Steady-State vs. Pre-Steady-State Kinetics: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Enzyme Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Steady-State vs. Pre-Steady-State Kinetics: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Enzyme Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing their distinct methodological applications from classic Michaelis-Menten analysis to rapid-quench techniques. The scope extends to troubleshooting common experimental challenges, optimizing assay conditions, and validating mechanisms through integrative case studies. By synthesizing insights from recent research, this guide aims to empower scientists in selecting the appropriate kinetic framework to elucidate enzymatic mechanisms, accelerate drug discovery, and understand therapeutic efficacy.

Core Principles: Defining Steady-State and Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

What is Steady-State Kinetics? The Michaelis-Menten Foundation

Enzyme kinetics is the study of the rates of enzyme-catalyzed reactions, crucial for understanding catalytic mechanisms, metabolic roles, and how drug molecules can alter reaction rates [1]. Within this field, the concept of steady-state kinetics, institutionalized by the Michaelis-Menten equation, forms the foundational framework for interpreting how enzymes interact with their substrates [2]. This model serves as the bedrock upon which much of modern enzymology is built, providing essential parameters to compare enzyme performance and efficiency.

However, a comprehensive understanding of enzyme action requires looking beyond this steady-state. A broader thesis is emerging that compares the established methods of steady-state analysis with the more detailed insights provided by pre-steady-state kinetic analysis. While steady-state kinetics offers a simplified and accessible view of the overall reaction, pre-steady-state kinetics delves into the transient phases at the reaction's start, revealing the individual steps and short-lived intermediates that are masked once a steady state is achieved [3] [4]. This guide will objectively compare these two approaches, outlining their principles, methodologies, applications, and how they complement each other in biochemical research and drug development.

The Michaelis-Menten Model: Principles and Assumptions

The modern definition of enzymology is synonymous with the Michaelis-Menten equation, introduced by Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten in 1913 and later modified by Briggs and Haldane using the steady-state assumption [2]. This model describes the fundamental catalysis of enzymatic reactions through a series of steps. The enzyme (E) binds the substrate (S) to form an enzyme-substrate complex (ES), which then reacts to form the product (P) and release the free enzyme [5].

The entire reaction can be represented as: E + S ⇄ ES → E + P

The Michaelis-Menten equation is: V₀ = (Vₘₐₓ × [S]) / (Kₘ + [S])

Where:

- V₀ is the initial reaction velocity.

- Vₘₐₓ is the maximum reaction velocity, achieved when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate.

- [S] is the substrate concentration.

- Kₘ is the Michaelis constant, defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vₘₐₓ [5].

The derivation of this equation relies on several key assumptions [5]:

- Initial Velocity: The equation describes only the initial reaction velocity (V₀), when the substrate concentration is much greater than the product concentration.

- Steady-State Approximation: The concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex [ES] remains constant over time because the rate of its formation equals the rate of its consumption.

- Free Ligand Approximation: The total substrate concentration is approximately equal to the free substrate concentration, as the enzyme concentration is much lower than the substrate concentration ([S]>>>[E]).

- Single-Substrate Reaction: The model initially applies to reactions with a single substrate. The reverse reaction (product to substrate) is also considered negligible.

The relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity is graphically represented by a hyperbolic saturation curve [5]. As substrate concentration increases, the reaction velocity increases until it plateaus at Vₘₐₓ, indicating that all available enzyme molecules are saturated and operating at their maximum capacity.

Steady-State vs. Pre-Steady-State Kinetics: A Direct Comparison

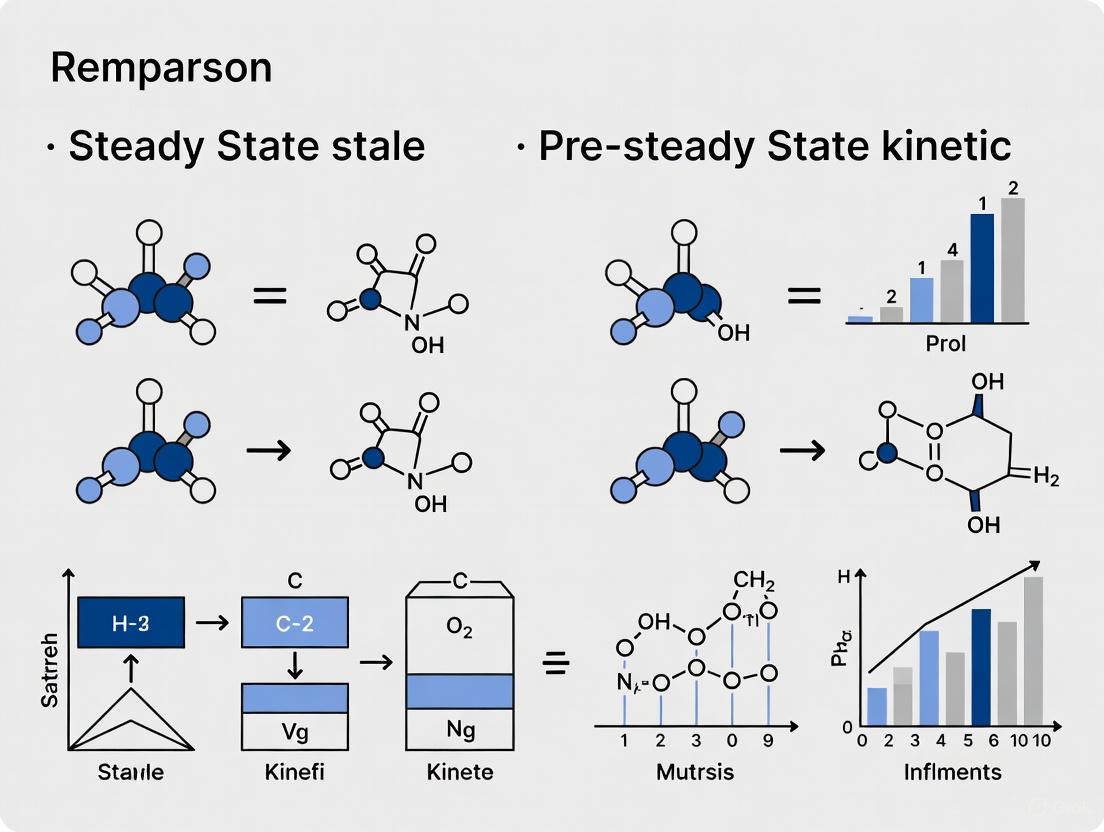

The following table provides a structured, point-by-point comparison of these two fundamental approaches to kinetic analysis.

Comparison of Steady-State and Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

| Feature | Steady-State Kinetics | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Time Frame Analyzed | The period after initiation when [ES] is constant, typically seconds to minutes [1]. | The initial transient phase before steady-state is established, typically milliseconds to seconds [3] [4]. |

| Primary Kinetic Parameters Obtained | ( Km ) (Michaelis constant), ( V{max} ) (maximum velocity), and ( k_{cat} ) (turnover number) [3]. | Individual rate constants for binding, catalysis, and product release (e.g., ( k1 ), ( k2 ), ( k_3 )) [6] [3]. |

| Information Provided | Overall catalytic efficiency (( k{cat}/Km )) and substrate specificity. Provides a "black box" view of the overall reaction [3]. | Reveals the actual reaction mechanism, including short-lived intermediates and the rate-limiting step [3] [4]. |

| Typical Experiment Duration | Longer time scales (minutes). | Very short time scales (milliseconds to seconds) [3]. |

| Enzyme Concentration Required | Low, as the enzyme acts catalytically. | High, as the enzyme is treated as a stoichiometric reactant to observe its behavior directly [3]. |

| Key Assumptions | Steady-state of [ES], initial velocity conditions [5]. | No equilibrium or steady-state assumptions; observes the system as it evolves. |

| Example Experimental Data | FOR enzyme: ( Km ) (formaldehyde) = 21 µM; ( Km ) (ferredoxin) = 14 µM [6]. | FOR enzyme: Fast processes (( k{obs1} = 4.7 \, s^{-1} ), ( k{obs2} = 1.9 \, s^{-1} )) interpreted as substrate oxidation and active site rearrangement [6]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The choice between steady-state and pre-steady-state analysis dictates the experimental setup, instrumentation, and protocols required.

Steady-State Kinetics Protocol

Steady-state assays are typically performed by incubating an enzyme with varying concentrations of its substrate and monitoring the formation of product or disappearance of substrate over time.

A classic example is the study of Formaldehyde Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase (FOR) from Pyrococcus furiosus [6]:

- Objective: Determine steady-state parameters for FOR with formaldehyde as a substrate.

- Method: Activity was assayed at 80°C under anaerobic conditions.

- Substrate: Formaldehyde.

- Electron Acceptors: Benzyl viologen or ferredoxin at various concentrations.

- Measurement: The rate of electron acceptor reduction was monitored optically (using the extinction coefficients of the acceptors) in triplicate.

- Analysis: The ( K_m ) values for formaldehyde and the electron acceptors were determined from the activity measurements, fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten model [6].

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics Protocol

Pre-steady-state experiments require specialized equipment to initiate a reaction and observe it on a millisecond timescale. Two common techniques are stopped-flow and chemical quench-flow.

Stopped-Flow Spectroscopy: Two reactant solutions are rapidly mixed and pushed into an observation cell. The flow is abruptly stopped, and an optical signal (e.g., absorbance or fluorescence) is monitored as a function of time as the reaction proceeds in the cell [3]. This was used in the FOR study to monitor the weak optical spectrum of the tungsten cofactor, revealing several fast processes in the first seconds of the reaction [6].

Chemical Quench-Flow: The reaction is initiated by rapid mixing of enzyme and substrate. After a precise, user-defined delay (milliseconds to seconds), the reaction mixture is combined with a quenching agent (e.g., acid or base) that denatures the enzyme and stops the reaction instantly. The quenched mixture is then analyzed offline, often using chromatography or mass spectrometry, to quantify reactants, intermediates, and products at that specific time point [7] [3].

The workflow for a pre-steady-state experiment, such as nucleotide incorporation by a DNA polymerase, can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Instruments

Successful kinetic analysis, particularly pre-steady-state, relies on specific reagents and sophisticated instrumentation.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Purified Enzyme: The enzyme of interest, often recombinant and highly purified (e.g., human DNA polymerase η or SARS-CoV-2 Mpro) [7] [4].

- Substrate: Natural or synthetic substrate, sometimes chromophoric or fluorescently labeled for detection (e.g., FAM-labeled DNA primer) [7].

- Cofactors: Essential ions or molecules, such as Mg²⁺ for DNA polymerases [7].

- Quenching Agent: A solution to stop reactions instantly (e.g., 500 mM EDTA to chelate essential metal ions, or strong acid/base) [7].

- Reaction Buffers: To maintain optimal pH and ionic strength (e.g., Tris-HCl, Epps) [6] [7].

Essential Instruments

- Spectrophotometer/Fluorometer: Standard for monitoring steady-state reactions by absorbance or fluorescence [6].

- Rapid Quench-Flow Instrument (e.g., RQF-3): A specialized apparatus that mixes, ages, and quashes reactions with millisecond precision [7].

- Stopped-Flow Spectrometer: Instrument for rapid mixing and subsequent continuous optical monitoring of reactions [3].

- Analytical Equipment: High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or gel electrophoresis systems for analyzing quenched samples [7] [3].

Application in Action: Case Study on SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease

The power of pre-steady-state kinetics is exemplified in modern drug discovery, particularly in the development of antivirals against SARS-CoV-2.

The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) is an essential viral enzyme, processing viral polyproteins and is a primary target for antiviral drugs [4]. Researchers used pre-steady-state kinetic analysis to investigate the mechanism of inhibition of Mpro by promising drug candidates like PF-00835231.

This approach allowed them to move beyond simple IC₅₀ values and uncover the detailed mechanism of action. The analysis revealed that PF-00835231 inhibition occurs via a two-step binding process, followed by the formation of a covalent complex with the catalytic cysteine of the enzyme [4]. Furthermore, by also studying a catalytically inactive mutant (C145A), they demonstrated that strong, non-covalent binding due to an excellent fit in the active site contributes significantly to the inhibitor's potency [4].

This deep mechanistic insight, provided by pre-steady-state kinetics, is invaluable for optimizing lead compounds and designing more effective drugs, showcasing a critical application that goes far beyond the capabilities of steady-state analysis alone.

This guide provides an objective comparison between steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis, two fundamental methodologies for studying enzyme mechanisms. While steady-state kinetics, underpinned by the assumption of a constant enzyme-substrate (ES) complex concentration, offers simplified parameters for routine characterization, pre-steady-state kinetics unveils the rapid, transient events of a single catalytic cycle. The selection between these methods is not a matter of superiority but of objective, as each provides distinct insights critical for different stages of research, from initial enzyme characterization to detailed mechanistic understanding and drug discovery.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

The steady-state assumption is a cornerstone of classical enzyme kinetics, positing that the concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) remains constant over time during the reaction. This occurs because the rate of ES formation is equal to the rate of its consumption (both dissociation back to E+S and formation of E+P) [5]. This assumption holds true provided the substrate concentration [S] is significantly greater than the enzyme concentration [E], ensuring that the free substrate concentration does not change appreciably [8] [5].

The following table contrasts the key features of steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analyses.

| Feature | Steady-State Kinetics | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Timeframe | Seconds to minutes; after ES complex stabilizes [9]. | Milliseconds to seconds; immediately after reaction initiation [9]. |

| Primary Measured Parameters | ( KM ) (Michaelis constant), ( V{max} ) (maximum velocity), ( k_{cat} ) (turnover number) [5]. | Individual rate constants (e.g., ( k1 ), ( k{-1} ), ( k_2 )), observation of transient intermediates [10] [9]. |

| Information Provided | Catalytic efficiency (( k{cat}/KM )), enzyme affinity for substrate (inversely related to ( K_M )) [5]. | Direct observation of binding, conformational changes, and chemical catalysis steps; identifies rate-limiting steps [11] [10]. |

| [ES] Complex Concentration | Assumed to be constant (steady-state assumption) [8] [5]. | Directly observed as it forms and decays; not constant [9]. |

| Data Interpretation | ( KM ) and ( k{cat} ) are composite constants, combinations of individual rate constants [9]. | Resolves individual rate constants for each step in the catalytic cycle [10]. |

| Typical Applications | Routine enzyme characterization, inhibitor screening, determining catalytic efficiency [5]. | Elucidating detailed reaction mechanisms, studying fast conformational changes, drug residence time [11] [12]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Steady-State Kinetics: The Michaelis-Menten Protocol

Objective: To determine the Michaelis constant (( KM )) and the maximum velocity (( V{max} )).

Methodology:

- A fixed, low concentration of enzyme is prepared.

- The initial velocity (( V_0 )) of the reaction is measured across a range of substrate concentrations ([S]).

- [S] must be in vast excess over [E] to satisfy the steady-state assumption [5].

- ( V_0 ) is plotted against [S], typically producing a hyperbolic saturation curve.

- The data are fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to extract ( KM ) and ( V{max} ): ( V0 = \frac{(V{max} [S])}{(K_M + [S])} ) [5].

Key Assumptions:

- The enzyme-substrate complex [ES] is in a steady state.

- The reaction is measured at initial velocity conditions, where product concentration is negligible and reverse reactions are minimal [5].

- The first step (E + S ⇌ ES) is often assumed to be faster than the catalytic step (ES → E + P) [8].

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics: Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Protocol

Objective: To observe the formation and decay of transient intermediates and measure individual rate constants.

Methodology:

- High Enzyme Concentration: Enzyme concentrations are typically much higher than in steady-state experiments to allow for stoichiometric detection of intermediates [9].

- Rapid Mixing: Enzyme and substrate solutions are rapidly mixed in a stopped-flow apparatus, initiating the reaction on a millisecond timescale.

- Signal Detection: A rapid detection method, such as fluorescence or absorbance spectroscopy, monitors the reaction in real-time. For instance, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence in the Fpg protein was used to track conformational changes during lesion processing [11].

- Data Analysis: The resulting trace is fitted to exponential equations to extract observed rate constants (( k_{obs} )) for each phase. A study on Fpg protein identified up to five distinct conformational transitions in the pre-steady-state phase [11].

Key Insights from Pre-Steady-State Data:

- Burst Phase Kinetics: Evidence of a phosphoenzyme intermediate was found in a phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase, where a rapid "burst" of product formation was observed, followed by a slower steady-state rate. This burst phase had a rate constant of 48 s⁻¹, while the steady-state turnover was 1.2 s⁻¹ [10].

- Conformational Changes: Research on formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase revealed multiple fast processes (( k{obs1} = 4.7 s^{-1}, k{obs2} = 1.9 s^{-1} )) interpreted as substrate oxidation and active site rearrangement [6].

Experimental Workflow and Data Interpretation

The diagram below illustrates the logical sequence of a kinetic analysis workflow, from initial setup to data interpretation for both steady-state and pre-steady-state methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Techniques

The following table details essential materials and methods used in kinetic studies.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Kinetic Analysis |

|---|---|

| Stopped-Flow Spectrometer | Rapid mixing device for initiating reactions and monitoring changes in absorbance or fluorescence on millisecond timescales [11] [6]. |

| Chemical Quench-Flow Apparatus | Rapidly mixes reactants and, after a precise time interval, mixes again with a quenching agent (e.g., acid) to stop the reaction for offline analysis [9]. |

| Synthetic Oligonucleotide Substrates | Defined DNA substrates containing specific lesions (e.g., 8-oxoguanine); essential for studying DNA repair enzymes like Fpg [11]. |

| Chromophoric Substrate Analogs | Artificial substrates (e.g., p-nitrophenyl phosphate) that produce a color change upon reaction, facilitating optical detection in steady-state studies [10] [9]. |

| Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) | A powerful technique for directly detecting and identifying reactive intermediates and products in an enzymatic reaction, providing direct chemical insight [9]. |

The steady-state assumption provides a powerful simplification that makes enzyme characterization tractable, yielding the foundational parameters ( KM ) and ( V{max} ). However, this simplification necessarily obscures the rich, transient dynamics of the catalytic cycle. Pre-steady-state kinetics strips away this assumption, directly observing the formation of the ES complex and subsequent intermediates to dissect the mechanism at the level of individual rate constants. For researchers, the choice is contextual: steady-state for initial characterization and efficiency metrics, pre-steady-state for mechanistic elucidation and detailed drug interaction studies. A comprehensive kinetic strategy often leverages both to build a complete picture of enzyme function.

Enzyme kinetics, the study of reaction rates catalyzed by enzymes, provides fundamental insights into catalytic mechanisms, metabolic roles, cellular control, and inhibition by drugs or toxins [13]. Within this field, two complementary experimental approaches have emerged: steady-state kinetics and pre-steady-state kinetics. While steady-state kinetics has been the traditional workhorse for characterizing enzyme activity, pre-steady-state kinetics offers a window into the early, transient phases of enzymatic reactions that are critical for understanding mechanistic details [14] [15]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, highlighting their respective capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications in modern biochemical research and drug development.

The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in their observational timeframes. Steady-state kinetics observes enzyme behavior after reaction intermediates have reached constant concentrations, typically measuring substrate depletion or product formation over seconds to minutes [14] [13]. In contrast, pre-steady-state kinetics captures events during the initial burst phase before intermediates stabilize, requiring time resolution from milliseconds to seconds [14] [15]. This temporal distinction enables each method to illuminate different aspects of enzyme function, making them valuable for different research objectives.

Theoretical Foundations

Steady-State Kinetics Principles

Steady-state kinetics describes enzymatic behavior once the concentrations of reaction intermediates (such as enzyme-substrate complexes) have reached a constant level [14]. This occurs when the rates of formation and decay of these intermediates are equal, resulting in a period where the reaction rate remains relatively constant until substrate depletion becomes significant [14] [13]. The Michaelis-Menten equation, derived from steady-state assumptions, relates reaction velocity (v) to substrate concentration ([S]) through two key parameters: Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant) [13] [16]:

[v = \frac{V{\text{max}}[S]}{Km + [S]}]

Where (V{\text{max}}) represents the maximum rate achieved at saturating substrate concentrations, and (Km) is the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of (V{\text{max}}) [14] [13]. Traditionally, (Km) has been interpreted as an inverse measure of substrate affinity, though this interpretation is only valid under specific mechanistic conditions [16].

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics Principles

Pre-steady-state kinetics describes the behavior of an enzymatic reaction during the initial phase, before the concentrations of reaction intermediates have reached a steady state [14]. In this regime, intermediate concentrations change rapidly over time as they are formed and consumed during the early reaction stages [14]. The approach typically involves changing conditions (e.g., rapidly mixing reactants) and observing how the system evolves over time as it approaches a new equilibrium [15].

The time course of this "relaxation" to equilibrium generally follows a single exponential or sum of exponentials, described by equations of the form [15]:

[\text{Signal}(t) = A(1 - e^{-k_{\text{obs}}t}) + C]

Where the signal (e.g., fluorescence, absorbance) tracks concentration changes, (k_{\text{obs}}) is the observed rate constant, and A and C are constants. These measurements provide direct access to individual rate constants for elementary steps in the reaction mechanism, offering insights not available from steady-state analysis alone [14] [15].

Methodological Comparison

Experimental Techniques and Time Resolution

The fundamental difference between steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics lies in their temporal resolution and the corresponding experimental approaches required to capture reactions at these timescales.

Table 1: Experimental Approaches for Kinetic Analysis

| Methodological Aspect | Steady-State Kinetics | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Time Resolution | Seconds to minutes | Milliseconds to seconds |

| Typical Assay Format | Continuous monitoring or discrete sampling | Rapid mixing with continuous monitoring |

| Key Techniques | Traditional spectrophotometry, fluorimetry, radiometric assays | Stopped-flow, rapid quench-flow, temperature-jump |

| Data Collection | Linear initial rate period measured over minutes | Transient phase captured in first few seconds |

| Instrumentation Requirements | Standard laboratory equipment (spectrophotometers) | Specialized rapid-mixing equipment |

Information Content and Kinetic Parameters

Each kinetic approach provides distinct insights into enzyme function, with differing abilities to resolve individual steps in the catalytic cycle.

Table 2: Information Content of Kinetic Approaches

| Parameter/Insight | Steady-State Kinetics | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Parameters | kcat, Km, kcat/Km | Individual rate constants for elementary steps |

| Intermediate Detection | Indirect inference | Direct observation of formation and decay |

| Rate-Determining Step | Identified but not characterized | Direct characterization of individual steps |

| Conformational Changes | Only if rate-limiting | Potentially observable even if not rate-limiting |

| Binding Constants | Apparent (Km) | Direct measurement of association/dissociation rates |

The specificity constant (kcat/Km) provides a measure of enzyme efficiency and is proportional to the apparent second-order rate constant for substrate binding [16]. However, as Johnson (2019) emphasizes, "kcat and kcat/Km should be considered as the two primary steady state kinetic parameters, rather than kcat and Km" because kcat/Km quantifies enzyme specificity, efficiency, and proficiency, while Km alone is often uninterpretable without additional information [16].

Experimental Protocols

Steady-State Kinetics Protocol

Objective: Determine kcat and Km for an enzymatic reaction under substrate saturation conditions.

Procedure:

- Prepare a constant concentration of enzyme (typically 0.0002 mM) [17] in appropriate buffer

- Create a series of substrate concentrations spanning below and above the expected Km (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 5, 10, 100 mM) [17]

- Initiate reactions by adding enzyme to substrate solutions

- Measure initial velocity by tracking product formation or substrate depletion

- Ensure measurements occur during the linear phase of reaction progress [13]

- Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression or linear transformations (Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee) [13] [18]

Data Analysis:

- Plot reaction velocity (v) versus substrate concentration ([S])

- Fit data to: (v = \frac{k{\text{cat}}[E]{\text{tot}}[S]}{K_m + [S]})

- kcat = Vmax/[E]tot

- Alternatively, use the form: (v = \frac{k{SP}[S]}{1 + k{SP}[S]/k_{\text{cat}}}) where kSP = kcat/Km to directly obtain the specificity constant [16]

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics Protocol

Objective: Measure individual rate constants for elementary steps in an enzymatic mechanism by capturing transient phases.

Procedure:

- Stopped-Flow Method [14]:

- Load syringes with enzyme and substrate solutions

- Rapidly mix solutions (mixing time ~1 ms)

- Monitor signal change (absorbance, fluorescence) immediately after mixing

- Collect data points at high temporal resolution (microsecond to millisecond intervals)

- Repeat at multiple substrate concentrations

- Rapid Quench-Flow Method [14]:

- Rapidly mix enzyme and substrate solutions

- Allow reaction to proceed for precisely controlled time intervals

- Quench reaction with acid, base, or denaturant at specific times

- Analyze quenched samples for product formation using separation methods (HPLC, electrophoresis) or spectroscopic techniques

Data Analysis:

- Fit time courses to single or multiple exponential functions

- Determine observed rate constants (kobs) at each substrate concentration

- Analyze dependence of kobs on substrate concentration to extract individual rate constants

- Use kinetic simulation software for complex mechanisms

Comparative Analysis of DNA Polymerase Fidelity

A comprehensive study comparing steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic approaches for measuring DNA polymerase fidelity provides an excellent case study for methodological comparison [19]. This research directly evaluated the fidelity of the proofreading-deficient Klenow fragment (KF(-)) DNA polymerase using both traditional steady-state methods and pre-steady-state kinetics, comparing these results with direct competition measurements.

Table 3: DNA Polymerase Fidelity Measurement Comparison

| Methodological Approach | Measured Fidelity (R:W Ratio) | Key Advantages | Technical Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Competition | Variable across 12 natural base mispairs (9 measurable) | Direct physiological relevance; measures actual partitioning | Detection of minor W products masked by major R products |

| Steady-State Kinetics | Quantitative agreement with direct competition | Broadly accessible methodology; well-established protocols | Measures kcat/Km indirectly under substrate saturation |

| Pre-Steady-State Kinetics | Quantitative agreement with both other methods | Direct measurement of elementary steps; identifies rate-limiting steps | Requires specialized equipment; more complex data analysis |

The study found that "all the data are in quantitative agreement" across the three methods, validating the kinetic approaches for fidelity measurements [19]. This demonstrates that while pre-steady-state kinetics provides more detailed mechanistic information, steady-state methods can yield equivalent functional parameters when appropriately applied.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Successful implementation of kinetic studies requires specific reagents and methodologies tailored to each approach.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function in Kinetic Studies | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Stopped-Flow Spectrometer | Rapid mixing (∼1 ms) with continuous monitoring | Pre-steady-state kinetics of fast reactions |

| Rapid Quench-Flow Instrument | Rapid mixing followed by chemical quenching | Pre-steady-state analysis of reactions requiring product separation |

| Fluorescent Nucleotide Analogs | Reporting on binding and conformational changes | Pre-steady-state studies of nucleotide-dependent enzymes |

| Isotopically Labeled Substrates | Tracing chemical fate; kinetic isotope effects | Identifying rate-determining steps in both kinetic approaches |

| Synthetic Substrate Analogs | Monitoring specific bond cleavages | Steady-state activity assays (e.g., USP lactase units) [18] |

| Enzyme-Coupled Assay Systems | Amplifying signal for low-activity enzymes | Both approaches, particularly steady-state |

Advantages and Limitations in Research Applications

Strengths of Each Approach

Steady-State Kinetics Advantages:

- Technical Accessibility: Requires standard laboratory equipment available in most biochemical laboratories [18]

- Established Protocols: Well-characterized methodology with extensive literature support

- Parameter Efficiency: Directly provides kcat/Km, the key parameter for enzyme specificity and efficiency [16]

- Therapeutic Applications: Suitable for enzyme characterization required by regulatory agencies [18]

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics Advantages:

- Mechanistic Resolution: Direct observation of intermediate formation and decay [14]

- Elementary Step Characterization: Measurement of individual rate constants for distinct reaction steps [15]

- Dynamic Information: Captures conformational changes and transient species [14]

- Comprehensive Understanding: Reveals features not apparent from steady-state analysis alone [14]

Practical Limitations

Steady-State Kinetics Limitations:

- Averaged Parameters: Provides population averages that may mask individual steps

- Indirect Information: Intermediate steps must be inferred rather than directly observed

- Limited Temporal Resolution: Misses early transient phases rich in mechanistic information

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics Limitations:

- Specialized Equipment: Requires expensive instrumentation not universally available [15]

- Technical Expertise: Demands significant experience in experimental design and data interpretation

- Sample Consumption: Often requires substantial amounts of purified enzyme

- Time-Intensive Analysis: Complex data fitting and modeling requirements

Conceptual and Experimental Workflows

The relationship between steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics, along with their experimental implementations, can be visualized through the following conceptual and technical workflows:

Diagram Title: Kinetic Approaches Relationship

Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics offer complementary rather than competing perspectives on enzyme function. Steady-state kinetics provides efficient characterization of overall enzyme efficiency through kcat/Km and is more accessible for routine characterization [16] [18]. Pre-steady-state kinetics delivers unparalleled mechanistic resolution of individual steps but requires specialized resources and expertise [14] [15].

The choice between these approaches depends entirely on research objectives: steady-state kinetics for functional characterization and screening applications, pre-steady-state kinetics for detailed mechanistic studies. As demonstrated in the DNA polymerase fidelity study [19], these methods can yield quantitatively equivalent parameters for functional comparisons while providing different levels of mechanistic insight. For comprehensive enzyme characterization, the most powerful strategy often combines both approaches, using steady-state analysis for initial functional assessment followed by pre-steady-state investigations to elucidate underlying mechanisms.

Pre-steady-state and steady-state kinetic analyses represent complementary approaches for elucidating the intricate mechanisms of enzyme catalysis and biological processes. While steady-state kinetics provides a macroscopic view of overall enzyme efficiency through parameters like kcat and KM, pre-steady-state kinetics captures the transient molecular events that occur before the system reaches equilibrium—the infamous "burst" phase that often reveals rate-limiting steps [10] [20]. This distinction is not merely technical but fundamental to understanding how enzymes truly operate at the molecular level.

The analysis of burst kinetics has become increasingly relevant across multiple fields, from enzymology to gene regulation. Recent research has demonstrated that these transient kinetic phases often conceal crucial mechanistic information about rate-limiting steps, conformational changes, and allosteric regulation [21] [20]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this distinction provides critical insights for designing better inhibitors, engineering improved enzymes, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies. This guide objectively compares these complementary analytical approaches, their instrumentation requirements, and their respective capabilities for revealing the inner workings of biological systems.

Theoretical Foundation: Burst Phase and Steady-State Kinetics

Defining the Kinetic Regimes

The journey of enzyme-catalyzed reactions begins with a pre-steady-state phase (burst phase) where reaction intermediates accumulate, followed by a steady-state phase where intermediate concentrations remain relatively constant [10]. The burst phase represents the initial transient period when enzyme-substrate complexes form and the first turnover occurs, typically lasting milliseconds to seconds. The steady-state phase follows, characterized by a constant rate of product formation until substrate depletion becomes significant.

Mathematically, the burst phase often follows an exponential approach to the steady-state rate, described by the equation: [P = vss \cdot t + (vi - vss)(1 - e^{-kobs \cdot t})/k_obs] where P is product concentration, vi is initial velocity, vss is steady-state velocity, and kobs is the observed first-order rate constant for the transition [20].

The Significance of Burst Kinetics

The presence of a burst phase provides critical mechanistic information. A pronounced burst indicates that the catalytic step is faster than at least one subsequent step in the pathway, causing accumulation of a reaction intermediate [10]. For instance, in the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate catalyzed by bovine heart phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase, a stoichiometric burst of p-nitrophenol formation revealed a phosphoenzyme intermediate with rapid formation followed by rate-limiting hydrolysis (k2 = 540 s-1, k3 = 36.5 s-1) [10].

Comparative Analysis: Methodologies and Applications

Experimental Designs and Workflows

Figure 1: Experimental workflows for pre-steady-state and steady-state kinetic analyses.

Technical Specifications and Data Output

Table 1: Comparative specifications of pre-steady-state versus steady-state kinetic approaches

| Parameter | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics | Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Time Resolution | Microseconds to seconds | Seconds to hours |

| Key Measured Parameters | Burst amplitude (λ), individual rate constants (k1, k2, k3), transient intermediates | kcat, KM, kcat/KM |

| Instrumentation Requirements | Stopped-flow, quenched-flow, rapid-mixing devices with fast detection | Spectrophotometers, plate readers with temperature control |

| Information Obtained | Direct observation of reaction intermediates, elemental steps, conformational changes | Overall catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, inhibitor potency |

| Sample Consumption | Typically higher (μmol range) | Typically lower (nmol-pmol range) |

| Throughput | Lower (single reactions monitored) | Higher (multiple conditions parallel) |

| Key Applications | Elucidating catalytic mechanisms, identifying rate-limiting steps, characterizing transient intermediates | Screening enzyme variants, determining inhibitor constants, comparative enzymology |

Case Studies: Revealing Mechanistic Insights

β-Lactamase Evolution and Epistasis

Directed evolution of the β-lactamase OXA-48 revealed striking epistatic interactions that dramatically enhanced ceftazidime resistance [21]. While wild-type enzyme showed minimal burst kinetics (1.5-fold higher burst rate than steady-state), evolved variants exhibited pronounced burst phases—F72L showed a 4.6-fold burst and the quadruple mutant Q4 displayed a dramatic 48-fold burst amplitude [21]. Pre-steady-state analysis revealed that epistasis emerged from mutations that sequentially changed the rate-limiting step, with early mutations accelerating substrate binding and later mutations enhancing chemical steps, culminating in 470-800 fold improvement in burst-phase kcat/KM that strongly correlated with in vivo resistance (R2 = 0.97) [21].

Butyrylcholinesterase-Catalyzed Hydrolysis

The hydrolysis of mirabegron by butyrylcholinesterase exhibits classic hysteretic behavior with an extensive pre-steady-state burst phase lasting up to 18 minutes at maximum velocity [20]. This burst results from a slow equilibrium between two active enzyme forms (E and E'), with the initial E form displaying higher activity (kcat = 7.3 min-1, Km = 23.5 μM) than the final E' form (kcat = 1.6 min-1, Km = 3.9 μM) [20]. This mechanistic insight, obtainable only through pre-steady-state analysis, explains the complex catalytic behavior and predicts minimal impact on pharmacological activity despite slow degradation in blood.

Transcriptional Bursting in Gene Regulation

In gene regulation, transcriptional bursting represents a biological analog to enzymatic burst kinetics, with stochastic switching between active (ON) and inactive (OFF) states [22]. Recent live-cell imaging reveals that burst frequency—rather than duration or amplitude—serves as the primary regulatory parameter, with transcription factor binding dynamics (occurring on timescales of seconds) somehow generating transcriptional bursts lasting minutes to hours [22]. This temporal mismatch suggests complex multi-step mechanisms where short-lived molecular events initiate prolonged output states, analogous to hysteretic enzyme behavior.

Table 2: Kinetic parameters from case studies demonstrating burst-phase phenomena

| Biological System | Observed Burst Amplitude | Burst Duration | Molecular Interpretation | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactamase OXA-48 (Evolved Q4) | 48-fold higher than steady-state | Not specified | Change in rate-limiting step from substrate binding to chemical step | 40-fold increase in antibiotic resistance [21] |

| Butyrylcholinesterase with Mirabegron | vi > vss | τ ≈ 18 min at Vmax | Hysteresis between enzyme forms E and E' | Minimal pharmacological impact despite slow degradation [20] |

| Phosphotyrosyl Protein Phosphatase | Stoichiometric burst | Transient phase (k = 48 s-1) | Rate-limiting breakdown of phosphoenzyme intermediate (k3 = 1.2 s-1) | Identification of catalytic pathway with intermediate [10] |

| Transcriptional Activation | ON/OFF switching | Minutes to hours | Stochastic TF binding (seconds) vs. prolonged output | Regulation of burst frequency controls RNA output [22] |

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for kinetic analysis

| Reagent/Instrument | Specifications | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stopped-Flow Spectrometer | Millisecond time resolution, temperature control, multiple detection modes (absorbance, fluorescence) | Pre-steady-state burst phase measurement of rapid enzymatic reactions [21] |

| Rapid Quench-Flow Instrument | Millisecond mixing and quenching capabilities, chemical or freeze-quenching | Trapping enzymatic intermediates for structural analysis or quantification |

| p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate | Chromogenic substrate, λmax = 405 nm upon hydrolysis (pKa = 7.2) | Continuous assay for phosphatases and phosphohydrolases [10] |

| MS2/PP7 RNA Labeling System | Fluorescent RNA stem-loops for live-cell imaging of nascent transcripts | Visualization of transcriptional bursting kinetics in living cells [22] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | High-fidelity polymerases, efficient bacterial transformation | Creating point mutants to test mechanistic hypotheses (e.g., β-lactamase variants) [21] |

| HPLC with Rapid Sampling | Second-to-minute time resolution, quantitative detection | Monitoring substrate depletion and product formation in hysteretic enzymes [20] |

Integrated Analysis: Connecting Kinetic Signatures to Biological Mechanisms

Figure 2: Relationship between kinetic signatures and their underlying molecular mechanisms.

The connection between kinetic observations and molecular mechanisms becomes particularly evident when comparing burst phenomena across biological systems. In enzymatic systems, burst kinetics often reveal covalent intermediates or rate-limiting conformational changes [10] [20], while in gene regulation, transcriptional bursting reflects the stochastic nature of molecular interactions driving ON-OFF switching [22]. The emerging pattern across these diverse systems is that burst kinetics frequently signal rate-limiting steps with profound functional consequences—whether in antibiotic resistance evolution or drug metabolism.

The critical distinction between burst phase and steady-state analyses provides complementary insights into biological mechanisms. Pre-steady-state kinetics excels at identifying transient intermediates, elemental rate constants, and the molecular basis of rate-limiting steps, while steady-state kinetics offers efficient characterization of overall catalytic performance and inhibitor effects. The most powerful approaches strategically integrate both methodologies, using steady-state analysis to identify interesting phenomenological behavior and pre-steady-state methods to elucidate underlying mechanisms.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this distinction has practical implications. Enzyme engineers can exploit burst kinetics to identify mutations that change rate-limiting steps and create epistatic improvements [21]. Pharmacologists can understand how hysteretic enzyme behavior affects drug metabolism timelines [20]. Molecular biologists can connect transcription factor binding dynamics to transcriptional output control [22]. In each case, moving beyond steady-state analysis to examine transient kinetics provides the critical mechanistic insights needed to advance both basic understanding and applied research.

Kinetic analysis provides the foundation for understanding reaction mechanisms across chemical and biological sciences. This guide offers a comparative analysis of two fundamental kinetic approaches: the steady-state approximation and pre-steady-state burst phase analysis. While steady-state kinetics delivers macroscopic parameters for overall reactions, pre-steady-state kinetics reveals transient intermediates and individual steps within catalytic cycles. We objectively evaluate their complementary strengths, methodological requirements, and applications through experimental case studies spanning enzymology, drug delivery systems, and biotherapeutic development, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate analytical strategies for their specific investigations.

Kinetic analysis serves as the cornerstone for elucidating reaction mechanisms across diverse scientific domains, from chemical catalysis to biological processes. The steady-state approximation represents one of the most fundamental principles in chemical kinetics, enabling the simplification of complex multi-step reactions by assuming that reactive intermediates maintain constant concentrations during the majority of the reaction timeline [23] [24]. This approach has proven invaluable for determining overall kinetic parameters and deriving rate laws for complex reaction mechanisms.

In contrast, pre-steady-state kinetics captures the transient early phases of reactions, often revealing mechanistic details obscured under steady-state conditions. This approach is particularly valuable for detecting and characterizing reaction intermediates and identifying rate-limiting steps [10] [20]. Burst phase kinetics, a specific manifestation of pre-steady-state behavior, often signifies the accumulation and subsequent turnover of intermediates, providing critical insights into catalytic mechanisms [10] [20].

This guide examines the theoretical foundations, experimental methodologies, and practical applications of these complementary kinetic frameworks, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for mechanistic investigation across chemical and biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations

Steady-State Approximation

The steady-state approximation (SSA) applies to reaction mechanisms involving reactive intermediates that are generated and consumed in subsequent steps. This method assumes that the concentration of these intermediates remains constant throughout much of the reaction duration, meaning their rate of formation equals their rate of disappearance [23] [25] [24]. Mathematically, this is expressed as d[Int]/dt = 0, where [Int] represents the concentration of the intermediate species.

The SSA is particularly applicable to consecutive reactions where the first step is rate-limiting (k₁ << k₂), preventing significant accumulation of the intermediate product [24]. For a mechanism where A → I → P (where I is an intermediate and P is product), the SSA yields a relatively simple expression for product formation: [P] = [A]₀(1 - e^(-k₁t)) [24]. This stands in stark contrast to the complex exact solution, demonstrating the utility of SSA for simplifying kinetic analysis of multi-step mechanisms.

Pre-Steady-State and Burst Kinetics

Pre-steady-state kinetics describes the initial phase of a reaction before intermediates reach their steady-state concentrations. During this phase, reaction rates change rapidly as intermediates accumulate, providing a window into individual steps of the reaction mechanism [10] [20].

Burst kinetics refers to a specific pre-steady-state phenomenon characterized by a rapid initial release of product (the "burst") followed by a slower, linear steady-state phase. This behavior typically indicates that the first catalytic step (such as enzyme acylation or intermediate formation) is faster than subsequent steps (such as deacylation or intermediate breakdown) [10] [20]. The burst amplitude often correlates stoichiometrically with the concentration of active sites, while the steady-state rate reflects the rate-limiting step of the catalytic cycle.

Figure 1: Reaction mechanism underlying burst kinetics in a two-step catalytic process. The rapid formation and accumulation of the EP intermediate (k₃ > k₅) leads to an initial burst of P1 product, followed by slower steady-state turnover.

Experimental Methodologies

Steady-State Kinetic Analysis

Steady-state kinetic analysis typically involves measuring reaction velocities under conditions where substrate concentrations remain essentially constant (typically consumption of less than 5-10% of initial substrate) while varying substrate concentrations. For enzymatic reactions, this approach yields classic Michaelis-Menten parameters Km and Vmax, which provide macroscopic descriptions of enzyme-substrate interactions and catalytic efficiency [20].

Protocol: Standard Steady-State Kinetic Analysis

- Prepare a series of reactions with varying substrate concentrations while maintaining constant enzyme concentration

- Ensure initial linear rate conditions (typically monitoring ≤10% substrate depletion)

- Measure initial velocities for each substrate concentration

- Fit data to appropriate kinetic model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten equation for single-substrate reactions)

- Determine kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax, kcat) through nonlinear regression or linear transformations

For the hydrolysis of mirabegron by butyrylcholinesterase, steady-state analysis revealed Michaelian behavior with kcat = 1.6 min⁻¹ and Km = 3.9 μM at pH 7.0 and 25°C [20].

Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Analysis

Pre-steady-state kinetics requires specialized techniques capable of monitoring reactions on short timescales, often milliseconds to seconds, before the steady state is established.

Protocol: Pre-Steady-State Burst Kinetics Analysis

- Utilize rapid mixing/detection methods (stopped-flow, quenched-flow, or laser photolysis of caged compounds)

- Initiate reaction synchronously across all enzyme molecules

- Monitor product formation with high temporal resolution (millisecond timescale)

- Fit progress curves to integrated rate equations accounting for burst and steady-state phases

For BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of mirabegron, progress curves were analyzed using the integrated rate equation: [ [P] = v{ss}t + \frac{(vi - v{ss})(1 - e^{-k{obs}t})}{k{obs}} ] where (vi) and (v{ss}) represent initial and steady-state velocities, respectively, and (k{obs}) is the observed first-order rate constant for the transition between these phases [20].

Laser pulse photolysis of caged alanine has been employed to study SLC6A14 amino acid transporter kinetics with sub-millisecond resolution, revealing rapid transient currents decaying with a time constant of <1 ms [26].

Figure 2: Comparative experimental workflows for steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analyses, highlighting fundamental methodological differences.

Comparative Analysis of Kinetic Approaches

Direct Comparison of Methodologies

Table 1: Comparative analysis of steady-state versus pre-steady-state kinetic approaches

| Parameter | Steady-State Kinetics | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Time Scale | Seconds to hours | Milliseconds to seconds |

| Key Measured Parameters | Km, Vmax, kcat | Burst amplitude, kobs, transient rate constants |

| Information Obtained | Overall catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity | Individual rate constants, catalytic intermediates, rate-limiting steps |

| Experimental Complexity | Relatively simple | Technically demanding |

| Instrumentation | Standard spectrophotometers, HPLC | Stopped-flow, quenched-flow, laser photolysis |

| Data Analysis | Michaelis-Menten, linear transformations | Integrated rate equations, exponential fitting |

| Detection Limit | Nanomolar to micromolar | Often requires higher enzyme concentrations |

Case Study Comparisons

Table 2: Experimental kinetic parameters from case studies

| System | Method | Key Parameters | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of mirabegron [20] | Pre-steady-state | Burst phase: kcat = 7.3 min⁻¹, Km = 23.5 μMSteady-state: kcat = 1.6 min⁻¹, Km = 3.9 μM | Hysteretic behavior with slow equilibrium between enzyme forms E and E′ |

| Bovine heart phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase [10] | Pre-steady-state | Burst rate: 48 s⁻¹Turnover rate: 1.2 s⁻¹ | Phosphoenzyme intermediate with breakdown as rate-limiting step |

| SLC6A14 Amino Acid Transporter [26] | Pre-steady-state | Turnover rate: <1 ms transient current | Rapid substrate translocation not rate-limiting; Na+ binding likely rate-limiting |

| PLGA-based nanoparticle drug release [27] | Steady-state modeling | Weibull model: AIC = -36.37, OE = 7.24 | Best fit for multi-mechanistic drug release profiles |

Applications in Drug Development and Research

Biotherapeutic Stability Assessment

Kinetic modeling plays a crucial role in predicting biotherapeutic stability. First-order kinetic models combined with Arrhenius equations enable long-term stability predictions for various protein modalities, including IgG1, IgG2, bispecific IgG, Fc fusion proteins, scFv, nanobodies, and DARPins [28]. This approach reduces the number of parameters and samples required while enhancing prediction reliability. For aggregate formation in biotherapeutics, the reaction rate can be described by:

[ \frac{d\alpha}{dt} = v × A1 × \exp\left(-\frac{Ea1}{RT}\right) × (1-\alpha1)^{n1} × \alpha1^{m1} × C^{p1} + (1-v) × A2 × \exp\left(-\frac{Ea2}{RT}\right) × (1-\alpha2)^{n2} × \alpha2^{m2} × C^{p2} ]

where α represents the fraction of degradation products, A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is activation energy, and n, m are reaction orders [28].

Drug Release Kinetics

Mathematical modeling of drug release kinetics from delivery systems like PLGA nanoparticles employs both steady-state and dynamic approaches. Comparative analyses of release models have demonstrated that the Weibull model shows superior fit for multi-mechanistic release from PLGA-based systems, with mean Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) = -36.37 and mean overall error (OE) = 7.24 [27]. Alternative models including zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Hixson-Crowell, and Korsmeyer-Peppas provide varying degrees of accuracy depending on the specific drug delivery system and release mechanisms [27] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for kinetic analysis

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Nitrophenyl phosphate | Enzyme kinetics | Chromogenic substrate | Burst titration kinetics with phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase [10] |

| Mirabegron | Enzyme kinetics | Arylacylamide substrate | BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis studies [20] |

| PLGA polymers | Drug delivery | Nanoparticle matrix | Controlled release kinetics studies [27] [29] |

| Caged amino acids | Pre-steady-state kinetics | Photolabile precursors | Laser pulse photolysis studies of transporter kinetics [26] |

| Size exclusion chromatography columns | Biotherapeutic analysis | Aggregate quantification | Stability studies for various protein modalities [28] |

Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analyses represent complementary approaches to mechanistic investigation, each with distinct strengths and applications. The steady-state approximation provides simplified, practical parameters for overall reaction characterization, while pre-steady-state methods, particularly burst phase analysis, reveal intricate mechanistic details often masked under steady-state conditions. The selection between these approaches depends on the specific research questions, available instrumentation, and time scale of the process under investigation. As kinetic modeling continues to evolve, these frameworks remain essential tools for advancing our understanding of reaction mechanisms across chemical, biological, and pharmaceutical sciences.

Practical Techniques: Methods and Applications in Kinetic Analysis

Kinetic analysis provides the foundation for understanding reaction mechanisms and rates in biochemical and chemical processes. Within this field, the steady-state approximation represents a cornerstone methodology, offering a powerful framework for determining kinetic parameters such as Vmax and Km. This approach assumes that the concentration of enzyme-substrate complexes remains constant over time, as their rate of formation equals their rate of breakdown. The resulting mathematical treatment enables researchers to extract meaningful kinetic data from velocity measurements plotted against substrate concentration, typically yielding characteristic hyperbolic plots that can be linearized through various transformations.

This guide objectively compares steady-state kinetic analysis with its more time-resolved counterpart—pre-steady-state kinetics—by examining their fundamental principles, experimental requirements, data interpretation frameworks, and respective applications in basic research and drug development. While steady-state methods provide essential macroscopic parameters for enzyme characterization, pre-steady-state techniques reveal the transient microscopic events that underlie catalytic mechanisms. The complementary nature of these approaches provides a more complete picture of enzyme function when applied to research problems ranging from fundamental mechanistic studies to pharmaceutical development.

Core Principles and Data Features

Fundamental Characteristics of Steady-State Kinetics

Steady-state kinetics operates under the fundamental assumption that the concentration of enzyme-substrate intermediates remains constant during the measurement period. This occurs because the rate of ES complex formation equals its rate of decomposition to product and free enzyme. The methodology focuses on the initial rate of reaction (v0) measured during this steady-state phase, where product accumulation remains linear with time. These velocity measurements are then plotted against substrate concentration to generate a rectangular hyperbola, described mathematically by the Michaelis-Menten equation: v0 = (Vmax × [S])/(Km + [S]).

To extract the key kinetic parameters Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (substrate concentration at half Vmax), researchers typically employ linear transformations of the Michaelis-Menten equation. The most common linear plots include Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal), Eadie-Hofstee, and Hanes-Woolf plots. Each transformation offers distinct advantages and sensitivities to experimental error, with the Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/v versus 1/[S]) being the most widely recognized despite its susceptibility to error propagation at low substrate concentrations.

Key Experimental Data from Steady-State Analysis

The phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase study provides exemplary steady-state kinetic data, demonstrating how these methods yield quantitative parameters for enzyme characterization [10]. In this analysis, researchers determined an apparent Km of 0.38 mM for p-nitrophenyl phosphate hydrolysis alongside a Vmax that remained constant across multiple substrates. The study also established precise rate constants for the catalytic cycle, with phosphorylation proceeding at k2 = 540 s-1 and dephosphorylation at k3 = 36.5 s-1 under optimal conditions (pH 5.0, 37°C) [10].

Beyond these basic parameters, the investigation revealed fundamental thermodynamic properties through temperature-dependent measurements. The energy of activation for the enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis was determined to be 13.6 kcal/mol at pH 5.0 and 14.1 kcal/mol at pH 7.0 [10]. These values, combined with the observed constant product ratio across substrates and the enzyme-catalyzed 18O exchange between inorganic phosphate and water (kcat = 4.47 × 10-3 s-1 at pH 5.0, 37°C), provided compelling evidence for a phosphoenzyme intermediate with breakdown as the rate-limiting step [10].

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters from Phosphotyrosyl Protein Phosphatase Study

| Parameter | Value | Conditions | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apparent Km | 0.38 mM | pH 5.0, 37°C | Michaelis constant for p-nitrophenyl phosphate |

| True Ks | 6.0 mM | pH 5.0, 37°C | Actual enzyme-substrate dissociation constant |

| Phosphorylation rate (k2) | 540 s-1 | pH 5.0, 37°C with phosphate acceptors | Rate constant for phosphoenzyme formation |

| Dephosphorylation rate (k3) | 36.5 s-1 | pH 5.0, 37°C with phosphate acceptors | Rate constant for phosphoenzyme breakdown |

| Activation energy (pH 5.0) | 13.6 kcal/mol | - | Temperature dependence of hydrolysis |

| Activation energy (pH 7.0) | 14.1 kcal/mol | - | Temperature dependence at physiological pH |

| 18O exchange rate | 4.47 × 10-3 s-1 | pH 5.0, 37°C | Exchange between phosphate and water |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Steady-State Kinetic Protocol

The implementation of steady-state kinetic analysis follows a systematic experimental workflow designed to ensure accurate velocity measurements and reliable parameter estimation:

Reaction Mixture Preparation: Prepare a master mix containing buffer, cofactors, and any essential salts required for enzyme activity. Maintain this mixture at the desired assay temperature using a precision water bath or thermostatted block.

Substrate Dilution Series: Create a series of substrate concentrations typically spanning values below and above the anticipated Km. A recommended range is 0.2Km to 5Km to adequately define the hyperbolic curve.

Reaction Initiation: Start reactions by adding a small volume of enzyme solution to each substrate concentration. Use techniques that ensure rapid mixing while maintaining constant temperature throughout.

Initial Velocity Measurement: Monitor product formation or substrate depletion using appropriate detection methods (spectrophotometric, fluorometric, radiometric) during the linear phase of the reaction. The observation period should capture less than 5-10% of total substrate conversion to maintain initial rate conditions.

Data Collection: Record time-course data for each substrate concentration, ensuring sufficient data points to establish a linear fit with high confidence (typically R2 > 0.98).

Parameter Calculation: Plot initial velocity versus substrate concentration and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression. Alternatively, employ linear transformations for preliminary analysis and outlier identification.

This protocol emphasizes temperature control, precise timing, and verification of linearity throughout the measurement period—factors critical for obtaining reliable kinetic parameters.

Advanced Measurement Techniques

Beyond conventional spectrophotometric methods, sophisticated measurement technologies enable kinetic analysis in challenging systems. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has been adapted for velocity and temperature measurements in porous media convection studies, providing non-invasive quantification of flow dynamics [30]. This approach couples velocity vector measurements with temperature field mapping to analyze heat transfer in fluid-saturated systems, demonstrating how traditional kinetic principles extend to complex physical systems [30].

Similarly, X-ray Particle Tracking Velocimetry (XPTV) has emerged as a powerful technique for quantifying velocity fields in opaque systems where conventional optical methods fail [31]. By embedding tracer particles within materials and tracking their motion using X-ray imaging, researchers can resolve complex flow patterns and extract rheological information from polymer melts and other challenging media [31]. These advanced methodologies share the fundamental principle of steady-state analysis—measuring system properties under conditions where key variables remain constant over the observation period.

Table 2: Comparison of Velocity Measurement Techniques in Steady-State Analysis

| Technique | Application Scope | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional spectrophotometry | Enzyme kinetics, solution chemistry | N/A (bulk measurement) | Seconds to minutes | Limited to optically transparent systems |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Porous media, biological tissues | 10-100 μm | Seconds to minutes | Expensive instrumentation, requires specialized expertise |

| X-ray Particle Tracking Velocimetry (XPTV) | Polymer melts, opaque fluids | 1-10 μm | Millisecond to second | Requires tracer particles, radiation source |

| X-ray Rheography | Granular flows, amorphous materials | Single grain level | Sub-second | Complex setup, limited penetration depth |

Comparative Analysis: Steady-State vs. Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

Temporal Resolution and Information Content

The fundamental distinction between steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics lies in their temporal resolution and the corresponding information obtained about the catalytic mechanism. Steady-state methods observe the repetitive turnover of enzyme molecules over multiple catalytic cycles, providing an average view of the process. In contrast, pre-steady-state kinetics examines the first turnover events after rapid mixing of enzyme and substrate, typically occurring on millisecond timescales [10].

This temporal distinction directly determines the mechanistic information accessible through each approach. The phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase study exemplifies this difference, where pre-steady-state analysis revealed a rapid "burst" of p-nitrophenol formation (k = 48 s-1 at pH 7.0, 4.5°C) corresponding to the first enzyme turnover, followed by slower steady-state turnover (k = 1.2 s-1) representing the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle [10]. This burst phase provided direct evidence for a phosphoenzyme intermediate that would be invisible in conventional steady-state analysis alone.

Experimental Requirements and Technical Considerations

The implementation of pre-steady-state kinetics demands specialized equipment and more complex experimental designs compared to steady-state approaches. Rapid mixing techniques such as stopped-flow or quenched-flow instrumentation are essential to initiate reactions homogeneously and observe events on millisecond timescales. These systems require sophisticated detection methods including rapid spectrophotometry, fluorescence, or chemical quenching followed by product analysis.

Conversely, steady-state kinetics can typically be performed with standard laboratory equipment—spectrophotometers, pipettes, and temperature control systems—available in most biochemical laboratories. The minimal equipment requirements and straightforward data interpretation make steady-state methods more accessible for routine enzyme characterization, initial inhibitor screening, and comparative activity assays across enzyme variants or conditions.

Data Interpretation and Parameter Extraction

The mathematical treatment of steady-state kinetic data focuses primarily on two fundamental parameters—Km and Vmax—which provide essential information about substrate affinity and catalytic capacity. These parameters serve as valuable indicators for comparing enzyme variants, assessing inhibitor potency, and predicting metabolic flux in biochemical pathways. The linear transformations of Michaelis-Menten kinetics further facilitate the identification of inhibition patterns (competitive, noncompetitive, uncompetitive) through characteristic changes in the plots.

Pre-steady-state analysis yields more detailed information about individual rate constants within the catalytic cycle, including substrate binding (kon), chemical transformation (kchem), and product release (koff). The phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase study demonstrated how this approach can distinguish between phosphorylation (k2 = 540 s-1) and dephosphorylation (k3 = 36.5 s-1) rates, identifying the latter as the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle [10]. This level of mechanistic detail proves invaluable for understanding enzyme specificity, designing transition-state analogs, and developing targeted inhibitors.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Steady-State and Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Methods

| Characteristic | Steady-State Kinetics | Pre-Steady-State Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Time resolution | Seconds to minutes | Milliseconds to seconds |

| Observation window | Multiple catalytic cycles | First turnover and transient phases |

| Primary parameters obtained | Km, Vmax, kcat | Individual rate constants for each catalytic step |

| Key mechanistic information | Overall catalytic efficiency, inhibition patterns | Reaction intermediates, rate-limiting steps |

| Equipment requirements | Standard spectrophotometer, temperature controller | Stopped-flow apparatus, rapid detection systems |

| Sample consumption | Moderate to low | Typically higher due to rapid mixing requirements |

| Data interpretation complexity | Low to moderate | High, requires sophisticated modeling |

| Primary applications | Enzyme characterization, inhibitor screening, functional comparisons | Mechanistic studies, elucidation of catalytic pathways |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of kinetic analysis requires specific reagents and materials tailored to each methodology. The following table details essential components for both steady-state and pre-steady-state approaches, along with their critical functions in kinetic experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Kinetic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Steady-State Applications | Pre-Steady-State Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-purity enzyme preparations | Catalytic component free from contaminants | Essential for accurate kcat determination | Critical for observing unimpeded transient kinetics |

| Defined substrate solutions | Reactant at precise concentrations | Km determination, velocity measurements | Rapid mixing at known concentrations |

| Stopped-flow apparatus | Rapid mixing and observation | Limited use | Essential for millisecond time resolution |

| Spectrophotometric detection systems | Monitoring reaction progress | Standard cuvette-based systems | Rapid detection capabilities required |

| Temperature control systems | Maintaining constant assay temperature | Water baths, thermostatted cells | Jacketed flow systems, rapid temperature equilibration |

| Chemical quench agents | Stopping reactions at precise times | Limited use in standard protocols | Essential for quenched-flow experiments |

| Tracer particles | Flow visualization in complex systems | Not typically used | Required for XPTV measurements in opaque fluids [31] |

| Specialized buffers | pH maintenance, cofactor provision | Standard biochemical buffers | Often requires degassing for flow systems |

Visualization of Methodologies

Steady-State Kinetic Analysis Workflow

Comparative Experimental Setups

Steady-state kinetic analysis, with its focus on velocity measurements and linear transformations, remains an indispensable methodology in enzyme characterization and inhibitor screening. The approach provides robust parameters (Km, Vmax) that enable quantitative comparisons across enzyme variants, conditions, and potential therapeutic agents. The methodology's accessibility, relatively simple implementation, and well-established theoretical framework ensure its continued relevance in biochemical research and drug development.

However, the comprehensive understanding of enzymatic mechanisms often requires integration of both steady-state and pre-steady-state approaches. As demonstrated in the phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase study [10], pre-steady-state kinetics reveals transient intermediates and individual rate constants that remain obscured in conventional steady-state analysis. The complementary application of these methodologies, enhanced by advanced measurement technologies like MRI [30] and XPTV [31], provides a more complete picture of catalytic mechanisms—from initial substrate binding to final product release.

This synergistic approach proves particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development, where detailed mechanistic understanding guides the design of specific, potent enzyme inhibitors. By combining the macroscopic perspective of steady-state analysis with the microscopic resolution of pre-steady-state techniques, researchers can accelerate the development of therapeutic agents while deepening fundamental knowledge of biochemical catalysis.

Enzymology, the branch of biochemistry dedicated to understanding enzyme function, relies heavily on kinetic analysis to unravel catalytic mechanisms. Traditional steady-state kinetics, which studies enzymes under conditions of repeated turnover, provides essential parameters like ( k{cat} ) and ( Km ) but offers limited insight into the individual steps comprising a catalytic cycle [32]. This approach measures the slowest step in the pathway but obscures faster intermediate steps that often hold the key to understanding enzymatic efficiency and specificity [32]. To address this limitation, pre-steady-state kinetics emerged as a powerful methodology for resolving the transient phases of enzyme reactions, typically occurring within milliseconds to seconds after mixing enzyme with substrate [32].

Pre-steady-state kinetic studies aim to resolve each individual step in a catalytic reaction sequence by rapidly mixing enzyme and substrate and monitoring changes in the system over time [32]. Among the most valuable tools for these investigations are rapid quench-flow and stopped-flow instruments, which enable researchers to capture reaction intermediates and measure fast rate constants that are inaccessible through manual mixing methods [33]. These techniques have become indispensable for elucidating complex enzymatic mechanisms, including the formation and breakdown of phosphoenzyme intermediates [10] and the catalytic strategies of ribozymes [33]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these essential instruments, their applications, and their performance relative to alternative approaches in the context of modern kinetic analysis.

Understanding Pre-Steady-State Kinetics: Fundamental Concepts

Theoretical Foundation: Beyond Michaelis-Menten

While steady-state kinetics follows the Michaelis-Menten equation for the simplest enzyme mechanism (( E + S \leftrightarrow ES \rightarrow E + P )), actual enzyme catalytic cycles typically involve multiple intermediate steps (( E + S \leftrightarrow ES1 \rightarrow ... \rightarrow ESn \rightarrow I1 \rightarrow ... \rightarrow In \rightarrow EP1 \rightarrow ... \rightarrow EPn \rightarrow E + P )) [32]. The individual elementary steps in these mechanisms often proceed with first-order rate constants between ( 10^1 ) and ( 10^6 ) s⁻¹, while bimolecular rate constants range between ( 10^4 ) and ( 10^{10} ) M⁻¹s⁻¹ [32]. These rapid transitions cannot be captured by conventional steady-state approaches, necessitating specialized techniques that can operate on millisecond timescales.

The pre-steady-state phase represents the period before the enzyme-substrate complex reaches steady-state concentration, typically characterized by a "burst" of product formation that corresponds to the first turnover cycle [10]. For instance, in studies of bovine heart phosphotyrosyl protein phosphatase, a transient pre-steady-state burst of p-nitrophenol was observed with a rate constant of 48 s⁻¹, followed by slower steady-state turnover with a rate constant of 1.2 s⁻¹ [10]. Such burst kinetics provide direct evidence for the formation of covalent enzyme intermediates and allow researchers to isolate and characterize these transient species.

Advantages Over Steady-State Approaches

Pre-steady-state kinetics offers several distinct advantages for mechanistic enzymology:

- Identification of Intermediates: Allows direct observation and characterization of catalytic intermediates that are invisible in steady-state measurements [32].

- Elementary Rate Constants: Enables determination of individual rate constants for specific steps in the catalytic cycle rather than composite parameters [10].

- Chemical Mechanism Elucidation: Provides insights into chemical steps such as phosphotransfer, proton transfer, and conformational changes that often occur faster than overall turnover [32].

- Minimized Artifacts: Studying reactions under single-turnover conditions avoids complications from product inhibition, substrate depletion, and enzyme instability during multiple turnovers [33].

Diagram 1: Enzyme catalytic pathway showing transient intermediates detectable only in pre-steady-state phase.

Rapid Quench-Flow Instruments

Rapid quench-flow (RQF) instruments operate by rapidly mixing enzyme and substrate solutions, allowing the reaction to proceed for a precisely defined time period (milliseconds to seconds), then forcibly quenching the reaction with a chemical agent such as acid, base, or denaturant [33]. The quenched samples are collected and analyzed offline, typically using separation techniques like polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with appropriate detection methods [33].

Key Components and Operation:

- Drive System: Stepping motor-controlled drive plate that forces solutions through the instrument with high precision [33].

- Mixing Chamber: Where enzyme and substrate solutions initially combine to initiate the reaction.

- Reaction Loops: Tubes of varying lengths through which the mixed solution flows, determining the reaction time for short time points (≤100 ms) [33].

- Quench Mixer: Where quenching solution is introduced to stop the reaction at precise time points.