Validating Catalytic Activity: A Comprehensive Guide to Multiple Turnover Experiments and Kinetic Profiling

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to design, execute, and interpret multiple turnover experiments for robust validation of catalytic activity.

Validating Catalytic Activity: A Comprehensive Guide to Multiple Turnover Experiments and Kinetic Profiling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to design, execute, and interpret multiple turnover experiments for robust validation of catalytic activity. Covering foundational kinetic principles, modern high-throughput and computational methodologies, troubleshooting for common experimental pitfalls, and rigorous validation strategies, it synthesizes current best practices. The scope includes the application of these techniques across diverse catalysts—from traditional synthetic catalysts and engineered enzymes to DNAzymes—highlighting their critical role in accelerating catalyst discovery, optimizing performance, and informing the development of more efficient and sustainable catalytic processes in biomedical and industrial contexts.

Core Principles of Catalytic Turnover: Understanding kcat, Km, and Kinetic Profiling

In the rigorous validation of catalytic activity through multiple turnover experiments, three kinetic parameters form the foundational framework for quantitative analysis: the turnover number (kcat), the Michaelis constant (Km), and the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km). These metrics provide an objective lens through which researchers can dissect and compare enzyme performance, from basic biological function to industrial and therapeutic applications. kcat defines the intrinsic speed of an enzyme's catalytic cycle, representing the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per active site per unit time [1]. Km describes the enzyme-substrate affinity relationship, quantifying the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate reaches half of its maximum value [2]. Combined as the ratio kcat/Km, these parameters create a composite index of catalytic proficiency that reflects both speed and binding affinity [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these essential parameters, equipping researchers with standardized methodologies and data interpretation frameworks critical for drug development and enzyme engineering.

Parameter Definitions and Theoretical Framework

Turnover Number (kcat)

The turnover number (kcat), also known as the catalytic constant, is defined as the limiting number of chemical conversions of substrate molecules per second that a single active site can execute [1]. This parameter represents the catalytic center's maximum activity when fully saturated with substrate, providing a direct measure of the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle. For enzymes with a single active site, kcat is explicitly referred to as the catalytic constant [1]. Mathematically, it is derived from the limiting reaction rate (Vmax) and the total concentration of active sites (e0):

kcat = Vmax / e0 [1]

In industrial catalysis contexts, Turnover Number (TON) carries a different meaning: the total number of moles of substrate a mole of catalyst can convert before deactivation, while Turnover Frequency (TOF) represents turnovers per unit time, aligning with the enzymological definition of kcat [1].

Michaelis Constant (Km)

The Michaelis constant (Km) is the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of its maximal value (Vmax) [2] [4]. This parameter provides critical information about enzyme-substrate interactions, though its interpretation requires careful consideration. Under the rapid equilibrium assumption (where substrate binding is much faster than catalysis), Km equals the dissociation constant (Kd) for the enzyme-substrate complex, directly representing substrate affinity [5]. However, under the more general steady-state assumption, Km takes a broader definition:

Km = (k₋₁ + kcat) / k₁ [5]

where k₁ and k₋₁ are the association and dissociation rate constants, respectively. This formulation reveals that Km is always greater than or equal to Kd, with the deviation determined by the relative magnitudes of kcat and k₋₁ [5]. Thus, while often used as an affinity indicator, Km is fundamentally a kinetic parameter influenced by both binding and catalytic steps.

Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km)

The ratio kcat/Km represents the apparent second-order rate constant for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction when the substrate concentration is much lower than Km [3]. This composite parameter quantifies an enzyme's effectiveness at low substrate concentrations, reflecting both substrate binding affinity and catalytic rate. It serves as a crucial comparator for an enzyme's activity toward different substrates, where a higher kcat/Km indicates greater specificity for a particular substrate [3]. When kcat/Km approaches the diffusion limit (approximately 10⁸-10⁹ M⁻¹s⁻¹), the enzyme is considered to have reached 'catalytic perfection,' meaning it cannot catalyze the reaction any better, with triosephosphate isomerase and carbonic anhydrase serving as classic examples [3].

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Key Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Mathematical Expression | Interpretation | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (Turnover Number) | Limiting number of substrate conversions per active site per second | kcat = Vmax / [E]total | Intrinsic catalytic speed when enzyme is saturated with substrate | s⁻¹ |

| Km (Michaelis Constant) | Substrate concentration at half-maximal reaction velocity | Km = [S] at V = Vmax/2 | Apparent affinity for substrate (influenced by both binding and catalysis) | M (molar) |

| kcat/Km (Catalytic Efficiency) | Apparent second-order rate constant at low substrate concentrations | kcat/Km | Specificity constant comparing enzyme effectiveness on different substrates | M⁻¹s⁻¹ |

Experimental Determination: Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Kinetic Assay Workflow

The determination of kcat, Km, and kcat/Km follows a standardized experimental approach centered on measuring initial reaction velocities at varying substrate concentrations. The following workflow outlines the core protocol, which can be adapted for different enzyme systems through specific substrate detection methods.

Key Experimental Considerations

Critical Reagent Preparation: Enzyme stocks must be accurately quantified for active site concentration, not just total protein, as kcat calculation depends on [E]total representing functional active sites [1]. Substrate solutions require precise concentration verification, as errors directly propagate to Km inaccuracies [6].

Initial Velocity Conditions: Reactions must be monitored during the linear phase where less than 5-10% of substrate has been converted to product, ensuring that product accumulation and reverse reactions do not significantly influence the measured rate [4]. This initial rate (v) is measured in concentration per time (e.g., μM·s⁻¹) and converted to turnover rate by dividing by the molar concentration of enzyme active sites [4].

Accuracy Assessment: Traditional nonlinear regression of Michaelis-Menten data often reports standard error (precision) but not accuracy. Recent approaches adapt the Accuracy Confidence Interval (ACI) framework from binding studies to propagate concentration uncertainties (δ[S] and δ[E]) into Km accuracy estimates, providing more reliable parameter bounds for decision-making in enzyme engineering and inhibitor screening [6].

Comparative Kinetic Data Across Enzyme Classes

The kinetic parameters of enzymes span remarkable ranges, reflecting evolutionary adaptation to diverse physiological roles and metabolic demands. The following comparative data illustrates this diversity and provides reference points for evaluating novel enzyme activities.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Kinetic Parameters for Representative Enzymes [2]

| Enzyme | Km (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Catalytic Proficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 | Moderate efficiency |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ | High affinity specialist |

| tRNA synthetase | 9.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 7.6 | 8.4 × 10³ | High specificity |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ | Very efficient |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ | Catalytically perfect |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ | Catalytically perfect |

The data reveals several significant patterns. Enzymes like fumarase achieve extraordinary catalytic efficiency through exceptionally high substrate affinity (low Km) combined with rapid turnover. Carbonic anhydrase exemplifies an alternative strategy with moderate Km but remarkably high kcat, still achieving catalytic perfection. The variation spans nearly eight orders of magnitude, reflecting specialized evolutionary optimization for different metabolic contexts and substrate constraints.

Advanced Applications and Computational Predictions

Machine Learning for Kinetic Parameter Prediction

Experimental determination of enzyme kinetic parameters remains laborious and low-throughput. To address this limitation, significant advances have been made in computational prediction of kcat values, enabling genome-scale kinetic modeling [7] [8] [9].

TurNuP Model: This organism-independent model predicts turnover numbers for wild-type enzymes using differential reaction fingerprints and modified Transformer Networks for protein sequence representation. TurNuP outperforms previous models and generalizes well to enzymes with low sequence similarity to training data (<40% identity) [7].

GELKcat Framework: A novel interpretable framework employing graph transformers for substrate molecular encoding and CNNs for enzyme embeddings. This model identifies key molecular substructures impacting kcat prediction, providing both predictions and mechanistic insights for drug discovery and synthetic biology applications [9].

Feature Importance: Predictive models consistently identify in silico metabolic flux as the most important feature for both in vitro kcat and in vivo apparent turnover numbers, confirming evolutionary selection pressure on enzyme efficiency. Structural features like active site depth, solvent accessibility, and exposure also significantly contribute to prediction accuracy [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in Kinetic Analysis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Preparations | Catalytic entity for parameter determination | Require accurate active site quantification for kcat calculation [1] |

| Substrate Analogs & Fluorogenic Probes | Enable continuous monitoring of reaction rates | Essential for obtaining initial velocity data at multiple time points |

| Buffer Systems with Cofactors | Maintain optimal pH and provide essential cofactors | Critical for preserving native enzyme structure and function |

| Stopped-Flow & Rapid-Kinetics Instruments | Measure very fast reaction rates | Necessary for diffusion-limited enzymes with kcat > 1000 s⁻¹ [1] |

| Computational Prediction Tools (TurNuP, GELKcat) | Predict kcat for uncharacterized enzymes | Enable genome-scale metabolic modeling [7] [9] |

Interpretation Guidelines and Common Pitfalls

Strategic Parameter Interpretation

Contextualizing kcat Values: The highest known kcat values approach the diffusion limit, with catalase exhibiting values up to 4×10⁷ s⁻¹ [1]. Acetylcholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase also display exceptionally high catalytic constants (10⁴-10⁶ s⁻¹), typically limited by substrate diffusion rates rather than chemical steps [1]. Most industrially relevant enzymes have turnover frequencies in the range of 10⁻² - 10² s⁻¹ [1].

Km as an Affinity Indicator: While Km often approximates Kd, this equivalence requires that substrate dissociation (k₋₁) is much faster than catalysis (kcat) [5]. When kcat approaches or exceeds k₋₁, Km becomes significantly larger than the true dissociation constant, potentially leading to substantial underestimation of binding affinity if misinterpreted [5].

Specificity Constant Applications: The ratio kcat/Km serves as the fundamental comparator for enzyme specificity toward competing substrates. For two substrates A and A', the ratio of reaction rates (vA/vA') depends only on (kA·a)/(kA'·a'), where kA and kA' are their respective specificity constants, demonstrating that substrate preference is determined solely by kcat/Km, not by kcat or Km individually [2].

Avoiding Common Analytical Errors

kcat/Km Misapplication: While kcat/Km effectively compares an enzyme's activity on different substrates, it is frequently mislabeled as "catalytic efficiency" when comparing different enzymes acting on the same substrate [10]. This usage can be misleading, as the parameter fundamentally reflects specificity toward alternative substrates rather than absolute efficiency across enzyme variants.

Accuracy vs. Precision in Km Determination: Standard nonlinear regression software typically reports standard error (precision) but not accuracy, potentially leading to confident but incorrect Km values [6]. Researchers should employ accuracy assessment frameworks like the Accuracy Confidence Interval (ACI) that propagate concentration uncertainties to provide more reliable parameter bounds for critical applications like enzyme engineering and inhibitor screening [6].

Physiological Context Considerations: In vitro kcat measurements represent optimal, saturated conditions that may not reflect in vivo operation where substrates are often below saturation. The effectiveness of an enzyme in its cellular context depends on both its kcat/Km and the natural substrate concentration relative to Km [4].

In the rigorous validation of catalytic activity, whether in chemical synthesis or therapeutic development, traditional endpoint analysis presents a significant blind spot. It offers a snapshot of the final reaction products but reveals nothing about the dynamic sequence of events—the mechanistic pathway—that leads to that result. This is particularly critical in evaluating catalytic processes, where the true measure of efficiency lies in the ability of a catalyst to participate in multiple turnover cycles. A single snapshot cannot distinguish a highly efficient, reusable catalyst from a spent stoichiometric reagent. The research community is therefore increasingly moving towards time-resolved analytical techniques that can capture molecular events as they unfold. This paradigm shift, from observing states to monitoring processes, is fundamental for gaining the mechanistic insight required to design safer, more active, and more efficient catalytic agents, including antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) and heterogeneous catalysts [11] [12] [13].

The Analytical Revolution: Techniques for Time-Resolved Insight

Cutting-edge methodologies now enable scientists to probe catalytic mechanisms at previously unattainable spatial and temporal resolutions. These techniques move beyond ensemble averaging to reveal heterogeneity and directly observe intermediates.

High-Resolution Microscopy and Spectroscopy

The recent development of high spatial resolution microscopy and spectroscopy tools has enabled reactivity analysis at the single-molecule or single-particle level, revealing that catalytic entities are often more heterogeneous than previously assumed [13]. Single-molecule atomic-resolution time-resolved electron microscopy (SMART-EM), for instance, allows researchers to record real-time atomic-level videos of single molecules. This technique can monitor stochastic chemical reactions and their rates as a function of temperature, enabling the deduction of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters, as well as reaction pathways, for individual molecules [12]. A unique feature is its ability to determine the rate constant (k) of chemical reactions by observing a single molecule over a sufficiently long period. For thermally driven reactions, this allows for the direct calculation of the activation free energy using the Eyring equation [12].

Other pivotal techniques in this domain include:

- Super-resolution fluorescence microscopy (SRFM): Utilizes the formation of fluorescent products to probe catalytic sites with a spatial resolution of ~10 nm, allowing for the mapping of single catalytic events [13].

- Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS): An apertureless near-field technique that combines surface-enhanced Raman scattering with the high spatial resolution of an AFM tip (~20 nm) to identify molecular vibrations and chemical transformations on surfaces [13].

- Infrared Nanospectroscopy (AFM-IR, s-SNOM): These techniques combine atomic force microscopy with infrared spectroscopy to overcome the diffraction limit of IR light, providing chemical fingerprinting at a spatial resolution of ~20 nm. AFM-IR detects the photothermal expansion induced by IR absorption, while scattering-type SNOM (s-SNOM) uses a conductive AFM tip as a nanoantenna to enhance IR light absorption locally [13].

Establishing Turnover in Biological Catalysis

In the field of therapeutic oligonucleotides, a novel cell-free reaction system has been developed to specifically quantify the multiple-turnover capability of Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA)-based antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) in RNase H-mediated scission reactions. This system places both the target RNA and RNase H in excess over the AONs, creating multiple-turnover conditions. The cleavage and release of a FRET-labeled RNA target results in a measurable increase in fluorescence, providing a direct readout of catalytic turnover efficiency [11].

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Validation

Protocol 1: Quantifying Multiple-Turnover in RNase H-Catalyzed RNA Scission

This protocol is designed to determine if an AON can be recycled in an antisense reaction [11].

- Primary Objective: To estimate the multiple-turnover ability of a series of AONs in the RNase H-mediated scission reaction.

- Experimental Setup:

- Reaction System: A cell-free system using a synthetic 20-mer target RNA conjugated with a pair of FRET dyes.

- Key Condition: Both the target RNA and E. coli–derived RNase H are in excess over the AONs (multiple-turnover conditions).

- Detection Method: The increase in fluorescence from the FRET donor is monitored over time as an indicator of RNA binding, cleavage, and AON release.

- Materials:

- FRET-labeled Target RNA: A dual-labeled 20-mer RNA complementary to the AON sequence.

- AONs: A series of LNA-based gapmer AONs (e.g., 13-mer sequences targeting apolipoprotein B-100).

- RNase H: E. coli–derived RNase H enzyme.

- Buffer: Appropriate reaction buffer (e.g., 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2).

- Procedure:

- Incubate the AON with the FRET-labeled RNA and RNase H in the reaction buffer.

- Continuously monitor the fluorescence emission of the FRET donor at an appropriate wavelength.

- Determine the initial reaction rates from the fluorescence increase. These rates serve as a quantitative measure of turnover efficiency under multiple-turnover conditions.

- Correlate the in vitro turnover efficiency with in vivo efficacy, as demonstrated in murine models [11].

Protocol 2: Visualizing Catalytic Intermediates via SMART-EM

This protocol employs SMART-EM to directly visualize intermediates in a catalytic cycle, such as alcohol dehydrogenation on a single-site MoO2 catalyst [12].

- Primary Objective: To identify key catalytic intermediates and uncover reaction pathways for single-site heterogeneous catalysts (SSHCs).

- Experimental Setup:

- Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize a catalytically competent SSHC, such as MoO2 supported on carbon nanohorns (CNH/MoO2).

- Reaction Initiation: Expose the catalyst to reactant molecules (e.g., alcohols).

- Imaging: Isolate the catalyst and characterize the formed intermediates ex situ using SMART-EM.

- Materials:

- SSHC: Molecularly defined catalyst (e.g., CNH/MoO2 from the reaction of (dme)MoO2Cl2 with carbon nanohorns).

- Substrate: Reactant molecules (e.g., methanol or ethanol for dehydrogenation).

- SMART-EM System: Transmission electron microscope capable of atomic-resolution, time-resolved imaging (e.g., operating at 80 kV with a high-speed camera up to 1,000 fps).

- Procedure:

- Synthesize and characterize the SSHC using complementary techniques (XPS, XANES, EXAFS) to confirm its structure.

- Incubate the catalyst with the substrate to allow intermediate species to form and anchor to the support.

- Isolate the catalyst from the reaction solution.

- Use SMART-EM to capture continuous, real-time images of the catalyst surface. Analyze the video to identify structural changes and infer the molecular structures of intermediates based on image size and theoretical calculations (e.g., DFT).

- Combine SMART-EM observations with kinetics, XPS, XANES, EXAFS, and DFT analysis to propose a comprehensive reaction pathway [12].

Comparative Data: Quantitative Insights from Time-Resolved Studies

Turnover Efficiency of LNA-Based AONs

Table 1: Correlation between AON properties and multiple-turnover efficiency in RNase H scission.

| AON Sequence ID | Length (nt) | Melting Temp (Tm, °C) | Relative Turnover Efficiency | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoB-13a [11] | 13 | 59 | High | Efficient multiple turnover |

| ApoB-13h [11] | 13 | 48 | Low | Inadequate binding impedes turnover |

| ApoB-10a [11] | 10 | 28 | Very Low | Too short/weak binding for efficient activity |

| ApoB-20a [11] | 20 | 76 | Reduced | Very high Tm may hinder recycling |

Performance of High-Resolution Techniques

Table 2: Comparison of techniques for time-resolved, mechanistic analysis in catalysis.

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Key Measurable | Primary Application | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMART-EM [12] | Atomic | Real-time visualization of intermediates & rates | Heterogeneous & Single-Site Catalysis | Direct observation of single-molecule reactions and kinetic parameter determination. |

| SRFM [13] | ~10 nm | Location of single catalytic events via fluorescence | Homogeneous & Heterogeneous (Electro)Catalysis | High sensitivity for detecting fluorescent products at catalytic sites. |

| TERS [13] | ~20 nm | Chemical identity via nanoscale Raman mapping | Surface Catalysis | Provides molecular vibrational information with high spatial resolution. |

| IR Nanospectroscopy [13] | ~20 nm | Chemical fingerprint via nanoscale IR absorption | Material & Catalysis Science | Nondestructive chemical identification of organic and inorganic materials. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for advanced catalytic mechanistic studies.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| LNA-based Gapmer AONs [11] | Chimeric antisense oligonucleotides with a central DNA stretch for RNase H recruitment, flanked by affinity-enhancing LNA modifications. Used to study turnover in RNA cleavage. |

| FRET-labeled RNA Probes [11] | Target RNA sequences labeled with fluorescent dyes. Cleavage and dissociation during a turnover event produce a measurable increase in fluorescence. |

| Single-Site Heterogeneous Catalysts (SSHCs) [12] | Molecularly defined catalysts derived from well-defined precursors on solid supports (e.g., CNH/MoO2). Enable precise mechanistic studies by providing uniform active sites. |

| Carbon Nanohorns (CNH) [12] | A type of carbon support compatible with SMART-EM, used to anchor molecular catalysts for high-resolution imaging of surface intermediates. |

Visualizing the Workflow: From Endpoint to Mechanism

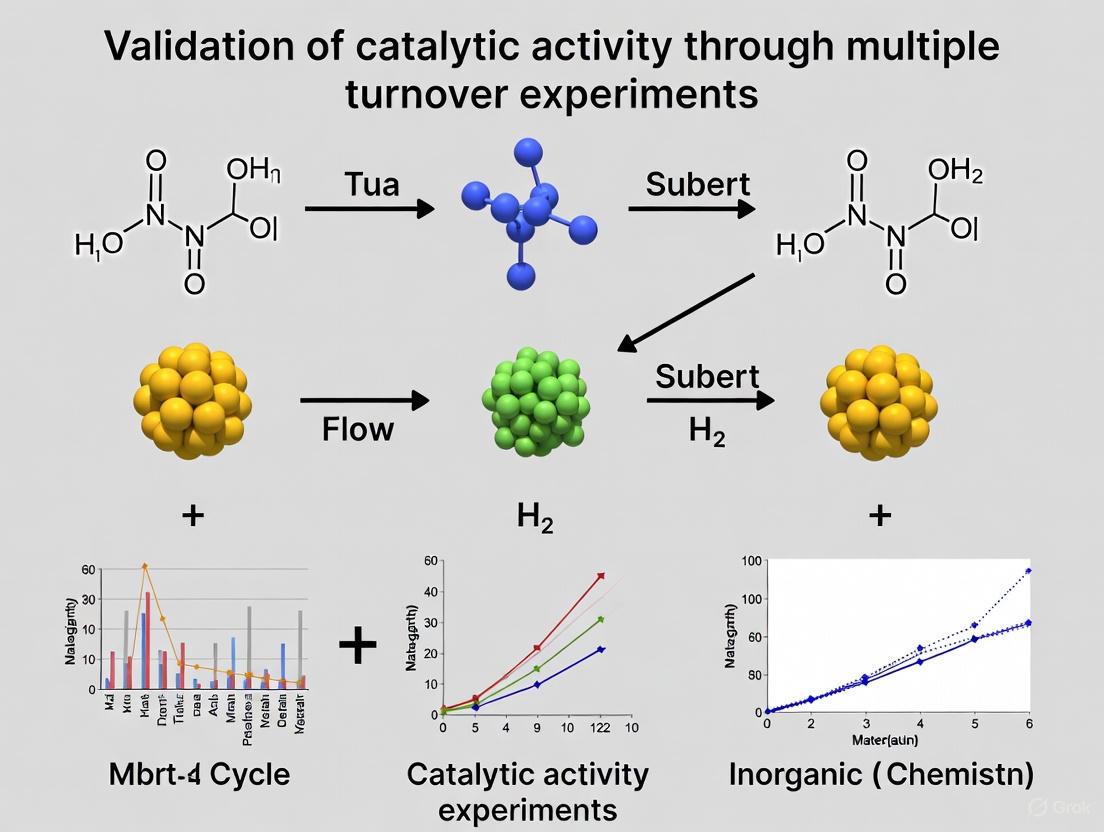

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental conceptual shift from endpoint analysis to a time-resolved, mechanism-focused investigation, and the experimental pathways it enables.

The reliance on endpoint data represents a significant limitation in the pursuit of deep mechanistic understanding in catalysis. As demonstrated by the studies of antisense oligonucleotides and single-site heterogeneous catalysts, moving beyond this static view is not merely an academic exercise. The implementation of time-resolved techniques such as fluorescence-based turnover assays and SMART-EM provides unambiguous, quantitative evidence of multiple turnover events, directly revealing the intermediates and energy landscapes of catalytic cycles. This paradigm shift, powered by a new toolkit of high-resolution methods, is fundamental for the rational design of next-generation catalysts in both chemical synthesis and therapeutic development, ensuring that efficacy is grounded in a true understanding of dynamic molecular processes.

In the rigorous validation of catalytic performance, particularly within drug development and synthetic chemistry, the concepts of activity, selectivity, and stability serve as fundamental pillars. While activity measures the catalyst's speed, selectivity dictates its precision, and stability determines its operational lifespan. Framing these properties within the context of multiple turnover experiments is critical, as it moves beyond simple initial activity to confirm the catalyst's ability to repeatedly execute its function under relevant conditions. This guide provides an objective comparison of how these kinetic parameters are validated across different catalytic systems, highlighting key experimental methodologies and data interpretation.

Core Kinetic Parameters: A Comparative Framework

The table below defines the core kinetic parameters and their significance in catalyst validation.

| Kinetic Parameter | Key Metric(s) | Significance in Catalysis | Primary Experimental Method for Determination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Turnover Number (TON), Turnover Frequency (TOF), V~max~, k~cat~ | Measures the rate of substrate conversion; indicates raw catalytic speed and efficiency. [11] [14] | Initial rate measurements under multiple-turnover conditions; progress curve analysis. [11] |

| Selectivity | Faradaic Efficiency (Electrocatalysis), Product Distribution Ratio | Determines the catalyst's precision in guiding reactions toward a desired product over potential by-products. [15] [16] | Analysis of reaction outputs (e.g., via GC/MS, HPLC) under varied potentials/conditions; inhibition studies. [15] |

| Stability | Total Turnover Number (TTON), Catalyst Lifespan, Deactivation Rate | Quantifies the catalyst's functional durability and resistance to deactivation over time. [11] | Long-term time-course experiments; monitoring product yield and catalyst integrity over multiple cycles. [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Profiling

Establishing Multiple-Turnover Activity for Oligonucleotides

This protocol, adapted from studies on Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA)-based antisense oligonucleotides, is designed to confirm that a catalyst can be recycled. [11]

- Objective: To determine the multiple-turnover capability of gapmer AONs in an RNase H-mediated scission reaction. [11]

- Materials:

- Target RNA: Synthetic 20-mer RNA conjugated with a pair of FRET (Förster resonance energy transfer) dyes. [11]

- Catalyst: A series of LNA-based antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) with varying lengths and melting temperatures (T~m~). [11]

- Enzyme: E. coli-derived RNase H. [11]

- Buffer: 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). [11]

- Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: The cell-free reaction system is devised with both the target RNA and RNase H in excess over the AON catalyst, creating multiple-turnover conditions. [11]

- Kinetic Measurement: The increase in fluorescence from the FRET donor is monitored in real-time. This fluorescence signal corresponds directly to the cleavage, release, and subsequent re-binding of the AON to a new RNA molecule. [11]

- Data Analysis: The initial reaction rates are determined from the fluorescence data. AONs demonstrating sustained cleavage activity under these conditions are confirmed to have high turnover efficiency. [11]

- Key Data Interpretation: Research indicates that AONs with melting temperatures (T~m~) between 40°C and 60°C efficiently elicit multiple rounds of RNA scission, whereas those with excessively high T~m~ (>80°C) show reduced silencing activity, likely due to an inability to recycle. [11]

Probing Potential-Mediated Selectivity in Electrocatalysis

This methodology uses a microkinetic model to understand how catalyst identity and external factors govern product distribution, such as in the CO~2~ Reduction Reaction (CO~2~RR). [15]

- Objective: To analyze the kinetic factors controlling the competing production of CO vs. formic acid (FA) in CO~2~RR on various metal surfaces. [15]

- Computational Details:

- Electronic Structure: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations are performed using a plane wave basis set to determine adsorption energies of key intermediates like COOH, HCOO, and CO*. [15]

- Solvation Model: An implicit solvation model (VASPsol) is used to describe the solvation effect of adsorbates. [15]

- Kinetic Barrier Calculation: Reaction barriers for electrochemical steps are calculated using a "four-point method" based on Marcus charge transfer theory, which allows for the computation of potential-dependent kinetics. [15]

- Microkinetic Modeling: The computed kinetic and thermodynamic parameters are integrated into a microkinetic model to simulate current density and Faradaic efficiency. [15]

- Key Data Interpretation: The study reveals a potential-mediated mechanism: at less negative potentials, thermodynamics favor formic acid, while at more negative potentials, kinetics favor CO production. [15] The binding energies of key intermediates (HCOO, COOH, CO*) serve as a three-parameter descriptor for predicting catalytic selectivity. [15]

Data Integration for Robust Turnover Number Estimation

PRESTO (Protein-abundance-based correction of turnover numbers) is a constraint-based approach designed to correct in vitro turnover numbers (k~cat~) by integrating proteomic data, leading to more accurate predictions of cellular phenotypes. [14]

- Objective: To correct initial k~cat~ values by matching predictions from protein-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (pcGEMs) with measured cellular growth rates across multiple conditions. [14]

- Methodology:

- Data Integration: Protein abundance data and exchange fluxes from diverse growth conditions are integrated into a pcGEM. [14]

- Optimization Problem: A linear program is solved to minimize a weighted combination of the average relative error in predicted growth rates and the magnitude of corrections applied to the initial k~cat~ values. [14]

- Cross-Validation: K-fold cross-validation is employed to ensure the robustness of the corrected k~cat~ set and to prevent overfitting. [14]

- Key Data Interpretation: When applied to S. cerevisiae and E. coli models, PRESTO-corrected k~cat~ values led to significantly more accurate predictions of condition-specific growth rates compared to models using initial in vitro k~cat~ values or values corrected by a contending heuristic. [14] This demonstrates that in vivo stability and performance are better predicted by integrating data across multiple turnover conditions.

Visualizing Kinetic Relationships and Workflows

Multiple Turnover Kinetic Analysis

Selectivity Determinants in CO2RR

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions for conducting rigorous kinetic profiling experiments.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Kinetic Profiling | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Gapmers | Chimeric antisense oligonucleotides that recruit RNase H; used to study turnover via RNA cleavage. [11] | Central DNA stretch flanked by affinity-enhancing, nuclease-resistant LNA modifications. [11] |

| FRET-Labeled RNA Substrates | Synthetic RNA targets enabling real-time, fluorescence-based monitoring of catalytic cleavage events. [11] | Dual dyes allow detection of cleavage via change in fluorescence resonance energy transfer. [11] |

| RNase H Enzyme | Ribonuclease that cleaves the RNA strand in an RNA-DNA duplex; the effector in antisense turnover assays. [11] | Cleavage activity is essential for multiple-turnover experiments with AONs. [11] |

| Microkinetic Model (e.g., Marcus Theory) | Computational framework to simulate potential-dependent reaction rates and barriers from first principles. [15] | Goes beyond thermodynamics to model kinetics, explaining selectivity shifts with potential. [15] |

| Protein-Constrained GEM (pcGEM) | Genome-scale metabolic model integrating enzyme abundance and kcat values to predict cellular phenotypes. [14] | Allows for in vivo-like estimation of catalytic capacity and flux under resource constraints. [14] |

| Lineweaver-Burk Plots | Linearized double-reciprocal plots of Michaelis-Menten kinetics for determining Km and Vmax. [17] | Slope represents Km/Vmax; y-intercept is 1/Vmax. Useful for diagnosing inhibition type. [17] |

Catalyst informatics is an emerging scientific discipline that applies data science principles to accelerate the discovery and optimization of catalysts. By treating catalytic materials as entities in a high-dimensional design space, this approach leverages statistical learning, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling to uncover relationships between catalyst composition, structure, and performance that would remain hidden through traditional experimental approaches alone [18]. This paradigm shift addresses a fundamental challenge in catalysis research: navigating an exponentially large design space where performance is influenced by numerous interacting factors including composition, morphology, particle size, support material, and surface characteristics [19].

The core value proposition of catalyst informatics lies in its ability to transform raw experimental and computational data into actionable knowledge. This data-information-knowledge hierarchy enables researchers to move beyond one-variable-at-a-time optimization toward multidimensional screening where numerous parameters can be explored in parallel [19] [18]. For the validation of catalytic activity through multiple turnover experiments, informatics provides essential frameworks for interpreting complex kinetic data, identifying optimal operating conditions, and predicting long-term catalyst stability – all critical factors for practical catalyst implementation.

Experimental Paradigms in Catalyst Informatics

High-Throughput Experimental Screening

Recent advances have demonstrated the power of automated, real-time optical scanning approaches for assessing catalyst performance. One innovative methodology employs a simple on-off fluorescence probe that exhibits a shift in absorbance and strong fluorescent signal when a non-fluorescent nitro-moiety is reduced to its amine form [19]. This approach enables high-throughput catalyst screening using standard well-plate readers, making sophisticated kinetic profiling accessible without requiring prohibitively expensive instrumentation.

The experimental protocol involves populating 24-well polystyrene plates with reaction mixtures containing candidate catalysts (typically 0.01 mg/mL), the fluorogenic probe (30 µM), and reducing agents (1.0 M aqueous N₂H₄) in a total volume of 1.0 mL [19]. Each sample well is paired with a reference well containing the anticipated end product to enable accurate concentration quantification. After reaction initiation, plates are placed in multi-mode readers programmed for orbital shaking and automated spectroscopic measurement at regular intervals (typically 5 minutes over 80 minutes total), collecting both fluorescence intensity (excitation: 485 nm, emission: 590 nm) and full absorption spectra (300-650 nm) [19]. This methodology generates rich, time-resolved datasets that capture reaction progress rather than just endpoint conversions, providing insights into catalytic kinetics, intermediate formation, and potential deactivation processes.

Standardized Benchmarking Databases

Complementing experimental screening approaches, the field has recognized the critical need for standardized benchmarking data to enable meaningful catalyst comparisons. CatTestHub has emerged as an open-access database dedicated to benchmarking experimental heterogeneous catalysis data, currently spanning over 250 unique experimental data points collected across 24 solid catalysts and 3 distinct catalytic chemistries [20]. This platform addresses a fundamental limitation in traditional catalysis research: the inability to quantitatively compare catalytic materials due to variability in reaction conditions, reporting procedures, and data types across different studies.

The database architecture follows FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse), incorporating detailed reaction condition parameters, material characterization data, and reactor configuration information [20]. Each entry includes unique identifiers such as digital object identifiers (DOIs) and ORCIDs to enhance traceability and accountability. For researchers focused on validating catalytic activity through multiple turnover experiments, such standardized resources provide essential reference points for contextualizing new findings against established benchmarks under consistent experimental conditions.

Quantitative Comparison of Catalyst Performance

The integration of catalyst informatics with high-throughput experimentation enables multidimensional evaluation frameworks that extend beyond simple activity metrics. The table below summarizes key performance indicators employed in comprehensive catalyst assessment:

Table 1: Multidimensional Catalyst Evaluation Criteria in Informatics Approaches

| Performance Dimension | Measurement Methodology | Quantification Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Activity | Reaction completion time, Conversion rate | Time to reach target conversion, Turnover frequency (TOF) |

| Kinetic Profiling | Real-time fluorescence/absorbance monitoring | Progress curve analysis, Rate constant determination |

| Selectority | Spectral monitoring of intermediates | Absorbance at characteristic wavelengths (e.g., 550 nm for azo/azoxy intermediates) |

| Stability | Evolution of isosbestic points | Consistency of absorbance at isosbestic point (e.g., 385 nm) over time |

| Sustainability | Material life-cycle assessment | Abundance, price, recoverability, safety scoring |

In a recent implementation screening 114 different catalysts for nitro-to-amine reduction, researchers developed a scoring system that compared catalysts in terms of reaction completion times, material abundance, price, recoverability, and safety [19]. This multifaceted evaluation approach revealed that the highest-activity catalysts were not necessarily optimal when sustainability and economic factors were considered, highlighting the value of informatics in balancing competing design objectives.

The table below illustrates how different catalyst classes perform across these multidimensional criteria:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Catalyst Classes in Nitro-to-Amine Reduction

| Catalyst Class | Representative Example | Average Completion Time (min) | Selectivity Score | Stability Performance | Cumulative Sustainability Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supported Copper | Cu@charcoal | 45-60 | High | Stable isosbestic point | Medium-High |

| Zeolites | Zeolite NaY | >80 (33% yield) | Low | Unstable isosbestic point | High |

| Noble Metals | Pt/C, Pd/C | 15-30 | Medium-High | Variable | Low (price/abundance) |

| Transition Metal Oxides | Various oxides | 50-75 | Medium | Generally stable | Medium-High |

Catalyst Informatics Platforms and Workflows

The practical implementation of catalyst informatics relies on specialized software platforms that integrate data management, analysis, and prediction capabilities. One such platform, Catalyst Acquisition by Data Science (CADS), provides a web-based integrated environment with three core functionalities: (1) a repository for data sharing and publishing, (2) an analytic workspace for exploratory visual analysis, and (3) catalyst property prediction tools with pretrained machine learning models [21]. This platform decreases barriers to entry for researchers in catalytic chemistry seeking to apply informatics approaches to their data.

The end-to-end workflow for catalyst informatics follows a systematic pipeline from data generation to prediction and validation, as illustrated in the following diagram:

Diagram 1: Catalyst informatics workflow showing the iterative cycle from data generation to experimental validation.

This workflow highlights the iterative nature of modern catalyst discovery, where predictions inform new experiments, and experimental results refine predictive models. The integration of community databases ensures that knowledge accumulates across research groups, accelerating collective progress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing catalyst informatics approaches requires both computational tools and experimental resources. The following table details key components of the catalyst informatics toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Catalyst Informatics

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Access Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informatics Platforms | CADS (Catalyst Acquisition by Data Science) [21] | Integrated data analysis, visualization, and prediction | Web-based platform |

| Benchmarking Databases | CatTestHub [20], Catalysis-Hub.org [20] | Standardized reference data for catalyst performance comparison | Open access |

| Experimental Screening | High-throughput fluorogenic assay [19] | Parallelized kinetic profiling of catalyst libraries | Laboratory implementation |

| Computational Data | Material Projects, OC20 [20] | First-principles calculation data for catalyst properties | Open access |

| Descriptor Libraries | Adsorption energy databases, Surface structure maps [18] | Atomic-scale features for predictive modeling | Varies |

For researchers focusing on multiple turnover experiments, these resources provide essential infrastructure for contextualizing results against established benchmarks, accessing predictive models for catalyst selection, and implementing standardized screening protocols that generate comparable data across different laboratories.

Machine Learning and Predictive Modeling in Catalyst Informatics

Machine learning (ML) has become an indispensable component of catalyst informatics, enabling the prediction of catalytic properties and performance from both experimental and computational data. These approaches can be broadly categorized into top-down and bottom-up strategies [18]. Top-down methods utilize macroscopic catalyst properties (composition, phase, surface area, particle size) and operating conditions to directly predict catalytic performance, allowing direct utilization of experimental data on industrial catalysts. Bottom-up approaches leverage first-principles data to provide atomistic insights, enabling high-quality predictions for catalyst screening through features such as adsorption energies coupled with electronic and geometric descriptors [18].

Recent advances have demonstrated ML's capability to overcome traditional scaling relationships that limit catalyst performance. For instance, ML algorithms can identify complex descriptor combinations that more accurately predict catalytic activity than single-parameter descriptors [18]. Furthermore, ML-interatomic potentials (MLPs) have dramatically reduced the computational cost of quantum mechanical calculations, enabling large-scale simulations of catalyst dynamics under reaction conditions [18]. These capabilities are particularly valuable for understanding multiple turnover scenarios, where catalyst evolution over time can significantly impact long-term performance.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite rapid progress, catalyst informatics faces several critical challenges that must be addressed to fully realize its potential. The quality and quantity of available data remains a fundamental limitation, with efforts ongoing to develop more comprehensive databases [18]. Additionally, the integration of data across different sources and scales – from atomic-scale computations to reactor-level performance – requires sophisticated multiscale modeling approaches that can seamlessly connect phenomena across orders of magnitude in space and time [18].

For the specific context of validating catalytic activity through multiple turnover experiments, future developments will likely focus on improved kinetic modeling that can more accurately capture complex reaction networks and catalyst deactivation pathways. The incorporation of temporal analysis of products (TAP) and operando spectroscopy data under reaction conditions will enhance the ability to learn governing equations directly from experiments rather than relying solely on approximate physical models [18]. As these capabilities mature, catalyst informatics will increasingly enable truly predictive catalyst design, reducing the traditional trial-and-error approach and accelerating the development of sustainable catalytic technologies.

Modern Techniques for Turnover Analysis: From High-Throughput Screening to Deep Learning

Real-Time Kinetic Profiling with High-Throughput Fluorogenic Assays

High-throughput fluorogenic assays represent a transformative approach in modern biochemical research and drug discovery, enabling the rapid, quantitative analysis of enzyme activities and catalytic processes. These assays leverage the change in fluorescence that occurs when a non-fluorescent substrate is converted to a fluorescent product by a catalytic entity, allowing researchers to monitor reaction kinetics in real-time with high sensitivity. The fundamental advantage of this methodology lies in its ability to generate continuous, time-resolved kinetic data from hundreds to thousands of parallel reactions, moving beyond simplistic endpoint analyses to capture the dynamic behavior of biological systems [19]. This capability is particularly valuable for validating catalytic activity through multiple turnover experiments, as it provides direct insight into the stability, efficiency, and mechanistic properties of catalysts under investigation.

The application landscape for these assays is remarkably diverse, spanning catalyst discovery [19], antibiotic resistance profiling [22] [23], transcription elongation studies [24], and diagnostic development for conditions like Alzheimer's disease [25]. This versatility stems from the adaptable nature of fluorogenic probe design, where specific substrate moieties are strategically linked to fluorophores through cleavable bonds tailored to target enzymes or catalytic reactions. The integration of this core biochemistry with automated liquid handling, multi-well plate readers, and advanced detection systems has established fluorogenic assays as indispensable tools for researchers demanding both high throughput and high-quality kinetic data [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Assay Principle and General Workflow

The fundamental principle underlying fluorogenic assays involves the enzymatic or catalytic conversion of a non-fluorescent substrate into a highly fluorescent product. This is typically achieved through probes where a fluorophore is quenched either by proximity to a quencher molecule or by its own chemical environment within the substrate. Upon catalytic action—such as hydrolysis, reduction, or elongation—the fluorophore is released, restoring its fluorescence. The resulting increase in fluorescence intensity over time directly correlates with reaction progress, enabling real-time kinetic monitoring [22] [24] [23].

A generalized workflow begins with assay preparation in multi-well plates (e.g., 24, 96, 384, or 1536-well formats), where reaction components are combined. The plate is then transferred to a plate reader equipped with appropriate excitation and emission filters. The instrument periodically scans each well over a defined duration, recording fluorescence intensities that are subsequently processed to generate kinetic profiles for each reaction [19].

Protocol for Catalyst Screening via Nitro-to-Amine Reduction

This protocol, adapted from a study screening 114 catalysts, details the process for monitoring reduction reactions [19].

- Probe Design: The assay utilizes a nitronaphthalimide (NN) probe that is non-fluorescent in its nitro form. Upon reduction to the amine (AN), the molecule exhibits a strong fluorescent signal, with absorbance shifting from 350 nm to 430 nm [19].

- Well Plate Setup:

- A 24-well polystyrene plate is populated with 12 reaction wells and 12 corresponding reference wells.

- Reaction Well (S): Contains 0.01 mg/mL catalyst, 30 µM NN substrate, 1.0 M aqueous N₂H₄, 0.1 mM acetic acid, and H₂O for a total volume of 1.0 mL.

- Reference Well (R): Contains an identical mixture, except the NN substrate is replaced by its reduced amine product (AN). This controls for signal stability and environmental effects [19].

- Data Acquisition:

- The plate is placed in a multi-mode plate reader (e.g., Biotek Synergy HTX).

- The reader executes a cycle every 5 minutes for 80 minutes: 5 seconds of orbital shaking, fluorescence reading (Ex/Em = 485/590 nm), and a full absorption spectrum scan (300–650 nm) [19].

- Data Processing:

- Raw data is converted to CSV files and transferred to a database (e.g., MySQL).

- Fluorescence and absorbance values are plotted over time. The ratio of the reaction well signal to the reference well signal can be used to approximate conversion yield.

- For fast reactions exceeding 50% conversion in 5 minutes, a fast kinetics protocol with more frequent data points is employed for the early phase [19].

Protocol for Single Nucleotide Incorporation Kinetics in Transcription

This protocol uses a fluorescent base analog to study the real-time kinetics of RNA polymerase [24].

- Probe Design: The assay incorporates 2-Aminopurine (2AP), a fluorescent analog of adenine, at specific sites within a designed RNA:DNA elongation substrate. The fluorescence of 2AP is highly sensitive to its local base-stacking environment, which changes during nucleotide incorporation [24].

- Elongation Substrate Preparation:

- A promoter-free elongation substrate is created by annealing DNA strands to form a 9-bp bubble, to which a short RNA primer is annealed.

- A single 2AP molecule is placed at a strategic position, such as the

n+1position in the template strand, which has been shown to yield large fluorescence increases upon correct NTP incorporation [24].

- Stopped-Flow Kinetics:

- A pre-formed complex of the 2AP-incorporated elongation substrate (200 nM) and RNA polymerase (400 nM) is rapidly mixed with varying concentrations of the correct NTP in a stopped-flow instrument.

- The 2AP fluorescence (Ex/Em = 310/370 nm) is monitored from milliseconds to seconds [24].

- Data Analysis:

- The fluorescence time trace is fitted to a single exponential equation to obtain the observed rate constant (

k_obs) at each NTP concentration. - A plot of

k_obsversus[NTP]is fitted to a hyperbolic function to derive the maximum incorporation rate constant (k_pol) and the apparent dissociation constant (K_d) for the NTP [24].

- The fluorescence time trace is fitted to a single exponential equation to obtain the observed rate constant (

Protocol for Detection of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

This protocol describes a fluorogenic assay for detecting carbapenemase-producing bacteria directly from blood cultures [22] [23].

- Probe Design: The probe is a chimeric molecule composed of a carbapenem moiety (the substrate) linked to a fluorophore (e.g., umbelliferone) via a benzyl ether linker. Hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring by carbapenemase triggers a cascade reaction, releasing the fluorescent umbelliferone [22].

- Sample Preparation from Blood Cultures:

- A pellet of bacteria is obtained from a positive blood culture bottle via centrifugation and a saponin wash method.

- The bacterial pellet is lysed with a protein extraction reagent (e.g., B-PER II), vortexed, and centrifuged. The supernatant containing the enzymes is used for the assay [22].

- Fluorogenic Reaction:

- The supernatant (30 µL) is mixed with PBS buffer (100 µL) and the fluorogenic probe (13 µL) in a 96-well microplate.

- The fluorescence (Ex/Em = 360/465 nm) is measured every minute for 50 minutes using a fluorometer [22].

- Data Interpretation:

- The fluorescence signal generated by 50 minutes is calculated by subtracting the value at 0 minutes.

- A significant increase in fluorescence compared to a negative control (a non-carbapenemase-producing strain) indicates the presence of carbapenemase activity [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision workflow for implementing these different fluorogenic assay protocols based on the research objective.

Performance Comparison of Fluorogenic Assay Applications

The quantitative performance of fluorogenic assays varies across applications, reflecting differences in probe design, detection sensitivity, and throughput. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from several studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Fluorogenic Assays in Various Applications

| Application Area | Key Performance Metrics | Throughput & Scale | Kinetic Parameters Measured | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Screening | Monitored 114 catalysts; data points: ~32 per sample (Abs & FL); total >7,000 data points. | 24-well plate format; 80 min total reaction time with 5 min intervals. | Reaction completion times; kinetic profiles from time-resolved UV-Vis and fluorescence. | [19] |

| Transcription Elongation | k_pol = 145-209 s⁻¹; K_d = 28-124 µM; efficiency (k_pol/K_d) = 2.0-7.5 µM⁻¹s⁻¹. |

Stopped-flow, real-time single nucleotide addition. | Single nucleotide incorporation rate (k_pol), ground-state NTP dissociation constant (K_d). |

[24] |

| Pathogen Detection (CPE) | Sensitivity: 98.3-100%; Specificity: 98.1-98.7%; PPA: 98.3-100%; NPA: 98.1-98.7%. | 96-well plate; 50 min assay time. | Fluorescence signal increase over 50 min to distinguish carbapenemase producers. | [22] |

| Diagnostic (AD from tears) | Detection Limit: 236 aM; Analytical Range: 0.320–1000 fM; Sensitivity: 90%; Specificity: 100%. | 1 hour total assay time. | Quantification of CAP1 protein concentration in tear fluid. | [25] |

The data demonstrates that fluorogenic assays achieve a powerful combination of high sensitivity, wide dynamic range, and operational speed. The catalyst screening and transcription elongation applications highlight the method's strength in extracting detailed kinetic parameters (k_pol, K_d), which are essential for understanding catalytic mechanisms and fidelity [19] [24]. In contrast, the diagnostic applications emphasize exceptional sensitivity (reaching attomolar levels) and high clinical accuracy, enabling the detection of low-abundance biomarkers or resistant pathogens with a short turnaround time [22] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of real-time kinetic profiling relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in fluorogenic assays.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Fluorogenic Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function and Role in the Assay | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Probes | The core substrate that yields a fluorescent signal upon catalytic conversion. Design is target-specific. | Nitronaphthalimide (NN) for nitro-reductases [19]; Carbapenem-umbelliferone for β-lactamases [22]; 2-Aminopurine (2AP) in nucleic acid templates [24]. |

| Multi-well Plates | The miniaturized reaction vessel enabling high-throughput parallel experimentation. | 24-well [19], 96-well [22], 384-well, or 1536-well plates. Material (e.g., polystyrene) must be suitable for optical measurements. |

| Detection Instrumentation | Equipment to excite the fluorophore and detect the emitted fluorescence signal over time. | Multi-mode plate readers (e.g., Biotek Synergy HTX) [19]; Fluorometers (e.g., Tecan Infinite F200pro) [22]; Stopped-flow spectrofluorometers [24]. |

| Protein Extraction Reagents | Used to lyse cells and release intracellular enzymes for activity screening. | B-PER II (Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent) [22]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Functionalized solid supports used in advanced immunoassays for target capture and separation. | Antibody-immobilized Magnetic Nanoparticles (Ab-MNPs) for concentrating biomarkers from complex fluids like tears [25]. |

The workflow for a typical high-throughput fluorogenic assay, from probe design to data analysis, is visualized below.

High-throughput fluorogenic assays have unequivocally established themselves as a cornerstone technology for real-time kinetic profiling across diverse scientific fields. Their power lies in the seamless fusion of high-throughput capability with the rich, quantitative data necessary for validating catalytic activity through multiple turnover experiments. As evidenced by the protocols and data presented, these assays are remarkably adaptable, enabling everything from the discovery of novel heterogeneous catalysts and the dissection of fundamental enzymatic mechanisms to the rapid diagnosis of clinically critical pathogens and neurodegenerative diseases.

The continued evolution of this field—driven by advances in probe chemistry, miniaturization, automation, and data analysis—promises to further expand the boundaries of what is possible in quantitative biology and chemistry. By providing a direct, sensitive, and scalable window into dynamic catalytic processes, fluorogenic assays will remain an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to understand and harness the power of catalytic activity.

Leveraging Plate Readers for Parallelized Reaction Monitoring

This guide objectively compares the performance of modern microplate readers in enabling parallelized reaction monitoring for validating catalytic activity through multiple turnover experiments. We evaluate core detection technologies—absorbance, fluorescence, fluorescence polarization, and luminescence—against key parameters critical for enzymatic and binding assays. Supporting experimental data demonstrate how instrument selection directly impacts sensitivity, throughput, and data quality in kinetic studies. For researchers in drug discovery and enzymology, this comparison provides a framework for selecting optimal reader configurations to capture robust, real-time kinetic data across hundreds of simultaneous reactions.

Microplate readers have revolutionized reaction monitoring by enabling the parallelized analysis of dozens to hundreds of biochemical reactions under identical conditions. This parallelization is indispensable for multiple turnover experiments, where researchers must quantify catalytic activity, determine enzyme kinetics (Km, Vmax), and characterize inhibitor mechanisms under steady-state conditions. Unlike endpoint measurements that provide a single snapshot, kinetic monitoring tracks reaction progress continuously, revealing the temporal dynamics of substrate conversion and product formation essential for rigorous enzyme characterization [27].

The core principle of parallelized reaction monitoring leverages the microplate's standardized format to compartmentalize individual reactions while subjecting them to identical environmental control and measurement parameters. This approach eliminates inter-assay variability and dramatically increases throughput compared to traditional cuvette-based methods. For validating catalytic activity, kinetic data acquired through parallelized monitoring provides the robust dataset needed to calculate initial velocities, distinguish between different classes of inhibitors, and generate structure-activity relationships in drug discovery programs [28].

Core Detection Technologies for Reaction Monitoring

Microplate readers offer multiple detection modalities, each with distinct advantages for specific reaction monitoring applications. The table below compares the primary technologies used in kinetic studies:

Table 1: Comparison of Microplate Reader Detection Methods for Kinetic Assays

| Detection Method | Principle | Benefits for Kinetic Studies | Common Kinetic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbance | Measures light absorbed by chromophores | Label-free; cost-effective; robust | Enzyme kinetics (e.g., NADH at 340 nm), bacterial growth curves |

| Fluorescence Intensity | Detects emitted light after excitation | High sensitivity; wide dynamic range | Calcium flux, protease activity, reporter gene expression |

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) | Measures rotation speed of fluorescent molecules | Homogeneous (no wash steps); ratiometric | Binding assays, methyltransferase activity, immunoassays |

| Luminescence | Detects light from chemical reactions | Highest sensitivity; no background from excitation light | ATP quantification, reporter gene assays, cell viability |

| Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET) | Combines time delay with energy transfer | Reduced background; high sensitivity | Protein-protein interactions, post-translational modifications |

Beyond these core technologies, specialized approaches like AlphaScreen utilize bead-based proximity assays for studying molecular interactions without washing steps, while turbidimetry measures light scattering for applications like bacterial growth monitoring [29]. The selection of detection technology fundamentally shapes experimental design, with factors like assay homogeneity, required sensitivity, and the need for internal controls guiding the choice between these modalities for parallelized reaction monitoring.

Experimental Design for Kinetic Analysis

Measurement Modes: Endpoint vs. Kinetic

Microplate readers operate in distinct measurement modes that determine how reaction progress is captured:

Endpoint Mode: A single measurement is taken after a fixed incubation period, providing information about the final state of the reaction. This mode is simple and fast, making it suitable for high-throughput screening where thousands of compounds are tested initially [27]. However, it offers no information about reaction progression and may miss subtleties in reaction kinetics.

Kinetic Mode: Multiple measurements are taken over a defined time period to monitor reaction progress in real-time. This mode is essential for determining reaction rates and enzyme kinetic parameters. Kinetic measurements can be further divided into:

- Well Mode: Used for fast kinetics (e.g., enzyme initial rates), where multiple measurements are taken rapidly in the same well before moving to the next well [27] [28].

- Plate Mode: Used for slower kinetics (e.g., bacterial growth), where each well is measured once per cycle across multiple cycles [27].

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting appropriate measurement modes based on experimental requirements:

Experimental Protocol: Enzyme Kinetics Using Absorbance Detection

The hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) to p-nitrophenol (pNP) serves as a model system for demonstrating enzyme kinetic measurements on a microplate reader [28]:

Table 2: Key Reagents for pNPA Enzyme Kinetic Assay

| Reagent | Function | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| p-Nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) | Enzyme substrate | Varying (e.g., 0.02-2 mM) |

| Phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) | Maintain optimal pH | 50 mM |

| Esterase enzyme | Biological catalyst | Diluted appropriately |

| DMSO | Solvent for substrate stock | <5% of total volume |

| p-Nitrophenol (pNP) | Standard for calibration curve | 0-0.1 μmol |

Procedure:

- Prepare a 10 mM stock solution of pNPA in DMSO

- Pipette 190 μL phosphate buffer and 10 μL enzyme preparation into each well

- Use onboard injectors to add 40 μL of pNPA at different concentrations

- Immediately measure absorbance at 410 nm every second for 90 seconds at 37°C

- Include controls without enzyme (blank) and without substrate (negative control)

- Generate a pNP standard curve to convert ΔOD/min to μmol product/min

Data Analysis:

- Calculate initial velocities (v) at each substrate concentration ([S])

- Fit data to Michaelis-Menten equation: v = (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S])

- Determine Km (Michaelis constant) and Vmax (maximal velocity)

- Compare results from linear transformations (Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee, Hanes)

This protocol demonstrates how parallelized monitoring enables complete enzyme characterization from a single experiment, with the microplate format allowing simultaneous testing of multiple substrate concentrations with replicates [28].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Plate Reader Technologies

Sensitivity and Dynamic Range Comparison

A comparative study evaluating detection systems for cellular assays revealed significant performance differences in fluorescence detection. When measuring fluorescent protein-labeled cells, the detection limits varied substantially between instruments [30]:

Table 3: Sensitivity Comparison Across Detection Platforms

| Instrument Platform | Detection Limit (Cells/Well) | Relative Sensitivity | Z' Factor for Inhibitor Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| GE IN Cell 1000 Analyzer (Imager) | 280 | 1.0x (reference) | 0.41 |

| PerkinElmer EnVision (Plate Reader) | 560 | 2.0x less sensitive | 0.16 |

| Beckman Coulter DTX (Plate Reader) | 2,250 | 8.0x less sensitive | Not reported |

The imaging system (IN Cell 1000) demonstrated superior consistency, sensitivity, and dynamic range throughout the detection range compared to plate readers [30]. This enhanced performance directly impacted screening outcomes: during primary screening of 10,000 compounds for VCAM-1 inhibitors, the imager identified the highest percentage of confirmed hits, with the EnVision and DTX plate readers mutually identifying only approximately 57% and 21%, respectively, of the inhibitors visually confirmed in the IN Cell best 1% [30].

Application-Specific Performance: Fluorescence Polarization for Methyltransferase Assays

Fluorescence polarization (FP) exemplifies how specialized detection modes enable specific reaction monitoring applications. A competitive FP immunoassay developed for methyltransferase activity detection demonstrates excellent performance characteristics [31]:

- Detection Limit: ~5 nM (0.15 pmol) S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHcy) in the presence of 3 μM S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)

- Specificity: Antibody showed >150-fold preference for binding AdoHcy relative to AdoMet

- Assay Performance: Successfully monitored catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) activity in a time- and enzyme concentration-dependent manner

- Inhibition Studies: Generated IC50 values consistent with published data for known COMT inhibitors

This homogeneous (mix-and-measure) FP assay requires only the reaction mixture, fluoresceinated AdoHcy tracer, anti-AdoHcy antibody, and a fluorometer capable of measuring FP, making it suitable for high-throughput screening of methyltransferase inhibitors [31].

Advanced Applications in Reaction Monitoring

Fluorescence-Based Activity Assay for Arginase-1

A high-throughput fluorescence assay for arginase-1 demonstrates how innovative reagent design enhances reaction monitoring. This homogeneous assay measures the conversion of L-arginine to L-ornithine by a decrease in fluorescent signal due to quenching of a fluorescent probe, Arginase Gold [32]. Key advantages include:

- Homogeneous Format: "Mix-and-measure" protocol without separation steps

- Inhibition Profiling: Reference inhibitors showed similar potencies and rank order compared to traditional colorimetric urea formation assays

- High-Throughput Compatibility: Successful automation in 384-well format with good Z'-factor and hit confirmation rate

- Binding Kinetics: Capability to study inhibitor binding kinetics

The assay's performance in small-molecule library screening confirms its utility for drug discovery applications targeting arginase-1 in cancer immunotherapy [32].

Microbial Phenotypic Screening Using Fluorescent Biosensors

Microplate readers enable versatile analyses of fluorescent biosensor signals from microbial colonies on agar plates, facilitating phenotypic screenings. This approach offers several advantages over traditional imaging systems [33]:

- Enhanced Sensitivity: Improved signal-to-noise ratio for detecting fluorescent protein expression

- Flexibility: Monochromators allow adaptation to different fluorescent proteins without changing hardware

- Ratiometric Capability: Accurate measurement of ratiometric biosensors for parameters like internal pH and redox states

- Standardization: Position-based reading eliminates shadow effects and variations in colony location

In comparative studies, microplate reader analysis of LacI-controlled mCherry expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum colonies showed improved sensitivity and dynamic range compared to imaging approaches [33]. Similarly, the system successfully monitored redox states in microbial colonies using the ratiometric biosensor Mrx1-roGFP2, demonstrating its utility for metabolic engineering and systems biology applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Plate Reader-Based Reaction Monitoring

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reaction Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Tracers | Fluorescein-AdoHcy conjugate [31] | Competes with reaction product for antibody binding in FP assays |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-AdoHcy antibody [31] | Binds to reaction product, enabling FP signal detection |

| Enzyme Substrates | p-Nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) [28] | Chromogenic substrate hydrolyzed to colored product for absorbance detection |

| Specialized Reporters | Arginase Gold probe [32] | Fluorescent probe quenched by reaction progress |

| Fluorescent Proteins | eGFP, mCherry, Mrx1-roGFP2 [34] [33] | Reporters for gene expression, localization, and metabolic states |

| Cellular Viability Indicators | Resazurin, alamarBlue [29] | Converted to fluorescent products by metabolically active cells |

| Luciferase Assay Systems | CellTiter-Glo, ATP Determination Kit [29] | Generate luminescent signals proportional to ATP concentration or cell viability |

| Protein Quantitation Reagents | BCA, Bradford, NanoOrange assays [29] [35] | Generate colorimetric or fluorescent signals proportional to protein concentration |

The following diagram illustrates how these research tools integrate into a workflow for parallelized reaction monitoring and data analysis:

Microplate readers provide versatile platforms for parallelized reaction monitoring, with technology selection significantly impacting data quality and experimental outcomes. For multiple turnover experiments validating catalytic activity, kinetic measurement capabilities prove essential for capturing accurate reaction rates and enzyme parameters. While traditional plate readers offer robust performance for many applications, advanced imaging systems demonstrate superior sensitivity in direct comparisons, particularly for cellular assays [30].

The continuing evolution of detection technologies and specialized reagents expands the possibilities for reaction monitoring in drug discovery and enzymology research. From fluorescence polarization assays enabling homogeneous methyltransferase screening [31] to innovative fluorescence quenching assays for arginase-1 [32], these advancements provide researchers with powerful tools for characterizing catalytic activity. As microplate reader technologies continue to converge with imaging capabilities [33], the future of parallelized reaction monitoring promises even greater sensitivity, flexibility, and information content for validating catalytic mechanisms and inhibitor properties.

Quantifying enzyme kinetics is fundamental to understanding cellular metabolism, optimizing biosynthetic pathways, and developing new therapeutics. The catalytic turnover number (kcat) and the Michaelis constant (Km) are pivotal kinetic parameters, describing an enzyme's maximum conversion rate and its substrate affinity, respectively. Their accurate determination through multiple turnover experiments is essential for validating catalytic activity. However, experimental kinetic parameter determination is often a time-consuming and low-throughput process, creating a bottleneck in research and development. The rise of deep learning offers a transformative solution. This guide provides an objective comparison of two advanced deep learning frameworks: CataPro and TurNuP. Both models aim to predict enzyme kinetic parameters with high accuracy and robust generalization, addressing a critical need in the fields of enzymology and drug discovery.

Model Architectures and Core Methodologies

CataPro: A Unified Framework for Multiple Kinetic Parameters

CataPro is a deep learning framework designed for the simultaneous prediction of kcat, Km, and the catalytic efficiency kcat/Km [36]. Its architecture is engineered to prevent overfitting and enhance generalization to novel enzyme sequences.

- Enzyme Representation: CataPro utilizes ProtT5-XL-UniRef50 (ProtT5), a protein language model, to convert an enzyme's amino acid sequence into a 1024-dimensional numerical vector that encapsulates evolutionary and structural information [36].

- Substrate Representation: It employs a dual representation for substrates, combining MolT5 embeddings (a molecular language model) with MACCS keys (a structural fingerprint), resulting in a 935-dimensional feature vector [36].

- Feature Integration and Prediction: The enzyme and substrate vectors are concatenated into a single 1959-dimensional input, which is then processed by a neural network to predict the final kinetic parameters [36].

TurNuP: A Specialized Predictor for Turnover Numbers

TurNuP is a machine and deep learning model specifically developed for the prediction of kcat values for natural reactions of wild-type enzymes [37]. Its design emphasizes generalizability to enzymes with low similarity to those in the training set.

- Reaction Representation: A key innovation of TurNuP is its use of Differential Reaction Fingerprints (DRFPs). This representation captures the complete chemical transformation by encoding the differences between substrate and product structures into a 2048-dimensional binary fingerprint [37].

- Enzyme Representation: The model uses embeddings from a modified and fine-tuned Transformer network to represent the enzyme sequence [37].

- Prediction Engine: Unlike CataPro's neural network, TurNuP uses a gradient-boosting model (an ensemble of decision trees) to make the final kcat prediction from the combined reaction and enzyme features [37] [38].

Table 1: Core Architectural Differences Between CataPro and TurNuP

| Feature | CataPro | TurNuP |

|---|---|---|

| Predicted Parameters | kcat, Km, kcat/Km [36] | kcat [37] |

| Enzyme Feature Extraction | ProtT5 protein language model [36] | Fine-tuned Transformer network [37] |

| Substrate/Reaction Representation | MolT5 embeddings + MACCS keys (substrate-only) [36] | Differential Reaction Fingerprints (full reaction) [37] |

| Core Prediction Model | Neural Network [36] | Gradient Boosting (e.g., XGBoost) [37] [38] |

Workflow Comparison

The following diagrams illustrate the distinct prediction workflows for CataPro and TurNuP, highlighting their different approaches to feature extraction and modeling.

CataPro Prediction Workflow: Integrates separate enzyme and substrate representations.

TurNuP Prediction Workflow: Uses full reaction fingerprints and a gradient boosting model.

Performance and Experimental Validation

Benchmarking on Unbiased Datasets

A critical challenge in developing predictive models for biology is generalization to sequences not seen during training. To ensure a fair evaluation, CataPro introduced unbiased benchmarking datasets for kcat, Km, and kcat/Km. These datasets were constructed using sequence-similarity clustering (40% identity threshold) to ensure that enzymes in the test sets are distinct from those in the training sets [36]. This prevents models from achieving high scores by simply memorizing similarities.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Unbiased Test Sets

| Model | Prediction Task | Key Performance Advantage | Generalization Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| CataPro | kcat, Km, kcat/Km | Clearly enhanced accuracy and generalization on unbiased datasets [36]. | Robust prediction for enzymes with low sequence similarity to training data [36]. |

| TurNuP | kcat | Outperforms previous models (e.g., DLKcat) and generalizes well to enzymes with <40% sequence identity to training [37]. | Makes meaningful predictions for enzymes with 0-40% sequence identity, where other models fail [38]. |