Strategies for Controlling Scaling in Membrane Distillation Crystallization: Mechanisms, Methods, and Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of scaling control in Membrane Distillation Crystallization (MDCr), an emerging technology for hypersaline wastewater treatment and resource recovery.

Strategies for Controlling Scaling in Membrane Distillation Crystallization: Mechanisms, Methods, and Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of scaling control in Membrane Distillation Crystallization (MDCr), an emerging technology for hypersaline wastewater treatment and resource recovery. Targeting researchers and process engineers, we explore the fundamental mechanisms of membrane scaling and wetting, evaluate innovative mitigation strategies including heterogeneous seeding and advanced spacers, and present optimization techniques for long-term operational stability. Drawing from recent experimental and pilot-scale studies, the review systematically compares the efficacy of various scaling control methods, their impact on crystal quality, and their role in enabling robust Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) processes. The findings offer critical insights for advancing MDCr implementation in industrial applications, including pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturing where precise crystallization control is paramount.

Understanding Scaling and Wetting Fundamentals in MDC

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my membrane experience rapid flux decline and increased pressure during brackish water treatment?

Answer: This is typically caused by inorganic scaling, specifically carbonate scaling from calcium and magnesium salts. In brackish water desalination using Vacuum Membrane Distillation (VMD), mineral scaling constitutes the primary fouling mechanism, with calcium carbonate predominantly existing in the aragonite crystal structure appearing as needle-like crystals [1].

The fouling layer consists of approximately 79.7% inorganic substances, primarily Mg ions (10.1%) and Ca ions (4.5%), along with organic substances (20.3%) predominantly composed of polysaccharides that form at the interface between scaling-scaling and scale-membrane [1] [2]. This compact foulant layer reduces the effective separation area and hinders vapor mass transport, leading to the observed performance decline [1].

Immediate Action Steps:

- Analyze feedwater composition to identify scaling potential

- Implement acetic acid cleaning (0.1-0.5% solution, pH ~2) for carbonate scale removal [1]

- Adjust operating temperature to control supersaturation rates [3]

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between different types of membrane fouling?

Answer: Different fouling types exhibit distinct characteristics and require specific mitigation approaches [4]:

Table: Fouling Types and Characteristics

| Fouling Type | Primary Components | Visual Indicators | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Scaling | CaCO₃, CaSO₄, NaCl, Mg salts [1] | Needle-like (aragonite) and block crystals [1] | Flux instability, increased TMP, pore blockage [1] |

| Organic Fouling | Polysaccharides, organic matter [1] [2] | Gel-like layer at scale-membrane interface [1] | Reduced hydrophobicity, flux decline [1] |

| Biofouling | Microorganisms, EPS [4] | Slimy surface biofilm | Rapid flux decline, membrane degradation |

| Colloidal Fouling | Suspended particles, silts [4] | Uniform surface deposition | Gradual flux reduction |

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Visual Inspection: Use SEM imaging to examine crystal morphology [1]

- Elemental Analysis: Employ EDS to identify primary elements (Ca, Mg, C, O for carbonates) [1]

- Flux Behavior Monitoring: Record flux patterns - unstable flux (113.97 to 327.35 g/(m²·h)) indicates scaling [1]

FAQ 3: What cleaning strategies effectively restore membrane performance after scaling occurs?

Answer: Cleaning efficiency varies significantly by scaling composition. Research shows acetic acid demonstrates superior efficacy in removing carbonate scaling compared to other methods [1].

Table: Cleaning Efficiency Comparison for Carbonate Scaling

| Cleaning Method | Protocol | Efficiency | Mechanism | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid (HAc) | 0.1-0.5% solution, dynamic flow, pH ~2 [1] | Superior for carbonate scaling [1] | Dissolves carbonate crystals | May require concentration optimization |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Dilute solution (pH ~2), dynamic treatment [1] | Significant scaling reduction [1] | Strong acid dissolution | Potential membrane damage at high concentrations |

| Ultrasonication (UA) | High-frequency sound waves [1] | Limited effectiveness [1] | Physical disruption | Ineffective for alkaline scaling |

| Deionized Water (DW) | Flushing at operating temperature [1] | Limited effectiveness [1] | Dilution and physical removal | Cannot dissolve crystallized scales |

Optimal Cleaning Protocol:

- Pre-cleaning Assessment: Analyze foulant composition through SEM/EDS [1]

- Solution Preparation: Prepare 0.3% acetic acid solution (pH ~2)

- Dynamic Cleaning: Recirculate for 30-60 minutes at moderate flow rates

- Post-cleaning Validation: Measure flux recovery and examine membrane surface

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Scaling Mechanism Analysis in VMD

Objective: To elucidate morphology, distribution, and crystal form of scaling in brackish water treatment [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Commercial tubular membrane module (polypropylene hollow-fiber)

- Brackish water source (e.g., Ta'nan drainage canal, Xinjiang)

- Conductivity meter

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS)

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Experimental Procedure:

- System Setup: Install membrane module with effective area of 0.068 m² [1]

- Long-term Performance Monitoring:

- Operate intermittent VMD for brackish water treatment

- Monitor salt rejection (>99.2%) and conductivity (<50 μS/cm)

- Record flux instability within range of 113.97-327.35 g/(m²·h) [1]

- Membrane Autopsy:

- Collect fouled membrane samples after flux decline

- Fix specimens in glutaraldehyde (2.5%) for 2 hours

- Dehydrate using graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 90%, 100%)

- Critical point dry and sputter-coat with gold for SEM analysis [1]

- Foulant Characterization:

- Perform SEM imaging at various magnifications (1000X-5000X)

- Conduct EDS for elemental composition analysis

- Use XRD to identify crystal polymorphs (aragonite vs. calcite) [1]

Data Analysis:

- Identify needle-like aragonite crystals as primary scaling form [1]

- Quantify organic fouling at scale-membrane interface [1]

- Correlate flux decline patterns with specific scaling types

Advanced Anti-Fouling Membrane Fabrication Protocol

Objective: To create high-flux, anti-fouling membrane with VOC capture ability using ZIF-8 [5].

Materials:

- ZIF-8 variants (ZIF-8-1, ZIF-8-2, ZIF-8-3) with different phase compositions [5]

- Polypropylene or PVDF membrane substrate

- Coconut oil-derived fatty acids for surface modification [6]

- Thermally induced phase separation (TIPS) equipment

Fabrication Steps:

- Membrane Modification:

ZIF-8 Incorporation:

Performance Validation:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Membrane Distillation Crystallization Research

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene Hollow-fiber Membranes | Commercial tubular module (MD3126), 0.068 m² effective area [1] | Primary separation material for VMD | Hydrophobic, pore size 0.2-0.45 μm |

| Acetic Acid (HAc) | Laboratory grade, 0.1-0.5% solutions, pH ~2 [1] | Carbonate scale removal | Superior efficacy for CaCO₃ scaling |

| ZIF-8 Variants | Mixed phases (cubic I-43m, monoclinic Cm, triclinic R3m) [5] | Anti-fouling membrane fabrication | ZIF-8-2 shows optimal VOC capture and stability |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | 1 M stock solution, filtered (0.22 μm) [6] | Synthetic scaling solution preparation | Simulates brackish water conditions |

| Monoethanolamine (MEA) | 30 wt% solution in water [6] | CO₂ capture fluid for carbon mineralization studies | Used in MDC for carbonate production |

| Coconut Oil-derived Fatty Acids | 4 wt% solution in appropriate solvent [6] | Membrane surface modification | Enhances hydrophobicity and fouling resistance |

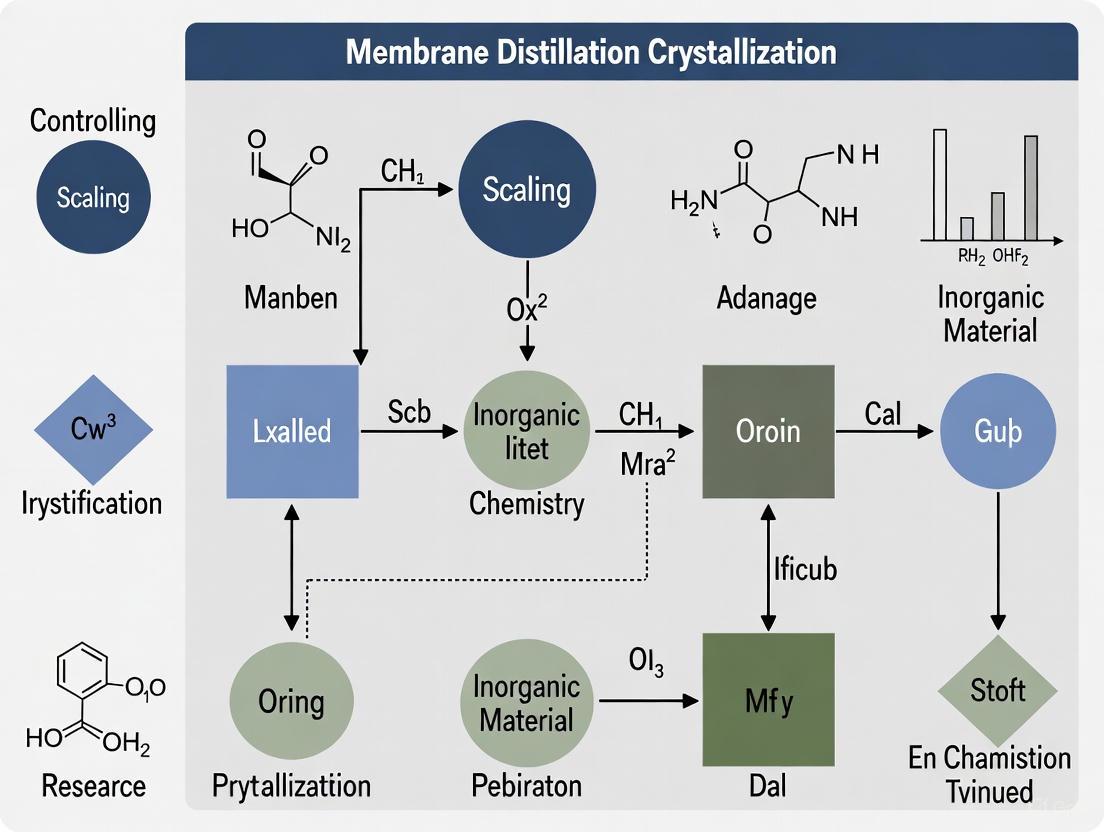

Visualization of Scaling Mechanisms and Processes

Diagram 1: Membrane Scaling Mechanism Pathway

Diagram 2: Integrated MDC Experimental Workflow

Advanced Technical Solutions

FAQ 4: How can I control crystal polymorphism and size distribution in MDC?

Answer: Crystal characteristics in Membrane Distillation-Crystallization are influenced by multiple parameters that can be precisely controlled [7]:

Key Control Parameters:

- Supersaturation Rate: Controlled by evaporation rate and temperature

Process Configuration:

Crystallization Duration:

Experimental Optimization Approach:

- Use response surface methodology to model parameter interactions

- Implement real-time monitoring with focused beam reflectance measurement (FBRM)

- Control polymorphism through selective antiscalant addition

FAQ 5: What innovative membrane materials show promise for fouling mitigation?

Answer: Recent advances in membrane materials focus on surface modification and nanocomposite structures:

ZIF-8 Omniphobic Membranes:

- Composition: 92% ZIF-8 loading achieved via TIPS-HoP technique [5]

- Performance: Normalized flux of 71.8 L m⁻² h⁻¹ bar⁻¹, outperforming conventional membranes by fivefold [5]

- Durability: Processes >38,000 L of water with 10 ppm contaminants per m² without reactivation [5]

- Anti-fouling: Excellent cyclic stability over 900 hours with high anti-fouling properties [5]

Surface-Modified PVDF Membranes:

- Modification Process: Plasma cleaning → fatty acid coating → thermal curing [6]

- Mechanism: Lower surface energy and greater roughness promote mineralization with up to 20% greater vapor flux [6]

- Wetting Tolerance: Lower operating temperature improves membrane wetting tolerance by 96.2% [6]

Implementation Considerations:

- Balance between vapor flux and anti-fouling properties

- Long-term stability under high salinity conditions

- Scalability of fabrication processes for industrial application

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are concentration polarization (CP) and temperature polarization (TP), and how do they drive scaling in MDCr?

Answer: In Membrane Distillation Crystallization (MDCr), concentration polarization (CP) refers to the phenomenon where the concentration of dissolved salts at the membrane surface becomes higher than in the bulk feed solution. Simultaneously, temperature polarization (TP) describes the effect where the temperature at the membrane surface differs from the bulk temperature [8] [9]. These phenomena are fundamental drivers of scaling for two primary reasons:

- Creation of a Supersaturated Zone: CP creates a localized zone of high concentration at the membrane interface. This can rapidly push the solution into a supersaturated state, triggering the nucleation and growth of inorganic crystals directly on the membrane surface [9].

- Reduction of Driving Force: TP reduces the effective temperature difference across the membrane, which is the primary driving force for vapor transport. This leads to a lower permeate flux. The combined effect of CP and TP significantly diminishes the vapor pressure gradient, making the process less efficient and accelerating scaling by concentrating solutes at the membrane boundary layer [8] [10].

FAQ 2: What is the quantitative impact of TP on system performance?

Answer: The impact of Temperature Polarization is often quantified using the Temperature Polarization Coefficient (TPC or τ). The value of TPC ranges from 0 to 1, where a value closer to 1 indicates less severe polarization. Research shows that the design of the flow channel significantly impacts the TPC. For instance, in Direct Contact Membrane Distillation (DCMD), the TPC for channels with spacers falls in a higher range of 0.9–0.97, whereas for flow channels without spacers, the TPC was in the lower range of 0.57–0.76 [8]. This demonstrates that inadequate system design can lead to a over 40% reduction in the effective thermal driving force.

FAQ 3: How does scaling, once initiated, further degrade MDCr performance?

Answer: Scaling sets off a detrimental cycle that severely impacts performance [9]:

- Flux Decline: The formation of a dense crystalline layer on the membrane surface physically blocks vapor pathways, leading to a progressive and often severe reduction in permeate flux.

- Induced Membrane Wetting: Crystal growth, particularly inside membrane pores, can compromise the membrane's hydrophobicity. This allows the liquid feed to penetrate the pores, leading to membrane wetting and a catastrophic failure of salt rejection [11] [9].

- Exacerbated Polarization: The scale layer acts as an insulating barrier, further worsening both temperature and concentration polarization, which in turn accelerates further scaling.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Rapid Decline in Permeate Flux and Signs of Scaling

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid, steady flux decline | Severe concentration polarization leading to surface scaling | Analyze feed chemistry for scaling precursors (e.g., CaSO₄, CaCO₃). Inspect membrane surface via SEM-EDS for crystals [12]. | Increase cross-flow velocity. Introduce turbulence promoters (spacers). Optimize feed temperature to reduce supersaturation at the membrane. |

| Flux decline with high permeate conductivity | Scaling-induced membrane wetting | Measure permeate conductivity. Perform a post-mortem membrane analysis to check for pore intrusion by crystals [11] [12]. | Implement a robust membrane cleaning protocol (e.g., mild acid wash for carbonate scales). Consider using membranes with enhanced anti-wetting properties. |

| Lower-than-expected flux from theoretical values | Significant temperature polarization | Measure bulk and near-membrane surface temperatures to calculate the TPC [13] [10]. | Enhance heat transfer by increasing feed flow rate (improves TPC from ~0.57 to ~0.9+) [8]. Use spacers to disrupt boundary layers. |

Issue: Uncontrolled Crystallization and Poor Crystal Quality

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine crystals forming in bulk; excessive scaling on membrane | Homogeneous nucleation dominant over heterogeneous nucleation | Monitor crystal size distribution (CSD). Observe if fine crystals are circulating in the feed tank [11]. | Implement heterogeneous seeding. Add inert seeds (e.g., SiO₂) to provide preferential nucleation sites in the bulk, shifting crystallization away from the membrane [11]. |

| Wide crystal size distribution (CSD) | Fluctuating supersaturation levels at the membrane interface | Track induction time and measure CSD of produced crystals over time [14]. | Use seeding to control nucleation. One study found seeding with 0.1 g L⁻¹ SiO₂ shifted the mean crystal size from 50.6 µm (unseeded) to a coarse 230–340 µm [11]. Optimize operating conditions (feed temperature, flow rate) for stable supersaturation control [14]. |

Summarized Quantitative Data

Table 1: Experimentally Measured Temperature Polarization Coefficients (TPC) in Different System Configurations

| MD Configuration | Flow Channel Type | Temperature Polarization Coefficient (TPC) Range | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCMD [8] | With Spacers | 0.9 – 0.97 | Spacers significantly mitigate TP by enhancing turbulence and disrupting the boundary layer. |

| DCMD [8] | Without Spacers | 0.57 – 0.76 | The absence of spacers results in a much more severe TP, drastically reducing driving force. |

Table 2: Impact of Seeding on MDCr Performance for Hypersaline Feed (300 g L⁻¹ NaCl) [11]

| Parameter | Unseeded Performance | Seeded Performance (0.1 g L⁻¹ SiO₂) | Impact of Seeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-state Permeate Flux | Baseline | Increased by 41% | Seeding suppresses scaling and polarization, maintaining a higher driving force. |

| Salt Rejection | < 99.99% (wetting) | ≥ 99.99% | Effective wetting suppression by preventing scale formation on and in the membrane. |

| Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) | Fine (Mean: 50.6 µm) | Coarse (Mean: 230–340 µm) | Seeding shifts crystallization to the bulk, producing larger, more uniform crystals. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct Measurement of Temperature Polarization

Objective: To quantitatively measure the Temperature Polarization Coefficient (TPC) in a lab-scale Air Gap MD (AGMD) system [13].

Materials:

- Lab-scale AGMD module with a flat-sheet PTFE membrane.

- Thermocouples (e.g., micro-thermocouples TT-T-30) or thermal resistors.

- Temperature scanner/data logger.

- Feed reservoir and circulation pump.

- Flow meter and temperature control systems.

Workflow:

- Sensor Placement: Install thermocouples at critical locations: in the bulk feed stream, in the bulk coolant stream, and as close as possible to the hot and cold membrane surfaces within the module.

- System Operation: Circulate the feed solution (e.g., 35 g/L NaCl) and coolant at set temperatures and flow rates until steady state is reached.

- Data Collection: Record the temperatures simultaneously from all sensors: bulk feed (

T_b1), bulk coolant (T_b2), membrane surface on feed side (T_m1), and membrane surface on coolant side (T_m2). - Calculation: Compute the TPC (τ) using the formula: τ = (Tm1 - Tm2) / (Tb1 - Tb2) [13] [10].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Seeding as a Mitigation Strategy for Scaling and Polarization

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of inert seeding particles in mitigating concentration polarization, suppressing membrane scaling, and controlling crystal growth [11].

Materials:

- MDCr setup (e.g., AGMD configuration).

- Hydrophobic membrane (e.g., Polypropylene (PP) or Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)).

- Inert seed particles (e.g., SiO₂, purity >99%), sized 30–60 µm.

- Hypersaline feed solution (e.g., 300 g L⁻¹ NaCl).

- Analytical balance to measure permeate flux.

- Conductivity meter to measure salt rejection.

- Equipment for Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) analysis.

Workflow:

- Baseline Experiment: Run the MDCr system with the hypersaline feed under set operating conditions (e.g., feed temperature of 53°C, specific flow rate) without any seeds. Monitor permeate flux, salt rejection, and collect formed crystals for CSD analysis.

- Seeded Experiment: Disperse a precise concentration (e.g., 0.1 g L⁻¹) of SiO₂ seeds directly into the feed reservoir. Maintain the same operating conditions as the baseline run.

- Performance Monitoring: Recirculate the seeded feed and monitor the steady-state permeate flux and salt rejection over time.

- Product Analysis: At the end of the experiment, analyze the crystals recovered from the crystallizer or sedimentation tank to determine the Crystal Size Distribution (CSD).

- Comparison: Compare the flux stability, salt rejection, and CSD between the seeded and unseeded experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Investigating Polarization and Scaling in MDCr

| Item | Function / Role in Research | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) Membrane | A common hydrophobic membrane used to study baseline performance and its susceptibility to scaling and wetting. | [11] |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) Membrane | A membrane known for its high hydrophobicity and chemical resistance. Often demonstrates higher flux (e.g., 47% higher than PP) due to lower thermal resistance, useful for comparative studies. | [11] |

| SiO₂ Seed Particles (30–60 µm) | Inert, heterogeneous nucleation sites. When dosed optimally (e.g., 0.1 g L⁻¹), they shift crystallization to the bulk solution, mitigating membrane scaling and improving flux stability. | [11] |

| PVDF-based Membrane | Another common hydrophobic membrane material, often used in vacuum MD (VMD) studies for treating complex waters like mine drainage. | [12] |

| Micro-thermocouples | Essential sensors for direct measurement of temperature profiles near the membrane surface, enabling the calculation of the Temperature Polarization Coefficient (TPC). | [13] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Membrane Wetting

This guide helps researchers diagnose and address common membrane wetting issues in Membrane Distillation-Crystallization (MDCr) experiments.

Q1: Why has the electrical conductivity of my permeate suddenly increased?

A sudden increase in permeate conductivity is a primary indicator of membrane wetting, where liquid feed, rather than just vapor, penetrates the membrane pores [15].

- Problem: Membrane pore wetting is occurring.

- Immediate Action:

- Cease the experiment immediately to prevent irreversible membrane damage.

- Check the Liquid Entry Pressure (LEP): Ensure the transmembrane hydrostatic pressure is well below the membrane's LEP. The LEP is influenced by membrane pore size, hydrophobicity, and feed surface tension [15].

- Inspect for scaling: Inorganic scaling (e.g., from calcium, magnesium, or silica) is a major cause of wetting. Scaling can create hydrophilic pathways for the feed solution to enter pores [15].

- Long-Term Solution:

Q2: My permeate flux is declining, but the conductivity remains low. Is this wetting?

A flux decline with stable permeate quality typically indicates fouling or scaling that has not yet progressed to full wetting [15].

- Problem: Scale-induced pore blockage or surface fouling.

- Immediate Action:

- Analyze the fouling type: This could be a precursor to wetting. The blocking filtration model describes several mechanisms [17]:

- Complete Blocking: Each foulant particle completely seals a membrane pore.

- Standard Blocking: Small particles deposit on the pore walls, gradually constricting them.

- Intermediate Blocking: Particles may deposit on other particles already on the membrane.

- Cake Filtration: A layer of particles forms on the membrane surface.

- Evaluate operating conditions: High recovery rates lead to excessive concentration of solutes near the membrane surface, accelerating scaling [16].

- Analyze the fouling type: This could be a precursor to wetting. The blocking filtration model describes several mechanisms [17]:

- Long-Term Solution:

Q3: How can I detect membrane wetting at its earliest stages?

Early detection allows for corrective action before permeate quality is compromised.

- Problem: Standard methods (permeate conductivity) only detect wetting after it has occurred.

- Solution: Implement early detection monitoring.

- Streaming Current Monitoring: A novel approach detects electrokinetic leakage through wetted pores by measuring the tangential streaming current, revealing wetting kinetics before it affects permeate quality [18].

- Monitor Normalized Flux: Track permeate flux under standardized conditions to distinguish between typical fouling and the onset of wetting-related performance loss [15].

FAQs on Membrane Wetting and Scaling in MDCr

Q: What are the fundamental causes of membrane wetting in MDCr?

The primary causes are:

- Exceeding Liquid Entry Pressure (LEP): Transmembrane hydrostatic pressure surpassing the membrane's pressure threshold [15].

- Membrane Fouling and Scaling: Inorganic scaling (e.g., CaCO₃, CaSO₄) and organic fouling can compromise membrane hydrophobicity, facilitating pore wetting [15].

- Surfactants & Chemical Attack: Surfactants in the feed solution lower surface tension, reducing LEP. Oxidizing agents like chlorine can degrade membrane polymers [15] [19].

- Membrane Damage: Physical deterioration or chemical degradation over time reduces membrane integrity [15].

Q: Can a wetted membrane be restored, or does it need replacement?

Membrane restoration is challenging and often not fully effective [15].

- Cleaning: A wetted membrane must be thoroughly dried and cleaned. However, cleaning agents can themselves be harsh and potentially damage the membrane with repeated use [15].

- Replacement: In many cases, especially with severe or irreversible wetting, membrane replacement is the most reliable solution to restore original performance and permeate quality [15] [19].

Q: How does the MD configuration (e.g., AGMD, DCMD, VMD) influence wetting?

While feed conditions are often the dominant factor, configuration matters.

- Vacuum MD (VMD) requires particular attention because the applied vacuum on the permeate side increases the transmembrane vapor pressure difference, which can elevate the risk of wetting compared to other configurations [15].

- Air Gap MD (AGMD) can benefit from strategies like heterogeneous seeding, which has been shown to significantly enhance flux stability and wetting resistance [11].

Experimental Protocols for Wetting Mitigation and Control

Protocol 1: Heterogeneous Seeding to Mitigate Scaling and Wetting

This protocol is based on research demonstrating that SiO₂ seeding in AGMDCr can shift crystallization to the bulk solution, suppressing scale formation on the membrane [11].

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for mitigating wetting through heterogeneous seeding.

Detailed Methodology:

- Feed Solution Preparation: Prepare a sodium chloride (NaCl) feed solution at a high concentration (e.g., 300 g/L) to simulate hypersaline conditions [11].

- Seed Addition: Disperse inert silicon dioxide (SiO₂) seed particles directly into the feed vessel. A concentration of 0.1 g/L has been shown to be effective. Size fractions between 30-60 µm are typical [11].

- System Operation: Operate an Air-Gap MD (AGMD) system in batch recirculation mode. Example operating conditions:

- Feed Inlet Temperature: 53 ± 0.5 °C

- Coolant Temperature: 20 ± 1.5 °C

- Feed Flow Rate: 95 L/h [11].

- Performance Monitoring: Continuously record:

- Permeate Flux: To assess flux stability.

- Permeate Conductivity: To confirm salt rejection ≥ 99.99% and detect wetting.

- Crystal Size Distribution (CSD): Seeding should shift the CSD from fine crystals (unseeded, ~50 µm) to coarser crystals (seeded, 230-340 µm) [11].

Protocol 2: Early Wetting Detection via Streaming Current Monitoring

This protocol provides a method for detecting the very onset of membrane wetting before it is visible through permeate quality changes [18].

Detailed Methodology:

- Apparatus Setup: Integrate a streaming current measurement device with the MD membrane cell to apply a tangential flow and measure the induced streaming current.

- Experiment Execution: Circulate a surfactant solution (e.g., Tween 20 at concentrations of 0.0005 – 0.07 mM) to induce controlled wetting on a hydrophobic PVDF membrane.

- Data Collection: Monitor the streaming current over time. An increasing streaming current signal indicates the onset of electrokinetic leakage, signifying initial pore wetting [18].

- Analysis: Correlate the kinetics of the streaming current increase with the degree of membrane wetting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Essential materials for investigating and mitigating wetting in MDCr.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PTFE Membrane | High hydrophobicity provides superior wetting resistance and higher LEP [15] [11]. | Often exhibits higher permeate flux compared to PP due to lower thermal resistance and optimized structure [11]. |

| PP Membrane | Common, commercially available hydrophobic membrane for MD [11]. | A standard material for baseline studies and comparison. |

| SiO₂ Seed Particles | Inert heterogeneous nucleants to induce crystallization in bulk solution, mitigating membrane scaling and wetting [11]. | Optimal concentration is critical (~0.1 g/L). High doses (e.g., 0.6 g/L) can cause flux decline due to hindered flow [11]. |

| Antiscalants | Chemicals injected into feed water to delay the precipitation of scaling salts (e.g., CaCO₃, CaSO₄) [16]. | Dosage is typically 2-5 ppm. Provides a finite delay in scale formation; systems should be flushed at shutdown [16]. |

| Tween 20 Surfactant | Used in controlled experiments to study wetting mechanisms by reducing feed solution surface tension [18]. | Useful for fundamental research on wetting kinetics and testing early detection methods [18]. |

Table 2: Quantitative effects of SiO₂ seeding on AGMDCr performance (Feed: 300 g/L NaCl). [11]

| Parameter | Unseeded Performance | Seeded Performance (0.1 g/L SiO₂) | Impact & Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State Permeate Flux | Baseline | Increased by 41% | Seeding mitigates scaling, maintaining higher vapor gap pathways. |

| Salt Rejection | < 99.99% (if wetted) | ≥ 99.99% | Effective wetting suppression, preserving permeate quality. |

| Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) | Fine crystals (Mean: ~50.6 µm) | Coarse crystals (Mean: 230-340 µm) | Seeding shifts nucleation from the membrane (primary) to bulk solution (on seeds). |

| Flux at High Seed Dose | Baseline | Decrease at 0.6 g/L | Excessive seed concentration can cause near-wall solids holdup and hinder transport. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common types of scale in membrane distillation and crystallization processes? The most prevalent scalants that impede membrane performance are calcium sulfate, calcium carbonate, and silica [20]. These inorganic minerals precipitate from feed solutions when their concentration exceeds solubility limits, often due to the concentration and temperature polarization effects at the membrane surface [9] [21]. Calcium sulfate scaling is particularly challenging as its formation is difficult to inhibit through pH adjustment alone [22].

2. How does scaling lead to membrane wetting and failure? Scaling can cause both membrane wetting and irreversible structural damage [22]. Growing crystals exert crystallization pressure on membrane structures [22]. This pressure can initially stretch and subsequently compress the membrane, potentially leading to a loss of hydrophobicity, pore wetting, and a catastrophic decline in permeate quality as non-volatile salts pass through the membrane [21] [22].

3. What is the fundamental mechanism by which antiscalants work? Antiscalants primarily function through two mechanisms: threshold inhibition and crystal modification [23]. Threshold inhibition interferes with the precipitation of scale-forming ions, delaying crystallization. Crystal modification alters the shape and size of crystals that do form, preventing them from adhering to surfaces and keeping them suspended in the bulk solution [20] [23].

4. Can membrane surface properties themselves mitigate scaling? Yes, innovative membrane design is a promising approach to mitigate scaling [9]. Tailoring surface morphology, roughness, hydrophobicity, and surface charge can create a higher energetic barrier for nucleation and crystal adhesion [9] [22]. For instance, surfaces with multiscale roughness can enhance turbulence and reduce polarization effects [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapid Permeate Flux Decline Due to Calcium Sulfate Scaling

- Symptoms: A sharp, significant drop in vapor flux occurs during operation. Visual inspection or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals gypsum (CaSO₄·2H₂O) crystals on the membrane surface [21] [22].

- Underlying Mechanism: The feed solution achieves a high degree of supersaturation, leading to rapid nucleation and growth of calcium sulfate crystals that block membrane pores [22] [24]. The driving force is the elevated supersaturation, which exerts high crystallization pressure on the membrane structures [22].

- Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Setup: Use a direct-contact membrane distillation (DCMD) unit with an effective membrane area of ~34 cm² [22].

- Feed Solution: Prepare a 0.01 M CaSO₄ solution [21].

- Operation: Conduct a long-term test, monitoring the permeate flux and the volume concentration factor (VCF) over time [21].

- Characterization:

- Solutions:

- Introduce a CNT-based Spacer: Employ a 3D-printed carbon nanotube (CNT) spacer. Its multiscale roughness promotes turbulence, reduces polarization, and facilitates nuclei detachment from the membrane surface, allowing crystals to grow in the bulk solution instead [21].

- Optimize Antiscalant Dosing: Inject a phosphonate- or polymer-based antiscalant. The typical dosing range is 0.5–4 mg/L, but the exact dosage should be determined using simulation software based on specific water chemistry [25] [23].

- Control Concentration Rate: Operate at a lower initial vapor flux to reduce the rate at which supersaturation is achieved, thereby lowering the maximum crystallization pressure exerted on the membrane [22].

Problem 2: Scaling and Flux Reduction from Calcium Carbonate and Silica

- Symptoms: A gradual decline in permeate flux. Calcium carbonate scale has a high thermal conductivity, significantly impairing heat transfer efficiency [20]. Silica scale forms in high-temperature processes and also hinders heat transfer due to its low thermal conductivity [20].

- Underlying Mechanism: Calcium carbonate precipitates when calcium and carbonate ions combine to form insoluble crystals [20]. Silica scaling involves the polymerization of silicic acid into amorphous silica deposits [20] [25].

- Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Water Analysis: Perform a complete chemical analysis of the feed water to determine the concentration of calcium, carbonate, and silica [25].

- Saturation Analysis: Use predictive software (e.g., Veolia's Argo Analyzer) to calculate the saturation indices (e.g., Langelier Saturation Index for CaCO₃) and predict scaling potential [25].

- Autopsy: A membrane post-mortem analysis involving SEM and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) can confirm the composition of the scale layer.

- Solutions:

- Use Silica-Specific Antiscalants: Apply polymeric or blended antiscalants formulated to be effective against a broad range of scales, including silica and calcium carbonate [25] [23]. These work by dispersing particles and reducing their tendency to precipitate [20].

- Pre-treatment: Consider implementing softening to remove calcium ions or using a reverse osmosis pre-treatment step to reduce the overall dissolved solids load before the MD process.

Problem 3: Scaling-Induced Membrane Wetting

- Symptoms: A sustained increase in the electrical conductivity of the distillate, indicating that the hydrophobic membrane has been wetted and non-volatile salts are passing through [21] [22].

- Underlying Mechanism: Scale formation on the membrane surface can compromise its hydrophobicity in two ways: 1) crystals physically bridging the pore openings, or 2) scaling-induced structural damage that permanently alters the membrane's properties [21] [22].

- Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

- In-situ Monitoring: Continuously monitor the electrical conductivity of the permeate during the MD experiment. A sharp, sustained increase is a direct indicator of wetting [22].

- Contact Angle Measurement: Measure the contact angle of the membrane before and after scaling experiments. A significant decrease indicates a loss of hydrophobicity [9].

- Liquid Entry Pressure (LEP) Test: Measure the LEP of the membrane after scaling. A decrease in LEP confirms that the membrane is more susceptible to wetting [21].

- Solutions:

- Apply Surface Functionalization: Engineer membrane surfaces with enhanced hydrophobicity or "slippery" characteristics to create a higher energetic barrier for nucleation and crystal adhesion [9] [22].

- Mitigate Scaling at Onset: The most effective strategy is to prevent scale formation initially by implementing the antiscalant and operational controls described above, as wetting is often a consequence of severe scaling.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data for scalants and mitigation performance from the literature.

Table 1: Scaling Thresholds and Induction Parameters for Primary Scalants

| Scalant | Common Form | Key Influencing Factor | Reported Induction Time / Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Sulfate | Gypsum (CaSO₄·2H₂O) | Concentration Rate & Temperature | Flux can be completely lost at VCF ~2.4 without mitigation [21]. Higher supersaturation achieved by faster concentration rates exerts higher crystallization pressure [22]. |

| Calcium Carbonate | CaCO₃ | pH | A primary scalant; controlled effectively by pH adjustment [20] [22]. |

| Silica | SiO₂ | pH, Temperature | Forms in high-temperature processes; low thermal conductivity severely hinders heat transfer [20]. |

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Scaling Mitigation Strategies

| Mitigation Strategy | Experimental Conditions | Performance Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNT Spacer | DCMD, 0.01 M CaSO₄, 60°C | 37% flux reduction at VCF >4; maintained 29 LMH vs. complete flux loss in controls before VCF 3.5 [21]. | [21] |

| Antiscalant Dosing | RO/MD, various feedwaters | Typical dosing range of 0.5 - 4 mg/L. Enables systems to run at higher recovery rates [25] [23]. | [25] [23] |

| Surface-Modified PTFE Membrane | MDC, 30 wt% MEA, CO₂-loaded | Lower surface energy & greater roughness led to ~20% greater vapor flux and improved mineralization rates [6]. | [6] |

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Scaling Mechanism and Control Pathway

Experimental Workflow for MD Scaling Study

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Scaling Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Spacers | Turbulence promoter to reduce boundary layers and polarization effects. Mitigates scaling by promoting crystal detachment from the membrane surface [21]. | 3D-printed spacers with multiscale surface roughness [21]. |

| Phosphonate-based Antiscalants | Effective threshold inhibitors for common scales like calcium carbonate and calcium sulfate [23]. | e.g., Hypersperse*; suitable for a range of feedwaters [25]. |

| Polymeric & Blended Antiscalants | Target complex and mixed scales, including high silica levels. Function via crystal modification and dispersion [25] [23]. | Ideal for challenging feedwaters with multiple scalants [25]. |

| Hydrophobic Membrane Materials | The core separation element in MD. PTFE and PVDF are common, with PTFE generally offering higher hydrophobicity and vapor flux [6]. | Commercial PTFE (0.45 μm) or surface-modified PVDF membranes [6]. |

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Non-invasive, in-situ tool for real-time visualization and quantitative measurement of scaling layer formation on membrane surfaces [21]. | Critical for elucidating dynamic scaling mechanisms without interrupting experiments [21]. |

| Model Scalant Solutions | Used in controlled experiments to study the fundamental behavior of specific scalants. | 0.01 M CaSO₄ for studying gypsum scaling [21]. |

In membrane distillation crystallization (MDC), mastering the crystallization zones is fundamental to controlling scaling, optimizing crystal product quality, and ensuring stable process operation. MDC is a hybrid thermal technology that integrates membrane distillation (MD) with a crystallization reactor, designed to achieve simultaneous recovery of fresh water and valuable minerals from highly concentrated solutions [26] [3]. The process hinges on concentrating a feed solution via MD until it reaches a supersaturated state, which is the prerequisite for initiating crystallization in the subsequent reactor [26] [3].

Crystallization from a solution can only occur by bringing the solution into a state of supersaturation, typically achieved by cooling the solution or evaporating the solvent [26]. This journey from an undersaturated to a supersaturated state navigates three critical zones, each defined by the relationship between solute concentration and its solubility: the Stable Zone, the Metastable Zone, and the Unstable Zone [26]. Understanding and controlling these zones is the key to mitigating membrane scaling and producing crystals with desired characteristics, such as narrow size distribution, high purity, and specific morphology [26] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between solution concentration, solubility, and these three crucial zones, providing a map for process control.

Fundamental FAQs on Crystallization Zones

1. What are the stable, metastable, and unstable zones in the context of MDC?

In MDC, the solution's state is defined relative to its saturation point:

- Stable Zone (Undersaturated): The solution concentration is below its solubility limit. In this zone, no crystal formation occurs, and existing crystals will dissolve. The MD process operates safely within this zone during initial concentration phases without risk of membrane scaling [26].

- Metastable Zone: The solution is supersaturated (concentration exceeds the solubility limit) but primary nucleation does not occur spontaneously. This zone is critical for control; crystal growth can proceed on existing seeds, but the formation of new crystals is unlikely unless the system is perturbed. The width of this zone is a key process parameter [26].

- Unstable Zone (Labile Zone): The solution is highly supersaturated. In this zone, primary nucleation occurs spontaneously and homogeneously, leading to the rapid formation of new crystals. Operating in this zone poses a high risk of uncontrolled scaling on the membrane surface and equipment [26].

2. Why is the metastable zone critical for controlling scaling in MD membranes?

Scaling, the precipitation of salts on the membrane surface, is a major technical challenge in MDC that leads to flux reduction, membrane wetting, and process failure [26] [28] [3]. The metastable zone is the operational buffer that separates safe concentration levels from the dangerous conditions that trigger massive, uncontrolled scaling.

By carefully controlling the MD process to keep the bulk concentrate within the metastable zone, operators can promote crystal growth in the dedicated crystallizer while minimizing heterogeneous nucleation directly on the membrane surface [26] [29]. Nucleation is favored at the membrane-solution interface because the Gibbs free energy is lower there, making it easier for crystals to form [3]. Therefore, preventing the solution from entering the unstable zone at the membrane interface is the primary defense against scaling.

3. How does supersaturation control in MDC differ from conventional crystallization?

In conventional evaporative crystallization, controlling supersaturation is challenging due to poor control over the evaporation rate [29]. MDC offers a distinct advantage because the membrane area and operating conditions (like temperature and flow rate) provide fine-grained control over the rate of solvent removal.

This allows researchers to manipulate the supersaturation rate and position the system within specific regions of the metastable zone [29]. For instance, a higher concentration rate shortens the induction time and raises the supersaturation at which nucleation occurs, which can favor a homogeneous primary nucleation pathway in the bulk solution over heterogeneous nucleation on the membrane [29]. This facile control is unique to MDC and is key to regulating the competition between nucleation and crystal growth mechanisms [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: Scaling and Process Control

This guide addresses common operational problems related to crystallization zone management in MDC systems.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common MDC Issues

| Problem Observed | Likely Cause (Related Zone) | Immediate Corrective Actions | Long-Term Preventive Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Flux Decline & Membrane Scaling | Operation drifting into the Unstable Zone, causing rapid nucleation and scale formation on the membrane surface [26] [28]. | 1. Reduce feed temperature to lower evaporation rate [28]. 2. Dilute the feed stream to return to the Stable Zone. | 1. Optimize membrane area and flow rate to control supersaturation rate [29]. 2. Use an anti-scalant (e.g., at 0.5 mg/L) to inhibit crystal nucleation and growth [28]. |

| Poor Crystal Yield | Operation confined to the Metastable Zone without reaching sufficient supersaturation to trigger nucleation in the crystallizer [26]. | 1. Increase feed temperature to enhance solvent evaporation. 2. Extend process operation time. | 1. Implement seeding to induce secondary nucleation in the metastable zone [27]. 2. Use sonication to provide the energy to overcome the nucleation barrier [27]. |

| Broad Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) | Uncontrolled nucleation in the Unstable Zone, leading to multiple nucleation events over time [26] [27]. | Difficult to correct once distribution is set. Focus on prevention in the next cycle. | 1. Improve supersaturation control to remain in a specific region of the Metastable Zone [29]. 2. Use controlled methods like sonocrystallization or seeding to generate uniform nuclei [27]. |

| Membrane Wetting | Severe scaling or crystal intrusion that compromises membrane hydrophobicity, often from operation in the Unstable Zone [3] [30]. | 1. Immediate system shutdown. 2. Perform chemical cleaning (e.g., with vinegar for CaCO₃) [28]. | 1. Adopt an intermittent operation with a flushing shutdown protocol (P3) to remove concentrated brine [30]. 2. Prevent scaling through the strategies above. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping the Metastable Zone Width (MZWD) in an MDC System

The Metastable Zone Width is a critical parameter that defines the maximum supersaturation a solution can tolerate before nucleation occurs. Determining it is essential for designing a stable MDC process [26].

Objective: To experimentally determine the MZWD for a specific feed solution (e.g., seawater, RO brine) in your MDC setup.

Materials:

- Lab-scale MD system (e.g., DCMD or AGMD configuration)

- Crystallizer vessel with agitator

- In-line concentration or conductivity meter

- Temperature control system

- Laser turbidimeter or particle counter (for detecting nucleation)

Methodology:

- Saturation: Prepare a known volume of feed solution and recirculate it through the MD system until it reaches saturation, indicated by a stable conductivity reading.

- Controlled Concentration: Continue the MD process at a constant feed temperature and flow rate. Monitor the concentration in the crystallizer in real-time.

- Nucleation Detection: The moment a sustained increase in turbidity or particle count is detected in the crystallizer, record the current solution concentration and temperature. This point marks the boundary between the metastable and unstable zones.

- Data Analysis: The MZWD is the difference between the concentration at nucleation and the equilibrium saturation concentration at the same temperature. Repeat at different temperatures to characterize the zone fully.

Protocol 2: Supersaturation Control via Membrane Area Manipulation

This protocol, derived from recent research, uses membrane area as a lever to fine-tune supersaturation, thereby regulating nucleation and crystal growth without altering mass and heat transfer dynamics [29].

Objective: To regulate crystal nucleation and growth by adjusting the effective membrane area to control the rate of supersaturation generation.

Materials:

- MD system with a modular or valvable membrane array.

- Crystallizer with temperature control.

- Real-time concentration monitoring.

- In-line filtration (e.g., mesh filter) for crystal retention in the crystallizer.

Workflow: The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow for this protocol.

Methodology:

- System Setup: Start with a saturated solution in the crystallizer. Configure the MD system to operate at a fixed initial membrane area.

- Process Operation & Monitoring: Begin the MD concentration process. Continuously monitor the supersaturation level in the crystallizer.

- Area Modulation: If the supersaturation is rising too quickly towards the unstable zone, reduce the active membrane area to slow the concentration rate. Conversely, to increase yield, the area can be increased to push the system closer to the metastable limit.

- Nucleation & Growth: Once nucleation is induced (detected by turbidity), the membrane area can be further modulated to maintain a constant supersaturation within the metastable zone, favoring crystal growth over further nucleation. The use of in-line filtration helps retain crystals in the crystallizer, preventing them from circulating back to the membrane module and causing scaling [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for MDC Crystallization Zone Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in MDC Research | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Membranes (e.g., LDPE, PVDF, PTFE) | Core component for solvent evaporation and solution concentration [26] [28]. | Hydrophobicity prevents liquid penetration, allowing only vapor transport. Membrane properties (pore size, porosity) directly impact flux and scaling propensity [3]. |

| Anti-Scalants | Chemicals added to feed solution to inhibit scale formation on the membrane [28]. | They extend the induction period for nucleation, effectively widening the metastable zone and allowing higher recovery without scaling [28]. |

| Seeding Crystals | Pre-formed crystals of the target compound added to the crystallizer [27]. | They provide surfaces for crystal growth in the metastable zone, suppressing the need for primary nucleation in the unstable zone and leading to more uniform crystal size distribution [27]. |

| Vinegar (Acetic Acid) | A mild, non-hazardous cleaning agent for membrane maintenance [28]. | Effectively dissolves CaCO₃-based scales. Its domestic availability makes it suitable for small-scale or remote operations [28]. |

| Sonication Probe | Device for inducing sonocrystallization [27]. | Ultrasound energy can induce nucleation in the metastable zone (sonocrystallization), providing a controlled method to generate uniform crystals with narrow size distribution [27]. |

Innovative Scaling Mitigation Strategies and Their Implementation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: What is the primary function of inert seeding particles in Membrane Distillation Crystallization (MDC)? Inert seeding particles serve as preferential nucleation sites in the bulk solution. This promotes heterogeneous crystallization of scale-forming minerals (such as CaSO₄ or NaCl) away from the membrane surface. By controlling where crystals form, they effectively mitigate membrane scaling and subsequent pore wetting, leading to more stable and prolonged MDC operation [31] [11] [32].

FAQ 2: How do I select the appropriate type of seed particle? The choice depends on the specific scalant and process requirements. Below is a summary of commonly used seeds:

| Seed Material | Target Scalant/Application | Key Properties & Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Gypsum (CaSO₄·2H₂O) | Calcium Sulfate (Gypsum) | Chemically identical to the scalant, providing highly compatible nucleation sites [31]. |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) | Sodium Chloride | Chemically stable, insoluble, low-cost, and globally available [11]. |

| Activated Alumina | Calcium Sulfate | Used in in-line granular filters, demonstrates high efficacy in scaling mitigation [32]. |

| Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) | Calcium Carbonate | Allows for easy separation of heterogeneous crystallization products from homogeneous ones via magnetic separation [33]. |

FAQ 3: What is the optimal seeding concentration, and what happens if I use too much? The optimal concentration is system-dependent, but studies have identified effective ranges. For gypsum seeds, a dose of 0.5 g/L was found to effectively control membrane fouling and wetting [31]. For SiO₂ seeds treating hypersaline NaCl solutions, a concentration of 0.1 g/L enhanced flux and suppressed wetting, while a higher dose of 0.6 g/L led to a flux decrease due to near-wall solids holdup and hindered transport [11]. Excessive seed loading can increase slurry viscosity, cause particle agglomeration, and potentially abrade the membrane.

FAQ 4: Why is my permeate flux still declining despite using seeds? A persistent flux decline indicates that bulk crystallization is not being fully controlled. This can be due to:

- Insufficient Seed Dose: The number of nucleation sites may be inadequate to handle the rate of supersaturation generation.

- Excessive Supersaturation: Very high saturation indices can promote homogeneous nucleation in the bulk solution, creating fine particles that can still deposit on the membrane [33].

- Seed Size and Properties: Seeds that are too small may not provide effective growth sites, while seeds with poor surface compatibility may not induce crystallization efficiently.

FAQ 5: How does seed size influence the crystallization process? Seed size directly impacts the crystal size distribution (CSD) of the product and the process hydrodynamics. The following table compares the outcomes from key studies:

| Study Context | Seed Material & Size | Observed Outcome on Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| Treating 300 g/L NaCl solution [11] | SiO₂, 30–60 µm | Shifted CSD from fine (mean 50.6 µm unseeded) to coarse (230–340 µm). |

| Water softening for CaCO₃ [33] | Magnetite, smaller vs. larger sizes | Smaller seed particle sizes promoted heterogeneous crystallization and better suppressed homogeneous crystallization. |

FAQ 6: Can heterogeneous seeding completely prevent membrane wetting? When applied correctly, yes, it can significantly control wetting. Research shows that introducing 0.5 g/L gypsum seeds effectively restricted membrane wetting, maintaining low permeate conductivity. Similarly, using 0.1 g/L SiO₂ seeds maintained salt rejection at ≥ 99.99% by suppressing scaling-induced wetting [31] [11]. The seeds work by preventing the formation of a continuous scaling layer that can grow into and through membrane pores.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem 1: Rapid Membrane Scaling and Wetting at High Recovery Rates

- Potential Cause: The supersaturation level at the membrane surface is too high, overwhelming the seeding-induced bulk crystallization mechanism.

- Solution:

- Integrate with Other Techniques: Combine seeding with microbubble aeration (MBA), which creates turbulence to reduce concentration polarization and can synergistically enhance bulk crystallization [31].

- Use an In-line Filter: Employ a granular filter (e.g., with activated alumina or sand) upstream of the MD module. This filter acts as an additional site for heterogeneous crystallization, capturing scale particles before they reach the membrane [32].

- Optimize Hydrodynamics: Consider using advanced feed spacers, such as 3D-printed carbon nanotube (CNT) spacers, which generate bubbly flow and enhance shear, detaching nuclei from the spacer surface and promoting their growth in the bulk solution [21].

Problem 2: Inconsistent Crystal Growth and Uncontrolled Crystal Size Distribution (CSD)

- Potential Cause: Competition between homogeneous nucleation (creating fine particles) and heterogeneous nucleation (on seeds) is not managed.

- Solution:

- Control Supersaturation: Operate at a lower saturation index (SI) where heterogeneous crystallization is preferentially promoted. A study on CaCO₃ found the highest suppression of homogeneous crystallization at an SI of about 1.01 [33].

- Optimize Seed Dosage and Size: Increase the seed dosage and use smaller seed particles to provide a larger total surface area for nucleation, thereby favoring heterogeneous over homogeneous crystallization [33].

Problem 3: Seed-Induced Abrasion or Fouling of the Membrane

- Potential Cause: The seeds themselves, or agglomerates of seeds and crystals, are physically depositing on or damaging the membrane.

- Solution:

- Ensure Proper Hydrodynamics: Maintain a sufficiently high cross-flow velocity to keep seeds in suspension and prevent their settlement on the membrane.

- Select Appropriate Seed Size: Avoid using seeds that are too large or have sharp edges.

- Use a Crystallizer: For continuous operation, implement an external crystallizer in the recirculation loop. This provides a dedicated, controlled environment for crystal growth, separating it from the membrane module [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Seeding with SiO₂ for Hypersaline Brine Treatment

This protocol is adapted from research on air-gap MDC (AGMDCr) for treating a 300 g L⁻¹ NaCl solution [11].

1. Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of SiO₂ seeds in mitigating membrane scaling and wetting, and in controlling crystal size distribution during MDC.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- MDC System: Bench-scale AGMD setup with a tubular membrane module.

- Membrane: Hydrophobic PTFE or PP tubular membrane.

- Feed Solution: Synthetic brine (300 g L⁻¹ NaCl in deionized water).

- Seed Material: Quartz sand (SiO₂, purity >99%), sieved to the 30–60 µm size fraction.

- Analytical Equipment: Conductivity meter for permeate quality, balance for permeate mass, SEM for membrane and crystal characterization.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: System Preparation. Clean the MD system and membrane. Prepare the synthetic feed brine and add it to the feed tank.

- Step 2: Seed Introduction. Disperse the SiO₂ seeds directly into the feed tank at a concentration of 0.1 g L⁻¹ before starting the MD system. Use recirculation to keep the seeds in suspension.

- Step 3: Experimental Run. Start the AGMDCr process with the following typical parameters:

- Feed Inlet Temperature: 53 ± 0.5 °C

- Coolant Temperature: 20 ± 1.5 °C

- Feed Flow Rate: 95 ± 5 L h⁻¹

- Operation Mode: Batch recirculation for 6 hours.

- Step 4: Data Monitoring.

- Record permeate flux every minute.

- Continuously monitor permeate conductivity.

- Monitor the feed concentration factor.

- Step 5: Post-experiment Analysis.

- Analyze the final crystal size distribution (CSD) from the feed/crystallizer.

- Examine the membrane surface for scaling via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

4. Expected Outcomes:

- With Seeds (0.1 g/L): A 41% enhancement in steady-state permeate flux compared to the unseeded experiment. Salt rejection maintained at ≥ 99.99%. A coarse crystal size distribution (230–340 µm) is obtained in the bulk [11].

- Without Seeds (Control): A finer crystal size distribution (mean ~50.6 µm) and a more significant flux decline due to membrane scaling.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials used in heterogeneous seeding experiments for MDC.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gypsum Seeds | Provides nucleation sites for calcium sulfate crystallization. | CaSO₄·2H₂O, 0.5 g/L dose. Used when the target scalant is gypsum itself [31]. |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) | Inert, heterogeneous nucleant for various salts. | Quartz sand, 30-60 µm, 0.1 g/L dose. Chemically stable and cost-effective [11]. |

| Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) | Magnetic seed for distinguishing and separating crystallization types. | Allows magnetic separation of heterogeneous crystals from homogeneous ones for quantitative analysis [33]. |

| Granular Activated Alumina | Filter media for in-line heterogeneous crystallization. | Used in a filter column; crystals form on the media surface, preventing them from reaching the membrane [32]. |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Spacer | Advanced spacer to promote turbulence and nucleation. | 3D-printed spacer that enhances bubble formation and reduces scaling on the membrane surface [21]. |

Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the comparative mechanism of membrane scaling with and without heterogeneous seeding.

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow and Seeding Mechanism in MDC

What is membrane distillation crystallization (MDCr) and why is scaling a problem? Membrane Distillation Crystallization (MDCr) is an advanced hybrid technology for treating hypersaline wastewater. It combines membrane distillation, which uses a hydrophobic membrane to separate water vapor from brine, with a crystallization step to recover both fresh water and valuable mineral crystals. This process is a key enabling technology for Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) systems. However, its performance is severely limited by membrane scaling, where inorganic salts crystallize directly on the membrane surface. This scaling blocks vapor pathways, reduces water flux, and can lead to membrane wetting, which allows liquid brine to contaminate the fresh water product [11] [3].

How does seeding help control scaling? Heterogeneous seeding is a promising strategy to control scaling. By adding inert seed particles like Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) to the hypersaline feed, you provide preferential nucleation sites for crystals to form in the bulk solution, rather than on the membrane surface. This shifts crystallization away from the membrane, mitigating scale formation and stabilizing long-term performance [11] [31] [34].

Key Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Seeding Experiments

| Item | Specification / Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Material | SiO₂ (Quartz Sand), >99% purity [11] | Chemically inert and insoluble; acts as a preferential nucleation site without altering brine chemistry. |

| Seed Sizes | 30–60 µm, 75–125 µm, 210–300 µm [11] | Different size fractions allow optimization for specific hydrodynamics and crystallization kinetics. |

| Membranes | Polypropylene (PP) or Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) hydrophobic membranes [11] | PTFE often shows higher flux; membrane choice influences thermal resistance and scaling propensity. |

| Hypersaline Feed | NaCl solution (e.g., 300 g L⁻¹) or synthetic brine [11] | Simulates real-world industrial brine or reverse osmosis (RO) concentrate for testing. |

Performance and Dosage Data

The following table summarizes quantitative findings on how SiO₂ seed concentration and size impact MDCr performance.

Table 2: SiO₂ Seeding Performance and Optimization Data

| Parameter | Performance Outcome | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Dosage | 0.1 g L⁻¹ enhanced steady-state flux by 41% and maintained salt rejection ≥ 99.99% [11]. | Feed: 300 g L⁻¹ NaCl; SiO₂ size: 30-60 µm. |

| High Dosage Effect | At 0.6 g L⁻¹, flux decreased due to near-wall solids holdup and hindered transport [11]. | Demonstrates an upper limit for effective seeding. |

| Seed Size & Crystals | Seeding shifted crystal size distribution from fine (mean 50.6 µm, unseeded) to coarse (230–340 µm) [11]. | Preferential growth on seed surfaces reduces primary nucleation. |

| Membrane Comparison | PTFE membrane exhibited a 47% higher flux than PP under identical seeded conditions [11]. | Due to PTFE's reduced thermal resistance and different module geometry. |

| Wetting Control | Seeding with 0.5 g L⁻¹ of Gypsum (a different seed material) effectively restricted membrane wetting [31]. | Highlights the general principle that induced crystallization suppresses wetting. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Baseline AGMDCr Setup and Operation

This protocol outlines the core experimental setup for evaluating seeds in an Air Gap Membrane Distillation Crystallization (AGMDCr) system.

- System Setup: Configure a mini-pilot-scale AGMDCr system. The core components include a tubular membrane module, a counter-current heat exchanger for feed preheating, a condensation channel with a cooled surface, and a permeate collection vessel placed on a balance for continuous flux measurement [11].

- Instrumentation: Install resistance thermometers at the inlet and outlet of the membrane module and heat exchangers. Use inline conductivity meters to monitor the feed concentrate and the permeate quality continuously [11].

- Feed Preparation: Prepare the hypersaline feed solution. A standard solution is 300 g L⁻¹ of Sodium Chloride (NaCl) in deionized water [11].

- Operating Parameters:

- Set the feed inlet temperature to a defined range (e.g., 53 ± 0.5 °C).

- Maintain the cold side temperature (e.g., 20 ± 1.5 °C).

- Circulate the feed at a constant flow rate (e.g., 95 ± 5 L h⁻¹) to ensure a specific linear velocity over the membrane surface [11].

- Operate the system in batch mode with continuous recirculation for a fixed duration (e.g., 6 hours).

Protocol 2: Evaluating SiO₂ Seed Parameters

This protocol details the specific steps for introducing and testing SiO₂ seeds, building upon the baseline setup.

- Seed Preparation: Procure quartz sand (SiO₂) of high purity (>99%). Sieve the material to obtain the desired size fractions for testing (e.g., 30–60 µm, 75–125 µm, 210–300 µm) [11].

- Seed Introduction: Disperse the pre-weighed seed particles directly into the feed vessel before system startup. The recirculating flow will maintain the seeds in suspension throughout the experiment [11].

- Experimental Series:

- Data Collection:

- Permeate Flux: Record the mass of permeate collected at regular intervals (e.g., every minute) to calculate the flux over time.

- Salt Rejection: Use the inline conductivity meters to ensure salt rejection remains high (e.g., ≥ 99.99%), indicating no membrane wetting [11].

- Crystal Analysis: At the end of the experiment, analyze the crystal size distribution (CSD) of the solids formed in the bulk solution to confirm the shift from fine to coarse crystals due to seeding [11].

Experimental Workflow for SiO₂ Seeding Optimization

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: After introducing SiO₂ seeds, my permeate flux initially improved but then decreased more rapidly than expected. What could be the cause? This is a classic sign of excessive seed concentration. While low doses (e.g., 0.1-0.3 g L⁻¹) enhance flux by reducing scaling, high doses (e.g., 0.6 g L⁻¹) can cause near-wall solids holdup. The high concentration of particles physically hinders fluid transport and increases viscosity near the membrane surface, exacerbating concentration polarization and flux decline [11]. We recommend performing a dosage series to identify the optimal concentration for your specific system.

Q2: I am achieving good flux, but my permeate conductivity is rising, indicating salt leakage. Is this related to seeding? Rising permeate conductivity is a sign of membrane wetting. While proper seeding is designed to suppress wetting by preventing scale growth that can penetrate pores, this issue may persist. First, verify that your seed dosage is sufficient (e.g., 0.5 g L⁻¹ was effective for gypsum scaling) to fully control crystallization [31]. Second, ensure you are using a membrane material with high wetting resistance, such as PTFE, which has shown superior performance in seeded systems [11]. Third, investigate integrating seeding with other techniques like Microbubble Aeration (MBA), which has shown a synergistic effect in controlling wetting by creating bubbly flow that detaches crystals from the membrane surface [31].

Q3: The crystals forming in my system are very fine and difficult to separate, even with seeding. How can I promote larger crystal growth? The size of the seed particles directly influences the final crystal size. Using larger SiO₂ seeds (e.g., 210-300 µm) can result in the growth of larger, more easily separable crystals (e.g., 230-340 µm) [11]. This occurs because the seeds provide a larger surface area for growth, favoring heterogeneous crystallization over the spontaneous formation of fine crystals in the bulk solution (homogeneous nucleation). Optimizing the seed size distribution is crucial for controlling the final product's crystal size.

Q4: My membrane is still scaling significantly despite using seeds. What other factors should I check? Check your system's hydrodynamics. Inadequate flow velocity or the absence of a turbulence-promoting spacer can limit the effectiveness of seeds. The seeds need to be kept in suspension and brought close to the membrane surface to compete effectively with it for nucleation. Furthermore, consider the membrane material itself. PTFE membranes have demonstrated a 47% higher flux than Polypropylene (PP) under identical seeded conditions, due to their lower thermal resistance and different surface properties [11]. The choice of membrane is a critical factor that works in tandem with the seeding strategy.

Membrane distillation crystallization (MDC) is an emerging hybrid technology for treating hypersaline wastewater, offering simultaneous recovery of fresh water and valuable mineral resources. However, its industrial application is severely limited by membrane scaling, where inorganic salts crystallize and deposit on membrane surfaces, leading to pore blockage, flux decline, and eventual membrane failure [3]. Conventional solutions, including chemical antiscalants, introduce economic and environmental burdens, necessitating more sustainable approaches [35] [21].

Our previous research demonstrated that 3D-printed Carbon Nanotube (CNT) spacers significantly improve membrane performance. This technical guide elucidates the mechanism—CNT spacer-induced cooling crystallization—and provides troubleshooting support for researchers implementing this technology within their MDC experiments.

Mechanism: How CNT Spacers Mitigate Scaling

The CNT spacer introduces a novel, non-chemical method for scaling control by fundamentally altering crystallization kinetics and crystal adhesion properties.

- Inducing Bulk Crystallization: The nanoscale roughness and nanochannels of the exposed CNT surface appear to strengthen hydrogen bonding within the solution, which delays the onset of nucleation. When crystallization occurs, it is promoted in the bulk solution rather than on the membrane surface [35].

- Modifying Crystal Habit: The presence of the CNT spacer results in the formation of larger crystals that possess lower specific surface energy, making them less likely to adhere to surfaces [35].

- Reducing Crystal Adhesion: The rough surface of the CNT spacer facilitates easier detachment of initial nuclei compared to smooth surfaces. These detached nuclei then grow into larger crystals in the bulk solution, reducing the dissolved solute available for surface scaling [21].

- Enhancing Hydrodynamics: The unique multiscale roughness of the CNT spacer promotes turbulence and enhances vaporization, potentially leading to bubbly flow along the membrane channel. This helps sweep away formed crystals and reduces surface scaling [21].

The following diagram illustrates the comparative scaling mechanism with a conventional spacer versus the CNT spacer.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Core Experimental Setup for Evaluating CNT Spacers

Adopt this foundational methodology to assess CNT spacer performance in DCMD configurations.

Apparatus and Materials

- Membrane Module: A flat-sheet or hollow fiber DCMD module equipped with spacer channels [21] [36].

- Membrane: Hydrophobic microporous membrane (e.g., PVDF, PTFE) [35] [36].

- Spacers: 3D-printed CNT spacer (experimental) and commercial PLA spacer (control) [35] [21].

- Feed Solution: Prepare a supersaturable salt solution (e.g., 0.01 M CaSO₄ for general scaling studies, or 1 M Na₂SO₄ for cooling crystallization studies) [35] [21].

- Instrumentation: Permeate flux measurement system, temperature controllers, conductivity meter, and analytical tools (e.g., SEM, OCT, UV-Vis spectrophotometer) [35] [21].

Standard Operational Procedure

- System Preparation: Install the membrane and spacer securely in the module. Circulate deionized water to check for leaks and establish a baseline flux.

- Experiment Initiation: Switch the feed to the salt solution. Set the feed inlet temperature (e.g., 60°C, 70°C, or 80°C) and the permeate inlet temperature (e.g., 20°C) to establish the thermal driving force [21].

- Continuous Operation & Monitoring: Run the system in batch or concentration mode. Continuously monitor and record the permeate flux and feed conductivity. Calculate the Volume Concentration Factor (VCF) over time [21].

- Termination and Analysis: Once a target VCF is reached or flux declines significantly, terminate the experiment. Disassemble the module to collect the membrane and spacer for post-mortem analysis via SEM and microscopy to characterize crystal morphology and deposition [35].

Workflow for a Cooling Crystallization Study

This specific workflow, adapted from the foundational research, is designed to probe the induced cooling crystallization mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential Materials for CNT Spacer MDC Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Key Characteristics & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 3D-Printed CNT Spacer | Experimental spacer that induces cooling crystallization. | Multiscale surface roughness; nanoscale channels strengthen H-bonding in solution, delaying nucleation and promoting larger, less adherent crystals [35] [21]. |

| PLA Spacer | Control spacer for comparative studies. | Standard 3D-printed polymer spacer without CNTs; provides a baseline for performance evaluation [35] [21]. |

| PVDF Membrane | Hydrophobic microporous membrane. | Standard polymer for MD; allows vapor transport while rejecting liquid and non-volatile solutes [35] [36]. |

| Sodium Sulfate (Na₂SO₄) | Model scalant for cooling crystallization studies. | Exhibits strong temperature-dependent solubility (40 g at 303 K vs. 9 g at 283 K), ideal for probing cooling crystallization mechanisms [35]. |

| Calcium Sulfate (CaSO₄) | Model scalant for general scaling studies. | A common scalant in water due to high content and low solubility; represents a key challenge in industrial MD applications [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Flux Decline | 1. Excessive supersaturation.2. Incorrect temperature gradient.3. Spacer not properly installed. | Optimize feed concentration and VCF target. Moderate the feed temperature to balance flux and scaling rate [21]. Ensure spacer fits snugly to promote proper flow dynamics. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | 1. Variations in spacer fabrication.2. Fluctuations in feed temperature.3. Membrane properties vary. | Source spacers from a consistent, qualified production batch. Use high-precision thermostatic baths for temperature control. Characterize membrane properties (LEP, porosity) before use. |

| Crystal Deposition on Membrane Despite CNT Spacer | 1. Feed concentration too high.2. Crystallization occurring in "dead zones."3. Experiment duration too long. | This is expected at very high VCF; note that CNT spacers delay, not completely prevent, scaling [35]. Confirm spacer design promotes uniform flow and minimizes dead zones [35]. |

| No Significant Difference Between CNT and PLA Spacers | 1. Using a salt with low temperature-dependent solubility.2. Insufficient monitoring period.3. Flow rate too low. | Use Na₂SO₄ to clearly observe the cooling crystallization effect [35]. Run experiments to a higher VCF; performance divergence often increases with time [21]. Increase cross-flow velocity to enhance spacer-induced turbulence. |

Quantitative Performance Data

The efficacy of the CNT spacer is quantitatively demonstrated through key performance metrics compared to control configurations.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CNT Spacers in MD

| Experimental Condition | Key Performance Metric | Result with CNT Spacer | Result with PLA/No Spacer | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCMD with 0.01 M CaSO₄ (Feed: 60°C) [21] | Flux at VCF > 4.0 | > 29 Lm⁻²h⁻¹ (37% reduction from initial flux) | ~0 Lm⁻²h⁻¹ (Complete flux loss before VCF 3.5) | CNT spacer maintains functionality at high concentration factors where control fails. |

| DCMD with 0.01 M CaSO₄ [21] | Initial Permeate Flux | 46 LMH | 42 LMH (PLA Spacer) | The multiscale roughness of CNT enhances flux from the start. |

| Cooling Crystallization with 1 M Na₂SO₄ [35] | Crystal Size & Adhesion | Larger crystals with reduced adhesion | Smaller crystals forming adherent cake layers | CNT spacer modifies crystal habit, mitigating surface blockage. |

| Long-term Scaling Progression [35] | Membrane Surface Coverage after 12h | Largely free of crystal deposition | Entirely covered by a scale layer | Direct observation confirms scaling mitigation. |