Overcoming Kinetic Barriers in Organic Synthesis: Strategies, Methodologies, and Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of kinetic barriers in organic synthesis, addressing the critical challenges and innovative solutions for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including the Arrhenius equation and activation energy, and progresses to advanced methodologies like high-throughput computational analysis and kinetic decoupling-recoupling strategies. The content details practical applications for troubleshooting and optimizing reactions, alongside rigorous validation techniques through kinetic studies and isotope effects. By synthesizing current research and future directions, this review serves as an essential resource for designing efficient synthetic routes, ultimately accelerating the development of pharmaceuticals and novel materials.

Overcoming Kinetic Barriers in Organic Synthesis: Strategies, Methodologies, and Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of kinetic barriers in organic synthesis, addressing the critical challenges and innovative solutions for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including the Arrhenius equation and activation energy, and progresses to advanced methodologies like high-throughput computational analysis and kinetic decoupling-recoupling strategies. The content details practical applications for troubleshooting and optimizing reactions, alongside rigorous validation techniques through kinetic studies and isotope effects. By synthesizing current research and future directions, this review serves as an essential resource for designing efficient synthetic routes, ultimately accelerating the development of pharmaceuticals and novel materials.

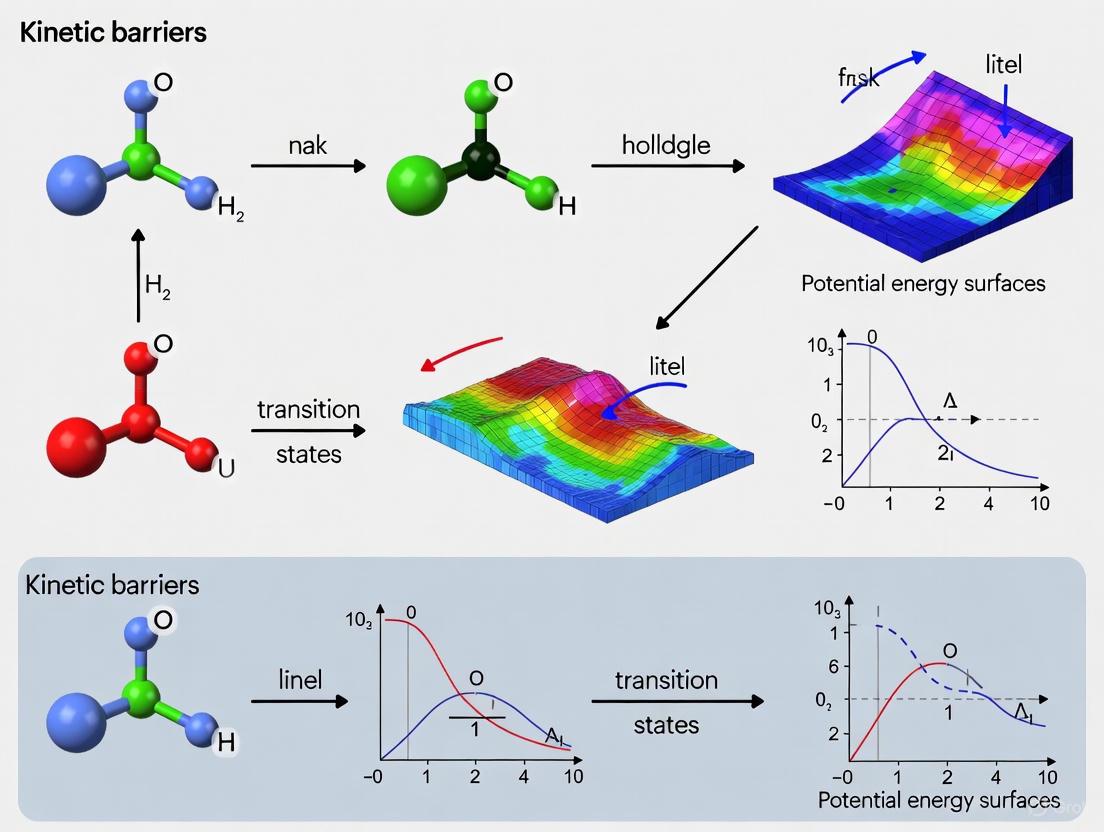

The Fundamentals of Kinetic Barriers: From Basic Principles to High-Energy Transformations

In synthetic organic chemistry, the feasibility of a transformation is governed not only by its thermodynamic favorability but also by its kinetic accessibility. The central concept in understanding reaction rates is the activation energy (Ea), defined as the minimum amount of energy that must be provided to a system for a chemical reaction to occur [1]. This energy barrier must be overcome by reactant molecules to transform into products [2]. For professional researchers in drug development and materials science, manipulating these kinetic barriers is a daily reality; the inability to lower sufficiently high activation energies can render a promising synthetic pathway impractical, halting the development of a potential pharmaceutical candidate. The Arrhenius equation provides the fundamental quantitative relationship linking a reaction's rate constant to its activation energy and temperature, serving as an indispensable tool for predicting reaction behavior and designing synthetic protocols [3]. This guide explores the core principles of activation energy and the Arrhenius equation, framing them within the critical context of modern organic synthesis research.

Theoretical Foundations

The Concept of Activation Energy

Activation energy is the energy threshold separating reactants from products. On a reaction coordinate diagram, it is the vertical distance from the energy of the reactants to the energy of the transition state, the highest-energy point on the reaction pathway [1]. At a given temperature, a sample of molecules possesses a distribution of kinetic energies. Only those molecules with kinetic energy equal to or greater than the activation energy can participate in the reaction [1] [4]. This explains why higher activation energies generally result in slower reaction rates, as fewer molecules possess the requisite energy to surmount the barrier at a specific temperature [5].

The concept was formally introduced in 1889 by the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius [1]. It is crucial to distinguish kinetics from thermodynamics: a reaction may be highly exergonic (thermodynamically favorable) yet proceed imperceptibly slowly due to a prohibitively high activation energy [4]. A reaction's overall free energy change is independent of its activation energy and is not altered by it [1].

The Arrhenius Equation

The Arrhenius equation provides the mathematical basis for the temperature dependence of reaction rates. Its fundamental form is:

[ k = A e^{-E_a / (RT)} ]

Where:

- ( k ) is the rate constant of the reaction.

- ( A ) is the pre-exponential factor (or frequency factor), which represents the frequency of collisions with the correct molecular orientation.

- ( E_a ) is the activation energy (typically in kJ/mol or kcal/mol).

- ( R ) is the universal gas constant.

- ( T ) is the absolute temperature in Kelvin [3].

The term ( e^{-Ea / (RT)} ) represents the fraction of molecular collisions that possess an energy greater than or equal to ( Ea ) at temperature ( T ) [3] [4]. A useful rule of thumb derived from the Arrhenius equation is that for many common reactions, the rate approximately doubles with every 10 °C rise in temperature [3] [4].

The equation can be linearized by taking the natural logarithm of both sides:

[ \ln k = \ln A - \frac{E_a}{R} \frac{1}{T} ]

This form is the basis of the Arrhenius plot (( \ln k ) versus ( 1/T )), which yields a straight line with a slope of ( -E_a / R ) and a y-intercept of ( \ln A ) [3]. This plot is a standard tool for experimentally determining the activation energy and pre-exponential factor for a reaction.

Advanced Theoretical Models

While the Arrhenius equation is empirically powerful, more sophisticated models provide a deeper mechanistic understanding.

Transition State Theory: The Eyring equation, derived from transition state theory, describes the rate constant as: [ k = \frac{kB T}{h} e^{-\Delta G^{\ddagger} / (RT)} ] where ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, ( h ) is Planck's constant, and ( \Delta G^{\ddagger} ) is the Gibbs energy of activation [3]. This formulation partitions the activation barrier into enthalpic (( \Delta H^{\ddagger} )) and entropic (( \Delta S^{\ddagger} )) components, offering insights into the nature of the transition state [1] [3]. For a one-step unimolecular reaction, an approximate relationship exists where ( E_a \approx \Delta H^{\ddagger} + RT ) [1].

Collision Theory: This theory models reactions as occurring when molecules collide with sufficient energy and proper orientation. The rate constant is given by ( k = \rho z e^{-E_a / (RT)} ), where ( z ) is the collision frequency and ( \rho ) is the steric factor accounting for orientation [3].

Challenges in Solid-State Kinetics: The application of the Arrhenius equation to reactions in the solid state is less straightforward. The Maxwell-Boltzmann energy distribution, foundational to the Arrhenius model, may not perfectly apply to the immobilized constituents of a crystal lattice, and reactions often proceed through complex multi-step processes at interfaces [6]. Despite these theoretical reservations, the Arrhenius equation remains widely used in solid-state kinetics as a practical empirical tool [6].

Experimental Determination and Kinetic Analysis

Methodologies for Determining Activation Energy

A core task in reaction optimization is the experimental determination of ( E_a ). The most common method involves measuring the rate constant ( k ) at several different temperatures.

- Standard Protocol for Solution-Phase Ea Determination via Arrhenius Plot:

- Reaction Monitoring: Conduct the reaction under study at a minimum of four different, controlled temperatures (e.g., 30°C, 40°C, 50°C, 60°C). The reaction should be performed under identical initial concentrations and conditions at each temperature.

- Rate Constant Calculation: For each temperature, determine the value of the rate constant ( k ). The method depends on the reaction order. For a first-order reaction, ( k ) can be obtained from the slope of a plot of ( \ln[\text{Reactant}] ) versus time.

- Data Plotting: Create an Arrhenius plot by graphing ( \ln k ) on the y-axis against the reciprocal of the absolute temperature, ( 1/T ) (in Kâ»Â¹), on the x-axis.

- Linear Regression: Fit the data points using linear regression. The slope ( m ) of the resulting line is equal to ( -Ea / R ).

- Calculation: Calculate the activation energy using ( Ea = -m \times R ), where ( R = 8.314 \ \text{J} \ \text{mol}^{-1} \ \text{K}^{-1} ). The y-intercept of the line provides the value of ( \ln A ) [3].

Quantitative Data in Organic Synthesis

The magnitude of the activation energy dictates the practical temperature and time required for a transformation. Recent research has expanded the scope of accessible barriers.

Table 1: Activation Energy Barriers and Corresponding Reaction Conditions

| Activation Energy (Ea) | Typical Temperature Range | Typical Half-Life (tâ‚/â‚‚) Estimate | Feasibility in Conventional Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 20 kcal molâ»Â¹ | Room Temperature to 80°C | Seconds to Hours | High; routine |

| 20 - 40 kcal molâ»Â¹ | 50°C to 150°C | Minutes to Days | Moderate; common with heating |

| > 40 kcal molâ»Â¹ | > 150°C (conventional limit) | Days to Years | Low; considered "forbidden" [7] |

| 50 - 70 kcal molâ»Â¹ | ~250°C to 500°C | Minutes at ~500°C [7] | Very Low; requires specialized high-temperature methods [7] |

A landmark 2025 study by Shaydullin et al. demonstrated that activation energy barriers of 50–70 kcal molâ»Â¹, previously considered inaccessible in solution-phase synthesis, can be overcome using high-temperature capillary synthesis (HTCS) at temperatures up to 500°C, achieving product yields up to 50% in as little as five minutes [7].

Table 2: Calculated Gibbs Activation Energies (ΔG‡) for Pyrazole Isomerization [7]

| Substrate | Calculated ΔG‡ (kcal molâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|

| 1,5-Diphenylpyrazole (N1) | ~56.0 |

| 3-(1-Phenyl-1H-pyrazol-2-yl)phenol | 55.4 |

| 1-(2-Fluoroethyl)-3-methyl-1H-pyrazole | 68.3 |

Overcoming Kinetic Barriers in Synthesis

Catalysis

Catalysts are substances that increase the rate of a reaction without being consumed by modifying the reaction pathway and lowering the activation energy [1]. They achieve this by forming the transition state in a more favorable manner, often by stabilizing it through stabilizing interactions like hydrogen bonding or van der Waals forces within the catalyst's active site [1]. A crucial point for chemists designing catalytic systems is that a catalyst does not change the energies of the original reactants or products and therefore does not alter the reaction's equilibrium; it only lowers the energy barrier, accelerating the rate at which equilibrium is reached [1]. Organocatalysis, the use of small organic molecules to catalyze reactions, has become a powerful synergistic tool when combined with other activation strategies like mechanochemistry, offering high yields and stereoselectivities while often operating under solvent-free conditions [8].

High-Temperature Methods

When catalytic solutions are not available or effective, thermal energy can be used to help a greater fraction of molecules overcome the activation barrier. High-temperature capillary synthesis (HTCS) is a recently demonstrated method to access extremely high activation energies in solution.

- Detailed HTCS Protocol for High-Barrier Reactions [7]:

- Capillary Preparation: Use a standard glass capillary, such as a 230 mm Duran pipette.

- Reaction Loading: Prepare a solution of the reactant in a high-boiling solvent like p-xylene.

- Filling Degree: Load the capillary with the reaction solution to occupy approximately 25% of its total volume. This leaves 75% free volume as headspace and is critical for pressure management; a 50% fill level led to a 50% capillary failure rate under high-temperature conditions [7].

- Sealing: Flame-seal the open end of the capillary to create a closed system.

- Heating: Place the sealed capillary in a pre-heated oven or sand bath at the target temperature (e.g., 400–500°C) for a defined period (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Work-up: After heating, carefully cool the capillary to room temperature. Open the capillary and extract the reaction mixture for analysis (e.g., NMR, GC-MS) and purification.

Alternative Energy Inputs

Beyond conventional heating and catalysis, several non-classical activation strategies have become essential in the modern synthetic chemist's toolkit for overcoming kinetic barriers.

- Mechanochemistry: This technique uses mechanical energy (e.g., from ball-milling) to induce chemical reactions. It is highly effective for solvent-free synthesis and can promote reactions that are challenging in solution, often leading to shorter reaction times and different selectivity [8].

- Microwave Irradiation: Microwave heating provides rapid, internal heating of the reaction mixture, often allowing for significantly reduced reaction times and higher yields compared to conventional conductive heating [8].

- Photocatalysis: This approach uses light (often visible light) to excite a photocatalyst, which then facilitates electron or energy transfer processes, accessing reactive intermediates and pathways with unique activation barriers [8].

- Quantum Tunneling: In certain reactions, particularly those involving hydrogen transfer, nuclei can penetrate the activation energy barrier rather than surmount it. This "quantum tunneling" effect can dominate the reaction kinetics at low temperatures or for very high barriers, offering an alternative pathway that is independent of temperature [9].

Essential Research Tools and Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Kinetic Analysis |

|---|---|

| Sealed Glass Capillaries | Enables high-temperature solution-phase reactions (up to ~500°C) by withstanding high internal pressure [7]. |

| High-Boiling Point Solvents (e.g., p-xylene) | Acts as a reaction medium at extreme temperatures without complete vaporization, maintaining a solution-phase environment [7]. |

| Ball Mill (HSBM/Planetary Mill) | Provides mechanochemical energy input for solvent-free reactions or reactions with minimal solvent (LAG) [8]. |

| Organocatalysts (e.g., Proline-based Dipeptides) | Lowers activation energy for specific transformations like aldol reactions, often with high stereoselectivity [8]. |

| Metallic Catalysts (e.g., CuCl) | Catalyzes coupling reactions (e.g., of isatines with isocyanates) under mild, solvent-free mechanochemical conditions [8]. |

| Ac-DEMEEC-OH | AcAsp-Glu-Met-Glu-Glu-Cys Peptide |

| Aristolactam A IIIa | Aristolactam A IIIa, MF:C16H11NO4, MW:281.26 g/mol |

Visualizing Kinetic Concepts

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and methodologies discussed.

A deep understanding of kinetic barriers, as defined by the Arrhenius equation and the concept of activation energy, is fundamental to advancing organic synthesis. For the drug development professional, this knowledge translates directly into the ability to design feasible synthetic routes, optimize reaction conditions for scale-up, and explore novel chemical spaces. The contemporary synthetic chemist's arsenal is no longer limited to traditional heating and solvent-based catalysis. The demonstrated ability to access previously "forbidden" activation energies up to 70 kcal molâ»Â¹ via high-temperature methods, coupled with the strategic use of mechanochemistry, photocatalysis, and organocatalysis, represents a paradigm shift. These tools empower researchers to deliberately engineer reaction conditions that circumvent kinetic limitations, thereby expanding the horizon of possible molecules and materials. As synthetic challenges grow more complex, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, the continued innovative application and integration of these kinetic principles will be crucial for developing the efficient and sustainable synthetic methodologies of the future.

The Critical Role of the Rate-Determining Step in Complex Reaction Mechanisms

The rate-determining step (RDS) serves as the fundamental kinetic bottleneck in complex chemical reactions, directly governing the overall reaction rate and determining the experimental rate law. This whitepaper explores the critical role of the RDS within the broader context of kinetic barriers in organic synthesis research. By examining fundamental principles, quantitative kinetic parameters, and advanced experimental protocols, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for identifying and characterizing these pivotal steps in reaction mechanisms. The insights gained from such analyses are indispensable for rational reaction design and optimization in complex synthetic pathways, particularly in pharmaceutical development where reaction efficiency directly impacts process viability and scalability.

Most chemical reactions do not proceed in a single step but rather through a series of elementary reactions known as the reaction mechanism. The sequence of actual events that take place as reactant molecules are converted into products constitutes the mechanism of a chemical reaction [10]. Within these multistep pathways, individual steps progress at different rates, and the slowest elementary step—the rate-determining step—acts as the kinetic bottleneck that limits the overall reaction rate [11] [12]. This concept can be analogized to a funnel, where the rate at which water flows through is determined by the width of the neck rather than how quickly water is poured in [11]. For researchers exploring kinetic barriers in organic synthesis, identifying the RDS is paramount for understanding, optimizing, and predicting reaction behavior under various conditions, enabling more efficient synthetic route design in drug development projects.

Fundamental Principles of the Rate-Determining Step

Definition and Conceptual Foundation

The rate-determining step (RDS), also termed the rate-limiting step, is the slowest step in a sequence of elementary reactions that constitutes a reaction mechanism [12] [13]. As the step with the highest activation energy barrier, it determines the maximum possible rate for the entire reaction sequence. A crucial distinction is that not all reactions feature a single RDS; some complex mechanisms, particularly chain reactions, may not have one clearly defined rate-limiting step [12]. When present, the RDS represents the kinetic bottleneck of the process, meaning that no matter how fast other steps proceed, the overall reaction cannot occur faster than this slowest transformation [14].

Relationship Between RDS and Reaction Rate Law

The identity of the RDS directly governs the mathematical form of the experimental rate law for the overall reaction. When the RDS is the first step in a mechanism, the rate law for the overall reaction typically matches that of this initial elementary step [14]. However, when the RDS is preceded by a rapid equilibrium step, the rate law becomes more complex, often involving concentrations of intermediates that can be expressed in terms of reactant concentrations using equilibrium constants [14] [12]. This relationship provides a critical connection between experimental observations and mechanistic hypotheses, allowing researchers to propose and validate reaction mechanisms based on experimentally determined rate laws.

Quantitative Analysis of Rate-Determining Steps

Key Kinetic Parameters

Understanding the kinetics of a reaction requires quantifying several fundamental parameters that define the energy landscape and progression of the chemical transformation. These parameters provide the mathematical framework for analyzing reaction mechanisms and identifying the RDS.

Table 1: Fundamental Kinetic Parameters in Reaction Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Relationship to RDS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy | Eâ‚ | Energy difference between reactants and transition state | The step with highest Eâ‚ is typically the RDS |

| Rate Constant | k | Temperature-dependent proportionality constant in rate law | The smallest k value indicates the RDS |

| Reaction Order | n | Sum of exponents in rate law expression | Determined by molecularity of the RDS |

| Half-life | tâ‚/â‚‚ | Time required for reactant concentration to halve | Inversely related to rate constant of RDS |

| Equilibrium Constant | K | Ratio of forward and reverse rate constants at equilibrium | For pre-equilibria, affects concentration of intermediate entering RDS |

Mathematical Treatment of Common Scenarios

The mathematical relationship between the RDS and the overall rate law varies depending on the mechanism. For a simple mechanism where the first step is rate-determining:

Overall rate = kâ‚[Reactantâ‚]ᵃ[Reactantâ‚‚]ᵇ

where kâ‚ is the rate constant for the first elementary step, and a and b are stoichiometric coefficients [14]. For mechanisms involving a pre-equilibrium followed by an RDS:

Overall rate = kâ‚‚K[Reactantâ‚]ᵃ[Reactantâ‚‚]ᵇ

where K is the equilibrium constant for the fast pre-equilibrium step, and kâ‚‚ is the rate constant for the RDS [12]. These relationships enable researchers to distinguish between possible mechanisms based on experimental kinetic data.

Experimental Methodologies for RDS Identification

Kinetic Analysis Techniques

Determining a reaction mechanism and identifying the RDS requires carefully designed experimental approaches that provide insight into the sequence of elementary steps. Several established methodologies enable researchers to probe these kinetic relationships.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Mechanistic and RDS Analysis

| Technique | Experimental Approach | Information Gained About RDS |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Progress Kinetic Analysis (RPKA) | Monitoring concentration changes over time under synthetically relevant conditions [15] | Determines reaction orders and identifies rate-influencing steps |

| Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) | Mathematical processing of concentration-time data [15] | Visualizes reaction orders and catalyst dependence |

| Kinetic Isotope Effects (KIE) | Replacing atoms with heavier isotopes (e.g., H→D, ¹²C→¹³C) and measuring rate changes [15] | Identifies bonds being broken/formed in the RDS |

| Eyring Analysis | Measuring reaction rates at different temperatures [15] | Determines activation parameters (ΔH‡, ΔS‡) for the RDS |

| Hammett Studies | Measuring rates with substituted aromatic compounds [15] | Probes electronic effects on the RDS transition state |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Kinetic Isotope Effect Study

Kinetic Isotope Effects (KIE) provide one of the most powerful experimental tools for identifying the RDS, particularly when bond cleavage occurs in the rate-limiting step. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for conducting intermolecular KIE studies:

Principle: Replacing an atom with a heavier isotope (e.g., ^1H with ^2H, ^12C with ^13C) and comparing reaction rates. A significant KIE (kâ‚—áµ¢gâ‚•â‚œ/kâ‚•â‚‘â‚ᵥᵧ > 1) indicates that the bond to the isotopic atom is being broken or formed in the RDS [15].

Materials and Equipment:

- Substrates with natural abundance isotopes and specifically deuterated analogs

- High-precision analytical instrumentation (NMR, LC-MS, or GC-MS)

- Thermostatted reaction vessels with precise temperature control (±0.1°C)

- Inert atmosphere equipment (glove box or Schlenk line) for air-sensitive reactions

Procedure:

- Prepare separate solutions of isotopically labeled and unlabeled substrates at identical concentrations.

- Initiate reactions under identical conditions (temperature, concentration, solvent).

- Monitor reaction progress using appropriate analytical techniques, ensuring equivalent sampling intervals.

- Determine rate constants (kâ‚—áµ¢gâ‚•â‚œ and kâ‚•â‚‘â‚ᵥᵧ) from linear regression of ln[concentration] versus time plots.

- Calculate KIE as kâ‚—áµ¢gâ‚•â‚œ/kâ‚•â‚‘â‚ᵥᵧ.

Interpretation: Primary KIEs (kH/kD > 2) suggest cleavage of a bond to the isotopic atom in the RDS, while secondary KIEs (kH/kD = 1-1.5) indicate rehybridization or hyperconjugation changes in the RDS transition state [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Kinetic Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in Mechanistic Studies | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds (²H, ¹³C, ¹âµN) | Probing bond cleavage/formation in RDS via Kinetic Isotope Effects [15] | Deuterated substrates for KIE studies; ¹³C-labeled compounds for natural abundance KIE |

| Hammett Correlation Compounds (para-/meta-substituted arenes) | Evaluating electronic effects on reaction rates [15] | Establishing Hammett plots to determine RDS transition state character |

| Sterically Hindered Probes (ortho-substituted arenes, bulky analogs) | Assessing steric requirements of the RDS | Differentiating between concerted and stepwise mechanisms |

| Radical Clocks (cyclopropyl-containing substrates) | Detecting radical intermediates | Testing for radical pathways in the mechanism |

| Chelating Additives (Lewis bases, ion-binding agents) | Probing for cationic intermediates | Identifying charged species in reaction pathway |

| TG-100435 | TG-100435, CAS:867330-68-5, MF:C26H25Cl2N5O, MW:494.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NIBR-17 | NIBR-17, MF:C18H20N8O2, MW:380.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Studies in RDS Determination

Nitrogen Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide Reaction

The reaction between NOâ‚‚ and CO to form NO and COâ‚‚ provides a classic example of RDS determination through experimental kinetics. The overall reaction is:

NO₂ + CO → NO + CO₂

If this occurred in a single step, the expected rate law would be:

Rate = k[NOâ‚‚][CO]

However, experimental determination reveals a different rate law:

Rate = k[NO₂]²

This observed second-order dependence on NOâ‚‚ and zero-order dependence on CO suggests a multistep mechanism where the RDS involves two NOâ‚‚ molecules [12]. The proposed mechanism is:

Step 1 (slow, rate-determining): NO₂ + NO₂ → NO + NO₃

Step 2 (fast): NO₃ + CO → NO₂ + CO₂

In this mechanism, the first step is significantly slower than the second, making it the RDS. The experimental rate law matches the rate law for this first step (Rate = kâ‚[NOâ‚‚]²), confirming it as the RDS [12]. The reactive intermediate NO₃ is consumed rapidly in the second step, and its concentration remains low throughout the reaction.

SN1 versus SN2 Nucleophilic Substitution

The distinction between unimolecular (SN1) and bimolecular (SN2) nucleophilic substitution mechanisms provides another clear illustration of RDS principles with significant implications for synthetic design.

For tert-butyl bromide hydrolysis with aqueous NaOH:

Step 1 (slow, rate-determining): (CH₃)₃C-Br → (CH₃)₃C⺠+ Brâ» (rate = kâ‚[(CH₃)₃C-Br])

Step 2 (fast): (CH₃)₃C⺠+ OH⻠→ (CH₃)₃C-OH

The experimental rate law (Rate = k[(CH₃)₃C-Br]) confirms the first step as RDS, consistent with an SN1 mechanism where carbocation formation is unimolecular and rate-determining [12]. The concentration of the nucleophile (OHâ») does not appear in the rate law.

In contrast, methyl bromide hydrolysis follows an SN2 mechanism with rate law Rate = k[CH₃Br][OHâ»], where a single bimolecular step is rate-determining [12]. This comparison highlights how the molecularity of the RDS directly determines the form of the rate law and provides insight into the reaction mechanism.

Advanced Concepts and Theoretical Frameworks

The Energetic Span Model

For complex catalytic cycles, the traditional RDS concept has been refined through the Energetic Span Model, which recognizes that in multistep reactions, the kinetic bottleneck may not always correspond to a single elementary step [16]. This model introduces the Degree of Rate Control (DRC), a quantitative measure that assesses how sensitive the overall reaction rate is to changes in the free energy of each intermediate and transition state [16]. The DRC for a transition state i is defined as:

X_RC,i = (k_i/r)(∂r/∂k_i) = [∂(ln r)/∂(ln k_i)]

where r is the net reaction rate and k_i is the rate constant for step i [16]. A step with DRC close to 1 has strong control over the reaction rate, while steps with DRC near 0 have minimal influence. This framework is particularly valuable for analyzing catalytic reactions where multiple transition states may collectively control the overall rate.

Reaction Coordinate Diagrams and Energy Landscapes

Reaction coordinate diagrams provide visual representations of energy changes throughout a reaction pathway, highlighting the relationship between the RDS and activation energies.

In this diagram, TSâ‚ represents the transition state for the RDS, characterized by the highest activation energy (Eâ‚) barrier. The intermediate exists in a potential energy well between the two transition states. It is crucial to note that the RDS is not necessarily the step with the highest absolute transition state energy but rather the step with the largest energy difference relative to the preceding intermediate [12]. This distinction becomes particularly important in mechanisms featuring stable reactive intermediates.

Implications for Organic Synthesis and Drug Development

Understanding the RDS provides powerful leverage for optimizing synthetic processes in pharmaceutical research. By identifying the kinetic bottleneck, medicinal chemists can strategically design interventions to accelerate slow steps through:

- Catalyst Design: Developing catalysts that specifically lower the activation energy of the RDS

- Reaction Conditions: Optimizing temperature, solvent, and concentration to facilitate the RDS

- Substrate Modification: Strategically modifying substrate structures to reduce steric or electronic barriers in the RDS

For instance, in palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions—ubiquitous in pharmaceutical synthesis—detailed mechanistic studies have revealed how the identity of the RDS can shift depending on substrate structure and reaction conditions [15]. This understanding has enabled the rational design of more efficient catalyst systems that specifically accelerate the rate-limiting step, leading to improved yields and reduced reaction times in API synthesis.

The rate-determining step represents a fundamental concept in reaction kinetics with profound implications for understanding and optimizing chemical processes in organic synthesis and drug development. Through careful application of kinetic analysis techniques—including reaction progress monitoring, isotope effects, and activation parameter determination—researchers can identify the RDS and use this knowledge to guide reaction optimization. The integration of traditional kinetic approaches with modern theoretical frameworks like the Degree of Rate Control provides a comprehensive toolkit for mechanistic analysis. As synthetic chemistry continues to advance toward increasingly complex transformations, particularly in the pharmaceutical sector, a deep understanding of rate-determining steps remains essential for the rational design of efficient synthetic methodologies.

High-temperature organic chemistry represents a transformative approach for accessing reaction pathways previously considered unattainable under conventional conditions. Traditional solution-based organic chemistry is typically constrained to temperatures below 200 °C, imposing a fundamental restriction on the accessible activation energies, typically limiting them to below 40 kcal molâ»Â¹ [17]. This thermodynamic limitation has long been a stumbling block in synthetic chemistry, restricting the exploration of novel transformations and molecular frameworks.

The kinetic barriers of 50–70 kcal molâ»Â¹ represent a class of reactions often deemed "forbidden" under standard laboratory conditions. This case study explores a groundbreaking methodology that overcomes these extreme barriers, focusing on the isomerization of N-substituted pyrazoles as a model reaction. By demonstrating the feasibility of accessing these challenging transformations, this research opens new frontiers in synthetic chemistry with broad implications for pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and materials science applications [17].

Mechanistic Background and Kinetic Analysis

Computational Insights into Pyrazole Isomerization

The isomerization of N-substituted pyrazoles serves as an exemplary model for studying high-energy barrier reactions due to its well-defined mechanistic pathway and significant activation energy requirements. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations reveal that the isomerization of N1 pyrazole exhibits a high activation Gibbs energy of approximately 56 kcal molâ»Â¹, with only minimal thermodynamic energy difference (ΔG < 5 kcal molâ»Â¹) between starting compound and product [17].

Table 1: DFT-Calculated Gibbs Activation Energies for Pyrazole Isomerization

| Pyrazole Substrate | Substituents | Activation Gibbs Energy (kcal molâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|

| 1,5-Diphenylpyrazole | Râ‚=Ph, Râ‚‚=Ph | 56.0 |

| 1-(2-Fluoroethyl)-3-methyl-1H-pyrazole | Alkyl/Fluoroalkyl | 68.3 |

| 3-(1-Phenyl-1H-pyrazol-2-yl)phenol | Aryl | 55.4 |

The introduction of electron-donating groups (EDG) or electron-withdrawing groups (EWG) at the Râ‚ or Râ‚‚ positions of 1,5-diphenylpyrazole does not lead to significant changes in the Gibbs activation energy (differences less than 5 kcal molâ»Â¹). This insensitivity to electronic effects underscores the substantial intrinsic barrier characteristic of these rearrangements [17].

Temperature-Kinetics Relationship

The relationship between activation energy, temperature, and reaction rate follows the Arrhenius equation, enabling estimation of the required temperatures to overcome specific energy barriers. For reactions with activation energies of 50–70 kcal molâ»Â¹, the half-reaction time (tâ‚/â‚‚) decreases dramatically with increasing temperature [17].

Table 2: Calculated Half-Reaction Times for Different Activation Energies

| Activation Energy (kcal molâ»Â¹) | Temperature (°C) | Half-Reaction Time (tâ‚/â‚‚) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 400 | ~10 hours |

| 50 | 500 | ~1 minute |

| 60 | 400 | ~100 years |

| 60 | 500 | ~1 hour |

| 70 | 500 | ~100 years |

The computational data suggest that the optimal isomerization temperature is approximately 500°C, which presents significant experimental challenges for conventional organic synthesis setups but is essential for achieving practical reaction times for high-energy barrier transformations [17].

Figure 1: Relationship between activation energy, temperature, and reaction kinetics

Experimental Methodology: High-Temperature Capillary Synthesis (HTCS)

HTCS Setup and Optimization

The High-Temperature Capillary Synthesis (HTCS) method implements organic synthesis at high temperatures and pressures in sealed glass capillaries, providing an accessible and reproducible approach for extreme-temperature chemistry. This technique leverages standard glass capillaries, making it easily reproducible in laboratories without specialized equipment [17].

The critical parameters for successful HTCS implementation include:

- Capillary Specifications: 8 cm long Duran pipettes (230 mm) with small-bore diameter to withstand high pressures up to 35 atm during heating

- Filling Volume Optimization: 25% filling volume (25 μL p-xylene solvent with 75 μL free volume) proved optimal, with all tested capillaries surviving the extreme conditions

- Pressure Management: At 500°C with 25% filling, internal pressure reaches approximately 32.3 bar, approaching supercritical conditions for the solvent system

The methodology is environmentally friendly, utilizing minimal solvent volumes and standard laboratory glassware while enabling access to unprecedented temperature regimes for solution-phase chemistry [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials and Equipment:

- Duran glass capillaries (8 cm length, small-bore diameter)

- p-Xylene solvent (anhydrous)

- Standard sealing apparatus

- High-temperature furnace capable of reaching 500°C

- High-pressure reactor for validation experiments

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Capillary Preparation: Load 25 μL of reactant solution in p-xylene into clean, dry Duran glass capillaries

- Sealing: Carefully seal both ends of the capillary using a standard glass-sealing torch, ensuring complete closure

- Reaction Setup: Place sealed capillaries in a secure containment system within the high-temperature furnace

- Thermal Treatment: Heat to target temperature (400-500°C) for predetermined reaction time (typically 5 minutes to 1 hour)

- Cooling and Workup: Carefully cool reaction vessels, open capillaries, and extract products using appropriate extraction techniques

- Analysis: Characterize products using standard physicochemical methods (NMR, LC-MS, etc.)

Safety Considerations:

- Implement appropriate shielding for high-pressure containment

- Use personal protective equipment rated for high-temperature glassware

- Conduct initial tests with minimal quantities to validate pressure tolerance

- Have established protocols for handling potential capillary failure during heating

Figure 2: HTCS experimental workflow

Results and Discussion

Experimental Validation and Performance

The HTCS methodology successfully demonstrated the feasibility of overcoming activation barriers of 50–70 kcal molâ»Â¹ in solution-phase organic synthesis. Using the isomerization of N-substituted pyrazoles as a model reaction, researchers achieved product yields up to 50% within remarkably short reaction times of approximately five minutes at 500°C [17].

The experimental results confirmed computational predictions regarding the temperature requirements for accessing these extreme activation barriers. The study observed the formation of equilibrium mixtures of isomers when the high energy barrier was overcome, with the second isomer detectable by standard physicochemical分æžæ–¹æ³•, validating the theoretical framework [17].

Comparative Analysis of Substrate Scope

The methodology demonstrated versatility across a range of pyrazole substrates with varying substituents:

- Aryl-substituted pyrazoles: Lower activation barriers (∼55 kcal molâ»Â¹) with successful isomerization at lower temperatures

- Alkyl/fluoroalkyl substrates: Higher activation barriers (up to 68.3 kcal molâ»Â¹) requiring the most extreme temperatures (500°C) for observable conversion

This substrate-dependent behavior highlights the importance of computational guidance in predicting the required conditions for specific transformations and underscores the need for temperature gradients in exploring diverse molecular systems [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Temperature Capillary Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in HTCS |

|---|---|---|

| Duran Glass Capillaries | 8 cm length, small-bore diameter, high thermal shock resistance | Withstands high internal pressure (up to 35 atm) at extreme temperatures |

| p-Xylene Solvent | Anhydrous, high-purity | High-booint solvent (138°C) that can approach supercritical state under reaction conditions |

| High-Temperature Furnace | Capable of 500°C with precise temperature control | Provides consistent extreme thermal energy input |

| N-Substituted Pyrazole Compounds | Varied substituents (aryl, alkyl, fluoroalkyl) | Model substrates for studying high-barrier isomerization |

| Sealing Apparatus | Standard glass-sealing torch | Creates pressure-tight enclosure for reaction mixture |

| CB-5339 | FAK Inhibitor: 1-[4-(Benzylamino)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydropyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidin-2-yl]-2-methylindole-4-carboxamide | High-purity 1-[4-(Benzylamino)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydropyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidin-2-yl]-2-methylindole-4-carboxamide, a potent FAK inhibitor for cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| JQAD1 | JQAD1, MF:C48H52F4N6O9, MW:933.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications and Future Perspectives

This demonstration of accessing extreme kinetic barriers has profound implications for synthetic chemistry. The ability to overcome 50–70 kcal molâ»Â¹ barriers significantly expands the accessible chemical space for synthetic chemists, enabling exploration of previously "forbidden" transformations [17]. This methodology complements other emerging technologies in chemical biology, including biocatalysis, biomimetic reactions, and bioorthogonal chemistry, which face their own challenges in manipulating biological systems [18].

The convergence of high-temperature methodologies with artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches presents particularly promising future directions. Recent advances in AI-driven property prediction and reaction outcome forecasting could synergize with experimental high-temperature approaches to accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel transformations [19].

The HTCS methodology establishes a foundation for further innovations in organic synthesis, potentially enabling access to diverse compounds relevant to pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and materials science that were previously considered synthetically inaccessible due to kinetic constraints [17].

The Impact of Solvent and Molecular Structure on Kinetic Barrier Heights

Kinetic barriers represent the energetic thresholds that dictate the rates and feasibility of chemical reactions. In organic synthesis, particularly in solution-phase environments common to pharmaceutical and materials science applications, these barriers are not intrinsic molecular properties but are profoundly shaped by external factors. This whitepaper examines how solvent environment and molecular structure collectively influence kinetic barrier heights, drawing upon recent experimental and computational studies. We demonstrate that strategic manipulation of these factors enables synthetic chemists to access previously prohibitive reaction pathways, control product selectivity, and develop more efficient synthetic methodologies. The insights presented herein establish a foundation for rational reaction design within a broader thesis on exploring kinetic barriers in organic synthesis research.

In the realm of organic synthesis, the height of kinetic barriers often determines the success or failure of a desired transformation. These activation energies control reaction rates, dictate product distributions, and ultimately define the boundaries of accessible chemical space. For decades, synthetic strategies have focused primarily on modifying thermodynamic parameters to drive reactions to completion. However, contemporary research has revealed that deliberate manipulation of kinetic barriers through solvent selection and molecular design offers a more powerful and versatile approach to overcoming synthetic challenges.

This technical guide examines the interconnected roles of solvent effects and molecular structure in modulating kinetic barrier heights. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these relationships is crucial for developing robust synthetic routes to complex molecules. We present quantitative data on barrier modulation, detailed experimental protocols for studying these effects, and conceptual frameworks that empower chemists to strategically lower kinetic barriers in synthetic applications, thereby enabling transformations previously considered inaccessible under conventional conditions.

Solvent Effects on Kinetic Barriers

The solvent environment profoundly influences kinetic barriers through both bulk dielectric properties and specific solute-solvent interactions. These effects can alter activation energies by tens of kcal/mol, effectively determining whether a reaction proceeds at synthetically useful rates under given conditions.

Quantitative Impact of Solvent Environment

Table 1: Solvent Effects on Kinetic Barriers in Various Organic Reactions

| Reaction Type | Gas Phase Barrier (kcal/mol) | Solution Phase Barrier (kcal/mol) | Barrier Reduction | Key Solvent Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keto-enol tautomerization (acetaldehyde) | ~70 [20] | ~23 [20] | ~47 kcal/mol | Explicit H-bond participation |

| N-vinylpyrrolidone synthesis | N/A | Varies with solvent | ~7 kcal/mol (DMSO vs. NMP) [21] | Cation solvation |

| Pyrazole isomerization | N/A | 50-70 [22] | Accessible via high-temp methods | Thermal energy compensation |

Mechanisms of Solvent Influence

Solvents impact kinetic barriers through several distinct mechanisms:

Dielectric Screening: Polar solvents stabilize charged transition states through dielectric screening, effectively lowering activation barriers for reactions involving charge separation or development [21]. Continuum solvent models capture this effect reasonably well for reactions where electronic redistribution is the primary barrier component.

Specific Molecular Interactions: For reactions involving proton transfer, such as keto-enol tautomerization, explicit solvent molecules participate directly in the reaction mechanism. In the case of acetaldehyde enolization, two water molecules create a hydrogen-bonded bridge that facilitates proton transfer, lowering the barrier from approximately 70 kcal/mol in the gas phase to about 23 kcal/mol in aqueous solution – a reduction of ~47 kcal/mol [20]. Continuous solvent models alone fail to capture this dramatic barrier reduction, highlighting the necessity of explicit solvent modeling for such processes.

Solvation Differential: The relative solvation of reactants, transition states, and products determines the net barrier height. In nucleophilic substitutions, protic solvents strongly solvate anionic nucleophiles, increasing the activation barrier, while dipolar aprotic solvents (e.g., DMSO) poorly solvate anions, resulting in significant rate acceleration [21]. This differential solvation explains the dramatic solvent effects observed in SN2 and SNAr reactions.

Molecular Structure and Kinetic Barriers

Molecular architecture fundamentally determines the intrinsic kinetic barriers of chemical transformations through electronic and steric effects that stabilize or destabilize transition states.

Electronic Effects

The electronic character of substituents directly influences reaction barriers by modifying electron density at reaction centers:

In the keto-enol tautomerization of substituted carbonyl compounds, σ-electron-withdrawing substituents significantly increase the reaction energy and consequently affect the activation barrier [20]. Electronic effects manifest through changes in bond strengths, charge distribution, and orbital energies in the transition state.

For the isomerization of N-substituted pyrazoles, the nature of the substituent dictates barrier heights ranging from 50-70 kcal/mol, requiring specialized high-temperature techniques to overcome [22].

Steric and Conformational Factors

Spatial arrangement of atoms in molecules creates steric effects that can dramatically impact barrier heights:

In molecular self-assembly on surfaces, the initial deposition state (e.g., dimers vs. monomers) determines the kinetic accessibility of different network structures [23]. This kinetic trapping phenomenon demonstrates how molecular organization can create effective barriers to thermodynamic minima.

Conformational flexibility influences the ability of molecules to achieve transition state geometries, with rigid structures often exhibiting higher barriers due to increased strain energy.

Table 2: Structural Factors Influencing Kinetic Barriers

| Structural Factor | Effect on Barrier | Molecular Example | Impact Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron-withdrawing substituents | Increases/enolization reaction energy | Substituted carbonyl compounds [20] | Significant ΔE†variation |

| Hydrogen-bonding capacity | Lowers/proton transfer barriers | DHBA dimers on calcite [23] | Enables ordered assembly |

| Molecular conformation | Controls/transition state accessibility | N-substituted pyrazoles [22] | 50-70 kcal/mol range |

| Pre-association tendency | Determines/assembly pathway kinetics | DHBA dimer deposition [23] | Kinetic trapping |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Elucidating kinetic barriers and their modulation requires integrated experimental and computational approaches that provide complementary insights into reaction energetics.

Experimental Kinetic Analysis

High-Temperature Kinetic Studies for High-Barrier Reactions [22]

- Objective: Access transformations with activation barriers of 50-70 kcal/mol, previously considered inaccessible in solution.

- Reaction System: Isomerization of N-substituted pyrazoles in high-temperature solution phase.

- Apparatus: Sealed glass capillaries (standard borosilicate) serving as microreactors.

- Solvent: p-Xylene selected for thermal stability and appropriate polarity.

- Temperature Protocol: Reactions conducted at temperatures up to 500°C for short durations (as brief as 5 minutes).

- Analysis: Product quantification via GC-MS/NMR to determine yields; kinetic profiling through time-series experiments at varying temperatures.

- Key Finding: Achievement of up to 50% product yield for reactions with barriers of 50-70 kcal/mol, demonstrating the feasibility of high-barrier transformations under controlled conditions.

Solvent Effect Quantification in N-Vinylpyrrolidone Synthesis [21]

- Objective: Determine solvent impact on reaction rate and activation barrier for nucleophilic addition to acetylene.

- Catalytic System: KOH (0.8 g) dissolved in 2-pyrrolidone (33.3 g) with solvent (100 mL).

- Reactor System: Continuous high-pressure liquid-phase apparatus with Stop-Flow Micro-Tubing (SFMT) reactors for inherent safety with acetylene.

- Solvent Screening: Polar aprotic solvents including DMSO, DMF, NMP, and DMAc.

- Kinetic Measurement: Reaction monitoring at 150°C with time-sampled analysis.

- Computational Correlation: DFT calculations with microsolvation models to interpret solvent effects.

- Key Finding: DMSO identified as optimal solvent, providing 80% NVP yield within 4 minutes at 150°C, with computed barriers consistent with experimental rate enhancements.

Computational Approaches

First-Principles Kinetic Modeling [20] [23]

- Electronic Structure Method: Density Functional Theory (DFT) with hybrid functionals (e.g., B3LYP) and polarized, diffused basis sets (e.g., 6-311++g(3df,3pd)).

- Solvent Modeling:

- Implicit Models: Polarizable continuum models (PCM) for bulk dielectric effects.

- Explicit Models: Microsolvation with discrete solvent molecules (1-2 water molecules for proton transfer reactions [20]).

- Transition State Optimization: Standard eigenvector following methods with frequency verification (exactly one imaginary frequency).

- Free Energy Corrections: Inclusion of thermal and entropic contributions for finite-temperature predictions.

- Energy Decomposition Analysis: Partitioning of interaction energies to identify dominant factors.

Diagram 1: Integrated Methodologies for Kinetic Barrier Analysis showing complementary experimental and computational approaches for determining kinetic parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Kinetic Barrier Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Kinetic Studies | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dipolar Aprotic Solvents (DMSO, DMF, DMAc) | Reduce barriers for nucleophilic substitutions by weak anion solvation | N-vinylpyrrolidone synthesis [21] |

| High-Temperature Solvents (p-xylene) | Thermally stable medium for high-barrier reactions | Pyrazole isomerization at 500°C [22] |

| Glass Capillary Microreactors | Enable safe high-temperature/pressure reaction screening | High-temperature organic synthesis [22] |

| Stop-Flow Micro-Tubing Reactors | Safe handling of acetylene at elevated pressures | Continuous N-vinylpyrrolidone synthesis [21] |

| Strong Base Catalysts (KOH) | Generate nucleophilic species through deprotonation | Pyrrolidone anion formation for vinylation [21] |

| Explicit Solvent Models (Quantum Clusters) | Accurate modeling of specific solute-solvent interactions | Keto-enol tautomerization with water bridges [20] |

| AXKO-0046 | AXKO-0046, MF:C25H33N3, MW:375.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MYF-03-176 | 2-fluoro-1-[(3R,4R)-3-(pyrimidin-2-ylamino)-4-[[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]methoxy]pyrrolidin-1-yl]prop-2-en-1-one | High-purity 2-fluoro-1-[(3R,4R)-3-(pyrimidin-2-ylamino)-4-[[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]methoxy]pyrrolidin-1-yl]prop-2-en-1-one for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

Kinetic Control in Synthesis Design

The manipulation of kinetic barriers enables synthetic chemists to exert control over reaction pathways and access metastable products that are thermodynamically disfavored but functionally valuable.

Kinetic Trapping and Pathway Control

Molecular assembly on surfaces provides a compelling illustration of kinetic control, where the initial deposition state determines the structural evolution pathway [23]. For dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA) on calcite, deposition as dimers rather than monomers leads to a sequence of structural transitions from clusters to striped networks to dense networks, despite monomers being thermodynamically more stable. This pathway is entirely controlled by kinetics rather than thermodynamics, as the transition from dimers to monomers presents a significant kinetic barrier.

Strategic Access to High-Barrier Transformations

Traditional solution-phase synthesis typically faces an effective upper limit of approximately 35-40 kcal/mol for feasible transformations under standard conditions. However, recent methodological advances demonstrate that barriers of 50-70 kcal/mol can be overcome through high-temperature techniques in sealed systems [22]. This expansion of accessible barrier space enables synthetic routes previously considered impossible, opening new frontiers for molecular complexity generation.

Diagram 2: Kinetic versus Thermodynamic Control Pathways showing how solvent and molecular design strategies can selectively modulate specific barrier heights to control reaction outcomes.

The strategic manipulation of kinetic barriers through solvent selection and molecular design represents a powerful paradigm in modern organic synthesis. This whitepaper has demonstrated that solvent effects can modulate barriers by up to 47 kcal/mol through specific molecular interactions, while molecular structure dictates intrinsic reactivity patterns. The integrated experimental and computational methodologies presented herein provide researchers with robust tools for quantifying and predicting these effects. For drug development professionals and synthetic chemists, these insights enable rational design of synthetic routes to access challenging transformations, control selectivity, and develop more efficient manufacturing processes. As the field advances, the deliberate engineering of kinetic barriers will continue to expand the accessible chemical space, enabling the synthesis of increasingly complex molecules with precision and efficiency.

Advanced Methodologies for Studying and Applying Kinetic Principles

The accurate prediction of kinetic barriers represents a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry, directly impacting progress in organic synthesis, materials science, and drug discovery. Traditional experimental approaches to measuring activation energies are often time-consuming and resource-intensive, creating a significant bottleneck in research and development pipelines. High-throughput computational analysis has emerged as a powerful alternative, enabling the rapid screening of reaction energy landscapes across vast chemical spaces. Among quantum mechanical methods, Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) have proven particularly valuable for this application, offering complementary balances between computational accuracy and efficiency.

DFT stands as the most widely used quantum mechanical method for studying molecular structures and reaction mechanisms, with the B3LYP functional finding extensive application across nearly all domains of chemistry [24] [25]. Meanwhile, DFTB—a semi-empirical method derived from DFT—provides a computationally efficient alternative that is approximately two to three orders of magnitude faster than standard DFT methods, making it particularly attractive for applications to large molecules and condensed phase systems where extensive sampling of configurational space is required [26]. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, methodological frameworks, and practical implementations of these computational approaches specifically for high-throughput kinetic barrier analysis in organic synthesis research.

Theoretical Foundations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Fundamentals

DFT bypasses the complexity of the many-electron wave function by using the electron density as the fundamental variable, significantly reducing computational cost while preserving accuracy [25]. The energy in DFT is expressed as:

[ E{\text{DFT}} = T(Ï) + E{ne}(Ï) + J(Ï) + E_{xc}(Ï) ]

Where (T(Ï)) represents the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, (E{ne}(Ï)) is the nucleus-electron attraction energy, (J(Ï)) is the Coulomb electron-electron repulsion energy, and (E{xc}(Ï)) encompasses the exchange and correlation effects [25]. The widely used B3LYP functional (Becke, 3-parameter, Lee-Yang-Parr) combines exact Hartree-Fock exchange with local and semi-local exchange and correlation terms based on the adiabatic connection [24]:

[ E{xc}^{\text{B3LYP}} = (1-a0)Ex^{\text{LSDA}} + a0Ex^{\text{HF}} + axΔEx^{\text{B88}} + acEc^{\text{LYP}} + (1-ac)E_c^{\text{VWN}} ]

Here, (Ex^{\text{LSDA}}) and (Ec^{\text{VWN}}) are the standard local exchange and correlation functionals, while (ΔEx^{\text{B88}}) and (Ec^{\text{LYP}}) are gradient corrections [24]. The empirical parameters (a0), (ax), and (a_c) were historically set to 0.20, 0.72, and 0.81 without optimization, yet surprisingly yielded reasonable performance for many chemical systems.

Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) Fundamentals

DFTB represents a simplified approximation to DFT that significantly reduces computational cost through several key approximations: the use of minimal basis sets, the neglect of three-center integrals, and the parameterization of Hamiltonian matrix elements [26]. The method exists in progressively refined forms:

- DFTB1: The non-self-consistent version with a first-order approximation

- DFTB2: Includes self-consistent charge corrections (originally called SCC-DFTB)

- DFTB3: Extends to third-order expansion and improved parameterization [26]

This methodological evolution has substantially improved the accuracy of DFTB for describing diverse chemical systems, particularly organic molecules and biomolecular systems, while maintaining its significant computational advantages over full DFT methods.

Comparative Performance for Kinetic Barriers

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DFT and DFTB Methods for Kinetic Barriers

| Method | Computational Speed | Typical Barrier Height MAE* | System Size Limit | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 1x (reference) | 2-5 kcal/mol | ~100 atoms | Organic thermochemistry, reaction mechanisms |

| revB3LYP | 1x | 1-3 kcal/mol | ~100 atoms | Improved thermochemistry for large molecules |

| DFTB3/3OB | 100-1000x | 3-7 kcal/mol | 1000+ atoms | Large (bio)molecules, configurational sampling |

| DFTB2 | 100-1000x | 5-10 kcal/mol | 1000+ atoms | Preliminary screening, large systems |

*MAE: Mean Absolute Error relative to high-level reference methods or experimental data [24] [26]

The performance of standard B3LYP for kinetic barriers shows systematic limitations, particularly for larger organic molecules where errors can become substantial [24]. Recent work has demonstrated that reoptimized parameter sets (e.g., aâ‚€=0.20, aâ‚“=0.67, ac=0.84) can significantly improve performance, reducing systematic errors for large molecules by a factor of five while correcting qualitative failures in reaction mechanism prediction [24]. For DFTB, the most recent third-order version (DFTB3/3OB) with dispersion correction provides satisfactory description of organic chemical reactions with accuracy approaching popular DFT methods with large basis sets, though larger errors may occur in certain cases [26].

Methodological Framework

Workflow for High-Throughput Barrier Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for high-throughput kinetic barrier analysis using DFT and DFTB methods:

High-Throughput Kinetic Analysis Workflow

Experimental Protocol for Barrier Calculations

System Preparation and Conformational Analysis

Molecular Input Generation: Begin with SMILES strings or 2D structural representations for all reactants, products, and proposed transition state guesses. Convert these initial representations to 3D coordinates using tools like Open Babel or RDKit.

Conformational Sampling: Employ systematic search procedures or molecular dynamics simulations to identify all low-energy conformers for each molecular species. The number of minima increases with rotatable bonds, making comprehensive sampling computationally challenging but essential for accurate results [25].

Initial Geometry Optimization: Perform preliminary geometry optimization on all identified conformers using a fast method (MMFF94, PM7, or DFTB) to identify the lowest-energy conformation for subsequent transition state searches.

Transition State Optimization Protocol

Transition State Guess Generation: Generate initial transition state guesses through:

- Constrained optimization along suspected reaction coordinate

- interpolation between reactant and product structures (e.g., using the Synchronous Transit method)

- Structural analogy to known transition states from similar reactions

Transition State Optimization: Employ specialized optimization algorithms (e.g., Berny algorithm, eigenvector-following methods) to locate first-order saddle points on the potential energy surface. Key considerations include:

- Using appropriate integration grids and convergence criteria

- Applying tight optimization criteria for maximum forces and displacements

- Utilizing frequency analysis to verify the presence of exactly one imaginary frequency

Reaction Path Verification: Perform Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculations to confirm the transition state correctly connects to the intended reactants and products. This critical validation step ensures the stationary point represents the desired chemical transformation rather than a spurious saddle point.

Energy Calculation and Corrections

Frequency Calculations: Perform vibrational frequency analysis on all optimized stationary points to:

- Verify minima (no imaginary frequencies) and transition states (exactly one imaginary frequency)

- Compute zero-point vibrational energy (ZPVE) corrections

- Calculate thermal corrections to enthalpies and free energies at the target temperature

Solvent Effects: Incorporate solvent effects using implicit solvation models such as:

- Polarized Continuum Model (PCM) for general solvents

- Conductor-like PCM (C-PCM) for improved performance with polar solvents

- Solvent model density (SMD) for more accurate treatment of specific solvation effects [25]

Single-Point Energy Refinement: For highest accuracy, perform single-point energy calculations on DFTB-optimized structures using higher-level DFT methods with larger basis sets [26] [27]. This hybrid approach combines the structural sampling efficiency of DFTB with the improved energetics of more sophisticated functionals.

High-Throughput Implementation

Automation and Workflow Management

Implement automated workflow systems to manage the computational pipeline from molecular input to final barrier analysis. Key components include:

- Job Management: Automated job submission, monitoring, and recovery for failed calculations

- Error Handling: Protocols for identifying and addressing common convergence failures

- Data Extraction: Automated parsing of output files to extract geometries, energies, and vibrational frequencies

- Quality Control: Automated validation checks for imaginary frequency counts, IRC connectivity, and convergence criteria

TChem Software Toolkit

The TChem open-source software provides specialized functionality for high-throughput kinetic analysis [28]:

- Parallel Execution: Evaluation of multiple samples in parallel using Kokkos for performance portability

- Canonical Reactor Models: Implementation of constant-pressure batch reactors, constant-volume reactors, plug-flow reactors, and transient continuously stirred tank reactors

- Jacobian Evaluation: Automatic evaluation of source term's Jacobian matrix using finite difference or automatic differentiation

- Mechanism Analysis: Support for complex kinetic models involving both gas-phase and surface reactions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for High-Throughput Kinetic Analysis

| Tool Name | Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| TChem | Kinetic modeling and analysis | Reaction rate calculations, reactor modeling [28] |

| ADF | DFT/DFTB calculations | Geometry optimization, transition state search [26] |

| PCM Implicit Solvation | Solvent effect modeling | Energy corrections for solution-phase reactions [25] |

| IRC Path Following | Reaction path verification | Transition state validation [25] |

| Kokkos Parallel Programming | Performance portability | High-throughput sample evaluation [28] |

| DN02 | DN02, MF:C22H24FN3O3, MW:397.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ZZL-7 | ZZL-7, MF:C11H20N2O4, MW:244.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Organic Synthesis and Materials Science

Ring-Closing Depolymerization of Polycarbonates

Recent applications of high-throughput kinetic barrier analysis include the investigation of ring-closing depolymerization (RCD) for chemical recycling of polymeric materials [27]. In this context, DFTB has been employed to screen energy barriers for RCD of 6-membered aliphatic carbonates in different solvent environments. The methodology enabled computational investigation of a problem that would be "completely intractable to realize experimentally at scale" [27].

Key findings from this application include:

- Absolute Barriers: Unanalyzed RCD barriers average approximately 50 kcal/mol for uncatalyzed ring closure to re-form cyclic carbonates

- Solvent Effects: Acetonitrile universally lowers relative enthalpic barriers by over 2 kcal/mol compared to toluene or tetrahydrofuran

- Substituent Effects: Bulkier substituents generally correlate with decreased barrier heights in non-polar solvents

- Method Validation: DFT-computed barriers trend similarly but are up to 10 kcal/mol higher than corresponding DFTB values [27]

This application demonstrates how high-throughput barrier computations can provide meaningful insight into broad reactivity trends that would be highly laborious to access experimentally, particularly for systems where historical data is minimal.

1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions

DFT calculations have been extensively applied to elucidate mechanisms and stereoselectivity in 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions, particularly using the B3LYP functional [25]. These reactions represent important transformations in heterocyclic synthesis, allowing introduction of multiple stereogenic centers in a stereospecific manner. Key mechanistic insights enabled by computational analysis include:

- Concerted vs. Stepwise Mechanisms: Evaluation of synchronous or asynchronous bond formation in concerted mechanisms

- Frontier Molecular Orbital Analysis: Rationalization of regioselectivity through HOMO-LUMO interactions

- Activation Strain Model: Application of the Houk/Bickelhaupt model to understand activation barriers through distortion and interaction energies

- Metal Catalysis Effects: Understanding how metal ions alter orbital coefficients and energies to influence stereoselectivity [25]

The computational analysis of these reactions provides critical support for experimental observations and enables predictive design of new synthetic methodologies.

Validation and Performance Assessment

Benchmarking Against Experimental and High-Level Theoretical Data

Compressive validation against reliable reference data is essential for establishing the credibility of computational methods for kinetic barrier prediction. Established benchmarking approaches include:

- Database Comparison: Evaluation against curated databases of experimental kinetic data and high-level ab initio reference values (e.g., NHTBH38/08 for barrier heights, ISO34 for isomerization energies) [26]

- Statistical Error Analysis: Calculation of mean signed error (MSE), mean absolute error (MAE), root-mean-square error (RMSE), and largest error (LE) metrics [26]

- Chemical Subset Analysis: Assessment of performance across different reaction classes and functional group transformations

For DFTB methods, recent benchmarking demonstrates that the DFTB3/3OB model with dispersion correction "provides satisfactory description of organic chemical reactions with accuracy almost comparable to popular DFT methods with large basis sets" [26]. This represents a significant improvement over earlier DFTB parameterizations and justifies its application to large-scale screening projects where computational efficiency is paramount.

Experimental Correlations

Computational predictions of kinetic barriers must ultimately be validated against experimental observations. Successful applications include:

- Polymer Depolymerization: Correlation of computed barriers with experimental trends in ring-closing depolymerization yields [27]

- Solvent Effects: Reproduction of experimental solvent trends in Tc values for depolymerization reactions [27]

- Reaction Mechanism Elucidation: Resolution of contradictory mechanistic proposals through comparison of computed and experimental selectivity data [24] [25]

These validation studies provide confidence in the application of computational methods to predict kinetic barriers for novel chemical systems where experimental data may be limited or unavailable.

High-throughput kinetic barrier analysis using DFT and DFTB methods has matured into an indispensable tool for accelerating research in organic synthesis, materials science, and drug discovery. The complementary strengths of these methods—with DFT providing higher accuracy for detailed mechanistic studies and DFTB enabling rapid screening across vast chemical spaces—create a powerful framework for computational reaction exploration.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas:

- Integration with Machine Learning: Combining physical models with data-driven approaches to further accelerate screening and improve accuracy

- Automated Mechanism Elucidation: Development of algorithms that can automatically propose and test potential reaction pathways without human intervention

- Advanced Solvation Models: Incorporation of explicit solvent molecules and dynamic solvent effects for more realistic treatment of solution-phase reactions

- High-Performance Computing: Leveraging emerging computing architectures to enable even larger-scale screening campaigns

As these computational methodologies continue to evolve and integrate with experimental research programs, they hold the potential to fundamentally transform how we discover and optimize chemical transformations, ultimately accelerating the development of new materials, therapeutics, and sustainable chemical processes.

The Kinetic Decoupling-Recoupling (KDRC) strategy represents a transformative approach for overcoming kinetic entanglement in complex reaction networks. This framework enables unprecedented selectivity in challenging chemical transformations, as demonstrated by its recent application in achieving up to 79% yield of ethylene and propylene from polyethylene waste—a significant advancement over conventional methods that typically yield less than 25% of these target products. By strategically separating previously entangled reaction pathways and independently optimizing their kinetics before reintegrating them under precise conditions, KDRC effectively manipulates reaction coordinates to favor desired products while suppressing by-product formation. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, experimental implementation, and broader implications of KDRC for overcoming kinetic barriers in organic synthesis and sustainable chemical manufacturing.

Kinetic entanglement presents a fundamental challenge in complex chemical reaction systems, particularly in polymer depolymerization and multi-pathway organic syntheses. This phenomenon occurs when competing reactions share identical catalytic sites, similar activation energy barriers, or overlapping operational conditions, creating an intrinsically linked network where desired and undesired pathways proceed simultaneously. In such systems, the formation of target products becomes inherently coupled with the generation of by-products, imposing severe limitations on maximum achievable yields and selectivity.

In conventional polyethylene cracking, for instance, this kinetic entanglement restricts ethylene and propylene yields to approximately 23%, with the remaining products consisting of various alkanes, aromatics, and heavier olefins that arise from parallel and consecutive reactions including hydrogen transfer, oligomerization, and aromatization [29]. Similar challenges manifest across organic synthesis, where competing reaction pathways often share common intermediates or catalytic sites, creating yield ceilings that traditional optimization approaches cannot overcome through conventional parameter tuning alone.

The KDRC framework addresses this fundamental limitation through a paradigm shift from concurrent optimization to sequential decoupling and controlled recoupling of reaction steps, enabling previously inaccessible regions of the kinetic landscape.

Core Principles of KDRC

The KDRC strategy operates on three foundational principles that collectively enable escape from kinetic entanglement:

Reaction Pathway Decoupling

The initial decoupling phase separates previously entangled reaction sequences into discrete stages with independently optimized conditions. This physical and temporal separation prevents direct interference between stages, allowing each transformation to occur under its ideal kinetic regime without compromising subsequent steps. In practice, this involves configuring reactor systems that maintain distinct environmental conditions (temperature, pressure, catalyst composition) for each stage while managing intermediate transfer between stages.

Kinetic Sweet Spot Identification

Each decoupled stage operates within a precisely defined "kinetic sweet spot" where the rate of target product formation significantly exceeds that of competing pathways. These operational windows are identified through comprehensive kinetic analysis that quantifies rate constants and reaction orders for all significant pathways. For instance, in polyethylene conversion, the critical sweet spots were identified as:

- KSS I: Intermediate (Câ‚„/Câ‚… olefins) concentration maintained between 0.004-0.008 molCHâ‚‚ gâ»Â¹

- KSS II: Temperature >500°C to ensure dimerization-β-scission dominates over reverse reactions [29]

Controlled Pathway Recoupling

The final principle involves strategically reintegrating the decoupled pathways through synchronized transfer of intermediates between stages. This recoupling is designed to align the output of one stage with the optimal input conditions for the subsequent stage, creating a continuous flow where intermediates generated in the first stage immediately encounter ideal transformation conditions in the second stage without undergoing deleterious side reactions.

Experimental Implementation

Reactor Configuration and Catalysts

The KDRC strategy requires specialized reactor systems capable of maintaining independent control over multiple reaction zones. For polyethylene conversion, this was achieved using a tandem fixed-bed reactor system with the following configuration:

Stage I (Low-Temperature Cracking)

- Temperature: Programmed from 260°C to 300°C

- Catalyst: Layered self-pillared zeolite (LSP-Z100) with MFI/MEL intergrowth structure

- Key Properties: High external surface area (124 m²/g), mesoporous network, strong Lewis acid sites from tri-coordinated aluminum

- Function: Selective cracking of polyethylene to Câ‚„/Câ‚… olefin intermediates

- Reactor Atmosphere: Nitrogen flow (10 sccm) to reduce catalyst contact time

Stage II (High-Temperature Conversion)

- Temperature: 540°C

- Catalyst: Phosphorus-modified HZSM-5 (P-HZSM-5) with moderated acidity

- Key Properties: Microporous framework, reduced acid site density from phosphorus modification