Solid-State vs. Fluid Phase Synthesis: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of solid-state and fluid phase synthesis methodologies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Solid-State vs. Fluid Phase Synthesis: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of solid-state and fluid phase synthesis methodologies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both techniques, delves into their specific methodological workflows and applications in peptide and material synthesis, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common challenges, and presents a rigorous comparative analysis to guide method selection. The scope extends from core chemical concepts to advanced, scalable manufacturing processes, empowering readers to make informed, strategic decisions in therapeutic development and biomedical research.

Core Principles: Understanding Solid-State and Fluid Phase Synthesis

The chemical synthesis of peptides is a foundational process in modern pharmaceutical research and biotechnology, enabling the production of specific amino acid sequences for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Two primary methodologies have emerged for this purpose: Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) and Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS). The development of SPPS in the 1960s by R. Bruce Merrifield, for which he received the 1984 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, represented a revolutionary departure from traditional solution-phase methods. This heterogeneous approach, where the peptide chain is assembled on an insoluble polymeric support, fundamentally transformed the field by offering a more efficient and automatable pathway to obtain synthetic peptides [1] [2] [3].

This guide provides an objective comparison between solid-phase and liquid-phase peptide synthesis, focusing on their performance, applications, and practical implementation. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current methodologies to inform strategic decisions in peptide-based project planning.

Principles of Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis

The core concept of SPPS is to covalently anchor the growing peptide chain to a solid, insoluble polymer support (or resin). This simple yet powerful idea allows all reactions to occur at the resin-solution interface. The process begins with the C-terminal amino acid attached to the resin and proceeds through a repeating cycle of deprotection, coupling, and washing steps to add subsequent amino acids from the C to N terminus [4] [5].

A critical aspect of SPPS is the use of protecting groups. The N-terminal protecting group (temporary) is removed in each cycle to allow for the next coupling, while side-chain protecting groups (permanent) remain intact until the final cleavage. This strategy prevents unwanted side reactions and ensures the correct sequence assembly. After the full sequence is assembled, the completed peptide is cleaved from the resin, and all remaining protecting groups are removed simultaneously [4] [3].

The two dominant protecting group strategies in modern SPPS are:

- Fmoc/tBu Strategy: Uses base-labile 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) for Nα-protection and acid-labile tert-butyl (tBu) groups for side-chain protection. This orthogonal scheme is widely adopted due to its milder cleavage conditions, typically using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), which avoids highly hazardous reagents like HF [4] [5].

- Boc/Bzl Strategy: Uses acid-labile tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) for Nα-protection and benzyl (Bzl)-based groups for side-chain protection. This method requires graduated acidolysis, with TFA for repetitive deprotections and strong acids like anhydrous HF for final cleavage [4] [5].

Table 1: Key Components of a Modern SPPS System

| Component | Function | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Support | Insoluble polymer matrix providing a stable platform for synthesis | Polystyrene resin, Polyamide resin [5] [1] |

| Linker | Spacer molecule that determines the C-terminal functionality of the peptide after cleavage | Wang resin (for acid), PAM resin (for amide) [4] [1] |

| Nα-Protecting Group | Temporary protecting group removed before each coupling cycle | Fmoc (base-labile), Boc (acid-labile) [4] [5] |

| Side-Chain Protecting Groups | Permanent protecting groups removed during final cleavage | tBu, Trt (for Fmoc); Bzl (for Boc) [4] |

| Coupling Reagents | Activate the carboxyl group for efficient peptide bond formation | DCC, DIC, PyBOP, HBTU [4] [5] |

| Cleavage Reagent | Severs the peptide from the resin and removes side-chain protecting groups | Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA, for Fmoc), Anhydrous HF (for Boc) [4] |

Solid-Phase vs. Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Comparative Analysis

While SPPS has become the industry standard for most research and small-scale production applications, LPPS remains relevant for specific use cases. The following comparison outlines the core operational, performance, and applicability differences between the two methodologies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of SPPS vs. LPPS

| Parameter | Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) | Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS) |

|---|---|---|

| Process Fundamental | Heterogeneous synthesis on a solid support [5] | Homogeneous synthesis in solution [6] [7] |

| Automation Potential | High; robotic synthesizers are routine [4] [1] | Low to moderate; requires more manual intervention [6] |

| Purification Workflow | Simple filtration and washing between steps; no intermediate isolation [4] [5] | Complex; requires isolation and purification after each step [6] [7] |

| Throughput & Speed | High throughput; peptides of 20 residues in hours [1] | Slower due to intermittent purification [7] |

| Yield for Shorter Peptides | Generally high yields [6] | Varies; can be lower due to multi-step isolation [7] |

| Yield for Longer/Complex Peptides | Can decrease due to cumulative inefficiencies and aggregation [4] | Can be more favorable for certain complex sequences [6] |

| Operational Scale | Ideal for small to medium-scale production [6] | Often better suited for large-scale industrial production [6] [5] |

| Key Advantage | Operational simplicity, automation, speed | No risk of support-bound constraints or residue contamination [7] |

| Primary Limitation | Risk of support-derived side reactions and incomplete cleavage [7] | Cumbersome purification and low efficiency for standard sequences [6] [7] |

Experimental Protocol for Fmoc-Based SPPS

The following detailed protocol for standard Fmoc-SPPS is adapted from common laboratory practices and vendor instructions for automated synthesizers [4] [8]. This methodology is the most prevalent in contemporary research settings.

Resin Preparation and First Amino Acid Loading

- Swelling: Place the chosen resin (e.g., Wang resin for a C-terminal carboxylic acid) in the reaction vessel. Add a sufficient volume of an appropriate solvent (e.g., DMF or DCM) and allow it to swell for 15-30 minutes to maximize accessibility of the linker sites.

- Initial Coupling: After draining the swelling solvent, add the Fmoc-protected C-terminal amino acid (typically 3-5 molar equivalents) along with a coupling reagent like DIC (3-5 eq) and an additive like HOBt (3-5 eq) in DMF.

- Reaction Monitoring: Allow the coupling to proceed for 30-60 minutes with agitation. Monitor the reaction using a qualitative test (e.g., Kaiser ninhydrin test) to confirm complete coupling. If necessary, perform a second coupling to ensure full loading.

- Washing: Upon completion, drain the reaction solution and wash the resin thoroughly with DMF (3-5 times).

Repetitive Synthesis Cycle

The following cycle is repeated for each additional amino acid in the sequence, from the C-terminus to the N-terminus.

Fmoc Deprotection:

- Drain the solvent from the vessel.

- Treat the resin with a 20-30% solution of piperidine in DMF (v/v). Perform two treatments, typically for 3-5 minutes and 10-15 minutes, respectively.

- Drain the deprotection solution and wash the resin extensively with DMF (5-7 times) to remove all piperidine and the cleaved Fmoc byproduct.

Coupling Reaction:

- Prepare a solution of the next Fmoc-protected amino acid (4-5 molar equivalents relative to the initial resin loading) and the coupling reagents (e.g., HBTU/HOBt or DIC, 4-5 eq each) in a minimal volume of DMF.

- Add this activation mixture to the resin and agitate for 30-60 minutes.

- Monitor the reaction using the Kaiser ninhydrin test. If the test indicates incomplete coupling (>0.5%), perform a second coupling with fresh reagents.

- Drain the coupling solution and wash the resin with DMF (3 times).

Final Cleavage and Global Deprotection

- Final Deprotection: After incorporating the final N-terminal amino acid, perform a final Fmoc deprotection step as described above.

- Resin Washing and Drying: Wash the resin sequentially with DMF, DCM, and methanol. Allow the resin to dry under vacuum or a gentle nitrogen stream.

- Cleavage Cocktail Preparation: Prepare a cleavage cocktail containing Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) ~95% with appropriate scavengers (e.g., 2.5% water, 2.5% triisopropylsilane) to cap reactive cations during deprotection.

- Peptide Cleavage: Add the cold cleavage cocktail to the dried resin (typically 10 mL per gram of resin) and agitate at room temperature for 2-4 hours.

- Isolation: Filter the mixture to separate the cleaved peptide solution from the spent resin. Precipitate the crude peptide by adding the TFA solution into cold diethyl ether.

- Purification: Centrifuge to pellet the crude peptide, redissolve in a suitable solvent (e.g., water/acetonitrile), and purify by preparative reversed-phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). The final product should be characterized by analytical HPLC and Mass Spectrometry (MS).

The following workflow diagram visualizes the core cyclic process of SPPS.

SPPS Repetitive Synthesis Cycle and Final Cleavage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Resins for SPPS

Successful execution of SPPS relies on a carefully selected set of reagents and materials. The following table details the core components of a modern SPPS toolkit, particularly for the Fmoc/tBu strategy.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Fmoc-SPPS

| Item | Function/Description | Key Consideration for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Wang Resin | A hydroxymethylphenoxy-based support for producing peptides with a free C-terminal carboxylic acid [4] [1]. | Load the first Fmoc-amino acid via esterification. Cleavage with TFA yields the acid. |

| Rink Amide Resin | An aminomethyl-based support for producing C-terminal peptide amides [4]. | Essential for mimicking naturally occurring peptide amides and improving metabolic stability. |

| Fmoc-Protected Amino Acids | Building blocks with the Fmoc group protecting the α-amino group. Side chains are protected with acid-labile groups (e.g., tBu, Boc, Trt) [4] [5]. | Use high-purity (>99%) grades. The choice of side-chain protection is critical to minimize side reactions. |

| HBTU / HATU | Uranium-based coupling reagents that rapidly activate the carboxyl group for amide bond formation [4] [8]. | HATU generally offers faster coupling and reduces racemization but is more expensive than HBTU. |

| DIC / DIPCDI | Carbodiimide coupling reagents used with additives like HOBt or Oxyma to prevent racemization and facilitate coupling [4] [8]. | A cost-effective and efficient coupling system. The byproduct (diisopropylurea) is soluble in DMF. |

| HOBt / Oxyma Pure | Additives that suppress racemization during activation and act as catalysts for the coupling reaction [8]. | Oxyma is now often preferred over HOBt as it is non-explosive and offers excellent performance. |

| Piperidine Solution | A base solution (20-30% in DMF) used for the repetitive removal of the Fmoc protecting group [4]. | Standard for Fmoc deprotection. Must be thoroughly washed out after each cycle to prevent base-catalyzed side reactions. |

| TFA Cleavage Cocktail | Strong acid mixture (~95% TFA) with scavengers to cleave the peptide from the resin and remove side-chain protecting groups [4]. | Scavengers (e.g., Water, TIS, EDT) are vital for trapping reactive cations and protecting susceptible residues like Cys, Trp, and Tyr. |

Discussion and Strategic Application

The choice between SPPS and LPPS is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with project goals. The data indicates a clear dominance of SPPS, particularly the Fmoc/tBu strategy, in research and early-stage pharmaceutical development due to its automation, speed, and efficiency for most sequences [4] [5]. This makes it the undisputed method for rapid library generation, lead optimization, and producing peptides for biological screening.

However, LPPS remains a critical tool for specific niches. Its value is most apparent in the large-scale industrial manufacturing of well-defined peptides, where the drawbacks of intermittent purification are offset by the economies of scale and the avoidance of solid-support limitations [6] [5]. Furthermore, LPPS may be the only viable option for synthesizing extremely long or complex peptides that are prone to aggregation on a solid support or require specific solution-folding intermediates [6] [7].

For the modern researcher, the decision flowchart is often straightforward: SPPS is the default starting point for most novel peptide synthesis projects. LPPS is considered when scaling up a proven SPPS-derived sequence or when confronting a peptide that has proven refractory to solid-phase methods. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of both methodologies ensures that scientists and drug developers can select the most efficient and effective path to obtain their target molecules.

The field of peptide synthesis has evolved significantly, characterized by three major methodological waves. Classical solution peptide synthesis (CSPS) represented the first wave, followed by the revolutionary introduction of solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) by Merrifield in the 1960s [9] [10]. In recent years, liquid-phase peptide synthesis (LPPS) has emerged as the "third wave," combining advantages of both previous methods by performing peptide elongation in solution while anchoring the growing chain to a soluble tag [9]. This innovative approach addresses key limitations of SPPS, particularly for synthesizing longer or more complex peptides, while aligning with green chemistry principles by potentially reducing excess reagent consumption and solvent waste [9] [11].

Within the broader thesis comparing solid-state versus fluid phase synthesis research, LPPS represents a sophisticated advancement in solution-phase methodology. While solid-state synthesis often benefits from simplified purification through heterogeneous reactions, LPPS achieves similar practical advantages through intelligent molecular design of soluble tags that enable both excellent solvation during reactions and facile precipitation for purification [9] [11]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of LPPS against established methods, examines the experimental data supporting its efficacy, and details the protocols and reagents essential for its implementation.

Core Methodology Comparison: SPPS vs. LPPS

The fundamental distinction between solid-phase and liquid-phase peptide synthesis lies in the reaction environment and purification mechanisms. SPPS employs a heterogeneous system where the growing peptide chain is covalently attached to an insoluble solid support, typically polystyrene beads [6] [10]. This allows for simple filtration-based purification but suffers from diffusion limitations and reduced coupling efficiency due to the heterogeneous nature [11]. In contrast, LPPS utilizes a homogeneous solution system where the peptide is attached to a soluble polymer tag, enabling near-stoichiometric coupling reactions in a true solution environment while maintaining straightforward purification through the tag's precipitation properties [9] [11].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Peptide Synthesis Methods

| Characteristic | Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) | Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS) |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Environment | Heterogeneous (solid support) | Homogeneous (solution) |

| Purification Mechanism | Filtration and washing of solid support | Precipitation, filtration, or phase separation |

| Typical Scale | Small to medium peptides [6] | Larger, more complex peptides [6] |

| Automation Potential | High, widely automated [6] | Less automated, more manual intervention [6] |

| Reagent Consumption | Typically requires excess reagents (3-4 equivalents) [11] | Near-stoichiometric reactions possible [9] |

| Solvent Consumption | High due to repeated washing cycles [11] | Potentially reduced through optimized processes [9] |

| Coupling Efficiency | Can be retarded due to heterogeneity [11] | Enhanced by high solubility and concentration [11] |

Table 2: Practical Implementation Comparison for CDMO Selection

| Consideration | Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) | Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS) |

|---|---|---|

| Batch Size | Ideal for smaller batches [6] | Better suited for large-scale production [6] |

| Sequence Complexity | Optimal for small- to medium-sized peptides [6] | Superior for larger, more complex peptides [6] |

| Purification Complexity | Straightforward filtration [6] | More intricate purification processes [6] |

| Cost Structure | Cost-effective for smaller peptides [6] | Potentially more cost-effective for large, complex peptides despite higher initial costs [6] |

| Regulatory History | Extensive track record | Emerging approach with growing acceptance |

Soluble Tag Technologies in LPPS

The cornerstone of modern LPPS is the development of specialized soluble tags that confer unique physicochemical properties to the growing peptide chain. These tags enable two seemingly contradictory functions: excellent solubility during coupling reactions to ensure high reactivity, and facile precipitation for purification between steps [9] [11]. Various tag systems have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications.

The most prominent tag categories include polydisperse polyethylene glycol (PEG), fluorous tags, ionic liquids (ILs), and more recently developed silylated tags (STags) [9]. PEG-based tags enhance aqueous solubility but may present challenges in precise molecular weight control. Fluorous tags enable unique purification through fluorous-organic phase separation. Ionic liquid tags offer tunable solubility properties but may introduce complexity in tag removal. Silylated tags represent a particularly innovative approach, with tags like B2-STag and B6-STag demonstrating exceptional solubility in environmentally friendly solvents like cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) [11].

Table 3: Comparison of Soluble Tag Systems in LPPS

| Tag Type | Key Features | Solvent Compatibility | Purification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polydisperse, well-established | Aqueous and polar organic solvents | Precipitation, filtration |

| Fluorous Tags | Highly fluorinated compounds | Fluorous-organic solvent systems | Liquid-liquid extraction |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Tunable properties, low volatility | Various organic solvents | Precipitation, phase separation |

| Silylated Tags (STags) | Low viscosity, high hydrophobicity | CPME, CPME/DMF mixtures [11] | Precipitation, phase separation |

| Membrane-Enhanced Peptide Synthesis (MEPS) | Combined with membrane separation | Various solvent systems | Membrane filtration |

Experimental data demonstrates the remarkable solubility enhancement provided by advanced tag systems. For instance, STagged peptides show exceptional solubility in CPME, with B2-STagged peptides dissolving at over 100 mM concentrations, and B6-STagged peptides achieving even higher solubility up to 549 mM in pure CPME [11]. This high solubility enables reactions at elevated concentrations, significantly improving coupling kinetics, especially for sterically hindered amino acids.

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Solubility Enhancement Data

Quantitative solubility measurements provide compelling evidence for the effectiveness of soluble tags in LPPS. Using chemiluminescent nitrogen detection (CLND), researchers have systematically compared the solubility of tagged versus untagged peptides across various solvent systems [11].

Table 4: Solubility Measurements of Tagged Peptides in Different Solvents

| Peptide | Solubility in CPME (mM) | Solubility in CPME/DMF (7:3) (mM) | Solubility in DMF (mM) | Solubility in THF (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-FLG-O(TagA) | 3 | 46 | 6 | 32 |

| Fmoc-FLG-O(TagB) | 4 | 35 | - | 45 |

| Fmoc-FLG-O(B2-STag) | 124 | 341 | 509 | 238 |

| Fmoc-FLG-O(B6-STag) | 549 | 790 | >1910 | - |

| H-FLG-O(B2-STag) | >1630 | >2230 | >2420 | - |

The data clearly demonstrates that silylated tags, particularly B6-STag, provide exceptional solubility enhancement, especially in environmentally friendly solvents like CPME. The absence of protecting groups (Fmoc) further increases solubility, as evidenced by the dramatic improvement in H-FLG-O(B2-STag) compared to its Fmoc-protected counterpart.

Coupling Kinetics and Reaction Efficiency

The high solubility enabled by advanced tags directly translates to improved coupling kinetics. Research has demonstrated that increased peptide concentration significantly accelerates coupling reactions, particularly for challenging sequences involving sterically hindered amino acids like α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) [11].

Table 5: Coupling Kinetics for Sterically Hindered Peptide at Different Concentrations

| Solvent | Concentration of Peptide (mM) | Conversion at 10 min (%) | Conversion at 30 min (%) | Conversion at 60 min (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPME/DMF (7:3) | 10 | 43 | 77 | 91 |

| CPME/DMF (7:3) | 100 | 94 | 99 | 99.3 |

| DMF | 10 | 27 | 56 | 74 |

| DMF | 100 | 81 | 95 | 98 |

| CPME | 10 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| CPME | 100 | 1 | 5 | 13 |

The kinetic data reveals two critical findings: first, higher concentrations (100 mM versus 10 mM) dramatically improve coupling rates across solvent systems; second, the CPME/DMF mixed solvent system outperforms pure DMF, suggesting optimized solvent environments can further enhance LPPS efficiency. This concentration-dependent acceleration is particularly valuable for synthesizing difficult sequences that typically show sluggish coupling kinetics in traditional SPPS.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

STag-Assisted Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis

The silylated tag-assisted peptide synthesis (STag-PS) platform represents a cutting-edge implementation of LPPS principles. The following continuous one-pot protocol demonstrates the streamlined workflow achievable with modern LPPS approaches [11]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Silylated tag (B2-STag or B6-STag) attached to starting amino acid

- Fmoc-protected amino acids (1.5-3.0 equivalents)

- Coupling reagents: COMU, EDCI, or DMT-MM

- Base: DIPEA (N,N-Diisopropylethylamine)

- Solvent: CPME or CPME/DMF (7:3 ratio)

- Fmoc deprotection reagent: DBU (1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene) in piperidine

- Quenching reagents: 2-(aminoethoxy)ethanol (AEE) or 2-aminoethyl hydrogen sulfate (AEHS)

- Dibenzofulvene scavenger: sodium 3-mercaptopropylsulfonate (MPSNa)

Procedure:

- Initial Coupling: Dissolve the STagged amino acid in CPME/DMF (7:3) at 100 mM concentration. Add Fmoc-protected amino acid (1.5 eq), COMU (1.5 eq), and DIPEA (3.0 eq). React for 30-45 minutes at room temperature with mixing.

Quenching: After confirming complete coupling by HPLC, add AEE or AEHS (2.4 eq) to quench any residual activated species, minimizing double-coupling side reactions.

Phase Separation: Add aqueous solution and separate phases. The STagged peptide remains in the organic phase while excess reagents, byproducts, and quenching adducts partition into the aqueous phase.

Fmoc Deprotection: Treat the organic phase containing the elongated STagged peptide with DBU/piperidine solution to remove the Fmoc protecting group. Include MPSNa to trap released dibenzofulvene, forming a water-soluble adduct.

Secondary Phase Separation: Add aqueous solution and separate phases. The deprotected STagged peptide remains in the organic phase while Fmoc-related byproducts partition into the aqueous phase.

Repetition: Repeat steps 1-5 for each subsequent amino acid addition.

Final Cleavage: After assembling the complete sequence, cleave the peptide from the STag under mild acidic conditions.

Purification: Precipitate the final peptide and purify by recrystallization or preparative HPLC.

This one-pot continuous process eliminates intermediate isolation and purification steps, significantly reducing solvent consumption and processing time compared to both traditional solution-phase and solid-phase approaches.

Critical Experimental Considerations

Solvent Selection: CPME has emerged as an ideal solvent for many LPPS applications due to its low toxicity, high stability, and excellent environmental profile [11]. Its ability to dissolve STagged peptides at high concentrations while providing a good balance of polarity makes it particularly valuable. Mixed solvent systems (CPME/DMF 7:3) can optimize solubility while maintaining green chemistry principles.

Quenching Optimization: Proper quenching of activated species after coupling is essential to prevent double-insertion side reactions. Research shows that without quenching, double-hit byproducts can reach 2.8%, while optimized quenching with AEHS reduces this to 0.1% [11].

Concentration Effects: Maintaining high concentration (≥100 mM) throughout the synthesis is critical for efficient coupling, particularly for sterically hindered sequences. The dramatic improvement in coupling kinetics at higher concentrations underscores the importance of tags that enable high solubility.

Visualization of LPPS Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous one-pot STag-assisted peptide synthesis platform, showing the repetitive cycle of coupling and deprotection with integrated purification through phase separation:

Diagram Title: Continuous One-Pot LPPS Workflow with Phase Separation

This workflow demonstrates how modern LPPS integrates reaction and purification into a streamlined process, eliminating the need for intermediate isolation and significantly reducing solvent consumption compared to traditional approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of LPPS requires careful selection of reagents and tags optimized for solution-phase chemistry. The following table details key components and their functions in modern LPPS protocols:

Table 6: Essential Reagents for Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in LPPS | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble Tags | B2-STag, B6-STag, PEG tags, Fluorous tags | Confer solubility during reactions, enable precipitation for purification | Silylated tags show exceptional solubility in green solvents like CPME [11] |

| Coupling Reagents | COMU, EDCI, DMT-MM | Activate carboxyl groups for amide bond formation | COMU shows excellent performance in STag-PS; DMT-MM generates less hazardous byproducts |

| Solvents | CPME, DMF, THF, CPME/DMF mixtures | Reaction medium for homogeneous peptide elongation | CPME offers low toxicity, high stability, and good solubility for STagged peptides [11] |

| Deprotection Reagents | DBU/piperidine mixtures | Remove Fmoc protecting groups | DBU concentration should be optimized to minimize side reactions |

| Scavengers | MPSNa, AEE, AEHS | Trap byproducts and excess reagents | MPSNa effectively scavenges dibenzofulvene during Fmoc deprotection [11] |

| Quenching Agents | AEE, AEHS | Deactivate excess activated species | Critical for minimizing double-insertion side reactions; AEHS particularly effective [11] |

Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis represents a significant advancement in the field of peptide synthesis, effectively bridging the gap between classical solution-phase and solid-phase methodologies. Within the broader context of solid-state versus fluid phase synthesis research, LPPS demonstrates how intelligent molecular design of soluble tags can overcome traditional limitations of solution-phase approaches while maintaining the benefits of homogeneous reaction environments.

The experimental data clearly shows that modern LPPS, particularly with advanced tag systems like silylated tags, enables efficient synthesis of challenging peptide sequences through enhanced solubility and improved coupling kinetics. The development of continuous one-pot protocols with integrated purification through phase separation further strengthens the environmental and economic credentials of LPPS by significantly reducing solvent consumption and waste generation.

While SPPS remains the dominant method for routine peptide synthesis, particularly for shorter sequences and high-throughput applications, LPPS has established a firm position for synthesizing longer, more complex peptides and for large-scale production where its advantages in scalability and potential cost-effectiveness become decisive. As tag technologies continue to evolve and protocols become more streamlined, LPPS is poised to expand its role in both academic research and industrial production of therapeutic peptides.

In the fields of organic chemistry, drug discovery, and materials science, the efficient construction of complex molecules often relies on iterative synthetic cycles. These cycles, composed of repeated steps of deprotection, coupling, and purification, form the foundational workflow for building complex molecular architectures piece-by-piece from simpler building blocks. The choice between the two predominant methodologies—solid-phase synthesis and fluid-phase synthesis—profoundly impacts the efficiency, scalability, and ultimate success of a synthetic campaign. Solid-phase synthesis, pioneered by Bruce Merrifield for peptide synthesis, involves covalently attaching the growing molecule to an insoluble polymer support [10] [12]. In contrast, fluid-phase synthesis, which includes both traditional solution-phase and newer automated platforms, conducts all reactions in a homogeneous liquid medium [6] [13].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of these core methodologies, focusing on their application in the iterative synthesis of peptides, oligonucleotides, and small organic molecules. By presenting structured experimental data and protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the information necessary to select the optimal synthetic strategy for their specific projects.

Core Principles and Workflow Comparison

The fundamental difference between the two methodologies lies in the handling of the growing molecular chain and the consequent purification strategies.

The Solid-Phase Synthesis Workflow

In solid-phase synthesis, the starting material is anchored to a solid support, such as polystyrene beads [10]. The synthesis proceeds through a cyclic workflow:

- Deprotection: A protecting group (e.g., Fmoc or Boc for peptides) is removed from the immobilized molecule to reveal a reactive site [10].

- Coupling: A protected building block in solution is added and reacts with the deprotected site, elongating the chain. Excess reagent can be used to drive the reaction to completion [10] [13].

- Purification: After coupling, the solution containing excess reagents and by-products is simply filtered away from the solid support. The bead-bound intermediate is washed clean, ready for the next cycle [10] [13].

- Cleavage: After the final cycle, the completed molecule is chemically cleaved from the solid support [10].

This "filter and wash" purification paradigm is a key advantage, enabling high throughput and automation [13].

The Fluid-Phase Synthesis Workflow

Fluid-phase synthesis, encompassing traditional solution-phase and advanced iterative platforms, performs all reactions in solution. Its iterative cycle consists of:

- Deprotection: The protecting group of the growing molecule in solution is removed.

- Coupling: The next building block is coupled to the deprotected molecule in solution.

- Purification: This is the critical differentiator. Unlike solid-phase, the product intermediate must be isolated from the reaction mixture after each cycle, typically requiring techniques like liquid-liquid extraction, chromatography, or catch-and-release methods [6] [13]. The MIDA boronate platform is a groundbreaking fluid-phase approach that introduces a "common purification handle." Its key innovation is a catch-and-release purification specific to the N-methyliminodiacetic acid (MIDA) boronate functional group, which is retained on silica gel with MeOH:Et₂O and eluted with THF, enabling automation [14] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and major decision points when selecting a synthesis methodology.

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

The theoretical workflows manifest in distinct practical outcomes. The following tables summarize key performance metrics and typical experimental parameters for each method.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Synthesis Methodologies

| Parameter | Solid-Phase Synthesis | Fluid-Phase Synthesis (Traditional) | Fluid-Phase (MIDA Boronate Automated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Yield per Cycle | High (driven by excess reagents) [13] | Variable, often lower | Good to high yields reported [14] |

| Purification Time per Cycle | Very Low (Filtration/Washing) [10] [13] | High (Chromatography/Extraction) [6] | Low (Automated Catch-and-Release) [14] |

| Automation Friendliness | High (Easily automated) [10] [6] | Low (Traditional methods) | High (Fully automated platform demonstrated) [14] |

| Scalability | Less amenable to scale-up [13] | Highly amenable to scale-up [13] | Demonstrated for gram-scale synthesis [14] |

| Building Block Flexibility | Requires validation for solid support [13] | High, direct transfer of classical methods [13] | High, with commercially available MIDA boronate blocks [14] |

| Reaction Monitoring | Difficult, requires cleavage from bead [13] | Straightforward (TLC, LC-MS, etc.) [13] | Integrated into automated platform [14] |

Table 2: Characteristic Experimental Conditions for Key Methodologies

| Synthetic Method | Deprotection Conditions | Coupling Conditions | Purification Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPPS (Fmoc strategy) | 20-50% Piperidine in DMF [10] | Activated amino acids (e.g., HBTU, HATU) in DMF with base [10] | Filtration and washing with DMF, DCM [10] |

| Oligonucleotide Synthesis | Acidic (e.g., Trichloroacetic acid in DCM) for 5'-DMT removal [16] | Phosphoramidite building blocks activated by e.g., 5-Ethylthio-1H-tetrazole [16] | Filtration and washing with Acetonitrile [16] |

| Automated MIDA Platform | NaOH in THF/H₂O, 23°C, 20 min [14] | Suzuki coupling: PdXPhos, K₃PO₄ [14] | Silica column; wash with MeOH:Et₂O, elute with THF [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) using Fmoc Chemistry

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a generic tetrapeptide on a polystyrene resin [10].

Materials & Reagents:

- Resin: Fmoc-Rink Amide resin (loading: ~0.5 mmol/g).

- Amino Acids: Fmoc-protected amino acids (e.g., Fmoc-Ala-OH, Fmoc-Gly-OH, etc.).

- Activating Reagents: HBTU (O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N',N'-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate) and HOBt (Hydroxybenzotriazole).

- Base: N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA).

- Deprotection Reagent: 20% (v/v) Piperidine in N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Solvents: DMF, Dichloromethane (DCM).

- Cleavage Cocktail: Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) with scavengers (e.g., 95:2.5:2.5 TFA:Triisopropylsilane:Water).

Procedure:

- Resin Swelling: Place the resin (0.1 mmol) in a solid-phase reaction vessel. Add 5 mL DCM and gently agitate for 30 minutes. Drain.

- Fmoc Deprotection: Add 5 mL of 20% piperidine in DMF. Agitate for 5 minutes. Drain. Repeat this step once. Wash the resin thoroughly with DMF (5 x 5 mL).

- Coupling Cycle: For each Fmoc-AA-OH (0.4 mmol, 4 eq.):

- Prepare a solution of Fmoc-AA-OH, HBTU (0.4 mmol, 4 eq.), and HOBt (0.4 mmol, 4 eq.) in 5 mL DMF.

- Add DIPEA (0.8 mmol, 8 eq.) to the solution, mix, and immediately transfer to the reaction vessel containing the deprotected resin.

- Agitate the mixture for 60 minutes. Drain the solution.

- Wash the resin with DMF (3 x 5 mL).

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 for each subsequent amino acid in the sequence.

- Final Deprotection: After coupling the final amino acid, perform a final Fmoc deprotection as in step 2.

- Cleavage: Wash the resin with DCM (3 x 5 mL). Treat the resin with 10 mL of the TFA cleavage cocktail for 2-3 hours with gentle agitation.

- Isolation: Filter the cleavage mixture into a cold tube. Concentrate the filtrate under a stream of nitrogen or by rotary evaporation. Precipitate the crude peptide in cold diethyl ether, centrifuge, and decant the ether to obtain the crude product.

Protocol 2: Automated Fluid-Phase Synthesis using MIDA Boronates

This protocol describes one cycle of the automated synthesis of small molecules as demonstrated by Li et al. [14].

Materials & Reagents:

- Building Blocks: MIDA boronate (e.g., compound 19 [14]) and an aryl/alkyl halide coupling partner.

- Deprotection Reagent: Aqueous Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) solution.

- Catalyst System: PdXPhos (a palladium catalyst) and K₃PO₄ (base) for Suzuki coupling.

- Solvents: Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Water (H₂O), Diethyl Ether (Et₂O), Methanol (MeOH).

- Purification Medium: Silica gel.

Procedure (Automated Cycle):

- Deprotection Module:

- The synthesizer transfers a THF solution of the MIDA boronate (e.g., 19) into a cartridge.

- Aqueous NaOH is added. The mixture is stirred at 23°C for 20 minutes to hydrolyze the MIDA ligand, releasing the reactive boronic acid.

- The reaction is quenched, and the resulting biphasic mixture is separated. The organic (THF) phase containing the boronic acid is isolated.

- Coupling Module:

- In a separate vessel, a solution of the halide coupling partner, PdXPhos, and K₃PO₄ in THF is prepared and heated.

- The synthesizer transfers the freshly prepared boronic acid solution from the deprotection module into this coupling reaction.

- The reaction mixture is stirred at elevated temperature until coupling is complete (monitored by time or other in-line analysis).

- Purification Module:

- The crude reaction mixture is passed through a column containing silica gel.

- The column is washed with a MeOH:Et₂O mixture. During this wash, the product MIDA boronate is selectively "caught" (retained) on the silica, while excess reagents and by-products are washed away.

- The eluent is switched to THF, which "releases" the purified MIDA boronate product.

- The THF solution containing the purified product is then transferred directly to the deprotection module to begin the next synthesis cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Deprotection-Coupling-Purification Cycles

| Reagent/Solvent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Piperidine | Nucleophilic base for Fmoc group removal | Deprotection in SPPS [10] |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Strong acid for final cleavage from resin & Boc group removal | Cleavage/Deprotection in SPPS [10] |

| HBTU / HATU | Peptide coupling reagents, activate carboxyl groups | Coupling in SPPS [10] |

| Phosphoramidites | Activated nucleotide building blocks | Coupling in Oligonucleotide Synthesis [16] |

| MIDA Boronates | Protected boronic acid building blocks; also act as a purification handle | Building Blocks in Automated Fluid-Phase Synthesis [14] [15] |

| PdXPhos | Palladium catalyst for C-C bond formation | Coupling in Suzuki-type reactions [14] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Polar aprotic solvent; eluent for MIDA boronate release | Solvent/Purification in Automated Platforms [14] |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Polar aprotic solvent for dissolving amino acids & reagents | Primary Solvent in SPPS [10] |

Both solid-phase and fluid-phase synthesis offer distinct pathways for executing the fundamental cycle of deprotection, coupling, and purification. Solid-phase synthesis excels in automation and purification efficiency for linear sequences like peptides and oligonucleotides, making it ideal for high-throughput applications. Its major drawback is the need to re-validate traditional "textbook" chemistry for a solid support [13].

Fluid-phase synthesis, particularly with innovations like the MIDA boronate platform, offers superior flexibility and scalability, directly leveraging the vast landscape of known solution-phase reactions [14] [13]. The historical bottleneck of purification in fluid-phase is being overcome by new strategies, enabling automation that rivals solid-phase approaches.

The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but of strategic fit. Researchers must weigh the nature of the target molecule, the required throughput, available infrastructure, and the need for derivative libraries when selecting a methodology. The ongoing integration of these platforms with automation and machine learning [17] promises to further blur the lines between them, leading to a future where the iterative synthesis of complex molecules becomes more accessible, efficient, and reliable.

In the controlled construction of complex molecules, from simple peptides to advanced inorganic materials, two classes of chemical tools are indispensable: protecting groups and coupling reagents. These components form the operational backbone of modern synthetic chemistry, enabling the precise assembly of molecular architectures by directing reactivity and preventing undesirable side reactions. Within the broader context of synthetic methodology, the choice between direct solid-state synthesis and fluid-phase synthesis often dictates the specific requirements for these tools. Solid-state approaches, characterized by reactions between solid precursors at high temperatures, often rely on structural control through crystal lattice energies and diffusion barriers [18] [19]. In contrast, fluid-phase synthesis—conducted in solution, hydrothermal, or solvothermal environments—depends heavily on solution-accessible protecting groups and high-efficiency coupling reagents to achieve specificity and high yield [20] [21]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these critical chemical reagents, framed within the paradigm of solid-state versus fluid-phase synthesis research, to inform the selection strategies of researchers and drug development professionals.

Protecting Groups: Strategic Molecular Protection

Core Functions and Classification

Protecting groups are temporary modifications applied to specific functional groups (e.g., amines, carboxylic acids, hydroxyls) to block their reactivity during synthetic steps that would otherwise affect them. Their strategic use is fundamental to achieving regioselectivity and chemoselectivity, especially when building complex molecules with multiple reactive sites.

The two primary protection schemes are defined by their orthogonal deprotection mechanisms [22]:

- Fmoc/t-Butyl Strategy: Uses a base-labile group (9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl, Fmoc) for N-terminal amine protection and acid-labile groups (e.g., tert-butyl) for side chains. Deprotection is typically achieved with piperidine.

- Boc/Benzyl Strategy: Uses an acid-labile group (tert-butyloxycarbonyl, Boc) for N-terminal protection and side-chain protection that requires strong acid (e.g., anhydrous HF) for final cleavage.

A specialized category, backbone protecting groups, is used to suppress aggregation and improve yields during peptide synthesis. By protecting the amide nitrogen itself, they disrupt inter-chain hydrogen bonding that leads to β-sheet formation, a common cause of "difficult sequences" [23].

Comparative Analysis of Protecting Group Strategies

The choice of protecting group strategy significantly impacts the efficiency, purity, and feasibility of a synthesis, particularly in fluid-phase contexts. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major protecting groups.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Protecting Groups in Synthesis

| Protecting Group | Protection Scheme | Deprotection Conditions | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmoc [23] [22] | Fmoc/t-Butyl | Base (e.g., Piperidine) | Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) | Mild deprotection conditions Orthogonal to acid-labile groups UV-active for monitoring | Repetitive base exposure can promote side reactions (e.g., aspartimide formation) |

| Boc [23] [22] | Boc/Benzyl | Acid (e.g., Trifluoroacetic Acid, TFA) | SPPS, Solution-Phase Synthesis | Stable to base and nucleophiles In-situ neutralization during Boc SPPS can reduce aggregation | Requires strong acids (TFA, HF) for final deprotection, complicating handling |

| Hmb (2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzyl) [23] | Backbone Protection | Acid (TFA) | "Difficult" peptide sequences in SPPS and LPPS | Disrupts β-sheet aggregation Enables synthesis of longer chains via improved solvation Introduced via reductive amination | Slow cleavage kinetics Risk of alkylating sensitive residues (Cys, Trp) via reactive benzylic cations |

| Pseudoprolines [23] | Backbone Protection | Acid (TFA) | Serine, Threonine, or Cysteine-rich peptides | Excellent aggregation suppression Induces favorable chain conformations | Limited to specific amino acid residues (Ser, Thr, Cys) Not a universal solution |

Experimental Protocol: Backbone Protection with Hmb

The incorporation of the Hmb backbone protecting group to mitigate aggregation during peptide synthesis is a representative advanced protocol [23].

Objective: To incorporate a 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzyl (Hmb) group at a specific amide nitrogen within a growing peptide chain to disrupt β-sheet formation and improve solubility and coupling efficiency.

Materials:

- Resin-bound peptide sequence

- Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) or dichloromethane (DCM)

- 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde

- Sodium cyanoborohydride (NaBH₃CN)

- Acetic acid

- Nitrogen atmosphere

Methodology:

- Deprotection: Fully deprotect the N-terminal amine of the resin-bound peptide using standard conditions (e.g., piperidine for Fmoc).

- Reductive Amination: a. Wash the resin thoroughly with anhydrous DMF. b. Prepare a solution of 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (5-10 equiv.) in DMF. c. Add sodium cyanoborohydride (5-10 equiv.) and a few drops of acetic acid to the solution. d. Add the mixture to the resin and agitate under a nitrogen atmosphere for 4-12 hours.

- Washing: Wash the resin sequentially with DMF, DCM, and DMF to remove excess reagents and by-products.

- Confirmation: Confirm successful Hmb incorporation via a qualitative Kaiser test for the presence of free primary amine, which should be negative.

- Chain Elongation: Continue standard peptide synthesis cycles. The Hmb-protected amino acid can be acylated efficiently due to an intramolecular O→N acyl shift facilitated by the ortho-hydroxy group.

Coupling Reagents: Forging the Molecular Link

Mechanisms and Efficiency

Coupling reagents are designed to activate carboxyl groups, making them more susceptible to nucleophilic attack by an amine to form an amide bond. The efficiency of this step is paramount, as suboptimal coupling yields lead to a rapid decrease in overall crude yield and purity, especially in long syntheses [22].

The primary classes of coupling reagents include:

- Carbodiimides (e.g., DIC, EDC): Form a highly reactive O-acylisourea intermediate upon activation of the carboxylic acid. This intermediate is then attacked by the amine to form the peptide bond. They are often used with additives like HOAt or HOBt to suppress racemization [22].

- Phosphonium/Amidinium Salts (e.g., HBTU, HATU, PyBOP): These cationic reagents activate the carboxyl group to form an active ester intermediate (e.g., with HOBt or HOAt) more rapidly than carbodiimides and with reduced epimerization risk [22].

- Propanephosphonic Acid Anhydride (T3P): A newer reagent that generates water-soluble by-products, simplifying purification. It is recognized for high yields and low epimerization in industrial applications [22].

Comparative Analysis of Coupling Reagents

The selection of a coupling reagent is a critical decision point in synthetic design. The table below provides a data-driven comparison of common reagents.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Common Coupling Reagents

| Coupling Reagent | Class | Typical Additive | Epimerization Risk | Key Characteristics & Byproducts | Ideal Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIC / DCC [7] [22] | Carbodiimide | HOBt, HOAt, Oxyma | Moderate to High | DIC: Liquid, urea byproduct is washed away. DCC: Dicyclohexylurea precipitate can be difficult to remove. | Solution-phase synthesis (DCC), SPPS (DIC) with additives |

| HBTU / HATU [22] | Amidinium Salt | HOBt (built-in), HOAt (built-in) | Low | HATU (with HOAt) is generally more efficient than HBTU (with HOBt), especially for sterically hindered couplings. | Standard SPPS, difficult couplings (HATU) |

| PyBOP / PyAOP [22] | Phosphonium Salt | HOBt (built-in), HOAt (built-in) | Low | Does not form the inactive guanidino byproduct that can occur with amidinium reagents. | General peptide coupling, fragment condensations |

| T3P [22] | Phosphonic Anhydride | Not Required | Low | Water-soluble byproducts simplify workup. High yields and commercial utility for peptide APIs. | Large-scale industrial peptide synthesis |

The Synthesis Paradigm: Solid-State vs. Fluid-Phase Context

The strategic application of protecting groups and coupling reagents is deeply intertwined with the chosen synthesis methodology.

Fluid-Phase Synthesis

This paradigm, which includes liquid-phase peptide synthesis (LPPS), sol-gel methods, and hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis, is defined by reactions occurring within a solvent medium [20] [6] [7].

- Role of Chemical Tools: Heavily reliant on protecting groups and coupling reagents.

- Advantages: Superior control over chemical composition and stoichiometry, especially for complex multi-component materials [20]. Excellent control over particle size and morphology, making it ideal for synthesizing highly dispersed nanomaterials like SiC nanoparticles and hollow fibers [20]. Enables the synthesis of metastable phases that are inaccessible via high-temperature solid-state routes [21].

- Disadvantages: Requires purification steps, risks chemical contamination, and can involve hazardous solvents and multi-step processes [20].

- Experimental Protocol - Solvothermal Synthesis of SiC Nanoparticles [20]:

- Precursor Solution: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and phenolic resin are completely dissolved in ethanol to form a sol.

- Reaction: The sol is heated to 200°C for 12 hours in a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave.

- Post-processing: The resulting precipitates are washed, dried, and then heated to 1600°C for 1 hour under an inert atmosphere for carbothermal reduction to obtain uniform SiC nanoparticles (~200 nm).

Solid-State Synthesis

This approach involves the direct reaction of solid precursors at high temperatures, a common method for producing inorganic ceramics, superconductors, and metal oxides [20] [18] [19].

- Role of Chemical Tools: Less dependent on classical protecting groups/coupling reagents. Control is achieved through physical parameters like temperature, pressure, and grinding, which overcome diffusion barriers [18] [19].

- Advantages: Simplicity, ability to create highly crystalline, thermodynamically stable products with few defects [18] [21]. No solvents required for some reactions.

- Disadvantages: High energy demands, slow diffusion rates, potential for incomplete reactions and irregular particle size/morphology [18] [21]. Limited to the most thermodynamically stable phases [21].

- Experimental Protocol - Solid-State Synthesis of Single Crystals [19]:

- Pre-treatment: Precursors are weighed, ground into a powder in an agate mortar, and preheated at 350–400°C for several hours to decompose and remove volatile products.

- Crystal Growth: The mixture is ground again for homogeneity and then heated to a high synthesis temperature (e.g., 500–2000°C) for several hours to days to facilitate nucleation and crystal growth.

- Cooling: The product is cooled at a very slow rate (e.g., 5°C per hour) to below its crystallization temperature to obtain single crystals with good crystallinity.

Diagram 1: Synthetic Workflow Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials critical for implementing the synthetic strategies discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-Protected Amino Acids [23] [22] | Building blocks for Fmoc-SPPS | Provides base-labile N-α protection; compatible with a wide range of side-chain protecting groups. |

| Hmb Protecting Group [23] | Backbone protection for "difficult" peptide sequences | Incorporated via reductive amination; disrupts β-sheet formation by creating a tertiary amide. |

| Pseudoproline Dipeptides [23] | Backbone protection for Ser, Thr, Cysteine residues | Commercially available; dramatically reduces chain aggregation by introducing a kink. |

| HATU [22] | Coupling reagent for amide bond formation | Amidinium salt with HOAt; offers fast activation and low epimerization for standard and hindered couplings. |

| DIC [22] | Coupling reagent for SPPS | Carbodiimide; liquid form for easy dispensing; used with additives like Oxyma for optimal performance. |

| T3P [22] | Coupling reagent for large-scale synthesis | Phosphonic anhydride; generates water-soluble byproducts; high yield and low epimerization. |

| Polystyrene Resin [24] [22] | Solid support for SPPS | Insoluble, solvent-swellable beaded support; functionalized with linkers for peptide attachment. |

| Precursor Salts & Oxides [18] [19] | Reactants for solid-state inorganic synthesis | High-purity powdered starting materials (e.g., carbonates, nitrates, oxides) for ceramic formation. |

| Hydrothermal Autoclave [18] [19] | Reaction vessel for fluid-phase inorganic synthesis | Sealed vessel that withstands high temperature and pressure for hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis. |

The selection of protecting groups and coupling reagents is a fundamental decision that directly dictates the success of a synthetic campaign. As this guide has detailed, the optimal choice is not made in isolation but is critically informed by the overarching synthesis paradigm. Fluid-phase methods offer unparalleled control for complex molecular assembly and metastable phases but demand a sophisticated arsenal of chemical tools to manage reactivity and solubility in solution. Solid-state synthesis, while more constrained to thermodynamic products, provides a direct, solvent-free path to highly crystalline materials, where control is exerted through physical rather than molecular means. For the modern researcher, a deep understanding of the capabilities and limitations of reagents like Hmb, HATU, and T3P, and the foresight to align them with the correct synthesis platform, is the true "chemical backbone" enabling innovation in materials science and pharmaceutical development.

The pursuit of superior solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) represents a cornerstone in the development of next-generation lithium-based batteries, which promise enhanced safety and energy density for electric vehicles and grid storage applications. The commercial viability of these advanced batteries hinges not only on material discovery but also critically on the development of scalable, efficient, and cost-effective synthesis methods. The research community is currently divided between two principal manufacturing philosophies: traditional direct solid-state synthesis and emerging fluid phase synthesis techniques. The former, often referred to as the "solid-state method" or "ceramic method," involves direct heating and reaction of solid precursor mixtures, while the latter encompasses solution-based approaches including suspension and solution synthesis in organic solvents.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing methodologies, framing the analysis within the broader thesis that fluid phase synthesis offers distinct advantages in scalability and homogeneity that may accelerate the commercialization of sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries. We present experimental data, detailed protocols, and analytical comparisons to equip researchers and development professionals with the empirical evidence needed to select appropriate synthesis routes for specific solid-state electrolyte materials.

Fundamental Synthesis Mechanisms and Workflows

Direct Solid-State Synthesis (SSM Route)

The direct solid-state synthesis, also known as the solid-state method, involves the intimate mixing of solid precursors followed by high-temperature annealing to facilitate diffusion and reaction. This route is characterized by its simplicity and avoidance of solvents, but often requires extended processing times and can result in heterogeneous products if not carefully controlled.

Experimental Protocol for Li(6)PS(5)Cl Argyrodite (SSM Route):

- Precursor Preparation: Weigh stoichiometric amounts of Li(2)S (99.98%), P(2)S(5) (99%), and LiCl (99.0%) in an argon-filled glovebox (H(2)O, O(_2) < 0.3 ppm) [25].

- Mechanical Mixing: Seal precursors in a tungsten carbide (WC)-coated stainless-steel jar with WC balls and mix at low speed (110 rpm) for 1 hour to ensure homogeneity without initiating a full mechanochemical reaction [25].

- Annealing: Transfer the homogeneous mixture to a quartz tube, seal under inert atmosphere, and anneal at 550°C for 10 hours to form crystalline Li(6)PS(5)Cl [25].

- Product Handling: Mill the resulting product gently to obtain a fine powder, maintaining strict atmospheric control to prevent hydrolysis [25].

Fluid Phase Synthesis (Liquid-Phase Route)

Fluid phase synthesis employs organic solvents as reaction media, enabling molecular-level mixing of precursors and often yielding more homogeneous products at lower temperatures. This approach is subdivided into suspension synthesis (for partially soluble systems) and solution synthesis (for fully soluble systems).

Experimental Protocol for Li(3)PS(4) via Suspension Synthesis:

- Solvent Selection: Select an aprotic polar solvent with moderate solubility and suitable donor number (DN) and dielectric permittivity. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) is commonly used [26].

- Reaction: Combine Li(2)S and P(2)S(5) (P(4)S({10})) in THF and react overnight to form an Li(3)PS(_4)·3THF complex [26].

- Solvent Removal: Remove THF under vacuum at 80°C [26].

- Crystallization: Heat the desolvated product at 140°C under vacuum to produce β-Li(3)PS(4) [26].

Advanced Protocol for Li(6)PS(5)Cl via Solution Synthesis:

- Solvent System Preparation: Use acetonitrile (ACN) and 1-propanethiol (PTH) as a co-solvent system to achieve complete dissolution while minimizing side reactions [26].

- Precursor Reaction: Dissolve Li(2)S, P(2)S(_5), and LiCl in the ACN/PTH solvent system under rigorous oxygen-free conditions [26].

- Solvent Evaporation: Remove solvents under controlled temperature and vacuum conditions [26].

- Thermal Treatment: Apply mild heat treatment to crystallize the final Li(6)PS(5)Cl product without forming oxide impurities [26].

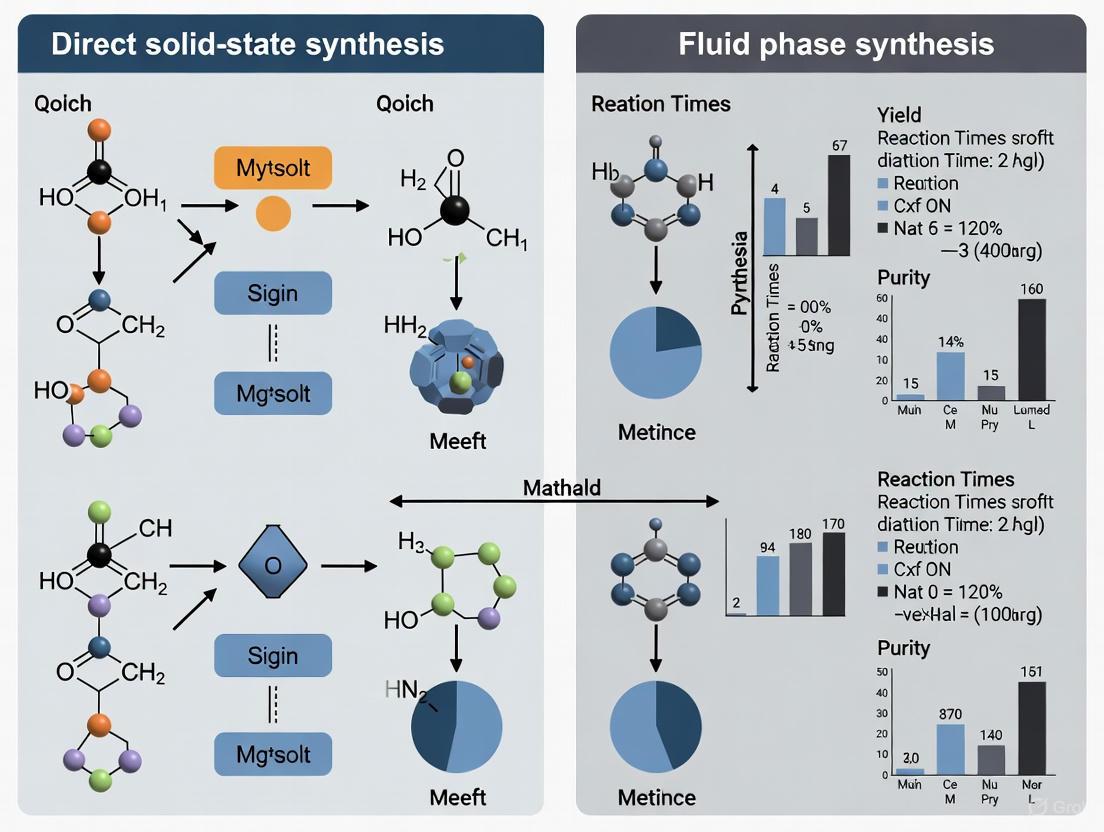

The following workflow diagram illustrates the critical decision points and procedural steps in both synthesis pathways, highlighting their comparative advantages:

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflow for Solid-State and Fluid Phase Synthesis Methods.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Quantitative Data

The following tables consolidate experimental data from published research to facilitate direct comparison between synthesis methods for key solid electrolyte materials.

Table 1: Ionic Conductivity Comparison of Li6PS5Cl Synthesized via Different Methods

| Synthesis Method | Processing Details | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Activation Energy (eV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Solid-State (SSM) | Annealing at 550°C for 10 h | 4.96 × 10−3 | 0.29 | [25] |

| Mechanical Milling + Annealing (BMA) | Ball milling + 550°C annealing | ~2.0 × 10−3 | 0.32 | [25] |

| Liquid-Phase (Ethanol) | Dissolution in ethanol | ~1.0 × 10−4 | Not reported | [26] [25] |

| Liquid-Phase (ACN/PTH) | ACN/1-propanethiol solvent | High purity achieved | Not reported | [26] |

Table 2: Processing Parameters and Material Characteristics

| Synthesis Method | Processing Temperature | Processing Time | Scalability Potential | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Solid-State (SSM) | High (550°C) | Moderate (10-24 h) | High for mixing, moderate for annealing | Limited homogeneity, high energy input |

| Mechanical Milling | Room temperature (milling) | Long (>10 h milling) | Low to moderate | Reproducibility, contamination |

| Fluid Phase (Suspension) | Low (room temp to 140°C) | Long (1-3 days) | High | Solvent removal, intermediate complexes |

| Fluid Phase (Solution) | Low (room temp to 140°C) | Moderate (hours to days) | High | Solvent purity, side reactions |

The data reveals that the direct solid-state method (SSM) produces Li(6)PS(5)Cl with the highest recorded ionic conductivity (4.96 × 10−3 S/cm), approximately double that of the traditional ball milling with annealing approach [25]. This enhanced performance is attributed to optimal local chlorine structure and homogeneous distribution throughout the material achieved through the SSM route [25]. While fluid phase methods currently yield lower conductivities (~10−4 S/cm), they offer superior purity control, as demonstrated by the successful synthesis of oxide-free Li(6)PS(5)Cl using ACN/PTH solvent systems [26].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of either synthesis methodology requires careful selection of starting materials and processing aids. The following table catalogues essential research reagents and their functions in solid-state electrolyte synthesis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Solid-State Electrolyte Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in Synthesis | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium Sulfide (Li₂S) | Lithium source | Primary reactant in both methods | Moisture sensitivity; purity critical |

| Phosphorus Pentasulfide (P₂S₅) | Phosphorus and sulfur source | Primary reactant in both methods | Air-sensitive; releases H₂S upon hydrolysis |

| Lithium Halides (LiCl, LiBr) | Halogen doping source | Enhances ionic conductivity | Affects halogen distribution in crystal lattice |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Aprotic polar solvent | Forms solvate complexes in suspension synthesis | Moderate solubility; coordinates with Li⁺ |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | Aprotic polar solvent | Complete dissolution in solution synthesis | High solubility; may require co-solvents |

| 1-Propanethiol (PTH) | Co-solvent | Prevents oxide formation in solution synthesis | Minimizes nucleophilic side reactions |

| Ethanol | Polar protic solvent | High solubility mediator | Causes substitution reactions with P₂S₅ |

| Inert Atmosphere | Reaction environment | Prevents hydrolysis and oxidation | Critical for all synthesis steps |

Emerging Innovations and Advanced Applications

Novel Synthesis Approaches for Next-Generation Electrolytes

Recent patent literature reveals innovative approaches that combine elements of both solid-state and fluid phase philosophies:

- Composite Polymer-Ceramic Architectures: Bismuth-doped lithium lanthanum zirconium oxide (LLZBO) meso-particles embedded in a poly(ethylene oxide) matrix achieve ionic conductivity up to 10−4 S/cm at room temperature [27].

- Multi-Layer Solid Electrolyte Structures: Designs incorporating variable Young's modulus layers improve adhesion between different solid electrolyte materials and prevent delamination during battery assembly [27].

- Generative Design Workflows: Machine learning models trained on molecular dynamics simulations and density functional theory calculations are being employed to predict ionic conductivity and accelerate discovery of new solid-state electrolyte materials [27].

Atomic Layer Deposition for Interface Engineering

Atomic layer deposition (ALD) has emerged as a complementary technique for engineering solid-electrolyte interfaces with desired attributes and improved stability. ALD enables conformal coating of complex 3D structures with finely controlled film thickness at the atomic scale, addressing interfacial resistance challenges in solid-state batteries [28]. This technique is particularly valuable for creating thin, conductive interlayers between lithium anodes and solid-state electrolytes to prevent undesired side reactions and formation of unstable solid-electrolyte interphases [28].

The comprehensive comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that both direct solid-state and fluid phase synthesis methods offer distinct advantages for solid-state electrolyte production. The direct solid-state method currently achieves superior ionic conductivity in argyrodite-type electrolytes, while fluid phase synthesis provides enhanced homogeneity, purity control, and potentially superior scalability.

The choice between these methodologies depends heavily on the specific performance priorities and application constraints. For fundamental research seeking maximum conductivity, the direct solid-state route appears favorable. For industrial-scale manufacturing where homogeneity, process control, and scalability are paramount, fluid phase synthesis offers compelling advantages despite its currently lower conductivity metrics.

Future research should focus on hybrid approaches that leverage the benefits of both methodologies, such as fluid phase synthesis for precursor homogenization followed by solid-state annealing for crystallization control. Additionally, machine learning-assisted materials discovery and advanced interface engineering techniques like atomic layer deposition will likely play increasingly important roles in overcoming current limitations in solid-state battery technology. As these synthesis methodologies continue to evolve, their judicious application will be critical to realizing the full potential of solid-state electrolytes in next-generation energy storage systems.

Methodology in Action: Protocols and Applications in Drug Development

Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) is a foundational technology in modern peptide and protein research, enabling the covalent assembly of amino acids on a solid support material with step-by-step addition in a single reaction vessel [10]. The development and application of commercially available automated peptide synthesizers has been essential across nearly all areas of peptide science, playing a pivotal role in addressing the challenges associated with the chemical synthesis of complex molecules like glycoproteins [29]. This methodology provides significant benefits over traditional solution-phase synthesis, including high efficiency and throughput, increased simplicity and speed, and the ability to drive reactions to completion through the use of excess reagents [10]. The practice of SPPS has evolved substantially since its inception by Robert Bruce Merrifield in 1963 [10] [29], with contemporary systems offering unprecedented capabilities for high-throughput production of peptides ranging from simple sequences to complex structures exceeding 150 amino acid residues [29].

The broader context of synthesis methodologies encompasses both solid-state and fluid-phase approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. While solid-state synthesis methods are noted for their simple equipment, convenient operation, and ability to produce materials with uniform particle size [13], they can require strict reaction conditions and high temperatures [13] and may lack good control over the final size and shape of the material [30]. In contrast, automated SPPS represents a specialized application of solid-phase synthesis that operates under relatively mild conditions, offering precise control over molecular structure through iterative coupling cycles. This guide focuses specifically on the practical implementation of automated SPPS for high-throughput production, with particular emphasis on instrument selection and the critical role of resin strategies in optimizing peptide yield and purity.

Automated Peptide Synthesizers: Comparative Analysis

The landscape of automated peptide synthesizers has evolved significantly from Merrifield's first automated system developed in 1965 [29]. Modern instruments offer varying levels of throughput, scalability, and technological sophistication to meet diverse research and production needs. The core principle underlying these systems involves the sequential addition of protected amino acids to a growing peptide chain anchored to an insoluble resin, with automated delivery of reagents and solvents through programmable metering systems [29].

Technology Evolution and Mixing Methodologies

Automated peptide synthesizers have undergone substantial technological evolution, particularly in their mixing mechanisms and synthesis methodologies:

- Batch-wise SPPS: Early systems like the ABI 430 utilized batch-wise synthesis with gas bubbling or mechanical stirring to maintain reaction suspension [29]. This approach often limited reliably synthesized peptide lengths to less than 50 amino acids due to relatively low efficiency of reagent mixing and slow mass transfer [29].

- Continuous Flow SPPS: Developed in the 1970s, this method uses a pump to provide rapid, continuous flow through the reaction vessel, significantly increasing mixing efficiency and mass transfer while decreasing coupling time [29]. Systems like the PerSeptive Biosystems Pioneer Peptide Synthesis System implemented this technology with Fmoc chemistry for more efficient synthesis [29].

- Nitrogen Bubbling and Inversion Mixing: Companies like CSBio have patented nitrogen bubbling with 180º inversion mixing, providing complete resin-to-solvent contact during synthesis [31]. This approach is particularly valued for its efficient mixing capabilities, especially for difficult sequences.

- Overhead Stirring: For larger-scale systems, pilot and commercial scale synthesizers typically utilize overhead stirring to maintain consistency and facilitate scale-up to manufacturing levels [31].

Commercially Available Automated Peptide Synthesizers

Table 1: Comparison of Representative Automated Peptide Synthesizers

| Manufacturer | Model | Scale | Reaction Vessel Capacity | Mixing Technology | Key Features | Best Application Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSBio | CSBio II | Research | 15 mL | Nitrogen bubbling & 180º inversion | Single reactor, compact design | R&D, process development |

| CSBio | CS136X | Research | 20-200 mL (up to 3 vessels) | Nitrogen bubbling & 180º inversion | Simultaneous synthesis, multiple vessels | Small-scale manufacturing, parallel synthesis |

| CSBio | CS136M | Research | 20-100 mL | Nitrogen bubbling & 180º inversion | 6-peptide parallel synthesis | High-volume R&D, small-scale GMP manufacturing |

| CSBio | Pilot Scale | Pilot | 200 mL - 5 L | Overhead stirring | Custom-built, consistency for scale-up | Process development, clinical manufacturing |

| CSBio | Commercial | Large Scale | 5 L - 800 L | Overhead stirring | Custom specifications, largest available | Commercial peptide API production |

| Biotage | Initiator+ Alstra | Research | Not specified | Not specified | Fully automated, single-channel microwave | Sequential single peptide synthesis |

| Biotage | Syro I | Research | Not specified | One-arm pipetting robot | Multi-channel, parallel synthesis | Lab-scale parallel synthesis requirements |

| Biotage | Syro II | Research | Not specified | Two-arm pipetting robot | Multiple reactor blocks | Highest throughput for lab-scale parallel synthesis |

Vendor Selection Criteria for Different Scenarios

Choosing the appropriate automated peptide synthesizer depends heavily on specific research or production requirements [32]:

- Academic Research Labs: Typically benefit from flexible, bench-top research scale systems like the CSBio CS136X or Biotage Initiator+ Alstra that offer balance between capability and cost-effectiveness for producing diverse peptide libraries [31].

- Pharmaceutical R&D: Requires robust systems capable of process development and small-scale GMP manufacturing, such as the CSBio CS136M with parallel synthesis capabilities [31].

- Process Development & Scale-up: Pilot scale systems (200 mL - 5 L) with overhead stirring are essential for developing processes transferable to commercial manufacturing [31].

- Commercial API Production: Large-scale systems (5 L - 800 L) designed for continuous GMP manufacturing, where CSBio reports the largest installation base worldwide [31].

User testimonials highlight specific advantages of different systems. One pharmaceutical company director noted: "I have been a peptide chemist for some time, I have worked with many different synthesizers, Symphony, Liberty, etc... This CS136 from CSBio is the first one I have really LIKED" [31]. Another researcher observed: "We have a CSBio and CEM peptide synthesizer. When we can't make a peptide on the CEM, we make it on the CSBio system" [31], suggesting variability in performance across different peptide sequences and highlighting the potential value of multiple systems in a core facility.

Resin Selection Strategies for High-Throughput Production

The selection of appropriate solid supports represents one of the most critical factors in successful SPPS, directly influencing crude yield, purity, and the ability to synthesize challenging sequences. As noted by Biotage, "The resin you select plays a crucial role in the success of your peptide synthesis" [33]. The resin not only serves as an anchor for the growing peptide chain but also affects the kinetics of coupling and deprotection reactions through swelling properties and accessibility of reactive sites.

Resin Selection Framework and Optimization Approaches

An optimization-based decision support framework has been developed to address the complex challenge of resin selection for integrated chromatographic separations in high-throughput screening environments [34]. This systematic methodology processes data generated from microscale experiments to identify the best resins for maximizing key performance metrics in biopharmaceutical manufacturing processes, such as yield and purity [34].

The framework utilizes a multiobjective mixed integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) model solved using the ε-constraint method, with Dinkelbach's algorithm applied to resolve the resulting mixed integer linear fractional programming model [34]. This computational approach enables rapid analysis of substantial data volumes generated from high-throughput screening experiments, where numerous resins and operating conditions must be evaluated simultaneously.

Key aspects of this resin selection framework include:

- Performance Metric Optimization: The model simultaneously optimizes for multiple performance criteria, including yield, purity, and productivity, which may have competing requirements [34].

- Mass Balance Integration: Unlike earlier approaches that ignored mass balance between consecutive chromatographic steps, this framework correctly calculates yield and purity across multi-step processes by establishing mass relationships between steps [34].

- Operating Condition Integration: The model incorporates chromatography operating conditions for each resin, including pH values, salt concentrations, and flow rates, which significantly impact resin performance [34].

- Collection Time Optimization: The framework optimizes starting and finishing time intervals for target protein collection, which are linked to salt concentration in gradient elution [34].

Experimental Protocol for Resin Screening and Selection

The resin selection process begins with high-throughput screening (HTS) microscale experiments typically conducted at volumes ranging from 1.5–5000 µL [34]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Resin Preparation: A set of potential chromatography resin candidates is selected for each chromatographic separation step in the purification process.

- Condition Screening: Each resin is tested under various operating conditions, with each condition representing unique combinations of pH and salt concentration [34].