Solving Substrate Solubility in Kinetic Assays: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Strategies for Drug Development

Substrate solubility is a critical, yet often overlooked, parameter that directly impacts the reliability and reproducibility of kinetic assays in enzymology and drug discovery.

Solving Substrate Solubility in Kinetic Assays: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Strategies for Drug Development

Abstract

Substrate solubility is a critical, yet often overlooked, parameter that directly impacts the reliability and reproducibility of kinetic assays in enzymology and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing this ubiquitous challenge. It begins by establishing the foundational science of solubility and its direct consequences on assay parameters like KM and kcat. The piece then transitions to practical, methodological solutions for enhancing solubility, including chemical modifications and advanced formulation techniques. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers a systematic framework for diagnosing and optimizing problematic assays, while the final section outlines rigorous protocols for validating solubility and comparatively analyzing different methodological approaches. By integrating traditional techniques with cutting-edge computational tools, this resource aims to equip scientists with a holistic strategy to ensure accurate kinetic data from lead optimization to development.

The Solubility Imperative: Understanding the Fundamental Impact on Kinetic Data

Why Solubility is a Rate-Limiting Step in Drug Discovery and Development

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why is solubility so critical in early drug discovery? Solubility is a fundamental property that directly influences a drug's absorption into the systemic circulation. After oral administration, a drug must first dissolve in gastrointestinal fluids before it can permeate the intestinal wall. Poor solubility often results in low and variable bioavailability, meaning the drug does not reach its target site in sufficient concentration to be therapeutically effective. This makes it a primary rate-limiting step in developing new pharmaceuticals. [1]

2. A significant portion of our drug pipeline consists of BCS Class II compounds. What are the main strategies to enhance their solubility and dissolution? A large number of new chemical entities (70-90%) fall into the BCS Class II category, characterized by high permeability but poor solubility. For these drugs, the rate of dissolution is often the slowest step governing overall absorption. Key strategies to overcome this include:

- Particle Size Reduction (e.g., Nano-suspensions): Increasing the surface area of the drug particles to enhance dissolution rate.

- Complexation: Using cyclodextrins or other agents to form soluble complexes with the drug molecule.

- Advanced Carrier Systems: Employing Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) like MIL-101(Cr) for in-situ loading, which can dramatically increase drug loading and reclassify drugs from "poorly soluble" to "soluble". [1] [2]

3. How can we accurately predict solubility to accelerate synthetic planning? Traditional methods like the Abraham Solvation Model have limitations in accuracy. Modern approaches use machine learning models trained on large, curated datasets. For instance, the FastSolv model uses static molecular embeddings to predict how well a molecule will dissolve in hundreds of different organic solvents, and it accounts for the effect of temperature. Using such models allows chemists to choose the optimal solvent for a reaction before moving to the lab, speeding up development. [3]

4. When designing a kinetic assay, how do I choose between a soluble or insoluble substrate? The choice is dictated by your analytical goal:

- Use Soluble Substrates for quantification in liquid-phase assays (e.g., cuvette or multi-well plate formats). They are ideal for real-time kinetic studies, ELISA, and high-throughput screening because the dissolved product is compatible with optical detection (absorbance, fluorescence). [4]

- Use Insoluble Substrates for localization studies. The precipitated product remains at the site of enzyme activity, making them essential for techniques like Western blots, zymograms, immunohistochemistry, and microbial screening on agar plates. [4]

5. We are characterizing a covalent inhibitor. Why do our IC50 values seem inconsistent, and how should we properly evaluate its potency? For irreversible covalent inhibitors, inhibition is time-dependent. A single IC50 measurement is insufficient and can be misleading because it doesn't distinguish between strong binding with slow reaction and weak binding with fast reaction. A complete characterization requires deriving two key parameters:

- KI: The inhibition constant, representing the affinity for the initial non-covalent binding.

- kinact: The maximum rate of the irreversible inactivation. Proper evaluation requires time-dependent assays, such as the Kitz & Wilson method for continuous assays or incubation time-dependent IC50 measurements for discontinuous assays, to obtain a full kinetic profile. [5]

Quantitative Data on Solubility Enhancement Technologies

The following table summarizes data on novel technologies used to improve the solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs.

Table 1: Strategies for Solubility Enhancement of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs

| Technology / Approach | Mechanism of Action | Example Results / Data | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nano-Suspensions [1] | Particle size reduction to increase surface area for dissolution. | Applied to 40% of existing drugs and 70-90% of drugs in development. | Can be easily formulated into various dosage forms. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MIL-101(Cr)) [2] | In-situ drug loading onto a porous carrier via π–π stacking and H-bonding. | Loads of 904.7 mg/g Ibuprofen; solubility increased to 4.1-7.3 g/L in PBS. | Green synthesis method; reclassifies drugs from "poorly soluble" to "soluble". |

| Machine Learning (FastSolv Model) [3] | Predicts solubility in organic solvents using numerical molecular representations. | Predictions are 2-3x more accurate than previous models (SolProp). | Accelerates synthetic planning; helps identify less hazardous solvents. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Characterizing an Irreversible Covalent Inhibitor using a Continuous Assay (Kitz & Wilson Method) [5]

This protocol is used to determine the kinetic parameters KI and kinact for an irreversible inhibitor when a continuous, real-time activity assay is available.

- Assay Setup: Prepare a series of reactions containing a fixed concentration of the target enzyme and varying concentrations of the covalent inhibitor. Include a positive control with no inhibitor.

- Initiation: Start the reaction by adding the enzyme's substrate. The substrate concentration should be saturating ([S] >> KM) to ensure the initial velocity directly reflects the concentration of active enzyme.

- Continuous Monitoring: Immediately begin monitoring product formation or substrate consumption (e.g., via absorbance or fluorescence) in real-time using a plate reader or spectrophotometer.

- Data Analysis:

- For each inhibitor concentration, plot the product formation over time. The slope of this curve will decrease as more enzyme is inactivated.

- At each time point, the observed reaction rate (v) is proportional to the concentration of active enzyme remaining.

- The observed rate constant for inactivation (kobs) at each inhibitor concentration is determined by fitting the progress curves to an exponential decay function.

- Plot kobs against the inhibitor concentration [I]. Fit this data to the following equation to derive KI and kinact: kobs = (kinact * [I]) / (KI + [I])

Protocol 2: Enhancing Drug Solubility via In-Situ Loading onto MIL-101(Cr) [2]

This green chemistry protocol describes incorporating a BCS Class II drug during the synthesis of a metal-organic framework carrier.

- Reagent Preparation: Dissolve Chromium (III) salt (e.g., Cr(NO3)3) and terephthalic acid in a solvent system of acetic acid and water. This replaces toxic hydrofluoric acid traditionally used.

- Drug Addition: Add the poorly soluble drug (e.g., Ibuprofen, Ketoprofen, Felodipine) to the mixture.

- Crystallization: Carry out the solvothermal reaction under controlled temperature and pressure to crystallize the MIL-101(Cr) MOF with the drug molecule incorporated within its pores.

- Isolation and Washing: Recover the solid product by filtration or centrifugation and wash to remove any unreacted precursors or drug loosely bound to the surface.

- Characterization: Confirm successful drug loading using techniques like:

- Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM): To observe morphology.

- Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Analysis: To confirm a reduction in surface area, indicating pore occupancy.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): To analyze crystallinity.

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): To identify drug-carrier interactions.

- Dissolution Testing: Perform drug release studies in a medium like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to quantify the enhancement in solubility and dissolution rate.

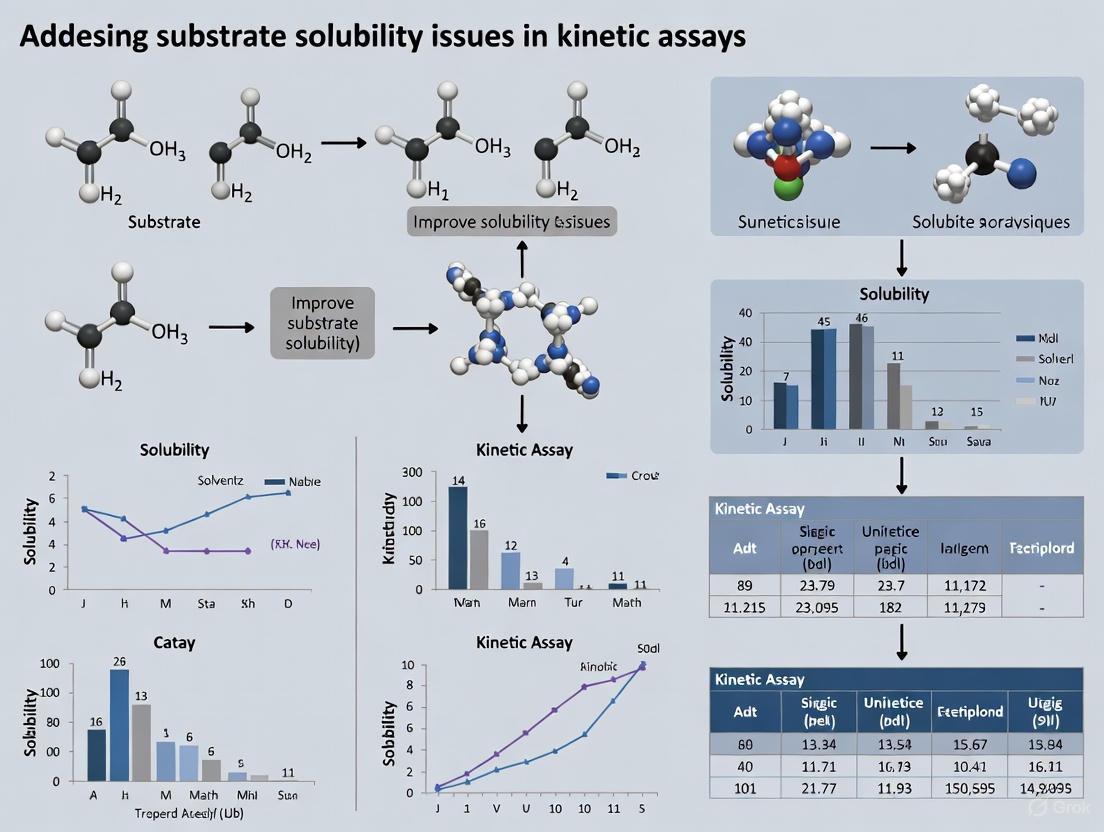

Workflow Visualization

Solubility Enhancement Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Solubility and Kinetic Assay Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Organic Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, Acetone) | Used in chemical synthesis and solubility screening. Machine learning models can help select the most effective and least hazardous options. [3] |

| Soluble Chromogenic/Fluorogenic Substrates | Generate a dissolved colored or fluorescent product. Essential for quantitative, real-time kinetic assays in solution (e.g., protease or hydrolase activity profiling). [4] |

| Insoluble Precipitating Substrates | Yield a colored precipitate at the site of enzyme activity. Critical for localization studies in Western blots, zymograms, and immunohistochemistry. [4] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (e.g., MIL-101(Cr)) | Porous crystalline materials used as advanced carriers to dramatically increase the apparent solubility and loading capacity of poorly soluble drugs. [2] |

| Covalent Inhibitors with Electrophilic Warheads | Contain a reactive functional group that forms a slow-reversible or irreversible bond with a target protein, leading to prolonged pharmacodynamic effects. Require specialized kinetic evaluation. [6] [5] |

Core Concepts FAQ

What is the fundamental difference between kinetic and thermodynamic solubility?

Kinetic Solubility measures the concentration at which a compound, initially fully dissolved in an organic solvent like DMSO, begins to precipitate out when added to an aqueous buffer. It represents the solubility of the fastest-precipitating, often amorphous, form of the compound and is typically used for high-throughput screening in early drug discovery [7] [8] [9].

Thermodynamic Solubility measures the maximum concentration of a solid crystalline compound that can remain dissolved in a solvent under equilibrium conditions—where the dissolved and undissolved solid are in equilibrium. This is considered the "true" solubility of the most stable crystal form and is critical for later-stage development and formulation [10] [7] [8].

When should each type of solubility assay be used in the drug discovery workflow?

The choice between kinetic and thermodynamic solubility assays depends on the stage of research and the specific information required. The following table outlines the typical applications:

Table 1: Application of Solubility Assays in Drug Discovery and Development

| Assay Type | Stage of R&D | Primary Purpose | Typical Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Solubility | Early Discovery (Lead Identification & Optimization) [7] | High-throughput ranking of compound libraries; guiding medicinal chemistry for structure-activity relationships (SAR) [11] [9]. | Classification (e.g., Low <10 µg/mL, Moderate 10-60 µg/mL, High >60 µg/mL) [11]. |

| Thermodynamic Solubility | Late-Stage Preclinical Development [7] | Formulation development; setting dissolution specifications; providing data for regulatory submissions (e.g., IND) [7] [12]. | Precise solubility value (e.g., in µg/mL) for the most stable crystal form [10]. |

Why might my kinetic solubility values be misleadingly high compared to thermodynamic values?

This common discrepancy occurs because the two methods measure different physical states of the compound. Kinetic solubility assays often measure the solubility of the amorphous form of the compound, which has higher energy and therefore higher apparent solubility. In contrast, thermodynamic solubility assays measure the solubility of the most stable crystalline form, which has lower energy and thus lower solubility. Relying solely on kinetic solubility can lead to over-optimism about a compound's developability [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Low or Variable Solubility Results

Problem: Measured solubility values are very low, variable, or inconsistent with other assay data.

Solutions:

- Confirm Analytical Method: For very low solubility compounds, switch from HPLC-UV to a more sensitive method like LC-MS/MS. The lower limit of quantification for LC-MS/MS can be as low as 1 nM, allowing for more accurate detection of low concentrations [11].

- Address Non-Specific Adsorption: Use low-binding consumables throughout the process, such as 96-well low-binding filter plates or regenerated cellulose filter membranes. For sample treatment, consider adding additives like organic solvents, surfactants, or proteins to minimize compound adsorption to surfaces [11].

- Verify Solid State Form: In thermodynamic assays, use techniques like polarized-light microscopy to confirm whether the measured solubility corresponds to a crystalline or amorphous phase. This helps explain discrepancies and ensures data reliability [10].

Issue 2: Managing Compound Stability During Solubility Assessment

Problem: The compound degrades during the solubility experiment, leading to inaccurate results.

Solutions:

- Detect Degradation: Employ chromatographic methods (e.g., HPLC-UV) with full-wavelength scanning to identify the presence of specific degradation peaks. Using LC-UV-MS in series can help confirm the identity and purity of the target peak [11].

- Optimize Conditions: If instability is detected, assess unstable factors and optimize experimental conditions, such as adjusting the pH of the buffer media or reducing the incubation time if appropriate [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Kinetic Solubility Determination

This protocol is based on the high-throughput shake-flask method commonly used in early discovery [11] [13].

Method Overview: A compound dissolved in DMSO is diluted into an aqueous buffer system, and the concentration at which precipitation occurs is determined.

Table 2: Key Parameters for a Standard Kinetic Solubility Assay

| Parameter | Typical Condition | Notes / Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Concentration | 200 µM (routine) | Can be adjusted based on project needs. |

| Starting Material | Compound in DMSO stock solution (e.g., 10 mM) | - |

| Percentage of DMSO | 2% (routine) | Other ratios (e.g., 1%) can be used. |

| Media | Aqueous buffer (e.g., pH 7.4 phosphate buffer); Biorelevant media. | pH can be adjusted to simulate different physiological environments. |

| Incubation Equilibration Time | 2 hours (common) [11] | 24 hours is also used. |

| Equilibration Temperature | Room Temperature or 37 °C | 37 °C is used to simulate physiological temperature. |

| Detection Method | Nephelometry (turbidimetry) [9], HPLC-UV, or LC-MS/MS | Nephelometry detects precipitation; chromatographic methods quantify concentration. |

| Compound Required | ~30 µL of 10 mM DMSO stock [11] | - |

Workflow Diagram: Kinetic Solubility Assay

Protocol for Thermodynamic Solubility Determination

This protocol uses the classic shake-flask method, considered the gold standard for obtaining equilibrium solubility [11] [14].

Method Overview: An excess of solid compound is added to a solvent and agitated until equilibrium is reached between the dissolved and undissolved material.

Table 3: Key Parameters for a Standard Thermodynamic Solubility Assay

| Parameter | Typical Condition | Notes / Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material | Solid powder of the compound [11] | The solid-state form (polymorph) is critical. |

| Sample Amount | ~2 mg solid (for assay) + 1 mg (for standard curve) [11] | - |

| Media | Aqueous buffer system; Biorelevant media; Organic solvent. | - |

| Incubation Equilibration Time | 24 hours (routine) [11] [9] | Must be sufficient to reach equilibrium. |

| Equilibration Temperature | Room Temperature or 37 °C [11] | - |

| Agitation | Shaking (e.g., shake-flask) [11] | - |

| Separation | Centrifugation and/or Filtration [14] | - |

| Analytical Method | HPLC-UV/HPLC-ELSD/LC-MS/MS [11] | Used to quantify the concentration in the saturated solution. |

Workflow Diagram: Thermodynamic Solubility Assay

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials and their functions for conducting reliable solubility assays.

Table 4: Essential Materials for Solubility Testing

| Item / Reagent | Function in the Assay | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Universal solvent for creating high-concentration stock solutions of research compounds for kinetic solubility assays. [7] [8] | Use high-quality, anhydrous DMSO. Keep concentrations low (e.g., 1-2%) in final aqueous buffers to minimize its effect on solubility. |

| Aqueous Buffer Systems (e.g., Phosphate Buffer) | Provides a stable, physiologically relevant pH environment (e.g., pH 7.4) for solubility measurement. [11] [9] | Essential for ionizable compounds, as their solubility is pH-dependent. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids (Biorelevant Media) | Media such as FaSSIF (Fasted State Simulated Intestinal Fluid) mimic the in vivo environment of the GI tract, providing a more predictive measure of absorption potential. [11] [7] | Used in later stages to forecast in vivo behavior. |

| Low-Binding Consumables (Plates, Filters) | Tubes, plates, and filter membranes treated to minimize non-specific adsorption of the test compound to surfaces. [11] | Critical for obtaining accurate results with lipophilic or sticky compounds that can adhere to container walls. |

| Positive Control Compounds | Compounds with known and verified solubility ranges used to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the experimental operation. [11] [9] | Examples include Nicardipine (for kinetic) and Haloperidol (for thermodynamic). They are run alongside test compounds for quality control. |

The Direct Link Between Poor Solubility and Erroneous Kinetic Parameters (KM, kcat)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does poor substrate solubility directly lead to inaccurate measurements of KM and kcat? Poor substrate solubility creates a discrepancy between the nominal substrate concentration you add to the assay and the actual concentration of bioavailable substrate in solution [15] [16]. If a compound precipitates, it is unavailable for the enzyme to bind. Kinetic analysis, based on the Michaelis-Menten model, assumes that the stated substrate concentration is accurate and fully available [15] [17]. When this is not true, the calculated parameters are fundamentally flawed. A seemingly low enzyme velocity might be misinterpreted as a high KM (low affinity) or low kcat (slow catalytic rate), when in reality, the enzyme is simply starved for soluble substrate.

Q2: What are the typical experimental signs that poor solubility is affecting my kinetic assay? Several red flags can indicate solubility issues:

- Non-linear or inconsistent progress curves: The reaction rate decreases rapidly before a significant amount of product would be expected to form, not due to enzyme inactivation but because the local, soluble substrate is depleted [18].

- Failure to achieve saturation: The reaction velocity (v0) does not plateau (Vmax is not reached) even at high nominal substrate concentrations [17].

- High variability in replicate measurements: Slight changes in temperature, mixing, or buffer composition can cause dissolved substrate to precipitate or precipitate to re-dissolve, leading to inconsistent rates between replicates.

- Observed cloudiness or precipitation: Visible precipitate in the assay solution is a clear indicator of exceeding the compound's solubility limit.

Q3: Beyond KM and kcat, what other aspects of enzymology are compromised by poor solubility? Poor solubility can skew the results of many advanced enzyme studies, including:

- Mechanistic studies: Determining whether a reaction follows a sequential or ping-pong mechanism (e.g., for multi-substrate enzymes like NIS synthetases) requires accurate substrate concentration curves [19]. Solubility issues can obscure the true mechanism.

- Inhibition studies: The potency (IC50, Ki) and mechanism of an inhibitor (competitive, non-competitive) can be mischaracterized if the substrate or inhibitor itself has limited solubility [20].

- High-throughput screening (HTS): Poorly soluble compounds are a major source of false positives and false negatives in drug discovery campaigns, as they can form colloidal aggregates that non-specifically inhibit enzymes [16].

Q4: What practical steps can I take to improve substrate solubility in my assay buffer?

- Use co-solvents: A small percentage of a water-miscible organic solvent like DMSO, ethanol, or acetone can significantly enhance solubility. It is critical to keep the concentration low (typically <5%) to avoid denaturing the enzyme and to include the same solvent concentration in all standards and blanks [16].

- Employ solubilizing agents: Detergents (e.g., Triton X-100) or cyclodextrins can encapsulate hydrophobic molecules, keeping them in solution without drastically altering the aqueous environment of the enzyme [21].

- Modify buffer conditions: Adjusting pH, ionic strength, or changing the buffer system itself can sometimes improve solubility. However, any change must be validated to ensure it does not adversely affect enzyme activity [15] [22].

- Consider substrate analogs: If available, a more soluble analog of the substrate can sometimes be used, though this must be done with caution as it may alter the enzyme's kinetic mechanism [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Solubility Issues

This guide outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and address substrate solubility problems in kinetic assays.

Step 1: Proactively Determine Substrate Solubility Before starting kinetic experiments, determine the solubility limit of your substrate under exact assay conditions (buffer, pH, temperature) [16].

- Protocol: Prepare a series of substrate stock solutions in DMSO and dilute them into your assay buffer to cover the concentration range you plan to use. After incubation at the assay temperature, visually inspect for cloudiness or use light-scattering methods (e.g., nephelometry) to detect precipitate. The solubility limit is the highest concentration that remains clear.

Step 2: Design Kinetic Assays with Solubility in Mind

- Stay Below the Limit: Ensure all nominal substrate concentrations in your assay are below the experimentally determined solubility limit.

- Use Continuous Assays: Whenever possible, use continuous assays that monitor the reaction progress in real-time [18]. The shape of the progress curve is a powerful diagnostic tool for identifying solubility-related depletion, as shown in the diagram below.

Step 3: Analyze Data with a Critical Eye

- Inspect Progress Curves: Do not assume linearity. Use kinetic modeling to analyze the entire progress curve, which can help account for non-ideal behavior, including substrate depletion [18].

- Validate Parameters: Be skeptical of kinetic parameters that do not make biochemical sense. Compare your results with literature values, and if they differ significantly, investigate solubility as a potential cause.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the troubleshooting process for a kinetic assay suspected of being affected by poor solubility.

Quantitative Impact of Solubility on Measured Parameters

The table below summarizes how a mismatch between nominal and soluble substrate concentration systematically biases the derived kinetic parameters.

| Parameter | Definition | Impact of Poor Solubility | Erroneous Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| KM (Michaelis Constant) | Apparent substrate concentration at half Vmax; measures enzyme affinity [15] [17]. | Artificially Inflated. The enzyme requires a higher nominal [S] to reach half Vmax because the bioavailable [S] is lower than assumed. | The enzyme appears to have a lower binding affinity for the substrate than it truly does. |

| kcat (Turnover Number) | Maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time [17]. | Artificially Lowered. The enzyme cannot achieve its true maximum velocity because it is not saturated with soluble substrate. | The enzyme's catalytic efficiency appears slower than it truly is. |

| kcat/KM (Specificity Constant) | Measure of catalytic efficiency for a given substrate [20]. | Artificially Lowered. This composite parameter is skewed by both an inflated KM and a lowered kcat. | The enzyme's overall efficiency and specificity for the substrate are significantly underestimated. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Kinetic Solubility via Nephelometry

This protocol provides a method for quantitatively assessing the kinetic solubility of a substrate, which is the relevant solubility for most enzymatic assays where compounds are added from a DMSO stock [16].

Objective: To determine the concentration at which a substrate precipitates in assay buffer upon dilution from a DMSO stock solution.

Materials:

- Substrate stock solution (e.g., 10-100 mM in DMSO)

- Assay buffer (identical to that used in kinetic experiments)

- Nephelometer or plate reader capable of measuring light scattering (often at ~600 nm)

- Multi-well plate or clear cuvettes

- Piperettes and vortex mixer

Procedure:

- Preparation: Serially dilute the substrate stock solution in DMSO to create a range of concentrations.

- Dilution into Buffer: Add a fixed, small volume of each DMSO stock (e.g., 1-5 µL) to a larger volume of assay buffer (e.g., 1 mL) in a cuvette or plate well. The final DMSO concentration should be consistent and low (≤1%).

- Mixing and Incubation: Mix thoroughly and incubate for 10-15 minutes at the temperature used for your kinetic assays.

- Measurement: Measure the nephelometry signal (turbidity) for each sample. A blank consisting of buffer with the same percentage of DMSO should be used for baseline subtraction.

- Analysis: Plot the nephelometry signal versus the nominal substrate concentration. The point where the signal significantly increases above the baseline indicates the kinetic solubility limit.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions for addressing solubility challenges in enzyme kinetics.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Addressing Solubility |

|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A polar aprotic solvent used to create high-concentration stock solutions of poorly soluble compounds. It allows for precise dispensing before dilution into aqueous buffers [16]. |

| Cyclodextrins (e.g., HP-β-CD) | Cyclic oligosaccharides that form soluble inclusion complexes with hydrophobic molecules, acting as molecular carriers to enhance apparent solubility in aqueous buffers [21]. |

| Detergents (e.g., Triton X-100) | Amphipathic molecules that form micelles in solution. They can solubilize hydrophobic substrates within the micelle core, preventing precipitation [21]. |

| Nephelometer | An instrument that measures the scattering of light by particles in a solution. It is used to quantitatively determine the solubility limit of a compound by detecting the onset of precipitation [16]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Statistical tools that allow for the efficient optimization of multiple assay parameters (e.g., buffer pH, ionic strength, co-solvent percentage) simultaneously to find conditions that maximize both solubility and enzyme activity [22]. |

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) is a fundamental framework used in drug development to categorize active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) based on their aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability [23] [24]. This system provides a scientific approach for predicting drug absorption in humans and is a critical tool for researchers and regulatory bodies, including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) [23] [25]. The primary goal of the BCS is to determine when in vivo bioequivalence studies can be replaced by in vitro dissolution tests, a process known as "biowaiver" [23]. For scientists conducting kinetic assays, understanding a compound's BCS class is the first step in anticipating and troubleshooting significant experimental challenges, particularly those related to substrate solubility.

BCS Classification of Drugs

According to the BCS, drug substances are classified into four distinct classes based on two key properties: solubility and permeability [23] [24]. The classification and its implications for drug absorption are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: BCS Drug Classification and Characteristics

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Absorption Challenge | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | No absorption challenges; well-absorbed | Metoprolol, Paracetamol [24] |

| Class II | Low | High | Solubility/dissolution rate-limited | Glibenclamide, Ketoconazole [23] [24] |

| Class III | High | Low | Permeability rate-limited | Cimetidine [24] |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Poor bioavailability; significant challenges for absorption | Bifonazole, Furosemide, Bosutinib [26] [24] |

Defining the Class Boundaries

- Solubility: A drug is deemed highly soluble when the highest dose strength is soluble in 250 mL or less of aqueous media over a pH range of 1 to 6.8 [23] [24]. This volume is derived from typical bioequivalence study protocols.

- Permeability: A drug is considered highly permeable when the extent of absorption in humans is determined to be 90% or more [23] (or 85% or more based on a mass-balance determination [24]) of an administered dose.

Identifying High-Risk BCS Class IV Compounds

Within the BCS framework, Class IV compounds represent the highest-risk category for drug development. These molecules possess the dual challenges of low solubility and low permeability, leading to inherently poor and highly variable bioavailability [26] [24]. This makes them particularly problematic for formulation and for reliably predicting in vivo performance based on in vitro data.

Recent regulatory guidance, such as from the USFDA, specifies that for BCS Class IV molecule-containing immediate-release (IR) formulations, in vitro testing alone is not sufficient for waiving bioequivalence studies. Instead, more advanced techniques like Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling are recommended for risk assessment [26]. This highlights the heightened regulatory scrutiny and complexity associated with these compounds.

Table 2: Examples of High-Risk BCS Class IV Molecules and Associated Risks

| BCS Class IV Molecule | Reported Risk and Challenge |

|---|---|

| Edoxaban | Identified as high-risk for carcinogenic potential from nitrosamine impurities; transporters involved in absorption complicate risk assessment [26]. |

| Selumetinib | Clinical exposure risk assessment required due to high-risk categorization; permeability and transporter kinetics significantly impact exposure [26]. |

| Bosutinib | PBPK modeling used to evaluate impact of altered permeability and transporter kinetics on exposures [26]. |

| Furosemide | Clinical exposure risk assessment conducted due to high-risk categorization [26]. |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Transporter involvement in absorption adds complexity to predicting bioequivalence [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Working with BCS Class II and IV compounds requires specific reagents and techniques to overcome solubility limitations in experimental assays. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Solubility-Enhancement

| Reagent / Technique | Function and Application in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|

| Surfactants (e.g., SLS, Tween 80) | Reduce interfacial tension, increase wetting, and solubilize hydrophobic drugs in dissolution media [23]. |

| Complexing Agents (e.g., Cyclodextrins) | Form reversible inclusion complexes with drug molecules, increasing their apparent aqueous solubility [23]. |

| Hydrophilic Carriers (e.g., PVP, PEG) | Used in solid dispersions to create a hydrophilic matrix that improves drug dissolution rates [23]. |

| Lipidic/Greasy Substances (e.g., oils, waxes) | Used in lipid-based formulations to solubilize and improve the absorption of poorly water-soluble drugs [23]. |

| Buffers (across pH 1-6.8) | Used for solubility characterization and dissolution testing as per regulatory guidance across the physiologically relevant pH range [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Kinetic Assay Approach for Poorly Soluble Systems

The following workflow outlines a generalized kinetic assay, adapted from enzymology studies, that is mindful of the challenges posed by poorly soluble substrates [19] [27]. This is crucial for generating reliable data with BCS Class II and IV compounds.

Detailed Methodology

- Pre-experiment Solubility Check: Before any kinetic experiment, determine the maximum solubility of your substrate (the drug compound) in the chosen assay buffer across the relevant pH range. This is a critical first step to avoid experimental artifacts [27].

- Substrate Stock Preparation:

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the substrate in a suitable water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., DMSO, ethanol). The final concentration of the organic solvent in the assay must be kept low (typically <1-2%) to avoid denaturing proteins or enzymes and affecting the reaction [27].

- Control: Include a control in the assay that contains the same final concentration of the solvent but no substrate to account for any solvent effects.

- Running the Kinetic Assay:

- Initiate the reaction by adding the enzyme, membrane preparation, or other catalyst to the buffered reaction mixture containing the substrate.

- Ensure thorough mixing of comparable volume additions to minimize pipetting errors and ensure solution uniformity [27].

- Monitor the reaction in real-time using a suitable method (e.g., spectrophotometry, HPLC).

- Initial Rate (v₀) Determination:

- Collect data points at early time intervals where the reaction progress is linear.

- Define "time zero" carefully, accounting for the mixing time, to accurately determine the initial rate, which is the slope of the linear progress curve at this point [27].

- Data Fitting and Analysis:

- Plot the initial rate (v₀) against the substrate concentration ([S]).

- Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten model (or other appropriate models) to determine the apparent KM (Michaelis constant) and vmax (maximum reaction rate) [27].

- A high apparent KM can often be an indicator of poor substrate solubility limiting the reaction [27].

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Kinetic Assays

FAQ 1: My kinetic data shows a non-linear response at high substrate concentrations, and the calculated KM appears abnormally high. What could be the cause?

This is a classic symptom of substrate solubility limitations [27]. If the substrate is not fully soluble at the higher concentrations used in the assay, the effective concentration available for the reaction is lower than assumed. This leads to a plateau in the rate that is not due to enzyme saturation but to physical solubility, resulting in an inflated apparent KM value.

- Solution: Re-check the solubility of your substrate in the exact assay buffer. All substrate concentrations used in the kinetic experiment must be below the determined saturation point. Using solubility-enhancing agents (see Table 3) may be necessary, but their effects on the catalyst must be controlled for.

FAQ 2: My negative control (buffer only) shows unexpected background activity. How should I investigate this?

Buffers and other solution components can sometimes contribute to the observed reaction, especially in the presence of metal ions or other catalysts [27].

- Solution:

- Perform a comprehensive set of control experiments, including omitting the catalyst and/or the substrate.

- Investigate potential interactions between your buffer and metal ions. For example, Tris buffer can complex with certain metal ions and exhibit catalytic activity [27].

- Ensure the assay components are stable and not degrading to form reactive species.

FAQ 3: For a BCS Class IV compound, how can we bridge the gap between in vitro kinetic data and in vivo performance?

Due to the complex and variable absorption of BCS Class IV drugs, in vitro data alone is often insufficient. Regulatory agencies recommend the use of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling as an advanced tool for this purpose [26].

- Solution: Develop a PBPK model that incorporates the in vitro kinetic parameters (e.g., permeability, solubility) to simulate in vivo exposure. This model can be used to evaluate the impact of formulation changes and to define a "permeability safe space"—a range within which changes in permeability still ensure bioequivalence [26].

Risk Assessment Workflow for BCS Class IV Molecules

The following diagram outlines a modern, integrated risk assessment strategy for BCS Class IV molecules, as recommended by current regulatory science.

Core Concepts and Definitions

What are Hildebrand and Hansen Solubility Parameters? Solubility parameters are numerical values used to predict the solubility of materials based on the principle that "like dissolves like". The Hildebrand Solubility Parameter (δ) is a single value representing the square root of the cohesive energy density (CED), which is the energy required to separate molecules of a substance [28] [29]. It is defined as δ = √((ΔHv - RT)/Vm), where ΔHv is the heat of vaporization, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, and Vm is the molar volume [28] [30].

The Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) represent an extension of the Hildebrand parameter, dividing the total cohesive energy into three distinct intermolecular interaction components [31] [30]:

- δD: Dispersion forces (van der Waals interactions)

- δP: Polar interactions (dipole-dipole forces)

- δH: Hydrogen bonding interactions

The relationship between Hildebrand and Hansen parameters is expressed as δ² = δD² + δP² + δH² [30] [32].

Parameter Tables for Common Substances

Table 1: Hildebrand and Hansen Solubility Parameters for Common Solvents

| Substance | δ (Hildebrand) [MPa¹/²] | δD [MPa¹/²] | δP [MPa¹/²] | δH [MPa¹/²] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Pentane | 14.4 [28] | ~14.1* | ~0.0* | ~0.0* |

| n-Hexane | 14.9 [28] | 14.9 [33] | 0.0 [33] | 0.0 [33] |

| Diethyl Ether | 15.4 [28] | 14.5 [34] | 2.9 [34] | 4.6 [34] |

| Ethyl Acetate | 18.2 [28] | 15.8 [33] | 5.3 [33] | 7.2 [33] |

| Toluene | 18.3 [29] | 18.0 [33] | 1.4 [33] | 2.0 [33] |

| Chloroform | 18.7 [28] | 17.8 [33] | 3.1 [33] | 5.7 [33] |

| Acetone | 19.9 [28] | 15.5 [33] | 10.4 [33] | 7.0 [33] |

| 2-propanol | 23.8 [28] | 15.8 [33] | 6.1 [33] | 16.4 [33] |

| Ethanol | 26.5 [28] | 15.8 [33] | 8.8 [33] | 19.4 [33] |

Note: Values for n-Pentane are estimated based on similar hydrocarbons. Always consult primary sources for precise values in experimental work.

Table 2: Hildebrand Solubility Parameters for Common Polymers

| Polymer | δ (Hildebrand) [MPa¹/²] |

|---|---|

| PTFE | 6.2 [28] |

| Poly(ethylene) | 7.9 [28] |

| Poly(propylene) | 16.6 [28] |

| Poly(styrene) | ~18.6 [34] |

| PVC | 19.5 [28] |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | 19.0 [28] |

| Nylon 6,6 | 28 [28] |

Experimental Determination Methods

Determining HSP via Solubility Testing

Protocol for Experimental HSP Determination [35] [30] [32]:

Sample Preparation: Prepare 20-30 solvent systems with known HSP values that span the three-dimensional parameter space.

Solubility Testing:

- Add a fixed amount of your solute (typically 5-50 mg) to a series of vials containing different solvents.

- Agitate the mixtures for 24 hours at constant temperature.

- Centrifuge if necessary to separate dissolved and undissolved material.

- Determine solubility (yes/no) or measure the concentration dissolved at a specific threshold.

Data Analysis:

- Classify solvents as "good" (dissolves solute) or "poor" (does not dissolve solute).

- Use HSP software (such as HSPiP) or statistical methods to calculate the HSP sphere that best separates good from poor solvents.

- The center of this sphere represents the HSP of your solute.

Validation: Test additional solvents to validate the predicted HSP values.

Determining Solubility Parameters via Inverse Gas Chromatography (IGC)

Protocol for IGC Determination [30]:

Column Preparation: Pack a chromatography column with the solid sample of interest as the stationary phase.

Instrument Setup: Use an inert carrier gas (nitrogen or helium) and ensure the system is at constant temperature.

Solvent Probe Injection: Inject vapor phases of various organic solvents with known characteristics into the column.

Data Collection: Measure the specific retention volume (Vg) for each solvent probe.

Data Analysis: Use the relationship: χ₁₂∞ = ln(273.15·R·p₁⁰/(Vg·Mr₁)) - p₁⁰/(R·T)·(B₁₁-V₁) + ln(ρ₁/ρ₂) - (1-V₁/V₂) to calculate the Flory-Huggins parameter, which can be related to solubility parameters [30].

Parameter Calculation: Apply regression analysis to determine the HSP values that best fit the retention data.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why do my solubility predictions fail even when Hildebrand parameters match?

Issue: The single-parameter Hildebrand approach cannot account for specific polar and hydrogen-bonding interactions [34].

Solution: Use the three-parameter Hansen system instead. For example, n-Butanol and Nitroethane have identical Hildebrand parameters (23 MPa¹/²) but neither dissolves a typical epoxy. However, a 50:50 mixture is a good solvent because the combined HSP values create a favorable interaction profile [34].

FAQ 2: How can I dissolve a solute when no single good solvent is available?

Issue: Environmental or safety concerns may limit solvent options.

Solution: Use solvent blending. Two "poor" solvents with complementary HSP can often form a "good" solvent mixture. Calculate the HSP of blends using volumetric weighting: δblend = φ₁δ₁ + φ₂δ₂, where φ is the volume fraction [34].

FAQ 3: How do I handle solubility parameter determination for complex natural products like lignin?

Issue: Heterogeneous biomaterials with diverse functional groups challenge simple solubility predictions.

Solution: Use Functional Solubility Parameters (FSP) which bypass arbitrary solubility thresholds and create a solubility function represented by a polyhedron, whose center of mass is the solute FSP [32].

FAQ 4: What computational methods can predict solubility parameters?

Solution: Molecular dynamics simulations can calculate HSP using the formula: δ = √(ρ·(〈Evapor〉 - 〈Eliquid〉)/M), where ρ is density, E is potential energy, and M is molecular weight [36] [37]. Commercial software like Winmostar and Matlantis offer these capabilities [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Solubility Parameter Work

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HSPiP Software | Comprehensive package for calculating, analyzing, and predicting using HSP [35] [31] | Includes databases of 1200+ chemicals with experimental HSP and 10,000+ with estimated values [35] |

| Solvent Blending Kits | Creating custom solvent mixtures from primary solvents to target specific HSP space | Include solvents representing different regions of HSP space (dispersion-dominated, polar, hydrogen-bonding) [34] |

| Inverse Gas Chromatography | Experimental determination of HSP for solid materials [30] | Particularly valuable for pharmaceuticals and polymers; requires specialized equipment |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Computational prediction of HSP from molecular structure [36] [37] | Examples: Matlantis, Winmostar; useful when experimental data is scarce |

| HSP Determination Services | Outsourced experimental HSP measurement | Providers include Agfa Labs (Belgium) and VLCI (Netherlands) [35] |

Practical Application in Kinetic Assays

Strategies for Addressing Substrate Solubility Issues:

Solvent Selection Protocol:

- Calculate the HSP of your substrate using group contribution methods or experimental data.

- Identify solvents or solvent blends with similar HSP values.

- Consider environmental, safety, and compatibility factors with your assay system.

Solvent Blending for Aqueous Systems:

- For biological assays requiring aqueous conditions, use water-miscible co-solvents.

- Calculate the HSP of water (δD=15.5, δP=16.0, δH=42.3 [33]) and identify co-solvents that bridge the HSP gap between your substrate and aqueous buffer.

Validation Steps:

- Confirm that solvent choices don't interfere with enzyme activity or detection methods.

- Test solubility at assay temperature, as HSP can be temperature-dependent.

- Verify that substrates remain dissolved throughout the assay duration.

Practical Strategies and Tools for Enhancing Substrate Solubility

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Solvent-Related Issues in Kinetic Assays

Problem 1: Precipitate Formation Upon Adding Substrate to Assay Buffer

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cloudy solution or visible particles after adding substrate from DMSO stock [16]. | Kinetic solubility limit exceeded; substrate precipitates from aqueous buffer. | - Dilute the DMSO stock solution.- Introduce a compatible water-miscible co-solvent (e.g., ethanol, acetonitrile) into the assay buffer [38] [39].- Reduce substrate concentration, if experimentally feasible. |

Problem 2: Unreliable or Scattered Kinetic Data

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability between replicates; non-linear progress curves [27]. | - Inhomogeneous solution due to poor substrate solubility.- Preferential solvation altering local substrate concentration [39]. | - Ensure uniform mixing by matching volumes of substrate and catalyst solutions before combination [27].- Characterize solubility in the final assay buffer composition.- Use a standardized equilibration time before initiating the reaction. |

Problem 3: Low Catalytic Activity Suspected Due to Poor Substrate Availability

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lower-than-expected reaction velocity despite confirmed enzyme activity. | Apparent substrate concentration is lower than prepared concentration due to insolubility [27]. | - Determine the thermodynamic solubility of the substrate in the assay buffer [7].- Switch to a co-solvent that provides higher solubility for the specific substrate (see Table 2). |

HPLC Troubleshooting for Solvent-Related Problems

Problem: Abnormal Chromatography After Switching Solvent Systems

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Peak tailing or broadening [40]. | - Sample solvent stronger than mobile phase.- Column degradation from pH or solvent incompatibility. | - Prepare samples in a solvent weaker than or identical to the mobile phase [40].- Flush column with a strong solvent to remove contaminants [40]. |

| Retention time shifts [40]. | - Change in mobile phase composition due to co-solvent evaporation.- Pump malfunction causing inconsistent flow rate. | - Prepare mobile phase fresh and consistently [40].- Check pump for leaks and ensure proper degassing of solvents [40]. |

| Baseline noise or drift [40]. | - Contaminated solvents or mobile phase components.- Temperature fluctuations. | - Use fresh, high-purity HPLC-grade solvents [40].- Install a column oven to stabilize temperature [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between kinetic and thermodynamic solubility, and why does it matter for my assays?

A: Kinetic solubility refers to the concentration of a compound when it is rapidly dissolved from a pre-dissolved stock (usually in DMSO) into an aqueous buffer. This measurement is most relevant for high-throughput screening, where compounds are added from DMSO stocks and may not reach equilibrium, potentially leading to precipitation [7] [16]. In contrast, thermodynamic solubility measures the maximum concentration of a solid compound dissolved in a solvent under equilibrium conditions. It is more critical for later-stage development, such as formulation and predicting in vivo behavior [7]. Using the wrong type of solubility data can mislead your assay interpretation; kinetic solubility helps prevent false negatives in early screening, while thermodynamic solubility ensures your substrate is genuinely available at the reported concentration [7] [16].

Q2: My substrate is not soluble in pure water or pure organic solvent. What are my options?

A: Employing a mixed solvent system is a standard and effective approach. You can dissolve your substrate in a minimal volume of a "soluble solvent" (an organic solvent in which it is highly soluble, like acetone or methanol) and then add a miscible "insoluble solvent" (like water) dropwise until the solution becomes faintly cloudy. Finally, add a small amount of the soluble solvent back until the solution just clarifies. This method finely tunes the solvent environment to achieve solubility [38]. Common solvent pairs for this include methanol/water, ethanol/water, and acetone/water [38].

Q3: How do I choose the best organic co-solvent for my specific substrate?

A: The choice can be guided by the log-linear solubility model and the substrate's octanol-water partition coefficient (log P). A general rule is that the solubilizing power of a co-solvent increases for substrates with higher log P values [39]. You can predict solubility in a water-co-solvent mixture using the equation: log S_mix = log S_w + φ(S * log P + T), where S_mix is solubility in the mixture, S_w is water solubility, φ is the co-solvent volume fraction, and S and T are co-solvent-specific constants [39]. Experimentally, you should screen small volumes of candidate solvents for their ability to dissolve your substrate.

Q4: Can the buffer itself affect my substrate's solubility and the reaction kinetics?

A: Yes, significantly. Buffers are not always inert. They can participate in the reaction or interact with metal ions and substrates. For example, Tris buffer can interact with certain metal ions, and phosphate buffers can precipitate with introduced metal cations [27]. Always run control experiments to ensure your buffer is not contributing to the observed kinetics or affecting substrate solubility through unintended interactions [27].

Q5: What are the safety considerations when mixing organic solvents?

A: Always consult the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) for each solvent before mixing [41]. Be aware of potential chemical reactions; for instance, esters like ethyl acetate can slowly hydrolyze in aqueous solutions to form acids (e.g., acetic acid), which may require neutralization [41]. Generally, avoid mixing strong oxidizing agents with organic solvents, and be cautious of heat and light conditions that might accelerate undesirable reactions [41].

Quantitative Data & Experimental Protocols

Solubility Data and Co-solvent Selection

Table 1: Common Mixed Solvent Pairs for Crystallization and Solubilization [38]

| Solvent Pair | Soluble Solvent | Insoluble Solvent | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol / Water | Methanol | Water | Crystallization of polar organic compounds. |

| Ethanol / Water | Ethanol | Water | Safer alternative to methanol/water; commonly used in pharmaceutical processing. |

| Acetone / Water | Acetone | Water | Fast evaporation; good for many drug-like molecules. |

| Diethyl Ether / Petroleum Ether | Diethyl Ether | Petroleum Ether (or Hexanes) | Purification of non-polar compounds. |

| Ethyl Acetate / Hexanes | Ethyl Acetate | Hexanes | Standard for flash chromatography; fine-tuning polarity. |

Table 2: Impact of Compound Polarity (log P) on Solubility in Water-Co-solvent Mixtures (Representative Data) [39]

| Compound Polarity (log P) | Solubility in Water | Solubility Trend with Increasing Co-solvent | Example Co-solvent Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (e.g., 4.5) | Very Low | Sharp logarithmic increase | Solubility of a compound like Tioconazole increases dramatically with small additions of co-solvent [39]. |

| Medium (e.g., 0.5) | Moderate | Moderate increase | Solubility of a compound like Caffeine increases gradually with co-solvent fraction [39]. |

| Low (e.g., -2.5) | High | Can decrease | Solubility of a highly polar compound like Oxfenicine may decrease as co-solvent is added [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Kinetic Solubility via Nephelometry

This protocol determines the concentration at which a compound precipitates upon dilution from a DMSO stock into aqueous buffer.

- Stock Solution: Prepare a 10 mM stock of the substrate in DMSO.

- Dilution Series: Create a serial dilution of the stock solution into a physiologically relevant buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4). The final DMSO concentration should be kept constant (typically 0.1-1%).

- Incubation: Allow the plates to incubate at the assay temperature for a set period (e.g., 1-3 hours) with gentle shaking.

- Measurement: Measure the turbidity (nephelometry) or light scattering of each well. A sharp increase in signal indicates precipitation.

- Data Analysis: The kinetic solubility is reported as the highest concentration at which the compound remains in solution (below the precipitation threshold) [16].

Protocol 2: Mixed Solvent Crystallization for Substrate Purification

This procedure is used to purify a solid substrate by dissolving it in a minimal volume of a good solvent and carefully adding a poor, miscible solvent to induce crystallization [38].

- Dissolution: Place 100 mg of the impure solid in a test tube. Add the "soluble solvent" (e.g., methanol) dropwise while heating in a hot water bath or steam bath. Continue adding and heating until the solid just dissolves [38].

- Turbidity Point: Add the "insoluble solvent" (e.g., water) dropwise to the hot solution. After each addition, heat the mixture. Continue until the solution becomes persistently cloudy, indicating the onset of precipitation [38].

- Clarification: Add the "soluble solvent" dropwise again, with heating, until the cloudiness just disappears and the solution is clear [38].

- Crystallization: Set the solution aside to cool slowly to room temperature. Then, place it in an ice bath for 10-20 minutes to complete crystallization [38].

- Isolation: Collect the crystals by vacuum filtration and wash them with a small amount of cold "insoluble solvent" [38].

Workflow and Strategy Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Solvent Engineering

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Water-Miscible Co-solvents (Methanol, Ethanol, Acetone, Acetonitrile, DMSO) | To increase the solubility of non-polar organic substrates in aqueous assay buffers by modifying the overall polarity of the solvent mixture [38] [39]. | Adding 5-10% v/v acetonitrile to an aqueous buffer to dissolve a hydrophobic substrate for a kinetic assay. |

| Water-Immiscible Solvents (Diethyl Ether, Ethyl Acetate, Hexanes) | Used in purification (extraction, crystallization) to separate compounds based on partitioning between organic and aqueous phases [38]. | Extracting a reaction product from an aqueous mixture into ethyl acetate. |

| Buffers (HEPES, Tris, Phosphate) | To maintain a constant pH in the assay environment, which is critical for enzyme activity and substrate stability [27]. | Using 50 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.5 for a kinase assay [19]. |

| Log P/Log D Calculator (Software or empirically determined) | A key physicochemical descriptor that predicts a compound's hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity and guides co-solvent selection [16] [39]. | Using a compound's calculated log P to predict its solubility trend in ethanol/water mixtures. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Salt Formation

Problem: Low Aqueous Solubility in GI Tract

- Potential Cause: Precipitation in the stomach due to pH change or common ion effect.

- Solution:

- Conduct pre-formulation studies to simulate the pH gradient of the GI tract.

- Consider alternative salt forms less susceptible to the common ion effect (e.g., avoiding hydrochloride salts in high chloride ion environments) [42].

Problem: Poor Physical Stability/Hygroscopicity

- Potential Cause: The selected salt form has a high affinity for moisture.

- Solution:

- Evaluate the salt's hygroscopicity under controlled relative humidity conditions early in screening.

- Opt for salt forms with lower deliquescence points [42].

Problem: Inadequate Dissolution Rate

- Potential Cause: The salt reverts to its less soluble free acid or base form upon introduction to the dissolution medium.

- Solution:

- Incorporate polymers that inhibit crystallization and stabilize the supersaturated state generated by the dissolving salt [42].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Co-crystal Development

Problem: Lack of Co-crystal Formation

- Potential Cause: Insufficient thermodynamic driving force or inappropriate co-former selection.

- Solution:

Problem: Dissolution Performance Does Not Meet Expectations

- Potential Cause: The co-crystal exhibits the "spring and parachute" effect but lacks a crystallization inhibitor.

- Solution:

Problem: Scale-up Challenges

- Potential Cause: Solution-based co-crystal production methods are difficult to reproduce on a larger scale.

- Solution:

- Prioritize solvent-free manufacturing technologies like neat grinding or hot melt extrusion for better scalability and consistency [43].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary regulatory consideration for co-crystals? Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA classify pharmaceutical co-crystals as novel solid forms of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), not as new chemical entities. This means the co-crystal is regulated based on the safety profile of the parent API, which can streamline the development pathway [43].

FAQ 2: When should I choose a salt form over a co-crystal? The choice is primarily determined by the ionizability of the API:

- Salts: Are applicable for ionizable APIs (acids or bases). Salt formation modifies the API's pH to enhance solubility and dissolution [42].

- Co-crystals: Are ideal for non-ionizable APIs. They modify solid-state properties (e.g., lower lattice energy) through non-covalent interactions with a co-former without changing the chemical identity of the API [42] [43].

FAQ 3: How can I prevent the precipitation of a supersaturated solution generated from a salt or co-crystal? This is a common challenge known as the "spring and parachute" effect. The solution is to formulate with polymeric precipitation inhibitors (e.g., povidone, hypromellose) that act as a 'parachute'. These polymers stabilize the metastable supersaturated state, prolonging the high concentration and improving bioavailability [44] [42].

FAQ 4: What are the key analytical techniques for characterizing co-crystals? A multi-technique approach is essential to confirm co-crystal formation and characterize its properties. Key techniques include:

- Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD): To identify a unique crystalline pattern distinct from the parent components.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): To observe changes in melting point and thermal events.

- Spectroscopic Methods: such as Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy, to probe molecular interactions like hydrogen bonding [43].

The following table summarizes key solubility enhancement techniques and their characteristics, aiding in the selection of an appropriate strategy for kinetic assays [42].

Table 1: Comparison of Chemical Modification Techniques for Solubility Enhancement

| Technique | Key Mechanism | Best Suited For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salt Formation | Alters pH via ionization to improve aqueous solubility [42]. | Ionizable APIs (acids or bases) [42]. | Susceptible to precipitation in GI tract due to pH change or common ion effect [42]. |

| Co-crystals | Reduces lattice energy via non-covalent bonds with a co-former; improves apparent solubility without chemical change [42] [43]. | Non-ionizable APIs with strong hydrogen bond donors/acceptors [42] [43]. | More stable than ASDs but may still require polymers to maintain supersaturation in vivo [42]. |

| Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs) | Creates a high-energy, amorphous form with no crystal lattice, maximizing dissolution [44] [42]. | APIs with high lattice energy; can address high lipophilicity with hydrophobic carriers [42]. | Thermodynamically unstable; requires polymers to inhibit recrystallization in solid state and during dissolution ("spring and parachute") [44] [42]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of Co-crystals via Solvent-Free Grinding

This method is efficient, scalable, and avoids solvent contamination [43].

- Weighing: Accurately weigh the API and the selected co-former in the desired stoichiometric ratio (typically 1:1 or 1:2) into a mortar or a ball mill jar.

- Grinding: For neat grinding, grind the mixture manually with a pestle for 30-60 minutes. Alternatively, use a ball mill for mechanical grinding. Monitor the reaction by observing changes in the powder's consistency and color.

- Liquid-Assisted Grinding (Optional): To accelerate the process or facilitate specific polymorph formation, add a minimal amount (a few drops) of a non-reactive solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, ethanol) during grinding.

- Characterization: Analyze the resulting solid using PXRD and DSC to confirm the formation of a new crystalline phase distinct from the starting materials [43].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the "Spring and Parachute" Effect

This protocol assesses the ability of a formulation to generate and maintain supersaturation, which is critical for kinetic assay performance [44] [42].

Supersaturation Generation ("Spring"):

- Use a USP dissolution apparatus (e.g., Apparatus II) with a suitable dissolution medium (e.g., pH 6.8 phosphate buffer) at 37°C.

- Introduce the test formulation (e.g., salt, co-crystal, or ASD) into the vessel. The dissolution of the high-energy form should rapidly create a supersaturated solution.

Supersaturation Maintenance ("Parachute"):

- In parallel experiments, include a dissolved polymer (e.g., povidone, hypromellose) in the dissolution medium before adding the formulation.

- Withdraw samples at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes), filter, and analyze the drug concentration using HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Data Analysis: Plot concentration versus time. Compare the area under the curve (AUC) for the concentration profiles with and without the polymer. A higher and more sustained AUC in the presence of the polymer confirms an effective "parachute" effect [44] [42].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Solubility Enhancement Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Inhibitors (e.g., Povidone (PVP), Hypromellose (HPMC)) | Acts as a "parachute" to maintain drug supersaturation by inhibiting nucleation and crystal growth [44] [42]. | Added to dissolution media to stabilize supersaturated solutions generated by salts or co-crystals. |

| Co-formers (e.g., Nicotinamide, Succinic Acid) | Molecules that form co-crystals with an API via hydrogen bonds or other non-covalent interactions, modifying its solubility [43]. | Screened in grinding or solvent evaporation experiments to form new solid phases with the target API. |

| Solvents for Screening (e.g., Dichloromethane, Methanol, Acetonitrile) | Used in solvent-based methods (spray drying, solvent evaporation) to dissolve API and carrier for homogeneous mixture formation [44] [43]. | Preparing solutions for spray-drying amorphous solid dispersions or for slurry co-crystallization. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: During the production of Nanosized Amorphous Solid Dispersions (NASDs), my formulation is showing signs of recrystallization. What could be the cause and how can I prevent it?

- A: Recrystallization is a common challenge that can occur during storage or dissolution if the solid dispersion is not properly stabilized [45]. The primary causes and solutions are:

- Cause: The drug and polymer have low miscibility, leading to phase separation [45].

- Solution: Select a polymer that is highly miscible with the API. Thermal analysis (e.g., determining the glass transition temperature, Tg) can help assess drug-polymer solubility and miscibility. Using a polymer with a high Tg can increase the mechanical stiffness of the dispersion and reduce molecular mobility, thereby inhibiting crystallization [45].

- Cause: The formulation lacks a stabilizing agent to maintain a supersaturated state [45].

- Solution: Move to a third-generation solid dispersion by incorporating a surfactant or a combination of amorphous polymers and surfactants [45]. Additives like Pluronic or sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) can improve stability and inhibit precipitation [45].

Q2: My amorphous solid dispersion has acceptable solubility but the permeability of my drug remains low. Are there formulations that can address both issues simultaneously?

- A: Yes. Research has shown that certain NASD formulations can enhance both apparent solubility and effective membrane permeability [46]. During the dissolution of some ASDs, drug-rich nanoparticles can be generated through liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) [46]. These self-generated nanoparticles can improve oral absorption. However, LLPS is hard to control consistently. A more reliable approach is to pre-fabricate NASDs (with sizes between 40-200 nm) embedded within a polyol matrix, which can rapidly disperse into a nanoparticle suspension in aqueous media and has demonstrated enhanced permeability in assays like PAMPA [46].

Q3: I am working with a very high drug load. Can NASD technology still be effective?

- A: Yes, advanced manufacturing processes like twin-screw extrusion (TSE) have been used to produce NASDs with drug loadings as high as 80% w/w while maintaining high encapsulation efficiency [46]. The TSE platform is noted for its high drug-loading capacity and scalability [46].

Q4: What are the key advantages of moving from a batch process to a continuous manufacturing (CM) process for drug nanoparticle production?

- A: Continuous Manufacturing addresses several limitations of traditional batch processes [47]:

- Improved Control & Quality: Enables better particle size control and reduces intermediate processing steps.

- Efficiency & Scalability: Offers a streamlined, continuous scheme that reduces the manufacturing footprint and cost. Scalability is achieved through parallelization rather than traditional scale-up.

- Process Monitoring: Supports real-time monitoring of Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Key Quality Attributes (KQAs) for more consistent output.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Continuous Manufacturing of Nanosized Amorphous Solid Dispersions via Twin-Screw Extrusion

This protocol outlines the production of high drug-loading NASDs using a continuous TSE process, benchmarking against conventional ASDs [46].

Objective: To continuously produce NASD formulations with enhanced in vitro solubility and permeability.

Materials:

- API: Celecoxib (BCS Class II model drug) or similar poorly soluble compound.

- Polymers: Polyvinylpyrrolidone-co-vinyl acetate (PVPVA) or Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate (HPMCAS).

- Equipment: Co-rotating Twin-Screw Extruder.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Pre-blend the API and the polymer carrier at the desired mass ratio (e.g., for high drug loading up to 80% w/w).

- Extrusion: Feed the powder blend into the twin-screw extruder. The process parameters (e.g., temperature profile along barrels, screw speed, feed rate) are critical and must be optimized for the specific API-polymer system.

- Collection: The extrudate is collected, cooled, and milled into a fine powder if necessary.

- Dispersion: The final NASD powder is designed to be rapidly dispersed in aqueous media to form a nanoparticle suspension (40-200 nm).

Protocol 2: Preparation of Third-Generation Solid Dispersions using Surfactants

This protocol details the creation of a more stable, surfactant-containing solid dispersion to prevent recrystallization and enhance dissolution [45].

Objective: To formulate a stable amorphous solid dispersion using a polymer and surfactant combination.

Materials:

- API: A poorly water-soluble drug.

- Polymer: A suitable amorphous polymer (e.g., PVP).

- Surfactant: Pluronic F68, Lutrol, or Tween 80.

- Method: Hot Melt Extrusion (HME) or Solvent Evaporation.

Methodology (using Solvent Evaporation):

- Dissolution: Dissolve the drug, polymer, and surfactant in a common volatile organic solvent (e.g., methanol, dichloromethane).

- Homogenization: Agitate the solution to ensure a homogeneous mixture.

- Evaporation: Remove the solvent rapidly under reduced pressure (e.g., using a rotary evaporator) to form a solid matrix.

- Drying: Further dry the solid dispersion in a vacuum oven to remove any residual solvent.

- Milling: Mill the solid mass into a fine powder and sieve to a uniform particle size.

Table 1: Comparison of Solid Dispersion Generations

| Generation | Key Components | Mechanism | Key Advantages | Common Carriers & Additives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First [45] | Crystalline carriers | Eutectic mixtures; reduced particle size | Improved dissolution over API | Urea, Mannitol |

| Second [45] | Amorphous polymers | Molecular-level dispersion; glass solution | Higher solubility & dissolution rate | PVP, PEG |

| Third [45] | Amorphous polymers + Surfactants | Prevents recrystallization; maintains supersaturation | Enhanced stability and bioavailability | PVP + Pluronic, Inulin Lauryl Carbamate |

| Fourth [45] | Water-insoluble/swellable polymers | Controlled drug release via diffusion/erosion | Prolonged therapeutic effect; reduced dosing | Eudragit RS, Ethyl cellulose |

Table 2: Critical Parameters for Nanoparticle Manufacturing

| Process Type | Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) | Key Quality Attributes (KQAs) |

|---|---|---|

| Batch Bottom-Up [47] | Antisolvent addition rate, Stirring speed/shear, Temperature, Solvent/antisolvent ratio | Particle size distribution, Zeta potential, Crystalline form, Stability |

| Continuous Manufacturing (e.g., TSE) [46] [47] | Temperature profile, Screw speed/configuration, Feed rate, Screw speed | Drug loading & encapsulation efficiency, Nanoparticle size, In vitro solubility & permeability, Physical stability (Tg) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for ASDs and Nanonization

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| PVPVA (Polyvinylpyrrolidone-co-vinyl acetate) [46] | A commonly used hydrophilic polymer carrier in ASDs/NASDs to inhibit crystallization and enhance solubility. |

| HPMCAS (Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate) [46] | A polymer used in ASDs; it is pH-dependent and can prevent precipitation in the intestine. |

| Pluronic F68 (Poloxamer 188) [45] | A surfactant used in third-generation SDs to improve wettability, inhibit crystallization, and enhance stability. |

| Eudragit RS/RL [45] | Water-insoluble polymers used in fourth-generation SDs for sustained or controlled drug release. |

| Soluplus [45] | A polymeric solubilizer specifically designed for the preparation of solid solutions via HME. |

| Lauroyl polyoxyl-32 glycerides [45] | A surfactant used to improve dissolution and achieve high polymorphism purity in SDs. |

Workflow Visualization

Formulation Strategy for Solubility Enhancement

Solid Dispersion Generations and Mechanisms

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary mechanisms by which solubilizing agents enhance substrate solubility for kinetic assays?

Solubilizing agents employ different fundamental mechanisms to increase the aqueous solubility of hydrophobic substrates, which is critical for accurate kinetic measurements.

- Cyclodextrins form dynamic inclusion complexes by encapsulating hydrophobic molecules within their internal hydrophobic cavity, effectively shielding them from the aqueous environment. The driving forces for this complex formation are primarily van der Waals interactions and the hydrophobic effect [48] [49].

- Surfactants operate by micellization. When their concentration exceeds the critical micelle concentration (CMC), surfactants assemble into micelles. These structures have a hydrophobic core that can solubilize lipophilic compounds, effectively bringing them into the aqueous solution [50] [51].

- Liposomes are phospholipid vesicles that can encapsulate hydrophobic compounds within their lipid bilayers and hydrophilic compounds within their aqueous interior [52] [53]. A more advanced strategy, "drug-in-cyclodextrin-in-liposome" (DCL), first complexes the drug with cyclodextrin and then encapsulates this complex within the liposome's aqueous core, combining the benefits of both systems for superior stability and release control [53].

FAQ 2: How does pH influence the performance of solubilizing agents, and how can I troubleshoot pH-related instability?

pH can significantly impact the physical stability of your solubilized system and the structure of your solubilizing agents, leading to inconsistent kinetic data.

- Observed Problem: Precipitation of substrate or changes in micelle/vesicle structure upon buffer change.

- Root Cause: The interfacial and emulsifying properties of peptides and many surfactants are pH-dependent. For instance, certain protein hydrolysates form stiffer, more elastic interfaces at pH 7 compared to pH 4, leading to better emulsifying activity at neutral pH [51]. Furthermore, the degradation of some drugs is accelerated in acidic or basic conditions.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Determine Stability Profile: Conduct pre-assay stability tests of your substrate with the solubilizing agent across the pH range you plan to use.

- Control pH: Use a buffering system that maintains a constant pH suitable for both your enzyme and your solubilized substrate. For example, a tryptic hydrolysate was shown to have better interfacial adsorption at pH 4 [51].

- Consider the Formulation: If your assay requires an acidic pH, select surfactants or cyclodextrins known to be stable and effective in that specific range.

FAQ 3: My kinetic data shows unexpected lag phases or non-linear progress curves. Could this be related to my solubilizing agent?

Yes, the choice and concentration of solubilizing agents can directly interfere with the enzymatic reaction, leading to aberrant kinetic curves.

- Observed Problem: A lag phase in the reaction progress curve or a lower-than-expected initial velocity (V₀).

- Root Cause: The solubilizing agent may be interacting with the enzyme instead of just the substrate. For example, some surfactants can denature proteins, while cyclodextrins can extract essential membrane components like cholesterol from enzymes, potentially altering their activity [48]. Furthermore, if the agent forms very stable complexes with the substrate, the rate of substrate release (dissociation) might become the rate-limiting step.

- Troubleshooting Steps: