Thermodynamic Stability in Solid Solutions: From First-Principles Prediction to Pharmaceutical Application

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the principles governing the thermodynamic stability of solid solutions, a critical factor in materials science and pharmaceutical development.

Thermodynamic Stability in Solid Solutions: From First-Principles Prediction to Pharmaceutical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the principles governing the thermodynamic stability of solid solutions, a critical factor in materials science and pharmaceutical development. It establishes foundational concepts, including stability criteria and the role of electronic structure, before detailing cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies for stability assessment. The content addresses common challenges in predicting and optimizing stability, illustrated with case studies from refractory alloys and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Finally, it covers validation frameworks and comparative analysis tools, offering researchers and drug development professionals a unified view of how thermodynamic stability principles enable the design of advanced materials and stable, bioavailable drug formulations.

The Core Principles: Defining and Modeling Stability in Solid Solutions

Core Concepts and Definitions

Solid Solutions Fundamentals

A solid solution is a single phase that exists over a range of chemical compositions, where different types of atoms or molecules coexist within the same crystal lattice [1]. This phenomenon occurs when components demonstrate significant miscibility, governed by the interaction between constituent atoms. Solid solutions represent a fundamental concept in materials science, particularly in the development of alloys and functional materials where tailored properties are essential [1].

The formation and stability of solid solutions are dictated by several key factors. When species do not tend to bond to each other, separate phases form with limited miscibility. Conversely, strong mutual attraction can lead to intermetallic compounds, while minimal difference between like and unlike bonds enables solid solution formation across wide composition ranges [1]. The Cu-Ni system exemplifies this behavior, exhibiting complete solubility due to similar atomic radii, electronegativities, valences, and face-centred cubic structures [1].

Thermodynamic Stability Principles

Thermodynamic stability characterizes how difficult compounds decompose into different phases or compounds, even over infinite time [2]. In nanocrystalline materials, this concept extends to the potential existence of a minimum in Gibbs free energy at a finite grain size, representing a thermodynamically favored polycrystalline state rather than a single crystal [3].

The Gibbs free energy (G) of a system determines its thermodynamic stability. For grain growth in polycrystalline materials, curve (a) in Figure 1 shows the classical condition where G monotonically decreases as grain size increases, reaching its minimum at the single crystal state. Curve (b) demonstrates segregation-induced thermodynamic stability, where a minimum exists at a finite grain size (point E), making nanocrystalline structures thermodynamically stable [3].

Table 1: Types of Solid Solutions and Their Characteristics

| Type | Mechanism | Key Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substitutional | One atom type substitutes for another in the crystal lattice | Similar atomic radii required (<15% difference) | Cu-Ni alloys, Olivine (Fe-Mg) series [1] |

| Interstitial | Atoms added to normally unoccupied sites in the structure | Smaller atoms fit into interstitial spaces | Carbon in iron (steel) [1] |

| Coupled Substitution | Cations of different valence interchange with charge balance maintenance | Two coupled cation substitutions required | Plagioclase feldspars [1] |

| Omission | Cations omitted from normally occupied sites | Creates vacancies in the crystal structure | Non-stoichiometric oxides [1] |

Quantitative Thermodynamics of Solid Solutions

Thermodynamic Functions and Mixing Behavior

The stability of solid solutions is governed by fundamental thermodynamic relationships. The entropy of mixing (ΔS_mix) provides the driving force for solid solution formation and is primarily configurational in origin [1]. For a random mixture of A and B atoms, the configurational entropy is given by:

ΔSmix = -R(xA ln xA + xB ln x_B)

where R is the gas constant, and xA and xB are the mole fractions of components A and B respectively [1].

The enthalpy of mixing (ΔH_mix) determines whether a solid solution exhibits ideal or non-ideal behavior. Using a simple nearest-neighbor interaction model:

ΔHmix = 0.5Nz xA xB (2WAB - WAA - WBB)

where z is the coordination number, N is the total number of sites, and Wij represents the energy of i-j bonds [1]. When ΔHmix = 0, the solution is ideal; positive values indicate non-ideal behavior favoring phase separation, while negative values suggest ordering tendencies [1].

Stability Criteria and Quantitative Assessment

Thermodynamic stability in solid solutions is quantitatively assessed through several key parameters. The formation energy and distance to the convex hull serve as primary indicators of thermodynamic stability, with the latter providing more accurate but computationally complex assessment [2]. Machine learning approaches have been developed to predict these parameters, with ensemble decision tree methods like Extremely Randomized Trees (ERT) achieving mean absolute errors of 121 meV/atom for cubic perovskite systems [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Descriptors for Thermodynamic Stability Assessment

| Descriptor | Definition | Application | Typical Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy | Energy change when compound forms from elements | Initial stability screening | Negative values indicate stability |

| Distance to Convex Hull | Energy above the most stable phase decomposition | Accurate stability quantification | 0 meV/atom for stable phases [2] |

| Size Mismatch | Difference in atomic/ionic radii between components | Solid solution extent prediction | <15% for extensive solid solution [1] |

| Mixing Enthalpy | Heat absorbed or released during mixing | Ideal vs. non-ideal behavior classification | Zero for ideal solutions [1] |

For nanocrystalline alloys, thermodynamic stability assessment presents unique challenges. The experimental distinction between kinetic and thermodynamic stability requires careful long-run experiments, though extremely long time scales at low temperatures can make this impractical [3]. True thermodynamic stability is confirmed when systems reach stationary states with finite grain sizes after sufficient thermal exposure, as illustrated in profile (b) of Figure 2 [3].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Component Prediction and Stability Assessment

Modern experimental approaches leverage machine learning for efficient thermodynamic stability prediction. The following protocol outlines a standard methodology for component prediction in novel materials:

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Assisted Stability Prediction

Descriptor Selection: Compose a feature vector incorporating (a) elemental properties (Mendeleev number, unfilled valence orbitals, thermal expansion coefficients), and (b) structural descriptors from Voronoi tessellations [2].

Dataset Construction: Build comprehensive datasets from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, typically comprising 1,900-250,000 compounds with calculated energies above convex hull [2].

Model Training: Implement ensemble methods like Random Forests (RF) or Extremely Randomized Trees (ERT) for regression tasks, using 5-fold cross-validation. Optimal models typically achieve F1 scores of 0.88±0.032 for classification and RMSE of 28.5±7.5 meV/atom for regression [2].

Validation: Experimentally verify predictions through targeted synthesis of 10-15 new compounds, confirming thermodynamic stability through structural characterization [2].

Protocol 2: Experimental Stability Assessment for Nanocrystalline Alloys

Thermal Treatment: Expose materials to elevated temperatures (specific to material system) for extended durations to overcome kinetic barriers [3].

Grain Size Monitoring: Track temporal evolution of grain size using X-ray diffraction or electron microscopy at regular intervals [3].

Stationary State Identification: Identify grain size invariance over extended thermal exposure, indicating potential thermodynamic stability [3].

Pathway Verification: Confirm stability by approaching from "above" (grain refinement) and "below" (grain growth) to validate true equilibrium [3].

Advanced Characterization Techniques

For colloidal solid dispersions, thermodynamic stability assessment requires specialized approaches. Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the foundation for analyzing size distributions in putative thermodynamically stable nanoparticles [4]. The methodology involves:

Size Distribution Analysis: Measure particle size distributions using dynamic light scattering or electron microscopy for 100+ particles [4].

Interfacial Energy Modeling: Fit size distributions to CNT-derived expressions with size-dependent interfacial free energy (γ), typically following power-law dependencies (r⁻² or r⁻³) [4].

Reversibility Testing: Perform temperature cycling and concentration variations to confirm system return to initial state after perturbation [4].

Supersaturation Assessment: Determine monomer concentration relative to bulk saturation to distinguish true stability from metastability [4].

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Solid Solution Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite Oxide Precursors (e.g., metal carbonates, nitrates) | Source of cationic components (A, B sites) | Oxide solid solution synthesis | Purity >99.9%, controlled stoichiometry [2] |

| Thiol Surfactants (e.g., alkanethiols) | Surface energy modification, size control | Gold-thiol nanoparticle digestive ripening [4] | Chain length, concentration critical for γ modification |

| Voronoi Tessellation Software | Structural descriptor generation | Machine learning feature engineering [2] | Accurate atomic position input required |

| Hydroxide Solutions (e.g., NaOH, KOH) | pH control, surface charge modification | Magnetite nanoparticle stabilization [4] | Concentration affects interfacial energy significantly |

| DFT Calculation Packages (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Formation energy, convex hull calculation | Thermodynamic stability quantification [2] | Pseudopotential choice, k-point sampling critical |

Factors Governing Solid Solution Extent and Stability

Critical Parameters and Boundary Conditions

Multiple factors interact to determine the extent and stability of solid solutions, creating complex relationships that researchers must navigate:

Atomic/Ionic Size Considerations: The radius ratio between solute and solvent atoms represents perhaps the most fundamental constraint. Extensive solid solution typically requires a size mismatch below approximately 15%, as exemplified by the Mg²⁺-Fe²⁺ system (7% mismatch) showing complete solid solution in olivine minerals. In contrast, the Ca²⁺-Mg²⁺ pair with 32% size difference demonstrates very limited substitution capability [1].

Temperature Dependence: Elevated temperatures strongly favor solid solution formation through multiple mechanisms. The -TS term in Gibbs free energy stabilizes solid solutions due to their higher configurational entropy, while enhanced atomic vibration and more open structures better accommodate size mismatches through local bond bending rather than strict compression or stretching [1].

Structural Flexibility: The host structure's ability to accommodate substitution through bond angle adjustments without catastrophic distortion significantly impacts solid solution extent. Some crystal structures demonstrate remarkable tolerance to cation substitution through distributed strain accommodation, while rigid frameworks may undergo phase separation even with minimal size differences [1].

Cation Charge Balance: Heterovalent substitutions (involving different charge cations) rarely form complete solid solutions at low temperatures due to competing ordering transitions and phase separation at intermediate compositions. These phenomena maintain local charge balance while accommodating substitution-induced strain, often resulting in complex phase behavior [1].

Advanced Stability Concepts in Nanostructured Materials

In nanocrystalline systems, thermodynamic stability manifests through unique mechanisms not observed in bulk materials. Segregation-induced thermodynamic stability occurs when grain boundary segregation lowers system Gibbs free energy sufficiently to create a minimum at finite grain sizes [3]. This phenomenon enables thermodynamically stable nanostructures when the equilibrium grain size remains below 100 nm [3].

The distinction between kinetic and thermodynamic stability becomes particularly crucial at nanoscale dimensions. Kinetic stabilization results from hindered grain boundary mobility due to drag forces or slow diffusion, creating apparently stable structures that represent transient states on geological time scales [3]. True thermodynamic stability demonstrates path independence and returns to equilibrium states after perturbation [3].

Inverse coarsening or digestive ripening phenomena, observed in systems like gold-thiol nanoparticles, provide compelling evidence for thermodynamic stabilization mechanisms. These systems display spontaneous breakdown of larger particles and coalescence of smaller ones toward a monodisperse distribution, suggesting equilibrium control rather than kinetic limitations [4]. The size-dependent interfacial energy, often following power-law relationships (γ ∝ r⁻³ for capacitive charging models), enables these unusual stabilization pathways [4].

Decomposition Energy and the Phase Diagram Convex Hull

In solid-state chemistry and materials science, predicting the thermodynamic stability of a compound is a fundamental step in discovering new synthesizable materials. A compound is considered thermodynamically stable if it persists indefinitely under specified conditions without decomposing into other substances. The core principle governing this stability is the minimization of the system's Gibbs free energy. Within a multi-component chemical system, the true measure of a compound's stability is not merely its energy of formation from pure elements, but its energy relative to all other compounds in the same chemical space. This comparative stability is quantified by its decomposition energy and visualized through the construction of a phase diagram convex hull [5] [6]. These concepts form the theoretical bedrock for high-throughput materials discovery, enabling researchers to rapidly screen vast compositional spaces for promising new materials, from high-entropy alloys to complex inorganic compounds [7] [8].

Theoretical Foundations of the Convex Hull

The Convex Hull in Phase Stability

The convex hull, in the context of phase diagrams, is a geometric construction that identifies the set of thermodynamically stable phases in a chemical system. It is defined as the smallest convex set in energy-composition space that contains all data points representing the various compounds [9]. In simpler terms, it is the lowest-energy "envelope" connecting the most stable phases at different compositions.

For a thermodynamic system, the relevant space is defined by:

- Composition axes (N-1 dimensions): For a system with N elements, the composition is represented in N-1 dimensions. For example, a ternary system (A-B-C) uses a 2D composition triangle.

- Energy axis (1 dimension): The Gibbs free energy per atom (or formula unit) at a given temperature and pressure.

Mathematically, for a set of points in this space, the convex hull is the set of all convex combinations of these points. A convex combination of points ( x1, x2, ..., xk ) is a point of the form ( \sum{i=1}^{k} \thetai xi ), where ( \thetai \geq 0 ) and ( \sum{i=1}^{k} \thetai = 1 ) [9]. In thermodynamics, the coefficients ( \thetai ) correspond to the fractional amounts of different phases in a mixture.

Table 1: Key Properties of the Convex Hull in Thermodynamics

| Property | Mathematical Description | Thermodynamic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Extensivity | Hull(X) contains X | The hull encompasses all known compounds in the system. |

| Minimality | Smallest convex set containing X | Represents the lowest possible free energy configuration for any composition. |

| Idempotence | Hull(Hull(X)) = Hull(X) | Recalculating the hull with points already on the hull does not change it. |

Formation Energy vs. Decomposition Energy

A critical distinction must be made between a compound's formation energy and its decomposition energy, as this lies at the heart of stability assessment.

Formation Energy (( \Delta Ef ) or ( \Delta Hf )): This is the energy change when a compound is formed from its constituent elements in their standard states. It is calculated as: ( \Delta Ef = E{compound} - \sumi ni \mui ) where ( E{compound} ) is the total energy of the phase, ( ni ) is the number of moles of component *i*, and ( \mui ) is the chemical potential (energy per atom) of the pure component i [5]. This energy is intrinsic to the compound itself.

Decomposition Energy (( \Delta Ed ) or ( \Delta Hd ), Energy Above Hull): This is the energy difference between the compound and its most stable decomposition products at the same overall composition. It is the vertical distance in energy from the compound's data point to the convex hull surface [5] [10] [6]. A stable compound lies directly on the convex hull, meaning its decomposition energy is zero. An unstable compound lies above the hull, and its decomposition energy is positive.

Table 2: Comparison of Formation Energy and Decomposition Energy

| Feature | Formation Energy (( \Delta E_f )) | Decomposition Energy (( \Delta E_d )) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Energy from constituent elements | Energy from competing stable phases |

| Reference State | Pure elements | The convex hull |

| Stability Indicator | Necessary but not sufficient condition | Direct measure of thermodynamic stability |

| Typical Magnitude | Often eV/atom | Often 10-100 meV/atom [6] |

| Value for Stable Phases | Negative | 0 meV/atom |

The relationship is non-linear; a strongly negative formation energy does not guarantee stability, as other compounds with the same elements may have even more favorable energies [6]. The convex hull construction is the tool that reveals this delicate balance.

Computational Methodology and Protocols

Protocol for Constructing a Phase Diagram Convex Hull

Constructing a convex hull for a chemical system involves a systematic procedure to evaluate and compare the stability of all known phases. The following protocol, as implemented in high-throughput frameworks like the Materials Project, details the key steps [5].

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Energy Calculation

- Objective: Collect a complete set of energy data for all relevant phases in the chemical system.

- Procedure:

- Identify all known compounds in the target chemical system (e.g., Li-Fe-O) from crystallographic databases.

- Calculate the total energy (( E )) for each compound and for each pure element using first-principles methods, typically Density Functional Theory (DFT). Consistency in computational parameters is critical.

- Calculate the formation energy (( \Delta E_f )) for each compound on a per-atom basis using the formula in Section 2.2.

Step 2: convex hull Construction

- Objective: Determine the lower convex envelope of the data in energy-composition space.

- Procedure:

- Represent each compound as a point in a multi-dimensional space where axes are chemical composition (e.g., fractional coordinates of each element) and formation energy per atom.

- Apply a convex hull algorithm (e.g., Quickhull) to this set of points [5].

- The algorithm outputs the set of "stable" phases that form the vertices of the hull. Any phase that is not a vertex of the hull is, by definition, unstable.

Step 3: Decomposition Energy Calculation

- Objective: Quantify the instability of phases not on the hull.

- Procedure:

- For a phase of interest with composition ( C ), identify the simplex (e.g., a tie-line in a binary, a tie-triangle in a ternary) on the convex hull that contains ( C ).

- The energy of the hull at composition ( C ), ( E{hull}(C) ), is the linear combination of the energies of the stable phases defining that simplex.

- The decomposition energy is calculated as: ( \Delta Ed = E{compound} - E{hull}(C) ) [10].

Step 4: Validation and Analysis

- Objective: Identify the specific decomposition pathway for unstable compounds.

- Procedure:

- The stable phases defining the simplex at the compound's composition are its predicted decomposition products.

- The stoichiometric coefficients for the decomposition reaction are derived from the linear combination that gives the composition ( C ). For example, a compound ABO₃ might decompose as ABO₃ → ½ A₂BO₄ + ½ BO₂ [10].

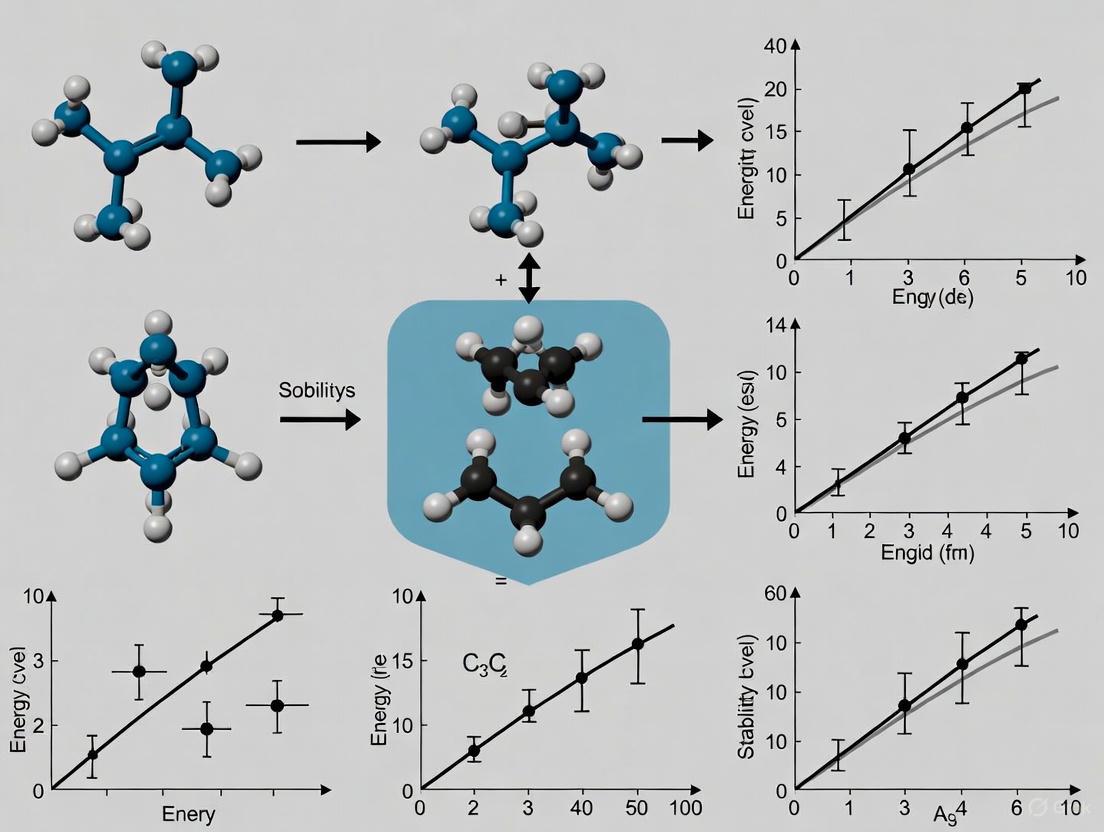

Figure 1: Computational workflow for constructing a phase diagram convex hull and calculating decomposition energies.

A Concrete Example: Calculating Ehull for BaTaNO₂

The concept of decomposition energy and the convex hull can be illustrated with a real example from the Materials Project database. Consider the oxynitride BaTaNO₂ [10].

- Stable Neighbors: The convex hull construction for the Ba-Ta-N-O system reveals that the stable phases surrounding the composition of BaTaNO₂ are Ba₄Ta₂O₉, Ba(TaN₂)₂, and Ta₃N₅.

- Decomposition Reaction: BaTaNO₂ is found to be unstable and decomposes into a mixture of these three phases. The balanced decomposition reaction is determined by the geometry of the hull and is given by: ( \text{BaTaNO}2 \rightarrow \frac{2}{3}\text{Ba}4\text{Ta}2\text{O}9 + \frac{7}{45}\text{Ba}(\text{TaN}2)2 + \frac{8}{45}\text{Ta}3\text{N}5 )

- Energy Calculation: The energy above hull (Eₕᵤₗₗ) is then calculated using the normalized (eV/atom) energies of all involved phases [10]: ( E{hull} = E{\text{BaTaNO}2} - \left( \frac{2}{3}E{\text{Ba}4\text{Ta}2\text{O}9} + \frac{7}{45}E{\text{Ba}(\text{TaN}2)2} + \frac{8}{45}E{\text{Ta}3\text{N}_5} \right) ) For BaTaNO₂, this value is calculated to be 32 meV/atom, indicating a low energy of decomposition and suggesting the phase may be synthesizable as a metastable material [10].

Advanced Considerations and Emerging Approaches

Accuracy and Limitations of Calculated Phase Diagrams

While powerful, computational phase diagrams based on DFT have inherent limitations. The calculated diagrams are typically for 0 K and 0 atm pressure, whereas real synthesis occurs at finite temperatures [5]. Finite-temperature effects, such as vibrational entropy, can significantly alter phase stability. Furthermore, DFT calculations themselves have inherent errors in approximating the exchange-correlation energy. While these errors often cancel when comparing similar compounds, they can still impact the precise location of the hull [6]. For systems involving gaseous elements, approximations are used to estimate finite-temperature free energies, but these introduce additional uncertainty [5]. Consequently, a small positive Eₕᵤₗₗ (e.g., < 20-50 meV/atom) does not necessarily rule out the existence of a metastable phase, as seen with BaTaNO₂.

The Challenge of Multi-Component Systems and Machine Learning

Extending convex hull analysis to ternary, quaternary, and higher-order systems presents both a geometric and computational challenge. The number of potential compounds grows combinatorially, making exhaustive calculation prohibitive [7] [6]. This has driven the development of advanced models and machine learning (ML) approaches.

- Regular Solution Models: For high-entropy alloys (HEAs), models that approximate the Gibbs free energy of solid solutions using binary interaction parameters have proven effective. These models, combined with convex hull constructions that include competing intermetallic phases, can successfully predict stable single-phase solid solutions in vast compositional spaces [7].

- Machine Learning for Stability Prediction: ML offers a path to bypass expensive DFT calculations by learning the relationship between chemical composition and stability directly from existing databases. However, a critical finding is that models which accurately predict formation energy (( \Delta Hf )) often perform poorly at predicting stability (( \Delta Hd )) [6]. This is because ( \Delta H_d ) depends on small energy differences between many compounds, and ML models lack the systematic error cancellation that benefits DFT-based hull constructions. Recent ensemble models that incorporate electron configuration information show improved performance and sample efficiency [8].

Table 3: Key Computational Parameters and Data Sources

| Parameter/Method | Description | Typical Value/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Reference temperature for phase stability | 0 K (DFT), up to 1350 K for HEA screening [7] |

| Energy Functional | DFT exchange-correlation functional | GGA, GGA+U, R2SCAN [5] |

| Data Source | Repository for computed energies | Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW [8] [6] |

| Stability Threshold | Eₕᵤₗₗ value for stable compounds | 0 meV/atom |

| Metastability Threshold | Eₕᵤₗₗ suggesting possible synthesis | < 20-50 meV/atom [10] |

Expanding the Thermodynamic Picture: Elastic and Nanoscale Effects

Modern stability assessments are moving beyond ideal bulk thermodynamics to incorporate other physical effects.

- Elastic Contributions: In multi-component alloys, local lattice distortions due to atomic size mismatch store elastic energy. This energy can be a significant destabilizing factor. Formalisms now exist to incorporate this elastic energy into CALPHAD (Calculation of Phase Diagrams) models, leading to more accurate predictions of phase stability and miscibility gaps in complex alloys [11].

- Nanoscale Stability: The classical view is that a nanocrystalline material is metastable and will coarsen to reduce grain boundary area. However, in alloyed systems, grain boundary segregation can lower the system's Gibbs free energy, potentially creating a thermodynamic minimum at a finite grain size. This leads to the concept of thermodynamically stable nanostructures, where grain growth is halted not by kinetics but by equilibrium thermodynamics [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Type | Primary Function in Stability Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Software | First-principles DFT code for calculating total energies of crystal structures. |

| pymatgen | Python Library | Analyzes phase diagrams, constructs convex hulls, and calculates decomposition energies [5]. |

| MPRester API | Data Tool | Fetches computed material data (energies, structures) from the Materials Project database [5]. |

| CALPHAD Software | Software | Constructs multi-component phase diagrams by modeling Gibbs free energies of all phases. |

| JARVIS, OQMD | Database | Provides DFT-computed data for training ML models and validation [8]. |

| High-Throughput Compute Cluster | Hardware | Enables parallel calculation of thousands of compounds for comprehensive hull construction. |

The concepts of decomposition energy and the phase diagram convex hull provide an unambiguous, quantitative framework for determining the thermodynamic stability of solid-state compounds. The convex hull method transforms a set of individual formation energies into a global stability map, with the energy above hull (( \Delta E_d )) serving as the key metric for prioritization in materials discovery. While computational implementations rely on approximations, ongoing advances in DFT methods, the integration of elastic and nanoscale effects, and the rise of sophisticated machine learning models are continuously enhancing the accuracy and scope of stability predictions. As these tools become more integrated and accessible, they will remain indispensable for guiding the efficient synthesis of novel materials, from next-generation alloys to complex functional oxides.

The electronic band structure of a material is a fundamental determinant of its stability and properties. The band filling concept refers to the distribution of valence electrons among the available electronic states in the energy bands. When these bands are filled to an optimal level, preferentially occupying bonding states while leaving antibonding states vacant, the thermodynamic stability and mechanical properties of the material can be significantly enhanced. This principle provides a powerful framework for designing advanced solid solutions with tailored characteristics, particularly in the realm of transition-metal ceramics and intermetallic compounds.

In solid solutions research, the deliberate substitution of elemental components allows for precise control over electron count, thereby engineering the electronic band structure to achieve superior stability. This whitepaper examines the fundamental mechanisms through which band filling governs material stability, presenting detailed case studies, experimental protocols, and computational methodologies that demonstrate this connection across various material systems.

Theoretical Foundations of Band Filling

Electronic Origins of Stability

The stability of crystalline solids is intimately connected to their electronic structure. According to quantum mechanical principles, when atoms arrange into crystalline structures, their atomic orbitals overlap to form energy bands. These bands can be characterized as having bonding, non-bonding, or antibonding character relative to the original atomic states.

The band filling effect occurs when the number of valence electrons in a system precisely fills these electronic states up to an energetically favorable point, typically just below a sharp peak in the density of states (van Hove singularity) or before the occupation of strongly antibonding states. This optimal filling minimizes the total electronic energy of the system, thereby maximizing its cohesive energy and thermodynamic stability. Systems with partially filled bands often exhibit higher energy states and reduced stability compared to those with optimally filled bands.

Band Engineering in Solid Solutions

In elemental compounds, band filling is fixed by the element's electronic configuration. However, in solid solutions, where different elements occupy the same crystallographic sites, the electron count can be systematically varied. This enables the strategic "tuning" of band filling by controlling the composition of the solution. The relationship can be expressed as:

\[ \text{Total Valence Electrons} = \sumi ci \cdot N_i \]

Where \( ci \) is the concentration of element \( i \) and \( Ni \) is its valence electron count. By selecting elements with different valence electron concentrations and systematically varying their proportions, researchers can precisely control the Fermi level position within the electronic band structure, thereby optimizing stability and properties.

Case Studies in Transition Metal Diborides

Scandium-Tantalum Diboride System

The ScTaB\textsubscript{2} system provides a compelling demonstration of band filling effects on stability and properties. First-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) reveal that ScB\textsubscript{2} and TaB\textsubscript{2} readily mix to form stable solid solutions across the entire composition range (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) even at absolute zero temperature [12].

The mixing thermodynamics show negative values of the energy of mixing (ΔE\textsubscript{mix}) across all compositions, indicating a spontaneous tendency for solid solution formation. This unusual behavior at low temperatures signals a strong electronic driving force beyond configurational entropy effects [12].

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Sc\textsubscript{1-x}Ta\textsubscript{x}B\textsubscript{2} Solid Solutions

| Property | Vegard's Law Prediction | Actual Maximum Value | Deviation | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shear Modulus | Linear trend | ~25% higher | +25% | Intermediate x |

| Young's Modulus | Linear trend | ~20% higher | +20% | Intermediate x |

| Hardness | Linear trend | ~40% higher | +40% | Intermediate x |

| Stability | - | Enhanced across all x | - | 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 |

The dramatic positive deviations from Vegard's law evident in Table 1 demonstrate the substantial enhancement of mechanical properties attributable to optimal band filling. Specifically, the substitution of Ta (group V) for Sc (group III) in the metal sublattice increases the valence electron concentration, systematically filling the electronic bands of the diboride system [12] [13].

Titanium-Tantalum Diboride System with Boron Vacancies

Recent investigations of TiTaB\textsubscript{2} systems have revealed the complex interplay between alloying and defect engineering in modulating band filling. DFT-based cluster expansion methods predict that TiB\textsubscript{2} and TaB\textsubscript{2} form stable solid solutions within the composition range 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.667 at absolute zero temperature, with the stability range expanding at elevated temperatures (above ~400 K) due to entropic effects [14].

In Ta-rich compositions (0.667 ≤ x < 1), the introduction of boron vacancies creates a dual effect: while initially destabilizing due to broken bonds, the vacancy formation simultaneously reduces the number of electrons occupying antibonding states. At small vacancy concentrations (0 < y ≤ 0.25 in Ti\textsubscript{1-x}Ta\textsubscript{x}B\textsubscript{2-y}), this band filling effect dominates, leading to enhanced stability and modest improvements in shear strength, stiffness, and hardness [14].

Table 2: Stability Ranges in Transition Metal Diboride Systems

| Material System | Stable Composition Range | Temperature Dependence | Key Stabilizing Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sc\textsubscript{1-x}Ta\textsubscript{x}B\textsubscript{2} | 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 | Stable even at 0 K | Band filling via electron addition |

| Ti\textsubscript{1-x}Ta\textsubscript{x}B\textsubscript{2} | 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.667 | Expands with temperature | Combined band filling and entropy |

| Ti\textsubscript{1-x}Ta\textsubscript{x}B\textsubscript{2-y} | 0.667 ≤ x < 1, 0 < y ≤ 0.25 | Stabilized at high T | Band filling via vacancy formation |

The comparison in Table 2 illustrates how different mechanisms for controlling band filling—either through electron addition via substitution or electron subtraction via vacancy formation—can both lead to enhanced stability within specific composition ranges.

Computational and Experimental Methodologies

First-Principles Computational Protocols

Density Functional Theory (DFT) provides the foundation for investigating band filling effects. The following protocol outlines key steps for such investigations:

Structure Selection and Preparation: Begin with the appropriate crystal structure (e.g., AlB\textsubscript{2}-type structure, space group P6/mmm for diborides). For solid solutions, generate multiple configurations with different arrangements of the constituent atoms on the relevant sublattice [12].

Electronic Structure Calculations: Employ plane-wave basis sets with pseudopotentials to solve the Kohn-Sham equations. Use the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) or similar exchange-correlation functionals [15]. For more accurate band gaps, hybrid functionals like HSE06 may be necessary [15].

Cluster Expansion Method: For solid solutions, implement the cluster expansion formalism according to the mathematical foundation of Sanchez, Ducastelle, and Gratias to determine effective interactions between different elements on the sublattice [12]. The methodology involves:

- Selecting a set of cluster types (pairs, triplets, etc.)

- Fitting effective cluster interactions to DFT-derived total energies

- Validating the model using cross-validation techniques

Thermodynamic Integration: Calculate the energy of mixing (ΔE\textsubscript{mix}) as:

\[ \Delta E{\text{mix}} = E{\text{solid solution}} - [xE{\text{TaB}2} + (1-x)E{\text{ScB}2}] \]

where negative values indicate stable mixing [12].

Mechanical Property Prediction: Compute elastic constants (C\textsubscript{ij}) from stress-strain relationships, then derive bulk modulus, shear modulus, and Young's modulus using Voigt-Reuss-Hill averaging. Estimate hardness using empirical models based on elastic moduli or more sophisticated approaches [12].

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for band filling analysis in solid solutions

Experimental Validation Techniques

While computational methods predict band filling effects, experimental validation is essential:

Synthesis Protocols: For diboride systems, solid solutions can be prepared using:

- Solid-state reaction methods with elemental precursors or parent diborides

- Magnetron sputtering for thin-film coatings using composite targets

- Spark plasma sintering for bulk samples with controlled stoichiometry

Structural Characterization:

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm phase purity and lattice parameters

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) for compositional analysis

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for detailed structural analysis

Mechanical Testing:

- Nanoindentation for hardness and elastic modulus measurement

- Microindentation for Vickers or Knoop hardness

- Ultrasonic measurements for elastic constants

Electronic Structure Analysis:

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for valence band structure

- Soft X-ray emission spectroscopy for partial density of states

- Optical spectroscopy for band gap determination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes (VASP, CASTEP, Wien2k) | Electronic structure calculation | Total energy, DOS, band structure [12] [15] [16] |

| Cluster Expansion Codes (ATAT, UNCLE) | Solid solution thermodynamics | Effective cluster interactions, phase stability [12] |

| Transition Metal Diborides (ScB₂, TaB₂, TiB₂) | Base compounds for solid solutions | Hard coating materials [12] [14] |

| Magnetron Sputtering Systems | Thin film deposition | Synthesis of diboride coatings [12] |

| X-ray Diffractometers | Structural characterization | Phase identification, lattice parameter measurement [13] |

| Nanoindentation Systems | Mechanical property measurement | Hardness, elastic modulus [13] |

Advanced Applications and Material Systems

Beyond Diborides: Quaternary Chalcogenides

The band filling principle extends to other material systems, including quaternary chalcogenides such as CuZn₂InS₄ and CuZn₂GaS₄. First-principles studies using the full-potential augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method as implemented in the Wien2k code have investigated the phase stability, electronic structure, and optoelectronic properties of these materials [17] [16].

In these systems, band filling effects influence not only thermodynamic stability but also optoelectronic properties including absorption coefficients, dielectric functions, and refractive indices. The ability to tune these properties through controlled composition makes them promising for various optoelectronic applications [16].

Two-Dimensional Materials: Mo₁₋ₓWₓSe₂ Alloys

Recent investigations of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide alloys have revealed non-linear composition dependence of optical properties governed by band filling effects. In Mo₁₋ₓWₓSe₂ alloys, statistical averaging over configurational ensembles reveals a non-linear dependence of the optical band gap on alloy composition [18].

In W-rich compositions, pronounced spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effects significantly modify the band structure and indirectly influence optical absorption anisotropy. The SOC effects lead to an increase in the optical band gap and a concurrent decrease in exciton binding energy, demonstrating the complex interplay between band filling, spin-orbit interactions, and optical properties [18].

Diagram 2: Band filling effects on material properties

The strategic manipulation of electronic band filling through solid solution formation represents a powerful paradigm for materials design. As demonstrated across multiple material systems—from transition metal diborides to quaternary chalcogenides and two-dimensional semiconductors—controlled band filling enables unprecedented tuning of thermodynamic stability and functional properties.

Future research directions should focus on:

- High-throughput computational screening of solid solution systems for optimal band filling

- Machine learning approaches to accelerate the prediction of stability and properties

- Advanced synthesis techniques for precise stoichiometric control in complex systems

- Operando characterization methods to directly observe electronic structure changes during synthesis

The integration of band filling principles with modern computational and experimental methods will continue to drive innovations in materials design for applications ranging from superhard coatings to energy conversion and electronic devices.

Principles of Thermodynamic Stability in Solid Solutions Research

The pursuit of materials with superior mechanical properties and thermal stability represents a cornerstone of materials science research, particularly for applications in extreme environments. Within this context, solid solutions—crystalline structures where different atomic species occupy equivalent lattice sites—provide a powerful pathway for engineering materials with tailored properties. The thermodynamic stability of these solid solutions is governed by fundamental principles including the energy of mixing, electronic structure modifications, and the balance between enthalpy and entropy effects. Recent advances in first-principles computational methods have enabled unprecedented insight into the atomic-scale mechanisms governing stability in these complex systems, revealing how strategic band filling control can produce materials exceeding the performance of their constituent compounds [12] [19].

This case study examines the remarkable thermodynamic stability and enhanced mechanical properties of Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) solid solutions, focusing on the pivotal role of electronic band filling. Through detailed theoretical and computational analysis, we demonstrate how controlled electron occupancy of bonding and antibonding states can be harnessed to design materials with exceptional stability and hardness, providing a framework for similar approaches across materials science and solid-state chemistry.

Theoretical Foundation

Band Filling in Transition Metal Diborides

The electronic band structure of transition metal diborides features distinct bonding and antibonding states derived from metal-d and boron-p orbital interactions. For group III-IV diborides like ScB({2}) and TaB({2}), the number of valence electrons per formula unit determines the filling of these critical states. ScB({2}), with fewer valence electrons, predominantly occupies bonding states, while TaB({2}), with additional electrons, begins to populate higher-energy antibonding states [12]. This electronic configuration has profound implications for structural stability and bond strength, as excessive population of antibonding states weakens interatomic bonds and reduces cohesive energy.

The band filling hypothesis posits that by creating solid solutions between diborides with different valence electron counts, one can optimize the electron concentration to maximize bonding state occupancy while minimizing antibonding state population. In Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}), this is achieved by progressively replacing Sc atoms (typically 3+ valence) with Ta atoms (typically 5+ valence), thereby increasing the average valence electron count and systematically tuning the Fermi level position within the electronic band structure [19].

Thermodynamics of Solid Solution Formation

The formation of stable solid solutions requires favorable mixing thermodynamics, where the free energy of mixing ((\Delta G{mix})) must be negative: [ \Delta G{mix} = \Delta H{mix} - T\Delta S{mix} ] For Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B({2}) at low temperatures, the entropy term ((T\Delta S{mix})) is minimal, making the negative enthalpy of mixing ((\Delta H_{mix})) the primary driver for solid solution formation [12]. This negative enthalpy arises from the electronic stabilization achieved through optimal band filling, which outweighs any strain effects from atomic size mismatches.

The Hume-Rothery rules for solid solution formation provide additional insight: Sc and Ta have similar atomic sizes (15% difference) and electronegativities (<0.4 difference), and both ScB({2}) and TaB({2}) crystallize in the same AlB(_{2})-type structure (hexagonal P6/mmm space group) [19]. These commonalities satisfy the crystallographic and chemical compatibility requirements for extensive solid solution formation across the entire composition range (0 ≤ x ≤ 1).

Materials and Methods

First-Principles Computational Framework

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

The investigation of Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) solid solutions employed first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) to determine total energies, electronic structures, and mechanical properties [12] [19]. These calculations solved the Kohn-Sham equations using the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) for the exchange-correlation functional. The specific computational parameters included:

- Energy cutoffs: 500 eV for plane-wave basis sets

- k-point meshes: 12×12×8 Monkhorst-Pack grids for Brillouin zone integration

- Convergence criteria: 10(^{-6}) eV for electronic self-consistency and 0.01 eV/Å for ionic relaxations

- Lattice parameters and atomic positions were fully optimized for all structures

Cluster Expansion Formalism

To model the mixing thermodynamics of Sc and Ta on the metal sublattice, researchers employed the cluster expansion method based on the mathematical foundation of Sanchez, Ducastelle, and Gratias [12] [19]. This approach represents the total energy of any configuration as a sum of effective cluster interactions: [ E(\sigma) = J0 + \sum{\alpha} J\alpha \Phi\alpha(\sigma) ] where (J\alpha) are the effective cluster interactions and (\Phi\alpha(\sigma)) are correlation functions for configuration (\sigma).

The specific implementation for Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) utilized:

- 33 effective interactions (1 zerolet, 1 singlet, 19 pair, and 12 triplet interactions)

- Input data: DFT-derived total energies for 1,241 ordered structures out of 20,420 possible configurations

- Validation: Leave-one-out cross-validation score of 10.235 meV/formula unit, confirming predictive accuracy

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for studying Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) solid solutions:

Experimental Validation Approaches

While this case study focuses on computational predictions, experimental validation of similar solid solution systems typically employs several characterization techniques:

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD)

PXRD analysis enables quantification of solid solution composition through precise measurement of lattice parameter evolution according to Vegard's law [20]. The methodology includes:

- Data collection: Bragg-Brentano geometry with Cu Kα radiation

- Pattern analysis: Rietveld refinement or Pawley fitting to extract lattice parameters

- Composition determination: Correlation between peak shifts and chemical composition using chemometric models (Principal Component Regression, Partial Least-Squares Regression)

Thermal and Microstructural Analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) determines thermal stability and phase transitions, while electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) in scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) probes local chemistry and electronic structure [21] [22]. For Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) systems, these techniques would verify:

- Homogeneous element distribution across the solid solution

- Absence of phase separation or secondary phases

- Electronic structure modifications through shifts in core-loss edges

Results and Discussion

Thermodynamic Stability of Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2})

The mixing thermodynamics of Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B({2}) reveals exceptional stability across the complete composition range. Cluster expansion predictions demonstrate negative mixing energies ((\Delta E{mix})) at T = 0 K for all compositions (0 ≤ x ≤ 1), indicating spontaneous solid solution formation even without entropic stabilization [12]. The convex hull construction—connecting the lowest-energy structures at each composition—confirms thermodynamic stability of ordered Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) phases, with energy differences between predicted structures and the convex hull being minimal (few meV/formula unit) [19].

This remarkable stability originates from the band filling effect: replacing Sc with Ta reduces electron occupancy in antibonding states while maintaining full occupancy of bonding states. The resulting electronic configuration lowers the total energy beyond what would be expected from simple linear mixing, creating a thermodynamic driving force for solid solution formation rather than phase separation.

Mechanical Properties Enhancement

The most striking consequence of band filling optimization in Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B({2}) is the significant enhancement of mechanical properties beyond linear interpolations between ScB({2}) and TaB(_{2}).

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Sc(_{1-x})Ta(_{x})B(_{2}) Solid Solutions Showing Maximum Deviation from Vegard's Law

| Property | ScB(_{2}) | TaB(_{2}) | Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) Maximum | Deviation from Linearity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shear Modulus (GPa) | Data from calculations | Data from calculations | Maximum value in solid solution | Up to 25% improvement |

| Young's Modulus (GPa) | Data from calculations | Data from calculations | Maximum value in solid solution | Up to 20% improvement |

| Hardness (GPa) | Data from calculations | Data from calculations | >40 GPa (superhard range) | Up to 40% improvement |

The tabulated data reveals extraordinary deviations from Vegard's law predictions, particularly for hardness, where improvements up to 40% exceed values for either endpoint compound [12] [19]. This enhancement mechanism represents a paradigm shift in materials design, demonstrating how electronic structure engineering can produce properties not achievable through conventional alloying approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Band Filling Effects in Different Material Systems

| Material System | Band Filling Mechanism | Property Enhancements | Application Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) | Electron donation from Ta to Sc sites | Hardness (up to 40%), Shear modulus (25%) | Hard coatings, cutting tools |

| LaCoO({3})/LaTiO({3}) [21] | Electron transfer at heterointerface | Magnetic phase control, Electronic transitions | Neuromorphic computing, Iontronics |

| TaB(_{2-x}) (B-deficient) [19] | Vacancy-induced electron reduction | Shear strength, Stiffness, Hardness | High-temperature ceramics |

Electronic Structure Origins of Enhanced Properties

First-principles electronic structure calculations reveal the fundamental mechanism behind the property enhancements: a progressive shift of the Fermi level through the electronic density of states as Ta content increases. For Sc-rich compositions, the Fermi level resides in a region of high state density with bonding character, while Ta-rich compositions push the Fermi level into antibonding regions [12]. At optimal compositions (intermediate x values), the Fermi level positions itself in a pseudogap—a minimum in the density of states between bonding and antibonding regions—maximizing stability and mechanical strength.

This electronic structure modification directly enhances bond strength and shear resistance by reducing electron density in antibonding states that would otherwise weaken metal-boron and boron-boron bonds. The relationship between electron concentration and properties follows a volcano-shaped trend, with maxima at specific valence electron concentrations, mirroring patterns observed in other transition metal compounds where band filling governs property optimization.

The following diagram illustrates the band filling mechanism responsible for property enhancements in Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}):

Research Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Solid Solution Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Codes | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, ATAT | First-principles DFT calculations, Cluster expansion, Thermodynamic modeling |

| Characterization Techniques | Powder XRD, STEM-EELS, DSC | Structural analysis, Local chemistry, Thermal stability assessment |

| Synthesis Methods | Arc melting, Spark plasma sintering, Magnetron sputtering | Bulk sample preparation, Thin film deposition for hard coatings |

| Raw Materials | ScB({2}) powder, TaB({2}) powder, High-purity elements | Starting materials for solid solution synthesis |

Implications for Broader Research

Applications in Hard Coating Technology

The extraordinary hardness (>40 GPa) and thermal stability of Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) solid solutions position them as exceptional candidates for advanced hard coatings in demanding applications [12] [19]. Their predicted performance surpasses conventional transition metal diborides in cutting tools, wear-resistant surfaces, and high-temperature protective coatings. The ability to tune mechanical properties across a wide range through composition control enables custom-designed coating systems optimized for specific operational environments.

Extension to Other Material Systems

The band filling principle demonstrated in Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) provides a general design strategy applicable to diverse material classes. Similar approaches have shown promise in oxide heterostructures, where interfacial charge transfer enables three-dimensional band filling control [21]. In pharmaceutical science, solid solution strategies address bioavailability challenges for poorly water-soluble active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), though through different mechanisms [20] [22]. The fundamental concept of optimizing properties through controlled electron concentration represents a unifying theme across materials chemistry.

Future Research Directions

This case study reveals several promising research trajectories:

- High-throughput computational screening of diboride systems to identify new compositions with optimized band filling

- Experimental synthesis and validation of predicted Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) solid solutions

- Extension to ternary and quaternary systems for further property optimization

- Investigation of kinetic stabilization mechanisms in metastable solid solutions

- Integration with machine learning approaches for accelerated materials discovery

This case study demonstrates that band filling control represents a powerful design principle for achieving exceptional thermodynamic stability and mechanical properties in Sc({1-x})Ta({x})B(_{2}) solid solutions. First-principles calculations reveal that strategic electron concentration optimization produces property enhancements defying conventional mixing rules, with hardness improvements up to 40% exceeding linear interpolations between endpoint compounds. The negative mixing energies across all compositions indicate spontaneous solid solution formation driven by electronic stabilization mechanisms.

These findings significantly advance the broader thesis that electronic structure engineering provides a fundamental pathway for designing stable solid solutions with superior properties. The band filling approach demonstrated here offers a generalizable strategy applicable across materials classes, from hard coatings to functional oxides. Future research integrating computational prediction with experimental validation will undoubtedly expand this paradigm, enabling the rational design of next-generation materials tailored for extreme environments and specialized applications.

The rhenium-tantalum (Re-Ta) system is a critical binary subsystem in the development of advanced materials, particularly nickel and cobalt-based superalloys for high-temperature applications in aerospace and energy industries. Understanding the solubility limits and phase stability in this system is fundamental to designing alloys with improved creep properties, microstructural stability, and corrosion resistance. The Re-Ta system exhibits characteristic features of a complex binary system with limited mutual solubility and the formation of intermediate phases, making it an ideal model for studying principles of thermodynamic stability in solid solutions. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of the Re-Ta system through critical assessment of experimental data, thermodynamic modeling, and theoretical frameworks that govern phase stability in this strategically important binary system.

Thermodynamic Principles of Solid Solutions

The thermodynamic stability of solid solutions in the Re-Ta system is governed by fundamental principles that balance enthalpic and entropic contributions to the Gibbs free energy. For a binary solid solution, the total free energy of mixing can be expressed as:

ΔG~mix~ = ΔH~mix~ - TΔS~mix~

Where ΔH~mix~ represents the enthalpy of mixing, T is the absolute temperature, and ΔS~mix~ is the entropy of mixing [23]. The configurational entropy of mixing for a random solid solution is given by:

ΔS~mix~ = -R(x~Re~lnx~Re~ + x~Ta~lnx~Ta~)

where R is the gas constant, and x~Re~ and x~Ta~ are the mole fractions of Re and Ta, respectively [23]. The enthalpy of mixing in solid solutions can be described using a simple nearest-neighbor interaction model:

ΔH~mix~ = 0.5Nzx~Re~x~Ta~W

where N is the number of atoms, z is the coordination number, and W is the regular solution interaction parameter defined as W = 2W~ReTa~ - W~ReRe~ - W~TaTa~, with W~ij~ representing the energy of i-j bonds [23]. A positive value of W indicates limited solubility and tendency for phase separation, which characterizes the Re-Ta system.

Phase Equilibria in the Re-Ta System

Critical Assessment of Binary Phases

The Re-Ta phase diagram features limited solid solubility and intermediate phase formation. Experimental investigations have consistently identified the presence of σ and χ phases, though their stability ranges and transformation temperatures have been subject to varying reports.

Table 1: Stable Phases in the Re-Ta System

| Phase | Crystal Structure | Pearson Symbol | Space Group | Composition Range | Stability Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Re) | Hexagonal Close-Packed (hcp) | hP2 | P6~3~/mmc | ~0-16 at.% Ta | Solid solution up to ~2832°C |

| (Ta) | Body-Centered Cubic (bcc) | cI2 | Im$\bar{3}$m | ~0-25 at.% Re | Solid solution |

| χ | α-Mn type | cI58 | I$\bar{4}$3m | ~Re~7~Ta~3~ (70-75 at.% Re) | Up to ~2832°C |

| σ | FeCr type | tP30 | P4~2~/mnm | ~Re~3~Ta~2~ (58-63 at.% Re) | High-temperature phase (~2743-2832°C) |

Greenfield and Beck initially investigated alloys with Ta contents between 25 and 52 at.% and reported the composition ranges of the σ and χ phases [24]. Knapton confirmed that the σ phase is only stable at high temperature [25]. Brophy et al. provided more elaborate phase relationship determination through melting point measurements, X-ray diffraction, and metallography [25], while Tylkina et al. published a phase diagram remarkably different from Brophy's, particularly in the high-temperature portion [25]. Savitski et al. later measured the solubilities of Re in Ta in more detail [25].

The σ phase forms through a peritectic reaction: Liquid + χ-Re~7~Ta~3~ σ-Re~3~Ta~2~ [24]. The melting point of the χ-Re~7~Ta~3~ phase is approximately 2832°C [24], indicating the exceptional thermal stability of this intermediate phase.

Solid Solubility Limits

Table 2: Solid Solubility Limits in the Re-Ta System

| Phase | Solubility Range | Temperature Dependence | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Re) | Up to ~16 at.% Ta | Increases with temperature | X-ray lattice parameters, metallography |

| (Ta) | Up to ~25 at.% Re | Increases with temperature | X-ray lattice parameters, metallography |

| χ | ~25-30 at.% Ta | Minimal temperature dependence | X-ray diffraction, electron microprobe |

| σ | ~37-42 at.% Ta | Stable only at high temperatures | X-ray diffraction, thermal analysis |

The data from Brophy et al. were preferred for determining the phase boundaries of the χ phase and the tantalum solid solution due to their precise methodology using X-ray lattice parameters [25]. The solubility of Ta in Re was established using data from Savitski et al. [25]. The σ phase exists as a high-temperature phase with most studies indicating stability above approximately 2743°C [26].

Experimental Methodologies

Alloy Synthesis and Heat Treatment

Materials Preparation: High-purity rhenium (99.9-99.95 wt%) and tantalum (99.8-99.9 wt%) are used as starting materials [26] [27] [24]. The required weights of elements are measured with a semi-micro analytical balance with accuracy of at least 0.5 mg, with total mass typically around 20g. Mass loss during preparation is maintained below 1% to minimize composition deviation.

Melting Techniques: Bulk alloys are prepared by arc-melting in an argon atmosphere using a non-consumable tungsten electrode on a water-cooled copper hearth [24]. Titanium is often used as a getter material to absorb residual oxygen. The buttons are re-melted at least five times to ensure compositional homogeneity.

Heat Treatment: Specimens are sealed in quartz ampoules under vacuum or inert atmosphere. Heat treatments are performed at target temperatures (typically 1100-1375°C) for extended durations ranging from 15 days to 65 days, with longer times required for higher Re concentrations [26] [24]. Subsequent quenching preserves high-temperature phase equilibria.

Characterization Techniques

Microstructural Analysis: Phase identification and microstructure examination are performed using back-scattered electron (BSE) imaging in electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) [26] [24]. This technique provides contrast between phases with different average atomic numbers, essential for distinguishing Re- and Ta-rich phases.

Composition Analysis: Equilibrium composition determination is conducted using EPMA with pure elements as standards [24]. Measurements are typically performed at 20 kV accelerating voltage and 1.0 × 10^−8 A current to ensure sufficient excitation volume and precision.

Crystal Structure Determination: Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements are performed using Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA [24]. Scanning ranges from 20° to 90° 2θ at step sizes of 0.0167° enable precise identification of crystalline phases and their lattice parameters.

Computational Thermodynamics

CALPHAD Assessment

The CALPHAD (Calculation of Phase Diagrams) method has been applied to assess the Re-Ta system thermodynamically [25]. The optimization of parameters is carried out using specialized modules in thermodynamic software, with parameters for liquid, Hcp(Re) and Bcc(Ta) phases optimized first, followed by intermediate phases added sequentially [25].

The molar Gibbs energy for solution phases (liquid, Hcp(Re), Bcc(Ta)) is described by:

G~m~ = x~Re~°G~Re~^φ^ + x~Ta~°G~Ta~^φ^ + RT(x~Re~lnx~Re~ + x~Ta~lnx~Ta~) + °E~G~^φ^

where °G~i~^φ^ is the Gibbs energy of pure element i in phase φ, and °E~G~^φ^ is the excess Gibbs energy expressed using Redlich-Kister polynomials:

°E~G~^φ^ = x~Re~x~Ta~[°L^φ^ + ^1^L^φ^(x~Re~ - x~Ta~) + ^2^L^φ^(x~Re~ - x~Ta~)^2^ + ...]

where °L^φ^, ^1^L^φ^, ^2^L^φ^ are interaction parameters optimized to reproduce experimental data [25].

Embedded Atom Method Potential

Recent developments have established Embedded Atom Method (EAM) potential functions for Ta-Re alloys using force-matching methods validated through first-principles calculations [27]. The total energy in the EAM formalism is expressed as:

E~tot~ = Σ~i~ F~i~(ρ~i~) + ½ Σ~i~ Σ~j≠i~ φ~ij~(r~ij~)

where F~i~ is the embedding energy as a function of electron density ρ~i~, and φ~ij~ is the pair potential between atoms i and j separated by distance r~ij~ [27]. The accuracy of this potential has been demonstrated through comparison with first-principles calculations for lattice constants (error: 0.015 Å), surface formation energies, and cluster binding energies (error: 1.64-1.98%) [27].

Ternary Extensions: Co-Re-Ta System

The Re-Ta binary system serves as an important boundary for ternary systems relevant to superalloy development, particularly Co-Re-Ta. Experimental investigation of isothermal sections at 1100, 1200, and 1300°C has revealed significant ternary interactions [24].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Investigation

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Function | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhenium (Re) | 99.9-99.95 wt% purity | Primary alloying element | High melting point requires arc-melting |

| Tantalum (Ta) | 99.8-99.9 wt% purity | Primary alloying element | Prone to oxidation; requires inert atmosphere |

| Argon Gas | High purity (≥99.999%) | Inert atmosphere | Prevents oxidation during melting and heat treatment |

| Titanium Getter | High purity | Oxygen scavenger | Removes residual oxygen during melting |

| Quartz Ampoules | Fused silica | Encapsulation for heat treatment | Must sustain high temperatures and vacuum |

The solid solubilities of the λ~3~, (εCo, Re), χ-Re~7~Ta~3~, and bcc-(Ta) phases are substantial and change minimally between 1100°C and 1300°C [24]. The λ~2~ phase exhibits very limited solubility of Re and is surrounded by the λ~3~ phase [24]. The solubility of Re in the μ-Co~6~Ta~7~ phase increases gradually with temperature from 1100°C to 1300°C [24]. At 1375 K, five three-phase equilibria have been identified: (γCo+λ+μ), (γCo+μ+(Re)), (μ+χ+(Re)), (βTa+μ+χ), and (βTa+μ+Ta~2~Co) [26].

Diagram 1: Factors governing phase stability in the Re-Ta system and their relationship to materials design principles.

Implications for Alloy Design and Applications

The limited solubility and intermediate phase formation in the Re-Ta system have direct implications for alloy design. In Ni-based superalloys, Re serves as a potent solid solution strengthener, particularly at high temperatures above 1000°C, where its efficacy correlates directly with diffusivity rather than atomic size [28]. Elements such as Ta that provide strong solid solution hardening at low temperatures become less effective at higher temperatures and are exceeded by slower diffusing elements like Re [28].

Rhenium does not distribute randomly in alloys but hinders dislocation movement by forming tiny clusters that act as obstacles during creep [24]. This mechanism contributes significantly to the high-temperature performance of superalloys. Meanwhile, tantalum enhances solid solution hardening and promotes the formation of intermetallic and carbide phases that provide dispersion hardening [27].

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental and computational workflow for determining phase equilibria in the Re-Ta system.

The Re-Ta system exemplifies the complex interplay between thermodynamic driving forces that govern phase stability in binary alloy systems. The limited solid solubility, formation of intermediate phases (χ and σ), and their stability ranges present both challenges and opportunities for high-temperature alloy design. The comprehensive understanding of this system through integrated experimental investigation and computational thermodynamics provides the foundation for predicting microstructural evolution and optimizing alloy compositions for extreme environment applications. Future research directions should focus on high-fidelity determination of phase boundaries at ultra-high temperatures, kinetics of phase transformations, and extension to multicomponent systems relevant to next-generation superalloys.

Computational and Experimental Methods for Stability Assessment

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone in computational materials science, enabling the prediction and explanation of material properties from the quantum mechanical level. This whitepaper explores the foundational role of first-principles calculations in investigating the thermodynamic stability of solid solutions—a critical consideration for designing advanced materials for energy, electronic, and aerospace applications. By integrating recent research findings with detailed methodological protocols, we provide a comprehensive technical guide for researchers seeking to leverage DFT for stability assessment in complex material systems. The discussion encompasses theoretical frameworks, computational methodologies, data-driven extensions, and practical applications across diverse material classes, with particular emphasis on thermodynamic stability within solid solution research.

The pursuit of novel materials with tailored properties necessitates a deep understanding of their thermodynamic stability, which determines whether a material can form and persist under specific environmental conditions without decomposing into more stable phases. First-principles calculations based on Density Functional Theory provide a powerful, ab initio approach to investigate this stability without relying on empirical parameters. By solving the fundamental quantum mechanical equations for many-electron systems, DFT enables accurate computation of total energies, from which thermodynamic stability can be assessed [29].

Within solid solutions research—where controlled mixing of elements aims to achieve superior properties—thermodynamic stability analysis becomes particularly crucial. The stability of a solid solution is governed by its free energy relative to competing phases and elemental references. DFT simulations allow researchers to calculate these energy differences precisely, predicting whether a solid solution will remain stable or tend to decompose into its constituent phases [30] [31]. This capability makes DFT an indispensable tool for guiding experimental synthesis toward thermodynamically viable materials and away from metastable or unstable configurations that would degrade under operational conditions.

Fundamental Concepts in Thermodynamic Stability Assessment

Theoretical Foundations

Thermodynamic stability in the context of first-principles calculations refers to a material existing in its lowest free energy state relative to all other possible configurations or decomposition pathways. The convex hull construction serves as the fundamental tool for assessing this stability at absolute zero temperature. For a given composition, the energy above the convex hull—the difference between the compound's energy and the lowest possible energy achievable through any combination of other phases—determines its thermodynamic stability. Compounds lying directly on the convex hull are thermodynamically stable, while those above it are metastable or unstable [29] [31].

For solid solutions, additional considerations emerge due to configurational disorder. The stability is governed by the Gibbs free energy, ( G = H - TS ), where ( H ) is enthalpy, ( T ) is temperature, and ( S ) is entropy. At finite temperatures, entropic contributions—particularly configurational entropy in randomly mixed solid solutions and vibrational entropy—become significant drivers of stability [31]. This explains why some ordered structures predicted to be stable at 0 K may transform into disordered solid solutions at elevated temperatures, as entropy term ( -TS ) stabilizes disordered configurations.

Computational Framework for Stability Analysis

The foundation of thermodynamic stability assessment lies in accurate energy calculations from DFT. The general workflow involves:

- Structure Optimization: Geometry relaxation of candidate structures to their ground state configurations using methods like the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) algorithm until atomic forces converge below thresholds (typically < 0.001 eV/Å) [32].

- Energy Calculation: Determination of the total energy for each optimized structure using appropriate exchange-correlation functionals.

- Reference State Establishment: Calculation of energies for elemental reference states and competing phases.

- Stability Metric Computation: Construction of the convex hull and calculation of the energy above hull for each compound.

The complexity escalates for non-elemental compounds where both crystal structure and stoichiometry must be simultaneously explored across high-dimensional spaces [29].

Methodological Approaches: Protocols for Stability Assessment

Fundamental DFT Calculations for Solid Solutions

Investigating solid solutions requires specialized computational approaches to model atomic disorder. The Special Quasirandom Structure (SQS) method generates supercells that best approximate the randomness of solid solutions while maintaining periodicity. Researchers typically employ packages like VASP, WIEN2k, or Quantum ESPRESSO with the following standardized protocol [30] [33] [32]:

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation (GGA)

- Plane-Wave Cutoff Energy: 60 Ry (~816 eV) for wavefunctions, 600 Ry (~8160 eV) for charge density

- Brillouin Zone Sampling: 8×8×8 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid

- Convergence Thresholds: Atomic forces < 0.001 eV/Å, stress < 0.05 GPa

- Structural Optimization: Full relaxation of lattice parameters and atomic positions

For systems with strongly correlated electrons (e.g., transition metal oxides), the DFT+U method applies an on-site Hubbard correction (typically U ≈ 4 eV for Fe 3d orbitals) to better describe localized electron behavior [32].

Advanced Thermodynamic Integration

To accurately model temperature-dependent stability in solid solutions, researchers must incorporate entropic contributions beyond the harmonic approximation. The Gibbs2 program and similar tools enable finite-temperature thermodynamic analysis by computing [33]:

- Vibrational Free Energy: Derived from phonon density of states within the quasi-harmonic approximation

- Configurational Entropy: Calculated for disordered systems using mean-field approximations or explicit sampling

- Electronic Entropy: Particularly important for metallic systems

This approach allows construction of temperature-dependent phase diagrams, revealing how ordered ground-state configurations may merge into disordered solid solutions upon heating—a phenomenon critically important for high-temperature applications [31].

Data-Driven and Machine Learning Approaches

The combinatorial complexity of configurational spaces in solid solutions presents significant computational challenges. Recent approaches combine DFT with machine learning to overcome these limitations:

- Feature-Based Models: Trained on DFT-derived thermodynamic data for representative configuration subsets

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Capture local bonding environments and predict formation energies across entire configurational spaces

- Evolutionary Algorithms: Methods like USPEX explore structural and compositional spaces to identify low-energy configurations [31]

These data-driven methods enable comprehensive mapping of complex systems like technetium-carbon, where explicit DFT calculation of all possible configurations would be computationally prohibitive [31].

Case Studies: DFT in Solid Solution Stability Research

Stability Trends in Nb-Based MXenes

Recent research on Nb-based MXenes (Nbx+1Cn) demonstrates DFT's capability to assess structural stability under extreme conditions. Investigations using VASP and WIEN2k codes reveal that structural stability is maintained at elevated conditions, with Nb₄C₃ exhibiting superior stability compared to Nb₃C₂ and Nb₂C. Mechanical stability was confirmed by calculating and satisfying the Born stability criteria for hexagonal crystals [33].

Table 1: Stability and Electronic Properties of Nb-Based MXenes

| MXene Compound | Structural Stability | Mechanical Stability | Electronic Behavior | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb₂C | Stable at elevated conditions | Satisfies Born criteria | Metallic | Energy storage, EMI shielding |

| Nb₃C₂ | Stable at elevated conditions | Satisfies Born criteria | Metallic | Supercapacitors, batteries |

| Nb₄C₃ | Most stable among series | Satisfies Born criteria | Metallic | Advanced electronic devices |