Predicting Synthesis Feasibility: A Guide to Identifying Viable Materials for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying materials with high synthesis feasibility—a critical step in accelerating the discovery of functional materials.

Predicting Synthesis Feasibility: A Guide to Identifying Viable Materials for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying materials with high synthesis feasibility—a critical step in accelerating the discovery of functional materials. It explores the foundational principles of material stability from thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives, reviews advanced methodologies from high-pressure techniques to machine learning (ML)-assisted synthesis, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. The content further covers validation frameworks and comparative analysis of synthesis routes, synthesizing key takeaways to outline future directions for biomedical and clinical research. By integrating computational guidance with experimental practices, this resource aims to shorten the material discovery cycle from years to months.

Foundations of Material Stability: Understanding Thermodynamic and Kinetic Principles

Defining Synthesis Feasibility in Material Science

Definition and Key Concepts

In material science, synthesis feasibility refers to the practical assessment of whether a proposed method for creating a new material can be successfully carried out. This evaluation encompasses multiple dimensions, from the fundamental chemistry to project management constraints [1].

A feasible synthesis pathway must demonstrate that it can produce the target material using available methods and resources, while satisfying requirements for efficiency, cost, and safety [1]. For novel inorganic compounds, this often involves specialized techniques like high-pressure synthesis, which can create unprecedented materials that remain stable under atmospheric conditions, such as high-temperature superconductors with transition temperatures up to 250 K or ultra-hard nano-diamonds [2].

Core Components of Feasibility Assessment

- Technical Viability: Whether the necessary reactions can proceed with sufficient yield and purity, considering factors like reaction mechanisms and potential side reactions [1]

- Resource Availability: Access to required starting materials, specialized equipment, and technical expertise [3]

- Economic Practicality: Balance between research benefits and required investment in time, equipment, and materials [1]

- Environmental Considerations: Waste production, toxicity of reagents, and overall sustainability of the synthetic pathway [1]

- Temporal Factors: Reasonable timeframes from initial concept to material characterization [3]

Methodologies for Assessing Synthesis Feasibility

A structured approach to feasibility assessment helps researchers systematically evaluate potential synthesis pathways before committing significant resources.

The Eight Domains of Feasibility Analysis

Adapted from public health research but applicable to material science, these domains provide a comprehensive framework for evaluation [4]:

Table 1: Feasibility Assessment Framework for Material Synthesis

| Domain | Assessment Focus | Material Science Application |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Judgments of suitability, satisfaction, or attractiveness | How target users perceive the new material's properties and potential applications |

| Demand | Estimated or actual use | Potential market adoption or research application breadth |

| Implementation | Capability to execute synthesis as planned | Availability of specialized equipment (e.g., HTHP systems) and technical expertise |

| Practicality | Delivery within resource constraints | Synthesis possible with available time, budget, and personnel |

| Adaptation | Changes needed for new formats or populations | Modifications required for scaling from lab to production |

| Integration | Fit with existing systems | Compatibility with current manufacturing or research infrastructure |

| Expansion | Potential success in different contexts | Material's applicability across multiple industries or research fields |

| Limited Efficacy Testing | Promise of success under controlled conditions | Preliminary validation of material properties in lab settings |

Systematic Synthesis Approach

The systems engineering approach to synthesis involves iterative activities to develop possible solutions [5]:

- Identification of System Boundaries: Determining the scope of the synthesis problem and constraints [5]

- Functional Analysis: Defining what the material must accomplish [5]

- Element Identification: Specifying required components, reagents, and equipment [5]

- Interaction Mapping: Understanding how synthesis components interact [5]

This workflow can be visualized as a iterative process:

Troubleshooting Common Synthesis Challenges

Technical Feasibility Issues

Problem: Inability to Achieve Required Synthesis Conditions

- Root Cause: Insufficient equipment capability or unstable intermediate compounds [1]

- Solution: Explore alternative synthesis pathways or modified target material composition

- Preventive Measures: Conduct thorough computational modeling before experimental work

Problem: Low Yield or Purity

- Root Cause: Side reactions, incomplete processes, or contamination [1]

- Solution: Optimize reaction parameters, introduce purification steps, or modify synthesis route

- Validation: Implement analytical techniques (XRD, SEM, NMR) at multiple stages [6]

Problem: Unstable or Highly Reactive Intermediates

- Root Cause: Material properties that prevent isolation or characterization [1]

- Solution: Develop in-situ analysis methods or adjust synthesis to minimize unstable intermediates

Resource and Practicality Challenges

Problem: Limited Access to Specialized Equipment

- Root Cause: High-cost equipment requirements (e.g., HTHP systems) [2]

- Solution: Seek collaborative partnerships or utilize shared research facilities

Problem: Scarce or Expensive Starting Materials

- Root Cause: Limited natural abundance or complex purification requirements [7]

- Solution: Investigate alternative precursors or develop more efficient recycling methods

Current Investment Trends in Material Discovery

Understanding funding priorities helps researchers align projects with available resources and industry needs.

Global Investment in Materials Discovery (2020-2025)

Table 2: Materials Discovery Investment Trends (2020 - Mid 2025) [7]

| Year | Equity Investment (USD) | Grant Funding (USD) | Key Sector Developments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | $56 million | Not specified | Early-stage research focus |

| 2023 | Not specified | $59.47 million | Infleqtion quantum technology grant: $56.8M |

| 2024 | Not specified | $149.87 million | Mitra Chem battery materials: $100M DOE grant |

| Mid-2025 | $206 million | Not specified | Growth in computational materials science |

Funding Distribution Across Material Sub-segments

Table 3: Investment Distribution in Materials Discovery Sub-segments [7]

| Sub-segment | Cumulative Funding (2020-2025) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Discovery Applications | $1.3 billion | Decarbonization technologies |

| Computational Materials Science | $168 million (by mid-2025) | Simulation-based R&D acceleration |

| Materials Databases | $31 million (2025) | AI-enabled discovery workflows |

| Robotics for Materials Discovery | Minimal | Automated experimentation |

Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesis Feasibility Testing

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Synthesis Feasibility Studies

| Reagent/Equipment Category | Specific Examples | Function in Feasibility Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| High-Pressure Synthesis Systems | HTHP (High-Temperature High-Pressure) apparatus | Enables synthesis of novel inorganic compounds [2] |

| Computational Modeling Tools | DFT software, molecular dynamics simulations | Predicts material properties and reaction pathways before experimental work |

| Analytical Characterization | XRD, SEM, NMR spectroscopy [6] | Validates synthesis success and material structure |

| Custom Synthesis Services | Specialized chemical producers | Provides compounds not available commercially [3] |

| Metamaterial Fabrication Tools | 3D printing, lithography, etching systems | Creates engineered materials with properties not found in nature [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the difference between technical feasibility and practical feasibility in material synthesis?

Technical feasibility addresses whether the fundamental chemical and physical processes can produce the target material, while practical feasibility considers whether the synthesis can be accomplished within real-world constraints of time, budget, and available resources [1]. A synthesis may be technically possible but practically unfeasible due to cost or safety concerns.

Q2: How do I determine if custom synthesis is preferable to using commercially available compounds?

Custom synthesis is recommended when your project requires specific structural or functional characteristics not available in commercial compounds, when working with proprietary materials, or for advanced development projects. Commercial compounds are more suitable for standard applications, budget-constrained projects, or when immediate availability is crucial [3].

Q3: What are the most common reasons for synthesis feasibility failure?

The most common failure points include: (1) unstable intermediates that cannot be isolated, (2) prohibitively expensive starting materials or equipment requirements, (3) inability to achieve required purity levels, (4) unacceptable environmental or safety impacts, and (5) time requirements that exceed project constraints [1].

Q4: How has high-pressure synthesis expanded the range of feasible materials?

High-pressure methods can create unprecedented inorganic compounds that remain stable under atmospheric conditions, including high-temperature superconductors (transition temperatures up to 250 K) and super-hard nano-diamonds with hardness approaching 1 TPa - materials that cannot be achieved through other synthetic methods [2].

Q5: What role do computational methods play in assessing synthesis feasibility?

Computational materials science has seen steady investment growth, reaching $168 million by mid-2025 [7]. These tools enable researchers to simulate material properties and reactions before laboratory work, significantly reducing trial-and-error experimentation and accelerating the identification of promising synthesis pathways.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my catalyst, predicted to be thermodynamically stable, degrade rapidly during the oxygen evolution reaction (OER)?

Your catalyst may be thermodynamically stable at rest but encounter kinetic instability under operational conditions. High anodic potentials and corrosive oxidative environments during OER can create kinetic barriers that favor catalyst dissolution or phase transformation over stability. This is a common challenge where operational kinetics override thermodynamic predictions [9].

Q2: How can I quickly assess if a material with high thermodynamic stability has impractically slow reaction kinetics?

A key indicator is a high overpotential, particularly for the OER. A large overpotential signifies a substantial kinetic barrier that the reaction must overcome, even if it is thermodynamically favorable. Evaluate the Tafel slope; a higher slope suggests slower reaction kinetics and a more significant kinetic hindrance [9].

Q3: What are the primary causes of a high kinetic barrier in an otherwise stable catalyst material?

The main causes are often related to slow reaction pathways. This can include inadequate active site density, poor electron transfer kinetics, or strong reactant binding that leads to high activation energies and sluggish surface reaction rates [9].

Q4: My catalyst shows excellent activity but poor long-term stability. Is this a kinetic or thermodynamic issue?

This typically points to a kinetic issue. The material may be thermodynamically metastable. While initial activity is high, the system may be slowly progressing toward a more stable, but less active, state over time. This underscores the necessity of evaluating both activity and stability under realistic conditions [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Performance Metrics Between Laboratory and Pilot-Scale Reactors

| Observation | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Activity (e.g., turnover frequency) decreases at larger scale. | Mass transport limitations not present in small-scale lab setups. | Redesign catalyst structure (e.g., create porous nanostructures) to enhance reactant flow to active sites [9]. |

| Stability is lower in pilot-scale testing. | Inability to maintain potential and pH gradients at scale. | Integrate robust, conductive support materials to improve electronic conductivity and structural integrity [9]. |

Problem: Failure to Achieve Predicted Catalytic Activity

| Observation | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High overpotential for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). | Low active site density or poor electronic conductivity. | Employ doping or heterojunction engineering to modulate the electronic structure and create more active sites [9]. |

| Tafel slope is higher than calculated. | Non-optimal adsorption energy of reaction intermediates. | Use computational modeling to screen for materials with near-optimal intermediate binding energies before synthesis [9]. |

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for Benchmarking Catalysts [9]

| Performance Indicator | Target for HER | Target for OER | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overpotential (at 10 mA/cm²) | < 50 mV | < 300 mV | Linear sweep voltammetry |

| Tafel Slope | < 40 mV/dec | < 60 mV/dec | Tafel plot analysis |

| Turnover Frequency (TOF) | > 1 s⁻¹ | > 0.1 s⁻¹ | Calculated from activity and active sites |

| Stability (Duration) | > 100 hours | > 100 hours | Chronopotentiometry |

| Electrochemical Surface Area (ECSA) | High relative to geometric area | High relative to geometric area | Double-layer capacitance (Cdl) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Thermodynamic Stability via Electrochemical Potential

Objective: To assess the thermodynamic stability of a catalyst material within a specific potential window.

Materials:

- Working electrode (catalyst on substrate)

- Counter electrode (e.g., Pt wire)

- Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl)

- Potentiostat

- Aqueous electrolyte (e.g., 0.5 M H₂SO₄ for HER, 1 M KOH for OER)

Methodology:

- Setup: Prepare a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell with the catalyst as the working electrode.

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Perform CV scans at a slow rate (e.g., 1-5 mV/s) across a wide potential range, from cathodic to anodic regions.

- Data Analysis: Identify regions where a non-faradaic current is stable, indicating a potential window of thermodynamic stability. Peaks in the current indicate oxidation or reduction events, signifying thermodynamic phase transitions or dissolution.

- Comparison: Correlate the stability window with the thermodynamic redox potentials of the catalyst's constituent elements.

Protocol 2: Measuring Kinetic Barriers via Tafel Analysis

Objective: To determine the kinetic barrier and rate-determining step of the HER or OER.

Materials:

- Same electrochemical setup as Protocol 1.

Methodology:

- Polarization Curve: Obtain a steady-state polarization curve (current density vs. applied potential) by performing linear sweep voltammetry at a slow scan rate.

- Tafel Plot: Plot the overpotential (η) against the log of the current density (log |j|). The linear region of this plot is the Tafel region.

- Slope Calculation: Fit the linear region to the Tafel equation (η = a + b log j), where

bis the Tafel slope. - Interpretation: A lower Tafel slope indicates faster reaction kinetics and a lower kinetic barrier. The value of the slope can also provide insight into the catalytic mechanism and the rate-determining step [9].

Visualization Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Electrolytic Water Splitting [9]

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | The core instrument for applying controlled potentials/currents and measuring the electrochemical response of the catalyst. |

| Standard Electrodes (Ag/AgCl, Hg/HgO) | Reference electrodes to provide a stable potential baseline against which the working electrode's potential is measured. |

| Nafion Binder | A common ionomer used to bind catalyst particles to the electrode substrate and facilitate proton transport. |

| High-Surface-Area Carbon Supports | Materials like Vulcan XC-72R used to disperse catalyst nanoparticles, increase electrical conductivity, and maximize the electrochemically active surface area. |

| Dopant Precursors | Chemical compounds (e.g., metal salts or heteroatom sources) used to introduce dopants into a catalyst matrix to modulate its electronic structure and improve activity. |

FAQs on Synthesis Feasibility Research

What is the core challenge in modern computational materials design? A significant challenge is the "generation-synthesis gap," where most computationally designed molecules cannot be synthesized in a laboratory. This limits the practical application of AI-assisted drug and material design. The core issue is that many models prioritize predicted performance (e.g., hole mobility, binding affinity) over synthetic feasibility, leading to brilliant theoretical designs that are impractical to make [10].

How can researchers rapidly identify active compounds from vast chemical libraries? Ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) allows for the testing of over 100,000 compounds per day. This method uses robotics, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors to conduct millions of tests quickly. By using assay plates with hundreds to thousands of wells, researchers can screen ultra-large "make-on-demand" virtual libraries containing billions of compounds to recognize active agents, or "hits" [11] [12] [13].

What methods exist to assess synthetic feasibility before starting lab work? Two main computational approaches are:

- Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) Tools: These perform retrosynthetic searches to propose viable synthesis routes. They are computationally expensive but detailed [14] [10].

- Machine Learning-based SA Prediction Models: These provide rapid, sub-second scoring of a molecule's synthesizability. Tools like SynFrag use fragment assembly patterns to learn synthesis logic and identify "synthesis difficulty cliffs," where minor structural changes drastically alter feasibility [10].

How can I design a peptide therapeutic with improved stability and bioavailability? Incorporating non-natural amino acids (NNAAs) into peptides is a common strategy. However, this introduces synthesis challenges. A first-of-its-kind tool called NNAA-Synth can assist by planning synthesis routes, selecting optimal orthogonal protecting groups (e.g., Fmoc for the backbone amine, tBu for the carboxylic acid), and scoring the synthetic feasibility of individual NNAAs to ensure they are SPPS-compatible [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Recurring Synthesis Failure for AI-Designed Molecules

Problem Description: Molecules generated by deep learning models, while theoretically high-performing, consistently fail during lab-scale synthesis due to complex or non-viable reaction pathways.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score: Use a rapid ML-based predictor like SynFrag to get an initial SA score. A low score indicates high synthesis difficulty [10].

- Perform Retrosynthetic Analysis: Input the failing molecule into a CASP tool. The inability to generate a plausible retrosynthetic pathway with available starting materials confirms the diagnosis [14] [10].

- Analyze Structural Motifs: Identify uncommon ring systems, unstable functional groups, or stereochemical complexity that pose synthesis barriers.

Solution: Integrate synthesizability assessment directly into the generative AI pipeline. Use SA scoring as a filter or optimization objective during the molecular generation process. Tools like CMD-GEN, a structure-based generation framework, can incorporate drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility conditions to steer the model toward more feasible compounds [15].

Problem: Inconsistent Results in High-Throughput Functional Screening

Problem Description: High background noise or low signal differentiation in HTS leads to unreliable "hit" identification from primary biopsies or cell lines.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Calculate Z-Factor: This is a key quality control metric for HTS assays. A Z-factor between 0.5 and 1.0 indicates an excellent assay, while a value below 0.5 suggests marginal to no separation between positive and negative controls, leading to unreliable results [13].

- Review Plate Design: Check for systematic errors linked to well position (e.g., edge effects). A poor plate design can introduce bias [13].

- Confirm Control Effectiveness: Ensure that positive and negative controls are performing as expected and are clearly distinguishable [11] [13].

Solution: Optimize the assay protocol to improve the signal-to-background ratio. This may involve:

- Adjusting cell seeding density or incubation times.

- Titrating antibody concentrations for detection.

- Implementing robust statistical methods for hit selection, such as the z*-score or B-score, which are less sensitive to outliers [13]. As demonstrated in functional screening of melanoma biopsies, a well-optimized assay with effective QC is critical for identifying patient-specific drug combinations [11].

Problem: Low Conversion Rate in Enzymatic Synthesis

Problem Description: The yield for an enzymatic synthesis reaction, such as the acylation of a natural compound, is prohibitively low for industrial application.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Evaluate Enzyme Selection: Different immobilized enzymes (e.g., Novozym 435, Lipozyme TL IM) have varying activities and selectivities for different substrates and solvents [16].

- Identify Solvent Toxicity: Class 2 solvents with high toxicity (e.g., pyridine, tetrahydrofuran) can inhibit enzyme activity and are unsuitable for food or pharmaceutical applications [16].

- Analyze Reaction Parameters: Determine if the molar ratio of substrates, enzyme concentration, or temperature are suboptimal [16].

Solution: Systematically optimize the reaction conditions. A techno-economic analysis of enzymatic puerarin myristate synthesis found that using low-toxicity solvents like tert-butanol and myristic anhydride as an acyl donor, with Novozym 435 as the catalyst, dramatically increased conversion to over 97% [16]. The table below summarizes the key parameters to troubleshoot.

Table: Key Parameters for Troubleshooting Enzymatic Synthesis

| Parameter | Common Issue | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Type | Low activity/selectivity for substrate | Screen immobilized enzymes (e.g., Novozym 435, Lipozyme TL IM) [16]. |

| Solvent | Toxicity inhibits enzyme & product use | Switch to low-toxicity solvents (e.g., tert-butanol, acetone) [16]. |

| Acyl Donor | Low conversion efficiency | Use anhydrides over esters (e.g., myristic anhydride) [16]. |

| Molar Ratio | Imbalanced stoichiometry | Increase acyl donor to substrate ratio (e.g., 1:20) [16]. |

| Enzyme Loading | Insufficient catalyst | Increase concentration (e.g., 15 g/L) [16]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and software tools essential for conducting synthesis feasibility research.

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for Synthesis Feasibility Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Novozym 435 | Immobilized lipase enzyme for regioselective enzymatic acylation and synthesis. | Candida antarctica Lipase B immobilized on acrylic resin [16]. |

| Lipozyme TL IM | Immobilized lipase enzyme for enzymatic synthesis. | Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase immobilized on a silica gel carrier [16]. |

| Fmoc-Protected NNAAs | Building blocks for Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) requiring orthogonal protection. | Provides backbone amine protection, removable with a base like piperidine [14]. |

| tBu-Protected NNAAs | Building blocks for SPPS requiring orthogonal protection. | Provides carboxylic acid protection, removable with strong acid like TFA [14]. |

| NNAA-Synth Software | Plans & evaluates synthesis routes for non-natural amino acids, including protection groups. | Integrates retrosynthetic prediction with deep learning-based feasibility scoring [14]. |

| SynFrag Platform | Predicts synthetic accessibility (SA) of molecules via fragment assembly generation. | Provides rapid, interpretable SA scores for high-throughput screening in drug discovery [10]. |

| CMD-GEN Framework | A structure-based deep generative model for designing active, drug-like molecules. | Uses coarse-grained pharmacophore points to bridge protein-ligand complexes with synthesizable molecules [15]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

High-Throughput Screening to Validation

This diagram illustrates the core workflow for identifying active compounds through functional screening and validating them in vivo.

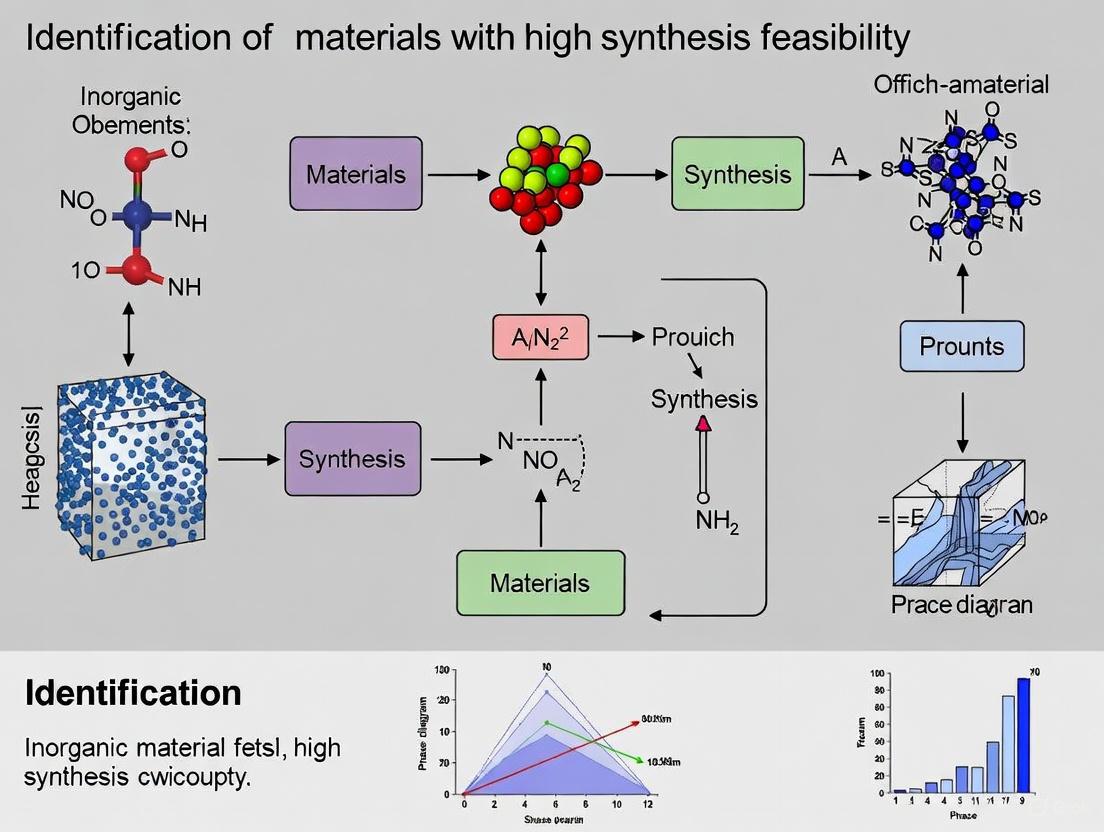

Synthesis Feasibility Assessment Pipeline

This diagram outlines the integrated computational and experimental pipeline for ensuring newly designed materials or drugs are synthesizable.

The Critical Role of Formation Energy and Decomposition Pathways

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common challenges in predicting material stability and synthesis feasibility, crucial for research in drug development and material science.

Formation Energy and Stability

FAQ: How can I quickly predict if a newly designed material is thermodynamically stable? The formation energy of a compound is a primary indicator of its thermodynamic stability. A material is generally considered stable if its calculated formation energy lies on or below the convex hull of formation energies for all other possible phases of its constituent elements. A positive formation energy often indicates instability, while a negative value suggests a stable compound. Metastable materials, which can be synthesized under specific conditions, may have formation energies slightly above this hull [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Discrepancies between predicted and experimental stability.

- Problem: A material predicted to be stable decomposes during synthesis.

- Investigation Checklist:

- Check for Polymorphs: Verify if the material has multiple crystal structures (polymorphs). Your synthesis might be producing a different, less stable polymorph than the one modeled. Using space group symmetry as an input feature in predictive models significantly improves accuracy [17].

- Review Synthesis Conditions: The model predicts thermodynamic stability, but kinetic barriers controlled by your specific synthesis conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure) dictate whether the stable phase is actually formed.

- Verify Model Inputs: Ensure the deep learning model used for prediction was trained on data relevant to your material class. Models using only chemical formula may miss structural stability variations [17].

Decomposition Pathways

FAQ: Why is understanding the decomposition pathway important for material design? Identifying the specific chemical route a material takes when it breaks down allows researchers to design more robust compounds. By understanding the weak points in a molecular structure, chemists can strategically modify it to block or slow the primary decomposition mechanisms, thereby enhancing the material's operational lifetime and safety [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Unexpected decomposition during application.

- Problem: A functional material (e.g., a redox-active molecule in a battery) loses performance due to decomposition.

- Investigation Checklist:

- Identify Fragmentation Patterns: Use analytical techniques (e.g., mass spectrometry) to identify the decomposition products. For instance, a molecule may undergo desulfonation or hydrogenation of aromatic rings [18].

- Analyze Operational Stresses: Correlate the decomposition products with operational conditions, such as applied potential, pH, or temperature, to pinpoint the trigger.

- Implement Structural Mitigation: Once the pathway is known, redesign the molecule to prevent it. For example, in phenazine-based systems, moving a hydroxyl group from the 2,7-positions to the 1,4-positions can prevent irreversible tautomerization, a common decomposition trigger [18].

Synthesis Feasibility

FAQ: How can I evaluate the synthesis feasibility of a novel non-natural amino acid (NAA) for peptide therapeutics?

Bridging in silico design to actual synthesis requires integrated tools that consider protection groups and reaction pathways. Tools like NNAA-Synth assist by [14]:

- Identifying Reactive Groups: Systematically scanning the NAA structure for functional groups that require protection.

- Planning Orthogonal Protection: Assigning protecting groups (e.g., Fmoc for the backbone amine, tBu for the backbone acid) that can be removed selectively without affecting others.

- Scoring Synthetic Routes: Using deep learning to evaluate the feasibility of proposed retrosynthetic pathways for the protected NAA.

Troubleshooting Guide: Low yield during the synthesis of a protected building block.

- Problem: The synthetic route for an SPPS-compatible NAA is inefficient.

- Investigation Checklist:

- Re-evaluate Protection Strategy: The chosen set of protecting groups (e.g., Fmoc/tBu) may not be fully orthogonal under your specific reaction conditions, leading to premature deprotection or side reactions [14].

- Analyze Route Complexity: Use a synthetic feasibility tool to score alternative retrosynthetic pathways. A simpler route with more available starting materials may exist.

- Check Compatibility: Ensure that all protecting groups are stable to the reagents used in your synthesis sequence and are ultimately cleavable under conditions that will not damage the final product [14].

Quantitative Data and Descriptors

The following parameters are critical for computational and experimental characterization of new materials.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical and Performance Parameters for Energetic Materials [19]

| Parameter | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Density | Mass per unit volume. | Directly influences detonation performance. |

| Heat of Formation | Energy change when a compound is formed from its elements. | A higher positive value contributes to greater energy content. |

| Detonation Velocity | Speed of the detonation wave through the material. | Key metric for explosive performance. |

| Detonation Pressure | Pressure at the front of the detonation wave. | Key metric for explosive performance and brisance. |

| Impact Sensitivity | Measure of the likelihood of initiation by impact. | Critical safety parameter (lower is safer). |

| Friction Sensitivity | Measure of the likelihood of initiation by friction. | Critical safety parameter (lower is safer). |

| Thermal Stability | The decomposition temperature of the material. | Indicates safe handling and storage temperature range. |

Table 2: Key Descriptors for Computational Workflows [20] [17]

| Descriptor | Description | Role in Feasibility |

|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy | Energy of a compound relative to its constituent elements. | Primary metric for thermodynamic stability. |

| Energy Above Hull | Energy relative to the most stable phase configuration. | Identifies stable and metastable compounds; a value of 0 indicates the most stable phase. |

| Space Group | Crystallographic classification defining symmetry. | Critical input feature for accurate formation energy prediction, accounting for polymorphs [17]. |

| Surface Structure Geometry | The shape and atomic arrangement of a crystal surface. | Determines the feasibility of forming intergrowth structures between different zeolites [20]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Deep Learning Model for Predicting Formation Energy from Composition and Symmetry

This methodology accelerates the initial screening of material stability [17].

1. Data Preprocessing

- Input Features:

- Elemental Fractions: From the chemical formula, create a vector of 86 columns, one for each element in the periodic table that forms stable materials. The values are the fractional composition of each element in the compound.

- Symmetry Classification: Obtain the crystal's space group, point group, or crystal system from a database (e.g., Materials Project). Convert this categorical data into a binary format using one-hot encoding (e.g., 228 columns for space groups).

- Data Cleaning: Remove data points where the formation energy value is an extreme outlier (e.g., beyond ±7 standard deviations from the mean).

2. Deep Learning Architecture and Training

- Model Structure: A sequential neural network with the following layers:

- Hidden Layer 1: 512 neurons, ReLU activation

- Hidden Layer 2: 512 neurons, ReLU activation

- Hidden Layer 3: 256 neurons, ReLU activation

- Hidden Layer 4: 128 neurons, ReLU activation

- Hidden Layer 5: 64 neurons, ReLU activation

- Hidden Layer 6: 32 neurons, ReLU activation

- Output Layer: 1 neuron, Linear activation (for regression)

- Training Configuration:

- Optimizer: Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation).

- Early Stopping: Implemented with a patience of 10 epochs to prevent overfitting.

- Data Split: 80% of data for training, 20% for testing.

3. Model Evaluation

- Evaluate the model's performance on the test set using metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R-squared (R²) to assess predictive confidence [17].

Protocol 2: Mapping Decomposition Pathways for Redox-Active Molecules

This protocol outlines steps to identify degradation mechanisms in functional molecules, such as battery anolytes [18].

1. Cycling and Sample Collection

- Subject the material (e.g., an organic anolyte) to extended operational cycling in its application environment (e.g., a flow battery).

- Periodically collect samples from the system for analysis.

2. Identification of Decomposition Products

- Use analytical techniques like mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to identify and quantify the chemical species formed during decomposition.

- Example: For a molecule like 7,8-dihydroxyphenazine-2-sulfonic acid (DHPS), key products might include desulfonated species and ring-hydrogenated derivatives [18].

3. Computational Analysis with Density Functional Theory (DFT)

- Model the charged state of the parent molecule and its proposed decomposition products.

- Calculate the reaction energies and pathways for suspected degradation mechanisms, such as irreversible hydrogen rearrangement (tautomerization) or bond cleavage.

4. Mitigation via Structural Design

- Use the insights from DFT to guide the redesign of the molecular core.

- Example: For dihydroxyphenazines, computational analysis shows that hydroxyl groups at the 1,4,6,9-positions yield stable derivatives, while those at the 2,3,7,8-positions lead to unstable compounds. Synthesize and test the stable isomers [18].

Research Workflow Visualization

Stability and Synthesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Non-Natural Amino Acid Synthesis and Protection [14]

| Reagent / Protecting Group | Function / Role in Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Fmoc-Cl (Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl chloride) | Used to protect the backbone amino group (-NH₂). It is removable under basic conditions (e.g., piperidine), making it orthogonal to acid-labile groups. |

| tBu (tert-Butyl esters) | Used to protect the backbone carboxylic acid (-COOH). It is cleaved by strong acids like trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). |

| Bn (Benzyl) / 2ClZ (2-Chlorobenzyloxycarbonyl) | Used to protect sidechain acids, alcohols, or amines. These groups are removed by hydrogenolysis, providing orthogonality to both acid and base labile protections. |

| PMB (p-Methoxybenzyl) | Used to protect sidechain hydroxyls or thiols. It is cleaved oxidatively (e.g., with DDQ), offering another orthogonal deprotection strategy. |

| TMSE (Trimethylsilyl-ethyl) | Used to protect sidechain acids or alcohols. It is selectively removed with fluoride ions (e.g., TBAF), stable to other deprotection conditions. |

| NNAA-Synth Tool | A cheminformatics tool that integrates protection group assignment, retrosynthetic planning, and deep learning-based feasibility scoring to streamline the synthesis of protected NAAs [14]. |

The table below summarizes the primary methods used for the synthesis of inorganic materials, helping researchers select the appropriate technique based on their target material's requirements.

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Key Application Examples | Critical Parameters | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-State & High-Temperature [21] | Traditional Solid-State Reaction | Ceramics, Metal oxides, Superconductors | Temperature (500-2000°C), Grinding cycles, Reactant surface area [21] | Simplicity, Yields thermodynamically stable products [21] | Slow diffusion, Potential for incomplete reactions, Irregular particle size/shape [21] [22] |

| Solid-State & High-Temperature [21] | Flux Method | Single crystals, Metastable phases | Molten salt/metal medium, Reaction temperature [21] | Lower reaction temperature, Improved diffusion [21] | Use of a flux medium required |

| Solid-State & High-Temperature [21] [2] | Chemical Vapour Deposition (CVD) | Semiconductor thin films, Optical coatings | Precursor gas composition, Substrate temperature, Chamber pressure [21] | High-purity, uniform coatings [21] | Complex equipment and gas handling |

| Solid-State & High-Temperature [2] | High-Pressure Synthesis | High-Tc superconductors, Super-hard nano-diamonds | Applied pressure, Temperature [2] | Access to unprecedented novel materials [2] | Requires specialized high-pressure equipment |

| Solution-Based [21] | Sol-Gel Method | Glasses, Ceramics, Hybrid materials | Precursor chemistry, pH, Temperature, Gelation time [21] | Low processing temperatures, Porous materials [21] | Potential for shrinkage during drying |

| Solution-Based [21] | Hydrothermal/Solvothermal | Zeolites, Quartz crystals, Nanomaterials | Solvent type, Temperature (>100°C), Pressure (autoclave) [21] | Forms materials difficult to synthesize by other methods [21] | Requires sealed pressure vessels |

| Solution-Based [21] | Precipitation | Nanoparticles, Phosphors, Catalysts | Concentration, Temperature, pH, Addition rate [21] | Good for nanoparticle synthesis | Control over particle size distribution can be challenging |

| Energy-Assisted [21] | Electrochemical Synthesis | Metals, Alloys, Conductive polymers | Electrode potential, Current density, Electrolyte [21] | Synthesizes materials difficult to produce by other methods [21] | Requires electrode setup and conductivity |

| Energy-Assisted [21] | Mechanochemical | Alloys, Composites, Nanomaterials | Milling type, Duration, Energy input [21] | Forms metastable phases, Nanostructured materials [21] | Potential for contamination from milling media |

| Energy-Assisted [21] [23] | Microwave-Assisted | Nanoparticles, MOFs, Hybrids | Microwave power, Solvent, Reaction time [21] | Rapid, uniform heating, Energy efficient [21] | Requires specialized microwave reactors |

| Energy-Assisted [23] | Gamma Irradiation | Metallic nanoparticles, Nanocomposites | Radiation dose, Radical scavengers (e.g., isopropanol) [23] | Room temperature/pressure, High purity, No reducing agents [23] | Potential for radioactivity if neutron exposure occurs [23] |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My solid-state reaction is incomplete, yielding a mixture of products even after prolonged heating. What should I do?

A: This is a common limitation due to slow solid-state diffusion [21]. To overcome this:

- Increase Reactant Contact: Perform intermediate grinding and re-pelletizing between heating cycles to refresh interfaces and improve homogeneity [21].

- Optimize Temperature: Ensure the furnace temperature is high enough to facilitate diffusion but not so high as to cause decomposition or melting. Temperatures often range from 500°C to 2000°C [21].

- Consider Alternative Methods: If the product remains elusive, switch to a method that enhances diffusion, such as a flux technique (using a molten salt medium) or a solution-based method like sol-gel or hydrothermal synthesis [21].

Q2: I am trying to synthesize a metastable material, but it consistently converts to the thermodynamically stable phase. How can I kinetically trap the desired phase?

A: Synthesizing metastable phases requires bypassing the most stable free energy minimum. Conventional solid-state reactions typically yield the most stable phase [22]. Recommended approaches are:

- Use Low-Temperature Paths: Employ solution-based methods (e.g., precipitation) or energy-assisted techniques (e.g., microwave, mechanochemical). These methods provide rapid nucleation and shorter reaction times, favoring the formation of kinetically stable products [21] [22].

- Apply High Pressure: High-pressure synthesis is a powerful tool for creating metastable phases that can remain in a metastable state even at ambient conditions after synthesis [2].

- Leverage Computational Guidance: Use computational models to screen the energy landscape and identify potential synthesis pathways that avoid the stable phase [22].

Q3: When synthesizing nanoparticles via a precipitation route, I struggle with controlling their size and achieving a narrow size distribution. What factors are most critical?

A: In fluid-phase synthesis, the separation of nucleation and growth stages is key to achieving monodisperse particles [22].

- Control Nucleation: Rapidly mix the reactants to create a single, "burst" of nucleation events. This ensures all nuclei start growing at approximately the same time [22].

- Manage Growth: After the initial nucleation, control the subsequent growth phase by carefully regulating parameters like temperature, concentration, and pH. Adding surfactants or capping agents can also help control growth and prevent agglomeration [21].

- Consider Hydrothermal Methods: These techniques provide a uniform reaction environment (high temperature and pressure in an autoclave), which is excellent for growing uniform crystals [21].

Q4: My gamma irradiation synthesis of metal nanoparticles is leading to radioactive products. How can this be prevented?

A: Radioactivity is caused by neutron absorption reactions, not gamma rays themselves [23].

- Shield from Neutrons: When using a research reactor as an irradiation source, design a shielding cell (e.g., using borated polyethylene with a cadmium inner wall) around your sample. This removes thermal neutrons, which have high absorption cross-sections, while allowing gamma rays to pass through and initiate the reduction reaction [23].

- Use Pure Gamma Sources: If available, use a gamma cell with a radioactive 60Co source, which primarily emits gamma radiation without a significant neutron flux [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conventional Solid-State Synthesis of a Mixed Metal Oxide

Principle: Direct reaction between solid precursors at high temperatures to form a new crystalline phase [21].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Weigh out high-purity solid reactants (typically metal carbonates or oxides) in the correct stoichiometric ratio. A 1-5% excess of a volatile component may be added to compensate for potential loss during heating.

- Grinding and Mixing: Transfer the powder mixture to an agate mortar and pestle or a ball mill. Grind thoroughly for 30-45 minutes to achieve a homogeneous mixture and increase surface area for reaction.

- Pelletizing (Optional): Press the ground powder into a pellet using a hydraulic press. This increases inter-particle contact and reduces the presence of air pockets.

- First Heat Treatment: Place the pellet or powder in a suitable crucible (e.g., alumina, platinum) and transfer it to a furnace. Heat at a controlled ramp rate (e.g., 3-5°C/min) to the target calcination temperature (e.g., 800-1400°C, depending on the system). Hold at this temperature for 6-24 hours.

- Intermediate Grinding: After the first heating cycle, allow the sample to cool to room temperature inside the furnace. Carefully remove and grind it again into a fine powder to expose fresh surfaces and ensure homogeneity.

- Second Heat Treatment: Re-pelletize the ground powder and subject it to a second heating cycle, often at the same or a slightly higher temperature, for another 6-24 hours.

- Cooling and Storage: After the final heating, cool the sample to room temperature slowly. Store the final product in a desiccator [21].

Troubleshooting Tip: If reaction completion is slow, consider using a mineralizer (e.g., a small amount of volatile halide) or increase the number of grinding and heating cycles [21].

Protocol 2: Sol-Gel Synthesis of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles

Principle: Formation of an inorganic network through the hydrolysis and condensation of molecular precursors in a liquid medium [21].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve a metal alkoxide precursor (e.g., tetraethyl orthosilicate for SiO2) in a parent alcohol (e.g., ethanol) under vigorous stirring.

- Catalysis and Hydrolysis: Add a mixture of water and a catalyst (typically an acid like HCl or a base like NH4OH) dropwise to the solution. The acid or base catalyst controls the rates of hydrolysis and condensation, affecting the pore structure and particle size.

- Gelation: Continue stirring until the solution becomes viscous and eventually forms a wet gel. This process can take from minutes to hours.

- Aging: Allow the gel to age for 24 hours to strengthen its network.

- Drying: Dry the gel slowly at ambient temperature or in an oven at slightly elevated temperatures (e.g., 60-80°C) to remove the solvent, resulting in a xerogel. For a highly porous aerogel, supercritical drying is required.

- Calcination: Finally, heat the dried gel in a furnace at 400-600°C to remove organic residues and crystallize the metal oxide nanoparticles [21].

Troubleshooting Tip: Rapid hydrolysis can lead to precipitation instead of gelation. Control the rate of water addition and the strength of the catalyst to manage the process [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents and materials frequently used in inorganic synthesis, along with their core functions.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Metal Oxides/Carbonates | Common solid-state precursors for ceramics and mixed metal oxides [21]. |

| Metal Alkoxides | Common molecular precursors for sol-gel synthesis (e.g., TEOS for SiO2) [21]. |

| Flux Agents (e.g., NaCl, PbO) | Molten media in flux methods to enhance diffusion and crystal growth at lower temperatures [21]. |

| Structure-Directing Agents (e.g., Quaternary Ammonium Salts) | Templates for creating porous materials like zeolites during hydrothermal synthesis [21]. |

| Surfactants & Capping Agents (e.g., CTAB, PVP) | Control nucleation, growth, and agglomeration during nanoparticle synthesis in solution [21]. |

| Reducing Agents (e.g., NaBH4) | Chemically reduce metal ions to form metallic nanoparticles in precipitation methods. Note: Not required in gamma irradiation [23]. |

| Radical Scavengers (e.g., Isopropanol) | Scavenge OH• and H• radicals in gamma irradiation synthesis to control reduction reactions and prevent unwanted side products [23]. |

Synthesis Feasibility Workflow

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for identifying materials with high synthesis feasibility, integrating traditional and modern data-driven approaches.

Advanced Synthesis Methods and Machine Learning Applications

FAQs: High-Pressure and High-Temperature Synthesis

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using HPHT synthesis in materials research?

HPHT synthesis is a powerful method for creating materials with unique properties that are not achievable under ambient conditions. The application of high pressure effectively decreases atomic volume and increases the electronic density of reactants, which can lead to the formation of new chemical bonds and structural transformations [24]. This technique is crucial for producing superhard materials like diamond and cubic boron nitride, discovering new superconducting materials with enhanced critical temperatures, and synthesizing nanomaterials with exotic phases [25] [24] [26]. For instance, high pressure has been used to stabilize high-temperature superconducting phases in iron-based superconductors and to enhance the critical current density in materials like MgB₂ [24] [26].

Q2: What are the main types of high-pressure apparatus available, and how do I choose?

The choice of apparatus depends on your target pressure, sample volume, and required sample quality. The main technologies are compared below [25] [24] [26]:

| Apparatus Type | Typical Pressure Range | Sample Volume | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piston-Cylinder | Up to 3 GPa | 1 - 1000 cm³ | Large sample volume; suitable for a wide range of syntheses [24]. |

| Bridgman Anvil | 15 - 300 GPa | Very small | Very high pressures; hard alloy (15-20 GPa), SiC (20-70 GPa), or diamond anvils (100-300 GPa) [24]. |

| Multi-Anvil Press (e.g., Walker-type) | Over 5 GPa | ~1 cm³ | Industrially scalable for superhard materials; used for catalyst-free diamond synthesis [27] [24]. |

| Gas Pressure Technique (HP-HTS) | Up to 3 GPa | 10 - 15 cm³ | Large, high-quality samples; homogeneous temperature/pressure; avoids contamination [26]. |

| Shock Wave (Dynamic) | 10 - 1000 GPa | 1 - 10 cm³ | Very high pressures for short durations (nanoseconds) [24]. |

Q3: My HPHT synthesis yielded a product with unintended phases or poor purity. What could be the cause?

Contamination is a common issue. In solid-medium pressure systems, physical interactions between the sample and the instrument parts (e.g., anvils, pressure-transmitting medium) can introduce impurities that compromise the final product [26]. Another cause could be the evaporation of lighter elements from the sample, which can be controlled by using a high-gas pressure technique that creates a confined environment [26]. Furthermore, if the pressure and temperature distribution within the reaction chamber is not homogeneous, it can lead to undefined preparation conditions and inconsistent results. The high-gas pressure technique is noted for its ability to provide homogeneous conditions [26].

Q4: During my experiment, I cannot reach the target pressure. What should I check?

This problem can originate from several parts of the system. You should investigate the following [28]:

- Gas Leaks: Check all seals and gaskets for damage or improper installation. Replace them if they are aging or deformed.

- Insufficient Gas Source: Verify that the gas source pressure meets the requirements and check the gas lines and valves for blockages or leaks.

- Valve Malfunction: Valves may become stuck due to long-term use, rust, or internal debris. They should be checked, cleaned, or replaced.

- Piston/Compressor Issues: In gas systems, ensure the multi-stage pistons of the compressor are functioning correctly to build pressure progressively [26].

Q5: How can I safely cool down my system and handle the synthesized material after an HPHT experiment?

Improper cooling can cause thermal shock, leading to cracks in the synthesized material or damage to the equipment. It is crucial to follow a controlled cooling rate as specified for your apparatus and material [28]. If the cooling system itself fails, it can cause dangerously high temperatures; always check that the coolant flow is sufficient and the system is free of blockages [28]. After the run, be aware that some synthesized phases are metastable and may not be retained upon decompression to ambient pressure. Ensure you understand the phase stability of your target material [24].

Troubleshooting Common HPHT Experimental Issues

Sealing and Leakage Problems

Gas leakage compromises pressure build-up and can contaminate the sample.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Gas pressure cannot reach the expected value. | Damaged or improperly installed sealing gasket. | Inspect seals regularly; replace if aged or damaged; ensure proper installation per manufacturer's instructions [28]. |

| Leaking threaded connections. | Ensure all threaded connections are tight; apply a suitable sealant; replace damaged threaded parts [28]. |

Pressure and Temperature Instability

Failure to achieve or maintain target conditions directly impacts reaction outcomes.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure sensor readings are inaccurate or control system fails. | Sensor or control system failure. | Check and calibrate pressure sensors; inspect control system circuits and software; contact technical support if needed [28]. |

| Temperature cannot reach the set value. | Heating system failure. | Check and repair heating elements; verify and adjust heating rate and temperature settings [28]. |

| Unintended pressure drop during reaction. | Leakage (see above) or material clogging. | Check for leaks. Also, inspect valves and pipelines for blockages from solid materials or high-viscosity liquids; clean regularly [28]. |

Product Quality and Synthesis Issues

Common problems related to the final synthesized material.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unintended phases or impurities in the final product. | Contamination from the pressure medium or sample evaporation. | Use a high-gas pressure technique to avoid contact with solid media and control evaporation of light elements [26]. |

| Metallic inclusions in synthesized diamonds. | Use of metal catalyst (Fe, Ni, Co) in HPHT growth. | To avoid inclusions that compromise optical/electrical properties, use a catalyst-free HPHT process at higher pressures (e.g., 15 GPa) [27] [29]. |

| Poor densification or sintering of the product. | Insufficient pressure and temperature for mass transport. | Increase pressure to enhance densification rate, as pressure reduces diffusion distances between particles [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Catalyst-Free Diamond Synthesis from BaCO₃

This protocol outlines the direct conversion of BaCO₃ to micron-sized diamond using a hexahedral multi-anvil press, a method relevant for utilizing radioactive carbon-14 from nuclear waste [27].

1. Principle: The process subjects BaCO₃ precursor powder to extreme conditions of 15 GPa and 2300 K (≈2027°C). Under these conditions, the carbonate decomposes, and carbon rearranges into the diamond lattice without the use of metal catalysts, preventing metallic contamination [27].

2. Equipment and Reagents:

- Apparatus: Self-designed hexahedral multi-anvil press with a two-stage pressure chamber system [27].

- Precursor: High-purity, rhombohedral BaCO₃ powder (particle size: 300 nm - 4 μm) [27].

- Pressure Medium: Positive octahedral pressure-transmitting medium [27].

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Loading: Place the BaCO₃ precursor powder into the pressure chamber assembly.

- Compression: Increase the pressure to the target of 15 GPa.

- Heating: While maintaining pressure, raise the temperature to 2300 K.

- Reaction: Hold the high-pressure and high-temperature conditions for a defined period to allow for diamond crystallization.

- Quenching: Cool the sample to room temperature.

- Decompression: Slowly release the pressure to ambient conditions.

- Recovery: Retrieve the synthesized product for analysis [27].

4. Characterization:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Confirm diamond formation by identifying distinct diffraction peaks at approximately 44°, 76°, and 91.6° [27].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Verify the presence of sp³-bonded carbon by detecting the characteristic diamond peak at 1333.2 cm⁻¹ [27].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Analyze the morphology and confirm the presence of micron-sized diamond crystals [27].

Protocol: High Gas Pressure and High-Temperature Synthesis (HP-HTS) of Superconductors

This protocol uses a high-purity gas pressure system, ideal for growing large, high-quality crystals of complex materials like iron-based superconductors (FBS) with minimal contamination [26].

1. Principle: An inert gas (e.g., argon) is compressed to gigapascal-level pressures using a multi-stage piston compressor. This high-pressure gas environment suppresses the evaporation of volatile elements and allows for homogeneous crystal growth at high temperatures within a large sample volume [26].

2. Equipment and Reagents:

- Apparatus: HP-HTS system with a reciprocating compressor, high-pressure chamber, and an internal multi-zone furnace.

- Gas: Highly pure inert gas.

- Precursors: High-purity starting materials (e.g., metals, oxides) for the target superconductor.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Loading: Seal the precursor mixture in a suitable ampoule and place it in the sample holder inside the pressure chamber.

- Gas Filling: Open the gas bottle to fill the chamber and piston cavities to an initial pressure (e.g., 200 bar).

- 1st Stage Compression: Close the intake valve (Vi) and use the first-stage piston (S1) to increase the pressure to ~800 bar.

- 2nd Stage Compression: Close the Vi between S1 and S2, and use the second-stage piston (S2) to increase pressure to ~4000 bar.

- 3rd Stage Compression: Close the Vi between S2 and S3, and use the third-stage piston (S3) to reach the final synthesis pressure (up to 1.8 GPa).

- Heating & Synthesis: Heat the sample to the target temperature (up to 1700 °C) using the multi-zone furnace and maintain the conditions for the required reaction time.

- Cooling & Decompression: After synthesis, cool the system and then slowly release the gas pressure [26].

4. Characterization: Enhanced superconducting properties are typically confirmed by measuring:

- Critical Temperature (T_c): The temperature where electrical resistance drops to zero.

- Critical Current Density (J_c): The maximum current a superconductor can carry without resistance.

- Sample quality is assessed using XRD for phase purity and SEM for microstructure [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Metal Catalysts (Fe, Ni, Co) | Solvents/catalysts in traditional HPHT diamond growth; lower the required temperature and pressure for graphite-to-diamond conversion [29]. |

| High-Purity Carbon Sources (Graphite, BaCO₃) | Carbon precursors. Graphite is common, while BaCO₃ is used for specific pathways, such as direct conversion for diamond battery technology [27] [29]. |

| Boron Dopant | Added during HPHT diamond growth to create p-type semiconducting blue diamonds [29]. |

| Pressure Transmitting Media (e.g., Octahedral MgO) | Encapsulates the sample in multi-anvil presses to ensure hydrostatic (uniform) pressure distribution during synthesis [27]. |

| Sealing Gaskets | Critical components in autoclaves and pressure chambers to maintain a gas-tight seal and prevent leaks under extreme conditions [28]. |

| Hydrocarbon Gas (e.g., Methane) | Serves as the carbon source in Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) diamond growth, where it decomposes in a plasma to deposit carbon on a substrate [29]. |

Experimental Workflow and System Diagrams

HPHT Synthesis General Workflow

High Gas Pressure System Diagram

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is the primary advantage of hydrothermal synthesis? | It is a cost-effective and scalable solution-based method allowing precise control over morphology and phase purity of nanomaterials at relatively low temperatures [30]. |

| Why is controlled nucleation critical? | Uncontrolled, stochastic nucleation leads to heterogeneous product quality, inconsistent drying rates, and can compromise the yield and activity of sensitive biologics [31]. |

| My VS2 nanosheets are impure. What should I check? | Systematically optimize precursor molar ratio (NH4VO3:TAA), reaction temperature, and ammonia concentration. Pure phase VS2 can be achieved in 5 hours with correct parameters [30]. |

| How can I improve the monodispersity of my spherical Al2O3 powder? | Control the hydrothermal reaction temperature and precursor concentration to direct the nucleation and growth of uniform spherical precursors before calcination [32]. |

| What is an inert alternative to metal reactors for hydrothermal experiments? | Quartz or fused silica glass tubes are cost-effective and highly inert, minimizing unwanted catalytic effects in organic-mineral hydrothermal interactions [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Morphology and Phase Purity

Issue: The final product has inconsistent shape, size, or contains undesired crystalline phases.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Supporting Data / Protocol Step |

|---|---|---|

| Unoptimized precursor ratio and concentration | Systematically vary molar ratios. For VS2, test NH4VO3:TAA ratios of 1:2.5, 1:5, 1:7.5, and 3:5 [30]. | Precursor concentration should be controlled; for spherical Al2O3, Al³⁺ concentration was precisely maintained at 0.02 mol/L [32]. |

| Incorrect reaction temperature | Optimize temperature profile. VS2 growth was studied at 100°C, 140°C, 180°C, and 220°C [30]. | Phase transformation in Al2O3 during calcination is temperature-dependent; α-Al2O3 forms efficiently at high temperatures [32]. |

| Uncontrolled nucleation | Implement methods to control the nucleation event. For lyophilization, pressure manipulation can induce uniform nucleation; similar principles can apply to hydrothermal systems [31]. | Uncontrolled nucleation causes vial-to-vial heterogeneity in freezing and drying characteristics, directly impacting final product attributes [31]. |

Problem 2: Low Yield and Poor Product Recovery

Issue: The amount of final product is lower than expected, or recovery from the solution is inefficient.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Supporting Data / Protocol Step |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or excessive reaction time | Determine the minimum time for phase purity. VS2 nanosheets can be synthesized in 5 hours, much less than the conventional 20 hours [30]. | For organic-mineral experiments, a 2-hour reaction at 150°C was sufficient to show significant mineral-catalyzed conversion [33]. |

| Inefficient product extraction | Ensure thorough washing and extraction steps. Use multiple solvents and sonication for better recovery [33]. | After hydrothermal reaction, products were extracted with dichloromethane, vortexed for 1 min, and sonicated for samples with high mineral content [33]. |

| Precursor reactivity and stability | Design molecular precursors with controlled reactivity. For HfBCN ceramics, modifying the molecular structure stabilized the metal center and improved processability [34]. | The designed Hf-N-B molecular framework reduced the reactivity of the hafnium central atom, leading to a better ceramic yield of 53.07 wt% [34]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Hydrothermal Synthesis in Silica Tubes

This protocol is adapted for studying organic-mineral interactions under hydrothermal conditions using inert silica tubes [33].

1. Sample Preparation

- Tube Preparation: Cut a clean silica glass tube to ~30 cm length. Seal one end closed using an oxyhydrogen torch.

- Loading: Transfer the starting organic compound (solid or liquid) and weighed mineral into the tube. Add deionized, deoxygenated water (e.g., 0.3 mL).

- Deoxygenation: Connect the tube to a vacuum line. Immerse it in liquid nitrogen until contents are frozen. Open the vacuum valve to remove air from the headspace.

- Sealing: Repeat the freeze-pump-thaw cycle two more times. With the tube immersed in liquid nitrogen, use an oxyhydrogen flame to seal the other end, ensuring adequate headspace for water expansion.

2. Hydrothermal Experiment Setup

- Place the sealed silica tube into a protective steel pipe with loose screw caps.

- Place the pipe in a temperature-controlled furnace and heat to the desired temperature (e.g., 150°C). Monitor temperature with a thermocouple.

- After the set reaction time (e.g., 2 hours), quench the reaction by rapidly moving the pipe to an ice water bath.

3. Post-Reaction Analysis

- Product Recovery: Open the silica tube with a tube cutter. Transfer all products to a glass vial using a Pasteur pipette.

- Extraction: Add a dichloromethane (DCM) solution containing an internal standard (e.g., dodecane). Cap the vial, shake and vortex. Sonicate for samples with high mineral content.

- Analysis: Allow minerals to settle. Transfer the DCM layer to a GC vial. Analyze product distribution using Gas Chromatography (GC) with a suitable temperature program.

Workflow Diagram: Hydrothermal Synthesis in Silica Tubes

Parameter Optimization Data

The table below summarizes critical parameters for the controlled hydrothermal growth of VS2 nanosheets.

| Parameter | Values Tested | Optimal / Notable Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Molar Ratio (NH4VO3:TAA) | 1:2.5, 1:5, 1:7.5, 3:5 | Systematically optimized for phase purity. |

| Reaction Temperature | 100°C, 140°C, 180°C, 220°C | Significantly affects nucleation and growth rate. |

| Reaction Time | ≤1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 20 hours | Pure VS2 achieved in just 5 hours. |

| Ammonia Concentration | 2 mL, 4 mL, 6 mL | Affects solubility and reaction pathway. |

Understanding the temperature-dependent phase transformation is crucial for achieving the desired final material.

| Calcination Step | Phase Transformation | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Treatment | Amorphous Al(OH)₃ → Amorphous Al₂O₃ → γ-Al₂O₃ → α-Al₂O₃ | The sequence is critical for obtaining the stable α-phase. |

| Crystallization | Transition to γ-Al₂O₃ occurs at ~400°C. | |

| Phase Stabilization | Transition to α-Al₂O₃ occurs at ~1200°C. |

Parameter Relationships in Hydrothermal Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Hydrothermal Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Quartz or Silica Glass Tubes | Inert reaction vessel to minimize catalytic interference during organic-mineral hydrothermal studies [33]. |

| Ammonia Solution (NH₃·H₂O) | A mineralizer that increases the solubility of precursor materials, influencing reaction kinetics and product morphology [30]. |

| Thioacetamide (TAA) | A common sulfur precursor for the hydrothermal synthesis of sulfide materials like VS2 [30]. |

| Urea | Acts as a precipitating agent in the hydrothermal synthesis of spherical oxide precursors (e.g., Al₂O₃) [32]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A dispersant used to prevent agglomeration of precursor particles, promoting a uniform particle size distribution [32]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Synthesis Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Endotoxin and Microbial Contamination

- Symptoms: Unexpected immunostimulatory reactions in biological assays; inconsistent experimental results, especially in in vivo studies [35].

- Causes: Use of non-sterile reagents, working in non-aseptic conditions (e.g., chemical fume hoods instead of biological safety cabinets), using commercial reagents without verifying their sterility, or nanoparticles that readily accumulate endotoxin due to their "sticky" surface properties [35].

- Solutions:

- Work under sterile conditions using biological safety cabinets and depyrogenated glassware [35].

- Use LAL-grade or pyrogen-free water for all buffers and dispersing media [35].

- Screen commercial starting materials for endotoxin contamination [35].

- Test equipment for endotoxin by rinsing and analyzing wash samples [35].

- Employ appropriate Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assays with proper inhibition and enhancement controls to detect endotoxin [35].

Problem: Poor Control Over Nanoparticle Size and Shape

- Symptoms: High polydispersity, inconsistent optical properties (e.g., broad or asymmetric LSPR peaks for metallic nanoparticles), and poor batch-to-batch reproducibility [36] [37].

- Causes: Variable precursor concentrations, inconsistent reaction conditions (pH, temperature, incubation time), impurities in biological extracts, or improper mixing during synthesis [38] [37].

- Solutions:

- Standardize and characterize biological extracts thoroughly to account for natural variability [36] [39].

- Precisely control and document reaction parameters including pH, temperature, and media composition [38].

- Use mass measurements instead of volumetric techniques for critical reagents to improve consistency [37].

- Conduct small-scale pilot studies (20-30 mL reactions) to establish baselines before scaling up [37].

Problem: Low Yield and Scalability Issues

- Symptoms: Insufficient nanoparticle quantities for applications, inconsistent yields between batches, difficulty transitioning from laboratory to industrial scale [36] [38].

- Causes: Biological heterogeneity (in microbial cultures or plant extracts), suboptimal bioreactor conditions for microbial synthesis, inefficient purification protocols, or nutrient limitations in microbial cultures [36] [38].

- Solutions:

- Optimize microbial growth conditions and metal ion exposure times [38].

- For plant-mediated synthesis, standardize extraction protocols and consider using agricultural waste products as sustainable raw materials [40].

- Implement extracellular synthesis approaches where possible to simplify downstream processing [36].

- Develop standardized protocols for specific biological sources to improve inter-batch reproducibility [38].

Problem: Nanoparticle Aggregation and Instability

- Symptoms: Precipitation or color changes in nanoparticle solutions (e.g., from red to purple/gray for gold nanoparticles), "shouldering" in UV-Vis spectra, decreased biological activity [37].

- Causes: Inadequate capping agents, improper purification, ionic strength effects, pH changes, or aging of reagents [37].

- Solutions:

- Ensure biological extracts contain sufficient stabilizing agents (proteins, polyphenols, polysaccharides) [38] [39].

- Optimize purification methods to remove aggregates while maintaining monodisperse populations [37].

- Store nanoparticles in appropriate buffers and conditions to prevent degradation [37].

- Monitor reagent age and prepare fresh solutions for sensitive components like silver nitrate and ascorbic acid [37].

Physicochemical Characterization Troubleshooting

Problem: Interference with Characterization Techniques

- Symptoms: Inaccurate or deceptive results from standard characterization methods, particularly with dynamic light scattering (DLS) and endotoxin detection assays [35].

- Causes: Nanoparticle properties (color, turbidity) interfering with spectroscopic measurements; complex biological coronas affecting surface charge measurements [35].

- Solutions:

- Employ multiple complementary characterization techniques to cross-validate results [35] [36].

- For endotoxin detection, use multiple LAL assay formats (chromogenic, turbidity, gel-clot) to identify potential interference [35].

- Characterize nanoparticles under biologically relevant conditions (e.g., in plasma or physiological buffers) rather than just in water [35].

Table 1: Analytical Techniques for Biogenic Nanoparticle Characterization

| Technique | Parameters Measured | Common Pitfalls | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic size, size distribution | Overestimation of size due to aggregation; interference from biological matrix | Combine with electron microscopy; filter samples properly before analysis |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Surface plasmon resonance, concentration | Broad peaks indicating polydispersity; scattering effects from large particles | Use appropriate baseline corrections; monitor peak symmetry and width |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Core size, shape, morphology | Sample preparation artifacts; poor statistical representation | Analyze multiple fields; ensure proper staining and grid preparation |

| Zeta Potential | Surface charge, stability | Influence of biological corona; sensitivity to pH and ionic strength | Measure under physiological conditions; report multiple measurement conditions |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Surface functional groups, capping agents | Signal overlap from complex biological matrices | Use complementary techniques like NMR or XPS for validation |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the main advantages of green synthesis over chemical methods for nanoparticle production?

A: Green synthesis offers several key advantages: (1) It eliminates or reduces the use of hazardous chemicals, making it more environmentally friendly [41] [39]; (2) It utilizes biological reducing and stabilizing agents that are renewable, biodegradable, and often less expensive than chemical alternatives [40] [39]; (3) The resulting nanoparticles often exhibit inherent biocompatibility due to their biological coatings, making them particularly suitable for biomedical applications [38] [39]; (4) It typically operates under ambient temperature and pressure conditions, reducing energy consumption [39].

Q: How can I improve reproducibility in biogenic nanoparticle synthesis?

A: Improving reproducibility requires: (1) Standardizing biological sources by controlling growth conditions, harvest timing, and extraction methods for consistent metabolite profiles [36] [38]; (2) Documenting all reagent lots and sources, as natural variations can significantly impact results [37]; (3) Maintaining precise control over reaction parameters (pH, temperature, incubation time) and using mass measurements for critical reagents [38] [37]; (4) Implementing rigorous characterization protocols for both starting materials and final products [35] [36]; (5) Conducting regular small-scale pilot studies to monitor process consistency [37].

Q: What are the key factors that influence the size and shape of biogenically synthesized nanoparticles?

A: The main factors include: (1) Type and concentration of biological reducing agents (enzymes, phytochemicals) in the extract [38] [39]; (2) Reaction conditions such as pH, temperature, and incubation time [38]; (3) Precursor ion concentration and the ratio of precursor to reducing agents [38] [37]; (4) Incubation time - longer reactions often yield larger particles [38]; (5) Specific biomolecules present that act as capping or shape-directing agents [36] [38].

Q: How can I control the aspect ratio of anisotropic nanoparticles like gold nanorods?

A: Controlling aspect ratio requires careful manipulation of synthesis conditions: (1) For gold nanorods, silver nitrate concentration is a key parameter - increasing concentration generally increases aspect ratio up to ~850 nm LSPR [37]; (2) Using binary surfactant systems (e.g., CTAB with BDAC or sodium oleate) enables higher aspect ratios (up to 10) [37]; (3) Implementing multistage addition of growth solution to seeds can achieve extremely high aspect ratios (up to 70) [37]; (4) The amount of seed particles used inversely affects aspect ratio - more seeds typically yield shorter nanorods [37].

Q: What are the main challenges in scaling up biogenic nanoparticle production?

A: Scale-up challenges include: (1) Batch-to-batch variability due to biological heterogeneity [36] [38]; (2) Difficulty in maintaining precise control over reaction parameters in large volumes [36]; (3) Downstream purification complexities, particularly for intracellularly synthesized nanoparticles [36] [38]; (4) Cost-effective sourcing of biological materials in large quantities [40] [42]; (5) Ensuring consistent nanoparticle properties (size, shape, surface chemistry) across production scales [36] [38].

Table 2: Optimization of Reaction Conditions for Biogenic Synthesis

| Parameter | Effect on Nanoparticle Properties | Optimal Range/Approach |

|---|---|---|