Smoothing Noisy Data in Materials Science: Advanced Techniques for Reliable Discovery and Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on managing noisy data in materials research.

Smoothing Noisy Data in Materials Science: Advanced Techniques for Reliable Discovery and Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on managing noisy data in materials research. It explores the critical impact of data noise on discovery outcomes, details a suite of smoothing techniques from foundational to advanced machine learning methods, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing data processing pipelines. By comparing the performance of various techniques against established benchmarks, the guide empowers professionals to select and validate the most effective smoothing approaches, thereby enhancing the reliability and acceleration of materials and drug development processes.

Understanding Noise in Materials Data: Sources, Impacts, and Foundational Smoothing Concepts

The Critical Problem of Noise in Experimental Materials Data

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating Noise

Encountering noise in your datasets can be a major roadblock. Use this guide to diagnose the source and identify the appropriate solution.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Source of Noise | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variance in property predictions (e.g., band gap) from different calculation methods. | Systematic errors from computational approximations (e.g., DFT exchange-correlation functionals). | Apply a multi-fidelity denoising approach or linear scaling to align data points [1]. | [1] |

| A few outlying data points are disproportionately influencing your model's results. | Random outliers with a finite probability, often from experimental scatter or specimen variability [2]. | Implement a max-ent Data Driven Computing paradigm that is robust to outliers through clustering analysis [2]. | [2] |

| A "good" ML model performs poorly on your dataset, or model rankings change unpredictably. | High aleatoric uncertainty (inherent experimental noise) limiting model performance [3]. | Quantify the realistic performance bound for your dataset and compare it to your model's accuracy [3]. | [3] |

| Time-series or sequential data is too wobbly to identify a clear trend. | Random noise inherent in the measurement tool or processing errors [4]. | Apply a smoothing technique like the Whittaker-Eilers smoother, LOWESS, or Savitzky-Golay filter [5]. | [5] |

| Data is gappy or unevenly spaced, in addition to being noisy. | Missing measurements due to experimental constraints or failed data collection. | Use an interpolating smoother like the Whittaker-Eilers method, which can handle gaps and unequal spacing [5]. | [5] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is "noise" in the context of materials data? Noise refers to any unwanted variance or distortion in your data that obscures the underlying "true" signal or relationship you are trying to measure. This includes both random noise (e.g., from measurement tools) and systematic biases (e.g., from imperfect computational functionals) [6] [1] [4]. From a machine learning perspective, noise is anything that prevents the model from learning the true mapping from structure to property, including experimental scatter and systematic errors [1].

Q2: My computational data (e.g., from DFT) has known systematic errors. How can I use it to train a model for experimental properties? You can use multi-fidelity denoising. This approach treats the systematic errors and random variations in your computational data as "noise" to be cleaned. By using a limited set of high-fidelity experimental data as a guide, you can denoise the larger set of low-fidelity computational data, creating a more accurate and larger training dataset [1]. For example, scaling DFT-calculated band gaps via linear regression before training can significantly improve model performance [1].

Q3: How do I know if my machine learning model is fitting the true signal or just the noise in my data? You can estimate the aleatoric limit or realistic performance bound of your dataset. This bound is determined by the magnitude of the experimental error in your data. If your model's performance (e.g., R² score) meets or exceeds this theoretical bound, it is likely that your model is starting to fit the noise, and further improvement may not be possible without higher-quality data [3]. The larger the experimental error and the smaller the range of your data, the lower this performance bound will be [3].

Q4: What is a simple, fast method for smoothing a noisy time-series of material properties? The Whittaker-Eilers smoother is an insanely fast and reliable method for smoothing and can also handle interpolation across gaps in the data. It requires only a single parameter (λ) to control smoothness and does not need a window length, making it easier to use than methods like Savitzky-Golay or Gaussian kernels [5].

Q5: In clinical trials or observational studies for drug development, how does noise manifest and how can it be reduced? Noise in clinical trials can arise from postrandomization bias, where events during the trial (e.g., differences in rescue medication use) create an imbalance in noise between groups that wasn't present at baseline [6]. In observational studies, confounding variables are a major source of noise. Noise can be reduced through linear, logistic, or proportional hazards regression, which statistically adjust for measured confounding variables [6].

Experimental Protocols for Handling Noisy Data

Protocol 1: Multi-Fidelity Denoising for Computational Materials Data

This protocol is designed to improve the prediction of a target property (e.g., band gap) by leveraging a small amount of high-fidelity data (e.g., experimental values) and a large amount of lower-fidelity data (e.g., calculated with different DFT functionals) [1].

Data Collection & Splitting:

- Gather your high-fidelity dataset (e.g., experimental band gaps,

E). - Gather one or more low-fidelity datasets (e.g., DFT-calculated band gaps,

P,H,S,G). - Split the high-fidelity data into training and test sets.

- Gather your high-fidelity dataset (e.g., experimental band gaps,

Initial Analysis (Raw Data):

- For each low-fidelity dataset, calculate the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Error (ME) against the high-fidelity training data. This quantifies the systematic and random noise.

- Visually inspect the correlation via scatter plots (e.g.,

PvsE).

Scaling (Optional):

- Perform a linear regression (

T = aP + b + δ) for each low-fidelity data type using the high-fidelity training data. - Scale the entire low-fidelity dataset using the derived

aandbparameters. This simple step can reduce systematic error [1].

- Perform a linear regression (

Denoising Training:

- The core denoising process involves training a model to predict the high-fidelity value using the low-fidelity values and material descriptors.

- This can be framed as a supervised learning task where the model learns to "clean" the noisy, low-fidelity input to match the high-fidelity target.

Model Application:

- Apply the trained denoising model to the entire low-fidelity dataset to generate a denoised, more accurate dataset.

- This new, larger denoised dataset can now be used to train a final, more robust predictive model.

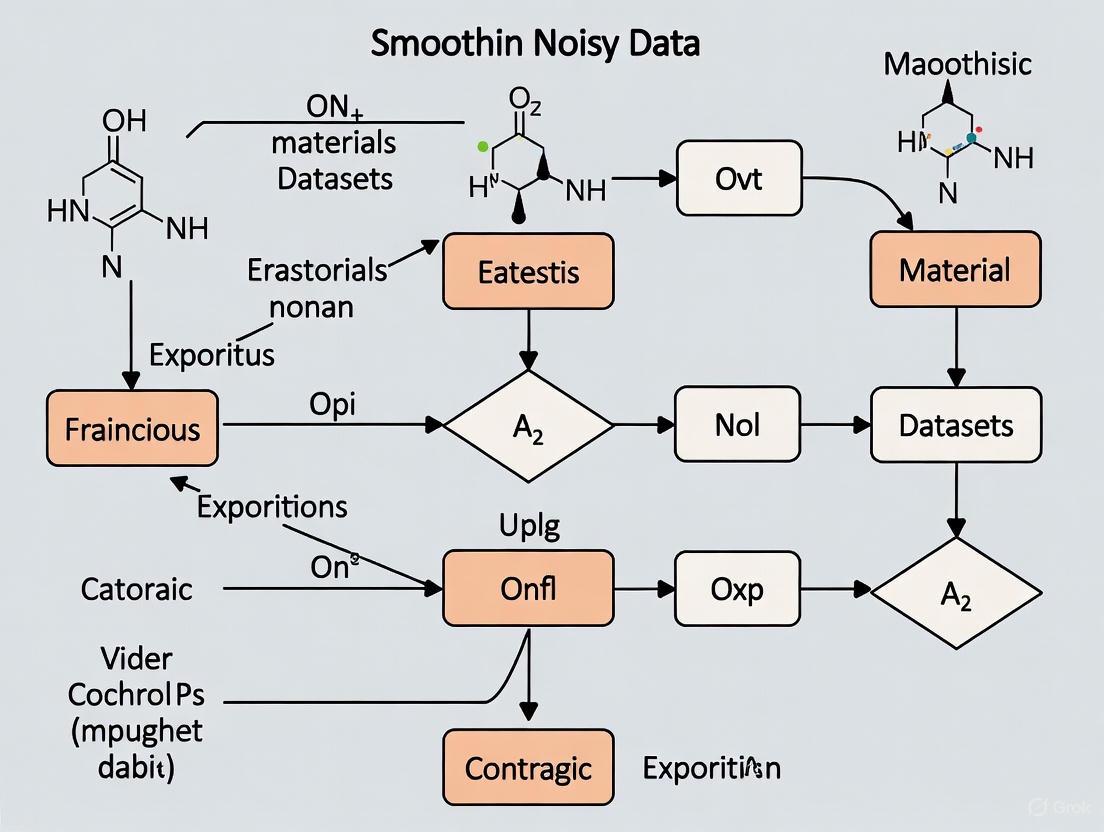

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-fidelity denoising process:

Protocol 2: Maximum-Entropy Data Driven Computing for Noisy Data with Outliers

This paradigm bypasses traditional material modeling altogether, finding the solution directly from the material data set in a way that is robust to outliers [2].

Problem Setup:

- Define the field equations (compatibility and equilibrium constraints) for your mechanical problem.

- Gather your material data set, which consists of points in phase space (e.g., stress-strain pairs). This data is assumed to be noisy and may contain outliers.

Relevance Assignment:

- Instead of finding the single closest data point to the constraint set, assign a variable relevance to every data point.

- The relevance is calculated based on the distance to the current solution estimate using a maximum-entropy (max-ent) principle. This means a cluster of many consistent data points can override a single outlier that happens to be closer to the constraints.

Free Energy Minimization:

- The solution is found by minimizing a suitably defined free energy over the phase space, subject to the field equations.

- This free energy is a function of the state and incorporates the relevance of all data points.

Solving via Simulated Annealing:

- A simulated annealing scheme can be used for the minimization.

- The process starts at a higher "temperature," where the relevance of data points is more uniform.

- The temperature is progressively reduced ("annealed"), which gradually zeros in on the most relevant cluster of data points and the attendant solution.

The logical flow of this robust approach is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Solutions

This table details essential computational tools and methodological approaches for handling noise in materials science.

| Tool / Solution | Function | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Whittaker-Eilers Smoother [5] | Smoothing and interpolation of noisy, gappy, or unevenly-spaced sequential data. | lmbda (λ): Controls smoothness. order (d): Controls the polynomial order of the fit. |

| Max-Ent Data Driven Solver [2] | A computing paradigm that finds mechanical solutions directly from noisy data clusters, robust to outliers. | Temperature: A parameter in the annealing schedule controlling the influence of data point clusters. |

| Multi-Fidelity Denoiser [1] | A model that cleans systematic and random noise from low-fidelity data using a guide set of high-fidelity data. | The choice of machine learning model (e.g., neural network) and the ratio of high-to-low-fidelity data used for training. |

| FLIGHTED Framework [7] | A Bayesian method for generating probabilistic fitness landscapes from noisy high-throughput biological experiments (e.g., protein binding assays). | Priors and distributions modeling the known sources of experimental noise (e.g., sampling noise). |

| Performance Bound Estimator [3] | A tool to calculate the maximum theoretical performance (aleatoric limit) for a model trained on a given dataset, based on its experimental error. | σE: The estimated standard deviation of the experimental error in the dataset. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between label noise and signal noise? Label noise is an error in the target variable (the output you are trying to predict), such as a misclassified image in a training set. Signal noise, on the other hand, refers to corruption in the input features or measurement data, like random fluctuations in a sensor reading.

2. Which type of noise is more detrimental to a machine learning model? Both can be highly detrimental, but their impact differs. Label noise often directly misguides the learning process, causing the model to learn incorrect patterns. Signal noise can obscure the true underlying relationships in the data, making it difficult for any model to find a meaningful signal.

3. Can the same techniques be used to handle both types of noise? Generally, no. Techniques for handling label noise often involve data inspection and re-labeling, or using robust algorithms. Signal noise is typically addressed through data pre-processing like smoothing or filtering. The experimental protocols section below details specific methodologies for each.

4. How can I visually diagnose the type of noise in my dataset? Visualization is a key first step. For signal noise in continuous data, use line plots or scatter plots to see random fluctuations around a trend. For label noise in classification, visualizing sample instances (e.g., images) from misclassified groups can reveal systematic labeling errors.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model performance is poor, and I suspect noisy data.

- Step 1: Diagnose the Noise Type. Begin by visualizing your input features and analyzing label distributions. This helps determine if you are dealing primarily with signal noise, label noise, or a combination of both.

- Step 2: Apply Targeted Techniques. Based on your diagnosis:

- For Signal Noise, apply smoothing techniques like the Kalman Filter (see protocol below) or moving averages to your input data.

- For Label Noise, implement label correction or use model-based approaches like robust loss functions.

- Step 3: Validate and Iterate. Use robust validation techniques like k-fold cross-validation to assess the improvement. The process of cleaning and smoothing is often iterative.

Problem: My smoothed data is losing important short-term patterns.

- Potential Cause: Over-smoothing. The parameters of your smoothing technique (e.g., the window size in a moving average) are too aggressive.

- Solution: Tune the smoothing parameters. A smaller window size in a moving average or adjusting the transition covariance in a Kalman Filter will preserve more of the high-frequency signal. Domain knowledge is critical here to distinguish noise from important, short-duration phenomena.

Experimental Protocols for Noise Handling

Protocol 1: Smoothing Signal Noise with a Kalman Filter

The Kalman Filter is an algorithm that uses a series of measurements observed over time, containing statistical noise, to produce estimates of unknown variables that tend to be more precise than those based on a single measurement alone [8].

Methodology:

- Define the State Transition Model: This model describes how the true state evolves from time step k-1 to k. For a simple 1D system, this can be

x_k = A * x_{k-1} + w_k, whereAis the transition matrix andwis the process noise. - Define the Observation Model: This model describes how the measurements are derived from the true state. For a direct measurement,

z_k = H * x_k + v_k, whereHis the observation matrix andvis the measurement noise. - Initialize the Filter: Set initial values for the state estimate and the error covariance.

- Iterate through the data: For each new measurement, the filter performs a two-step process:

- Predict: Project the current state and error covariance forward.

- Update: Incorporate the new measurement to refine the state estimate.

- Tune the Noise Covariances: The performance is highly dependent on the chosen process and measurement noise covariances (

QandR). These are often tuned empirically.

Example Python Code Snippet [8]:

Protocol 2: Correcting Label Noise with Ensemble Methods

Ensemble methods combine multiple models to improve robustness and can be effective in mitigating the effects of label noise.

Methodology:

- Train Multiple Models: Use algorithms like Random Forests, which are inherently ensemble methods, or create a bagging ensemble of other base classifiers (e.g., Decision Trees).

- Leverage Aggregate Predictions: The ensemble's collective decision (e.g., through majority voting for classification) is less sensitive to the noise present in the training labels of any single model.

- Identify Potential Label Errors: Instances where the ensemble prediction consistently disagrees with the provided label across different validation folds are strong candidates for being mislabeled. These can be flagged for manual review.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and their functions for handling noisy data in research.

| Reagent Solution | Function in Noise Handling |

|---|---|

| Kalman Filter [8] | Recursive algorithm for optimally estimating the state of a process by smoothing out measurement noise in time-series data. |

| Moving Average / Exponential Smoothing [9] | Simple filtering techniques that reduce short-term fluctuations in signal noise by averaging adjacent data points. |

| Robust Loss Functions | Loss functions (e.g., Huber loss) that are less sensitive to outliers and noisy labels compared to standard losses like MSE. |

| Random Forest / Ensemble Methods | Combines multiple learners to average out errors, providing robustness against both label and feature noise. |

| SimpleImputer [9] | A tool for handling missing values (a form of data noise) through strategies like mean, median, or mode imputation. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [9] | A dimensionality reduction technique that can help mitigate the impact of noise by projecting data onto a lower-dimensional space of principal components. |

Visualizing Noise Categorization and Handling

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of noise categorization and the primary pathways for handling it, as discussed in this guide.

Workflow for Signal Noise Smoothing

This workflow details the specific steps for applying a smoothing technique like the Kalman Filter to a univariate dataset, a common scenario in materials research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues with Noisy Data

Q1: My model performs well on training data but generalizes poorly to new, unseen data. Could noise be the cause?

Yes, this is a classic symptom of overfitting, where a model learns the noise in the training data rather than the underlying signal. Noise can cause a model to memorize specific, irrelevant details in the training set, impairing its ability to perform well on validation or test data [10] [11]. Adding a small amount of noise during training can act as a regularizer, making the model more robust by forcing it to learn features that are invariant to small perturbations [11].

Q2: What are the primary sources of noise in materials science datasets?

Noise in datasets can originate from several stages of data collection and handling [10] [12]:

- Measurement Errors: Inaccurate instruments or varying environmental conditions during data acquisition [10].

- Data Collection & Annotation Errors: Human error during data entry or incorrect labeling of data points, which introduces erroneous supervision signals for the model [10] [12].

- Inherent Variability: Natural fluctuations or unforeseen events in experimental processes [10].

Q3: How does the problem landscape affect the impact of noise on my model?

The effect of noise is not uniform and depends heavily on the structure of the problem you are modeling. A study on Bayesian Optimization in materials research found that noise dramatically degrades performance on complex, "needle-in-a-haystack" problem landscapes (e.g., the Ackley function). In contrast, on smoother landscapes with a clear global optimum (e.g., the Hartmann function), noise can increase the probability of the model converging to a local optimum instead [13].

Q4: What can I do if my dataset has both noisy labels and a class imbalance?

This is a common challenge in real-world materials data. A proposed solution is a two-stage learning network that dynamically decouples the training of the feature extractor from the classifier. This is combined with a Label-Smoothing-Augmentation framework, which softens noisy labels to prevent the model from becoming overconfident in incorrect examples. This integrated approach has been shown to improve recognition accuracy under these challenging conditions [12].

Quantitative Impact of Noise

The table below summarizes how different types of noise can quantitatively impact model training and validation.

| Noise Type | Source | Impact on Model Performance | Quantitative Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Noise [10] | Irrelevant/superfluous features, measurement errors [10] | Confuses learning process; reduces model accuracy and reliability [10] | Increased generalization error; models may fit spurious correlations [11] |

| Label Noise [12] | Human annotation errors, data handling issues [12] | Causes model overfitting to incorrect labels; degrades diagnostic performance [12] | ~2%+ accuracy drop in fault diagnosis; model overconfidence in wrong predictions [12] |

| Input Noise (Jitter) [11] | Small, random perturbations to input data [11] | Can improve robustness and generalization when added during training (regularization effect) [11] | Can lead to "significant improvements in generalization performance" [11] |

| Noise in Complex Problem Landscapes [13] | Experimental variability in materials research [13] | Dramatically degrades optimization results in "needle-in-a-haystack" searches [13] | Higher probability of landing in local optima instead of global optimum [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Noise

Protocol 1: Adding Input Noise (Jitter) to Neural Networks

This protocol uses additive Gaussian noise as a regularization technique to prevent overfitting [11].

- Preprocess Data: Normalize or standardize input variables to a consistent scale [11].

- Generate Noise: For each input pattern presented to the network during training, generate a random noise vector. The noise is typically drawn from a Gaussian distribution with a mean of zero and a configurable standard deviation [11].

- Add Noise: Add the random noise vector to the input pattern before it is fed into the network. A new random vector is added each time a pattern is recycled (each epoch) [11].

- Train Model: Proceed with the forward and backward passes of training using the noisy inputs.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use cross-validation to choose the optimal standard deviation for the noise. Too little noise has no effect; too much makes the mapping function too difficult to learn [11].

- Evaluation: Crucially, no noise is added during model evaluation or when making predictions on new data [11].

Protocol 2: Label Smoothing for Noisy Labels

This protocol reduces model overconfidence and improves robustness to label noise [12].

- Identify Noisy Labels: Implement a mechanism to perceive potentially noisy labels. This can be based on loss distribution (samples with high loss are more likely to be mislabeled) or through a separate clean/noisy sample separation algorithm [12].

- Smooth Labels: Instead of using hard, one-hot encoded labels (e.g.,

[0, 0, 1, 0]), convert them to soft labels. This is done by reducing the confidence of the target class and distributing a small amount of probability to the non-target classes [12]. - Adaptive Smoothing (Advanced): Dynamically adjust the smoothing factor based on the perceived noisiness of each sample or the overall dataset, rather than applying a uniform smoothing factor to all labels [12].

- Train Model: Use the smoothed soft labels to calculate the loss function during training (e.g., Cross-Entropy) [12].

Workflow Diagram for Noise Mitigation

The following diagram illustrates a high-level workflow for diagnosing and mitigating the impact of noise in a machine learning pipeline for materials research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational and methodological "reagents" for designing experiments that are robust to noise.

| Tool / Technique | Function | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Noise (Jitter) [11] | Regularizes model by adding random perturbations to input features during training. | Preventing overfitting; improving model robustness and generalization [11]. |

| Label Smoothing [12] | Softens hard labels, reducing model overconfidence and mitigating impact of label noise. | Handling datasets with inaccurate or noisy annotations [12]. |

| Dynamic Decoupling Network [12] | Separates training of feature extractor and classifier to minimize interference from imbalanced and noisy data. | Learning from datasets with severe class imbalance co-occurring with noisy labels [12]. |

| Denoising Autoencoders [10] [11] | Neural network trained to reconstruct clean inputs from corrupted (noisy) versions. | Learning robust feature representations; data denoising [10] [11]. |

| Cross-Validation [10] | Resampling technique to assess model generalization and tune hyperparameters (e.g., noise std. dev.). | Providing a more reliable estimate of model performance on unseen data [10] [11]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [10] | Dimensionality reduction technique that can project data to focus on informative dimensions and discard noise-related dimensions. | Noise reduction; data compression and visualization [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is noise always detrimental to my model's performance? A: Not necessarily. While noise often degrades performance, intentionally adding small amounts of noise during training can serve as a effective regularization technique, "smearing out" data points and preventing the network from memorizing the training set, which can ultimately lead to better generalization [11].

Q: Where in my model architecture can I add noise? A: Noise can be introduced at various points, each with different effects:

- Inputs: Most common, acts as data augmentation [11].

- Weights: Particularly useful in Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), encourages function stability [11].

- Activations / Outputs: Can be used to regularize very deep networks or handle noisy labels [11].

Q: How do I determine the right amount of noise to add? A: The optimal amount (e.g., the standard deviation of Gaussian noise) is a hyperparameter. It is recommended to standardize your input variables first and then use cross-validation to find a value that maximizes performance on a holdout dataset. Start with a small value and increase until performance on the validation set begins to degrade [11].

Q: My dataset is small and imbalanced. Will adding noise help? A: Yes, this can be a particularly useful scenario. For small datasets, adding noise is a form of data augmentation that effectively expands the size of your training set and can make the input space smoother and easier to learn [11]. For co-occurring label noise and imbalance, combined strategies like dynamic decoupling with label smoothing are recommended [12].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Why is my smoothed signal distorting the true peak positions in my SPR biosensor data?

This occurs when the smoothing technique or its parameters are not well-suited to your data's characteristics. An overly aggressive filter can eliminate genuine signal features along with the noise.

Solution:

- Use a Savitzky-Golay filter: This filter is specifically designed to preserve higher moments of the data distribution, like peaks and widths, which is crucial for accurately determining resonance angles in SPR analysis [14].

- Adjust the filter parameters: For the Savitzky-Golay filter, use a low-order polynomial (e.g., quadratic or cubic) and a window size that is wide enough to reduce noise but smaller than the width of the narrowest peak you wish to preserve [14].

- Validate with a synthetic dataset: Create a known, clean signal with peaks at specific positions, add artificial noise, and apply your smoothing. Compare the resulting peak locations to the originals to quantify distortion [15].

How do I choose the right smoothing technique for my noisy materials dataset?

The best technique depends on the type of noise and the features of your signal you need to preserve. The table below summarizes the primary methods.

| Smoothing Technique | Best For | Key Parameters | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exponentially Weighted Moving Average (EWMA) [15] [14] | Reacting to recent changes; giving more weight to recent data points. | Smoothing factor (α) between 0 and 1. | Simple to implement but can lag trends. |

| Savitzky-Golay Filter [14] | Preserving signal features like peak heights and widths (e.g., in SPR spectra). | Polynomial order, window size. | Excellent for retaining the shape of spectral lines. |

| Gaussian Filter [14] | General noise reduction where precise feature preservation is less critical. | Standard deviation (σ) of the kernel. | Effective at suppressing high-frequency noise. |

| Smoothing Splines [14] | Creating a smooth, differentiable curve from noisy data. | Smoothing parameter. | Provides a continuous and smooth function. |

| Kalman Filter [15] | Real-time, recursive estimation in dynamic systems with a state-space model. | Process and measurement noise covariances. | Powerful for systems that change over time. |

My smoothed data appears too "jumpy" and still contains a lot of noise. What should I do?

This indicates that your smoothing is not aggressive enough and is underfitting the data.

Solution:

- Increase the smoothing intensity: For a Gaussian filter, increase the standard deviation (σ). For a moving average or Savitzky-Golay filter, increase the window size. For exponential smoothing, decrease the smoothing factor (α) [15] [14].

- Apply a two-stage filtering process: First, use a mild pass of one filter to remove high-frequency spikes, followed by a second pass with a different filter to handle broader noise fluctuations.

- Check for outliers: Before smoothing, use statistical methods to identify and potentially remove significant outliers, as they can disproportionately influence the smoothed curve [15].

How can I validate the performance of my smoothing algorithm?

A robust smoothing method should effectively reduce noise without distorting the underlying signal.

Solution:

- Analyze the residuals: Subtract the smoothed signal from the original noisy data. A well-smoothed signal will have residuals that resemble random noise (white noise) with no obvious patterns or trends [15].

- Diagnostic plots: Create visualizations of the residuals over time. The residuals should be centered around zero and exhibit no discernible patterns [15].

- Quantitative metrics: If you have a ground truth signal, calculate metrics like the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the smoothed signal and the true signal. For real data where the true signal is unknown, the reduction in variance from the original to the smoothed data can be a useful indicator.

Experimental Protocol: Applying Smoothing to SPR Biosensor Data

This protocol outlines the steps for using smoothing techniques to enhance the analysis of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensor data, a common challenge in materials and biological research [14].

Objective

To reduce experimental noise in SPR reflectance spectra for accurate and reliable determination of the resonance angle.

Materials and Equipment

- Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| SPR Biosensor Setup (Kretschmann configuration) | Optical system to excite surface plasmons and measure reflectance [14]. |

| Prism, Metal Film (e.g., Gold), Flow Cell | Core components of the sensor where molecular interactions occur [14]. |

| Analyte Samples | The substances to be detected and measured. |

| Data Acquisition Software | Records raw angular or spectral reflectance data. |

| Computational Tool (e.g., MATLAB, Python) | Applies smoothing algorithms and data analysis [14]. |

Methodology

- Data Collection: Acquire the raw SPR reflectance curve as a function of the incident angle or wavelength.

- Data Preprocessing: Import the experimental data into your computational tool.

- Algorithm Selection: Based on your data's characteristics, select an appropriate smoothing technique from the table above. For SPR data, the Savitzky-Golay filter is often recommended for peak preservation [14].

- Parameter Configuration: Set the initial parameters for the chosen filter (e.g., window size and polynomial order for Savitzky-Golay).

- Application & Iteration: Apply the smoothing filter. Visually inspect the result to ensure the resonance dip is preserved while noise is reduced. Adjust parameters iteratively if necessary.

- Validation: Perform residual analysis to check that the smoothed signal has not been distorted.

- Analysis: Determine the resonance angle from the minimum of the smoothed reflectance curve.

Workflow Diagram

FAQs on Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: What is the fundamental goal of smoothing in data analysis? Smoothing is designed to detect underlying trends in the presence of noisy data when the shape of that trend is unknown. It works on the assumption that the true trend is smooth, while the noise represents unpredictable, short-term fluctuations around it [16].

Q2: How does bin smoothing work? Bin smoothing, a foundational local smoothing approach, operates on a simple principle:

- Group Data: Data points are grouped into small intervals, or "bins" [16] [17].

- Assume Constant Trend: The value of the underlying trend is assumed to be approximately constant within each small bin [16].

- Calculate Summary Statistic: Each value in a bin is replaced by a single summary statistic for that bin. Common methods include [17]:

- Bin Means: Replacing values with the mean of the bin.

- Bin Median: Replacing values with the median of the bin.

- Bin Boundaries: Replacing values with the closest minimum or maximum boundary value of the bin.

Q3: What is a Moving Average, and how is it different? A Moving Average (also called a rolling average or running mean) smooths data by creating a series of averages from different subsets of the full dataset [18]. Unlike basic bin smoothing, it is typically applied sequentially through time. The core difference from some bin methods is that the "window" of data used for the average moves forward one point at a time, often resulting in a smoother output [18] [19].

Q4: When should I use a Simple Moving Average (SMA) versus an Exponential Moving Average (EMA)? The choice depends on your need for responsiveness versus smoothness.

| Feature | Simple Moving Average (SMA) | Exponential Moving Average (EMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Weighting | Applies equal weight to all data points in the window [20]. | Gives more weight to recent data points [20]. |

| Responsiveness | Less responsive to recent price changes; smoother [20]. | More responsive to recent changes; can capture trends faster [20]. |

| Lag | Generally has a higher lag compared to EMA [20]. | Reduces lag by emphasizing recent data [20]. |

| Calculation | Straightforward (sum of values divided by period count) [20]. | More complex, as it uses a multiplier based on the previous EMA value [20]. |

Q5: What are common problems with basic binning methods? Traditional binning methods, like Vincentizing or hard-limit binning, can suffer from several issues [21]:

- Signal Distortion: The arbitrary choice of bin number and location can distort the true shape of the underlying trend.

- Reduced Temporal Resolution: Vital details can be lost when compressing data into a small number of bins.

- Statistical Complications: If bins have an unequal number of data points or are misaligned across participants in a study, performing valid statistical tests becomes difficult.

Q6: What is a more advanced alternative to simple bin smoothing? Local weighted regression (LOESS) is a powerful and flexible smoothing technique. Instead of assuming the trend is constant within a window, it assumes the trend is locally linear [16]. This allows for the use of larger window sizes, which increases the number of data points used for each estimate, leading to more precise and often smoother results. LOESS also uses a weighted function (like the Tukey tri-weight) so that points closer to the center of the window have more influence on the fit than points farther away [16].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: My smoothed data still looks too noisy and jagged.

- Potential Cause: The smoothing window (bandwidth or span) is too small.

- Solution: Increase the size of your smoothing window. For a moving average, this means increasing the number of periods (e.g., using a 7-day instead of a 3-day average). For LOESS, increase the

spanparameter, which controls the proportion of data used in each local fit [16]. A larger window will produce a smoother output.

Problem 2: My smoothed data appears oversmoothed and misses important trends or peaks.

- Potential Cause: The smoothing window is too large.

- Solution: Decrease the size of your smoothing window. A smaller window is more responsive to rapid changes and local features in the data but will be less effective at filtering out noise.

Problem 3: I need to emphasize recent data points more than older ones in a time series.

- Potential Cause: You are using a smoothing method that gives equal weight to all data points in the window (like a Simple Moving Average).

- Solution: Switch to a Weighted Moving Average or an Exponential Moving Average (EMA). These methods assign higher weights to more recent observations, making the smoothed series more reactive to new information [20].

Problem 4: I am dealing with one-sample-per-trial data (e.g., a single reaction time per trial) and binning is distorting the time-course.

- Potential Cause: Standard binning methods arbitrarily reduce temporal resolution and can misalign signals across subjects.

- Solution: Consider a method like SMART (Smoothing method for analysis of response time-course). This method uses temporal smoothing with a Gaussian kernel to reconstruct a high-resolution time-course, followed by weighted statistics and cluster-based permutation testing for robust inference [21].

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Smoothing Techniques

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for evaluating different smoothing algorithms on a noisy materials dataset.

1. Objective To systematically assess the performance of Bin Smoothing, Simple Moving Average, and Exponential Moving Average in recovering a known underlying trend from a synthetic noisy dataset.

2. Methodology Summary A known mathematical function (the "true" trend) will be contaminated with Gaussian noise to generate a synthetic dataset. Various smoothing techniques will be applied, and their performance will be quantified by how closely they approximate the original, noise-free trend.

3. Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Dataset | Provides a ground truth for validating smoothing methods. Generated from a known function (e.g., a sine wave or polynomial) with added random noise [16]. |

| Computational Environment | Software for calculation and visualization (e.g., Python with NumPy/SciPy/pandas, R, or MATLAB). |

| Smoothing Algorithms | The methods under test: Bin Means/Median, Simple Moving Average, Exponential Moving Average. |

| Error Metric Functions | Code to calculate performance metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). |

4. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1: Data Generation. Define a base function (e.g., ( f(x) = x + \sin(x) )) over a defined interval. Add random noise to the function's output to create your synthetic noisy dataset: ( Yi = f(xi) + \varepsilon_i ) [16].

- Step 2: Apply Smoothing Techniques.

- Bin Smoothing: Sort the data, distribute into an equal number of bins (e.g., 10 bins), and smooth by replacing values in each bin with the bin's mean or median [17].

- Simple Moving Average (SMA): Calculate the unweighted mean of the previous 'k' data points (e.g., k=5) for the entire series [18] [19].

- Exponential Moving Average (EMA): Calculate the weighted average that gives more importance to recent data. Start with an SMA and then apply the EMA formula with a defined multiplier [20].

- Step 3: Performance Quantification. For each smoothed curve, calculate the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) against the original, noise-free trend.

- Step 4: Visualization and Analysis. Plot the original trend, the noisy data, and all smoothed curves on a single graph. Create a bar chart comparing the MSE and MAE of the different methods.

Workflow and Decision-Making Visualizations

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for a smoothing analysis, from raw data to a final interpreted trend, incorporating key decision points.

Smoothing Analysis Workflow

This diagram helps researchers choose an appropriate smoothing method based on their data and assumptions.

Smoothing Method Decision Guide

A Practical Toolkit: From Classical Smoothing to Advanced Bayesian Optimization

This guide provides technical support for researchers applying classical smoothing techniques to noisy materials and pharmaceutical datasets. You will find troubleshooting guides, detailed experimental protocols, and key resources to help you effectively implement Exponential Smoothing and Holt-Winters methods to isolate underlying trends and seasonal patterns from noisy experimental data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my Simple Exponential Smoothing (SES) model underperforming, and how can I improve it?

SES performance heavily depends on the optimal selection of its smoothing parameter (alpha) and the initial value [22]. Underperformance is often due to suboptimal parameter choices.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Diagnose the Issue: Check if your data contains a trend or seasonality, which SES cannot model. Use time series decomposition to identify these components [23].

- Implement Optimization: Instead of using default parameters, employ an optimization algorithm to find the optimal alpha. A common practice is to use a cost function like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Mean Squared Error (MSE) and test a range of alpha values (e.g., from 0.01 to 0.99) [23].

- Advanced Hybrid Technique: For a robust solution, consider a hybrid approach like SES-Barnacles Mating Optimization (SES-BMO), which has been shown to simultaneously estimate the optimal initial value and smoothing parameter with high forecast accuracy [22].

Q2: How do I choose between the Additive and Multiplicative Holt-Winters methods?

The choice depends on the nature of the trend and seasonality in your data [24] [25].

- Decision Workflow:

- Plot Your Data: Visually inspect the time series plot.

- Analyze Seasonal Variation:

- Choose the Additive method if the seasonal variations are relatively constant throughout the series, meaning the peaks and troughs are roughly the same size regardless of the overall data level [25]. This is common in materials datasets with fixed seasonal effects.

- Choose the Multiplicative method if the seasonal variations change in proportion to the current level of the data. The oscillations will appear larger when the overall level of the series is higher and smaller when the level is lower [24] [25]. This is often observed in pharmaceutical sales data where seasonal peaks grow with overall market growth [25].

- Validate with Decomposition: Use time-series decomposition functions (e.g.,

seasonal_decomposein Python'sstatsmodels) to quantitatively confirm the nature of the components [23].

Q3: My data is very noisy with outliers. How should I pre-process it before smoothing?

Noise and outliers can significantly distort your model's forecasts.

- Pre-Processing Protocol:

- Identify Missing Data: Begin by identifying and addressing missing values. Common techniques include forward-filling or using the average of adjacent values, especially if the data exhibits trend or seasonality [23].

- Outlier Detection: Apply statistical tests to detect outliers. For high-uncertainty cases, the Grubbs' test is an effective method for outlier identification [24].

- Manage Outliers: Replace outlier values with more representative ones, such as the prediction of average sales per week, to prevent the data from being skewed downwards or upwards [24]. This is crucial for minimizing supply chain shortages in pharmaceutical research.

Q4: What are the best practices for validating my smoothing model on a limited dataset?

Traditional data splitting may not be suitable for small datasets or cases requiring immediate action.

- Validation Strategy:

- Avoid Standard Splits: The standard 80:20 or 75:25 train-test split is often unsuitable for small research datasets or urgent scenarios like a pandemic [22].

- Use Cross-Validation: Implement Repeated Time-Series Cross-Validation (RTS-CV). This technique involves repeatedly creating training and testing folds from the time series while preserving the temporal order of the data, providing a more reliable estimate of model accuracy [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hyperparameter Optimization for Simple Exponential Smoothing

This protocol outlines the steps to optimize the alpha parameter for an SES model using Python, as demonstrated in a CO2 concentration analysis [23].

Objective: To find the optimal smoothing parameter (alpha) that minimizes the forecast error.

Materials: Historical time-series data, Python environment with pandas, statsmodels, and sklearn libraries.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Split your data into training and test sets, ensuring the time series order is maintained [23].

- Define Parameter Grid: Create a range of potential alpha values (e.g.,

alphas = np.arange(0.01, 0.99, 0.01)). - Iterate and Fit: For each alpha value in the grid:

- Fit an SES model to the training data using the current alpha.

- Generate forecasts for the test set.

- Calculate a performance metric (e.g., MAE) between the forecasts and the actual test values.

- Select Optimal Parameter: Identify the alpha value that resulted in the lowest MAE.

- Final Model Fitting: Refit the SES model on the entire dataset using the optimized alpha for future predictions.

Protocol 2: Comparative Assessment of Holt-Winters and ARIMA

This protocol is derived from a supply chain analytics study comparing forecasting models for inventory optimization [26].

Objective: To compare the performance of Holt-Winters Exponential Smoothing (HWES) and Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) in forecasting demand. Materials: Real-world demand data with potential seasonality and trend.

Procedure:

- Model Implementation:

- HWES: Apply both additive and multiplicative Holt-Winters models to the data.

- ARIMA: Develop an ARIMA model, which involves identifying the appropriate order of differencing and the autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) parameters.

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate model performance under both stable and unstable economic conditions using error metrics such as RMSE, MAPE, and MAE [26] [27].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the models based on their ability to minimize lost sales and reduce stockouts. Studies have shown that ARIMA can consistently outperform HWES in certain scenarios, particularly under varying economic conditions [26].

Table 1: Summary of Exponential Smoothing Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Key Parameters | Best Suited For Data With... | Common Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Exponential Smoothing (SES) [22] [23] | Alpha (α) | A changing average, no trend or seasonality | Establishing a baseline for stable material properties |

| Holt's Linear Trend [27] [25] | Alpha (α), Beta (β) | A trend but no seasonality | Forecasting demand for drugs in growing therapeutic areas [25] |

| Holt-Winters Additive [24] [25] | Alpha (α), Beta (β), Gamma (γ) | Trend and additive seasonality | Modeling drug sales with fixed seasonal peaks (e.g., flu season) [25] |

| Holt-Winters Multiplicative [24] [25] | Alpha (α), Beta (β), Gamma (γ) | Trend and multiplicative seasonality | Modeling drug sales where seasonal effects grow with the data level [25] |

| Brown's Linear Exponential Smoothing [27] | Alpha (α) | A linear trend | Forecasting metal spot prices in economic research [27] |

Table 2: Quantitative Forecast Accuracy from Cited Literature

| Study Context | Model(s) Used | Key Performance Metric(s) | Reported Accuracy/Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Forecasting [22] | SES-Barnacles Mating Optimization (SES-BMO) | Forecast Accuracy | Average 8-day accuracy: 90.2% (Range: 83.7% - 98.8%) |

| Metal Price Forecasting [27] | Holt, Brown, Damped Methods | RMSE, MAPE, MAE | Model performance varied by metal; best-fitted models used for forecasting up to 2030. |

| Supply Chain Inventory [26] | HWES vs. ARIMA | Lost Sales Mitigation | ARIMA consistently outperformed HWES in minimizing lost sales, especially in unstable conditions. |

| Pharmaceutical Retail [24] | Multiple Exponential Smoothing Methods | Theil's U2 Test | Forecasting on individual pharmacy levels leads to higher accuracy than aggregated chain-level forecasts. |

Method Selection and Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for selecting the appropriate classical smoothing technique based on the characteristics of your dataset.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Data Resources for Time-Series Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Monash Forecasting Repository [28] | A comprehensive archive of time series datasets for benchmarking forecasting models. | Includes datasets from domains like energy, sales, and transportation. |

| Statsmodels Library (Python) [23] | A Python module providing classes and functions for implementing SES, Holt, and Holt-Winters. | Used for model fitting, parameter optimization, and forecasting. |

| Grubbs' Test [24] | A statistical test used to detect a single outlier in a univariate dataset. | Critical for pre-processing noisy experimental data. |

| Repeated Time-Series Cross-Validation (RTS-CV) [22] | A model validation technique for assessing how a model will generalize to an independent data set. | Preferred over simple train-test splits for limited data. |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [23] | A metric used to evaluate forecast accuracy; it is the average absolute difference between forecasts and actuals. | Easy to interpret and less sensitive to outliers than RMSE. |

Local Weighted Regression (LOESS) for Flexible, Non-Linear Trends

Local Weighted Regression, commonly known as LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) or LOWESS (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing), is a powerful non-parametric technique for fitting a smooth curve to noisy data points. Unlike traditional linear or polynomial regression that fits a single global model, LOESS creates a point-wise fit by applying multiple regression models to localized subsets of your data [29] [30]. This makes it exceptionally valuable for materials science research where you often encounter complex, non-linear relationships in datasets without a known theoretical model to describe them.

The core strength of LOESS lies in its ability to "allow the data to speak for themselves" [31]. For researchers analyzing materials datasets—whether studying phase transitions, property-composition relationships, or degradation profiles—this flexibility is crucial. The technique helps reveal underlying patterns and trends that might be obscured by experimental noise or complex material behaviors, without requiring prior specification of a global functional form [29].

Key Parameters and Configuration

Understanding Critical Parameters

Successful implementation of LOESS requires appropriate configuration of its key parameters, which control the smoothness and flexibility of the resulting curve. The table below summarizes these essential parameters:

| Parameter | Function | Typical Settings | Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Span (α) | Controls the proportion of data used in each local regression. | 0.25 to 0.75 | Lower values capture more detail (noisier); higher values create smoother trends. |

| Degree | Sets the polynomial degree for local fits. | 1 (Linear) or 2 (Quadratic) | Degree 1 is flexible; Degree 2 captures more complex curvature. |

| Weight Function (e.g., Tri-cubic) | Assigns weights to neighbors based on distance [30]. | W(u) = (1-|u|³)³ for |u|<1 |

Gives more influence to closer points. |

| Family | Determines the error distribution and fitting method. | "Gaussian" or "Symmetric" | "Symmetric" is more robust to outliers in the dataset. |

Parameter Selection Guidelines

Choosing the right parameters is often an iterative process that depends on your specific dataset and research goals. For initial exploration in materials research, start with a span of 0.5 and degree 1. If you need to capture more curvature in your data, increase the degree to 2. If the resulting curve appears too wiggly, increase the span; if it seems to overlook important features, decrease the span [31] [32].

Experimental Protocol and Implementation

Step-by-Step LOESS Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for applying LOESS smoothing to a materials dataset:

Detailed Methodology

Data Preparation: Begin by normalizing your predictor variable (e.g., time, temperature, concentration) to a common scale, typically between 0 and 1. This prevents numerical instability and ensures the distance calculations are meaningful [30].

Parameter Selection: Based on your data characteristics and research questions, select initial values for span and degree as discussed in Section 2.2.

Local Regression Execution: For each point

xᵢin your dataset (or at the specific prediction points you desire):- Identify Neighborhood: Find the

k = span * nnearest neighbors toxᵢbased on Euclidean distance, wherenis the total number of data points. - Calculate Weights: Assign a weight to each neighbor using the tri-cubic weight function [30]:

wⱼ = (1 - (|xⱼ - xᵢ| / d_max)³)³for all|xⱼ - xᵢ| < d_max, whered_maxis the distance to thek-th neighbor. - Perform Local Fit: Execute a weighted least squares regression within this neighborhood using the specified degree (1 or 2). The regression model for degree 1 is:

y ≈ β₀ + β₁(x - xᵢ). - Store Result: The fitted value at

xᵢ(ŷᵢ) is the interceptβ₀of this local model [29] [30].

- Identify Neighborhood: Find the

Output and Visualization: Plot the resulting

(xᵢ, ŷᵢ)pairs to visualize the smoothed trend, often overlaying it on the original scatter plot to assess fit quality.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details the essential computational "reagents" needed to implement LOESS in a materials research context:

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

R with loess() |

Primary LOESS implementation with easy parameter tuning [32]. | General materials data analysis, exploratory work. |

| Python with StatsModels | statsmodels.nonparametric.lowess or custom implementation [30]. |

Integration into larger Python-based analysis pipelines. |

| Tri-cubic Kernel | Weight function for local regression [30]. | Assigning influence to neighboring data points. |

| Weighted Least Squares Solver | Core algorithm for local polynomial fits. | Solving the local regression problems at each point. |

Troubleshooting and FAQ

Q1: My LOESS curve appears too wiggly and follows the noise. How can I achieve a smoother trend? A1: Increase the span parameter. A larger span includes more data points in each local regression, creating a smoother result that is less sensitive to local variations and noise [31] [32].

Q2: The LOESS fit misses important peaks (troughs) in my experimental data. What should I adjust? A2: First, try decreasing the span to make the fit more sensitive to local variations. If that doesn't work, switch from degree=1 (linear) to degree=2 (quadratic), as the quadratic model is better at capturing curvature and extrema [32].

Q3: The computation is very slow with my large materials dataset. Are there optimization strategies? A3: For very large datasets, consider these approaches: (1) Use a smaller span to reduce the neighborhood size for each calculation; (2) Fit the curve at a subset of evenly-spaced points and interpolate; (3) Ensure your implementation uses efficient, vectorized operations, as seen in optimized Python code using NumPy [30].

Q4: How can I determine if my LOESS fit is reliable and not introducing artificial patterns? A4: Examine the residuals (observed minus fitted values). They should be randomly scattered without systematic patterns. Additionally, perform sensitivity analysis by varying the span parameter slightly—a robust fit should not change dramatically with small parameter adjustments [31]. Strong, spurious cross-correlations can emerge if the smoothing is either too harsh or too lenient [33].

Q5: My data contains significant outliers from instrument artifacts. Is LOESS appropriate? A5: Yes, but use the family="symmetric" option if available. This implements a robust fitting procedure that iteratively reduces the weight of outliers, making the fit less sensitive to anomalous data points [32].

Kalman Filters for Dynamic State Estimation and Noise Reduction

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Filter Divergence and Instability

Problem: The filter estimate diverges from the true state, or the estimated covariance matrix becomes unrealistically small.

Step 1: Verify Initial Conditions

- Action: Check the initial state estimate (

x0) and error covariance (P0).P0should not be zero unless the initial state is known with absolute certainty. - Rationale: A zero

P0prevents the filter from correcting itself with new measurements, leading to divergence [34].

- Action: Check the initial state estimate (

Step 2: Inspect Process and Measurement Noise Covariances

- Action: Tune the Process Noise Covariance (

Q) and Measurement Noise Covariance (R). IncreaseQif the model is too rigid and cannot track the true dynamics; increaseRif the filter is overly trusting noisy measurements [35]. - Rationale:

QandRbalance trust between the model prediction and the sensor measurements [36] [35].

- Action: Tune the Process Noise Covariance (

Step 3: Check System Observability

- Action: Ensure your system is observable by confirming the observability matrix has full rank.

- Rationale: If states are not observable from the given measurements, the filter cannot estimate them correctly.

Guide 2: Handling Non-Gaussian Noise and Outliers

Problem: Severe performance degradation occurs due to non-Gaussian noise or outlier measurements in materials data.

Step 1: Identify Outliers

- Action: Monitor the innovation sequence (difference between predicted and actual measurements). A sudden, large innovation may indicate an outlier [37].

- Rationale: The innovation is the direct measure of new information from the measurement.

Step 2: Implement Robust Filtering Techniques

- Action: Replace the standard Kalman Filter update with a robust formulation. For example, integrate a robust function based on the maximum exponential absolute value into the update step to reduce the influence of outliers [37].

- Rationale: Standard Kalman Filters assume Gaussian noise and are highly sensitive to outliers [37].

Step 3: Consider Advanced Nonlinear Filters

- Action: For strongly nonlinear systems with non-Gaussian noise, use filters like the Cubature Kalman Filter (CKF) or Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) with robust modifications [37] [38].

- Rationale: These filters better handle nonlinearities and can be adapted with robust cost functions to mitigate outlier effects [37].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose the right Kalman Filter variant for my materials dataset?

- A: The choice depends on the linearity of your system and the nature of the noise.

- Use the Classical Kalman Filter for linear systems with Gaussian noise.

- Use the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) for mildly nonlinear systems; it linearizes the model around the current estimate.

- Use the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) or Cubature Kalman Filter (CKF) for highly nonlinear systems, as they provide better accuracy than the EKF without the need to compute Jacobians [37] [38].

Q2: My parameter estimation converges to wrong values. What could be the cause?

- A: This is often caused by inappropriate initial guesses for the parameters or incorrectly specified noise covariances.

- Solution: Perform a preliminary analysis, such as a mean square error comparison, to select better initial parameters. Carefully tune the

QandRmatrices, as an assumedQof zero can slow convergence and lead to false local minima [34].

- Solution: Perform a preliminary analysis, such as a mean square error comparison, to select better initial parameters. Carefully tune the

Q3: Can I use a Kalman Filter with only output measurements (no known inputs) for my system?

- A: Yes. The Augmented Kalman Filter (AKF) is a specific approach designed for simultaneous estimation of the system's states and the unknown input forces acting upon it, which is common in structural dynamics and health monitoring [36].

Q4: How can I validate that my Kalman Filter is implemented correctly?

- A: A key method is consistency validation.

- Check Innovation Sequence: The innovation should be a white noise sequence with zero mean and covariance matching the filter's calculated innovation covariance.

- Compare Discrete and Continuous: If applicable, compare the results of a Discrete Kalman Filter (DKF) with its continuous-time counterpart (CKF) to assure correctness of the implementation [39].

Experimental Protocols for Materials Research

Protocol 1: Determining Material Parameters from Noisy Data

Objective: To accurately identify material parameters (e.g., diffusion coefficients, viscoplastic properties) from uncertain experimental measurements [34].

System Modeling:

- Define the state vector

xto include the material parameters to be estimated. - Formulate the process model. Often, parameters are assumed constant, so the state transition is an identity matrix:

x_k = x_{k-1} + w_k, wherew_kis process noise. - Formulate the measurement model

z_k = h(x_k) + v_k, wherehis a (often nonlinear) function that predicts the measurement based on the current parameters.

- Define the state vector

Filter Initialization:

- Initial State (

x0): Use a mean square error analysis against generated or prior data to select appropriate initial parameter values to avoid false local attractors [34]. - Initial Covariance (

P0): Set to reflect confidence in the initial guess. A diagonal matrix with large values indicates high uncertainty. - Noise Covariances (

QandR):Qcan be set to a small value or zero if parameters are assumed constant.Ris typically set as a small percentage of the measured data variance or based on sensor accuracy [34].

- Initial State (

Execution:

- For each new measurement

z_k, perform the Kalman Filter prediction and update cycle. - The update step will adjust the parameter estimates to minimize the difference between the model prediction

h(x_k)and the actual measurementz_k.

- For each new measurement

Protocol 2: Smoothing Noisy Sensor Data for State Estimation

Objective: To obtain a smooth, real-time estimate of a dynamic state (e.g., position, temperature, strain) from noisy sensor streams in a materials testing environment [40] [35].

State Definition:

- Define a state vector that includes the primary variable of interest and its rate of change (e.g.,

x = [position; velocity]orx = [temperature; temperature_rate]).

- Define a state vector that includes the primary variable of interest and its rate of change (e.g.,

Model Definition:

- Process Model: Use a constant-velocity or constant-acceleration model to predict state evolution. For example, with a constant-velocity model, the state transition matrix

Fis: - Measurement Model: Define how the state maps to the sensor reading. If the sensor measures only position, the measurement matrix

His[1, 0].

- Process Model: Use a constant-velocity or constant-acceleration model to predict state evolution. For example, with a constant-velocity model, the state transition matrix

Filter Tuning:

- Process Noise (

Q): Model asG * Q_base * G', whereGis a matrix related to the integration of noise into the state [40]. TuneQ_baseto reflect uncertainty in the motion model. Low values make the filter smoother but less responsive to changes. - Measurement Noise (

R): Set based on the known variance of the sensor. Higher values make the filter trust the sensor less, leading to a smoother output [35].

- Process Noise (

Real-time Processing:

- For each new sensor reading, execute the

predictandupdatesteps. The updated state estimatexprovides a smoothed value of the tracked variable.

- For each new sensor reading, execute the

Table 1: Kalman Filter Variants and Their Applicability

| Filter Variant | System Linearity | Noise Assumption | Key Strengths | Common Use Cases in Materials Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical KF [41] [39] | Linear | Gaussian | Optimal for linear systems, computationally efficient. | Linear system identification, sensor fusion. |

| Extended KF (EKF) [42] [38] | Mildly Nonlinear | Gaussian | Handles nonlinearities via local linearization. | Power system state estimation [42], parameter identification. |

| Unscented KF (UKF) [37] [38] | Highly Nonlinear | Gaussian | Better accuracy than EKF for strong nonlinearities, no Jacobian needed. | Ship state estimation [38], estimation of hydrodynamic forces. |

| Cubature KF (CKF) [37] | Highly Nonlinear | Gaussian | Similar to UKF, based on spherical-radial cubature rule. | Power system dynamic state estimation, robust to non-Gaussian noise when modified [37]. |

| Augmented KF (AKF) [36] | Linear | Gaussian | Simultaneously estimates system states and unmeasured inputs. | Virtual sensing, input-state estimation in structural dynamics [36]. |

Table 2: Tuning Parameters and Their Impact on Filter Behavior

| Parameter | Description | Effect of Increasing the Parameter | Guideline for Materials Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Noise (Q) [36] [35] | Uncertainty in the system process model. | Filter becomes more responsive to measurements; estimates may become noisier. | Increase if the material's dynamic response is not perfectly modeled. |

| Measurement Noise (R) [34] [35] | Uncertainty in sensor measurements. | Filter trusts measurements less; estimates become smoother but may lag true changes. | Set based on sensor manufacturer's accuracy specifications or calculate from static data. |

| Initial Estimate (x0) [34] | Initial guess for the state vector. | Affects convergence speed and can lead to divergence if poorly chosen. | Use a mean square error approach with prior data to select a good initial value [34]. |

| Initial Covariance (P0) [34] | Confidence in the initial state guess. | High values allow the filter to quickly adjust initial state; low values can cause divergence. | Use large values if the initial state is unknown. |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Components for Kalman Filtering

| Component / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| State Vector (x) [40] [37] | Contains all variables to be estimated (e.g., material parameters, position, velocity). | For parameter estimation, the vector contains the parameters. For dynamic estimation, it includes the variable and its derivatives. |

| Covariance Matrix (P) [35] | Represents the estimated uncertainty of the state vector. | A diagonal matrix indicates uncorrelated state variables. Must be positive semi-definite. |

| State Transition Model (F) [40] [43] | Describes how the state evolves from one time step to the next without external input. | For constant parameters, this is an identity matrix. For dynamic states, it encodes the physics (e.g., constant velocity). |

| Process Noise Covariance (Q) [36] [35] | Models the uncertainty in the state transition process. | A critical tuning parameter. Often modeled as G * Q_base * Gᵀ where G is a noise gain matrix [40]. |

| Measurement Noise Covariance (R) [34] [35] | Models the uncertainty of the sensors taking the measurements. | Can be measured experimentally by calculating the variance of a static sensor signal. |

| Measurement Matrix (H) [40] | Maps the state vector to the expected measurement. | If measuring the first element of the state vector directly, H = [1, 0, ..., 0]. |

| Innovation (ỹ) [35] [37] | The difference between the actual and predicted measurement. | Monitoring this sequence is key to filter validation and outlier detection. |

| Kalman Gain (K) [41] [35] | The optimal weighting factor that balances prediction and measurement. | Determined by the relative magnitudes of P (prediction uncertainty) and R (measurement uncertainty). |

Model-Based Smoothing with Sequential Monte Carlo (Particle Filtering)

In materials science research, accurately interpreting data from experiments such as spectroscopy, chromatography, or tensile testing is paramount. These datasets are often contaminated by significant noise, obscuring the underlying material properties and behaviors. Model-Based Smoothing with Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC), particularly Particle Filtering, provides a robust probabilistic framework for extracting clean signals from this noisy data. This technical support center addresses the specific implementation challenges researchers face when applying these sophisticated algorithms to materials datasets, enabling more precise analysis of drug dissolution profiles, polymer degradation, and other critical phenomena.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using a particle filter for smoothing my materials data over traditional Kalman filters?

Particle filters are a class of Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) methods designed for non-linear and non-Gaussian state-space models. Unlike Kalman filters, which are optimal only for linear Gaussian models, particle filters approximate the posterior distribution of latent states (e.g., the true signal) given noisy observations using a set of weighted random samples, called particles. This makes them exceptionally suitable for the complex, often non-linear, degradation or reaction dynamics common in materials science [44] [45].

FAQ 2: My particle filter produces erratic estimates. Why does this happen, and how can I achieve smoother outputs?

Erratic estimates are often a symptom of weight degeneracy, a common issue in SMC where after a few iterations, all but one particle carries negligible weight. To achieve proper smoothing and stable estimates:

- Increase the Number of Particles: Use more particles, though this increases computational cost [44].

- Implement Resampling: Systematically resample particles to discard those with low weights and replicate high-weight particles. Use criteria like Effective Sample Size (ESS) to trigger resampling (e.g., when ESS drops below half the total particles) [44] [46].

- Employ a Proper Smoothing Algorithm: Standard particle filters are for filtering (p(ϕt|y1:t)). For smoothing (p(ϕ1:T|y1:T)), which uses the entire dataset for each estimate, you need specific smoothing techniques that retrospectively analyze the entire particle trajectory [44].

FAQ 3: I received an error that "particle filtering requires measurement error on the observables." What does this mean?

This error arises because the particle filter algorithm relies on the concept of an "emission model" or "measurement model," which defines the probability of an observation given the current state (p(ot|xt)). This model inherently accounts for measurement error. If your model is defined without this stochasticity (implying perfect, noiseless measurements), the particle update step becomes invalid. You must incorporate a measurement error term into your observational model, for example, by assuming your observations are normally distributed around the true state with a certain variance [47] [45].

FAQ 4: How can I set the color of nodes and edges in my Graphviz workflow diagrams using precise hex codes?

The Graphviz Python package and DOT language allow you to specify colors using hexadecimal codes. Instead of using named colors like 'green', you can use a hex string prefixed with a #. For example, to color a node with Google Blue, use color='#4285F4' and fillcolor='#4285F4' [48] [49]. It is critical to also set the fontcolor attribute to ensure text has high contrast against the node's fill color (e.g., white text on dark colors, black text on light colors) [50].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Weight Degeneracy in Long-Running Experiments

Symptoms: After processing a number of time steps (e.g., data points from a long-term materials degradation study), the estimated state becomes unstable and variance increases dramatically. Diagnostics reveal that the effective sample size (ESS) has collapsed.

Diagnosis: This is a classic case of weight degeneracy, where the particle set loses its ability to represent the posterior distribution effectively [44].

Resolution:

- Integrate Systematic Resampling: Replace the multinomial resampling step with more advanced schemes like systematic or stratified resampling to improve particle diversity [44].

- Adopt a Resampling Threshold: Implement an adaptive resampling strategy. Resample only when the ESS falls below a predefined threshold (e.g.,

N/2, whereNis the total number of particles). This prevents unnecessary resampling which can itself reduce diversity [46]. - Consider Particle Smoothing: For offline analysis, use a fixed-interval smoother like the forward-filtering backward-smoothing (FFBS) algorithm. This algorithm refines state estimates by processing the data both forwards and backwards, leading to significantly smoother and more accurate trajectories than the forward-pass filter alone [44].

Issue 2: Inaccurate State Estimation Despite High Particle Count

Symptoms: The smoothed output consistently deviates from known benchmarks or fails to capture key dynamic features, even when using a large number of particles.

Diagnosis: The problem likely lies in the model definition, either in the state transition dynamics or the observation model, causing the particles to explore the wrong regions of the state space [45].

Resolution:

- Refine the Process Model: Re-evaluate the mathematical model describing how your material's state evolves. For instance, a first-order degradation model might be insufficient; a second-order or autocatalytic model might be more appropriate. A more accurate process model guides particles more effectively.

- Calibrate the Observation Model: Ensure the statistical distribution of your measurement noise (e.g., Gaussian, Log-Normal) and its variance are correctly specified. You can estimate these parameters from controlled calibration experiments.

- Tune Proposal Distribution: In advanced implementations, use a custom proposal distribution that takes into account the most recent observation to generate more informative particles, rather than relying solely on the state transition model [46].

Issue 3: Implementation Error with Measurement Model

Symptoms: The code throws a specific error about missing measurement errors, or the filter fails to update particle weights when new data arrives [47].

Diagnosis: The emission model, p(oₜ | xₜ), is either missing, incorrectly implemented, or does not represent a valid probability distribution.

Resolution:

- Define the Emission Model: Explicitly define a function that calculates the probability (or probability density) of the observed data point given a particle's state. For a continuous measurement, this is often a Normal distribution:

observation_probability = norm.pdf(observed_value, loc=particle_state, scale=measurement_std). - Verify Model Structure: In state-space model terms, confirm your implementation correctly calculates the emission probability for each particle during the weight update step:

w_t(i) ∝ w_{t-1}(i) * p(o_t | x_t(i))[45]. - Incorporate Model Error: For materials models with significant uncertainty, consider adding a "model error" or "discrepancy" term to the state transition model to account for the fact that the mathematical model is itself an imperfect representation of reality.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Basic Particle Filter for Signal Smoothing

This protocol outlines the core steps for implementing a basic particle filter to smooth a one-dimensional noisy signal from a materials dataset (e.g., from a UV-Vis spectrometer).

1. Problem Definition:

- State (xₜ): The true, underlying value of the signal (e.g., actual concentration, stress).

- Observation (oₜ): The measured, noisy value.

- State Transition Model (p(xₜ | xₜ₋₁)): A model for how the state evolves. For a slowly varying signal, this could be a random walk:

xₜ = xₜ₋₁ + εₜ, whereεₜ ~ N(0, σ_process). - Emission Model (p(oₜ | xₜ)): A model for the measurements. Often:

oₜ ~ N(xₜ, σ_measure).

2. Algorithm Workflow:

3. Quantitative Parameters: The following table summarizes key parameters and their typical roles in the algorithm [44] [46].

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in Algorithm | Typical Value / Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|