Strategies for Preventing Homogeneous Nucleation and Bulk Solution Scaling: Mechanisms, Control Methods, and Industrial Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of homogeneous nucleation control strategies to mitigate bulk solution scaling, a critical challenge in industrial processes including pharmaceutical development.

Strategies for Preventing Homogeneous Nucleation and Bulk Solution Scaling: Mechanisms, Control Methods, and Industrial Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of homogeneous nucleation control strategies to mitigate bulk solution scaling, a critical challenge in industrial processes including pharmaceutical development. We explore the fundamental mechanisms driving scale formation, examine chemical-free intervention technologies like electromagnetic fields, and present optimization frameworks for supersaturation management. By integrating recent advances in computational modeling, process intensification, and experimental validation, this review serves as a strategic guide for researchers and engineers seeking to improve system reliability, reduce chemical usage, and enhance operational efficiency in scaling-prone environments.

Understanding Homogeneous Nucleation: Fundamental Mechanisms and Scaling Drivers

Defining Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation Pathways

Fundamental Definitions & Mechanisms

What are the fundamental definitions of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation?

- Homogeneous Nucleation is a process where the formation of a new thermodynamic phase (e.g., a crystal from a solution or a liquid from a vapor) occurs spontaneously and randomly within the bulk of the parent phase, without the influence of any foreign surfaces or impurities. It requires the melt or solution to be absolute pure, and not in contact with any external surface [1].

- Heterogeneous Nucleation is a process where the formation of the new phase is facilitated by the presence of a pre-existing surface. This surface can be the container wall, foreign particles, impurities, or any other interface within the system [2].

What is the core mechanistic difference between these pathways?

The core difference lies in the energy barrier that must be overcome to form a stable nucleus. Homogeneous nucleation has a significantly higher energy barrier because the new phase must form entirely from fluctuations within the parent phase, creating a new interface in all directions. Heterogeneous nucleation has a lower energy barrier because the existing surface acts as a template, reducing the amount of new interface that needs to be created [2].

Table: Core Characteristics of Nucleation Pathways

| Feature | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Randomly within the bulk parent phase [1] | At pre-existing surfaces or interfaces (e.g., impurities, vessel walls) [2] |

| Energy Barrier | High [2] | Lower, due to reduced surface energy penalty [2] |

| Supercooling/Supersaturation Required | High [1] | Low to moderate [2] |

| Stochastic Nature | Highly stochastic (random) [2] | Less stochastic, often dictated by surface properties |

| Prevalence in Real Systems | Rare, idealized [3] | Dominates in most real-world systems [2] |

Troubleshooting Scaling in Bulk Solution

Why does my experiment experience rapid, uncontrolled scaling on membrane and reactor surfaces?

This is a classic sign that your system is dominated by heterogeneous nucleation. When the supersaturation rate is high, the driving force for phase separation is large. If the energy barrier for homogeneous nucleation is still higher than that for heterogeneous nucleation—which is almost always the case—the system will preferentially form nuclei on any available surface, leading to scaling [4] [5]. This is because surfaces effectively lower the critical energy requirement for nucleation [2].

How can I shift nucleation from a heterogeneous (scaling) pathway to a homogeneous (bulk) pathway to prevent scaling?

The primary strategy is to increase the supersaturation driving force to a point where the energy barrier for homogeneous nucleation becomes comparable to or lower than that of heterogeneous nucleation on the available surfaces.

- Increase Supersaturation Rate: Experimental work in membrane distillation crystallisation (MDC) has shown that increasing the supersaturation rate (e.g., by using a larger membrane area to increase water vapor flux) can reduce induction time, broaden the metastable zone width, and reduce scaling. The increased volume free energy provided by elevated supersaturation reduces the critical energy requirement for nucleation, favoring a homogeneous primary nucleation mechanism in the bulk solution over surface-based heterogeneous nucleation [4] [5].

- Use In-line Filtration: Implementing in-line filtration to keep formed crystals in the bulk crystalliser and prevent their deposition on surfaces has been shown to mitigate scaling. This maintains a consistent supersaturation rate and allows for longer hold-up times, which can further desaturate the solvent through crystal growth, reducing the driving force for further nucleation on surfaces [5].

My system is highly supersaturated, yet I still observe scaling. What could be the issue?

Even at high supersaturation, the presence of highly active nucleating surfaces (e.g., rough reactor walls, certain impurity particles) can still make heterogeneous nucleation the kinetically favored pathway. Research using minimal models has shown that the behavior of impurities can be complex; they can act as surfactants, solution stabilizers, spectator clusters, or active nucleants depending on their interaction strength with the solvent and solute particles [6]. You may need to:

- Improve Solution Purity: Further purify your solvent and solute to remove microscopic impurities that act as nucleation sites [2].

- Modify Surface Properties: Consider using reactor materials with low surface energy or applying coatings that reduce the wettability/adhesion of the nucleating phase.

Quantitative Analysis & Metastable Zone

How are the energy barrier and critical nucleus size quantitatively defined?

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the following key equations, particularly for homogeneous nucleation [1] [3]:

Critical Radius (r*): The minimum radius a nucleus must have to be stable and likely to grow. ( r^* = -\frac{2 \gamma{sl}}{\Delta GV} ) where ( \gamma{sl} ) is the solid-liquid specific surface energy and ( \Delta GV ) is the change in Gibbs free energy per unit volume.

Critical Gibbs Free Energy Barrier (( \Delta G{Hom}^* )): The energy barrier that must be overcome for homogeneous nucleation. ( \Delta G{Hom}^* = \frac{16 \pi \gamma{sl}^3}{3 \Delta GV^2} )

The driving force ( \Delta GV ) is related to supercooling (( \Delta T )) by ( \Delta GV = -\frac{\Delta Hm \Delta T}{Tm} ), where ( \Delta Hm ) is the latent heat of melting and ( Tm ) is the melting point [1]. This shows that both the critical radius and the energy barrier decrease as supercooling/supersaturation increases.

Table: Key Parameters Influencing Nucleation Kinetics

| Parameter | Impact on Nucleation & Crystallization | Experimental Control Knob |

|---|---|---|

| Supersaturation Rate | Increased rate shortens induction time, broadens Metastable Zone Width (MSZW), and can favor homogeneous nucleation in the bulk over scaling [4]. | Membrane area, flux, temperature difference [4]. |

| Supersaturation at Induction | Higher levels mitigate scaling and favor bulk nucleation by providing a greater driving force [5]. | Controlled by the concentration rate via parameters like membrane area [5]. |

| Magma Density | An increase in crystal mass per unit volume (magma density) can narrow the MSZW and influence secondary nucleation [4]. | Seeding strategies, crystal slurry recycling. |

| Crystallizer Volume | Modifying volume can increase the MSZW without changing the boundary layer, affecting the number of nucleation events [4]. | Reactor and crystallizer design. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Homogeneous Nucleation Conditions in Membrane Distillation Crystallization

Objective: To achieve bulk homogeneous nucleation of a solute (e.g., NaCl) to prevent membrane scaling.

Methodology:

- Setup: Use a membrane distillation crystallisation (MDC) system with a controlled temperature difference across the membrane to generate water vapor flux [4].

- Supersaturation Control: Increase the supersaturation rate by utilizing a larger active membrane area. This modifies the kinetics without altering the fundamental mass and heat transfer boundary layer [4] [5].

- Monitoring: Track the solution concentration and temperature in the crystallizer in real-time.

- Induction Point Detection: Record the induction time, defined as the time at which a sudden drop in solution concentration or the visual appearance of crystals in the bulk solution is detected.

- Analysis: Confirm homogeneous nucleation by observing a broadened Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) and a reduction in scale formation on the membrane surface compared to experiments run at lower supersaturation rates [4] [5].

Protocol 2: Nanopipette Electrochemical Measurement of Induction Time

Objective: To precisely measure the nucleation induction time for a poorly soluble salt (e.g., amorphous calcium carbonate) at the nanoscale.

Methodology:

- Setup: Prepare a nanopipette and fill it with the solution of interest. Set up an electrochemical cell with electrodes on either side of the nanopipette tip [6].

- Measurement: Apply a potential difference to drive an ionic current through the nanopipette orifice. Introduce the precipitating agent to create a supersaturated condition inside or near the tip.

- Detection: Monitor the ionic current continuously. The formation and growth of a nucleus of a critical size within the nanopipette will block the orifice, leading to a sudden, sharp drop in the measured current.

- Analysis: The time between the creation of supersaturation and the current blockage event is the nucleation induction time. This can be repeated at different supersaturations to build a kinetic profile [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Nucleation Pathway Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | To minimize unintentional heterogeneous nucleation sites from impurities [2]. |

| Diatomaceous Earth / Copper Sulfide | Examples of nucleating agents studied to understand and control heterogeneous nucleation in specific salt systems [1]. |

| Specific Nanomaterials (e.g., Al₂O₃) | Act as designed heterogeneous nucleation sites; their effectiveness can be influenced by surfactants which change the solution's contact angle and nucleation free energy [1]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., SDBS) | Used to modify interfacial energies and the stability of nanofluids; they can affect the agglomeration of nanomaterials and their efficacy as nucleants [1]. |

| Seeds (Pre-formed Crystals) | Used to initiate and study secondary nucleation, bypassing the primary nucleation barrier, and to control crystal size distribution [4]. |

| In-line Filters | Used to retain crystals in the bulk crystallizer, preventing deposition (scaling) and allowing for better control of supersaturation [5]. |

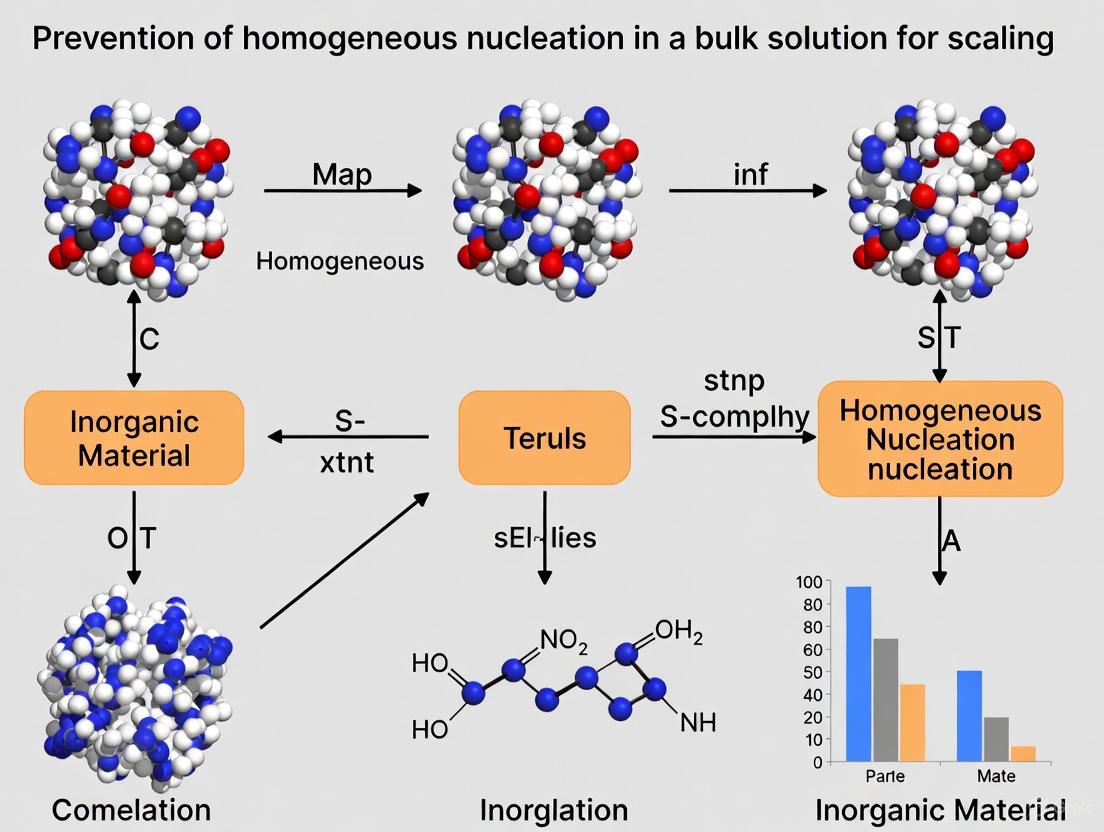

Conceptual Diagrams & Workflows

Diagram: Competing Nucleation Pathways and Control Strategy.

Diagram: Workflow for Preventing Scaling via Homogeneous Nucleation.

The Role of Supersaturation as Primary Driving Force for Scaling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental role of supersaturation in scaling? Supersaturation is the primary thermodynamic driving force for scaling. It occurs when the concentration of dissolved ions (e.g., calcium and carbonate) exceeds the equilibrium solubility product of a salt like calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) [7]. This state of excess provides the necessary energy for the formation of solid phases, initiating the process of nucleation and crystal growth on surfaces [8].

2. How does homogeneous nucleation differ from heterogeneous nucleation in scaling? Homogeneous nucleation is the spontaneous formation of crystal nuclei within the bulk solution when supersaturation reaches a critical threshold. In contrast, heterogeneous nucleation occurs on pre-existing surfaces (like pipe walls or pre-formed scale), which lower the energy barrier for nucleation. Scaling in industrial systems is predominantly heterogeneous, as surfaces provide ideal sites for crystal nucleation and growth [9] [7].

3. Why is controlling supersaturation critical in drug development? In drug development, controlling supersaturation during formulation is essential to ensure consistent product quality and efficacy. Precipitation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) due to supersaturation can alter critical quality attributes (CQAs) such as potency and stability [10] [11]. Furthermore, a failure to consider the challenges of scaling up production, which can drastically change supersaturation conditions, is a major hurdle in commercializing new drugs [10].

4. What are common experimental methods to measure scaling propensity? Common methods include:

- Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM): Measures mass changes on a sensor crystal to detect scale deposition in real-time [7].

- Langelier Saturation Index (LSI): A calculated index used to predict the scaling or corrosive tendency of water based on pH, calcium hardness, alkalinity, and temperature [9].

- Fast Controlled Precipitation Method: Assesses the scale-forming ability of water samples by inducing controlled supersaturation [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unpredictable and Rapid Scale Formation in Laboratory Recirculating System

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| # | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unmonitored Supersaturation | Calculate the Langelier Saturation Index (LSI) for your water. A positive LSI indicates a tendency to form calcium carbonate scale [9]. | Implement real-time monitoring of key water chemistry parameters (pH, conductivity, calcium concentration) to track the supersaturation coefficient [7]. |

| 2 | Inadequate Chemical Inhibition | Perform scaling tests with and without threshold inhibitors to determine the minimum effective dosage [9]. | Introduce threshold inhibitors, such as phosphonates or low molecular weight polymers, which adsorb to emerging crystals and block active growth sites [9]. |

| 3 | Fluctuating Temperature and Flow | Log temperature and flow rate data to identify correlations with scaling events. | Stabilize operational parameters. Increase water velocity to enhance turbulence and reduce stagnant zones where scale can form [9]. |

Problem 2: Inconsistent Results When Scaling Laboratory Findings to Pilot Plant

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| # | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Overlooked Scale-Up Considerations | Audit the formulation design process for parameters that are difficult to maintain at a larger scale, such as mixing efficiency and heat transfer [10]. | Incorporate scalability into early-stage formulation research, focusing on excipient selection and unit operations that are transferable to commercial production [10]. |

| 2 | Changes in Fluid Dynamics | Compare Reynolds numbers and shear forces between the lab-scale and pilot-scale equipment. | Conduct engineering runs at a pilot scale to validate the process and identify fluid dynamic issues before full-scale GMP production [11]. |

| 3 | Shift in Nucleation Mechanism | Analyze the scale crystals from both setups; differences in polymorph or crystal size distribution can indicate a shift from homogeneous to heterogeneous nucleation. | Design the process to operate at subsaturated conditions where possible, or ensure that anti-scaling chemicals are dosed proportionally and mixed effectively at the larger scale [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Scaling Rate and Propensity Using a Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM)

1. Objective: To directly measure the kinetics of scale deposition on a surface as a function of solution supersaturation [7].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- QCM with gold electrodes

- Lab-made miniaturized flow cell

- Synthetic water prepared from calcium carbonate and pure water (Milli-Q quality)

- CO₂ gas cylinder

- Temperature-controlled water bath

- Data acquisition system for frequency monitoring

3. Methodology:

- Pre-calcification of Sensor Surface: The sensitive surface of the QCM is pre-coated with a layer of pure calcite. This is achieved by immersing the electrode in a supersaturated calcium carbonate solution and applying a potential of -1 V/SCE to reduce dissolved oxygen, which increases local pH and induces calcite formation [7].

- Solution Preparation: Synthetic water is prepared by dissolving solid calcium carbonate in pure water under a CO₂ atmosphere, resulting in a slightly acidic solution (pH ~5.2-5.5) with no spontaneous precipitation [7].

- Inducing Supersaturation: The test solution is brought to the desired supersaturation coefficient by controlled degassing of dissolved CO₂, which increases the pH and drives the solution toward CaCO₃ precipitation [7].

- Measurement: The pre-calcified QCM sensor is installed in the flow cell, and the test solution is circulated over it. The scaling rate (mass deposition per unit time) is determined by monitoring the change in the sensor's resonant frequency, which is directly related to the mass deposited on its surface [7].

4. Data Analysis:

- The instantaneous scaling rate is calculated from the frequency shift.

- A relationship is established between the measured scaling rate and the supersaturation coefficient of the water.

- The activation energy for the scaling process can be determined by conducting experiments at different temperatures [7].

Protocol 2: Determining the Efficacy of Threshold Inhibitors

1. Objective: To evaluate the performance of chemical additives in retarding calcium carbonate scale formation.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Test chemicals: e.g., phosphonates (e.g., HEDP), polyacrylate polymers [9].

- Synthetic hard water (e.g., 200 mg/L Ca²⁺ as CaCO₃).

- Laboratory stirrer or recirculating test loop.

- Heated surfaces or heat exchange elements.

- Analytical equipment for calcium hardness (e.g., EDTA titraton or ICP-OES).

3. Methodology:

- Prepare a baseline synthetic water with a known, scaling-prone composition (positive LSI) [9].

- Set up a controlled experiment where the test water is heated or evaporated to induce supersaturation, both with and without the inhibitor.

- Run tests over a set duration, maintaining constant temperature and mixing conditions.

- Assess scaling by measuring the reduction in solution calcium hardness over time, by weighing deposited mass on test coupons, or by monitoring the performance of a heated surface.

4. Data Analysis:

- Compare the scaling rates or total mass deposited in the presence and absence of the inhibitor.

- The inhibitor's effectiveness is demonstrated by a delay in the onset of precipitation and a reduction in the amount of scale formed, even at dosages far below the stoichiometric amount required to chelate all calcium ions [9].

Data Presentation

| Supersaturation Coefficient | Temperature (°C) | Scaling Rate (ng cm⁻² s⁻¹) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.5 | 30 | 4.5 | Measurable deposition occurs |

| 6.5 | 30 | 12.0 | Deposition rate increases significantly |

| 7.5 | 30 | 28.5 | High scaling propensity |

| 5.5 | 40 | 8.0 | Higher temperature accelerates scaling |

| 6.5 | 40 | 20.5 | Marked increase in scaling rate |

| 7.5 | 40 | 45.0 | Very high scaling rate observed |

Note: The scaling rate increases with both the supersaturation coefficient and temperature. The activation energy for the scaling process on a pre-calcified surface in synthetic water was found to be approximately 22 kJ mol⁻¹ [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Scaling Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Calcium Carbonate (AnalaR grade) | Primary source of Ca²⁺ and CO₃²⁻ ions for preparing synthetic scaling solutions [7]. |

| Phosphonate-based Inhibitors (e.g., HEDP) | Acts as a threshold inhibitor; adsorbs onto crystal growth sites, distorting crystal lattice and preventing further growth [9]. |

| Polyacrylate Polymers | Serves as both a threshold inhibitor and a dispersant; prevents agglomeration of microcrystallites [9]. |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) with Pre-calcified Sensor | Highly sensitive in-situ sensor for real-time detection and quantification of scale mass deposition on a surface [7]. |

| CO₂ Gas | Used to prepare and control the supersaturation of synthetic water by adjusting the carbonate equilibrium through degassing [7]. |

Diagram Specifications

Scaling Process and Inhibition

Scaling Zones and Regimes

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) is the primary theoretical model used to quantitatively study the kinetics of nucleation, which is the first step in the spontaneous formation of a new thermodynamic phase from a metastable state [12]. For researchers focused on preventing homogeneous nucleation and bulk solution scaling, understanding the energy barriers and critical radius is fundamental. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to address specific experimental challenges in controlling nucleation within pharmaceutical and materials research.

Key Concepts: FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the critical radius and why is it important?

The critical radius ((rc)) is the minimum size a nascent nucleus must achieve to become stable and proceed to grow spontaneously. Nuclei smaller than this radius are unstable and will dissolve, while those larger are stable and will continue to grow [12] [13]. The critical radius is defined by the equation: [ rc = \frac{2\sigma}{|\Delta gv|} ] where (\sigma) is the surface tension and (\Delta gv) is the Gibbs free energy change per unit volume. This concept is crucial for designing experiments to prevent scaling, as it defines the thermodynamic stability limit of nuclei.

FAQ 2: What is the nucleation energy barrier and what factors influence it?

The nucleation energy barrier ((\Delta G^)) is the maximum free energy that must be overcome to form a stable nucleus [12]. For homogeneous nucleation, this barrier is given by: [ \Delta G^ = \frac{16\pi\sigma^3}{3|\Delta gv|^2} ] The height of this barrier is extremely sensitive to the surface tension ((\sigma)) and the volumetric free energy change ((\Delta gv)). A higher barrier makes nucleation less likely. In practice, the supersaturation of the solution is a key parameter controlling (\Delta g_v); higher supersaturation lowers both the critical radius and the energy barrier, making nucleation more probable [12] [13].

FAQ 3: How does homogeneous nucleation differ from heterogeneous nucleation in practical terms?

Homogeneous nucleation occurs spontaneously within the bulk solution without a foreign surface, while heterogeneous nucleation occurs on surfaces like container walls, dust, or intentionally added impurities [12]. The free energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation, (\Delta G^{het}), is always lower than that for homogeneous nucleation, (\Delta G^{hom}), and is reduced by a factor (f(\theta)): [ \Delta G^{het} = f(\theta) \Delta G^{hom}, \qquad f(\theta) = \frac{2-3\cos\theta + \cos^3\theta}{4} ] where (\theta) is the contact angle between the nucleus and the foreign surface [12]. For scaling prevention, this means that heterogeneous nucleation on equipment surfaces is often the dominant and more difficult problem to control than homogeneous nucleation in the bulk.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative relationships and parameters from CNT for easy reference.

Table 1: Fundamental Equations in Classical Nucleation Theory

| Concept | Mathematical Formula | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Radius [12] | ( r_c = \frac{2\sigma}{ | \Delta g_v | } ) | (\sigma): Surface tension(\Delta g_v): Volumetric free energy change |

| Homogeneous Nucleation Barrier [12] | ( \Delta G^* = \frac{16\pi\sigma^3}{3 | \Delta g_v | ^2} ) | (\sigma): Surface tension(\Delta g_v): Volumetric free energy change |

| Heterogeneous Nucleation Barrier [12] | ( \Delta G^{het} = f(\theta) \Delta G^{hom} ) | (f(\theta)): Factor based on contact angle (\theta) | ||

| Nucleation Rate [12] | ( R = NS Z j \exp\left(-\frac{\Delta G^*}{kB T}\right) ) | (NS): Number of nucleation sites(Z): Zeldovich factor(j): Rate of monomer attachment(kB): Boltzmann constant(T): Temperature |

Table 2: Impact of Supersaturation on Nucleation Parameters (Illustrative)

| Supersaturation | Critical Radius ((r_c)) | Energy Barrier ((\Delta G^*)) | Nucleation Rate ((R)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Large | High | Very Slow |

| Medium | Medium | Medium | Moderate |

| High | Small | Low | Very Fast |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Uncontrollable and rapid nucleation occurs during experiments.

- Potential Cause: The solution supersaturation is too high, leading to a very low energy barrier and a small critical radius [12] [13].

- Solution: Carefully control the rate at which supersaturation is generated. A slower supersaturation rate can broaden the metastable zone width (MSZW), giving you a larger operating window before nucleation initiates [4]. Techniques include slower solvent evaporation, controlled temperature reduction, or precise addition of antisolvents.

Problem: Experimental nucleation rates do not match theoretical CNT predictions.

- Potential Cause 1: The "capillary assumption" in CNT, which treats small clusters of molecules as having the same interfacial properties as the bulk macroscopic solid, is often inaccurate [13].

- Solution: Be aware that CNT provides a qualitative framework and often requires correction factors for quantitative prediction. Consider that nucleation may follow non-classical pathways, such as forming stable pre-nucleation clusters or proceeding through an amorphous intermediate phase before crystallizing [13] [6].

- Potential Cause 2: The presence of unintended impurities or surfaces is catalyzing heterogeneous nucleation, which has a different rate than the homogeneous process you may be modeling [12].

- Solution: Implement rigorous solution filtration and use containers with well-characterized surface properties to minimize uncontrolled heterogeneous nucleation.

Problem: Difficulty in reproducing nucleation induction times.

- Potential Cause: Primary nucleation is an inherently stochastic (probabilistic) process, especially at low supersaturations [14].

- Solution: Perform a large number of replicate experiments (e.g., using parallel reactors like the Crystalline instrument) and analyze the data using statistical cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) to obtain meaningful kinetic parameters instead of relying on single measurements [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Measuring Nucleation Kinetics

This protocol is adapted from a vial-scale evaporative crystallization method used for sodium chloride, which is ideal for systems with temperature-insensitive solubility [14].

Objective: To measure the nucleation kinetics and metastable zone width of a compound under controlled evaporation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Parallel Reactor System (e.g., Crystalline instrument with 8x mL vials) | Allows for multiple experiments under identical conditions for statistical analysis of stochastic nucleation [14]. |

| Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs) | Precisely regulates the flow of dry air to each vial, enabling controlled and reproducible evaporation rates [14]. |

| In-situ Laser-based Transmissivity Probe | Detects the moment of nucleation in real-time as a sharp drop in light transmission through the solution [14]. |

| Magnetic Stirrer | Ensures uniform concentration and temperature throughout the solution, minimizing concentration gradients. |

| Temperature Control System | Maintains a constant, precise temperature for the experiment, a key parameter in nucleation kinetics [14]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Preparation: Prepare a solution of your compound at a known initial saturation ratio (e.g., S₀ = 0.8). Filter the solution to remove dust and particulate matter that could act as heterogeneous nucleation sites.

- Setup: Load a precise volume of the solution into each vial of the parallel reactor system. Ensure the temperature control, stirring, and in-situ transmissivity monitoring are active and calibrated.

- Evaporation: Initiate the flow of dry air through the MFCs at a defined, constant rate and temperature. This begins the controlled generation of supersaturation.

- Monitoring: Continuously monitor the transmissivity of the solution in each vial. The experiment is automated to record the precise time at which a sharp, sustained decrease in transmissivity occurs, indicating a nucleation event.

- Data Collection: Repeat the experiment across multiple vials and under different conditions (e.g., varying temperature, airflow rate, initial concentration) to build a robust dataset.

- Data Analysis:

- Convert the recorded nucleation times into supersaturation values at the point of nucleation.

- Plot the data as cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) for time and supersaturation.

- Fit the supersaturation data to a CNT-based model to estimate nucleation parameters like the interfacial energy and pre-exponential factor [14].

Experimental Workflow for Nucleation Kinetics

Advanced Considerations: Beyond Classical Nucleation Theory

CNT, while useful, is based on simplifications and can fail to quantitatively predict experimental data [13]. Be aware of these advanced concepts:

Non-Classical Nucleation: Evidence suggests that some systems, like calcium carbonate, do not nucleate via the direct formation of a critical crystal. Instead, they may follow a two-step mechanism: First, the formation of thermodynamically stable, amorphous pre-nucleation clusters (PNCs). Second, the aggregation and reorganization of these PNCs into a stable solid phase [13] [6]. This pathway can have a significantly lower energy barrier than predicted by CNT.

Challenges from Simulation: Molecular simulations have shown that "real world" crystal nuclei are often disordered and do not resemble the ideal, perfectly ordered structures assumed in the capillary approximation of CNT [6]. This can lead to inaccuracies in calculating the interfacial energy ((\sigma)) and thus the nucleation barrier.

Classical vs. Non-Classical Nucleation Pathways

Fundamental Scaling Mechanisms and FAQs for Researchers

This guide addresses the formation and prevention of common inorganic scales—carbonates, sulfates, and silica—providing targeted support for research on controlling homogeneous nucleation in bulk solutions.

What are the primary scaling salts I will encounter in aqueous laboratory systems?

The most common scaling salts are calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), calcium sulfate (CaSO₄), barium sulfate (BaSO₄), and silica (SiO₂) [15] [16]. These salts form when the concentration of their constituent ions in water exceeds the solubility limit, a state known as supersaturation [15] [17].

- Calcium Carbonate (CaCO₃): Its solubility decreases as temperature increases, making it a frequent problem in systems involving heat transfer, such as heat exchangers or boilers [15] [18]. Its formation is highly dependent on pH and the partial pressure of CO₂ [15].

- Calcium Sulfate (CaSO₄): This scale exists in different crystalline forms (e.g., gypsum, anhydrite) and is particularly challenging because it is practically insoluble in hydrochloric acid, a common cleaning agent for other scales [17].

- Barium Sulfate (BaSO₄): This is one of the least soluble sulfate scales [15]. Its formation is often triggered by the mixing of incompatible waters, such as barium-rich formation water with sulfate-rich seawater in oil and gas production [17].

- Silica (SiO₂): Silica scaling is complex and difficult to remove due to its hard texture and insolubility in ordinary acids or alkalis [19].

What is the core difference between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation in scaling?

The core difference lies in the location and energy requirement for the initial formation of stable scale crystals.

- Homogeneous Nucleation occurs spontaneously in the bulk solution when the level of supersaturation is high enough to allow ions to spontaneously form stable clusters without a solid surface [20]. This requires a high energy barrier to be overcome.

- Heterogeneous Nucleation occurs on solid surfaces, such as the walls of pipes, vessel surfaces, or on suspended particles like SiO₂ [20]. These surfaces act as catalysts, significantly lowering the energy barrier for nucleation, which means scaling can initiate at lower levels of supersaturation compared to homogeneous nucleation [20].

The following diagram illustrates the pathway of scale formation from solution to deposition.

How do solid impurities in my solution affect scale formation?

Solid impurities, such as suspended silica (SiO₂) particles, corrosion products, or dirt, can significantly accelerate scale formation [20]. They act as seeds for heterogeneous nucleation, providing active sites for scale-forming crystals to grow [20]. Research has shown that the presence of SiO₂ particles can increase the deposition rate of CaCO₃ by over 13% by reducing the energy barrier for nucleation [20]. Furthermore, these particles can also reduce the efficiency of chemical scale inhibitors by adsorbing the inhibitor or providing additional nucleation sites that are difficult for the inhibitor to fully cover [20].

What are the most effective chemical strategies for preventing scale formation?

Effective scale control relies on chemicals that interfere with the nucleation and crystal growth processes at substoichiometric levels, known as threshold inhibition [9].

- Crystal Growth Inhibition: Scale inhibitors like phosphonates and low molecular weight acrylate polymers adsorb onto the active growth sites of microcrystallites. This blocks further growth and causes crystal lattice distortion, resulting in soft, non-adherent crystals instead of hard scale [9] [16].

- Dispersion: These same polymers can also impart an electrostatic charge to scale particles, causing them to repel each other and remain suspended in the solution, preventing them from agglomerating and depositing on surfaces [9] [16].

- Sequestration/Chelation: Chemicals like ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) can form soluble complexes with scale-forming cations (e.g., Ca²⁺). This approach requires stoichiometric quantities and is more practical for systems with lower hardness [9].

Troubleshooting Common Scaling Problems

| Problem Observed | Possible Cause | Investigative Steps & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid scale formation in a beaker experiment | High supersaturation leading to homogeneous nucleation. | 1. Quantify saturation using indices (e.g., LSI for CaCO₃) [18].2. Dilute the solution or adjust pH to lower supersaturation.3. Introduce a threshold inhibitor (e.g., 1-10 ppm phosphonate or polymer). |

| Scale forms only on heated surfaces | Retrograde solubility of salts like CaCO₃. The local temperature at the surface is higher, lowering solubility. [9] [18] | 1. Verify that bulk water chemistry is sub-saturated at the surface temperature, not the bulk temperature.2. Apply a scale inhibitor that performs well at higher temperatures. |

| Scale forms despite using an inhibitor | 1. Inhibitor dosage is too low for the level of supersaturation.2. Presence of solid particles (e.g., silt, Fe(OH)₃) facilitating heterogeneous nucleation [20].3. Inhibitor is not effective for the specific scaling salt. | 1. Test inhibitor efficiency at higher dosages.2. Filter the solution to remove particulates.3. Re-evaluate inhibitor selection; e.g., barium sulfate is inert to acid and many chelants [15]. |

| Hard, acid-insoluble scale on equipment | Likely calcium sulfate or silica scale [19] [17]. | 1. For silica, investigate cleaners like gallic acid, which can form soluble complexes with silica, showing high removal efficiency [19].2. For calcium sulfate, prevention is key, as removal is extremely difficult. |

Quantitative Solubility Data for Common Scaling Salts

The table below provides a comparative overview of the solubility of common scales, which is fundamental for predicting scaling potential.

Table 1: Comparative Solubilities of Common Scaling Salts in Distilled Water at 77°F (25°C) [15]

| Scale Type | Chemical Formula | Solubility (mg/L) | Key Solubility Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barium Sulfate | BaSO₄ | 2.3 | Least soluble common salt; solubility increases with TDS and temperature [15]. |

| Calcium Carbonate | CaCO₃ | 53 | Solubility decreases with increasing temperature (retrograde) [15] [18]. |

| Calcium Sulfate (Gypsum) | CaSO₄·2H₂O | 2080 | Solubility increases up to ~100°F (38°C), then decreases [15]. |

TDS = Total Dissolved Solids

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Scale Inhibitor Efficiency

This protocol outlines a standard jar test to assess the performance of chemical inhibitors against calcium carbonate scaling.

Principle: A supersaturated calcium carbonate solution is prepared and held in a controlled environment. The time until the first appearance of a precipitate (turbidity) is measured both with and without inhibitor. An effective inhibitor will significantly delay the onset of precipitation.

Materials & Reagents:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Calcium chloride solution (CaCl₂, e.g., 0.1M)

- Sodium bicarbonate solution (NaHCO₃, e.g., 0.1M)

- Scale inhibitor stock solution (e.g., a phosphonate or polyacrylate at 1000 ppm)

- Deionized water

- Equipment:

- Thermostatic water bath

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

- Multiple beakers (e.g., 500 mL)

- Graduated cylinders and pipettes

- pH meter

- Nephelometer or spectrophotometer for measuring turbidity.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a working solution that, when mixed, will yield a supersaturated CaCO₃ solution. For example, add calculated volumes of CaCl₂ and NaHCO₃ stock solutions to a beaker containing DI water to achieve desired initial concentrations (e.g., 400 ppm Ca²⁺ and 800 ppm HCO₃⁻ is a common starting point).

- pH Adjustment: Adjust the solution pH to the target value (e.g., 8.5-9.0) using a small volume of NaOH or HCl.

- Inhibitor Addition: To the test beakers, add the scale inhibitor at the desired concentration (e.g., 1, 5, 10 ppm). Prepare a control beaker with no inhibitor.

- Induction Time Measurement: Place all beakers in a thermostatic bath set at the test temperature (e.g., 50°C or 120°F). Maintain constant, gentle agitation.

- Monitoring: Continuously monitor and record the solution turbidity and pH over time. The "induction time" is the period from the start of the experiment until a sustained increase in turbidity is observed.

- Analysis: Compare the induction time of the inhibited samples to the control. A longer induction time indicates better inhibitor performance. The efficiency can be calculated as:

Inhibition Efficiency (%) = [(T_inhibited - T_control) / T_control] * 100, where T is the induction time.

Research Reagent Solutions for Scaling Studies

Table 2: Key Reagents for Scale Inhibition and Cleaning Research

| Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphonates (e.g., HEDP, ATMP) | Threshold inhibitor; adsorbs onto crystal growth sites, distorting crystal shape and preventing growth [9]. | Controlling calcium carbonate and sulfate scale in recirculating water systems. |

| Polyacrylates & Polyspartates | Dual-function: threshold inhibitor and dispersant; inhibits scale and suspends particulates via electrostatic repulsion [9] [16]. | Inhibiting calcium phosphate and dispersing iron oxides in cooling water. |

| Gallic Acid | Natural polyphenolic cleaner; adsorbs onto silica particles to form a surface complex, facilitating dissolution and removal [19]. | Cleaning silica-scaled reverse osmosis membranes. |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Chelating agent; forms stable, water-soluble complexes with di- and trivalent metal ions (e.g., Ca²⁺, Ba²⁺) [9]. | Stoichiometric removal of scale-forming cations in lab-scale or low-hardness systems. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Dissolves acid-soluble scales (primarily carbonates) by reacting with the carbonate anion [17]. | Cleaning CaCO₃ scale from laboratory equipment. (Ineffective on sulfate scales [17]) |

Visualizing the Two-Stage Nucleation Pathway

Advanced research, including molecular dynamics simulations, suggests that nucleation in some systems may follow a two-stage pathway, which is a key concept in modern crystallization research [21].

Homogeneous Nucleation in Bulk Solution vs. Surface Scaling

FAQs: Understanding Nucleation Mechanisms

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation in the context of scale formation?

- A1: Homogeneous nucleation is the spontaneous formation of crystal nuclei randomly within the bulk solution itself, requiring a high energy barrier. In contrast, heterogeneous nucleation occurs on pre-existing surfaces (like membrane walls, container surfaces, or impurities), which significantly lowers the energy required for nucleation.

- Theoretical Basis: The free energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation (ΔGhet) is a fraction of that for homogeneous nucleation (ΔGhom), as described by the contact angle (θ) between the forming crystal and the surface: ΔGhet = f(θ) ΔGhom*, where f(θ) = (2 - 3cosθ + cos³θ)/4 [12]. Surfaces thereby act as catalysts for nucleation.

- Practical Implication: Highly soluble salts (e.g., sodium sulfate) with low interfacial energy often favor heterogeneous nucleation on surfaces, leading to scaling. Less soluble salts (e.g., calcium sulfate) with high interfacial energy may require a high supersaturation threshold to nucleate, at which point homogeneous nucleation in the bulk can become dominant, paradoxically mitigating surface scale [22].

Q2: How can I actively promote homogeneous nucleation in the bulk to prevent surface scaling on my equipment?

- A2: Shifting nucleation from surfaces to the bulk solution is a key scaling mitigation strategy. This can be achieved by:

- Elevating Supersaturation: Increasing the supersaturation rate in the bulk solution provides more volume free energy, reducing the critical energy requirement for nucleation and favoring a homogeneous primary nucleation mechanism [4].

- Using Electromagnetic Fields (EMF): EMF treatment is a chemical-free method that promotes bulk (homogeneous) nucleation. It alters crystallization dynamics, leading to the formation of less adherent, porous scale structures in the bulk that are easier to remove, rather than hard scale on surfaces [23].

- Employing Functional Spacers: Incorporating materials like carbon nanotube (CNT) spacers can delay crystal adhesion and promote the growth of larger crystals in the bulk, effectively acting as a site for cooling crystallization that draws nucleation away from critical surfaces [24].

Q3: Why do I observe inconsistent results when using Electromagnetic Field (EMF) devices to control scaling?

- A3: The performance of EMF devices is highly application-specific and depends on the precise optimization of several parameters. Inconsistencies often arise from variations in [23]:

- Water Chemistry: Ionic composition, pH, and the saturation index of the scaling minerals (e.g., CaCO₃, gypsum, silica).

- Operational Parameters: Flow velocity, exposure time, and temperature.

- EMF Device Configuration: Field intensity, frequency, and waveform (e.g., sine vs. square wave). For example, in AC-induced EMF devices, the electric field is the dominant component, not the magnetic field, and square waveforms often outperform sine waves [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Recurrent Membrane Scaling

Symptoms: Rapid flux decline, increased pressure drop, and visible crystal layers on membrane surfaces.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Predominant Heterogeneous Nucleation | Analyze feedwater solubility and saturation index. Highly soluble salts indicate a tendency for surface scaling [22]. | Increase bulk supersaturation rate to shift nucleation mechanism to homogeneous. Consider combining EMF with low-dose antiscalants [23] [4]. |

| Suboptimal Hydrodynamics | Inspect for "dead zones" or areas of low flow near spacer-membrane interfaces. | Use engineered spacers (e.g., 3D-printed CNT spacers) that enhance flow mixing and reduce concentration polarization [24]. |

| Insufficient Pretreatment | Review pretreatment logs and feedwater quality. | Implement or optimize pretreatment (e.g., ultrafiltration) to remove heterogeneous nucleation catalysts like impurities [24]. |

Problem: Uncontrolled Bulk Crystallization

Symptoms: Excessive particle formation in the bulk solution, leading to slurry handling issues or unwanted particulate contamination.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Supersaturation | Monitor supersaturation rate and induction time. A very short induction time indicates rapid nucleation. | Modulate parameters that control supersaturation rate, such as crystallizer volume or temperature difference, to broaden the Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) and gain better control [4]. |

| Incorrect Antiscalant Selection | Evaluate if current antiscalants are promoting bulk precipitation. | Select antiscalants that specifically inhibit crystal growth or modify crystal morphology without excessively promoting bulk nucleation. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Comparison of Nucleation Types

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation

| Parameter | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleation Location | Bulk solution [6] | On surfaces (membranes, walls, impurities) [22] |

| Energy Barrier (ΔG*) | High [12] [1] | Significantly Lower (ΔGhet = f(θ)ΔGhom) [12] |

| Critical Supersaturation | High | Low |

| Resulting Scale Adhesion | Loosely adhered crystals/particles [23] | Compact, strongly adherent layers [23] [22] |

| Dominant Scaling Control | EMF, high supersaturation rate [23] [4] | Surface modification, antiscalants, hydrodynamics [24] |

Table 2: Performance of Scaling Mitigation Technologies

| Mitigation Technology | Scaling Reduction | Key Operational Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Electromagnetic Field (EMF) | ∼15–79% in bench tests; ∼40–45% in pilot studies [23] | Field intensity, frequency, waveform (square wave preferred), flow velocity [23] |

| 3D-printed CNT Spacer | Maintained 41% flux reduction at VCF 5.0+; delayed crystal adhesion [24] | Nanoscale roughness, nanochannels that strengthen hydrogen bonding [24] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: EMF for Scaling Mitigation

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of an Electromagnetic Field (EMF) device in mitigating CaCO₃ scaling by promoting homogeneous nucleation.

Materials:

- EMF Device: Custom-built with adjustable field strength, frequency, and waveform.

- Test Solution: Synthetic solution with defined CaCO₃ scaling potential.

- Monitoring Equipment: pH and conductivity meters.

- Analysis Software: COMSOL Multiphysics for EMF distribution simulation.

Methodology [23]:

- Setup: Install the EMF device in-line with a recirculating flow system containing the test solution.

- Parameter Calibration: Set EMF operational parameters (e.g., field intensity ~0.1 Tesla, frequency ~1-10 kHz, square waveform).

- Simulation: Use COMSOL to model and verify the EMF field distribution within the test section.

- Induction & Monitoring: Induce scaling conditions (e.g., by heating or chemical addition). Continuously monitor solution pH and conductivity as indicators of crystallization onset and progression.

- Sampling & Analysis: Periodically collect solution samples and inspect surfaces.

- Analyze bulk particles for count and size (e.g., via microscopy).

- Examine test surfaces for scale mass and adhesion strength.

- Comparison: Compare the results against a control experiment run under identical conditions without EMF activation.

Diagrams and Workflows

Nucleation Pathways and Scaling Outcomes

Experimental Workflow for EMF Scaling Control

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nucleation and Scaling Control Experiments

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Custom EMF Device | Core component for chemical-free scale control by altering ion behavior and promoting bulk precipitation [23]. |

| COMSOL Multiphysics Software | For high-fidelity simulation of EMF field distribution and optimization of device parameters [23]. |

| 3D-Printed CNT Spacer | A functional spacer that induces cooling crystallization, delays scale adhesion, and promotes larger, less adherent bulk crystals [24]. |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Membrane | A common membrane material used in distillation and filtration studies to evaluate surface scaling phenomena [24]. |

| Sodium Sulfate (Na₂SO₄) | A model solute for cooling crystallization studies due to its strong temperature-dependent solubility, useful for clear observation of nucleation effects [24]. |

| Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) Model | A foundational theoretical framework for quantitatively studying nucleation kinetics, despite known limitations at high supersaturations [12] [25]. |

Molecular Dynamics Insights into Nucleation Kinetics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the role of molecular dynamics in understanding nucleation kinetics? Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a computational microscope, allowing researchers to directly observe and quantify the atomic-scale process of nucleation, which is often difficult to capture experimentally. MD tracks the time-dependent trajectory of atoms, enabling the study of fundamental events like the birth and spreading of two-dimensional (2D) nuclei on a crystal facet or the formation of critical clusters in a homogeneous liquid. This provides unique insights into the energy barriers and atomic mechanisms that control nucleation rates [26] [27].

2. How can MD simulations help prevent homogeneous nucleation in bulk solutions? In the context of preventing scaling, MD simulations can identify how different chemical additives or impurities in a bulk solution either promote or inhibit the homogeneous nucleation of scale-forming minerals. By simulating systems with varying compositions, researchers can pinpoint elements that significantly increase the energy barrier for nucleation. For instance, studies on iron-rich systems have shown that certain elements like carbon can drastically reduce the required supercooling for nucleation, thereby potentially delaying or preventing the onset of scaling phenomena [28].

3. What are common pitfalls when calculating nucleation rates from MD simulations? A major challenge is achieving steady-state nucleation rates, as high cooling rates can lead to unsteady nucleation where cluster sizes do not have time to relax at a given temperature. Furthermore, the use of relatively small system sizes and idealized interatomic potentials means that simulations often provide qualitative comparisons with experiments. It is crucial to ensure that nucleation times are larger than the typical relaxation time of the supercooled liquid to obtain valid, steady-state rates [26].

4. How do I choose an appropriate interatomic potential for nucleation studies? The choice of interatomic potential is critical as it determines the accuracy of the calculated forces between atoms. For silicon, the Stillinger-Weber potential is commonly used as it describes two-body and three-body interactions essential for modeling diamond-cubic structures. A key trend is the use of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs), which are trained on high-accuracy quantum chemistry data. These MLIPs promise to combine high precision with computational efficiency for complex material systems [26] [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unphysical Nucleation Rates at High Undercooling

Problem Simulated nucleation rates are excessively high at large undercoolings (ΔT), or the system undergoes kinetic roughening instead of layered faceted growth.

Solution

- Verify Interfacial Undercooling: Ensure the reported undercooling is accurate and controlled. The forced-velocity solidification (FVS) method can provide better control over the interface temperature compared to simple quenching [26].

- Check for Kinetic Roughening: At high undercooling, a transition from faceted to non-faceted growth can occur. Monitor the interface structure using common neighbor analysis (CNA). If kinetic roughening is observed, the model for layered growth may no longer be valid [26].

- Validate with Theory: Compare your MD-derived nucleation rates with Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT). The nucleation rate (J) is an exponential function of the inverse undercooling: ( J = A \exp\left(-\frac{\pi \lambda^2}{kB T \rho{2D} L_f \Delta T}\right) ), where A is a pre-exponential factor and λ is the line tension. Significant deviations may indicate issues with the potential or system size [26].

Issue 2: Inaccurate Diffusion Coefficients Affecting Nucleation

Problem The mobility of ions or molecules in the bulk solution, which directly influences nucleation, does not match experimental values.

Solution

- Calculate Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): Use the trajectory data to compute the MSD, defined as the average of the squared displacement of particles over time.

- Extract Diffusion Coefficient (D): In the diffusive regime where MSD increases linearly with time, calculate D using Einstein's relation for a 3D system: ( D = \frac{1}{6} \frac{d(MSD)}{dt} ) [27].

- Benchmark with Pure Systems: Validate your simulation setup and analysis protocol by calculating the diffusion coefficient for a well-characterized system (e.g., SPC water model) before introducing additives or impurities.

Issue 3: System Size and Finite-Size Effects

Problem The critical nucleus size is comparable to the simulation box size, leading to finite-size artifacts and unreliable nucleation statistics.

Solution

- Perform a Size Convergence Test: Repeat the nucleation experiment with progressively larger system sizes (number of atoms) while keeping other conditions constant.

- Monitor Nucleus Size: Use cluster analysis tools to estimate the average critical nucleus size. A good rule of thumb is that the simulation box should be at least twice the size of the largest critical nucleus observed.

- Consider Advanced Sampling Methods: For systems where large-scale MD is prohibitive, enhanced sampling techniques like metadynamics can be used to probe nucleation events more efficiently.

Quantitative Data on Nucleation Kinetics

The following table summarizes key quantitative relationships and parameters for nucleation kinetics derived from MD simulations, as highlighted in the search results.

| Parameter | Mathematical Relation | MD-Derived Insight | Relevance to Scaling Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Nucleation Rate (J) | ( J = A \exp\left(-\frac{\pi \lambda^2}{kB T \rho{2D} L_f \Delta T}\right) ) [26] | MD can provide semi-quantitative values for the pre-exponential factor (A) and nucleation energy barrier, which may differ from Monte Carlo models [26]. | Determines the rate of new layer formation on crystal facets, directly influencing scale growth speed. |

| Homogeneous Nucleation Undercooling (ΔT) | N/A | The "inner core nucleation paradox" requires ~1000K undercooling for pure Fe, but additives can change this. 3 mol.% C reduces required ΔT to ~612 K [28]. | Identifies chemical additives that maximize the undercooling required for scale mineral nucleation, effectively suppressing it. |

| Diffusion Coefficient (D) | ( D = \frac{1}{6} \frac{d\langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle}{dt} ) [27] | Calculated from the slope of the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) vs. time plot. Essential for validating atomic mobility in the solution [27]. | Controls the transport of scaling ions to the nucleation site; lower diffusion can slow down nucleation kinetics. |

Experimental Protocols for Key MD Simulations

Protocol 1: Forced-Velocity Solidification (FVS) for Facet Growth

Objective: To determine the 2D nucleation kinetic coefficient for a faceted crystal growing from an undercooled melt [26].

Methodology:

- Initial Structure Preparation: Create a simulation cell containing a solid seed of the crystal (e.g., Si (1 1 1) facet) in contact with its liquid melt.

- Simulation Setup: Use an interatomic potential suitable for the material (e.g., Stillinger-Weber for Si). Apply periodic boundary conditions.

- Apply Forced Velocity: Impose a constant velocity on the solid seed in the direction of growth, effectively simulating a pulling rate.

- Thermostatting: Maintain the bulk liquid at a constant undercooling (ΔT) using a thermostat.

- Trajectory Analysis: Use Common Neighbor Analysis (CNA) to distinguish solid and liquid atoms and visualize the formation and spreading of 2D nuclei on the facet.

- Data Extraction: Quantify the nucleation rate (J) as a function of undercooling by counting nucleation events per unit area and time from the trajectory.

Protocol 2: Homogeneous Nucleation in Bulk Solutions

Objective: To characterize the effect of solute additives on the homogeneous nucleation barrier of a scaling mineral.

Methodology:

- System Construction: Build a simulation box containing a large number of solvent and solute molecules (e.g., water and ions), including the target additive (e.g., C, O, S, Si).

- Equilibration: First, equilibrate the system in the liquid phase at a temperature above the melting point.

- Quenching: Rapidly quench the system to a series of target undercoolings below the melting point.

- Production Run: Perform long MD runs to observe spontaneous nucleation events.

- Cluster Analysis: Employ a clustering algorithm (e.g., based on a bond-order parameter) to identify and track the size of solid-like clusters over time.

- Free Energy Barrier: Use the mean first-passage time method or umbrella sampling to compute the free energy barrier as a function of cluster size and undercooling.

- Comparative Analysis: Repeat the process for different additives and concentrations to quantify their impact on the nucleation barrier.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The table below lists key computational "reagents" and tools used in MD simulations of nucleation kinetics.

| Item / Software / Potential | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) | A highly versatile and widely used open-source MD simulation software package for performing the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion [26]. |

| Stillinger-Weber (SW) Potential | An empirical interatomic potential that includes both two-body and three-body terms; commonly used for simulating silicon and other materials with directional bonding [26]. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | A new class of potentials trained on quantum mechanics data, offering near-quantum accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling more reliable simulations of complex systems [27]. |

| OVITO (Open Visualiization Tool) | A scientific visualization and analysis software for atomistic simulation data. It is used for tasks like Common Neighbor Analysis (CNA) to identify crystal structures and defects [26]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

MD Nucleation Analysis Workflow

Homogeneous Nucleation Pathway

Intervention Strategies: Chemical-Free Technologies and Process Control

Electromagnetic Field (EMF) treatment presents a promising, non-chemical approach for controlling mineral scaling in water systems. For researchers investigating the prevention of homogeneous nucleation and bulk solution scaling, understanding EMF mechanisms is crucial. This technology is valued for its cost-effectiveness, environmental sustainability, and low energy consumption, offering an alternative to traditional chemical antiscalants that can pose ecological risks [29] [23]. This technical support guide addresses common experimental challenges and details the fundamental principles of EMF application in scaling control.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary mechanism by which EMF treatment controls scaling? EMF treatment primarily mitigates scaling by altering crystallization pathways. It promotes homogeneous nucleation in the bulk solution over heterogeneous nucleation on surfaces. This results in the formation of less adherent, softer scale crystals (such as aragonite instead of calcite) that are more easily removed by hydraulic flushing [29] [23] [30]. The specific mechanisms include the magnetohydrodynamic effect, which influences ion motion, and the hydration effect, which can disrupt ion hydration shells [23].

2. Why does EMF effectiveness vary significantly between experiments? Performance variability is often due to key operational conditions. EMF exhibits greater efficacy in treating near-saturated water (Saturation Index, SI ~ 0). In supersaturated solutions, the technology can sometimes accelerate flux decline by promoting excessive bulk precipitation that blocks membrane pores or system flow paths [29]. Other influencing factors include feedwater chemistry (e.g., presence of Mg²⁺ can improve outcomes), flow velocity, field intensity, frequency, and waveform [29] [23] [30].

3. What are the critical parameters for designing a reproducible EMF experiment? For reproducible results, carefully control and document these parameters:

- Field Intensity: Typically between 0.1 mT and 30 mT for low-frequency applications [31] [23].

- Frequency: Low frequencies (e.g., 1 Hz to 100 Hz) are commonly used [31].

- Waveform: Asymmetrical or pulsed waveforms (e.g., triangular, sinusoidal) are often more effective than symmetrical ones [32] [23].

- Exposure Time/Flow Rate: Sufficient exposure time and flow velocity (e.g., ≥ 2 m/s) are needed to ensure treatment efficacy and self-cleaning [23] [33].

- Water Chemistry: Monitor and report ionic composition, pH, and saturation indices (e.g., for CaCO₃, CaSO₄, silica) [29] [30].

4. My EMF treatment shows no measurable improvement in scaling control. What could be wrong? First, verify the saturation state of your feed solution. EMF may have negligible effects on already supersaturated solutions where rapid homogeneous scaling is dominant [29]. Second, check device operation and placement. Ensure the EMF device is functional, correctly positioned (pre-treatment or co-treatment), and that the specified field parameters are being delivered to the target water [30]. Finally, confirm your characterization methods; use a combination of techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and permeability tests to fully assess crystal morphology, type, and system performance [29] [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Results in Scaling Mitigation

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Uncontrolled or unmeasured variations in feedwater chemistry.

- Cause: Inconsistent EMF field application due to device or power instability.

- Solution: Calibrate the EMF generator regularly. Use a gaussmeter to verify the magnetic field strength at the point of application. Ensure a stable power supply [23].

- Cause: Inadequate replication of hydrodynamic conditions.

- Solution: Maintain a consistent and documented flow velocity across experiments. Use flow meters and ensure pump performance is stable [33].

Problem 2: Accelerated System Fouling After EMF Implementation

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Application on highly supersaturated feedwater (high SI).

- Cause: The formed bulk crystals are too small and are depositing in narrow passages.

- Solution: Optimize EMF parameters (e.g., frequency, waveform) to promote the growth of larger, more easily removable crystals [23].

Quantitative Data on EMF Performance

The table below summarizes the range of EMF effectiveness reported across different water treatment systems.

Table 1: Reported Effectiveness of EMF Scaling Control

| System Type | Scaling Reduction Range | Key Influencing Factors | Common Scale Types Studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bench-scale Thermal/Membrane Systems [23] | ~15% to 79% | Flow velocity, temperature, field intensity | CaCO₃, Gypsum, Silica |

| Reverse Osmosis (Pilot/Field Studies) [23] | ~40% to 45% | Saturation Index, membrane type, recovery rate | CaCO₃ |

| Heat Exchangers & Water Pipes [30] | >95% of studies report positive effects (qualitative) | Pipe material, exposure time, water composition | CaCO₃ |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EMF Scaling Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Justification | Example Application/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂·2H₂O) & Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) [29] | To prepare synthetic scaling solutions with defined saturation indices for CaCO₃. | Allows for controlled, reproducible studies of the most common scale. |

| RO Membranes (e.g., ESPA2-LD) [29] | To study surface (heterogeneous) scaling in membrane-based desalination. | Provides a standard surface for evaluating scale adhesion and flux decline. |

| Brackish Groundwater [29] | For validation experiments using real water matrices with complex chemistry. | Essential for translating findings from synthetic solutions to real-world applications. |

| Antiscalants (e.g., Phosphonates) [34] | As a benchmark for performance comparison or for hybrid EMF+Chemical studies. | Compare EMF efficacy against established chemical methods. |

| Permanent Magnets & Electromagnetic Coils [23] [30] | To generate static (SMF) and alternating (EMF) fields, respectively. | Enables research into how different field types (static vs. pulsed) affect scaling. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: EMF for RO Membrane Scaling Control

This protocol is adapted from studies on brackish water reverse osmosis, focusing on preventing homogeneous nucleation to mitigate membrane fouling [29].

1. Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of EMF treatment in reducing CaCO₃ scaling on RO membranes by promoting bulk precipitation over surface crystallization.

2. Materials:

- Feed Solution: Synthetic solution prepared with CaCl₂·2H₂O and NaHCO₃ to achieve a desired saturation index (SI ~ 0 is recommended for optimal EMF effect) [29]. Alternatively, real brackish groundwater.

- EMF Device: An adjustable EMF generator capable of producing specific frequencies (e.g., 1-100 Hz) and intensities (e.g., 0.1-2.0 mT) [29] [23].

- RO Filtration Unit: A bench-scale RO system equipped with a flat-sheet or spiral-wound membrane cell (e.g., using ESPA2-LD membranes) [29].

- Analytical Equipment: Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) or similar for ion analysis, pH and conductivity meters, Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) [29] [30].

3. Workflow Diagram:

4. Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare the synthetic scaling solution by dissolving stoichiometric amounts of CaCl₂·2H₂O and NaHCO₃ in deionized water. Equilibrate the solution to the experimental temperature.

- System Setup & EMF Calibration: Install the RO membrane in the cell. Position the EMF device on the feed line or around the membrane cell. Power on the EMF generator and set the desired parameters (e.g., 15 Hz fundamental frequency, 1.19 mT amplitude). Use a gaussmeter to confirm field strength [29] [32].

- Cyclic Filtration & Flushing: Conduct the experiment in consecutive cycles.

- Filtration Cycle: Pump the feed solution through the EMF device and across the RO membrane at a constant pressure. Record the permeate flux over time.

- Flushing Cycle: After a set filtration period, stop the high-pressure pump and perform a low-pressure hydraulic flush (e.g., 5 minutes) with the permeate water or DI water to remove loosely adhered crystals from the system [29].

- Scale Characterization: After the final cycle, carefully remove the membrane.

- Data Analysis: Compare the rate of flux decline, total water recovery, and scale characteristics between the EMF-treated system and a control system operated under identical conditions but without EMF.

Mechanisms of EMF Action Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the theorized mechanisms by which EMF influences scaling pathways, favoring bulk homogeneous nucleation over surface scaling.

Supersaturation Control Through Membrane Area and Configuration

Supersaturation is the fundamental driving force in crystallization processes, representing the difference between the actual concentration of a solute and its equilibrium saturation concentration [35]. In membrane distillation crystallisation, this driving force is carefully managed to promote the formation of desired crystals while preventing operational issues like scaling. Membrane area to volume ratio has emerged as a critical parameter that allows researchers to control supersaturation rate without altering boundary layer conditions, enabling precise navigation through the metastable zone where crystallization is thermodynamically favored but kinetically limited without spontaneous nucleation [36] [37].

? Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How does membrane area to volume ratio affect supersaturation and nucleation? Increasing the membrane area to volume ratio sustains the same water vapour flux but increases the supersaturation rate within the crystallizing solution. This reduces induction time and increases the supersaturation level at which nucleation occurs. Contrary to some expectations, this approach can minimize membrane scaling despite increasing nucleation rate, which aligns with classical nucleation theory [36] [37].

What is the relationship between homogeneous nucleation and scaling? In membrane distillation crystallisation, homogeneous nucleation (which occurs spontaneously in the bulk solution without solid surfaces) typically leads to bulk crystal formation, while heterogeneous nucleation (occurring on surfaces like the membrane) contributes directly to scaling. The transition from heterogeneous to homogeneous nucleation occurs at higher supersaturation levels, and operating within appropriate parameters can shift nucleation toward the bulk solution, thereby reducing membrane scaling [36].

How can I determine if my system is experiencing homogeneous or heterogeneous nucleation? Homogeneous nucleation typically occurs at higher supersaturation levels and produces many small crystals throughout the bulk solution. Heterogeneous nucleation occurs at lower supersaturation levels and often forms crystals directly on surfaces like membranes. Monitoring induction times and supersaturation levels at nucleation can help identify the dominant mechanism, with shorter induction times and higher supersaturation at induction indicating a shift toward homogeneous nucleation [36].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Excessive Membrane Scaling

Problem: Rapid scaling formation on membrane surfaces, reducing flux and efficiency.

Solution: Increase membrane area to volume ratio to elevate supersaturation rate. This approach reduces scaling despite increasing nucleation rate, as it promotes homogeneous nucleation in the bulk solution rather than heterogeneous nucleation on membrane surfaces [36]. Ensure proper pre-treatment of feed stock and implement optimal cleaning procedures [38].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Measure induction time and supersaturation level at nucleation

- Analyze scaling deposit composition and morphology

- Check membrane configuration and area to volume parameters

Poor Crystal Size Distribution

Problem: Inconsistent crystal size or undesirable morphology affecting downstream processing and product quality.

Solution: Optimize membrane configuration to control supersaturation profile. Higher membrane area to volume ratios facilitate higher nucleation rates complemented by greater crystal growth, improving overall size distribution [36]. Implement real-time monitoring using techniques like laser backscattering or process video microscopy to track crystal size and shape changes [35].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Analyze crystal size distribution using laser diffraction or ultrasonic spectroscopy

- Review supersaturation control parameters

- Evaluate mixing efficiency and boundary layer conditions

Uncontrolled Polymorphic Transformations

Problem: Unexpected or undesired polymorphic forms appearing during crystallization, affecting drug efficacy and stability.

Solution: Carefully control supersaturation rate through membrane configuration, as different polymorphs can be favored at specific supersaturation levels. Implement in situ monitoring techniques such as ATR-FTIR or Raman spectroscopy to detect polymorphic transitions in real-time [35] [39].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Characterize polymorphs using X-ray diffraction or thermal analysis

- Monitor solution concentration and supersaturation in real-time

- Review cooling or antisolvent addition profiles

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Metastable Zone Width

Objective: Determine the metastable zone width for your specific system to define safe operating parameters that avoid uncontrolled nucleation.

Materials:

- Membrane distillation crystallisation system with adjustable configuration

- Temperature and concentration monitoring equipment

- Laser backscattering device (e.g., FBRM) for nucleation detection

Procedure:

- Prepare saturated solution of your solute at constant temperature

- Gradually increase supersaturation through controlled cooling or solvent evaporation

- Monitor solution continuously for first signs of nucleation

- Record the supersaturation level at which nucleation occurs

- Repeat experiments at different membrane area to volume ratios

- Plot supersaturation against membrane configuration to establish operating boundaries

Expected Outcomes: Determination of safe operating zone between solubility curve and metastable limit for your specific membrane configuration [35].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Membrane Configuration for Scaling Reduction

Objective: Identify optimal membrane area to volume ratio to minimize scaling while maintaining crystal quality.

Materials:

- Modular membrane system with adjustable area to volume ratios

- Supersaturation monitoring equipment (e.g., ATR-FTIR spectroscopy)

- Scaling deposition analysis tools

Procedure:

- Set up membrane system with measurable area to volume ratio

- Conduct crystallization runs at constant supersaturation driving force

- Measure induction times for each configuration

- Quantify scaling accumulation on membranes after set time periods

- Analyze crystal products for size, morphology, and polymorphic form

- Correlate membrane configuration with scaling propensity and product quality

Expected Outcomes: Identification of membrane area to volume ratio that minimizes scaling while producing desired crystal characteristics [36] [37].

Table 1: Membrane Configuration Effects on Crystallization Parameters

| Membrane Area:Volume Ratio | Induction Time | Supersaturation at Induction | Nucleation Rate | Scaling Propensity | Dominant Nucleation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Long | Low | Low | High | Heterogeneous |

| Medium | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Mixed |

| High | Short | High | High | Low | Homogeneous |

Data derived from sodium chloride crystallization studies in membrane distillation crystallisation [36] [37].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Hollow Fiber Membranes | Provide high surface area for controlled supersaturation generation | Membrane distillation crystallisation [36] |

| ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy | In situ concentration and supersaturation monitoring | Real-time solution analysis [35] |

| Laser Backscattering Device | Detection of nucleation events and crystal size distribution monitoring | Chord length distribution measurement [35] |

| Sodium Chloride Solutions | Model system for crystallization mechanism studies | Fundamental nucleation studies [36] |

| Mineral Dust INPs | Ice-nucleating particles for heterogeneous nucleation studies | Atmospheric cirrus cloud analog studies [40] |

Methodology for Key Experiments