Targeted Materials Discovery Using Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX): A Revolutionary Framework for Accelerated Research

This article explores Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX), a transformative framework that is reshaping targeted materials discovery.

Targeted Materials Discovery Using Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX): A Revolutionary Framework for Accelerated Research

Abstract

This article explores Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX), a transformative framework that is reshaping targeted materials discovery. Traditional optimization methods often fall short when experimental goals require identifying specific subsets of a design space that meet complex, multi-property criteria. BAX addresses this by allowing researchers to define their goals through simple filtering algorithms, which are automatically converted into intelligent data acquisition strategies. We detail the foundational principles of BAX, its core methodologies—including InfoBAX, MeanBAX, and the adaptive SwitchBAX. The article provides a thorough analysis of its application in real-world scenarios, such as nanoparticle synthesis and magnetic materials characterization, and offers insights for troubleshooting and optimization. Furthermore, we present comparative validation against state-of-the-art methods, demonstrating significantly higher efficiency. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide serves as a comprehensive resource for leveraging BAX to accelerate innovation in materials science and biomedical research.

Beyond Simple Optimization: The Foundational Principles of BAX for Complex Material Goals

The Limitations of Traditional Bayesian Optimization in Materials Science

Bayesian optimization (BO) has established itself as a powerful, data-efficient strategy for navigating complex design spaces in materials science, enabling the discovery of new functional materials and the optimization of synthesis processes with fewer costly experiments [1]. Its core strength lies in balancing the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of known promising areas using a surrogate model and an acquisition function [2]. However, the traditional BO framework, which primarily targets the discovery of global optima (maxima or minima), faces significant limitations when confronted with the nuanced and multi-faceted goals of modern materials research [3] [4]. This document delineates these limitations and frames them within the emerging paradigm of Bayesian algorithm execution (BAX), which generalizes BO to target arbitrary, user-defined properties of a black-box function [5].

The central challenge is that materials design often requires finding specific subsets of a design space that satisfy complex, pre-defined criteria, rather than simply optimizing for a single extreme value [4]. For instance, a researcher might need a polymer with a specific melt flow rate, a catalyst with a hydrogen adsorption free energy close to zero, or a shape memory alloy with a transformation temperature near a target value for a specific application [6] [7]. Traditional BO, with its fixed suite of acquisition functions, is not inherently designed for such target-oriented discovery, creating a gap between algorithmic capability and practical experimental needs [6]. Furthermore, the closed-loop nature of BO, which assumes a pre-defined reward function, breaks down in realistic scientific workflows where the goal itself may evolve or be discovered during experimentation [3]. This article will explore these limitations in detail and provide practical protocols for adopting more flexible frameworks like BAX.

Core Limitations of Traditional Bayesian Optimization

The application of traditional BO in materials science reveals several critical shortcomings that can hinder its effectiveness in industrial and discovery-oriented research. The table below summarizes these key limitations.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Bayesian Optimization in Materials Science

| Limitation | Impact on Materials Discovery |

|---|---|

| Single-Objective Focus [4] [8] | Ineffective for multi-property goals common in materials design (e.g., high strength AND low cost AND high stability). |

| Assumption of a Pre-Defined Reward [3] | Struggles with open-ended discovery tasks where the target is unknown or must be inferred during experimentation. |

| Computational Scaling [8] | Becomes prohibitively slow in high-dimensional spaces (e.g., selecting from 30-50 raw materials), hindering rapid iteration. |

| Handling Complex Constraints [8] [7] | Difficulty incorporating real-world constraints (e.g., ingredient compatibility, manufacturability) directly into the optimization. |

| Interpretability [8] | Functions as a "black box," providing limited insight into the underlying structure-property relationships driving its suggestions. |

The Reward Function Problem and the Need for Human Intervention

A fundamental limitation of traditional BO is its assumption of a fixed, pre-defined reward function. In reality, scientific discovery is often an open-ended process. As noted in a perspective on autonomous microscopy, "BO is closed, and optimization is not discovery... BO assumes a reward function - a clearly defined target to optimize. That's often not how science works" [3]. This mismatch necessitates a human-in-the-loop approach, where scientists manually adjust reward functions and exploration parameters in real-time based on observed outcomes [3]. While effective, this intervention highlights the algorithm's inability to autonomously adapt to evolving scientific goals, especially in dynamic environments with multi-tool integration and adaptive hypothesis testing.

The Multi-Objective and Constraint Handling Challenge

Materials design is inherently multi-objective. A new battery electrolyte may need to maximize ionic conductivity while minimizing cost and toxicity, and satisfying constraints on chemical stability with the anode [8]. Traditional BO is fundamentally a single-objective optimizer. Extending it to multi-objective scenarios (Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization, or MOBO) substantially increases complexity, requiring multiple surrogate models and acquisition functions that integrate complex trade-offs [8]. Similarly, hard constraints, such as the sum of mixture components equaling 100% [7], are not natively handled and must be incorporated through probabilistic methods, which can be mathematically cumbersome and less accessible to materials scientists without deep machine learning expertise [8].

The Pitfall of Excess Knowledge in High-Dimensional Spaces

Counterintuitively, incorporating extensive expert knowledge and historical data can sometimes impair BO performance. A case study on developing a recycled plastic compound demonstrated that adding features derived from material data sheets to the surrogate model transformed an 11-dimensional problem into a more complex one [7]. The BO algorithm's performance degraded, performing worse than the traditional design of experiments (DoE) used by engineers. The study concluded that "additional knowledge and data are only beneficial if they do not complicate the underlying optimization goal," warning against inadvertently increasing problem dimensionality [7].

Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) as a Flexible Framework

Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) is a generalized framework that addresses the core rigidity of traditional BO. Instead of solely estimating the global optimum of a black-box function, BAX aims to estimate the output of any algorithm (\mathcal{A}) executed on the function (f) [5]. The experimental goal is expressed through this algorithm. For example, (\mathcal{A}) could be a shortest-path algorithm to find the lowest-energy transition path, a top-(k) selector to find the 10 best candidate materials, or a filtering algorithm to find all regions where a property falls within a specific range [4] [5].

The key advantage is that scientists can define their experimental goal using a straightforward algorithmic procedure, and the BAX framework automatically converts this into an efficient, sequential data-collection strategy. This bypasses the time-consuming and difficult process of designing custom acquisition functions for each new, specialized task [4]. Methods like InfoBAX sequentially choose queries that maximize the mutual information between the data and the algorithm's output, thereby efficiently estimating the desired property [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Optimization Frameworks

| Feature | Traditional BO | BAX Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Find global optima (max/min) | Estimate output of any algorithm (\mathcal{A}) run on (f) |

| Acquisition Function | Fixed (e.g., EI, UCB) [6] | Automatically derived from user's algorithm (e.g., InfoBAX) [4] |

| Experimental Target | Single point or Pareto front | Flexible subset (e.g., level sets, pathways, top-k) [4] |

| User Expertise Required | Understanding of acquisition functions | Ability to define a goal as a filtering/selection algorithm |

Application Note: Target-Oriented Materials Discovery

Experimental Goal and Protocol

This application note details a protocol for discovering a shape memory alloy (SMA) with a specific target phase transformation temperature of 440°C, a requirement for a thermostatic valve application [6]. The goal is not to find the alloy with the maximum or minimum temperature, but the one whose property is closest to a predefined value, a task ill-suited for standard BO.

Protocol: Target-Oriented Discovery using t-EGO

Problem Formulation:

- Input Space (x): Alloy composition (e.g., proportions of Ti, Ni, Cu, Hf, Zr).

- Black-Box Function (f): Experimentally measured transformation temperature for a given composition.

- Target (t): 440°C.

- Objective: Find the composition (x) that minimizes (|f(x) - t|).

Initial Data Collection:

- Perform a small number (e.g., 5-10) of initial experiments using a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) or based on historical data to establish a preliminary dataset.

Modeling Loop (Gaussian Process):

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model on the current dataset of compositions and their measured temperatures. The GP provides a predictive mean (\mu(x)) and uncertainty (s(x)) for any unmeasured composition [6].

Acquisition with Target-Specific Expected Improvement (t-EI):

- Instead of standard Expected Improvement (EI), calculate the t-EI acquisition function [6]:

- Let (y{t.min}) be the measured value in the current dataset closest to the target (t).

- Let (Y) be the random variable of the GP prediction at point (x).

- (t\text{-}EI = E[\max(0, |y{t.min} - t| - |Y - t|)]).

- This function values points that are expected to reduce the distance to the target.

- Instead of standard Expected Improvement (EI), calculate the t-EI acquisition function [6]:

Suggestion and Experimentation:

- Select the next composition to test by maximizing the t-EI function.

- Synthesize and characterize the chosen alloy to measure its true transformation temperature.

Iteration:

- Append the new data point (composition, temperature) to the dataset.

- Repeat steps 3-5 until a material is found whose transformation temperature is within an acceptable tolerance of the target (e.g., ±5°C) or until the experimental budget is exhausted.

Outcome

Applying this t-EGO protocol, researchers discovered the alloy (Ti{0.20}Ni{0.36}Cu{0.12}Hf{0.24}Zr_{0.08}) with a transformation temperature of 437.34°C in only 3 experimental iterations, achieving a difference of merely 2.66°C from the target [6]. This demonstrates a significant improvement over traditional or reformulated extremum-optimization approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and their functions in the described shape memory alloy discovery experiment.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Shape Memory Alloy Discovery

| Material / Component | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Titanium (Ti) | Base element of the shape memory alloy, fundamental to the martensitic phase transformation. |

| Nickel (Ni) | Base element; adjusting the Ni content is a primary method for tuning the transformation temperature. |

| Copper (Cu) | Alloying element; can be used to modify transformation temperatures and hysteresis. |

| Hafnium (Hf) | Alloying element; typically used to increase the transformation temperature and improve high-temperature stability. |

| Zirconium (Zr) | Alloying element; similar to Hf, it is used to raise transformation temperatures and influence thermal stability. |

| High-Temperature Furnace | Equipment for melting and homogenizing the alloy constituents under an inert atmosphere. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Characterization equipment used to accurately measure the phase transformation temperatures of the synthesized alloys. |

Advanced Protocol: Multi-Property Subset Estimation with BAX

For more complex goals involving multiple properties, the BAX framework provides a practical solution. This protocol is based on the SwitchBAX, InfoBAX, and MeanBAX methods for targeting user-defined regions in a multi-property space [4].

Protocol: Finding a Target Subset with BAX

Goal Definition via Algorithm ((\mathcal{A})):

- Define the target subset of the design space by writing a simple filtering function. For example, to find TiO₂ nanoparticle synthesis conditions that yield specific size and crystallinity:

Model Initialization:

- Define a probabilistic model (e.g., Gaussian Process) for each property of interest. With multiple correlated properties, a multi-task GP can be used.

BAX Execution Loop:

- Given the current dataset, draw samples from the posterior of the black-box function.

- For each function sample, run the algorithm (\mathcal{A}) to get a sample of the algorithm's output (the target subset).

- This generates a posterior distribution over the target subset.

Information-Based Query Selection (InfoBAX):

- Choose the next experiment point that maximizes the mutual information between the measurement and the algorithm's output. This is done by evaluating which point, on average, most reduces the uncertainty about the target subset.

Dynamic Strategy Switching (SwitchBAX):

- Implement SwitchBAX, which dynamically alternates between InfoBAX (effective in medium-data regimes) and MeanBAX (which uses the model's posterior mean and is effective with little data) without requiring parameter tuning [4].

Iteration:

- Perform the experiment at the selected point.

- Update the dataset and the models.

- Repeat until the target subset is identified with sufficient confidence.

This approach was successfully applied to navigate the synthesis space of TiO₂ nanoparticles and the property space of a magnetic material dataset, showing significantly higher efficiency in locating target regions compared to state-of-the-art methods [4].

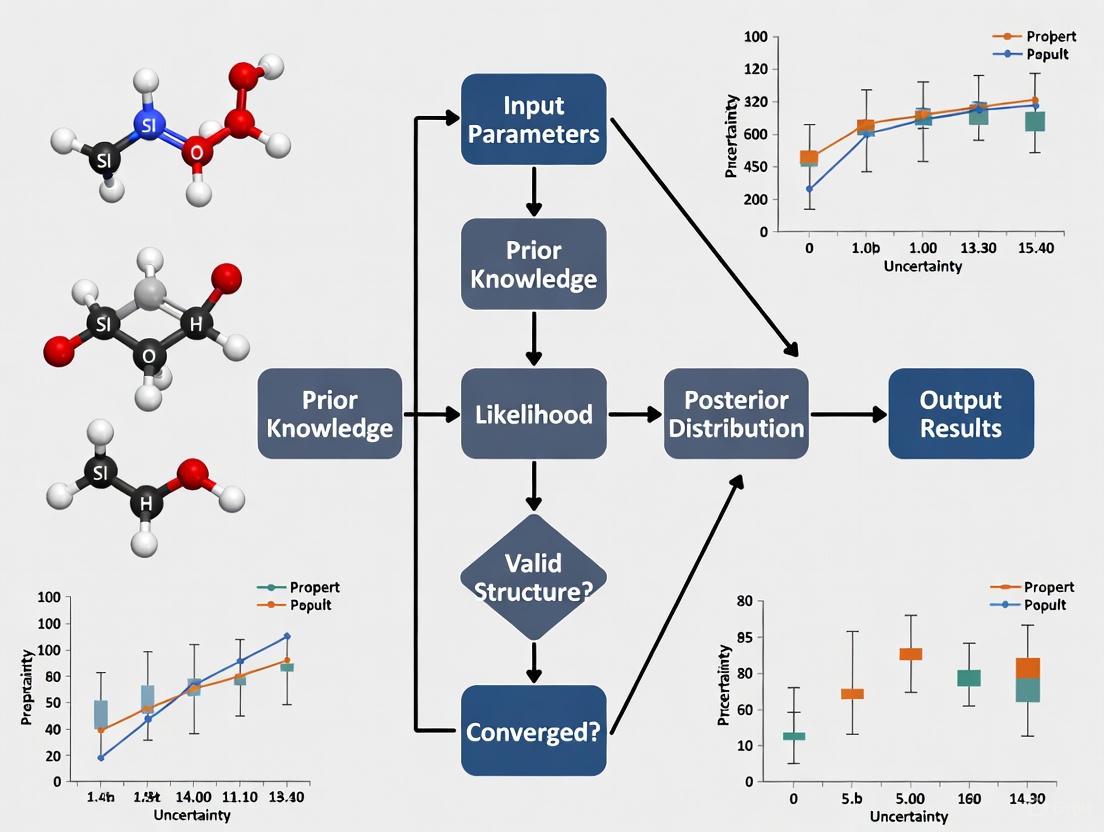

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key differences in workflow and focus between the traditional Bayesian optimization and the Bayesian Algorithm Execution paradigms.

Diagram 1: A comparison of the BAX and traditional BO workflows, highlighting the fundamental difference in how the experimental goal is defined and pursued.

Modern materials discovery and drug development require navigating vast, multi-dimensional design spaces of synthesis or processing conditions to find candidates with specific, desired properties. Traditional sequential experimental design strategies, particularly Bayesian optimization (BO), have proven effective for single-objective optimization, such as finding the electrolyte formulation with the largest electrochemical window of stability [4]. However, the goals of materials research are often more complex and specialized than simply maximizing or minimizing a single property. Scientists frequently need to identify specific target subsets of the design space that meet precise, user-defined criteria on multiple measured properties. This shift—from finding a single optimal point to discovering a set of points that fulfill a complex goal—defines the core problem that Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) is designed to solve [4].

Single-objective BO relies on acquisition functions like Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) or Expected Improvement (EI). For multi-property optimization, the goal shifts to finding the Pareto front—the set of designs representing optimal trade-offs between competing objectives. While this provides a set of solutions, it is a specific set constrained by Pareto optimality. Many practical applications require finding subsets that do not involve optimization at all, such as identifying all synthesis conditions that produce nanoparticles within a specific size range for catalytic applications or accurately mapping a particular phase boundary [4]. Developing custom acquisition functions for these specialized goals is mathematically complex and time-consuming, creating a significant barrier to adoption for the broader materials science community. The BAX framework addresses this bottleneck by automating the creation of custom acquisition functions, thereby enabling the targeted discovery of materials and molecules that meet the complex needs of modern research and development [4].

The BAX Framework: Translating Experimental Goals into Acquisition Strategies

Formal Problem Definition

The BAX framework operates within a defined design space, which is a discrete set of ( N ) possible synthesis or measurement conditions, each with dimensionality ( d ). This is denoted as ( X \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d} ), where a single point is ( \mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{d} ). For each design point, an experiment measures ( m ) properties, ( \mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^{m} ), constituting the measured property space ( Y \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times m} ). The relationship between the design space and the measurement space is governed by an unknown, true underlying function ( f{*} ), with measurements subject to noise: [ \mathbf{y} = f{}(\mathbf{x}) + \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \sigma^{2}\mathbf{I}) ] The core objective is to find the ground-truth target subset ( \mathcal{T}_{} = { \mathcal{T}{*}^{x}, f{}(\mathcal{T}_{}^{x}) } ), where ( \mathcal{T}_{*}^{x} ) is the set of design points whose measured properties satisfy the user's specific criteria [4].

From Algorithm to Acquisition Function

The innovative core of BAX is its method for capturing experimental goals. Instead of designing a complex acquisition function, the user simply defines their goal via an algorithm. This algorithm is a straightforward procedural filter that would return the correct target subset ( \mathcal{T}{*} ) if the underlying function ( f{*} ) were perfectly known. The BAX framework then automatically translates this user-defined algorithm into an efficient, parameter-free, sequential data collection strategy [4]. This bypasses the need for experts to spend significant time and effort on task-specific acquisition function design, making powerful experimental design accessible to non-specialists.

BAX Acquisition Strategies

The framework provides three primary acquisition strategies for discrete spaces common in materials science, all derived from the user's algorithm:

- InfoBAX: An information-based strategy that aims to reduce uncertainty about the target subset by evaluating points expected to provide the most information about the algorithm's output.

- MeanBAX: A strategy that uses model posteriors to estimate the target subset, often showing complementary performance to InfoBAX in different data regimes.

- SwitchBAX: A parameter-free strategy that dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX based on dataset size, ensuring robust performance across both small- and medium-data regimes [4] [9].

Application Notes: BAX in Action for Materials and Drug Discovery

Case Study 1: TiO₂ Nanoparticle Synthesis

Experimental Goal: Identify synthesis conditions that yield TiO₂ nanoparticles with a target size range and crystallinity phase for photocatalytic applications [4] [9].

BAX Implementation:

- Design Space (X): Combinations of precursor concentration, reaction temperature, and pH.

- Measured Properties (Y): Average particle size (nm) and phase (anatase vs. rutile).

- User-Defined Algorithm: A filter that selects all conditions where size is between 10-20 nm AND phase is anatase.

- BAX Strategy: The framework uses one of its acquisition strategies (e.g., SwitchBAX) to sequentially select the most informative experiments to run, efficiently zeroing in on the subset of conditions meeting these dual criteria.

Performance: Studies show that BAX methods were significantly more efficient at identifying this target subset than state-of-the-art approaches, requiring fewer experiments to achieve the same goal [4] [9].

Case Study 2: Functional Material Interrogation

Experimental Goal: Locate all processing conditions for a magnetic material that result in a specific range of coercivity and magnetic saturation values [4].

BAX Implementation:

- Design Space (X): Annealing temperature, time, and dopant concentration.

- Measured Properties (Y): Coercivity (Oe) and saturation magnetization (emu/g).

- User-Defined Algorithm: A filter that returns all conditions where coercivity is between 100-500 Oe AND saturation magnetization is greater than 50 emu/g.

- BAX Strategy: InfoBAX is used to reduce uncertainty about this target region in the property space, focusing measurements on the boundaries of the defined criteria.

Emerging Context: Accelerating Drug Discovery

The principles of BAX align closely with key trends in drug discovery, where the goal is often to find compounds meeting multiple criteria (e.g., high potency, good solubility, low toxicity) rather than optimizing a single property. The field is moving toward integrated, cross-disciplinary pipelines that combine computational foresight with robust validation [10]. BAX provides a formal framework for implementing such pipelines, enabling teams to efficiently find subsets of drug candidates or synthesis conditions that satisfy complex, multi-factorial target product profiles. This is particularly relevant for hit-to-lead acceleration, where the compression of timelines is critical [10]. Furthermore, the need for functionally relevant assay platforms like CETSA for target engagement validation creates ideal scenarios for BAX, where the goal is to find all compounds that show a significant stabilization shift in a specific temperature and dose range [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Defining a Target Subset Discovery Workflow Using BAX

Objective: To implement the BAX framework for the discovery of a target subset of materials synthesis conditions or drug candidates fulfilling multiple property criteria.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotic Platform: For automated synthesis or assay.

- Characterization Instrumentation: (e.g., Dynamic Light Scattering for nanoparticle size, XRD for phase, HPLC for compound purity).

- Computing Resource: Workstation with adequate CPU/GPU for running probabilistic models.

Procedure:

- Define the Design Space: Enumerate all possible experimental conditions (e.g., chemical compositions, processing parameters) as a discrete set ( X ).

- Specify Measured Properties: Identify the ( m ) properties ( Y ) to be measured for each experiment.

- Formulate the Goal as an Algorithm: Write a filtering function

filter_target_subset(X, Y)that returns the subset of ( X ) where the corresponding ( Y ) values meet all desired criteria (e.g.,if (size >= 10 and size <= 20) and (phase == 'anatase'):). - Initialize with a Small Dataset: Conduct a small, space-filling set of initial experiments (e.g., 5-10 points) to build a preliminary model.

- Sequential Data Acquisition Loop: a. Model Training: Train a probabilistic model (e.g., Gaussian Process) on all data collected so far. b. Point Selection: Use a BAX acquisition strategy (SwitchBAX, InfoBAX, or MeanBAX) to select the next most informative experiment ( \mathbf{x}{next} ). c. Experiment Execution: Perform the experiment at ( \mathbf{x}{next} ) to obtain ( \mathbf{y}{next} ). d. Data Augmentation: Add the new data point ( (\mathbf{x}{next}, \mathbf{y}_{next}) ) to the training set.

- Termination: Repeat steps a-d until the experimental budget is exhausted or the target subset is identified with sufficient confidence.

- Validation: Manually validate a subset of the discovered target points to confirm model predictions.

Protocol 2: Validation via Membrane Permeabilization Assay for BAX Protein

Objective: To validate the functional competence of recombinant monomeric BAX protein, a key reagent in studies of mitochondrial apoptosis, purified via a specialized protocol [11].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Intein-CBD Tagged BAX Construct | Enables expression and purification of tag-free, full-length BAX protein via affinity chromatography and intein splicing. |

| Chitin Resin | Affinity capture medium for the intein-CBD-BAX fusion protein. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent that induces the intein splicing reaction, releasing untagged BAX from the chitin resin. |

| Size Exclusion Column (e.g., Superdex 200) | Critical polishing step to isolate monomeric, functional BAX from aggregates or oligomers. |

| Liposomes (e.g., with Cardiolipin) | Synthetic membrane models used to assess BAX pore-forming activity in vitro. |

| BIM BH3 Peptide | A direct activator of BAX, used to trigger its conformational change and membrane insertion. |

| Cytochrome c | A substrate released during membrane permeabilization; its release is quantified spectrophotometrically. |

Procedure:

- Protein Purification: Express and purify full-length human BAX using the intein-chitin binding domain system and a two-step chromatography strategy as detailed in Chen et al. [11].

- Liposome Preparation: Prepare liposomes mimicking the outer mitochondrial membrane composition.

- Assay Setup: Incubate purified monomeric BAX protein (nM range) with liposomes in the presence or absence of its activator, BIM BH3 peptide (e.g., 1 µM).

- Incubation: Allow the reaction to proceed at a defined temperature (e.g., 30°C) for a set time (e.g., 60 minutes).

- Measurement: Quantify membrane permeabilization by measuring the release of encapsulated cytochrome c via absorbance at 550 nm or by a fluorescence dequenching assay.

- Analysis: Functional BAX will show activator-dependent cytochrome c release, confirming its competence to undergo activation and form pores.

Essential Tools and Visualizations

Logical Workflow of Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX)

Comparison of Data Acquisition Strategies

Table 1: A comparison of the key data acquisition strategies within the BAX framework and traditional methods.

| Strategy | Primary Mechanism | Best-Suited Data Regime | Typical Experimental Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| InfoBAX | Reduces uncertainty about the target subset | Medium-data regime | Complex subset discovery with multiple constraints |

| MeanBAX | Uses model posterior means for estimation | Small-data regime | Initial exploration and rapid subset identification |

| SwitchBAX | Dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX | All regimes (Parameter-free) | Robust performance across project lifecycle |

| Traditional BO (EI/UCB) | Maximizes an improvement or bound metric | Single-objective optimization | Finding a global optimum for a single property |

| Multi-Objective BO (EHVI) | Maximizes hypervolume improvement | Multi-objective optimization | Finding the Pareto-optimal front |

From Single Objective to Target Subset

The discovery and development of new materials are fundamental to advancements in numerous fields, including pharmaceuticals, clean energy, and quantum computing. However, this process is often severely limited by the vastness of the potential search area and the high cost of experiments. Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) has emerged as a powerful intelligent data acquisition framework that addresses this challenge by extending the principles of Bayesian optimization beyond simple maximization or minimization tasks. The BAX framework allows researchers to efficiently discover materials that meet complex, user-defined goals by focusing on the estimation of computable properties of a black-box function. This approach excels in scenarios where the experimental goal is not merely to find a single optimal point but to identify a specific subset of conditions that satisfy multiple precise criteria.

At its core, BAX reframes materials discovery as a problem of inferring the output of an algorithm. When an algorithm (e.g., for finding a shortest path or a top-k set) is run on an expensive black-box function, BAX aims to estimate its output using a minimal number of function evaluations. This is achieved by sequentially choosing query points that maximize information gain about the algorithm's output, a method known as InfoBAX. The framework is particularly suited for materials science, which typically involves discrete search spaces, multiple measured physical properties, and the need for decisions over short time horizons. By capturing experimental goals through straightforward user-defined filtering algorithms, BAX automatically generates efficient, parameter-free data collection strategies, bypassing the difficult process of task-specific acquisition function design.

Defining the Core Conceptual Triad

Design Space

The Design Space represents the complete, discrete set of all possible synthesis or measurement conditions that can be explored in a materials discovery campaign. Formally, it is defined as ( X \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d} ), where ( N ) is the number of possible conditions and ( d ) is the dimensionality corresponding to the different changeable parameters or features of an experiment. A single point within this space is denoted by a vector ( \mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{d} ).

- In Materials Science Context: In nanoparticle synthesis, the design space could encompass parameters such as precursor concentration, temperature, reaction time, and pH. In pharmaceutical development, it might include formulation variables like excipient ratios, processing temperatures, and mixing times. The design space is the domain over which researchers have direct control, and navigating it efficiently is the primary challenge of materials discovery.

- Role in BAX: The BAX framework is tailored for such typical discrete search spaces in materials research. The algorithm ( \mathcal{A} ), which encodes the experimental goal, operates over this design space.

Property Space

The Property Space encompasses the set of all measurable physical properties resulting from experiments conducted across the design space. It is denoted as ( Y \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times m} ), where ( m ) is the number of distinct properties measured for each design point. The measurement for a single point ( \mathbf{x} ) is a vector ( \mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^{m} ). These properties are linked to the design space through a true, noiseless underlying function, ( f{*} ), which is unknown prior to experimentation. Real-world measurements include an additive noise term, ( \epsilon ), leading to the relationship: [ \mathbf{y} = f{*}(\mathbf{x}) + \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \sigma^{2}\mathbf{I}) ]

- In Materials Science Context: For a nanoparticle synthesis experiment, the property space could include metrics such as particle size, size distribution (monodispersity), shape, and crystallographic phase. For a magnetic material, properties could include saturation magnetization and coercivity.

- Role in BAX: The probabilistic model in BAX is trained to predict both the value and the uncertainty of these properties (( \mathbf{y} )) at any point in the design space (( \mathbf{x} )). This model is crucial for guiding the sequential data acquisition process.

Target Subset

The Target Subset is the specific collection of design points, and their corresponding properties, that satisfy the user-defined experimental goal. It is formally defined as ( \mathcal{T}{*} = { \mathcal{T}{}^{x}, f_{}(\mathcal{T}{*}^{x}) } ), where ( \mathcal{T}{*}^{x} ) is the set of design points in the target region. This concept generalizes goals like optimization (where the target is a single point or a Pareto front) and mapping (where the target is the entire space) to more complex objectives.

- In Materials Science Context: An experimental goal might be to find all synthesis conditions that produce nanoparticles with a diameter between 5 and 10 nanometers and a specific crystalline phase. This combination of criteria defines the target subset. In pharmaceutical development, this could be the set of formulations that simultaneously achieve a desired drug release profile and adequate stability.

- Role in BAX: The fundamental objective of a BAX-driven experiment is to identify this target subset. The user defines their goal via a filtering algorithm that would return ( \mathcal{T}{*} ) if ( f{*} ) were known. The BAX framework then uses strategies like InfoBAX to sequentially select experiments that most efficiently reduce the uncertainty about this subset.

Logical and Data Relationships

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship and data flow between the Design Space, Property Space, and the Target Subset within the BAX framework.

BAX Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The BAX framework translates a user's experimental goal, expressed as an algorithm, into a practical data acquisition strategy. Several core methodologies have been developed for this purpose.

BAX Strategies: InfoBAX, MeanBAX, and SwitchBAX

InfoBAX: This strategy sequentially chooses queries that maximize the mutual information between the selected point and the output of the algorithm ( \mathcal{A} ). It works by running the algorithm on multiple posterior samples of the black-box function to generate potential execution paths. The next query is selected where the model expects to gain the most information about the algorithm's final output, effectively targeting the reduction of uncertainty about the target subset. InfoBAX is highly efficient in medium-data regimes.

MeanBAX: This method is a multi-property generalization of exploration strategies that use model posteriors. Instead of focusing on the information gain from the full posterior distribution, MeanBAX executes the user's algorithm on the posterior mean of the probabilistic model. It then queries the point that appears most frequently in these execution paths. This approach tends to perform well with limited data.

SwitchBAX: Recognizing the complementary strengths of InfoBAX and MeanBAX in different data regimes, SwitchBAX is a parameter-free strategy that dynamically switches between the two. This hybrid approach ensures robust performance across the full range of dataset sizes, from initial exploration to later stages of an experimental campaign.

Generalized BAX Experimental Protocol

The following workflow provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for applying the BAX framework to a targeted materials discovery problem. The corresponding diagram visualizes this process.

Protocol Steps:

- Define the Experimental Goal: Precisely specify the complex, multi-property criteria that a material must meet. Example: "Find all catalyst synthesis conditions yielding >90% conversion, >95% selectivity, and nanoparticle size between 2-5 nm."

- Encode Goal as an Algorithm (( \mathcal{A} )): Translate the goal into a straightforward computer algorithm (e.g., a filtering function). This algorithm takes the full property data ( Y ) as input and returns the set of design points ( \mathcal{T}_{*}^{x} ) that meet the criteria.

- Initialize a Probabilistic Model: Place a prior distribution over the black-box function ( f ) using a model like a Gaussian Process (GP), which can predict the mean and uncertainty of properties at unmeasured design points.

- Collect an Initial Dataset: Perform a small number (e.g., 5-10) of initial experiments, often selected at random from the design space, to seed the model with preliminary data.

- BAX Sequential Design Loop: Iterate until the experimental budget (e.g., number of synthesis attempts) is exhausted: a. Draw Posterior Function Samples: Generate a set of possible realizations of the black-box function ( f ) from the current model posterior, consistent with all data collected so far. b. Run Algorithm on Samples: Execute the user-defined algorithm ( \mathcal{A} ) on each of the posterior function samples. This produces a set of plausible execution paths and outputs for the algorithm. c. Compute Acquisition Function: For each candidate point ( x ) in the design space, calculate how much information querying that point would provide about the algorithm's output. In InfoBAX, this is the expected information gain (EIG). d. Select Next Experiment: Choose the design point ( x_{next} ) that maximizes the acquisition function.

- Perform Wet-Lab Experiment: Synthesize or process the material at the chosen condition ( x_{next} ) and characterize it to measure the relevant properties ( y ).

- Update the Model: Incorporate the new data point ( (x_{next}, y) ) into the probabilistic model, refining its predictions of the property space.

- Final Estimation: After the final iteration, the algorithm ( \mathcal{A} ) is run on the posterior mean of the fully updated model to produce the final estimate of the target subset ( \mathcal{T} ).

Quantitative Performance and Applications

BAX Performance in Materials Discovery Case Studies

The table below summarizes quantitative results from applying the BAX framework to real-world materials science datasets, demonstrating its efficiency gains over state-of-the-art methods.

| Application Domain | Experimental Goal / Target Subset | BAX Method Used | Performance Gain vs. Baseline | Key Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 Nanoparticle Synthesis [4] | Find synthesis conditions for specific nanoparticle sizes and shapes. | SwitchBAX, InfoBAX | Significantly more efficient | BAX methods achieved the same target identification accuracy with far fewer experiments than standard Bayesian optimization or random search. |

| Magnetic Materials Characterization [4] | Identify processing conditions that yield specific magnetic properties (e.g., coercivity, saturation magnetization). | InfoBAX, MeanBAX | Significantly more efficient | The framework efficiently navigated the multi-property space, reducing the number of required characterization experiments. |

| Shortest Path Estimation in Graphs [5] | Infer the shortest path in a graph with expensive edge-weight queries (an analogy for material pathways). | InfoBAX | Up to 500x fewer queries | InfoBAX accurately estimated the shortest path using only a fraction of the edge queries required by Dijkstra's algorithm. |

| Bayesian Local Optimization [5] | Find the local optimum of a black-box function (e.g., a reaction energy landscape). | InfoBAX | High data efficiency | InfoBAX located local optima using dramatically fewer queries (e.g., ~18 vs. 200+) than the underlying local optimization algorithm run naively. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key resources, both computational and experimental, central to implementing BAX for materials discovery.

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in BAX-Driven Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Model (e.g., Gaussian Process) | Computational | The core surrogate model that learns the mapping from the design space (X) to the property space (Y); it provides predictions and uncertainty estimates that guide the BAX acquisition strategy. |

| User-Defined Algorithm (( \mathcal{A} )) | Computational | Encodes the researcher's specific experimental goal (e.g., a multi-property filter); its output defines the target subset that BAX aims to estimate. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robot | Experimental | Automates the synthesis or processing of material samples at conditions specified by the BAX algorithm, enabling rapid iteration through the design of experiments. |

| Characterization Tools (e.g., XRD, SEM, NMR) | Experimental | Measures the physical properties (y) of synthesized materials, populating the property space and providing the essential data to update the probabilistic model. |

| BAX Software Framework (e.g., Open-Source BAX Libs) | Computational | Provides implemented, tested, and user-friendly code for InfoBAX, MeanBAX, and SwitchBAX strategies, lowering the barrier to adoption for scientists. |

| Design of Experiments (DOE) Software | Computational / Statistical | Used in preliminary stages or integrated with BAX for initial design space exploration and for understanding factor relationships, a principle also emphasized in Pharmaceutical Quality by Design [12]. |

The framework of Design Space, Property Space, and the Target Subset provides a powerful and formal lexicon for structuring complex materials discovery campaigns. By integrating these concepts with Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX), researchers gain a sophisticated methodology to navigate vast experimental landscapes with unprecedented efficiency. The ability to encode nuanced, multi-property goals into a simple algorithm, which BAX then uses to drive an intelligent, sequential data acquisition strategy, represents a paradigm shift from traditional one-size-fits-all optimization.

The demonstrated success of BAX strategies like InfoBAX and SwitchBAX in domains ranging from nanoparticle synthesis to magnetic materials characterization underscores their practical utility and significant advantage over state-of-the-art methods. This approach not only accelerates the discovery of materials with tailored properties but also lays the groundwork for fully autonomous, self-driving laboratories. As the required software and computational tools become more accessible and integrated with automated experimental platforms, the BAX framework is poised to become an indispensable component of the modern materials scientist's toolkit, ultimately accelerating the development of advanced materials for pharmaceuticals, energy, and beyond.

Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) is a framework that extends the principles of Bayesian optimization beyond the task of finding global optima to efficiently estimate any computable property of a black-box function [5]. In many real-world scientific problems, researchers want to infer some property of an expensive black-box function, given a limited budget of function evaluations. While Bayesian optimization has been a popular method for budget-constrained global optimization, many scientific goals involve estimating other function properties such as local optima, level sets, integrals, or graph-structured information induced by the function [5].

The core insight of BAX is that when a desired property can be computed by an algorithm (e.g., Dijkstra's algorithm for shortest paths or an evolution strategy for local optimization), but this algorithm would require more function evaluations than our experimental budget allows, we can instead treat the problem as one of inferring the algorithm's output [5]. BAX sequentially chooses evaluation points that maximize information about the algorithm's output, potentially reducing the number of required queries by several orders of magnitude [5].

Theoretical Foundations of BAX

Problem Formulation

Formally, BAX addresses the following problem: given a black-box function (f) with a prior distribution, and an algorithm (\mathcal{A}) that computes a desired property of (f), we want to infer the output of (\mathcal{A}) using only a budget of (T) evaluations of (f) [5]. The algorithm (\mathcal{A}) may require far more than (T) queries to execute to completion. The BAX framework is particularly valuable in experimental science contexts where:

- Measurements are expensive, time-consuming, or resource-intensive

- The design space is high-dimensional or complex

- Experimental goals go beyond simple optimization to include subset estimation and property characterization [4]

Information-Based Approaches

InfoBAX is a specific implementation of BAX that sequentially chooses queries that maximize mutual information with respect to the algorithm's output [5]. The procedure involves:

- Path Sampling: Running the algorithm (\mathcal{A}) on posterior function samples to generate execution path samples

- Acquisition Optimization: Using cached execution path samples to approximate expected information gain for candidate inputs

This approach is closely connected to other Bayesian optimal experimental design procedures such as entropy search methods and optimal sensor placement using Gaussian processes [5].

Table 1: Core BAX Methods and Their Characteristics

| Method | Key Mechanism | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| InfoBAX | Maximizes mutual information with algorithm output [5] | Medium-data regimes; information-rich sampling [4] |

| MeanBAX | Uses model posteriors for exploration [4] | Small-data regimes; initial exploration phases [4] |

| SwitchBAX | Dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX [4] | General-purpose; unknown data regimes [4] |

| PS-BAX | Uses posterior sampling; simple and scalable [13] | Optimization variants and level set estimation [13] |

BAX Implementation Framework for Materials Discovery

Formalizing Experimental Goals as Algorithms

The BAX paradigm enables scientists to express experimental goals through straightforward user-defined filtering algorithms, which are automatically translated into intelligent, parameter-free, sequential data acquisition strategies [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for materials discovery, where goals often involve finding specific subsets of a design space that meet precise property criteria [4].

In a typical materials discovery scenario, we have:

- A discrete design space (X \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}) of (N) possible synthesis or measurement conditions with (d) parameters each

- A measurement space (Y \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times m}) of (m) physical properties for each design point

- An unknown underlying function (f*) linking design space to properties: ( \mathbf{y} = f*(\mathbf{x}) + \epsilon ), where ( \epsilon ) represents measurement noise [4]

The experimental goal becomes finding the ground-truth target subset ( \mathcal{T}* = {\mathcal{T}^x, f_(\mathcal{T}_*^x)} ) of the design space that satisfies user-defined criteria [4].

BAX Workflow for Materials Research

Diagram 1: BAX Workflow for Materials Discovery

Application Protocols for Materials Discovery

Targeted Materials Discovery Protocol

Objective: Identify synthesis conditions producing TiO₂ nanoparticles with target size ranges (e.g., 3-5 nm for catalytic applications) [4].

Experimental Setup:

- Design Space: Discrete set of synthesis conditions (precursor concentration, temperature, reaction time)

- Property Space: Nanoparticle size, size distribution, crystallinity

- Target Subset: Conditions yielding nanoparticles in 3-5 nm range

BAX Implementation:

- Algorithm Definition: Define filtering algorithm that returns subset of conditions producing size in target range

- Model Selection: Employ Gaussian process surrogate model with appropriate kernels for different property types

- BAX Method Selection: Apply SwitchBAX for robust performance across experimental budget [4]

- Sequential Design: Iterate between model prediction and experimental validation

Validation Metrics:

- Target subset discovery efficiency

- Number of experiments required versus exhaustive screening

- Precision/recall in identifying target materials

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of BAX in Materials Discovery

| Application | Method | Performance Improvement | Experimental Budget Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ Nanoparticle Synthesis [4] | InfoBAX | Significant efficiency gain vs. random search | >50% reduction in required experiments |

| Magnetic Materials Characterization [4] | SwitchBAX | Outperforms state-of-the-art approaches | Substantial reduction in characterization needs |

| Shortest Path Inference [5] | InfoBAX | Accurate path estimation | Up to 500x fewer queries than Dijkstra's algorithm |

| Local Optimization [5] | InfoBAX | Effective local optima identification | >200x fewer queries than evolution strategies |

Multi-Property Materials Optimization Protocol

Objective: Discover materials satisfying multiple property constraints simultaneously (e.g., high conductivity AND thermal stability) [4].

Implementation Details:

Algorithm Specification:

Multi-Output Modeling: Use multi-task Gaussian processes or independent GPs for each property

Acquisition Strategy: Adapt BAX to handle multiple properties through weighted information gain or Pareto-front approaches

Experimental Validation: Prioritize candidates based on joint probability of satisfying all constraints

Research Reagent Solutions for BAX Experiments

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for BAX-Driven Materials Discovery

| Material/Reagent | Function in BAX Experiments | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors (e.g., Ti alkoxides) | Source of metal cations for oxide nanoparticle synthesis | TiO₂ nanoparticle discovery [4] |

| Solvents & Stabilizers | Control reaction kinetics and particle growth | Size-controlled nanoparticle synthesis [4] |

| Magnetic Compounds (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni oxides) | Provide magnetic properties for characterization | Magnetic materials discovery [4] |

| Structural Templates | Direct material assembly and morphology control | Porous materials and MOF discovery |

| Dopant Sources | Modify electronic and catalytic properties | Bandgap engineering and catalyst optimization |

Technical Implementation and Computational Infrastructure

BAX Algorithmic Components

Diagram 2: InfoBAX Algorithm Execution Process

Practical Considerations for Experimental Implementation

Computational Requirements:

- Surrogate model training and updating

- Execution path sampling for target algorithm

- Acquisition function optimization

Experimental Constraints:

- Batch selection for parallel experimentation

- Noisy measurements and experimental error

- Multi-fidelity data integration

Integration with Autonomous Experimentation:

- Robotic synthesis platforms

- High-throughput characterization tools

- Real-time data processing and decision making

Advanced BAX Methodologies and Recent Developments

Posterior Sampling for Scalable BAX

Recent advances in BAX have introduced PS-BAX, a method based on posterior sampling that offers significant computational advantages over information-based approaches [13]. Key benefits include:

- Computational Efficiency: Dramatically faster than information-based methods

- Theoretical Guarantees: Asymptotic convergence under appropriate conditions

- Implementation Simplicity: Easier to implement and parallelize

- Competitive Performance: Matches or exceeds performance of existing baselines across diverse tasks [13]

PS-BAX is particularly suitable for problems where the property of interest corresponds to a target set of points defined by the function, including optimization variants and level set estimation [13].

Multi-Objective and Constrained BAX

For complex materials discovery problems with multiple objectives or constraints, BAX can be extended through:

- Pareto Front Estimation: Modifying the base algorithm to identify non-dominated solutions

- Constraint Handling: Incorporating feasibility criteria into the filtering algorithm

- Preference Learning: Integrating user preferences into the acquisition strategy

The BAX paradigm represents a significant advancement in intelligent experimental design for materials discovery by providing a formal framework for translating diverse scientific goals into efficient data acquisition strategies. By treating experimental goals as algorithms and using information-theoretic principles to guide experimentation, BAX enables researchers to tackle complex materials discovery problems with unprecedented efficiency.

Future developments in BAX will likely focus on improved computational efficiency through methods like PS-BAX [13], integration with multi-fidelity experimental frameworks, and application to increasingly complex materials systems spanning multiple length scales and property domains. As autonomous experimentation platforms become more sophisticated, BAX provides the mathematical foundation for fully adaptive, goal-directed materials discovery campaigns.

The process of discovering new therapeutic materials is notoriously challenging, characterized by high costs, low success rates, and vast, complex design spaces. In this context, Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) emerges as a powerful strategic framework that uses intelligent, sequential data acquisition to navigate these challenges efficiently [4]. Originally developed for targeted materials discovery, the principles of BAX are directly transferable to biomedical research, where the goal is often to identify specific candidate molecules or materials that meet a precise set of property criteria, such as high binding affinity, low toxicity, and optimal solubility [4] [14].

This framework is particularly valuable because it moves beyond simple single-objective optimization. Drug discovery is inherently a multi-objective optimization problem; a molecule with excellent binding affinity is useless if it is too toxic or cannot be dissolved in the bloodstream [14]. BAX captures these complex experimental goals through user-defined filtering algorithms, which are automatically translated into efficient data collection strategies. This allows researchers to systematically target the "needle in the haystack"—the small subset of candidates in a vast chemical library that possesses the right combination of properties to become a viable drug [4]. By significantly reducing the number of experiments or computational simulations required, BAX accelerates the critical early stages of research, helping to bridge the gap between initial screening and experimental validation.

Core BAX Methodologies and Their Drug Discovery Applications

The BAX framework encompasses several specific strategies tailored to different research scenarios. The table below summarizes the core BAX algorithms and their relevance to drug discovery.

Table 1: Core BAX Algorithms and Their Applications in Drug Discovery

| BAX Algorithm | Core Principle | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| InfoBAX [4] | Selects experiments that maximize information gain about the target subset. | Ideal for the initial exploration of a new chemical space or protein target to rapidly reduce uncertainty. |

| MeanBAX [4] | Uses the model's posterior mean to guide the selection of experiments. | Effective in data-rich regimes for refining the search towards the most promising candidates. |

| SwitchBAX [4] | Dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX based on performance. | Provides a robust, parameter-free strategy that performs well across different dataset sizes. |

| Preferential MOBO [14] | Incorporates expert chemist preferences via pairwise comparisons to guide multi-objective optimization. | Captures human intuition on trade-offs between properties (e.g., affinity vs. toxicity), aligning computational search with practical drug development goals. |

These strategies address a key bottleneck in virtual screening (VS), a computational method used to sift through libraries of millions to billions of compounds. Traditional VS is resource-intensive, and a significant disconnect exists between top-ranked computational hits and the compounds human experts would select based on broader criteria [14]. Frameworks like CheapVS (CHEmist-guided Active Preferential Virtual Screening) build on preferential multi-objective BAX to integrate expert knowledge directly into the optimization loop. This ensures that the computational search prioritizes candidates not just on a single metric like binding affinity, but on a balanced profile that includes solubility, synthetic accessibility, and low toxicity, thereby making the entire process more efficient and aligned with real-world requirements [14].

Experimental Protocol: Integrating BAX-Guided Virtual Screening

This protocol details the application of a BAX-based framework for a multi-objective virtual screening campaign to identify promising drug leads.

Stage 1: Problem Formulation and Initial Setup

- Define the Target Subset: Precisely specify the criteria for a successful candidate. For example:

binding_affinity(ligand) ≤ -9.0 kcal/mol AND toxicity(ligand) = 'low' AND solubility(ligand) ≥ -4.0 LogS[4] [14]. - Select the BAX Strategy: Choose an acquisition strategy (e.g., SwitchBAX for a robust, general approach or Preferential MOBAX if expert feedback is available) [4] [14].

- Prepare the Data: Assemble the molecular library (e.g., 100,000+ compounds). Generate or gather initial data by measuring or computationally predicting the key properties (e.g., binding affinity, solubility) for a small, randomly selected subset (e.g., 0.5-1% of the library) to serve as the initial training data [14].

Stage 2: Iterative BAX Optimization Loop

- Model Training: Train a probabilistic machine learning model (e.g., a Gaussian Process) on all data collected so far to predict the properties of interest and the associated uncertainty for every compound in the library [4].

- Algorithm Execution: Run the user-defined algorithm (from Step 1.1) on thousands of hypothetical property sets sampled from the model's posterior. This estimates the "target subset" for each sample [4].

- Acquisition and Experiment: Use the BAX acquisition function (e.g., InfoBAX) to identify the single most informative compound(s) whose experimental evaluation would best refine the understanding of the target subset. Perform the costly property evaluation (e.g., a precise binding affinity calculation) only on this select few compounds [4] [14].

- Data Augmentation: Add the new experimental results to the training dataset.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2.1 to 2.4 until the experimental budget is exhausted or the target subset is identified with sufficient confidence.

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the iterative cycle of the BAX-guided virtual screening protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental validation of BAX-identified hits, particularly in biochemical assays, often requires specialized reagents. The following table details key materials for studying a critical apoptotic protein, also named BAX, which is a potential target for cancer therapies and other diseases where modulating cell death is desirable [15] [11].

Table 2: Essential Reagents for BAX Protein Functional Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Intein-CBD Tagged BAX Plasmid [11] | Expression vector for recombinant human BAX production. | Enables high-yield expression and simplified purification via affinity chromatography. |

| Chitin Resin [15] [11] | Affinity chromatography medium for protein capture. | Binds the CBD tag on the BAX-intein fusion protein. |

| Size Exclusion Column [15] [11] | High-resolution purification step. | Separates monomeric, functional BAX from aggregates and impurities. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) [15] | Reducing agent for protein purification. | Cleaves the intein tag from BAX to yield tag-free, full-length protein. |

| Liposomes (e.g., Cardiolipin) [15] | Synthetic mitochondrial membrane mimics. | Used in membrane permeabilization assays to test BAX functional activity in vitro. |

| BAX Activators (e.g., BIM peptide) [11] | Peptides that trigger BAX conformational activation. | Positive control for functional assays; mimics physiological activation. |

BAX Activation Signaling Pathway

A key application of the reagents listed above is the functional validation of BAX protein modulators. The following diagram outlines the core mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis regulated by BAX, a pathway frequently targeted in cancer drug discovery [15] [11].

The integration of Bayesian Algorithm Execution into drug discovery and biomedical research represents a paradigm shift toward more intelligent, efficient, and goal-oriented experimentation. By enabling researchers to precisely target complex subsets of candidates in vast design spaces—whether for small-molecule drugs or therapeutic proteins—BAX addresses critical bottlenecks in time and resource allocation [4] [14]. As these computational frameworks continue to evolve alongside high-throughput experimental techniques, they hold the proven potential to significantly accelerate the development of new therapies, thereby reducing the pre-clinical timeline and cost. The future of biomedical innovation lies in the continued fusion of human expertise with powerful, adaptive algorithms like BAX.

The BAX Toolkit: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Research

Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) is a sophisticated framework designed for targeted materials discovery, enabling researchers to efficiently find specific subsets of a materials design space that meet complex, user-defined goals [4]. Traditional Bayesian optimization excels at finding global optima but struggles with more nuanced experimental targets such as identifying materials with multiple specific properties or mapping particular phase boundaries [4] [16]. The BAX framework addresses this limitation by allowing scientists to express their experimental goals through straightforward filtering algorithms, which are then automatically translated into intelligent, parameter-free data acquisition strategies [17] [18]. This approach is particularly tailored for discrete search spaces involving multiple measured physical properties and short time-horizon decision making, making it exceptionally suitable for real-world materials science and drug development applications where experimental resources are limited [4].

Core BAX Strategy Architectures

Information-Based Strategy (InfoBAX)

InfoBAX is an information-theoretic approach that sequentially selects experimental queries which maximize the mutual information with respect to the output of an algorithm that defines the target subset [4] [5]. The fundamental principle involves running the target algorithm on posterior function samples to generate execution path samples, then using these cached paths to approximate the expected information gain for any potential input [5]. This strategy is particularly effective in medium-data regimes where sufficient information exists to generate meaningful posterior samples but the target subset remains uncertain [4]. InfoBAX has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in various applications, requiring up to 500 times fewer queries than the original algorithms to accurately estimate computable properties of black-box functions [5].

Posterior Mean-Based Strategy (MeanBAX)

MeanBAX represents a multi-property generalization of exploration strategies that utilize model posteriors, operating by executing the target algorithm on the posterior mean of the probabilistic model [4] [16]. This approach prioritizes regions where the model is confident about the underlying function behavior, making it particularly robust in small-data regimes where information-based methods may struggle due to high uncertainty [4]. By focusing on the posterior mean rather than sampling from the full posterior distribution, MeanBAX reduces computational complexity while maintaining strong performance during initial experimental stages when data is scarce. This characteristic makes it invaluable for early-phase materials discovery campaigns where preliminary data is limited.

Adaptive Switching Strategy (SwitchBAX)

SwitchBAX is a parameter-free, dynamic strategy that automatically transitions between InfoBAX and MeanBAX based on their complementary performance characteristics across different dataset sizes [4] [16]. This adaptive approach recognizes that MeanBAX typically outperforms in small-data regimes while InfoBAX excels with medium-sized datasets, creating a unified method that maintains optimal performance throughout the experimental lifecycle [4]. The switching mechanism operates without requiring user-defined parameters, making it particularly accessible for researchers without specialized machine learning expertise. This autonomy allows materials scientists to focus on defining their experimental goals rather than tuning algorithmic parameters, significantly streamlining the discovery workflow.

Figure 1: Logical workflow of the BAX framework, showing how user-defined goals are automatically converted into three intelligent data acquisition strategies, with SwitchBAX dynamically selecting between MeanBAX and InfoBAX based on data regime.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Analysis

Efficiency Metrics Across Application Domains

Table 1: Performance comparison of BAX strategies against traditional methods in materials discovery applications

| Application Domain | BAX Strategy | Performance Metric | Traditional Methods | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ Nanoparticle Synthesis | SwitchBAX | Queries to identify target size/shape | Bayesian Optimization | Significantly more efficient [4] |

| Magnetic Materials Characterization | InfoBAX | Measurements to map phase boundaries | Uncertainty Sampling | Significantly more efficient [4] |

| Graph Shortest Path Estimation | InfoBAX | Edge weight queries | Dijkstra's Algorithm | 500x fewer queries [5] |

| Local Optimization | InfoBAX | Function evaluations | Evolution Strategies | 200x fewer queries [5] |

Regime-Specific Performance Characteristics

Table 2: Comparative analysis of BAX strategies across different experimental conditions

| Strategy | Optimal Data Regime | Computational Overhead | Parameter Sensitivity | Primary Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InfoBAX | Medium data | Higher | Low | Information-theoretic optimality [4] |

| MeanBAX | Small data | Lower | Low | Robustness with limited data [4] |

| SwitchBAX | All regimes | Adaptive | None (parameter-free) | Automatic regime adaptation [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General BAX Implementation Workflow

Protocol 1: Standard BAX Framework Deployment

Experimental Goal Formulation: Precisely define the target subset of the design space using a filtering algorithm that would return the correct subset if the underlying material property function were known [4]. For example, specify criteria for nanoparticle size ranges, phase boundaries, or property combinations.

Probabilistic Model Initialization: Establish a Gaussian process or other probabilistic model trained to predict both values and uncertainties of measurable properties across the discrete design space [4]. The model should accommodate multi-property measurements common in materials science applications.

Sequential Data Acquisition: Iteratively select measurement points using the chosen BAX strategy (InfoBAX, MeanBAX, or SwitchBAX) by:

- Drawing posterior function samples from the probabilistic model

- Executing the target algorithm on these samples to generate execution paths

- Selecting the next measurement point that maximizes information gain about the algorithm output [5]

Model Updating and Convergence Checking: Update the probabilistic model with new measurement data and assess convergence against predefined criteria, typically involving stability in the identified target subset or budget exhaustion [4].

InfoBAX-Specific Protocol for Complex Target Identification

Protocol 2: Information-Theoretic Targeting

Execution Path Sampling: Run the target algorithm (\mathcal{A}) on (K) posterior function samples (f1, \dots, fK) to obtain a set of execution path samples (\mathcal{P}1, \dots, \mathcal{P}K) [5]. Each path (\mathcal{P}k) contains the sequence of inputs that (\mathcal{A}) would query if run on (fk).

Mutual Information Maximization: For each candidate input point (x) in the design space, approximate the expected information gain about the algorithm output (\mathcal{A}(f)) using the cached execution path samples [5].

Optimal Query Selection: Select and measure the point (x^*) that demonstrates the highest mutual information with respect to the algorithm output, effectively reducing uncertainty about the target subset most efficiently [5].

Iterative Refinement: Repeat the process until the experimental budget is exhausted or the target subset is identified with sufficient confidence.

Validation Protocol for BAX Performance Assessment

Protocol 3: Experimental Validation Methodology

Benchmark Establishment: Select appropriate baseline methods (random search, uncertainty sampling, Bayesian optimization) for comparative analysis [4].

Performance Metric Definition: Establish quantitative metrics relevant to the application, such as:

- Number of queries/measurements required to identify target subset

- Accuracy of identified subset (precision/recall relative to ground truth)

- Computational efficiency of the strategy [4]

Cross-Validation: Implement k-fold cross-validation where applicable, or holdout validation with reserved test sets to ensure statistical significance of results [4].

Regime-Specific Analysis: Evaluate performance across different dataset sizes and complexity levels to characterize the optimal operating conditions for each BAX strategy [4].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key computational and experimental reagents for BAX implementation in materials discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Model (Gaussian Process) | Predicts values and uncertainties of material properties [4] | Core component for all BAX strategies |

| Discrete Design Space | Defines possible synthesis/measurement conditions [4] | Typical in materials science applications |

| User-Defined Filter Algorithm | Encodes experimental goals and target criteria [4] | Converts complex goals to executable code |

| Posterior Sampling Algorithm | Generates function samples for execution paths [5] | Critical for InfoBAX implementation |

| Multi-Property Measurement System | Acquires experimental data for material characterization [4] | Enables multi-objective optimization |

Application Workflows in Materials Discovery

Figure 2: Application workflow of BAX strategies in materials discovery, showing how different experimental goals across various materials domains feed into the BAX process implementation, resulting in accelerated discovery outcomes.

The core BAX strategies—InfoBAX, MeanBAX, and SwitchBAX—represent a significant advancement in targeted materials discovery methodology. By transforming user-defined experimental goals into efficient data acquisition strategies, these approaches enable researchers to navigate complex design spaces with unprecedented precision and speed [4]. The parameter-free nature of SwitchBAX, combined with the complementary strengths of InfoBAX and MeanBAX across different data regimes, creates a robust framework applicable to diverse materials science challenges from nanoparticle synthesis to magnetic materials characterization [4] [17]. As materials discovery continues to confront increasingly complex design challenges, these BAX strategies provide a systematic, intelligent approach for identifying target material subsets with minimal experimental effort, ultimately accelerating the development of advanced materials for applications in energy, healthcare, and sustainable technologies [17] [18].

The discovery and development of new materials and pharmaceutical compounds are often limited by the significant time and cost associated with experimental synthesis and characterization. Traditional Bayesian optimization methods, while effective for simple optimization tasks like finding global maxima or minima, are poorly suited for the complex, multi-faceted experimental goals common in modern research [4]. These goals may include identifying materials with multiple specific properties, mapping phase boundaries, or finding numerous candidates that satisfy a complex set of criteria. Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) addresses this limitation by extending the principles of Bayesian optimization to estimate any computable property of a black-box function, defined by the output of an algorithm (\mathcal{A}) [19] [5].

The core innovation of BAX is its ability to leverage user-defined algorithms to automatically create efficient data acquisition strategies, bypassing the need for researchers to design complex, task-specific acquisition functions [4] [17]. This is achieved through information-based methods such as InfoBAX, which sequentially selects experiments that maximize mutual information with respect to the algorithm's output [19] [5]. For materials discovery, this framework has been shown to be significantly more efficient than state-of-the-art approaches, achieving comparable results with up to 500 times fewer queries to the expensive black-box function [19] [4]. This practical workflow outlines the comprehensive process from defining an experimental goal as an algorithm to implementing sequential experimentation using the BAX framework.

Theoretical Foundation of the BAX Framework

Core Mathematical Principles

Bayesian Algorithm Execution operates within a formal mathematical framework for reasoning about computable properties of black-box functions. Consider a design space (X \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}) representing (N) possible experimental conditions, each with dimensionality (d). For each design point (\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{d}), experiments yield measurements (\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^{m}) according to the relationship: [ \mathbf{y} = f{*}(\mathbf{x}) + \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \sigma^{2}\mathbf{I}) ] where (f{*}) is the true underlying function and (\epsilon) represents measurement noise [4].

The fundamental objective in BAX is to infer the output of an algorithm (\mathcal{A}) that computes some desired property of (f{*}), using only a limited budget of (T) function evaluations [5]. Algorithm (\mathcal{A}) could compute various properties: shortest paths in graphs with expensive edge queries (using Dijkstra's algorithm), local optima (using evolution strategies), top-k points, level sets, or other computable function properties [5]. The BAX framework treats the algorithm's output, denoted (\mathcal{A}(f{*})), as the target for inference.

The information-based approach to BAX (InfoBAX) selects query points that maximize the information gain about the algorithm's output: [ x{t} = \arg\max{x} I(\mathcal{A}(f); f(x) | \mathcal{D}{1:t-1}) ] where (I(\cdot;\cdot)) denotes mutual information, and (\mathcal{D}{1:t-1}) is the collection of previous queries and observations [5]. This acquisition function favors points that are most informative about the algorithm's output, regardless of the algorithm's internal querying pattern.

BAX Algorithm Variants

The BAX framework encompasses several specific implementations tailored for different experimental scenarios:

- InfoBAX: Directly maximizes mutual information with respect to the algorithm output using posterior function samples [4] [5].

- MeanBAX: A multi-property generalization of exploration strategies that uses model posteriors, often performing well in small-data regimes [4].

- SwitchBAX: A parameter-free strategy that dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX based on dataset size, combining their complementary strengths [4].

Table 1: Comparison of BAX Algorithm Variants

| Algorithm | Key Mechanism | Optimal Use Case | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| InfoBAX | Maximizes mutual information with algorithm output | Medium to large data regimes | High information efficiency; can reduce queries by up to 500x [19] |

| MeanBAX | Uses model posterior means for exploration | Small-data regimes | Robust with limited data; avoids over-reliance on uncertainty estimates [4] |

| SwitchBAX | Dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX | Entire data range (small to large) | Parameter-free; adaptive to changing data conditions [4] |

Practical Workflow Implementation

Stage 1: Defining the Experimental Goal as an Algorithm

The initial and most crucial step in the BAX workflow is formulating the experimental goal as a straightforward filtering or computation algorithm. This algorithm should return the desired subset of the design space if the underlying function (f_{*}) were fully known [4].

Protocol 3.1.1: Algorithm Definition Methodology

Precisely Specify the Target Subset: Clearly define the criteria that design points must meet to be included in the target subset ({{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}_{* }). This may involve thresholds on one or multiple properties, specific topological features, or other computable conditions.

- Example: "Find all synthesis conditions that produce nanoparticles with size between 5-10 nm AND bandgap > 3.2 eV."