Reinforcement Learning for Molecular Design Optimization: Advanced Methods and Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Reinforcement Learning (RL) applications in molecular design optimization, a transformative approach in modern drug discovery. It covers the foundational principles of framing molecular modification as a Markov Decision Process and ensuring chemical validity. The review details key methodological architectures, including transformer-based models, Deep Q-Networks, and diffusion models, integrated within frameworks like REINVENT for multi-parameter optimization. It critically addresses central challenges such as sparse rewards and mode collapse, presenting solutions like experience replay and uncertainty-aware learning. Finally, the article examines validation strategies, from benchmark performance and docking studies to experimental confirmation, highlighting how RL accelerates the discovery of novel, optimized bioactive compounds for targets like DRD2 and EGFR.

Reinforcement Learning for Molecular Design Optimization: Advanced Methods and Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Reinforcement Learning (RL) applications in molecular design optimization, a transformative approach in modern drug discovery. It covers the foundational principles of framing molecular modification as a Markov Decision Process and ensuring chemical validity. The review details key methodological architectures, including transformer-based models, Deep Q-Networks, and diffusion models, integrated within frameworks like REINVENT for multi-parameter optimization. It critically addresses central challenges such as sparse rewards and mode collapse, presenting solutions like experience replay and uncertainty-aware learning. Finally, the article examines validation strategies, from benchmark performance and docking studies to experimental confirmation, highlighting how RL accelerates the discovery of novel, optimized bioactive compounds for targets like DRD2 and EGFR.

The Foundations of RL in Molecular Design: From Chemical Space to Markov Decision Processes

Framing Molecular Modification as a Markov Decision Process (MDP)

The design and optimization of novel molecular structures with desirable properties represents a fundamental challenge in material science and drug discovery. The traditional process is often time-consuming and expensive, potentially taking years and costing millions of dollars to bring a new drug to market [1]. In recent years, reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful framework for automating and accelerating molecular design. Central to this approach is the formalization of molecular modification as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which provides a rigorous mathematical foundation for sequential decision-making under uncertainty [2]. This application note details how molecular optimization can be framed as an MDP, provides experimental protocols for implementation, and presents key resources for researchers pursuing RL-driven molecular design.

Molecular Modification as an MDP

A Markov Decision Process is defined by the tuple (S, A, P, R), where S represents the state space, A the action space, P the state transition probabilities, and R the reward function [2]. In the context of molecular optimization:

- State Space (S): Each state s ∈ S is a tuple (m, t), where m represents a valid molecular structure and t denotes the number of modification steps taken. The initial state typically begins with a specific starting molecule or nothing at t=0 [1].

- Action Space (A): The action space consists of chemically valid modifications that can be applied to a molecule. These are categorized into three fundamental operations [1]:

- Atom Addition: Adding an atom from a defined set of elements (e.g., C, O, N) and forming a valence-allowed bond between this new atom and the existing molecule.

- Bond Addition: Increasing the bond order between two atoms with free valence (e.g., no bond → single bond, single bond → double bond).

- Bond Removal: Decreasing the bond order between two atoms (e.g., triple bond → double bond, single bond → no bond).

- Transition Dynamics (P): The state transition probability P(s′|s,a) defines the probability of reaching state s′ after taking action a in state s. In most molecular MDP frameworks, these transitions are deterministic—applying a specific modification to a molecule reliably produces a single, predictable resulting molecule [1].

- Reward Function (R): The reward R(s) guides the optimization process and is typically based on one or more computed properties of the molecule m at state s. To prioritize final outcomes while encouraging progressive improvement, rewards are often assigned at each step but discounted by a factor γ^(T-t), where T is the maximum number of steps allowed [1].

Experimental Protocol & Workflow

The following section outlines a practical protocol for implementing an MDP-based molecular optimization pipeline, from environment setup to model training and validation.

MDP Environment Setup

- Define the Chemical Action Space: Using a cheminformatics library (e.g., RDKit), enumerate all allowed atom types (e.g., C, N, O, S) and bond types (single, double, triple). Crucially, implement valence checks to filter out chemically impossible actions, ensuring 100% validity of generated molecules [1].

- Implement the State Representation: Develop a function that encodes the current molecule and step count into a state representation. Common approaches include using molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints), graph representations, or SMILES strings [3].

- Specify the Reward Function: Program the reward function based on target properties. This can be a single objective (e.g., DRD2 activity) or a weighted combination of multiple objectives (e.g., bioactivity, drug-likeness QED, synthetic accessibility) [3].

Agent Training with Reinforcement Learning

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a suitable RL algorithm. Value-based methods like Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and its variants (e.g., Double DQN) have been successfully applied (e.g., in the MolDQN framework) and are known for stability [1]. Policy-based methods can also be used.

- Initialize the Agent: The policy network can be initialized randomly or pre-trained. Pre-training on a large corpus of molecules (e.g., from PubChem or ChEMBL) can teach the model the underlying rules of chemical validity and provide a strong starting point [3].

- Run the Training Loop: For a set number of episodes or until convergence:

- Start from an initial molecule.

- The agent selects an action (chemical modification) based on its current policy.

- The environment applies the action, transitions to a new state (molecule), and returns a reward.

- The agent updates its policy using the collected experience (state, action, reward, next state).

The workflow below illustrates the core cycle of interaction between the agent and the chemical environment:

Multi-Objective Optimization

Real-world molecular optimization often requires balancing multiple, potentially competing properties. This can be achieved through multi-objective reinforcement learning, where the reward function R(s) is defined as a weighted sum of individual property scores [1]:

R(s) = wâ‚ * Propâ‚(m) + wâ‚‚ * Propâ‚‚(m) + ... + wâ‚™ * Propâ‚™(m)

Researchers can adjust the weights wáµ¢ to reflect the relative importance of each objective, such as maximizing drug-likeness (QED) while maintaining sufficient similarity to a lead compound.

Performance Metrics & Benchmarking

To evaluate the performance of an MDP-based molecular optimization model, it is essential to track relevant metrics over the course of training and compare against established baselines. The following table summarizes key quantitative indicators:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Molecular Optimization MDPs

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description | Target Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Performance | Success Rate [3] | Percentage of generated molecules that achieve a target property profile. | >20-80% (varies by task difficulty) |

| Property Improvement [3] | Average increase in a key property (e.g., DRD2 activity) from starting molecule. | Maximize | |

| Sample Quality | Validity [1] | Percentage of generated molecular structures that are chemically valid. | 100% |

| Uniqueness [3] | Percentage of generated valid molecules that are non-duplicate. | >80% | |

| Novelty [3] | Percentage of generated molecules not found in the training set. | >70% | |

| Diversity | Structural Diversity | Average pairwise Tanimoto dissimilarity or scaffold diversity of generated molecules. | Maximize |

The impact of different training strategies is evident in benchmark studies. For instance, fine-tuning a pre-trained transformer model with RL for DRD2 activity optimization significantly outperforms the base model, as shown in the sample results below:

Table 2: Sample Benchmark Results for DRD2 Optimization via RL (Adapted from [3])

| Starting Molecule | Model | Success Rate (%) | Avg. P(active) | Notable Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound A (P=0.51) | Transformer (Baseline) | ~22% | 0.61 | Limited improvement |

| Transformer + RL | ~82% | 0.82 | Major activity boost | |

| Compound B (P=0.67) | Transformer (Baseline) | ~43% | 0.73 | Moderate improvement |

| Transformer + RL | ~79% | 0.85 | High activity achieved |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Implementing an MDP framework for molecular optimization requires a combination of software tools, chemical data, and computational resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for MDP-based Molecular Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [4] | Software Suite | Molecular dynamics simulation. | Can be used for in-silico validation of optimized molecules' stability (post-generation). |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical information manipulation. | Core component for state representation (fingerprints, graphs), action validation, and molecule handling [3]. |

| REINVENT [3] | RL Framework | Molecular design and optimization. | Provides a ready-made RL scaffolding to train and fine-tune generative models (e.g., Transformers) for property optimization. |

| ChEMBL/PubChem [3] | Chemical Database | Repository of bioactive molecules and properties. | Source of initial structures for training and benchmarking; defines the feasible chemical space. |

| Transformer Models [3] | Deep Learning Architecture | Sequence generation and translation. | Acts as the policy network in the MDP; can be pre-trained on molecular databases (e.g., PubChem) to learn chemical grammar. |

| Zasocitinib | Zasocitinib, CAS:2272904-53-5, MF:C23H24N8O3, MW:460.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SID 26681509 | SID 26681509, MF:C27H33N5O5S, MW:539.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced MDP Integration and Workflow

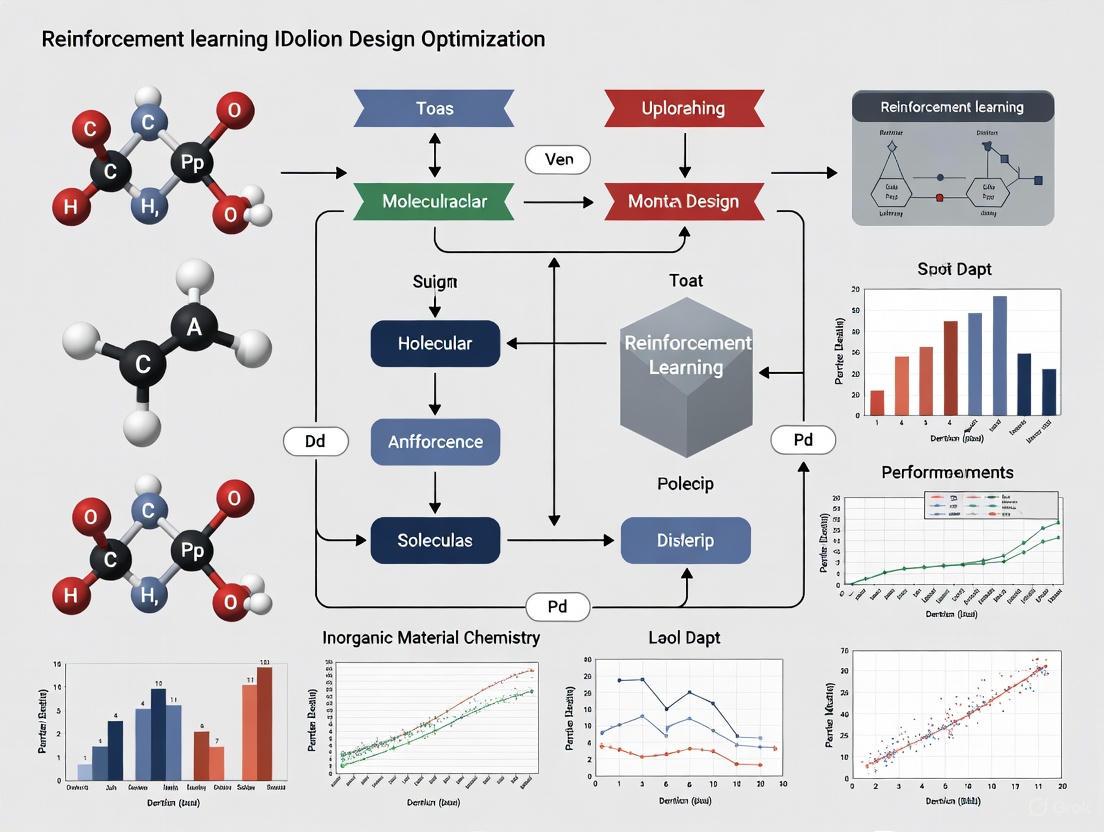

For advanced implementations, the MDP-based molecular optimizer can be integrated into a larger, iterative discovery pipeline. The following diagram depicts this comprehensive workflow, from the initial MDP setup to final candidate selection, highlighting how the core MDP interacts with other critical components like pre-training and external validation:

This integrated workflow, as exemplified by frameworks like REINVENT, shows how a prior model (pre-trained on general chemical space) is fine-tuned via RL. The scoring function incorporates multiple objectives, and the diversity filter helps prevent mode collapse, ensuring the generation of a wide range of high-quality candidate molecules [3].

In reinforcement learning (RL)-driven molecular design, the core action space defines the set of fundamental operations an agent can perform to structurally alter a molecule. The choice of action space is pivotal, as it directly controls the model's ability to navigate chemical space, the chemical validity of proposed structures, and the efficiency of optimization for desired properties. The principal action categories are atom addition, bond modification (which includes addition and removal), and actions governed by validity constraints to ensure chemically plausible structures. These action spaces can be implemented on various molecular representations, including molecular graphs and SMILES strings, each with distinct trade-offs between flexibility, validity assurance, and exploration capability. This note details the implementation, protocols, and practical considerations for employing these core action spaces within RL frameworks for molecular optimization, providing a guide for researchers and development professionals in drug discovery.

Defining the Core Action Spaces

The action space in molecular RL can be structured around three fundamental modification types. The following table summarizes their definitions, valid actions, and primary constraints.

Table 1: Definition and Scope of Core Action Spaces

| Action Space | Definition | Valid Action Examples | Key Validity Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Addition | Adding a new atom from a predefined set of elements and connecting it to the existing molecular graph. | - Add a carbon atom with a single bond.- Add an oxygen atom with a double bond. [1] | - New atom replaces an implicit hydrogen. [1]- Valence of the existing atom must not be exceeded. |

| Bond Modification | Altering the bond order between two existing atoms. This includes Bond Addition (increasing order) and Bond Removal (decreasing order). [1] | - No bond → Single/Double/Triple bond.- Single bond → Double/Triple bond.- Double bond → Triple bond.- Triple bond → Double/Single/No bond. [1] | - Bond formation may be restricted between atoms in rings to prevent high strain. [1]- Removal that creates disconnected fragments is handled by removing lone atoms. [1] |

| Validity Constraints | A set of rules that filter the action space to only permit chemically plausible molecules. | - Allowing only valence-allowed bond orders. [1]- Explicitly forbidding breaking of aromatic bonds. [1] | - Octet rule (valence constraints).- Structural stability rules (e.g., ring strain).- Syntactic validity for SMILES strings. [5] |

The dot code block below defines a workflow that integrates these action spaces into a coherent Markov Decision Process (MDP) for molecular optimization.

Molecular Optimization MDP

This diagram illustrates the sequential decision-making process in molecular optimization. The agent iteratively modifies a molecule by selecting valid actions from the core action spaces, guided by chemical constraints to ensure the generation of realistic structures. The reward signal, computed based on the properties of the new molecule, is used to update the agent's policy.

Quantitative Comparison of RL Approaches and Action Spaces

Different RL frameworks utilize the core action spaces with varying strategies for ensuring validity and optimizing properties. The table below synthesizes quantitative findings and key features from recent methodologies.

Table 2: Performance and Features of Molecular RL Approaches

| Model / Framework | Core Action Space | Key Innovation | Reported Performance | Validity Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolDQN [1] | Graph-based: Atom addition, Bond addition/removal. [1] | Combines Double Q-learning with chemically valid MDP; no pre-training. [1] | Comparable or superior on benchmark tasks (e.g., penalized LogP). [1] | 100% (invalid actions disallowed) [1] |

| GraphXForm [6] | Graph-based: Sequential addition of atoms and bonds. | Decoder-only graph transformer; combines CE method and self-improvement learning for fine-tuning. [6] | Superior objective scores on GuacaMol benchmarks and solvent design tasks. [6] | Inherent from graph representation. [6] |

| MOLRL [7] | Latent space: Continuous optimization via PPO. | PPO for optimization in the latent space of a pre-trained autoencoder. [7] | Comparable or superior on single/multi-property and scaffold-constrained tasks. [7] | >99% (depends on pre-trained decoder) [7] |

| PSV-PPO [5] | SMILES-based: Token-by-token generation. | Partial SMILES validation at each generation step to prevent invalid sequences. [5] | Maintains high validity during RL; competitive on PMO/GuacaMol. [5] | Significantly higher than baseline PPO. [5] |

| REINVENT [3] | SMILES-based: Token-by-token generation. | Uses a pre-trained "prior" model to anchor RL and prevent catastrophic forgetting. [3] | Effectively steers generation in scaffold discovery and molecular optimization tasks. [3] | High (anchored by prior) [3] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing and evaluating action spaces in molecular RL.

Protocol: Implementing a Graph-Based Action Space with Validity Constraints

This protocol is based on the MolDQN framework [1] and is suitable for tasks requiring 100% chemical validity without pre-training.

1. State and Action Space Definition:

- State (s): Represent as a tuple

(m, t), wheremis the current molecule (as a graph) andtis the current step number. Set a maximum step limitT. [1] - Action Space (A): Define as the union of three sets:

- Atom Addition: For each element in

{C, O, N,...}and for each atom in the current molecule, add the new atom connected by every valence-allowed bond type (single, double, triple). The new atom replaces an implicit hydrogen. [1] - Bond Addition: For every pair of existing atoms with free valence and not currently connected with the maximum bond order, allow actions that increase the bond order (e.g., no bond→single, single→double). Apply heuristics to disallow bonds between atoms already in rings. [1]

- Bond Removal: For every existing bond, allow actions that decrease its bond order (e.g., triple→double, double→single, single→no bond). If bond removal creates a lone atom, remove that atom as well. [1]

- Atom Addition: For each element in

2. Validity Checking:

- Before adding an action to the set

Afor states, check it against chemical rules. Remove any action that would violate valence constraints or other implemented heuristics (e.g., no aromatic bond breakage). [1] - This creates a filtered, valid action set

A_valid(s) ⊆ A.

3. Reinforcement Learning Setup:

- Reward (R): Define a reward function based on the target molecular property (e.g., drug-likeness QED, binding affinity pLogP). Apply the reward at each step, discounted by

γ^(T-t)to emphasize final states. [1] - Agent Training: Train a Deep Q-Network (DQN) to estimate Q-values for state-action pairs. The agent selects actions from

A_valid(s).

4. Evaluation:

- Run the trained agent from initial molecules for a fixed number of steps.

- Track the properties of the final molecules and the percentage of valid molecules generated (target: 100%).

- Compare the best-found molecules against baseline algorithms using the target property score.

Protocol: Fine-Tuning with SMILES-Based RL and Validity Preservation

This protocol, inspired by PSV-PPO [5] and REINVENT [3], is used for fine-tuning large pre-trained language models on molecular property optimization.

1. Model and State Setup:

- Prior Model: Start with a transformer or RNN model pre-trained on a large corpus of SMILES strings (e.g., from PubChem or ChEMBL). This model serves as the policy

Ï€_prior. [3] - State (s): The current state is the sequence of tokens generated so far (a partial SMILES string).

2. Action Space and Validation:

- Action Space (A): The vocabulary of SMILES tokens. [5]

- Real-Time Validation (PSV-PPO): At each autoregressive step

t, for the current partial SMILESs_tand a candidate tokena_t, use thepartialsmilespackage [5] to check ifs_t + a_tis a valid partial SMILES. This involves:- Syntax Compliance: Checking SMILES syntax rules.

- Valence Validation: Ensuring atom valences are within acceptable limits.

- Aromaticity Handling: Checking if aromatic systems can be kekulized.

- Create a binary PSV truth table

T(s_t, a_t)which is1if the action is valid and0otherwise. [5]

3. Reinforcement Learning Fine-Tuning:

- Reward (R): The total reward for a fully generated SMILES string is an aggregate score

S(T) ∈ [0, 1]combining multiple property predictors (e.g., QED, SA, DRD2 activity). [3] - Loss Function: Use a modified PPO objective. For PSV-PPO, the loss incorporates the PSV table to penalize invalid token selections. [5] For REINVENT, the loss is:

ℒ(θ) = [ NLL_aug(T|X) - NLL(T|X; θ) ]^2whereNLL_aug(T|X) = NLL(T|X; θ_prior) - σ * S(T). [3] This encourages high scores while keeping the agent close to the prior.

4. Evaluation:

- Generate a large set of molecules (e.g., 10,000) with the fine-tuned model.

- Report the proportion of valid, unique, and novel molecules.

- Calculate the percentage of generated molecules that meet the target property profile and compare the top performers to the starting set.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table lists critical software tools and their functions for implementing RL-based molecular design.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Molecular RL |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecule manipulation, fingerprint generation, property calculation (QED, SA), and valence checks. [1] [8] [7] |

| OpenBabel | Chemical Toolbox | File format conversion and molecular structure handling; often used for bond reconstruction in 3D generation. [9] |

| partialsmiles | Python Package | Provides real-time syntax and valence validation for partial SMILES strings during step-wise generation. [5] |

| GPT-NeoX / Transformers | Deep Learning Library | Architecture backbone for transformer-based generative models (e.g., GraphXForm, BindGPT). [6] [9] |

| OpenAI Baselines / Stable-Baselines3 | RL Library | Provides standard implementations of RL algorithms like PPO, which can be adapted for molecular optimization. [5] |

| Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock) | Simulation Software | Provides binding affinity scores used as reward signals for structure-based RL optimization. [9] |

| BRD-6929 | BRD-6929, MF:C19H17N3O2S, MW:351.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GW297361 | 4-[[(Z)-(7-oxo-6H-pyrrolo[2,3-g][1,3]benzothiazol-8-ylidene)methyl]amino]benzenesulfonamide | Explore 4-[[(Z)-(7-oxo-6H-pyrrolo[2,3-g][1,3]benzothiazol-8-ylidene)methyl]amino]benzenesulfonamide for research. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Visualization: The PSV-PPO Validation Mechanism

The dot code block below details the Partial SMILES Validation mechanism used in the PSV-PPO framework, which ensures token-level validity during SMILES generation. [5]

PSV-PPO Token Validation

This diagram shows the PSV-PPO algorithm's token-level validation. At each step, a candidate token is checked for validity against the current partial SMILES sequence before being appended. Invalid tokens trigger an immediate policy penalty, preventing the generation of invalid molecular structures and stabilizing training.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for tackling complex optimization problems in molecular design. The fundamental components of RL—agents, states, actions, and rewards—form a framework where an intelligent system learns optimal decision-making strategies through interaction with its environment [10] [11]. In molecular design, this translates to an AI agent that learns to generate novel chemical structures with desired properties by sequentially building molecular structures and receiving feedback on their quality [12] [13]. The appeal of RL lies in its ability to navigate vast chemical spaces efficiently, balancing the exploration of novel structural motifs with the exploitation of known pharmacophores, ultimately accelerating the discovery of bioactive compounds for therapeutic applications [13] [14].

Core RL Components in Molecular Context

Theoretical Framework

The RL framework operates through iterative interactions between an agent and its environment. At each time step, the agent observes the current state, selects an action, transitions to a new state, and receives a reward signal [10] [11]. This process is formally modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) defined by the tuple (S, A, P, R, γ), where S represents states, A represents actions, P defines transition probabilities, R is the reward function, and γ is the discount factor balancing immediate versus future rewards [10] [11]. In molecular design, the agent's goal is to learn a policy π that maps states to action probabilities to maximize the cumulative discounted reward, often implemented through sophisticated neural network architectures [15] [12].

Component Definitions and Chemical Instantiations

Table 1: Core RL Components and Their Chemical Implementations

| RL Component | Theoretical Definition | Chemical Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Agent | The decision-maker that interacts with the environment [10] | Generative model (e.g., Stack-RNN, GCPN) that designs molecules [12] [14] |

| Environment | The external system the agent interacts with [11] | Chemical space with rules of chemical validity and property landscapes [12] [16] |

| State (s) | A snapshot of the environment at a given time [11] | Molecular representation (SMILES string, graph, 3D coordinates) [15] [16] |

| Action (a) | Choices available to the agent at any state [11] | Adding atoms/bonds, modifying fragments, changing atomic positions [12] [16] [14] |

| Reward (r) | Scalar feedback received after taking an action [11] | Drug-likeness (QED), binding affinity, synthetic accessibility [12] [13] [14] |

| Policy (Ï€) | Strategy mapping states to actions [10] | Neural network parameters determining molecular generation rules [15] [12] |

In chemical contexts, states typically represent molecular structures using various encoding schemes. Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings provide a sequential representation that can be processed by recurrent neural networks [12]. Graph representations capture atom-bond connectivity, enabling graph neural networks to operate directly on molecular topology [14]. For 3D molecular design, states include atomic coordinates (Ri ∈ R³) and atomic numbers (Zi), defining the spatial conformation of molecules [16].

The action space varies significantly based on the molecular representation. In SMILES-based approaches, actions correspond to selecting the next character in the string sequence from a defined alphabet of chemical symbols [12]. In graph-based approaches, actions involve adding atoms or bonds to growing molecular graphs [14]. For molecular geometry optimization, actions represent adjustments to atomic positions (δRi) [16].

The reward function provides critical guidance by quantifying molecular desirability. Common rewards include calculated physicochemical properties like LogP (lipophilicity), quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), predicted binding affinities from QSAR models, or docking scores [13] [14] [17]. Advanced frameworks incorporate multi-objective rewards that balance multiple properties simultaneously [18] [14].

Quantitative Data in RL-Driven Molecular Design

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RL Approaches in Molecular Optimization

| RL Method | Molecular Representation | Key Properties Optimized | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReLeaSE [12] | SMILES strings | Melting point, hydrophobicity, JAK2 inhibition | Successfully designed libraries biased toward target properties |

| GCPN [14] | Molecular graphs | Drug-likeness, solubility, binding affinity | Generated molecules with desired chemical validity and properties |

| Actor-Critic for Geometry [16] | 3D atomic coordinates | Molecular energy, transition state pathways | Accurately predicted minimum energy pathways for reactions |

| DeepGraphMolGen [14] | Molecular graphs | Dopamine transporter binding, selectivity | Generated molecules with strong target affinity and minimized off-target binding |

| ACARL [17] | SMILES/Graph | Binding affinity with activity cliff awareness | Superior generation of high-affinity molecules across multiple protein targets |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SMILES-Based Molecular Generation with RL

Application: De novo design of drug-like molecules using sequence-based representations [12] [13]

Workflow:

- Initialization: Pre-train a generative model (Stack-RNN) on ChEMBL or similar database to learn valid SMILES syntax [12]

- State Representation: Represent state as incomplete SMILES string (st = characters 0 to t-1) [12]

- Action Selection: At each step, policy network (Ï€) selects next character from SMILES alphabet [12]

- Reward Calculation: Upon complete sequence (terminal state sT), compute reward r(sT) = f(P(sT)) where P is predictive model [12]

- Policy Optimization: Update policy parameters using REINFORCE algorithm with gradient: ∂ΘJ(Θ) = E[Σ∂ΘlogpΘ(at|st-1)r(sT)] [12]

Key Parameters:

- SMILES length: T = 80-100 characters

- Training epochs: 20+ until convergence [13]

- Batch size: 32-128 molecules per update

Protocol 2: Graph-Based Molecular Generation with RL

Application: Constructing molecular graphs with optimized properties [14]

Workflow:

- State Representation: Represent molecule as graph G = (V,E) with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [14]

- Action Space: Define actions as (1) add atom, (2) add bond, (3) terminate generation [14]

- Policy Network: Implement Graph Convolutional Policy Network (GCPN) to process graph state [14]

- Reward Function: Combine property predictions (QED, binding affinity) with chemical validity constraints [14]

- Training: Use actor-critic methods with advantage function A(s,a) = Q(s,a) - V(s) to update policy [14]

Key Parameters:

- Maximum atoms per molecule: 20-50

- Property prediction network architecture: Random Forest or Neural Network

- Experience replay buffer size: 1000-5000 molecules [13]

Protocol 3: Geometry Optimization with Actor-Critic RL

Application: Molecular conformation search and transition state location [16]

Workflow:

- State Representation: Represent molecular conformation as {Zi,Ri} (atomic numbers and positions) [16]

- Action Definition: Atomic position adjustments δRi generated by policy network [16]

- Reward Calculation: Immediate reward based on energy or force improvements [16]

- Critic Network: Estimate value function V(Sk) predicting expected long-term reward from state Sk [16]

- Temporal Difference Learning: Update critic using TD error: δ = (rt + γV(St+1)) - V(St) [16]

Key Parameters:

- Step size for position updates: 0.01-0.1 Ã…

- Discount factor γ: 0.95-0.99

- Advantage calculation: Ak+n = (Σγáµrâ‚œ) - V(Sk) [16]

Visualization of RL Workflows

SMILES-Based Molecular Generation with RL

Actor-Critic Framework for Molecular Geometry

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RL-Driven Molecular Design

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES Grammar | Chemical Representation | Defines valid molecular string syntax and action space [12] | ReLeaSE, REINVENT, ACARL frameworks [12] [17] |

| QSAR Models | Predictive Model | Provides reward signals based on structure-activity relationships [13] | Bioactivity prediction for target proteins [13] [17] |

| Molecular Graphs | Structural Representation | Enables graph-based generation with atom-by-atom construction [14] | GCPN, GraphAF, DeepGraphMolGen [14] |

| Docking Software | Scoring Function | Calculates binding affinity rewards for protein targets [17] | Structure-based reward calculation [17] |

| Experience Replay Buffer | RL Technique | Stores successful molecules to combat sparse rewards [13] | Training stabilization in sparse reward environments [13] |

| Actor-Critic Architecture | RL Algorithm | Combines policy and value learning for molecular optimization [16] | Geometry optimization, pathway prediction [16] |

| Transfer Learning | Training Strategy | Pre-training on general compounds before specific optimization [13] | Addressing sparse rewards in targeted design [13] |

| Multi-Objective Rewards | Reward Design | Balances multiple chemical properties simultaneously [18] [14] | Optimizing affinity, selectivity, and drug-likeness [14] |

Advanced Applications and Methodological Innovations

Addressing Sparse Rewards in Molecular Design

A significant challenge in applying RL to molecular design is the sparse reward problem, where only a tiny fraction of generated molecules exhibit the desired bioactivity [13]. Advanced frameworks address this through several innovative strategies:

- Transfer Learning: Pre-training generative models on large chemical databases (e.g., ChEMBL) before fine-tuning for specific targets [13]

- Experience Replay: Maintaining a buffer of high-reward molecules to reinforce successful strategies during training [13]

- Reward Shaping: Designing intermediate rewards to guide the agent toward promising chemical space [13]

- Uncertainty-Aware Multi-Objective RL: Using surrogate models with predictive uncertainty to balance multiple optimization objectives [18]

Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning

The ACARL framework introduces specialized handling of activity cliffs—situations where small structural changes cause significant activity shifts [17]. This approach incorporates:

- Activity Cliff Index (ACI): A quantitative metric identifying molecular pairs with high structural similarity but large activity differences [17]

- Contrastive Loss: Prioritizes learning from activity cliff compounds during RL fine-tuning [17]

- SAR-Aware Optimization: Explicitly models structure-activity relationship discontinuities for improved generation [17]

Control-Informed Reinforcement Learning

Recent work integrates classical control theory with RL through Control-Informed RL (CIRL), which embeds PID controller components within RL policy networks [19]. This hybrid approach demonstrates:

- Improved Robustness: Enhanced performance against unobserved system disturbances [19]

- Better Generalization: Superior setpoint-tracking for trajectories outside training distribution [19]

- Sample Efficiency: Combines classical control knowledge with RL's nonlinear modeling capacity [19]

Molecular representation learning is a foundational step in bridging machine learning with chemical sciences, enabling applications in drug discovery and material science [20]. The choice of representation—whether string-based encodings like SMILES and SELFIES, or graph-based structures—directly impacts the performance of downstream predictive and generative models, including those using reinforcement learning (RL) for molecular optimization [21] [22]. These representations convert chemical structures into numerical formats that machine learning algorithms can process, each with distinct strengths in handling syntactic validity, semantic robustness, and structural information [23] [24]. This Application Note provides a detailed comparison of these prevalent representations, summarizes quantitative performance data in structured tables, and outlines experimental protocols for their implementation within an RL-driven molecular design framework.

Molecular Representation Formats: Mechanisms and Comparisons

SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System)

SMILES is a string-based notation that represents a molecular graph as a linear sequence of ASCII characters, encoding atoms, bonds, branches, and ring closures [23] [21]. It is a widespread, human-readable format but suffers from generating invalid structures in machine learning models due to its complex grammar and lack of inherent valency checks [23] [24].

SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings)

SELFIES is a rigorously robust string-based representation designed to guarantee 100% syntactic and semantic validity [25] [24]. Built on a formal grammar (Chomsky type-2), every possible SELFIES string corresponds to a valid molecular graph. This is achieved by localizing non-local features (like rings and branches) and incorporating a "memory" that enforces physical constraints (e.g., valency rules) during the string-to-graph compilation process [24]. This makes it particularly suitable for generative models.

Graph-Based Encodings

Graph-based representations directly model a molecule as a graph, where atoms are represented as nodes and bonds as edges [20]. This can be further divided into:

- 2D Molecular Graphs: Capture topological connectivity using an adjacency matrix, node feature matrix (atom types), and edge feature matrix (bond types) [20].

- 3D Molecular Graphs: Incorporate spatial geometric information (atomic coordinates), which is critical for understanding subtle molecular interactions and properties [20] [18].

A specialized approach, Molecular Set Representation Learning (MSR), challenges the necessity of explicit bonds. It represents a molecule as a permutation-invariant set (multiset) of atom invariant vectors, hypothesizing that this can better capture the true nature of molecules where bonds are not always well-defined [26].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representation Schemes

| Representation | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | String-based; Depth-first traversal of molecular graph [21] | Human-readable; Widespread adoption; Simple to use [23] | Multiple valid strings per molecule; No validity guarantee; Complex grammar leads to invalid outputs in ML [23] [27] |

| SELFIES | String-based; Formal grammar & finite-state automaton [24] | 100% robustness; Guaranteed syntactic and semantic validity; Easier for models to learn [25] [24] | Less human-readable; Requires conversion from/to SMILES for some applications [24] |

| 2D Graph | Graph with nodes (atoms) and edges (bonds) [20] | Natural representation; Rich structural information [20] | Neglects spatial 3D geometry; Requires predefined bond definitions [20] |

| 3D Graph | Graph with nodes and edges plus 3D atomic coordinates [20] | Encodes spatial structure & geometric relationships; Crucial for many quantum & physico-chemical properties [20] [18] | Computationally more expensive; Requires availability of 3D conformer data [20] |

| Set (MSR) | Permutation-invariant set of atom-invariant vectors [26] | No explicit bond definitions needed; Challenges over-reliance on graph structure; Simpler models can perform well [26] | Newer, less established paradigm; May not capture all complex topological features [26] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Evaluations across standard benchmarks reveal the practical performance implications of choosing one representation over another. Key metrics include performance on molecular property prediction tasks (e.g., Area Under the Curve - AUC, Root Mean Squared Error - RMSE) and metrics for generative tasks (e.g., validity, uniqueness).

Table 2: Downstream Performance on Molecular Property Prediction Tasks (Classification AUC / Regression RMSE) [23] [26] [27]

| Representation | Model Architecture | HIV (AUC) | Toxicity (AUC) | BBBP (AUC) | ESOL (RMSE) | FreeSolv (RMSE) | Lipophilicity (RMSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES + BPE | BERT-based [23] | ~0.78 | ~0.86 | ~0.92 | - | - | - |

| SMILES + APE | BERT-based [23] | ~0.82 | ~0.89 | ~0.94 | - | - | - |

| SELFIES | SELFormer (Transformer) [27] | - | - | - | 0.944 | 2.511 | 0.746 |

| Set (MSR1) | Set Representation Learning [26] | 0.784 | 0.857 | 0.932 | - | - | - |

| Graph (GIN) | Graph Isomorphism Network [26] | 0.763 | 0.811 | 0.902 | - | - | - |

| Graph (D-MPNN) | Directed Message Passing NN [26] | 0.790 | 0.851 | 0.725 | - | - | - |

Table 3: Generative Model Performance (de novo design) [22] [24]

| Metric | SELFIES + RL/GA | SMILES + RL | Graph-Based GNN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validity (%) | ~100% [24] | ~60-90% [24] | High (>90%) [20] |

| Uniqueness | High [22] | Variable | High |

| Novelty | High [22] | High | High |

| Optimization Efficiency | Outperforms others in QED, SA, ADMET [22] | Lower due to validity issues | Good, but computationally intensive [18] |

Application Protocols for Reinforcement Learning in Molecular Design

The following protocols detail how to implement molecular representation pipelines, specifically tailored for reinforcement learning (RL) applications like multi-property optimization and scaffold-constrained generation.

Protocol 1: SMILES to SELFIES Domain Adaptation for Language Models

Purpose: To cost-effectively adapt a transformer model pre-trained on SMILES to the SELFIES representation, enabling robust molecular property prediction without full retraining [27]. Applications: Leveraging existing SMILES-pretrained models for RL reward prediction or molecular embedding in SELFIES-based generative loops.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Base Model and Data Preparation:

- Start with a SMILES-pretrained transformer model, such as

ChemBERTa-zinc-base-v1[27]. - Obtain a large dataset of molecules in SMILES format (e.g., sample ~700,000 from PubChem [27]).

- Convert the SMILES strings to SELFIES using the

selfies.encoder()function from theselfiesPython library [25] [27].

- Start with a SMILES-pretrained transformer model, such as

Tokenizer Feasibility Check:

- Pass the SELFIES strings through the original model's tokenizer (e.g., Byte Pair Encoding trained on SMILES) [27].

- Critical Check 1: Ensure the

[UNK]token count is negligible, indicating vocabulary compatibility. - Critical Check 2: Verify that the tokenized sequence lengths do not frequently exceed the model's maximum context length (e.g., 512) to avoid truncation [27].

Domain-Adaptive Pretraining (DAPT):

- Perform continued pre-training (e.g., Masked Language Modeling) on the SELFIES corpus using the original, frozen tokenizer and model architecture.

- Computational Note: This process requires significantly less resources (e.g., completed in ~12 hours on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU) than training from scratch [27].

Model Validation and Deployment:

- Embedding-Level Evaluation: Validate the adapted model by using frozen embeddings to predict properties from standard datasets (e.g., QM9). Analyze embedding clusters with t-SNE for chemical coherence [27].

- Downstream Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the model end-to-end on target property prediction tasks (e.g., ESOL, FreeSolv) to serve as a reward function within an RL loop [27].

Protocol 2: Reinforcement Learning-Guided Molecular Generation with SELFIES

Purpose: To generate novel, valid molecules optimized for multiple desired properties using an RL framework enhanced with genetic algorithms [22]. Applications: Direct de novo molecular design for multi-objective optimization (e.g., QED, SA, ADMET) and scaffold-constrained generation in drug discovery.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initialization:

Property Evaluation (Reward Calculation):

- Decode SELFIES to SMILES (using

selfies.decoder) for property calculation [25]. - Use pre-trained or concurrent surrogate models (e.g., for QED, Synthetic Accessibility - SA, and ADMET properties like hERG toxicity) to predict properties for each molecule [22].

- Formulate a composite reward function ( R ) that combines these objectives, optionally using uncertainty estimates from the surrogate models to balance exploration and exploitation [18].

- Example: ( R = w1 \cdot \text{QED} + w2 \cdot (1-\text{SA}) + w_3 \cdot (1-\text{hERG}) )

- Decode SELFIES to SMILES (using

RL and Genetic Algorithm Loop (e.g., RLMolLM Framework):

- Selection: Select parent molecules from the population with a probability proportional to their composite reward (fitness) [22].

- Crossover & Mutation (Genetic Operators):

- Crossover: Combine subsequences of SELFIES from two parent molecules to create offspring.

- Mutation: Randomly modify symbols within a SELFIES string (e.g., substitute, insert, or delete tokens). The robustness of SELFIES ensures all resulting offspring are valid [24].

- RL-Guided Optimization (e.g., Proximal Policy Optimization - PPO): Use an RL agent to guide the selection or generation of SELFIES tokens. The state is the current (partial) SELFIES string, the action is the next token, and the reward is the composite property score of the fully generated molecule [22].

- Replacement: Introduce the new offspring and RL-generated molecules into the population, replacing less fit individuals.

Termination and Output:

- Iterate for a predefined number of generations or until performance plateaus.

- Output the top-performing molecules from the final population for experimental validation.

Protocol 3: Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) for Virtual Screening

Purpose: To identify small molecule candidates with specific biological activity by extracting spatial features directly from molecular graphs, suitable for few-shot learning scenarios [28]. Applications: Rapid virtual screening of large compound libraries for target-specific activity (e.g., inhibiting protein phase separation).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Graph Construction:

GCN Model Training:

- Train a Graph Convolutional Network to map the molecular graph to a binary classification (active/inactive).

- The GCN learns node embeddings by aggregating features from neighboring nodes and edges, followed by a graph-level pooling (e.g., mean pooling) and a final classifier [28].

Virtual Screening and Validation:

- Use the trained GCN to screen a large, diverse chemical library (e.g., 170,000 compounds) [28].

- Select top-ranking predicted actives for experimental validation in the relevant biological assay.

Table 4: Essential Software Tools and Libraries for Molecular Representation Learning

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to RL for Molecular Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| SELFIES Library [25] | Python Library | Encoding/decoding between SMILES and SELFIES; tokenization. | Critical for ensuring 100% validity in string-based generative RL models. |

| RDKit [20] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | SMILES parsing, molecular graph generation, fingerprint calculation, property calculation (e.g., QED). | Standard for featurization, property evaluation (reward calculation), and graph representation. |

| Hugging Face Transformers [23] | NLP Library | Access to pre-trained transformer models (e.g., BERT, ChemBERTa). | Fine-tuning language models for property prediction as reward models. |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) or PyTorch Geometric | Graph ML Library | Implementation of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). | Building and training GNNs on graph-based molecular representations. |

| OpenAI Gym / Custom Environment | RL Framework | Defining the RL environment (states, actions, rewards). | Framework for implementing the RL loop in molecular generation [21] [22]. |

| Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [22] | RL Algorithm | Policy optimization for discrete action spaces (e.g., token generation). | The RL algorithm of choice in several recent molecular generation frameworks [22]. |

Methodological Architectures and Real-World Applications in Drug Discovery

The optimization of molecular design represents a core challenge in modern drug discovery and materials science. The integration of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has catalyzed a paradigm shift, enabling the de novo creation of molecules with tailored properties. Framed within the broader context of reinforcement learning (RL) for molecular optimization, this document details the application notes and experimental protocols for four foundational generative model backbones: Transformers, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Diffusion Models. These architectures serve as the critical engines for exploring the vast chemical space, with RL providing a powerful strategy for steering the generation process toward molecules with desired, optimized characteristics [14]. The following sections provide a structured comparison, detailed methodologies, and essential toolkits for researchers applying these technologies.

Comparative Analysis of Generative Model Backbones

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and challenges of the four primary generative model backbones in the context of molecular design.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Generative Model Backbones for Molecular Design

| Backbone | Core Principle | Common Molecular Representation | Key Strengths | Primary Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | Self-attention mechanism weighing the importance of different parts of an input sequence [29]. | SMILES, SELFIES [30] [31] | Excels at capturing long-range dependencies and complex grammar in string-based representations [29] [14]. | Standard positional encoding can struggle with scaffold-based generation and variable-length functional groups [29]. |

| VAE | Encodes input data into a probabilistic latent space and decodes it back [32] [14]. | SMILES, Molecular Graphs [29] [14] | Learns a smooth, continuous latent space ideal for interpolation and optimization via Bayesian methods [31] [14]. | Can generate blurry or invalid outputs; the prior distribution may oversimplify the complex chemical space [14]. |

| GAN | A generator and discriminator network are trained adversarially [29] [14]. | SMILES, Molecular Graphs [29] [33] | Capable of producing highly realistic, high-fidelity molecular structures [29] [32]. | Training can be unstable; particularly challenging for discrete data like SMILES strings [29] [14]. |

| Diffusion Model | Iteratively adds noise to data and learns a reverse denoising process [32] [14]. | Molecular Graphs, 3D Structures [31] [14] | State-of-the-art performance in generating high-quality, diverse outputs [32] [14]. | Computationally intensive and slow sampling due to the multi-step denoising process [32] [14]. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Transformer-Driven Molecular Generation with RL

Transformers process molecular sequences using a self-attention mechanism, allowing each token (e.g., an atom symbol in a SMILES string) to interact with all others, thereby capturing complex, long-range dependencies crucial for chemical validity [29] [30]. Their application is particularly powerful when combined with reinforcement learning for property optimization.

Protocol: RL-Driven Transformer GAN (RL-MolGAN) for De Novo Generation

This protocol outlines the methodology for the RL-MolGAN framework, which integrates a Transformer decoder as a generator and a Transformer encoder as a discriminator [29].

- Objective: To generate novel, chemically valid SMILES strings optimized for specific chemical properties.

- Materials:

- Datasets: QM9 or ZINC datasets for training and benchmarking [29].

- Representation: SMILES strings tokenized at the atom/substructure level.

- Model Architecture:

- Generator: A Transformer decoder network that autoregressively generates SMILES strings token-by-token.

- Discriminator: A Transformer encoder network that classifies SMILES strings as real or generated.

- Procedure:

- Step 1 - Pre-training: Pre-train the generator on a dataset of valid molecules (e.g., ZINC) to learn the fundamental syntax and grammar of SMILES strings.

- Step 2 - Adversarial Training: Train the generator and discriminator in an alternating manner. The generator produces SMILES strings, and the discriminator provides adversarial feedback.

- Step 3 - Reinforcement Learning Fine-Tuning: Integrate a reinforcement learning agent (e.g., using a policy gradient method) with the generator. The agent uses a reward function that combines:

- Adversarial Reward: From the discriminator, encouraging generation of drug-like molecules.

- Property Reward: Based on the predicted or calculated chemical properties of the generated molecule (e.g., drug-likeness, solubility).

- Validity Reward: A penalty or bonus for the chemical validity of the generated SMILES string [29].

- Step 4 - Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): Employ MCTS during the generation process to explore the sequence of token decisions, enhancing the stability of training and the quality of the output [29].

- Step 5 - Validation: Assess the generated molecules using standard metrics (see Table 2).

- Notes: The "first-decoder-then-encoder" structure of RL-MolGAN is a key deviation from standard Transformers, enhancing its capability for generation tasks [29]. An extension, RL-MolWGAN, incorporates Wasserstein distance and mini-batch discrimination for improved training stability [29].

Diagram 1: RL-MolGAN Workflow (77 characters)

VAE for Latent Space Optimization

VAEs learn a compressed, continuous latent representation of molecules, making them well-suited for optimization tasks where navigating a smooth latent space is more efficient than operating in the high-dimensional structural space.

Protocol: Property-Guided Molecule Generation with VAE and Bayesian Optimization

This protocol describes using a VAE to create a latent space of molecules, which is then searched using Bayesian optimization to find molecules with desired properties [14].

- Objective: To discover molecules with optimized target properties by searching the continuous latent space of a VAE.

- Materials:

- Datasets: Large molecular libraries (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC).

- Model Architecture: A VAE with an encoder and decoder network. The encoder maps a molecule (as a SMILES string or graph) to a mean and variance vector, which are then sampled to create a latent vector

z. The decoder reconstructs the molecule fromz[14]. - Property Predictor: A separate model (e.g., a fully connected network) that predicts the target property from the latent vector

z.

- Procedure:

- Step 1 - VAE Training: Train the VAE on a large dataset of molecules. The loss function is a combination of reconstruction loss (ensuring decoded molecules match the input) and the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence loss (regularizing the latent space to be close to a standard normal distribution).

- Step 2 - Property Predictor Training: Train the property predictor model on a labeled dataset using the latent vectors

zfrom the VAE encoder as input and the corresponding molecular properties as the target. - Step 3 - Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Step 3.1 - Build Surrogate Model: Model the property predictor's landscape as a probabilistic surrogate, typically a Gaussian Process.

- Step 3.2 - Select Candidate: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to select the most promising latent vector

z_candidateto evaluate next. - Step 3.3 - Decode and Validate: Decode

z_candidateinto a molecule structure and validate its chemical properties using the predictor or more expensive simulations. - Step 3.4 - Update Model: Update the surrogate model with the new data point (

z_candidate, property value).

- Step 4 - Iterate: Repeat steps 3.2 to 3.4 until a molecule satisfying the target criteria is found or the budget is exhausted.

- Notes: The quality of the latent space is critical. Techniques like InfoVAE can be used to avoid the "posterior collapse" issue, where the latent space is underutilized [14].

GANs for Realistic Molecular Graph Generation

GANs are renowned for their ability to generate high-fidelity data. In molecular design, they can be trained to produce realistic molecular graphs or valid SMILES strings.

Protocol: Graph-Convolutional Policy Network (GCPN) for Molecular Optimization

GCPN is a representative framework that combines GANs with RL for graph-based molecular generation [1] [14].

- Objective: To generate novel molecular graphs with optimized chemical properties through a sequential, reinforcement learning-driven graph construction process.

- Materials:

- Representation: Molecular graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges).

- Model Architecture: A graph convolutional network (GCN) serves as the policy network for the RL agent.

- Procedure:

- Step 1 - Define Action Space: The agent's actions involve adding a new atom (with a specific element type) or forming a new bond (with a specific bond type) between existing atoms, ensuring chemical validity at each step [1].

- Step 2 - State Representation: The current state of the partially generated molecular graph is represented using its graph structure and node (atom) features.

- Step 3 - Policy Network: The GCN processes the state representation to produce a probability distribution over all valid actions.

- Step 4 - Rollout and Reward: The agent sequentially builds the molecule. Upon completion (or at each step), a reward is computed based on the target molecular properties (e.g., drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, binding affinity) [14].

- Step 5 - Policy Update: The policy network is updated using a policy gradient method (e.g., REINFORCE or PPO) to maximize the expected cumulative reward.

- Notes: GCPN ensures 100% chemical validity by restricting the action space to only chemically plausible steps [1]. The adversarial component can be integrated via a discriminator that rewards the generator for producing molecules that are indistinguishable from those in the real training dataset.

Emerging Role of Diffusion Models

Diffusion models have recently shown state-of-the-art performance in generative modeling. They work by iteratively denoising data, starting from pure noise.

Protocol: Geometric Diffusion for 3D-Aware Molecular Generation

This protocol outlines the use of diffusion models for generating molecules in 3D space, capturing critical geometric and energetic information [31].

- Objective: To generate 3D molecular structures that are not only chemically valid but also geometrically realistic and optimized for properties dependent on 3D conformation.

- Materials:

- Datasets: Datasets with 3D structural information, such as crystal structures or quantum-chemically optimized conformers.

- Representation: 3D graphs with node features (atom type) and edge features (bond type, distance).

- Procedure:

- Step 1 - Forward Noising Process: Iteratively add Gaussian noise to the 3D coordinates and features of a real molecular graph over a series of timesteps

T. - Step 2 - Reverse Denoising Process: Train a neural network (e.g., an Equivariant GNN) to learn the reverse process. This network takes a noisy molecular graph at timestep

tand predicts the clean graph at timestept-1. - Step 3 - Sampling: To generate a new molecule, start from a completely noisy graph and iteratively apply the trained denoising network for

Tsteps. - Step 4 - Property Guidance: Condition the denoising process on target properties using classifier-free guidance. This involves training the model to denoise both conditioned (on property) and unconditioned, allowing control over the generated molecules' properties during sampling [31] [14].

- Step 1 - Forward Noising Process: Iteratively add Gaussian noise to the 3D coordinates and features of a real molecular graph over a series of timesteps

- Notes: Diffusion models are computationally demanding but excel at capturing complex data distributions. They are particularly promising for designing molecules where 3D structure directly influences function, such as in drug binding or materials science [31].

Performance Benchmarking

Benchmarking generative models requires evaluating multiple aspects of performance, from basic validity to the ability to optimize for desired properties.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Molecular Generative Models

| Metric | Description | Interpretation and Target |

|---|---|---|

| Validity | Percentage of generated structures that correspond to a chemically valid molecule. | A fundamental metric; modern graph-based and SELFIES models can achieve ~100% [29] [1]. |

| Uniqueness | Percentage of valid molecules that are unique (not duplicates). | Measures the diversity of the generator. High uniqueness is desired to explore chemical space. |

| Novelty | Percentage of unique, valid molecules not present in the training dataset. | Indicates the model's ability to generate truly new structures, not just memorize. |

| Property Optimization | The ability to maximize or minimize a specific molecular property (e.g., drug-likeness QED, solubility). | The core goal of RL-driven optimization. Performance is measured by the achieved property value in top-generated candidates. |

| Time/Cost to Generate | The computational time or resource cost required to generate a set number of valid molecules. | Critical for practical applications. Diffusion models are often slower than GANs or VAEs [32]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Generation Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Generative Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Manipulation and analysis of chemical structures, descriptor calculation, and reaction handling. | The industry standard for converting between molecular representations (SMILES, graphs), calculating properties, and validating generated structures [1]. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep Learning Framework | Provides building blocks for designing, training, and deploying neural networks. | Used to implement all core generative model architectures (Transformers, VAEs, GANs, Diffusion Models) and RL algorithms. |

| DeepChem | Deep Learning Library for Drug Discovery | Provides high-level abstractions and pre-built models for molecular machine learning tasks. | Offers implementations of graph networks and tools for handling molecular datasets, accelerating model development and prototyping. |

| QM9, ZINC | Molecular Datasets | Curated databases of chemical structures and their properties. | Standard benchmarks for training and evaluating generative models. QM9 is for small organic molecules, while ZINC contains commercially available drug-like compounds [29]. |

| OpenAI Gym | RL Environment Toolkit | Provides a standardized API for developing and comparing reinforcement learning algorithms. | Can be adapted to create custom environments for molecular generation, where the state is the molecule and actions are structural modifications [1]. |

| EM 1404 | EM 1404, MF:C25H33NO3, MW:395.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| EPZ020411 | N,N'-dimethyl-N'-[[5-[4-[3-[2-(oxan-4-yl)ethoxy]cyclobutyl]oxyphenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]methyl]ethane-1,2-diamine | High-purity N,N'-dimethyl-N'-[[5-[4-[3-[2-(oxan-4-yl)ethoxy]cyclobutyl]oxyphenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]methyl]ethane-1,2-diamine for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The application of reinforcement learning (RL) to molecular design represents a paradigm shift in computational drug discovery, enabling the inverse design of novel compounds with specific, desirable properties. This approach reframes molecular generation as an optimization problem, mapping a set of target properties back to the vast chemical space. The REINVENT framework has emerged as a leading open-source tool that powerfully integrates prior chemical knowledge with RL steering to navigate this space efficiently. By leveraging generative artificial intelligence, REINVENT addresses the core challenge of de novo molecular design: the systematic and rational creation of novel, synthetically accessible molecules tailored for therapeutic applications [34] [35].

REINVENT operates within the established Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle, directly contributing to the critical "Design" phase. Its modern implementation, REINVENT 4, provides a well-designed, complete software solution that facilitates various design tasks, including de novo design, scaffold hopping, R-group replacement, linker design, and molecule optimization [34]. The framework's robustness stems from its seamless embedding of powerful generative models within general machine learning optimization algorithms, making it both a production-ready tool and a reference implementation for education and future innovation in AI-based molecular design [34] [36].

Core Architecture and Technical Foundation

The technical foundation of REINVENT is built upon a principled combination of generative models, a sophisticated scoring system, and a reinforcement learning mechanism that steers the generation towards desired chemical space.

Molecular Representation and Generative Agents

At its core, REINVENT utilizes sequence-based neural network models, specifically recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and transformers, which are parameterized to capture the probability of generating tokens in an auto-regressive manner [34]. These models, termed "agents," operate on SMILES strings (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), a textual representation of chemical structures.

The agents learn the underlying syntax and probability distribution of SMILES strings from large datasets of known molecules. The joint probability ( \textbf{P}(T) ) of generating a particular token sequence ( T ) of length ( \ell ) (representing a molecule) is given by the product of conditional probabilities [34]: [ \textbf{P} (T) = \prod {i=1}^{\ell }\textbf{P}\left( ti\vert t{i-1}, t{i-2},\ldots, t_1\right) ]

These pre-trained "prior" agents act as unbiased molecule generators, encapsulating fundamental chemical knowledge and rules of structural validity. They are trained on large public datasets (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC) using teacher-forcing to minimize the negative log-likelihood of the training sequences [34] [37]. Once trained, these priors can sample hundreds of millions of unique, valid molecules, far exceeding the diversity of their training data [34].

The Reinforcement Learning Cycle

The integration of prior knowledge with RL steering is achieved through a structured cycle involving three key components: a generative agent, a scoring function, and a policy update algorithm.

Table 1: Core Components of the REINVENT RL Framework

| Component | Description | Function in the Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Prior Agent | A pre-trained generative model (RNN/Transformer) on a large molecular dataset. | Provides the initial policy and ensures generated molecules are chemically valid. Serves as a baseline distribution. |

| Agent | The current generative model being optimized. | Proposes new molecular structures (SMILES strings) for evaluation. |

| Scoring Function | A user-defined function composed of multiple components. | Calculates a reward score for generated molecules based on target properties (e.g., bioactivity, drug-likeness). |

| Policy Gradient | The RL optimization algorithm (e.g., REINFORCE). | Updates the agent's parameters to increase the probability of generating high-scoring molecules. |

The standard REINVENT RL workflow, as detailed in multiple studies [34] [37] [38], can be summarized in the following workflow diagram:

The scoring function is a critical element, acting as the "oracle" that guides the optimization. It is typically a composite reward, ( R(m) ), calculated for a generated molecule ( m ). A common form is the weighted geometric mean of multiple normalized components [38]: [ R(m) = \left( \prod{i=1}^{n} Ci(m)^{wi} \right)^{1 / \sum wi} ] where ( Ci(m) ) is the i-th score component (e.g., predicted activity, QED, SAscore) and ( wi ) is its corresponding weight. This multi-objective formulation is essential for practical drug discovery, where candidates must balance potency with favorable physicochemical and ADMET properties.

Advanced Optimization and Integration Strategies

While the core RL loop is powerful, several advanced strategies have been developed to enhance its sample efficiency, stability, and ability to overcome common pitfalls like reward hacking.

Addressing the Sparse Reward Challenge

A significant challenge in target-oriented molecular design is sparse rewards, where only a tiny fraction of randomly generated molecules show any predicted activity for a specific biological target [37]. This can cause the RL agent to struggle to find a learning signal. REINVENT and its derivatives have incorporated several technical innovations to mitigate this [37]:

- Experience Replay: Maintaining a memory buffer of high-scoring molecules encountered during training and periodically re-sampling them to reinforce positive behavior.

- Transfer Learning: Fine-tuning a generative model pre-trained on a general corpus (e.g., ChEMBL) on a smaller set of molecules known to be active against the specific target. This provides a better starting point for RL optimization.

- Real-Time Reward Shaping: Adjusting the reward function dynamically during training to provide a more informative gradient, for instance, by focusing on incremental improvements.

Studies have demonstrated that the combination of policy gradient algorithms with these techniques can lead to a substantial increase in the number of generated molecules with high predicted activity, overcoming the limitations of using policy gradient alone [37].

Active Learning for Sample Efficiency

The integration of Active Learning (AL) with REINVENT's RL cycle (RL–AL) has been shown to dramatically improve sample efficiency, which is critical when using computationally expensive oracle functions like free-energy perturbation (FEP) or molecular docking [38].

In the RL–AL framework, a surrogate model (e.g., a random forest or neural network) is trained to predict the expensive oracle score based on a subset of evaluated molecules. This surrogate's predictions, or an acquisition function based on them, then guide the selection of which molecules to evaluate with the true, expensive oracle. This creates an inner loop that reduces the number of costly calls needed.

This hybrid approach has demonstrated a 5 to 66-fold increase in hit discovery for a fixed oracle call budget and a 4 to 64-fold reduction in computational time to find a specific number of hits compared to baseline RL [38]. The following protocol outlines the steps for implementing an RL–AL experiment.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| REINVENT4 | Software Framework | Core environment for running generative ML and RL optimization [34] [39]. |

| ChEMBL Database | Molecular Dataset | Source of pre-training data for the Prior agent, providing general chemical knowledge [37] [38]. |

| Oracle Function | Computational Model | Provides the primary reward signal (e.g., docking score, QSAR model prediction, QED) [37] [38]. |

| Surrogate Model | Machine Learning Model | Predicts oracle scores to reduce evaluation cost; often a Random Forest or Gaussian Process [38]. |

| SMILES/SELFIES | Molecular Representation | String-based representations of molecular structure for the generative model [34] [35]. |

Ensuring Reliability in Multi-Objective Optimization

Reward hacking is a known risk in RL-driven molecular design, where the generator exploits inaccuracies in the predictive models to produce molecules with high predicted scores but invalid real-world properties, often by drifting outside the predictive model's domain of applicability [40].

The DyRAMO (Dynamic Reliability Adjustment for Multi-objective Optimization) framework has been proposed to counter this. DyRAMO dynamically adjusts the reliability levels (based on the Applicability Domain - AD) of multiple property predictors during the optimization process [40]. It uses Bayesian Optimization to find the strictest reliability thresholds that still allow for successful molecular generation, ensuring that designed molecules are both optimal and fall within the reliable region of all predictive models. The reward function in DyRAMO is set to zero if a molecule falls outside any defined AD, strongly penalizing unreliable predictions.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard RL-Driven Molecular Optimization with REINVENT

This protocol details the steps for optimizing molecules for a specific profile, such as high activity against a protein target coupled with favorable drug-like properties [34] [37].

- Configuration Setup: Define the experiment in a TOML or JSON configuration file. Specify paths to the prior agent file, the initial agent (often a copy of the prior), and the output directory.

- Scoring Function Definition: Construct the scoring function in the configuration file. A typical example for a kinase inhibitor might be:

- Component 1: An IC50 prediction model for EGFR (normalized to 0-1).

- Component 2: Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED).

- Component 3: Synthetic Accessibility Score (SAScore).

- Set weights for each component (e.g.,

[0.7, 0.2, 0.1]) to prioritize activity.

- RL Parameters: Set learning parameters such as the learning rate, batch size (number of molecules generated per step), number of steps, and the sigma parameter for the policy gradient, which controls the steepness of the optimization.

- Run Execution: Launch REINVENT from the command line. The software will run the iterative loop of sampling, scoring, and updating.

- Monitoring and Analysis: Monitor the output logs and generated SMILES files. The run produces checkpoints of the optimized agent and files containing the sampled molecules and their scores at each step, allowing for tracking of progress over time.

Protocol 2: Integrating Active Learning with RL (RL–AL)

This protocol augments the standard RL process with a surrogate model to maximize the efficiency of an expensive oracle [38].

- Initialization: Perform steps 1-3 from Protocol 1. Additionally, define the surrogate model architecture (e.g., Random Forest, Neural Network) and the acquisition function (e.g., upper confidence bound, expected improvement).

- Initial Sampling: Run the initial agent to generate a large set of molecules (e.g., 10k). Select a small, diverse subset (e.g., 100) and evaluate them with the true, expensive oracle to create an initial training set for the surrogate.

- AL Loop: For a fixed number of AL iterations: a. Surrogate Training: Train the surrogate model on all molecules evaluated with the true oracle so far. b. Agent Sampling and Preselection: Let the current RL agent generate a large batch of molecules. Use the surrogate model to score this batch and preselect the top-ranking molecules according to the acquisition function. c. Oracle Evaluation: Evaluate the preselected molecules with the true, expensive oracle. d. Agent Update: Use the scores from the true oracle to compute the RL loss and update the generative agent via policy gradient.

- Termination: The loop terminates once a computational budget (wall time or oracle calls) is exhausted or performance plateaus. The final optimized agent can be used for focused exploration.

Application Example: Design of EGFR Inhibitors

A proof-of-concept study demonstrated the use of an optimized RL pipeline to design novel Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) inhibitors [37]. The methodology involved:

- Prior Model: A generative RNN pre-trained on the ChEMBL database.

- Oracle Function: A random forest QSAR classifier trained to predict active vs. inactive compounds against EGFR.

- RL Optimization: The agent was optimized using a policy gradient algorithm combined with experience replay and transfer learning to address sparse rewards.

- Experimental Validation: Selected computationally generated hits were procured and tested in vitro, confirming potent EGFR inhibition and validating the entire pipeline [37].

This successful application underscores REINVENT's capability to not only explore chemical space but to also discover genuinely novel, bioactive compounds with real-world therapeutic potential.

The discovery and optimization of novel antioxidant compounds represent a significant challenge in chemical and pharmaceutical research. Traditional methods can be time-consuming and costly, often struggling to efficiently navigate the vastness of chemical space. Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for de novo molecular design, framing the search for molecules with desired properties as a sequential decision-making process [1] [12]. However, the application of RL to molecular optimization faces two primary challenges: limited scalability to larger datasets and an inability for models to generalize learning across different molecules within the same dataset [41].

This application note presents a case study on DA-MolDQN (Distributed Antioxidant Molecule Deep Q-Network), a distributed reinforcement learning algorithm designed specifically to address these limitations in the context of antioxidant discovery. By integrating state-of-the-art chemical property predictors and introducing key algorithmic improvements, DA-MolDQN enables the efficient and generalized discovery of novel antioxidant molecules [41].

The DA-MolDQN Framework

Foundation and Core Innovations