Overcoming Anthropogenic Bias in Materials Datasets: Strategies for Equitable AI-Driven Discovery

This article addresses the critical challenge of anthropogenic bias in materials science datasets, which can skew AI predictions and hinder the discovery of novel materials.

Overcoming Anthropogenic Bias in Materials Datasets: Strategies for Equitable AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of anthropogenic bias in materials science datasets, which can skew AI predictions and hinder the discovery of novel materials. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the origins and impacts of these biases, from skewed data sourcing in scientific literature to the limitations of human-centric feature design. The content provides a comprehensive framework for mitigating bias, covering advanced methodologies like multimodal data integration, foundation models, and dynamic bias glossaries. It further evaluates the performance of different AI models on biased versus debiased data and discusses the crucial trade-offs between fairness, model accuracy, and computational sustainability. The conclusion synthesizes key strategies for building more robust, equitable, and reliable materials informatics pipelines, outlining their profound implications for accelerating biomedical and clinical research.

The Unseen Hand: Defining and Diagnosing Anthropogenic Bias in Materials Data

FAQs: Understanding the Core Concepts

What is Anthropogenic Bias?

Anthropogenic bias refers to the systematic errors and distortions in scientific data that originate from human cognitive biases, heuristics, and social influences. Because most experiments are planned by human scientists, the resulting data can reflect a variety of human tendencies, such as preferences for certain reagents, reaction conditions, or research directions, rather than an objective exploration of the problem space. These biases become embedded in datasets and are often perpetuated when these datasets are used to train machine-learning models [1].

How is Anthropogenic Bias Different from Other Biases?

While the term "bias" in machine learning often refers to statistical imbalances or algorithmic fairness, anthropogenic bias specifically points to the human origin of these distortions. It is the "human fingerprint" on data, stemming from the fact that scientific data is not collected randomly but through human-designed experiments. Key characteristics that differentiate it include:

- Origin: Rooted in human psychology and sociology [2] [1].

- Manifestation: Seen in the non-random, often power-law distributions of reagent choices and reaction conditions in scientific literature [1].

- Persistence: Once embedded in a dataset, it can be inherited and amplified by AI systems, which then influence future human decisions, creating a feedback loop [3].

Why is Mitigating Anthropogenic Bias Critical in Materials Science and Drug Development?

In high-stakes fields like materials science and pharmaceutical R&D, anthropogenic bias can hinder progress and waste immense resources.

- In Materials Science: It can limit exploratory synthesis, causing researchers to overlook promising regions of chemical space because they are anchored to historically popular "recipes" [1].

- In Drug Development: Cognitive biases like confirmation bias (overweighting evidence that supports a favored belief) and the sunk-cost fallacy (continuing a project based on past investment rather than future potential) can lead to the advancement of unlikely drug candidates and contribute to the high failure rate in Phase III trials [4]. Mitigating these biases is directly linked to increasing R&D efficiency and potentially delivering more equitable healthcare solutions [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: My Machine Learning Model Performs Well on Published Data but Fails in Real-World Exploration

Potential Cause: Your training data is likely contaminated by anthropogenic bias. The model has learned the historical preferences of human scientists rather than the underlying physical laws of what is possible.

Diagnosis and Mitigation Protocol:

| Step | Action | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnose | Analyze the distribution of reactants and conditions in your training data. Check for power-law distributions where a small fraction of options dominates the dataset. [1] | To identify the presence and severity of anthropogenic bias in the dataset. |

| 2. Diversify | Introduce randomness into your data collection. Actively perform experiments with under-represented or randomly selected reagents and conditions. [1] | To break the cycle of historical preference and collect a more representative dataset. |

| 3. Validate | Benchmark your model's performance on a smaller, randomized dataset (e.g., from Step 2) versus the original human-selected dataset. | To confirm that the model trained on diversified data has better generalizability and exploratory power. [1] |

Issue 2: My Research Team is Overly Anchored to Established Protocols, Stifling Innovation

Potential Cause: This is a classic symptom of anchoring bias (relying too heavily on initial information) and status quo bias (a preference for the current state of affairs). [2] [4]

Mitigation Strategies:

- Prospectively Set Decision Criteria: Before starting a project, define quantitative go/no-go criteria for success. This bases decisions on pre-defined metrics rather than historical investment or gut feeling. [4]

- Conduct a "Pre-mortem": Have the team imagine a future failure and work backward to generate plausible reasons for that failure. This technique, aimed at countering excessive optimism and overconfidence, helps identify potential flaws in the current plan. [4]

- Implement Planned Leadership Rotation: Rotating project leaders can bring fresh perspectives and help challenge entrenched assumptions and "inappropriate attachments" to legacy projects. [4]

Issue 3: My AI Assistant is Leading My Team to Make Systematic Errors

Potential Cause: Humans can inherit biases from AI systems. If the AI was trained on biased historical data, its recommendations will be skewed. Team members may then uncritically adopt these biases, reproducing the AI's errors even when making independent decisions. [3]

Inheritance Mitigation Protocol:

- Awareness and Training: Educate all users that AI systems can possess and propagate systematic biases. They are tools for assistance, not oracles of truth.

- Critical Supervision Mandate: Implement a protocol where AI recommendations must be critically evaluated against fundamental principles and contradictory evidence. Do not allow AI advice to be the sole basis for a decision. [3]

- Bias Auditing: Regularly test the AI system on edge cases and randomized experiments to characterize its biases. Update the team on these findings so they know what errors to look for. [5]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantifying Anthropogenic Bias in a Chemical Dataset

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used in the Nature study "Anthropogenic biases in chemical reaction data hinder exploratory inorganic synthesis." [1]

Objective: To measure the presence and extent of anthropogenic bias in a dataset of chemical reactions, specifically in the choice of amine reactants for the hydrothermal synthesis of metal oxides.

Materials and Reagents:

- Data Source: Crystallographic databases (e.g., the Cambridge Structural Database, ICSD).

- Analysis Software: A data analysis environment (e.g., Python with Pandas, NumPy).

- Experimental Validation: Standard laboratory equipment and reagents for hydrothermal synthesis.

Procedure:

Data Extraction:

- Query the database for all reported crystal structures of amine-templated metal oxides synthesized via hydrothermal methods.

- Extract the chemical identity of every amine reactant used.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the frequency of use for each unique amine.

- Plot the frequency distribution. A power-law distribution, where a small number of amines account for the majority of reported structures, is a strong indicator of anthropogenic bias.

- Statistically fit the distribution to confirm it follows a power law.

Experimental Validation (Randomized Testing):

- Design a set of experiments (e.g., 500+ reactions) where amines and other reaction conditions (temperature, concentration) are selected randomly from a defined chemical space, not based on literature popularity.

- Execute these experiments and record the success rate (e.g., crystal formation).

- Compare the success rates of popular amines versus unpopular/random amines. The key finding demonstrating bias is that popularity is uncorrelated with success rate.

Expected Outcome: The study demonstrated that machine-learning models trained on a smaller, randomized dataset outperformed models trained on larger, human-selected datasets in predicting successful synthesis conditions, proving the value of mitigating this bias. [1]

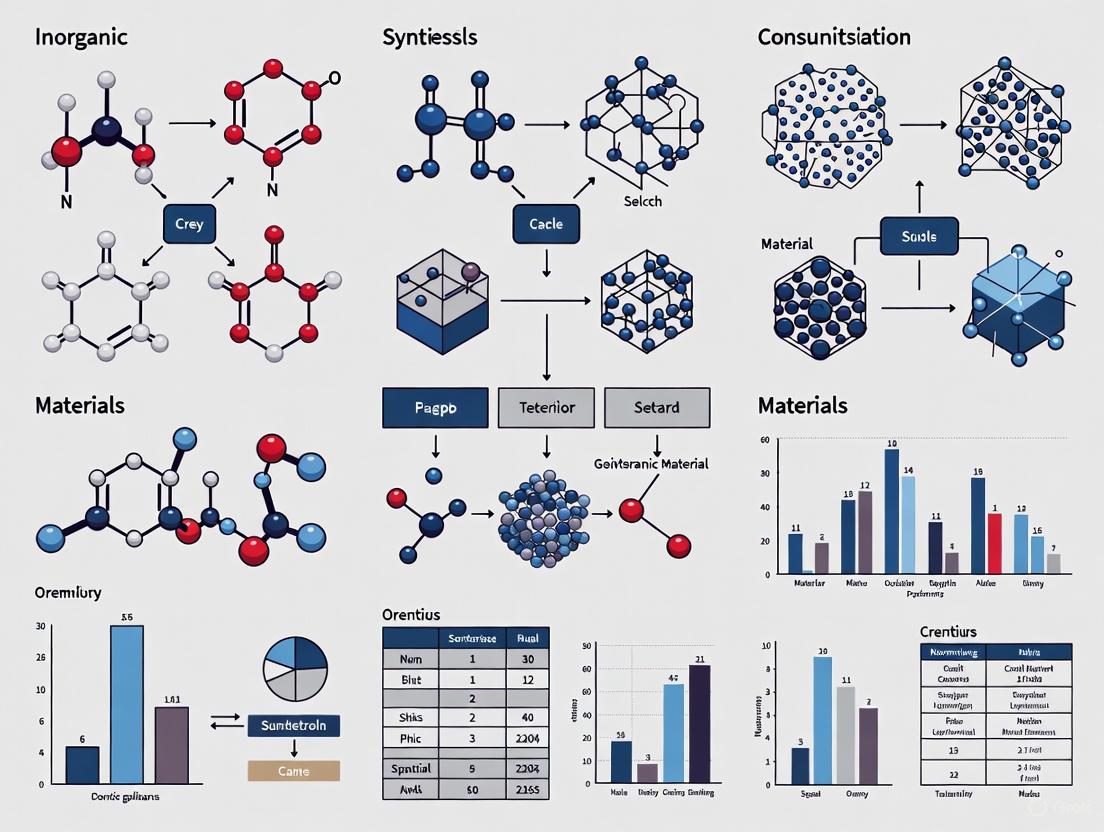

Workflow Diagram: The Lifecycle and Mitigation of Anthropogenic Bias

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential "reagents" for any research program aimed at overcoming anthropogenic bias.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Randomized Experimental Design | The primary tool for breaking the cycle of bias. By randomly selecting parameters (reagents, conditions) from a defined space, researchers can generate data that reflects what is possible, not just what is popular. [1] |

| Pre-registered Analysis Plans | A document created before data collection that specifies the hypothesis, methods, and statistical analysis plan. This helps counteract confirmation bias and p-hacking by committing to a course of action. [4] |

| Quantitative Decision Frameworks | Pre-defined, quantitative go/no-go criteria for project advancement. This mitigates biases like the sunk-cost fallacy and over-optimism by forcing decisions to be based on data rather than emotion or historical investment. [4] |

| Blinded Evaluation Protocols | In experimental evaluation (e.g., assessing material properties), the evaluator should be blinded to the group assignment (e.g., which sample came from which synthetic condition). This reduces expectation bias. |

| Bias-Auditing Software | Scripts and tools (e.g., in Python/R) designed to analyze datasets for imbalances, power-law distributions, and representativeness across different subgroups. This is the "microscope" for detecting bias. [5] |

| Multidisciplinary Review Panels | Incorporating experts from different fields and backgrounds provides diversity of thought, which helps challenge entrenched assumptions and "champion bias" by ensuring no single perspective dominates. [4] [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most common source of bias in materials data that leads to prediction failures? The most common source is poor or non-representative source data [7]. This often occurs when the dataset used for training does not accurately reflect the real-world conditions or material populations the model is meant to predict. For instance, a dataset containing mostly male patients will lead to incorrect predictions for female patients when the model is deployed in a hospital [8]. A representative sample is far more valuable than a large but biased one [7].

FAQ 2: How can I tell if my dataset has inherent biases? A diagnostic paradigm called Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL) can be used to identify hidden biases [9]. This method unifies shortcut representations in probability space and utilizes a suite of models with different inductive biases to efficiently learn and identify the "shortcut hull" – the minimal set of shortcut features – within a high-dimensional dataset [9]. This helps diagnose dataset shortcuts that conventional methods might miss.

FAQ 3: My model performs well on test data but fails in real-world predictions. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of shortcut learning [9]. Your model is likely exploiting unintended correlations or "shortcuts" in your training dataset that do not hold true in practice. For example, a model might learn to recognize a material's defect based on background noise in lab images, a feature absent in field inspections. The Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL) framework is specifically designed to uncover and eliminate these shortcuts for more reliable evaluation [9].

FAQ 4: What is a practical method to reduce bias without destroying my model's overall accuracy? A technique developed by MIT researchers involves identifying and removing specific, problematic training examples [8]. Instead of blindly balancing a dataset by removing large amounts of data, this method pinpoints the few datapoints that contribute most to failures on minority subgroups. By removing only these, the model's overall accuracy is maintained while its performance on underrepresented groups improves [8].

FAQ 5: Beyond data selection, what other statistical pitfalls should I avoid? Several other pitfalls can undermine your predictions [7]:

- Fishing for answers (p-hacking): Performing many statistical tests on your data until you find a significant result dramatically increases the rate of false positives [7].

- Simpson's Paradox: A trend that appears in different subgroups of data disappears or reverses when these groups are combined. This underscores the importance of understanding subgroup structures [7].

- Mixing correlation and causation: A statistical correlation does not mean one factor causes another; an underlying, unaccounted factor may be influencing both [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Fails on Minority Subgroups or Rare Events

Description: The predictive model performs well on common material types or frequent failure modes but fails to accurately predict behavior for rare materials or infrequent failure progressions.

Solution:

- Identify Failure-Causing Data: Use the TRAK method or similar techniques to trace incorrect predictions back to the specific training examples that contributed most to the error [8].

- Selective Data Removal: Remove only these identified problematic datapoints from the training set. This is more efficient than removing large swaths of data [8].

- Retrain Model: Retrain the model on the refined dataset. This approach has been shown to boost worst-group accuracy while preserving the model's general performance [8].

Problem: Model Learns Spurious Correlations (Shortcuts)

Description: The model's predictions are based on unintended features in the data (e.g., image backgrounds, specific lab artifacts) rather than the actual material properties or defects of interest.

Solution:

- Apply the SHL Framework: Implement the Shortcut Hull Learning paradigm to diagnose your dataset [9]. This involves:

- Unified Representation: Formalizing a unified representation of data shortcuts in probability space.

- Model Suite: Employing a suite of diverse models with different inductive biases to collaboratively learn the "shortcut hull" of the dataset [9].

- Build a Shortcut-Free Evaluation Framework: Use the insights from SHL to establish a comprehensive, shortcut-free evaluation framework, which may involve creating new, validated datasets that eliminate the identified shortcuts [9].

Problem: Inaccurate Prediction of Material Failure Progressions

Description: Models fail to predict how and when a material will fail, often because they cannot accurately capture the evolution of microstructural defects like voids.

Solution:

- Quantify Defect Topology: Use non-destructive monitoring techniques like X-ray computed tomography (X-CT) to capture the internal state of materials. Then, apply Persistent Homology (PH) to precisely quantify the topology (size, density, distribution) of internal voids and defects from the complex 3D data [10].

- Implement a Topology-Based Deep Learning Model: Feed the PH-encoded topological features into a deep learning model. This workflow has been demonstrated to reliably predict local strain and fracture progress with high accuracy, significantly outperforming models that do not use topological encoding [10].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL) for Bias Diagnosis

Objective: To efficiently identify and define the "shortcut hull" – the minimal set of shortcut features – in a high-dimensional materials dataset [9].

Methodology:

- Probabilistic Formulation: Formalize the data and potential shortcuts within a probability space. Let ( (\Omega,{{{\mathcal{F}}}},{\mathbb{P}}) ) represent the probability space, where the label information is contained in the σ-algebra generated by Y, σ(Y) [9].

- Model Suite Deployment: Employ a suite of machine learning models with diverse inductive biases (e.g., CNNs, Transformers) to analyze the same dataset [9].

- Collaborative Learning: Use a collaborative mechanism across these models to learn the unified representation of shortcuts and define the SH, which is the minimal set of shortcut features [9].

- Framework Validation: Validate the diagnosis by constructing a new, shortcut-free dataset and re-evaluating model capabilities to ensure the bias has been mitigated [9].

Protocol 2: Predicting Failure via Void Topology

Objective: To predict failure-related properties (e.g., local strain, fracture progress) of structural materials based on the topological state of their internal defects [10].

Methodology:

- Dataset Generation:

- Perform tensile or fatigue mechanical tests on material specimens (e.g., low-alloy ferritic steel).

- Use X-ray Computed Tomography (X-CT) to non-destructively scan specimens at various stages of deformation, capturing the evolution of internal voids [10].

- Topological Feature Extraction:

- Apply Persistent Homology (PH), a tool from topological data analysis, to the X-CT images. PH quantifies the size, density, and distribution of voids, encoding them into topological features [10].

- Model Development and Training:

- Develop a deep learning model that uses the PH-encoded features as input.

- Train the model to output failure-related properties, such as local strain or a measure of fracture progress [10].

- Validation:

- Test the model's predictive accuracy on unseen X-CT data, achieving low mean absolute errors (e.g., 0.09 for local strain) by focusing on the key topological features of internal defects [10].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Bias Mitigation Techniques

| Technique | Core Approach | Key Performance Metric | Result | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Data Removal [8] | Remove specific datapoints causing failure | Worst-group accuracy & overall accuracy | Improved worst-group accuracy while removing ~20k fewer samples than conventional balancing [8] | Maintains high overall model accuracy |

| Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL) [9] | Diagnose and eliminate dataset shortcuts | Model capability evaluation on a shortcut-free topological dataset | Challenged prior beliefs; found CNNs outperform Transformers in global capability [9] | Reveals true model capabilities beyond architectural preferences |

| Persistent Homology (PH) with Deep Learning [10] | Use quantified void topology to predict failure | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for local strain prediction | MAE of 0.09 with PH vs. 0.55 without PH [10] | Precisely reflects real defect state from non-destructive scans |

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for Material Failure Prediction

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| X-ray Computed Tomography (X-CT) Scanner | Enables non-destructive, 3D imaging of a material's internal microstructure, capturing the evolution of defects like voids and cracks over time [10]. |

| Persistent Homology (PH) | A mathematical framework for quantifying the shape and structure of data. It is used to extract key topological features (size, density, distribution) of voids from complex X-CT data [10]. |

| Low-Alloy Ferritic Steel Specimens | A representative structural material used for generating fracture datasets via tensile and fatigue testing to validate prediction methods [10]. |

| Model Suite (e.g., CNNs, Transformers) | A collection of models with different inherent biases used collaboratively in the SHL framework to identify dataset shortcuts and learn a unified representation of bias [9]. |

| Deep Learning Model (LSTM + GCRN) | A specific architecture combining Long Short-Term Memory (for temporal evolution) and Graph-Based Convolutional Networks (for relational data) to predict rare events like abnormal grain growth [11]. |

Workflow Visualizations

Diagram: Failure Prediction via Topology

Diagram: Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL) Process

Troubleshooting Guides

1. How can I identify and correct for non-representative sourcing in existing materials data?

- Problem: A predictive model for a new polymer performs poorly because the training data is heavily biased towards materials studied in older literature, under-representing modern synthetic pathways.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Perform Data Provenance Analysis: Trace the origin of each data point in your dataset. Create a table to quantify the sources.

- Conduct Statistical Bias Testing: Compare the distribution of key features (e.g., elements, synthesis methods, property ranges) in your dataset against a known, broader benchmark or a randomly sampled target population.

- Validate with a Holdout Set: Test your model's performance on a small, carefully curated set of materials that are known to be outside the suspected bias of the main dataset.

- Resolution:

- Short-term: Apply statistical re-weighting techniques to your data, giving higher importance to examples from under-represented sources during model training [12].

- Long-term: Implement a proactive data collection strategy that prioritizes filling the identified gaps, potentially using automated literature extraction tools focused on specific journals or time periods [13].

2. What is the methodology for diagnosing flawed data extraction from scientific literature?

- Problem: A database of catalyst properties contains significant errors because the automated system misread superscripts and subscripts in published tables.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Spot-Check with Manual Verification: Randomly select a subset of extracted data (e.g., 100 data points) and manually verify them against the original source document (PDF, HTML).

- Run Plausibility Filters: Programmatically flag extracted values that fall outside physically or chemically plausible ranges (e.g., negative formation energies, bond lengths orders of magnitude too large).

- Cross-Reference with Clean Databases: Compare the extracted data against high-quality, manually curated databases to identify significant outliers.

- Resolution:

- Retrain or fine-tune the data extraction model using a corrected dataset that includes examples of the previously misread characters [13].

- Integrate a post-processing step that uses a rules-based system (e.g., using regular expressions) to check for common formatting errors in numerical values and chemical formulas [13].

- Employ multimodal extraction models that combine text and image analysis to correctly interpret complex notations in figures and tables [13].

3. How can I overcome the historical focus in materials data to discover novel compounds?

- Problem: A generative AI model for new battery materials only proposes minor variations of known lithium-based compounds, failing to suggest promising sodium- or magnesium-based alternatives.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Analyze Temporal Trends: Plot the year of discovery/publication against the chemical space (e.g., using principal component analysis) of your dataset to visualize historical biases.

- Perform "Success Cause Analysis": Do not just analyze failures. Systematically study the factors that led to past successful discoveries to understand the research paradigms that may now be limiting exploration [14].

- Audit the Latent Space: If using a deep learning model, project its latent space and color the points by the date of publication. This may reveal entire regions corresponding to under-explored element combinations that the model has effectively ignored [13].

- Resolution:

- Data Augmentation: Use crystal structure prediction software to generate hypothetical, chemically plausible materials that fill the gaps in the historical data and add them to the training set.

- Reinforcement Learning: Guide the generative model with a reward function that explicitly penalizes the generation of materials that are too similar to historical data and rewards novelty and diversity [13].

- Incorporating Domain Knowledge: Integrate rules or constraints from quantum mechanics or crystal chemistry that allow for the exploration of spaces not well-supported by the existing data [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common root causes of anthropogenic bias in materials datasets? A1: The primary causes are:

- Non-Representative Sourcing: Over-reliance on easily accessible digital libraries and a few high-impact journals, leading to an over-representation of "popular" elements and research trends [13].

- Flawed Data Extraction: Errors introduced by automated systems that struggle with the multimodal nature of scientific literature (text, tables, images, schematics) and domain-specific notations [13].

- Historical Focus: A natural tendency to build upon past success, creating a "rich-get-richer" effect where well-studied material classes accumulate even more data, while potentially promising areas remain unexplored [13].

Q2: Are there established metrics to quantify the representativeness of a materials dataset? A2: While there is no single standard, researchers use several quantitative measures:

- Elemental Coverage: The percentage of possible elements (or combinations in a phase diagram) present in the dataset versus those considered chemically plausible.

- Synthesis Method Diversity: The entropy or variety of synthesis techniques (e.g., solid-state reaction, CVD, sol-gel) documented.

- Temporal Distribution: The distribution of publication years for the data points. A healthy dataset should have a significant portion of data from the last decade.

- Source Diversity: The number of unique journals, authors, and research institutions from which the data is sourced.

The table below summarizes key metrics for dataset assessment.

| Metric Name | Description | Target Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Elemental Coverage | Percentage of relevant periodic table covered. | High, aligned with research domain. |

| Publication Date Entropy | Measure of data distribution across time. | Balanced, with strong recent representation. |

| Source Concentration | Herfindahl index of data sources (journals, labs). | Low, indicating diverse origins [13]. |

| Data Type Completeness | Proportion of records with full structural, property, and synthesis data. | High, for multi-task learning. |

Q3: What experimental protocols can I use to validate data extracted from literature? A3: A robust validation protocol involves a multi-step process, which can be visualized in the following workflow. The corresponding experimental steps are detailed thereafter.

- Step 1: Manual Source Verification: A domain expert must directly compare the extracted value (e.g., a bandgap, a conductivity measurement) against the original PDF or HTML of the source publication. Document any discrepancies.

- Step 2: Plausibility and Range Checking: Programmatically check if the value lies within a physically possible range. For example, a negative formation energy for a stable compound is implausible and should be flagged.

- Step 3: Cross-Referencing with Trusted Databases: Compare the value against entries in high-quality, manually curated databases (e.g., the Materials Project for inorganic crystals, PubChem for molecules). Significant outliers require investigation [13].

- Step 4: Experimental Replication (For High-Impact Data): If the data point is critical to a fundamental conclusion or model, the ultimate validation is to replicate the synthesis and measurement in a lab, following the protocol described in the original source.

Q4: How can root cause analysis principles be applied to improve AI-driven materials discovery? A4: The RCA² (Root Cause Analysis and Action) framework, adapted from healthcare, is highly applicable [14].

- Shift from Model-Blame to System-Blame: When a model fails, instead of just tweaking the algorithm (symptom), investigate systemic issues like the quality, breadth, and representativeness of the training data (root cause) [14].

- Analyze "Near-Misses": Proactively examine cases where the AI suggested a promising material that ultimately failed in testing. Understanding why these near-misses failed can reveal biases in the training data or objective function [14].

- Focus on Sustainable Solutions: The action should not be a one-time data cleanup. It should involve implementing new, sustainable processes for continuous data curation, bias monitoring, and model auditing [14] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and their functions for building robust, bias-aware materials datasets.

| Reagent / Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Automated Literature Extraction Tools | Tools (e.g., based on Transformer models) that parse scientific PDFs to extract structured materials data (composition, synthesis, properties) from text and tables at scale [13]. |

| Bias Mitigation Algorithms | Software algorithms (e.g., re-sampling, adversarial debiasing) applied to datasets or models to reduce the influence of spurious correlations and historical biases [12]. |

| High-Throughput Computation | Using supercomputing resources to generate large volumes of consistent, high-quality ab initio data for underrepresented material classes, helping to balance empirical datasets [13]. |

| Crystal Structure Prediction Software | Tools that generate hypothetical, thermodynamically stable crystal structures, providing "synthetic" data points to fill voids in the known chemical space for model training [13]. |

| Materials Data Platform | A centralized, versioned database (e.g., based on Citrination, MPContribs) for storing, linking, and tracking the provenance of all experimental and computational data [13]. |

In the context of materials science and drug discovery, the principle of "bias in, bias out" is a critical concern [16]. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) models do not merely passively reflect the biases present in their training data; they actively amplify them, creating a ripple effect that can distort scientific outcomes and compromise research validity [17] [18]. This is particularly perilous in materials informatics, where historical datasets often suffer from anthropogenic biases—systematic inaccuracies introduced by human choices in data collection, such as over-representing certain classes of materials or synthetic pathways while neglecting others [19].

This amplification occurs primarily through a phenomenon known as shortcut learning [9]. Models tend to exploit the simplest possible correlations in the data to make predictions. If a dataset contains spurious correlations—for example, if a particular material property was consistently measured under a specific, non-essential experimental condition—the model will learn to rely on that correlation as a "shortcut." It then applies this learned shortcut aggressively to new data, thereby systematizing and amplifying what might have been a minor inconsistency into a major source of error [9]. Understanding and mitigating this ripple effect is essential for building reliable AI tools that can genuinely accelerate innovation in materials research and pharmaceutical development.

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My AI model achieves high overall accuracy on my materials dataset, but fails dramatically when applied to new, slightly different experimental data. What is the cause?

A1: This is a classic symptom of shortcut learning and a clear sign that your model has amplified initial biases in your training set [9]. The model likely learned features that are correlated with your target property in the specific context of your training data, but which are not causally related. For instance, the model might be keying in on a specific data source or a particular lab's measurement artifact rather than the fundamental material property. To diagnose this, employ the Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL) diagnostic paradigm [9]. This involves using a suite of models with different inductive biases to collaboratively identify the minimal set of shortcut features the model may be exploiting.

Q2: How can I check if my materials dataset has inherent biases before even training a model?

A2: A proactive approach is to conduct a bias audit [16] [20]. This involves:

- Metadata Analysis: Systematically analyzing the distribution of your dataset's metadata. Check for over-representation of certain material classes, synthesis methods, or characterization techniques.

- Statistical Disparity Tests: Applying statistical metrics to measure representation across different subgroups of your data [16].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Using explainable AI (xAI) techniques on simple models to see which features are most predictive. If features unrelated to the core material chemistry are highly weighted, it may indicate a bias [19].

Q3: I've identified a bias in my model. What are my options for mitigating it without recollecting all my data?

A3: Several bias mitigation algorithms can be applied during the ML pipeline [12]. Note that these involve trade-offs between social (fairness), environmental (computational cost), and economic (resource allocation) sustainability [12]. The main categories are:

- Pre-processing: These techniques adjust the training data itself to make it more balanced. This can include re-sampling (over-sampling underrepresented groups or under-sampling overrepresented ones) or re-weighting data points to balance their influence during training [20].

- In-processing: These algorithms are built into the learning objective, forcing the model to optimize for both accuracy and fairness simultaneously. This involves adding fairness constraints or adversarial debiasing to the model's loss function [9] [12].

- Post-processing: These methods adjust the model's outputs after training. For a regression task, this might involve calibrating predictions for different subgroups of materials to ensure consistent performance [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance is Biased Against Underrepresented Material Classes

| Observation | Potential Cause | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| High error for materials synthesized via sol-gel method (underrepresented). | Representation Bias: The training data has very few sol-gel examples. | Data Augmentation: Generate synthetic data for the sol-gel class using generative models or by applying realistic perturbations to existing data [19]. |

| Model consistently underestimates property for high-throughput data from one lab. | Measurement Bias: Systematic difference in data collection for one source. | Algorithmic Fairness: Apply in-processing mitigation techniques that incorporate data source as a protected attribute to learn invariant representations [12]. |

Problem: Model Learns Spurious Correlations

| Observation | Potential Cause | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Model performance drops if a specific data pre-processing step is changed. | Shortcut Learning: The model uses a pre-processing artifact as a predictive shortcut. | Causal Modeling: Shift from correlation-based models to causal graphs to identify and model the true underlying causal relationships [19]. |

| Model fails on data where a non-causal feature (e.g., sample ID) is randomized. | Confirmation Bias: The model has latched onto a feature that is a proxy for the real cause. | Feature Selection & XAI: Use rigorous feature selection and eXplainable AI (xAI) tools to identify and remove non-causal proxy features from the training set [21]. |

Quantitative Data on Bias and Mitigation

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from benchmarking studies, relevant to the evaluation of bias and the cost of mitigation in ML projects.

Table 1: Benchmarking AI Bias in Models [17]

| Bias Category | Example | Model/System | Quantitative Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racism/Gender | Gender classification | Commercial AI Systems | Error rates up to 34.7% higher for darker-skinned females vs. lighter-skinned males [21]. |

| Racism | Recidivism prediction | COMPAS System | Black defendants were ~2x more likely to be incorrectly flagged as high-risk compared to white defendants [18]. |

| Gender | Resume screening | University of Washington Study | AI model favored resumes with names associated with white males; Black male names never ranked first [17]. |

| Ageism | Automated hiring | iTutorGroup | AI software automatically rejected female applicants aged 55+ and male applicants 60+ [17]. |

Table 2: Impact of Bias Mitigation Algorithms on Model Sustainability [12] This study evaluated six mitigation algorithms across multiple models and datasets.

| Sustainability Dimension | Metric | Impact of Mitigation Algorithms |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Fairness Metrics (e.g., Demographic Parity) | Improved significantly, but the degree of improvement varied substantially between different algorithms and datasets. |

| Environmental | Computational Overhead & Energy Usage | Increased in most cases, indicating a trade-off between fairness and computational cost. |

| Economic | Resource Allocation & System Trust | Presents a complex trade-off; increased computational costs vs. potential gains from more robust and trustworthy models. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Identification and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Diagnosing Shortcuts with Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL)

This protocol is based on the SHL paradigm introduced in Nature Communications [9], adapted for a materials science context.

Objective: To unify shortcut representations in probability space and identify the minimal set of shortcut features (the "shortcut hull") that a model may be exploiting.

Materials & Workflow:

- Model Suite Preparation: Assemble a diverse suite of ML models with different inductive biases (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks, Transformers, Graph Neural Networks, linear models) [9].

- Data Representation: Formalize your materials dataset in a unified probability space. Let the sample space Ω represent all possible material specimens, with X as the input data (e.g., spectra, composition) and Y as the label (e.g., property).

- Collaborative Training: Train all models in the suite on the same dataset.

- SHL Diagnosis: Analyze the learning patterns and errors across the different models. Models will latch onto different shortcuts based on their architectural biases. By identifying the common failure modes and the features that different models disproportionately rely on, you can collaboratively learn the "shortcut hull" of your dataset.

- Validation: Develop a "shortcut-free" evaluation framework by creating a test set that explicitly controls for the identified shortcuts. A model's performance on this rigorous test set reveals its true capability, beyond shortcut learning.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the SHL diagnostic process:

Protocol 2: Implementing a Pre-processing Mitigation Strategy

Objective: To balance a training dataset to reduce representation bias against a specific class of materials.

Materials & Workflow:

- Bias Audit: Quantify the representation of different material classes or synthesis groups in your dataset using statistical analysis.

- Identify Underrepresented Groups: Define the specific subgroup(s) that have significantly fewer data points.

- Apply Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE): For each sample in the underrepresented group, generate synthetic examples by:

- Finding the k-nearest neighbors (e.g., k=5) from the same group.

- Taking a random linear interpolation between the original sample and one of its neighbors to create a new, synthetic data point.

- Validation: Train your model on the augmented, balanced dataset and evaluate its performance on a held-out test set, ensuring to measure performance per subgroup, not just overall accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for conducting rigorous bias-aware AI research in materials science.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Bias Analysis and Mitigation

| Tool / Solution | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Shortcut Hull Learning (SHL) Framework [9] | Diagnostic Paradigm | Unifies shortcut representations to empirically diagnose the true learning capacity of models beyond dataset biases. |

| Bias Mitigation Algorithms (e.g., Reweighting, Adversarial Debiasing) [12] | Software Algorithm | Actively reduces unfair bias in models during pre-, in-, or post-processing stages of the ML pipeline. |

| eXplainable AI (XAI) Tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) [19] | Interpretation Library | Provides post-hoc explanations for model predictions, helping researchers identify if models are using spurious correlations. |

| Synthetic Data Generators (e.g., GANs, VAEs) [19] | Data Augmentation Tool | Generates realistic, synthetic data for underrepresented classes to balance datasets and mitigate representation bias. |

| Fairness Metric Libraries (e.g., AIF360) [16] | Evaluation Metrics | Provides a standardized set of statistical metrics (e.g., demographic parity, equalized odds) to quantify model fairness. |

Visualizing the Bias Amplification and Mitigation Pipeline

The following diagram maps the complete lifecycle of bias, from its introduction in the data to its amplification by models and finally to its mitigation, illustrating the "ripple effect" and key intervention points.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bias Identification | Difficulty recognizing subtle "anthropogenic" (human-origin) biases in datasets. [22] | Limited framework for capturing social/cultural/historical factors ingrained in data. [22] | Use the Glossary's "Data Artifact" lens to reframe bias as an informative record of practices and inequities. [23] |

| Community Contribution | Uncertainty about how to contribute or update bias entries without coding expertise. [23] | Perception that the GitHub-based platform is only for developers. [23] | Use the user-friendly contribution form detailed in the "Data Artifacts Glossary Contribution Guide". [23] |

| Workflow Integration | Struggling to apply generic bias categories to specialized materials science data. [22] | General bias frameworks may not account for domain-specific issues like "activity cliffs". [13] | Pilot the Glossary with a specific dataset (e.g., text-mined synthesis recipes) to document field-specific artifacts. [23] [22] |

| Tool Limitations | Need to find biased subgroups without pre-defined protected attributes (e.g., race, gender). [24] | Many bias detection tools require knowing and specifying sensitive groups in advance. [24] | Employ unsupervised bias detection tools that use clustering to find performance deviations. [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core philosophy behind the "Data Artifact" concept? The Glossary treats biased data not just as a technical flaw to be fixed, but as an informative "artifact"—a record of societal values, historical healthcare practices, and ingrained inequities. [23] In materials science, this translates to viewing biased datasets as artifacts that reveal historical research priorities, cultural trends in scientific exploration, and exclusionary practices. [22] This approach helps researchers understand the root causes of data gaps and inequities, moving beyond simple mitigation. [23]

Q2: Our materials dataset suffers from a lack of "variety"—it's dominated by specific classes of compounds. How can the Glossary help? The Glossary provides a structured way to document and catalog this specific type of bias, known as "representation bias". [21] By creating an entry for your dataset, you can detail which material classes are over- or under-represented. This formalizes the dataset's limitations, warning future users and guiding them to supplement it with other data sources. This is a crucial first step in overcoming the "anthropogenic bias" of how chemists have historically explored materials. [22]

Q3: What is the process for adding a new bias entry or suggesting a change? The process is modeled on successful open-source projects: [23]

- Proposal: Community members submit a "pull request" on GitHub or use a provided form for non-technical contributions. [23]

- Review: The proposal undergoes a public, peer-review process managed by project maintainers and experts. [23]

- Integration: Once approved, the contribution is merged into the living Glossary, ensuring it remains dynamic and up-to-date. [23]

Q4: How can I detect bias if I don't have demographic data for my materials science datasets? You can use unsupervised bias detection tools. These tools work by clustering your data and then looking for significant deviations in a chosen performance metric (the "bias variable," like error rate) across the different clusters. This method can reveal unfairly treated subgroups without needing pre-defined protected attributes like gender or ethnicity. [24]

Q5: Are there trade-offs to using bias mitigation algorithms? Yes, applying bias mitigation algorithms can involve complex trade-offs. A 2025 benchmark study showed that these techniques affect more than just fairness (social sustainability). They can also alter the model's computational overhead and energy usage (environmental sustainability) and impact resource allocation or consumer trust (economic sustainability). Practitioners should evaluate these dimensions when designing their ML solutions. [12]

Experimental Protocols for Key Tasks

Protocol 1: Documenting a Data Artifact in a Materials Dataset

This protocol guides you through characterizing and submitting a bias entry for a materials dataset to the Data Artifacts Glossary. [23]

- Objective: To formally identify, analyze, and document an anthropogenic bias in a materials dataset as a community resource.

- Materials: The target dataset (e.g., text-mined synthesis recipes [22]), metadata, and documentation.

- Procedure:

- Dataset Profiling: Conduct a comprehensive analysis of your dataset's composition. For a synthesis dataset, this includes quantifying the distribution of target elements, precursors, and synthesis parameters. [22]

- Bias Identification: Contrast your dataset's profile against a desired "ideal" distribution. Identify gaps, such as over-representation of oxide materials or solid-state synthesis methods, and under-representation of other classes or techniques. [22]

- Artifact Characterization: Frame the identified bias as a data artifact. Describe its nature (e.g., "historical preference for oxide ceramics"), its potential impact (e.g., "limits predictive models for novel sulfides"), and its likely anthropogenic origin (e.g., "reflects past laboratory equipment availability and research funding trends"). [23] [22]

- Glossary Entry Drafting: Use the standard template from the Data Artifacts Glossary to draft a new entry. Include sections for artifact name, description, dataset, impact, and potential mitigation strategies. [23]

- Community Submission: Submit your draft entry via the official GitHub repository or the user-friendly contribution form for peer review. [23]

The workflow for this documentation process is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Unsupervised Detection of Performance Bias Subgroups

This methodology uses clustering to find data subgroups where an AI model performs significantly differently, which can indicate underlying bias, without needing protected labels. [24]

- Objective: To algorithmically identify clusters within a dataset where a chosen performance metric (bias variable) deviates significantly from the rest of the data.

- Materials: A tabular dataset of model inputs/predictions, a defined "bias variable" (e.g., prediction error, accuracy).

- Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Prepare a tabular dataset. Handle missing values and ensure all features (except the bias variable) are either all numerical or all categorical. Select a categorical column to serve as the

bias variable. [24] - Parameter Configuration: Set hyperparameters:

Iterations(number of data splits, default=3),Minimal cluster size(e.g., 1% of rows), andBias variable interpretation(e.g., "Lower is better" for error rate). [24] - Train-Test Split: Split the dataset into training (80%) and test (20%) subsets. [24]

- Hierarchical Bias-Aware Clustering (HBAC): Apply the HBAC algorithm to the training set. It iteratively splits the data to find clusters with low internal variation but high external variation in the bias variable. Save the cluster centroids. [24]

- Statistical Testing: On the test set, use a one-sided Z-test to check if the bias variable in the most deviating cluster is significantly different from the rest of the data. If significant, examine feature differences with t-tests (numerical) or χ²-tests (categorical). [24]

- Expert Interpretation: The tool's output serves as a starting point for human experts to assess the real-world relevance and fairness implications of the identified cluster. [24]

- Data Preparation: Prepare a tabular dataset. Handle missing values and ensure all features (except the bias variable) are either all numerical or all categorical. Select a categorical column to serve as the

The technical workflow for this unsupervised detection is as follows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Tool / Resource | Function & Explanation | Relevance to Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Artifacts Glossary [23] | A dynamic, open-source repository for documenting biases ("artifacts") in datasets. | Core Framework: Provides the standardized methodology and platform for cataloging and sharing knowledge about dataset limitations. |

| GitHub Platform [23] | Hosts the Glossary, enabling version control and collaborative contributions via "pull requests". | Community Engine: Facilitates the transparent, community-driven peer review and updating process that keeps the Glossary current. |

| Unsupervised Bias Detection Tool [24] | An algorithm that finds performance deviations by clustering data without using protected attributes. | Discovery Tool: Helps identify potential biased subgroups in complex datasets where sensitive categories are unknown or not recorded. |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Databases [22] | Large datasets of materials synthesis recipes extracted from scientific literature using NLP. | Primary Data Source: Serves as a key example of a dataset containing anthropogenic bias, reflecting historical research choices. [22] |

| Bias Mitigation Algorithms [12] | Techniques applied to training data or models to reduce unfair outcomes. | Intervention Mechanism: Directly addresses identified biases but requires careful evaluation of social, economic, and environmental trade-offs. [12] |

A Bias Mitigation Toolkit: From Data Curation to Foundational Models

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Fusion Conflicts from Sensor Heterogeneity

Problem: Inconsistent data formats, sampling rates, and physical units from disparate IoT sensors and online sources create fusion artifacts that introduce structural biases into the analysis pipeline [25].

Solution:

Step 1: Implement Spatiotemporal Alignment

- Protocol: Use the CREST platform's dynamic time-warping module to align all sensor data streams to a unified timestamp. Manually set the reference clock to the most reliable sensor source (e.g., atomic clock time server).

- Expected Output: All data points across modalities share a synchronized timestamp with ≤1ms precision.

Step 2: Apply Adaptive Normalization

- Protocol: Execute the

normalize --mode=adaptivecommand. This automatically detects value ranges for each sensor type and applies min-max scaling or Z-score normalization based on data distribution profiles. - Verification: Check the post-normalization summary report. Confirm all value distributions now fall within the -1.0 to +1.0 range.

- Protocol: Execute the

Step 3: Validate with Cross-Correlation

- Protocol: Run the

validate --method=crosscorrtool. This calculates pairwise correlations between all processed data streams to identify residual inconsistencies. - Success Criteria: All inter-sensor correlation coefficients must be ≥0.85. Values below this indicate persistent alignment issues requiring reprocessing.

- Protocol: Run the

Guide 2: Correcting Algorithmic Bias in Threat Detection Models

Problem: Machine learning models for threat assessment show higher false-positive rates for specific demographic patterns, indicating embedded anthropological bias from training data [25].

Solution:

Step 1: Activate Bias Audit Mode

- Protocol: In the CREST dashboard, navigate to

Admin > Threat Models > Audit. Select "Comprehensive Bias Scan" and run against the last 30 days of operational data. - Output: The system generates a bias heatmap report highlighting demographic variables with disproportionate flagging rates.

- Protocol: In the CREST dashboard, navigate to

Step 2: Apply De-biasing Recalibration

- Protocol: For each variable showing bias >15%, execute

recalibrate --variable=<VAR> --sensitivity=reduce. Repeat for all identified variables. - Critical Setting: Ensure

--preserve-precision=yesis active to maintain overall detection accuracy while reducing demographic disparities.

- Protocol: For each variable showing bias >15%, execute

Step 3: Validate with Holdout Dataset

- Protocol: Test the recalibrated model against the curated unbiased validation dataset (included with CREST installation).

- Success Metrics: False-positive rate disparity between demographic groups must be <5% while overall model precision remains ≥90%.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does the "Data Stream Integrity" warning light indicate, and how should I respond?

- Red Flashing: Indicates a critical failure in one or more data streams. Immediately check the

System Status > Data Healthdashboard to identify the affected sensor or source. The system will automatically queue missing data for backfill once connectivity is restored [26]. - Yellow Steady: Indicates degraded but functional data quality. Run the

diagnostic --data-qualitytool to identify specific sensors with compromised precision or increased noise floors [26].

Q2: How do I handle blockchain validation errors when exchanging digital evidence with partner institutions?

- Procedure: First, verify chain-of-custody logs using the

evidence --verify --allcommand. If errors persist, initiate a cross-institutional validation handshake withblockchain --sync --force. This re-establishes cryptographic consensus without compromising evidence integrity [25]. - Contingency: If handshake fails, contact the CREST administrative team for emergency consensus resolution via the 24/7 support line [26].

Q3: Why does my autonomous surveillance drone show erratic navigation during multi-target tracking scenarios?

- Primary Cause: This typically indicates a "target confusion" feedback loop where the navigation system receives conflicting optimal path data from multiple simultaneous tracking operations [25].

- Resolution: Press and hold the

Site Select/Affiliationbutton until you hear a second confirmation tone. This forces the system to re-affiliate to the primary mission channel and clear conflicting navigation queues [26].

Q4: How can I verify that my multimodal dataset has sufficient variety to mitigate anthropogenic bias?

- Validation Protocol: Use the CREST

bias --detect --modality=allcommand-line tool. It will analyze data distribution across all modalities and generate a Variety Sufficiency Score (VSS). - Acceptance Threshold: A VSS ≥0.75 indicates sufficient data diversity. Scores below 0.6 require additional data collection from underrepresented scenarios or sensor types before proceeding with analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Bias Mitigation

Protocol 1: Anthropogenic Bias Quantification in Multi-Source Datasets

Objective: To systematically measure and quantify human-induced sampling biases present across heterogeneous data modalities [25].

Materials:

- CREST Data Fusion Workstation

- Reference Bias-Calibrated Dataset (RBCD)

- High-Performance Computing Cluster

Procedure:

Data Ingestion: Load all raw multimodal data streams (sensor feeds, online content, operational records) into the CREST platform using the

import --raw --preserve-origincommand.Modality Tagging: Execute

tag --modality --auto-classifyto automatically label each data element with its modality type (e.g.,thermal_video,acoustic,text_online,motion_sensor).Bias Baseline Establishment: Load the RBCD and run

analyze --bias --reference=RBCDto establish a bias-neutral benchmark for comparison.Divergence Measurement: Calculate the Kullback-Leibler divergence between your dataset's distributions and the RBCD using

statistics --divergence --modality=all.Report Generation: Execute

report --bias --format=detailedto produce the comprehensive bias quantification report.

Table 1: Maximum Tolerable Bias Divergence Thresholds by Data Type

| Data Modality | Statistical Metric | Threshold Value |

|---|---|---|

| Visual/Image Data | KL Divergence | ≤ 0.15 |

| Text/Linguistic Data | Jensen-Shannon Distance | ≤ 0.08 |

| Sensor Telemetry | Population Stability Index | ≤ 0.10 |

| Temporal/Sequence | Earth Mover's Distance | ≤ 0.12 |

Protocol 2: Cross-Modal Validation for Artifact Detection

Objective: To identify and flag analytical artifacts that result from the fusion of incompatible data modalities rather than genuine phenomena [25].

Materials:

- CREST Cross-Modal Validation Module

- Minimum of 3 independent data modalities

Procedure:

Independent Analysis: Run the primary detection algorithm (e.g., threat assessment) separately on each individual data modality. Record all detections and confidence scores.

Fused Analysis: Execute the same detection algorithm on the fully fused multimodal dataset.

Consistency Checking: Run

validate --cross-modal --threshold=0.85to identify detection events that appear in the fused data but are absent in ≥2 individual modality analyses.Artifact Flagging: All events failing the consistency check are automatically flagged as potential fusion artifacts in the final report.

Table 2: Cross-Modal Validation Reference Standards

| Validation Scenario | Required Modality Agreement | Artifact Confidence Score |

|---|---|---|

| Threat Detection in Crowded Areas [25] | 3 of 4 modalities | ≥ 0.92 |

| Firearms Trafficking Pattern Recognition [25] | 2 of 3 modalities | ≥ 0.87 |

| Public Figure Protection Motorcades [25] | 4 of 5 modalities | ≥ 0.95 |

Visualization Workflows

Diagram 1: CREST Multimodal Data Fusion Workflow

Diagram 2: Anthropogenic Bias Detection Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multimodal Data Integration

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Spatiotemporal Alignment Engine | Synchronizes timestamps and geographic coordinates across all data modalities | CREST Dynamic Time-Warping Module [25] |

| Cross-Modal Validation Suite | Detects and flags analytical artifacts from data fusion | CREST validate --cross-modal command |

| Blockchain Evidence Ledger | Maintains chain-of-custody for shared digital evidence | Distributed ledger integrated in CREST platform [25] |

| Bias-Reference Calibrated Dataset | Provides neutral benchmark for quantifying anthropogenic bias | RBCD v2.1 (included with CREST installation) |

| Adaptive Normalization Library | Standardizes value ranges across heterogeneous sensor data | CREST normalize --mode=adaptive algorithm |

| Autonomous System Navigation Controller | Provides dynamic mission planning and adaptive navigation | CREST drone/UGV control module [25] |

Leveraging Foundation Models and Self-Supervised Learning for Richer Representations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary scenarios where self-supervised learning (SSL) provides a significant performance boost over supervised learning?

A1: Empirical studies indicate that SSL excels in specific scenarios, primarily those involving transfer learning. Performance gains are most pronounced when:

- Pre-training on Large Auxiliary Datasets: A model is first pre-trained via SSL on a large, diverse, and unlabeled dataset and then fine-tuned on a smaller, task-specific target dataset. For example, in single-cell genomics, SSL pre-training on a dataset of over 20 million cells significantly improved cell-type prediction on smaller, unseen datasets [27].

- Analyzing Unseen or Novel Datasets: SSL models demonstrate stronger generalization capabilities for analyzing new datasets that were not part of the original training corpus, as they learn more robust fundamental representations [27].

- Handling Class Imbalance: SSL pre-training has been shown to particularly improve the identification of underrepresented classes, as indicated by greater improvements in macro F1 scores compared to micro F1 scores in classification tasks [27].

Q2: For foundation models applied to scientific data, what are the key considerations for choosing a self-supervised pre-training strategy?

A2: The optimal SSL strategy can depend on the data domain. Key considerations and findings include:

- Masked Autoencoders vs. Contrastive Learning: In single-cell genomics, masked autoencoders have been empirically shown to outperform contrastive learning methods, a trend that diverges from some computer vision applications [27]. The masking strategy (e.g., random vs. biologically-informed gene-programme masking) is an active area of research [27].

- Data Modality and Augmentation: The choice of pretext task and data augmentation must be tailored to the data type. For instance, in computational pathology, multi-scale learning across different magnifications is critical [28], while in analog circuit design, random patch sampling and masking of layout patterns are effective [29].

- Objective: Masked modeling excels at dense prediction tasks and data reconstruction, while contrastive learning often produces better representations for classification and similarity tasks [27] [30].

Q3: Our in-house materials science dataset is limited and may contain anthropogenic bias. How can foundation models help?

A3: Foundation models, pre-trained with SSL on large, diverse datasets, are a powerful tool to mitigate these issues.

- Reducing Reliance on Small, Biased Datasets: By fine-tuning a foundation model pre-trained on a broad corpus (e.g., millions of material structures or chemical compounds), you can achieve high performance on your specific task with a much smaller amount of labeled data. This reduces the influence of biases in your smaller dataset [29] [31].

- Learning Robust, General Representations: SSL forces the model to learn the underlying data structure without human-provided labels, which can help it ignore spurious, human-introduced correlations (anthropogenic biases) and focus on more fundamental patterns [32] [30].

- Data Efficiency: Fine-tuning a foundation model requires significantly less task-specific data to achieve a target performance level. For example, in analog layout design, fine-tuning a foundation model required only 1/8 of the data to achieve the same performance as training a model from scratch [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Downstream Task Performance After SSL Pre-training

Problem: After spending significant resources on self-supervised pre-training, the model shows little to no improvement when fine-tuned on your target task.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Distribution Mismatch | Analyze the feature distribution (e.g., using PCA) between your pre-training data and target data. | Ensure your pre-training corpus is relevant and diverse enough to cover the variations present in your downstream task. Incorporate domain-specific data during pre-training [31]. |

| Ineffective Pretext Task | Evaluate the model's performance on a "zero-shot" task or via linear probing on a validation set before fine-tuning. | Re-evaluate your SSL objective. For reconstruction-heavy tasks, masked autoencoding may be superior. For discrimination tasks, contrastive or self-distillation methods (e.g., DINO, BYOL) might be better [28] [27]. |

| Catastrophic Forgetting During Fine-Tuning | Monitor loss on both the new task and a held-out set from the pre-training domain during fine-tuning. | Employ continual learning techniques or a more conservative fine-tuning learning rate. Paradigms like "Nested Learning" can also help mitigate this by treating the model as interconnected optimization problems [33]. |

Issue 2: Model Perpetuates or Amplifies Biases in the Data

Problem: The model's predictions reflect or even amplify societal or data collection biases, such as favoring certain material compositions over others without a scientific basis.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent Bias in Pre-training Data | Use explainable AI (XAI) techniques to understand which features the model is relying on for predictions. | Curate and Audit Training Data: Implement rigorous filtering and balancing of the pre-training dataset to reduce over-representation of certain groups [32]. |

| Algorithmic Bias | Conduct bias audits using counterfactual fairness tests (e.g., would the prediction change if a protected attribute were different?) [32]. | Apply Debiasing Techniques: Techniques include adversarial debiasing, which penalizes the model for learning protected attributes, or using fairness constraints during training [32]. |

| Lack of Transparency | The model's decision-making process is a "black box." | Integrate explainability frameworks by design. Use model introspection tools to identify which input features are most influential for a given output [32]. |

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Quantitative Effectiveness of SSL in Scientific Domains

The following table summarizes empirical results from recent research, highlighting the performance gains achievable with SSL and foundation models.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Self-Supervised Learning in Scientific Applications

| Domain | Task | Model / Approach | Key Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Genomics | Cell-type prediction on PBMC dataset | SSL Pre-training on scTab data (~20M cells) | Macro F1 improved from 0.7013 to 0.7466 [27] | Nature Machine Intelligence (2025) |

| Single-Cell Genomics | Cell-type prediction on Tabula Sapiens Atlas | SSL Pre-training on scTab data (~20M cells) | Macro F1 improved from 0.2722 to 0.3085 [27] | Nature Machine Intelligence (2025) |

| Analog Layout Design | Metal Routing Generation | Fine-tuned Foundation Model vs. Training from Scratch | Achieved same performance with 1/8 the task-specific data [29] | arXiv (2025) |

| Computational Pathology | Pre-training for Diagnostic Tasks | SLC-PFM Competition (MSK-SLCPFM dataset) | Pre-training on ~300M images from 39 cancer types for 23 downstream tasks [28] | NeurIPS Competition (2025) |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking SSL for a New Materials Dataset

This protocol provides a methodology for evaluating the effectiveness of SSL for a custom materials science dataset.

Objective: To determine if SSL pre-training on a large, unlabeled corpus of material structures improves prediction accuracy for a specific property (e.g., catalytic activity) on a small, labeled dataset.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Unlabeled Material Database (e.g., from materials projects) | A large, diverse corpus of material structures for self-supervised pre-training. Serves as the foundation for learning general representations. |

| Labeled Target Dataset | A smaller, task-specific dataset with the property of interest (e.g., bandgap, strength) for supervised fine-tuning and evaluation. |

| Deep Learning Framework (e.g., PyTorch, JAX) | Provides the software environment for implementing and training neural network models. |

| SSL Library (e.g., VISSL, Transformers) | Offers pre-built implementations of SSL algorithms like Masked Autoencoders (MAE) and Contrastive Learning (SimCLR, BYOL). |

| Experiment Tracker (e.g., Neptune.ai) | Tracks training metrics, hyperparameters, and model versions, which is crucial for reproducibility in complex foundation model training [31]. |

Methodology:

Data Preparation:

- Pre-training Corpus: Assemble a large set of material structures (e.g., CIF files). Apply domain-specific augmentations (e.g., random atom substitutions, coordinate perturbations).

- Target Dataset: Split your labeled dataset into training, validation, and test sets, ensuring no data leakage.

Self-Supervised Pre-training:

Supervised Fine-tuning:

- Take the pre-trained model and replace the pre-training head (e.g., the decoder) with a task-specific prediction head.

- Fine-tune the entire model on the labeled training split of your target dataset using a supervised loss function. Use a lower learning rate than during pre-training.

Evaluation and Comparison:

- Evaluate the fine-tuned model on the held-out test set.

- Compare its performance against:

- Baseline A: A model with the same architecture trained from scratch on the labeled target data.

- Baseline B: A model pre-trained in a purely supervised manner on a different, large labeled dataset (if available).

Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the core experimental protocol for leveraging a foundation model.

Core SSL Concepts and Workflows

A. Self-Supervised Learning Pretext Tasks

The following diagram illustrates two common SSL pretext tasks used to train foundation models without labeled data.

B. Mitigating Bias in Foundation Models

A critical part of deploying foundation models in research is ensuring they do not perpetuate biases. The following chart outlines a proactive workflow for bias mitigation.

In the field of materials science and drug development, the presence of anthropogenic bias—systematic skews introduced by human-driven data collection and labeling processes—can severely undermine the validity and fairness of AI models. Such biases in datasets lead to models that perform well only for majority or over-represented materials or compounds while failing to generalize. This guide details advanced algorithmic pre-processing techniques, specifically reweighing and relabeling, to mitigate these biases at the data level, ensuring more robust and equitable computational research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Answer: This is a classic symptom of a skewed dataset, where the distribution of classes (e.g., types of polymers or crystal structures) is highly imbalanced. The model optimizes for the majority classes, a phenomenon often leading to misleadingly high accuracy while performance on the "tail" or minority classes is poor [34] [35]. In such cases, traditional accuracy is a flawed metric.

Solution:

- Use Robust Metrics: Immediately switch to evaluation metrics that are sensitive to class imbalance.

- Diagnose with a Table: Compare the performance of your model using the following metrics side-by-side for a clear picture [35]:

| Metric | Focus | Why It's Better for Imbalanced Data |

|---|---|---|

| F1 Score | Balance of Precision & Recall | Harmonic mean provides a single score that balances the trade-off between false positives and false negatives. |

| ROC-AUC | Model's Ranking Capability | Measures the ability to distinguish between classes across all thresholds; can be optimistic for severe imbalance [35]. |

| PR-AUC (Precision-Recall AUC) | Performance on the Positive (Minority) Class | Focuses directly on the minority class, making it highly reliable for imbalanced datasets [35]. |

| Balanced Accuracy | Average Recall per Class | Averages the recall obtained on each class, preventing bias from the majority class. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | All Confusion Matrix Categories | A balanced measure that is robust even for imbalanced datasets [35]. |

FAQ 2: My dataset contains both continuous and categorical features (e.g., chemical properties and solvent types). Which resampling technique should I use?

Answer: Standard synthetic oversampling techniques like SMOTE are designed for continuous feature spaces and can perform poorly or generate meaningless synthetic data when categorical variables are present [36]. Applying them directly to mixed data is a common pitfall.

Solution:

- For datasets with all-categorical or mixed features, the Relabeling & Raking (R&R) algorithm is a robust alternative [36].

- Experimental Protocol for R&R:

- Bootstrap Sampling: Generate multiple bootstrap samples (samples with replacement) from the original dataset.

- Raking (Calibration): Adjust the weights of the majority class samples in these bootstrap samples using raking, a calibration technique from survey statistics, to better match known population totals or to create a more balanced representation.

- Relabeling: Strategically relabel a selection of the calibrated majority class instances to the minority class, effectively creating new, plausible minority samples without generating synthetic data.

- Model Training: Train your classifier on the final, balanced dataset created by combining the original minority samples with the newly relabeled samples [36].

The workflow for the R&R algorithm is as follows:

FAQ 3: How can I address data imbalance for a regression problem (e.g., predicting material properties)?

Answer: Unlike classification, the continuous nature of regression targets makes classic class-frequency-based rebalancing inapplicable [37]. Bias in regression often manifests as uneven feature space coverage or skewed error distributions across different value ranges.

Solution: Employ a loss re-weighting scheme that quantifies the value of each data sample based on its regional characteristics in the feature space [37].

- Methodology (ViLoss):

- Partition Feature Space: Discretize the continuous feature space into a hypergrid of cells.

- Calculate Sample Value Metrics:

- Uniqueness: Measures how sparsely populated a sample's local region (cell) is. Samples in sparse regions are more valuable for learning.

- Abnormality: Measures how much a sample's target value deviates from its neighbors. High-abnormality samples may be outliers.

- Assign Sample Weights: Fuse these metrics to assign a higher weight to samples with high uniqueness and low abnormality. This directs the model's focus to underrepresented yet reliable regions of the feature space [37].

- Static Pre-computation: These weights are computed once before training, minimizing computational overhead.

This feature-space balancing can be visualized as follows:

Answer: This is a Multi-Domain Long-Tailed (MDLT) problem, where you face a combination of within-domain class imbalance and across-domain distribution shifts [34]. Simply pooling the data can exacerbate biases.

Solution: Implement a Reweighting Balanced Representation Learning (BRL) framework. This approach combines several techniques [34]:

- Covariate Balancing (CB): Adjusts for imbalances in the input feature space across domains.

- Representation Balancing (RB): Learns a domain-invariant feature representation in the latent space, making the model robust to domain-specific biases.

- Class Balancing: Integrates reweighting to handle the long-tailed class distribution within domains.

By simultaneously applying these techniques, BRL works to extract domain- and class-unbiased feature representations, which is crucial for generalizing findings across different experimental setups [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key algorithmic "reagents" for de-biasing skewed datasets in materials and drug discovery research.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|