Thermodynamic vs Kinetic Synthesis: A Strategic Framework for Optimized Drug Development

This article provides a comparative analysis of thermodynamic and kinetic synthesis approaches, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Thermodynamic vs Kinetic Synthesis: A Strategic Framework for Optimized Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of thermodynamic and kinetic synthesis approaches, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of binding energetics and reaction rates, examines methodological applications in drug design and materials synthesis, and addresses key challenges in troubleshooting and optimization. By integrating validation strategies and comparative insights, the content offers a practical framework for selecting and refining synthesis pathways to enhance drug efficacy, selectivity, and development efficiency, with direct implications for biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles: Demystifying Energetic and Temporal Drivers of Synthesis

In the rational design of advanced materials and pharmaceutical compounds, the control of molecular interactions is paramount. This process is governed by two fundamental frameworks: thermodynamic control and kinetic control. A thermodynamically controlled synthesis yields the most stable product, while a kinetically controlled synthesis yields the product formed via the pathway with the lowest energy barrier, which may not be the most stable state [1]. The distinction between these scenarios is crucial for increasingly sophisticated nanosynthesis and drug development, where achieving phase-pure materials or high-affinity ligands demands a systematic approach. The Gibbs free energy change, ΔG, serves as the master variable connecting the enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) of a system, providing a predictive framework for the spontaneity and favorability of a process under constant temperature and pressure. The relationship is summarized by the fundamental equation: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS [2] [3] [4]. This article provides a comparative analysis of how this thermodynamic imperative guides synthesis strategies and experimental characterization, with a specific focus on its application for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Thermodynamic Principles and the Governing Equation

The Gibbs free energy represents the energy available in a system to do work and is the ultimate determinant of process spontaneity [2] [5]. The analysis of its components reveals the driving forces behind molecular interactions.

- Spontaneity and Favorability: A spontaneous process, termed thermodynamically favorable, occurs when ΔG is negative (ΔG < 0). Conversely, a positive ΔG (ΔG > 0) indicates a non-spontaneous process, and ΔG = 0 signifies equilibrium [2] [5].

- Enthalpy (ΔH): The enthalpy change represents the heat exchange of the system with its surroundings at constant pressure. A negative ΔH (exothermic) favors spontaneity by releasing heat, while a positive ΔH (endothermic) opposes it [5].

- Entropy (ΔS): The entropy change quantifies the disorder or the number of accessible microstates in a system. A positive ΔS (increase in disorder) favors spontaneity, whereas a negative ΔS (increase in order) opposes it [5].

- The Temperature Multiplier: The entropic contribution to ΔG is scaled by the absolute temperature (T). This means that entropy becomes a progressively more dominant factor in determining spontaneity as temperature increases [2].

The interplay between ΔH and ΔS leads to four distinct scenarios for reaction spontaneity, which are critical for designing synthesis conditions.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Favorability Based on ΔH and ΔS

| ΔH | ΔS | ΔG = ΔH - TΔS | Thermodynamic Favorability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (Exothermic) | Positive (Entropy Increase) | Always Negative | Spontaneous at all temperatures |

| Positive (Endothermic) | Negative (Entropy Decrease) | Always Positive | Non-spontaneous at all temperatures |

| Negative (Exothermic) | Negative (Entropy Decrease) | Negative at low T | Spontaneous at low temperatures |

| Positive (Endothermic) | Positive (Entropy Increase) | Negative at high T | Spontaneous at high temperatures |

For researchers, this framework is indispensable. For instance, an enthalpy-driven reaction is one that is spontaneous due to a strongly negative ΔH, even if ΔS is slightly negative (as long as T is low). An entropy-driven reaction is spontaneous due to a strongly positive ΔS, even if ΔH is positive (as long as T is sufficiently high) [5]. A classic example of an entropy-driven process is the dissolution of sodium nitrate (NaNO₃), which is endothermic yet spontaneous at room temperature because the entropy increase from breaking the ordered crystal lattice into mobile aqueous ions overcomes the unfavorable enthalpy change [5].

Comparative Analysis: Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Synthesis Approaches

The choice between thermodynamic and kinetic control is a fundamental strategic decision in synthesis, with direct implications for product purity, morphology, and pathway.

Thermodynamic Control in Synthesis

Thermodynamically controlled synthesis aims to produce the most stable product, which is the state with the lowest Gibbs free energy. This approach relies on allowing the system sufficient time and energy to reach equilibrium. A powerful application of this principle is the Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) framework for aqueous materials synthesis [6].

- The MTC Hypothesis: This strategy posits that phase-pure synthesis of a target material is optimized when the difference in free energy (ΔΦ) between the target phase and its most stable competing phase is maximized. This condition is described by the equation: ΔΦ(Y) = Φtarget(Y) - min(Φcompeting(Y)) where Y represents intensive variables like pH, redox potential (E), and ion concentrations [6].

- Predictive Power: By computationally maximizing ΔΦ, researchers can identify a specific "sweet spot" in the thermodynamic parameter space (e.g., a specific pH and potential) that minimizes the kinetic formation of by-products, rather than just targeting a broad stability region from a traditional phase diagram [6].

- Experimental Validation: Systematic synthesis of LiIn(IO₃)₄ and LiFePO₄ confirmed that phase-pure products were only obtained at conditions predicted by the MTC criteria, even when other conditions were within the thermodynamic stability region of the target phase [6].

Kinetic Control in Synthesis

Kinetically controlled synthesis exploits the fact that the product with the lowest activation energy (fastest formation kinetics) forms first, even if it is not the thermodynamic ground state. This often requires carefully controlled reaction conditions to prevent the kinetically trapped product from converting to the more stable thermodynamic product over time [1]. In nanosynthesis, this approach can yield sophisticated nanostructures and hybrid materials that are not the absolute most stable configurations but have desirable functional properties [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Thermodynamic and Kinetic Synthesis Approaches

| Aspect | Thermodynamic Control | Kinetic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Principle | Global free energy minimum (ΔG < 0) | Lowest activation energy pathway |

| Target Product | Most stable phase | Fastest-forming phase |

| Reaction Conditions | Often reversible, longer time, higher temperature | Often irreversible, shorter time, lower temperature |

| Key Parameter | ΔG of the final product | ΔG of the transition state (activation energy) |

| Primary Outcome | Equilibrium, stable product | Metastable, potentially complex structures |

| Application Example | Phase-pure synthesis via MTC [6] | Formation of sophisticated nanostructures [1] |

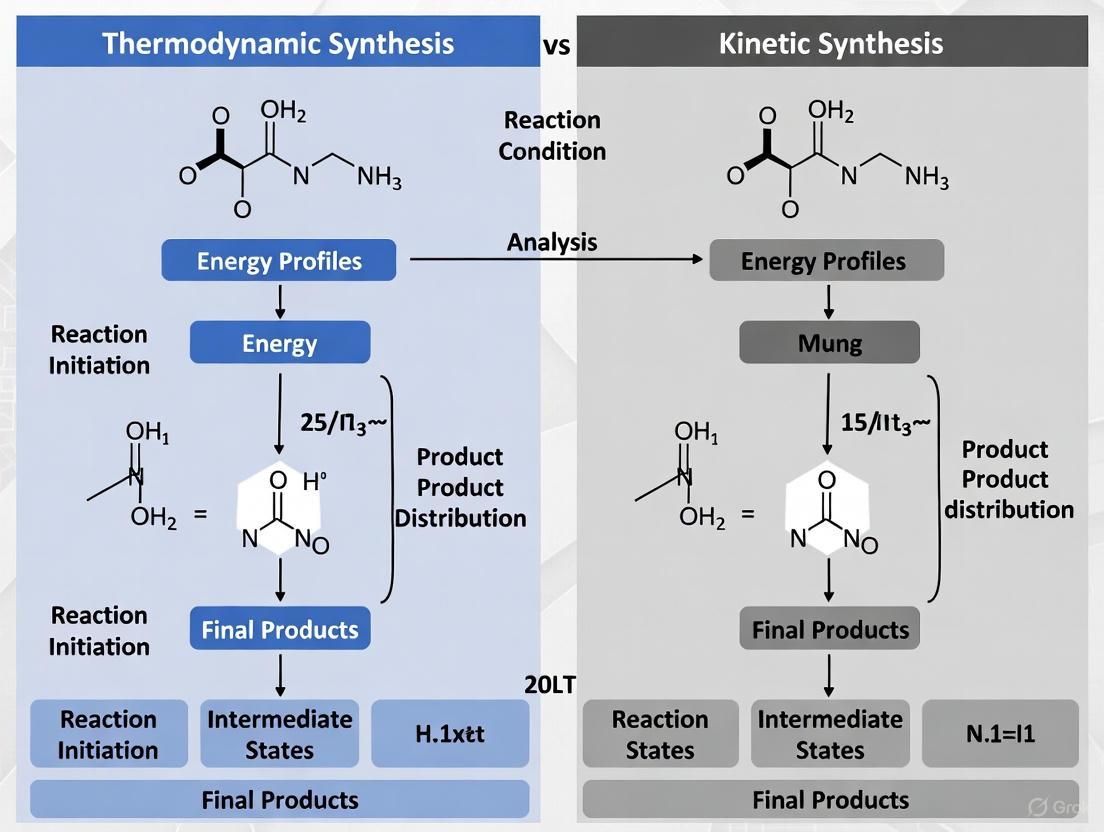

Diagram 1: Energy landscape showing thermodynamic vs kinetic control.

Experimental Protocols for Thermodynamic Profiling

Accurately measuring the thermodynamic parameters of molecular interactions is essential for rational design in fields like drug discovery. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a key experimental technique that provides a complete thermodynamic profile in a single experiment [7].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Protocol

ITC directly measures the heat released or absorbed when two molecules interact, allowing for the determination of binding affinity (KD), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) [7].

- Instrumentation and Setup: A microcalorimeter consists of a reference cell (typically filled with water or buffer) and a sample cell. The sample cell contains one binding partner (e.g., a protein), and a stirring syringe holds the other partner (the ligand) [7].

- Titration and Data Collection: The ligand is injected into the sample cell in a series of small aliquots (e.g., 0.5-2 μL). Each injection results in a heat pulse that is measured by the instrument to maintain zero temperature difference between the cells. The heat per injection is integrated over time and normalized for concentration [7].

- Data Analysis: The resulting titration curve (kcal/mol of injectant vs. molar ratio) is fitted to an appropriate binding model. This analysis directly yields the enthalpy change (ΔH) and the association constant (KA = 1/KD). The Gibbs free energy change is then calculated as ΔG = -RT ln(KA), and the entropic contribution is derived from the relationship ΔS = (ΔH - ΔG)/T [3] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions in thermodynamic profiling experiments like ITC.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Profiling

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Macromolecule (e.g., protein) | The primary binding partner immobilized in the sample cell; purity is critical to avoid spurious binding signals. |

| Lyophilized Ligand | The titrating binding partner; requires high purity and accurate solubilization in a matched buffer. |

| Matched Buffer Solution | The solvent for both macromolecule and ligand; must be identical to prevent heat effects from dilution or mixing mismatches. |

| Reference Solution (e.g., water) | Fills the reference cell to establish a baseline for differential heat measurement. |

| Standard Calf Thymus DNA | (Optional) Used in validation and performance testing of the ITC instrument. |

Application in Drug Design: Interpreting Energetic and Entropic Contributions

In drug discovery, understanding the breakdown of ΔG into ΔH and ΔS provides deep insight into the molecular forces driving ligand binding and offers a roadmap for lead optimization [3] [7].

- Enthalpy-Driven Binding (ΔH < 0): This typically indicates strong, specific interactions such as the formation of hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and other short-range interactions between the ligand and its target. A highly negative ΔH is often associated with strong binding affinity and selectivity [3] [7].

- Entropy-Driven Binding (TΔS > 0): This often results from the hydrophobic effect, where the release of ordered water molecules from the binding pocket and the ligand upon complex formation increases the system's disorder. It can also arise from a release of conformational strain [3].

- Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation: A common phenomenon in drug design where a favorable change in enthalpy (more negative ΔH) is offset by an unfavorable change in entropy (more negative TΔS), or vice versa. This compensation can explain why intensive optimization of a lead compound's binding interactions sometimes yields only modest improvements in the overall binding affinity (ΔG) [3]. Retrospective analyses show that first-in-class drugs are often entropically driven, while best-in-class optimizations tend to achieve stronger enthalpic binding [3].

The interpretation can be further refined by computational methods that decompose the "full" thermodynamic properties into "reduced" ligand-surrounding terms. This excludes the exactly compensating energy and entropy changes within the protein or solvent, which cancel out and do not contribute to affinity. These reduced properties converge more readily in simulations and provide clearer insights for optimizing ligand interactions [3].

The thermodynamic parameters ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS are not abstract concepts but practical tools that guide the synthesis of new materials and the development of therapeutic drugs. The choice between a thermodynamic synthesis strategy, which seeks the global energy minimum, and a kinetic strategy, which traps a metastable state, depends on the target product and its application. Experimental techniques like ITC empower researchers to move beyond simple affinity measurements and deconstruct the driving forces of molecular interactions. As the field advances, frameworks like Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) for synthesis and the analysis of reduced thermodynamic terms for drug binding are providing a more nuanced and powerful understanding of the thermodynamic imperative, enabling more rational and predictive design across the chemical sciences.

In both synthetic chemistry and pharmaceutical development, the traditional focus on thermodynamic stability—quantified by parameters like binding affinity (Kd) or equilibrium constants—is increasingly being complemented by a crucial kinetic dimension. This paradigm shift recognizes that the rates of reactions, including the formation and breakdown of drug-target complexes, are often more predictive of real-world outcomes than equilibrium measurements alone [8] [9]. Kinetic control refers to directing reactions toward products that form most rapidly, characterized by lower activation energies, rather than those that are most thermodynamically stable [10] [11]. This principle operates across scales, from determining the selectivity of organic synthesis reactions to dictating how long a drug molecule remains bound to its protein target in the body.

The concept of drug-target residence time (the reciprocal of the dissociation rate constant, 1/koff) has emerged as a particularly critical kinetic parameter in pharmaceutical research [8] [9]. Unlike thermodynamic affinity which is measured at equilibrium, residence time provides information about target occupancy under the non-equilibrium conditions of living systems, where drug concentrations fluctuate constantly [9]. Understanding and optimizing this parameter requires a fundamental grasp of transition state theory—the recognition that the energy barrier between reactants and products, not just the relative stability of endpoints, dictates reaction rates and pathways [8].

This comparative analysis examines how kinetic principles govern molecular outcomes across chemical and biological contexts, providing researchers with a framework for intentionally designing reactions and therapeutic compounds with desired kinetic profiles.

Fundamental Principles: Kinetic Versus Thermodynamic Control

Theoretical Foundations

In chemical reactions offering multiple potential products, the final composition of the product mixture depends critically on whether the system is under kinetic or thermodynamic control. Under kinetic control, the product distribution is determined by the relative rates of formation of different products, with the fastest-forming product dominating. This typically occurs when reactions are irreversible or when product equilibration is slow compared to the reaction time [11]. In contrast, thermodynamic control prevails when the reaction is reversible and equilibrium is established within the allotted time, favoring the most stable product [11].

The distinction fundamentally arises from the relationship between a reaction's transition state (kinetic control) and its final product state (thermodynamic control). The kinetic product forms faster because it has a lower activation energy barrier (ΔG‡), while the thermodynamic product is more stable because it has a lower overall free energy (ΔG) [10]. A classic illustration of this dichotomy appears in the protonation of enolate ions, where the kinetic product is the enol and the thermodynamic product is the more stable ketone or aldehyde [11].

Comparative Analysis: Key Differentiating Factors

Table 1: Characteristics of Kinetic versus Thermodynamic Control

| Factor | Kinetic Control | Thermodynamic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Principle | Relative rates of product formation [10] [11] | Relative stability of products [10] [11] |

| Reaction Conditions | Low temperatures, irreversible conditions, fast reactions [11] [12] | Higher temperatures, reversible conditions, longer reaction times [11] |

| Product Outcome | Forms less stable product with lower activation energy [11] | Forms more stable product with lowest overall free energy [11] |

| Selectivity Basis | Difference in transition state energies (ΔΔG‡) [11] | Difference in product stabilities (ΔΔG) [11] |

| Time Dependence | Product ratio changes with time until reactants consumed [11] | Product ratio constant at equilibrium [11] |

| Typical Applications | Irreversible reactions, asymmetric synthesis, trapping intermediates [11] [12] | Reversible reactions, equilibrium-driven processes [11] |

Energy Landscape Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental energy relationships that distinguish kinetic from thermodynamic control in a reaction system where two competing products (A and B) can form from the same reactants:

Diagram Title: Energy Landscape for Kinetic vs Thermodynamic Control

This energy diagram visually represents why Product A forms faster under kinetic control (lower activation energy Eₐ), while Product B is more stable under thermodynamic control (lower overall free energy). The relative heights of the transition states (TS A and TS B) determine the kinetic preference, while the relative depths of the product wells determine the thermodynamic preference [10] [11].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Techniques for Kinetic Analysis in Chemical Synthesis

Determining whether a reaction is under kinetic or thermodynamic control requires experimental protocols that probe the time-, temperature-, and conditions-dependence of product distributions. For organic synthesis applications, particularly in enolate chemistry, the following standardized approach can be employed:

Protocol: Determining Kinetic vs Thermodynamic Enolate Formation

Reaction Setup: Prepare a solution of the unsymmetrical ketone (e.g., 2-methylcyclohexanone) in an anhydrous aprotic solvent (THF or ether) under inert atmosphere [12].

Base Selection and Addition:

- For kinetic control: Use a strong, sterically hindered base such as lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) at low temperature (-78°C). Add the base to the ketone solution rapidly [12].

- For thermodynamic control: Use a weaker, less sterically hindered base such as lithium enolate at higher temperature (0°C to room temperature). Allow the system to reach equilibrium [12].

Trapping and Analysis: After enolate formation, trap with trimethylsilyl chloride (TMSCl) or methyl iodide. Analyze the ratio of regioisomeric enol ethers or alkylated products using GC-MS or NMR spectroscopy [12].

Time and Temperature Studies: Monitor product distribution as a function of time and at different temperatures. Under kinetic control, the product ratio remains constant after initial formation. Under thermodynamic control, the product ratio changes over time toward the more stable product [11].

Methods for Determining Drug-Target Binding Kinetics

In drug discovery, several biophysical techniques enable the quantification of binding kinetics parameters (kon and koff), which define drug-target residence time:

Protocol: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for Binding Kinetics

Immobilization: Immobilize the purified target protein on a sensor chip surface using standard amine-coupling or capture techniques [8].

Binding Experiments: Inject a range of drug concentrations over the chip surface in a continuous flow system. Monitor the association phase in real-time [8].

Dissociation Phase: Switch to buffer flow without drug to monitor dissociation of the drug-target complex [8].

Data Analysis: Fit the association and dissociation phases globally to a suitable binding model to extract kon and koff values. Calculate residence time as 1/koff [8].

Alternative Methods: Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) can provide kinetic parameters alongside thermodynamic data, while stopped-flow fluorescence techniques offer rapid kinetics measurement for faster binding events [13]. Advanced computational approaches, including molecular dynamics simulations enhanced by metadynamics and machine learning, can predict unbinding pathways and rates, particularly valuable for systems with very long residence times [14] [13].

Applications Across Domains: Comparative Case Studies

Organic Synthesis Applications

The principle of kinetic versus thermodynamic control manifests across various reaction classes in organic synthesis, with significant implications for product selectivity:

Table 2: Kinetic vs Thermodynamic Control in Organic Reactions

| Reaction Type | Kinetic Product | Thermodynamic Product | Controlling Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diels-Alder Reaction [11] | endo adduct (less stable) | exo adduct (more stable) | Low temperature (kinetic), high temperature with long time (thermodynamic) |

| Enolate Formation [12] | Less substituted enolate | More substituted enolate | Strong bulky base at low T (kinetic), weaker base at higher T (thermodynamic) |

| Electrophilic Addition to Dienes [11] | 1,2-addition product | 1,4-addition product | Low temperature (kinetic), higher temperature (thermodynamic) |

| Asymmetric Synthesis [11] | Enantiomer with lower activation energy | Racemic mixture (equal stability) | Chiral catalysts, irreversible conditions |

A particularly illustrative example comes from Diels-Alder reactions, such as the cycloaddition between cyclopentadiene and furan. At room temperature, kinetic control prevails and the less stable endo isomer predominates due to favorable orbital interactions in the transition state. However, at elevated temperatures (81°C) with extended reaction times, the system reaches equilibrium and the more stable exo isomer becomes the major product [11].

Drug Discovery Applications

In pharmaceutical research, the kinetic dimension profoundly impacts drug efficacy and selectivity, exemplified by these case studies:

Table 3: Kinetic Parameters for Selected Drug-Target Interactions

| Target | Drug/Inhibitor | Residence Time | Kd (Affinity) | Kinetic Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR Kinase [9] | Gefitinib | <14 min | 0.4 nM | Simple one-step binding |

| EGFR Kinase [9] | Lapatinib | 430 min | 3 nM | Two-step induced fit |

| Btk Kinase [8] | Pyrazolopyrimidine 9 | 167 hr | N/A | Reversible covalent |

| S. aureus FabI [8] | PT119 | 12.5 hr | N/A | Substrate binding loop ordering |

| μ-Opioid Receptor [14] | Classical opioids | Minutes to hours | Variable | GPCR conformational selection |

The comparison between gefitinib and lapatinib binding to EGFR kinase demonstrates that affinity (Kd) alone does not predict residence time. Despite having slightly weaker affinity, lapatinib has a approximately 30-fold longer residence time than gefitinib, contributing to its differentiated clinical profile [9].

The following diagram illustrates how residence time translates to differential target occupancy in a dynamic physiological system:

Diagram Title: Residence Time Impact on Drug Action

This diagram illustrates the dynamic relationship between pharmacokinetics, binding kinetics, and pharmacological effect. Drugs with longer residence times maintain target occupancy even after systemic drug concentrations decline, potentially enabling less frequent dosing and improved efficacy [8] [9].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful investigation and application of kinetic principles requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following toolkit summarizes essential resources for research in this domain:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterically Hindered Strong Bases [12] | Kinetic enolate formation | Bulky, strong bases that deprotonate rapidly at accessible positions | Lithium diisopropylamide (LDA), Potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (KHDMS) |

| Weak Protic Solvents/Solutions [11] | Thermodynamic enolate formation | Allows equilibration to more stable enolate | Lithium enolate in THF, Alcohol/water mixtures |

| SPR Sensor Chips [8] | Drug-target binding kinetics measurement | Functionalized surfaces for protein immobilization | CM5 chips (carboxymethylated dextran), NTA chips (His-tag capture) |

| Transition State Analogs [8] | Prolong drug-target residence time | Mimic transition state geometry for tight binding | Diphenyl ether-based FabI inhibitors, Purine nucleoside phosphorylase inhibitors |

| Molecular Simulation Software [14] [13] | Predicting unbinding pathways and rates | Enhanced sampling algorithms | Metadynamics, Steered molecular dynamics, Markov state models |

| Covalent Warheads [8] | Irreversible or slowly-reversible target inhibition | Chemo-reactive groups that form covalent bonds | Acrylamides, α,β-unsaturated carbonyls, Acalabrutinib derivatives |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that the kinetic dimension provides a critical complementary perspective to traditional thermodynamic approaches across chemical and pharmaceutical domains. In synthetic chemistry, intentional manipulation of kinetic versus thermodynamic control enables selective formation of desired products that might be inaccessible under equilibrium conditions. In drug discovery, targeting kinetic parameters—particularly drug-target residence time—offers a pathway to optimize therapeutic efficacy and selectivity even when thermodynamic affinity optimization reaches diminishing returns.

The strategic implication for researchers is clear: comprehensive molecular optimization requires characterization of both thermodynamic and kinetic parameters. Relying solely on equilibrium measurements provides an incomplete picture that may fail to predict behavior in dynamic systems. As technological advances make kinetic characterization increasingly accessible—through improved biophysical instruments, sophisticated computational methods, and standardized kinetic screening protocols—integrating this kinetic dimension into research workflows will become progressively more essential for success in both chemical synthesis and pharmaceutical development.

The optimization of binding affinity represents a central challenge in rational drug design. Traditionally, this process has been guided primarily by the binding affinity (Kd) or the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG), which dictates the spontaneity of the drug-target interaction [15]. However, the pursuit of increasingly sophisticated therapeutics has revealed that this single metric provides an incomplete picture of the binding event. The recognition that ΔG factorizes into two fundamental components—the enthalpy change (ΔH) and the entropy change (TΔS)—has shifted the paradigm toward a more nuanced thermodynamic optimization strategy [16] [15]. This relationship is captured by the fundamental equation: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS.

Within this framework, Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation (EEC) emerges as a critical, albeit often frustrating, phenomenon. EEC describes the tendency for changes in ΔH to be partially or fully offset by opposing changes in TΔS (and vice versa), resulting in a much smaller than expected net change in ΔG [17] [18]. For the medicinal chemist, this can manifest as a carefully engineered hydrogen bond that provides a favorable enthalpic gain (negative ΔH) being completely nullified by a concomitant loss of conformational entropy, yielding no net improvement in affinity [17]. This comparative analysis examines the roles of thermodynamic and kinetic optimization in drug discovery, with a specific focus on navigating the pervasive challenge of EEC to drive the design of high-quality clinical candidates.

Understanding Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation

Fundamental Principles and Manifestations

Enthalpy-entropy compensation is a specific example of the broader "compensation effect," observed as a linear relationship between the enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) changes for a series of closely related chemical reactions or binding events [19]. The underlying principle is that a strengthening of interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces) typically leads to a more favorable (negative) ΔH but often concurrently restricts molecular motion, resulting in a less favorable (negative) change in ΔS [18].

This phenomenon is widely associated with processes occurring in aqueous solutions, particularly those involving biological macromolecules [18]. Water plays a pivotal role; the cooperative nature of its three-dimensional hydrogen-bonded network means that the creation of a cavity for a solute and the subsequent turning on of solute-water interactions are intimately linked, often giving rise to compensatory thermodynamic effects [18]. In drug discovery, EEC is frequently encountered during the optimization of a congeneric series of compounds, where structural modifications lead to significant changes in ΔH and TΔS but disappointingly small changes in the overall binding free energy, ΔG [17].

A Critical Examination of the Evidence

The prevalence and severity of EEC remain subjects of active debate. Calorimetric studies, particularly those using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), often provide apparent evidence of compensation. A meta-analysis of protein-ligand binding thermodynamics revealed a plot of ΔH versus TΔS with a slope near unity, suggesting a severe form of compensation where enthalpic gains are entirely offset by entropic penalties [17]. Severe cases have been documented; for instance, introducing a hydrogen bond acceptor into an HIV-1 protease inhibitor yielded a 3.9 kcal/mol enthalpic gain that was fully compensated by an entropic loss, resulting in zero net affinity gain [17].

However, a critical evaluation of the evidence suggests that the case for severe, universal compensation may be overstated. A significant challenge lies in the large magnitude of and correlation between errors in experimental measurements of ΔH and TΔS [17]. Furthermore, some observed compensation may be a statistical artifact rather than a true physical phenomenon. Analyses indicate that the observed linear correlations can be sensitive to the width of the free energy window under study, and derived parameters like the "compensation temperature" can sometimes be unrealistic or even negative, leading to questions about the physicochemical certainty of some reported EEC correlations [20]. Therefore, while a limited form of compensation is likely common, the evidence for a severe, pervasive form that universally frustrates ligand optimization is weaker when experimental uncertainties are properly considered [17].

Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Optimization: A Comparative Analysis

The binding interaction between a drug and its target can be described through two complementary lenses: thermodynamics and kinetics. Thermodynamics informs on the spontaneity and final state of the binding interaction (affinity, Kd), while kinetics describes the time-dependent pathway to reach that state (rates, kon and koff) [15]. A comprehensive optimization strategy must consider both.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Thermodynamic and Kinetic Optimization Approaches

| Aspect | Thermodynamic Optimization | Kinetic Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Final bound state equilibrium; Binding Affinity (Kd) [15] | Time-dependent pathway; association/dissociation rates (kₒₙ, kₒff) [16] [15] |

| Governed by | Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS) [15] | Energy landscape of the binding pathway [16] |

| Key Metrics | ΔG, ΔH, TΔS, Enthalpic Efficiency (EE) [15] | Residence Time (τ = 1/kₒff), Association Rate (kₒₙ) [16] [15] |

| Role of EEC | Central challenge; modifications can yield compensatory ΔH/TΔS changes [17] | Indirect; EEC primarily an equilibrium thermodynamic phenomenon |

| Advantages | Provides deep understanding of binding forces (H-bonds, hydrophobic effect) [15] | Directly linked to in vivo efficacy, duration of action, and selectivity [16] |

| Limitations | Susceptible to EEC; does not predict duration of action [17] [15] | More complex to measure and model; requires specialized techniques [16] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for employing thermodynamic and kinetic strategies in lead optimization, highlighting how to navigate EEC.

The Kinetic Optimization Paradigm

When thermodynamic optimization is frustrated by EEC, focusing on binding kinetics provides a powerful alternative pathway. The dissociation rate constant (koff) and its inverse, the target residence time (τ), have emerged as critically important parameters for in vivo efficacy [16]. A drug with a long residence time remains bound to its target for an extended period, which can translate into a longer duration of pharmacological action, even after systemic drug concentrations have declined [16] [15].

A classic example is the bronchodilator tiotropium. While it binds to multiple muscarinic receptor subtypes, it dissociates ten times slower from the M3 receptor than from the M2 receptor, conferring its clinical selectivity and enabling once-daily dosing [16]. This demonstrates that kinetic selectivity, independent of pure thermodynamic affinity, can be a decisive factor in clinical success. Optimizing residence time can be achieved by either stabilizing the final drug-target complex (lowering its energy) or by destabilizing the transition state for dissociation, both strategies that can circumvent the thermodynamic constraints imposed by EEC [15].

Essential Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Accurately measuring the parameters that define binding events is a prerequisite for successful optimization. The following workflows detail the core experimental protocols.

Protocol 1: Thermodynamic Profiling via Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC is the gold-standard technique for full thermodynamic characterization because it directly measures the heat change (enthalpy, ΔH) of a binding interaction in a single experiment [15]. From one titration, ITC directly provides the binding constant (Ka), the stoichiometry (n), and ΔH. The entropy change (ΔS) is then calculated using the fundamental relationship ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, where ΔG is derived from Ka [15].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic and Kinetic Profiling

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Highly Purified Target Protein | Ensures accurate stoichiometry and measurement; absence of contaminants is critical for clean data. |

| Ligand Compound Solution | The drug candidate or inhibitor; requires high purity and precise solubilization (e.g., DMSO stock). |

| ITC Assay Buffer | Must be matched perfectly between protein and ligand samples to avoid artifactual heat signals from dilution. |

| SPR Sensor Chip | The solid support (e.g., CM5 chip) onto which the protein target is immobilized for kinetic analysis. |

| Running Buffer (for SPR) | Maintains a consistent environment during analyte flow; crucial for minimizing nonspecific binding. |

| Regeneration Solution (for SPR) | A solution that dissociates bound ligand from the immobilized protein without denaturing it for chip reuse. |

Protocol 2: Kinetic Profiling via Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

SPR is a label-free technique that excels at quantifying the kinetics of binding. It operates by detecting changes in the refractive index on a sensor surface where the target protein is immobilized. As ligand flows over the surface, binding and dissociation cause mass changes, allowing for real-time monitoring [15].

A typical SPR experiment involves:

- Immobilization: The purified protein is covalently coupled to the dextran matrix of a sensor chip.

- Association Phase: The ligand solution is flowed over the chip surface at a defined concentration, and the increasing signal (Response Units, RU) is monitored to determine the association rate constant (kₒₙ).

- Dissociation Phase: The flow is switched to buffer, and the decay of the signal as the ligand dissociates is monitored to determine the dissociation rate constant (kₒff).

- Regeneration: A mild solution is injected to remove any remaining bound ligand, regenerating the surface for the next cycle. The binding affinity (Kd) can be calculated as kₒff / kₒₙ, and the residence time is simply τ = 1 / kₒff [15]. Modern instruments allow for high-throughput analysis, making kinetic profiling feasible during lead optimization [16] [15].

Practical Applications and Efficiency Metrics in Ligand Design

To guide medicinal chemists toward higher-quality compounds, several efficiency metrics have been developed that move beyond simple potency (IC50 or Kd).

Table 3: Key Efficiency Metrics for Guiding Ligand Optimization

| Efficiency Metric | Calculation | Interpretation & Ideal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Efficiency (LE) | ΔG / NHA* | Measures "bang for the buck"; normalizes affinity by heavy atom count. Ideal: > 0.4 kcal/mol/HA for leads [15]. |

| Lipophilic Ligand Efficiency (LLE) | pKi - LogD | Penalizes high lipophilicity, linked to poor solubility and promiscuity. Ideal: > 7 [15]. |

| Enthalpic Efficiency (EE) | ΔH / NHA | Gauges the efficiency of enthalpic contributions (e.g., H-bonds). Aids in avoiding molecular obesity [15]. |

| Kinetic Efficiency (KE) | τ / NHA | Normalizes the valuable property of residence time by molecular size. Higher is better [15]. |

*NHA = Number of Non-Hydrogen Atoms

These metrics provide crucial guardrails. For instance, pursuing affinity gains solely by adding hydrophobic groups might improve ΔG but will worsen LLE, likely leading to poorer drug-like properties. Similarly, monitoring EE helps ensure that enthalpic gains are achieved efficiently rather than through brute-force increases in molecular weight [15]. When EEC is encountered, shifting focus to optimizing Kinetic Efficiency (KE) offers a productive alternative path.

The comparative analysis of thermodynamic and kinetic optimization approaches reveals that a sophisticated drug design strategy must be multi-dimensional. While thermodynamics provides deep insight into the nature of the binding forces, its utility can be limited by the enigmatic and often confounding phenomenon of enthalpy-entropy compensation. Relying solely on affinity measurements can lead to optimization dead-ends where significant chemical modifications yield minimal gains.

The forward-looking path in drug discovery lies in the integrated use of both thermodynamic and kinetic data. Characterizing a lead series with both ITC and SPR provides a comprehensive picture that neither technique can deliver alone. When EEC threatens to halt progress in a thermodynamic optimization cycle, the rational design of compounds with improved target residence time (a kinetic parameter) offers a powerful and clinically validated escape route [16]. Ultimately, escaping the constraints of compensation requires a holistic view of the drug-target interaction, leveraging all available experimental tools to design drugs that are not only potent but also efficient, selective, and effective in vivo.

The synthesis of novel materials and chemical compounds represents a cornerstone of advancement in fields ranging from drug development to energy storage. A fundamental challenge in synthesis lies in navigating the complex interplay between thermodynamic driving forces and kinetic barriers, which collectively determine the final outcome of a chemical reaction. Thermodynamics dictates the inherent stability of products and the ultimate equilibrium state of a system, while kinetics governs the pathway and rate at which that state is approached. The deliberate control over these factors enables researchers to steer reactions toward desired products, whether they are the most stable thermodynamic species or metastable kinetic intermediates with unique properties.

Understanding this balance is not merely an academic exercise; it is a practical necessity for the rational design of synthetic protocols. This comparative guide examines the core principles, experimental methodologies, and computational tools that define thermodynamic and kinetic control in synthesis. By objectively analyzing their applications across different chemical domains, this article provides a framework for researchers to select and optimize synthesis strategies for target molecules and materials, with a particular focus on implications for drug development professionals and materials scientists.

Theoretical Foundations: Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control

Core Principles and Energetics

In a chemical reaction with competing pathways, the final product mixture is determined by whether the reaction is under kinetic or thermodynamic control. The kinetic product is the species that forms fastest, characterized by the lowest activation energy (Ea) for its formation pathway. In contrast, the thermodynamic product is the most stable species, possessing the lowest Gibbs free energy (G°). A reaction will yield the kinetic product when the activation energy barrier to the thermodynamic product is sufficiently high that the system cannot achieve equilibrium within the allotted reaction time. The key differentiator is that kinetic control depends on the rate of product formation, while thermodynamic control depends on the relative stability of the products [11] [21].

The reaction conditions serve as the primary lever for influencing this control. Key factors include [11]:

- Temperature: Low temperatures favor kinetic control by slowing equilibration, while high temperatures favor thermodynamic control by providing the thermal energy needed to overcome activation barriers and reach equilibrium.

- Reaction Time: Short times favor kinetic products, whereas long reaction times allow the system to equilibrate to the thermodynamic product.

- Solvent and Catalysts: These can alter the relative activation energies or stabilities of the transition states and products.

Comparative Energetics Framework

The table below summarizes the key characteristics that distinguish kinetic and thermodynamic control.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control

| Feature | Kinetic Control | Thermodynamic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Factor | Reaction rate & activation energy | Product stability & Gibbs free energy |

| Product Favored | Formed fastest (lowest Ea) | Most stable (lowest G°) |

| Key Influencing Conditions | Low temperature, short reaction time, irreversible conditions | High temperature, long reaction time, reversible conditions |

| Reversibility | Irreversible or slow reversal | Fast equilibration between products |

| Mathematical Relationship | ln([A]t/[B]t) = ln(kA/kB) = -ΔEa/RT [11] |

ln([A]∞/[B]∞) = ln Keq = -ΔG°/RT [11] |

| Typical Outcome | Metastable, often less substituted product | More stable, often more substituted product |

Experimental Evidence and Comparative Analysis

Empirical studies across diverse chemical systems consistently demonstrate the principles of kinetic and thermodynamic control. The following examples and data illustrate how these competing forces manifest in practice.

Case Studies in Organic and Materials Chemistry

Diels-Alder Reactions: A classic example is the reaction of cyclopentadiene with furan, which yields the endo isomer (the kinetic product) at room temperature. The exo isomer (the thermodynamic product) becomes the major product when the reaction is conducted at 81°C for an extended period. The kinetic preference for the endo isomer arises from superior orbital overlap in the transition state, while the thermodynamic stability of the exo isomer stems from its lower steric congestion [11]. A more complex tandem Diels-Alder reaction demonstrated full control, where pincer-type adducts formed exclusively at low temperatures (kinetic) and domino-type adducts (thermodynamic) dominated at elevated temperatures [11].

Synthesis of Layered Oxides: Research into sodium oxides (Na~0.67~MO~2~) reveals complex multistage crystallization pathways. In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction shows that reactions proceed through a series of fast, non-equilibrium metastable phases (O3, O3', P3) before ultimately forming the equilibrium two-layer P2 polymorph. This demonstrates that even when a thermodynamic equilibrium phase is known, kinetic intermediates can dominate the initial stages of solid-state synthesis, influencing the choice of precursors and heating profiles [22].

Electrophilic Additions: The addition of hydrogen bromide to 1,3-butadiene shows a temperature-dependent product distribution. At low temperatures (< Room Temperature), the 1,2-adduct (3-bromo-1-butene) is favored, forming faster as the kinetic product. At higher temperatures, the reaction favors the more stable 1,4-adduct (1-bromo-2-butene) as the thermodynamic product [11].

Quantitative Metrics for Synthesis Optimization

The Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) framework provides a quantitative approach to minimizing kinetic by-products in materials synthesis, particularly in aqueous systems. The hypothesis posits that phase-pure synthesis of a target material is most likely when the difference in free energy (ΔΦ) between the target phase and its most competitive by-product phase is maximized [6].

Table 2: Synthesis Outcomes for LiFePO4 at Different Thermodynamic Conditions

| Synthesis Condition | ΔΦ (kJ/mol) | Observed Phase Purity | Key Competing Phases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition A (Low ΔΦ) | -5.2 | Low (Impure) | Fe~3~(PO~4~)~2~, Li~3~PO~4~ |

| Condition B (Medium ΔΦ) | -12.1 | Medium | Trace Li~3~PO~4~ |

| MTC Condition (High ΔΦ) | -25.8 | High (Phase-Pure) | None Detected |

The empirical validation for MTC comes from two sources: analysis of 331 text-mined aqueous synthesis recipes from the literature, and systematic experimental synthesis of model systems like LiFePO4 and LiIn(IO~3~)~4~. The data confirm that even within the thermodynamic stability region of a target phase (as defined by a traditional Pourbaix diagram), phase-pure synthesis occurs reliably only at conditions where the thermodynamic competition with undesired phases is minimized, corresponding to a maximally negative ΔΦ [6].

Methodologies for Controlling Synthesis Outcomes

Experimental Protocols

1. Protocol for Probing Kinetic and Thermodynamic Products in a Diels-Alder Reaction [11]

- Objective: To isolate both the kinetic (endo) and thermodynamic (exo) adducts from the reaction between cyclopentadiene and furan.

- Materials: Freshly cracked cyclopentadiene, furan, dry toluene, argon atmosphere.

- Procedure:

- Kinetic Product Synthesis: Dissolve furan (1.0 equiv) in toluene under argon and cool to 0°C. Add cyclopentadiene (1.1 equiv) dropwise. Stir at 0°C for 2 hours. Monitor by TLC. The endo-adduct precipitates first and can be collected by vacuum filtration.

- Thermodynamic Product Synthesis: Combine furan and cyclopentadiene in a sealed tube with toluene. Heat at 81°C for 72 hours. Allow the reaction mixture to cool slowly to room temperature. The exo-adduct crystallizes and is collected.

- Analysis: Characterize both products using

^1H NMRand^13C NMRspectroscopy. The endo-isomer typically shows a distinctive upfield shift for the bridgehead hydrogens compared to the exo-isomer.

2. Protocol for Solid-State Synthesis of P2-Layered Sodium Oxide [22]

- Objective: To synthesize the equilibrium P2-Na~0.67~CoO~2~ phase and identify its kinetic metastable intermediates.

- Materials: Na~2~CO~3~, Co~3~O~4~, high-energy ball mill, alumina crucibles, tube furnace.

- Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: stoichiometrically mix Na~2~CO~3~ and Co~3~O~4~ powders. Use a high-energy ball mill for 1 hour to ensure homogeneity.

- In Situ Monitoring: Load the precursor mixture into a capillary for in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction. Heat from room temperature to 900°C at a controlled rate (e.g., 10°C/min) under a flowing oxygen atmosphere.

- Phase Identification: Analyze the time-resolved diffraction patterns to identify the sequence of metastable intermediates (O3, O3', P3) and the temperature at which the equilibrium P2 phase first appears and becomes dominant.

- Analysis: Rietveld refinement of diffraction patterns to quantify phase fractions and lattice parameters as a function of time and temperature.

Visualization of Synthesis Pathways and Energetics

The following diagram illustrates the key concepts and decision pathways involved in controlling synthesis outcomes.

Diagram Title: Energy Landscape and Control Pathways in Chemical Synthesis

This diagram shows the divergent pathways from reactants to kinetic and thermodynamic products. The kinetic pathway has a lower activation energy (Ea) barrier, leading to faster formation of the less stable product. The final outcome is determined by applying specific reaction conditions that favor one control mechanism over the other.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful navigation of kinetic and thermodynamic synthesis requires specific reagents and tools. The following table lists key materials used in the experiments cited in this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesis Control Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclopentadiene | Diene reactant in cycloadditions | Kinetic vs. thermodynamic Diels-Alder reactions [11] |

| Sodium Carbonate (Na~2~CO~3~) | Sodium precursor in solid-state synthesis | Formation of layered sodium oxides (Na~x~MO~2~) [22] |

| Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO~4~) Precursors | Target cathode material | Validation of MTC in aqueous synthesis [6] |

| Sterically Demanding Bases (e.g., LDA) | Selective enolate formation | Favors kinetic enolate in unsymmetrical ketone deprotonation [11] |

| Geopolymer Activator Solutions | Alkaline activation of aluminosilicates | Thermodynamic stability modeling for consistent synthesis [23] |

| In Situ Synchrotron X-ray Diffraction | Real-time phase transformation monitoring | Unraveling crystallization pathways in solid-state reactions [22] |

Emerging Trends and Computational Tools

The field is increasingly moving toward a rational synthesis paradigm, guided by computational prediction. Inverse design strategies are being developed where target material properties are specified first, and optimal synthesis conditions are computed backwards [22] [24].

Computational Prediction of Synthesis: A key development is the use of machine learning pipelines for inverse design. For instance, models can now predict the optimal metal, ligand, precursor masses, solvent volume, and temperature regimes required to achieve target adsorption characteristics in Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). These models incorporate physical constraints like thermodynamics, stoichiometry, and temperature limits to ensure predictions are chemically plausible [24].

Thermodynamic Modeling for Stability: Recent work on geopolymer activator solutions demonstrates how thermodynamic modeling can predict solution stability and optimize synthesis. These models enable dynamic assessment and process design, challenging traditional practices and significantly reducing preparation times from 24 hours to about 1 minute while maintaining consistency [23].

The MTC Framework as a Predictive Tool: The Minimum Thermodynamic Competition framework represents a significant shift from using phase diagrams solely for identifying stability regions to using them as optimization tools. By computing the free energy axis, researchers can identify a single optimal point for synthesis that minimizes kinetic competition, rather than an entire stability region where by-products may still form [6].

The interplay between thermodynamic driving forces and kinetic barriers is a fundamental determinant of synthesis outcomes. As the comparative analysis in this guide demonstrates, neither thermodynamic nor kinetic control is universally superior; their strategic application depends on the target product. Thermodynamic control reliably yields the most stable product, while kinetic control provides access to metastable species with unique properties that are inaccessible at equilibrium.

The future of synthesis control lies in the integrated use of advanced computational tools, high-fidelity thermodynamic models like MTC, and sophisticated real-time characterization techniques. This combined approach enables a shift from empirical, trial-and-error optimization to a predictive and rational design of synthesis pathways. For researchers in drug development and materials science, mastering the balance between thermodynamics and kinetics is not just about controlling a reaction—it is about unlocking the full potential of chemical and materials space to discover and create the functional molecules and materials of the future.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Energetic and Kinetic Strategies in Real-World Scenarios

In the pursuit of novel materials and pharmaceuticals, researchers navigate a fundamental dichotomy: thermodynamic versus kinetic control over synthesis outcomes. A thermodynamically controlled reaction proceeds to the most stable product, the state with the lowest Gibbs free energy. In contrast, a kinetically controlled reaction yields the product that forms most rapidly, which is the one with the lowest activation energy barrier, even if it is not the most stable state [11]. The distinction is critical because the final product mixture depends heavily on reaction conditions; lower temperatures and shorter times typically favor the kinetic product, whereas higher temperatures and longer times allow the system to equilibrate to the thermodynamic product [11]. This comparative guide explores advanced calorimetric tools and complementary methodologies essential for measuring the parameters that define these energetic landscapes—namely, Gibbs free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS)—enabling researchers to strategically steer reactions toward desired outcomes.

Core Calorimetric Measurement Techniques

Calorimetry, the science of measuring heat flow, provides direct insight into the energetic drivers of chemical and biological processes. The principal techniques vary in their operational principles and application domains.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a powerful and widely used method to measure the real-time heat flow associated with molecular binding events. In a typical ITC experiment, one binding partner (ligand) is titrated into a solution containing the other (macromolecule) while the instrument maintains a constant temperature. The instrument records the differential heating power required to keep the sample and reference cells at the same temperature [25]. Each injection produces a peak in the thermogram (see Diagram 1); the integrated area under these peaks yields the total heat for each injection, forming a binding isotherm. Analysis of this isotherm directly provides the enthalpy change (ΔH), binding affinity (KD), stoichiometry (n), and through temperature-dependent studies, the heat capacity change (ΔCp). A significant strength of ITC is its label-free nature and its ability to provide a full thermodynamic profile (ΔG, ΔH, and -TΔS) from a single experiment [25]. Its primary application lies in quantifying biomolecular interactions, such as protein-ligand binding [25].

Indirect Calorimetry

Indirect Calorimetry operates on a different principle, determining energy expenditure in biological systems by measuring gas exchange. Instead of direct heat measurement, it calculates metabolic rate by monitoring oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) [26]. This method is non-invasive and allows for serial measurements in live animals, providing flexibility for sophisticated physiological studies. The raw data is used to calculate the Energy Expenditure (EE), which is crucial for understanding metabolic phenotypes [26]. Modern analysis tools, such as the web-based CalR software, promote rigor and reproducibility by assisting with data wrangling, visualization, and statistical analysis using methods like ANCOVA to account for covariates like body mass [26]. Its main application is in metabolic research and studies of obesity and energy balance [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Calorimetric Techniques

| Feature | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Indirect Calorimetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Principle | Direct measurement of heat flow (power) | Measurement of gas exchange (O₂, CO₂) |

| Primary Measured Parameters | Heat of reaction (ΔH) | Oxygen Consumption Rate (VO₂), Respiratory Exchange Ratio (RER) |

| Derived Thermodynamic Parameters | ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, KA/KD, n, ΔCp | Energy Expenditure (EE) |

| Key Applications | Biomolecular interactions, drug discovery | Whole-animal physiology, metabolic studies |

| Sample Throughput | Low (typically 1-2 samples per run) | Medium (simultaneous multi-animal cages) |

Performance Benchmarking of Calorimetric Instruments

The selection of a calorimeter is critical, as instrument performance can directly impact the quality and reliability of the derived thermodynamic data. A comparative study of three commercial calorimeters—the Thermometric TAM, THT µRC, and Setaram HSDSC III—highlighted this point. The study used the base-catalyzed hydrolysis of methyl paraben as a test reaction to quantitatively compare the returned values for the rate constant, enthalpy of reaction, and activation energy [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Commercial Calorimeters

| Instrument | Key Characteristics | Reported Enthalpy (ΔH) | Reported Rate Constant (k) | Statistical Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermometric TAM | High-sensitivity, long equilibration time [27] | Statistically similar across all instruments [27] | Reference value | High precision for k and Ea [27] |

| THT µRC | --- | Statistically similar across all instruments [27] | Not significantly different from TAM [27] | Less precise than TAM for k and Ea [27] |

| Setaram HSDSC III | Lower-sensitivity, short equilibration time [27] | Statistically similar across all instruments [27] | Significantly different from TAM and µRC [27] | Less precise than TAM for k and Ea [27] |

The statistical analysis revealed that while all instruments returned statistically similar enthalpy data, their precision in determining kinetic parameters like the rate constant and activation energy varied significantly [27]. This underscores the importance of instrument selection based on the experimental goals, whether they prioritize high-precision kinetics or robust thermodynamic profiling.

Advanced Experimental Protocols in Calorimetry

Protocol: Global Analysis of ITC Data for Proton-Linked Binding

Proton-linked binding, where a molecular interaction is coupled to the gain or loss of a proton, is a common phenomenon that can obscure the intrinsic thermodynamics of the binding interface. The following protocol outlines how to use global ITC analysis to deconvolute these effects, using the interaction between carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) and the inhibitor trifluoromethanesulfonamide (TFMSA) as a model system [25].

Step 1: Experimental Design and Titration

- Prepare the protein (CAII) and ligand (TFMSA) solutions in a series of buffers with different ionization enthalpies (ΔHion). Common buffers include phosphate (ΔHion ~ 4.7 kJ/mol), Tris (ΔHion ~ 47 kJ/mol), and MOPS (ΔHion ~ 22 kJ/mol).

- Perform separate ITC titrations for each buffer condition. The standard setup involves placing CAII in the sample cell and titrating with TFMSA from the syringe. Maintain a constant temperature throughout all experiments.

Step 2: Raw Thermogram Integration with NITPIC

- Export the raw power-versus-time data from the ITC instrument.

- Process the thermograms using the public-domain software NITPIC, which employs a global peak-shape analysis and regularization to integrate the injection peaks objectively and without bias [25]. This step converts the raw data into a series of integrated heats for each injection and provides error estimates for each data point.

Step 3: Global Analysis in SEDPHAT

- Import the integrated isotherms (from all buffer conditions) into the global analysis software SEDPHAT.

- Fit the data globally to a "proton-linked binding" model. This model accounts for the thermodynamic cycle involving the intrinsic binding constant (KA,int), the intrinsic binding enthalpy (ΔH°int), and the protonation constants and enthalpies for the free protein and the protein-ligand complex [25].

- The global analysis will return the intrinsic thermodynamic parameters, which are no longer confounded by the buffer-dependent protonation events.

Step 4: Visualization with GUSSI

- Use the GUSSI software to create publication-quality graphs of the experimental data, the global fit, and the residuals [25].

Protocol: Using Indirect Calorimetry for Metabolic Phenotyping

This protocol describes the workflow for conducting and analyzing energy expenditure experiments in mice, a common application of indirect calorimetry.

Step 1: Experimental Setup and Data Acquisition

- House mice in the calorimetry system (e.g., a CLAMS, Promethion, or PhenoMaster setup) with controlled temperature and light cycles.

- Record the fundamental data streams: O2 concentration, CO2 concentration, food intake, water intake, and animal activity over the desired period (typically 24-72 hours).

- Measure body composition (e.g., using DEXA or NMR) to determine lean and fat mass.

Step 2: Data Import and Curation in CalR

- Export the raw data files from the manufacturer's software.

- Import the CSV files into the CalR web application. For CLAMS data, CalR will automatically reverse the body weight normalization applied by the system to obtain absolute energy expenditure values [26].

- Assign subjects to their respective experimental groups within the CalR interface.

Step 3: Data Analysis and Statistical Interpretation

- Select the time region of interest for analysis (e.g., the full 24-hour cycle or the dark/light phases separately).

- For energy expenditure analysis, CalR uses a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) or Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) with body mass (or lean mass) as a covariate. This adjustment is critical for comparing energy expenditure between groups of animals with different body compositions [26].

- Examine the results, including plots of the data with the fitted model, to interpret the statistical differences between groups.

Beyond Calorimetry: Integrating Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis for Synthesis

While calorimetry excels at measuring thermodynamic properties, achieving controlled synthesis requires a synergistic understanding of both thermodynamics and kinetics. The formation of kinetic by-products is a major challenge in materials synthesis, as the first phase to nucleate is often the one with the lowest activation barrier, not the most stable phase [6].

The Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) framework is a computational strategy designed to address this. It posits that the optimal synthesis condition for a pure target phase is where the difference in free energy between the target phase and its most stable competing phase is maximized [6]. This is represented by the metric: ΔΦ(Y) = Φk(Y) - mini∈Ic Φi(Y) where Φk is the free energy of the target phase and the second term is the minimum free energy of all competing phases. The goal is to find the synthesis conditions Y* (e.g., pH, redox potential, concentration) that minimize ΔΦ, thereby giving the target phase the largest possible thermodynamic driving force relative to its competitors and reducing the kinetic likelihood of by-product formation [6]. This approach has been validated empirically, showing that literature-reported synthesis recipes for materials like LiFePO4 often cluster near conditions predicted by MTC [6].

Diagram 1: The MTC framework identifies synthesis conditions that maximize the free energy difference (ΔΦ) to the target phase, minimizing kinetic competition from by-products.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials crucial for conducting reliable calorimetric and thermodynamic studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Buffers with Varied ΔHion | Enables deconvolution of protonation effects from intrinsic binding thermodynamics in ITC [25]. | Proton-linked binding studies (ITC). |

| Carbonic Anhydrase II (CAII) & Trifluoromethanesulfonamide (TFMSA) | Well-characterized model system for validating ITC performance and methodology [25]. | Instrument calibration, method development. |

| Methyl Paraben | Standard compound for a test reaction (base-catalyzed hydrolysis) to compare calorimeter performance [27]. | Instrument validation, kinetic studies. |

| High-Purity Gases (O₂, CO₂, N₂) | Create controlled atmospheric environments for indirect calorimetry and as carrier gases [26]. | Metabolic phenotyping (Indirect Calorimetry). |

| Standardized Animal Diet | Provides a consistent nutritional base to minimize confounding variables in metabolic studies [26]. | In vivo energy balance research. |

The strategic choice between thermodynamic and kinetic synthesis pathways hinges on the ability to accurately measure the underlying energetic parameters. As demonstrated, modern calorimetric techniques like ITC and indirect calorimetry provide direct, label-free access to these crucial values, from binding enthalpies to whole-organism energy expenditure. The performance of these instruments varies, necessitating careful selection based on the required sensitivity and precision. Furthermore, the integration of calorimetric data with advanced computational frameworks like Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) represents the cutting edge of materials design. By coupling rigorous experimental protocols—such as global ITC analysis and ANCOVA-treated metabolic data—with these powerful theoretical models, researchers can transcend traditional trial-and-error approaches, rationally designing synthesis conditions to favor either kinetic or thermodynamic products and accelerating the discovery of new functional materials and therapeutics.

In contemporary drug discovery, the detailed characterization of binding mechanisms has evolved from a specialized interest to a fundamental component of lead optimization. Traditional drug discovery primarily relied on equilibrium binding affinity measurements, which provide a thermodynamic perspective but lack temporal resolution of the binding event. High-throughput kinetics has emerged as a transformative approach, enabling the rapid determination of binding and dissociation rates across large compound libraries. This paradigm shift allows researchers to move beyond static affinity measurements toward a dynamic understanding of drug-target interactions [28] [29].

The distinction between thermodynamic and kinetic control is particularly crucial in drug discovery. While thermodynamics determines the ultimate binding affinity, kinetics governs the time-dependent behavior of drug-target interactions—how quickly a drug binds to its target and how long it remains bound [1]. This temporal dimension has profound implications for drug efficacy and duration of action, influencing dosing regimens and therapeutic windows. High-throughput kinetic platforms now span an impressive nine orders of magnitude in temporal resolution, from milliseconds to days, providing comprehensive characterization of drug-target interactions early in the discovery pipeline [28].

Comparative Analysis of High-Throughput Kinetic Platforms

Technology Platforms and Their Applications

The experimental landscape for high-throughput kinetics encompasses diverse technologies, each optimized for specific temporal ranges and sample requirements. These platforms have evolved from specialized, low-throughput methods to robust systems capable of profiling thousands of compounds in a single screen.

Table 1: High-Throughput Kinetic Measurement Platforms

| Technology | Temporal Range | Throughput Capacity | Key Applications | Label Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Stopped-Flow | Milliseconds to seconds | Moderate | Transient kinetics, pre-steady state | Typically labeled |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Seconds to hours | High | Real-time binding kinetics, fragment screening | Label-free |

| Global Progress Curve Analysis | Seconds to hours | Very High | Enzyme inhibitor profiling | Can use labeled or unlabeled |

| Filtration Plate-Based Assays | Minutes to hours | High | Receptor-ligand binding studies | Radioligands or fluorescent labels |

| Jump-Dilution | Hours to days | Moderate | Very slow dissociation kinetics | Label-dependent |

| LC/MS/MS | Variable | High | Universal detection | Label-free |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) has emerged as a particularly versatile technology for high-throughput kinetics. SPR biosensors enable real-time monitoring of molecular interactions without requiring labeling, preserving the native properties of the interacting molecules. This technology provides direct measurement of association rate constants (kon) and dissociation rate constants (koff), from which the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) can be derived [28] [30]. The integration of SPR with automated liquid handling has significantly increased throughput, making it suitable for early-stage compound profiling.

For ultra-high-throughput applications, plate-based methods utilizing radioligands or fluorescent probes remain valuable. These approaches benefit from the infrastructure and automation already established in high-throughput screening (HTS) facilities, leveraging microtiter plates with 96, 384, 1536, or even 3456 wells [31]. Recent innovations have enhanced these assays through improved detection methods and data analysis pipelines, enabling robust kinetic measurements alongside traditional endpoint data.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

A critical consideration in implementing high-throughput kinetics is understanding the performance characteristics of each platform. The selection of an appropriate technology depends on multiple factors, including the kinetic timescale of interest, compound availability, and required throughput.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Kinetic Platforms

| Platform | Measurement Precision | Sample Consumption | Cost per Data Point | Data Richness | Automation Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR | High (CV < 10%) | Low (μg range) | Moderate | High (real-time curves) | Excellent |

| Stopped-Flow | Moderate (CV 10-15%) | Moderate | Moderate | High (millisecond resolution) | Good |

| Plate-Based Fluorescence | Variable (CV 5-20%) | Very Low | Low | Single time-point or limited points | Excellent |

| Radioligand Filtration | High (CV < 8%) | Low | Low to Moderate | Single time-point or limited points | Excellent |

| LC/MS/MS | High (CV < 10%) | Low | High | Multiplexed, direct quantification | Good |

The Z-factor and SSMD (Strictly Standardized Mean Difference) have emerged as critical quality assessment metrics for high-throughput kinetic assays. These statistical tools help researchers distinguish between true binding events and experimental noise, ensuring robust hit identification [31]. For kinetic studies specifically, the data quality requirements are often more stringent than for equilibrium assays, as multiple time points must be collected and analyzed with precision.

Recent advances in microfluidics and droplet-based technologies have further accelerated throughput while reducing reagent consumption. One groundbreaking approach demonstrated the capability to perform 100 million reactions in 10 hours at one-millionth the cost of conventional techniques, using dramatically reduced reagent volumes [31]. Such innovations continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in high-throughput kinetic characterization.

Experimental Protocols for High-Throughput Binding Kinetics

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Protocol

SPR has become a gold standard for label-free kinetic measurements due to its ability to provide real-time data on binding events. A robust SPR protocol for high-throughput applications involves the following key steps:

Step 1: Surface Preparation - The target molecule (typically a protein receptor) is immobilized on a biosensor chip surface using covalent coupling methods such as amine coupling, thiol coupling, or capture-based approaches. The surface density is optimized to minimize mass transport limitations while maintaining sufficient signal-to-noise ratio.

Step 2: Sample Preparation - Compounds are prepared in concentration series using automated liquid handling systems. A typical 8-point concentration series might range from 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value. Running buffer conditions are optimized to minimize non-specific binding while maintaining protein stability.

Step 3: Kinetic Measurement Cycle - Each sample cycle consists of four phases: (1) Baseline establishment with running buffer, (2) Association phase where the compound flows over the surface, (3) Dissociation phase where running buffer replaces the compound solution, and (4) Regeneration to remove bound compound without damaging the immobilized target.

Step 4: Data Analysis - Sensorgrams are processed by subtracting reference cell signals and buffer blank injections. The resulting binding curves are fitted to appropriate kinetic models (e.g., 1:1 binding model) to extract kon and koff values. The KD is calculated as koff/kon [28] [30].

For high-throughput applications, modern SPR instruments can process 384-well plates or higher, with automated sample injection and data analysis pipelines. Quality control parameters including Rmax, χ2, and residual plots are monitored to ensure data reliability.

Plate-Based Kinetic Binding Assay Protocol

For laboratories without access to specialized instrumentation like SPR, plate-based kinetic assays offer a accessible alternative with standard HTS equipment:

Step 1: Assay Plate Preparation - A source plate containing test compounds is prepared, typically in DMSO stock solutions. Using automated liquid handlers, compounds are transferred to assay plates in nanoliter volumes to achieve the desired final concentrations [31].

Step 2: Reaction Initiation - The biological target (enzyme, receptor preparation, or cell-based system) is added to each well using multidispensors or automated pipetting systems. The timing of additions is carefully controlled to ensure consistent incubation times across the plate.

Step 3: Time-Point Sampling - Unlike endpoint assays, kinetic measurements require multiple time points. This can be achieved through either (a) sequential plate processing with fixed time intervals between plates, or (b) using quenching methods to stop reactions at specific times within a single plate.

Step 4: Detection and Analysis - Depending on the detection method (fluorescence, radiometric, or absorbance), plates are read at multiple time points. Progress curves are generated for each compound, and kinetic parameters are extracted through nonlinear regression fitting to appropriate models [28].

Software tools like phactor have been developed specifically to facilitate the design and analysis of high-throughput experiment arrays, storing chemical data, metadata, and results in machine-readable formats [32]. These platforms enable researchers to rapidly transition from experimental design to kinetic parameter estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing successful high-throughput kinetic studies requires specialized reagents and materials optimized for kinetic measurements. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Kinetics

| Reagent/Material | Function in Kinetic Assays | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Biosensor Chips (CM5, NTA, SA) | Immobilization surface for SPR | Coupling efficiency, stability, non-specific binding |

| HTS Microplates (384, 1536-well) | Reaction vessels for plate-based assays | Well-to-well consistency, evaporation control, binding properties |

| Label-Free Detection Reagents | Signal generation in absence of direct labels | Minimal perturbation to native binding, compatibility with detection system |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Ligands | Tracing binding events in MS-based assays | Incorporation efficiency, biochemical equivalence to native ligand |

| Reference Compounds | Assay validation and quality control | Well-characterized kinetics, chemical stability, solubility |

| - | ||

| Liquid Handling Components | Automated reagent transfer | Precision at low volumes, chemical compatibility, carryover control |

| Affinity Capture Reagents | Selective isolation of complexes | Specificity, binding capacity, elution conditions |