Optimizing Nucleation in Microwave Plasma Reactors: A 2025 Guide for Advanced Materials Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on optimizing nucleation processes in microwave plasma reactors, a critical step for synthesizing high-quality materials like diamond films and carbon...

Optimizing Nucleation in Microwave Plasma Reactors: A 2025 Guide for Advanced Materials Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on optimizing nucleation processes in microwave plasma reactors, a critical step for synthesizing high-quality materials like diamond films and carbon nanomaterials. It covers the fundamental principles of plasma-nucleation interactions, explores advanced methodological approaches for process control, details practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common challenges, and reviews modern validation techniques. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest 2025 research and diagnostic methods, this guide serves as a vital resource for improving reproducibility, efficiency, and material quality in biomedical and clinical applications, from thermal management materials to next-generation electronic devices.

Understanding Plasma-Nucleation Fundamentals: From Theory to Reactive Species

{#role-microwave-plasma-nucleation-activation}

The Role of Microwave-Generated Plasma in Nucleation Activation

Microwave-generated plasma represents a advanced method for activating and controlling nucleation processes, which are critical in materials science and pharmaceutical development. This non-equilibrium plasma technique enables highly efficient energy transfer, preferentially exciting vibrational modes of gas molecules to drive chemical reactions and nucleation at lower bulk temperatures than traditional thermal methods. Within the context of optimizing nucleation in microwave plasma reactor research, this technology offers unprecedented control over reaction pathways, allowing for the precise manipulation of nucleation kinetics and the production of materials with tailored properties. The application of microwave plasma is particularly transformative for the synthesis of high-value materials, including pharmaceutical compounds and high-purity diamond coatings, where control over crystal structure, purity, and morphology is paramount [1] [2].

The core advantage of microwave plasma lies in its ability to create a strong non-equilibrium state. In this state, free electrons, accelerated by the oscillating microwave electric field, collide with gas molecules. Due to the significant mass difference, these collisions efficiently pump energy into the vibrational modes of the molecules rather than increasing the translational temperature. This results in a high vibrational temperature (several thousand degrees Celsius) while maintaining a substantially lower gas temperature (below one thousand degrees Celsius). This vibrational overpopulation is crucial for efficiently driving endothermic reactions, such as the dissociation of stable molecules like CO₂, N₂, and CH₄, which serve as key precursors in nucleation processes [2].

Theoretical Foundations and Nucleation Kinetics

Classical Nucleation Theory in Plasma Environments

The nucleation rate in solutions, based on Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT), is expressed in the Arrhenius form, governed by the interfacial energy and a pre-exponential nucleation factor. The nucleation rate (J) is given by: [ J = AJ \exp\left[ -\frac{16\pi vm^2 \gamma^3}{3k_B^3 T^3 \ln^2 S} \right] ] where:

- (A_J) is the pre-exponential factor, related to the rate at which solute molecules attach to a forming cluster.

- (\gamma) is the interfacial energy, the energy required to create a new solid-liquid interface.

- (v_m) is the molecular volume.

- (k_B) is the Boltzmann constant.

- (T) is the temperature.

- (S) is the supersaturation ratio [3].

Microwave plasma directly influences these kinetic parameters. The intense vibrational excitation provided by the plasma can lower the effective activation energy barrier for nucleation, primarily by reducing the interfacial energy (\gamma) and enhancing the pre-exponential factor (A_J) through more frequent and effective molecular collisions [2] [3].

Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) and Induction Time

The Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) and induction time are two critical measurements for determining nucleation kinetics. The MSZW is defined as the maximum undercooling (( \Delta Tm = T0 - Tm )) a solution can withstand before nucleation occurs during cooling, while the induction time ((ti)) is the time elapsed from achieving supersaturation to the first appearance of a nucleus at a constant temperature. Both are stochastic and can be described by cumulative distribution functions. A linearized integral model allows for the determination of (\gamma) and (AJ) from MSZW data by plotting ((T0 / \Delta Tm)^2) against (\ln(\Delta Tm / b)), where (b) is the cooling rate [3].

Table 1: Key Nucleation Kinetic Parameters Obtainable from MSZW and Induction Time Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Relationship to Nucleation | Impact of Microwave Plasma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interfacial Energy ((\gamma)) | Energy required to create a new solid-liquid interface. | Lower (\gamma) reduces the energy barrier for nucleation, increasing the nucleation rate. | Vibrational excitation can reduce the effective interfacial energy. |

| Pre-exponential Factor ((A_J)) | Related to the molecular attachment frequency to a nucleus. | Higher (A_J) leads to a higher nucleation rate. | Enhanced molecular collision frequency and energy in the plasma phase increase (A_J). |

| Supersaturation ((S)) | Ratio of actual solute concentration to equilibrium solubility. | The primary driving force for nucleation; higher (S) drastically increases (J). | Plasma chemistry can create highly reactive radicals, effectively increasing local supersaturation. |

Experimental Protocols for Microwave Plasma Reactors

Protocol: Microwave Plasma Reactor Setup for Nucleation

This protocol details the setup and ignition of a flowing microwave plasma reactor for nucleation studies, adapted from methodology used for CO₂ reduction [2].

- Waveguide Assembly: Connect a 1 kW magnetron to a circulator with an attached water load. Connect the circulator to a three-stub tuner for impedance matching of the waveguide to the plasma.

- Applicator and Reactor Tube: Attach the microwave applicator to the three-stub tuner and add a sliding short to the end of the waveguide. Place a quartz tube (e.g., 17 mm or 27 mm inner diameter) through the hole in the applicator. This tube will contain the flowing process gas.

- Vacuum and Gas System: Connect the quartz tube to KF-flanges and a gas inlet. Use a tangential gas inlet to induce a vortex flow, which stabilizes the plasma and prevents the hot core from touching and damaging the tube walls.

- Pressure Control: Connect a throttle valve in series with the vacuum pump to regulate system pressure from 5 mbar to atmospheric pressure. Install a shortcut valve in parallel with the throttle valve to facilitate plasma ignition at low pressure before switching to the desired operating pressure.

- Gas Flow Regulation: Connect a mass flow controller to the gas inlet to precisely regulate gas flow, typically between 0.5 and 10.0 standard liters per minute (SLM).

- Cooling and Safety: Turn on the water cooling for the magnetron. Enable critical safety systems, including a microwave radiation meter and an ambient gas detector for CO, H₂, or NOₓ.

- Plasma Ignition and Tuning: Turn on the microwave power and increase to the desired level. Adjust the sliding short and the three-stub tuners while monitoring the reflected power, aiming to minimize it. This process optimizes power transfer to the plasma. If available, use a network analyzer for more precise tuning [2].

Protocol: Determining Nucleation Kinetics using MSZW

This protocol describes a method for determining nucleation kinetics from Metastable Zone Width measurements, based on the linearized integral model [3].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a saturated solution of the target material (e.g., isonicotinamide, butyl paraben) at a known initial temperature (T_0).

- Experimental Procedure: For a fixed initial saturation temperature (T0), subject the solution to a constant cooling rate (b). Record the nucleation temperature (Tm) at which the first crystals are detected. This defines the MSZW as (\Delta Tm = T0 - T_m).

- Replication and Statistics: Repeat this experiment a large number of times (e.g., 50-100) under identical conditions to account for the stochastic nature of nucleation.

- Data Analysis: a. Construct a cumulative distribution of the detected nucleation events versus (Tm) or (\Delta Tm). b. Determine the median nucleation temperature (Tm) (or median (\Delta Tm)) from the 50% point on the cumulative distribution. c. Repeat steps 2-4 for different cooling rates (b).

- Kinetic Parameter Calculation: a. For each cooling rate, calculate the corresponding ((T0 / \Delta Tm)^2) and (\ln(\Delta Tm / b)) values. b. Plot ((T0 / \Delta Tm)^2) versus (\ln(\Delta Tm / b)). c. The slope and intercept of the resulting straight line are used to calculate the interfacial energy (\gamma) and the pre-exponential factor (A_J), respectively, using Equation (11) from the theoretical derivations [3].

Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The successful implementation of microwave plasma nucleation requires specific reagents and materials designed to withstand harsh conditions and facilitate precise control.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Application in Microwave Plasma Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Process Gases | Gases such as H₂, CH₄, CO₂, N₂, and Ar, with high purity (>99.995%). | Serve as precursors and plasma feed gas. Purity is critical to avoid contamination that can poison nucleation sites. |

| Quartz Reactor Tubes | Fused silica tubes with high thermal shock resistance and microwave transparency. | Contains the plasma and process gases. Its transparency allows microwave energy to couple efficiently into the gas. |

| Substrate Materials | Materials like silicon wafers, molybdenum, or tungsten. | Surfaces upon which nucleation and film growth occur. Material choice affects adhesion and crystal orientation. |

| Insulating Quartz Plates | Custom-designed quartz plates placed underneath the substrate. | Used for thermal management to distribute thermal loads evenly across the substrate, crucial for uniform large-area deposition [1]. |

| Tangential Gas Inlet | A gas inlet designed to create a vortex flow pattern within the reactor tube. | Stabilizes the plasma position, prevents wall contact, and improves mixing of precursor gases [2]. |

| Three-Stub Tuner & Sliding Short | Impedance matching components in the microwave waveguide system. | Minimize reflected microwave power, ensuring efficient and stable plasma operation and protecting the magnetron [2]. |

Optimization of Reactor Parameters for Uniform Nucleation

Optimizing reactor parameters is essential for achieving uniform nucleation over large areas, a critical requirement for industrial applications. Research on diamond film growth in a 915 MHz microwave plasma CVD reactor has demonstrated the profound influence of key parameters on substrate temperature uniformity, which directly dictates nucleation and coating uniformity [1].

- Microwave Power: Microwave power directly influences plasma size, shape, and substrate temperature. An optimum, moderate power level is necessary to create a uniform plasma ball. For example, in a specific 915 MHz system, a power of 9000 W resulted in a minimal temperature variation (ΔT) of 101 °C over a 100 mm diameter substrate, leading to uniform diamond coating. Power levels that are too high or too low can create asymmetric plasma and large thermal gradients, causing non-uniform nucleation and film thickness [1].

- Chamber Pressure: Pressure plays a critical role in tuning the plasma dimensions. An optimum pressure (e.g., 110 Torr in a specific system) generates a stable, hemispherical plasma that uniformly heats the substrate. Deviations from this optimum pressure can lead to a smaller, concentrated plasma or an unstable, swirling plasma, both of which degrade temperature and nucleation uniformity [1].

- Substrate Thermal Management: Active management of the substrate thermal profile is a key strategy. The use of a thicker substrate wafer combined with an underlying insulating quartz plate designed to distribute heat evenly has been shown to significantly reduce thermal gradients. This direct intervention in thermal management is vital for growing uniform polycrystalline diamond films over large areas [1].

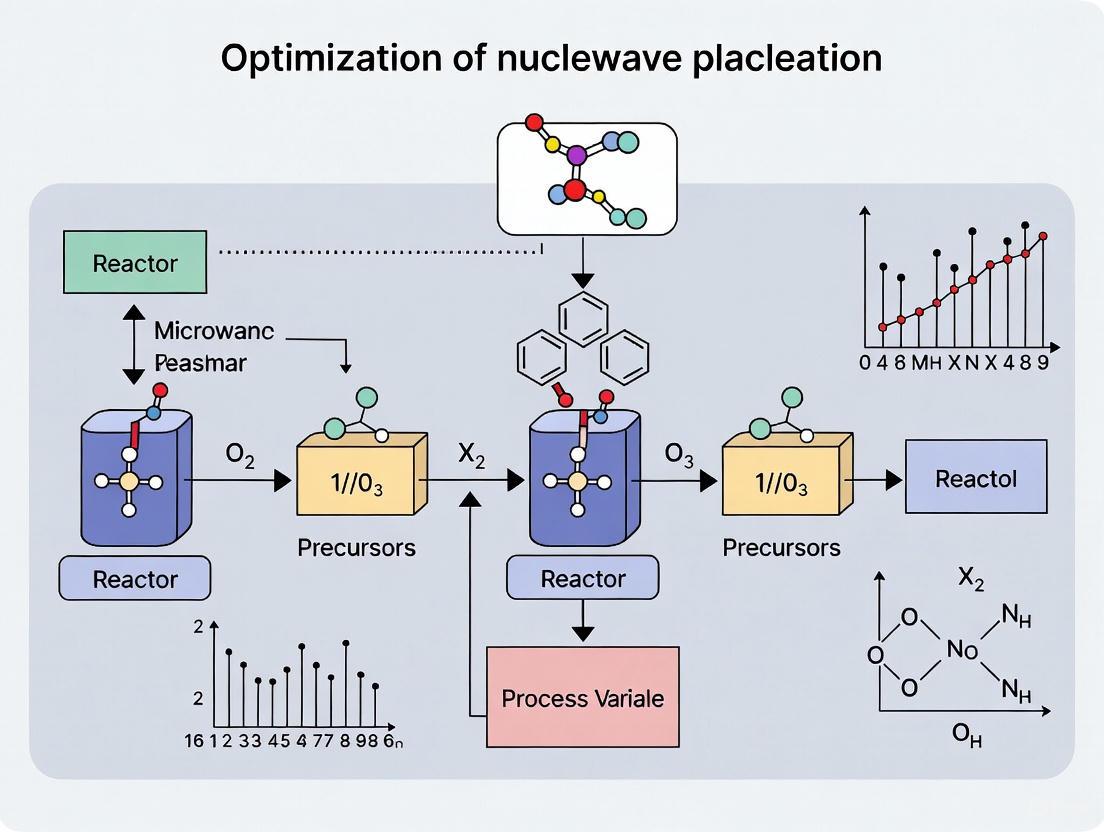

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for optimizing a microwave plasma CVD reactor to achieve uniform nucleation and coating.

Advanced Diagnostics and In-Situ Monitoring

Advanced diagnostic techniques are indispensable for understanding and controlling the non-equilibrium chemistry within a microwave plasma reactor. Laser Rayleigh scattering is a powerful method for measuring the local gas temperature, a parameter critical for understanding nucleation kinetics. The technique involves focusing a high-power laser into the plasma and measuring the intensity of the elastically scattered light from gas molecules. The gas temperature (T) is related to the Rayleigh intensity (I) via: [ T = \frac{p}{I} \frac{d\sigma}{d\Omega}(T) C ] where (p) is the pressure, (d\sigma/d\Omega(T)) is the temperature-dependent Rayleigh cross section, and (C) is a calibration constant. This method provides localized temperature measurements, which is vital given the steep temperature gradients (from ~4,000 K at the center to ~500 K at the walls) in such reactors [2].

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is another key diagnostic tool used to characterize the internal vibrational excitation of molecules in the plasma (in-situ) and to analyze the composition of the effluent gas. For example, in CO₂ reduction experiments, FTIR is used to determine the conversion factor (\alpha) to CO by monitoring the spectral signatures of CO and CO₂. The combination of laser diagnostics for temperature and FTIR for chemistry provides a comprehensive picture of the plasma state, enabling researchers to correlate specific plasma conditions with nucleation outcomes [2].

Key Reactive Species and Energy Transfer Mechanisms in the Nucleation Zone

Within the context of optimizing nucleation in microwave plasma reactor research, a detailed understanding of the key reactive species and energy transfer mechanisms in the nucleation zone is paramount. This region, where precursor molecules transform into solid-phase nuclei, dictates the characteristics of the resulting nanomaterials. Microwave Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition (MPCVD) is a preferred method for producing high-quality materials like diamond films and graphene due to its electrodeless discharge, low contamination risk, and excellent process controllability [4]. The plasma, sustained by microwave energy, creates a unique environment where precursor molecules are fragmented into highly reactive species, initiating the nucleation process. This document details the critical reactive species, elucidates the fundamental energy transfer pathways, and provides standardized protocols for probing the nucleation zone, serving as a vital resource for researchers and engineers in the field.

Key Reactive Species in Plasma Nucleation

The nucleation zone is a dynamic environment populated by a complex mixture of species derived from the precursor gas. The identity and behavior of these species are critical for the nucleation mechanism, which can follow classical or non-classical pathways, including those involving prenucleation clusters [5].

Table 1: Key Reactive Species in the Nucleation Zone for Carbon-Based Materials.

| Species Category | Example Species | Role in Nucleation Process | Experimental/Observational Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Precursors | CH₄, C₂H₂, CO₂, H₂ | Source of carbon and process gas; H₂ is critical for etching non-diamond carbon and generating atomic hydrogen. | High methane flow rates can lead to larger particle sizes with higher defect densities [6]. |

| Radical Intermediates | Methyl radicals (CH₃), C₂H | Key growth species for diamond; C₂H is implicated in soot and graphene growth via addition reactions. | Dominant species are dependent on plasma conditions (pressure, power, gas mixture). |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Pyrene (A4), Coronene, Ovalene | Act as molecular precursors for soot nucleation; can physically stack or chemically link to form initial particles. | Smaller PAHs (e.g., Pyrene) cannot nucleate homogeneously at ~1000 K without larger PAHs present [7]. |

| Stable Gas-Phase Products | C₂H₂, C₄H₂, H₂ | C₂H₂ is a major product of CH₄ dissociation and a key reactant for surface growth via HACA mechanism. | In soot formation, C₂H₂ addition directly to PAHs without prior H-abstraction (CAHM mechanism) can be important [7]. |

| Energetic Species | Electrons, Ions, Excited Species | Dissociate precursor molecules, generate radicals, and provide activation energy for chemical reactions. | The electron energy distribution function (EEDF) is critical for understanding dissociation pathways [4]. |

The nucleation pathway is highly sensitive to temperature and the presence of specific species. At relatively low temperatures (e.g., ~1000 K), homogeneous nucleation of small PAHs like pyrene is thermodynamically unfavorable, as the free energy of dimerization is smaller than the average kinetic energy [7]. However, the introduction of larger PAHs (e.g., ovalene) enables heterogeneous nucleation, where small PAHs aggregate around the larger ones to form clusters [7]. At higher temperatures (~1500 K), chemical bonding between species becomes the dominant nucleation mechanism. This can occur through pathways like the H abstraction C₂H₂ addition (HACA) mechanism, or via the Carbon Addition Hydrogen Migration (CAHM) mechanism, where carbon adds directly to a PAH without the initial H-abstraction step [7]. In air plasma environments, the formation and destruction of NOx species in the downstream quenching region are also critical and are governed by complex reaction kinetics tied to energy transfer [8].

Energy Transfer Mechanisms

The efficient coupling of microwave energy into the plasma and its subsequent transfer to different energy modes is the driving force behind nucleation. A steady-state multiphysics model that self-consistently couples the microwave field with plasma properties (electron density, temperature) and gas dynamics is essential for optimizing this process [4].

Microwave Coupling and Electron Heating: Microwaves at 2.45 GHz are incident into the reaction chamber, typically via a waveguide. The electric field accelerates free electrons, which gain energy from the field through inelastic collisions with neutral gas molecules. This energy transfer is most efficient when the reactor geometry is optimized to support specific electromagnetic modes (e.g., TM01 and TM02) that create a large, uniform electric field above the substrate, enabling a uniform plasma ball [4]. The energy efficiency of this coupling can exceed 94% in optimized reactors without external tuners [4].

Energy Redistribution and Thermalization: The energized electrons (with temperatures of several eV) do not instantaneously transfer their energy to the heavy particles (ions and neutrals). A multi-temperature model is required to describe the system, where the electron temperature (Te) is much higher than the gas and vibrational temperatures (Tg, T_v) in a non-thermal plasma [8]. The subsequent energy transfer follows a cascade:

- Electron-Impact Excitation/Vibration: Energetic electrons excite molecules, primarily into vibrational states (e.g., N₂(v) and O₂(v) in air plasma).

- Vibrational-Translational (V-T) Relaxation: The excited vibrational energy is then slowly transferred to translational (heat) modes of the gas, a process that governs the gas temperature in the post-discharge (quenching) region.

- Chemical Kinetics: The rate coefficients for chemical reactions involved in nucleation and NOx formation are strongly dependent on these temperatures, often determined by a generalized Fridman-Macheret scheme for non-thermal conditions [8].

The Critical Role of Quenching: The rapid cooling or quenching of the gas after the plasma zone is critical for "freezing" the desired chemical products and preventing their back-reaction. The quenching process, often modeled as a Plug Flow Reactor (PFR), tracks the relaxation of temperatures and the evolution of reaction pathways as the gas cools [8]. The cooling rate is a key parameter that can be controlled to optimize the yield of target nuclei.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Probing Nucleation Pathways in a MPCVD Reactor

Objective: To identify the dominant reactive species and map the nucleation sequence for carbon nanomaterial synthesis under specific plasma conditions.

Materials:

- MPCVD reactor (e.g., 2.45 GHz, TM01/TM02 hybrid-mode) [4].

- Precursor gases: CH₄, H₂, Ar.

- In-situ optical emission spectroscopy (OES) system.

- Particle sampling probe arms [6].

- Ex-situ analysis: Raman spectroscopy, BET surface area analysis, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

Procedure:

- Reactor Stabilization: Evacuate the chamber and backfill with H₂. Ignite the plasma at the target power (e.g., 1.5-3 kW) and pressure (e.g., 30-100 Torr) [4]. Stabilize for 10 minutes.

- Introduction of Precursor: Introduce CH₄ at a defined flow rate (e.g., 1-10 sccm) to establish a specific CH₄/H₂ ratio.

- In-situ OES Measurement: Use OES to collect spectra from the plasma core and the nucleation zone (downstream). Monitor for key species: CH⁺ (431.4 nm), C₂ (516.5 nm), Hα (656.3 nm), and Hβ (486.1 nm). Record intensities as a function of axial position from the plasma core.

- Spatially-Resolved Particle Sampling: Use a sampling probe arm at various axial and radial positions to collect nucleated particles from the gas phase [6].

- Ex-situ Particle Analysis:

- Data Correlation: Correlate the OES data (gas-phase species) with the properties of the particles collected at the same location to build a nucleation pathway map.

Protocol: Quantifying the Effect of Reactor Geometry on Plasma Uniformity

Objective: To optimize the reactor geometry for a uniform plasma and nucleation zone using multiphysics simulation and experimental validation.

Materials:

- 3D Finite Element Method (FEM) software (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics).

- MPCVD reactor with modular components (e.g., replaceable matcher, substrate stage) [4].

Procedure:

- Baseline Simulation: Create a 2D axisymmetric or 3D model of the reactor. Define the computational domain and set up the physics interfaces: Electromagnetic Waves (Frequency Domain), Plasma Transport, and Heat Transfer [4] [9].

- Define Plasma Chemistry: Input a set of reactions for the precursor gas (e.g., pure H₂ or H₂/CH₄ mixture) into the model [4].

- Parameter Sweep: Perform a parameter sweep of key geometric variables, such as the height (

H_M) and diameter (D_M) of the impedance matcher, and the outer diameter of the coaxial conductor [4]. - Evaluate Performance: For each geometric configuration, simulate and extract:

- Microwave Energy Efficiency: Percentage of incident power absorbed by the plasma.

- Electric Field Uniformity: Standard deviation of the |E|-field above the substrate.

- Electron Density Distribution: The density and uniformity of the plasma (e.g., target ~5e17 m⁻³) [9].

- Experimental Validation: Manufacture the optimized matcher geometry identified in Step 4. Install it in the physical MPCVD system and experimentally reproduce the simulated conditions. Visually assess plasma size and uniformity, and measure the reflected power to confirm high energy efficiency.

Table 2: Key Operational Parameters for MPCVD Nucleation Studies.

| Parameter | Typical Range / Value | Impact on Nucleation Zone | Measurement/Control Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave Power | 80 W - 3 kW | Higher power increases plasma density, dissociation rate, and gas temperature, promoting nucleation. | Directional power meter (incident/reflected). |

| System Pressure | 75 mTorr - 100+ Torr | Affects plasma volume, species diffusion, and reaction rates. Low pressure (~75 mTorr) favors uniform, low-density plasma [9]. | Capacitance manometer, Pirani gauge. |

| CH₄ in H₂ | 1% - 10% | Higher methane concentration generally increases nucleation rate and can lead to higher defect densities [6]. | Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs). |

| Gas Temperature (T_g) | 1000 K - 3000 K (est.) | Governs reaction kinetics and phase transitions; critical for quenching. | Optical methods (e.g., FTIR), thermocouple (external). |

| Substrate Temperature | 600 °C - 1200 °C | For substrate-bound growth, affects surface mobility and incorporation of species. | Pyrometer. |

| Quenching Rate | Variable | A faster cooling rate "freezes" the nucleation products, preventing Ostwald ripening or back-reaction [8]. | Controlled by heat exchanger, flow rate. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Plasma Nucleation Studies.

| Item | Function / Role | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| MPCVD Reactor | Generates and sustains the microwave plasma for precursor dissociation and nucleation. | 2.45 GHz systems are preferred for energy consumption and plasma density; hybrid-mode (TM01+TM02) reactors enable larger, uniform plasma [4]. |

| Process Gases | Act as carbon precursors and plasma medium. | CH₄ (carbon source), H₂ (etchant and radical generator), Ar (plasma stabilizer), CO₂ (for dry reforming studies) [6] [10]. |

| Quartz Windows / Rings | Electrically isolates the plasma from the waveguide while allowing microwave transmission. | High-purity quartz is critical to prevent contamination; geometry can be optimized for plasma confinement [9]. |

| Multiphysics Simulation Software | Models the coupled electromagnetic fields, plasma chemistry, and heat transfer to optimize reactor design. | Used for virtual parameter sweeps of geometry and operating conditions, reducing costly experimental trials [4] [9]. |

| Optical Emission Spectrometer (OES) | Provides non-invasive, real-time monitoring of radical and ionic species in the plasma. | Identifies key reactive species like CH, C₂, and H atoms, correlating their presence with nucleation outcomes. |

| Spatial Sampling Probes | Allows for the extraction of nucleated particles from specific locations within the nucleation zone. | Enables mapping of particle size and structure evolution (e.g., diameter increases with distance from core) [6]. |

| Raman Spectrometer | Characterizes the quality and structure of synthesized carbon materials. | D/G band ratio quantifies defect density in graphene and soot; sharp peak indicates high crystallinity in diamond [6]. |

| Quenching Control System | Rapidly cools the post-plasma gas to stabilize nucleation products. | A plug flow reactor (PFR) model can be used to design and analyze this critical step [8]. |

Influence of Reactor Geometry on Plasma Stability and Initial Film Formation

The optimization of nucleation processes in microwave plasma reactor research is critically dependent on reactor geometry, which directly governs plasma stability, species transport, and initial film formation. Geometric parameters including electrode configuration, cavity resonance modes, and substrate positioning fundamentally influence the dissociation of precursor gases, the formation of critical nuclei, and the subsequent growth of uniform thin films. This application note provides a structured framework of quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to guide researchers in manipulating reactor geometry to control nucleation outcomes for advanced materials synthesis in applications ranging from semiconductor devices to biomedical coatings.

Quantitative Data on Geometric Influence

Table 1: Influence of Electrode Geometry and Position on Plasma Polymerized Acrylic Acid (ppAAc) Film Properties [11]

| Geometric Parameter | Film Thickness (nm) | COOH/R Group Concentration (%) | Aqueous Stability (% Thickness Retention) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perpendicular Electrode (30 mm from electrode) | 120 | 18.2 | 92 |

| Perpendicular Electrode (190 mm from electrode) | 45 | 24.7 | 65 |

| Parallel Electrode (60 mm above stage) | 150 | 15.5 | 96 |

| Parallel Electrode (140 mm above stage) | 95 | 19.1 | 88 |

Table 2: MPCVD Reactor Performance vs. Electromagnetic Mode and Operating Conditions [4]

| Parameter | TM01 Mode | TM01 + TM02 Hybrid Mode | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma Diameter (mm) | 72 | 108 | 102 |

| Maximum Electric Field (V/m) | 6.5×10⁴ | 4.8×10⁴ | - |

| Electric Field Uniformity (%) | 58 | 82 | - |

| Microwave Energy Efficiency at 8 kPa (%) | 78 | 94 | 91 |

| Optimal Pressure Range (kPa) | 4-10 | 6-15 | 6-15 |

Experimental Protocols

Objective: To investigate the effect of parallel vs. perpendicular electrode configurations on the chemistry, thickness, and aqueous stability of plasma polymerized acrylic acid (ppAAc) films.

Materials:

- Custom-built stainless steel T-shaped plasma reactor (16.2 L volume)

- 13.56 MHz RF power generator with impedance-matching network

- Internal aluminium disk electrode (170 mm diameter)

- Acrylic acid monomer (99% purity, Sigma-Aldrich)

- Silicon wafer substrates (8 mm × 8 mm)

Procedure:

- Electrode Configuration:

- For perpendicular geometry: Position electrode vertically perpendicular to samples placed 30-190 mm away

- For parallel geometry: Position electrode horizontally parallel to substrate stage at 60, 105, or 140 mm distance

Substrate Preparation:

- Clean silicon wafers with standard RCA protocol

- Mount substrates on aluminum sample stage elevated 43.5 mm from reactor bottom

Plasma Deposition:

- Degas acrylic acid monomer using three freeze-thaw cycles with liquid nitrogen

- Pump reactor down to base pressure of 1×10⁻³ mbar

- Introduce acrylic acid at 5 sccm flow rate (pressure ≈ 2.7×10⁻² mbar)

- Initiate plasma at 30 W power for 20 min deposition time

- Post-treatment: Maintain monomer flow for 2 min after RF power termination

Aqueous Stability Assessment:

- Immerse coated samples in Milli-Q water for 18 h at room temperature

- Rinse three times with fresh Milli-Q water and dry under nitrogen stream

- Analyze film thickness retention via spectroscopic ellipsometry

- Assess chemical composition changes via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

Objective: To achieve vapor phase nucleation (VPN) of dispersed nanodiamonds by manipulating plasma spatial distribution using molybdenum cylinders.

Materials:

- Home-made MPCVD system (HITLH-2450 M) with 2.45 GHz microwave generator

- Molybdenum cylinder (MoC, φ = 8 mm) and molybdenum disk (MoD) substrate holder

- Hydrogen (99.999%) and methane (99.995%) process gases

- Optical emission spectroscopy (OES) system for plasma monitoring

Procedure:

- Reactor Configuration:

- Install molybdenum cylinder at varying penetration depths (XMo = 3-7 mm)

- Position molybdenum disk substrate holder below plasma region

Plasma State Optimization:

- Maintain chamber pressure at 5 kPa with hydrogen flow rate of 400 sccm

- Apply microwave power of 1300 W to generate concentrated plasma sphere

- Use OES to monitor C₂ and CH radical concentrations (516 nm and 431 nm peaks)

- Optimize MoC position to create distinct dark region between plasma and substrate

Nanodiamond Synthesis:

- Introduce methane precursor at 1-5 sccm flow rate for 30-60 min

- Maintain temperature gradient from ~3500 K (plasma core) to <1000 K (collection region)

- Collect sedimented nanodiamonds from molybdenum disk surface

Characterization:

- Analyze particle size distribution via scanning electron microscopy

- Assess crystal quality and phase purity via Raman spectroscopy

- Determine surface functional groups via Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

Objective: To optimize single-pin electrode configuration in atmospheric pressure plasma reactor for large-area polyaniline (PANI) thin film deposition.

Materials:

- Custom atmospheric pressure plasma reactor (APPR) with glass guide-tube (34 mm OD)

- Tungsten needle electrode (0.5 mm diameter) in capillary glass tube

- Polytetrafluoroethylene bluff-body and substrate holder

- Aniline monomer (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%), argon carrier gas (99.999%)

Procedure:

- Electrode Configuration Testing:

- Case I: Vertical centered electrode parallel to gas-feeding tube

- Case II: Electrode tilted ~50° on guide-tube side, separated from gas-feeding tube

- Case III: Electrode vertically integrated into gas-feeding tube above guide-tube

Plasma Discharge Optimization:

- Apply bipolar sinusoidal voltage (8 kV peak-to-peak, 30 kHz frequency)

- Optimize argon flow rate (1-5 slm) and bluff-body height (5-15 mm)

- Monitor discharge characteristics using ICCD camera and voltage-current sensors

Thin Film Deposition:

- Vaporize aniline monomer using glass bubbler with 400 sccm argon flow

- Deposit films for 30-120 min on glass or silicon substrates

- Maintain substrate temperature below 80°C during deposition

Film Characterization:

- Measure film thickness and uniformity via stylus profiler (multiple locations)

- Analyze surface morphology via field emission scanning electron microscopy

- Identify chemical functional groups via Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

Visualization of Geometric Relationships

Geometric Parameter Impact Pathway: This diagram illustrates the causal relationships between specific reactor geometry modifications and their ultimate effects on nucleation and film properties through intermediate plasma and transport phenomena.

Nanodiamond VPN Experimental Workflow: This workflow details the sequential steps and critical intermediate phenomena in the vapor phase nucleation process for dispersed nanodiamonds, highlighting the role of molybdenum components in creating specialized nucleation zones.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Research Reagents for Plasma Reactor Geometry Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Experiment | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylic Acid Monomer | 99% purity, degassed via freeze-thaw cycles | Carboxylic acid functional group source for plasma polymerization | ppAAc films for biomedical surfaces [11] |

| Molybdenum Cylinder & Disk | High-purity (99.95%), φ = 8 mm cylinder | Plasma spatial distribution control for vapor phase nucleation | Dispersed nanodiamond synthesis [12] |

| Methane Process Gas | 99.995% purity, with hydrogen carrier | Carbon precursor for diamond phase formation | MPCVD diamond growth [12] [13] |

| Aniline Monomer | 99% purity, vaporized via glass bubbler | Conductive polymer precursor for thin film deposition | PANI thin film synthesis [14] |

| Silicon Wafer Substrates | <1-0-0> orientation, 500-550 µm thickness | Standardized substrate for film characterization | Thickness and stability measurements [11] |

| Quartz Reactor Tubes/Windows | High-purity, custom dimensions | Microwave-transparent plasma containment | Atmospheric pressure graphene synthesis [13] |

| Tungsten Needle Electrode | 0.5 mm diameter, glass capillary insulated | High-voltage discharge electrode for AP plasma | Electrode configuration studies [14] |

Comparing Nucleation in Thermal vs. Non-Thermal Microwave Plasmas

Plasma, often referred to as the fourth state of matter, is an ionized gas containing a mixture of ions, electrons, and neutral species. In materials synthesis, plasmas are categorized primarily by their thermal equilibrium states, which fundamentally influence nucleation mechanisms and outcomes. Thermal plasmas (or hot plasmas) exist in a state of thermal equilibrium where ions, electrons, and neutral species all share approximately the same temperature, which can be extremely high (up to 10,000 K). In contrast, non-thermal plasmas (NTP), also known as cold plasmas, are characterized by a non-equilibrium state where electrons possess high temperatures (several electron volts) while ions and neutral species remain near ambient temperature [15] [16].

This thermal dichotomy creates distinct environments for nucleation—the initial phase transition process where solute atoms or molecules in a solution begin to aggregate into nanoscale clusters that become stable nuclei for particle growth. In thermal plasmas, nucleation is predominantly thermally driven, whereas in non-thermal plasmas, nucleation benefits from enhanced chemical reactivity due to high-energy electrons creating abundant active radicals and ionic species without the burden of excessive heat [15] [16]. Understanding these differential nucleation mechanisms is critical for optimizing microwave plasma reactor design and processes for specific material outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of Nucleation Mechanisms

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Thermal vs. Non-Thermal Microwave Plasmas

| Parameter | Thermal Plasma | Non-Thermal Plasma |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Equilibrium | Thermal equilibrium (Te ≈ Tion ≈ Tgas) | Non-equilibrium (Te >> Tion ≈ Tgas) [16] |

| Typical Electron Temperature | ~10,000 K [16] | Several eV (~10,000-100,000 K) [16] |

| Gas Temperature | ~10,000 K [16] | ~300-1000 K (near room temperature achievable) [15] [16] |

| Energy Consumption | High | Relatively low [15] |

| Primary Nucleation Drivers | Thermal energy, homogeneous heating | High-energy electrons, radical-induced reactions, selective energy transfer [15] [16] |

| Typical Applications | Extractive metallurgy, waste destruction, coating techniques [15] | Synthesis of temperature-sensitive nanomaterials, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [15] |

Table 2: Nucleation and Material Outcomes in Different Plasma Regimes

| Aspect | Thermal Plasma | Non-Thermal Plasma |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size Distribution | Broader distribution due to rapid, uncontrolled growth | Narrower distribution from controlled nucleation [16] |

| Crystallinity | High crystallinity but potential for defects at high temperatures | Enhanced crystallinity at low temperatures [15] |

| Morphology Control | Limited due to rapid thermal growth | Superior control enabling complex architectures (3D nanostructures, core/shell) [15] |

| Reaction Kinetics | Fast but thermally limited | Enhanced kinetics from lowered activation energy [16] |

| Representative Materials Synthesized | Metal alloys, ceramics [17] | Metal-organic frameworks, nanocomposites, bare Fe2O3 nanoparticles, core/shell nanoparticles [15] [16] |

The fundamental difference in nucleation behavior between thermal and non-thermal plasmas stems from their disparate energy transfer mechanisms. In thermal plasmas, energy is distributed broadly throughout all species, leading to intense, generalized heating that accelerates both nucleation and growth phases, often resulting in larger particles with broader size distributions [16]. The excessive thermal energy can promote rapid, uncontrolled growth that diminishes control over final particle characteristics.

In non-thermal microwave plasmas, the selective energy transfer to electrons creates a unique environment where nucleation can be selectively enhanced without triggering excessive growth. The high-energy electrons (several eV) generate abundant reactive species through inelastic collisions, facilitating nucleation at significantly lower overall temperatures [16]. This non-thermal environment is particularly advantageous for synthesizing temperature-sensitive materials and achieving narrow particle size distributions through controlled nucleation rates.

Experimental Protocols for Plasma Nucleation Studies

Protocol: Microwave Plasma Synthesis of Mesoporous Selenium Nanoparticles (mSeNPs)

Objective: To synthesize mesoporous selenium nanoparticles using microwave plasma and investigate nucleation dynamics under non-thermal conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Sodium selenite (Na₂SeO₃): Selenium precursor

- Zinc nanopowder (40-60 nm): Hard template for mesoporosity [18]

- Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB): Micellar template and dispersing agent (concentration: 5-10 mM, above critical micelle concentration of 0.92 mM) [18]

- Ascorbic acid (AA): Reducing agent (concentration: 0.5-10 mM) [18]

- Thiol-dPEG4-acid: Surface modifying agent

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl) and ethanol: Template removal solvents

Equipment:

- 5.8 GHz or 2.45 GHz microwave plasma reactor with temperature monitoring (±0.1°C) [18]

- Magnetic stirring system

- Centrifuge

- reflux apparatus

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: Disperse 73 mg CTAB in 16 mL ultra-pure water and allow 30 minutes for micelle formation. Add 10 mg zinc nanopowder and 5 mg PEG-SH to the solution, followed by sonication for 5 minutes. Add 17 mg Na₂SeO₃ and stir for 2 hours to ensure homogeneous distribution [18].

Microwave Plasma Treatment: Transfer 8 mL of the mixture to the microwave plasma reactor. Add 2 mL of ascorbic acid solution (1 mg/mL) as reducing agent. Set the temperature ramp to 60°C/min to reach the reaction temperature of 80°C. Maintain at 80°C for 30 minutes with continuous stirring [18].

Template Removal: Centrifuge the reaction mixture to collect particles. Disperse the pellet in 20 mL of ethanol:HCl mixture (39:1 vol ratio) and reflux at 50°C for 12 hours to remove CTAB and zinc templates. Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes, remove supernatant, and disperse final mSeNPs in water [18].

Key Observations: The 5.8 GHz microwave irradiation demonstrates enhanced non-thermal effects compared to 2.45 GHz systems, promoting the formation of nanorods and branched shapes through modified nucleation and growth kinetics [18].

Protocol: Non-Thermal Plasma Synthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

Objective: To synthesize water-stable MOFs using non-thermal plasma for enhanced nucleation control.

Materials and Reagents:

- Metal precursors: Copper salts (for HKUST-1), Cobalt salts (for Co-MOF)

- Organic linkers: Trimesic acid (for HKUST-1), other linkers as appropriate

- Graphene oxide: For composite formation (if synthesizing Co-MOF-rGO)

- Precursor solution: Appropriate solvent system

Equipment:

- Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) cold plasma reactor [15]

- Alternating Current (AC) power supply (14 kHz, 130 W) [15]

- Standard synthesis vessels

- Characterization equipment (XRD, SEM, surface area analyzer)

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Prepare precursor solution containing metal salts and organic linkers in appropriate stoichiometry. For Co-MOF-rGO nanocomposite, include reduced graphene oxide in the precursor mixture [15].

Plasma Treatment: Place precursor solution in DBD plasma reactor. Generate non-thermal plasma using AC power supply at 14 kHz frequency and 130 W power. Treat for predetermined duration under ambient conditions [15].

Product Isolation: Recover synthesized MOFs by centrifugation or filtration. Wash with appropriate solvents and dry under vacuum.

Key Observations: Plasma-synthesized MOFs (PL-HKUST-1) exhibit significantly higher water stability compared to conventionally synthesized counterparts, maintaining structural integrity after 12 hours of water immersion due to higher Cu(I) content and surface modifications from plasma treatment [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Plasma Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Nucleation Process | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Nanopowder | Hard template for mesopore formation | Creates mesoporous structures in selenium nanoparticles [18] |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide) | Micellar template and capping agent | Controls particle growth and prevents aggregation [18] |

| Ascorbic Acid | Reducing agent | Reduces selenite ions to elemental selenium for nucleation [18] |

| Thiol-dPEG4-acid | Surface modifying agent | Enhances nanoparticle stability and functionality [18] |

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Reactor | Generates non-thermal plasma at atmospheric pressure | Enables low-temperature MOF synthesis [15] |

| Metal-Organic Framework Precursors | Building blocks for porous crystalline materials | Creates tailored porous structures for catalysis, adsorption [15] |

Visualization of Plasma Nucleation Mechanisms

Plasma Nucleation Pathways Diagram

Non-Thermal Plasma Activation Mechanism

The comparative analysis of nucleation in thermal versus non-thermal microwave plasmas reveals distinct advantages of non-thermal systems for controlled nanomaterials synthesis. Non-thermal plasmas enable enhanced nucleation control through selective energy transfer to electrons, resulting in superior morphology control, narrower particle size distributions, and the ability to synthesize temperature-sensitive materials. The experimental protocols outlined provide reproducible methodologies for exploiting these differential nucleation mechanisms, particularly beneficial for synthesizing advanced materials like mesoporous nanoparticles and metal-organic frameworks with enhanced properties and stability.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular-level mechanisms of nucleation in non-thermal plasma environments, optimizing reactor designs for enhanced scalability, and exploring hybrid approaches that combine thermal and non-thermal advantages. The continued development of microwave plasma technologies promises significant advances in nanomaterials design for applications ranging from drug delivery and catalysis to environmental remediation and energy storage.

The Nucleation-in-the-Bulk, Growth-at-the-Boundary framework describes a two-stage mechanism for the formation and development of solid phases from gaseous precursors in a microwave plasma environment. This model is particularly relevant for the synthesis of advanced carbon nanomaterials, such as graphene and diamond films, within Microwave Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition (MPCVD) reactors. In this process, the initial formation of molecular clusters (nucleation) occurs volumetrically within the high-energy plasma core, while subsequent crystal expansion (growth) proceeds primarily at the boundaries of these nascent clusters as they migrate through thermal and concentration gradients [6].

Understanding this framework is fundamental for optimizing reactor design and process parameters in materials synthesis. The spatial decoupling of nucleation and growth stages enables superior control over critical material properties, including particle size distribution, crystallinity, and defect density. Recent research on atmospheric pressure microwave plasma synthesis of graphene supports this model, demonstrating that mean particle diameter increases with distance from the plasma core, consistent with bulk nucleation followed by boundary-growth mechanisms during particle transport [6].

Theoretical Foundations and Governing Principles

Fundamental Nucleation and Growth Kinetics

The nucleation and growth (NAG) process is initiated when a system reaches a supersaturated state, providing the thermodynamic driving force for phase separation. In microwave plasma reactors, this supersaturation is achieved through rapid gas heating and precursor dissociation in the high-temperature plasma zone [19].

- Classical Nucleation Theory: This theory describes nucleation as an atom-by-atom process where monomers form stable clusters (nuclei) that can expand into macroscopic crystals. The smallest subunit of a particle, a monomer, can exist in solution as dissociated ions or complexes [19].

- Growth Mechanisms: Following nucleation, crystal development proceeds through two primary mechanisms:

- Diffusion-controlled growth: Occurs when the concentration of growth monomers falls below the critical concentration required for nucleation, but crystal development continues.

- Surface-process-controlled growth: Dominates when diffusion of growth species from the bulk to the growth surface is sufficiently rapid, making the surface integration process rate-limiting [19].

Multiphysics Interactions in Microwave Plasma Reactors

The NAG process in MPCVD reactors is governed by complex, coupled physical phenomena:

- Electromagnetic Fields: Microwave energy (typically at 2.45 GHz) creates oscillating electric fields that accelerate electrons, generating and sustaining high-temperature plasma [4] [9].

- Plasma Characteristics: Electron collisions with gas atoms and molecules cause ionization, excitation, and dissociation, creating highly reactive species including radicals, ions, and excited-state molecules [20].

- Thermal Gradients: Significant temperature gradients exist between the high-temperature plasma core and cooler reactor boundaries, driving fluid motion and species transport [21].

- Fluid Dynamics: Gas flow patterns, including swirling flows used in some reactor designs, significantly influence residence times and transport of nuclei and growth species [20].

Advanced modeling approaches self-consistently couple these phenomena, enabling prediction of reactor performance and optimization of energy efficiency, which has been demonstrated to exceed 94% in optimized MPCVD systems [4].

Experimental Protocols for Framework Validation

Protocol: Spatial Mapping of Particle Evolution in Microwave Plasma Reactors

Objective: To experimentally validate the nucleation-in-the-bulk, growth-at-the-boundary framework by characterizing the spatial evolution of particle size and crystallinity in an atmospheric pressure microwave plasma reactor.

Materials and Equipment:

- Microwave plasma reactor (atmospheric pressure, 2.45 GHz)

- Gaseous carbon precursors (e.g., methane, ethanol)

- Carrier gases (e.g., argon, hydrogen)

- Spatial sampling probe system

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

- Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area analyzer

- Raman spectroscopy system

Methodology:

- Reactor Setup and Stabilization:

- Configure a straight-tube quartz reactor geometry, which has been shown to favor crystalline, lower-defect structures [6].

- Establish stable plasma operating conditions: 700-2000 W microwave power, 10-50 slm total gas flow, with carbon precursor (e.g., methane) diluted in hydrogen or argon [6] [21].

- Maintain atmospheric pressure operation throughout the experiment.

Spatially-Resolved Sampling:

- Utilize a movable probe arm system to extract material at varying distances from the plasma core center.

- Sample at minimum three distinct positions: (1) within the visible plasma region, (2) at an intermediate position, and (3) near the reactor boundary.

- Ensure isokinetic sampling conditions to prevent bias in collected particle size distributions.

Particle Characterization:

- TEM Analysis: Prepare samples on carbon-coated copper grids and image multiple regions from each sampling location. Measure particle size distributions and characterize morphology and layer structure for carbon nanomaterials [22].

- BET Analysis: Determine specific surface area for powders from each sampling location. Calculate equivalent spherical diameter for comparison with TEM results [6].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Acquire spectra using 532 nm laser excitation. Analyze the D/G band ratio (ID/IG) as a function of position from plasma core to track defect evolution [22] [6].

Data Interpretation:

- Plot mean particle diameter versus distance from plasma core. The nucleation-in-the-bulk, growth-at-the-boundary model predicts a positive correlation [6].

- Correlate crystallinity metrics (ID/IG ratio) with position, expecting improved crystallinity with distance from the high-temperature plasma core.

- Compare size distributions across positions to identify evidence of continuous growth during transport.

Expected Outcomes: Validation of the framework is confirmed by demonstrating increasing mean particle diameter with distance from the plasma core, supported by evolving structural characteristics observable through TEM and Raman spectroscopy [6].

Protocol: In Situ Monitoring of Nucleation Induction Period

Objective: To quantitatively determine the nucleation induction period (t_ind) and initial growth rates during electrochemical deposition of metal hydroxides, providing insights transferable to plasma systems.

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical cell with temperature control

- Cathode substrate (e.g., platinum, stainless steel)

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- In situ microzone pH sensor

- MgCl₂·6H₂O precursor solution

- Data acquisition system

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare 0.5-2.0 M MgCl₂·6H₂O solutions in deionized water [23].

- System Calibration: Calibrate the pH microsensor in standard solutions and position it within 1-2 mm of the cathode surface.

- Electrochemical Deposition:

- Apply constant current density in the range of 10-50 mA/cm².

- Simultaneously record pH and potential at high frequency (≥1 Hz).

- Induction Period Determination:

- Identify tind as the time interval between current application and the first observable deviation in pH or potential.

- Correlate tind with the onset of visible film formation.

- Parameter Optimization:

- Repeat experiments across a matrix of Mg²⁺ concentrations (0.5-2.0 M), current densities (10-50 mA/cm²), and temperatures (25-60°C) [23].

- Construct a multi-parameter synergistic model of "Mg²⁺ concentration-current density-temperature" to predict nucleation kinetics.

Applications to Plasma Systems: While this specific protocol employs electrochemical deposition, the fundamental approach to quantifying nucleation induction periods and parameter effects provides a methodological framework adaptable to plasma environments through analogous in situ optical and mass spectrometry techniques.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Experimental Parameters and Results for Material Synthesis in Microwave Plasma Reactors

| Material System | Reactor Type | Power (W) | Pressure | Precursor | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diamond Film | TM01/TM02 MPCVD | Not specified | Not specified | H₂/CH₄ | Achieved >94% microwave energy efficiency without external tuning | [4] |

| Graphene | Atmospheric Pressure Microwave Plasma | Varied | Atmospheric | CH₄ | Particle diameter increased with distance from plasma core | [6] |

| Sulfur-doped FLG | Microwave Plasma Aerosol | 1500-2000 W | Not specified | Ethanol/DES | Highest conductivity (67.8 S/m) with 1.3 at% sulfur doping | [22] |

| Acetylene from Methane | Microwave Plasma | 700 W | 50-125 mbar | CH₄/H₂ (40-60%) | Peak temperature: 2100-3000 K; Conversion efficiency: 25-50% | [21] |

| Hydrogen from CO₂/CH₄ | Waveguide Microwave Plasma | ~few kW | Atmospheric | CO₂/CH₄ | H₂ concentration: 33%; CH₄ conversion: 46% | [20] |

Table 2: Characterization Techniques for Nucleation and Growth Analysis

| Technique | Information Obtained | Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | ||

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Morphology, layer number, crystal structure | Identification of crumpled multilayer graphene flakes | [22] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Defect density, crystallinity, layer number | Tracking defect evolution (D/G band ratio) in carbon materials | [22] [6] |

| Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) | Specific surface area, particle size | Surface area analysis of plasma-grown carbon | [6] |

| In situ pH monitoring | Nucleation induction time, reaction kinetics | Real-time OH⁻ concentration monitoring during electrochemical deposition | [23] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Chemical composition, doping elements, bonding states | Confirming sulfur incorporation (~1.3 at%) in doped graphene | [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microwave Plasma Reactor Experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Key Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaseous Precursors | Methane (CH₄), Hydrogen (H₂), Carbon Dioxide (CO₂), Argon (Ar) | Carbon source, reducing atmosphere, plasma generation, carrier gas | High purity (>99.95%); Controlled mixing ratios | [4] [21] [20] |

| Dopant Sources | Diethyl Sulfide (DES), Nitrogen (N₂), Carbon Disulfide (CS₂) | Introducing heteroatoms (e.g., S, N) to modify material properties | Impacts on secondary phase formation; Decomposition kinetics | [22] |

| Reactor Components | Quartz Windows/Tubes, T-shaped Substrates, Coaxial Waveguides | Plasma confinement, substrate mounting, microwave coupling | Thermal stability; Dielectric properties; Geometry optimization | [4] [6] |

| Characterization Standards | Silicon Wafers, Highly Ordered Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) | Calibration standards for spectroscopy and microscopy | Reference materials for instrument calibration | [22] |

| Analytical Tools | Thioflavin-T (ThT), pH indicators, Raman calibration standards | Monitoring aggregation, pH changes, spectrometer calibration | Specificity; Sensitivity; Stability | [23] [24] |

Computational and Process Intensification Strategies

Advanced Modeling Approaches

Computational methods have become indispensable for elucidating the complex multiscale phenomena in nucleation and growth processes:

- Multiphysics Modeling: Advanced simulations self-consistently couple electromagnetic wave propagation, plasma dynamics, heat transfer, and species transport. These models enable prediction of key process outcomes, such as stable plasma discharge with central electron densities of ~5×10¹⁷ m⁻³ in optimized MPECVD systems [9].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: These simulations provide atomistic-level insights into nucleation energetics, kinetics, and mechanisms, allowing researchers to understand molecular interactions during the early stages of phase separation [19].

- Kinetic Analysis Tools: Computational platforms like NAGPKin enable automated quantification of nucleation and growth parameters from experimental progress curves, providing mechanistic insights into phase separation processes [24].

Process Intensification Technologies

Innovative reactor designs and operation strategies enhance nucleation control and process efficiency:

- Microreactor Systems: These systems enable enhanced mixing, heat transfer, and process control, significantly reducing mixing times compared to conventional methods and allowing precise manipulation of the nucleation-growth process [19].

- Membrane Crystallization (MCr): This hybrid technology leverages membranes as heterogeneous nucleation interfaces, providing energy-efficient supersaturation control and enabling production of solid particles with minimal energy requirements [19].

- Mode-Superposition in MPCVD: Deliberate excitation of multiple electromagnetic modes (e.g., TM01 + TM02) enhances microwave field uniformity across substrates, enabling larger, more uniform plasma spheres necessary for large-area diamond deposition [4].

Visualization of Framework and Workflows

The Nucleation-in-the-Bulk, Growth-at-the-Boundary Conceptual Framework

Spatial separation of nucleation and growth stages in a microwave plasma reactor.

Integrated Experimental Workflow for Framework Validation

Integrated experimental approach for validating the nucleation-growth framework.

Advanced Methods for Controlling Nucleation in MPCVD and Gas-Phase Synthesis

The precise control of microwave plasma reactors is paramount for advancing materials synthesis, particularly in the optimization of nucleation processes for nanomaterials. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for the systematic management of three critical reactor parameters—microwave power, system pressure, and gas flow rates—within the context of a broader thesis on nucleation optimization. Microwave plasmas enable highly non-equilibrium chemistry by transferring electrical energy directly into vibrational modes of molecules, facilitating efficient dissociation and nucleation at relatively low translational temperatures [2]. This non-thermal characteristic is especially beneficial for nucleation control, as it promotes precursor dissociation while minimizing uncontrolled particle growth through thermal agglomeration. The protocols outlined herein are designed to provide researchers with standardized methodologies for achieving reproducible and scalable nanomaterial synthesis, with particular emphasis on carbon-based materials and semiconductor nanoparticles [25] [26].

Parameter Interrelationships and Nucleation Effects

The optimization of microwave plasma processes requires a fundamental understanding of how power, pressure, and flow rate parameters interrelate to influence nucleation kinetics and growth dynamics. These factors collectively determine the plasma properties, precursor decomposition rates, and particle residence times, which ultimately govern the nucleation process.

Table 1: Interrelationship of Key Reactor Parameters and Their Collective Impact on Nucleation

| Parameter Combination | Plasma Characteristic | Nucleation Impact | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Power + Low Pressure | High electron temperature, localized heating | Rapid precursor decomposition, focused nucleation zone | High-purity crystal synthesis [26] |

| Moderate Power + Atmospheric Pressure | Broader plasma volume, moderate energy | Distributed nucleation, higher particle yield | Volumetric synthesis of carbon nanomaterials [6] |

| High Flow Rate + Low Pressure | Short residence time, rapid quenching | Limited particle growth, small primary particle size | Iron nanoparticle synthesis [27] |

| Low Flow Rate + High Power | Extended residence at high temperature | Enhanced crystallinity, possible aggregation | Graphene structures with reduced defects [6] |

The interplay between these parameters creates specific conditions that favor particular nucleation pathways. For instance, high microwave power combined with low system pressure typically generates plasmas with elevated electron temperatures, promoting efficient vibrational excitation and precursor dissociation—a crucial first step in nucleation [2]. This combination is particularly effective for synthesizing high-purity crystalline materials where controlled monomer generation is essential. Conversely, moderate power at atmospheric pressure produces a broader plasma volume with more distributed energy, leading to more uniform nucleation throughout the reaction zone, which is beneficial for high-throughput synthesis of carbon-based materials [6].

Gas flow rate primarily affects the residence time of precursors and nucleated particles within the plasma zone, thereby influencing growth kinetics and ultimate particle characteristics. Higher flow rates generally reduce residence times, limiting particle growth and resulting in smaller primary particle sizes, as observed in iron nanoparticle synthesis where increased precursor flow yielded higher nanoparticle counts but smaller sizes [27]. Lower flow rates combined with sufficient power allow for extended exposure to the high-temperature environment, facilitating the development of more crystalline structures with reduced defects, a key consideration in graphene synthesis [6].

Quantitative Parameter Effects

Systematic investigation of individual parameter effects provides a foundation for predictive process control. The following tables summarize documented relationships between specific parameter adjustments and their measurable effects on nucleation and growth outcomes.

Microwave Power Effects

Table 2: Documented Effects of Microwave Power Variation on Process Outcomes

| Power Range | Reported Effect | Material System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step increases of 250 W | Flame jet length increased by nearly 20% per step | ADN-based liquid propellant | [28] |

| Higher power (specific range not stated) | Formation of more crystalline, lower-defect graphene structures | Carbon nanomaterials | [6] |

| Up to 1 kW | Central reactor temperatures up to ~4,000 K; exceeding thermodynamic equilibrium conversion | CO₂ to CO conversion | [2] |

Microwave power directly influences energy transfer to the plasma, affecting both gas temperature and the non-equilibrium characteristics of the discharge. Higher power levels typically increase both electron density and gas temperature, leading to more complete precursor decomposition and higher nucleation rates [2]. This relationship is particularly evident in carbon nanomaterial synthesis, where higher plasma power favors the formation of more crystalline, lower-defect graphene structures [6]. The thermal effects of power increases are clearly demonstrated in propulsion applications, where 250 W step increases resulted in nearly 20% growth in flame jet length per increment [28]. However, the relationship between power and temperature is often non-linear, with temperature increases gradually slowing at higher power levels due to enhanced radiative and convective losses [28].

Pressure Effects

Table 3: Documented Effects of System Pressure Variation on Process Outcomes

| Pressure Range | Reported Effect | Material System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mbar to atmospheric | Flexible operation range for ignition and process optimization | General plasma processes | [2] |

| 10 kPa absolute | Standard condition for silicon nanoparticle synthesis | Silicon from monosilane | [26] |

| ~50 Pa | Optimal plasma power coupling and efficient nanoparticle production | Hydrocarbon-based nanoparticles | [29] |

| Lower pressures | Favor non-equilibrium conditions with higher vibrational temperatures | CO₂ dissociation | [2] |

System pressure profoundly affects plasma characteristics by influencing electron energy distribution, mean free path, and reaction kinetics. Lower pressures typically favor non-equilibrium conditions where vibrational temperatures significantly exceed translational temperatures, creating ideal environments for efficient dissociation of stable molecules like CO₂ through vibrational excitation [2]. This condition is highly beneficial for nucleation control as it promotes precursor fragmentation while maintaining moderate gas temperatures that prevent uncontrolled particle sintering. Specific pressure ranges have been optimized for particular applications, with approximately 50 Pa providing optimal plasma coupling and efficient nanoparticle production in hydrocarbon systems [29], while 10 kPa (100 mbar) has been established as a standard condition for silicon nanoparticle synthesis [26]. The ability to operate across a wide pressure range from 5 mbar to atmospheric pressure provides flexibility for process optimization and scale-up [2].

Gas Flow Rate Effects

Table 4: Documented Effects of Gas Flow Rate Variation on Process Outcomes

| Flow Rate | Reported Effect | Material System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 L/min | Best combustion performance with maximum jet length (14.51 cm) | ADN-based liquid propellant | [28] |

| 14 L/min to 20 L/min | Average jet length increase of ~85.9% | ADN-based liquid propellant | [28] |

| Increased precursor flow | Higher nanoparticle count but smaller size and lower temperature | Iron nanoparticles | [27] |

| Increased methane flow | Higher defect densities and larger particle sizes | Carbon nanomaterials | [6] |

| 0.5-10 SLM range | Typical operational range for laboratory-scale reactors | CO₂ conversion systems | [2] |

Gas flow rate parameters determine residence times and directly impact nucleation kinetics and particle growth. Optimal flow rates balance sufficient residence time for complete precursor conversion with practical considerations for particle quenching and collection. In propulsion applications, ADN-based liquid propellants demonstrated optimal combustion performance at 20 L/min, with an 85.9% increase in jet length compared to 14 L/min [28]. Excessively high flow rates can hinder process development through cooling effects and reduced residence times, as demonstrated in iron nanoparticle synthesis where increased precursor flow yielded higher particle counts but resulted in smaller nanoparticle size and lower temperature [27]. In carbon nanomaterial synthesis, increased methane flow generally led to higher defect densities and larger particle sizes [6], highlighting the complex relationship between precursor availability and material quality. Typical laboratory-scale reactors operate within the 0.5-10 standard liters per minute (SLM) range [2], providing flexibility for process optimization across different material systems.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Microwave Plasma Reactor Configuration and Ignition

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for configuring a microwave plasma reactor and achieving stable plasma ignition, adapted from established methodologies [2].

Materials and Equipment:

- 1 kW microwave magnetron with circulator and water load

- Three-stub tuner for impedance matching

- Waveguide applicator with sliding short

- Quartz tube (17 mm or 27 mm inner diameter)

- Vacuum system with KF-flanges (KF-16 for 17-mm tube, KF-40 for 27-mm tube)

- Tangential gas inlet assembly

- Throttle valve and vacuum pump

- Mass flow controller (range: 0.5-10.0 SLM)

- Water cooling system

- Safety systems (radiation meter, gas detector for CO, H₂, NOₓ)

Procedure:

- Assembly: Connect the magnetron to the circulator with attached water load. Link the isolator to the three-stub tuner, then attach the applicator to the tuner. Add a sliding short to the waveguide end.

- Reactor Installation: Place the quartz tube through the applicator hole. Connect the tube to the KF-flanges and gas inlet, ensuring proper sizing (KF-16 for 17-mm tube, KF-40 for 27-mm tube).

- Gas System: Install the tangential gas inlet to induce vortex flow, protecting the tube walls from thermal damage. Connect the mass flow controller to regulate gas input.

- Vacuum System: Connect the throttle valve in series with the vacuum pump to regulate pressure (5 mbar to atmospheric). Install a parallel shortcut valve to switch between low-pressure ignition and high-pressure operation without losing throttle valve settings.

- Safety Check: Confirm that cooling water is flowing to the magnetron. Verify that all safety systems are operational, including radiation monitoring and gas detection.

- Ignition: Turn on power and gradually increase to maximum level. Adjust the plunger and three-stub tuners while monitoring reflected power, aiming to minimize reflections. If available, use a network analyzer for precise impedance matching [2].

- Stabilization: Once plasma is ignited, adjust parameters to desired operating conditions for specific applications.

Protocol: Silicon Nanoparticle Synthesis via Microwave Plasma

This protocol details the specific parameters for synthesizing silicon nanoparticles from monosilane precursor, based on published experimental work [26].

Materials and Equipment:

- Microwave plasma reactor (as configured in Protocol 4.1)

- Precursor gas mixture: H₂ (0.2 SLM), Ar (2 SLM), SiH₄ (0.03 SLM)

- Pressure regulation system capable of maintaining 10 kPa absolute pressure

- Central injection nozzle (4 mm diameter)

- Particle collection system

Procedure:

- Reactor Preparation: Ensure the reactor is clean and properly configured according to Protocol 4.1.

- Parameter Setting: Set the system pressure to 10 kPa absolute. Configure gas flows to H₂ (0.2 SLM), Ar (2 SLM), and SiH₄ (0.03 SLM).

- Precursor Injection: Inject the precursor gas mixture through the central nozzle (4 mm diameter) into the plasma zone.

- Swirl Gas Configuration: Employ tangential gas injection to create swirl flow, confining the precursor stream and minimizing particle deposition on quartz inliner.

- Plasma Ignition: Ignite plasma using standard ignition procedure (Protocol 4.1, steps 5-7).

- Process Monitoring: Monitor process stability through plasma emission characteristics. The synthesis process typically generates a thin (1-2 mm) particle stream at the circumference of the plasma.

- Collection: Collect synthesized nanoparticles downstream using appropriate collection methods (filtration, thermophoretic deposition, etc.).

Protocol: In-situ Diagnostics for Nucleation Monitoring

This protocol describes the implementation of laser diagnostics for real-time monitoring of nucleation processes, combining methodologies from multiple sources [2] [27] [29].

Materials and Equipment:

- Nd:YAG laser (532 nm, 10 Hz repetition rate, max 600 mJ per pulse)

- Anti-reflection coated windows or Brewster windows

- Rayleigh scattering detection system

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) system

- Optical emission spectroscopy system

- Laser-induced incandescence system (for iron nanoparticles) [27]

Procedure:

- Laser Alignment: Align the Nd:YAG laser beam axially through the reactor using steering mirrors. Mount AR-coated windows on opposite sides of the reactor at entrance and exit ports.

- Rayleigh Scattering Setup: For temperature measurements, focus the laser to create a sample volume. Detect elastic scattering of photons on bound electrons of gas molecules.

- Temperature Calculation: Relate gas temperature to Rayleigh signal intensity using the formula: T = p/(I × (dσ/dΩ(T)) × C), where p is pressure, I is Rayleigh intensity, dσ/dΩ(T) is the temperature-dependent Rayleigh cross section, and C is a calibration constant [2].

- Composition Monitoring: Implement FTIR spectroscopy to characterize in-situ vibrational excitation and effluent composition, enabling conversion and selectivity calculations.

- Iron Nanoparticle Diagnostics: For iron nanoparticle synthesis, employ complementary diagnostics including line-of-sight attenuation and two-color thermometry [27].

- Hydrocarbon Chemistry Monitoring: For hydrocarbon precursors, utilize Quantum Cascade Laser Absorption Spectroscopy (QCLAS) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) to track precursor decomposition and intermediate species formation [29].

- Data Correlation: Correlate diagnostic readings with process parameters to establish relationships between plasma conditions and nucleation characteristics.

Visualization of Process Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between reactor parameters and their effects on nucleation processes, synthesizing information from multiple referenced studies.

The diagram illustrates how the three primary reactor parameters (power, pressure, and flow rate) influence physical mechanisms within the plasma, which subsequently determine nucleation outcomes. Microwave power primarily affects vibrational excitation and electron density, which collectively enhance precursor decomposition—the critical first step in nucleation [2]. Pressure modifications alter the plasma regime, with lower pressures favoring non-equilibrium conditions that enhance vibrational excitation. Flow rate directly controls residence time and quenching rates, which are primary determinants of particle size and crystallinity [6]. These interrelationships highlight the importance of coordinated parameter adjustment rather than individual parameter optimization for controlling nucleation processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Materials for Microwave Plasma Nucleation Studies

| Material/Reagent | Specification/Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | High-purity (>99.9%), primary carbon source | Conversion to CO and carbon nanotubes [2] [30] |

| Monosilane (SiH₄) | 0.03 SLM in hydrogen/argon mixture | Silicon nanoparticle precursor [26] |

| Acetylene (C₂H₂) | Hydrocarbon precursor, 0.5-10 SLM range | Carbon nanoparticle synthesis [29] |

| Methane (CH₄) | Carbon source with hydrogen content | Graphene-like carbon synthesis [6] |

| Argon (Ar) | Carrier gas, plasma initiation | Silicon nanoparticle synthesis (2 SLM) [26] |

| Hydrogen (H₂) | Reducing agent, carrier gas | Silicon nanoparticle synthesis (0.2 SLM) [26] |

| Lithium Carbonate | Battery grade (>99.5%), molten electrolyte | CO₂ to CNT conversion [30] |

| Quartz Tubes | 17 mm or 27 mm inner diameter, plasma containment | Reactor chamber [2] |

| Muntz Brass | 60% Cu, 40% Zn; electrolysis cathode | CO₂ to CNT conversion [30] |

| Stainless Steel 304 | Reactor construction, anode material | CO₂ electrolysis cell [30] |