Unlocking Materials Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to High-Throughput Experimental Databases

This article explores High-Throughput Experimental Materials (HTEM) Databases, powerful resources transforming materials science by providing large-scale, publicly accessible experimental data.

Unlocking Materials Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to High-Throughput Experimental Databases

Abstract

This article explores High-Throughput Experimental Materials (HTEM) Databases, powerful resources transforming materials science by providing large-scale, publicly accessible experimental data. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we examine foundational concepts behind platforms like NREL's HTEM DB, which houses over 140,000 inorganic thin-film samples. The guide covers practical methodologies for data access via web interfaces and APIs, addresses common challenges in data veracity and standardization, and validates these resources through their integration with computational efforts and real-world research impact, ultimately demonstrating their critical role in accelerating materials-driven innovation.

What is a High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database? Unveiling the Foundation of Data-Driven Discovery

Defining HTEM Databases and Their Core Mission in Modern Materials Science

High-Throughput Experimental Materials (HTEM) Databases represent a transformative paradigm in materials science research, enabling the accelerated discovery and development of novel materials through systematic data aggregation and dissemination. The core mission of the High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB) is to enable discovery of new materials with useful properties by releasing large amounts of high-quality experimental data to the public [1]. This infrastructure addresses a critical bottleneck in materials innovation by providing researchers with comprehensive datasets that bridge the gap between experimental investigation and data-driven discovery.

Unlike computational databases that contain predicted material properties, HTEM databases specialize in housing experimental data obtained from combinatorial investigations at research institutions [2]. These databases serve as endpoints for integrated research workflows, capturing the complete experimental context including material synthesis conditions, chemical composition, structure, and properties in a structured, accessible format [2]. The fundamental value proposition of HTEM databases lies in their ability to transform isolated experimental results into interconnected, searchable knowledge assets that can power machine learning approaches and accelerate materials innovation across multiple domains, including energy, computing, and security technologies [2].

Architectural Framework and Data Infrastructure

Research Data Infrastructure (RDI) Components

The HTEM database ecosystem is enabled by a sophisticated Research Data Infrastructure (RDI) that manages the complete data lifecycle from experimental generation to public dissemination. This infrastructure consists of several interconnected components that work in concert to ensure data fidelity, accessibility, and utility [2].

The Data Warehouse forms the foundational layer of this infrastructure, employing specialized harvesting software that monitors instrument computers and automatically identifies target files as they are created or updated. This system archives nearly 4 million files harvested from more than 70 instruments across 14 laboratories, demonstrating scalability well beyond combinatorial thin-film research [2]. The warehouse utilizes a PostgreSQL back-end relational database for robust data management [2].

Critical metadata from synthesis, processing, and measurement steps are captured using a Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC), which preserves essential experimental context for subsequent interpretation [2]. The Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) scripts then process this raw data into structured formats optimized for analysis and machine learning applications. The entire system operates on a specialized Research Data Network (RDN), a firewall-isolated sub-network that protects sensitive research instrumentation while enabling secure data transfer [2].

Data Flow and Integration Workflow

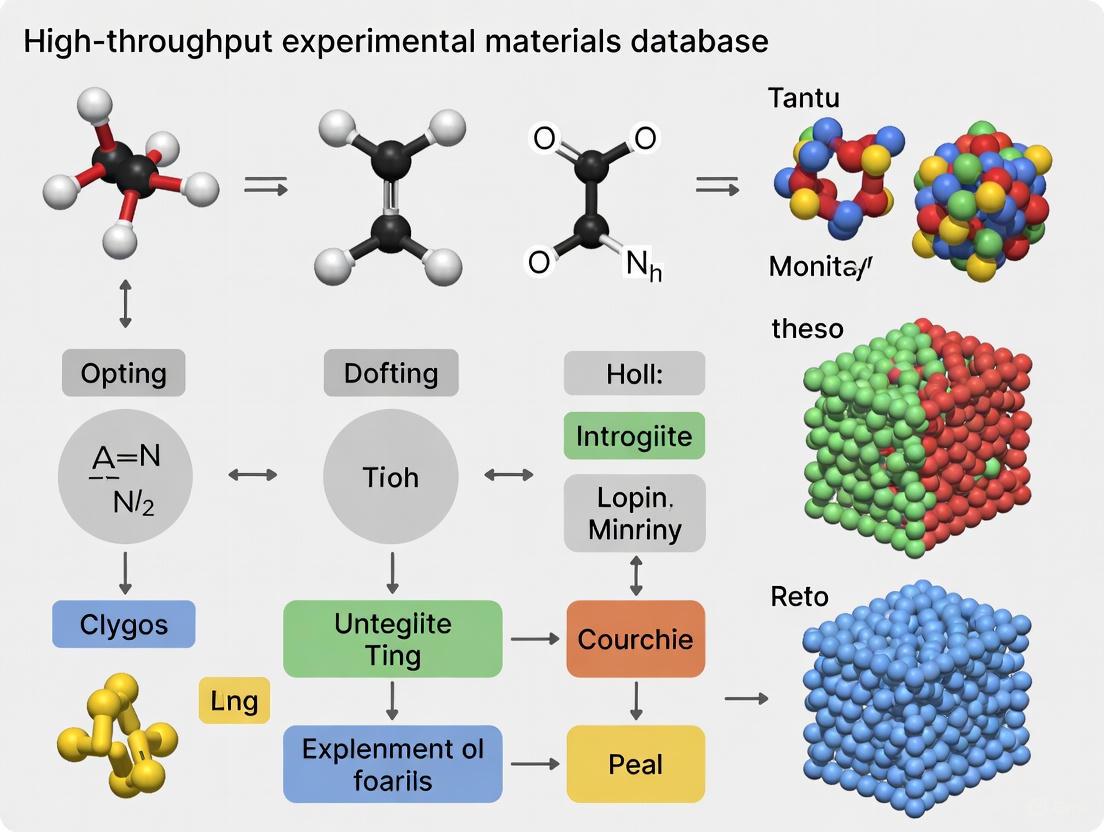

The HTEM data flow follows a structured pipeline that transforms raw experimental measurements into curated, publicly accessible knowledge. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow:

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials

The HTEM database development relies on specialized materials and computational tools that enable high-throughput experimentation and data processing. The following table details these essential components:

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in HTEM Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Thin-Film Materials | Inorganic oxides [2], nitrides [2], chalcogenides [2], Li-containing materials [2] | Serve as primary research targets for combinatorial deposition and characterization |

| Substrate Platforms | 50×50 mm square substrates with 4×11 sample mapping grid [2] | Standardized platform for parallel sample preparation and analysis across multiple instruments |

| Software Tools | COMBIgor [2], Python API [3], Custom ETL scripts [2] | Data analysis, instrument control, and data processing pipeline management |

| Characterization Instruments | Gradient temperature furnace [3], Scanning electron microscope [3], Nanoindenter [3] | Automated measurement of microstructure and mechanical properties |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

High-Throughput Thin-Film Synthesis and Characterization

The experimental foundation of HTEM databases relies on standardized protocols for parallel materials synthesis and characterization. The combinatorial thin-film deposition process utilizes 50 × 50-mm square substrates with a standardized 4 × 11 sample mapping grid that ensures consistency across multiple deposition chambers and characterization instruments [2]. This standardized format enables direct comparison of results across different experimental campaigns and instrument platforms.

Material libraries are created through combinatorial deposition techniques that compositionally grade materials across the substrate surface, allowing a single experiment to explore dozens of compositional variations [2]. Following deposition, materials undergo comprehensive characterization using spatially resolved techniques including X-ray diffraction for structural analysis, electron microscopy for microstructural examination, and various spectroscopic methods for compositional mapping [2]. This integrated approach generates interconnected datasets that capture the relationships between synthesis conditions, composition, structure, and properties.

Automated High-Throughput Data Generation Protocol

Recent advancements have dramatically accelerated the experimental data generation process through complete automation. The National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS) has developed an automated high-throughput system that generates Process-Structure-Property datasets from a single sample of Ni-Co-based superalloy used in aircraft engine turbine disks [3]. The methodology follows this precise protocol:

Gradient Thermal Processing: The superalloy sample is thermally treated using a specialized gradient temperature furnace that maps a wide range of processing temperatures across a single sample [3].

Automated Microstructural Analysis: Precipitate parameters and microstructural information are collected at various coordinates along the temperature gradient using a scanning electron microscope automatically controlled via a Python API [3].

High-Throughput Property Mapping: Mechanical properties, particularly yield stress, are measured using a nanoindenter system that automatically tests multiple locations corresponding to different thermal histories [3].

Integrated Data Processing: The system automatically processes and correlates the collected data, generating unified records that link processing conditions, microstructural features, and resulting properties [3].

This automated approach has demonstrated remarkable efficiency, producing a volume of Process-Structure-Property data that would require approximately seven years and three months using conventional methods in just 13 days – representing a 200-fold acceleration in data generation [3].

Quantitative Impact and Performance Metrics

Data Generation Efficiency and Throughput

The implementation of high-throughput methodologies and automated systems has dramatically improved the efficiency of experimental materials data generation. The following table quantifies these performance improvements:

| Methodology | Data Generation Rate | Time Required for 1,000 Data Points | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Manual Methods | Baseline reference | ~2.5 years [3] | Requires individual sample preparation, processing, and characterization |

| Early HTE Combinatorial Approaches | Moderate improvement over conventional | ~6 months [2] | Standardized substrate formats; parallel characterization |

| NIMS Automated System (2025) | ~200× acceleration [3] | 13 days [3] | Single-sample gradient processing; fully automated characterization |

HTEM Database Scope and Coverage

The scale and diversity of materials data contained within HTEM databases directly impacts their utility for machine learning and materials discovery initiatives. The following table summarizes the quantitative scope of existing HTEM resources:

| Database Metric | HTEM-DB (NREL) | NIMS Automated System |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Materials Focus | Inorganic thin-films: oxides, nitrides, chalcogenides, Li-containing materials [2] | Ni-Co-based superalloys for high-temperature applications [3] |

| Data Types Included | Synthesis conditions, composition, structure, optoelectronic/electronic properties [2] | Processing conditions, microstructure parameters, yield strength [3] |

| Instrument Integration | 70+ instruments across 14 laboratories [2] | Gradient furnace, SEM with Python API, nanoindenter [3] |

| Throughput Capacity | Continuous data stream from ongoing experiments [2] | Several thousand records in 13 days [3] |

Integration with Data Science and Machine Learning

Data Standardization and Machine Learning Readiness

A core mission of HTEM databases is to provide machine learning-ready datasets that satisfy the volume, quality, and diversity requirements for effective algorithm training [2]. The RDI ensures this through rigorous data standardization protocols including uniform file naming conventions, structured metadata capture using the Laboratory Metadata Collector, and automated data validation procedures [2]. This standardized approach enables direct integration with popular machine learning frameworks and data science workflows.

The HTEM database architecture specifically addresses the data needs of both experimental materials researchers and data science professionals by providing multiple access modalities, including an interactive web interface for exploratory analysis and a programmatic API for bulk data download and integration into automated analysis pipelines [1]. This dual-access approach ensures that the data remains accessible to domain experts while simultaneously meeting the technical requirements of data scientists developing next-generation materials informatics tools.

Impact on Materials Discovery and Development

The availability of large-scale, high-quality experimental materials data through HTEM databases has fundamentally altered the pace and approach of materials research. By providing comprehensive datasets that capture complex relationships between processing parameters, microstructure, and properties, these resources enable data-driven materials design strategies that can significantly reduce development timelines [3]. The integration of HTEM data with machine learning approaches has demonstrated particular promise for identifying composition-property relationships that might otherwise remain undiscovered through conventional research methodologies.

The broader impact of HTEM databases extends beyond immediate materials discovery to the advancement of fundamental materials knowledge. The systematic organization of experimental data facilitates the identification of knowledge gaps in materials systems, guides the design of targeted experimental campaigns, and provides validation datasets for computational materials models [2]. This creates a virtuous cycle wherein each new experimental result enhances the predictive capability of data-driven models, which in turn guide more efficient experimental planning – ultimately accelerating the entire materials innovation pipeline.

The application of machine learning (ML) promises to revolutionize materials discovery by enabling the prediction of new materials with tailored properties. However, a significant bottleneck threatens to stall this progress: the critical lack of large, diverse, and high-quality experimental datasets suitable for training ML algorithms [4]. While computational materials science has benefited from extensive databases containing millions of simulated material properties, experimental materials science has historically been constrained by a data desert, limiting ML to relatively small, complex datasets such as collections of X-ray diffraction patterns or microscopy images [4]. This disparity creates a "data gap" – a shortfall in the volume, diversity, and accessibility of experimental data compared to computational data. The High-Throughput Experimental Materials (HTEM) Database, developed at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), is designed specifically to bridge this gap. By providing a large-scale, publicly accessible repository of high-quality experimental data, the HTEM Database addresses this critical shortfall, thereby unlocking the potential of machine learning to accelerate experimental materials discovery [2] [4].

The Nature of the Data Gap: Computational Abundance vs. Experimental Scarcity

The divergence between computational and experimental data availability is both quantitative and qualitative. High-throughput ab initio calculations have produced databases such as the Materials Project, AFLOWLIB, and the Open Quantum Materials Database, which collectively contain data on millions of inorganic compounds [5] [6]. These resources provide a fertile ground for ML-driven in-silico material discovery. In stark contrast, the most prominent experimental datasets, such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), while containing hundreds of thousands of entries, are often limited to composition and structural information, lacking the diversity of properties and, most critically, the synthesis and processing conditions required to actually create the materials [4].

This data gap has tangible consequences for machine learning. Effective ML models, particularly complex deep learning algorithms, require large volumes of data to learn underlying patterns without overfitting. They also require comprehensive feature sets—including synthesis parameters, processing conditions, and multiple property measurements—to build robust structure-property relationships [5] [7]. Furthermore, the historical bias in scientific literature towards publishing only "positive" or successful results creates a skewed dataset for ML training, as many algorithms require both positive and negative examples to learn effectively [4]. The scarcity of this type of data in the public domain has been a major impediment to the application of ML in experimental research.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Materials Databases Highlighting the Experimental Data Gap

| Database Name | Type | Number of Entries | Key Data Contained | Primary Limitation for ML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFLOWLIB [5] | Computational | ~3.2 million compounds | Calculated structural and thermodynamic properties | Lacks experimental validation and synthesis data |

| Materials Project [5] | Computational | >530,000 materials | Computed properties of inorganic compounds | No experimental synthesis information |

| ICSD [4] | Experimental | ~100,000s | Crystallographic data from literature | Limited to structure/composition; lacks synthesis & diverse properties |

| HTEM-DB [4] | Experimental | ~140,000 samples (as of 2018) | Synthesis conditions, composition, structure, optoelectronic properties | Focused on inorganic thin-films; other material classes absent |

The HTEM Database Solution: A New Paradigm for Experimental Data

Core Architecture and Data Generation

The High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB, htem.nrel.gov) is a repository for inorganic thin-film materials data generated from combinatorial experiments at NREL [2]. Its creation was motivated by the need to aggregate valuable data from existing experimental streams to increase their usefulness for future machine learning studies [2]. The database's architecture is built upon a custom Research Data Infrastructure (RDI), a set of data tools that automate the flow of data from laboratory instruments to a publicly accessible database.

The experimental workflow underpinning the HTEM-DB involves synthesizing thin-film sample libraries using combinatorial physical vapor deposition (PVD) methods on substrates with standardized mapping grids [2] [4]. Each sample library is then characterized using spatially-resolved techniques to obtain data on structural, chemical, and optoelectronic properties. This high-throughput approach allows for the rapid generation of large, comprehensive datasets that are systematically organized and fed into the database [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Content of the HTEM Database (as of 2018) [4]

| Data Category | Number of Entries/Samples | Specific Measurements and Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Sample Entries | 141,574 | Grouped in 4,356 sample libraries across ~100 materials systems |

| Structural Data | 100,848 | X-ray diffraction patterns |

| Synthetic Data | 83,600 | Synthesis conditions (e.g., temperature) |

| Chemical & Morphological Data | 72,952 | Composition and thickness |

| Optoelectronic Data | 55,352 | Optical absorption spectra |

| Electronic Data | 32,912 | Electrical conductivity |

The Research Data Infrastructure: Engine of Automation

The RDI is the technological backbone that enables the HTEM-DB to overcome the traditional limitations of manual data curation. It functions as an integrated laboratory information management system (LIMS) with several key components [2] [4]:

- Automated Data Harvesting: Software tools, known as "data harvesters," monitor computers controlling experimental instruments. They automatically identify and copy relevant data files as they are created, transferring them to a centralized Data Warehouse (DW) via a specialized Research Data Network (RDN) [2].

- Data Warehouse: The DW is a massive archive, housing nearly 4 million files harvested from more than 70 instruments across NREL. It uses a relational database (PostgreSQL) to manage the stored data and metadata [2].

- Metadata Collection: The Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC) tool is used to capture critical experimental context (metadata) for synthesis, processing, and measurement steps, which is added to the DW or directly to the HTEM-DB [2].

- Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) Process: Custom scripts process the raw data and metadata from the DW, aligning synthesis and characterization data into the structured, object-relational architecture of the HTEM-DB [2] [4].

- Access Interfaces: The processed data is made accessible through a web-based user interface (htem.nrel.gov) for interactive exploration and an Application Programming Interface (API) for programmatic access by data scientists and for machine learning applications [4] [1].

Methodologies: From Laboratory Synthesis to Machine Learning

High-Throughput Experimental Protocols

The data within the HTEM-DB is generated through a rigorous, multi-step high-throughput experimental (HTE) protocol. The following methodology is representative of the workflows used to populate the database [2] [4]:

Combinatorial Materials Synthesis:

- Objective: To create libraries of inorganic thin-film samples with varied compositions on a single substrate.

- Protocol: Utilizes combinatorial physical vapor deposition (PVD) methods, such as sputtering or pulsed laser deposition, in specialized chambers. A common substrate size is a 50 x 50-mm (2 x 2-inch) square with a predefined 4 x 11 sample mapping grid. By controlling the position of substrates relative to multiple deposition sources and varying parameters like power, pressure, and gas flows, a single library can contain dozens of unique material compositions and structures [2] [4].

- Metadata Capture: Critical synthesis parameters, including substrate temperature, deposition pressure, gas flows, target powers, and deposition time, are recorded using the Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC) and associated with each sample position [2].

Spatially-Resolved Materials Characterization:

- Objective: To measure the chemical, structural, and functional properties of each sample on the library.

- Protocol: A suite of characterization techniques is employed, with measurements mapped to the predefined grid.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): For determining crystal structure and phase. Provides patterns for over 100,000 samples in the database [4].

- X-ray Fluorescence (XRF): For determining chemical composition and thickness. Data for over 70,000 samples [4].

- Optical Spectroscopy: For measuring absorption spectra and deriving optoelectronic properties like band gap. Data for over 55,000 samples [4].

- Electrical Measurements: For determining properties like electrical conductivity. Data for over 32,000 samples [4].

Data Preprocessing and Machine Learning Protocols

Once data is ingested into the HTEM-DB via the RDI, it becomes available for machine learning. The standard ML workflow involves several key steps [5] [7]:

Data Collection and Cleaning:

- Data is accessed via the HTEM-DB API, which allows for programmatic extraction of large datasets for analysis.

- The collected data may undergo cleaning, which includes handling of missing values, eliminating abnormal values, and data normalization to adjust the magnitudes of different features to a comparable scale, which is crucial for many ML algorithms [5].

Feature Engineering:

- This process involves selecting and constructing the most relevant descriptors (features) from the raw data. For materials data, this can include elemental properties, structural descriptors, and synthesis parameters.

- Automated feature engineering is an emerging trend that uses deep learning to automatically develop a relevant set of features, minimizing the need for domain knowledge [5].

Model Training and Validation:

- The cleaned and featurized dataset is split into training and testing sets.

- A suitable ML algorithm (e.g., Random Forest, Neural Networks, Support Vector Machines) is selected and trained on the training set to learn the relationship between the input features and the target property (e.g., band gap, conductivity) [5] [7].

- The model's performance is then validated using the testing set through cross-validation procedures to ensure its predictive accuracy and generalizability [5].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Tools for HTEM and ML-Driven Discovery

| Item / Resource | Type | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial PVD System | Instrument | High-throughput synthesis of thin-film sample libraries with compositional spreads. |

| Spatially-Resolved XRD | Instrument | Automated structural characterization mapped to sample library grids. |

| Data Harvester Software | Data Tool | Automatically identifies and archives raw data files from instrument computers to the Data Warehouse. |

| Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC) | Data Tool | Captures critical experimental context (e.g., synthesis conditions) that gives meaning to the raw measurements. |

| COMBIgor | Software | Open-source data-analysis package for loading, aggregating, and visualizing high-throughput combinatorial materials data [2]. |

| HTEM-DB API | Data Tool | Provides programmatic access to the entire public dataset, enabling large-scale data extraction for machine learning pipelines [4] [1]. |

| Standardized Substrate Grids | Lab Consumable | Provides a common physical framework for sample libraries, ensuring data from different instruments can be spatially correlated. |

The critical data gap between computational prediction and experimental realization has long been a roadblock to the full realization of machine learning's potential in materials science. The HTEM Database, powered by its robust Research Data Infrastructure, presents a concrete and scalable solution to this problem. By automating the collection and curation of large-scale, diverse, and high-quality experimental datasets—complete with the essential synthesis and processing metadata—it provides the fertile ground required for advanced ML algorithms to thrive. This resource not only enables classical correlative machine learning for property prediction but also opens a pathway for the exploration of underlying causative physical behaviors [2] [6]. As the volume and diversity of data within the HTEM-DB and similar resources continue to grow, they will collectively accelerate the pace of discovery and design in experimental materials science, ultimately fueling innovation across energy, computing, and other critical technology domains.

The High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM DB) represents a transformative approach to materials science research, enabling the accelerated discovery of new materials with useful properties by making large amounts of high-quality experimental data publicly available [1] [8]. Developed and maintained by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), this database embodies the principles of open data science and serves as a critical resource for researchers investigating material mechanisms, formulating theories, constructing models, and performing machine learning [9]. The mission of the HTEM DB aligns with broader federal initiatives to make federally funded research data publicly accessible, supporting the U.S. Department of Energy's commitment to advancing materials innovation [10].

This database addresses a fundamental challenge in materials science: the traditional time and resource investment required to develop comprehensive experimental datasets. Conventional methods for generating Process-Structure-Property datasets often require years of continuous experimental work, creating a significant bottleneck in materials development [3]. The HTEM DB, in contrast, leverages automated high-throughput experimental approaches and a sophisticated Research Data Infrastructure to aggregate and disseminate valuable materials data, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery across the scientific community [9].

HTEM DB Architecture and Data Infrastructure

Core Database Components

The HTEM DB is built upon a sophisticated Research Data Infrastructure (RDI) comprising custom data tools that systematically collect, process, and store experimental data and metadata [9]. This infrastructure establishes a seamless data communication pipeline between experimental and data science communities, transforming raw experimental measurements into structured, accessible knowledge. The database specifically contains information about materials obtained from high-throughput experiments conducted at NREL, focusing primarily on inorganic thin-film materials synthesized through combinatorial approaches [9].

The technological architecture of HTEM DB provides multiple access pathways tailored to different user needs and expertise levels:

Table: HTEM DB Access Platforms and Capabilities

| Platform | Access Method | Primary Functionality | Target Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTEM DB Website | Interactive web interface | Data exploration, visualization, and download | Experimental researchers, materials scientists |

| HTEM DB API | Programmatic interface (RESTful API) | Automated data retrieval, integration with analysis workflows | Data scientists, computational researchers |

| GitHub Repository | Jupyter notebooks with example code | Demonstration of API functionality, advanced statistical analysis | Developers, advanced users |

The API-driven approach is particularly significant, as it enables programmatic data access and integration with modern data analysis ecosystems. NREL provides comprehensive examples of API usage through a dedicated GitHub repository containing Jupyter notebooks that demonstrate how to interact with the database programmatically [11]. These resources lower the barrier to entry for researchers seeking to incorporate HTEM DB data into their computational workflows and analysis pipelines.

Data Workflow and Processing

The journey of experimental data through the HTEM DB infrastructure follows a systematic workflow that ensures data quality, consistency, and usability. The RDI serves as the foundational framework that orchestrates this flow from instrument to database, implementing critical data management practices throughout the pipeline [9].

The following diagram illustrates the complete data workflow within the HTEM DB ecosystem:

This workflow transforms raw experimental measurements into structured, analysis-ready data through multiple stages of processing and validation. The process begins with automated data collection from various experimental instruments, including combinatorial synthesis systems, characterization tools, and measurement devices [9]. The data then passes through the Research Data Infrastructure, where it undergoes formatting, validation, and enrichment with appropriate metadata. Finally, the processed data is stored in the HTEM DB and made accessible through both interactive web interfaces and programmatic APIs [1] [11].

Data Content and Experimental Methodologies

Measurement Types and Data Characteristics

HTEM DB incorporates comprehensive experimental data obtained through high-throughput methodologies that systematically explore materials composition and processing spaces. The database encompasses multiple characterization techniques that provide complementary information about material properties and performance metrics. Each experimental method follows standardized protocols to ensure data consistency and comparability across different samples and research campaigns.

Table: Primary Experimental Methods in HTEM DB

| Experimental Method | Measured Properties | Experimental Protocol | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystal structure, phase identification | Sample irradiation with X-rays, measurement of diffraction angles | Diffraction patterns, peak positions and intensities [11] |

| X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) | Elemental composition, film thickness | X-ray irradiation, measurement of characteristic fluorescent emissions | Compositional maps, thickness gradients across substrates [11] |

| Four-Point Probe (4PP) | Sheet resistance, conductivity, resistivity | Application of known current, measurement of voltage drop | Resistance maps, conductivity calculations [11] |

| Optical Spectroscopy | Absorption, transmission, reflection | Broadband illumination, spectral response measurement | UV-VIS-NIR spectra, absorption coefficients, Tauc plots [11] |

The combinatorial experimental approach underlying HTEM DB enables the efficient mapping of complex composition-property relationships by creating materials libraries with systematic variations in composition and processing conditions. This methodology generates comprehensive datasets where each data point connects specific processing parameters with resulting structural features and functional properties [3]. The database specifically focuses on inorganic thin-film materials, with particular emphasis on compounds relevant to renewable energy applications, including photovoltaic absorbers, transparent conductors, and other energy-related materials [9].

Research Reagents and Essential Materials

The experimental data within HTEM DB is generated using specialized research equipment and analytical tools that constitute the essential "research reagents" for high-throughput materials investigation. These resources form the technological foundation that enables rapid, automated materials synthesis and characterization.

Table: Essential Research Infrastructure for High-Throughput Materials Science

| Equipment Category | Specific Tools | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Synthesis Systems | Sputtering systems, evaporation tools, chemical vapor deposition | Creation of materials libraries with compositional gradients across substrates [11] |

| Structural Characterization | Scanning electron microscopes, X-ray diffractometers | Analysis of microstructural features, crystal structure determination, phase identification [3] [11] |

| Compositional Analysis | X-ray fluorescence spectrometers, electron microscopes with EDS | Quantitative elemental analysis, composition mapping across materials libraries [11] |

| Functional Properties Measurement | Four-point probes, nanoindenters, spectrophotometers | Assessment of electrical, mechanical, and optical properties [3] [11] |

| Data Acquisition and Control | Python APIs, automated instrument control systems | Orchestration of measurement sequences, data collection, and preliminary processing [3] [11] |

The integration of these tools through automated control systems represents a critical innovation in high-throughput materials science. The Python APIs mentioned in the experimental workflow enable seamless coordination between different instruments, ensuring standardized measurement protocols and direct capture of experimental metadata [3] [11]. This automated infrastructure dramatically accelerates the pace of materials investigation, enabling the generation of datasets that would require years to complete using conventional manual approaches.

Access and Utilization Capabilities

Data Retrieval and Analysis Tools

The HTEM DB provides multiple pathways for data access designed to accommodate users with varying levels of technical expertise and different research objectives. For interactive exploration, the web interface offers visualization tools specifically tailored to different data types, allowing researchers to browse materials data, generate plots, and identify patterns through graphical representations [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for experimental materials scientists who may prefer visual data exploration before committing to detailed analysis.

For programmatic access, the HTEM DB API exposes the complete database through a structured interface that supports complex queries and automated data retrieval [1] [11]. NREL provides comprehensive examples of API usage through a dedicated GitHub repository containing Jupyter notebooks that demonstrate various data access and analysis scenarios:

- Basic Queries: Introduction to Library and Sample modules for querying information at different structural levels [11]

- XRD Analysis: Techniques for plotting X-ray diffraction spectra and implementing basic peak detection algorithms [11]

- XRF Processing: Methods for analyzing X-ray fluorescence data, including composition and thickness mapping across substrates [11]

- Electrical Properties: Approaches for visualizing and analyzing four-point probe measurements of sheet resistance and conductivity [11]

- Optical Characterization: Procedures for working with optical spectra, including absorption coefficient calculations and Tauc plotting for band gap determination [11]

These resources significantly lower the technical barrier for utilizing the database, providing researchers with starting points for their own customized analysis workflows while demonstrating best practices for data manipulation and interpretation.

Impact and Applications

The availability of high-quality, standardized experimental materials data through HTEM DB enables diverse research applications across the materials science community. The database serves as a valuable benchmarking resource for computational materials scientists developing predictive models, providing experimental validation data for first-principles calculations and machine learning approaches [9]. This synergy between computation and experiment accelerates the materials discovery cycle by enabling rapid iteration and validation of theoretical predictions.

The impact of HTEM DB extends beyond immediate materials discovery to the establishment of data standards and best practices for the broader materials science community. The infrastructure and methodologies developed for HTEM DB provide a template for other institutions seeking to implement similar data aggregation workflows, promoting consistency and interoperability across the materials research ecosystem [9]. This standardization is critical for enabling federated data resources that can accelerate materials innovation through collaborative, data-driven approaches.

Emerging Trends and Developments

The field of high-throughput experimental materials science continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping the future development of resources like HTEM DB. Recent advances demonstrate the potential for even greater acceleration of data generation, with one research team developing an automated system that produced a superalloy dataset containing several thousand interconnected records in just 13 days—a task that would have required approximately seven years using conventional methods [3]. This remarkable efficiency gain highlights the transformative potential of fully integrated, automated high-throughput experimentation.

Future developments in HTEM DB and similar resources will likely focus on expanding into new materials classes and property domains. The NIMS research team, for example, plans to apply their automated high-throughput system to construct databases for various target superalloys and to develop new technologies for acquiring high-temperature yield stress and creep data [3]. Similarly, there are ongoing efforts to formulate multi-component phase diagrams based on constructed databases and to explore new materials with desirable properties using data-driven techniques [3]. These directions align with broader materials research priorities, including the development of heat-resistant superalloys that may contribute to achieving carbon neutrality [3].

The High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database represents a pioneering approach to materials research infrastructure that fundamentally transforms how experimental data is collected, shared, and utilized. By implementing a sophisticated Research Data Infrastructure and making comprehensive materials datasets publicly accessible, HTEM DB enables accelerated discovery across the materials science community. The database's multi-faceted access framework, encompassing both interactive web tools and programmatic APIs, ensures that it can effectively serve diverse research needs and expertise levels.

As high-throughput experimental methodologies continue to advance, resources like HTEM DB will play an increasingly critical role in bridging the gap between experimental materials science and data-driven discovery approaches. The continued development and expansion of such databases will be essential for addressing complex materials challenges in energy, transportation, and sustainability applications. By serving as both a repository of valuable experimental data and a model for research data infrastructure, HTEM DB establishes a foundation for the next generation of materials innovation.

In the realm of high-throughput experimental materials database exploration research, the scale and scope of a database are critical determinants of its utility for machine learning and accelerated discovery. Databases housing over 140,000 samples represent a significant data asset, enabling researchers to identify complex patterns and relationships beyond the scope of traditional studies. Framed within a broader thesis on high-throughput experimental materials database exploration, this technical guide examines the infrastructure, data presentation, and experimental protocols necessary to manage and interpret such vast landscapes. The integration of automated data tools with experimental instruments establishes a vital communication pipeline between experimental researchers and data scientists, a necessity for aggregating valuable data and enhancing its usefulness for future machine learning studies [2]. For materials science, and by extension drug development, such resources can greatly accelerate the pace of discovery and design, advancing new technologies in energy, computing, and health [2].

The High-Throughput Experimental Data Infrastructure

The foundation for managing a database of 140,000+ samples is a robust Research Data Infrastructure (RDI). The RDI is a set of custom data tools that collect, process, and store experimental data and metadata, creating a modern data management system comparable to a laboratory information management system (LIMS) [2]. This infrastructure is integrated directly into the laboratory workflow, cataloging data from high-throughput experiments (HTEs). The primary function of the RDI is to automate the curation of experimental materials data, which involves collecting not only the final results but also the complete experimental dataset, including material synthesis conditions, chemical composition, structure, and properties [2]. This comprehensive approach to data collection ensures enhanced total data value and provides the high-quality, large-volume datasets that machine learning algorithms require to make significant contributions to scientific domains [2].

Structural Pillars of the Research Data Infrastructure

The RDI comprises several interconnected components that facilitate the seamless flow of data from instrumentation to an accessible database. The key structural pillars include:

- Data Harvesters and the Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC): These tools are responsible for the initial data and metadata acquisition. Harvesters automatically identify and copy relevant digital files generated during materials growth and characterization from instrument computers. The LMC critically collects contextual metadata from synthesis, processing, and measurement steps, providing essential experimental context for the measurement results [2].

- Data Warehouse (DW): The DW serves as the central archive for the digital files harvested from laboratory instruments. It typically consists of a back-end relational database and a filesystem, housing millions of files from dozens of instruments across multiple laboratories. To protect sensitive research instrumentation, computers are connected to the data harvester and archives via a firewall-isolated, specialized sub-network, such as a Research Data Network (RDN) [2].

- Extract, Transform, and Load (ETL) Scripts: This component processes the raw data from the DW. ETL scripts extract data from the harvested files, transform it into a structured and usable format, and load it into the final database [2].

- The High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB): This is the final repository that stores the processed, analysis-ready data. It is populated by the ETL process from specific high-throughput measurement folders in the DW, which are identified by standardized file-naming conventions. This database provides a public-facing interface for data analysis, publication, and data science purposes [2].

Data Presentation and Quantitative Summaries

Effective data presentation is paramount for interpreting the vast information within a 140,000+ sample database. The choice of presentation method—tables or charts—should be guided by the specific information to be emphasized and the nature of the analysis [12].

Charts vs. Tables: Strategic Use Cases

- Charts are superior for showing trends, patterns, and relationships within the data. They deliver quick visual insights and are ideal for identifying patterns or shapes of data, illustrating the relationship between two or more data sets, and displaying variability [13]. Graphs are highly effective visual tools as they display data at a glance, facilitate comparison, and can reveal trends and relationships within the data such as changes over time, frequency distribution, and correlation [12].

- Tables excel at presenting detailed, exact figures and are best suited for representing individual information. They provide specific numerical values and are less prone to misinterpretation as values are explicit. Tables are the most appropriate when all information requires equal attention, and they allow readers to selectively look at information of their own interest [13] [12]. They are indispensable when the reader needs to look at specific values within the data set or when the precise value is key rather than a trend [13].

The following table summarizes hypothetical quantitative data representative of a large-scale high-throughput experimental materials database, illustrating key metrics and distributions relevant to researchers.

Table 1: Representative Quantitative Summary of a High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database

| Metric | Value | Description / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Total Samples | 140,000+ | Total number of individual material samples in the database. |

| Material Classes | 15+ | e.g., Oxides, Nitrides, Chalcogenides, Li-containing materials, Intermetallics [2]. |

| Properties Measured | 25+ | e.g., Band gap, Electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, Photoelectrochemical activity, Piezoelectric coefficient [2]. |

| Data Points | ~10 Million | Estimated total measurements, including composition, structure, and property data. |

| Deposition Methods | 8+ | e.g., Sputtering, Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD), Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD). |

| Characterization Techniques | 12+ | e.g., X-ray Diffraction (XRD), X-ray Fluorescence (XRF), Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS), 4-point probe. |

| Annual Data Growth | ~15,000 samples/year | Based on ongoing high-throughput experiments. |

For a more intuitive understanding of the distribution of material classes within such a database, a chart is the most effective tool.

Diagram 1: High-throughput experimental and data workflow. This diagram illustrates the integrated pipeline from hypothesis and sample preparation through characterization, automated data harvesting, and storage in a queryable database for analysis.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The value of a large-scale database is contingent on the consistency and rigor of its underlying experimental protocols. The following section details a generalized methodology for a high-throughput combinatorial thin-film materials experiment, from which data for the HTEM-DB is populated [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Combinatorial Thin-Film Synthesis and Characterization

Objective: To create a spatially varied library of inorganic thin-film materials on a single substrate and characterize its composition, structure, and functional properties.

Materials and Substrate:

- Substrate: 50 x 50 mm (2 x 2 inch) square substrate (e.g., glass, silicon, FTO-glass) [2].

- Target Materials: High-purity (typically >99.9%) sputtering targets or evaporation sources for the desired material systems.

- Masking System: Custom physical masks or shutter systems designed to create compositional gradients across the substrate.

Protocol Steps:

Substrate Preparation:

- Clean the substrate sequentially in ultrasonic baths of acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water for 10 minutes each.

- Dry the substrate under a stream of dry nitrogen gas.

- Load the substrate into the deposition chamber.

Combinatorial Deposition:

- Evacuate the deposition chamber to a base pressure of at least 1 x 10⁻⁶ Torr.

- Initiate the deposition process (e.g., RF magnetron sputtering, co-evaporation) according to pre-defined power, pressure, and gas flow conditions for each target/source.

- Utilize the masking system to spatially control the deposition of each material component across the substrate surface, creating a library of discrete or gradient compositions. A common mapping grid is 4 x 11 samples per substrate [2].

- Monitor and record deposition parameters (power, pressure, time, gas flows) for each step via the LMC.

Post-Deposition Processing (if applicable):

- Annealing may be performed in a separate furnace or in-situ under controlled atmosphere (e.g., O₂, N₂, Ar) at specified temperatures and durations.

- Record all processing parameters (temperature, time, atmosphere) via the LMC.

High-Throughput Characterization:

- Compositional Analysis: Use spatially resolved X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) to measure the elemental composition at each pre-defined location on the substrate grid.

- Structural Analysis: Use spatially resolved X-ray Diffraction (XRD) with an automated XY stage to determine the crystal structure and phase at each location.

- Functional Property Screening: Employ automated, spatially resolved measurement systems to assess target properties. For optoelectronic materials, this could include UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy for band gap, and a 4-point probe for sheet resistance.

Data and Metadata Collection:

- All digital files generated by the characterization instruments (XRD, XRF, etc.) are automatically harvested and transferred to the Data Warehouse via the RDN [2].

- Critical metadata from synthesis, processing, and measurement steps are collected using the Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC) and added to the DW or directly to the HTEM-DB [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for High-Throughput Combinatorial Experiments

| Item | Function | Specification / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sputtering Targets | Source material for thin-film deposition. | High-purity (≥99.9%), composition-specific (e.g., In₂O₃, ZnO, HfO₂). |

| High-Purity Gases | Sputtering atmosphere and post-annealing environment. | Argon (Ar, sputtering), Oxygen (O₂, reactive sputtering/annealing), Nitrogen (N₂). |

| Standard Substrates | Support for thin-film growth. | 50x50 mm SiO₂/Si, glass, FTO-glass. Standardization enables cross-instrument compatibility [2]. |

| Calibration Standards | Quantification and validation of characterization tools. | Certified XRF standards, XRD Si standard (NIST). |

| Physical Masks | Creation of compositional gradients or discrete libraries. | Custom-fabricated from stainless steel or silicon. |

| COMBIgor Software | Open-source data-analysis package for high-throughput materials data. | Used for data loading, aggregation, and visualization in combinatorial materials science [2]. |

Visualization and Accessibility Standards

Adhering to strict visualization standards ensures that diagrams and data presentations are clear, accessible, and professionally consistent.

Workflow Visualization with Graphviz

The following Graphviz (DOT language) script generates a detailed diagram of the experimental and data workflow, adhering to the specified color and contrast rules.

Diagram 2: Research data infrastructure pipeline. This diagram details the data flow from raw instrument output to a structured database that enables machine learning and scientific discovery.

Adherence to Color and Contrast Guidelines

All diagrams are generated in compliance with WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) for contrast. The specified color palette (#4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853, #FFFFFF, #F1F3F4, #202124, #5F6368) is used exclusively. The critical rule that the text color (fontcolor) is explicitly set to have high contrast against the node's background color (fillcolor) is followed. For example, dark text (#202124) is used on light backgrounds (#F1F3F4, #FBBC05), and white text (#FFFFFF) is used on dark or vibrant backgrounds (#4285F4, #EA4335, #34A853, #5F6368) [14] [15]. This ensures legibility for all users.

A database encompassing 140,000+ samples, built upon a robust Research Data Infrastructure, represents a transformative asset in high-throughput experimental materials science. The scalability, scope, and depth of such a resource are fundamental to unlocking new, non-intuitive insights through machine learning. The effectiveness of this exploration is heavily dependent on the strategic presentation of data—using tables for precise detail and charts for overarching trends—and the rigorous, consistent application of automated experimental protocols. The creation and maintenance of such integrated data environments are crucial for accelerating the pace of discovery and design, ultimately benefiting the development of new technologies across critical domains including energy, computing, and drug development.

The paradigm of materials discovery has been fundamentally transformed by high-throughput experimental (HTE) methodologies and the databases they populate. These approaches enable the rapid synthesis and characterization of thousands of inorganic thin-film materials, generating comprehensive datasets that are critical for machine learning-driven materials discovery [16]. The High Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB, htem.nrel.gov) exemplifies this infrastructure, containing data on over 140,000 inorganic thin-film samples as of 2018, with continuous expansion through ongoing research at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [16] [2]. This technical guide examines the four cornerstone data types—structural, synthetic, chemical, and optoelectronic properties—within the context of HTE materials databases, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge required to leverage these resources for accelerated materials innovation.

Database Infrastructure and Data Flow Architecture

The research data infrastructure supporting high-throughput experimental materials science establishes an integrated pipeline for experimental and data researchers. This workflow, as implemented at NREL, encompasses both physical experimentation and data curation processes that feed into the HTEM-DB [2].

Research Data Infrastructure Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and data workflow that enables the population of high-throughput experimental materials databases:

This integrated workflow demonstrates how experimental data flows from synthesis and characterization instruments through automated harvesting into a centralized data warehouse, where it undergoes processing before being loaded into the queryable HTEM-DB [16] [2]. The database subsequently enables access through both web interfaces and programmatic APIs, supporting various research activities from manual exploration to machine learning applications.

Core Data Types in High-Throughput Materials Science

High-throughput experimental materials databases capture multifaceted data types that collectively provide a comprehensive picture of material behavior. These core data types enable researchers to establish structure-property relationships essential for materials design and optimization.

Table 1: Core data types and their representation in the HTEM-DB

| Data Category | Specific Properties Measured | Number of Entries | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Properties | Crystal structure, phase identification, lattice parameters | 100,848 | X-ray diffraction (XRD) |

| Synthetic Properties | Deposition temperature, pressure, time, target materials, gas flows | 83,600 | Process parameter logging |

| Chemical Properties | Elemental composition, thickness, stoichiometry | 72,952 | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), thickness mapping |

| Optoelectronic Properties | Optical absorption spectra, electrical conductivity, band gap | 88,264 | UV-Vis spectroscopy, 4-point probe measurements |

The data presented in Table 1 illustrates the comprehensive nature of the HTEM-DB, which as of 2018 contained 141,574 entries of thin-film inorganic materials organized in 4,356 sample libraries across approximately 100 unique materials systems [16]. These materials predominantly consist of compounds including oxides (45%), chalcogenides (30%), nitrides (20%), and intermetallics (5%) [16].

Experimental Methodologies for Data Acquisition

Structural Characterization Protocols

Structural characterization in high-throughput experimental workflows primarily relies on X-ray diffraction (XRD) for crystal structure identification. The standard methodology involves:

Sample Preparation: Thin-film materials are synthesized on 50 × 50-mm square substrates with a standardized 4 × 11 sample mapping grid to maintain consistency across combinatorial deposition chambers and characterization instruments [2].

Data Collection: Automated XRD systems collect diffraction patterns from each sample position using high-throughput sample stages. Typical parameters include Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), voltage of 40 kV, current of 40 mA, and scanning range of 10° to 80° 2θ with a step size of 0.02° [16].

Phase Identification: Collected patterns are compared against reference databases such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) for phase identification and structural analysis [16].

Synthetic Parameter Documentation

Synthetic parameters are systematically recorded during the combinatorial physical vapor deposition (PVD) process using a Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC) [2]. Critical parameters include:

- Deposition Conditions: Substrate temperature (ambient to 800°C), chamber pressure (10⁻⁶ to 10⁻² Torr), deposition time (1-60 minutes)

- Precursor Information: Sputtering target compositions, gas flows (Ar, O₂, N₂), power settings (RF, DC, pulsed DC)

- Post-Deposition Treatments: Annealing temperature and atmosphere, processing time

These parameters are automatically harvested from instrument computers and stored in the data warehouse with standardized file-naming conventions [2].

Chemical Composition Analysis

Chemical characterization employs spatially-resolved techniques to map composition across combinatorial libraries:

Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS): Performed in conjunction with scanning electron microscopy to determine elemental composition at each sample position with typical detection limits of 0.1-1 at%.

Thickness Mapping: Profilometry or spectroscopic ellipsometry measurements at multiple positions across each sample to determine thickness variations.

Data Integration: Composition and thickness data are aligned with synthesis parameters and structural information through the extract-transform-load process [2].

Optoelectronic Property Measurement

Optoelectronic characterization combines optical and electrical measurements:

Optical Absorption Spectroscopy: UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy measures transmission and reflection spectra from 300-1500 nm, enabling Tauc plot analysis for direct and indirect band gap determination [16].

Electrical Characterization: Temperature-dependent Hall effect measurements and four-point probe resistivity mapping provide carrier concentration, mobility, and conductivity data across combinatorial libraries [16].

Data Processing: Custom algorithms in the COMBIgor package (https://www.combigor.com/) process raw measurement data into structured properties for database ingestion [2].

Materials Characterization Workflow

The experimental workflow for high-throughput materials characterization follows a systematic progression from synthesis through multiple characterization stages to data integration.

High-Throughput Materials Characterization Pathway

The following diagram outlines the sequential process for generating comprehensive materials data in high-throughput experiments:

This workflow illustrates the sequential yet integrated approach to materials characterization in high-throughput experimentation. The process begins with combinatorial synthesis using physical vapor deposition techniques, progresses through structural, chemical, and optoelectronic characterization stages, and culminates in data integration and quality assessment before database population [16] [2]. Throughout this workflow, synthetic parameters are recorded as critical metadata that provides essential context for interpreting material properties.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

High-throughput experimental materials research employs specialized reagents, precursors, and substrates to enable combinatorial synthesis and characterization.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for high-throughput experimental materials science

| Material/Reagent | Function | Specific Examples | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sputtering Targets | Precursor sources for thin-film deposition | Metallic targets (Ag, Cu, Zn, Sn), oxide targets (In₂O₃, ZnO), alloy targets | Combinatorial PVD synthesis through co-sputtering |

| Reactive Gases | Atmosphere control during deposition | Oxygen (O₂), nitrogen (N₂), argon (Ar), hydrogen (H₂) | Formation of oxides, nitrides, or controlled atmospheres |

| Substrate Materials | Support for thin-film growth | Glass, silicon wafers, sapphire, flexible polymers | Sample library support with varying thermal and chemical stability |

| Characterization Standards | Instrument calibration | Silicon standard for XRD, certified reference materials for EDS | Quality control and measurement validation |

| Encapsulation Materials | Sample stabilization for testing | UV-curable resins, epoxy coatings, glass coverslips | Protection of air-sensitive materials during optoelectronic testing |

These research reagents enable the synthesis of diverse material systems represented in the HTEM-DB, including oxides (45%), chalcogenides (30%), nitrides (20%), and intermetallics (5%) [16]. The 28 most common metallic elements in the database include Mg, Al, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Zr, Nb, Mo, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag, Cd, Hf, Ta, W, Re, Os, Ir, Pt, Au, and Bi [16].

Data Access and Utilization Strategies

Database Exploration Interfaces

The HTEM-DB provides multiple access modalities tailored to different researcher needs:

Web User Interface (htem.nrel.gov): Offers interactive capabilities for searching, filtering, and visualizing materials data through a periodic-table based search interface with multiple view options (compact, detailed, complete) for sample libraries [16].

Application Programming Interface (htem-api.nrel.gov): Enables programmatic access for large-scale data retrieval compatible with machine learning workflows and custom analysis pipelines [1] [17].

Data Quality Framework: Implements a five-star quality rating system to help users balance data quantity and quality considerations, with three stars indicating uncurated data [16].

Machine Learning Applications

The integration of high-throughput experimental data with machine learning algorithms enables numerous advanced applications:

Materials Discovery: ML models trained on HTEM-DB data can predict new materials with target properties, significantly accelerating the discovery process [16] [18].

Property Prediction: Algorithms can establish relationships between synthesis conditions and resulting material properties, enabling inverse design of processing parameters [18].

Accelerated Optimization: ML-guided experimental design can focus subsequent experiments on the most promising regions of materials composition space [16].

The structured acquisition and management of structural, synthetic, chemical, and optoelectronic properties within high-throughput experimental materials databases represents a transformative advancement in materials research methodology. The HTEM-DB demonstrates how integrated data infrastructure enables both experimental validation and data-driven discovery through standardized workflows, comprehensive characterization protocols, and multifaceted data access strategies. As these databases continue to grow through ongoing experimentation, they provide an increasingly powerful foundation for machine learning applications and accelerated materials innovation. The continued development of similar research data infrastructures across institutions will further enhance the collective ability to address complex materials challenges in energy, electronics, and beyond.

Accessing and Applying HTEM Data: From Interactive Web Tools to Machine Learning Pipelines

The High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB) provides researchers with a powerful web-based interface for exploring inorganic thin-film materials data. This repository, accessible at htem.nrel.gov, contains a vast collection of experimental data generated through combinatorial synthesis and spatially-resolved characterization techniques [19] [2]. As of 2018, the database housed 141,574 sample entries across 4,356 sample libraries, spanning approximately 100 unique materials systems [19]. This guide provides a comprehensive walkthrough of the HTEM-DB web interface, enabling researchers to efficiently navigate this rich experimental dataset for materials discovery and machine learning applications.

The HTEM-DB represents a paradigm shift in experimental materials science by providing large-volume, high-quality datasets amenable to data mining and machine learning algorithms [19] [2]. Unlike computational databases, HTEM-DB contains comprehensive experimental information including synthesis conditions, chemical composition, crystal structure, and optoelectronic properties [2]. The web interface serves as the primary gateway for researchers without access to specialized high-throughput equipment to explore these datasets through intuitive search, filtering, and visualization tools.

The HTEM-DB web interface connects to a sophisticated Research Data Infrastructure (RDI) that automates the flow of experimental data from instruments to the publicly accessible database. This infrastructure includes a Data Warehouse (DW) that archives nearly 4 million files harvested from more than 70 instruments across multiple laboratories [2]. The underlying architecture employs an extract-transform-load (ETL) process that aligns synthesis and characterization data into the HTEM database with object-relational architecture [19].

Table: HTEM Database Content Overview (as of 2018)

| Data Category | Number of Entries | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Total Samples | 141,574 | Inorganic thin-film materials |

| Sample Libraries | 4,356 | Groups of related samples |

| Structural Data | 100,848 | X-ray diffraction patterns |

| Synthetic Data | 83,600 | Synthesis conditions and parameters |

| Composition/Thickness | 72,952 | Chemical composition and physical dimensions |

| Optical Absorption | 55,352 | Optical absorption spectra |

| Electrical Conductivity | 32,912 | Electrical transport properties |

The database's materials coverage is dominated by compounds (45% oxides, 30% chalcogenides, 20% nitrides) with a smaller proportion of intermetallics (5%) [19]. This diverse collection enables researchers to explore structure-property relationships across a broad chemical space, with more than half of the data publicly available through the web interface.

Step-by-Step Navigation Protocol

Begin by navigating to the HTEM-DB web interface at htem.nrel.gov. The landing page presents a clean, research-focused design with primary navigation elements including Search, Filter, and Visualization capabilities. The interface header provides access to general database information through About, Stats, and API sections, which are regularly updated with the latest database statistics and functionality [19].

Before initiating searches, familiarize yourself with the interface layout:

- Periodic Table Search Tool: Central interface element for element selection

- Data Quality Indicators: Five-star rating system for assessing data reliability

- View Options: Toggle between compact, detailed, and complete views of search results

- Sidebar Filters: Dynamic filtering options that appear after initial search

Element-Based Search Procedure

The foundational search mechanism in HTEM-DB employs an interactive periodic table for element selection. Follow this protocol for effective searching:

- Access Search Function: Click on the "Search" tab from the main navigation

- Element Selection: Click on elements of interest in the periodic table display

- Search Logic Selection:

- Choose "all" to find samples containing all selected elements (potentially with additional elements)

- Choose "any" to find samples containing any of the selected elements

- Execute Search: Initiate the search query; results will populate the "Filter" page

The element-centric search approach reflects the materials science context, allowing researchers to explore materials systems based on constituent elements. This method efficiently narrows the vast database to relevant materials systems for further investigation [19].

Results Filtering Methodology

After performing an initial search, the "Filter" page displays matching sample libraries with sophisticated filtering options:

Data Quality Filtering: Use the five-star quality scale to balance data quantity versus quality

- 3-star rating indicates uncurated data requiring careful interpretation

- Higher ratings indicate increasingly vetted and reliable datasets

View Selection:

- Compact View: Displays database sample ID, data quality, measured properties, and included elements

- Detailed View: Adds deposition chamber, sample number, synthesis/measurement dates, and researcher information

- Complete View: Includes all synthesis parameters (targets/power, gasses/flows, substrate/temperature, pressure, time)

Metadata Filtering: Use the sidebar to filter by:

- Synthesis parameters (temperature, pressure, deposition method)

- Characterization techniques (XRD, composition, optoelectronic measurements)

- Date ranges and research projects

- Material system classifications [19]

Table: Data Quality Rating System

| Rating | Interpretation | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| Highest quality, fully curated | Mission-critical analysis | |

| Well-curated with minor issues | Most research applications | |

| Uncurated, automated processing | Exploratory analysis, with verification | |

| Partial data or known issues | Contextual understanding only | |

| Incomplete or problematic | Avoid for quantitative analysis |

Data Visualization and Export

The HTEM-DB interface provides multiple options for data visualization and export:

Interactive Visualization:

- Property-property plotting for identifying correlations

- Composition-structure relationships using specialized visualization tools

- Spatial maps for combinatorial library data

Data Export:

- Download filtered datasets in standardized formats

- API access (

htem-api.nrel.gov) for programmatic data retrieval - Integration with COMBIgor open-source analysis package [2]

Comparative Analysis:

- Side-by-side comparison of multiple samples

- Trend analysis across composition spreads

- Structure-property relationship mapping

Data Exploration Workflow

The data exploration process in HTEM-DB follows a logical workflow from initial query to detailed analysis, as illustrated in the following diagram:

Essential Research Toolkit

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Materials Exploration

| Tool/Resource | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|

| COMBIgor | Open-source data analysis package for loading, aggregating, and visualizing combinatorial materials data | GitHub: NREL/COMBIgor |

| HTEM API | Programmatic access to database content for machine learning and advanced analysis | htem-api.nrel.gov |

| Data Warehouse | Archive of raw experimental files and metadata | Available through RDI system |

| Laboratory Metadata Collector (LMC) | Tool for capturing critical experimental context and synthesis parameters | Integrated into experimental workflow |

Advanced Exploration Techniques

API Integration for Large-Scale Analysis

For research requiring analysis beyond the web interface capabilities, the HTEM API provides programmatic access to the database. The API, accessible at htem-api.nrel.gov, enables:

- Batch downloading of large datasets for machine learning applications

- Custom queries beyond the web interface's predefined filters

- Integration with computational workflows and analysis pipelines

- Automated metadata extraction for systematic literature generation [19]

Integration with Analysis Tools

The HTEM-DB ecosystem supports integration with specialized analysis tools:

COMBIgor Implementation:

- Designed specifically for combinatorial materials science data

- Provides advanced visualization and analysis capabilities

- Open-source and freely available for community use [2]

Machine Learning Ready Datasets:

- Curated datasets for supervised and unsupervised learning

- Pre-processed feature sets for materials property prediction

- Benchmark datasets for algorithm validation [19]

Best Practices for Effective Exploration

To maximize research efficiency when navigating the HTEM-DB web interface:

- Iterative Refinement: Begin with broad searches using the "any" element selector, then progressively narrow using filters

- Data Quality Awareness: Balance data quantity needs with quality ratings appropriate for your research objectives

- Metadata Utilization: Leverage synthesis condition filters to identify processing-structure-property relationships

- Cross-Platform Integration: Combine web interface exploration with API access and external tools like COMBIgor for comprehensive analysis

- Documentation Review: Regularly check the "About" and "Stats" sections for interface updates and new dataset additions

The HTEM-DB web interface represents a powerful tool for accelerating materials discovery through data-driven approaches. By following this structured exploration guide, researchers can efficiently navigate this extensive experimental database to uncover new materials relationships and advance materials innovation for energy, computing, and security applications.

Leveraging the HTEM API for Programmatic Data Access and Bulk Downloads

The High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB) represents a significant advancement in materials science, providing a public repository for large volumes of high-quality experimental data generated at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [20] [2]. For researchers engaged in data-driven materials discovery and machine learning, programmatic access via the HTEM Application Programming Interface (API) is crucial for efficiently extracting, analyzing, and integrating this wealth of information into computational workflows [11] [2]. This technical guide details the methodologies for leveraging the HTEM API, framed within the broader context of high-throughput experimental materials database exploration research. It provides researchers and scientists with the protocols necessary to programmatically access and bulk-download structured datasets encompassing material synthesis conditions, chemical composition, structure, and functional properties [1] [17].

The HTEM-DB is distinct from many other materials databases as it hosts experimental data rather than computational predictions [2]. It is populated via NREL's Research Data Infrastructure (RDI), a custom data management system integrated directly with laboratory instrumentation, which automatically collects, processes, and stores experimental data and metadata [2]. The database is continuously expanding with data from ongoing combinatorial experiments on inorganic thin-film materials, covering a broad range of chemistries such as oxides, nitrides, and chalcogenides, and characterizing properties like optoelectronic, electronic, and piezoelectric performance [2].

Data access is available through two primary interfaces, each serving different user needs:

- Web Interface (

htem.nrel.gov): An interactive tool for exploring, visualizing, and downloading data via a graphical user interface [1] [17]. - Programmatic API (

htem-api.nrel.gov): A dedicated API that provides a direct, scriptable interface for downloading all public data, enabling automation and integration into custom analysis pipelines [20] [1].

The primary advantage of the API is its ability to facilitate large-scale data retrieval for machine learning and high-throughput analysis, which is essential for discovering complex relationships between material synthesis, processing, composition, structure, and properties [20] [2].

Data Access Workflow and System Architecture

The workflow for programmatic data access interacts with a sophisticated backend system. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from user request to data retrieval, highlighting the interaction between key components of NREL's Research Data Infrastructure.