Strategies for Optimizing Computational Efficiency in AI-Driven Materials Generation

This article addresses the critical challenge of computational efficiency in the AI-driven generation of novel materials, a pivotal concern for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategies for Optimizing Computational Efficiency in AI-Driven Materials Generation

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of computational efficiency in the AI-driven generation of novel materials, a pivotal concern for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational computational paradigms, details cutting-edge methodological approaches like high-throughput computing and generative AI, and provides practical troubleshooting strategies for managing resource constraints. Furthermore, it establishes a framework for the rigorous validation and benchmarking of generated materials, synthesizing key insights to accelerate the discovery of functional materials for biomedical and clinical applications.

The Computational Bottleneck: Understanding the Foundations of Efficiency in Materials Science

This section outlines the fundamental hardware and service components that power computational materials research and describes the common performance limitations you may encounter.

CPU Architectural Bottlenecks in Parallel Processing

In high-performance computing (HPC) for materials science, CPU performance is often limited by factors other than raw processor speed. Understanding these bottlenecks is crucial for efficient resource utilization [1].

Table: Major CPU Performance Bottlenecks in HPC Workloads [1]

| Bottleneck Category | Description | Impact on Parallel Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Access Latency | Time to fetch data from main memory (hundreds of cycles). Caches help but introduce coherency overhead. | Multiple threads issuing requests can overlap access times, but coherency protocols (e.g., MESI) can cause delays of ~1000 cycles in many-core systems. |

| Synchronization Overhead | Delays from data dependencies between threads, requiring locks (mutexes) or barriers. | Managing locks or waiting at barriers for all threads to finish can halt execution. Implementation via interrupts (slow) or busy polling (power-inefficient) adds cost. |

| Instruction-Level Parallelism Limits | Constraints on how many instructions a CPU can execute simultaneously. | Superscalar architectures enable some parallel execution, but inherent data dependencies in code limit the achievable parallelism. |

Cloud Service Pricing Models for Research

Cloud computing offers flexible, on-demand resources, but its cost structure is complex. Selecting the right pricing model is essential for budget management [2].

Table: Comparing Cloud Pricing Models for Computational Research [2]

| Pricing Model | Best For | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pay-As-You-Go (On-Demand) | Unpredictable, variable workloads; short-term experiments. | High flexibility; no long-term commitment; suitable for bursting. | Highest unit cost; not cost-efficient for steady, long-running workloads. |

| Spot Instances | Fault-tolerant, interruptible batch jobs (e.g., some molecular dynamics simulations). | Extreme discounts (60-90% off on-demand); good for massive parallelization. | No availability guarantee; can be terminated with little warning. |

| Reserved Instances | Stable, predictable baseline workloads (e.g., a constantly running database). | Significant savings (upfront commitment for 1-3 years); predictable billing. | Inflexible; risk of over-provisioning if project needs change. |

| Savings Plans | Organizations with consistent long-term cloud usage across various services. | Flexible across services and instance families; good balance of savings and agility. | Requires accurate usage forecasting; over-commitment reduces value. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My molecular dynamics simulation is running much slower than expected. What are the first things I should check?

A1: First, check for CPU and memory utilization. High CPU usage with low memory usage may suggest your problem is compute-bound. Conversely, low CPU usage could indicate a memory bottleneck or that the process is waiting for I/O (input/output operations). Use monitoring tools like htop or nvidia-smi (for GPU workloads) to diagnose this. Second, verify that your software is built to leverage parallel processing and that you have allocated an appropriate number of CPU cores [1].

Q2: How can I reduce cloud costs for my long-running density functional theory (DFT) calculations without sacrificing performance? A2: A hybrid approach is often most effective [2] [3]. Use Reserved Instances or Savings Plans for your stable, baseline compute needs. For scalable, non-critical parts of the workflow, use Spot Instances to achieve cost savings of 60-90%. Always right-size your instances; choose a compute instance that matches your application's specific requirements for CPU, memory, and GPU, avoiding over-provisioned resources [3].

Q3: What does "cache coherency" mean, and why does it impact my multi-core simulation? A3: In a multi-core system, each core often has a private cache (e.g., L1/L2) to speed up memory access. Cache coherency protocols (like MESI) ensure that all cores have a consistent view of shared data. When one core modifies a data value held in multiple caches, the system must invalidate or update all other copies. This coordination generates communication overhead across the cores, which can cost thousands of cycles in large systems and significantly slow down parallel performance [1].

Q4: I keep getting surprising cloud bills. What strategies can I implement for better cost control? A4: Implement a multi-layered strategy [3]:

- Tagging and Allocation: Enforce a strict tagging policy for all cloud resources. This allows you to attribute costs to specific projects, teams, or experiments, creating accountability.

- Budget Alerts: Use cloud-native tools (e.g., AWS Budgets) to set up budgets and receive real-time alerts when spending exceeds thresholds.

- Eliminate Waste: Regularly scan for and terminate idle resources (e.g., unattached storage volumes, stopped virtual machines). Schedule non-production environments (dev, test) to run only during working hours.

- Anomaly Detection: Leverage machine learning-based cost anomaly detection tools to automatically flag unexpected spikes in spending for immediate investigation.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Simulation Hangs or Slows Down Dramatically at Scale

- Symptoms: Application runs fine on a few cores but hangs or becomes extremely slow when scaled to hundreds of cores.

- Potential Cause: This is often a classic sign of synchronization overhead or memory contention. As the number of parallel threads increases, the time spent waiting at barriers or managing locks on shared data can dominate the actual computation time [1].

- Resolution Steps:

- Profile Your Code: Use profiling tools (e.g.,

gprof,vtune) to identify hotspots and synchronization points. - Reduce Synchronization: Rework your algorithm to minimize the frequency of global barriers and use finer-grained locks or lock-free data structures where possible.

- Improve Data Locality: Restructure data access patterns so that data used by a single thread is located close together in memory, reducing the need for cache coherency traffic.

- Profile Your Code: Use profiling tools (e.g.,

Issue: Cloud Job is Interrupted (Especially with Spot Instances)

- Symptoms: A computation job terminates prematurely without a code error.

- Potential Cause: If using Spot Instances, this is expected behavior; the cloud provider reclaims the instances with short notice [2].

- Resolution Steps:

- Design for Fault Tolerance: Implement checkpointing in your application. This means the simulation periodically saves its state to persistent storage.

- Automated Restart: If a job is interrupted, your workflow system should automatically detect the failure and restart the job from the last saved checkpoint, using a new instance.

- Use Mixed Instance Types: When requesting Spot Instances, specify multiple instance types and across multiple Availability Zones to increase the pool of possible capacity and reduce the chance of simultaneous revocation.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Workflow for AI-Driven Materials Discovery and Validation

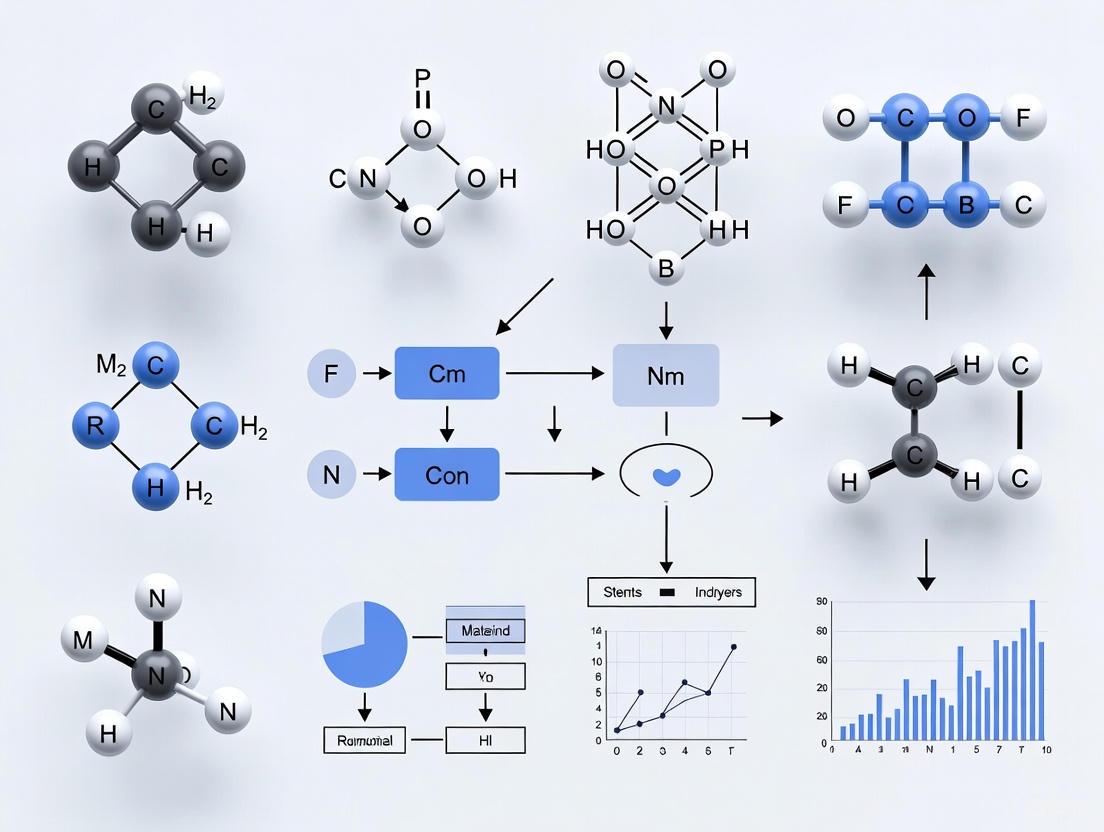

The following diagram illustrates a modern, computationally intensive workflow for generating and validating new materials, as demonstrated by tools like MIT's SCIGEN [4]. This workflow integrates high-performance computing and AI.

AI-Driven Materials Discovery Workflow

Detailed Methodology for AI-Driven Discovery [4]:

- Problem Formulation: The process begins by defining the target material properties. In the case of quantum materials, this involves specifying desired geometric constraints, such as a Kagome or Lieb lattice, which are known to host exotic electronic phenomena [4].

- Constrained Generation: A generative AI model (e.g., a diffusion model) is employed. A key innovation is the use of a constraint tool like SCIGEN, which steers the AI at every generation step to only produce crystal structures that adhere to the user-defined geometry. This ensures all outputs are relevant to the research goal.

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening: The AI generates a vast pool of candidate structures (e.g., 10+ million). This pool is then filtered for stability using computational methods, drastically narrowing the field to a more manageable number (e.g., 1 million). A subset of these stable candidates (e.g., 26,000) undergoes more detailed property simulation, often using Density Functional Theory (DFT) on supercomputers to predict behaviors like magnetism.

- Experimental Validation: The final and critical step is the synthesis and laboratory testing of the most promising candidates (e.g., TiPdBi and TiPbSb). This validates the AI's predictions and confirms the material's real-world properties.

The Scientist's Computational Toolkit

Table: Essential Computational "Reagents" for Materials Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Role in the Discovery Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Generative AI Models (DiffCSP) | Creates novel, plausible crystal structures based on training data. | Serves as the "idea engine" in Step 2, proposing millions of initial candidate structures [4]. |

| Constraint Algorithms (SCIGEN) | Applies user-defined rules (e.g., geometric patterns) to steer AI generation. | Acts as a "filter" during generation in Step 2, ensuring all outputs are structurally relevant [4]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computational quantum mechanical method for simulating electronic structure. | The primary tool for virtual screening in Step 3, predicting stability and key electronic/magnetic properties [5]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A collection of interconnected computers providing massive parallel compute power. | The "laboratory bench" for Steps 2 & 3, providing the CPUs/GPUs needed for AI generation and DFT calculations [6]. |

| Cloud Compute Instances (CPU/GPU) | Virtualized, on-demand computing power accessed via the internet. | Provides flexible, scalable resources that can supplement or replace on-premise HPC clusters, crucial for all computational steps [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Data Quality and Management Issues

Problem: Model predictions are inaccurate and lack generalizability.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-representative or biased training data [7] [8] | 1. Analyze the distribution of elements, crystal systems, and sources in your dataset.2. Check for over-representation of specific material classes (e.g., oxides, metals). | 1. Actively seek and incorporate data from diverse sources, including negative experimental results [8].2. Augment datasets using symmetry-aware transformations [9]. |

| Poor data veracity and labeling errors [8] | 1. Cross-validate a data subset with high-fidelity simulations (e.g., DFT) or experiments.2. Implement automated data provenance tracking. | 1. Establish rigorous data curation pipelines with domain-expert validation [8].2. Use standardized data formats and ontologies for all entries [8]. |

Problem: Inefficient data processing slows down the discovery cycle.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High computational cost of data generation [10] [9] | 1. Profile the time and resources consumed by DFT/MD simulations.2. Evaluate the hit rate (precision) of your discovery pipeline. | 1. Integrate machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) for rapid, high-fidelity energy calculations [9].2. Adopt active learning to strategically select simulations that maximize information gain [9] [11]. |

Algorithm and Model Performance Issues

Problem: Model underperforms on complex, high-element-count materials.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model architecture lacks generalization capability [9] | 1. Test model performance on a hold-out set containing quaternary/quinary compounds.2. Check if the model can reproduce known, but unseen, stable crystals. | 1. Employ state-of-the-art Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that inherently model atomic interactions [9].2. Scale up model training using larger and more diverse datasets, following neural scaling laws [9]. |

Problem: Long experimental cycles for synthesis and characterization.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Reliance on manual, trial-and-error experimentation [10] [11] | 1. Audit the time required from candidate selection to validated result.2. Identify bottlenecks in synthesis or analysis workflows. | 1. Implement a closed-loop, autonomous discovery system like CRESt [11].2. Use robotic platforms for high-throughput synthesis and characterization, with AI planning the experiments [11] [12]. |

Computing and Deployment Issues

Problem: High-performance computing (HPC) resources are a bottleneck.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Limited access to sufficient computing power for training [7] [9] | 1. Benchmark the peak performance (Petaflops) of your computing clusters against state-of-the-art (e.g., 10,600+ Petaflops in the US) [7].2. Monitor GPU/TPU utilization during model training. | 1. Leverage cloud-based HPC resources for scalable training.2. Utilize model compression techniques (e.g., pruning, quantization) to reduce computational demands for deployment [13]. |

Problem: Difficulty deploying large AI models on resource-constrained devices.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model size and complexity are incompatible with edge devices [13] | 1. Profile the model's memory footprint and inference speed on the target device.2. Check if the device has specialized AI accelerators (NPU, VPU). | 1. Apply the "optimization triad": optimize input data, compress the model (e.g., via knowledge distillation), and use efficient inference frameworks [13].2. Design models specifically for edge deployment, considering memory, computation, and energy constraints from the outset [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our materials discovery pipeline has a low "hit rate." How can we improve the precision of finding stable materials?

A: The key is implementing scaled active learning. The GNoME framework demonstrated that iterative training on DFT-verified data drastically improves prediction precision. Their hit rate for stable materials increased from less than 6% to over 80% for structures and from 3% to 33% for compositions through six rounds of active learning [9]. Ensure your pipeline uses model uncertainty to select the most promising candidates for the next round of expensive simulations or experiments.

Q2: What is the most effective way to discover materials with more than four unique elements, a space that is notoriously difficult to search?

A: Traditional substitution-based methods struggle with high-entropy materials. The emergent generalization of large-scale graph networks is the most promising solution. Models like GNoME, trained on massive and diverse datasets, developed the ability to accurately predict stability in regions of chemical space with 5+ unique elements, even if they were underrepresented in the training data [9]. This showcases the power of data and model scaling.

Q3: How can we bridge the gap between AI-based predictions and real-world material synthesis?

A: Address this by developing AI-driven autonomous laboratories. Systems like MIT's CRESt platform integrate robotic synthesis (e.g., liquid-handling robots, carbothermal shock systems) with AI that plans experiments based on multimodal data (literature, compositions, images) [11]. This creates a closed loop where AI suggests candidates, robots create and test them, and the results feedback to refine the AI, accelerating the journey from prediction to physical realization.

Q4: We need to run AI models for real-time analysis on our lab equipment. How can we manage this with limited on-device computing power?

A: This is a prime use case for Edge AI optimization. You must optimize across three axes [13]:

- Data: Clean and compress input data from sensors.

- Model: Apply pruning and quantization to reduce your model's size and latency.

- System: Use hardware-specific acceleration frameworks (e.g., for NPUs or GPUs). This triad enables efficient AI deployment on resource-constrained devices without a constant cloud connection.

Performance Data and Benchmarks

The tables below summarize quantitative data from recent landmark studies to serve as a benchmark for your own research.

| Metric | Initial Performance | Final Performance (After Active Learning) |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Materials Discovered | ~48,000 (from previous studies) | 2.2 million (with 381,000 on the updated convex hull) |

| Prediction Error (Energy) | 21 meV/atom (on initial MP data) | 11 meV/atom (on relaxed structures) |

| Hit Rate (Structure) | < 6% | > 80% |

| Hit Rate (Composition) | < 3% | ~33% (per 100 trials with AIRSS) |

| Metric | Result |

|---|---|

| Chemistries Explored | > 900 |

| Electrochemical Tests Conducted | ~3,500 |

| Discovery Timeline | 3 months |

| Performance Improvement | 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar for a fuel cell catalyst vs. pure Pd |

| Key Achievement | Discovery of an 8-element catalyst delivering record power density with 1/4 the precious metals |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol outlines the workflow for the GNoME project, which led to the discovery of millions of novel crystals.

1. Candidate Generation: * Structural Path: Generate candidate crystals using symmetry-aware partial substitutions (SAPS) on known crystals. This creates a vast and diverse pool of candidates (e.g., over 10^9). * Compositional Path: Generate compositions using relaxed chemical rules, then create 100 random initial structures for each using ab initio random structure searching (AIRSS).

2. Model Filtration: * Train an ensemble of Graph Neural Networks (GNoME models) on existing materials data (e.g., from the Materials Project). * Use the ensemble to predict the stability (decomposition energy) of all candidates. * Filter and cluster candidates, selecting the most promising ones based on model predictions and uncertainty.

3. Energetic Validation via DFT: * Perform Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on the filtered candidates using standardized settings (e.g., in VASP). * The DFT-computed energies serve as the ground-truth verification of model predictions.

4. Iterative Active Learning: * Incorporate the newly computed DFT data (both stable and unstable outcomes) into the training set. * Retrain the GNoME models on this expanded dataset. * Repeat the cycle from Step 1. Each iteration improves model accuracy and discovery efficiency.

This protocol describes the operation of a closed-loop, autonomous system for optimizing a functional material (e.g., a fuel cell catalyst).

1. Human Researcher Input: * A researcher defines the goal in natural language (e.g., "find a catalyst for a direct formate fuel cell with high power density and lower precious metal content").

2. AI-Driven Experimental Design: * The CRESt system queries scientific literature and databases to build a knowledge base. * It uses a multi-modal model (incorporating text, composition, etc.) to suggest the first set of promising material recipes (e.g., precursor combinations).

3. Robotic Synthesis and Characterization: * A liquid-handling robot prepares the suggested recipes. * A carbothermal shock system or other automated tools perform rapid synthesis. * Automated equipment (e.g., electron microscope, electrochemical workstation) characterizes the synthesized material's structure and properties.

4. Real-Time Analysis and Computer Vision: * Cameras and visual language models monitor experiments to detect issues (e.g., pipette misplacement, sample deviation) and suggest corrections. * Performance data (e.g., power density) is fed back to the AI model.

5. Planning Next Experiments: * The AI model uses Bayesian optimization in a knowledge-embedded space, informed by both literature and new experimental data, to design the next round of experiments. * The loop (Steps 2-5) continues autonomously until a performance target is met or the search space is sufficiently explored.

Workflow and System Diagrams

Diagram Title: Active Learning Workflow for Scalable Materials Discovery

Diagram Title: Closed-Loop Autonomous Discovery System

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists key computational and physical "reagents" essential for modern, AI-driven materials science research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents & Solutions for AI-Driven Materials Science

| Item | Function & Purpose | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the "computing" power for training large-scale AI models and running high-throughput simulations (DFT, MD). | As of 2025, Brazil had 122 Petaflops of capacity vs. the US at >10,600 Petaflops [7]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Core "algorithm" for modeling materials. Excels at learning from non-Euclidean data like crystal structures, predicting energy and stability [9]. | Used in GNoME. Superior to other architectures for capturing atomic interactions. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | The computational "reagent" that provides high-fidelity, quantum-mechanical ground-truth data on material properties (e.g., energy, band gap) for training and validation [10] [9]. | Computationally expensive. Used sparingly via active learning. |

| Active Learning Framework | An intelligent "protocol" that optimizes the use of DFT by selecting the most informative candidates for calculation, dramatically improving discovery efficiency [9] [11]. | The core of the GNoME and CRESt feedback loops. |

| Autonomous Robotic Laboratory | The physical "synthesis and characterization" platform that automates the creation and testing of AI-proposed materials, closing the loop between prediction and validation [11] [12]. | Includes liquid handlers, automated electrochemistry stations, and computer vision. |

| Multi-Modal Knowledge Base | The curated "data" source. Integrates diverse information (scientific literature, experimental data, simulation results) to provide context and prior knowledge for AI models [11] [8]. | Mitigates bias from single-source data. |

| Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | A "computational accelerator" that provides near-DFT accuracy for molecular dynamics simulations at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling large-scale simulations [9] [14]. | Trained on DFT data. Critical for simulating dynamic properties. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary geometric graph representations for crystals, and how do I choose? The main representations are Crystal Graphs, Crystal Hypergraphs, and Nested Crystal Graphs. Your choice depends on the property you want to predict and the level of geometric detail required. Crystal Graphs are a good starting point for many properties, but if your project involves distinguishing between structurally similar but distinct phases (e.g., cubic vs. square antiprism local environments), a Hypergraph representation is more appropriate as it avoids degenerate mappings [15]. For chemically complex materials like high-entropy alloys, a Nested Crystal Graph is specifically designed to handle atomic-scale disorder [16].

FAQ 2: My model fails to distinguish between crystals with different local atomic environments. What is wrong? This is a classic symptom of a degenerate graph representation. Standard crystal graphs that encode only pair-wise atomic distances lack the geometric resolution to differentiate between distinct local structures that happen to have the same bond connections [15]. To resolve this, you should transition to a model that incorporates higher-order geometric information.

- Solution A: Adopt a Hypergraph Model. Incorporate triplet hyperedges (to explicitly include angular information) or motif hyperedges (to describe the local coordination environment using parameters like local structure order parameters) [15].

- Solution B: Use a Complete Graph Transformer. Frameworks like ComFormer utilize the periodic patterns of unit cells to build more expressive graph representations that are sensitive to complete geometric information and can handle chiral crystals [17].

FAQ 3: How can I represent a solid solution or high-entropy material with a graph model? Traditional graph models struggle with the chemical disorder inherent in these materials. The Nested Crystal Graph Neural Network (NCGNN) is designed for this purpose. It uses a hierarchical structure: an outer graph encodes the global crystallographic connectivity, while inner graphs at each atomic site capture the specific distribution of chemical elements. This allows for bidirectional message passing between element types and crystal motifs, effectively modeling the composition-structure-property relationships in disordered systems [16].

FAQ 4: What are the key computational trade-offs between different geometric representations? The choice of representation directly impacts computational cost and expressive power. The following table summarizes the key considerations:

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Efficiency and Information in Graph Representations

| Representation Type | Key Geometric Information Encoded | Computational Cost Consideration | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Graph [16] | Pair-wise atomic distances | Low cost, efficient for large-scale screening | Predicting properties primarily dependent on bonding and short-range structure. |

| Crystal Hypergraph [15] | Pair-wise distances, triplets (angles), and/or local motifs (coordination polyhedra) | Higher cost; triplet edges scale quadratically with node edges, while motif edges scale linearly. | Modeling properties highly sensitive to 3D local geometry (e.g., catalytic activity, phase stability). |

| Nested Crystal Graph [16] | Global crystal structure and site-specific chemical disorder | Scalable for disordered systems without needing large supercells. | Predicting properties of solid solutions, high-entropy alloys, and perovskites. |

FAQ 5: My experimental data is sparse and unstructured. How can I use AI to guide my research? You can leverage AI and natural language processing (NLP) to create knowledge graphs from unstructured data in patents and scientific papers. Platforms like IBM DeepSearch can convert PDFs into structured formats, extract material entities and their properties, and build queryable knowledge graphs. This synthesized knowledge can help identify promising research directions and previously patented materials, making your discovery process more efficient [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Resolving Low Geometric Resolution in Crystal Graphs

- Symptoms: Poor model performance on tasks requiring angular information; inability to distinguish chiral crystals or different polyhedral arrangements.

Required Reagents & Solutions: Table 2: Research Reagents for Enhanced Geometric Representation

Research Reagent / Solution Function Triplet Hyperedges [15] Represents triplets of atoms (two bonds sharing a node) and associates them with invariant features like the bond angle, introducing angular resolution. Motif Hyperedges [15] Represents the local coordination environment of an atom (a motif), described by quantitative features like Local Structure Order Parameters (LSOPs) or Continuous Symmetry Measures (CSMs). Equivariant Graph Transformers (e.g., eComFormer) [17] Utilizes equivariant vector representations (e.g., coordinates) to directly capture 3D geometric transformations, providing a complete and efficient representation. Experimental Protocol:

- Construct Base Graph: Build a standard crystal graph using a distance cutoff and a maximum number of neighbors [15].

- Identify Higher-Order Structures:

- For triplets: For each atom, identify all sets of two bonds that share it as a common node. Create a hyperedge for each triplet.

- For motifs: For each atom, determine its immediate neighbors using a chosen algorithm. Create one hyperedge per atom to represent its local motif.

- Calculate Features: For each triplet hyperedge, compute the bond angle and encode it (e.g., using a Gaussian expansion). For each motif hyperedge, calculate its descriptor, such as a set of LSOPs [15].

- Train Model: Use a model architecture capable of processing hypergraphs, such as a Crystal Hypergraph Convolutional Network (CHGCNN), which generalizes message passing to handle hyperedges [15].

Issue 2: Modeling Chemically Complex and Disordered Materials

- Symptoms: Model inaccuracy when predicting properties of high-entropy alloys, perovskites, or other solid solutions with multiple principal elements.

Required Reagents & Solutions: Table 3: Research Reagents for Modeling Chemical Disorder

Research Reagent / Solution Function Nested Crystal Graph [16] A hierarchical representation with an outer structural graph for global connectivity and inner compositional graphs for site-specific chemical distributions. Compositional Graph [16] Embedded within the nested graph, it captures the elemental distribution and interactions at a specific atomic site in the crystal lattice. Bidirectional Message Passing [16] A learning mechanism in the nested graph that allows information to flow between the global crystal structure and local chemical compositions, integrating both data types. Experimental Protocol:

- Define Outer Structural Graph: Model the crystal's primitive unit cell as a graph where nodes are atomic sites (ignoring chemical identity for now) and edges represent crystallographic connections [16].

- Define Inner Compositional Graphs: For each atomic site in the structural graph, create a separate graph. The nodes of this inner graph represent the different chemical elements that can occupy that site, capturing the local chemical environment and disorder.

- Implement Hierarchical Learning: Use an NCGNN architecture that performs message passing on two levels: within the inner compositional graphs and within the outer structural graph, with bidirectional information exchange between them [16].

- Predict Properties: The integrated knowledge from both structure and composition is used for end-to-end prediction of material properties, outperforming composition-only models [16].

High-throughput computing (HTC) has revolutionized materials science by enabling the rapid screening and discovery of novel materials with desired properties. This computational approach leverages the power of parallel processing to perform extensive first-principles calculations, thereby accelerating the identification of promising candidates for various applications. By automating and scaling computational workflows, HTC facilitates the efficient exploration of vast chemical and structural spaces, which is essential for the development of advanced materials [19].

Traditional material discovery heavily relies on iterative physical experiments, which are often resource-intensive and time-consuming. HTC offers an efficient alternative by enabling large-scale simulations and data-driven predictions of material properties. The integration of HTC with data-driven methodologies has further optimized performance predictions, making it possible to identify novel materials with desirable properties efficiently [19]. This shift towards digitized material design, combining computational power with intelligent algorithms, is transforming the field by reducing the reliance on trial-and-error experimentation and promoting data-driven innovation.

In electrochemical materials discovery specifically, high-throughput methods have been applied to screening, synthesis, and testing to accelerate material discovery. Most reported studies utilize computational methods, including density functional theory and machine learning, over experimental methods. Some research labs have combined computational and experimental methods to create powerful tools for a closed-loop material discovery process through automated setups and machine learning [20].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The successful implementation of HTC workflows for material screening relies on various computational tools and frameworks that function as essential "research reagents" in silico experiments.

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for HTC in Materials Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in HTC Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| First-Principles Calculation Methods | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Provides accurate predictions of electronic structure, stability, and reactivity without empirical parameters [19] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Gaussian Approximation Potentials (GAP), Deep Potential Molecular Dynamics (DeePMD) | Acts as surrogates for ab initio methods, offering significant speed advantages while retaining high fidelity [19] |

| Workflow Management Systems | mkite platform | Automates processes of structure generation, property calculation, and data analysis, ensuring consistency and reproducibility [19] |

| Graph-Embedded Prediction Models | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Integrates multi-modal data for structure-property mapping in material design [19] |

| Containerization Technologies | Singularity Container Images (e.g., minimap2.sif) | Ensures computational environment consistency and reproducibility across distributed HTC systems [21] |

HTC System Architecture and Workflow Organization

Core HTC Infrastructure Components

High-performance computing infrastructure coordinates many discrete units capable of independent computation to cooperate on portions of a task. This approach completes far more computation in a given amount of time than any of the units could do individually. In other words, an HPC system consists of many individual computers working together [22].

Key architectural components include:

- Compute Nodes: Complete, independent systems with their own operating systems and resources, where computational jobs are executed with exclusive user access [22]

- Login Nodes: Shared preparation systems where users authenticate, stage their environment, and launch jobs, with resource limits to ensure fair usage [22]

- Distributed File Systems: Specialized storage infrastructure like the Open Science Data Federation (OSDF) that caches frequently accessed files to improve transfer efficiency [21]

Optimal Directory Structure for HTC Workflows

Proper organization of files and directories is crucial for successful HTC operation. A well-structured approach separates files based on their usage patterns across jobs:

This organizational structure optimizes data transfer efficiency by considering which files will be reused across jobs versus those specific to individual jobs. Frequently reused files (such as reference genomes and container images) benefit from caching when stored in specialized directories and accessed via the osdf:// transfer plugin, while job-specific files reside in home directories for direct transfer [21].

Experimental Protocols for HTC Material Screening

High-Throughput Workflow for Material Property Prediction

Advanced HTC frameworks for materials research combine physics-informed machine learning with generative optimization for material design and performance prediction. The methodology consists of three major components [19]:

- Graph-Embedded Material Property Prediction Model: Integrates multi-modal data for structure-property mapping using graph neural networks to capture complex material relationships

- Generative Model for Structure Exploration: Utilizes reinforcement learning to explore novel material structures beyond existing databases

- Physics-Guided Constraint Mechanism: Ensures realistic and reliable material designs by embedding domain-specific priors into the deep learning framework

This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in prediction accuracy while maintaining physical interpretability compared to state-of-the-art models [19].

Data Partitioning Protocol for Distributed Computation

Effective HTC implementation requires proper data partitioning to optimize resource utilization:

The protocol involves:

- Subsetting Calculation: Determine appropriate subset size based on ideal job profiles (typically 10 minutes to <10 hours runtime, 1-5 GB RAM) [21]

- File Division: Use utilities like

splitto divide large input files into manageable chunks (e.g., 56,000 lines for FASTQ files equivalent to 14,000 reads) [21] - Job Submission: Create HTCondor submit files that process these subsets as independent parallel jobs

- Output Management: Collect and aggregate results from all completed jobs for comprehensive analysis

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common HTC Implementation Issues and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common HTC Issues in Material Screening

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Jobs remaining in idle state for extended periods | Resource requests exceeding typical availability (e.g., >10hrs runtime, >5GB RAM, >1GB inputs/outputs) | Optimize job profiles by further subdividing workloads; Adjust resource requests to match typical OSPool availability [21] |

| Low prediction accuracy in material property models | Limited generalization of conventional predictive models; Inadequate incorporation of domain knowledge | Implement physics-informed machine learning; Embed domain-specific priors into deep learning frameworks; Use graph-embedded material property prediction models [19] |

| Computational tasks unfairly limited on login nodes | Running computationally intensive work on shared login nodes instead of compute nodes | Reserve CPU-intensive tasks for compute nodes; Use login nodes only for job preparation and submission; Adhere to resource limits (8 cores, 100GB RAM per user) [22] |

| Inefficient file transfers slowing workflow | Transferring common files repeatedly instead of leveraging caching | Store frequently reused files in OSDF-accessible directories; Use osdf:// transfer plugin; Structure directories based on file usage patterns [21] |

| System accessibility issues | External access without proper authentication; Firewall restrictions | Use OTP tokens for external access; Connect via VPN for internal access; Ensure proper two-factor authentication setup [22] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What distinguishes High-Throughput Computing (HTC) from High-Performance Computing (HPC)?

A1: While both leverage parallel computing resources, HTC focuses on executing many independent computational tasks (often with modest resource requirements) across distributed systems, ideal for parameter sweeps and material screening. HPC typically involves tightly-coupled computations requiring specialized, high-end infrastructure with fast interconnects for a smaller number of powerful jobs [22] [23].

Q2: How can I determine the optimal job size for material screening workflows?

A2: Ideal job profiles on shared pools like the OSPool typically have: runtimes between 10 minutes and 10 hours, memory requirements of 1-5 GB, and input/output files each under 1 GB. Jobs with larger profiles may face significantly increased idle time while waiting for matching resources [21].

Q3: What strategies improve the generalizability of machine learning models in material discovery?

A3: Hybrid approaches that combine physics-informed machine learning with generative optimization significantly enhance generalizability. Methods include embedding domain-specific priors into deep learning frameworks, incorporating uncertainty quantification techniques, and using graph-embedded prediction models that integrate multi-modal data for improved structure-property mapping [19].

Q4: How should I organize files for optimal HTC performance?

A4: Implement a structured approach that separates job-specific files (stored in home directories) from commonly reused files (stored in OSDF-accessible directories). This minimizes transfer overhead by leveraging caching for frequently accessed data while maintaining simplicity for transient files [21].

Q5: What are the most promising computational methods being integrated with HTC for material discovery?

A5: Emerging approaches include: physics-informed machine learning with generative optimization, universal machine learning potentials as DFT surrogates, graph neural networks for structure-property mapping, and automated workflows combining symbolic AI with deep learning for improved interpretability and accuracy [19].

Advanced HTC Methodologies and Future Directions

The integration of HTC with artificial intelligence is creating powerful new paradigms for materials research. Recent advances include Event Workflow Management Systems (EWMS) that enable previously impractical scientific workflows by transforming how HTCondor is used for massively parallel, short-runtime tasks [24]. These systems are accelerating discovery across domains from astrophysics to protein modeling and large-scale materials screening.

Industrial applications are also driving innovation in HTC methodologies. As noted in recent symposiums, there is growing implementation of Integrated Computational Materials Engineering (ICME) in model-based design and screening of new materials, supported by government investments to accelerate qualification and certification of advanced manufacturing methods [25]. The future of HTC in materials science will likely involve greater integration of autonomous laboratories with computational screening, creating closed-loop discovery systems that dramatically reduce development timelines for novel materials.

These advancements highlight the evolving role of HTC as not just a computational tool, but as a foundational paradigm enabling next-generation materials discovery through intelligent workflow design, appropriate resource management, and the strategic integration of physical principles with data-driven methodologies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between traditional simulation methods and data-driven inverse design?

Traditional simulation methods, like Density Functional Theory (DFT), are experiment-driven and rely on a trial-and-error process. Scientists hypothesize a structure, compute its properties, and then refine the hypothesis in a slow, iterative cycle [26]. In contrast, data-driven inverse design flips this paradigm. Generative AI models learn the underlying probability distribution between a material's structure and its properties. Once learned, researchers can specify desired properties, and the model generates novel, stable material structures that meet those criteria, dramatically accelerating discovery [26].

FAQ 2: Our research involves complex nanostructures. Can inverse design handle molecules of different sizes and complexities?

Yes, this is a key strength of modern graph-based models. Frameworks like AUGUR use Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to encode molecular systems. The "pooling" properties of graphs allow the same model to process molecules of different sizes and complexities without requiring hand-crafted feature extraction for each new system [27]. This enables the model to predict the properties of large, complex systems even when trained on data from smaller, less computationally expensive ones [27].

FAQ 3: What are the common data-related challenges when implementing an inverse design pipeline?

Two primary challenges are data scarcity and dataset bias. High-quality, curated materials data is not always available for every system of interest [26]. Furthermore, differences in experimental protocols and recording methods between labs can lead to dataset mismatches, where data from one source may not be directly compatible with another, potentially biasing the model [26]. Emerging approaches to overcome this include using multi-fidelity data and physics-informed architectures that incorporate known physical laws to reduce the reliance on massive, purely experimental datasets [26].

FAQ 4: How can we ensure that the materials generated by an AI model are stable and synthesizable?

This remains an active area of research. A critical feature of generative models is their latent space—a lower-dimensional representation of structure-property relationships. By sampling from regions of this space that correspond to high-probability (and thus more stable) configurations, models can propose viable candidates [26]. Furthermore, integrating these models into closed-loop discovery systems, where AI-generated suggestions are validated through automated simulations or high-throughput experiments, allows for continuous feedback and refinement of both the suggestions and the model's understanding of synthesizability [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Generative Model Producing Physically Implausible Material Structures

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or Biased Training Data | Analyze the training dataset for coverage and diversity. Check if generated structures violate basic chemical or physical rules. | Curate a more representative dataset. Incorporate multi-fidelity data or use data augmentation techniques. |

| Poorly Constructed Latent Space | Use the model's built-in uncertainty quantification (if available). Analyze the proximity of implausible structures to known stable ones in the latent space. | Employ models with strong probabilistic foundations like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) or Gaussian Processes (GPs) that better structure the latent space [26] [27]. |

| Lack of Physical Constraints | Verify if the model's output obeys known symmetry or invariance (e.g., rotation, translation). | Implement a physics-informed neural network (PINN) that incorporates physical laws directly into the model's architecture or loss function [26]. |

Issue 2: Slow or Inefficient Convergence in Bayesian Optimization for Adsorption Site Identification

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Surrogate Model | Monitor the model's prediction error and uncertainty calibration over iterations. | Replace a simple Gaussian Process (GP) with a surrogate model that uses a Graph Neural Network (GNN) for feature extraction, as in the AUGUR pipeline, for better generalization and symmetry awareness [27]. |

| Poor Acquisition Function Performance | Analyze the suggestion history of the Bayesian Optimization (BO) algorithm. | Tune the acquisition function's balance between exploration and exploitation, or switch to a different function (e.g., from Expected Improvement to Upper Confidence Bound). |

| High-Dimensional Search Space | Check the dimensionality of the feature vector used to describe the system. | Use a symmetry- and rotation-invariant model to reduce the effective search space, allowing the optimal site to be found with far fewer iterations (e.g., ~10 DFT runs) [27]. |

General Troubleshooting Methodology for Computational Workflows

When a computational pipeline fails, follow this structured approach adapted from general technical support principles [28] [29]:

- Understand the Problem: Reproduce the error. Gather all relevant logs, error messages, and input parameters. Ensure you can consistently trigger the issue [28].

- Isolate the Issue: Simplify the problem. For example, test your model on a small, well-understood dataset before running it on a large, complex one. Change one variable at a time (e.g., learning rate, model architecture) to narrow down the root cause [28].

- Find a Fix or Workaround: Based on the isolated cause, implement a targeted solution. This could be a code update, a change in parameters, or a data pre-processing step. Always test the fix in a controlled environment before applying it to your main project [28].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AUGUR vs. Monte Carlo Sampling for Adsorption Site Identification [27]

| Nanosystem Adsorbent | Adsorbate | Lowest Interaction Energy (AUGUR) | Lowest Interaction Energy (Monte Carlo) | Improvement by AUGUR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt3 Chini Cluster | Zn²⁺ ion | -1.95 eV | -1.79 eV | 8.73% |

| Pt9 Chini Cluster | Zn²⁺ ion | -2.23 eV | -2.14 eV | 142.62% |

| (ZnO)78 Cluster | Gas Molecule | Results achieved in ~10 DFT runs | Exhaustive sampling computationally infeasible | High efficiency |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Computational Materials Discovery

| Item / Algorithm | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Generative Model (e.g., VAE, GAN, GFlowNet) | Learns the probability distribution of material structures and properties to enable inverse design [26]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Processes molecular structures as graphs, providing symmetry-awareness and transferability across different molecule sizes [27]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A data-efficient optimization strategy that uses a surrogate model to intelligently suggest the next experiment, minimizing costly simulations [27]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A surrogate model that provides predictions with built-in uncertainty quantification, crucial for guiding Bayesian Optimization [27]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computational method for electronic structure calculations used to generate high-fidelity training data and validate model suggestions [27]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Inverse Design vs Traditional Workflow

AUGUR Optimization Pipeline

Efficient Generation in Practice: AI Methods and Targeted Optimization Frameworks

The application of Generative AI in materials science is revolutionizing the discovery and design of novel materials, from triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS) for lightweight structures to new drug candidates and energy-efficient metamaterials [30] [31]. As researchers deploy models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and Diffusion Models, significant computational challenges emerge. These challenges include prohibitive training times, hardware limitations, and the energy-intensive nature of model iteration [32]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols to help materials scientists overcome these hurdles, enhancing the computational efficiency and practical viability of their generative AI research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges and Solutions

The table below summarizes frequent issues encountered when using generative models for materials science, along with diagnostic steps and proven solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Generative AI in Materials Research

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Output Quality | Blurry or unrealistic material microstructures [33] [34] | VAE's simplified posterior or pixel-wise loss [35] | Check reconstruction loss; compare output diversity | Switch to Diffusion Model; use a GAN-based model; employ a sharper loss function [33] [34] |

| Output Diversity | Mode collapse: limited variety of generated materials [35] | GAN training instability or discriminator overpowering [35] | Monitor generated samples over training; calculate diversity metrics | Use training techniques like gradient penalty or spectral normalization [35] |

| Training Stability | Unstable loss values or failure to converge [35] | Poor balance between generator/discriminator in GANs [35] | Log and visualize generator & discriminator losses separately | Implement Wasserstein loss; use gradient penalty; adjust learning rates [35] |

| Computational Efficiency | Extremely long sampling/generation times [36] | Diffusion models requiring hundreds of denoising steps [35] [36] | Profile code to identify time-consuming steps | Use distilled diffusion models; fewer denoising steps; hybrid architectures [36] |

| Scientific Accuracy | Physically implausible material designs [34] | Model hallucinations; poor domain alignment [34] | Domain-expert validation; physical law verification [34] | Incorporate physical constraints into loss; use domain-adapted pre-training [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My generative model produces visually convincing material structures, but simulation shows they are physically implausible. How can I improve physical accuracy?

This is a common challenge where models optimize for visual fidelity but not scientific correctness. The solution is to integrate physical knowledge directly into the learning process. You can:

- Incorporate Physical Constraints: Add custom terms to your loss function that penalize violations of known physical laws (e.g., energy conservation, stress-strain relationships).

- Use Hybrid Modeling: Employ a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) where the discriminator is not just judging realism but also incorporates a physics-based simulator to assess physical validity [34].

- Expert Validation Loop: Implement an iterative process where generated materials are validated by a domain expert or a high-fidelity simulator, with the feedback used to fine-tune the model [34].

Q2: The sampling process from my Diffusion Model is too slow for high-throughput materials screening. What are the most effective acceleration strategies?

Sampling speed is a recognized bottleneck for diffusion models. To accelerate inference:

- Use Advanced Solvers: Replace the default denoising process with faster Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) solvers like DPM-Solver or DDIM, which can reduce the number of required steps from thousands to tens or hundreds [36].

- Model Distillation: Apply knowledge distillation techniques to train a smaller, faster student model that mimics the output of your large, slow teacher model, significantly cutting down sampling time [36].

- Latent Diffusion: Instead of operating in the high-dimensional pixel space, train your diffusion model in a lower-dimensional latent space created by a VAE. This dramatically reduces computational overhead [34].

Q3: How can I manage the high energy and computational costs of training large generative models on limited hardware resources?

Computational cost is a major constraint. Several approaches can improve efficiency:

- Algorithmic Optimization: Apply pruning to remove redundant neurons from the network and quantization to represent weights with fewer bits, reducing model size and computation needs [32].

- Hardware and Scheduling: Leverage "information batteries" – perform intensive pre-computations or model training during off-peak hours when energy demand and cost are lower [32].

- Edge Computing: For inference tasks, use edge computing to process data locally on specialized hardware, reducing data transfer costs and enabling faster, more private analysis [32].

Q4: For a new project generating novel polymer structures, which model should I choose to balance quality, diversity, and control?

The choice depends on your primary constraint and goal. Refer to the comparison table below for guidance.

Table 2: Model Selection Guide for Materials Generation Tasks

| Criterion | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Diffusion Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Fidelity | High (Can produce sharp, realistic samples) [33] | Low to Medium (Often produces blurry outputs) [33] [34] | Very High (State-of-the-art image quality) [33] [34] |

| Sample Diversity | Medium (Prone to mode collapse) [35] [33] | High (Explicitly models data distribution) [33] | Very High (Excels at diverse sample generation) [33] |

| Training Stability | Low (Requires careful balancing of networks) [35] [33] | High (Stable training based on likelihood) [33] | Medium (More stable than GANs) [36] |

| Sampling Speed | Fast (Single forward pass) [33] | Fast (Single forward pass) [33] | Slow (Requires many iterative steps) [35] [33] |

| Latent Control | Moderate (via latent space interpolation) | High (Structured, interpretable latent space) [35] | Moderate (increasing with new methods) |

| Best For | Rapid generation of high-fidelity structures when computational budget is limited. | Exploring a diverse landscape of material designs and interpolating between known states. | Projects where ultimate accuracy and diversity are critical, and computational resources are available. |

For polymer generation, if you have a large compute budget and need high-quality, diverse samples, a Diffusion Model is superior. If you need faster iteration and can accept slightly less sharp outputs, a modern GAN (like StyleGAN) is a strong choice [34].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative Evaluation of Generated Material Samples

Objective: To rigorously assess the quality and diversity of generated material structures (e.g., micro-CT scans, molecular graphs) using a combination of metrics.

Methodology:

- Calculate FID (Fréchet Inception Distance): Measure the statistical similarity between generated images and a validation set of real material samples. A lower FID score indicates better fidelity [34].

- Compute SSIM (Structural Similarity Index): Assess the perceptual quality and structural coherence of individual generated samples compared to a reference image [34].

- Measure LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity): Evaluate the diversity of generated samples by quantifying their perceptual differences. A healthy range of LPIPS values indicates good diversity [34].

- Expert Validation: Crucially, have domain experts (e.g., materials scientists) conduct a blind review of generated samples to rate them for physical plausibility and scientific utility. Standard metrics can be misleading, making this step essential [34].

Protocol 2: Efficient Training of a Diffusion Model for Material Generation

Objective: To train a high-quality diffusion model for material image synthesis while optimizing for computational efficiency.

Methodology:

- Latent Space Setup: First, train a VAE to compress material images into a lower-dimensional latent space. Your diffusion model will then be trained to denoise within this latent space, greatly improving speed (Latent Diffusion) [34].

- Noise Scheduling: Employ a cosine noise schedule during the forward diffusion process. This has been shown to lead to better performance and more stable training than linear schedules [36].

- Conditioning Strategy: For task-specific generation (e.g., "generate a material with porosity X"), condition the model using a cross-attention mechanism on the text or parameter embeddings [36].

- Accelerated Sampling: After training, use an ODE solver (like DPM-Solver) for the reverse denoising process. This allows you to generate high-quality samples in 50-100 steps instead of the default 1000, drastically reducing inference time [36].

Diagram 1: Efficient Latent Diffusion Model Workflow.

Protocol 3: Mitigating Mode Collapse in GANs for Diverse Structure Generation

Objective: To ensure a GAN generates a wide variety of material structures instead of a limited set of modes.

Methodology:

- Architectural Selection: Choose a GAN variant known for improved stability, such as Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) or a GAN using Spectral Normalization [35].

- Mini-batch Discrimination: Implement a mini-batch discrimination layer in the discriminator. This allows the discriminator to look at multiple data samples in combination, helping it detect and penalize a lack of diversity in the generator's output.

- Experience Replay: Periodically archive and mix previously generated samples from the generator into the current training batch for the discriminator. This prevents the discriminator from "forgetting" what earlier modes looked like.

- Monitoring: Continuously track diversity metrics like LPIPS on a held-out validation set during training to detect the early signs of mode collapse.

Diagram 2: GAN Adversarial Training Loop.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Generative Materials Research

| Resource / "Reagent" | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Materials AI |

|---|---|---|---|

| StyleGAN / StyleGAN3 | Software Model (GAN) | High-fidelity image generation. | Generating realistic 2D material microstructures and surfaces [34]. |

| Stable Diffusion | Software Model (Diffusion) | Latent diffusion for text-to-image. | Generating and inpainting material structures from text descriptions (e.g., "a porous metal-organic framework") [34]. |

| DDPM (Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model) | Algorithm | Core formulation for many diffusion models. | The foundation for training custom diffusion models on proprietary materials data [36] [34]. |

| CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) | Model | Connects text and images in a shared space. | Providing semantic control and conditioning for generative models based on material descriptions [34]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Model Architecture | Learns from graph-structured data. | Directly generating molecular graphs or crystal structures, a native representation for atoms and bonds [36]. |

| WGAN-GP (Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty) | Training Technique | Stabilizes GAN training. | Prevents mode collapse, ensuring diverse generation of material designs [35]. |

| DPM-Solver | Software (ODE Solver) | Accelerates diffusion model sampling. | Drastically reduces the time needed to generate samples from a trained diffusion model [36]. |

What is Target-Oriented Bayesian Optimization? Traditional Bayesian Optimization (BO) is designed to find the maximum or minimum value of a black-box function, making it ideal for optimizing material properties for peak performance [37]. However, many real-world applications require achieving a specific target property value, not just an optimum. Target-Oriented Bayesian Optimization is a specialized adaptation that efficiently finds input conditions that yield a predefined output value, dramatically reducing the number of expensive experiments needed [37] [38].

This approach is crucial for materials design, where exceptional performance often occurs at specific property values. For example, catalysts may have peak activity when an adsorption free energy is near zero, or thermostatic materials must transform at a precise body temperature [37]. Methods like t-EGO (target-oriented Efficient Global Optimization) introduce a new acquisition function, t-EI, which explicitly rewards candidate points whose predicted property values are closer to the target, factoring in the associated uncertainty [37].

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My target-oriented optimization seems to be exploring too much and not zeroing in on the solution. What could be wrong?

A: This is often related to the balance between exploration and exploitation. Unlike standard BO, target-oriented methods like t-EGO define improvement based on proximity to a target, not improvement over a current best value [37].

- Check Your Acquisition Function: Ensure you are using a target-specific acquisition function like t-EI. Using a standard acquisition function like Expected Improvement (EI) on a reformulated objective (e.g., minimizing |y - t|) is sub-optimal because EI seeks to minimize without a lower bound, not to reach zero [37].

- Review Model Uncertainty: If your surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process) is highly uncertain across the entire search space, the algorithm will prioritize exploration. If you have domain knowledge that constrains the search space, applying those constraints can reduce unnecessary uncertainty and improve convergence [39] [40].

Q2: How do I handle multiple target properties or complex constraints?

A: Single-objective, target-oriented BO can struggle with complex, multi-property goals.

- Use a Framework for Complex Goals: Consider frameworks like Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX), which allows you to define your experimental goal through a simple filtering algorithm. The framework (e.g., using InfoBAX, MeanBAX, or SwitchBAX) then automatically creates a data acquisition strategy to find the subset of the design space that meets your precise, multi-property criteria [38].

- Incorporate Known Constraints: For non-linear or interdependent experimental constraints, use BO algorithms that can handle arbitrary known constraints through an intuitive interface, such as extended versions of PHOENICS or GRYFFIN [39].

Q3: The optimization is slow and computationally expensive. Are there alternatives to Gaussian Processes?

A: Yes, computational expense is a known limitation, especially with high-dimensional search spaces [41].

- Switch to Scalable Surrogate Models: For higher-dimensional problems or when speed is critical, consider using Random Forests with advanced uncertainty quantification (e.g., as implemented in the Citrine platform). These can retain the data-efficiency of BO while offering greater speed and built-in tools for interpretability [41].

- Optimize Your Search Space: The efficiency of BO is highly dependent on the "compactness" of the search space. Formulations that remove degeneracies and symmetries can significantly improve performance. Always strive for the most irreducible representation of your problem [40].

Q4: How can I trust a suggestion from a black-box model for my critical experiment?

A: Building trust is essential for the adoption of these methods.

- Leverage Interpretability Tools: Choose platforms or models that provide feature importance and parameter contribution analyses. For instance, Random Forest-based approaches can show which input variables most influence the prediction, helping you understand the model's "reasoning" [41] [42].

- Inspect 1D and 2D Slices: Use visualization tools to see how the model's prediction for your target property changes as a single parameter varies (1D slice) or as two parameters interact (2D surface). This helps validate that the recommendations align with your scientific intuition [42].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

The table below summarizes key experimental details from a case study successfully employing target-oriented BO.

Table 1: Experimental Protocol for Discovering a Target Shape Memory Alloy

| Protocol Aspect | Details from Case Study |

|---|---|

| Overall Goal | Discover a thermally-responsive shape memory alloy (SMA) with a phase transformation temperature of 440 °C for use in a thermostatic valve [37]. |

| Optimization Method | t-EGO (target-oriented Efficient Global Optimization) using the t-EI acquisition function [37]. |

| Surrogate Model | Gaussian Process [37]. |

| Result | Ti0.20Ni0.36Cu0.12Hf0.24Zr0.08 |

| Performance | Achieved transformation temperature of 437.34 °C—only 2.66 °C from the target—within 3 experimental iterations [37]. |

| Comparative Efficiency | In repeated trials on synthetic functions and material databases, t-EGO required ~1 to 2 times fewer iterations to reach the same target compared to EGO or Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions (MOAF), especially with small training datasets [37]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of the target-oriented Bayesian optimization process, as implemented in the t-EGO method.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table lists key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for implementing target-oriented Bayesian optimization.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Target-Oriented BO

| Tool / Component | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Target-Oriented Acquisition Function (t-EI) | The core heuristic that guides candidate selection by calculating the expected improvement of getting closer to a specific target value, factoring in prediction uncertainty [37]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model | A probabilistic model that provides a posterior distribution over the black-box function, giving both a predicted mean and uncertainty (standard deviation) at any point in the search space [37] [43]. |

| BAX Framework (InfoBAX, MeanBAX, SwitchBAX) | A framework that automatically generates custom data acquisition strategies to find design points meeting complex, user-defined goals, bypassing the need for manual acquisition function design [38]. |

| Constrained BO Algorithms (e.g., PHOENICS, GRYFFIN) | Extended versions of BO algorithms that can handle arbitrary, non-linear known constraints (e.g., experimental limitations, synthetic accessibility) via an intuitive interface [39]. |

| Random Forest with Uncertainty | An alternative surrogate model to GPs that offers better scalability for high-dimensional problems and provides inherent interpretability through feature importance metrics [41]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PINN Issues and Solutions

1. My PINN fails to converge or converges very slowly. What are the primary causes? Convergence failure often stems from improper loss balancing, inadequate network architecture, or poorly chosen training points [44].

- Solution: Implement an adaptive loss weighting scheme rather than using fixed weights. Monitor the magnitude of both data and physics losses during training; their scales should be comparable. If one dominates, adjust its weight dynamically [44]. Also, ensure your training (collocation) points sufficiently cover the domain, including boundary and initial condition regions [45].

2. The model's physics loss is high, indicating it violates known physical laws. How can I improve physical consistency? This occurs when the physics-informed part of the loss function is not being minimized effectively, often due to gradient pathologies or an insufficient number of collocation points [44].

- Solution:

- Gradient Pathology: The gradients of the physics loss can become imbalanced during training. Consider using gradient-based loss weighting methods that assign higher importance to points with larger residuals [44].

- Sampling Strategy: Increase the density of collocation points in regions where the solution is complex or has high gradients. Adaptive sampling, where points are added in areas of high physics loss, can be highly effective [45].

3. My PINN overfits to the physics loss but does not match the available observational data. What should I do? This suggests an over-emphasis on the physics constraint at the expense of fitting the real data.

- Solution: Re-calibrate the loss weights (

data_weightandphys_weight). Increase thedata_weightto give more importance to the observational data. Furthermore, validate that your physics equations are correctly formulated and implemented in the loss function [45].

4. I have very limited training data. Can PINNs still work? Yes, a key advantage of PINNs is their data efficiency. The physics loss acts as a regularizer, constraining the solution to physically plausible outcomes [46] [47].

- Solution: A study by Southwest Research Institute demonstrated that their physics-informed convolutional network (PIGCN) achieved high accuracy (R² = 0.87) using only 2% of the training data required by a traditional ML model [47]. Prioritize the precise implementation of boundary and initial conditions in your loss function, as these provide critical supervisory signals in the absence of data [45].

5. How do I choose an appropriate network architecture and activation function? The choice of architecture and activation function is critical for learning complex, high-frequency solutions [44].

- Solution:

- Activation Function: Avoid using ReLU, as its second derivative is zero, which can hinder learning dynamics governed by higher-order derivatives. The hyperbolic tangent (

tanh) is a common choice. Some research suggests that GELU activations can offer theoretical and empirical benefits overtanh[45]. - Architecture: Start with a fully connected network with 4-5 layers and 128-256 neurons per layer. The optimal size is problem-dependent, so experimentation is necessary [45].

- Activation Function: Avoid using ReLU, as its second derivative is zero, which can hinder learning dynamics governed by higher-order derivatives. The hyperbolic tangent (

Experimental Protocol: Accelerated Discovery of B2 Multi-Principal Element Intermetallics

The following methodology is derived from a published framework for discovering novel materials, demonstrating the real-world application of PINNs in materials science [48].

1. Objective: To rapidly identify novel single-phase B2 multi-principal element intermetallics (MPEIs) in complex compositional spaces (quaternary to senary systems) where traditional methods are inefficient [48].

2. Machine Learning Framework: A hybrid physics-informed ML model integrating a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) for generative design and an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) for stability prediction [48].

3. Data Curation and Physics-Informed Descriptors:

- Data Collection: Compiled a database of known alloy compositions and their phases (B2, multi-phase intermetallics, solid-solution + intermetallic) from literature and phase diagrams [48].

- Descriptor Engineering: Moved beyond classic "random-mixing" parameters (e.g.,

ΔHmix,δ). Instead, developed 18 "random-sublattice-based" descriptors informed by a physical model of the B2 crystal structure. These descriptors quantify the thermodynamic driving force for chemical ordering between two sublattices, such as [48]:δpbs: Atomic size difference between sublattices.ΔHpbs: Enthalpy of mixing between sublattices.σVECpbs: Variance in valence electron concentration between sublattices.(H/G)pbs: Parameter quantifying ordering tendency.

4. Training and High-Throughput Screening:

- The ANN was trained on the curated dataset using the 18 physics-informed descriptors to classify an alloy's potential to form a single-phase B2 structure.

- The CVAE was used to generate new, plausible alloy compositions within the latent space defined by these physical constraints.

- The trained model screened vast compositional spaces, prioritizing candidates with a high probability of forming stable B2 phases for further validation [48].

Quantitative Data on PINN Performance

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from case studies on physics-informed machine learning.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from PINN Implementations

| Study / Application Focus | Key Performance Metric | Result | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Damage Characterization (PIGCN Model) [47] | Prediction Accuracy (R²) vs. Training Data | R² = 0.87 using only 2% of training data | Demonstrates significant data efficiency; reduces a major hurdle in materials engineering. |

| Materials Damage Characterization (Traditional ML) [47] | Prediction Accuracy (R²) vs. Training Data | R² = 0.72 using 9% of training data | Traditional models require more data to achieve lower accuracy. |

| B2 MPEI Discovery [48] | Data Balance in Original Dataset | B2 to non-B2 ratio of ~1:9 | Highlights the framework's capability to handle imbalanced data, a common challenge. |

| General PINN Workflow [46] | Training Sample Requirement | Reduces required samples by "several orders of magnitude" | Physics constraints make ML feasible for problems where data is scarce or expensive. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for a PINN Framework

| Item / Component | Function / Explanation | Exemplars / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Automatic Differentiation (AD) | The core engine that calculates precise derivatives of the network's output with respect to its inputs, enabling the formulation of the physics loss. | Built into frameworks like TensorFlow, PyTorch, and JAX. Essential for computing terms in PDEs [45]. |

| Differentiable Activation Functions | Activation functions that are smooth and have defined higher-order derivatives, which are necessary for representing physical laws involving derivatives. | tanh, GELU (may offer benefits over tanh) [45]. Avoid ReLU. |