Overcoming Data Scarcity in Generative AI for Materials Science: Strategies for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

This article addresses the critical challenge of data scarcity that constrains the development of robust generative AI models in materials science and drug discovery.

Overcoming Data Scarcity in Generative AI for Materials Science: Strategies for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of data scarcity that constrains the development of robust generative AI models in materials science and drug discovery. It provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the roots of the data scarcity problem, detailing current methodological solutions like transfer learning and federated learning, offering strategies for troubleshooting model performance, and establishing frameworks for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of different approaches. The synthesis of these intents provides a actionable roadmap for leveraging generative AI to accelerate the design of novel therapeutics and materials, even in data-limited environments.

The Data Scarcity Challenge: Why Generative AI for Materials and Drugs Hits a Wall

FAQs on Data Scarcity in Materials AI

What exactly is meant by "data scarcity" in the context of generative AI for materials science? Data scarcity is a multi-faceted challenge. It refers not only to a simple lack of data volume but also to critical issues with data quality, diversity, and accessibility that can limit the performance of AI models. In materials science, this often manifests as a lack of data for novel material classes, outdated information, inaccessible data locked in silos, or datasets that are incomplete or inconsistent [1] [2] [3].

Why are generative AI models particularly susceptible to problems caused by poor data quality? Generative AI models learn patterns and relationships directly from their training data. If this data is flawed, the models will produce flawed outputs. Key issues include:

- Inaccurate Outputs: Models trained on incomplete or outdated data can produce misleading results [2].

- AI Hallucinations: Models might generate materials that appear valid but are physically implausible or incorrect upon verification [3].

- Bias and Reduced Reliability: Skewed or non-diverse datasets can lead models to reinforce existing biases and produce inconsistent or unfair results [2].

How can we generate reliable training data when real-world experimental data is limited? Synthetic data generation is a key strategy to overcome data volume limitations. Techniques like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Diffusion Models can create artificial, statistically realistic datasets [4] [5]. This is especially useful for simulating rare events or generating data for hypothetical material structures that have not yet been synthesized, thus augmenting scarce real-world data [4].

What role does data "context" play in mitigating data scarcity for scientific AI? Providing rich context is crucial for accurate AI inference. When an AI model processes data, a scarcity of proper context can lead to misinterpretations [3]. Techniques like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) integrated with knowledge graphs can provide models with necessary background information and relationships from scientific literature, grounding their generations in established knowledge [6] [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Generative AI Model Producing Physically Implausible Materials

This is a common issue where the AI "hallucinates" and generates material structures that are unstable or violate known physical laws.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check Training Data: Audit the dataset for coverage. Does it adequately represent the target material domain and properties? [2]

- Verify Data Quality: Profile the data for inconsistencies, missing values, or inaccuracies that the model may have learned [3].

- Assess Physics Integration: Determine if the model is purely data-driven or incorporates physical constraints.

Solutions:

- Integrate Physical Constraints: Use a Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) that encodes governing equations, thermodynamic constraints, and microstructural symmetries directly into the model. This ensures predictions are physically consistent, even in data-scarce regimes [6].

- Apply Structural Constraints: For crystal structure generation, use a tool like SCIGEN to enforce specific geometric design rules (e.g., Kagome or Lieb lattices) at each step of the generation process, steering the AI toward structurally valid quantum materials [8].

- Implement Automated Reasoning: Use validation tools that employ formal logic to check the accuracy of AI-generated structures against established scientific facts, helping to constrain uncertain outputs [7].

Problem: AI Model Performance is Poor Due to Small or Siloed Datasets

When data is insufficient, inaccessible, or locked in legacy systems, model performance plateaus.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Identify Data Silos: Map data sources across departments or legacy systems that are not integrated [2].

- Evaluate Data Architecture: Determine if the current data infrastructure can handle diverse, multimodal data required for generative AI [7].

- Profile Data Volume: Quantify the available data for the specific material property or class of interest.

Solutions:

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Start with a base model pre-trained on a large, general materials database (e.g., MatterGen, trained on 608,000 stable materials), then fine-tune it on your smaller, domain-specific dataset [9].

- Build a Unified Data Architecture: Adopt modern data infrastructure like vector databases and semantic frameworks (e.g., knowledge graphs) to manage diverse data types and break down silos, creating a comprehensive dataset for AI training [7] [2].

- Augment with Synthetic Data: Use generative models to create synthetic data that mimics the statistical properties of real materials data, addressing volume and diversity gaps while preserving privacy [4] [5].

Experimental Protocols for Data-Scarce Research

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning a Generative Foundation Model for Targeted Property Generation

This protocol uses models like MatterGen, a diffusion model for 3D material structures, to discover materials with specific properties without requiring massive private datasets [9].

Methodology:

- Base Model Selection: Start with a pre-trained foundation model (e.g., MatterGen) that has learned general material representations from a large public database [9].

- Prepare Fine-Tuning Dataset: Curate a smaller, labeled dataset with the desired property constraints (e.g., bulk modulus > 200 GPa). Data quality is critical; perform data cleaning and validation [3].

- Model Fine-Tuning: Re-train (fine-tune) the base model on the targeted dataset. This process adjusts the model's parameters to specialize in generating materials that meet the specified conditions.

- Generation and Screening: Use the fine-tuned model to generate novel candidate materials. Screen these candidates for stability.

- Validation: Run detailed simulations (e.g., using an AI emulator like MatterSim) and proceed to experimental synthesis for validation, as demonstrated with the novel material TaCr2O6 [9].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Physics-Informed Generative Model

This methodology integrates physical laws directly into the AI model to guide learning where data is scarce [6].

Methodology:

- Problem Formulation: Define the physical governing equations (e.g., for energy transport, mechanical deformation) and constraints relevant to the material system.

- Model Architecture: Design a neural network that incorporates these equations as part of its loss function—this is the core of a Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) [6].

- Training: Train the network on the available (scarce) experimental or simulation data. The model is penalized not only for deviations from the data but also for violating the physical laws.

- Coupling with Generative AI: Use the PINN as a predictor or critic for a generative model (e.g., a VAE or GAN). The generator is conditioned to produce structures that the PINN evaluates as physically plausible.

- Active Learning Loop: Use Bayesian optimization to identify the most informative data points for future experiments, closing the loop between AI prediction and physical validation in a sample-efficient manner [6].

Data and Technique Summaries

Table 1: Comparison of Constraint Integration Methods in Generative AI

| Method / Tool | Core Principle | Application Context | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCIGEN [8] | Applies user-defined geometric structural rules at each generation step. | Generating materials with specific lattice structures (e.g., Archimedean lattices). | Directly steers generation toward structurally exotic materials with target quantum properties. |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [6] | Encodes physical laws (PDEs, constraints) directly into the model's loss function. | Predicting material properties in data-scarce regimes where physics is well-understood. | Ensures physically consistent predictions and provides calibrated uncertainty. |

| Knowledge Graph Conditioning [6] [7] | Uses structured knowledge from scientific literature to provide context. | Conditioning both prediction and generation on established scientific facts. | Enriches learning when data are limited by integrating existing domain knowledge. |

Table 2: Data Augmentation Techniques for Materials AI

| Technique | Description | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data (GANs/VAEs) [4] [5] | AI-generated data that mimics the statistical properties of real data. | Scalably creates vast amounts of labeled data, including rare events, while preserving privacy. |

| Transfer Learning [9] | Fine-tuning a model pre-trained on a large, general dataset for a specific task. | Reduces the need for large, task-specific datasets by leveraging pre-existing knowledge. |

| Data Ontologies & Taxonomies [7] | Using a structured "language" to standardize concepts and tag data. | Improves precision in context retrieval during inference, reducing errors from context overlap. |

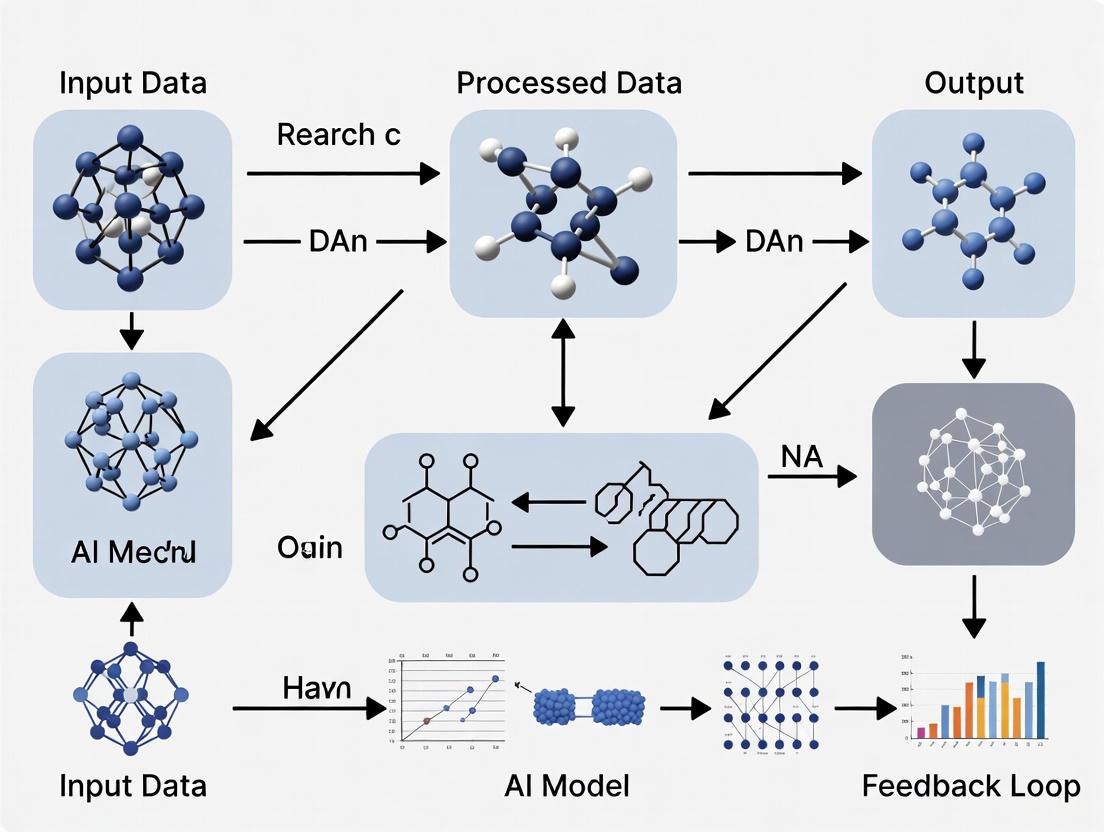

Research Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Constrained Materials Generation Workflow

Diagram 2: Data Augmentation and Integration Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Data-Scarce Materials AI Research

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| MatterGen [9] | Generative AI Model | A diffusion model for direct, property-constrained generation of novel 3D material structures. |

| SCIGEN [8] | Generative AI Tool | A method for applying strict structural constraints to steer existing generative models toward target geometries. |

| Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) [6] | AI Model Architecture | Encodes physical laws into neural networks to ensure predictions are consistent and reliable despite scarce data. |

| Knowledge Graph [6] [7] | Data Structuring Framework | Organizes scientific knowledge into a semantic network to provide contextual information for AI models. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [4] [5] | Synthetic Data Generator | Creates artificial data by pitting a generator and discriminator network against each other. |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [7] | Information Retrieval Technique | Enhances AI generation by retrieving relevant information from a knowledge base before producing an output. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Data Scarcity in Generative AI

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers and scientists grappling with data scarcity in AI-driven drug discovery and material design. The guidance is framed within the broader thesis that strategic computational methods can overcome data limitations to accelerate generative AI research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Poor Model Performance on Small Datasets

Symptoms: Your AI model has high error rates in property prediction, generates non-novel or invalid molecular structures, or fails to generalize to unseen data.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Technical Rationale | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Implement Transfer Learning (TL) | Leverage a pre-trained model from a large, source dataset (e.g., general molecular structures) and fine-tune its last few layers on your small, target dataset. [10] | Rapid model convergence and improved accuracy on the target task, even with limited data. [10] |

| 2 | Apply Data Augmentation (DA) | Systematically create modified versions of your existing data. For materials, this could be rotations of atomistic images; for molecules, use valid atomic perturbations or stereochemical variations. [10] | Effectively increases the size and diversity of your training set, reducing overfitting and improving model robustness. [10] |

| 3 | Utilize Multi-Task Learning (MTL) | Train a single model to predict several related properties simultaneously (e.g., solubility, toxicity, and binding affinity). [10] | The model learns a more generalized representation by sharing knowledge across tasks, which regularizes the model and boosts performance on each individual task. [10] |

Visual Workflow for Diagnosis:

Guide 2: Generating Non-Novel or Invalid Outputs

Symptoms: Your generative model produces molecular structures that are too similar to training data, are chemically invalid, or have poor synthetic feasibility.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Technical Rationale | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Switch to Advanced Architectures | Use a Conditional GAN (cGAN) or CycleGAN to gain finer control over generation. Condition the model on specific desired properties (e.g., high solubility) to guide the output. [11] | Generation of novel structures that adhere to target constraints and exhibit higher validity and diversity. [11] |

| 2 | Implement Robust Validation | Integrate rule-based chemical checkers (e.g., for valency) and use oracle models to predict key properties of generated candidates, filtering out poor ones. [10] | Ensures generated materials or molecules are physically plausible and have a high potential for success in downstream testing. [10] |

| 3 | Explore One-Shot Learning (OSL) | Frame the problem as learning from one or a few examples by transferring prior knowledge from a related, larger dataset. [10] | The model can learn to recognize or generate new classes of compounds from very few examples, promoting novelty. [10] |

Visual Workflow for Output Validation:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most data-efficient method for starting a new project with virtually no target data?

A: Transfer Learning (TL) is the most recommended starting point. [10] Begin with a model pre-trained on a large, public dataset (e.g., QM9 for quantum properties or ChEMBL for drug-like molecules). Then, fine-tune this model on your small, specific dataset. This approach leverages generalized knowledge from the broad domain, allowing you to achieve meaningful results with as little as hundreds of data points instead of millions.

Q2: How can we collaborate across institutions if data sharing is restricted due to privacy or IP concerns?

A: Federated Learning (FL) is designed specifically for this scenario. [10] In FL, a global model is trained by aggregating updates (like gradient information) from models trained locally on each institution's private data. The raw data itself never leaves the original institution, preserving privacy and IP, while all participants benefit from a model trained on a much larger, virtual dataset.

Q3: We have a small dataset. When should we use synthetic data generation, and what are the risks?

A: Use synthetic data generation (e.g., with GANs) when you need to augment your dataset for specific scenarios, such as simulating rare material phases or generating molecules with a desired property profile. [10] [11]

Risks and Mitigations:

- Risk: The generative model may memorize training data instead of learning the underlying distribution, leading to a lack of novelty and privacy concerns. [10]

- Mitigation: Use architectures like Wasserstein GAN (wGAN), which have been shown to be more robust and less prone to mode collapse (a form of memorization). [12]

- Risk: The quality of synthetic data is highly dependent on the size and quality of the original training data. GANs can perform poorly on very small datasets. [12]

- Mitigation: Start with a pre-trained generative model or use it in conjunction with other methods like TL.

Q4: How do we reliably benchmark our model's performance against others in the field?

A: Use open-source, community-driven benchmarking platforms like JARVIS-Leaderboard for materials informatics or MoleculeNet for drug discovery. [13] These platforms provide standardized tasks and datasets, ensuring fair and reproducible comparisons of different algorithms and methods. This helps validate your approach and identify the true state-of-the-art.

Comparative Analysis of Low-Data Handling Methods

The table below summarizes the core strategies for handling data scarcity, helping you choose the right tool for your challenge. [10]

| Method | Core Principle | Ideal Use Case | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Learning (TL) | Knowledge transfer from a large source task to a small target task. | New research area with small datasets; leveraging existing public data. | Rapid model development with minimal target data. | Risk of negative transfer if source and target domains are too dissimilar. |

| Active Learning (AL) | Iterative selection of the most informative data points for labeling. | Scenarios where data labeling (e.g., experimental testing) is expensive. | Optimizes resource allocation by reducing labeling costs. | Requires an iterative loop with experimental validation; initial model may be weak. |

| One-Shot Learning (OSL) | Learning from one or a very few examples per class. | Identifying or generating new classes of materials/molecules from few examples. | Extreme data efficiency for classification/generation tasks. | High dependency on the quality and representativeness of the single example. |

| Multi-Task Learning (MTL) | Jointly learning multiple related tasks in a single model. | Predicting several physicochemical or biological properties simultaneously. | Improved generalization and data efficiency via shared representations. | Model complexity increases; requires curated datasets for multiple tasks. |

| Data Augmentation (DA) | Artificially creating new training data from existing data. | Universally applicable to increase dataset size and diversity. | Simple to implement; effective for preventing overfitting. | For molecules/materials, must ensure generated data is physically valid. |

| Data Synthesis (GANs) | Using generative models to create new, synthetic data samples. | Augmenting datasets for rare events; balancing imbalanced datasets. | Can generate large volumes of data for exploration. | Can generate unrealistic data; training can be unstable. [12] |

| Federated Learning (FL) | Training a model across decentralized data sources without sharing data. | Multi-institutional collaborations with privacy/IP concerns. | Enables collaboration while preserving data privacy. | Increased communication overhead; complexity in implementation. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking a TL Model

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of a Transfer Learning approach for predicting molecular properties with a small dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Source Model | A pre-trained deep learning model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) on a large public dataset like ZINC (commercial compound library) or QM9 (quantum properties corpus). |

| Target Dataset | A small, curated dataset (< 1000 samples) specific to your research, containing molecular structures (as SMILES strings or graphs) and the target property (e.g., solubility, binding affinity). |

| Fine-Tuning Framework | A deep learning library (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) with the capability to load a pre-trained model and modify its final layers for the new task. |

| Benchmarking Platform | An integrated platform like JARVIS-Leaderboard to ensure reproducible and comparable results against standard baselines. [13] |

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Train a model from scratch on your small target dataset. Evaluate its performance using a suitable metric (e.g., Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for regression).

- Model Adaptation: Load the pre-trained source model. Replace its final output layer(s) to match the output dimension of your target task.

- Fine-Tuning: Re-train the model on your target dataset. It is common practice to use a lower learning rate for the pre-trained layers and a higher one for the new layers to avoid catastrophic forgetting.

- Performance Comparison: Compare the performance of the fine-tuned TL model against the baseline model from Step 1. A significant improvement in metrics like RMSE demonstrates the success of TL.

Visual Workflow for Transfer Learning Protocol:

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers leveraging Generative AI (GenAI) in materials science and biomedical research. It addresses common pitfalls stemming from data scarcity, organizational silos, and biological complexity, framed within the broader thesis of advancing materials GenAI research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can we use generative AI to predict useful new genetic or material sequences? Generative AI models, trained on vast biological or material datasets, can be prompted to autocomplete genetic or structural sequences. They can generate novel, functional sequences that may not exist in nature, which are then validated through lab experiments [14] [15] [16]. For instance, a model like Evo 2 can be prompted with the beginning of a gene sequence, and it will autocomplete it, sometimes creating improved versions [14].

Q2: Our AI model for protein design is producing unrealistic or non-functional outputs. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of the High-Dimensional, Low-Sample-Size problem. Your model might be overfitting due to insufficient or fragmented training data. Scientific data often has billions of features (e.g., pixels, genes) but only thousands of samples, and current AI architectures can struggle to capture the long-range interactions essential for function [17]. Prioritize data quality and diversity over sheer volume.

Q3: What are the primary data-related barriers to achieving robust AI models in science? The main barriers are data fragmentation and a lack of standardized formats. Research data is often scattered across disconnected sources in incompatible formats, making integration and reuse difficult. A 2020 survey indicated that data scientists spend about 45% of their time on data preparation tasks like loading and cleaning data [17].

Q4: How can we mitigate the risk of "AI hallucinations" or biased outputs in our research? Always treat AI outputs as unvalidated hypotheses [15]. Implement a rigorous fact-checking and experimental validation protocol. Be aware that natural language models like ChatGPT are trained on existing literature and thus inherit its biases and inaccuracies; for less biased results, consider models trained directly on raw biological data [15]. Furthermore, disclose the use of AI in your methods section as per publisher guidelines [18].

Q5: Our organization is struggling to move GenAI projects from pilot to full production. What are we missing? Successful deployment requires more than just technology. You need a strategic partner to help with selecting the right use case, optimizing KPIs, preparing data assets, and, crucially, winning buy-in from people across the organization. Employees need training to understand what the AI can and cannot do [19].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution & Validation Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Functional Generated Sequences | - Data Scarcity & Bias: Model trained on small, non-diverse datasets.- Architectural Limitation: Inability to model long-range interactions in sequences or structures. | Solution: Augment training data with multi-source, standardized datasets. Use models with longer context windows.Validation: Synthesize generated sequences (e.g., DNA, material structures) and test function in wet-lab experiments (e.g., assay binding affinity, measure tensile strength) [14] [17] [15]. |

| AI-Generated Hypotheses Are Consistently Wrong | - "AI Hallucination": Model generating plausible but fabricated information.- Training Data Bias: Model is replicating biases and inaccuracies present in its training corpus (e.g., published literature). | Solution: Use AI as a hypothesis generator, not a source of truth. Fine-tune models on raw, unbiased experimental data where possible.Validation: Design controlled experiments specifically to test the AI-generated hypothesis. Use the results to reinforce or correct the model [18] [15]. |

| Inability to Integrate Disparate Datasets | - Proprietary Silos & Fragmentation: Data locked in incompatible formats across departments or institutions.- Lack of Metadata Standards. | Solution: Advocate for and adopt community-wide data standards. Implement internal data governance that rewards curation and sharing.Validation: Benchmark model performance on a unified, curated dataset versus fragmented sources. Measure the time saved in data preparation [17] [20]. |

| Failed Organizational Adoption of AI Tools | - Human Resistance: Lack of understanding and trust in AI systems among researchers.- Misaligned Incentives: Academic and career rewards do not value data curation and tool-building. | Solution: Run targeted training sessions to demonstrate AI capabilities and limitations. Create internal showcases of successful AI-assisted discoveries.Validation: Track and report key adoption metrics: employee usage rates, reduction in process cycle times, and ROI from AI-driven projects [17] [19]. |

Quantitative Data on Challenges and AI Impact

The tables below summarize key quantitative data on the costs of inefficiency and the demonstrated benefits of AI integration in scientific and organizational contexts.

Table 1: The Economic Cost of Organizational Friction and Disengagement This table quantifies the financial impact of the silos and inefficiencies that hinder research progress.

| Metric | Financial Impact | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Global Employee Disengagement | $8.8 Trillion (9% of global GDP) |

Annual lost productivity (Gallup, 2024) [21]. |

| U.S. Workplace Incivility | $2.1 Billion daily ($766 Billion annually) |

Cost of unnecessary meetings, duplicated processes, and communication breakdowns [21]. |

| Internal Friction per Employee | $15,000 per employee / year |

Cost of ineffective meetings, redundant approvals, and information silos [21]. |

| Operational Inefficiency | 20-30% of revenue lost |

Loss due to data silos alone [21]. |

Table 2: Documented Returns on AI Investment in Operations This table provides evidence of the potential efficiency gains from successfully implemented AI.

| Key Performance Indicator | Improvement | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Return on Investment (ROI) | 200% - 300% |

Reported by companies on AI investments [21]. |

| Operational Cost Savings | 35% - 50% |

Savings achieved through AI-powered automation [21]. |

| Cycle Time Reduction | 50% - 70% |

Reduction in process times [21]. |

| AI Tool Adoption | 78% of global organizations |

Use AI in at least one business function [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Generative AI Model for Novel Material Design

This methodology outlines the key steps for developing and validating a generative AI model to design a new bioinspired material with enhanced mechanical properties.

1. Problem Formulation & Data Curation

- Objective: Design a material with a target property (e.g., high strength-to-weight ratio).

- Data Aggregation: Compile a dataset from public repositories (e.g., the Materials Project [17]) and internal experiments. Data must include structural information (e.g., topology, crystal structure) and corresponding measured properties.

- Data Standardization: Overcome fragmentation by converting all data into a unified format with rich, standardized metadata. This step is critical for data scarcity mitigation [17].

2. Model Selection & Training

- Algorithm Choice: Employ a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) or Genetic Algorithm to explore the material design space and generate novel structures [16].

- Training Regime: Train the model on the curated dataset to learn the complex relationships between material structure and its resulting properties.

3. Generation & In-Silico Validation

- Generation: Prompt the trained model to generate new material structures that predictively meet the target property.

- Computational Validation: Use physics-based simulations (e.g., Finite Element Analysis) to screen the generated structures for viability and predicted performance before moving to costly physical experiments [16].

4. Physical Validation & Model Refinement

- Additive Manufacturing: Fabricate the top-performing generated designs using 3D printing. The AI can also be used here to optimize printing parameters [16].

- Experimental Testing: Conduct mechanical tests (e.g., tension, compression) on the fabricated samples to measure actual properties.

- Feedback Loop: Use the experimental results to fine-tune and correct the AI model, creating a continuous improvement cycle [15].

Workflow Visualization

AI-Driven Material Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in AI-Assisted Research |

|---|---|

| Generative AI Models (e.g., Evo 2, GANs) | Core engine for generating novel genetic sequences, protein structures, or material architectures that are informed by all known biological or material data [14] [16]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing | Critical validation tool. Used to synthesize and insert AI-generated DNA sequences into living cells to test their function and therapeutic potential in real-life biological systems [14]. |

| Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing) | Enables the physical fabrication of complex, AI-generated material designs (e.g., bioinspired scaffolds) that would be impossible to make with traditional methods [16]. |

| Smart Contracts / DAOs | A digital tool to reduce organizational silos. Automates and enforces collaboration agreements and data sharing terms between different research institutions, ensuring transparency and trust [21]. |

| Multimodal AI Systems | An emerging class of AI that combines models trained on different types of data (e.g., raw biological sequences and scientific literature) to generate less biased and more comprehensive hypotheses [15]. |

Core Concepts: Data Scarcity in Materials AI

Data scarcity is a fundamental challenge in materials generative AI research. Unlike domains with abundant data, each data point in materials science—representing a synthesized compound or a measured property—can cost months of time and tens of thousands of dollars to produce [22]. This scarcity creates a ripple effect, impacting model accuracy, its ability to generalize to new situations, and the overall speed of scientific innovation.

The table below summarizes the primary causes and immediate consequences of data scarcity in this field.

Table: Fundamental Causes and Direct Effects of Data Scarcity

| Cause of Data Scarcity | Direct Consequence for AI Models |

|---|---|

| High cost and time of experiments [22] | Models are trained on insufficient data, leading to poor performance. |

| Bias towards successful results in literature (lack of "failed" data) [22] | Models never learn to predict failures, limiting their real-world utility. |

| Complexity and diversity of data formats (images, formulas, spectra) [22] | Difficulty in creating large, unified datasets for training. |

| Stringent data privacy and IP protection requirements [22] | Limits data sharing and pooling of resources across organizations. |

The Ripple Effect: Quantifying the Consequences

The initial challenges of data scarcity trigger a cascade of downstream effects that can stall a research program. The following troubleshooting guide addresses the most common issues researchers face.

FAQ 1: My Model's Predictions Are Inaccurate and It Hallucinates New Materials

Problem: The AI model generates material suggestions that are physically implausible or makes property predictions that are wildly inaccurate.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of a model that has been trained on a small, incomplete dataset. Without sufficient examples, the model cannot learn the underlying physical rules of materials science and instead "hallucinates" by making unsupported inferences [23].

Solution:

- Incorporate Physical Knowledge: Use AI platforms that allow for the integration of domain knowledge and scientific constraints to guide the model, preventing it from suggesting impossible structures [22].

- Implement Uncertainty Quantification: Employ models that provide an uncertainty estimate with each prediction. This allows researchers to gauge the reliability of a prediction and focus experimental efforts on the most promising candidates [22].

- Leverage Sequential Learning: Use an active learning loop where the AI model itself suggests the next most informative experiment to perform. This maximizes the value of each new data point, systematically reducing uncertainty [22].

FAQ 2: My Model Fails to Generalize to New Experimental Conditions

Problem: The model performs well on data that resembles its training set but fails miserably when applied to new chemical spaces or synthesis conditions.

Diagnosis: The model has overfit to the limited, and potentially biased, data it was trained on. It has memorized the training examples rather than learning the generalizable relationships between a material's structure and its properties [24].

Solution:

- Data Augmentation: Create modified versions of your existing data to artificially increase diversity. For structural or image data, this can involve techniques like rotation, flipping, or adding noise [24]. For numerical data, generative AI can create realistic synthetic variations [25].

- Use Transfer Learning: Begin with a model pre-trained on a large, general-purpose chemical or materials dataset (even if from a different domain) and fine-tune it on your specific, smaller dataset. This leverages broader chemical knowledge [22].

- Generate Synthetic Data: Use Generative AI models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) or Diffusion Models, to create high-quality synthetic data that fills gaps in your training set, particularly for rare material classes or edge cases [23] [26].

FAQ 3: My Research Workflow Is Too Slow, Stifling Innovation

Problem: The pace of iterating between AI-led prediction and experimental validation is too slow, creating a bottleneck in the discovery pipeline.

Diagnosis: This is a direct consequence of the core data scarcity problem. The high cost and slow speed of each experimental cycle fundamentally limit the speed of innovation.

Solution:

- Develop a Lab Assistant AI: Use natural language processing tools to automatically mine millions of existing research papers and build structured databases [27]. This can be used to pre-train a domain-specific question-answering tool to help researchers quickly get insights and guide experiments [27].

- Adopt a Hybrid AI Approach: Combine data-driven AI models with physics-based simulations. This hybrid approach can achieve accuracy close to high-fidelity simulations at a fraction of the computational cost, allowing for rapid in-silico screening [28].

- Automate with Autonomous Labs: Implement closed-loop systems where AI models directly control robotic laboratory equipment, planning and executing experiments with real-time feedback and adaptive experimentation [28].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Data Scarcity

Protocol 1: Generating Synthetic Data with a Diffusion Model

This protocol outlines the steps for using a generative diffusion model to create synthetic molecular structures or microstructural images to augment a small dataset.

Methodology:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing: Gather and clean all available real-world data (e.g., molecular structures, spectra, or micrograph images). Normalize and transform the data into a format suitable for training [25].

- Model Fine-Tuning: Take a pre-trained diffusion model (e.g., Stable Diffusion for images) and fine-tune it on your specific, domain-limited dataset. This teaches the model the specific style and content of your field [26].

- Prompt-Driven Generation: Use text prompts to generate new, diverse samples. For example, "a polycrystalline microstructure with high porosity" or "an organic molecule with a high photovoltaic efficiency" [26].

- Validation: Rigorously evaluate the generated synthetic data. This can involve:

- Visual Inspection: Domain experts should assess the physical plausibility.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare the statistical properties (e.g., distributions, correlations) of the synthetic data with the original data [25].

- Model Performance Test: Use the synthetic data to augment training and validate that it improves the performance and robustness of a downstream AI model [26].

Protocol 2: Implementing an Active Learning Loop

This protocol uses Sequential Learning to minimize the number of experiments needed to achieve a research goal.

Methodology:

- Initial Model Training: Train an initial AI model on all existing historical data.

- Acquisition Function: Use the model to predict outcomes for a vast number of candidate materials in a search space. An acquisition function (e.g., "upper confidence bound") identifies the candidate(s) that provide the highest potential information gain or performance improvement [22].

- Experiment and Data Addition: Perform the wet-lab or simulation experiment on the top candidate(s) identified in Step 2.

- Model Update: Add the new experimental results (both successes and failures) to the training dataset and update the AI model [22].

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2-4 until a material with the desired target properties is discovered or the research budget is exhausted.

Visualizing the Solution Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for combating data scarcity, combining synthetic data generation, human expertise, and active learning.

Integrated Workflow to Overcome Data Scarcity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential "Reagents" for a Modern AI-Driven Materials Lab

| Tool / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Generative AI Models (GANs, Diffusion) | Creates synthetic data to augment small datasets, simulates edge cases, and protects privacy [23] [26]. |

| Text-Mining Tools (e.g., ChemDataExtractor) | Automatically builds structured databases from millions of research papers, providing a foundational dataset [27]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Methods | Provides a confidence level for each AI prediction, crucial for deciding which experiments to run [22]. |

| Sequential Learning Platform | Implements the active learning loop to optimize the choice of the next experiment, maximizing research efficiency [22]. |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) | Embeds physical laws and constraints directly into the AI model, improving accuracy and preventing unphysical predictions [28]. |

| Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Review | Integrates domain expert knowledge to validate AI suggestions and synthetic data, preventing model collapse and ensuring relevance [23]. |

In the frontiers of scientific research, such as rare disease treatment and novel material discovery, generative AI holds the promise of accelerating breakthroughs. However, its application is fundamentally constrained by a common, critical challenge: data scarcity. In rare diseases, the small patient populations lead to limited clinical data [29] [30]. In material science, the experimental synthesis and characterization of new compounds are inherently time-consuming and resource-intensive, creating a bottleneck of verified data [8]. This technical support center is designed to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical methodologies to overcome these specific hurdles, framing solutions within the broader thesis of addressing data scarcity in generative AI research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

→ Data Acquisition and Quality

Q1: Our generative model for a novel quantum material is producing structurally unstable candidates. How can we guide it toward more plausible outputs?

- Problem: The AI model lacks sufficient examples of stable material structures in its training data, leading to physically implausible suggestions.

- Solution: Implement a constraint-based generation approach. Use a tool like SCIGEN to impose specific geometric or structural rules during the AI's generation process. This steers the model to create candidates that conform to known principles of stability or possess desired lattice structures (e.g., Kagome lattices for quantum properties) [8].

- Protocol:

- Define Constraints: Identify the key structural parameters for your target material (e.g., specific Archimedean lattice types, bond lengths, or coordination numbers).

- Integrate SCIGEN: Apply the SCIGEN code to your generative diffusion model (e.g., DiffCSP). This tool blocks generation steps that deviate from your defined rules.

- Generate & Screen: Run the constrained model to produce candidates. Follow with stability screening using computational simulations (e.g., Density Functional Theory) before proceeding to synthesis [8].

Q2: For our ultra-rare disease study, we lack sufficient patient data to train a predictive model. What are our options?

- Problem: The small number of affected individuals makes it impossible to assemble a large, statistically powerful dataset.

- Solution: Leverage synthetic data generation and data augmentation techniques.

- Protocol:

- Audit Data Gaps: Identify the specific "weak" or under-represented classes in your existing dataset (e.g., a particular genetic variant or disease subtype) [23].

- Generate Synthetic Data: Use generative AI models to create synthetic patient data that mimics the statistical properties of your real-world data. This can fill volume gaps and create specific "edge cases" [23] [1].

- Augment with Advanced ML: Employ transfer learning by pre-training your model on a related, data-rich domain (e.g., a common disease with similar pathways) before fine-tuning it on your rare disease dataset. Few-shot learning techniques can also be applied to learn from very few examples [1].

- Implement HITL Review: Establish a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) review process where domain experts (e.g., clinicians) validate the quality and clinical relevance of the synthetic data to prevent model collapse and ensure ground truth integrity [23].

→ Model Training and Implementation

Q3: Our generative AI model shows bias, performing well only for the majority genetic ancestry in our dataset and failing on underrepresented groups.

- Problem: The training data does not adequately represent the full genetic diversity of the disease population, leading to biased and inequitable models.

- Solution: Actively address dataset imbalance and promote diversity from the outset.

- Protocol:

- Diversity by Design: Intentionally source data from diverse populations, geographic locations, and ancestry groups, as rare disease genetic variation tends to cluster in these groups [29].

- Generate for Balance: Use synthetic data to specifically create data points for underrepresented ancestries or genetic variants, rebalancing the training dataset [23].

- Global Collaboration: Consider designing global clinical trials or data collection efforts from the beginning to maximize inclusivity and access to diverse patient populations [29].

Q4: Our enterprise generative AI pilot for drug discovery is stalled and has shown no measurable impact on our R&D pipeline. What went wrong?

- Problem: The AI tool has been deployed as a static "science project" and has failed to integrate into actual researcher workflows.

- Solution: Focus on integration and adaptability, not just model deployment.

- Protocol:

- Integrate into Workflows: Ensure the AI tool is embedded directly into the scientists' daily tools and processes, rather than being a stand-alone application. It must retain context and learn from user feedback [31].

- Partner Strategically: MIT research indicates that purchasing solutions from specialized vendors or building partnerships succeeds about 67% of the time, far more often than internal builds. Consider partnering with proven AI providers instead of building everything in-house [32] [31].

- Empower Line Managers: Drive adoption from the bottom up by empowering line managers and research teams to experiment and integrate the tools into their specific projects, rather than relying solely on a central AI lab [32].

The tables below summarize key quantitative challenges and resource considerations in these fields.

Table 1: Rare Disease Landscape and Data Challenges (2025)

| Metric | Value | Implication for AI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Global Prevalence | 300-400 million people [30] | Collectively a large problem, but data is fragmented across ~6,000+ distinct diseases [30]. |

| Diseases with Approved Treatment | ~5% [30] | For ~95% of diseases, there is no approved drug, creating a vast space for AI-driven discovery but with little prior data. |

| Average Diagnostic Delay | ~4.5 years (25% wait >8 years) [30] | Highlights the difficulty of data collection and the "diagnostic odyssey" that delays the creation of clean, curated datasets. |

| Genetically-Based Rare Diseases | 72-80% [30] | Confirms the primary data type for AI is genetic and molecular, but with high variability. |

Table 2: AI Model Resource Intensity & Environmental Impact

| Resource | Consumption Context | Scale & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Data center power demand, partly driven by AI [33]. | Global data center electricity consumption projected to be 536 TWh in 2025, potentially doubling to 1,065 TWh by 2030 [34]. |

| Water | Cooling for AI-optimized data centers [33] [34]. | AI data centers may demand up to ~6.4 trillion liters annually by 2027, often located in water-stressed areas [34]. |

| Hardware Lifespan | AI servers in data centers [34]. | Useful lives average only a few years before becoming e-waste, contributing to a fast-growing toxic waste stream [34]. |

Experimental Protocol: SCIGEN for Novel Material Discovery

This protocol details the methodology cited from MIT's research on using the SCIGEN tool to discover new quantum materials [8].

Objective: To generate and synthesize novel materials with specific geometric lattices (e.g., Archimedean lattices) that are associated with exotic quantum properties.

Materials & Workflow: The workflow begins with defining geometric constraints and culminates in the synthesis of predicted stable candidates, with iterative computational screening and validation throughout.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- SCIGEN Code: A computational tool that enforces user-defined structural constraints during the generative process of a diffusion model. Its function is to steer the AI away from random sampling and toward the creation of materials with specific, target geometries [8].

- Generative Diffusion Model (e.g., DiffCSP): The base AI model that generates new material structures by learning from a dataset of known crystals. It is the engine for candidate creation [8].

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster: Essential for running the stability screenings and detailed electronic structure simulations (e.g., using Density Functional Theory) to predict properties like magnetism before synthesis [8].

- Laboratory Synthesis Equipment: This includes furnaces for solid-state reaction synthesis, arc-melters, and other chemistry-specific tools required to physically create the AI-predicted compounds (e.g., TiPdBi and TiPbSb as synthesized in the MIT study) [8].

Experimental Protocol: Synthetic Data for Rare Disease Research

This protocol outlines the use of synthetic data to overcome data scarcity in rare disease research, incorporating a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) review to ensure quality [23].

Objective: To augment a small, real-world dataset of rare disease patients with high-quality synthetic data to train a more robust and less biased predictive AI model.

Materials & Workflow: The process is a continuous cycle of data generation and expert validation, ensuring the synthetic data remains clinically relevant and accurate.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Synthetic Data Generation Platform: A software platform (often based on Generative Adversarial Networks or VAEs) that creates artificial datasets with the same statistical patterns as the real, sensitive patient data without containing any identifiable information, thus addressing privacy concerns [23].

- Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Annotation Interface: A software tool that allows domain experts (e.g., clinical researchers) to efficiently review, validate, and correct the AI-generated synthetic data or model outputs. This is critical for maintaining data quality and preventing model collapse [23].

- Active Learning Framework: A machine learning system that identifies the data points (real or synthetic) where the model is most uncertain or performing poorly. This prioritizes which data should be sent for HITL review, optimizing the use of expert time [23].

- Federated Learning Infrastructure: A distributed AI approach that allows models to be trained across multiple decentralized data sources (e.g., different hospitals) without sharing the raw data. This can be a complementary strategy to access more diverse data while preserving privacy and security.

Building with Less: A Toolkit of Technical Solutions for Data-Efficient AI

Troubleshooting Common Transfer Learning Issues

FAQ: My model is performing poorly after fine-tuning. What could be wrong?

Answer: Poor performance after fine-tuning often stems from task misalignment or negative transfer. This occurs when the knowledge from the source domain is not sufficiently relevant to your target task, or when the transfer mechanism harms performance [35]. To address this:

- Re-evaluate Source Task Relevance: Ensure your pre-trained model comes from a domain fundamentally related to your target task. For instance, a model pre-trained on general molecular structures is more relevant for a new drug property prediction task than one pre-trained on image classification [36] [37].

- Adjust Fine-tuning Rigor: If the tasks are very similar, you can fine-tune more layers of the pre-trained model. If they are less similar, try fine-tuning only the final few layers to avoid overfitting to your smaller target dataset [35].

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: For multi-fidelity data (e.g., mixed computational and experimental results), use a difference architecture that can model the systematic discrepancies between data sources, which has been shown to improve accuracy in materials science applications [38].

FAQ: How can I effectively use transfer learning when my high-fidelity dataset is very small?

Answer: This is a common scenario in fields like drug discovery. The key is to leverage a large, low-fidelity dataset to pre-train a model, then transfer its representations to the small high-fidelity task [36].

- Strategy 1: Feature Augmentation. Train a model on the large, low-fidelity data. Use the predictions or intermediate features from this model as additional input features for a separate model trained on your small, high-fidelity dataset [36].

- Strategy 2: Pre-training and Fine-tuning.

- Pre-training: Pre-train a model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) on the large, low-fidelity dataset. This allows the model to learn generalizable features and patterns [36] [35].

- Fine-tuning: Use your small, high-fidelity dataset to fine-tune the pre-trained model. Employ adaptive readouts (neural network-based aggregation functions) instead of simple sum or mean operations when fine-tuning, as this has been shown to significantly enhance transfer learning performance on sparse tasks [36].

FAQ: What are the primary technical challenges when implementing transfer learning for scientific data?

Answer: The main challenges include:

- Data Heterogeneity: Combining datasets where "equivalent" properties are measured differently introduces hidden errors. Transfer learning architectures must be chosen to preserve these contextual differences [38].

- Negative Transfer: This occurs when transferring knowledge from an irrelevant source task degrades performance on the target task. Careful selection of the pre-trained model is critical [35].

- Readout Function Limitations: In Graph Neural Networks, standard readout functions (e.g., for aggregating atom-level embeddings into a molecule-level representation) can be a bottleneck. Upgrading to adaptive, neural readouts is often necessary for effective knowledge transfer [36].

- Computational Cost: While transfer learning reduces total training time for the target task, the initial pre-training phase on a large dataset can be computationally intensive [35].

Quantitative Data on Transfer Learning Performance

The following table summarizes empirical results from recent studies on transfer learning in scientific domains, demonstrating its effectiveness in overcoming data scarcity.

| Application Domain | Transfer Learning Approach | Reported Performance Improvement | Key Experimental Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery & Quantum Properties [36] | GNNs with Adaptive Readouts & Fine-tuning | Up to 8x improvement in accuracy; required an order of magnitude less high-fidelity data | Sparse high-fidelity tasks with large low-fidelity datasets (e.g., 28M+ protein-ligand interactions) |

| Molecular Property Prediction [36] | Transductive Learning (using actual low-fidelity labels) | Performance improvements between 20% and 60% | Low and high-fidelity labels available for all data points |

| Multi-fidelity Band Gaps (DFT & Exp.) [38] | Difference Architectures | Most accurate model for mixed-fidelity data | Handling systematic differences between data sources (e.g., DFT vs. experimental values) |

| Pharmacokinetics Prediction [39] | Homogeneous Transfer Learning (multi-task model) | Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.53; AUC of 0.85 for regression | Integrated 53 prediction tasks for ADME properties |

Experimental Protocol: Transfer Learning with Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol outlines the methodology for leveraging transfer learning to predict molecular properties using a large, low-fidelity dataset (e.g., high-throughput screening data) to improve performance on a small, high-fidelity dataset (e.g., experimental results) [36].

1. Problem Formulation and Data Preparation

- Define Fidelities: Clearly define your low-fidelity (source) and high-fidelity (target) tasks (e.g., primary vs. confirmatory screening in drug discovery) [36].

- Data Collection: Assemble your datasets. The low-fidelity dataset should be large (e.g., millions of data points), while the high-fidelity dataset is typically small and sparse [36].

- Data Partitioning: Split your high-fidelity data into standard training, validation, and test sets. The training set for the high-fidelity task will be intentionally small to simulate data scarcity.

2. Model Pre-training on Low-Fidelity Data

- Architecture Selection: Choose a suitable Graph Neural Network (GNN) architecture, as molecules are naturally represented as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) [36].

- Pre-training: Train the GNN on the entire large, low-fidelity dataset to predict the low-fidelity property. The goal is for the model to learn general chemical representations [36] [35].

3. Knowledge Transfer and Model Fine-tuning

- Strategy Selection: Choose a transfer strategy:

- Feature Augmentation: Use the pre-trained low-fidelity model to generate features or predictions for the high-fidelity dataset. Train a new model on the high-fidelity data using these features as input [36].

- Fine-tuning (Recommended): Take the pre-trained GNN and replace its output layer. Fine-tune the entire network or a subset of its layers on the small, high-fidelity training dataset [36] [35].

- Critical Modification: Implement an adaptive readout function (e.g., an attention-based mechanism) in the GNN during fine-tuning. This step is crucial for achieving high performance in the transfer, as fixed readouts (like sum or mean) are a common bottleneck [36].

4. Model Evaluation

- Benchmarking: Evaluate the fine-tuned model on the held-out high-fidelity test set.

- Comparison: Compare its performance against a baseline model trained from scratch only on the small high-fidelity dataset. Key metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and R² [36].

Workflow: Transfer Learning for Sparse Data

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a pre-training and fine-tuning transfer learning strategy, as applied to a molecular property prediction task.

This table details essential "research reagents" – in this context, key computational tools and data types – required for implementing transfer learning in data-scarce scientific domains.

| Item / Resource | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A deep learning architecture that operates directly on graph-structured data, making it ideal for representing molecules (atoms=bonds) and materials [36]. |

| Pre-trained Model | A model (e.g., a GNN) that has already been trained on a large, data-rich source task. This model contains the generalizable knowledge to be transferred [36] [35]. |

| Low-Fidelity Dataset | A large, often noisier or less precise dataset (e.g., from high-throughput screening or approximate calculations) used for the initial pre-training of the model [36]. |

| High-Fidelity Dataset | The small, expensive-to-acquire, and high-quality target dataset (e.g., from precise experiments or high-level theory calculations) on which the pre-trained model is fine-tuned [36]. |

| Adaptive Readout Function | A neural network component in a GNN that learns how to best aggregate atom-level embeddings into a molecule-level representation, crucial for effective transfer learning [36]. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Generative Models for Materials Science

1. Why are my synthetic material microstructures visually convincing but scientifically inaccurate? This is a common problem known as model "hallucination," where outputs violate fundamental physical or biological principles [40]. To address this:

- Action: Incorporate domain-expert validation into your evaluation protocol. Standard quantitative metrics (like FID or SSIM) alone are insufficient for capturing scientific relevance [40].

- Action: For Diffusion Models, ensure your training data is large and diverse enough to represent all essential material properties, as these models can overlook infrequent but critical details [41].

- Action: For VAEs, which can produce blurry outputs, the inaccuracies might stem from their probabilistic nature and pixel-based loss functions. They are better suited for scenarios where such inaccuracies can be tolerated [41] [42] [43].

2. My GAN training for generating composite fiber images is unstable. What can I do? GANs are prone to instability and mode collapse, where the generator produces a limited variety of samples [42] [43].

- Action: Implement techniques to enforce a Lipschitz constraint, such as gradient penalty or spectral normalization, on your discriminator. This has been shown to significantly improve training stability [43].

- Action: Consider using a variant like StyleGAN, which has demonstrated high perceptual quality and structural coherence in generating scientific images like microCT scans [40].

3. How can I use a pre-trained text-to-image diffusion model for a niche material concept it wasn't trained on? Full fine-tuning on a small, specialized dataset is often ineffective. Instead, use a parameter-efficient method.

- Action: Optimize a "pseudo-prompt" in the model's text encoder to represent your new material concept. This approach adapts the model to new domains from just a few labelled examples without disturbing its ability to generate other concepts [44].

4. The computational cost of generating high-resolution synthetic images is too high. What are my options? This is a key challenge, particularly for Diffusion Models [43].

- Action: For speed and lower inference cost, GANs are a strong choice once trained, as they generate new content quickly without probabilistic assessment [41].

- Action: If using a Diffusion Model, consider a Latent Diffusion approach (like Stable Diffusion), which operates in a compressed latent space rather than pixel space, drastically reducing computational demands [40].

- Action: VAEs are often computationally less intensive than both GANs and Diffusion Models and can perform better with limited or low-quality training data, making them a good option for initial experiments [41].

5. How do I ensure my synthetic data for a weed classification task actually improves model performance? Merely generating more data is not enough; the data must be diverse and semantically meaningful.

- Action: Move beyond basic transformations (flips, rotations). Use an image-editing technique like SDEdit with a pre-trained diffusion model to create variations that alter high-level semantic attributes (e.g., weed species in a scene) while respecting their inherent invariances [44].

- Action: Systematically evaluate your model's performance on a held-out real-world test set after augmenting your training data with synthetics, as demonstrated in few-shot classification tasks [44].

Comparative Analysis of Generative Models

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of the three primary generative models to help you select the right one for your application.

| Feature | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Diffusion Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Two neural networks (generator & discriminator) compete in an adversarial game [41] [43]. | Encoder-decoder architecture that learns a probabilistic latent space of the data [40] [41]. | Iterative noising (forward process) and denoising (reverse process) [44] [43]. |

| Best For | High-fidelity, high-resolution image synthesis; fast inference [41] [42]. | Scenarios with limited or poor-quality data; applications requiring diversity over sharpness [41]. | High-fidelity and diverse sample generation; state-of-the-art image quality [40] [42]. |

| Key Strengths | High sharpness and detail in outputs [41] [42]. | Stable training, good data coverage, and meaningful latent space [42] [43]. | High-quality, diverse outputs; less prone to mode collapse than GANs [44] [42]. |

| Common Challenges | Training instability, mode collapse, vanishing gradients [42] [43]. | Often generates blurry or low-fidelity images [42] [43]. | Computationally intensive and slow inference speed [41] [43]. |

| Ideal Materials Science Use Case | Generating high-resolution, perceptually realistic microCT scans or composite fiber images [40]. | Exploring a wide range of potential molecular structures in a low-data regime [41] [45]. | Augmenting a dataset with diverse and high-quality variations of material microstructures [40] [44]. |

Experimental Protocol: Data Augmentation with Diffusion Models (DA-Fusion)

This protocol is adapted from a method designed to address data scarcity by editing images to change their semantics using a pre-trained diffusion model [44].

Objective: To enhance a small dataset of material images (e.g., crystal structures, micrographs) for improved performance in a downstream classification or regression task.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the DA-Fusion data augmentation methodology.

Materials & Methodology:

- Input: A small, labeled dataset of material images (e.g., 50-100 images per class).

- Model: A pre-trained text-to-image diffusion model (e.g., Stable Diffusion).

- Concept Adaptation:

- Instead of fine-tuning the entire model, which requires massive data, optimize a "pseudo-prompt" for each material concept or class in your dataset [44].

- This pseudo-prompt is a set of latent vectors fed into the model's text encoder. It is fine-tuned using your small image set to better represent your specific domain, guiding the diffusion process more effectively.

- Image Generation:

- Use an image-editing technique like SDEdit [44]. Feed your original image into the reverse diffusion process partway through the Markov chain. The model, guided by the fine-tuned pseudo-prompt, will "denoise" your image into a novel variation, altering semantics like texture, morphology, or structure while preserving the core object.

- Validation:

- Crucially, subject the synthetic images to expert validation by a materials scientist to ensure the generated variations are physically plausible and accurate [40].

- Downstream Task:

- Combine the validated synthetic data with your original dataset to train a property prediction model (e.g., a CNN). Evaluate its performance on a held-out test set of real images to measure the improvement gained from augmentation.

The table below lists essential computational tools and datasets for conducting generative materials science research.

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Matminer Database [46] | Materials Database | Provides curated datasets on material properties; used as a benchmark for training and evaluating generative models in data-scarce scenarios. |

| International Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [47] | Materials Database | A comprehensive repository of inorganic crystal structures used for training models on high-thermal-stability materials. |

| CoRE MOF Database [47] | Materials Database | Contains thousands of computed metal-organic framework structures; essential for generative tasks focused on porous materials. |

| Stable Diffusion [44] | Pre-trained Model | An off-the-shelf, open-source diffusion model that can be adapted via fine-tuning or prompt-engineering for material image augmentation. |

| CGCNN [46] | Predictive Model | A Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network; used as a downstream property predictor to evaluate the quality of synthetic data. |

| Con-CDVAE [46] | Generative Model | A conditional generative model based on a VAE; used specifically for generating crystal structures conditioned on target properties. |

| Expert Validation Protocol [40] | Evaluation Method | A qualitative assessment where domain experts verify the scientific integrity and physical plausibility of generated synthetic images. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the primary goal of Active Learning in materials informatics? The primary goal is to maximize model performance while minimizing the cost of data acquisition. AL achieves this by iteratively selecting the most informative data points from a large pool of unlabeled data for expert labeling, thus substantially reducing the volume of labeled data required to build robust predictive models [48].

FAQ 2: My generative model for molecules struggles with synthetic accessibility. Can AL help? Yes. AL can be integrated directly into a generative AI workflow to address this. By using a "chemoinformatic oracle" within an active learning cycle, generated molecules can be automatically evaluated for properties like synthetic accessibility. Molecules that meet a set threshold are selected and used to fine-tune the model, guiding future generations toward more synthesizable compounds [49].

FAQ 3: How do I choose the best AL query strategy for my regression task? The optimal strategy often depends on your data budget. In the early stages of learning with very little data, uncertainty-based (e.g., LCMD, Tree-based-R) and diversity-hybrid (e.g., RD-GS) strategies have been shown to clearly outperform random sampling and geometry-only heuristics [48]. As the labeled set grows, the performance gap between different strategies typically narrows [48].

FAQ 4: What are the consequences of ignoring data diversity in my AL strategy? Focusing solely on uncertainty without considering diversity can lead the model to select very similar, highly uncertain data points from a single region of the feature space. This is inefficient. Incorporating diversity ensures a broader exploration of the chemical space, which helps build more generalizable and robust models and prevents the model from getting stuck on a specific type of difficult sample [48].

FAQ 5: How does AL fit into an Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) pipeline? In an AutoML pipeline, the surrogate model that the AL strategy uses to query new data is no longer static. The AutoML optimizer might switch between different model families (e.g., from linear regressors to tree-based ensembles) across AL iterations. Therefore, it's crucial to choose an AL strategy that remains robust and effective even when the underlying model and its uncertainty calibration are dynamically changing [48].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Benchmarking AL Strategies for Small-Sample Regression

This protocol is based on a comprehensive benchmark study for materials science regression tasks [48].

- Problem Setup: Define a pool-based AL scenario. Start with an initial dataset

Lcontaining a small number of labeled samples(x_i, y_i)and a large poolUof unlabeled samplesx_i[48]. - Initialization: Randomly select

n_initsamples fromUto form the initial labeled training set [48]. - Iterative Active Learning Loop: For a predetermined number of steps, perform the following:

- Model Training: Fit an AutoML model on the current labeled set

L. The AutoML should automatically handle model selection and hyperparameter tuning [48]. - Query Strategy: Apply one or more AL strategies (see Table 1) to select the most informative sample

x*from the unlabeled poolU[48]. - Expert Labeling: Obtain the target value

y*for the selected sample (e.g., through experimental synthesis or characterization). - Dataset Update: Expand the labeled set:

L = L ∪ {(x*, y*)}and removex*fromU[48].

- Model Training: Fit an AutoML model on the current labeled set

- Evaluation: In each iteration, test the model's performance on a held-out test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and the Coefficient of Determination (R²). Compare the learning curves of different AL strategies against a random sampling baseline [48].

Protocol 2: Integrating AL with a Generative AI Model for Drug Design

This protocol outlines a nested AL workflow for generative molecular design [49].

- Initial Model Training: Train a generative model (e.g., a Variational Autoencoder) on a general set of molecules. Fine-tune it on a small, target-specific training set [49].

- Molecule Generation: Sample the model to generate a new set of candidate molecules [49].

- Inner AL Cycle (Chemical Property Optimization):

- Use chemoinformatic oracles (drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, similarity filters) to evaluate generated molecules.

- Molecules passing the thresholds are added to a "temporal-specific" set.

- Use this set to fine-tune the generative model.

- Repeat for a set number of cycles to improve chemical properties [49].

- Outer AL Cycle (Affinity Optimization):

- After inner cycles, evaluate molecules from the "temporal-specific" set using a physics-based oracle (e.g., molecular docking simulations).

- Molecules with favorable docking scores are promoted to a "permanent-specific" set.

- Use this set to fine-tune the generative model, pushing it to generate molecules with higher predicted affinity [49].

- Candidate Selection: After multiple outer cycles, apply stringent filtration (e.g., advanced molecular dynamics simulations like PELE) to select the most promising candidates for synthesis and experimental testing [49].

Diagram 1: Core Active Learning Workflow

Diagram 2: Nested AL for Generative AI

Performance Data & Strategy Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Active Learning Strategy Principles [48]

| Principle | Description | Key Insight from Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Estimation | Selects data points where the model's prediction is most uncertain (e.g., using Monte Carlo Dropout for regression). | Most effective in early, data-scarce stages; outperforms random sampling. |

| Diversity | Selects a diverse batch of points to maximize coverage of the feature space. | Pure diversity heuristics (e.g., GSx) can be outperformed by hybrid methods. |

| Hybrid (Uncertainty + Diversity) | Combines uncertainty and diversity criteria to select points that are both informative and representative. | Methods like RD-GS clearly outperform other strategies early in the acquisition process [48]. |

| Expected Model Change | Selects data points that would cause the greatest change to the current model parameters. | Evaluated in benchmarks; performance is context-dependent. |

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of Selected AL Strategies in AutoML (Small-Sample Regime) [48]

| AL Strategy | Underlying Principle | Early-Stage Performance (Data-Scarce) | Late-Stage Performance (Data-Rich) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sampling | Baseline (Random Selection) | Baseline | All methods converge, showing diminishing returns from AL [48]. |

| LCMD | Uncertainty | Clearly outperforms baseline [48] | Converges with other methods. |

| Tree-based-R | Uncertainty | Clearly outperforms baseline [48] | Converges with other methods. |

| RD-GS | Hybrid (Diversity) | Clearly outperforms baseline [48] | Converges with other methods. |

| GSx | Diversity (Geometry-only) | Outperformed by uncertainty and hybrid methods [48] | Converges with other methods. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for an AL-Driven Generative AI Pipeline [49]

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | The core generative model that learns a continuous latent representation of molecules and can generate novel molecular structures [49]. |

| Chemoinformatic Oracle | A computational tool (or set of rules) that evaluates generated molecules for key properties like drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of 5) and synthetic accessibility (SA) score [49]. |

| Physics-based Oracle | A molecular modeling tool, such as a molecular docking program, that predicts the binding affinity and pose of a generated molecule against a target protein. This provides a more reliable, physics-guided evaluation of target engagement [49]. |

| Target-Specific Training Set | A (often small) curated set of molecules known to interact with the biological target of interest. This is used for the initial fine-tuning of the generative model to impart some target-specific knowledge [49]. |

| Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) | A framework that automates the process of selecting the best machine learning model and its hyperparameters. This is particularly valuable in AL where the underlying model may change iteratively [48]. |

Embracing Few-Shot and One-Shot Learning (OSL) for Ultra-Low-Data Scenarios

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My model is memorizing the few samples I have instead of learning general patterns. What can I do? A: You are describing overfitting, a primary challenge in few-shot learning [50]. To address this:

- Use Data-Level Approaches: Apply extensive data augmentation to artificially expand your dataset. Alternatively, integrate synthetic data generated by models like Conditional Variational Autoencoders (cVAE) or Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which have shown promise in materials science for generating realistic data points [51] [52].

- Apply Regularization: Use techniques like dropout and weight decay to prevent the model from becoming overly complex for the small dataset [50].

- Leverage a Base Dataset: Perform meta-training on a large, related base dataset (e.g., common material properties) before fine-tuning on your specific, small-scale target task. This teaches the model to extract general features first [52].

Q: How can I make a model trained on general data work for my specific material property prediction task? A: The key is to learn or create an embedding space that generalizes.