The Materials Genome Initiative: Accelerating Biomedical Innovation from Discovery to Clinical Deployment

This article explores the transformative impact of the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) on biomedical and materials research.

The Materials Genome Initiative: Accelerating Biomedical Innovation from Discovery to Clinical Deployment

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) on biomedical and materials research. It details the foundational paradigm of integrating computation, data, and experiment to halve the time and cost of materials development. For researchers and drug development professionals, we examine cutting-edge methodologies like Self-Driving Labs (SDLs) and AI-driven design, address critical troubleshooting in translating discovery to clinical application, and validate the approach with comparative case studies. The synthesis provides a roadmap for leveraging MGI's Materials Innovation Infrastructure to overcome traditional bottlenecks in developing advanced biomaterials, implants, and therapeutic delivery systems.

The MGI Blueprint: Foundations for a New Era of Materials-Driven Biomedicine

The creation and commercialization of advanced materials have long been the foundation of technological progress across sectors from healthcare and energy to defense and communications. Historically, however, the journey from initial discovery to market deployment has been an arduous process, typically requiring 20 or more years of iterative development [1]. This protracted timeline represents a critical bottleneck for global competitiveness, particularly as nations vie for leadership in emerging technologies. The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) was conceived as a transformative response to this challenge, establishing a bold vision to discover, manufacture, and deploy advanced materials at twice the speed and a fraction of the cost compared to traditional methods [2] [3] [1].

Launched in 2011 as a multi-agency U.S. government initiative, the MGI represents a fundamental paradigm shift in materials research and development (R&D) [4] [5]. Its name deliberately evokes the transformative potential of the Human Genome Project, applying a similar philosophy of coordinated, large-scale data generation and integration to materials science [2]. Rather than focusing solely on computational advancements, the MGI recognized that overcoming the 20-year development bottleneck required a holistic approach integrating computation, data, and experiment within a unified infrastructure—the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII) [6] [4]. This whitepaper examines the origins, strategic evolution, and technical implementation of the MGI framework, providing researchers with actionable methodologies for participating in this accelerated research paradigm.

The MGI Strategic Framework

Foundational Principles and Infrastructure

The MGI operates on the core premise that accelerating materials discovery, design, manufacture, and deployment requires the tight integration of computation, data, and experiment [6]. This integration is operationalized through the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII), a framework comprising integrated advanced modeling, computational and experimental tools, and quantitative data [3] [4]. The MGI paradigm promotes a fundamental departure from traditional linear development processes, instead emphasizing continuous iteration and information flow across all stages of the materials development continuum [4].

Table: The Evolution of MGI Strategic Goals

| 2011 Vision | 2014 Strategic Plan | 2021 Strategic Plan |

|---|---|---|

| Discover, manufacture, and deploy advanced materials twice as fast and at a fraction of the cost [1] | Establish policy, resources, and infrastructure to accelerate materials development [4] | Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure [3] |

| Create a "materials innovation infrastructure" [5] | Integrate computation, data, and experiment [4] | Harness the power of materials data [3] |

| Enhance U.S. competitiveness [4] | Develop the foundational elements of the MII | Educate, train, and connect the materials R&D workforce [3] |

Implementation Through Federal Coordination

As a multi-agency initiative, the MGI coordinates efforts across numerous federal entities, each contributing specialized capabilities and resources:

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Focuses on data and model dissemination, data quality, and data-driven materials R&D through initiatives like the Center for Hierarchical Materials Design (CHiMaD) and the Materials Genome Program [6] [5].

- National Science Foundation (NSF): Supports fundamental research primarily through the Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future (DMREF) program and Materials Innovation Platforms (MIPs) focusing on specific domains like semiconductors and biomaterials [6].

- Department of Defense (DOD): Invests in materials and manufacturing research with emphasis on defense applications, including autonomous material characterization and robot-human teaming for manufacturing [6].

- Department of Energy (DOE): Manages the Energy Materials Network, a community of practice advancing critical energy technologies through consortia leveraging National Laboratory capabilities [6].

Technical Pillars: Accelerating Materials Innovation

The Computational and Data Foundation

Early MGI successes were primarily computational, with initiatives such as The Materials Project, Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), and the Automatic FLOW for Materials Discovery database providing researchers with access to millions of calculated material properties [2]. These resources enabled virtual screening of candidate materials, significantly reducing the time and cost of identifying promising materials with target properties. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) has further enhanced these capabilities, enabling the development of predictive and surrogate models that can approximate physics-based simulations with significantly reduced computational requirements [4].

A critical lesson from MGI implementation is that the greatest successes have occurred in domains with mature theoretical frameworks and established software tools. For example, in metallic systems, the CALPHAD modeling approach has benefited from 50 years of steady improvement and widespread industrial adoption [6]. Similarly, approaches that begin with well-understood systems and employ iterative, physics-informed methods have demonstrated significant acceleration in materials development timelines [6].

Self-Driving Laboratories: The Experimental Revolution

While computational methods advanced rapidly, experimental validation remained a critical bottleneck due to reliance on manual procedures, limited throughput, and fragmented infrastructure [2]. Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) represent the most transformative development in overcoming this experimental limitation, serving as the missing experimental pillar of the MGI vision [2].

SDL architecture consists of five interlocking layers that enable autonomous operation:

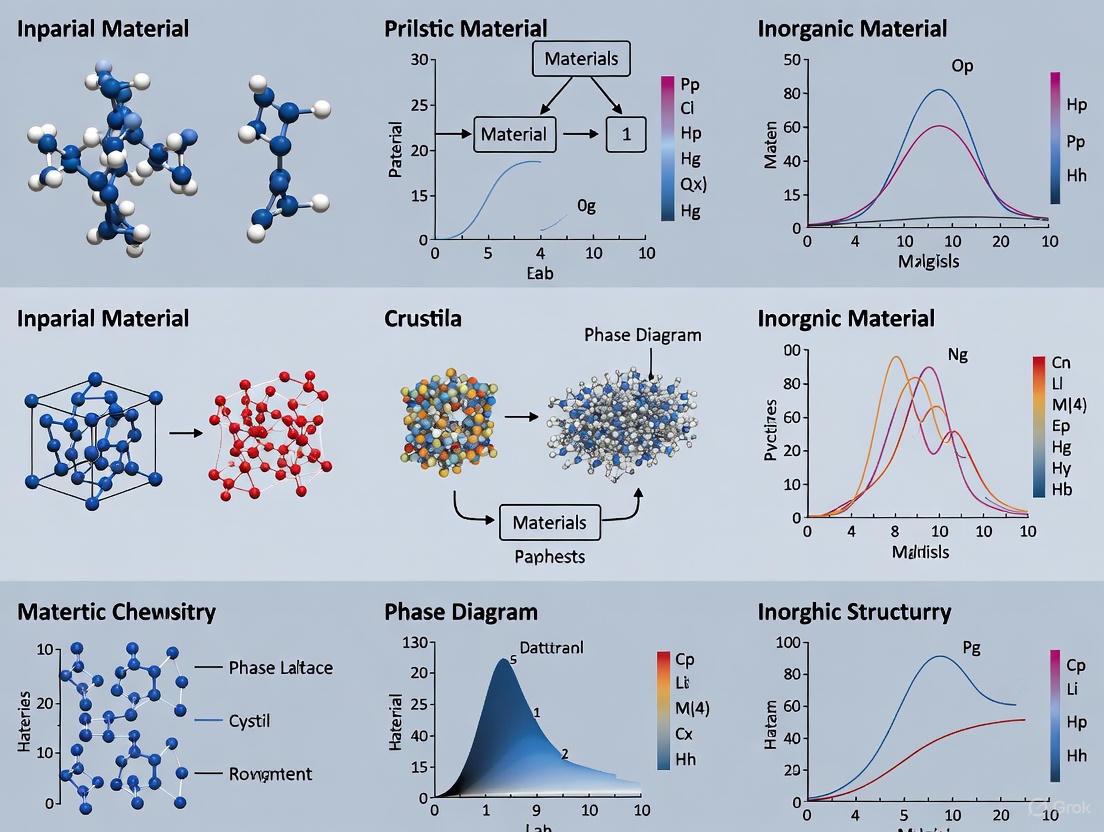

Diagram: The five-layer architecture of a Self-Driving Laboratory (SDL)

The autonomy layer distinguishes SDLs from traditional automation by incorporating AI-driven decision engines that plan experiments, interpret results, and update research strategies without human intervention [2]. Algorithms such as Bayesian optimization and reinforcement learning enable SDLs to efficiently navigate complex, multidimensional design spaces, while multi-objective optimization frameworks balance trade-offs between conflicting goals such as cost, toxicity, and performance [2].

SDL Implementation and Impact

In practical application, SDLs have demonstrated remarkable acceleration of materials discovery timelines. For example, an autonomous multiproperty-driven molecular discovery (AMMD) platform united generative design, retrosynthetic planning, robotic synthesis, and online analytics in a closed-loop format to autonomously discover and synthesize 294 previously unknown dye-like molecules across three design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles [2]. In other domains:

- Quantum dot synthesis: SDLs have mapped compositional and process landscapes an order of magnitude faster than manual methods [2].

- Polymer discovery: SDLs have uncovered new structure-property relationships previously inaccessible to human researchers [2].

- Battery development: Autonomous platforms can rapidly identify promising candidates, validate theoretical predictions, and flag anomalous behaviors worthy of deeper study [2].

These implementations demonstrate how SDLs can reduce time-to-solution by 100× to 1000× compared to conventional approaches, fundamentally altering the economics and pace of materials innovation [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SDL Workflow Implementation

The operational workflow of a Self-Driving Laboratory follows an iterative, closed-loop process that mirrors and amplifies the scientific method. This process enables continuous hypothesis generation, experimentation, and learning without human intervention:

Diagram: The closed-loop workflow of a Self-Driving Laboratory

This workflow operationalizes the DMTA cycle through automated, iterative processes. When given an end goal, the SDL designs and executes experiments using available materials libraries, synthesizes target materials, characterizes their properties, and iteratively refines its models using AI/ML until converging on optimal solutions [4]. The critical innovation lies in the continuous feedback between characterization and experimental design, allowing the system to adapt its research strategy based on emerging results.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

SDL platforms employ specialized reagents and instrumentation to enable autonomous operation. The table below details essential components and their functions in advanced materials research:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Materials Innovation

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Robotic Automation Systems | Liquid handling robots, robotic arms, automated transfer systems | Perform physical tasks such as dispensing, heating, mixing, and transferring materials between instruments [2] |

| In-situ Characterization Tools | Automated electron microscopy, inline spectroscopy, real-time sensors | Capture material properties and process data during experimentation without manual intervention [2] [7] |

| AI Decision Engines | Bayesian optimization algorithms, reinforcement learning, large language models | Plan experiments, interpret results, and update research strategies based on accumulated data [2] [7] |

| Data Management Infrastructure | Materials data repositories, provenance tracking, metadata standards | Store, manage, and share experimental data with complete digital provenance [2] [6] |

| Modular Synthesis Platforms | Flow chemistry reactors, automated vapor deposition, robotic synthesis | Execute material synthesis with precise control and reproducibility across diverse chemical processes [2] |

Deployment Models for SDL Infrastructure

Two primary deployment models have emerged for scaling SDL technologies, each offering distinct advantages for different research contexts:

- Centralized SDL Foundries: These facilities concentrate advanced capabilities in national laboratories or consortia, hosting high-end robotics, hazardous materials infrastructure, and specialized characterization tools. They offer economies of scale and serve as national testbeds for benchmarking, standardization, and training [2].

- Distributed Modular Networks: These systems deploy lower-cost, modular platforms in individual laboratories, offering flexibility, local ownership, and rapid iteration. When orchestrated via cloud platforms with harmonized metadata standards, they function as a "virtual foundry" that pools experimental results to accelerate collective progress [2].

A hybrid approach that combines both models offers the most promising path forward, allowing preliminary research to be conducted locally using distributed SDLs while more complex tasks are escalated to centralized facilities [2]. This layered approach mirrors cloud computing architectures and maximizes both efficiency and accessibility.

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Addressing Implementation Barriers

Despite significant progress, substantial challenges remain in fully realizing the MGI vision. Key implementation barriers include:

- Data and Model Gaps: Even in well-established domains like metallic systems, reliance on existing databases with limited coverage means necessary data is often unavailable. Acquiring experimental data to fill these gaps remains a critical bottleneck [6].

- Workforce Transformation: Developing an AI-ready scientific workforce with the skills to operate and leverage autonomous experimentation platforms requires significant educational evolution and training initiatives [7].

- Cultural and Incentive Structures: Academic and industrial reward systems still prioritize traditional publications over data and software sharing, creating disincentives for the collaborative approaches essential to MGI success [6].

- Interoperability Challenges: Integrating diverse robotic automation hardware and software with scientific equipment requires development of common API standards and communication protocols [7].

The 2024 MGI Challenges: Targeted Applications

To focus community efforts and demonstrate tangible impact, the MGI has identified five specific challenges that represent opportunities to apply MGI approaches to problems of national significance:

Table: The 2024 MGI Challenges and Their Potential Impact

| Challenge Area | Current Limitation | MGI-Enabled Future Vision |

|---|---|---|

| Point of Care Tissue-Mimetic Materials | Inadequate implant materials that don't match tissue properties | Design and deliver personalized biomaterials at bedside [8] |

| Agile Manufacturing of Multi-Functional Composites | Limited use due to insufficient design approaches | Dramatically reduce time and cost of composite design and manufacturing [8] |

| Quantum Position, Navigation, and Timing | Dependence on vulnerable GPS infrastructure | Enable flawless synchronization without satellite reliance [8] |

| High Performance, Low Carbon Cementitious Materials | Production generates 8% of global CO2 emissions | Rapidly design novel materials using local feedstocks [8] |

| Sustainable Semiconductor Materials | 25-year design and insertion timeline | Achieve material insertion in less than 5 years while building in sustainability [8] |

These challenges provide concrete targets for the materials community to demonstrate how integrated computational, data, and experimental approaches can accelerate solutions to critical national needs.

Future Outlook and Research Opportunities

The MGI is poised to make a transformative impact on how advanced materials are discovered, designed, developed, and deployed. Key frontiers for continued development include:

- Materials Digital Twins: Creating high-fidelity computational models that mirror physical materials and processes, enabling predictive design and virtual testing [4].

- Autonomous Experimentation Expansion: Broadening the application of SDLs across more materials classes and processes, with particular emphasis on sustainable and critical materials [2] [7].

- Workforce Development: Creating educational pathways and training programs to equip the next generation of materials researchers with skills in data science, AI, and autonomous systems operation [3] [7].

- National Infrastructure: Establishing a comprehensive Autonomous Materials Innovation Infrastructure that integrates capabilities across institutions and enables broad access to advanced tools [2] [7].

Continued progress will require sustained partnership between federal agencies, academia, and industry, with focused investment in the materials innovation infrastructure and alignment around national priorities. By maintaining this collaborative, integrated approach, the MGI represents America's most promising strategy for overcoming the 20-year materials development bottleneck and ensuring global competitiveness in advanced materials technologies [4].

The Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII) is the foundational framework of the U.S. Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), designed to accelerate the discovery, development, and deployment of advanced materials. Established as a national strategy to enhance global competitiveness, the MII integrates computational tools, experimental resources, and data infrastructure to reduce traditional materials development timelines from decades to years [6] [3]. This technical guide examines the MII's core components, operational methodologies, and implementation protocols that enable researchers to achieve unprecedented efficiency in materials innovation through integrated computational, experimental, and data science approaches.

The MII Framework and Strategic Context

The MGI was launched in 2011 with the ambitious goal of deploying advanced materials twice as fast and at a fraction of traditional costs [6]. The MII emerged as the operational embodiment of this vision—a suite of interdisciplinary tools and capabilities that support a fundamentally new approach to materials research and development [9]. This infrastructure represents a paradigm shift from sequential, trial-and-error methods to an integrated, data-driven methodology where computation, data, and experimentation converge in a tightly coupled system [6].

The 2021 MGI Strategic Plan established three primary goals, with the unification of the MII as the first and most fundamental objective [3]. This reflects the infrastructure's critical role in maintaining U.S. leadership in emerging materials technologies across vital sectors including healthcare, defense, energy, and communications [3]. The strategic imperative stems from the recognition that materials advancement underpins technological progress across all industrial sectors, and accelerating this process is essential for national security and economic competitiveness [6].

Core Components of the MII

The Materials Innovation Infrastructure comprises four interdependent pillars that collectively enable accelerated materials development through integrated workflows and data exchange.

Computational Tools Infrastructure

Computational resources form the predictive backbone of the MII, encompassing theory, modeling, simulation, and data analysis capabilities. These tools enable researchers to simulate material properties and behaviors before physical experimentation, dramatically reducing empirical trial-and-error.

- Physics-Based Modeling: Includes density functional theory (DFT), molecular dynamics, finite element analysis, and CALPHAD methods that model materials across length scales from atomic to continuum levels [6]

- Integrated Computational Materials Engineering (ICME): A well-established framework for computational materials design that has served for about two decades as a foundational approach within the MGI paradigm [6]

- Community and Commercial Codes: The MII leverages and builds upon national computational infrastructure by nurturing development of community codes and their incorporation into commercial software packages [9]

- AI and Machine Learning: Rapidly emerging capabilities that enable predictive modeling, pattern recognition in complex datasets, and autonomous experimental design [6]

Table: Computational Methods in the MII

| Method Type | Spatial Scale | Time Scale | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics | Ångströms - nanometers | Femtoseconds - picoseconds | Electronic structure, bonding, fundamental properties |

| Molecular Dynamics | Nanometers | Picoseconds - microseconds | Atomic-scale processes, diffusion, mechanical behavior |

| CALPHAD | Macroscopic | Equilibrium states | Phase diagrams, thermodynamic properties |

| Finite Element Analysis | Microns - meters | Milliseconds - hours | Stress analysis, heat transfer, performance simulation |

| Machine Learning | Cross-scale | Cross-temporal | Pattern recognition, prediction, experimental guidance |

Experimental Tools Infrastructure

The experimental pillar of the MII encompasses synthesis, characterization, processing, and manufacturing tools that generate empirical validation for computational predictions. Recent advances focus particularly on high-throughput and autonomous experimentation systems.

- Traditional Experimental Methods: Foundational techniques for material synthesis, processing, and characterization that provide critical validation data [9]

- High-Throughput Experimentation: Parallelized approaches that enable rapid screening of material compositions and processing conditions [6]

- Autonomous Experimentation: Self-driving laboratories (SDLs) that integrate robotics, artificial intelligence, and automated characterization to execute thousands of experiments with minimal human intervention [2]

- Advanced Characterization: Multimodal techniques that provide comprehensive structural, chemical, and functional property data across multiple length scales [9]

The MII specifically addresses barriers that limit access to state-of-the-art instrumentation for a diverse user community, including historically black colleges and universities and other minority-serving institutions [9]. This strategic inclusion aims to broaden participation in advanced materials research while strengthening the national workforce.

Data Infrastructure

The data layer of the MII provides the critical connective tissue that enables knowledge transfer, integration, and reuse across the materials community. This infrastructure encompasses both technical systems and governance frameworks for effective data management.

- FAIR Data Principles: Implementation of Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable data standards across materials research outputs [9]

- Data Repositories: Community-recognized platforms for storing and sharing materials data, including both public and restricted-access resources

- Data Standards and Protocols: Common formats, ontologies, and exchange protocols that enable interoperability between different systems and research groups [9]

- Provenance Tracking: Digital infrastructure that captures experimental and computational metadata to ensure reproducibility and context understanding

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has played a crucial role in developing the data aspects of the MII through its Materials Genome Program, which focuses on data and model dissemination, data and model quality, and data-driven materials R&D [6].

Integrated Research Platforms

Integrated platforms represent the operationalization of the MII philosophy, bringing together computational, experimental, and data resources within unified research environments. These platforms facilitate the collaborative, iterative workflows essential to accelerated materials development.

- Materials Innovation Platforms (MIP): NSF-developed ecosystems that establish scientific communities including in-house research scientists, external users, and other contributors who share tools, codes, samples, data, and knowledge [6]

- Energy Materials Network: DOE-established consortia focused on different high-impact energy technologies, each leveraging world-class capabilities at National Laboratories [6]

- Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs): Autonomous systems that integrate robotics, artificial intelligence, and digital provenance in closed-loop experimentation platforms [2]

These platforms create self-sustaining engines of materials discovery and development that can operate nimbly and rapidly in critical technology areas, currently including semiconductors and biomaterials [6].

MII Operational Architecture and Workflows

The MII enables specific operational methodologies that transform how materials research is conducted. The core innovation lies in replacing traditional linear development with integrated, iterative approaches.

The Closed-Loop Materials Innovation Cycle

The fundamental operational paradigm enabled by the MII is the continuous, iterative cycle of computational prediction, experimental validation, and model refinement. This "closed-loop" approach represents a significant departure from traditional sequential methods.

Diagram 1: MII Closed-Loop Workflow. This illustrates the iterative materials development process integrating computation, synthesis, characterization, and data analysis.

The DMREF (Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future) program—NSF's flagship MGI initiative—explicitly requires this "closed-loop" approach where "theory guides computational simulation, computational simulation guides experiments, and experimental observation further guides theory" [10]. This iterative refinement cycle enables increasingly accurate predictions and more efficient experimental targeting.

Self-Driving Laboratories Implementation

Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) represent the most advanced implementation of the MII operational paradigm, transforming physical experimentation into a programmable, scalable infrastructure [2].

SDL Technical Architecture:

- Actuation Layer: Robotic systems performing physical tasks (dispensing, heating, mixing)

- Sensing Layer: Sensors and analytical instruments capturing real-time data

- Control Layer: Software orchestrating experimental sequences and ensuring safety

- Autonomy Layer: AI agents planning experiments and updating strategies

- Data Layer: Infrastructure for storing, managing, and sharing data with provenance [2]

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Molecular Discovery

A representative SDL implementation for molecular discovery demonstrates the operational methodology:

- Generative Design: AI models propose candidate molecules with optimized target properties

- Retrosynthetic Planning: System identifies feasible synthesis pathways

- Robotic Synthesis: Automated platforms execute chemical synthesis

- Online Analytics: Real-time characterization measures obtained properties

- Model Retraining: New data updates predictive models for next design cycle [2]

This protocol enabled an autonomous multiproperty-driven molecular discovery platform to synthesize 294 previously unknown dye-like molecules across three design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles [2].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Materials Innovation

| Reagent/Category | Function in Experimental Workflow | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Synthesis Robots | Parallelized material preparation | Liquid handling systems for combinatorial chemistry |

| In-Line Spectrometers | Real-time property characterization | UV-Vis, NMR, Raman for molecular analysis |

| Automated Processing Equipment | Controlled material fabrication | Spin coaters, 3D printers, thermal processors |

| Machine-Learning Ready Datasets | Model training and validation | Curated data with standardized ontologies |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | Experimental strategy adaptation | Efficient navigation of complex parameter spaces |

Data Integration and Interoperability

The MII requires robust data integration frameworks to connect disparate tools and resources into a cohesive innovation ecosystem. This is operationalized through several key methodologies:

FAIR Data Implementation Protocol:

- Metadata Standards Development: Community-established schemas for experimental and computational provenance

- Automated Data Capture: Instrument integration that directly streams data to repositories with minimal manual intervention

- Ontology Development: Common terminologies that enable cross-domain data integration and knowledge representation

- API Ecosystem: Standardized interfaces that enable tool-to-tool communication and data exchange [9]

The MII specifically addresses the challenge of integrating public and private data repositories through pilot efforts in automated data workflows from experimental equipment to data repositories [9].

Implementation and Impact

Deployment Models and Infrastructure Access

The MII operates through multiple deployment models that balance capability with accessibility:

- Centralized SDL Foundries: Concentrate advanced capabilities in national labs or consortia with high-end robotics and specialized characterization tools [2]

- Distributed Modular Networks: Deploy lower-cost, modular platforms in individual laboratories with cloud-based orchestration [2]

- Hybrid Approaches: Combine local distributed SDLs for preliminary research with centralized facilities for complex tasks [2]

This layered approach maximizes both efficiency and accessibility, mirroring cloud computing architectures where local devices handle basic computation while data-intensive tasks are offloaded to specialized facilities.

Documented Acceleration and Impact

The MII methodology has demonstrated significant reduction in materials development timelines across multiple domains:

- Alloy Development: New alloys developed in a fraction of traditional time for use in U.S. Navy aircraft and coins produced by the U.S. Mint [6]

- Quantum Dot Synthesis: SDLs have mapped compositional and process landscapes an order of magnitude faster than manual methods [2]

- Polymer Discovery: Identification of new structure-property relationships previously inaccessible to human researchers [2]

The most successful implementations to date have occurred in materials domains with well-developed theoretical frameworks and mature software tools, particularly metallic systems benefiting from 50 years of steady improvement in CALPHAD modeling approaches [6].

Workforce Development and Cultural Transformation

Beyond technical infrastructure, the MII requires significant evolution in research culture and workforce capabilities. Successful implementation necessitates:

- Cross-Disciplinary Teams: Integration of theorists, computational scientists, data scientists, mathematicians, statisticians, and experimentalists [10]

- New Educational Models: Training programs that equip next-generation researchers with skills spanning traditional disciplinary boundaries [10]

- Cultural Shift: Movement beyond single investigators who "throw results over the wall" toward tightly integrated teams working hand-in-glove [6]

The DMREF program explicitly promotes "education, training, and workforce development that can communicate across all components of the materials development continuum" [10], recognizing that human factors are as critical as technical infrastructure for MII success.

Future Directions and National Strategy

The ongoing evolution of the MII focuses on addressing persistent challenges and expanding capabilities:

- Gap Identification and Bridging: Systematic identification of computational tool gaps, especially those presenting barriers to accessibility across the materials development continuum [9]

- National Materials Data Network: Development of a community-led alliance of data generators and users from product development through manufacturing to recycling [9]

- Autonomous Materials Innovation Infrastructure: Implementation of the vision articulated in 2024 MGI strategic documents for fully autonomous systems generating high-quality, reproducible data at scale [2]

- Grand Challenges: Use of focused national challenges to unify and promote adoption of the MII around critical technology needs [9]

The MII represents a foundational investment in U.S. competitiveness, creating the infrastructure needed to maintain leadership in materials technologies critical to health, defense, energy, and communications sectors [3]. By transforming materials development from a sequential process to an integrated, data-driven enterprise, the MII enables the acceleration necessary to meet emerging technological challenges and opportunities.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) is a multi-agency U.S. government initiative designed to create a new era of policy, resources, and infrastructure that enables institutions to discover, manufacture, and deploy advanced materials at twice the speed and a fraction of the cost compared to traditional methods [1] [11]. Launched in 2011, the MGI recognizes that advanced materials are fundamental to economic security and human well-being, with critical applications in sectors ranging from clean energy and national security to healthcare and communications [8]. The initiative was founded on the stark reality that moving a material from initial discovery to market deployment has traditionally taken 20 or more years [1]. Accelerating this pace is deemed crucial for achieving and maintaining global competitiveness in the 21st century [1].

This whitepaper traces the strategic evolution of the MGI from its launch to its current focus, framing it within a broader research context on securing technological leadership. It details the initiative's foundational goals, its strategic refinement in the 2021 Strategic Plan, and its operationalization through the concrete 2024 MGI Challenges. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this document provides a comprehensive technical guide to the MGI's framework, current priorities, and the detailed experimental methodologies it champions to overcome long-standing bottlenecks in materials development.

The 2011 Launch: A Vision for Acceleration

The MGI was inaugurated by President Barack Obama in June 2011, with a clear mission to help businesses "discover, develop, and deploy new materials twice as fast" [11]. The initiative's name draws an analogy to the Human Genome Project, reflecting its ambition to map the fundamental relationships between a material's structure, its processing, and its properties to enable predictive, in-silico design.

The core problem the MGI set out to address was the excruciatingly long and costly development timeline for new materials. This timeline hindered innovation across a wide range of industries. Since its launch, the U.S. Federal government has invested over $250 million in new research and development (R&D) and innovation infrastructure to anchor the use of advanced materials in existing and emerging industrial sectors [11]. This initial funding was aimed at building the foundational infrastructure and tools needed to shift materials science from a largely empirical, trial-and-error discipline to a more predictive and data-driven one.

Table: The Core Problem at MGI's Launch (2011)

| Aspect | Traditional Materials Development | MGI Vision |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline | 20+ years from discovery to market [1] [11] | Cut development time in half [1] [11] |

| Cost | High cost due to extensive physical experimentation | A fraction of the traditional cost [1] |

| Core Method | Empirical, trial-and-error | Predictive, data-driven design |

| Primary Goal | Establish a new infrastructure and culture for materials development | Accelerate U.S. competitiveness in advanced materials [1] |

The 2021 Strategic Plan: Refining the Framework for a New Decade

A decade after its launch, the MGI released a new strategic plan in 2021, refining its goals and approach for the next five years. This plan was built upon the infrastructure and lessons of the first decade and organized around three core, interconnected goals [3]:

- Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII): The MII is defined as a framework of integrated advanced modeling, computational and experimental tools, and quantitative data. The goal is to better integrate these components into a cohesive, accessible system for researchers.

- Harness the power of materials data: This focuses on maximizing the value of data generated throughout the research lifecycle. It emphasizes data standards, sharing, interoperability, and the use of data science to extract new insights.

- Educate, train, and connect the materials R&D workforce: Acknowledging that tools and data are only as good as the people using them, this goal aims to develop a skilled workforce capable of working across disciplines and leveraging the MII effectively.

This strategic plan underscored that achieving these goals is essential for U.S. competitiveness and will help ensure the nation maintains global leadership in emerging materials technologies for critical sectors, including health, defense, and energy [3].

MGI 2021 Strategic Framework

The 2024 MGI Challenges: Operationalizing the Strategy

In 2024, the MGI launched a series of concrete challenges to translate the 2021 strategic goals into actionable research and development programs. These challenges are designed to "help unify and promote adoption of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure" and are heavily focused on integrating new capabilities such as autonomy, artificial intelligence (AI), and robotics [8] [3]. The challenges serve as a "Call to Action" for the entire MGI community, including federal agencies, researchers, entrepreneurs, and industry leaders, to collaborate and drive forward solutions to problems of national interest [8].

The five 2024 MGI Challenges are:

- Point of Care Tissue-Mimetic Materials for Biomedical Devices and Implants: Aims to develop soft biomaterials that can be personalized and delivered at the bedside, addressing unmet clinical needs in areas like post-cancer surgery reconstruction [8].

- Agile Manufacturing of Affordable Multi-Functional Composites: Focuses on dramatically reducing the time and cost of designing and manufacturing safety-critical composite components for transportation, aerospace, and energy, enabling lighter-weight and higher-performance structures [8].

- Quantum Position, Navigation, and Timing on a Chip: Envisions enabling every device to synchronize flawlessly without reliance on vulnerable satellite-based GPS, enhancing national security, navigation, and commerce [8].

- High Performance, Low Carbon Cementitious Materials: Targets the rapid design of novel cementitious materials using locally-sourced feedstocks to drastically reduce the 8% of global CO2 emissions attributed to cement production, while improving durability and strength [8].

- Sustainable Materials Design for Semiconductor Applications: Aims to use AI-powered autonomous experimentation to slash the design and insertion timeline for new semiconductor materials from the usual 25 years to under 5 years, while also building in sustainability requirements from the outset [8]. This challenge is directly supported by a CHIPS Act funding opportunity anticipating up to $100 million in awards [3].

Table: Overview of the 2024 MGI Challenges

| Challenge Title | Key Problem | Envisioned Outcome | Targeted Sectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point of Care Tissue-Mimetics | Inadequate implant materials that don't match tissue properties [8] | Personalized biomaterials delivered at the bedside [8] | Healthcare, Biomedicine |

| Agile Composites Manufacturing | High cost and time of composite design/manufacturing [8] | Dramatically reduced time/cost for lightweight, high-performance structures [8] | Aerospace, Transportation, Energy |

| Quantum PNT on a Chip | Reliance on aging, disruptable GPS [8] | Flawless device synchronization without satellites [8] | National Security, Communications, Commerce |

| Low Carbon Cementitious Materials | Cement production generates 8% of global CO2 [8] | Rapid design of durable, strong, low-cost, low-carbon cement [8] | Construction, Infrastructure |

| Sustainable Semiconductor Materials | 25-year timeline for new semiconductor materials [8] | AI-driven design and insertion in under 5 years with built-in sustainability [8] | Semiconductors, Computing |

Technical Deep Dive: Methodologies and Tools

The 2024 MGI Challenges represent a significant shift towards highly integrated, data-driven, and automated R&D paradigms. The methodologies underpinning these challenges leverage the core components of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII).

Core Experimental and Computational Workflow

The approach to solving the MGI challenges moves away from linear, sequential experimentation towards a closed-loop, autonomous process. This workflow is central to initiatives like the "Sustainable Materials Design for Semiconductor Applications" challenge [8] [3].

Autonomous Materials Innovation Cycle

Step 1: AI-Driven In-Silico Design

- Objective: To generate candidate material compositions or structures with a high probability of meeting target specifications.

- Protocol: This phase uses foundational AI models trained on vast datasets of known material properties, quantum mechanics calculations, and existing experimental results. For example, similar to generative chemistry models in pharmaceuticals that predict the next atom in a molecule [12], materials models predict new stable compositions or microstructures. Techniques like density functional theory (DFT) calculations, molecular dynamics, and generative adversarial networks (GANs) are employed to explore the materials space virtually before any physical experiment is conducted.

Step 2: Autonomous/Robotic Synthesis and Processing

- Objective: To physically create the designed materials with minimal human intervention, ensuring high reproducibility and throughput.

- Protocol: This involves robotic platforms and automated laboratories (e.g., "Lab-as-a-Service" concepts [13]). These systems can perform tasks such as powder mixing, solution dispensing, thin-film deposition, and heat treatment based on digital recipes. The "Agile Manufacturing" challenge directly targets the development of such capabilities for composites [8]. This step transforms a digital design into a physical sample with precise and documented processing history.

Step 3: High-Throughput Characterization and Testing

- Objective: To rapidly evaluate the structure, properties, and performance of the synthesized materials.

- Protocol: Automated systems conduct parallel testing on multiple material samples. This can include high-throughput X-ray diffraction (XRD) for structural analysis, automated electron microscopy, robotic mechanical testers, and functional property measurements (e.g., electrical conductivity, catalytic activity). The data generated is structured and tagged automatically with metadata for traceability.

Step 4: Data Integration and Machine Learning

- Objective: To create a continuous learning loop where experimental data refines the AI models, improving the predictive accuracy for subsequent design cycles.

- Protocol: All data from design, synthesis, and characterization is fed into a centralized data repository. Machine learning algorithms, including Bayesian optimization and deep learning, analyze this data to identify correlations between processing parameters, structure, and properties. The model is then updated, and it suggests a new set of promising candidates or processing conditions for the next cycle, moving iteratively towards the optimal material [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental workflows for the MGI challenges rely on a suite of advanced tools and reagents that constitute the modern materials scientist's toolkit.

Table: Essential Tools for MGI-Driven Research

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AI/Modeling Platforms | Foundational chemistry models [12], Generative AI for in-silico screening [12] | Accelerates initial candidate identification and prioritization, predicting properties and performance. |

| Autonomous Experimentation | Robotic synthesis platforms, Automated laboratory robotics (e.g., Hamilton, Tecan) [14] | Enables high-throughput, reproducible synthesis and processing with minimal hands-on time. |

| High-Throughput Characterization | Automated XRD, Robotic SEM/TEM, Parallel mechanical testers | Rapidly collects structural and property data for many samples simultaneously. |

| Advanced Data Infrastructure | Materials data repositories, Cloud computing platforms, Data standards (e.g., XML, JSON schemas for materials data) | Stores, manages, and makes data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR). |

| Specialized Synthesis Reagents | High-purity precursor powders/chemicals, Custom polymer resins, Molecular inks for printing | Provides the fundamental building blocks for creating novel material compositions and forms. |

The strategic evolution of the MGI, from its 2011 vision to the focused 2024 Challenges, underscores a comprehensive and adaptive approach to securing U.S. leadership in advanced materials. This leadership is widely recognized as a cornerstone of economic competitiveness and national security in the 21st century [8] [1]. The initiative's progression shows a clear maturation: from building foundational awareness and infrastructure, to unifying that infrastructure through a strategic plan, and finally to deploying it against concrete, high-impact national problems.

The 2024 Challenges are not isolated scientific endeavors; they are strategically chosen to strengthen U.S. competitiveness across critical domains. For instance, developing "Sustainable Semiconductor Materials" is a direct response to the critical need for resilient and advanced supply chains in a sector fundamental to modern technology [8] [3]. Similarly, achieving "Agile Manufacturing of Multi-Functional Composites" has profound implications for maintaining leadership in aerospace and transportation [8]. The MGI's focus on accelerating the materials development timeline is, in essence, a strategy to accelerate the entire innovation cycle for countless downstream products and industries.

In conclusion, the MGI represents a paradigm shift in how materials research and development is conducted. By fostering a deeply integrated ecosystem of computation, data, experiment, and a skilled workforce, the MGI provides a powerful framework for addressing some of the world's most pressing technological and environmental challenges. For researchers and drug development professionals, engaging with the tools, data, and collaborative models promoted by the MGI is not merely an option but an imperative for remaining at the forefront of innovation and contributing to the global competitiveness of the U.S. and its allied industries. The journey from the 2011 launch to the 2024 Challenges demonstrates a sustained commitment to making this paradigm shift a reality.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) represents a fundamental shift in the approach to materials discovery and development, aiming to double the speed and reduce the cost of advancing materials from discovery to commercialization. Within the biomedical domain, this initiative takes on critical importance for addressing complex healthcare challenges through accelerated development of novel biomaterials, diagnostic tools, and therapeutic strategies. The synergistic partnership between the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and Department of Energy (DOE) creates an integrated federal ecosystem that spans the entire innovation continuum from basic research to clinical application. This whitepaper examines the distinct yet complementary roles of these agencies in advancing biomedical MGI objectives, with particular focus on their collaborative mechanisms, technical methodologies, and collective impact on U.S. global competitiveness in the biomedical sector.

Driven by increasing international competition in science and technology, this coordinated approach addresses urgent national needs. The United States remains the top global performer in research and development (R&D), with $806 billion in gross domestic expenditures on R&D in 2021 [15]. However, China, the second-highest R&D performer, closed the gap significantly with $668 billion in expenditures the same year [15]. The MGI framework provides a strategic response to this competitive landscape by unifying measurement science, computational tools, experimental resources, and data infrastructure across federal agencies to maintain U.S. leadership in emerging biomedical materials technologies.

Agency-Specific Roles and Quantitative Contributions

Each federal agency within the MGI ecosystem contributes unique capabilities, resources, and expertise that collectively address the complex challenges of biomedical materials development. The strategic alignment of these specialized roles creates a comprehensive innovation pipeline that accelerates the translation of basic research into clinical applications.

Table 1: Distinct Agency Contributions to Biomedical MGI Objectives

| Agency | Primary Role in MGI | Key Biomedical Focus Areas | Representative Funding/Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSF | Fundamental research in synthetic and engineering biology; Cross-disciplinary training | Gene circuit design, modular biological parts, regulatory networks | BRING-SynBio program; Smart Health and Biomedical Research programs [16] [17] |

| NIH | Translation to clinical applications; Biomedical validation and proof-of-concept | Point-of-care tissue-mimetic materials, diagnostic devices, therapeutic implants | Proof of Concept Network ($1.58B in additional funding); Small Business Programs ($13B economic impact) [8] [18] |

| NIST | Measurement science, standards development, data infrastructure | Data exchange protocols, materials quality assessment, reference data | Materials Resource Registry; Standard Reference Data; Advanced Composites Pilot [19] |

| DOE | High-performance computing, large-scale scientific facilities, energy-related materials | Autonomous experimentation platforms, AI-driven materials discovery | Request for Information on Autonomous Experimentation; CHIPS AI/AE funding [3] |

The economic impact of this coordinated approach is substantial. NIH investment alone drives significant private sector growth, with every $1.00 increase in publicly funded basic research stimulating an additional $8.38 of industry research and development investment after eight years [18]. The field of human genomics, built upon foundational projects like the Human Genome Project, now supports over 850,000 jobs and has a $265 billion total economic impact per year, yielding a return of investment of $4.75 for every $1 spent [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Economic Impacts of Federal Biomedical Research Investments

| Metric | Basic Research Impact | Clinical Research Impact | Genomics Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private Sector Leverage | $8.38 industry R&D per $1 public investment (after 8 years) | $2.35 industry R&D per $1 public investment (after 3 years) | $4.75 return per $1 invested |

| Economic Value | 43% return on public investment | N/A | $265 billion total economic impact annually |

| Employment | Supports foundation for 7M biomedical jobs | N/A | 850,000 direct and indirect jobs |

| Commercial Output | Fuels entry of new drugs to market | Proof of Concept Network created 100+ startups | Foundation for biotechnology and diagnostic industries |

Interagency Collaborative Frameworks and Technical Methodologies

The true power of the federal MGI ecosystem emerges through structured interagency collaborations that create seamless pipelines from fundamental discovery to clinical implementation. These partnerships leverage the unique capabilities of each agency to overcome specific translational barriers in biomedical materials development.

NSF-NIH Partnership: BRING-SynBio Program

The Biomedical Research Initiative for Next-Gen BioTechnologies (BRING-SynBio) program represents a sophisticated collaborative model between NSF and NIH that explicitly connects fundamental synthetic biology research with biomedical translation [16]. This program employs a structured two-phase approach:

Phase I (NSF-supported): Researchers pursue proof-of-principle synthetic and engineering biology research with emphasis on biological control theory. This phase focuses on fundamental advances in gene circuit designs that enhance robustness, reliability, predictability, and tuneability of current designs, alongside developing modular designs for biological parts that yield predictable network outcomes when combined [16].

Phase II (NIH-supported): Successful completion of Phase I milestones triggers administrative evaluation by NIH/NIBIB for transition to exploratory research that translates findings toward biomedical technologies. This phase builds directly on Phase I outcomes but focuses specifically on biomedical applications with clear relevance to NIBIB's mission [16].

This coordinated mechanism ensures that fundamental advances in synthetic biology incorporate biomedical application considerations from their inception, while simultaneously maintaining rigorous scientific standards through staged gatekeeping. The program specifically requires incorporation of biological control theory and addresses challenges with clear relevance to NIBIB's mission, creating a purposeful translational pathway rather than relying on serendipitous application of basic research findings [16].

MGI Challenge Areas with Multi-Agency Implementation

The 2024 MGI Challenges establish concrete biomedical objectives that engage capabilities across multiple agencies. The "Point of Care Tissue-Mimetic Materials for Biomedical Devices and Implants" challenge directly addresses clinical needs for personalized biomaterials that match native tissue properties, avoid immune responses, and can be delivered at the bedside in diverse healthcare settings [8]. This challenge requires integrated contributions from:

NIST: Development of standardized measurement protocols for tissue-mimetic material properties and performance metrics under physiological conditions [19].

NSF: Fundamental research on biomaterial-tissue interactions, signaling pathways, and design principles for synthetic extracellular matrices [16].

NIH: Validation of biocompatibility, functional performance in disease models, and eventual clinical trial design for regulatory approval [8].

DOE: Computational modeling of material behavior in biological systems and AI-driven design of patient-specific material formulations [3].

Technical Workflows for Accelerated Biomaterials Development

The biomedical MGI ecosystem employs integrated technical workflows that combine computational prediction, automated synthesis, high-throughput characterization, and machine learning optimization. This approach represents a fundamental departure from traditional sequential materials development by enabling rapid iteration between design, fabrication, and testing phases.

Autonomous Experimentation Workflow for Biomaterials:

Computational Design Phase: Researchers initiate the process with in silico design of biomaterial formulations using physics-based models and AI-driven generative design tools. DOE high-performance computing resources enable molecular dynamics simulations of material behavior under physiological conditions, while NIST reference data ensures accurate forcefield parameters and material properties [3] [19].

High-Throughput Synthesis: Automated platforms fabricate material libraries with systematic variation in composition, structure, and surface properties. For tissue-mimetic materials, this includes gradient hydrogels with varying crosslink densities, bioactive ligand presentations, and mechanical properties spanning physiological ranges [8].

Multi-scale Characterization: Automated characterization platforms measure structural, mechanical, and biological properties across length scales. NIST-developed standard protocols ensure data comparability across research institutions and commercial entities, which is critical for regulatory approval processes [19].

Biological Performance Screening: Advanced in vitro systems (organoids, tissue chips) and computational models evaluate cellular responses, immune compatibility, and functional integration. NIH validation frameworks assess performance against clinically relevant endpoints [8].

Machine Learning Optimization: Experimental data feeds back to refine computational models, identifying key structure-property relationships and optimizing subsequent design iterations. This closed-loop system progressively improves material performance while building predictive models for future development [3].

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Framework

The successful implementation of MGI approaches in biomedical research requires specialized reagents, computational tools, and standardized experimental protocols. These resources enable researchers to effectively navigate the complex landscape of biomaterials development while ensuring reproducibility and comparability across different research institutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomedical MGI Applications

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in MGI Workflow | Agency Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | NIST Standard Reference Materials for biomaterial properties | Calibration and validation of characterization instruments; Cross-laboratory data comparability | NIST [19] |

| Data Repositories | NIST Standard Reference Data; Materials Resource Registry | Critical evaluated scientific data for modeling; Resource discovery and interoperability | NIST [19] |

| Gene Circuit Components | Modular biological parts; Synthetic gene regulatory networks | Implementation of controlled biological responses in engineered tissues | NSF (BRING-SynBio) [16] |

| Computational Tools | μMAG micromagnetic modeling; CALPHAD phase diagram calculations | Prediction of material behavior and stability under physiological conditions | DOE/NIST [19] |

| Tissue-Mimetic Hydrogels | Gradient stiffness substrates; Bioactive peptide libraries | High-throughput screening of cell-material interactions | NIH Challenge Areas [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Tissue-Mimetic Material Development

The following protocol outlines a standardized methodology for developing point-of-care tissue-mimetic materials, reflecting the integrated approach championed by the MGI framework:

Phase 1: Computational Design and Prediction

Requirements Definition: Clinically-defined performance requirements including mechanical properties (elastic modulus: 0.5-20 kPa for soft tissues), degradation profile (30-90 days), and bioactivity specifications are established based on NIH challenge parameters [8].

Generative Design: DOE-developed AI algorithms generate potential material compositions using NIST reference data on polymer chemistry and biomaterial properties as training inputs. The algorithms optimize for multiple constraints simultaneously, including mechanical performance, manufacturability, and biological functionality [3] [19].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Candidate formulations undergo atomic-scale simulation using DOE high-performance computing resources to predict structural stability, hydration behavior, and interaction with biological macromolecules under physiological conditions [3].

Phase 2: Automated Synthesis and Characterization

High-Throughput Fabrication: Robotic dispensing systems prepare material libraries with systematic variation in composition (polymer concentration: 5-20% w/v), crosslinking density (0.1-5 mM crosslinker), and bioactive components (0.01-1 mM peptide ligands) [8].

Standardized Characterization: Automated testing platforms measure mechanical properties using NIST-calibrated instruments, surface chemistry via NIST Standard Reference Methods, and swelling behavior in physiological buffers. All data is formatted according to MGI data standards for repository submission [19].

Phase 3: Biological Validation

In Vitro Screening: Material libraries are screened against relevant cell types (primary human fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells) using high-content imaging to assess cell adhesion, viability, proliferation, and differentiation. NIH-provided reference cell lines ensure experimental consistency [8].

Performance Validation: Leading candidate materials undergo functional testing in disease-specific models (e.g., wound healing, muscle regeneration) following NIH-defined efficacy endpoints. Successful candidates advance to regulatory approval pathway for clinical testing [8].

Global Competitiveness Implications

The coordinated federal approach to biomedical MGI represents a strategic investment in U.S. leadership in the global biomedical arena. The integrated capabilities of NSF, NIH, NIST, and DOE create an innovation ecosystem that significantly accelerates the translation of basic research into clinical applications while stimulating economic growth.

International R&D competition continues to intensify, with several Asian economies demonstrating particularly rapid growth in research intensity. From 2011 to 2021, South Korea and Taiwan both doubled their R&D expenditures, while China surpassed Japan in 2009 and the combined R&D expenditures of the European Union countries in 2013 [15]. Although the United States increased R&D expenditures by 89% from 2011 to 2021, this growth was slower than South Korea, Taiwan, and China during the same period [15].

The MGI approach directly addresses this competitive challenge by creating unprecedented efficiency in materials development. Traditional materials development cycles typically require 20+ years from discovery to clinical implementation, particularly for complex biomedical applications requiring regulatory approval [8]. The MGI framework aims to compress this timeline dramatically through integrated computational design, autonomous experimentation, and standardized validation protocols. In semiconductor materials, a sector with similar development challenges, MGI-associated programs like CARISSMA aim to reduce the design and insertion timeline for new materials from 25 years to less than 5 years while building in sustainability requirements [8].

This accelerated timeline provides significant competitive advantages for U.S. biomedical companies and research institutions. The Proof of Concept Network supported by NIH has already demonstrated the commercial potential of this approach, helping academic innovators create over 100 startup companies and secure more than $1.58 billion in additional funding [18]. Similarly, the National Cancer Institute's small-business program generated $26.1 billion in economic output nationwide and added $13.4 billion in value to the U.S. economy [18].

The synergistic partnership between NSF, NIH, NIST, and DOE within the Materials Genome Initiative framework represents a transformative approach to biomedical materials development that significantly enhances U.S. global competitiveness. By integrating fundamental research capabilities, measurement science standards, translational pathways, and computational resources, this ecosystem addresses the complete innovation continuum from discovery to clinical implementation.

The structured collaborative mechanisms, particularly the BRING-SynBio program and MGI Challenge areas, create purposeful pathways for converting basic research advances into clinical solutions for pressing healthcare needs. The technical workflows that combine computational prediction, autonomous experimentation, and machine learning optimization fundamentally accelerate the development timeline while improving outcomes for complex biomedical challenges like point-of-care tissue-mimetic materials.

As international competition in science and technology continues to intensify, this coordinated federal approach provides a robust foundation for maintaining U.S. leadership in the biomedical sector while delivering significant economic returns and addressing critical healthcare challenges. The continued strategic alignment of agency-specific capabilities within the MGI framework will be essential for realizing the full potential of accelerated materials development in achieving national competitiveness objectives and improving human health.

The journey from a theoretical concept for a new material to its successful deployment in a commercial product is notoriously long, iterative, and expensive, often spanning 10 to 20 years [4] [1]. This protracted timeline creates significant bottlenecks for innovation in critical sectors such as energy, healthcare, defense, and communications. Within this development pathway lie the proverbial "valleys of death"—critical gaps where promising materials discoveries fail to transition to the next stage of development due to issues like scale-up challenges, funding shortages, or an inability to meet application-specific requirements [4] [20]. The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), launched in 2011, was conceived to address these very challenges. Its aspirational goal is to reduce the materials development cycle time and cost by 50% by creating a new paradigm for materials innovation [4] [21]. To effectively navigate the valleys of death and realize the goals of the MGI, a clear and systematic framework for assessing the maturity of a new material is essential. While Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) have long been used to measure the maturity of a system or technology, they do not specifically address the unique journey of a material itself. This gap is now being filled by the emerging framework of Materials Maturity Levels (MMLs), which provides a common scale for researchers, developers, and designers to evaluate and communicate the readiness of a new material [22] [20] [23].

Core Concepts: TRL and MML Frameworks

Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs)

Originally developed by NASA in the 1970s, the TRL framework is a systematic metric for assessing the maturity of a particular technology or system [20]. The scale ranges from 1 (basic principles observed) to 9 (system proven and deployed). Its primary focus is on the integration and demonstration of the technology within a system, with the reduction of system-level risk as its central theme [20].

Materials Maturity Levels (MMLs)

The MML framework is a complementary tool designed specifically to track the progression of a material from discovery to widespread acceptance. Proposed recently by Rollett and colleagues, the MML sequence ranges from 0 to 5, with each level representing a critical stage in the material's maturation [22] [23].

Table: The Materials Maturity Level (MML) Framework

| MML | Stage Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Theoretical Concept | A material with interesting properties is discovered via theory and/or numerical simulation [23]. |

| 1 | Material Exists | The material has been synthesized at the laboratory scale and is stable [23]. |

| 2 | Material Property Demonstrated | Large enough quantities have been produced and tested to establish potential for scale-up [23]. |

| 3 | Laboratory Use of Material Validated | The material's capability is verified and validated for limited application cases [23]. |

| 4 | Industry Use of Material Validated | The material is used by industry for a specific application and scale-up has been demonstrated [23]. |

| 5 | Material Fully Accepted | The material is used for more than one application, validated with publicly available test data [23]. |

The core value of the MML framework is that it de-risks a new material as a technology platform that can be applied to multiple systems and life cycles, rather than being tied to the requirements of a single, specific system [20]. This shift in perspective encourages a broader, more strategic investment in materials research and development.

The Critical Interplay Between TRLs and MMLs

The relationship between TRLs and MMLs is critical for understanding overall project risk. A high MML signifies that a material itself is well-understood, reliable, and producible. Introducing a high-MML material into a low-TRL system concept can significantly reduce early system-level risks [20]. Conversely, attempting to develop a new, low-MML material in parallel with a high-TRL system introduces substantial risk, often favoring the use of existing, mature materials instead. As articulated in recent literature, "a high MML platform provides increased agility, enhanced predictivity, and improved availability at lower cost to various systems during their life cycle" [20]. The following diagram illustrates the parallel progression of these two frameworks and their critical interplay across a system's life cycle.

The MGI and Frameworks for Crossing the Valleys of Death

The Materials Genome Initiative provides the essential infrastructure and philosophy to systematically address the valleys of death identified in the materials development continuum. The core of the MGI is the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII), a framework that integrates advanced modeling, computational tools, experimental tools, and curated digital data into a cohesive ecosystem [4] [3] [21]. The MGI promotes a paradigm shift from a traditional, sequential development process to an integrated, iterative one. This new paradigm, often called the MGI Paradigm, emphasizes seamless information flow and continuous feedback between all stages of the Materials Development Continuum (MDC)—from discovery and development to manufacturing and deployment [4]. This integrated approach is designed to accelerate learning and decision-making, thereby shortening the timeline and reducing the cost associated with moving from MML 0 to MML 5. Key MGI elements that directly support the traversal of the valleys of death include:

- Integrated Computational Materials Engineering (ICME): ICME uses computational solutions to solve practical problems in materials processing and manufacturing, which are central to advancing a material's MML [22].

- Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs): These are closed-loop systems that combine AI, robotics, and autonomous experimentation (AE) to design experiments, synthesize materials, characterize properties, and iteratively refine models without human intervention. SDLs can execute thousands of experiments in rapid succession, dramatically accelerating the optimization process and the early stages of materials maturation [4].

- Materials Digital Twins: These are AI/ML-generated surrogate models that can replace or augment physics-based models and simulations, allowing for rapid exploration of material behavior and performance under different conditions [4].

- The Co-Design Principle: A crucial element of the MGI approach is co-design, where the material and the application are developed hand-in-hand. This ensures that application requirements inform materials development from the earliest stages, and vice-versa, preventing costly re-developments and ensuring the final material meets real-world needs [22] [20].

Table: Essential Research Tools and Solutions for Accelerated Materials Development

| Tool/Solution | Primary Function | Role in MML Progression |

|---|---|---|

| AI/ML Predictive Models | Generate surrogate models and material digital twins for rapid property prediction. | Accelerates early-stage discovery (MML 0-1) and reduces need for physical experiments [4]. |

| Autonomous Experimentation (AE) | Uses AI and robotics to automate the design and execution of experiments. | Speeds up synthesis and characterization loops, crucial for MML 1-3 [4] [24]. |

| High-Throughput Computation | Rapidly calculate material properties from first principles for vast compositional spaces. | Enables large-scale virtual screening of new materials, foundational for MML 0 [4] [21]. |

| CALPHAD (Computational Thermodynamics) | Model and predict phase diagrams and thermodynamic properties of multi-component systems. | Informs process optimization and scale-up, key for MML 2-4 [22]. |

| Advanced Data Repositories | Curate, host, and provide access to materials data (e.g., Materials Project, Materials Data Facility). | Provides the "AI-ready" data essential for training models and establishing material trust (MML 3-5) [25]. |

Experimental Methodologies and Case Studies

A Generalized Protocol for MML Advancement

The following workflow, enabled by MGI principles, outlines a modern, iterative protocol for advancing a material's maturity. This process replaces traditional linear, sequential approaches.

Case Study: Success and Failure in Materials Maturation

Case 1: The CNT-Based Composite Success A prime example of a systematic, MGI-informed approach to crossing the valleys of death is the effort by NASA's US-COMP institute to develop carbon nanotube (CNT)-based composites. The project successfully generated CNT composites with substantially higher specific stiffness and strength compared to traditional carbon fiber composites [22]. This success was achieved by adopting MGI approaches, which integrated computational design, data mining, and targeted experimentation to navigate the complex path from theoretical prediction (high MML 0 potential) to a material with demonstrated superior properties (achieving high MML 2-3), ultimately for the purpose of enabling deep-space crewed missions [22].

Case 2: The Boron Arsenide (BAs) Failure In contrast, the development of boron arsenide illustrates a material that failed to cross a valley of death. BAs was identified through ab initio calculations as a promising candidate for thermal management due to its high thermal conductivity (MML 0) [22]. Multiple groups successfully synthesized the compound and validated its thermal properties at a small scale (progressing to MML 1). However, development reached an impasse when it became clear that the largest crystal that could be grown was limited to about 1 mm, a size insufficient for the intended application as heat sink substrates [22]. This is a classic failure in the transition from MML 1 to MML 2, where a fundamental processing limitation (the inability to scale up) prevented further maturation and deployment, despite promising initial properties.

The TRL and MML frameworks, when used in concert, provide a powerful and nuanced lens through which to view the entire technology and materials development pipeline. They allow stakeholders to precisely identify and communicate risk, not just of the system, but of the fundamental matter from which it is made. Within the overarching goal of the Materials Genome Initiative for global competitiveness, these frameworks are not just assessment tools; they are foundational to the new culture of materials research and development. The ongoing integration of artificial intelligence, self-driving laboratories, and a mature data infrastructure is poised to further transform this landscape. As these tools mature, the community is shifting its focus from simply accelerating individual experiments to engineering entire research workflows that are "born ready" for industrial scale, thereby systematically bridging the valleys of death [4] [20] [24]. The full realization of the MGI's vision depends on continued collaboration among federal agencies, national laboratories, academia, and industry, with strategic investments focused on building a robust Materials Innovation Infrastructure. This, in turn, will ensure that the development of advanced materials keeps pace with the accelerating cycles of technological innovation, securing future economic and national security [4].

AI, Self-Driving Labs, and Digital Twins: MGI's Toolkit for Biomedical Breakthroughs

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) represents a fundamental shift in materials research and development, aiming to discover, manufacture, and deploy advanced materials twice as fast and at a fraction of the cost compared to traditional methods [3]. Central to achieving this goal is the Self-Driving Lab (SDL)—an integrated, automated experimental framework that combines artificial intelligence, robotics, and high-throughput characterization. This technical guide delineates the five core technical layers composing a functional SDL architecture, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive blueprint for implementing these transformative systems within the MGI paradigm for enhanced global competitiveness.

The United States' competitiveness in critical sectors including health, defense, and energy depends on accelerated access to advanced materials [3]. The 2021 MGI Strategic Plan identifies three core goals to expand the initiative's impact: unifying the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII), harnessing the power of materials data, and educating the materials R&D workforce [19]. Self-Driving Labs represent the physical instantiation of this unified infrastructure, creating a closed-loop system where AI directs experiments, robotics executes them, and data flows continuously to inform subsequent cycles.

The architecture of an SDL must support this continuous operation while ensuring data integrity, security, and interoperability—all essential requirements within the MGI framework. By implementing the layered architecture described herein, research institutions can achieve the compression of discovery timelines evidenced in leading-edge studies, such as the AI-guided optimization of MAGL inhibitors that achieved a 4,500-fold potency improvement through rapid design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles [26].

The Five Technical Layers of a Self-Driving Lab

Layer 1: Planning & AI Decision Layer

The Planning & AI Decision Layer serves as the cognitive center of the SDL, where experimental objectives are translated into specific testable hypotheses and procedures.

Core Functions: