable training and a continuous latent space but may lack the output fidelity needed for some applications. Diffusion Models currently set the benchmark for sample quality and diversity but at a high computational cost. GFlowNets present a uniquely promising approach for diverse sample generation in structured, combinatorial spaces, particularly when guided by an explicit reward function.

For the critical task of validating generative model materials with DFT, the most effective strategy is often a hybrid one. Generative models are best used as powerful exploration engines to propose candidates, which are then efficiently pre-screened by accurate machine learning potentials (like the ANI family) before final validation with high-fidelity DFT. This pipeline combines the creative power of generative AI with the rigorous physical accuracy of quantum mechanics, accelerating the design cycle for novel drugs and materials.

The discovery of new inorganic materials is a cornerstone for technological progress in fields ranging from energy storage to catalysis. However, traditional methods for materials discovery, such as experimental trial-and-error or computational screening of known databases, are often slow and fundamentally limited to exploring a narrow fraction of the vast chemical space. Generative AI models present a paradigm shift by directly proposing novel, stable crystal structures from scratch. Among these, MatterGen, a diffusion model developed by Microsoft Research, represents a significant advancement by specifically targeting the generation of stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table [27] [28]. This case study objectively compares MatterGen's performance against other contemporary generative models, situating its capabilities within the critical context of validation through Density Functional Theory (DFT), the gold-standard computational method for assessing material stability and properties.

Performance Comparison Against Alternative Models

Evaluating generative models for materials requires robust metrics that assess the practicality and novelty of their outputs. Key benchmarks include the proportion of generated materials that are Stable, Unique, and Novel (S.U.N.), and the Root Mean Square Distance (RMSD) between the generated structure and its relaxed configuration after DFT optimization, which indicates how close the generated structure is to a local energy minimum [28].

The following table summarizes MatterGen's performance against other leading generative models, as evaluated in the foundational Nature publication [28].

Table 1: Comparative performance of MatterGen and other generative models for inorganic crystals. S.U.N. metrics and RMSD are evaluated on 1,000 generated samples per method.

| Generative Model | % S.U.N. (Stable, Unique, Novel) | Average RMSD to DFT Relaxed Structure (Å) | Key Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatterGen | 38.57% [29] [28] | 0.021 [29] [28] | Diffusion Model (3D geometry) |

| MatterGen (trained on MP-20 only) | 22.27% [29] | 0.110 [29] | Diffusion Model (3D geometry) |

| DiffCSP (on Alex-MP-20) | 33.27% [29] | 0.104 [29] | Diffusion Model |

| DiffCSP (on MP-20) | 12.71% [29] | 0.232 [29] | Diffusion Model |

| CDVAE | 13.99% [29] | 0.359 [29] | Variational Autoencoder |

| G-SchNet | 0.98% [29] | 1.347 [29] | Generative Neural Network |

| P-G-SchNet | 1.29% [29] | 1.360 [29] | Generative Neural Network |

| FTCP | 0.0% [29] | 1.492 [29] | Fourier Transforms |

As the data demonstrates, MatterGen generates a significantly higher fraction of viable (S.U.N.) materials compared to other methods. Furthermore, its exceptionally low RMSD indicates that the structures it generates are very close to their local energy minimum, reducing the computational cost of subsequent DFT relaxation and increasing the likelihood of synthetic viability [28].

Another emerging approach is CrystaLLM, which treats crystal structure generation as a text-generation problem by autoregressively modeling the Crystallographic Information File (CIF) format [30]. While a direct, quantitative comparison to MatterGen's metrics is not provided in the search results, CrystaLLM is reported to produce "plausible crystal structures for a wide range of inorganic compounds" [30]. This highlights a fundamentally different methodology from MatterGen's 3D-diffusion approach.

Beyond one-off generation, recent work like MatInvent introduces a reinforcement learning (RL) framework built on top of pre-trained diffusion models like MatterGen. MatInvent optimizes the generation process for specific target properties, dramatically reducing the number of property evaluations required—by up to 378-fold compared to previous methods [13]. This represents a powerful complementary approach that enhances the capabilities of base generative models.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

The superior performance of MatterGen is not self-evident but is substantiated through rigorous experimental protocols centered on DFT validation. The following workflow details the standard procedure for evaluating models like MatterGen.

Diagram 1: Standard workflow for validating generative models with DFT.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The validation of MatterGen, as described in its primary Nature publication, involves several critical stages [28]:

Structure Generation and Uniqueness Filtering: The model generates a batch of candidate crystal structures (e.g., 1,000 or 10,000). These are first processed to remove duplicates using a structure matcher. MatterGen employs a novel ordered-disordered structure matcher that accounts for compositional disorder, where different atoms can randomly occupy the same crystallographic site. This provides a more chemically meaningful definition of novelty and uniqueness [27] [28].

DFT Relaxation: The unique generated structures are then relaxed to their nearest local energy minimum using Density Functional Theory (DFT). This step is computationally expensive but essential, as it adjusts atom positions and lattice parameters to find a stable configuration. The small RMSD of MatterGen's outputs means this relaxation requires minimal adjustment, saving substantial computational resources [28].

Stability Assessment: The stability of the DFT-relaxed structure is determined by calculating its energy above the convex hull (Eₕᵤₗₗ). This metric compares the energy of the generated material to the most stable combination of other elements or compounds in its chemical system. A material is typically considered "stable" if its Eₕᵤₗₗ is below 0.1 eV/atom. In MatterGen's evaluation, a reference dataset called Alex-MP-ICSD—containing over 850,000 computed and experimental structures from the Materials Project, Alexandria, and the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)—was used to construct a robust convex hull for this assessment [28].

Novelty Verification: Finally, a structure is deemed "novel" if it does not match any structure in the expansive Alex-MP-ICSD reference dataset, again using the disordered-aware structure matcher [28]. Remarkably, MatterGen has been shown to rediscover thousands of experimentally verified structures from the ICSD that were not in its training set, strongly indicating its ability to propose synthesizable materials [28].

Property-Guided Generation and Experimental Synthesis

A key advancement of MatterGen is its move beyond unconditional generation to inverse design—creating materials that meet specific user-defined constraints. This is achieved through a fine-tuning process using adapter modules.

Diagram 2: Workflow for property-conditioned generation and experimental validation.

Fine-Tuning for Target Properties

The base MatterGen model is first pre-trained on a large, diverse dataset of stable materials (Alex-MP-20, ~608,000 structures) [28] [31]. For inverse design, the model is fine-tuned on smaller, labeled datasets. Adapter modules—lightweight, tunable components injected into the base model—are trained to alter the generation process based on a property label, such as a target bulk modulus or magnetic density [28]. This approach, combined with classifier-free guidance, allows the fine-tuned model to generate materials steered toward specific property constraints. MatterGen has demonstrated success in generating materials with desired [27] [28]:

- Chemical systems (e.g., "Li-O").

- Crystal symmetry (target space group).

- Mechanical properties (e.g., high bulk modulus).

- Electronic properties (e.g., band gap).

- Magnetic properties (e.g., high magnetic density).

Experimental Synthesis as Ultimate Validation

Computational metrics are necessary but insufficient; experimental synthesis provides the ultimate validation. In a compelling proof-of-concept, a structure generated by MatterGen—conditioned on a target bulk modulus of 200 GPa—was synthesized in collaboration with the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology (SIAT) [27]. The synthesized material, TaCr₂O₆, confirmed the predicted crystal structure, with the caveat of some compositional disorder between Ta and Cr atoms. Experimentally, the measured bulk modulus was 169 GPa, which is within 20% of the design target [27]. This successful translation from a computational design to a real material with a predicted property underscores the practical potential of MatterGen in accelerating materials innovation.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and application of tools like MatterGen rely on a "scientist's toolkit" composed of datasets, software, and computational resources. The following table details key components in the MatterGen ecosystem.

Table 2: Key resources and "research reagents" for generative materials design with MatterGen.

| Resource Name | Type | Function in the Workflow | License & Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alex-MP-20 / MP-20 | Training Dataset | Curated datasets of stable inorganic crystal structures used to pre-train the MatterGen base model [28] [31]. | Creative Commons Attribution [31] |

| MatterSim | Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF) | Used for fast, preliminary relaxation of generated structures before more expensive DFT evaluation [29]. | Available with MatterGen |

| DFT Software (e.g., VASP) | Simulation Software | Used for the final, high-fidelity relaxation and property calculation of generated structures to validate stability and properties [28]. | Commercial / Academic Licenses |

| MatInvent | Reinforcement Learning Framework | An RL workflow that can optimize MatterGen for goal-directed generation, drastically reducing the number of property evaluations needed [13]. | N/A |

| PyMatGen | Python Library | Provides tools for analyzing crystal structures, including calculating supply-chain risk via the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) score [13]. | Open Source |

Within the critical framework of DFT validation, MatterGen establishes a new state-of-the-art for generative models in materials science. Its specialized diffusion process for crystalline materials enables it to outperform previous approaches significantly in terms of the stability, novelty, and structural quality (low RMSD) of its generated materials. Its unique capacity to be fine-tuned for a wide array of property constraints moves the field from mere generation towards true inverse design. The experimental synthesis of a MatterGen-proposed material, TaCr₂O₆, with a property close to its design target, provides a crucial proof-of-principle for the entire paradigm. As the field evolves, with new approaches like CrystaLLM offering alternative paradigms and frameworks like MatInvent enhancing efficiency, MatterGen's robust and versatile architecture positions it as a foundational tool for the accelerated discovery of next-generation functional materials.

The rational design of molecules and materials with targeted properties represents a long-standing challenge in chemistry, materials science, and drug development. Traditional materials discovery follows a forward design approach, which involves synthesizing and testing numerous candidates through trial and error—a process that is often slow, expensive, and resource-intensive. Inverse design fundamentally reverses this workflow by starting with desired properties and computationally identifying candidate structures that exhibit these target characteristics [32]. This paradigm shift has gained tremendous momentum with advances in machine learning (ML), particularly generative models that can navigate the vast chemical space to propose novel molecular structures with predefined functionalities.

Within this context, a critical research focus has emerged on developing conditional generative models—architectures that can incorporate specific constraints during the generation process. By conditioning on chemical composition, symmetry properties, and electronic structure characteristics, these models enable targeted exploration of chemical space regions with enhanced precision. The validation of generated candidates against Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provides the essential theoretical foundation for assessing quantum mechanical accuracy before experimental synthesis. This comparison guide examines the current landscape of inverse design methodologies, with particular emphasis on their conditioning strategies and performance in generating chemically valid, property-specific materials for research and development applications.

Comparative Analysis of Inverse Design Methods

The following analysis compares prominent inverse design approaches based on their conditioning strategies, architectural implementations, and performance metrics as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Inverse Design Methods and Conditioning Approaches

| Method | Conditioning Strategy | Molecular Representation | Key Properties Targeted | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cG-SchNet [33] | Conditional distributions based on embedded property vectors | 3D atomic coordinates and types | HOMO-LUMO gap, energy, polarizability, composition | >90% validity; property control beyond training regime |

| G-SchNet [33] | Fine-tuning on biased datasets or reinforcement learning | 3D atomic coordinates and types | HOMO-LUMO gap, drug candidate scaffolds | Requires sufficient target examples; limited generalization |

| Classification-Based Inverse Design [34] | Targeted electronic properties as input for classification | Atomic composition (atom counts) | Multiple electronic properties | >90% prediction accuracy for atomic composition |

| Discriminative Forward Design [34] | Property prediction from structural features | Various feature representations | Electronic properties | N/A (forward paradigm) |

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Specific Design Tasks

| Method | Design Task | Conditioning Parameters | Success Metrics | DFT Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cG-SchNet [33] | Molecules with specified HOMO-LUMO gap and energy | Joint electronic property targets | Novel molecules with optimized properties | Demonstrated agreement with reference calculations |

| cG-SchNet [33] | Structures with predefined motifs | Molecular fingerprints | Accurate motif incorporation in novel scaffolds | Stability confirmation via DFT energy calculations |

| 3D-Scaffold Framework [33] | Drug candidates around functional groups | Structural constraints around scaffolds | Diverse candidate generation | Limited to regions with sufficient training data |

| Bayesian Optimization [32] | Small dataset scenarios | Sequential design with minimal data | Efficient convergence to optima | Dependent on accuracy of property predictions |

Conditioning Strategies: Technical Implementation

Chemical Composition Conditioning

Conditioning on chemical composition involves specifying the atomic constituents of target molecules, typically represented as atom type counts or stoichiometric ratios. In practice, this is implemented through learnable atom type embeddings that are weighted by occurrence [33]. The model learns the relationship between elemental composition and emergent physical properties, enabling it to sample candidates with desired compositions while optimizing for other targeted characteristics. For instance, models can learn to prefer smaller structures when targeting small polarizabilities without explicit size constraints [33]. This approach is particularly valuable for designing materials with specific elemental requirements, such as avoiding scarce or toxic elements while maintaining performance characteristics.

Symmetry and Structural Conditioning

Symmetry considerations play a crucial role in materials properties, particularly for crystalline systems and molecular assemblies. Inversion symmetry, a fundamental symmetry operation where all coordinates are inverted (r → -r), directly impacts electronic wavefunctions and spectral properties [35]. The inversion symmetry quantum number determines whether wavefunctions are even (gerade) or odd (ungerade) under inversion, with important implications for spectroscopic selection rules. Conditional generative models can incorporate symmetry constraints through several mechanisms: using symmetry-aware representations that encode point group symmetries, applying symmetry losses during training that penalize asymmetric structures, or employing equivariant architectures that inherently preserve symmetry operations throughout the generation process.

Electronic Property Conditioning

Electronic properties represent some of the most valuable targets for inverse design, particularly for applications in electronics, catalysis, and energy storage. The conditional G-SchNet (cG-SchNet) architecture demonstrates how multiple electronic properties can be jointly targeted through property embedding networks [33]. Scalar-valued properties like HOMO-LUMO gap, total energy, and isotropic polarizability are typically expanded on a Gaussian basis before embedding, while vector-valued properties like molecular fingerprints are processed directly by the network. This approach enables the model to learn complex relationships between 3D molecular structures and their electronic characteristics, allowing for the generation of molecules with specifically tuned electronic properties even in regions of chemical space where reference calculations are sparse [33].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Model Training and Implementation

The training of conditional generative models for inverse design follows carefully designed protocols to ensure robust performance. For cG-SchNet, models are trained on datasets of molecular structures with known property values, learning the conditional distribution of structures given target properties [33]. The training objective maximizes the likelihood of the observed molecules under the conditional distribution, with the model learning to predict the next atom type and position based on previously placed atoms and the target conditions. The architecture employs two auxiliary tokens—origin and focus tokens—to stabilize generation: the origin token marks the molecular center of mass and enables inside-to-outside growth, while the focus token localizes position predictions to avoid symmetry artifacts and ensure scalability [33].

DFT Validation Protocols

Validating generated molecular structures with Density Functional Theory represents a critical step in assessing inverse design performance. Standard validation protocols involve:

- Geometry Optimization: Generated structures are first optimized using DFT methods to relieve any unphysical strains or bond lengths.

- Single-Point Energy Calculations: The optimized structures undergo single-point energy calculations to determine electronic properties.

- Property Comparison: Target properties (HOMO-LUMO gap, polarizability, formation energy) are computed and compared against the conditioning values.

- Stability Assessment: Molecular dynamics simulations or vibrational frequency analyses verify thermodynamic stability.

The choice of DFT functional significantly impacts validation outcomes. Commonly used functionals include PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) and B3LYP (Becke, 3-parameter, Lee-Yang-Parr), though these approximations have known inaccuracies for certain systems [15]. For higher accuracy, coupled cluster theory [CCSD(T)] serves as a gold standard, though its computational expense limits application to smaller molecules [15].

Performance Evaluation Metrics

The performance of inverse design methods is quantified using multiple metrics:

- Validity Rate: Percentage of generated structures that correspond to chemically plausible molecules with proper bonding, coordination, and stability.

- Property Accuracy: Deviation between target properties and DFT-computed values for generated structures.

- Novelty: The chemical diversity and structural uniqueness of generated molecules compared to training data.

- Success Rate: Proportion of generation attempts that produce valid structures meeting all target criteria.

cG-SchNet demonstrates particularly strong performance in these metrics, achieving high validity rates and the ability to generate novel molecules with targeted electronic properties even beyond the training distribution [33].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Inverse Design Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function in Inverse Design | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Datasets | QM7b [34], Materials Project [15], OpenCatalyst [15] | Training data for property-structure relationships | Publicly available with varying licensing |

| Electronic Structure Codes | DFT implementations (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO), Coupled Cluster packages | High-fidelity validation of generated structures | Academic licensing available |

| Generative Modeling Frameworks | cG-SchNet [33], other 3D generative architectures | Core inverse design capability | Open-source implementations |

| Materials Standards | ASTM [36], ISO [36], SAE [37] | Reference protocols for experimental validation | Institutional subscriptions often required |

Inverse design methodologies employing conditioning on chemistry, symmetry, and electronic properties represent a transformative approach to materials discovery. Current methods demonstrate impressive capabilities in generating novel, chemically valid structures with targeted characteristics, validated against high-fidelity DFT calculations. The comparative analysis presented here reveals that conditional generative models like cG-SchNet offer particular advantages for multi-property optimization and exploration of sparsely populated chemical space regions.