Overcoming the Biggest Challenges in Predictive Inorganic Materials Synthesis

The acceleration of inorganic materials discovery is critically dependent on solving the predictive synthesis bottleneck.

Overcoming the Biggest Challenges in Predictive Inorganic Materials Synthesis

Abstract

The acceleration of inorganic materials discovery is critically dependent on solving the predictive synthesis bottleneck. This article explores the fundamental and methodological challenges, from the lack of a unifying synthesis theory and the limitations of thermodynamic proxies to the rise of data-driven and AI-powered approaches. It provides a critical examination of current machine learning models for retrosynthesis and synthesizability prediction, discusses troubleshooting for common experimental and data pitfalls, and offers a comparative analysis of validation frameworks. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes key insights to guide the development of more reliable, generalizable, and experimentally viable predictive synthesis pipelines.

Why Inorganic Synthesis is a Fundamental Scientific Challenge

The acceleration of materials discovery is a cornerstone of modern technological competitiveness, driving innovations across industries from energy storage to pharmaceuticals [1]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning have supercharged the initial phase of this process, enabling researchers to rapidly screen thousands of candidate compounds in silico and predict novel materials with tailored properties [2]. Generative models like Microsoft's MatterGen can creatively propose new structures fine-tuned to user specifications, often with predicted thermodynamic stability [3]. However, a critical bottleneck emerges at the next stage: translating these computational predictions into physically realized materials. The hardest step in materials discovery is unequivocally making the material [3]. This whitepaper examines the core challenges in predictive inorganic materials synthesis, framing them within the broader thesis that synthesizability—not property prediction—represents the fundamental limitation in accelerating materials innovation.

The central problem can be summarized as: thermodynamically stable ≠ synthesizable [3]. While AI can successfully predict thousands of potentially stable compounds, most will never be successfully synthesized in the lab due to complex kinetic barriers, competing phase formations, and path-dependent reaction dynamics. Synthesis is fundamentally a pathway problem, analogous to crossing a mountain range where one cannot simply go straight over the top but must identify viable passes that navigate the complex energetic terrain [3]. This challenge is particularly acute for inorganic materials, where synthesis parameters exist in a sparse, high-dimensional space that is difficult to optimize directly [4].

The Data Deficit: Fundamental Limitations in Synthesis Prediction

The Data Scarcity and Sparsity Challenge

Computational materials synthesis screening faces two primary data challenges: data sparsity and data scarcity [4]. Synthesis routes are typically represented as high-dimensional vectors containing parameters such as solvent concentrations, heating temperatures, processing times, and precursors. These representations are inherently sparse because while countless synthesis actions are possible, only a limited subset is actually employed for any given material [4]. simultaneously, the available data is scarce, with specific material systems like SrTiO3 having fewer than 200 text-mined synthesis descriptors in literature—insufficient for robust machine-learning model training [4].

The problem extends beyond volume to data quality and bias. Scientific literature predominantly reports successful syntheses, while failed attempts—the crucial "negative results"—rarely see publication [3]. This creates a fundamental skew in available data. Furthermore, anthropogenic biases are prevalent: once a convenient synthesis route is established, it becomes conventional. For barium titanate (BaTiO₃), 144 of 164 published recipes use the same precursors (BaCO₃ + TiO₂), despite this route requiring high temperatures and long heating times and proceeding through intermediates [3]. This convention-driven approach limits the exploration of potentially superior synthesis pathways.

The Intractable Comprehensive Dataset Problem

Building a comprehensive synthesis database faces fundamental scalability challenges. While computational materials databases for structures and properties contain hundreds of thousands of entries [1], creating an equivalent for synthesis would require experimentally testing millions of reaction combinations under every possible condition [3]. Testing just binary reactions between 1,000 compounds would require approximately 500,000 experiments—a scale beyond the capabilities of most high-throughput laboratories, even those operating autonomously [3]. This intractability makes purely data-driven approaches to synthesis prediction fundamentally limited with current methodologies.

Table 1: Comparative Data Availability for Materials Research

| Data Type | Example Sources | Volume | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Structures & Properties | Materials Project, AFLOWLIB, OQMD [1] | ~200,000 entries [3] | Limited synthesis information |

| Organic Chemistry Reactions | Multiple commercial and academic databases | Millions of reactions | Limited transferability to inorganic systems |

| Inorganic Synthesis Recipes | Text-mined literature data [4] | Sparse (e.g., <200 for SrTiO3) [4] | Publication bias, sparse parameters, failed attempts rarely reported |

Computational Frameworks for Synthesis Prediction

Dimensionality Reduction and Data Augmentation

To address the data sparsity challenge, researchers have developed innovative computational frameworks. Variational autoencoders (VAEs) can compress sparse, high-dimensional synthesis representations into lower-dimensional latent spaces, improving machine learning performance by emphasizing the most relevant parameter combinations [4]. In one study, a VAE framework was applied to suggest quantitative synthesis parameters for SrTiO3 and identify driving factors for brookite TiO2 formation and MnO2 polymorph selection [4].

To overcome data scarcity, a novel data augmentation approach incorporates literature synthesis data from related materials systems using ion-substitution material similarity functions [4]. This method creates an augmented dataset with an order of magnitude more data (1,200+ text-mined synthesis descriptors) by building a neighborhood of similar materials syntheses centered on the material of interest, with greater weighting placed on the most closely related syntheses [4]. When tested on the task of differentiating between SrTiO3 and BaTiO3 syntheses, this approach demonstrated the value of compressed representations, though linear dimensionality reduction methods like PCA performed worse than the original canonical features [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Synthesis Representations for SrTiO3/BaTiO3 Classification

| Representation Method | Dimensionality | Prediction Accuracy | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical Features | High (original feature space) | 74% | Intuitive encoding but sparse representation |

| PCA (2D) | 2 | 63% | Captures ~33% variance, significant information loss |

| PCA (10D) | 10 | 68% | Captures ~75% variance, moderate information loss |

| VAE with Data Augmentation | Low (compressed latent space) | Comparable to canonical | Reduced reconstruction error, improved generalizability |

Network Science Approaches

Network science provides promising frameworks for representing and analyzing synthesis pathways. Materials networks represent inorganic compounds as nodes connected by edges representing thermodynamic relationships or reaction pathways [1]. This approach offers several advantages: it naturally represents high-dimensional chemical reaction spaces without coordinate systems or dimensionality reduction, provides intuitive conceptual frameworks with meaningful descriptors (hubs, communities, betweenness), and leverages efficient algorithms from network science [1].

In one implementation, a unidirectional materials network encoded thermodynamic stability from the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), comprising ~21,300 nodes (inorganic compounds) with each node connecting to ~3,850 edges representing two-phase equilibria [1]. The dense connectivity of this network highlights the complex reactivity landscape that must be navigated for successful synthesis. Topological analysis of such networks can identify common intermediates, central compounds that appear in many reactions, and potential synthesis pathways through network traversal algorithms [1].

Diagram 1: Materials network for synthesis prediction. This network representation shows potential synthesis pathways from precursors to target material, highlighting competing phases and central intermediates that appear in multiple reaction pathways.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

VAE Framework for Synthesis Parameter Screening

The following methodology outlines the experimental protocol for virtual screening of inorganic materials synthesis parameters using deep learning, as demonstrated in recent research [4]:

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Text-Mining Synthesis Recipes: Extract synthesis parameters from scientific literature, including quantitative parameters (heating temperatures, processing times, solvent concentrations) and qualitative descriptors (precursors used, atmosphere conditions).

- Construct Canonical Feature Vectors: Create high-dimensional vectors representing each synthesis route, maintaining consistent parameter ordering and handling missing values through appropriate imputation or masking techniques.

- Build Similarity Networks: Implement context-based word similarity algorithms and ion-substitution compositional similarity algorithms to identify related materials systems for data augmentation.

Model Architecture and Training:

- VAE Implementation: Design a variational autoencoder with an encoder network that maps sparse synthesis representations to a lower-dimensional latent space, and a decoder network that reconstructs synthesis parameters from latent points.

- Gaussian Prior Application: Apply a Gaussian function as the latent prior distribution to improve model generalizability by reducing overfitting to limited training data.

- Weighted Training with Augmented Data: Incorporate the augmented dataset (containing synthesis data from related materials) with greater weighting placed on the most closely related syntheses to the target material system.

Validation and Screening:

- Latent Space Interpolation: Sample new synthesis parameter sets by interpolating between successful synthesis routes in the compressed latent space.

- Synthesis Target Prediction: Evaluate the learned representations by using them as input to classifiers for tasks such as differentiating between syntheses of closely related materials (e.g., SrTiO3 vs. BaTiO3).

- Driving Factor Identification: Analyze the latent space dimensions to identify potential driving factors for specific synthesis outcomes by examining parameter variations along meaningful latent directions.

Domain Adaptation for Realistic Property Prediction

When predicting properties for targeted material families, standard random train-test splits can lead to over-optimistic performance estimates. Domain adaptation (DA) methodologies provide more realistic evaluation protocols [5]:

Experimental Setup:

- Scenario Definition: Identify realistic application scenarios where models must predict properties for out-of-distribution (OOD) materials that differ systematically from training data.

- Domain Alignment: Implement domain adaptation techniques to align feature distributions between source (training) and target (test) domains, minimizing domain shift.

- Model Selection: Evaluate both standard machine learning models and DA-enhanced variants on realistic OOD test sets representing common materials discovery scenarios.

Evaluation Metrics:

- OOD Performance Assessment: Measure prediction accuracy specifically on target material families not represented in training data.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare performance against standard machine learning models without domain adaptation components.

- Generalization Gap Analysis: Quantify the performance difference between random splits and realistic OOD splits to assess model robustness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Inorganic Synthesis Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Carbonates (e.g., BaCO3) | Common precursor for oxide materials; provides metal cation and carbonate anion for decomposition | Primary precursor in conventional BaTiO3 synthesis [3] |

| Metal Oxides (e.g., TiO2) | Source of metal cations; widely available with varying purity levels | Reactant with BaCO3 for BaTiO3 formation through solid-state reaction [3] |

| Metal Hydroxides (e.g., Ba(OH)₂) | Alternative precursor with different decomposition kinetics | Less common but potentially more reactive alternative to carbonates [3] |

| Solvents (various aqueous and non-aqueous) | Reaction medium for solution-based synthesis; affects solubility and reaction rates | Controlling solvent concentrations in hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis [4] |

| Mineralizers (e.g., hydroxides, halides) | Enhance solubility and reactivity in hydrothermal synthesis | Used in alternative BaTiO3 routes to lower synthesis temperature [3] |

Synthesis Workflow and Pathway Analysis

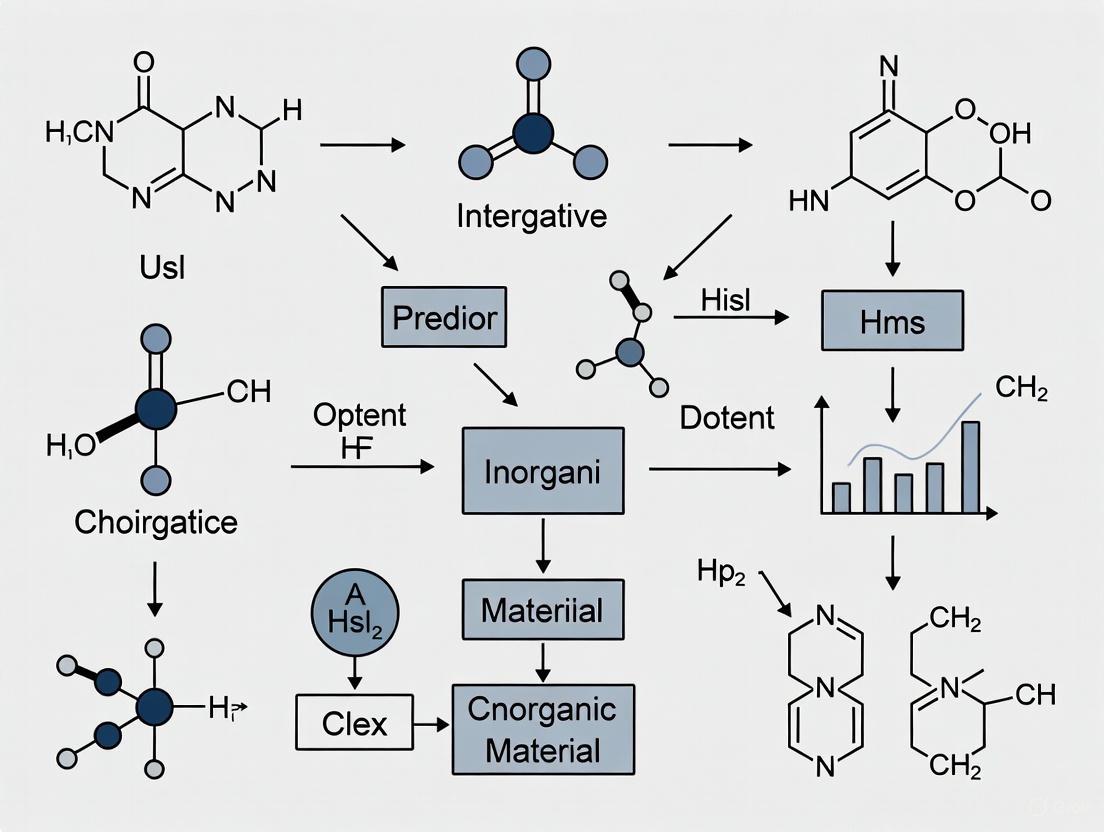

The complete pathway from virtual discovery to synthesized materials involves multiple critical decision points where bottlenecks can occur. The following diagram illustrates this workflow and the key challenges at each stage:

Diagram 2: Synthesis workflow and critical bottlenecks. This workflow illustrates the pathway from virtual discovery to synthesized materials, highlighting the key bottlenecks where promising computational predictions often fail to translate to real-world synthesis.

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

Integrated Computational-Experimental Approaches

Promising approaches are emerging that combine computational prediction with experimental validation in iterative cycles. Autonomous laboratories capable of real-time feedback and adaptive experimentation represent a frontier in overcoming the synthesis bottleneck [2]. These systems combine AI-driven synthesis planning with robotic experimentation, enabling closed-loop optimization of reaction conditions with minimal human intervention.

Reaction network-based platforms take a systematic approach to exploring synthesis pathways. Some systems generate hundreds of thousands of potential reaction pathways for inorganic compounds of interest, starting from various precursors including uncommon intermediate phases rarely tested in conventional approaches [3]. These alternatives can reveal low-barrier synthesis routes that circumvent traditional kinetic obstacles. Such systems model routes with thermodynamic principles, simulate phase evolution in virtual reactors, and use machine-learned predictors to filter promising candidates [3].

Explainable AI and Hybrid Modeling

As AI systems become more involved in synthesis planning, explainable AI approaches are gaining importance for improving model trust and scientific insight [2]. By making the reasoning behind synthesis recommendations more transparent, these systems become more usable and trustworthy for experimental chemists. Simultaneously, hybrid approaches that combine physical knowledge with data-driven models are emerging as powerful frameworks [2]. These models incorporate fundamental chemical principles and thermodynamic constraints, reducing reliance on purely data-driven patterns that may not generalize beyond training distributions.

Table 4: Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Screening Approaches

| Screening Approach | Key Advantages | Limitations | Reported Hit Rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimental Screening | Direct experimental validation; broad exploration | High cost; resource intensive; limited to available libraries | 0.021% (85 hits from 400,000 compounds) [6] |

| Virtual Screening (Docking) | Lower cost; accesses larger chemical space; readily available compounds | False positives/negatives; limited synthesis accessibility | 34.8% (127 hits from 365 compounds tested) [6] |

| VAE-Based Synthesis Screening | Compresses sparse parameter spaces; suggests novel conditions | Limited by training data volume; requires data augmentation | Comparable to human intuition (78% accuracy for related tasks) [4] |

The transition from virtual discovery to real-world synthesis represents the critical bottleneck in modern materials research. While AI has dramatically accelerated the identification of promising candidate materials, the synthesis step remains challenging, path-dependent, and difficult to predict. Successfully navigating this bottleneck requires addressing fundamental challenges in data scarcity, pathway complexity, and kinetic competition. Solutions are emerging through integrated approaches that combine data-driven modeling with network science, domain adaptation, and physical principles. The most promising directions involve creating more comprehensive synthesis datasets (including negative results), developing hybrid models that incorporate chemical knowledge, and building autonomous systems that can efficiently explore synthesis parameter spaces. By focusing on the synthesizability challenge with the same intensity previously directed at property prediction, the materials research community can transform the current bottleneck into a breakthrough area, ultimately enabling the rapid realization of computationally discovered materials with transformative applications across technology and medicine.

Contrasting Organic and Inorganic Retrosynthesis Paradigms

Retrosynthesis, the process of deconstructing a target molecule into simpler starting materials, is a cornerstone of synthetic chemistry. However, the fundamental strategies and challenges differ dramatically between organic and inorganic chemistry, influencing the development of predictive computational tools. In organic chemistry, retrosynthesis is a well-established, multi-step logic tree that breaks down complex molecular structures through known reaction mechanisms [7]. In contrast, inorganic solid-state chemistry primarily involves one-step reactions where a set of precursors react to form a target compound, a process with no general unifying theory that continues to rely heavily on trial-and-error experimentation [8] [9]. This article contrasts these two paradigms, framing the discussion within the significant challenges facing predictive synthesis research in inorganic materials, and explores how emerging machine learning (ML) approaches are attempting to bridge this knowledge gap.

Fundamental Paradigm Divergence

The core distinction lies in the nature of the chemical systems and their synthetic logic. Organic retrosynthesis deals with discrete, molecular structures that can be systematically broken down through a sequence of well-defined mechanistic steps involving covalent bond formation and cleavage [7] [10]. The process often employs a "logic tree" approach, where a target molecule is recursively deconstructed into increasingly simpler precursors.

Inorganic solid-state retrosynthesis, however, targets extended periodic structures—often crystalline materials—where the goal is to identify a set of solid precursors that, upon heating or other treatment, will react in a single step to form the desired product [8]. This one-step process lacks the multi-step logical framework of organic chemistry and is profoundly underdetermined, as many precursor combinations can potentially form the same target material under different conditions [8]. The following diagram illustrates the contrasting logical workflows of these two paradigms.

Figure 1: Contrasting logical workflows of organic and inorganic retrosynthesis paradigms.

Quantitative Comparison of Retrosynthesis Approaches

The fundamental differences between the paradigms have led to the development of specialized computational tools. The table below summarizes the performance and characteristics of state-of-the-art models in both domains, highlighting their distinct objectives and evaluation metrics.

Table 1: Performance and Characteristics of State-of-the-Art Retrosynthesis Models

| Model Name | Domain | Core Approach | Key Performance Metric | Top-1 Accuracy | Generalization Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retro-Rank-In [8] | Inorganic | Ranking precursor sets in a shared latent space | Precursor set recommendation | Not Specified (SOTA in ranking) | High - Aims to predict unseen precursors (e.g., CrB + Al for Cr₂AlB₂) |

| RSGPT [11] | Organic | Generative Transformer pre-trained on 10B+ synthetic data points | Exact match accuracy (USPTO-50k) | 63.4% | Medium - Template-free, but limited by training data scope |

| RetroCaptioner [12] | Organic | Contrastive Reaction Center Captioner with dual-view attention | Exact match accuracy (USPTO-50k) | 67.2% | Medium - Focuses on reaction center variability |

| Retrieval-Retro [8] | Inorganic | Multi-label classification with reference material retrieval | Precursor recommendation | Not Specified | Low - Cannot recommend precursors outside its training set |

A critical challenge in inorganic retrosynthesis is the inability of many models to generalize and recommend precursors not present in their training data, a significant bottleneck for discovering new compounds [8]. In contrast, organic retrosynthesis models, while highly accurate on known reaction types, face challenges in generalizing to entirely novel reaction mechanisms or structural motifs outside their training distribution.

Experimental Protocols in Retrosynthesis Research

Protocol for Inorganic Retrosynthesis (Retro-Rank-In Framework)

The Retro-Rank-In framework exemplifies the modern data-driven approach to the inorganic synthesis problem [8].

Problem Formulation: The retrosynthesis task is reformulated from a multi-label classification problem into a pairwise ranking task. The objective is to learn a ranker ( \theta_{\text{Ranker}} ) that scores the chemical compatibility between a target material ( T ) and a candidate precursor ( P ), rather than classifying from a fixed set of known precursors.

Model Architecture:

- Compositional Representation: The target material and precursors are represented by their elemental composition vectors.

- Materials Encoder: A composition-level transformer-based encoder generates chemically meaningful representations for both targets and precursors, embedding them into a unified latent space.

- Pairwise Ranker: This core component is trained to evaluate and score the likelihood that a target and a precursor can co-occur in a viable synthetic route.

Training and Inference:

- Training: The model is trained on a bipartite graph of inorganic compounds, learning the pairwise ranking function. This approach allows for custom negative sampling strategies to handle dataset imbalance.

- Inference: For a new target material, candidate precursors are scored by the ranker, and the top-ranked sets are proposed as the most likely synthesis candidates. This enables the recommendation of precursors not seen during training.

Protocol for Organic Retrosynthesis (RetroCaptioner Framework)

RetroCaptioner represents an advanced, end-to-end template-free approach for organic retrosynthesis [12].

Data Preprocessing:

- Dataset: The model is trained and evaluated on the benchmark USPTO-50k dataset, which contains 50,000 reaction examples classified into 10 reaction types.

- SMILES Representation: Molecules (products and reactants) are represented as SMILES strings. SMILES sequences for reactions are created by concatenating reactant SMILES with a "." separator.

- Atom-Mapping: SMILES alignment with atom-mapping is used during training to establish correspondence between atoms in products and reactants.

Model Architecture:

- Uni-view Sequence Encoder: A standard Transformer encoder processes the SMILES string of the product molecule.

- Dual-view Sequence-Graph Encoder: This module integrates both the sequential SMILES information and the structural information from the molecular graph.

- Contrastive Reaction Center (RC) Captioner (RCaptioner): A novel component that guides the attention mechanism using contrastive learning. It allocates flexible weights to highlight the variable reaction centers in different molecules, providing a chemically plausible constraint.

- Transformer Decoder: Generates the SMILES string of the predicted reactants autoregressively.

Training and Evaluation:

- The model is trained end-to-end to translate product SMILES to reactant SMILES.

- Performance is evaluated using top-k exact match accuracy, measuring the percentage of test reactions for which the model's predicted reactant SMILES exactly match the ground truth. RetroCaptioner achieves a top-1 accuracy of 67.2% and a top-10 accuracy of 99.4% on the USPTO-50k dataset [12].

Visualization of Model Architectures

The following diagram illustrates the architectural differences between a state-of-the-art inorganic model (Retro-Rank-In) and a sophisticated organic model (RetroCaptioner), highlighting their distinct approaches to processing chemical information.

Figure 2: Architectural comparison of Retro-Rank-In (inorganic) and RetroCaptioner (organic) models.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Retrosynthesis Research

| Resource / Tool Name | Type / Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| USPTO Datasets [12] [11] | Reaction Database | Benchmark datasets (e.g., USPTO-50k, USPTO-FULL) containing known organic reactions for training and evaluating retrosynthesis models. |

| Materials Project DFT Database [8] | Computational Database | Provides calculated formation enthalpies and other properties for ~80,000 inorganic compounds, used to incorporate domain knowledge into models. |

| SMILES Representation [12] [11] | Molecular Descriptor | A line notation for representing organic molecular structures as text, enabling the use of sequence-based models like Transformers. |

| RDChiral [11] | Algorithm | A reverse synthesis template extraction algorithm used to generate large-scale synthetic reaction data for pre-training models like RSGPT. |

| Transformer Architecture [8] [12] [11] | Machine Learning Model | A neural network architecture based on self-attention mechanisms, foundational for state-of-the-art sequence-to-sequence models in both organic and inorganic retrosynthesis. |

| Pairwise Ranker [8] | ML Component | The core learning component in Retro-Rank-In that scores precursor-target compatibility, enabling recommendation of novel precursors not in the training data. |

| Contrastive Reaction Center Captioner [12] | ML Component | A module in RetroCaptioner that uses contrastive learning to guide the model's attention to chemically plausible reaction centers in the product molecule. |

The divergence between organic and inorganic retrosynthesis paradigms is deep-rooted, stemming from the fundamental differences between molecular and extended solid-state chemistry. Organic retrosynthesis benefits from a well-defined logical framework and mechanistic rules, allowing data-driven models to achieve high predictive accuracy within known chemical spaces. In contrast, inorganic retrosynthesis grapples with a one-step, underdetermined problem, where the primary challenge is not sequential logic but the initial prediction of chemically compatible precursor sets from a vast and open possibility space. The development of ML approaches like Retro-Rank-In, which reformulate the problem as a ranking task in a shared latent space, represents a promising direction for overcoming the critical bottleneck of predicting novel precursors. Ultimately, progress in predictive inorganic materials synthesis depends on creating models that do not merely recombine known chemistry but can genuinely generalize and explore uncharted regions of the inorganic chemical space.

The Search for a Unifying Principle Beyond Trial-and-Error

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials have long been the foundation of technological progress, enabling breakthroughs from clean energy to information processing [13]. Traditional approaches, however, remain fundamentally constrained by expensive, time-consuming trial-and-error methodologies that cannot efficiently navigate the vastness of chemical space [13] [14]. While computational materials science has emerged as a transformative field, a significant disconnect persists between theoretical prediction and experimental realization [15] [16]. The core challenge lies in moving beyond these fragmented, intuition-dependent methods toward a unified, principled framework for predictive synthesis.

This whitepaper examines the critical bottlenecks hindering autonomous materials discovery and synthesizes emerging paradigms that point toward a more unified approach. We analyze the persistent issues of structural disorder misclassification, inadequate synthesis feasibility prediction, and the interpretation gaps in characterization data that have led to high-profile overstatements of AI capabilities [15] [16]. Conversely, we explore integrative solutions combining large-scale active learning, physics-informed generative models, and human-AI collaboration frameworks that are progressively replacing trial-and-error with principled discovery.

Critical Bottlenecks in Predictive Synthesis

The Disorder Challenge in Crystallographic Prediction

A fundamental limitation in current high-throughput prediction tools is their pervasive failure to adequately model compounds where multiple elements occupy the same crystallographic site. This routinely leads to the misclassification of known disordered phases as novel ordered compounds [15] [16].

Table 1: Documented Cases of Disorder Misclassification in AI-Predicted Materials

| AI Tool | Claimed Novel Compound | Actual Compound | Nature of Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatterGen | TaCr₂O₆ | Ta₁/₂Cr₁/₂O₂ (known since 1972) | Ordered structure predicted for known disordered phase; compound was in training data [15] |

| Autonomous Discovery Study [16] | Multiple "novel" ordered compounds | Known compositionally disordered solid solutions | Two-thirds of claimed successful materials were likely disordered versions of predicted ordered compounds [16] |

This systematic blind spot arises from the computational difficulty of modeling disorder economically and the inherent limitations of training datasets that may not adequately represent disordered configurations [16]. The consequence is a significant overstatement of discovery claims, underscoring that automated analysis cannot yet replace rigorous human crystallographic expertise [15] [16].

The Synthesis Feasibility Gap

The second critical bottleneck lies in accurately predicting whether computationally stable materials can be experimentally synthesized. Current approaches suffer from several deficiencies:

- Overreliance on Thermodynamics: Standard density functional theory (DFT) calculations assess stability via formation energy relative to competing phases but neglect kinetic stabilization and barriers essential for synthesis feasibility [14].

- Inadequate Empirical Rules: Heuristics like the charge-balancing criterion fail dramatically; for Cs binary compounds, only 37% of experimentally observed materials meet this criterion under common oxidation states [14].

- Black-Box Synthesis Condition Prediction: Unlike organic synthesis with predictable functional group transformations, inorganic solid-state synthesis lacks universal principles, with mechanisms that "remain unclear" and are governed by multivariate parameters (temperature, time, precursors, etc.) [14].

This feasibility gap means that numerous theoretically predicted materials with promising properties prove difficult or impossible to synthesize in practice, creating a fundamental disconnect between prediction and realization [14].

Emerging Unifying Frameworks and Methodologies

Integrated AI Agent Frameworks for Inverse Design

A transformative approach emerges in integrated AI agent frameworks like Aethorix v1.0, which implement a closed-loop, physics-informed inverse design paradigm [17]. This represents a significant advancement over traditional high-throughput screening, which merely accelerates evaluation rather than intelligently guiding exploration.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of AI-Driven Materials Discovery Platforms

| Platform | Core Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNoME [13] | Graph neural networks with active learning | Unprecedented generalization; discovered 2.2M stable structures; power-law scaling with data | Primarily thermodynamic stability; limited synthesis guidance |

| Aethorix v1.0 [17] | Integrated AI agent with inverse design | Multi-scale dataset integration; industrial process optimization; zero-shot design | Framework complexity; requires substantial computational resources |

| LLM-Based Extraction [18] | Scientific literature mining using Claude 3 Opus, Gemini 1.5 Pro | High accuracy in extracting synthesis conditions; proactive response structuring | Limited to documented procedures; cannot validate physical feasibility |

The Aethorix architecture demonstrates how unifying principles can be implemented practically through three interconnected pillars:

- Scientific Corpus Reasoning Engine: Leverages large language models (LLMs) for exhaustive multimodal analysis, identifying research gaps and formalizing industrial challenges into structured design constraints [17].

- Diffusion-Based Generative Model: Enables zero-shot inverse design of material formulations by factoring in natural complexities like structural disorder, surface functionalization, and temperature-dependent effects [17].

- Specialized Interatomic Potentials: Accelerates property prediction with first-principles accuracy but at speeds compatible with industrial production timelines [17].

Scaling Deep Learning with Active Learning Cycles

The GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) framework demonstrates how scaling laws can be harnessed through systematic active learning to achieve unprecedented generalization in stability prediction [13]. This approach has expanded the number of known stable crystals by almost an order of magnitude.

The GNoME methodology implements a self-improving discovery cycle:

- Diverse Candidate Generation: Uses symmetry-aware partial substitutions (SAPS) and random structure search to generate candidate structures.

- Neural Network Filtration: Employs graph neural networks to filter candidates based on predicted stability.

- DFT Verification: Computes energies of filtered candidates using density functional theory.

- Iterative Retraining: Incorporates verified results into subsequent training cycles, creating a data flywheel effect.

Through this process, GNoME models achieved a reduction in prediction error from 21 meV atom⁻¹ to 11 meV atom⁻¹, with precision for stable predictions improving to above 80% for structures and 33% for composition-only trials [13]. This demonstrates the power-law scaling relationships characteristic of other domains of deep learning now applied to materials science.

Advanced Synthesis Route Extraction with Large Language Models

Beyond structure prediction, LLMs are demonstrating remarkable capabilities in extracting synthesis knowledge from scientific literature. A recent systematic evaluation found that Claude 3 Opus excelled in providing complete synthesis data, while Gemini 1.5 Pro outperformed others in accuracy, characterization-free compliance, and proactive structuring of responses [18].

These capabilities enable the efficient construction of structured datasets that can help train models, predict outcomes, and assist in the synthesis of new materials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [18]. When integrated with the frameworks above, this represents a crucial bridge between predicted materials and their experimental realization.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

High-Throughput Computational Screening Protocol

For large-scale materials discovery, the following protocol adapted from GNoME provides a robust framework:

Candidate Generation:

- Apply symmetry-aware partial substitutions (SAPS) to known crystals, enabling incomplete replacements to maximize diversity [13].

- Generate composition-only candidates through oxidation-state balancing with relaxed constraints to include non-trivial compositions like Li₁₅Si₄ [13].

- Initialize 100 random structures for promising compositions using ab initio random structure searching (AIRSS) [13].

Neural Network Filtration:

- Implement graph neural networks with message-passing formulations and swish nonlinearities [13].

- Normalize messages from edges to nodes by the average adjacency of atoms across the dataset.

- Use volume-based test-time augmentation and uncertainty quantification through deep ensembles [13].

- Cluster structures and rank polymorphs for DFT evaluation.

DFT Validation:

- Perform DFT computations using standardized settings (e.g., Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) [13].

- Calculate formation energies and phase separation energies relative to competing phases.

- Verify stability with respect to the updated convex hull of known compounds.

Experimental Synthesis and Characterization Protocol

For experimental validation of predicted materials, rigorous methodology is essential to avoid misclassification:

Synthesis Planning:

Disorder-Aware Characterization:

- Employ powder X-ray diffraction with Rietveld refinement, recognizing that fully automated analysis remains unreliable [16].

- Explicitly test for site disorder by evaluating if elements can share crystallographic sites, resulting in higher-symmetry space groups [16].

- Compare patterns with known disordered phases in databases to prevent misidentification of known compounds as novel [15].

Stability Assessment:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental and computational tools driving modern materials discovery span multiple domains, from traditional synthesis to artificial intelligence.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Predictive Synthesis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [13] | Density functional theory calculations | Energy computation for structure validation and training data generation |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [13] | Structure-energy relationship prediction | Stability prediction and candidate filtration in active learning cycles |

| Symmetry-Aware Partial Substitutions (SAPS) [13] | Crystal structure generation | Creating diverse candidate structures beyond simple ionic substitutions |

| Ab initio Random Structure Searching (AIRSS) [13] | Structure prediction from composition | Initializing plausible crystal structures for composition-only candidates |

| In situ Powder X-ray Diffraction [14] | Real-time monitoring of synthesis reactions | Detecting intermediates and products during solid-state reactions |

| Large Language Models (Claude 3 Opus, Gemini 1.5 Pro) [18] | Scientific literature extraction | Mining synthesis conditions and constructing structured Q&A datasets |

| Diffusion-Based Generative Models [17] | Inverse materials design | Proposing novel structures tailored to specific target properties |

The search for a unifying principle beyond trial-and-error is progressively converging on an integrated paradigm that combines large-scale active learning, physics-informed generative models, and human expertise integration. This framework acknowledges that no single algorithmic breakthrough can overcome the fundamental complexities of inorganic synthesis alone but demonstrates how coordinated systems can systematically address current limitations.

The most promising path forward involves recognizing that human intelligence and artificial intelligence have complementary strengths in materials discovery. As the MatterGen case illustrates [15], rigorous human verification remains essential to prevent misclassification of disordered phases. Conversely, systems like GNoME reveal how AI can dramatically expand the scope of human chemical intuition by discovering stability relationships across combinatorially vast spaces [13].

Future progress hinges on better modeling of disorder [16], improved integration of synthesis feasibility considerations [14], and the development of more reliable automated characterization tools [16]. As these capabilities mature, the emerging unifying principle appears to be one of recursive integration - where prediction, synthesis, and characterization form a closed-loop system that continuously refines its understanding of the materials landscape, progressively replacing trial-and-error with principled design across the vast frontier of inorganic chemical space.

Limitations of Traditional Thermodynamic and Charge-Balancing Proxies

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are fundamental to technological advancement. A critical step in this process is the reliable identification of synthesizable materials—those that are synthetically accessible through current capabilities, regardless of whether they have been synthesized yet [19]. For decades, researchers have relied on traditional proxy metrics to predict synthesizability, primarily charge-balancing criteria and thermodynamic stability calculations. These proxies have been embedded in materials research workflows due to their conceptual simplicity and computational accessibility. However, within the broader context of predictive inorganic materials synthesis research, these traditional methods exhibit significant limitations that can misdirect discovery efforts. The growing disconnect between computational predictions and experimental synthesis outcomes has revealed an urgent need to critically examine these foundational approaches and transition toward more sophisticated, data-driven synthesizability models that better capture the complex physical and practical factors governing successful synthesis.

Critical Analysis of Charge-Balancing Proxies

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Basis

The charge-balancing approach serves as a chemically intuitive filter for predicting synthesizability. This method assesses whether a chemical formula can achieve net neutral ionic charge using common oxidation states of its constituent elements [19]. The underlying principle assumes that stable inorganic compounds typically form structures where positive and negative charges balance exactly, reflecting ionic bonding characteristics. This computationally inexpensive heuristic has been widely implemented in preliminary materials screening workflows to quickly eliminate compositions that appear electrostatically implausible.

Quantitative Performance Deficiencies

Despite its theoretical appeal, empirical evidence demonstrates that charge-balancing constitutes an excessively stringent and inaccurate filter for synthesizability prediction. Comprehensive analysis of known materials reveals that only approximately 37% of synthesized inorganic compounds in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) satisfy charge-balancing criteria according to common oxidation states [19]. The performance is particularly poor for specific material classes; for example, merely 23% of known binary cesium compounds are charge-balanced despite their typically ionic bonding character [19]. This significant discrepancy between theoretical prediction and experimental reality underscores the method's fundamental limitations.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Charge-Balancing Proxy

| Material Category | Charge-Balanced Percentage | Data Source | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| All synthesized inorganic materials | 37% | ICSD | Majority of real materials violate simple charge-balancing |

| Binary cesium compounds | 23% | ICSD | Fails even for highly ionic systems |

| Ionic binary compounds | Variable, often <50% | Supplementary analysis [19] | Overly restrictive for practical screening |

Root Causes of Failure

The poor performance of charge-balancing stems from its inability to account for diverse bonding environments present across different material classes. The approach fails to accommodate:

- Metallic bonding systems where electron delocalization renders formal oxidation states less meaningful

- Covalent materials where charge transfer between elements is partial or directional

- Compensating structural features such as vacancies, interstitials, or non-stoichiometry that stabilize otherwise charge-imbalanced compositions

- Multivalent elements with oxidation states that context-dependent on local coordination environment

The inflexibility of the charge neutrality constraint prevents it from capturing the complex chemical bonding diversity that characterizes real inorganic materials [19]. Consequently, using charge-balancing as a primary synthesizability filter inevitably excludes numerous potentially synthesizable compounds from consideration.

Limitations of Thermodynamic Stability Proxies

Methodological Framework

Thermodynamic stability assessment typically employs density functional theory (DFT) to calculate a material's formation energy relative to competing phases in the same chemical space. The most prevalent approach involves determining a material's distance from the convex hull of stability, with negative formation energies or minimal hull distances interpreted as indicators of synthesizability [20]. This method implicitly assumes that synthesizable materials will lack thermodynamically favored decomposition pathways.

Fundamental Conceptual Flaws

Thermodynamic stability metrics suffer from several conceptual limitations when used as synthesizability proxies:

- Kinetic因素忽略: Traditional formation energy calculations fail to account for kinetic stabilization effects that enable metastable materials to persist under ambient conditions [20]

- Zero-temperature limitation: Standard DFT calculations typically consider only electronic energy at 0 K, neglecting finite-temperature effects including entropic contributions that influence synthesis outcomes [21]

- Ground-state bias: The convex hull approach preferentially identifies ground-state structures while overlooking metastable phases that may be experimentally accessible [22]

- Synthesis condition independence: Thermodynamic proxies do not incorporate synthesis-specific parameters such as pressure, temperature, or precursor selection that determine experimental feasibility

Empirical Performance Shortcomings

Experimental validation reveals significant gaps in the predictive capability of thermodynamic stability metrics. Formation energy calculations successfully capture only approximately 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials [19]. Furthermore, numerous hypothetical materials predicted to be thermodynamically stable remain unsynthesized despite extensive experimental effort in well-explored chemical spaces [20]. This suggests the existence of significant kinetic barriers or other non-thermodynamic factors that prevent their synthesis.

Table 2: Limitations of Thermodynamic Stability Proxies

| Limitation Category | Specific Deficiency | Impact on Synthesizability Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic considerations | Ignores activation energy barriers | Overestimates synthesizability of materials with high kinetic barriers |

| Metastable materials | Cannot identify synthesizable metastable phases | Underestimates synthesizability of metastable compounds |

| Synthesis conditions | Does not account for process parameters | Fails to predict condition-dependent synthesizability |

| Temperature effects | Neglects entropic contributions | Inaccurate representation of real synthesis environments |

| Material dynamics | Oversimplifies decomposition pathways | Incorrect stability assessments for complex systems |

The Metastability Challenge

A critical limitation of thermodynamic proxies is their inability to properly contextualize metastable materials. Research has established a thermodynamic upper limit on the energy scale for synthesizable metastable polymorphs, defined relative to the amorphous state [22] [23]. This amorphous limit is highly chemistry-dependent and cannot be captured by simple formation energy thresholds. The existence of this limit explains why some metastable materials within the thermodynamic stability window remain unsynthesizable while others with higher energies can be successfully synthesized through specialized pathways that provide kinetic stabilization.

Emerging Alternatives and Methodological Advances

Machine Learning Approaches

Next-generation synthesizability prediction has increasingly adopted machine learning frameworks that learn complex patterns directly from materials data without relying on simplified physical proxies:

- SynthNN: A deep learning model that leverages the entire space of synthesized inorganic compositions using learned atom embeddings, achieving 7× higher precision than DFT-based formation energy approaches and outperforming human experts in discovery tasks [19]

- SynCoTrain: A dual-classifier framework employing Positive and Unlabeled (PU) Learning with graph convolutional neural networks (ALIGNN and SchNet) to address the absence of confirmed negative examples, demonstrating robust performance on oxide crystals [20]

- Integrated composition-structure models: Unified models that combine compositional descriptors from transformer architectures with structural features from graph neural networks, achieving state-of-the-art performance through rank-average ensembling [21]

Experimental Validation of Advanced Approaches

Recent experimental studies demonstrate the superior practical utility of these emerging approaches. A synthesizability-guided pipeline applied to over 4.4 million candidate structures identified 24 highly synthesizable targets, of which 7 were successfully synthesized and characterized—a notable success rate for novel material discovery [21]. This pipeline integrated compositional and structural synthesizability scores with synthesis pathway prediction, highlighting the importance of combining multiple synthesizability signals rather than relying on single proxy metrics.

Practical Implementation and Workflow Integration

Advanced synthesizability models are designed for seamless integration into computational materials discovery pipelines. The typical workflow involves:

- Data curation from structured databases (Materials Project, ICSD) with careful labeling of synthesizable and unsynthesizable compositions

- Feature extraction using composition-only encoders or structure-aware graph neural networks

- Model training with positive-unlabeled learning strategies to address the inherent class imbalance

- Rank-based screening of candidate materials using ensemble approaches

- Experimental prioritization focusing on highly-ranked candidates with feasible synthesis pathways

This integrated approach enables rapid screening of millions of candidate structures while maintaining practical relevance for experimental synthesis.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SynthNN Training Protocol

The SynthNN model employs a specific methodological framework for synthesizability prediction [19]:

- Data Source: Crystalline inorganic materials from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)

- Representation: atom2vec embeddings that learn optimal chemical representations directly from data

- Training Approach: Semi-supervised learning with artificially generated unsynthesized materials

- Learning Framework: Positive-unlabeled (PU) learning that probabilistically reweights unlabeled examples

- Hyperparameter: N_synth controls the ratio of artificial to synthesized formulas during training

- Validation: Benchmarking against random guessing and charge-balancing baselines

This protocol enables the model to learn complex chemical principles such as charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity directly from data without explicit programming of chemical rules.

SynCoTrain Co-training Methodology

The SynCoTrain framework implements a dual-classifier approach with the following experimental protocol [20]:

- Architecture: Two complementary graph convolutional neural networks (SchNet and ALIGNN)

- Data Processing: Oxide crystals from ICSD accessed through Materials Project API, filtered by oxidation states

- Feature Engineering: ALIGNN encodes atomic bonds and bond angles; SchNet uses continuous convolution filters

- Training Process: Iterative co-training where classifiers exchange predictions to reduce model bias

- Base Learning: Mordelect and Vert PU Learning method applied at each co-training step

- Evaluation: Recall-based performance assessment on internal and leave-out test sets

This methodology specifically addresses the generalization challenge in synthesizability prediction by leveraging multiple models with complementary inductive biases.

Integrated Model Training Procedure

The combined composition-structure model described in recent literature follows this experimental protocol [21]:

- Data Curation: 49,318 synthesizable and 129,306 unsynthesizable compositions from Materials Project

- Composition Encoder: Fine-tuned MTEncoder transformer operating on chemical stoichiometry

- Structure Encoder: Fine-tuned JMP graph neural network processing crystal structures

- Training Objective: Binary classification minimizing cross-entropy loss with early stopping

- Ensemble Method: Rank-average (Borda fusion) of composition and structure predictions

- Screening Application: Ranking of candidates by aggregating probabilities across models

This protocol demonstrates how complementary signals from composition and structure can be integrated to enhance synthesizability prediction accuracy.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesizability Prediction

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Source of synthesized material data | Training data for supervised and PU learning approaches |

| Materials Project API | Access to computational material data | Source of unlabeled/theoretical compounds for training |

| Pymatgen library | Materials analysis and oxidation state determination | Data preprocessing and feature generation |

| atom2vec embeddings | Learned chemical representations | Feature learning for composition-based models |

| ALIGNN model | Graph neural network encoding bonds and angles | Structure-based synthesizability classification |

| SchNet model | Continuous-filter convolutional neural network | Alternative structure representation for co-training |

| MTEncoder transformer | Composition-only material representation | Compositional synthesizability scoring |

| JMP graph neural network | Pretrained crystal graph model | Structural descriptor learning for classification |

Traditional thermodynamic and charge-balancing proxies for predicting inorganic material synthesizability suffer from fundamental limitations that restrict their utility in modern materials discovery pipelines. Charge-balancing criteria prove excessively restrictive, incorrectly classifying most known materials as unsynthesizable, while thermodynamic stability metrics overlook critical kinetic and synthesis-condition factors that determine experimental feasibility. The emergence of machine learning approaches that learn synthesizability patterns directly from materials data represents a paradigm shift in predictive synthesis research. These data-driven models demonstrate superior performance by integrating multiple chemical and structural descriptors, successfully balancing precision and recall in ways that traditional proxies cannot achieve. As materials research increasingly leverages high-throughput computational screening to explore chemical space, moving beyond simplistic thermodynamic and charge-balancing heuristics toward sophisticated, integrated synthesizability models will be essential for realizing efficient and reliable materials discovery.

AI and Data-Driven Methodologies for Synthesis Planning

The discovery and synthesis of new materials are fundamental drivers of technological progress. Retrosynthesis planning—the process of deconstructing a target molecule or material into feasible precursor components—is a critical step in this pipeline. Traditional computational approaches, heavily reliant on expert-crafted rules and physical simulations, have struggled with the vast complexity and underdefined nature of synthetic chemistry, particularly for inorganic materials. The advent of machine learning (ML) has revolutionized this field, shifting the paradigm from manual design to data-driven prediction [24].

Early ML approaches predominantly framed retrosynthesis as a multi-label classification problem, where models would select precursors from a fixed set of classes encountered during training [8]. While effective for recapitulating known reactions, this formulation inherently limits a model's ability to propose novel precursors or explore uncharted regions of chemical space. This limitation represents a significant bottleneck for the predictive synthesis of novel inorganic materials, where discovery is the primary goal.

This technical guide examines the pivotal transition in the field from classification-based methods to more flexible ranking-based frameworks. We will explore how this shift, coupled with advanced model architectures and a deeper integration of chemical knowledge, is enhancing the generalizability and practical utility of ML-driven retrosynthesis, thereby addressing core challenges in predictive inorganic materials synthesis research.

The Limitations of the Classification Paradigm

The initial wave of ML for retrosynthesis, particularly for inorganic materials, largely treated precursor recommendation as a classification task. Models like ElemwiseRetro and Retrieval-Retro were trained to predict a set of precursors by classifying among dozens of curated precursor templates or a predefined set of known precursors [8] [25].

Core Conceptual Flaws

This paradigm suffers from two fundamental limitations that restrict its application in novel materials discovery:

- Inability to Propose Novel Precursors: A model operating as a multi-label classifier over a fixed set of precursors cannot recommend a precursor it did not see during training. Its predictions are restricted to recombining existing precursors into new combinations rather than identifying entirely new precursor compounds. This drastically limits its utility for discovering synthetic routes for never-before-seen materials [8].

- Disjoint Embedding Spaces: Many classification-based methods embed precursor and target materials in separate, disjoint latent spaces. This design hinders the model's ability to generalize and understand the underlying chemical compatibility between a target and a potential precursor, as they are not represented within a unified chemical context [8].

Practical Consequences for Materials Discovery

These conceptual flaws translate directly into practical shortcomings. As noted in a critical reflection on text-mined synthesis data, ML models trained on historical literature data often fail to provide substantially new guiding insights because they are effectively learning to imitate past human experimentation patterns, which are culturally and anthropogenically biased [26]. The classification paradigm inherently reinforces these biases, as the model's vocabulary of possible actions is limited to the chemical building blocks used in the past.

The Ranking-Based Formulation: A Paradigm Shift

To overcome these limitations, a new framework reformulates the retrosynthesis problem as a pairwise ranking task. Instead of classifying from a fixed set, the model learns to evaluate and rank the compatibility between a target material and any given precursor candidate.

Theoretical Foundation

The core learning objective changes from multi-label classification to learning a pairwise ranker. For a target material ( T ), the model aims to learn a function that assigns a compatibility score to a precursor candidate ( P ). The resulting scores are used to rank potential precursor sets ( (\mathbf{S}1, \mathbf{S}2, \ldots, \mathbf{S}K) ), where each set ( \mathbf{S} = {P1, P2, \ldots, Pm} ) consists of ( m ) individual precursors [8].

This reformulation offers significant advantages:

- Increased Flexibility: The model can evaluate precursors not present in the training data, a crucial capability for exploring novel compounds.

- Joint Embedding Space: Both precursors and target materials are embedded into a unified latent space, enhancing generalization to new chemical systems.

- Improved Data Efficiency: The pairwise scoring approach allows for custom sampling strategies, including negative sampling, to better handle the high class imbalance typical in chemical datasets [8].

Implementation: The Retro-Rank-In Framework

The Retro-Rank-In model exemplifies this ranking-based approach. It consists of two core components:

- A composition-level transformer-based materials encoder: This generates chemically meaningful representations for both target materials and precursors.

- A pairwise Ranker: This evaluates the chemical compatibility between the target material and precursor candidates, predicting the likelihood that they can co-occur in a viable synthetic route [8].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Retrosynthesis Paradigms

| Feature | Classification Paradigm | Ranking Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Core Formulation | Multi-label classification over a fixed set | Pairwise ranking of candidate precursors |

| Novel Precursor Discovery | Not possible | Enabled |

| Embedding Space | Disjoint for targets and precursors | Unified joint space |

| Handling Data Imbalance | Challenging | Custom negative sampling strategies |

| Model Example | Retrieval-Retro [25] | Retro-Rank-In [8] |

Advanced Architectures and Hybrid Methodologies

The evolution from classification to ranking has been accompanied by significant advancements in model architecture, which further boost performance and generalizability.

Retrieval-Augmented and Knowledge-Enhanced Models

Modern frameworks often combine the ranking formulation with sophisticated retrieval mechanisms to incorporate broader chemical knowledge.

Retrieval-Retro employs a dual-retrieval system. It first identifies reference materials that share similar precursors with the target and then suggests precursors based on thermodynamic data, specifically formation energies. The model uses self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms to compare target and reference materials, finally predicting precursors via a multi-label classifier. This hybrid approach unifies data-driven methods with domain-informed thermodynamic principles [25].

RetroExplainer introduces a highly interpretable, graph-based approach for organic retrosynthesis. It formulates the task as a molecular assembly process guided by a multi-sense and multi-scale Graph Transformer (MSMS-GT). The framework uses structure-aware contrastive learning and dynamic adaptive multi-task learning to achieve robust performance, outperforming many state-of-the-art methods on benchmark datasets [27].

Exploiting Chemical Knowledge and Interpretability

A key trend is the move away from "black box" models towards more interpretable and chemically grounded systems.

- Re-ranking with Energy-Based Models (EBMs): An alternative to ranking is to use an EBM to re-rank the suggestions from a proposal model. The EBM assigns a lower "energy" to more feasible reactions, implicitly learning factors like reactivity and functional group compatibility from data. This has been shown to improve the top-1 accuracy of models like RetroSim and NeuralSym significantly [28].

- Bond Augmentation for Chemical Reasoning: Some models incorporate retrosynthetic analysis directly into their learning process. For instance, one method uses a chemically inspired bond augmentation technique during contrastive learning, where bonds likely to break during retrosynthesis are treated as positive pairs. This helps the model capture the inherent properties of chemical reactions [29].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Rigorous evaluation is essential for comparing the performance of different retrosynthesis models. The field has developed standard benchmarks and protocols to this end.

Data Preparation and Splitting

For inorganic retrosynthesis, datasets are often constructed from literature sources, text-mined recipes, and computational databases like the Materials Project [8] [26] [25]. A critical step is designing dataset splits that truly test a model's generalizability:

- Challenging Splits: To avoid data leakage and over-optimistic performance, datasets are split to mitigate the effects of duplicate data and reactant overlaps. This includes "year splits," where models are trained on older data and tested on newer publications, simulating a more realistic discovery environment [8] [25].

- Similarity-Based Splits: For organic retrosynthesis, the Tanimoto similarity splitting method is used to ensure that molecules in the test set have a structural similarity below a set threshold (e.g., 0.4, 0.5, or 0.6) to those in the training set. This prevents the model from simply memorizing reactions for highly similar products [27].

Performance Metrics and Comparative Results

The standard metric for evaluating one-step retrosynthesis models is top-(k) exact-match accuracy. This measures whether the ground-truth set of reactants appears within the model's top (k) suggestions.

Table 2: Top-k Accuracy (%) of Selected Models on the USPTO-50K Benchmark

| Model | Top-1 | Top-3 | Top-5 | Top-10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetroExplainer [27] | 54.2% (Known) | 73.9% (Known) | 79.7% (Known) | 84.9% (Known) |

| RetroSim (Re-ranked) [28] | 51.8% | - | - | - |

| NeuralSym (Re-ranked) [28] | 51.3% | - | - | - |

For inorganic models, the key differentiator is performance on generalizability tasks. Retro-Rank-In, for instance, demonstrated its capability by correctly predicting the verified precursor pair \ce{CrB + \ce{Al}} for the target \ce{Cr2AlB2}, despite never having seen this specific pair during training—a capability absent in prior classification-based work [8].

Visualizing the Ranking-Based Retrosynthesis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a ranking-based retrosynthesis model like Retro-Rank-In, highlighting the flow from a target material to a ranked list of precursor candidates.

Diagram 1: Ranking-based retrosynthesis workflow.

The development and application of modern retrosynthesis models rely on a suite of computational "reagents" and resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ML-Driven Retrosynthesis

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| USPTO Datasets (e.g., USPTO-50K, USPTO-MIT) [29] [27] | Reaction Dataset | Benchmark dataset for training and evaluating organic retrosynthesis models. |

| Materials Project (MP) [8] [30] [31] | Computational Database | Provides calculated structural and thermodynamic data for hundreds of thousands of inorganic materials, used for training and as a source of domain knowledge. |

| Text-mined Synthesis Recipes [26] | Literature-Derived Dataset | A collection of synthesis procedures extracted from scientific papers, used to train data-driven models on historical experimental knowledge. |

| Composition Encoder (e.g., Transformer) [8] | Model Component | Generates numerical representations (embeddings) of inorganic materials based on their elemental composition. |

| Pairwise Ranker [8] | Model Component | The core of the ranking paradigm; scores the compatibility between a target material and a candidate precursor. |

| Neural Reaction Energy (NRE) Retriever [25] | Domain-Knowledge Module | Incorporates thermodynamic principles (e.g., formation energy) into the model to assess reaction feasibility. |

The transition from classification to ranking represents a significant maturation of machine learning's role in retrosynthesis planning. This shift directly addresses a fundamental challenge in predictive inorganic materials synthesis: the need to propose and evaluate novel precursor combinations that fall outside the scope of historical data. Ranking-based frameworks, especially when enhanced with retrieval mechanisms and deep chemical knowledge, provide a more flexible and powerful foundation for exploring the vast and untapped regions of chemical space.

Future progress will likely be driven by several key trends. The development of foundational generative models for materials, such as MatterGen [31], points towards a future where generation, stability prediction, and synthesis planning are tightly integrated. Furthermore, the push for greater model interpretability [27] will be crucial for building trust with experimental chemists and deriving new scientific insights from the models' predictions. Finally, as critically noted by Sun et al. [26], the field must continue to improve the volume, variety, and veracity of the underlying data, moving beyond the biases of historical literature to unlock truly novel and efficient synthetic pathways.

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are fundamental to advancements in renewable energy, electronics, and other modern technologies. However, the synthesis planning for these materials—the process of identifying simpler precursor compounds that can react to form a desired target material—remains a critical bottleneck [8]. Traditional machine learning (ML) approaches have struggled to generalize beyond their training data, fundamentally limiting their utility in discovering new materials and reactions [32]. This whitepaper examines how ranking-based frameworks, particularly the novel Retro-Rank-In model, reformulate the retrosynthesis problem to overcome training set limitations and enable genuine discovery of novel precursor combinations not present in model training data.

The exponential scaling of compute needed for physical simulation of atomic-scale thermodynamics and kinetics has created a compelling opportunity for ML approaches to bridge this knowledge gap by learning directly from synthesis data [8]. Yet, until recently, these approaches have been constrained by their formulation as multi-label classification tasks, which inherently prevents them from recommending precursors outside their predefined training vocabulary [8]. The Retro-Rank-In framework represents a paradigm shift from classification to ranking, enabling unprecedented generalization capabilities that promise to accelerate inorganic materials synthesis discovery.

Limitations of Traditional Machine Learning Approaches

The Multi-Label Classification Bottleneck

Existing ML approaches for inorganic retrosynthesis share significant limitations that restrict their real-world applicability. Most critically, they lack the ability to incorporate new precursors, which is essential for experimental workflows searching for novel compounds [8]. For instance, the Retrieval-Retro model cannot recommend precursors outside its training set because they are represented through one-hot encoding in its multi-label classification output layer [8]. This architectural design restricts the model to recombining existing precursors into new combinations rather than enabling predictions involving entirely novel precursors not encountered during training.

Table 1: Limitations of Previous Retrosynthesis Approaches

| Model | Discover New Precursors | Chemical Domain Knowledge | Extrapolation to New Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| ElemwiseRetro | ✗ | Low | Medium |

| Synthesis Similarity | ✗ | Low | Low |

| Retrieval-Retro | ✗ | Low | Medium |

| Retro-Rank-In | ✓ | Medium | High |

Disjoint Embedding Spaces and Limited Domain Knowledge Incorporation

Prior methods struggle to effectively incorporate broader chemical knowledge and demonstrate limited extrapolation capabilities due to their embedding design. These methods typically embed precursor and target materials in disjoint spaces, which hinders their ability to generalize effectively across the chemical landscape [8]. While some approaches like Retrieval-Retro utilize a Neural Reaction Energy retriever trained to predict formation enthalpy using computed compounds databases, this approach does not fully exploit available domain-specific data [8]. The combination of these factors—inability to handle new precursors, disjoint embedding spaces, and limited domain knowledge integration—has created a significant barrier to practical AI-assisted materials discovery.

Ranking-Based Reformulation: The Retro-Rank-In Framework

Core Architectural Innovations

Retro-Rank-In addresses fundamental limitations of previous approaches through a novel framework consisting of two core components: a composition-level transformer-based materials encoder that generates chemically meaningful representations of both target materials and precursors, and a Ranker that evaluates chemical compatibility between target material and precursor candidates [8]. This architecture enables several key advancements that overcome training set limitations.

The framework reformulates retrosynthesis as a pairwise ranking problem rather than multi-label classification. The Ranker is specifically trained to predict the likelihood that a target material and a precursor candidate can co-occur in viable synthetic routes [8]. During inference, this enables Retro-Rank-In to select new precursors not seen during training, which is crucial for exploring novel compounds as it allows incorporation of a larger chemical space into the search for new synthesis recipes [8].

Unified Embedding Space and Domain Knowledge Integration

Unlike previous approaches that used disjoint embedding spaces for precursors and targets, Retro-Rank-In embeds both precursors and target materials within a unified embedding space, significantly enhancing the model's generalization capabilities [8]. The model leverages large-scale pretrained material embeddings to integrate implicit domain knowledge of formation enthalpies and related material properties, providing a more chemically-informed foundation for precursor recommendations [8].

Table 2: Key Components of the Retro-Rank-In Framework

| Component | Function | Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| Composition-level Transformer | Generates chemically meaningful representations | Creates unified embedding space for targets and precursors |

| Pairwise Ranker | Evaluates chemical compatibility | Learns co-occurrence likelihood in viable synthetic routes |

| Material Encoder | Embeds elemental compositions | Leverages pretrained knowledge of material properties |

Quantitative Performance and Experimental Validation

Experimental Design and Evaluation Metrics

Retro-Rank-In was evaluated on challenging retrosynthesis dataset splits specifically designed to mitigate data duplicates and overlaps, providing a rigorous test of generalizability [8]. The evaluation focused on the model's ability to predict a ranked list of precursor sets for a given target material, with historically reported synthesis routes from scientific literature considered correct predictions [8]. The ranking indicates the predicted likelihood of each precursor set forming the target material, moving beyond simple binary classification.

The key innovation in evaluation was testing the model's ability to recommend precursor combinations completely unseen during training, a capability absent in prior work. For example, the model was tested on its ability to predict verified precursor pairs for novel compounds despite never having seen these specific combinations in its training data [8].

Performance Comparison with Baseline Models

Experimental results demonstrate that Retro-Rank-In sets a new state-of-the-art, particularly in out-of-distribution generalization and candidate set ranking [32]. In one notable case, for the target compound Cr₂AlB₂, Retro-Rank-In correctly predicted the verified precursor pair CrB + Al despite never encountering them during training [32] [8]. This capability was absent in all prior work and represents a significant advancement toward practical AI-assisted materials discovery.