Taming Polymorphs: How Generative AI Models Are Revolutionizing Material Design and Drug Development

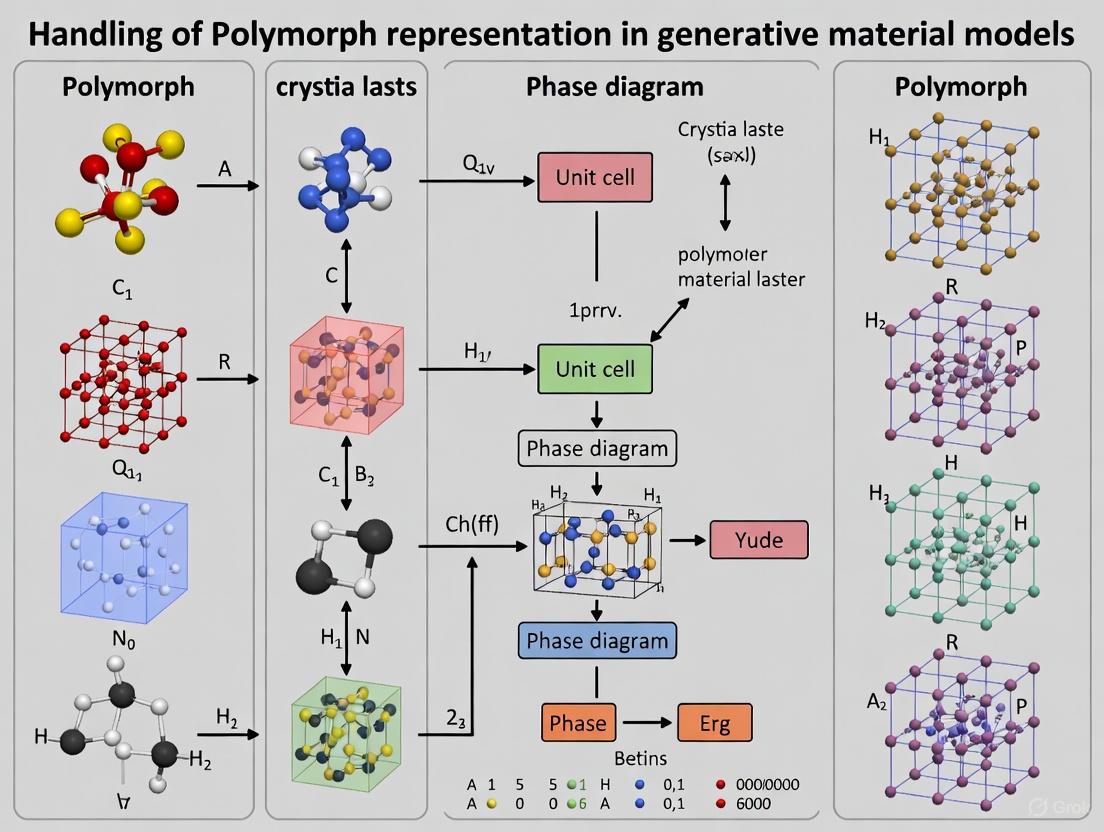

This article explores the critical challenge of handling polymorph representation within generative AI models for material science.

Taming Polymorphs: How Generative AI Models Are Revolutionizing Material Design and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the critical challenge of handling polymorph representation within generative AI models for material science. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of how advanced computational methods are being used to predict, control, and optimize polymorphic outcomes. We cover the foundational principles of polymorphism and its impact on material properties, detail cutting-edge AI methodologies from conditional diffusion models to reinforcement learning, address key troubleshooting and optimization challenges like 'disappearing polymorphs,' and validate these approaches through large-scale studies and real-world applications in pharmaceuticals and quantum materials. The article synthesizes these insights to highlight a transformative shift towards autonomous, predictive material design.

The Polymorph Problem: Foundations, Risks, and the Need for AI in Material Design

Polymorphism is a fundamental phenomenon in crystallography where a single chemical substance can exist in more than one crystal form [1] [2]. These different crystalline phases, known as polymorphs, possess identical chemical compositions but differ in how their molecules or atoms are arranged in the solid state [3] [4]. This variation in molecular packing or conformation can lead to significant differences in physical properties, making polymorphism a critical consideration across scientific and industrial fields, from pharmaceuticals to materials science [4] [2]. Within emerging research on generative material models, accurately representing and predicting polymorphic behavior presents both a substantial challenge and opportunity for advancing materials design [5] [6] [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental definition of a polymorph?

A polymorph is a solid crystalline phase of a given compound resulting from the possibility of at least two different arrangements of the molecules of that compound in the solid state [1] [2]. The key distinction is that polymorphs have identical chemical compositions but different crystal structures, which distinguishes them from solvates or hydrates that incorporate solvent molecules into their crystal lattice [3] [2].

Q2: How do polymorphs differ from allotropes?

Polymorphs refer to different crystal forms of the same chemical compound, while allotropes refer to different structural forms of the same element [4]. For example, diamond and graphite are allotropes of carbon, not polymorphs of each other, as they feature fundamentally different carbon bonding (sp³ vs sp² hybridization) [1]. However, diamond and lonsdaleite, which both feature sp³ hybridized bonding but different crystal structures, are polymorphs [1].

Q3: Why is polymorphism critically important in pharmaceutical development?

Polymorphism is crucial in pharmaceuticals because different polymorphs of the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) can exhibit dramatically different properties including solubility, dissolution rate, stability, and bioavailability [8] [3] [4]. These variations can directly impact drug efficacy, safety, and manufacturability. Regulatory agencies require thorough polymorph screening and control, as unexpected polymorphic transformations can compromise product quality [3].

Q4: What is the difference between enantiotropic and monotropic polymorphism?

Enantiotropic polymorphs are reversibly related through a phase transition at a specific temperature and pressure, meaning each form has a defined stability range under different conditions [2]. Monotropic polymorphs, in contrast, have one form that is thermodynamically stable across the entire temperature range, while the other(s) are metastable [2]. This relationship determines whether polymorphic transitions are reversible and under what conditions they occur.

Q5: Can amorphous forms be considered polymorphs?

Amorphous solids, which lack long-range molecular order, are not technically considered polymorphs, as polymorphism specifically refers to different crystalline forms [2]. However, amorphous materials can exist in different structural states sometimes called "polyamorphs," though this classification remains subject to discussion within the scientific community [2].

Experimental Detection and Characterization Methods

Identifying and characterizing polymorphs requires specialized analytical techniques that can detect differences in crystal structure and physical properties. The table below summarizes the principal methods used.

Table 1: Experimental Techniques for Polymorph Detection and Characterization

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Measurable Parameters | Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) [1] | Solid-state structure analysis | Crystal lattice parameters, diffraction patterns | Unique fingerprint for each polymorph; determines crystal structure and unit cell dimensions |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [1] [3] | Thermal behavior analysis | Melting point, enthalpy of transitions, polymorphic transition temperatures | Reveals thermal stability, enantiotropic or monotropic relationships, and transition energies |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) [3] | Solvent/water content analysis | Weight loss upon heating | Distinguishes between true polymorphs and solvates/hydrates |

| Hot Stage Microscopy [1] | Visual observation of transitions | Crystal morphology, transition temperatures | Direct visualization of polymorphic transformations and crystal habit differences |

| Infrared (IR) & Raman Spectroscopy [1] [2] | Molecular vibration analysis | Vibrational frequencies, hydrogen bonding patterns | Sensitive to changes in molecular conformation and intermolecular interactions |

| Solid-State NMR [2] | Local molecular environment | Chemical shifts, relaxation times | Probes molecular conformation and packing, including disordered systems |

| Terahertz Spectroscopy [1] | Low-frequency vibrations | Intermolecular vibrational modes | Sensitive to long-range crystal packing arrangements |

Troubleshooting Common Polymorph Handling Issues

Problem: Unexpected Polymorphic Transformation During Milling

Issue Description: Milling, a common pharmaceutical processing step to reduce particle size, can induce unintended polymorphic transformations or amorphization [8].

Underlying Mechanism: The transformation mechanism typically involves a two-step process: (1) mechanical energy from milling causes local amorphization of the starting polymorph, followed by (2) recrystallization into a different polymorphic form [8]. The relative position of the milling temperature versus the material's glass transition temperature (Tg) plays a critical role—milling below Tg tends to promote amorphization, while milling above Tg often leads to polymorphic transformation [8].

Resolution Strategies:

- Control milling temperature to remain below or above Tg depending on desired outcome

- Limit milling duration and energy input to minimize transformation risk

- Conduct preliminary studies to establish safe milling parameters for your specific compound

- Monitor transformations in real-time using in-line analytical techniques

Problem: Difficulty Obtaining Desired Polymorph During Crystallization

Issue Description: The target polymorph fails to crystallize, or multiple forms appear inconsistently.

Root Causes: Polymorphic outcome depends on subtle variations in crystallization conditions including solvent choice, supersaturation level, temperature profile, cooling rate, and presence of impurities or seeds [3] [9].

Resolution Strategies:

- Systematically explore different solvent systems and anti-solvents

- Control cooling rate—slow cooling generally promotes stable forms while rapid cooling may favor metastable forms [9]

- Utilize seeding with pre-formed crystals of the desired polymorph

- Employ various crystallization techniques (cooling, anti-solvent, evaporation)

- Implement process analytical technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring

Problem: Polymorphic Transformation During Drug Product Manufacturing

Issue Description: The API transforms to a different polymorph during unit operations such as wet granulation, compaction, or drying.

Root Causes: Stress-induced transformations can occur due to pressure (e.g., during tablet compression), exposure to moisture or solvents, or temperature fluctuations during processing [3] [10].

Resolution Strategies:

- Modify formulation excipients to create a protective matrix

- Optimize process parameters (e.g., compression force, drying temperature)

- Implement intermediate process controls to detect early transformation

- Consider using the most stable polymorph if bioavailability permits

Computational Approaches in Generative Material Models

Emerging computational methods are revolutionizing polymorph prediction and representation in materials research. The table below summarizes key computational tools and frameworks.

Table 2: Computational Approaches for Polymorph Prediction and Representation

| Method/Model | Primary Approach | Application in Polymorphism | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) [1] | Global optimization of crystal energy landscape | Predicts possible polymorphic structures from molecular structure | Identifies thermodynamically feasible polymorphs before experimental discovery |

| Matra-Genoa [5] | Autoregressive transformer with Wyckoff representations | Generates stable crystal structures including polymorphs | Uses hybrid discrete-continuous space; conditions on stability relative to convex hull |

| Chemeleon [6] | Denoising diffusion with text guidance | Generates compositions and structures from text descriptions | Incorporates cross-modal learning aligning text with structural data |

| Data-Driven Topological Analysis [7] | Topological data analysis of crystal structures | Identifies polymorphic patterns across materials space | Uses polyhedral connectivity graphs to cluster polymorphs by topological similarity |

| Crystal CLIP [6] | Contrastive learning for text-structure alignment | Creates representations linking textual and structural data | Aligns text embeddings with crystal graph embeddings in shared latent space |

Polymorph Discovery Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines key materials and computational resources essential for polymorph research in the context of generative models.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Polymorph Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Characterization Instruments [1] [3] | X-ray diffractometers, DSC, TGA, hot stage microscopes, Raman spectrometers | Experimental identification and quantification of polymorphic forms |

| Computational Databases [6] [7] | Materials Project, Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Source of known structures and properties for training generative models |

| Generative Model Frameworks [5] [6] | Matra-Genoa, Chemeleon, Crystal CLIP | Prediction of novel polymorphic structures and their properties |

| Representation Methods [5] [7] | Wyckoff position representations, polyhedral connectivity graphs | Structured representation of crystal geometry for machine learning |

| Stability Assessment Tools [5] [6] | Density functional theory (DFT), convex hull analysis | Evaluation of thermodynamic stability of predicted polymorphs |

Advanced Transformation Mechanisms

Understanding the microscopic mechanisms of polymorphic transformations is essential for controlling solid form behavior.

Polymorph Transformation Pathways

Recent research has elucidated detailed mechanisms for stress-induced polymorphic transformations. During milling, the transformation kinetics appear to follow a two-step process where the initial polymorph first undergoes local amorphization due to mechanical energy input, followed by stochastic nucleation and growth of the final polymorphic form [8]. The detection of intermediate amorphous material during this process supports this mechanism, which appears independent of whether the polymorphs have an enantiotropic or monotropic relationship [8].

The comprehensive understanding of polymorphism requires integrating experimental characterization with computational prediction, particularly as generative material models advance in their ability to represent and predict polymorphic behavior. For researchers working with generative material models, accurately capturing the complex energy landscapes of polymorphic systems remains a significant challenge, but one that new transformer architectures, diffusion models, and topological analysis approaches are increasingly addressing [5] [6] [7]. Systematic troubleshooting approaches combined with these emerging computational tools provide a robust framework for managing polymorph-related challenges throughout materials development and manufacturing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is a "disappearing polymorph" and why is it a problem? A disappearing polymorph is a crystal form that has been successfully prepared in the past but becomes difficult or impossible to reproduce using the same procedure that initially worked. Subsequent attempts typically yield a different, often more stable, crystal form. This occurs because the new, more stable form acts as a seed, and its mere presence—even in microscopic, airborne quantities—can catalyze the transformation of the metastable form into the stable one. This presents a severe problem for drug development and manufacturing, as the different crystal form can have altered physicochemical properties, such as solubility and bioavailability, which directly impact the drug's safety and efficacy [11] [12].

FAQ 2: What are the real-world consequences of a disappearing polymorph? The consequences are significant and can include:

- Product Recalls: If a new, less effective polymorph emerges and contaminates production, batches may fail specifications, leading to recalls. A recall of pantoprazole products was associated with a 69% higher rate of potential drug-drug interactions after patients were switched to alternatives [13].

- Treatment Disruption: The recall of the HIV drug Ritonavir (Form II) due to a new, less soluble polymorph left thousands of patients without effective medication and cost the manufacturer over $250 million [12].

- Patent Litigation: The emergence of a new polymorph can lead to complex legal battles, as seen with paroxetine, where the appearance of a hemihydrate form affected the production of the original anhydrate form [11] [12].

FAQ 3: Can a disappeared polymorph ever be recovered? Yes, according to experts, a disappeared polymorph has not been relegated to a "crystal form cemetery." It is generally a metastable form, meaning it exists at a higher energy minimum than the most stable form but does not necessarily spontaneously convert. The recovery of a disappeared polymorph is possible but may require considerable effort and inventive chemistry to find the precise experimental conditions that favor its formation over the now-dominant stable form [11].

FAQ 4: How can generative AI models help mitigate polymorph-related risks? Generative models, such as Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoders (CDVAE), can learn the underlying probability distribution of stable crystal structures from existing materials databases. These models can generate candidate crystal structures with good stability properties, significantly expanding the explored space of potential polymorphs. By proactively identifying a more complete set of possible solid forms during the early development phase, researchers can assess their relative stabilities and design strategies to avoid problematic phase transitions later [14] [15]. This represents a shift from reactive problem-solving to proactive inverse design.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating a Sudden Change in Crystallization Outcome

Problem: A previously reproducible crystallization process now consistently yields a different solid form than expected.

Investigation Protocol:

- Confirm the Identity: Use techniques like Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) and Raman spectroscopy to confirm that the new solid is a different polymorph and not a solvate or hydrate.

- Assess Relative Stability: Perform competitive slurry experiments by suspending both the old and new forms in a solvent to determine which is thermodynamically more stable.

- Check for Cross-Contamination: Meticulously audit the laboratory and manufacturing environment. The new, more stable polymorph may have seeded the environment. This is critical, as an invisible particle weighing 10⁻⁶ grams can contain up to 10¹⁰ potential seed nuclei [11].

- Review Process Parameters: Scrutinize any subtle changes in raw material sources, equipment, or environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity) that could have shifted the kinetic balance.

Guide 2: Proactive Polymorph Screening Using Generative Models

Problem: How to proactively identify and characterize a comprehensive solid-form landscape to de-risk development.

Experimental Workflow: The following diagram outlines a hybrid computational-experimental workflow for robust polymorph screening.

Methodology Details:

- Computational Generation:

- Lattice Decoration Protocol (LDP): Systematically substitutes atoms in known seed structures with chemically similar elements. This generates new crystals that are structurally similar to the seeds but with different compositions [14].

- Generative AI (e.g., CDVAE): A Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoder is trained on a database of stable crystal structures (e.g., with energy above the convex hull, ΔHₕᵤₗₗ < 0.3 eV/atom). It learns the distribution of stable materials and can generate novel, chemically diverse candidate structures from noise by leveraging a denoising diffusion model [14] [15].

- Stability Filtering: The generated candidate structures are relaxed and their formation energies are calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT). Candidates with high formation energies (e.g., ΔHₕᵤₗₗ > 0.3 eV/atom) are filtered out as they are less likely to be synthesizable [14].

- Experimental Validation: The most promising predicted structures are targeted for experimental crystallization to confirm their existence and properties.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of a Proton Pump Inhibitor (Pantoprazole) Recall on Patient Safety

| Metric | Before Recall (12 Months) | After Recall (6 Months) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Potential Drug-Drug Interactions (pDDIs) | 1,138 | 688 | - |

| Median Monthly pDDIs | 102.5 | 115.5 | Increase |

| Rate Ratio of pDDIs (After vs. Before) | 1 (Reference) | 1.69 | 69% Increase |

| Most Common Interacting Drugs | Warfarin (49.1%), Clopidogrel (15.4%) | Warfarin, Clopidogrel | - |

Source: Retrospective study using electronic health records [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Generative Approaches for Crystal Structure Prediction

| Method | Principle | Key Advantage | Application in 2D Materials Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice Decoration (LDP) | Systematic element substitution in known structures based on chemical similarity. | Simple, explainable, guarantees structures are related to known stable seeds. | Generated 14,192 unique crystals from 2,615 seeds; 8,599 had ΔHₕᵤₗₗ < 0.3 eV/atom [14]. |

| Crystal Diffusion VAE (CDVAE) | Deep generative model that denoises random atom placements into stable crystals. | High chemical and structural diversity; capable of discovering truly novel structures. | Generated 5,003 unique crystals after DFT relaxation; many had low formation energies mirroring the training set [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Polymorph and Materials Informatics Research

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB) | A open database providing atomic structures and computed properties for 2D materials, serving as a key training set for generative models [14]. |

| Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoder (CDVAE) | A generative model that combines a variational autoencoder with a diffusion process to generate novel, stable crystal structures [14] [15]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code | First-principles computational method used to relax generated crystal structures and calculate key stability metrics like the energy above the convex hull (ΔHₕᵤₗₗ) [14]. |

| Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Analytical technique used to identify and differentiate between different polymorphs based on their unique diffraction patterns [11]. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | A widely used tool to differentiate between polymorphs, as it is sensitive to changes in crystal structure and molecular vibrations [12]. |

| Formal Grammars (e.g., PolyGrammar) | A symbolic, rule-based system for representing and generating chemically valid polymers, offering explainability and validity guarantees [16]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Why do different batches of the same API have different solubility and dissolution rates?

Answer: This is a classic symptom of variations in the API's solid-state properties, most notably its polymorphic form or particle size distribution, even when its chemical purity is identical.

- Root Cause: APIs can exist in multiple solid forms, or polymorphs. Each polymorph has a distinct crystal lattice energy, which directly impacts its solubility and physical stability. Changes during synthesis, crystallization, or storage can alter the dominant polymorph in a batch.

- Case Evidence: A study on the anticancer drug Olaparib found that two batches with 99.9% chemical purity showed different solubility. Batch 1, a mixture of Form A and Form L with lower crystallinity, had a solubility of 0.1239 mg/mL. Batch 2, composed purely of the more stable Form L, had a significantly lower solubility of 0.0609 mg/mL [17].

- Solution: Implement a robust polymorph screening during pre-formulation. Techniques like X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) are essential for identifying and characterizing these solid forms to ensure batch-to-batch consistency [17] [18].

Table 1: Impact of Polymorphic Composition on API Properties: Olaparib Case Study

| Batch | Polymorphic Composition | Crystallinity | Equilibrium Solubility (37°C) | Intrinsic Dissolution Rate (IDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch 1 | Mixture of Form A (major) and Form L (minor) | Lower | 0.1239 mg/mL | 26.74 mg/cm²·min⁻¹ |

| Batch 2 | Pure Form L | Higher | 0.0609 mg/mL | 13.13 mg/cm²·min⁻¹ |

What can be done if an API has low solubility that limits its bioavailability?

Answer: Low solubility is a major hurdle for over 90% of new chemical entities. Several formulation strategies can be employed to enhance solubility and dissolution rate [19] [20].

- Root Cause: A high crystal lattice energy (as in stable crystalline forms) and high hydrophobicity lead to low aqueous solubility, which is the primary rate-limiting step for absorption for Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Class II and IV drugs [19] [18].

- Solutions: The strategy chosen depends on the API's properties and the development stage.

- Particle Size Reduction: Milling the API to a finer particle size increases the surface area available for dissolution, thereby improving the dissolution rate [19] [18].

- Salt Formation: For ionizable compounds, forming a salt can significantly increase dissolution rate and create supersaturation, leading to higher absorption [19] [18].

- Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs): Converting the crystalline API into a high-energy, amorphous form stabilized by a polymer matrix can dramatically enhance both solubility and dissolution rate. Technologies like Hot Melt Extrusion (HME) are highly effective for creating ASDs [20].

- Use of Solubilizing Agents: Excipients like Soluplus and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin can enhance API solubility. In the Olaparib case, these agents increased solubility up to 26-fold for the less soluble batch [17].

Table 2: Formulation Strategies to Overcome Low Solubility

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size Reduction | Increases surface area for dissolution | Requires specialized milling; careful control of particle size distribution is needed [20] [18]. |

| Salt/Co-crystal Formation | Alters solid-form energy to improve dissolution rate and create supersaturation | Applicable to ionizable molecules (salts) or through non-ionic interactions (co-crystals) [19] [18]. |

| Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs) | Creates a high-energy, amorphous form with faster dissolution and higher solubility | Requires a polymer to stabilize the amorphous form against recrystallization; processes include Hot Melt Extrusion and Spray Drying [20]. |

| Lipid-Based Systems | Enhances solubility and absorption via lipid solubilization | Suitable for highly lipophilic compounds [20]. |

How can we prevent unexpected changes in the physical form of an API during storage or manufacturing?

Answer: Physical instability, such as polymorphic conversion or crystallization of amorphous systems, is driven by the API's tendency to revert to its most thermodynamically stable form. Prevention requires understanding and controlling this tendency.

- Root Cause: Metastable forms (like amorphous or less stable polymorphs) have higher free energy and will eventually transform to more stable forms, especially under stress conditions like heat or humidity [17] [20].

- Solution:

- Thorough Solid-State Screening: Conduct comprehensive polymorph and salt screens early in development to identify the most stable form for development [18].

- Compatibility and Stability Studies: Perform pre-formulation studies to understand the API's physicochemical properties (e.g., melting point, glass transition temperature, hygroscopicity, and chemical degradation pathways) [21] [20].

- Stabilization via Formulation: For amorphous systems, the choice of polymer in an ASD is critical. A thorough thermodynamic assessment, including miscibility studies and phase diagram construction, is necessary to ensure long-term physical stability and prevent recrystallization [20].

What are the critical experiments to run when characterizing a new API?

Answer: A rigorous physicochemical evaluation is the foundation of successful API development. The following experiments are essential [20]:

- Thermal Analysis:

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Determines melting temperature (Tm), glass transition temperature (Tg), and detects polymorphs.

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Assesses thermal degradation temperature (Tdeg) and detects solvates or hydrates by weight loss.

- Solid-State Structure:

- X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD): The primary technique for identifying crystalline phases and polymorphic forms.

- Morphology and Particle Analysis:

- Hot Stage Microscopy (HSM): Visually observes thermal events and crystal habit.

- Particle Size Analysis: Determines particle size distribution.

- Solubility and Dissolution Profiling:

- pH-Solubility Profile: Determines solubility across the physiological pH range.

- Intrinsic Dissolution Rate (IDR): Measures the dissolution rate of a standardized surface area of the API.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for API Solubility and Stability Studies

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Polymorphic Screening Kits | Pre-packaged sets of various solvents and conditions to rapidly crystallize and identify potential polymorphs, salts, and co-crystals [18]. |

| Polymer Carriers (e.g., PVP-VA, HPMCAS) | Essential for forming Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs). They inhibit crystallization and maintain the API in a high-energy, soluble amorphous state by providing molecular-level dispersion and inhibiting crystal growth [20]. |

| Biorelevant Media (e.g., FaSSIF, FeSSIF) | Simulate the composition and surface activity of human intestinal fluids. They provide a more physiologically relevant assessment of dissolution and solubility compared to simple aqueous buffers [19]. |

| Solubilizing Agents (e.g., Cyclodextrins, Soluplus) | Enhance apparent solubility by forming soluble inclusion complexes (cyclodextrins) or micelles (Soluplus) around the hydrophobic API molecules [17]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | A critical tool for thermal analysis. It measures temperatures and heat flows associated with phase transitions (melting, glass transition) in the API, which are key indicators of polymorphism and stability [17] [20]. |

| X-Ray Powder Diffractometer (XRPD) | The definitive tool for solid-state characterization. It produces a fingerprint pattern unique to each crystalline form, allowing for the identification and quantification of polymorphs in an API sample [17] [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the core limitation of traditional HTS in exploring polymorphs? Traditional HTS is fundamentally a screening process, not a generative one. It is limited to experimentally testing a pre-defined, finite library of compounds. This makes it inefficient for exploring the vast configuration space of potential polymorphic structures, as it cannot propose novel, untested crystal forms that may have superior properties [22].

FAQ 2: How do generative models represent crystal structures differently? Generative models for materials use advanced representations to encode crystal structure. Unlike simple compositional formulas, these models often use graph-based representations or symmetry-aware parameterizations that capture atomic coordinates, lattice parameters, and atom types. For example, a crystal unit cell can be represented as ( \mathcal{M}=({\bf{A}},{\bf{F}},{\bf{L}}) ), where A represents atom types, F represents fractional coordinates, and L represents the lattice matrix, providing a complete structural description [23].

FAQ 3: Can AI models incorporate symmetry constraints relevant to polymorphs? Yes. Advanced generative models explicitly incorporate the periodic-E(3) symmetries of crystals—including permutation, rotation, and periodic translation invariance. This is achieved through the use of equivariant graph neural networks, which ensure that the generated crystal structures respect fundamental physical symmetries, a critical factor for accurate polymorph representation and generation [23].

FAQ 4: What is a key advantage of flow-based generative models over other AI methods? Flow-based models, such as CrystalFlow, utilize Continuous Normalizing Flows and Conditional Flow Matching to transform a simple prior distribution into a complex distribution of crystal structures. A significant advantage is their computational efficiency, being approximately an order of magnitude more efficient in terms of integration steps compared to diffusion-based models, enabling faster exploration of the material space [23].

FAQ 5: How can we validate the quality of AI-generated crystal structures? The quality of generated crystal structures is typically validated through detailed Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. These first-principles computational methods assess the thermodynamic stability and other properties of the proposed structures, providing a rigorous check on the model's outputs [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Structural Validity or Stability in Generated Crystals

- Problem: The generative model produces crystal structures that are physically invalid or energetically unstable.

- Solution:

- Incorporate Symmetry Constraints: Implement an equivariant neural network architecture that inherently respects the rotational, translational, and permutation symmetries of crystals [23].

- Refine Data Representation: Ensure the lattice parameters are represented using a rotation-invariant vector, for instance, via polar decomposition, to decouple rotational and structural information [23].

- Leverage Hybrid Models: Utilize unified frameworks that integrate structure generation with property prediction, which has been shown to enhance the fidelity of generated structures [23].

Issue 2: Inability to Generate Structures for Specific Properties or Conditions

- Problem: The model cannot perform conditional generation, such as predicting stable structures under specific pressure or with a target material property.

- Solution:

- Adopt a Conditional Framework: Implement a model that learns the conditional probability distribution ( p(x|y) ), where ( x ) represents structural parameters and ( y ) represents conditioning variables like chemical composition (A) and external pressure (P) [23].

- Utilize Labeled Data: Train the model on appropriately labeled datasets where material properties or synthesis conditions are well-documented [23].

Issue 3: High Computational Cost during Model Inference

- Problem: Sampling new structures from the generative model is slow and computationally expensive.

- Solution:

- Choose Efficient Architectures: Employ flow-based models like CrystalFlow, which are based on Continuous Normalizing Flows and are significantly more efficient than diffusion-based models, requiring fewer integration steps for sampling [23].

- Optimize ODE Solvers: Use numerical ordinary differential equation (ODE) solvers with adjustable integration steps to balance the trade-off between computational efficiency and sample quality [23].

Issue 4: Model Fails to Generalize to Unseen Compositions or Structures

- Problem: The generative model performs poorly on chemical compositions or structural types not well-represented in the training data.

- Solution:

- Expand and Diversify Training Data: Leverage large and comprehensive materials databases to train the model [22].

- Employ Physics-Informed Architectures: Integrate physical principles and constraints into the model's architecture to improve its generalizability beyond the immediate training distribution [24].

Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Material Discovery Approaches

| Feature | Traditional HTS | AI-Driven Generative Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Screening pre-defined compound libraries [25] | Inverse design from desired properties [22] |

| Exploration Capability | Limited to existing library | Capable of proposing novel, untested structures [22] |

| Data Representation | Often simplistic (e.g., composition) | Complex, symmetry-aware (e.g., crystal graphs, lattices) [23] [22] |

| Handling Polymorphs | Inefficient; requires synthesizing each variant | Efficiently models the configuration space of crystalline materials [23] |

| Primary Limitation | "Data-hungry"; biased by screening library [22] | Challenges with data scarcity and decoding complex representations [22] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Material Discovery

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Equivariant Graph Neural Network | A symmetry-preserving network architecture that serves as the core engine for generating physically plausible crystal structures by respecting E(3) symmetries [23]. |

| Continuous Normalizing Flows (CNFs) | The mathematical framework that enables efficient mapping from a simple prior distribution to the complex data distribution of real crystal structures [23]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | The computational workhorse used for the validation of generated crystal structures, calculating their stability and electronic properties [23]. |

| Crystal Structure Databases (e.g., MP-20) | Curated datasets of known materials that serve as the essential training data for teaching generative models the rules of stable crystal formation [23]. |

| Conditional Variables (e.g., Pressure, Composition) | Input parameters that guide the generative model to produce structures with specific targeted characteristics or stable under specific conditions [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Generative Model for Polymorphs

Model Training:

- Train a flow-based generative model (e.g., CrystalFlow) on a benchmark dataset of crystalline structures (e.g., MP-20) using a Conditional Flow Matching objective. The model should be designed to generate the lattice parameters, fractional coordinates, and atom types simultaneously [23].

Conditional Generation:

- For a target chemical composition and a specific external condition (e.g., pressure), sample novel crystal structures from the model. This involves solving an ODE where the initial state is a random sample from a Gaussian prior distribution [23].

Structural Validation:

- Assess the generated structures using standard crystallographic metrics. Calculate the success rate of generating structures that are both valid (correct symmetry, reasonable interatomic distances) and novel (not present in the training database) [23].

Energetic Validation via DFT:

- Perform full geometry relaxation and energy calculations on the top candidate structures using DFT. The key metric is the formation energy, which confirms the thermodynamic stability of the generated polymorphs. Compare the DFT-calculated properties (e.g., band gap, bulk modulus) with the model's predictions [23].

Workflow Visualization

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our generative model for novel crystal structures produces outputs with low diversity (e.g., mode collapse). How can we address this?

A: Mode collapse, where a generator produces a limited variety of outputs, is a common training instability in generative models like GANs [26].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Analyze the Loss Function: Experiment with different loss functions. A combination of adversarial loss and feature matching loss has been shown to enhance diversity in image generation models [26].

- Implement Batch Normalization: Add batch normalization layers to the generator and discriminator networks to stabilize the training process and improve convergence [26].

- Evaluate Output Diversity: Use domain-specific metrics to quantitatively assess the problem. For material structures, this could involve calculating the radial distribution function diversity or using the Inception Score for image-based structural data [26].

- Expected Outcome: After modifications, the model should generate a broader range of high-quality outputs [26].

Q2: The predicted crystal structures from our generative model are physically invalid or have poor energy landscapes. What is the root cause and solution?

A: This often points to issues with the training data quality or model overfitting.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Interrogate Data Quality:

- Check for Noise and Bias: Analyze the training data for errors, inconsistencies, or a non-representative distribution of polymorphs. Biased data leads to biased results [26].

- Clean and Balance the Dataset: Use statistical techniques to handle outliers. For imbalanced polymorph data, employ oversampling, undersampling, or synthetic data generation to achieve balance [26].

- Mitigate Model Overfitting:

- Apply Regularization: Implement techniques like L1/L2 regularization or dropout to prevent the model from memorizing the training data instead of learning general patterns [26].

- Tune Hyperparameters: Systematically adjust hyperparameters like learning rate and dropout rate using grid search, random search, or Bayesian optimization [26].

- Utilize Cross-Validation: Employ k-fold cross-validation to assess model performance on different data subsets and ensure robustness [26].

- Interrogate Data Quality:

Q3: Our generative model performs well in training but fails to generalize to unseen molecular compounds. How can we improve its predictive design capability?

A: This underfitting or poor generalization suggests the model is too simplistic or lacks relevant learned features.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Start with a pre-trained model on a large, related dataset (e.g., a general molecular structure database) and fine-tune it on your specific target dataset. This is especially beneficial when experimental polymorph data is limited [26].

- Employ Ensemble Methods: Combine predictions from multiple models to reduce variance and improve overall performance. Techniques include model averaging or stacking with a meta-model [26].

- Increase Model Complexity (Judiciously): Modify the model architecture to better capture the underlying complexities of crystal energy landscapes, ensuring a balance is struck to avoid overfitting [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the minimum data requirements for training a robust generative model for polymorph prediction? A: There is no fixed minimum, but data quality and quantity are paramount [26]. The dataset must be sufficient, clean, and representative of real-world polymorphic diversity. Techniques like data augmentation (e.g., rotational symmetries for crystals) can artificially expand the dataset [26].

Q: Which evaluation metrics are most appropriate for assessing generated crystal structures? A: Use a combination of metrics [26]:

- Domain-Specific Metrics: Compare generated structures with known crystals using metrics like Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions or similarity in unit cell parameters.

- Energy-based Validation: Use density functional theory (DFT) calculations to assess the thermodynamic stability of generated structures.

- Human Expert Evaluation: Engage crystallography experts to judge the quality, novelty, and plausibility of the generated polymorphs [26].

Q: We are encountering high latency when running our trained model for inference. How can we optimize deployment? A: To reduce inference times and improve scalability [26]:

- Apply Model Optimization: Use techniques like quantization (reducing numerical precision) and pruning (removing redundant weights) to decrease model size and speed up inference [26].

- Utilize Load Balancing: Distribute inference workloads evenly across multiple servers to handle increased demand [26].

Experimental Protocols for Polymorph Screening

A comprehensive experimental polymorph screen is critical for generating high-quality data to train and validate generative AI models. The objective is to recrystallize the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) under a wide range of conditions to sample thermodynamic and kinetic solid products [27].

Detailed Methodology: High-Throughput Solution Crystallization

- Sample Preparation: Dispense solid API as a concentrated solution into individual wells of a multi-well plate. Evaporate the solvent to leave a uniform solid starting material [27].

- Solvent Dispensing: Dispense a diverse library of solvents or solvent mixtures into the wells. The library should be selected using chemoinformatics to cover a wide range of physicochemical properties (e.g., polarity, hydrogen bonding capacity) [27].

- Dissolution and Crystallization:

- Warm and agitate the plates to aid dissolution.

- Induce crystallization through controlled cooling or solvent evaporation to achieve supersaturation [27].

- Analysis and Characterization: Once crystallization occurs, analyze the solid form in each well. For high-throughput screens, use fast, non-destructive techniques that require no sample preparation [27]:

- Raman Spectroscopy: Quickly fingerprints different polymorphs based on their characteristic Raman spectrum. Ideal for small samples and can be used with wet samples [27].

- X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) with 2D Area Detectors: Provides a definitive fingerprint for polycrystalline samples. Can collect data from very small crystallites in about one minute [27].

The workflow for integrating experimental screening with AI-driven prediction is outlined below.

Analytical Techniques for Polymorph Characterization

The following table summarizes key techniques used to identify and characterize solid forms discovered during screening.

| Method | Key Function in Polymorph Analysis |

|---|---|

| X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) | Fingerprint polycrystalline samples; identify novel polymorphs; determine unit cell parameters; analyze solid-state transformations [27]. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Rapidly fingerprint polymorphs via characteristic spectrum; ideal for high-throughput screening; can track changes in situ [27]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measure transition temperatures (melting point, desolvation), heat of fusion, and glass transition temperature (Tg) [27]. |

| Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Quantify weight loss due to desolvation; determine solvate stoichiometry [27]. |

| Dynamic Vapour Sorption (DVS) | Measure moisture uptake as a function of relative humidity; identify hydrate formation and dehydration events [27]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Polymorph Research |

|---|---|

| Diverse Solvent Library | A curated set of solvents with varied properties (polarity, hydrogen bonding) to explore a wide crystallization space and maximize the discovery of polymorphs and solvates [27]. |

| Polymer Heteronuclei | Surfaces used to induce heterogeneous nucleation of specific polymorphs that may not form easily from solution, thereby expanding the diversity of forms obtained [27]. |

| Co-crystal Formers | Pharmaceutically acceptable molecules that co-crystallize with the API to form multi-component solids, offering a strategy to manipulate solubility and stability [28]. |

AI in Action: Methodologies for Polymorph Prediction and Generation

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when integrating diffusion models with reinforcement learning, particularly in the context of handling polymorphic representations for generative material design.

FAQ: General Framework and Theory

Q1: What core advantage do Diffusion Models (DMs) offer over traditional policies in Reinforcement Learning (RL)?

Traditional RL policies often rely on unimodal distributions (e.g., Gaussian), which can struggle to represent complex, multi-modal action spaces. DMs excel at modeling multi-modal distributions, allowing them to capture diverse, equally valid solutions or strategies. This is crucial for tasks where multiple successful action sequences exist, greatly improving a model's exploration capabilities and final performance [29] [30].

Q2: My diffusion RL model suffers from slow inference times. What are the primary strategies for acceleration?

Slow sampling is a known challenge due to the iterative denoising process. Researchers can consider the following strategies:

- Deterministic Samplers: Methods like Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIM) reinterpret the stochastic sampling process as a deterministic one, drastically reducing the number of required steps [31] [30].

- Consistency Models (CMs): These models are trained to map any point on the noise trajectory directly to the origin, enabling fast one- or few-step generation [32] [33].

- Sampling Schedule Optimization: Techniques like "Jump Your Steps" provide a principled way to reallocate sampling steps in Discrete Diffusion Models, achieving the same quality with fewer steps [32].

- Latent Space Diffusion: Models like Stable Diffusion perform the diffusion process in a lower-dimensional latent space, significantly reducing computational load [31].

Q3: In offline meta-RL, how can I improve my model's generalization to unseen tasks?

The MetaDiffuser framework addresses this by treating generalization as a conditional trajectory generation task. It learns a context encoder that captures task-relevant information from a warm-start dataset. This context then guides a diffusion model to generate task-specific trajectories. A dual-guide system during sampling ensures these trajectories are both high-rewarding and dynamically feasible [34].

FAQ: Implementation and Optimization

Q4: How can I effectively apply reinforcement learning to Discrete Diffusion Models (DDMs)?

Applying RL to DDMs is challenging due to their non-autoregressive, parallel generation nature. The MaskGRPO framework provides a viable solution. It introduces modality-specific innovations [35]:

- For Language: It uses a "fading-out masking estimator" that increases the masking rate for later tokens in a sequence, concentrating gradient updates on high-uncertainty regions.

- For Vision: It employs a sampler that encourages diverse yet high-quality rollouts by relaxing rigid scheduling constraints via probabilistic decoding, which is essential for effective group-wise comparisons in GRPO.

Q5: How can I stabilize the training of diffusion policies in online RL settings?

Conventional diffusion training requires samples from the target distribution, which is unavailable in online RL. The Reweighted Score Matching (RSM) method generalizes denoising score matching to eliminate this requirement. Two practical algorithms derived from RSM are [36]:

- Diffusion Policy Mirror Descent (DPMD)

- Soft Diffusion Actor-Critic (SDAC) These algorithms enable efficient online training of diffusion policies by using tractable, reweighted loss functions that align with policy mirror descent and max-entropy policy objectives.

Q6: What does "polymorph representation" mean in the context of generative material models, and how do diffusion RL architectures handle it?

In generative material models, "polymorph representation" refers to the ability to model a material system that can exist in multiple distinct structural forms (polymorphs) with the same composition. Diffusion RL architectures are inherently suited for this because of their strong multi-modal modeling capacity. They can learn a diverse dataset of successful strategies or structures without collapsing to a single mode, thus generating a variety of plausible polymorphic representations instead of a single, averaged solution [29] [30].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key quantitative results from recent research, providing benchmarks for model performance.

Table 1: Performance of TraceRL on Reasoning Benchmarks (Accuracy %)

| Model | MATH500 | LiveCodeBench-V2 | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| TraDo-4B-Instruct | - | - | Outperforms Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct |

| TraDo-8B-Instruct | 6.1% higher than Qwen2.5-7B | 51.3% higher than Llama3.1-8B | - |

| TraDo-8B-Instruct (Long-CoT) | 18.1% relative gain over Qwen2.5-7B | - | - |

Table 2: Performance of Efficient Online RL Algorithms on MuJoCo

| Algorithm | Task | Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|

| DPMD (Diffusion Policy Mirror Descent) | Humanoid & Ant | >120% improvement over Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the MaskGRPO Framework for Multimodal DDMs

This protocol outlines the steps to apply the MaskGRPO framework to optimize a Discrete Diffusion Model (DDM) on both language and vision tasks [35].

- Problem Formulation: Define your task (e.g., math reasoning, image generation) and prepare a dataset of prompts

cand target completions. - Model Setup: Initialize your pre-trained DDM, which defines a forward process that gradually corrupts data tokens to a mask token

mand a reverse denoising process parameterized byπ_θ. - Modality-Specific Rollout Generation:

- For Language: Use the model's inherent "ARness" (higher certainty near context) to generate a group of

Gdiverse rollouts{o1, o2, ..., oG}from the current policyπ_θ_old. - For Vision: Employ a probabilistic decoder that relaxes rigid scheduling to produce diverse and high-quality image rollouts for robust group-wise comparison.

- For Language: Use the model's inherent "ARness" (higher certainty near context) to generate a group of

- Reward and Advantage Calculation: For each rollout

o_i, a reward model or environment provides a scalar rewardr_i. Calculate the relative advantageA_ifor each rollout within its group using the formula:A_i = (r_i - mean({r_j}))/std({r_j}). - Modality-Specific Importance Estimation:

- For Language: Apply a "fading-out masking estimator" that uses a progressively increasing masking rate toward later tokens in the sequence.

- For Vision: Use a highly truncated mask rate to capture informative token variation, accounting for strong global correlations in images.

- Policy Optimization: Update the model parameters

θby maximizing the GRPO objective, which combines a clipped reward term and a KL-divergence penalty from the reference policy:max_θ E[R(θ, c) - β * D_KL(π_θ || π_ref)].

Protocol 2: Fine-tuning Diffusion Models with Efficient Human Feedback (HERO)

This protocol describes how to align a pre-trained text-to-image diffusion model with human preferences using the HERO method, which requires minimal human input [32].

- Base Model and Feedback Interface: Start with a pre-trained text-to-image diffusion model. Set up an interface that can present two generated images to a human labeller for a preference judgment.

- Data Collection: For a given text prompt, generate a pair of images. Collect binary preference labels from human labellers (e.g., A is better than B). The HERO framework is designed to be efficient, requiring less than 1,000 such comparisons.

- Model Fine-Tuning: Use the collected human feedback to fine-tune the base diffusion model. The HERO algorithm efficiently incorporates this sparse feedback to update the model's parameters, aligning its outputs with human preferences without requiring extensive retraining or large-scale reward model training.

Model Architecture and Workflow Diagrams

MaskGRPO for Multimodal Discrete Diffusion

Diffusion Model Training and Sampling

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Algorithms and Frameworks for Diffusion RL Research

| Reagent / Framework | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| TraceRL [37] [38] | RL Framework | A trajectory-aware RL framework for post-training Diffusion Language Models, enhancing reasoning on math and coding tasks. |

| MaskGRPO [35] | RL Optimization Algorithm | Enables scalable multimodal RL for Discrete Diffusion Models with modality-specific sampling and importance estimation. |

| Reweighted Score Matching (RSM) [36] | Training Objective | Enables efficient online RL for diffusion policies by generalizing denoising score matching, eliminating the need for target distribution samples. |

| DDIM (Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models) [31] [30] | Diffusion Sampler | Accelerates diffusion sampling by making the reverse process deterministic, allowing for fewer steps. |

| Di4C [33] | Distillation Method | Distills dimensional correlations in discrete diffusion models for faster, scalable sampling while retaining quality. |

| MetaDiffuser [34] | Meta-RL Framework | A diffusion-based conditional planner for offline meta-RL that improves generalization to new tasks. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is constrained generation and why is it important for materials research? Constrained generation is a natural language processing technique where language models are guided to produce text that adheres to specific predefined rules or structures. For materials researchers, this approach is invaluable for generating structured outputs like JSON-formatted material property data, ensuring outputs are both coherent and conform to desired schemas. This enhances both utility and reliability of AI-generated content for applications such as property prediction, synthesis planning, and molecular generation [39].

How does constrained generation technically work? The core mechanism involves manipulating a model's token generation to restrict next-token predictions to only those that don't violate required output structures. This is achieved through constrained decoding, where the model's output is directed to follow specific patterns. Fundamentally, this works by manipulating the raw logits (the model's raw output scores) - reducing probabilities of unwanted tokens by setting their logits to large negative values, effectively preventing their selection [40].

My model is generating invalid JSON syntax. What could be wrong? This common issue often occurs when constraints aren't properly applied during token sampling. Ensure you're using appropriate libraries or frameworks that support structured generation and validate that your schema definition matches the tokenizer's vocabulary. The problem may also arise from mismatches between text-level rules and the model's tokenization; some tokens may contain multiple characters that violate structural boundaries [40].

Can constrained generation improve my model's performance beyond just formatting? Yes. By reducing the complexity of the generation task and narrowing the prediction space, models can generate outputs more quickly and with greater accuracy. This efficiency gain is particularly beneficial in applications where rapid and reliable generation of structured text is crucial, such as high-throughput materials screening [39].

What's the difference between encoder-only and decoder-only models for property prediction? Encoder-only models (like BERT architectures) focus on understanding and representing input data, generating meaningful representations for further processing or predictions. Decoder-only models are designed to generate new outputs by predicting one token at a time, making them ideal for generating new chemical entities. The choice depends on whether your task emphasizes comprehension or generation [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Generates Structurally Invalid Outputs

Issue: Your constrained generation setup produces outputs that don't conform to the specified schema or format.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Verify constraint alignment with tokenizer vocabulary

- Check for tokenization mismatches in rule implementation

- Validate that all possible token paths maintain structural validity

- Ensure proper handling of special characters and delimiters

Solution:

Implement more granular constraint checking at the token level. Use libraries that provide regex or grammar-based constrained generation, ensuring rules evaluate on incomplete sequences. For example, implement a boolean function that returns True for valid sequences and False otherwise at each generation step [40].

Prevention:

- Test constraints with diverse inputs before full implementation

- Use established constrained generation frameworks when possible

- Implement validation checks at multiple generation steps

Problem: Poor Generation Quality with Constraints

Issue: Applying constraints significantly degrades the quality or coherence of generated content.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Evaluate if constraints are overly restrictive

- Check for conflicts between structural rules and semantic meaning

- Assess whether the model has sufficient capacity for constrained generation

- Verify constraint implementation isn't introducing biases

Solution: Gradually introduce constraints during training or fine-tuning rather than applying them only during inference. Consider implementing constrained fine-tuning where the model learns to generate valid structures without heavy inference-time restrictions. Alternatively, adjust constraint strictness using temperature parameters that modulate the sampling process [40].

Prevention:

- Balance constraint strictness with generation flexibility

- Use progressive constraint application during model training

- Regularly evaluate both structural validity and content quality

Problem: Handling Multiple Representation Formats

Issue: Difficulty managing conversions between different data representations (labelmaps, surface models, contours) while maintaining data consistency.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Identify all representation types in your workflow

- Check conversion algorithms between formats

- Verify data provenance tracking

- Assess consistency across representation conversions

Solution: Implement a polymorphic segmentation representation system using libraries like PolySeg, which provides automatic conversion between representation types while maintaining data consistency. This approach uses a complex data container that preserves identity and provenance of contained representations and ensures data coherence through automated on-demand conversions [42] [43].

Prevention:

- Use established libraries for representation management

- Implement automated consistency checks

- Maintain clear provenance tracking across conversions

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing JSON-Constrained Generation for Material Properties

Objective: Generate structured JSON outputs containing material property predictions using constrained generation.

Materials and Setup:

- DeepSeek R1 model or similar reasoning-capable model

- Fireworks API platform or equivalent infrastructure

- Python environment with

openai,pydantic, andrelibraries

Procedure:

- Define output schema using Pydantic:

Initialize API client and prepare input prompt:

Make API call with JSON response format:

Extract reasoning and JSON components using regex parsing:

Validate and parse JSON output into Pydantic model [39]

Validation:

- Verify JSON schema compliance

- Check property value ranges for physical plausibility

- Validate reasoning consistency with output data

Protocol 2: Logit Manipulation for Structural Constraints

Objective: Implement low-level constrained generation by directly manipulating model logits to enforce output structure.

Materials and Setup:

- HuggingFace Transformers library

- Pretrained language model (e.g., SmolLM2-360M)

- Python environment with NumPy

Procedure:

- Load model and tokenizer:

Generate logits for input prompt:

Extract and analyze logit values:

Implement constraint function to mask invalid tokens:

Sample from constrained logit distribution [40]

Validation:

- Verify constraint adherence in generated sequences

- Measure generation quality metrics

- Compare with unconstrained generation baseline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Constrained Generation Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| HuggingFace Transformers | Software Library | Model loading/inference | Access to pretrained models and constrained generation utilities [40] |

| Fireworks AI Platform | API Service | Model deployment | Hosted reasoning models with JSON output support [39] |

| PolySeg Library | Software Library | Representation management | Handling multiple segmentation formats with automatic conversions [42] [43] |

| VTK (Visualization Toolkit) | Software Library | 3D Visualization | Rendering and manipulation of complex material structures [42] [43] |

| axe-core | Accessibility Engine | Contrast validation | Ensuring color contrast meets WCAG guidelines for visualizations [44] [45] |

| DeepSeek R1 | Foundation Model | Reasoning with structured output | Generating explanations followed by JSON-formatted material data [39] |

Workflow Diagrams

Constrained Generation Process

Polymorphic Representation Management

Technical Implementation Examples

Advanced Constrained Generation Class

For researchers implementing custom constrained generation, here's a foundational class structure:

This implementation demonstrates the core concept of constrained generation by manipulating logits based on regular expression patterns, which can be adapted for various structural constraints in materials research [40].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common reasons for a reinforcement learning (RL) agent to generate chemically invalid or unstable materials?

This issue often originates from the choice of material representation and reward function design.

- Material Representation: Using string-based representations like SMILES can sometimes lead to syntactically or semantically invalid structures. While SELFIES representations are designed to be more robust, they can still produce chemically implausible compounds if the reward function does not explicitly penalize them [46].

- Reward Function: If the reward function focuses solely on a single target property (e.g., band gap) without including constraints for chemical validity (e.g., negative formation energy, charge neutrality, electronegativity balance), the agent may learn to "game" the system by generating compounds that score high on the target property but are unstable or unsynthesizable [47]. A well-designed reward function should incorporate multiple stability criteria.

FAQ 2: How can we effectively handle the exploration of polymorphs (different crystal structures of the same composition) in generative RL workflows?

Handling polymorphism remains a significant challenge, as many current generative models for materials operate primarily on composition rather than full crystal structure.

- Current Limitations: Most RL frameworks for inorganic materials design generate chemical formulas but do not simultaneously predict their stable crystal structure. An agent might identify a promising composition, but its properties in reality depend on which polymorph is synthesized [47] [22].

- Proposed Workflow: A practical solution is a multi-stage approach. First, the RL agent discovers target compositions that meet property objectives. Then, template-based crystal structure prediction or other computational methods are used to propose feasible crystal structures for these compositions, allowing for the assessment of different polymorphs [47]. Future frameworks that integrate structure generation directly into the RL loop are necessary to fully address this challenge within a single model.

FAQ 3: Our RL model has converged, but the generated materials lack diversity. What strategies can improve the exploration of the chemical space?

This is a classic problem of exploitation vs. exploration.

- Intrinsic Rewards: Incorporate intrinsic rewards to encourage curiosity. These rewards are not based on the target property but on the novelty of the generated material itself. Methods include:

- Diversity Filters: Implementing memory-based approaches that group compounds by scaffold and penalize the agent for over-exploiting a particular structural motif, thereby encouraging structural novelty [46].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for formulating a reward function for multi-objective optimization (e.g., maximizing a property while minimizing synthesis temperature)?

The key is to construct a weighted, combined reward function that reflects the relative importance of each objective.

- Standard Formulation: The total reward ( R_t ) at a given step is typically defined as:

- Application Example: If your goal is to design a material with a high bulk modulus (with high priority) and a low calcination temperature (with lower priority), you would assign a larger weight ( w1 ) to the bulk modulus reward and a smaller weight ( w2 ) to the calcination temperature reward. This guides the agent to prioritize the primary objective while still satisfying the secondary one [47].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Slow or Failed Convergence in Policy Training

Problem Description: The RL agent fails to learn an effective policy for generating high-performing materials, or the learning process is unacceptably slow.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sparse Rewards | Check if the agent receives a non-zero reward only upon generating a complete, successful material. | Implement reward shaping. Provide small, intermediate rewards for achieving sub-goals, such as forming a charge-neutral fragment or including a specific necessary element [47]. |

| Ineffective Exploration | Analyze the diversity of generated materials over time. If the same or similar compounds are repeatedly generated, exploration is poor. | Integrate an adaptive intrinsic reward mechanism, such as a combination of random distillation networks and counting-based strategies, to incentivize the discovery of novel structures [46]. |

| Unstable Policy Updates | Observe large fluctuations in policy performance and reward scores during training. | Switch to a more stable policy gradient algorithm like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which constrains the size of policy updates to prevent destructive policy changes [46]. |

Issue: Generated Materials are Theoretically Sound but Synthetically Infeasible

Problem Description: The RL agent proposes materials with excellent computed properties, but their synthesis is impractical due to extreme processing conditions.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring Synthesis Objectives | Verify if the reward function is based solely on final material properties without synthesis considerations. | Reformulate the reward function to be multi-objective. Include synthesis parameters like sintering temperature and calcination temperature as explicit objectives to be minimized within the reward function [47]. |

| Data Bias | Check if the training data is biased towards materials with high synthesis temperatures. | Curate training data or adjust rewards to favor lower-temperature synthesis pathways, if such data is available. Use predictor models trained to estimate synthesis conditions from composition [47]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard RL Workflow for Inverse Materials Design

The diagram below illustrates the core feedback loop for goal-directed materials generation using reinforcement learning.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Problem Formulation:

- State (sₜ): Define the state as the material composition at step t. This can start as an empty set or a partial formula [47].

- Action (aₜ): Define the action as the selection of an element (from a set of permissible elements, e.g., 80) and its corresponding stoichiometric number (e.g., an integer from 0 to 9). An action of '0' means the element is not added. The sequence is often capped at a horizon (e.g., T=5 steps for oxides, where the final step is reserved for oxygen) [47].

- Reward (Rₜ): Formulate the reward function based on your objectives (see FAQ 4). The reward is typically zero for all non-terminal steps and is computed only when a complete material formula is generated [47].

Model Initialization:

- Initialize the policy network (the agent). For policy-based methods (like PGN), this network directly outputs a probability distribution over actions. For value-based methods (like DQN), it learns a value function for state-action pairs [47].

Interaction Loop:

- The agent interacts with the environment over multiple episodes.

- For each step in an episode, the agent takes an action aₜ based on its current policy, transitioning the state from sₜ to sₜ₊₁.

- Once a terminal state is reached (a complete material is generated), the material's properties are predicted using a pre-trained supervised learning model (the predictor) [47].

Learning and Update:

- The reward is calculated based on the predicted properties.

- The agent's policy is updated using a reinforcement learning algorithm (e.g., Policy Gradient for PGN, or Q-learning for DQN) to maximize the expected cumulative reward [47].

- The process repeats from step 3 for a specified number of iterations or until performance converges.

Workflow for Multi-Objective Optimization with Intrinsic Rewards

This workflow enhances the standard RL loop with mechanisms to improve exploration and handle multiple, potentially conflicting, goals.

Key Enhancements:

- Dual Reward Stream: The total reward is a sum of the extrinsic reward (for target properties) and an intrinsic reward (for exploration) [46].

- Intrinsic Reward Calculation: This can be computed via:

- Multi-Objective Extrinsic Reward: The extrinsic reward itself is a weighted sum of rewards from multiple property predictors, as described in the standard protocol [47].

Performance Data & Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance of RL Methods

The following table summarizes performance metrics reported for various RL-based material generation frameworks, highlighting their sample efficiency and success rates.

| Model / Framework | Key Properties Optimized | Performance Metrics | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatInvent [48] | Electronic, magnetic, mechanical, thermal, physicochemical properties. | Converges to target values within ~60 iterations (~1,000 property evaluations). Reduces property computations by up to 378x compared to state-of-the-art. | High sample efficiency and compatibility with diverse diffusion model architectures. |

| PGN & DQN for Inorganic Oxides [47] | Band gap, formation energy, bulk/shear modulus, sintering/calcination temperature. | Successfully generates novel compounds with high validity, negative formation energy, and adherence to multi-objective targets. | Effectively handles multi-objective optimization combining property and synthesis objectives. |

| Mol-AIR [46] | Penalized LogP, QED, Drug-likeness, Celecoxib similarity. | Demonstrates improved performance over existing approaches in generating molecules with desired properties without prior knowledge. | Uses adaptive intrinsic rewards to enhance exploration in vast chemical space. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential computational "reagents" and tools used in building RL workflows for materials optimization.

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Material Representation | Encodes the material in a format understandable by the RL model. | SELFIES: Robust string representation, ensures syntactic validity [46]. Composition Vectors: Simple representation of elemental components [47]. Crystal Graphs: Captures full structural information but is complex to decode [22]. |

| Predictor Model | A surrogate model that rapidly evaluates the properties of a generated material, providing the reward signal. | Can be a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, Neural Network) trained on existing materials data (e.g., from Materials Project [47]). Accuracy is critical for a reliable reward. |

| RL Algorithm | The core "brain" that learns the generation policy. | Policy Gradient Networks (PGN): Directly optimize the policy [47]. Deep Q-Networks (DQN): Learn a value function to derive a policy [47]. Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): Offers more stable training [46]. |

| Intrinsic Reward Module | An optional component that generates bonus rewards for exploration. | Counting-Based: Simple to implement, requires a state-visitation memory [46]. RND: More generalizable novelty detection, adds computational overhead [46]. |

In the context of generative models for materials research, accurately representing and distinguishing between packing polymorphs is a fundamental challenge. The stability relationships between polymorphs are governed by subtle differences in free energy, which are computationally expensive to determine with high-fidelity methods like meta-GGA Density Functional Theory (DFT) or coupled cluster techniques [49] [50]. Multi-fidelity simulation frameworks address this by strategically combining abundant, lower-cost data from Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) or generalized gradient approximation (GGA) DFT with sparse, high-fidelity calculations. This approach enables the accurate learning of high-fidelity potential energy surfaces (PES) with minimal high-fidelity data, which is particularly crucial for predicting polymorph stability where free energy differences can be exceptionally small [49]. For generative models targeting novel material discovery, this methodology provides a pathway to create highly accurate bespoke or universal MLIPs by effectively expanding the effective high-fidelity dataset, thereby enhancing the reliability of generated candidates [49] [24].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Poor High-Fidelity Extrapolation in Unsampled Regions

Problem Statement The model performs well on geometric and compositional spaces present in the high-fidelity training data but shows poor accuracy and unstable molecular dynamics in unsampled regions of the configuration space.

Diagnosis Procedure

- Analyze Configuration Space Coverage: Compare the distributions of key structural descriptors (e.g., radial distribution functions, angles) between your low-fidelity and high-fidelity datasets.

- Identify Knowledge Gaps: Map the regions where high-fidelity data is sparse or absent but low-fidelity data is abundant.