Unlocking Enzyme Mechanisms: A Practical Guide to Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Validation in Drug Discovery

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to validating kinetic mechanisms using pre-steady-state methods.

Unlocking Enzyme Mechanisms: A Practical Guide to Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Validation in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to validating kinetic mechanisms using pre-steady-state methods. It covers the foundational principles that distinguish pre-steady-state from steady-state kinetics, explores advanced methodological approaches like stopped-flow and rapid quench, and addresses common troubleshooting scenarios to optimize experimental design. Furthermore, it details how pre-steady-state data serves as a powerful tool for cross-validation with other structural and biophysical techniques, enabling accurate characterization of enzyme targets and the development of high-efficacy therapeutics with optimized binding parameters.

Beyond Steady-State: Foundational Principles of Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

The pre-steady-state phase of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction provides a critical window into the transient kinetic events that occur during the first few turnovers before a reaction reaches a steady state. This phase is often characterized by a rapid "burst" of product formation, the amplitude of which corresponds to the concentration of active enzyme-substrate complexes formed initially [1]. Analyzing this burst phase allows researchers to isolate and measure individual steps in the catalytic cycle, such as the chemical conversion step and the release of products, which are often masked under steady-state conditions [1] [2]. Techniques such as rapid chemical quench-flow and stopped-flow spectrometry are essential for capturing these early millisecond-time-scale events, enabling the determination of fundamental kinetic parameters like the intrinsic rate of chemistry (k~pol~) and the rates of conformational changes [3] [2]. This guide compares the application of pre-steady-state kinetics across different enzyme systems, highlighting the key experimental data, methodologies, and reagent solutions that underpin this powerful analytical approach.

In enzyme kinetics, the reaction timeline is typically divided into distinct phases. The pre-steady-state phase encompasses the first few turnovers immediately after the enzyme and substrate are mixed, lasting from microseconds to milliseconds. During this transient period, the concentrations of various enzyme complexes (such as ES and EP) change rapidly until they reach a steady state [4]. This is often followed by the steady-state phase, where the concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex remains approximately constant over time, and the post-steady-state phase, where the substrate is depleted and the reaction slows [4].

For many enzymes, the pre-steady-state phase is marked by a burst phase—a rapid, exponential formation of product that corresponds to the first turnover cycle at the enzyme's active site [1] [2]. This burst occurs when a step after the chemical reaction (typically product release, described by the rate constant k~off~) is significantly slower than the initial chemical step [1]. The observation of a burst phase provides direct evidence that the chemical conversion is not the rate-limiting step in the overall catalytic cycle under steady-state conditions. The amplitude of the burst gives a direct measure of the concentration of active enzyme engaged with substrate, allowing for active site titration [2]. The subsequent linear, steady-state phase reflects the slower rate-limiting step (e.g., product release) [1].

Key Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Capturing the pre-steady-state phase requires specialized equipment and carefully designed experiments to measure reactions on a millisecond timescale.

Rapid Chemical Quench-Flow

This technique involves rapidly mixing enzyme and substrate solutions and, after a precisely controlled delay, quenching the reaction with a stopping agent (e.g., strong acid or base).

- Typical Workflow for a DNA Polymerase [2]:

- Pre-incubate polymerase (e.g., 50 nM) with a slight excess of DNA substrate (e.g., 200 nM).

- Rapidly mix this complex with a solution containing the incoming dNTP (e.g., 50 µM) to initiate the reaction.

- After a defined time (from milliseconds to seconds), quench the reaction with a stopping agent like NaOH or EDTA.

- Analyze the products, often using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to separate the extended primer from the substrate.

- Plot the product concentration versus time to obtain a burst curve, which is fitted to the equation:

[P] = A(1 - e^(-k_obs t)) + vtwhereAis the burst amplitude,k_obsis the observed first-order rate constant for the burst phase, andvis the steady-state velocity [2].

Stopped-Flow Spectrometry

This method rapidly mixes small volumes of enzyme and substrate and then follows the reaction in real-time based on a spectroscopic signal.

- Application in Studying Conformational Changes: The intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase (Fpg) was monitored to detect conformational transitions during its catalytic cycle. Upon binding an 8-oxoG-containing DNA substrate, multiple quenching and enhancement phases in the fluorescence trace were observed, corresponding to at least four distinct conformational changes within the time range of 2 ms to 10 s [3].

The logical progression from experimental setup to data analysis is summarized in the workflow below.

Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Systems

Pre-steady-state kinetics has been successfully applied to diverse enzyme systems to elucidate their unique mechanisms. The table below compares the kinetic behavior of two DNA repair enzymes, human OGG1 and bacterial Fpg, when processing damaged DNA.

Table 1: Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for DNA Glycosylases

| Feature | Human 8-Oxoguanine DNA Glycosylase (OGG1) | Bacterial Formamidopyrimidine-DNA Glycosylase (Fpg) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Substrate | 8-oxoG:C base pair [1] | 8-oxoG:C base pair & formamidopyrimidines (Fapy) [3] |

| Burst Phase Observation | Biphasic kinetics; rapid exponential burst followed by a linear steady-state phase [1] | Not explicitly a burst, but multiple conformational phases observed via fluorescence [3] |

| Burst Amplitude | Proportional to the concentration of actively engaged enzyme [1] | Not directly applicable |

| Burst Rate Constant (k~obs~) | Intrinsic rate of 8-oxoG excision (chemistry step) [1] | Multiple observed rates (k~obs1~, k~obs2~, etc.) for conformational changes [3] |

| Steady-State Rate | Limited by product (AP-site DNA) release rate (k~off~) [1] | Correlates with the rate-determining catalytic constant (k~cat~) [3] |

| Key Technique | Rapid quench-flow with fluorescent DNA substrate [1] | Stopped-flow, monitoring intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence [3] |

| Interpretation | Product release is slower than glycosidic bond cleavage. | Substrate recognition involves multiple fast conformational steps before chemistry. |

The data reveals a fundamental difference in the kinetic mechanism between these two related DNA repair enzymes. For OGG1, the clear burst phase indicates that product release is the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle [1]. In contrast, studies on Fpg using stopped-flow fluorescence highlight that its mechanism involves multiple conformational transitions—at least four with an abasic site substrate and five with an 8-oxoG-containing substrate—that are critical for achieving a catalytically competent state before the chemical step [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting pre-steady-state kinetic experiments, particularly for DNA-interacting enzymes like glycosylases and polymerases.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

| Reagent/Material | Function and Description | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Recombinant Enzyme | The enzyme of interest, often expressed with a tag (e.g., GST) for purification. Concentration and purity are critical. | OGG1 purified as a GST-fusion protein from E. coli and cleaved with HRV-3C protease [1]. |

| Defined Oligonucleotide Substrate | A synthetic DNA or RNA substrate containing the specific lesion or sequence of interest. Often fluorescently labeled for detection. | 5'-6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) labeled 34-mer oligonucleotide containing a single 8-oxoG residue [1]. |

| Annealing Buffer | Buffer for hybridizing complementary oligonucleotide strands to form a double-stranded substrate. | 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [1]. |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength, and cofactors for enzymatic activity. Often includes stabilizers like BSA. | 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% bovine serum albumin [1]. |

| Chemical Quench Solution | Stops the reaction instantly. Strong acid/base or chelating agents (e.g., EDTA for metal-dependent enzymes). | 1 M NaOH (also used for subsequent β-elimination to cleave the AP-site) [1]. |

| Gel Loading Buffer | For denaturing electrophoresis to separate and analyze reaction products. | 95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA [1]. |

The pre-steady-state phase, with its characteristic burst of product formation, is a definitive kinetic signature that reveals the intimate details of an enzyme's catalytic mechanism. As demonstrated through the comparison of OGG1 and Fpg, analyzing this transient phase allows researchers to move beyond the veil of the rate-limiting step observed in steady-state analysis and directly measure the elementary constants for chemical conversion and conformational changes [1] [3]. The methodologies of rapid quench-flow and stopped-flow kinetics, supported by a toolkit of highly defined reagents, provide the temporal resolution needed to capture these early events. Integrating pre-steady-state data is therefore indispensable for validating a complete and accurate kinetic mechanism, ultimately informing rational drug design and advancing our understanding of enzymatic function in health and disease.

- Steady-state kinetics provides averaged parameters like ( k{cat} ) and ( Km ) from linear-phase data, masking the richness of individual catalytic steps [1] [5].

- Pre-steady-state kinetics captures transient, early-phase reactions to isolate and measure rapid elementary steps such as substrate binding, chemistry, and product release [6] [1].

- The comparative analysis reveals that pre-steady-state methods are indispensable for characterizing burst-phase kinetics, time-dependent inhibition, and obtaining true active enzyme concentrations [7] [1].

- Experimental applications in drug discovery and enzymology demonstrate how pre-steady-state analysis validates mechanisms and overcomes the limitations of steady-state parameters [6] [7].

Traditional enzyme kinetics, governed by Michaelis-Menten parameters, has long relied on steady-state measurements where the enzyme-substrate complex concentration remains constant [5]. This approach yields two fundamental parameters: ( Km ), the Michaelis constant measuring enzyme affinity for its substrate, and ( k{cat} ), the catalytic turnover number representing the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time [5]. While these parameters have served as foundational pillars in enzymology, they represent macroscopic averages of multiple microscopic steps, potentially obscuring crucial mechanistic details and limiting their predictive power in complex biological systems and drug discovery applications.

The steady-state phase occurs after an initial rapid burst of enzyme-substrate complex formation, when the concentration of ES remains relatively constant as it forms and breaks down at equal rates [5]. However, this equilibrium perspective masks the rich transient kinetics that occur during the critical first turnover before the system reaches steady state. What ( k{cat} ) and ( Km ) cannot reveal are the individual rate constants for elementary steps such as substrate binding, conformational changes, chemical catalysis, and product release—precisely the information needed to fully understand enzymatic mechanisms and develop targeted therapeutic interventions [7] [1].

Fundamental Principles and Kinetic Regimes

Steady-State Kinetics: The Macro View

Steady-state kinetics operates under conditions where substrate concentration greatly exceeds enzyme concentration ([S] >> [E]), allowing multiple catalytic turnovers to be observed while maintaining relatively constant substrate levels [1]. The characteristic rectangular hyperbola of the Michaelis-Menten plot emerges from this regime, with ( Km ) indicating the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity and ( V{max} ) representing the theoretical maximum rate when all enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate [5]. The ratio ( k{cat} = V{max}/[E]_total ) provides a measure of catalytic efficiency, but importantly, it reflects the slowest step in the catalytic cycle under steady-state conditions, which may not be the chemical transformation itself.

The fundamental limitation of this approach lies in its temporal resolution. By focusing on the linear phase of product formation, steady-state kinetics effectively ignores the pre-steady-state burst phase that typically occurs within milliseconds to seconds after reaction initiation [1] [5]. For enzymes where product release is rate-limiting, ( k_{cat} ) primarily reflects the off-rate of product rather than the chemical step of catalysis. This conceptual simplification proved useful for classifying enzyme behaviors but provides an incomplete picture of the actual catalytic mechanism.

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics: The Micro View

Pre-steady-state kinetics examines the transient phase of enzymatic reactions before the system reaches equilibrium, typically using high enzyme concentrations ([E] ≈ [S] or [E] > [S]) to amplify the signal from early reaction events [1]. This approach enables researchers to dissect the catalytic cycle into its constituent elementary steps and measure their individual rate constants. The pre-steady-state phase is characterized by a rapid exponential burst of product formation followed by establishment of the linear steady-state phase [1]. The burst amplitude often corresponds to the concentration of active enzyme engaged with substrate, while the burst rate constant reports on steps leading up to and including the first chemical transformation [1].

The experimental capture of these rapid events requires specialized techniques such as rapid mixing and quenching instruments (e.g., stopped-flow and quench-flow apparatus) that can reliably measure reactions on timescales as short as milliseconds [6] [1]. Single-turnover kinetics, a specialized pre-steady-state approach where enzyme concentration exceeds substrate concentration ([E] >> [S]), prevents catalytic cycling and isolates the first chemical step of the reaction [1]. These transient kinetic methods provide direct observation of the actual catalytic mechanism rather than inferring it from steady-state parameters.

Comparative Analysis: Key Parameters and Their Significance

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Steady-State vs. Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Approaches

| Parameter/Feature | Steady-State Kinetics | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Time Scale | Seconds to minutes | Milliseconds to seconds |

| Enzyme:Substrate Ratio | [E] << [S] | [E] ≈ [S] or [E] > [S] |

| Primary Measured Parameters | ( Km ), ( V{max} ), ( k_{cat} ) | Burst amplitude (( A )), burst rate (( k_{obs} )), elementary rate constants |

| Phase Measured | Linear steady-state phase | Exponential burst phase preceding steady state |

| Information Content | Averaged parameters across multiple turnovers | Individual rate constants for specific steps |

| Active Site Titration | Not directly possible | Direct measurement via burst amplitude |

| Rate-Limiting Step Identification | Identifies slowest step in catalytic cycle | Distinguishes chemical steps from physical steps |

| Technical Requirements | Standard spectrophotometry, manual mixing | Rapid mixing instruments (stopped-flow, quench-flow) |

What kcat and Km Don't Reveal

The fundamental parameters of steady-state kinetics provide a useful but limited perspective on enzyme function. ( Km ), while often described as a measure of enzyme-substrate affinity, is actually a complex constant that depends on multiple individual rate constants (( Km = (k{-1} + k{cat})/k1 ) for a simple mechanism). It cannot distinguish between tight binding (small ( Km )) due to rapid substrate association versus slow product release. Similarly, ( k_{cat} ) represents the turnover number but conceals whether chemistry, a conformational change, or product release limits the overall catalytic rate.

Pre-steady-state kinetics reveals several critical aspects that steady-state parameters cannot detect:

- Burst kinetics: Many enzymes exhibit a rapid initial burst of product formation followed by a slower steady-state rate, indicating that a step after chemistry (often product release) is rate-limiting [1]. The amplitude of this burst provides a direct measure of active enzyme concentration, while the burst rate constant reports on the chemical step or steps preceding the rate-limiting step [1].

- Elementary rate constants: Unlike the composite parameters ( k{cat} ) and ( Km ), pre-steady-state methods can determine individual rate constants for substrate binding (( k{on })), chemical conversion (( k{chem} )), and product release (( k_{off} )) [6] [1].

- Transient intermediates: The formation and decay of enzyme-bound intermediates can be directly observed, providing mechanistic insights invisible to steady-state analysis [1].

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters Resolved by Pre-Steady-State Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Mechanistic Insight Provided |

|---|---|---|

| ( k_{on} ) | Substrate association rate constant | Determines how rapidly E-S complex forms; diffusion control |

| ( k_{off} ) | Substrate dissociation rate constant | Measures stability of E-S complex |

| ( k_{chem} ) | Chemical step rate constant | Intrinsic catalytic power of enzyme |

| ( k_{product release} ) | Product dissociation rate constant | Often rate-limiting in steady state |

| Burst Amplitude | Concentration of active E-S complexes | Active site titration; functional enzyme concentration |

| Conformational change rates | Isomerization steps before/after chemistry | Activation barriers for structural transitions |

Applications in Mechanistic Analysis

The enhanced resolution of pre-steady-state kinetics makes it particularly valuable for characterizing complex enzymatic mechanisms. For DNA repair enzymes like human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1), pre-steady-state analysis revealed that the enzyme exhibits a rapid burst of 8-oxoG excision followed by a slower steady-state phase limited by product release [1]. This mechanistic understanding would be impossible to deduce from ( k{cat} ) and ( Km ) alone, as these composite parameters would only reflect the product release step under steady-state conditions.

In drug discovery, pre-steady-state methods are essential for characterizing time-dependent inhibition, a phenomenon where the potency of an inhibitor increases with pre-incubation time [7]. Many successful therapeutic drugs are time-dependent inhibitors with slow off-rates, properties that can only be properly quantified using transient kinetic methods [7]. Similarly, the identification of tight-binding inhibitors (with Ki values near the enzyme concentration) requires specialized analysis beyond standard Michaelis-Menten approaches [7].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Steady-State Protocol

The standard steady-state kinetic assay involves monitoring product formation over time under conditions where [S] >> [E]. A typical protocol includes [5]:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare enzyme and substrate solutions separately in appropriate reaction buffer. For Michaelis-Menten analysis, vary substrate concentration while maintaining constant enzyme concentration.

- Reaction Initiation: Mix enzyme and substrate to start the reaction, typically using a temperature-controlled spectrophotometer.

- Continuous Monitoring: Measure the linear increase in product (or decrease in substrate) with time, ensuring measurements occur during the steady-state phase before significant substrate depletion.

- Data Analysis: Plot initial velocity (v) versus substrate concentration ([S]) and fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation: ( v = (V{max}[S])/(Km + [S]) ). Transform data using Lineweaver-Burk or other linear representations if needed.

This approach requires that less than 5% of substrate is consumed during the measurement period to maintain constant substrate concentration. The linear time courses provide no information about events during the first enzymatic turnover.

Pre-Steady-State Protocol

Pre-steady-state kinetics requires specialized equipment to observe reactions on millisecond timescales. A representative protocol for studying nucleotide incorporation by DNA polymerase using a rapid quench-flow instrument includes [6]:

- Instrument Preparation: Equilibrate the rapid quench-flow instrument (e.g., RQF-3) at the desired temperature (typically 25°C or 37°C). Wash and dry all fluid lines, including drive syringes and reaction loops.

- Reaction Mixture Design: Prepare Pre-mixture I containing enzyme (e.g., DNA polymerase) and DNA substrate at appropriate concentrations (e.g., 500 nM enzyme, 1 μM DNA). Prepare Pre-mixture II containing nucleotide substrate and Mg²⁺ cofactor [6].

- Rapid Mixing and Quenching: Load pre-mixtures into syringes and program instrument for desired reaction times. The instrument rapidly mixes the two pre-mixtures, allows reaction to proceed for specified times (as short as 0.005 seconds), then quenches with acid or EDTA.

- Product Analysis: Separate reaction products using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Quantify product formation using appropriate detection methods (fluorescence, radioactivity).

- Data Fitting: Fit the time course of product formation to a burst equation: ( [Product] = A(1 - e^{-k{obs}t}) + k{ss}t ), where A is burst amplitude, ( k{obs} ) is observed burst rate, and ( k{ss} ) is steady-state rate [1].

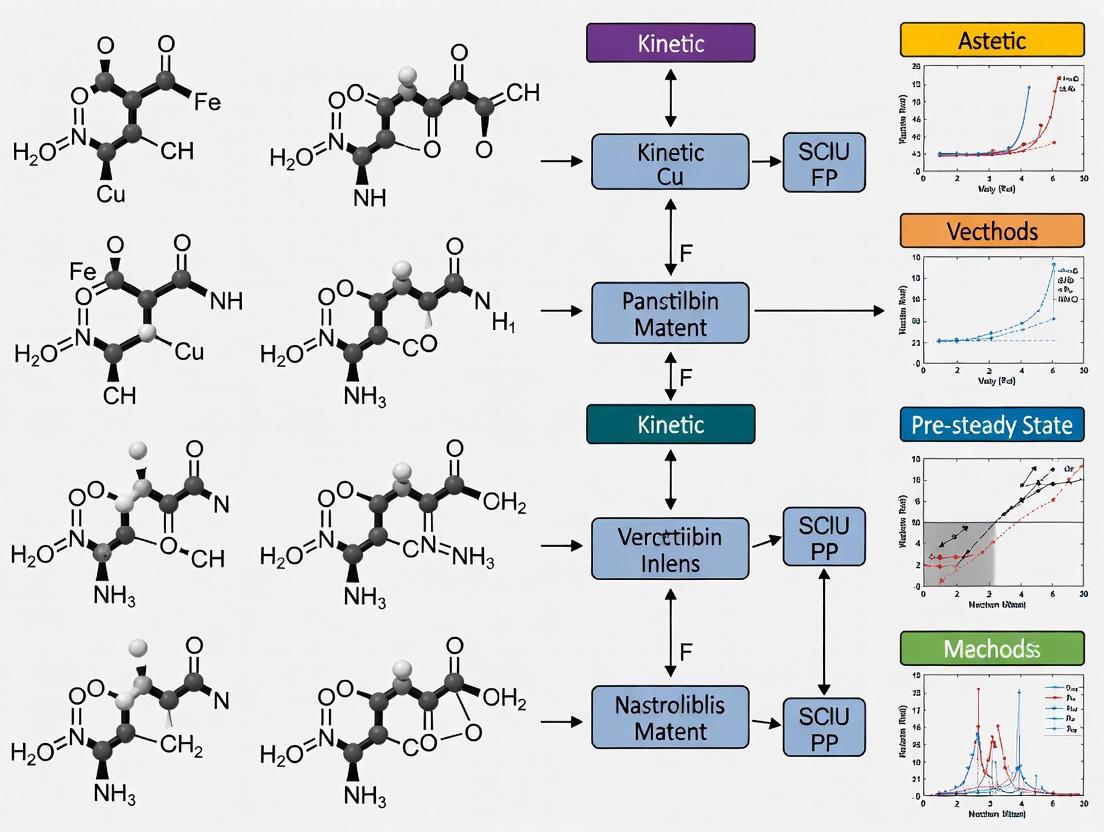

Figure 1: Rapid Quench-Flow Experimental Workflow for Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

| Reagent/Instrument | Function/Role | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Quench-Flow Instrument | Rapid mixing and quenching on millisecond timescale | Measuring single-turnover kinetics of DNA polymerases [6] |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Rapid mixing and continuous optical monitoring | Observing rapid conformational changes by fluorescence or absorbance |

| Fluorescent-Labeled Oligonucleotides | DNA substrate with detectable tag | Monitoring nucleotide incorporation kinetics [6] [1] |

| Modified Nucleotides (8-oxodG) | Lesion-containing DNA substrates | Studying DNA repair enzyme mechanisms [6] [1] |

| Rapid Chemical Quenchers (EDTA, Acid) | Instantaneous reaction termination | Trapping intermediate states at precise time points [6] |

| High-Purity Recombinant Enzymes | Well-characterized enzyme preparation | Ensuring accurate active site concentration determination [6] |

The comparative analysis of steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic approaches reveals a fundamental dichotomy in enzymology: while steady-state parameters like ( k{cat} ) and ( Km ) provide a useful macroscopic description of enzyme activity, they inevitably conceal the rich mechanistic complexity of the catalytic cycle. Pre-steady-state kinetics serves as an essential tool for validating kinetic mechanisms by isolating and quantifying individual steps in the enzymatic pathway, from initial substrate binding through chemical transformation to product release.

For researchers in drug development and enzymology, the integration of both approaches provides a comprehensive understanding of enzyme function. Steady-state kinetics offers an efficient means for initial characterization and inhibitor screening, while pre-steady-state analysis delivers the mechanistic resolution needed for rational drug design and detailed mechanistic studies. As the field advances, the continued application of pre-steady-state methods will undoubtedly uncover new dimensions of enzymatic behavior, further illuminating what ( k{cat} ) and ( Km ) alone cannot tell us.

The Critical Role of High Enzyme Concentrations in Capturing Early Reaction Events

In the field of enzymology, the standard approach to kinetic characterization has traditionally relied on steady-state kinetics, where enzyme concentration is significantly lower than substrate concentration ([E] << [S]), allowing researchers to measure parameters like kcat and Km [8] [1]. However, this method only provides a simplified view of the catalytic cycle, as these parameters represent combinations of all the individual rate constants involved in the enzymatic reaction [9]. To truly unravel the mechanistic details of how enzymes work—including the identification of transient intermediates and the measurement of individual rate constants for specific steps like substrate binding, chemical conversion, and product release—researchers must turn to pre-steady-state kinetics [1] [9]. This approach requires a fundamental shift in experimental design: using high enzyme concentrations relative to substrate to directly observe the early, transient events of the catalytic cycle that occur within milliseconds to seconds after the reaction begins [1] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in experimental setup between steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic approaches, highlighting the critical role of enzyme concentration:

This methodological shift enables researchers to capture the "burst phase" or "lag phase" that reveals the intrinsic chemical capabilities of the enzyme before later steps like product release become rate-limiting [10] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these early events is crucial for designing more effective enzyme inhibitors and therapeutics, as it reveals the actual chemical transformation rates rather than the product release rates that often dominate steady-state measurements [1].

Theoretical Foundation: Why High Enzyme Concentrations Are Essential

The Scientific Rationale for Elevated Enzyme Concentrations

In pre-steady-state kinetics, the requirement for high enzyme concentrations relative to substrate is not arbitrary but stems from fundamental principles of enzyme action. When enzyme concentration approaches or exceeds substrate concentration ([E] ≈ [S] or [E] > [S]), a significant proportion of the total substrate can be converted during the first catalytic cycle, making it possible to observe the transient phase of the reaction [1]. This stands in stark contrast to steady-state conditions, where the enzyme concentration is so low that the initial burst of product formation is undetectable, and only the linear, steady-state phase is observable [1].

The ability to populate and observe short-lived intermediates is particularly important because the pre-steady-state regime encompasses the brief period (typically milliseconds to seconds) after reaction initiation when the system approaches steady-state conditions [9]. During this phase, the reaction mechanism dictates the order in which short-lived intermediates become populated successively [9]. At high enzyme concentrations, the formation of these intermediates becomes sufficiently synchronized across the enzyme population to allow for detection and quantification.

Molecular Events Captured During the Pre-Steady-State Phase

The early reaction events observable under high enzyme concentrations include:

- Rapid substrate binding and formation of enzyme-substrate complexes

- Conformational changes in the enzyme structure following substrate binding

- Chemical catalysis itself (the bond-breaking and bond-forming steps)

- Formation and decay of transient catalytic intermediates

- Product formation before release from the active site

For example, with human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1), pre-steady-state analysis revealed that the chemical step of 8-oxoG excision occurs rapidly during the burst phase, while the slower steady-state phase is limited by product release [1]. This separation of elementary steps is only possible when using enzyme concentrations high enough to observe the first turnover.

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Designs for Pre-Steady-State Analysis

Key Kinetic Approaches and Their Applications

Researchers employ several complementary approaches to study enzyme kinetics under pre-steady-state conditions, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Table 1: Comparison of Kinetic Approaches for Enzyme Characterization

| Approach | Enzyme:Substrate Ratio | Measured Parameters | Key Applications | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State | [E] << [S] | kcat, Km | Routine characterization; inhibitor screening | Standard spectrophotometry; manual mixing |

| Pre-Steady-State | [E] < [S] (but high [E]) | Burst amplitude (kburst); rate constants for elementary steps | Mechanistic studies; identification of rate-limiting steps | Rapid mixing (stopped-flow, quench-flow); high [E] |

| Single-Turnover | [E] > [S] | First-order rate constant for chemical step (kchem) | Isolation of chemical step from physical steps | Rapid mixing; enzyme saturation |

Technical Implementations for Rapid Kinetic Analysis

Several specialized techniques have been developed to capture the early events of enzymatic reactions:

Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometry: This method involves rapid mixing of enzyme and substrate solutions followed by immediate monitoring of optical signals (absorbance or fluorescence) as the reaction proceeds in an observation cell [9]. While powerful, it requires chromophoric changes associated with the reaction.

Chemical Quench-Flow: In this approach, the reaction is initiated by rapid mixing of enzyme and substrate, followed after a specified time by mixing with a quenching agent (acid, base, or organic solvent) that denatures the enzyme and liberates noncovalently bound species [9]. The quenched mixture is then analyzed offline, often using HPLC or mass spectrometry.

Rapid Mixing with ESI Mass Spectrometry: A newer approach combines electrospray ionization mass spectrometry with online rapid mixing to monitor enzymatic reactions in the pre-steady-state regime [9]. This method provides direct information on chemical transformations without requiring chromophoric substrates.

The workflow for a typical pre-steady-state experiment using rapid mixing approaches can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies Demonstrating the Power of Pre-Steady-State Analysis

Human 8-Oxoguanine DNA Glycosylase (OGG1)

Research on OGG1 provides a compelling case study on the importance of high enzyme concentrations in revealing authentic mechanistic details. Under steady-state conditions ([E] << [S]), the excision of 8-oxoG appears as a linear time course, suggesting a constant reaction rate [1]. However, when the enzyme concentration is increased to pre-steady-state levels ([E] < [S] but with high [E]), the time course becomes biphasic, with a rapid exponential burst phase followed by a linear steady-state phase [1]. The burst amplitude corresponds to the concentration of enzyme properly engaged on the substrate, while the first-order rate constant of the burst corresponds to the intrinsic rate of 8-oxoG excision [1]. This separation of the chemical step from product release was only possible through pre-steady-state analysis with elevated enzyme concentrations.

Cellulase Cel7A from Trichoderma reesei

Pre-steady-state analysis of Cel7A acting on its natural insoluble cellulose substrate revealed unexpected complexities in the hydrolytic mechanism. Using high enzyme concentrations and a continuous assay with amperometric biosensors, researchers identified that the dissociation of the enzyme-substrate complex (with a half-time of ∼30 s) is rate-limiting for the overall hydrolytic process [11]. The results indicated that Cel7A cleaves about four glycosidic bonds per second during processive hydrolysis, but the specific activity at pseudo-steady state is 10-25-fold lower due to stalling of the processive movement and low off-rates [11]. This fundamental insight explains the distinctive variability in hydrolytic activity across different cellulase-substrate systems and would not have been possible without pre-steady-state analysis.

Hysteretic Enzymes with Burst or Lag Phases

Some enzymes exhibit hysteretic behavior, characterized by a slow response to sudden changes in substrate concentration [10]. These enzymes display atypical progress curves with either a burst phase (initial velocity higher than steady-state velocity) or a lag phase (initial velocity lower than steady-state velocity) [10]. For example, the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase demonstrates a lag phase where the initial velocity is lower than the steady-state velocity due to a slow transition between enzyme forms [10]. Such behavior is only detectable when using enzyme concentrations high enough to observe the early reaction phase before steady state is established.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters from Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Studies

| Enzyme | Burst Phase Rate Constant | Burst Amplitude | Steady-State Rate | Molecular Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OGG1 [1] | kburst = Intrinsic 8-oxoG excision rate | [E] actively engaged with substrate | koff = Product release rate | Chemistry faster than product release |

| Cel7A [11] | kprocessive ≈ 4 bonds/s | Productively threaded complexes | koff (half-time ∼30 s) | Dissociation rate-limiting |

| Xylanase [9] | kcat (glycosylation) = 20 s⁻¹ | Covalent glycosyl-enzyme intermediate | kdeglycosylation = 1.2 s⁻¹ | Glycosylation faster than deglycosylation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Successful pre-steady-state kinetic analysis requires specialized reagents and instrumentation. The following table summarizes key research solutions and their applications in capturing early reaction events:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

| Reagent/Method | Function in Pre-Steady-State Analysis | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Quench-Flow Instrument | Mechanically mixes enzyme and substrate, then quenches reaction after precise time intervals (ms-s) | Measurement of transient intermediates in OGG1 reaction [1] |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Rapid mixing with continuous optical monitoring | Fast kinetic measurements for chromophoric reactions [9] |

| ESI Mass Spectrometry with Online Mixing | Direct monitoring of chemical species during reaction progress | Pre-steady-state kinetics of xylanase [9] |

| Amperometric Biosensors | Real-time monitoring of product formation without sampling | Cellobiose detection in cellulase kinetics [11] |

| Fluorescent-Labeled Oligonucleotides | Sensitive detection of substrate conversion and product formation | OGG1 activity measurements [1] |

| Saturnable Enzyme Mutants | Trapping of specific catalytic intermediates | Characterization of enzyme reaction pathways |

The critical role of high enzyme concentrations in capturing early reaction events cannot be overstated. While steady-state kinetics remains valuable for initial enzyme characterization and inhibitor screening, pre-steady-state kinetics with elevated enzyme concentrations provides unparalleled insight into the actual mechanism of enzyme action. This approach has revealed fundamental truths about enzymatic processes: that the chemical step is often faster than product release, that many enzymes exhibit complex hysteretic behavior, and that the rate-limiting step observed under steady-state conditions may not reflect the enzyme's true catalytic power [10] [1] [11].

For researchers in enzymology and drug development, embracing pre-steady-state methodologies means moving beyond simplified kinetic parameters to a more profound understanding of the dynamic molecular events that constitute enzyme catalysis. The continued development of rapid mixing technologies, sensitive detection methods, and sophisticated modeling approaches will further enhance our ability to capture these early reaction events, ultimately leading to better-designed enzymes for industrial applications and more effective therapeutic agents targeting specific catalytic steps.

In the development of drugs and the validation of kinetic mechanisms, accurately identifying the rate-limiting step—whether a chemical transformation or a product release process—is a fundamental challenge. For researchers and drug development professionals, this distinction is not merely academic; it dictates the strategic focus of optimization efforts, influencing everything from lead compound design to the success of preclinical studies. The application of pre-steady state kinetics provides a powerful toolkit for deconvoluting complex reaction pathways and pinpointing these critical bottlenecks with high temporal resolution. This guide objectively compares the methodologies, data interpretation, and reagent solutions used to differentiate between chemical and release steps, providing a framework for validating kinetic mechanisms.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

The Rate-Limiting Step in Chemical Kinetics

In chemical kinetics, the rate-limiting step is the slowest elementary step in a reaction sequence that determines the overall reaction rate [12]. For a process to be classified as "simple" and its rate described by a standard rate equation, the system must be in a steady state and possess a well-defined, constant rate-limiting step of growth [12]. The General Rate Equation (GRE), often expressed as dα/dt = k(T)f(α), is a widely used mathematical tool for analyzing such rates from thermoanalytical data [13]. However, a crucial insight from recent research is that the GRE generally describes the kinetics of the measured thermoanalytical effect (e.g., heat flow in DSC) rather than the underlying chemical conversion itself. For complex processes, the kinetic degree of conversion (α_kin) and the thermoanalytical degree of conversion (α) can differ significantly. Consequently, the kinetic parameters derived (e.g., activation energy, E) describe the measured signal's change and should not be used to draw mechanistic conclusions about the reaction [13].

Product Release as a Rate-Limiting Step

In drug action, "product release" can refer to the dissociation of a final product from an enzyme's active site or the release of an active pharmaceutical ingredient from a delivery system. When this physical dissociation or diffusion process is slower than the chemical transformation steps, it becomes the rate-limiting step. The kinetics of such physical steps are often governed by different principles than chemical steps, such as diffusion laws or cooperative binding effects, and may not follow the same temperature dependencies described by the Arrhenius equation. Identifying a product release bottleneck often shifts the optimization strategy from modifying chemical structures to engineering the physical environment or altering binding interfaces.

Comparative Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Distinguishing between a chemical and a release rate-limiting step requires a suite of specialized experimental protocols. The following table summarizes the core approaches used in pre-steady state kinetics.

Table 1: Core Experimental Methods for Identifying Rate-Limiting Steps

| Method | Primary Application | Key Measurable | Interpretation for Chemistry vs. Release |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Chemical Quenching | Chemical step analysis | Product concentration formed per unit time during a single turnover | A burst phase indicates a fast chemical step followed by a slower, non-chemical step (e.g., release) [12]. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometry | Fast reaction monitoring | Change in optical signal (absorbance, fluorescence) after rapid mixing | A single exponential phase suggests a single rate-limiting step; multiple phases indicate complexity. The step's nature is inferred from its solvent isotope effect or sensitivity to viscosity. |

| φ-E Test (Phi-E Test) | Validation of rate-limiting step assumption | System response to a sudden change in an external parameter (E) (e.g., T, P) | A instantaneous rate change (dα/dt) proportional to the parameter change (dE) validates a single, constant rate-limiting step. A lag or decay invalidates this assumption, suggesting a shift in the limiting step or complex mechanism [12]. |

| Isothermal Calorimetry (ITC) | Energetics of binding and kinetics | Heat flow over time during a binding interaction | The shape of the binding isotherm and kinetic traces can separate the binding event (chemistry) from conformational changes or dissociation (release). |

| Pressure-Jump Relaxation | Analysis of reaction dynamics | System relaxation kinetics after a rapid pressure perturbation | Particularly sensitive to volume changes, often associated with product release or large conformational changes rather than bond-making/breaking. |

Detailed Protocol: The φ-E Test for Validating a Rate-Limiting Step

The φ-E test is a critical experimental check to validate the assumption of a constant rate-limiting step, which is foundational for reliable kinetic analysis [12].

Objective: To verify that a single, rate-limiting step of growth remains constant throughout the observed transformation. Principle: The test exploits the fact that if a single rate-limiting step governs the process, its rate will instantaneously reflect any sudden change in an external parameter (E), such as temperature (T) or partial pressure (P_i) [12]. Procedure:

- Initial Steady-State: Conduct the reaction under constant temperature and partial pressure (if a gas is involved) until a steady-state rate (dα/dt)_1 is established.

- Parameter Jump: Introduce a sudden, step-change in the external parameter E (e.g., increase the temperature by 10°C).

- Immediate Measurement: Instantly measure the new reaction rate (dα/dt)_2 immediately after the jump.

- Validation Check: Calculate the ratio φE = [(dα/dt)2 - (dα/dt)1] / ΔE. If the rate change is instantaneous and the ratio φE remains constant for different jumps, the assumption of a single, constant rate-limiting step is validated. A lag or a progressively changing φ_E indicates that no single rate-limiting step exists or that it shifts during the reaction [12].

Detailed Protocol: Rapid Chemical Quenching for Burst Kinetics

This method is a classic pre-steady state approach to detect if a chemical step forms a product faster than it can be released.

Objective: To measure the stoichiometry of an early product formation burst, indicative of a fast chemical step followed by a slow release step. Principle: The reaction is initiated and then stopped (quenched) at very short time intervals to capture intermediates and products formed during the first few enzyme turnovers. Procedure:

- Rapid Mixing: An enzyme is rapidly mixed with its substrate in a specialized stopped-flow or quench-flow instrument.

- Incubation & Quenching: The reaction mixture is aged for a precise, millisecond-scale time period before being ejected into a quenching solution (e.g., strong acid or base) that instantly stops the reaction.

- Analysis: The quenched sample is analyzed (e.g., via HPLC, spectrometry) to quantify the amount of product formed.

- Interpretation: A plot of product formed versus time that shows a rapid "burst" phase (representing the fast chemical formation of product in the active site) followed by a slower, linear steady-state phase (representing the rate-limiting release of that product) provides direct evidence that product release is the rate-limiting step.

Data Presentation and Comparative Analysis

The following tables synthesize hypothetical experimental data, representative of real-world outcomes, to illustrate how different methods distinguish between chemical and release limitations.

Table 2: Simulated Pre-Steady State "Burst" Kinetics Data Indicative of Rate-Limiting Product Release

| Time (ms) | Product Concentration (µM) | Phase Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 8.5 | Burst Phase: Rapid formation of product, equivalent to the enzyme's active site concentration. The chemistry is fast. |

| 10 | 9.2 | |

| 20 | 9.8 | |

| 50 | 11.0 | Transition: The burst phase concludes. |

| 100 | 12.5 | Linear Steady-State Phase: The slope of this line represents the turnover number (k_cat), which is limited by the slow release of product from the enzyme. |

| 200 | 14.0 | |

| 500 | 17.5 |

Table 3: Comparative Kinetic Parameters from Model-Fitting

| Kinetic Parameter | Chemical Step Limited | Product Release Limited | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (Eₐ) | Typically higher, sensitive to chemical environment. | Often lower, may show weaker temperature dependence. | Eₐ from GRE-based methods may not be mechanistic for complex processes [13]. |

| Burst Amplitude | Absent or very small. | Present, often equals active site concentration. | Key evidence from rapid quenching experiments. |

| Solvent Isotope Effect (D₂O) | Significant if protons are transferred in the RLS. | Often small or absent. | Helps distinguish proton transfer chemistry from physical release. |

| Viscosity Effect | Usually minimal. | Pronounced slowdown if diffusion is key. | Increased viscosity will specifically impact a release-limited reaction. |

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

To aid in the conceptual and practical understanding of these methodologies, the following diagrams outline the core logical workflows.

Phi-E Test Validation Workflow

Differentiating Rate-Limiting Steps

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful kinetic characterization relies on high-quality, specific reagents. The following table details essential materials for these experiments.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Stopped-Flow Instrument | Rapid mixing of reagents (sub-millisecond) to initiate reactions for spectroscopic monitoring. | Essential for observing fast kinetic phases; often coupled with absorbance, fluorescence, or CD detection. |

| Chemical Quench-Flow Instrument | Rapid mixing, aging, and quenching of reaction mixtures at precise millisecond timescales. | The core apparatus for conducting burst kinetics experiments and quantifying early reaction intermediates. |

| High-Affinity Inhibitor/Substrate Analog | Traps free enzyme or binds to intermediate states, halting the catalytic cycle at specific points. | Used in pulse-chase experiments to dissect the order of individual steps within the mechanism. |

| Deuterated Solvent (D₂O) | Alters the solvent environment to probe for kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) on reaction steps. | A significant solvent KIE suggests proton transfer is involved in the rate-limiting step. |

| Viscogen (e.g., Sucrose, Glycerol) | Increases the microviscosity of the reaction medium. | A pronounced decrease in rate with increased viscosity suggests a diffusion-limited step (e.g., product release). |

| Syringe-Driven Filter Devices | Rapid physical separation of free product from enzyme-bound product. | Used in manual quenching experiments to determine binding constants and release rates. |

Advanced Methods and Real-World Applications in Drug Discovery

In the study of enzyme mechanisms, steady-state kinetics provides only a averaged, macroscopic view of catalysis, often obscuring the individual steps that constitute the catalytic cycle. Pre-steady state kinetics, which examines the early moments of a reaction (typically milliseconds to seconds), allows researchers to isolate and characterize these transient steps, including substrate binding, chemical conversion, and product release. Among the most powerful techniques for accessing this time regime are stopped-flow spectrophotometry and rapid chemical quench-flow. These methods enable scientists to validate complex kinetic mechanisms by directly observing intermediates and determining individual rate constants, providing unparalleled insights into enzymatic function and mechanism that are fundamental to drug discovery and basic biochemical research.

Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometry

Principle and Instrumentation

Stopped-flow spectrophotometry is a rapid kinetics technique designed to study fast chemical and biochemical reactions occurring on the millisecond to second timescale. The fundamental principle involves the rapid mixing of two or more reagent solutions from drive syringes, after which the flow is abruptly stopped and the reaction progress is monitored in real-time using a sensitive detector [14]. This entire process happens within a dead time—the time required for the mixed solution to travel from the mixer to the observation cell—which in modern instruments can be as short as 200 microseconds [14].

The instrumentation typically includes:

- Drive syringes controlled by individual stepping motors for precise control over mixing ratios and flow rates [14]

- A high-efficiency mixer ensuring complete mixing within microseconds

- An observation cell where the reaction is monitored

- A hard-stop valve to instantaneously halt fluid flow

- Various detection systems including absorbance, fluorescence, circular dichroism, and light scattering [14]

Table 1: Common Detection Methods in Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometry

| Detection Method | Information Obtained | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Absorbance | Structural changes of chromophores | Enzyme-cofactor interactions, substrate depletion |

| Fluorescence | Environment of fluorophores | Protein folding, ligand binding |

| Fluorescence Anisotropy | Mobility of fluorophores | Macromolecular association/dissociation |

| Circular Dichroism (Far UV) | Changes in secondary structure | Protein conformational changes |

| Circular Dichroism (Aromatic) | Alterations in tertiary structure | Active site rearrangements |

| Light Scattering | Size of particles | Protein aggregation, complex formation |

Key Experimental Applications and Protocols

Investigating Enzyme Kinetics

Stopped-flow spectroscopy is particularly valuable for elucidating enzyme kinetic mechanisms by monitoring the pre-steady state phase of reactions. A representative protocol for studying enzyme kinetics using stopped-flow involves [15]:

Sample Preparation: Purify enzyme and substrates in appropriate buffers. For fluorescence detection, intrinsic tryptophan residues or specifically incorporated fluorescent probes (like 2-aminopurine) can serve as reporters.

Instrument Setup: Thermostat the instrument to desired temperature (typically 25°C). Configure detection parameters (excitation/emission wavelengths for fluorescence, or wavelength for absorbance).

Rapid Mixing: Load one syringe with enzyme and another with substrate. Rapidly mix equal volumes (typical total volume 24-100 μL per shot depending on instrument).

Data Collection: Trigger detection upon stopping flow. Collect data for approximately 5-10 half-lives of the reaction.

Data Analysis: Fit resulting time courses to exponential functions to determine observed rate constants (kobs). Plot kobs versus substrate concentration to derive fundamental kinetic parameters (kpol, Kd).

This approach was used to determine the kinetic mechanism of αY60W mutant 3-chloroacrylic acid dehalogenase (CaaD), where stopped-flow fluorescence experiments revealed a six-step model with individual rate constants for substrate binding, chemistry, and a conformational change [16].

Sequential Mixing Experiments

More complex multi-mixing stopped-flow instruments with three or four syringes enable sequential mixing experiments for studying reactions involving unstable intermediates [14]. A typical double-mixing protocol includes:

- First Mixing: Combine solutions from syringes 1 and 2 to generate an unstable reactant.

- Aging Period: Allow the mixture to incubate for a defined time (2 ms to several seconds) in a delay line.

- Second Mixing: Mix the aged solution with reagent from syringe 3.

- Detection: Monitor the second reaction optically.

This approach is invaluable for studying enzyme reactions where a reactive intermediate must be generated immediately before the reaction of interest.

Rapid Chemical Quench-Flow

Principle and Instrumentation

Rapid chemical quench-flow is another essential technique for studying pre-steady state kinetics, with a fundamentally different approach from stopped-flow spectrophotometry. Instead of directly observing the reaction in real-time, this method involves:

- Rapidly mixing reactant solutions

- Allowing the reaction to proceed for precisely controlled time intervals

- Quenching the reaction abruptly with a chemical denaturant (acid, base, or organic solvent)

- Analyzing the products using offline methods such as chromatography, electrophoresis, or mass spectrometry

The instrumentation shares similarities with stopped-flow systems, with drive syringes for reactants and quench solution, a mixing chamber, and a delay line whose length or flow rate determines the reaction time. The key distinction is the addition of a quenching solution and collection of the quenched mixture for subsequent analysis.

Key Experimental Applications and Protocols

Studying Transcription Elongation

Chemical quench-flow has been extensively used to investigate transcription kinetics. A representative protocol for studying nucleotide incorporation by RNA polymerase includes [17]:

Sample Preparation: Prepare promoter-free RNA:DNA elongation substrates, with RNA primers often radioactively labeled for sensitive detection.

Instrument Loading: Load one syringe with enzyme-substrate complex, another with NTP substrate, and a third with quench solution (typically acidic conditions or EDTA).

Rapid Mixing and Quenching: Mix enzyme and substrate solutions, allow reaction to proceed for predetermined times (milliseconds to seconds), then mix with quench solution.

Product Analysis: Separate elongated RNA products using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Quantify product formation using phosphorimaging or autoradiography.

Kinetic Analysis: Plot product formation versus time to determine the rate constant for nucleotide incorporation.

This approach was used to study T7 RNA polymerase kinetics, providing fundamental parameters such as nucleotide incorporation rates (kpol) and ground-state dissociation constants (Kd) for correct and incorrect nucleotides [17].

Elucidating Complex Kinetic Mechanisms

Chemical quench-flow is particularly powerful for determining the individual rate constants in multi-step enzymatic reactions. In the study of CaaD, rapid quench-flow experiments complemented stopped-flow fluorescence data to develop a comprehensive six-step kinetic model that included rate constants for substrate binding, chemical transformation, and product release [16].

Comparative Analysis: Stopped-Flow vs. Quench-Flow

Technical Comparison

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometry and Rapid Chemical Quench-Flow Techniques

| Parameter | Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometry | Rapid Chemical Quench-Flow |

|---|---|---|

| Time Resolution | ~200 μs to seconds | ~1-2 ms to seconds |

| Detection Method | Real-time optical (absorbance, fluorescence, CD) | Offline analysis (chromatography, electrophoresis) |

| Information Obtained | Direct observation of transients | Chemical identification of intermediates/products |

| Sample Consumption | 12-50 μL per shot (per reactant) | Typically higher due to analysis requirements |

| Throughput | Higher (immediate data collection) | Lower (requires separate analysis) |

| Applicable Systems | Requires chromophore/fluorophore | Universal (any reaction with analyzable products) |

| Data Interpretation | Indirect through signal changes | Direct chemical quantification |

| Key Applications | Protein folding, ligand binding, rapid conformational changes | Chemical mechanism, covalent intermediates, stoichiometry |

Experimental Data Comparison

Table 3: Comparative Kinetic Parameters from Representative Studies

| Enzyme/System | Technique | k_pol (s⁻¹) | K_d (μM) | kpol/Kd (μM⁻¹s⁻¹) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7 RNAP (GMP incorporation) | Stopped-Flow (Fluorescence) | 190 ± 10 | 70 ± 10 | 2.7 | [17] |

| T7 RNAP (GMP incorporation) | Chemical Quench-Flow (Radiometric) | 178 ± 15 | 52 ± 17 | 3.4 | [17] |

| T7 RNAP (AMP incorporation) | Stopped-Flow (Fluorescence) | 145 ± 5 | 71 ± 11 | 2.0 | [17] |

| CaaD (αY60W mutant) | Stopped-Flow (Fluorescence) | Multiple steps in 6-step model | [16] | ||

| CaaD (αY60W mutant) | Chemical Quench-Flow | Complementary data for full model | [16] |

Synergistic Applications

The true power of these techniques emerges when they are applied synergistically to the same enzymatic system. The investigation of 3-chloroacrylic acid dehalogenase (CaaD) exemplifies this approach [16]:

- Stopped-flow fluorescence using a tryptophan mutant (αY60W-CaaD) provided real-time monitoring of enzyme conformational changes during catalysis

- Rapid chemical quench-flow directly quantified bromide release and chemical intermediate formation

- Global simulation of both datasets yielded a comprehensive six-step kinetic model with individual rate constants for each step in the catalytic cycle

This combined approach validated the kinetic mechanism and revealed a conformational change occurring after chemistry that, together with product release, limits the overall turnover rate.

Comparative Workflows: Stopped-Flow vs. Quench-Flow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these techniques requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table outlines key solutions for researchers designing pre-steady state kinetic experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pre-Steady State Kinetics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Aminopurine (2AP) | Fluorescent adenine analog for monitoring nucleotide incorporation | Sensitive to base stacking; incorporated into DNA/RNA templates [17] |

| Radioactive Isotopes (³²P, ³H, ¹⁴C) | Sensitive detection in quench-flow experiments | Requires special safety precautions; used for labeling substrates [17] |

| Rapid Chemical Quenchants | Stopping reactions at precise times | Acid (HCl), base (NaOH), or denaturants (SDS, urea) [16] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introducing fluorescent reporters (tryptophan) | Enables stopped-flow fluorescence in proteins lacking native fluorophores [16] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Media | Protein purification and complex isolation | Essential for preparing homogeneous enzyme samples [16] |

| HPLC/GC Systems | Product analysis after quenching | Separation and quantification of reaction products [18] |

| Stopped-Flow Accessories | Extending technique capabilities | Temperature control units (-90°C to +85°C), multiple syringe configurations [14] |

Both stopped-flow spectrophotometry and rapid chemical quench-flow provide indispensable tools for dissecting enzymatic mechanisms at the pre-steady state level. While stopped-flow offers superior time resolution and real-time monitoring of reactions through spectroscopic signatures, chemical quench-flow provides direct chemical identification of intermediates and products. The most powerful insights often emerge from their complementary application, as demonstrated in the elucidation of complex kinetic mechanisms like that of CaaD. As these techniques continue to evolve with improved time resolution, reduced sample requirements, and enhanced detection capabilities, their integration with emerging technologies such as LLM-powered analysis platforms promises to further accelerate kinetic mechanism validation in biochemical research and drug development.

Electrospray Mass Spectrometry with On-Line Rapid-Mixing

The validation of kinetic mechanisms in biochemical processes, particularly in drug development, often requires the observation of fast reactions and short-lived intermediates. Pre-steady state kinetics provides this window into the earliest moments of a reaction, a capability that is crucial for understanding enzyme mechanisms, protein folding, and protein-ligand interactions. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) has emerged as a powerful technique for monitoring such reactions due to its sensitivity and ability to provide direct molecular weight information. However, conventional ESI-MS analysis is inherently susceptible to interference from non-volatile salts and buffers commonly used in physiologically relevant studies, which can suppress ionization and complicate mass spectra [19].

The integration of on-line rapid-mixing devices with ESI-MS represents a transformative advancement, enabling the direct mass spectrometric analysis of reactions under native, physiologically relevant conditions. This approach allows researchers to initiate a reaction and monitor its time-course directly from solutions containing biological buffers and salts, overcoming a significant limitation in traditional ESI-MS workflows [19]. This article objectively compares the performance of this emerging approach, particularly focusing on systems utilizing theta emitters for rapid mixing, against conventional desalting methods and other alternative techniques.

Technology Performance Comparison

The core of on-line rapid-mixing ESI-MS lies in its ability to mitigate the adduction of salts and buffers to analyte ions during the ionization process. This is achieved through innovative emitter design and gas-phase activation techniques. Theta emitters, which are glass emitters with an internal septum dividing the capillary into two channels, enable the simultaneous introduction of the sample in a biological buffer and a volatile MS-compatible solution immediately prior to electrospray [19]. This setup promotes incomplete mixing, creating a population of ESI droplets that are relatively depleted of non-volatile salts, thereby allowing the observation of protein ions that would otherwise be suppressed.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and a performance comparison between the rapid-mixing theta emitter approach and conventional ESI-MS sample preparation methods.

Table 1: Comparison of ESI-MS Approaches for Analyzing Samples in Non-Volatile Buffers

| Feature | Rapid-Mixing Theta Emitter ESI-MS | Conventional ESI-MS with Desalting | Submicron Emitters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | On-line mixing of sample with volatile salt/additive in a theta emitter immediately before ESI [19] | Off-line buffer exchange (e.g., dialysis, spin columns) into volatile ammonium acetate before MS analysis [19] | Use of emitters with <1 μm internal diameter to generate smaller initial droplets with fewer contaminants [19] |

| Handling of Non-Volatile Salts | In-droplet suppression of salt adduction; suitable for physiological salt concentrations [19] | Requires prior removal of non-volatile salts | Reduced metal ion adduction via smaller droplet size [19] |

| Impact on Protein Structure | Minimal perturbation; allows analysis from near-native conditions [19] | Risk of altering protein conformation and dynamics during desalting [19] | Risk of surface-induced unfolding of proteins at the inner emitter surface [19] |

| Key Advantage | High structural fidelity; analysis directly from biological buffers; no sample loss from desalting [19] | Well-established, simple protocol | Simpler setup compared to theta emitters [19] |

| Key Limitation | Requires specialized equipment (theta emitters, dual-channel fluidics); signal-to-noise can be lower than pure ammonium acetate [19] | Potential for sample loss and conformational changes; not suitable for capturing transient intermediates | Emitters are difficult to produce, prone to clogging, and may cause protein unfolding [19] |

| Best Suited For | Pre-steady state kinetics studies in physiologically relevant buffers; limited sample availability | Stable proteins where sample loss is not critical; routine analysis | Analyses where simple setup is prioritized and emitter challenges can be managed |

The experimental data demonstrates the quantitative performance of this technology. In one study, the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios of protein ions of interest were significantly improved by adding anions with low proton affinity (like bromide or iodide) to the ammonium acetate channel of the theta emitter. This strategy reduces chemical noise by facilitating the removal of sodium ions during droplet formation [19]. Furthermore, the technique has been successfully applied to mass analyze proteins and protein complexes ranging from 14 kDa to 466 kDa directly from physiologically relevant solutions [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Theta Emitter ESI-MS

| Performance Metric | Value/Outcome | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Mass Range | 14 kDa to 466 kDa | Successfully applied to proteins and protein complexes within this mass range [19] |

| Key Enabling Technology | Theta emitters with ~1.4 μm internal diameter [19] | Emitters pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries [19] |

| Signal Enhancement Strategy | Addition of low proton affinity anions (e.g., Br-, I-) to AmAc channel [19] | Anions with 25-34 kcal·mol−1 lower proton affinity than acetate facilitate sodium removal [19] |

| Gas-Phase Activation | Beam-type CID & DDC rf-heating in linear ion trap [19] | Two sequential collisional heating methods to remove solvent and salt adducts [19] |

| Method Reproducibility | Increased compared to using ammonium acetate alone [19] | Important for analyzing protein complexes from biological tissues with limited material [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology for Theta Emitter Rapid-Mixing ESI-MS

The following protocol describes the key experimental steps for implementing on-line rapid-mixing ESI-MS using theta emitters, as derived from the literature [19].

A. Theta Emitter Preparation:

- Fabrication: Theta emitters are produced from borosilicate glass capillaries (1.5 mm outer diameter, 1.17 mm inner diameter) using a micropipette puller with specific heat, velocity, and delay settings to achieve a tip with an internal diameter of approximately 1.4 μm [19].

- Loading: The sample dissolved in a biological buffer (e.g., PBS, HEPES) with physiologically relevant concentrations of non-volatile salts is loaded into one channel of the theta emitter. The other channel is loaded with a 199 mM ammonium acetate solution, potentially supplemented with an additive like sodium bromide or sodium iodide (e.g., 10-50 mM) [19].

B. Mass Spectrometry Setup and Data Acquisition:

- Instrumentation: Experiments are performed on a high-mass hybrid mass spectrometer (e.g., a quadrupole/time-of-flight system) modified for advanced activation techniques.

- Electrical Contact: Dual platinum wires are inserted into the open ends of the theta emitter, with each wire making contact with one of the two solutions.

- Ionization: A voltage of 0.80 – 2.0 kV is applied to the platinum wires to generate an electrospray. The voltage is typically started at 800 V and progressively increased until analyte ions are optimally observed [19].

- Gas-Phase Activation: Two sequential, broadband collisional activation methods are employed to remove weakly bound salt and solvent adducts without causing significant dissociation of the biomolecular complex:

- Beam-Type Collision-Induced Dissociation (BTCID): Ions are accelerated into a collision cell filled with nitrogen bath gas (pressure: 6–10 mTorr) [19].

- Dipolar Direct Current (DDC) Offset: A DDC potential is applied across a pair of rods in a linear quadrupole ion trap, displacing ions into regions of higher radiofrequency field. This increases ion velocity and collision energy with the bath gas, providing additional activation for adduct removal [19].

- Data Integration: Mass spectra are acquired by integrating several scans, considering only the duration of the electrospray that yields resolved charge state distributions.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key components of the theta emitter rapid-mixing ESI-MS experiment.

On-line Rapid-Mixing ESI-MS Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Implementing the rapid-mixing theta emitter ESI-MS approach requires specific reagents and instrumentation. The table below details the key research reagent solutions and essential materials for this technique.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Description | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Theta Emitters | Glass emitters with an internal septum creating two channels for on-line mixing immediately before ESI [19]. | ~1.4 μm internal diameter, pulled from borosilicate glass [19]. |

| Ammonium Acetate (AmAc) | Volatile, MS-compatible salt solution used in one channel to promote ionization and replace non-volatile buffers [19]. | 199-200 mM concentration is typical [19]. |

| Low Proton Affinity Anion Additives | Solution additives (e.g., NaBr, NaI) that reduce chemical noise and ionization suppression by mitigating sodium adduction [19]. | Bromide and iodide have 25-34 kcal·mol−1 lower proton affinity than acetate [19]. |

| Dual-Channel Fluidics / Wires | System to independently handle two solutions and apply voltage for ESI. | Dual platinum wires inserted into the theta emitter's channels [19]. |

| High-Mass Range Mass Spectrometer | Mass spectrometer capable of analyzing large biomolecules and complexes. | Hybrid quadrupole/time-of-flight systems are suitable [19]. |

| Gas-Phase Activation Hardware | Instrument components for applying collisional activation to remove salt adducts. | Requires capabilities for beam-type CID and dipolar DC (DDC) activation [19]. |

Electrospray mass spectrometry with on-line rapid-mixing via theta emitters represents a significant innovation for researchers focused on validating kinetic mechanisms using pre-steady state methods. This approach provides a distinct advantage by enabling the direct analysis of proteins and complexes from physiologically relevant buffers, thereby minimizing the risk of altering native conformations or losing precious sample material during desalting. While the requirement for specialized equipment and optimization presents a steeper initial barrier than conventional ESI-MS, the payoff is the ability to obtain structurally faithful data under more biologically relevant conditions. For drug development professionals and scientists studying fast kinetic events, protein-ligand interactions, and complex assembly, this technology offers a powerful and complementary tool to deepen the understanding of dynamic biochemical processes.

Active site titration is a fundamental quantitative biochemical technique used to determine the exact concentration of catalytically active enzyme molecules in a preparation, providing a direct measure of functional enzyme rather than total protein. This method is crucial within the broader context of validating kinetic mechanisms using pre-steady-state methods research, as it establishes the absolute stoichiometry between enzyme molecules and reaction events. Unlike standard activity assays that provide relative measures, active site titration delivers definitive molecular quantification of functional active sites, enabling researchers to distinguish between enzyme preparations with varying proportions of active molecules and calculate true turnover numbers. The methodology is particularly valuable for mechanistic enzymology studies where precise knowledge of active enzyme concentration is required for interpreting pre-steady-state kinetic data and determining fundamental kinetic parameters such as kcat values with accuracy. For drug development professionals working with enzyme targets, this technique provides critical quality control for enzyme preparations and enables accurate determination of inhibitor binding stoichiometries.

Core Principle and Theoretical Basis

The fundamental principle underlying active site titration involves using steady-state kinetic measurements performed at high enzyme concentrations with varying substrate concentrations in the presence of a substrate-regenerating system [20]. Under these specialized conditions, the titration allows direct quantification of active sites by exploiting the stoichiometric relationship between enzyme and substrate during the catalytic cycle. This approach differs fundamentally from conventional enzyme assays that operate under substrate-saturating conditions with enzyme concentrations significantly below substrate levels.

The theoretical foundation relies on the relationship between enzyme concentration and reaction velocity when the enzyme is present at concentrations comparable to or exceeding the Michaelis constant (Km). Under typical steady-state kinetics assumptions, the concentration of enzyme-substrate complex remains constant, but for active site titration, the high enzyme concentration relative to substrate allows direct quantification of functional sites. The method assumes that each active site processes a known number of substrate molecules during the measurement period, enabling back-calculation of active site concentration from the observed reaction progress.

For the titration to be valid, several conditions must be met: the enzyme preparation should ideally contain a homogeneous population of active sites, the substrate-regenerating system must efficiently maintain substrate availability, and the reaction conditions must ensure linearity between the measured signal and product formation. The presence of inactive enzyme molecules or isoenzymes with different catalytic constants can complicate interpretation, requiring appropriate controls and validation experiments.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Active Site Titration vs. Alternative Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Functional Information | Typical Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Site Titration [20] | Steady-state kinetics at high [E] with substrate regeneration | Direct quantification of catalytically active sites | Mechanistic enzymology, pre-steady-state studies, enzyme quality control | Requires high enzyme concentrations; assumes functional homogeneity |

| Pre-Steady-State Burst Kinetics [6] [9] | Rapid kinetic measurement of initial reaction phase | Distinguishes catalytic rate from substrate binding | Single-turnover experiments, characterization of rate-limiting steps | Requires specialized rapid-mixing equipment; complex data analysis |

| Continuous Spectrophotometric Assay [21] | Linear regression of initial velocity from progress curve | Relative activity measurement under specified conditions | Routine enzyme characterization, metabolic pathway analysis | Assumes maintained substrate saturation; only relative activity |

| Kinetic Modeling Approach [21] | Integral analysis of complete progress curve using Michaelis-Menten kinetics | Maximum enzyme activity regardless of linearity | In vitro enzyme characterization, assay optimization | Requires detailed reaction mechanism knowledge |

Technical Comparison of Implementation Requirements

| Parameter | Active Site Titration | Rapid Quench-Flow | Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Resolution | Seconds to minutes | Milliseconds [6] | Milliseconds [9] |

| Enzyme Concentration | High (for titration) [20] | High (stoichiometric) [9] | Standard assay concentrations |

| Equipment Requirements | Standard spectrophotometer with regenerating system | Specialized rapid quench instrument [6] | Stopped-flow spectrometer [9] |

| Information Obtained | Active site concentration | Individual rate constants [9] | Optical changes during reaction |

| Sample Consumption | Moderate | High [9] | Low to moderate |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Active Site Titration Protocol for ATPase Enzymes

Based on the foundational work with myosin ATPase, the following protocol outlines the core methodology for active site titration [20]:

Principle: The titration involves steady-state kinetic measurements at high enzyme concentration with varying substrate concentrations in the presence of a substrate-regenerating system. The high enzyme concentration relative to substrate enables direct quantification of active sites through the stoichiometric relationship during catalysis.

Procedure:

- Prepare a series of reactions with constant high enzyme concentration (sufficient to significantly bind available substrate)