Optimizing Precursor Selection for Target Materials: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Discovery

Selecting optimal precursors is a critical, multi-faceted challenge in the synthesis of both inorganic materials and pharmaceutical compounds.

Optimizing Precursor Selection for Target Materials: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

Selecting optimal precursors is a critical, multi-faceted challenge in the synthesis of both inorganic materials and pharmaceutical compounds. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, synthesizing the latest advancements in the field. We explore the foundational principles of precursor selection, detail cutting-edge data-driven and thermodynamic methodological approaches, and present robust strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing synthesis pathways. The discussion is anchored by real-world case studies and comparative analyses of validation techniques, highlighting how integrating domain knowledge with machine learning and high-throughput experimentation is accelerating the discovery and manufacture of novel target materials.

The Critical Role of Precursors: Defining the Problem Space in Materials and Drug Synthesis

Precursor selection is a critical, foundational step in the synthesis of advanced materials and pharmaceuticals. The choice of starting materials directly dictates the success of a reaction, influencing the yield and purity of the target product, and steering the reaction pathways that lead to its formation. A poor choice can lead to stubborn impurity phases, low yields, or complete synthesis failure, creating significant bottlenecks in research and development [1] [2]. This technical resource center is designed to help researchers troubleshoot common synthesis challenges and implement advanced strategies for selecting optimal precursors, thereby accelerating the discovery and manufacture of new materials.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Precursor-Related Issues

This section addresses frequent challenges encountered during synthesis, providing targeted questions to diagnose issues and data-driven solutions.

FAQ 1: My synthesis consistently results in low yields of the target material, with multiple impurity phases. How can my precursor choice be the cause?

- Diagnostic Questions:

- Have you mapped the potential pairwise reactions between your chosen precursors?

- Are the precursors you selected known to form highly stable intermediate compounds?

- Explanation: Low yields often occur when precursor combinations react to form stable, unwanted intermediate phases in early reaction steps. These intermediates consume reactants and reduce the thermodynamic driving force available to form the final target material [1] [2].

- Solution: Implement a precursor selection strategy that actively avoids precursors known to form these stable intermediates. Research demonstrates that using new selection criteria focused on analyzing pairwise precursor reactions can significantly improve outcomes. In one study, this approach successfully increased phase purity for 32 out of 35 target materials synthesized [1]. The ARROWS3 algorithm, which uses thermodynamic data to rank precursors and then learns from experimental failures to avoid such intermediates, has proven effective in identifying optimal precursor sets with fewer experimental iterations [2].

FAQ 2: I am trying to synthesize a novel, metastable material. Why do my reactions keep resulting in the thermodynamically stable phase instead?

- Diagnostic Questions:

- Does your synthesis pathway involve high-temperature steps that favor thermodynamic products?

- Have you considered precursors that react at lower temperatures or through different kinetic pathways?

- Explanation: Metastable materials are often synthesized using low-temperature routes where kinetic control can prevent the formation of more stable, equilibrium phases [2]. Conventional solid-state synthesis at high temperatures often drives reactions toward the most thermodynamically stable products.

- Solution: Explore precursor systems designed for low-temperature decomposition or alternative synthesis methods like Metal-Organic Chemical Vapour Deposition (MOCVD). For example, novel precursor chemistries, such as specific thiocarbamato complexes or adducts like the triethylamine adduct of dimethylzinc, have been developed to enable the deposition of materials that are problematic to synthesize with conventional precursors [3]. The goal is to find precursors that provide a kinetic pathway to your target, bypassing the stable phases.

FAQ 3: My synthesis results are inconsistent between batches. What precursor-related factors should I investigate?

- Diagnostic Questions:

- Are you sourcing precursors from different suppliers with potentially varying impurity profiles?

- Is the particle size or morphology of your precursor powders consistent?

- Explanation: Inconsistency often stems from variability in precursor properties, including purity, particle size, and crystalline form. Fluctuations in impurity levels during purification can significantly impact downstream processes and final product quality [4].

- Solution:

- Standardize Sources: Establish strict quality control protocols and source precursors from consistent, reputable suppliers.

- Implement Control Systems: Utilize integrated hardware and software platforms, including Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) and sensors for real-time condition monitoring, to ensure consistency, reduce human error, and maintain traceability across batches [4].

Table 1: Summary of Precursor-Related Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low yield & high impurities | Formation of stable intermediate phases | Use selection criteria that avoid unfavorable pairwise reactions [1] |

| Failure to form metastable target | Reaction pathway favors thermodynamic products | Employ low-temperature kinetic routes & novel precursor chemistries [3] [2] |

| Inconsistent batch-to-batch results | Variable precursor purity or physical properties | Standardize precursor sources and implement quality control/automation systems [4] |

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Optimal Precursor Selection

The following methodologies outline modern, data-driven approaches to precursor selection, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error.

Protocol 1: The ARROWS3 Algorithm for Autonomous Precursor Selection

This protocol uses thermodynamic data and active learning to iteratively identify the best precursors for a target material [2].

- Input Target and Generate Options: Specify the desired material's composition and structure. The algorithm generates a list of all possible precursor sets that can be stoichiometrically balanced to yield the target.

- Initial Thermodynamic Ranking: In the absence of prior experimental data, the algorithm ranks these precursor sets based on their calculated thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target. Precursors with the largest (most negative) ΔG are prioritized initially [2].

- Experimental Testing & Pathway Analysis: The top-ranked precursor sets are tested experimentally at a range of temperatures. Techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) with machine-learned analysis are used to identify the crystalline intermediates formed at each step [2].

- Algorithm Learning & Re-Ranking: When experiments fail, the algorithm learns which pairwise reactions led to the formation of energy-consuming intermediates. It then updates its ranking to favor precursor sets that are predicted to avoid these intermediates, thereby retaining a larger thermodynamic driving force (ΔG′) for the final target-forming step [2].

- Iteration: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated until the target is synthesized with high purity or all options are exhausted.

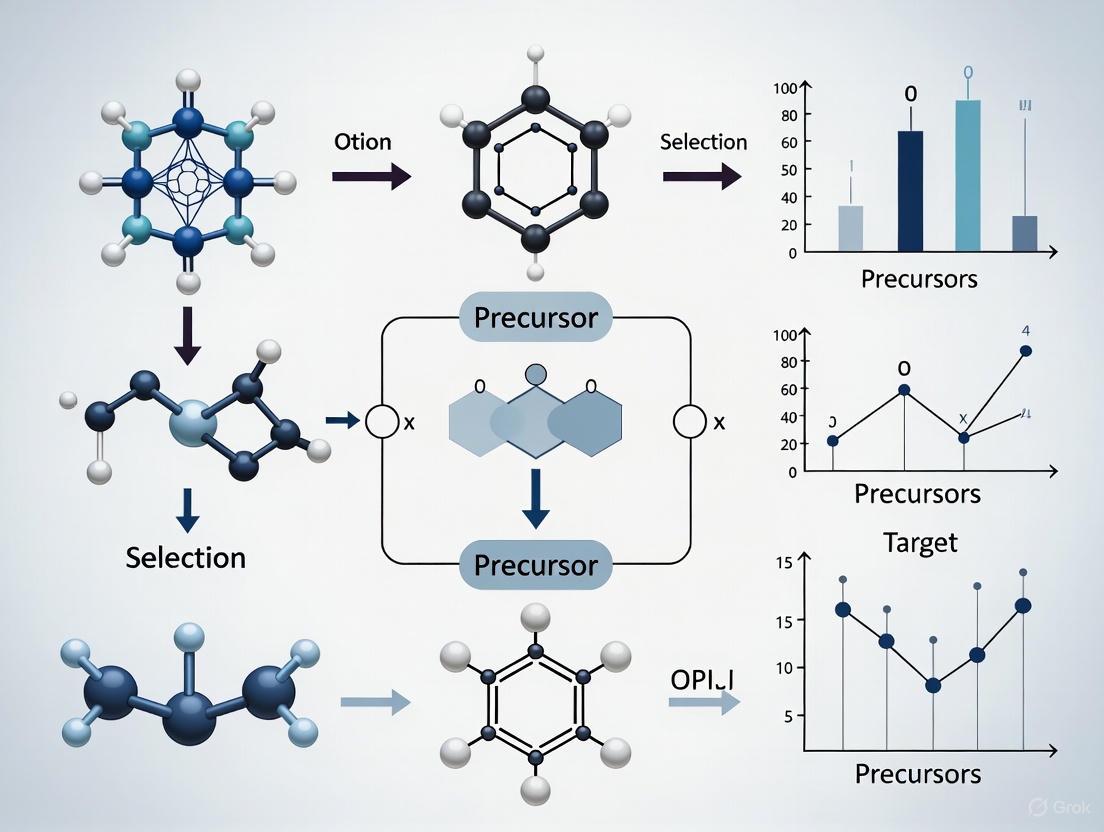

The diagram below illustrates this iterative, closed-loop workflow:

Protocol 2: Data-Driven Precursor Recommendation from Literature Knowledge

This strategy leverages large historical datasets to recommend precursors for a novel target, mimicking how a human researcher would consult the literature [5].

- Knowledge Base Construction: A large database of synthesis recipes (e.g., 29,900 recipes text-mined from scientific literature) is used as a knowledge base [5].

- Material Encoding: An encoding neural network learns to represent a target material as a numerical vector based on its composition and, crucially, the precursors typically used to synthesize it. This model is trained to predict masked precursors from a set, capturing the dependencies between different precursors in the same experiment [5].

- Similarity Query: For a new target material, the algorithm computes its encoded vector and queries the knowledge base to find the most similar material for which a synthesis recipe is already known.

- Recipe Completion & Recommendation: The precursor set from the similar "reference" material is proposed. The algorithm may also add missing precursors if the reference set does not contain all required elements, based on conditional predictions. This approach has achieved a success rate of over 82% in historical validation tests [5].

The logical flow of this data-driven recommendation system is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details essential components in a modern precursor selection and synthesis workflow.

Table 2: Essential Tools for Advanced Precursor Selection and Synthesis

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Role in Precursor Selection |

|---|---|

| Robotic Synthesis Lab | Automates and parallelizes synthesis experiments, enabling high-throughput testing of hundreds of precursor combinations and conditions in weeks instead of years [1]. |

| Precursor Selector Encoding | A machine learning model that represents materials as vectors based on synthesis context, enabling data-driven similarity searches and precursor recommendations [5]. |

| Statistical Design of Experiments (DOE) | Systematically correlates synthesis parameters with material properties, replacing trial-and-error with structured optimization [6]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Tracks raw materials, process parameters, and product specifications, ensuring data integrity and traceability for troubleshooting [4]. |

| In Situ Characterization | Techniques like in-situ XRD provide real-time "snapshots" of reaction pathways, identifying intermediates for algorithm learning [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How can I prevent the formation of unwanted intermediates and impurity phases during precursor synthesis?

Root Cause Analysis: The formation of unwanted intermediates and impurity phases often originates from impurities in starting materials, non-optimal reaction kinetics, or inadequate control over processing conditions. Even high-purity commercial precursors can contain trace impurities that significantly alter final material performance [7].

Solutions and Verification Methods:

- Implement Advanced Purification: Techniques like Single Crystal Purification, specifically Solvent Orthogonality Induced Crystallization (SONIC), can remove a broad set of extrinsic impurities from commercial precursors. This method has been shown to improve phase purity and stability in halide perovskite films compared to those made from raw precursors or those purified via common methods like retrograde powder crystallization (RPC) [7].

- Characterize Purification Efficacy: Use detailed chemical analysis to verify the removal of extrinsic impurities. Compare the performance of materials synthesized from purified precursors against those from raw precursors under operational stressors like light and heat to confirm improvements in phase stability [7].

- Control Precursor Rheology and Composition: The physical properties of a preceramic polymer (a common type of precursor), such as its melting point, glass transition temperature, and viscosity, are critical. These can be adjusted by using monofunctional monomers (to lower molecular weight and viscosity) or tri/tetrafunctional monomers (to increase molecular weight and viscosity), ensuring the precursor is suitable for the intended shaping process [8].

FAQ: What strategies can mitigate thermodynamic trapping and its effects on material properties?

Root Cause Analysis: Thermodynamic trapping occurs when solute atoms, such as interstitials or impurities, become immobilized at microstructural defects like grain boundaries or phase interfaces. This is governed by the interaction between lattice sites and "traps," leading to site competition effects, especially in systems with multiple solute species [9].

Solutions and Verification Methods:

- Model Multi-Species Interactions: Use advanced trapping and diffusion models for multiple species of solute atoms in a system with multiple sorts of traps. These models, based on irreversible thermodynamics, can predict kinetics of exchange between the lattice and traps, as well as site competition effects [9].

- Simulate Process Conditions: Implement numerical simulations for processes like charging and discharging in samples containing multiple sorts of traps occupied by multiple species. This helps in understanding the role of trapping parameters, site competition effects, and the interaction of trapping kinetics with diffusion kinetics [9].

- Design Precursor Cross-Linking: To prevent the distillation of low-molecular-weight oligomers or thermal decomposition into volatile compounds—processes that can exacerbate non-equilibrium trapping—cross-link the polymer chains to form a tridimensional network. This must be done after the shaping of the precursor during a curing step and requires the precursor to have reactive substituents [8].

FAQ: How does precursor selection influence the formation of undesired by-products?

Root Cause Analysis: The selection of a precursor directly determines the composition, reactivity, and structure of the intermediate and final products. An ill-suited precursor can lead to undesired by-products through several mechanisms, including the accumulation of unexpected small RNAs in biological systems [10] or the formation of a problematic "free-carbon" phase in polymer-derived ceramics [8].

Solutions and Verification Methods:

- Analyze By-Product Accumulation: When using artificial miRNA (amiRNA) precursors, employ deep-sequencing techniques to analyze the accumulation of small RNAs in transgenic systems. This can reveal the presence of additional, undesired small RNAs originating from other regions of the precursor, which may silence unintended gene targets [10].

- Optimize Precursor Composition: Tune the elemental composition of the precursor to be as close as possible to the target ceramic to maximize ceramic yield and minimize free carbon. This can be achieved through monomer design, copolymerization, or chemical modification of the polymer [8].

- Ensure Precursor Stability: Use precursors that are stable at the processing temperature to ensure stable viscosity and reproducible shaping. Stability to air and moisture is also advantageous for easier processing and longer "pot-life" [8].

Table 1: Impact of Precursor Purity and Purification Methods on Material Performance

| Precursor Type / Purification Method | Key Impurity Change | Impact on Final Material Properties | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Purity (99%) PbI2 (Raw) | Broad set of extrinsic impurities | Reduced phase purity and stability under light and heat | Chemical analysis, stability testing [7] |

| High Purity (99.99%) PbI2 (Raw) | Fewer initial impurities | Improved performance over low-purity raw precursor | Chemical analysis, stability testing [7] |

| Purification via Retrograde Powder Crystallization (RPC) | Partial impurity removal | Improved performance over raw precursors, but less effective than SONIC | Comparison of phase stability [7] |

| Purification via Solvent Orthogonality Induced Crystallization (SONIC) | Removal of a broad set of extrinsic impurities | Improved phase purity and stability under operational stressors | Detailed chemical analysis, enhanced phase stability [7] |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Precursor Synthesis and Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| SONIC (Solvent Orthogonality Induced Crystallization) | Advanced purification technique to remove trace impurities from solid precursors. | Halide Perovskites, Materials Synthesis [7] |

| Electron Microscopy | Enables structural and chemical identification at the atomic scale for precursor and derived material. | MXenes, MAX Phases, 2D Materials [11] |

| Deep-Sequencing Technique | Analyzes the accumulation of small RNAs to identify desired products and undesired by-products. | Artificial miRNA Technology, Genetics [10] |

| Cross-Linking Agents | Substances that connect polymer chains into a 3D network, preventing distillation and increasing ceramic yield. | Preceramic Polymers, Polymer-Derived Ceramics [8] |

| Trapping and Diffusion Model | A theoretical model based on irreversible thermodynamics to simulate solute trapping at defects. | Hydrogen Embrittlement, Multicomponent Diffusion [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Single Crystal Purification of Precursors via SONIC

Objective: To remove trace impurities from commercially available halide perovskite precursors to improve the phase purity and stability of the final material [7].

- Selection: Obtain the commercial precursor (e.g., PbI2) of known purity.

- Crystallization: Employ the Solvent Orthogonality Induced Crystallization (SONIC) method to grow bulk single crystals of the target material (e.g., FAPbI3).

- Processing: Isolate the purified single crystals.

- Verification: Subject the purified crystals to detailed chemical analysis to verify the removal of extrinsic impurities.

- Application: Fabricate thin films using the purified precursor material.

- Testing: Evaluate the phase purity and stability of the resulting films under operational stressors (light and heat) and compare against films made from raw or alternatively purified precursors.

Protocol: Analysis of Undesired Small RNA Accumulation from amiRNA Precursors

Objective: To map processing intermediates and identify the accumulation of undesired small RNAs from an artificial microRNA precursor [10].

- Transformation: Express the artificial miRNA (e.g., amiRchs1 based on the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor) in the model organism (e.g., Petunia hybrida).

- Phenotypic Validation: Observe and confirm the intended gene-silencing phenotype in transgenic plants.

- Mapping: Use a modified 5' RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends) technique to map small-RNA-directed cleavage sites on the target mRNA and to detect processing intermediates of the amiRNA precursor.

- Sequencing: Analyze the accumulation of small RNAs in the tissue of interest using deep-sequencing technology.

- Bioinformatics: Process the sequencing data to identify the sequences and abundances of all small RNAs, focusing on the desired amiRNA and any additional small RNAs originating from other regions of the precursor.

- Target Prediction: Use computational tools to discover potential unintended targets of the undesired small RNAs within the host genome.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Precursor Selection and Optimization Workflow

Thermodynamic Trapping in Multi-Species Systems

Frequently Asked Questions

What does 'optimal' mean in the context of precursor selection? An optimal precursor set is one that provides a sufficient thermodynamic driving force to form the target material while minimizing kinetic traps. This involves maximizing the free energy difference between the target and competing phases and avoiding reaction pathways that form stable, unreactive intermediates that consume this driving force [2] [12].

My synthesis consistently produces unwanted by-products, even within the target's stability region. Why? Traditional phase diagrams show stability regions but do not visualize the thermodynamic competition from other phases. To minimize by-products, you should aim for synthesis conditions that not only fall within the target's stability region but also maximize the free energy difference (ΔΦ) between your target phase and its most competitive neighboring phase [12]. This approach, known as Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC), reduces the kinetic propensity for by-products to form.

How can I select precursors when I have a constrained set of starting materials? Constrained synthesis planning addresses this exact challenge. Novel algorithms, such as Tango*, use a computed node cost function to guide a retrosynthetic search towards your specific, enforced starting materials (e.g., waste products or specific feedstocks). This method efficiently finds viable synthesis pathways from a limited set of precursors [13] [14].

Is a larger thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) always better? Not necessarily. While a more negative ΔG generally indicates a stronger driving force and faster reaction kinetics, it can sometimes lead to the rapid formation of highly stable intermediate compounds. These intermediates can act as kinetic traps, consuming the available driving force and preventing the formation of your final target material [2]. The optimal pathway avoids such intermediates to retain a large driving force for the target-forming step (ΔG') [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Synthesis Fails to Form the Target Phase

Possible Cause 1: Formation of Stable Intermediates The chosen precursors react to form thermodynamically favorable intermediate compounds that are kinetically inert, halting the reaction [2].

- Diagnosis: Use in-situ characterization techniques like XRD at different temperatures to identify which intermediates form. Algorithms like ARROWS3 are designed to automate this analysis [2].

- Solution: Select an alternative precursor set that avoids the pairwise reactions leading to the problematic intermediate. The goal is to find a route that retains a large thermodynamic driving force (ΔG') all the way to the target phase [2].

Possible Cause 2: High Thermodynamic Competition from By-Products Even within the thermodynamic stability region of your target, the driving force to form a competing by-product phase may be similar to that of your target, leading to impure products [12].

- Diagnosis: Calculate the thermodynamic competition metric, ΔΦ(Y) = Φtarget(Y) - min(Φcompeting(Y)), across your synthesis conditions (e.g., pH, E, concentration) [12].

- Solution: Optimize your synthesis conditions (e.g., pH, redox potential) to the point where ΔΦ is minimized—meaning the energy difference between the target and its strongest competitor is maximized [12].

Problem: Inability to Plan a Synthesis with Mandated Starting Materials

Possible Cause: Inflexible Search Algorithm Standard computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) algorithms are designed to find a pathway to any purchasable building block, not your specific constrained set [13] [14].

- Diagnosis: Your target molecule contains key structural motifs not present in the default purchasable set, or you are required to use specific starting materials for waste valorization or semi-synthesis.

- Solution: Employ a constrained synthesis planning tool like Tango*. This method uses a Tanimoto similarity-based cost function to guide the retrosynthetic search towards your enforced starting materials, significantly improving the solve rate for this specific problem [13] [14].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Quantitative Synthesis Outcomes for Different Optimization Algorithms on YBCO Target [2]

| Algorithm / Method | Total Experiments | Successful Syntheses Identified | Key Metric / Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARROWS3 | Substantially fewer | All effective routes | Avoids intermediates to preserve ΔG' |

| Bayesian Optimization | More than ARROWS3 | Not specified | Black-box parameter tuning |

| Genetic Algorithm | More than ARROWS3 | Not specified | Black-box parameter tuning |

| Initial Ranking (DFT ΔG) | N/A | N/A | Ranks by initial driving force (ΔG) only |

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Synthesis Planning

| Tool Name | Field | Primary Function | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARROWS3 [2] | Solid-State Materials | Autonomous precursor selection | Active learning from experiments to avoid kinetic intermediates. |

| Tango* [13] [14] | Organic Chemistry/Molecules | Starting material-constrained synthesis planning | Guides search using Tanimoto similarity to enforced blocks. |

| MTC Framework [12] | Aqueous Materials Synthesis | Condition optimization (pH, E, concentration) | Maximizes free energy difference between target and competing phases. |

| SynthNN [15] | Inorganic Crystalline Materials | Synthesizability prediction | Deep learning model trained on known materials data. |

Protocol 1: Validating Synthesis with the ARROWS3 Workflow [2]

- Input & Initial Ranking: Provide your target material's composition and a list of potential precursors. The algorithm will stoichiometrically balance the precursors and provide an initial ranking based on the DFT-calculated thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target.

- Experimental Probing: Synthesize the highest-ranked precursor sets across a range of temperatures (e.g., 600–900 °C) with a short hold time (e.g., 4 hours) to capture reaction snapshots.

- Phase Analysis: Analyze the products at each temperature using X-ray diffraction (XRD). Machine-learning analysis (e.g., XRD-AutoAnalyzer) can be used to automatically identify crystalline intermediates and by-products.

- Pathway Learning: The algorithm identifies which pairwise reactions between precursors led to the observed intermediates.

- Route Optimization: ARROWS3 updates its precursor ranking, now prioritizing sets predicted to avoid energy-consuming intermediates, thereby maintaining a large driving force (ΔG') to the final target.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 until the target is synthesized with high purity or all precursor sets are exhausted.

Protocol 2: Applying the Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) Framework for Aqueous Synthesis [12]

- Define System: Identify your target phase and all possible competing solid phases in the chemical space.

- Calculate Free Energy Surfaces: Compute the Pourbaix potential (Ψ) for all phases. This free-energy surface is a function of intensive variables: pH, redox potential (E), and aqueous metal ion concentrations.

- Compute Thermodynamic Competition: For a given set of conditions (pH, E, [ions]), calculate the thermodynamic competition metric: ΔΦ = Φtarget - min(Φcompeting).

- Optimize Conditions: Use a gradient-based algorithm to find the conditions (Y* = pH, E, [ions]*) that minimize ΔΦ. This is the point of maximum energy difference between your target and its closest competitor.

- Experimental Validation: Perform synthesis at the predicted optimal conditions (Y) and at other conditions within the stability region for comparison. Phase-pure yield is expected primarily at Y.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

- DFT-Calculated Reaction Energies (ΔG): Serves as the initial, high-throughput filter for ranking potential precursor sets based on their thermodynamic driving force to form the target material [2].

- In-Situ XRD with ML Analysis: A critical diagnostic tool for "looking into the black box" of solid-state reactions. It identifies intermediate and by-product phases that form during heating, providing essential data for route optimization [2].

- Multi-Element Pourbaix Diagrams: Provide the free-energy surfaces needed to compute the stability of target and competing phases in aqueous electrochemical systems, forming the basis for the MTC analysis [12].

- Tanimoto Similarity & FMS: A simple but powerful cheminformatics calculation used in the Tango* algorithm to measure molecular similarity and guide retrosynthetic searches towards desired starting materials [13] [14].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

ARROWS3-Informed Precursor Optimization Cycle

Finding Conditions for Minimum Thermodynamic Competition

Data Mining and Statistical Insights from Historical Synthesis Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental connection between statistical analysis and data mining in materials research? Data mining and statistical analysis are deeply interconnected fields that together enable powerful insights from complex materials data. Statistical analysis provides the foundational framework for hypothesis testing, inference, and parameter estimation, while data mining offers scalable algorithms for pattern recognition and predictive modeling in large datasets. In precursor materials research, this synergy allows researchers to uncover hidden relationships between synthesis parameters and material properties, validate findings through statistical significance testing, and build robust predictive models for optimizing precursor selection [16] [17].

Q2: How can I troubleshoot a data mining model that shows good training performance but poor predictive accuracy on new precursor datasets? This common issue, known as overfitting, occurs when models memorize training data patterns instead of learning generalizable relationships. Solutions include: (1) Applying cross-validation techniques to assess real-world performance during development [17]; (2) Implementing regularization methods (L1/L2) to penalize model complexity; (3) Using ensemble methods like Random Forests that are naturally more robust to overfitting; (4) Ensuring your training dataset adequately represents the variability in chemical space and synthesis conditions expected in real applications [17].

Q3: What statistical measures are most appropriate for evaluating clustering results in precursor categorization? For clustering analysis in precursor materials, use multiple validation metrics: (1) Internal indices like Silhouette Coefficient measure cluster separation and cohesion; (2) External indices like Adjusted Rand Index compare to known classifications when available; (3) Stability analysis assesses result consistency across subsamples; (4) Domain-specific validation through expert review of chemically similar groupings. The combination of statistical metrics and domain knowledge ensures practically meaningful clusters [17].

Q4: How can I address missing or incomplete data in historical precursor synthesis records? Several statistical approaches can handle missing data: (1) Multiple Imputation creates several complete datasets by estimating missing values with uncertainty; (2) Maximum Likelihood methods model the missing data mechanism; (3) For data missing not-at-random, selection models account for systematic missingness. Document the extent and patterns of missingness first, as this informs the optimal approach and potential biases [16].

Q5: What are the key considerations for ensuring reproducible data mining workflows in collaborative precursor research? Reproducibility requires both technical and methodological rigor: (1) Version control for all code and data processing steps; (2) Comprehensive documentation of preprocessing decisions and parameter settings; (3) Containerization (e.g., Docker) to capture computational environments; (4) Implementation of standardized validation protocols for all models; (5) Clear reporting of effect sizes with confidence intervals alongside statistical significance [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inadequate Model Performance for Precursor Property Prediction

Symptoms

- Low predictive accuracy (R² < 0.7, high RMSE) on test datasets

- Large discrepancies between training and validation performance

- Failure to identify known precursor-property relationships

| Step | Investigation | Diagnostic Methods | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data Quality Assessment | Missing value analysis, outlier detection, feature distributions | Data imputation, outlier treatment, domain-specific data transformation [18] |

| 2 | Feature Relevance | Correlation analysis, mutual information, domain expertise | Feature selection, creation of domain-informed features, dimensionality reduction [17] |

| 3 | Model Complexity | Learning curves, bias-variance analysis | Regularization, ensemble methods, neural network architecture optimization [16] |

| 4 | Validation Methodology | Cross-validation schemes, residual analysis | Stratified sampling, temporal validation splits, statistical testing of differences [17] |

Validation Protocol Implement a rigorous validation workflow: (1) Begin with train-test split (70-30%); (2) Apply k-fold cross-validation (k=5-10) on training set for model selection; (3) Evaluate final model on held-out test set; (4) Compute multiple performance metrics (R², RMSE, MAE) with confidence intervals; (5) Conduct external validation with newly synthesized precursors when possible [17].

Problem: Unstable Clustering Results Across Precursor Datasets

Symptoms

- Cluster assignments change significantly with different algorithm initializations

- Varying results when adding new precursor compounds to the dataset

- Poor alignment between statistical clusters and chemical functionality

Diagnostic and Resolution Workflow

Resolution Steps

- Data Preprocessing Assessment: Ensure consistent feature scaling (standardization/normalization) across datasets. Different scaling approaches can dramatically affect distance-based clustering. Assess feature relevance using domain knowledge to eliminate noisy variables [17].

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically test parameter sensitivity, especially for algorithms like k-means (number of clusters) and DBSCAN (epsilon, min_samples). Use stability analysis across multiple runs with different initializations.

Alternative Algorithm Testing: Compare multiple clustering approaches (k-means, hierarchical, DBSCAN, Gaussian Mixture Models) using stability metrics. Ensemble clustering methods often provide more robust results.

Multi-metric Validation: Employ both internal (silhouette, Davies-Bouldin) and external (adjusted Rand index) validation metrics. Incorporate domain expert evaluation to ensure chemically meaningful clusters.

Problem: Spurious Correlations in Historical Precursor Data

Symptoms

- Statistically significant correlations that lack mechanistic explanation

- Model coefficients that contradict established chemical principles

- Failure to generalize across different precursor families

Detection and Mitigation Strategies

| Strategy | Implementation | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Causal Analysis | Directed acyclic graphs, domain knowledge mapping | Distinguish causal from correlational relationships using established precursor chemistry [17] |

| Multiple Testing Correction | Bonferroni, Benjamini-Hochberg procedures | Control false discovery rate when testing multiple hypotheses simultaneously [17] |

| Cross-Validation | Leave-one-family-out validation, temporal splits | Test robustness across different precursor classes and synthesis periods |

| Mechanistic Validation | Experimental verification, literature consistency | Ensure statistical relationships align with known chemical mechanisms |

Experimental Protocol for Correlation Validation

- Hypothesis Formulation: Pre-specify expected relationships based on chemical principles before data analysis

- Data Splitting: Implement strict train-validation-test splits with no data leakage

- Significance Testing: Apply appropriate multiple testing corrections for all statistical tests

- Effect Size Reporting: Focus on practically significant effect sizes rather than statistical significance alone

- External Validation: Test identified relationships in independently synthesized precursor datasets

Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Specific Tools/Frameworks | Application in Precursor Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis | R, Python (Scipy, Statsmodels), SPSS | Experimental design, hypothesis testing, relationship quantification | Ensure appropriate model assumptions, implement multiple testing corrections [17] |

| Data Mining Platforms | KNIME, RapidMiner, Weka | Pattern discovery, predictive modeling, clustering analysis | Balance model complexity with interpretability needs [19] |

| Visualization Tools | Tableau, RAWGraphs, Python (Matplotlib, Seaborn) | Exploratory data analysis, result communication, quality assessment | Prioritize clarity and accurate representation of statistical uncertainty [19] [20] |

| Domain-Specific Databases | ICSD, Materials Project, PubChem | Precursor property data, historical synthesis records, structural information | Address data quality variability, missing values, and standardization issues [16] |

Experimental Workflow for Precursor Selection Optimization

Methodology Details

Historical Data Collection

- Compile comprehensive historical synthesis data including precursor structures, processing conditions, and characterization results

- Standardize data formats and units across different sources

- Document data provenance and quality indicators

Data Preprocessing & Cleaning

- Address missing values using appropriate imputation methods

- Detect and handle outliers using statistical methods (e.g., Tukey's fences)

- Normalize/standardize features based on distribution characteristics

- Engineer domain-informed features capturing relevant chemical descriptors

Exploratory Data Analysis

- Conduct principal component analysis to identify major variation sources

- Perform correlation analysis to identify potential relationships

- Visualize distributions and relationships across precursor classes

- Identify potential confounding variables and data quality issues

Predictive Modeling

- Implement multiple algorithm types (regression, random forests, neural networks)

- Utilize ensemble methods to improve predictive stability

- Optimize hyperparameters using cross-validation

- Assess feature importance for mechanistic insights

Statistical Validation

- Apply rigorous train-test-validation splits

- Compute confidence intervals for all performance metrics

- Conduct sensitivity analysis for key model assumptions

- Perform external validation with newly synthesized precursors

Precursor Optimization

- Utilize validated models for precursor selection and design

- Implement optimization algorithms to identify optimal precursor characteristics

- Balance multiple objectives (performance, cost, sustainability)

- Establish confidence estimates for prediction-based decisions

This troubleshooting framework enables researchers to systematically address common challenges in data mining and statistical analysis of precursor materials data, leading to more robust and reliable insights for materials design and optimization.

The Problem of Precursor Interdependencies and Non-Random Combinations

Frequently Asked Questions

What are precursor interdependencies in materials synthesis? Precursor interdependencies refer to the chemical reactions and interactions that occur between different precursor materials before or during the formation of a target material. These pairwise reactions can dominate the synthesis process, often leading to unwanted impurity phases if not properly controlled [1].

Why is the "non-random" selection of precursors critical? Traditional methods of selecting precursors often result in a final product that is a mix of different compositions and structures. A non-random, criteria-based selection process aims to avoid these unwanted side reactions, thereby significantly increasing the yield and phase purity of the desired target material [1].

What is a key modern method for validating precursor selection? Robotic high-throughput synthesis laboratories are now used to rapidly validate precursor choices. These systems can perform hundreds of separate reactions in a few weeks, a task that would typically take months or years, allowing for the quick identification of the most effective precursor combinations [1].

How can I troubleshoot the formation of impurity phases? The formation of impurity phases is a primary challenge in synthesizing multi-element materials. It is often a direct result of undesirable pairwise reactions between precursors. Consult the troubleshooting guide below for a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving this issue.

Troubleshooting Guide: Precursor-Related Synthesis Challenges

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High impurity phases in final product | Undesirable pairwise reactions between precursors [1] | Re-select precursors using criteria that avoid these specific side reactions, guided by phase diagrams [1]. |

| Low yield of target material | Synthetic pathway dominated by reactions leading to by-products [1] | Adopt a pairwise reaction analysis to map all potential precursor interactions and select precursors that favor the target pathway [1]. |

| Inconsistent results between batches | Variability in raw material purity or supplier quality [4] | Source precursors from reliable, certified vendors and implement strict quality control checks upon receipt [4]. |

Experimental Data: The Impact of Systematic Precursor Selection

Recent research demonstrates the profound impact of a systematic precursor selection strategy. In a large-scale study targeting 35 multi-element oxide materials, a new method of choosing precursors based on pairwise reaction analysis was tested against traditional approaches in 224 separate reactions.

Table: Efficacy of New Precursor Selection Criteria

| Synthesis Method | Number of Target Materials | Success Rate (Higher Purity Achieved) |

|---|---|---|

| New Precursor Selection Criteria | 35 | 32 out of 35 (91%) [1] |

| Traditional Precursor Selection | 35 | Not explicitly stated (Lower yield for 32 materials) [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Pairwise Precursor Analysis

This protocol is adapted from research on synthesizing inorganic materials using a pairwise reaction strategy to minimize impurities [1].

Objective: To synthesize a target multi-element material with high phase purity by selecting precursors that minimize undesirable intermediary reactions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Precursor powders

- Robotic inorganic materials synthesis laboratory (e.g., ASTRAL) OR conventional furnace [1]

- Analytical equipment for phase purity determination (e.g., X-ray Diffraction)

Methodology:

- Define Target Phase: Clearly identify the chemical composition and crystal structure of the desired final material.

- Map Potential Precursors: List all possible precursor compounds containing the required elements.

- Analyze Pairwise Reactions: Use available phase diagrams to theorize and model the binary reactions that could occur between every possible pair of the identified precursors [1].

- Apply Selection Criteria: Establish and apply criteria for precursor selection that specifically avoid combinations predicted to result in stable impurity phases [1].

- High-Throughput Validation: Use a robotic synthesis lab to rapidly test the selected precursor combinations and hundreds of alternatives in parallel. This involves mixing powders and reacting them at high temperatures [1].

- Characterize Output: Analyze the products of each reaction to determine the phase purity and yield of the target material.

- Optimize and Iterate: Use the results to refine the selection criteria and identify the optimal precursor set for large-scale synthesis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Precursor Selection and Synthesis

| Item | Function in Research | Relevance to Precursor Interdependencies |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | The raw materials that react to form the target product. | Their inherent reactivity dictates the success of the synthesis; purity and selection are paramount [1] [21]. |

| Phase Diagrams | Maps that show the equilibrium phases in a material system at different conditions. | Critical for predicting stable intermediary compounds and avoiding them during precursor selection [1]. |

| Robotic Synthesis Lab | An automated system for high-throughput experimentation. | Dramatically accelerates the testing of precursor combinations and validation of selection criteria [1]. |

Workflow Diagram: Systematic Precursor Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting optimal precursors to avoid problematic interdependencies, based on the successful methodology validated in recent research.

Modern Methodologies: From Thermodynamic Modeling to AI-Powered Recommendation Systems

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Failure to Form Target Material

Problem: Despite favorable overall reaction thermodynamics (ΔG < 0), the target material does not form, or yield is low due to persistent impurity phases.

Diagnosis: This commonly occurs when highly stable intermediates form through competing pairwise reactions, consuming the available thermodynamic driving force before the target material can nucleate and grow [2].

Solution:

- Identify Intermediates: Use in-situ characterization techniques like high-temperature X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to identify intermediate phases that form during the reaction pathway [2].

- Re-select Precursors: Use an algorithm like ARROWS3 to re-evaluate precursor choices. The algorithm prioritizes precursor sets that avoid the formation of the identified stable intermediates, thereby preserving a larger driving force (ΔG′) for the target material's formation [2].

- Validate Robotically: For rapid iteration, use a robotic materials synthesis laboratory to test the new precursor selections across a range of conditions [1].

Guide 2: Correcting Inaccurate ΔG Predictions

Problem: Predicted reaction Gibbs free energy (ΔG) does not match experimental observations, leading to poor precursor selection.

Diagnosis: Inaccuracies can stem from several sources: inadequate level of theory in computational methods, ignoring solvation effects, or incorrect treatment of pH for biochemical reactions [22].

Solution:

- Benchmark Computational Methods: For quantum chemistry calculations, benchmark exchange-correlation functionals and basis sets against a known database like NIST. The SCAN-D3(BJ) meta-GGA functional is recommended for main group thermochemistry [22].

- Include Solvation and pH: Always use an implicit solvation model (e.g., SMD) for reactions in solution. For biochemical reactions, calculate free energies at the relevant pH (e.g., pH 7) [22].

- Apply Calibration: Use a simple linear calibration against experimental data to reduce the mean absolute error of DFT-predicted ΔG values to within 1.60–2.27 kcal/mol [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I quickly determine if a reaction will be spontaneous? A1: Use the sign of the Gibbs Free Energy change (ΔG). A reaction is spontaneous if ΔG is negative, non-spontaneous if positive, and at equilibrium if zero [23] [24]. The relationship between enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), and temperature dictates the sign of ΔG [24]:

| ΔH | ΔS | Spontaneity |

|---|---|---|

| – | + | Spontaneous at all temperatures |

| + | – | Non-spontaneous at all temperatures |

| – | – | Spontaneous at low temperatures |

| + | + | Spontaneous at high temperatures |

Q2: What does a "thermodynamic driving force" mean in materials synthesis? A2: It refers to the negative Gibbs Free Energy change (ΔG) for a reaction. A more negative ΔG value indicates a stronger driving force for the reaction to proceed, often leading to faster reaction rates. The key is to select precursors that maximize this driving force specifically for the formation of the target material, not for competing intermediates [2].

Q3: My target material is metastable. Can I still use thermodynamic data for synthesis planning? A3: Yes. Thermodynamic data is still crucial. The strategy shifts towards selecting precursors and reaction conditions where the kinetic barrier for forming the metastable phase is lower than that for the stable competing phases. This often involves identifying precursors that avoid the formation of very stable, inert intermediates that would consume all the available driving force [2].

Q4: Which thermodynamic parameters are most critical for selecting solid-state synthesis precursors? A4: The Gibbs Free Energy of reaction (ΔG) is the primary master variable. Precursor sets should be initially ranked by how negative their ΔG is for the target material [2]. Furthermore, consulting phase diagrams is essential to understand and avoid unfavorable pairwise reactions between precursors that could lead to stable impurity phases [1].

Q5: What is a common pitfall when using computational chemistry to predict ΔG? A5: A major pitfall is performing calculations in the gas phase for reactions that occur in solution. You must use an implicit solvation model to accurately account for the effects of the solvent environment on the free energy of metabolites and reactions [22].

Quantitative Data for Reaction Analysis

Table 1: Performance of DFT Functionals for Predicting ΔG of Biochemical Reactions [22]

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | Type | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| SCAN-D3(BJ) | meta-GGA | ~1.60 |

| B3LYP-D3 | Hybrid | ~2.27 |

| PBE | GGA | Varies (benchmark required) |

Note: Error ranges are achieved after calibration with experimental data. The chemical accuracy benchmark is 1 kcal/mol.

Table 2: Influence of Manganese Precursor on Phosphor Synthesis Efficiency [25]

| Manganese Precursor | Oxidation State | Final Active Ion | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MnO₂ | +4 | Mn²⁺ | 17.69% |

| Mn₂O₃ | +3 | Mn²⁺ | 7.59% |

| MnCO₃ | +2 | Mn²⁺ | 2.67% |

Note: Synthesis was performed via a Microwave-Assisted Solid-State (MASS) method, demonstrating how precursor selection directly impacts final material performance, even when the final dopant ion is the same.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Precursor Selection and Validation using ARROWS3

Purpose: To autonomously select and experimentally validate optimal precursor sets for a target material, avoiding kinetic traps from stable intermediates [2].

Methodology:

- Input: Define the target material's composition and a list of potential precursors.

- Initial Ranking: The algorithm ranks all stoichiometrically balanced precursor sets by their calculated thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target.

- Experimental Testing: The top-ranked precursor sets are synthesized in a robotic lab across a temperature gradient (e.g., 600–900°C).

- Phase Analysis: Products at each temperature are characterized using XRD, with automated phase analysis to identify the target and any impurity phases.

- Pathway Learning: The algorithm identifies the specific pairwise reactions between precursors that led to the observed intermediate phases.

- Re-ranking: The precursor list is re-ranked to favor sets predicted to avoid these energy-draining intermediates, preserving a large driving force (ΔG′) for the target.

- Iteration: Steps 3-6 are repeated until a high-purity target is achieved or all options are exhausted.

The following workflow visualizes the ARROWS3 algorithm's iterative optimization process:

Protocol 2: Quantum Chemistry Calculation of ΔG for Metabolic Reactions

Purpose: To accurately predict the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°ᵣ) for biochemical reactions using Density Functional Theory (DFT) [22].

Methodology:

- Metabolite Input: Obtain SMILES strings of all reactants and products from a database like ModelSEED.

- Generate Microspecies: Use software (e.g., Chemaxon) to generate the major microspecies of each metabolite at the desired pH (0 or 7).

- Geometry Optimization: Generate 3D geometries and optimize them using a functional like B3LYP-D3 with a 6-31G* basis set.

- Solvation Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry using a larger basis set (e.g., 6-311++G) and an implicit solvation model (SMD) to account for aqueous effects.

- Thermal Correction: Calculate the vibrational frequencies to determine the entropy (S) and enthalpy (H) contributions to free energy.

- Compute ΔG°ᵣ: Combine the standard Gibbs free energies of all metabolites to calculate the reaction free energy.

- Calibration: Benchmark and calibrate the calculated values against experimental data from the NIST database.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Thermodynamics-Driven Materials Synthesis

| Item | Function | Example Application in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| ARROWS3 Algorithm | An active learning algorithm that autonomously selects precursors by learning from failed experiments to avoid stable intermediates [2]. | Optimizing precursor choices for YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO) and metastable Na₂Te₃Mo₃O₁₆ [2]. |

| Robotic Synthesis Lab | Automates high-throughput solid-state synthesis, allowing for rapid testing of dozens of precursor combinations and conditions [1]. | Validating new precursor selection criteria by synthesizing 35 target materials in 224 separate reactions in a few weeks [1]. |

| DFT Computation (e.g., NWChem) | Provides first-principles quantum mechanical calculations of Gibbs free energy for reactions and metabolites, filling gaps where experimental data is lacking [22]. | Predicting ΔG°ᵣ for metabolic reactions with high accuracy, enabling thermodynamic modeling of biological systems [22]. |

| Microwave-Assisted Solid-State (MASS) Reactor | Enables rapid, energy-efficient synthesis by using microwave radiation to heat precursors directly, often leading to different reaction pathways [25]. | Rapid synthesis of Mn²⁺-doped Na₂ZnGeO₄ phosphors, efficiently incorporating Mn from various precursor oxides [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core function of the ARROWS3 algorithm? ARROWS3 is designed to automate the selection of optimal precursors for solid-state materials synthesis. It actively learns from experimental outcomes to identify which precursor combinations lead to the formation of highly stable intermediates that prevent the target material from forming. Based on this learning, it subsequently proposes new experiments using precursors predicted to avoid such intermediates, thereby preserving a larger thermodynamic driving force to form the desired target material [26] [2].

Q2: How does ARROWS3 differ from black-box optimization methods? Unlike black-box optimization algorithms like Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms, ARROWS3 incorporates physical domain knowledge, specifically thermodynamics and pairwise reaction analysis. This allows it to identify effective precursor sets while requiring substantially fewer experimental iterations by understanding why certain reactions fail (e.g., by identifying specific energy-draining intermediates) rather than just relying on correlative optimization [26] [2] [27].

Q3: What initial data does ARROWS3 use to propose its first experiments? In the absence of prior experimental data, ARROWS3 initially ranks potential precursor sets based on their calculated thermodynamic driving force (∆G) to form the target material. This thermochemical data is typically sourced from first-principles calculations in databases like the Materials Project [26] [2].

Q4: What key hypotheses about solid-state reactions does ARROWS3 utilize? The algorithm operates on two critical hypotheses:

- Solid-state reactions often proceed through stepwise transformations between two phases at a time (pairwise reactions) [26] [28].

- Intermediate phases that consume a large portion of the available free energy should be avoided, as they leave a small driving force for the final target material to form [26] [29].

Q5: What experimental characterization technique is integral to the ARROWS3 workflow? X-ray diffraction (XRD) is used to characterize the products of synthesis experiments at various temperatures. Machine learning models (e.g., XRD-AutoAnalyzer) are then employed to identify the crystalline intermediates formed at each step of the reaction pathway [26] [2].

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Algorithm Fails to Propose New Precursors After Failed Experiment

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unidentified Intermediates | Verify that XRD patterns were successfully collected and that the machine learning analysis provided a confident phase identification for all major peaks [26]. | Ensure sample preparation for XRD is consistent. Manually review the XRD pattern and phase identification results to confirm accuracy. |

| Insufficient Thermodynamic Data | Check if the observed intermediate phases are present in the thermodynamic database (e.g., Materials Project) used to calculate driving forces [26] [28]. | Manually calculate or locate the formation energy for the missing phase(s) and update the local database. |

| All Proposed Precursor Sets Exhausted | Review the algorithm's log to see how many precursor combinations have been tested [2]. | Expand the list of available precursor candidates for the algorithm to consider. |

Issue 2: Synthesis Fails Despite Favorable Predicted Driving Force

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sluggish Reaction Kinetics | Check the calculated driving force (∆G′) for the final step from the last intermediate to the target. If it is low (e.g., < 50 meV/atom), kinetics are likely too slow [28] [29]. | The algorithm should automatically learn to avoid this path. Consider increasing synthesis temperature or time in the next proposed experiment. |

| Precursor Volatility or Decomposition | Review thermal stability data (e.g., TGA) for the precursor materials used. | ARROWS3 may not account for volatility. Manually exclude volatile precursors or precursors that decompose into undesirable phases. |

| Formation of Amorphous Intermediates | Analyze the XRD pattern for a high background, which may suggest the presence of amorphous content that the ML model cannot identify [29]. | Consider alternative characterization techniques or synthesis parameters that promote crystallization. |

Issue 3: Inconsistent Experimental Outcomes at the Same Temperature

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Powder Mixing | Check the experimental protocol for milling or grinding steps. Inconsistent particle contact can lead to irreproducible reactions [28]. | Standardize the milling procedure (time, intensity) to ensure homogeneous precursor mixtures across all experiments. |

| Furnace Temperature Gradients | Place temperature sensors at different locations within the furnace to map thermal profiles during a heating cycle. | Calibrate furnaces regularly and use a consistent, well-characterized location for sample placement during synthesis. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Core ARROWS3 Algorithmic Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the autonomous decision-making cycle of the ARROWS3 algorithm.

Detailed Methodology for a Synthesis Experiment

The table below summarizes the protocol for the synthesis experiments targeting YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO) used to validate ARROWS3 [26] [2].

| Experimental Step | Parameter Details | Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Preparation | 47 different combinations of Y-, Ba-, Cu-, and O- containing precursors. | Precursors are commonly available solid powders (e.g., Y₂O₃, BaCO₃, CuO). |

| Mixing | Precursors are mixed and ground into a fine powder to ensure good reactivity. | The physical mixing process is critical for reproducible solid-state reactions [28]. |

| Heating Profile | Heated at four different temperatures: 600°C, 700°C, 800°C, and 900°C. A short hold time of 4 hours was used. | Testing across a temperature gradient provides snapshots of the reaction pathway. |

| Characterization | Products analyzed by X-ray Diffraction (XRD). | |

| Data Analysis | XRD patterns are analyzed using a machine-learned analyzer (XRD-AutoAnalyzer) to identify crystalline phases present [26]. | Automated phase identification is key for high-throughput analysis. |

| Pathway Determination | ARROWS3 determines which pairwise reactions led to the observed intermediates. | This step converts experimental observations into a mechanistic understanding of the failure. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential components and their functions within the ARROWS3-driven synthesis ecosystem.

| Item / Solution | Function in the Workflow | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Database | Provides initial formation energies (∆G) for ranking precursors and calculating driving forces for pairwise reactions. | Materials Project database [26] [28]. |

| Precursor Library | A comprehensive list of available solid powder precursors that can be stoichiometrically balanced to yield the target's composition. | E.g., For YBCO: Y₂O₃, BaCO₃, CuO, BaO₂, Y(NO₃)₃, etc. [26]. |

| Machine Learning Phase Identifier | Automatically identifies crystalline phases and their weight fractions from XRD patterns of reaction products. | XRD-AutoAnalyzer or probabilistic models trained on the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [26] [28]. |

| Pairwise Reaction Database | A continuously updated database of observed solid-state reactions between two phases at a time, built from experimental outcomes. | Contains reactions like "Precursor A + Precursor B → Intermediate C" [28]. |

| Active Learning Agent | The core ARROWS3 algorithm that integrates thermodynamic data with experimental results to propose new, optimized experiments. | Proposes precursors that avoid intermediates with low driving force (∆G') to the target [26] [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when using data-driven methods to recommend material precursors. These guides integrate troubleshooting for both computational and experimental workflows.

FAQ 1: Why are my material similarity results inconsistent with established databases?

Question: I am using a computational framework to find materials similar to my target, but the suggested precursors have different symmetry or lattice parameters compared to what is listed for the same material in the Materials Project (MP) database. What could be causing this?

Answer: Inconsistencies often arise from differences in how crystal structures are analyzed and reported. Key factors to check are:

- Symmetry Tolerance (

symprec): Space-group assignments can vary based on the symmetry tolerance used during analysis. The MP database uses a tolerance ofsymprec = 0.1. If your local analysis tool (e.g., pymatgen or VESTA) uses a smaller tolerance (e.g.,symprec = 0.01), it might assign a lower, less symmetric space group to the same structure [30]. - Choice of Unit Cell: The same crystal can be represented by a primitive cell (fewest atoms) or a conventional cell (often easier to visualize). Ensure you are comparing the same cell type, as their lattice parameters will differ [30].

- Systematic Computational Errors: DFT calculations, particularly those using the PBE functional, can systematically overestimate lattice parameters by 1-3%. This error is more pronounced in layered crystals due to the poor description of van der Waals interactions [30].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Identify the Discrepancy: Note the specific property that is inconsistent (e.g., space group number, lattice parameter

a, volume). - Verify Your Settings: Check the

symprecparameter in your local symmetry-analysis tool and re-run the analysis withsymprec = 0.1to match the MP standard [30]. - Confirm the Cell Type: On the MP material details page, you can export the structure as either a conventional or primitive cell. Ensure you are using the same type as in your workflow [30].

- Benchmark Expectations: For lattice parameters, a difference of ~1-3% may be expected systematic error rather than a problem in your similarity analysis [30].

Question: My precursor recommendation pipeline needs to integrate data from multiple high-throughput databases (e.g., MP, AFLOW, OQMD). However, the calculated properties for the same material, like unit-cell volume, differ across these sources, causing errors in my similarity assessment. How should I handle this?

Answer: This is a known challenge in materials informatics. Differences arise from variations in computational parameters even when the same underlying theory (e.g., DFT-PBE) is used. These can include the plane-wave energy cutoff, pseudopotentials, and relaxation schemes [31]. One study noted volume differences of up to 2 ų for simple NaCl structures across different databases, all calculated with VASP using PBE [31].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Acknowledge the Variation: Understand that some level of discrepancy is inherent when merging data from different sources. Document the sources and their known computational settings.

- Use a Standardization Framework: Employ a Python framework like MADAS, designed to handle heterogeneous materials data. Its

Databaseclass provides a unified interface to download data from different sources, converting them into a common internal format that your analysis pipeline can use consistently [31]. - Focus on Relative Similarity: Ensure your similarity measure is robust to small systematic offsets. The goal is to identify materials that are relatively similar across a consistent set of descriptors, not to match absolute property values exactly.

- Establish a Baseline: When working with a new set of elements or crystal classes, manually compare data for a few well-known materials from your different sources to quantify the typical variance, and use this to inform your similarity thresholds.

FAQ 3: What should I do if my data-driven precursor recommendation fails to yield synthesizable materials?

Question: The computational similarity model suggested a list of promising precursors, but initial synthesis attempts failed to produce the target material. How can I troubleshoot this?

Answer: This is a common hurdle where computational stability does not always equate to experimental synthesizability. This can be due to kinetic barriers, complex reaction pathways, or unaccounted-for experimental conditions.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Stability Predictions: Confirm the predicted stability of your target material. Advanced models like GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) provide improved stability predictions by scaling up deep learning with active learning. Check if your target is listed among the millions of stable structures discovered by such large-scale efforts [32].

- Check for Experimental Realization: Some databases indicate if a computationally predicted material has been independently synthesized. For example, 736 of the GNoME-discovered stable structures had already been experimentally realized, providing a stronger validation of their synthesizability [32].

- Refine Your Similarity Criteria: The initial similarity search might have over-emphasized a single property (e.g., crystal structure). Incorporate additional descriptors related to synthesis, such as the energy above the convex hull, or use machine learning models that explicitly predict synthesis conditions [32].

- Implement a Closed Loop: Adopt an autonomous workflow where computational recommendations guide initial experiments, and experimental outcomes (success or failure) are fed back to refine the recommendation model. This iterative process, as discussed in talks on autonomous materials research, helps the model learn the complex rules of synthesizability [33].

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Works

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a Similarity Framework Against Multiple Databases

This methodology is adapted from the MADAS framework publication [31].

Objective: To validate a materials similarity framework by quantifying property differences for the same material across multiple high-throughput databases.

Materials:

- Python environment with the

MADASpackage installed. - Access to the AFLOW, Materials Project (MP), and Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) via their respective APIs.

Methodology:

Data Acquisition:

- Use the

MADASDatabaseclass to implement interfaces for AFLOW, MP, and OQMD. - Download the crystal structure and calculated properties (e.g., unit-cell volume) for a simple, well-known compound like NaCl from all three databases. The

MADASframework will convert the data into a common internal format [31].

- Use the

Structural Equivalence Verification:

- To ensure you are comparing identical polymorphs, verify the structural equivalence using a method like the one implemented in the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE). This confirms that the symmetry and atomic positions are equivalent despite potential differences in lattice parameter reporting [31].

Property Comparison and Analysis:

- Extract the unit-cell volume for each NaCl entry.

- Calculate the absolute and relative differences between the volumes reported by the different databases.

- The expected outcome, as per the referenced study, is a variance of up to 2 ų for NaCl, attributable to differences in computational parameters like plane-wave cutoff [31].

Protocol 2: Active Learning for Improved Stability Prediction

This methodology is based on the GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) discovery pipeline [32].

Objective: To iteratively improve a deep learning model's ability to predict stable crystals, thereby enhancing the quality of precursor recommendations.

Materials:

- A graph neural network (GNN) architecture for predicting crystal energies.

- Initial training data (e.g., a snapshot of ~69,000 materials from the Materials Project).

- Access to DFT computation resources (e.g., VASP) for structure relaxation.

Methodology:

Candidate Generation:

- Generate a diverse pool of candidate crystal structures. The GNoME approach uses two parallel frameworks:

Model Filtration:

- Use the current GNN model to predict the energy and stability (decomposition energy) of all candidates.

- Filter out the candidates predicted to be unstable, retaining only the most promising ones for DFT verification.

DFT Verification and Active Learning:

- Perform DFT calculations to relax the filtered structures and compute their accurate energies.

- Compare the DFT results with the model's predictions. The new, verified stable structures are added to the training dataset.

- Retrain the GNN model on this expanded, higher-quality dataset. This iterative process (steps 1-3) progressively improves the model's accuracy and "hit rate" (the percentage of predicted stable materials that are verified by DFT) [32].

Research Reagent Solutions & Key Computational Descriptors

The following table details key computational tools and concepts essential for building a data-driven precursor recommendation system.

| Item Name | Type/Function | Brief Explanation of Role |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Machine Learning Model | A deep learning model that operates on graph data. It represents a crystal structure as a graph (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) to predict material properties like stability and energy, enabling high-throughput screening [32]. |

| Descriptor | Data Representation | A numerical representation of a material's atomic configuration or properties (e.g., SOAP descriptor). It converts complex structural information into a format usable by machine learning models for similarity comparison [31]. |

| Similarity Measure (Kernel) | Analysis Function | A function that quantifies the similarity between two material descriptors, outputting a score between 0 (completely different) and 1 (identical). It is the core metric for ranking precursor candidates [31]. |

| material_id / mp-id | Database Identifier | A unique identifier (e.g., mp-804) for a specific material polymorph in the Materials Project database. It allows consistent referencing of a material across different studies and calculations [30]. |

| task_id | Database Identifier | A unique identifier for an individual calculation task (e.g., mp-1234567). A single material_id can be associated with multiple task_ids from different calculations [30]. |

| Stability (vs. convex hull) | Energetic Property | A material's decomposition energy relative to competing phases. A negative value indicates the material is thermodynamically stable. It is a key filter for judging viable precursors [32]. |

Workflow Visualization for Precursor Recommendation

The diagram below illustrates the automated, iterative workflow for data-driven precursor recommendation, integrating computational screening with experimental validation.

The solid-state synthesis of multicomponent inorganic materials, crucial for technologies from battery cathodes to solid-state electrolytes, is often hampered by a fundamental challenge: the formation of undesired impurity phases. These by-products kinetically trap reactions in incomplete, non-equilibrium states, preventing the formation of high-purity target materials. Traditional synthesis approaches, which typically involve combining simple oxide precursors, frequently result in low-yield reactions due to the complex energy landscapes of high-dimensional phase diagrams.

Recent research has revealed that solid-state reactions between three or more precursors initiate at the interfaces between only two precursors at a time. The first pair of precursors to react often forms stable intermediate by-products, consuming much of the total reaction energy and leaving insufficient driving force to complete the transformation to the target material. This insight has led to the development of a thermodynamic strategy for navigating multidimensional phase diagrams by focusing specifically on pairwise reaction analysis to identify precursor combinations that circumvent low-energy competing phases while maximizing the reaction energy to drive fast phase transformation kinetics.

Fundamental Principles of Pairwise Reaction Analysis

Core Theoretical Framework

Pairwise reaction analysis operates on several key principles derived from thermodynamic considerations of phase diagrams:

- Principle 1: Initiate with Two Precursors - Reactions should begin between only two precursors whenever possible, minimizing the chances of simultaneous pairwise reactions between three or more precursors that could form multiple impurity phases.

- Principle 2: Utilize High-Energy Precursors - Precursors should be relatively high in energy (unstable), maximizing the thermodynamic driving force and thereby enhancing reaction kinetics to the target phase.

- Principle 3: Target Deepest Hull Point - The target material should represent the deepest point in the reaction convex hull, ensuring the thermodynamic driving force for its nucleation exceeds that of all competing phases.

- Principle 4: Minimize Competing Phases - The composition slice formed between the two precursors should intersect as few competing phases as possible, reducing opportunities for undesired by-product formation.

- Principle 5: Maximize Inverse Hull Energy - When by-product phases are unavoidable, the target phase should have a relatively large inverse hull energy, meaning it sits substantially lower in energy than neighboring stable phases in composition space.

These principles work together to guide researchers toward precursor selections that avoid kinetic traps and favor direct routes to target materials. When multiple precursor pairs could synthesize the target compound, priority is given first to ensuring the target is at the deepest point of the convex hull (Principle 3), followed by maximizing inverse hull energy (Principle 5), as this supersedes the need for a large reaction driving force alone.

Illustrative Case Study: LiBaBO₃ Synthesis

The synthesis of lithium barium borate (LiBaBO₃) demonstrates the power of this approach. When using traditional simple oxide precursors (B₂O₃, BaO, and Li₂CO₃, which decomposes to Li₂O), the reaction energy is substantial at ΔE = -336 meV per atom. However, numerous low-energy ternary phases along the Li₂O-B₂O₃ and BaO-B₂O₃ binary slices form rapidly as intermediates, consuming most of the driving force. The subsequent reaction from these intermediates to the target LiBaBO₃ possesses minimal energy (as low as ΔE = -22 meV per atom), resulting in poor phase purity.

In contrast, when using the high-energy intermediate LiBO₂ as a precursor paired with BaO, the direct reaction LiBO₂ + BaO → LiBaBO₃ proceeds with a substantial reaction energy of ΔE = -192 meV per atom. Furthermore, this reaction slice presents fewer competing phases with smaller formation energies. Experimental validation confirms this pathway produces LiBaBO₃ with significantly higher phase purity compared to traditional precursors.