Optimizing Acquisition Functions for Bayesian Optimization: A Guide for Drug Discovery and Scientific Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on optimizing acquisition functions (AFs) for Bayesian optimization (BO), with a focus on drug discovery applications.

Optimizing Acquisition Functions for Bayesian Optimization: A Guide for Drug Discovery and Scientific Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on optimizing acquisition functions (AFs) for Bayesian optimization (BO), with a focus on drug discovery applications. It covers foundational principles, exploring the critical role of AFs in balancing exploration and exploitation for expensive black-box functions. The piece delves into advanced methodological adaptations for complex scenarios like batch, multi-objective, and high-dimensional optimization. It further addresses common pitfalls and troubleshooting strategies, including the impact of noise and hyperparameter tuning. Finally, it presents a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of different AFs, empowering professionals to select and design efficient optimization strategies for their specific experimental goals.

The Core of Sample Efficiency: Understanding Acquisition Functions in Bayesian Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an acquisition function in Bayesian optimization? An acquisition function is a mathematical heuristic that guides the search in Bayesian optimization by quantifying the potential utility of evaluating a candidate point. It uses the surrogate model's predictions (mean and uncertainty) to balance exploring new regions and exploiting known promising areas, determining the next best point to evaluate in an expensive experiment [1] [2] [3].

My BO algorithm is too exploitative and gets stuck in local optima. What can I do? This is a common problem often linked to the configuration of the acquisition function. You can try the following remedies:

- For UCB: Increase the β parameter to give more weight to the uncertainty term, encouraging exploration [1].

- For EI/PI: Introduce or increase an

ϵorτtrade-off parameter. This effectively lowers the bar for what is considered an improvement, making the algorithm more willing to explore areas that are slightly worse than the current best but have high uncertainty [4] [2]. - Switch Acquisition Functions: If using Probability of Improvement (PI), consider switching to Expected Improvement (EI), as EI accounts for both the probability and magnitude of improvement, which can lead to better exploration characteristics [1] [5] [2].

Why is my Bayesian optimization performing poorly with very few initial data points? The quality of the surrogate model is crucial, especially in the few-shot setting. Standard space-filling initial designs may not effectively reduce predictive uncertainty or facilitate efficient learning of the surrogate model's hyperparameters. Consider advanced initialization strategies like Hyperparameter-Informed Predictive Exploration (HIPE), which uses an information-theoretic acquisition function to balance uncertainty reduction with hyperparameter learning during the initial phases [6].

How do I choose the right acquisition function for my problem? The choice depends on your specific optimization goal. The table below compares the most common acquisition functions.

| Acquisition Function | Mathematical Formulation | Best Use Case | Trade-off Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [1] [5] | ( \alpha(x) = \mu(x) + \lambda \sigma(x) ) | Problems where a direct balance between mean performance and uncertainty is desired. | Parameter ( \lambda ) explicitly controls exploration vs. exploitation. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) [1] [4] [3] | ( \text{EI}(x) = \delta(x)\Phi\left(\frac{\delta(x)}{\sigma(x)}\right) + \sigma(x) \phi\left(\frac{\delta(x)}{\sigma(x)}\right) ) | General-purpose optimization; considers both how likely and how large an improvement will be. | Parameter ( \tau ) (trade-off) can be added to ( \delta(x) = \mu(x) - m_{opt} - \tau ) to encourage more exploration [4]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) [1] [5] [2] | ( \text{PI}(x) = \Phi\left(\frac{\mu(x) - f(x^+)}{\sigma(x)}\right) ) | When the primary goal is to find any improvement over the current best value. | Parameter ( \epsilon ) can be added to the denominator to control exploration [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Over-Smoothing and Incorrect Prior Width

Issue: The surrogate model (Gaussian Process) fails to capture the true complexity of the black-box function, leading to poor optimization performance. This can manifest as the optimizer missing narrow but important peaks in the response surface, which is critical in molecule design [5].

Diagnosis:

- Check Model Fit: Visually inspect the surrogate model's mean and confidence intervals against your observed data. If the model appears too smooth and misses regions where the data changes rapidly, over-smoothing is likely.

- Review Kernel Hyperparameters: The lengthscale (( \ell )) in the kernel (e.g., RBF kernel ( k_{\text{RBF}}(x, x') = \sigma^2 \exp\left(-\frac{\|x - x'\|^2}{2\ell^2}\right) )) controls smoothness. A lengthscale that is too large will over-smooth the data [5].

Solution:

- Use Informative Priors: Instead of relying on default or weak priors for hyperparameters like the kernel lengthscale and amplitude, use priors that reflect your domain knowledge about the function's expected variability [5].

- Model Selection: Consider using a more flexible kernel that can capture different levels of smoothness, rather than the standard RBF kernel.

Problem: Inadequate Maximization of the Acquisition Function

Issue: Even with a well-specified surrogate and acquisition function, finding the global maximum of the acquisition function itself can be challenging. Failure to do so means you may not select the truly best point to evaluate next [5].

Diagnosis: If the optimization process is making slow or no progress despite the surrogate model showing promising regions, the issue may lie in the inner-loop optimization of the acquisition function.

Solution:

- Use Multiple Restarts: When optimizing the acquisition function, use a multi-start optimization strategy. This involves running the local optimizer from many different starting points to reduce the chance of settling for a poor local maximum [5].

- Leverage Analytical Properties: For analytic acquisition functions (like EI and UCB), you can use gradient-based optimizers (e.g., L-BFGS) for faster and more reliable convergence, as the gradients can be computed [7].

- For Monte Carlo Acquisition Functions: When using quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) methods for batch acquisition functions, consider using a fixed set of base samples. This makes the acquisition function deterministic and easier to optimize with standard methods [7].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Bayesian Optimization Loop

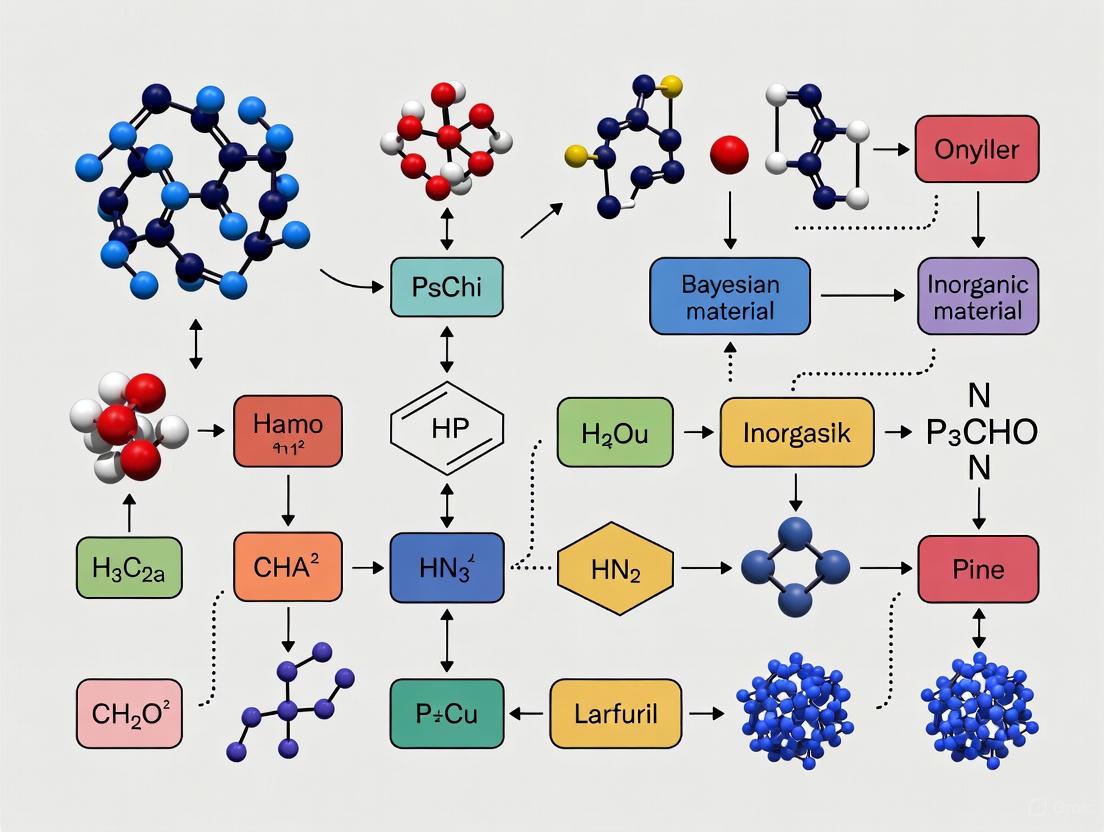

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of a standard Bayesian Optimization process, highlighting the central role of the acquisition function.

Protocol Details:

- Initialization: Begin with a small set of initial evaluations, often selected via a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) or an informed strategy like HIPE [6].

- Surrogate Model Fitting: Fit a Gaussian Process (GP) to all observed data ( \mathcal{D}{1:t} ). The GP provides a posterior distribution ( p(f(x)|\mathcal{D}{1:t}) ) characterized by a mean function ( \mu(x) ) and an uncertainty function ( \sigma(x) ) [1] [3].

- Acquisition Function Optimization: Using the GP posterior, compute the acquisition function ( \alpha(x) ) over the search space. Find the point ( x{t+1} ) that maximizes this function: ( x{t+1} = \arg\max_x \alpha(x) ). This step is critical and may require a robust internal optimizer [5] [7].

- Expensive Evaluation: Evaluate the black-box function (e.g., run a drug assay) at the new point ( x{t+1} ) to obtain ( y{t+1} ).

- Update & Iterate: Augment the dataset with ( (x{t+1}, y{t+1}) ) and repeat from step 2 until a stopping condition is met (e.g., evaluation budget exhausted, performance plateau) [2] [3].

Multifidelity Bayesian Optimization for Drug Discovery

In drug discovery, experiments exist at different fidelities (e.g., computational docking, medium-throughput assays, low-throughput IC50 measurements). Multifidelity Bayesian Optimization (MF-BO) leverages cheaper, lower-fidelity data to guide expensive, high-fidelity experiments [8].

Key Methodology:

- Surrogate Model: A GP is extended to model the objective function across multiple fidelities.

- Acquisition Function: The acquisition function (e.g., EI) is modified to account for the cost and information gain of evaluating at different fidelities. It automatically decides not only where to sample but also at what fidelity to sample.

- Utility: This approach has been shown to successfully discover new histone deacetylase inhibitors with sub-micromolar inhibition by sequentially choosing between docking scores, single-point percent inhibitions, and dose-response IC50 values [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key computational "reagents" essential for implementing Bayesian Optimization in experimental research.

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A probabilistic model used as a surrogate to approximate the unknown objective function, providing mean and uncertainty estimates at any point. | The workhorse of BO. Choice of kernel (e.g., RBF, Matern) dictates the smoothness of the function approximation [5] [3]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | An acquisition function that selects the next point based on the expected value of improving upon the current best observation. | A robust, general-purpose choice. Its closed-form formula for GPs allows for efficient computation [1] [4] [3]. |

| UCB / PI | Alternative acquisition functions; UCB uses a confidence bound, while PI uses the probability of improvement. | UCB's (\lambda) parameter offers explicit control. PI can be more exploitative and may require an (\epsilon) parameter for better performance [1] [2]. |

| Multi-Start Optimizer | An algorithm used to find the global maximum of the acquisition function by starting from many initial points. | Critical for reliably solving the inner optimization loop. Often used with L-BFGS or other gradient-based methods [5] [7]. |

| Hierarchical Model | A surrogate model structure where parameters are grouped (e.g., by experimental batch or molecular scaffold) to share statistical strength. | Useful for managing structured noise or leveraging known groupings in the search space, common in drug discovery. |

Your FAQs on Acquisition Functions

What is the fundamental purpose of an acquisition function?

The acquisition function is the core decision-making engine in Bayesian Optimization (BO). Its primary role is to guide the search for the optimum of a costly black-box function by strategically balancing exploration (sampling in regions of high uncertainty) and exploitation (sampling in regions with a promising predicted mean) [3] [9]. You cannot simply optimize the Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model directly because the GP is an imperfect approximation, especially with limited data. Optimizing it directly would lead to pure exploitation and a high risk of getting stuck in a local optimum. The acquisition function provides a principled heuristic to navigate this trade-off [9].

My optimization seems stuck in a local minimum. How can I encourage more exploration?

This is a common challenge. You can mitigate it by:

- Switching your acquisition function: If you are using Probability of Improvement (PI), try Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) instead. PI is known to be more exploitative [3] [10].

- Tuning the exploration parameter: If using UCB, increase the

βparameter. A higherβvalue places more weight on the uncertainty term, making the search more exploratory [10] [9]. - Using "plus" variants: Some software frameworks, like MATLAB's

bayesopt, offer "plus" variants of acquisition functions (e.g.,'expected-improvement-plus'). These algorithms automatically detect overexploitation and modify the kernel to increase variance in unexplored regions, helping to escape local optima [10].

How do I choose the best acquisition function for my specific problem?

The choice depends on your problem's characteristics and your primary goal. The following table provides a high-level guideline based on synthesis of the search results.

| Acquisition Function | Best For | Key Characteristics | Potential Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | A robust, general-purpose choice for balanced performance [11] [10]. | Well-balanced exploration/exploitation; has an analytic form; widely used and studied [3] [7]. | Performance can be sensitive to the choice of the incumbent (the best current value) in noisy settings [12] [13]. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Problems where you want explicit control over the exploration-exploitation balance [10]. | Has a clear parameter β to tune exploration; theoretically grounded with regret bounds [3] [9]. |

Requires tuning of the β parameter, which can be non-trivial [11]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | Quickly converging to a local optimum when a good starting point is known. | A simple, intuitive metric [10]. | Highly exploitative; can easily get stuck in local optima and miss the global solution [3] [14]. |

My objective function evaluations are noisy. What should I be careful about?

Noise introduces additional challenges. A key recommendation is to carefully select the incumbent (the value considered the "current best" used in EI and PI). The naive choice of using the best observed value (BOI) can be "brittle" with noise. Instead, prefer the Best Posterior Mean Incumbent (BPMI) or the Best Sampled Posterior Mean Incumbent (BSPMI), as they have been proven to provide no-regret guarantees even with noisy observations [12] [13]. Furthermore, ensure your GP model includes a noise term (e.g., a White Noise kernel) to account for the heteroscedasticity often present in experimental data [14] [15].

A Researcher's Guide to Key Formulations

The table below summarizes the mathematical definitions and key considerations for implementing the three classic acquisition functions.

| Function | Mathematical Formulation | Experimental Protocol & Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | EI(x) = E[max(μ(x_best) - f(x), 0)] Analytic form: EI(x) = σ(x) [z Φ(z) + φ(z)], where z = (μ(x) - f(x_best)) / σ(x) [3] [7]. |

Protocol: The most robust choice for general use. For batch optimization, use the Monte Carlo version (qEI) [11] [7]. Note: The choice of x_best is critical. For noisy settings, use BPMI or BSPMI instead of the best observation (BOI) [12] [13]. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | UCB(x) = μ(x) + β * σ(x) [3] [10]. |

Protocol: Ideal when a specific exploration strategy is desired. The parameter β controls exploration; a common practice is to use a schedule that decreases β over time. Note: In serial and batch comparisons, UCB has been shown to perform well in noisy, high-dimensional problems [11]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | PI(x) = P( f(x) ≤ μ(x_best) - m ) Computed as PI = Φ(ν_Q(x)), where ν_Q(x) = [μ_Q(x_best) - m - μ_Q(x)] / σ_Q(x) [10]. |

Protocol: Use when you need to quickly refine a known good solution. The margin m (often set as the noise level) helps moderate greediness [10]. Note: This function is notoriously exploitative and is not recommended for global optimization of complex, multi-modal surfaces [3] [14]. |

Workflow and Trade-offs in Practice

The following diagram illustrates the standard Bayesian optimization workflow and the role of the acquisition function.

The logical trade-off between exploration and exploitation, managed by the acquisition function, can be visualized as a spectrum.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

When setting up a Bayesian Optimization experiment, consider the following essential "research reagents" – the core components and tools you need to have prepared.

| Tool / Component | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate | Serves as a probabilistic model of the expensive black-box function, providing predictions and uncertainty estimates for unexplored parameters [3] [14]. |

| ARD Matérn 5/2 Kernel | A common and robust default kernel for the GP. It controls the covariance between data points and makes realistic smoothness assumptions about the objective function [10]. |

| Optimization Library (e.g., BoTorch) | Provides implemented, tested, and optimized acquisition functions and GP models, which is crucial for correctly executing the optimization loop [3] [7]. |

| Incumbent Selection Strategy | The method for choosing the "current best" value. In noisy experiments, BSPMI (Best Sampled Posterior Mean Incumbent) offers a robust and computationally efficient choice [12] [13]. |

| Boundary Avoidance Technique | A mitigation strategy for preventing the algorithm from over-sampling at the edges of the parameter space, which is a common failure mode in high-noise scenarios like neuromodulation [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core benefit of using Batch Bayesian Optimization over sequential BO? Batch BO allows for the concurrent selection and evaluation of multiple points (a batch), enabling parallel use of experimental resources. This dramatically reduces the total wall-clock time required to optimize expensive black-box functions, a critical advantage in settings with access to parallel experiment or compute resources [16].

Q2: In a high-noise scenario, my batch optimization seems to stall. What acquisition functions are more robust?

Monte Carlo-based batch acquisition functions, such as q-log Expected Improvement (qlogEI) and q-Upper Confidence Bound (qUCB), have been shown to achieve faster convergence and are less sensitive to initial conditions in noisy environments compared to some serial methods [11]. For larger batches, the Parallel Knowledge Gradient (q-KG) also demonstrates superior performance, especially under observation noise [16].

Q3: My batch selections are often too similar, leading to redundant evaluations. How can I promote diversity? This is a common challenge. You can employ strategies that explicitly build diversity into the batch:

- Local Penalization (LP): This method penalizes the acquisition function near already-selected points in the batch, creating "exclusion zones" to avoid clustering [16].

- Acquisition Thompson Sampling (ATS): By sampling independent instantiations of the acquisition function over different GP hyperparameters, ATS naturally constructs a diverse batch with minimal computational overhead [16].

- Determinantal Point Processes (DPPs): These combinatorial tools encourage spatial diversity in the batch by making the probability of selecting a set of points proportional to the determinant of their kernel matrix [16].

Q4: For a "black-box" function with no prior knowledge, what is a good default batch acquisition function?

Recent research on noiseless functions in up to six dimensions suggests that qUCB and the serial Upper Confidence Bound with Local Penalization (UCB/LP) perform well. When no prior knowledge of the landscape or noise characteristics is available, qUCB is recommended as a default to maximize confidence in finding the optimum while minimizing expensive samples [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Optimization Performance and Slow Convergence

Problem: The BO process is not efficiently finding better solutions, or convergence is slower than expected.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Incorrect Prior Width in the Surrogate Model:

- Cause: An improperly specified prior (e.g., the amplitude/lengthscale in a Gaussian Process) can lead the model to be over- or under-confident in its predictions, misguiding the acquisition function [17].

- Solution: Carefully choose and, if possible, marginalize over the GP hyperparameters. Using Acquisition Thompson Sampling (ATS), which samples hyperparameters from their posterior, can automatically address this issue [16].

Over-Smoothing from the Kernel Function:

- Cause: An inappropriate kernel (e.g., an RBF kernel with too large a lengthscale) might oversmooth the objective function, missing important local features [17].

- Solution: Consider using more flexible kernels like the Matérn kernel, which can better capture variations in the function's smoothness. For biological data, a modular kernel architecture that allows users to select or combine covariance functions is beneficial [14].

Inadequate Maximization of the Acquisition Function:

- Cause: The acquisition function is often non-convex and multi-modal. Inadequate optimization can result in selecting suboptimal points for the next batch [17].

- Solution: Ensure a thorough optimization strategy for the acquisition function, such as multi-start optimization (MSO). New methods propose decoupling optimizer updates while batching acquisition function calls to achieve faster wall-clock time and identical convergence to sequential MSO [18].

Issue 2: Performance Degradation with Increasing Batch Size

Problem: As you increase the batch size, the quality of each selected point decreases, and the optimization becomes less sample-efficient.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Information Staleness:

- Cause: Later points in a batch are chosen without knowledge of the outcomes of earlier points in the same batch, as all evaluations are concurrent. This can make the batch selections stale compared to a sequential policy [16].

- Solution: Use methods that simulate the outcome of pending experiments. Kriging-Believer and Constant-Liar approaches sequentially "hallucinate" outcomes for batch points (e.g., using the predicted mean) and refit the GP before selecting the next point in the batch, thereby inducing diversity and mitigating staleness [16].

Lack of a Dedicated Diversity Mechanism:

- Cause: Greedily selecting the top points from a sequential acquisition function without modification will lead to all points clustering around the most promising area, providing redundant information [16].

- Solution: Actively integrate diversity-promoting techniques. The table below compares several methods suitable for different batch sizes and computational budgets.

| Method | Mechanism | Ideal Batch Size | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Penalization (LP) [16] | Adds a penalizer to the acquisition function around pending points. | Low to Moderate | Fast wall-clock speed; requires only one GP retraining per batch. |

| Acquisition Thompson Sampling (ATS) [16] | Samples parallel acquisitions from different GP hyperparameter instantiations. | Large (e.g., 20+) | Trivially parallelizable; minimal modification to sequential acquisitions. |

| Determinantal Point Processes (DPPs) [16] | Selects batches with probability proportional to the determinant of the kernel matrix. | Combinatorial/High-D | Strong theoretical guarantees for diversity. |

| Optimistic Expected Improvement (OEI) [16] | Uses a distributionally-ambiguous set to derive a tractable lower-bound for batch EI. | Large (≥20) | Robust, differentiation-friendly; scales better than classic batch EI. |

Issue 3: Long Computational Overhead for Batch Selection

Problem: The process of selecting a batch of points itself becomes a computational bottleneck.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Complex Joint-Acquisition Criteria:

- Cause: Some batch acquisition functions, like the classic parallel Expected Improvement (EI), require computing high-dimensional integrals, which are computationally intractable for large batches [16].

- Solution: Adopt computationally efficient approximations. Optimistic EI (OEI) reformulates the problem as a tractable semidefinite program (SDP), while ATS avoids joint optimization altogether by leveraging parallel sampling [16].

Inefficient Multi-Start Optimization (MSO):

- Cause: Standard MSO with batched acquisition function calls can lead to suboptimal inverse Hessian approximations in quasi-Newton methods, slowing convergence [18].

- Solution: Implement methods that decouple the optimizer updates while still batching the acquisition function evaluations. This maintains theoretical convergence guarantees while drastically reducing wall-clock time [18].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Performance Comparison of Batch Acquisition Functions

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from a 2025 study comparing batch acquisition functions on standard benchmark functions, providing a guide for initial method selection [11].

| Acquisition Function | Ackley (Noiseless) | Hartmann (Noiseless) | Hartmann (Noisy) | Recommended Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCB/LP (Serial) | Good | Good | Poorer performance & sensitivity | Noiseless, smaller batches |

| qUCB | Good | Good | Faster convergence, less sensitivity | Default for black-box functions in ≤6 dimensions |

| qlogEI | Outperformed | Outperformed | Faster convergence, less sensitivity | Noisy environments |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers applying batch BO in experimental biology, the following tools and concepts are essential [14].

| Item / Concept | Function / Role in Batch BO |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Probabilistic surrogate model that maps inputs to predicted outputs and associated uncertainty. |

| Kernel (Covariance Function) | Defines the smoothness and shape assumptions of the objective function (e.g., RBF, Matérn). |

| Acquisition Function | Guides the selection of next batch points by balancing exploration and exploitation (e.g., EI, UCB, PI). |

| Heteroscedastic Noise Model | Accounts for non-constant measurement uncertainty inherent in biological systems, improving model fidelity. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Batch Bayesian Optimization Core Workflow

Diversity-Promoting Batch Construction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the "curse of dimensionality" and how does it affect Bayesian optimization? The curse of dimensionality refers to phenomena that arise when working with data in high-dimensional spaces. In Bayesian optimization (BO), it manifests as an exponential increase in the volume of the search space, causing data points to become sparse and distance metrics to become less meaningful. This requires exponentially more data to model the objective function with the same precision, complicating the fitting of Gaussian process hyperparameters and the maximization of the acquisition function [19] [20].

2. Why does my Bayesian optimization algorithm fail to converge in high dimensions? Common causes include incorrect prior width in the surrogate model, over-smoothing, and inadequate acquisition function maximization [5]. Vanishing gradients during Gaussian process fitting, often due to poor initialization schemes, can also cause failure. This occurs because the gradient of the GP likelihood becomes extremely small, preventing proper hyperparameter optimization [19].

3. How can I improve acquisition function performance in high-dimensional spaces? Use acquisition functions that explicitly balance exploration and exploitation. Expected Improvement (EI) generally performs better than Probability of Improvement (PI) because it considers both the likelihood and magnitude of improvement [1] [5]. For high-dimensional spaces, methods that promote local search behavior around promising candidates have shown success [19].

4. Does Bayesian optimization work for problems with over 100 dimensions? Yes, with proper techniques. Recent research shows that simple BO methods can scale to high-dimensional real-world tasks when using appropriate length scale estimation and local search strategies. Performance on extremely high-dimensional problems (on the order of 1000 dimensions) appears more dependent on local search behavior than a perfectly fit surrogate model [19].

5. What are the trade-offs between exploration and exploitation in high-dimensional BO? Exploration involves sampling uncertain regions to improve the global model, while exploitation focuses on areas known to have high performance. In high-dimensional spaces, over-exploration can waste evaluations on the vast, sparse space, while over-exploitation may cause stagnation in local optima. Acquisition functions with tunable parameters like Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) help balance this trade-off [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Surrogate Model Performance in High Dimensions

Diagnosis Table

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check |

|---|---|---|

| GP predictions are inaccurate despite many samples | Data sparsity due to high dimensions | Calculate average distance between points; in high dimensions, distances become large and similar [20] |

| Length scales converge to extreme values | Vanishing gradients during GP fitting | Check gradient norms during optimization; very small values indicate this issue [19] |

| Model fails to identify clear patterns | Inadequate prior width | Test different priors; uniform U(10⁻³,30) may perform better than Gamma(3,6) in high dimensions [19] |

Remediation Protocol

Step 1: Adjust Length Scale Initialization

- Use Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) with careful initialization to avoid vanishing gradients

- Implement MSR (MLE Scaled with RAASP), which scales length scales dimensionally [19]

- Code example for length scale initialization:

Step 2: Optimize GP Hyperparameters

- Use a dimensionality-scaled log-normal hyperprior that shifts the mode by a factor of √d [19]

- Consider uniform priors U(10⁻³, 30) which have shown better performance than gamma priors in high dimensions [19]

- Increase the number of restarts for hyperparameter optimization to avoid poor local minima

Step 3: Validate Model Fit

- Perform cross-validation on a holdout set of evaluated points

- Check if the model can predict known function values accurately

- Ensure length scales are appropriately sized for the domain

Problem: Ineffective Acquisition Function Optimization

Diagnosis Table

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check |

|---|---|---|

| BO stagnates at local optima | Over-exploitation | Check if acquisition function values cluster around current best points with low uncertainty |

| BO explores randomly without improvement | Over-exploration | Monitor if successive evaluations rarely improve on current best |

| Poor sample efficiency | Inappropriate acquisition function | Compare performance of EI, UCB, and PI on a subset of data |

Remediation Protocol

Step 1: Select Appropriate Acquisition Function

- Use Expected Improvement (EI) which considers both probability and magnitude of improvement [1] [5]

- For tunable exploration, use Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): α(x) = μ(x) + λσ(x) where λ controls exploration [1]

- Avoid Probability of Improvement (PI) for high-dimensional problems as it doesn't account for improvement magnitude [5]

Step 2: Optimize Acquisition Function Maximization

- Use a hybrid approach for acquisition function optimization: combine quasi-random sampling with local perturbation of best candidates [19]

- Perturb approximately 20 dimensions on average when generating candidates from current best points

- Implement a trust region approach to focus search in promising areas [19]

Step 3: Balance Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off

- For EI: Adjust the ξ parameter to control exploration (higher values promote exploration)

- For UCB: Systematically tune the β parameter: start with β ≈ 0.5 for more exploitation, increase to β ≈ 2-3 for more exploration [1]

- Monitor the balance by tracking whether new evaluations improve current best or reduce uncertainty in unexplored regions

Problem: Exponential Data Requirements

Diagnosis Table

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check |

|---|---|---|

| Performance plateaus after initial improvements | Insufficient samples for model complexity | Track performance vs. number of evaluations; high dimensions require exponentially more points [20] |

| Model variance remains high despite many evaluations | Inherent data sparsity in high dimensions | Calculate the ratio of evaluations to dimensions; in high dimensions, this ratio is typically unfavorable |

Remediation Protocol

Step 1: Implement Dimensionality Reduction

- Use linear embeddings (if low-dimensional subspace exists) or non-linear embeddings

- Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify dominant directions of variation [21]

- For structured problems, use additive models that decompose the function into lower-dimensional components [19]

Step 2: Leverage Problem Structure

- Identify if the objective function has additive structure using specialized kernels

- Check for axis-aligned relevance, where only a subset of dimensions significantly affect the output [19]

- Use automatic relevance determination (ARD) kernels to identify important dimensions

Step 3: Optimize Experimental Design

- Use space-filling initial designs (Latin Hypercube Sampling) to maximize information gain from initial evaluations

- Implement active learning strategies for initial phase to build better global model

- Focus on local search around promising candidates once initial promising regions are identified

Acquisition Function Comparison Table

| Acquisition Function | Mathematical Formulation | Best For | Dimensionality Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | α(x) = P(f(x) ≥ f(x⁺) + ε) [2] | Problems where likelihood of any improvement is prioritized | Poor in high dimensions as it doesn't account for improvement magnitude [5] |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | α(x) = E[max(0, f(x) - f(x⁺))] [1] [5] | General-purpose optimization considering both probability and magnitude of improvement | Good, especially with appropriate tuning [5] |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | α(x) = μ(x) + λσ(x) [1] | Problems where explicit exploration-exploitation control is needed | Good when λ is properly scaled with dimension [1] [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in Bayesian Optimization |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) with RBF Kernel | Flexible surrogate model for approximating the unknown objective function; provides uncertainty estimates [5] [22] |

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | Method for estimating GP hyperparameters; crucial for avoiding vanishing gradients in high dimensions [19] |

| Quasi-Random Sequences | Initial experimental design for space-filling sampling in high-dimensional spaces [19] |

| Local Perturbation Strategies | Generating candidate points by perturbing current best candidates; enables local search behavior [19] |

| Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) | Non-GP surrogate model alternative for very high-dimensional problems [22] |

Experimental Protocol for High-Dimensional Bayesian Optimization

Protocol Title: Robust Bayesian Optimization in High-Dimensional Spaces

Background: This protocol addresses the unique challenges of applying Bayesian optimization to problems with dimensionality >20, where the curse of dimensionality causes data sparsity and model fitting issues [19] [20].

Materials Needed:

- Gaussian process surrogate model with configurable priors

- Acquisition function (EI, UCB, or PI)

- Optimization algorithm for acquisition function maximization

- Initial dataset (10-20×d points recommended)

Procedure:

Step 1: Initialization and Prior Configuration 1.1 Initialize GP length scales using dimensionally-scaled values (e.g., MSR initialization) [19] 1.2 Set priors appropriate for high dimensions (uniform U(10⁻³,30) or log-normal scaled by √d) [19] 1.3 Generate initial design using Latin Hypercube Sampling (50-100 points)

Step 2: Iterative Bayesian Optimization Loop 2.1 Fit GP model to current data, using multiple restarts to avoid poor local minima 2.2 Optimize acquisition function using hybrid approach (quasi-random sampling + local perturbation) 2.3 Select and evaluate next candidate point 2.4 Update dataset and repeat until evaluation budget exhausted

Step 3: Monitoring and Adjustment 3.1 Track length scale convergence and adjust initialization if vanishing gradients detected 3.2 Monitor exploration-exploitation balance through acquisition function values 3.3 Adjust acquisition function parameters if search becomes too exploratory or exploitative

Bayesian Optimization Troubleshooting Workflow

Troubleshooting Workflow for High-Dimensional Bayesian Optimization

Acquisition Function Relationships

Acquisition Function Types and Applications

Advanced Strategies and Real-World Applications in Drug Design and Materials Discovery

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the practical advantages of using a dynamic, multi-AF strategy over a single, static acquisition function? A dynamic strategy that switches between multiple acquisition functions (AFs) provides a more robust optimization process by adaptively balancing exploration and exploitation based on the current state of the model and the emerging knowledge of the landscape. A static AF might over-commit to exploration or exploitation at the wrong time. Research on an adaptive switch strategy demonstrated superior optimization efficiency on benchmark functions and a wind farm layout problem compared to using any single AF alone [23].

Q2: My Bayesian optimization is converging slowly on a high-dimensional "needle-in-a-haystack" problem. Which acquisition function should I try? For complex, high-dimensional landscapes like the Ackley function (a classic "needle-in-haystack" problem), recent empirical studies suggest that qUCB is a highly reliable choice. It has been shown to achieve faster convergence with fewer samples compared to other functions like qLogEI, particularly in noiseless conditions and in dimensions up to six [24]. Its performance also holds well when the landscape is unknown a priori.

Q3: How do I handle optimization when I have multiple, competing objectives? Multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MOBO) addresses this by seeking the Pareto front—the set of optimal trade-offs where improving one objective worsens another. You should use acquisition functions designed specifically for this scenario, such as qLogNoisyExpectedHypervolumeImprovement (qLogNEHVI) or Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) [25] [26]. These functions work by efficiently maximizing the hypervolume (the area dominated by the Pareto front) in the objective space.

Q4: I need to run experiments in batches to save time. What is the key consideration when choosing a batch AF? The central decision is between serial and parallel (Monte Carlo) batch picking strategies [24]. Serial approaches (like UCB with Local Penalization) select batch points one after another, penalizing areas around chosen points. Parallel approaches (like qUCB) select all points in a batch jointly by integrating over a joint probability density. For higher-dimensional problems (≥5-6 dimensions), Monte Carlo methods (e.g., qUCB, qLogEI) are often computationally more attractive and effective [24].

Q5: What does an adaptive acquisition function switching strategy look like in practice? A proven strategy involves alternating between two complementary acquisition functions. One study successfully used a switch between MSP (Mean Standard Error Prediction) for exploration and MES (Max-value Entropy Search) for exploitation [23]. The Kriging (Gaussian Process) surrogate model is iteratively retrained with intermediate optimal layouts, allowing the framework to progressively refine its predictions and accelerate convergence to the global optimum.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Optimization Gets Stuck in a Local Optimum

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-exploitation | Plot the surrogate model and acquired points. Check if new samples cluster in a small, non-optimal region. | Switch to or increase the weight of an exploration-focused AF, such as Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) with a higher β parameter, or use the Mean Standard Error Prediction (MSP) [23] [3]. |

| Poor AF Choice for Landscape | Evaluate the problem nature: Is it a "false optimum" (e.g., Hartmann) or "needle-in-haystack" (e.g., Ackley)? | Implement a dynamic switching strategy. For a "false optimum" landscape with noise, consider using qLogNEI [24]. |

Issue 2: Poor Performance with Noisy Experimental Measurements

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| AF not accounting for noise | Observe high volatility in objective values at similar input points. Check if the surrogate model uses a noise kernel. | Use acquisition functions designed for noisy settings, such as qLogNoisyExpectedImprovement (qLogNEI) or qLogNoisyExpectedHypervolumeImprovement (qLogNEHVI) for multi-objective problems [25] [24]. |

| Inadequate surrogate model | Review the model's kernel and its hyperparameters. A White Kernel can be added explicitly to model noise. | Ensure your Gaussian Process uses a kernel suitable for your data (e.g., Matern 5/2) and that it is configured to model heteroscedastic (non-constant) noise if present [14]. |

Issue 3: High Computational Cost of Multi-Objective or Batch Optimization

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient AF calculation | Profile your code to identify bottlenecks. Exact EHVI calculation can be slow for large Pareto fronts. | Leverage BoTorch's GPU-accelerated, Monte Carlo-based AFs like qLogEHVI and use its auto-differentiation capabilities for faster optimization [25]. |

| Inefficient batch selection | Compare the time taken to suggest a batch of points versus a single point. | For serial batch methods, ensure the local penalization function is correctly configured. For higher dimensions, switch to Monte Carlo batch AFs like qUCB, which are more computationally efficient [24]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing an Adaptive Switch Strategy

This methodology is based on the framework successfully applied to wind farm layout optimization [23].

- Initialization: Define the parameter space and select the AFs for switching (e.g., MSP for exploration, MES for exploitation). Generate an initial dataset using a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling.

- Surrogate Modeling: Train a Gaussian Process (Kriging) model on the current dataset.

- Acquisition & Switching:

- Use the current AF to propose the next sample point by optimizing the acquisition function.

- According to the cited research, alternate between MSP and MES according to a predefined schedule or a performance-based trigger [23].

- Evaluation & Update: Evaluate the expensive black-box function at the proposed point. Append the new {input, output} pair to the dataset.

- Iteration: Iteratively retrain the surrogate model and repeat steps 3-4 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., minimal improvement over several iterations).

Diagram: Adaptive AF Switching Workflow

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Optimization with EHVI

This protocol outlines the workflow for finding a Pareto front using Expected Hypervolume Improvement [25] [26].

- Define Objectives: Clearly state the multiple objectives to be optimized (e.g., maximize efficiency, minimize cost).

- Initial Sampling: Collect an initial set of observations that well-cover the design space.

- Pareto Front Identification: From the current data, compute the non-dominated set of points to establish the current Pareto front.

- Hypervolume Calculation: Calculate the hypervolume dominated by this Pareto front relative to a reference point.

- EHVI Acquisition: Use the EHVI acquisition function to determine the next point to evaluate—the one that promises the largest expected increase in this hypervolume.

- Iterate: Update the model and repeat until the Pareto front is sufficiently detailed.

Diagram: Multi-Objective BO with EHVI

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Acquisition Functions

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from a 2025 study that compared batch acquisition functions on standard benchmark problems [24].

Table 1: Batch AF Performance on Benchmark Functions (6-dimensional)

| Acquisition Function | Type | Ackley (Noiseless) | Hartmann (Noiseless) | Hartmann (Noisy) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qUCB | Monte Carlo Batch | Superior | Superior | Good (Faster convergence) | Best overall default; good noise immunity [24]. |

| UCB/LP | Serial Batch | Good | Good | Less Robust | Performs well in noiseless conditions [24]. |

| qLogEI | Monte Carlo Batch | Outperformed | Outperformed | Good (Faster convergence) | Converged slower than qUCB in noiseless tests [24]. |

Table 2: Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions in BoTorch [25]

| Acquisition Function | Class | Key Feature | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| qLogNEHVI | Monte Carlo | Improved numerics via log transformation; parallel candidate generation [25]. | Noisy multi-objective problems. |

| EHVI | Analytic | Exact gradients via auto-differentiation [25]. | Lower-dimensional or less noisy MO problems. |

| qLogNParEGO | Monte Carlo | Uses random scalarizations of objectives [25]. | Efficient optimization with many objectives. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

In the context of Bayesian optimization, the "research reagents" are the computational algorithms and software tools that form the essential components of an optimization campaign.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Advanced AF Methods

| Tool / Algorithm | Function / Role | Example Implementation / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Core surrogate model that provides predictions and uncertainty estimates for the black-box function. | Various (e.g., GPyTorch, scikit-learn). |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Balances exploration and exploitation via a simple formula: Mean + β * Standard Deviation. | Emukit, BoTorch (as qUCB) [24] [3]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Samples where the expected value over the current best is highest. A well-balanced, popular choice [3]. | BoTorch (as qLogEI), Ax, JMP [24] [27]. |

| Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) | For multi-objective problems; suggests points that maximize the volume of the dominated space. | BoTorch (analytic and MC versions) [25] [26]. |

| Local Penalization (LP) | A serial batch method that penalizes the AF around already-selected points to ensure diversity in the batch. | Emukit [24]. |

| Kriging Believer | A heuristic serial batch method that uses the GP's mean prediction as a temporary value for a selected point before evaluating the next. | Various Bayesian optimization libraries. |

| BoTorch Library | A framework for efficient Monte-Carlo Bayesian optimization in PyTorch, providing state-of-the-art AFs. | BoTorch (qLogNEHVI, qUCB, etc.) [25] [24]. |

Diagram: Batch AF Selection Guide

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common technical challenges researchers face when using Large Language Models (LLMs) like FunSearch to generate and test novel acquisition functions for Bayesian Optimization (BO).

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my Bayesian Optimization perform poorly when optimizing high-dimensional functions?

BO's performance often deteriorates in high-dimensional spaces (typically beyond 20 dimensions) due to the curse of dimensionality [28]. The volume of the search space grows exponentially with the number of dimensions, making it difficult for the surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process) to effectively learn the objective function's structure from a limited number of samples. This is not unique to BO but affects many optimization algorithms. Solutions include making structural assumptions, such as sparsity (assuming only a few dimensions are important), or exploiting the intrinsic lower dimensionality of the problem using linear or nonlinear projections [28].

Q2: My BO algorithm seems to get stuck in local optima or stops exploring. What could be wrong?

This is often related to an imbalance between exploration and exploitation in your acquisition function. The ϵ (epsilon) parameter in the Probability of Improvement (PI) acquisition function, for instance, explicitly controls this balance [2]. A value that is too low can lead to over-exploitation (getting stuck), while a value that is too high can lead to excessive, inefficient exploration. Furthermore, an incorrect prior width or inadequate maximization of the acquisition function itself can also cause poor performance [5]. Diagnosing and tuning these hyperparameters is crucial.

Q3: I am encountering an ImportError related to 'colorama' when trying to use a Bayesian optimization library. How can I resolve this?

This is a known dependency issue with certain versions of the bayesian-optimization Python package. The problem arises from a breaking change in a dependency. You can resolve it by downgrading the library to a stable version. Run the following command in your environment [29]:

Q4: How can I ensure that the novel acquisition functions generated by FunSearch are interpretable and provide insights?

A key advantage of FunSearch is that it outputs programs (code) that describe how solutions are constructed, rather than being a black box [30]. The system favors finding solutions represented by highly compact programs (low Kolmogorov complexity). These short programs can describe very large objects, making the outputs easier for researchers to comprehend and inspect for intriguing patterns or symmetries that can provide new scientific insights [30].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: High ground-state line error when using BO for cluster expansion in materials science.

- Description: When building a convex hull to predict stable material phases, the Ground-State Line Error (GSLE) remains high, meaning the observed convex hull is inaccurate.

- Potential Causes:

- The acquisition function is not efficiently exploring the composition space.

- The batch of configurations selected for expensive DFT calculations does not optimally reduce uncertainty about the true convex hull.

- Solutions:

- Consider using specialized acquisition functions like EI-hull-area or EI-below-hull, which are specifically designed for convex hull problems. These prioritize configurations that maximize the area/volume of the predicted convex hull or minimize the distance to it, leading to more efficient exploration [31].

- Compare the performance of your acquisition function against genetic algorithm-based methods (GA-CE-hull) as a baseline [31].

Problem: The discovered acquisition function does not generalize well to functions outside the training distribution.

- Description: An acquisition function discovered by an LLM performs well on the type of objective functions it was trained on but fails on a different class of functions.

- Potential Cause: The training set of functions was not diverse enough, leading to overfitting.

- Solutions:

- When using a method like FunBO, ensure the set of auxiliary functions (

𝒢) used for training is as diverse and representative as possible of the real-world functions you intend to optimize [32]. - The FunBO method itself has been shown to produce acquisition functions that generalize better outside their training distribution compared to other learned approaches, so leveraging this framework can be beneficial [32].

- When using a method like FunBO, ensure the set of auxiliary functions (

Experimental Protocols & Data

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in the field, enabling replication and validation of research findings.

Protocol 1: Discovering Novel Acquisition Functions with FunBO

This protocol outlines the process for using the FunBO method to discover new acquisition functions [32].

- Problem Formulation: Define the problem as discovering an acquisition function

α(x)that maximizes the performance of a BO algorithm across a set of training functions. - Initialization: Select an initial acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to serve as a starting point for the evolutionary process.

- Evolutionary Loop: Iteratively improve the acquisition function using FunSearch:

- Selection: Choose high-scoring programs (acquisition functions) from the current pool.

- LLM Prompting: Feed these programs to a large language model (e.g., PaLM 2, Gemini 1.5). The LLM creatively builds upon them to generate new candidate programs.

- Evaluation: Automatically evaluate each new candidate

afby running a BO loop on a set of auxiliary objective functions𝒢 = {g_j}. The performance is typically measured by the average simple regret or its logarithm. - Scoring: The score of a program is its average performance across the different functions in

𝒢. - Promotion: The best-performing candidates are added back to the program pool.

- Output: The final output is the code of the best-performing acquisition function, which can be inspected, understood, and deployed.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the FunBO discovery process.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Acquisition Functions on Convex Hull Problems

This protocol is for benchmarking acquisition functions on materials science problems involving the determination of a convex hull for cluster expansion [31].

- System Setup: Select a material system (e.g., Co-Ni binary alloy, Zr-O oxides) with a known target convex hull based on a large set of Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations.

- Initialization: Start with a small set of initial data points (e.g., 32 configurations with known formation energies).

- Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Surrogate Model: Fit a Bayesian-Gaussian (BG) model (Cluster Expansion) to the current set of observations.

- Acquisition: Use the acquisition function under test (e.g., EI-hull-area, EI-below-hull, EI-global-min) to select a batch of up to

knew configurations for evaluation. - Evaluation: "Evaluate" the selected configurations by adding their true formation energy (from the pre-computed dataset) to the observation set.

- Metric Calculation: After each iteration, compute the Ground-State Line Error (GSLE). The GSLE is the normalized difference between the current convex hull

E_C(x)and the target convex hullE_T(x)across the composition range (Equation 1, [31]). A lower GSLE indicates better performance. - Termination: Repeat the BO loop for a fixed number of iterations or until the GSLE falls below a desired threshold.

The performance of different acquisition functions can be quantitatively compared by plotting the GSLE against the number of iterations or the total number of observations.

Table 1: Comparison of Acquisition Functions for Convex Hull Learning in a Co-Ni Alloy System [31]

| Acquisition Function | Key Principle | Observations after 10 Iterations | Final GSLE (Relative Performance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EI-hull-area | Maximizes the area/volume of the convex hull | ~78 | Lowest (Best) |

| GA-CE-hull | Genetic algorithm-based selection | ~77 | Medium |

| EI-below-hull | Minimizes distance to the convex hull | 87 | Medium |

| EI-global-min | Focuses on the global minimum energy | 87 | Highest (Poorest) |

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details key computational reagents and resources essential for conducting experiments in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FunSearch Framework | An evolutionary procedure pairing an LLM with an evaluator to generate solutions expressed as computer code. | Used to discover new scientific knowledge and algorithms, such as novel acquisition functions [30]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A probabilistic surrogate model that provides a posterior distribution over the objective function, estimating both mean and uncertainty. | The core of Bayesian Optimization; used by the acquisition function to balance exploration and exploitation [5] [2]. |

| Large Language Model (LLM) | Provides creative solutions in the form of computer code by building upon existing programs. | Google's PaLM 2 or Gemini 1.5 Flash can be used within FunSearch. Generalist LLMs are now sufficient, no longer requiring code-specialized models [30] [32]. |

| Standard Acquisition Functions | Benchmarks and starting points for discovery. Include Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), and Probability of Improvement (PI). | EI is often the default choice due to its good balance of exploration and exploitation [5] [2]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Library | Provides the core infrastructure for running BO loops. | e.g., bayesian-optimization Python library (note: use v1.4.1 to avoid dependency issues) [29]. |

| Cluster Expansion Model | A surrogate model that approximates the energy of a multi-component material system based on its atomic configurations. | Used in materials science to predict formation energies for convex hull construction [31]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the core limitation of standard Bayesian Optimization (BO) for complex scientific goals? Standard BO frameworks are primarily designed for single-objective optimization (finding a global optimum) or full-function mapping. Complex experimental goals in materials science and drug discovery often require finding specific subsets of the design space that meet multi-property criteria or discovering a diverse Pareto front. Using standard acquisition functions like Expected Improvement (EI) for these tasks is inefficient because the acquisition function is not aligned with the experimental goal [33].

How can I define a "complex goal" for my BO experiment? A complex goal is defined as finding the target subset of your design space where user-defined conditions on the measured properties are met [33]. Examples include:

- Identifying all synthesis conditions that produce nanoparticles within a specific size range [33].

- Finding a diverse set of high-performing catalysts that also minimize cost and synthesis time [34].

- Accurately mapping a specific phase boundary in a materials system [33].

My multi-objective BO is converging to a narrow region of the Pareto front. How can I improve diversity? A common drawback of existing methods is that they evaluate diversity in the input space, which does not guarantee diversity in the output (objective) space [34]. To improve Pareto front diversity:

- Use frameworks like Pareto front-Diverse Batch Multi-Objective BO (PDBO) that explicitly maximize diversity in the objective space [34].

- Employ a Determinantal Point Process (DPP) with a kernel designed for multiple objectives to select a batch of points that are diverse in the Pareto space [34].

Are there parameter-free strategies for targeted discovery to avoid tedious acquisition function design? Yes. The Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) framework allows you to specify your goal via a simple filtering algorithm. This algorithm is automatically translated into an intelligent data collection strategy, bypassing the need for custom acquisition function design [33]. The framework provides strategies like:

- InfoBAX: Selects points that maximize information gain about the target subset.

- MeanBAX: Uses the model's posterior mean to estimate the target subset.

- SwitchBAX: A parameter-free method that dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX for robust performance across different data regimes [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor optimization performance due to uninformed initial sampling.

- Background: The initial samples used to build the first surrogate model are critical. A poor initial spread can lead to the optimization getting stuck in a local region [35].

- Solution:

- Instead of purely random sampling, use space-filling designs like Sobol sequences or Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) [36].

- These methods ensure a broad and representative coverage of the search space with a small number of points, providing a better initial model for the BO algorithm to build upon [35] [36].

Problem: The surrogate model overfits with limited data, leading to poor suggestions.

- Background: With few data points, a Gaussian Process (GP) model with an inappropriate kernel can overfit, misrepresenting the true objective function landscape [35].

- Solution:

- Robust Kernel Selection: Choose flexible kernels like the Matern kernel, which is a common default choice for modeling realistic functions [35].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Adaptively tune the GP model's hyperparameters (e.g., by maximizing the marginal likelihood) as more data becomes available to better capture the underlying function dynamics [35].

Problem: Standard BO becomes intractable for high-dimensional problems (e.g., >20 parameters).

- Background: The computational cost of BO grows rapidly with dimensionality, making it challenging for problems with hundreds of parameters [36].

- Solution:

- Utilize advanced algorithms like Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace Bayesian Optimization (SAASBO) [36].

- SAASBO uses a sparsity-inducing prior that assumes only a small subset of parameters significantly impact the objective, effectively "turning off" irrelevant dimensions and making high-dimensional optimization feasible [36].

Problem: My multi-objective BO fails to dynamically select the best acquisition function.

- Background: The performance of an acquisition function can vary during different stages of the optimization process. Relying on a single one can be sub-optimal [34].

- Solution:

- Implement a multi-armed bandit strategy to dynamically select an acquisition function from a library (e.g., EI, UCB, PI) in each BO iteration [34].

- Define a reward function for the bandit based on the optimization progress, allowing the system to automatically favor the best-performing acquisition function over time [34].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing Targeted Subset Discovery with the BAX Framework This protocol is based on the methodology described in Targeted materials discovery using Bayesian algorithm execution [33].

- Define Design Space: Let your discrete set of

Npossible experimental conditions beX. - Define Goal via Algorithm: Write a simple algorithm

Algothat, if given the true functionf*, would return your target subsetT*(e.g., all pointsxwhere propertyyis betweenaandb). - Select BAX Strategy: Choose an execution strategy such as

SwitchBAXfor automatic performance. - Sequential Data Collection:

- For

t = 1tomax_evaluations: - Fit a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model to all observed data

(X_observed, Y_observed). - Use the BAX strategy (e.g., InfoBAX) to calculate the next point

x_tthat provides the most information about the subsetAlgowould return. - Evaluate the expensive experiment at

x_tto gety_t. - Update the observed dataset.

- For

- Output Final Set: After the loop, run the algorithm

Algoon the posterior mean of the final GP model to output the estimated target subset.

Protocol 2: Pareto-Front Diverse Batch Multi-Objective Optimization This protocol is adapted from Pareto Front-Diverse Batch Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization [34].

- Problem Setup: Define your

Kexpensive objective functions{f1, ..., fK}to minimize over an input space𝔛. - Initialization: Sample an initial set of points using a Sobol sequence and evaluate them on all

Kobjectives. - BO Iteration:

- Step 1 - Dynamic AF Selection: Use a multi-armed bandit to select one acquisition function (AF) from a predefined library.

- Step 2 - Candidate Generation: For each objective

fi, treat the selected AF as a cheap-to-evaluate function. Solve a cheap multi-objective optimization problem across theseKAFs to obtain a candidate Pareto set. - Step 3 - Diverse Batch Selection: From the candidate set, use a Determinantal Point Process (DPP) configured for multi-objective output diversity to select the final

Bpoints for parallel evaluation.

- Evaluation & Update: Evaluate the

Bpoints on the true expensive objectives. Update the surrogate models (GPs) and the bandit parameters with the new results. - Repeat: Repeat steps 3-4 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., budget exhaustion).

Quantitative Comparison of Acquisition Functions for Single-Objective Optimization

| Acquisition Function | Key Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) [3] | Selects point with the highest expected improvement over the current best. | Well-balanced performance; general-purpose use [3]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) [3] | Selects point with the highest probability of improving over the current best. | Pure exploitation; refining known good regions [36]. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [3] | Selects point maximizing mean(x) + κ * std(x), where κ balances exploration/exploitation. |

Explicit control over the exploration-exploitation trade-off [36]. |

Metrics for Evaluating Multi-Objective Optimization Performance

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Hypervolume [36] | The n-dimensional volume of the space dominated by the Pareto front and bounded by a reference point. | A larger hypervolume indicates a higher-quality Pareto front (closer to the true optimum and more spread out) [36]. |

| Diversity of Pareto Front (DPF) [34] | The average pairwise distance between points in the Pareto front (in the objective space). | A larger DPF indicates a more diverse set of solutions, giving practitioners more options to choose from [34]. |

Workflow Diagrams

BAX Framework for Targeted Discovery

Diverse Batch Multi-Objective BO (PDBO)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Software and Computational Tools for Advanced BO

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| scikit-optimize | A Python library that provides a simple and efficient implementation of BO, including the gp_minimize function for easy setup [35]. |

| BOTORCH/Ax | A framework for state-of-the-art Monte Carlo BO, built on PyTorch. It is highly flexible and supports advanced features like multi-objective, constrained, and multi-fidelity optimization [3]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) | The core probabilistic model (surrogate) used to approximate the expensive black-box function and quantify prediction uncertainty [36]. |

| Matern Kernel | A flexible covariance kernel for GPs, often preferred over the RBF kernel as it can model functions with less smoothness, making it suitable for real-world physical processes [35]. |

| Sobol Sequences | A quasi-random algorithm for generating space-filling initial designs. It provides better coverage of the search space than random sampling, leading to a more informed initial surrogate model [36]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: Our Bayesian optimization (BO) campaign seems to get stuck in local maxima, selecting compounds with poor experimental confirmation. How can we improve its robustness to noise?

This is a common issue when experimental noise misleads the acquisition function. A two-pronged approach is recommended:

- Implement a Retest Policy: Do not assume a single assay reading is ground truth. Integrate a policy that selectively retests compounds, especially those identified as highly active by the model. This confirms true activity and prevents the model from being skewed by false positives. In batched BO, this can be managed by dedicating a portion of each batch's experimental budget to retesting the most promising compounds from previous batches [37].

- Choose a Noise-Robust Acquisition Function: In noisy environments, the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function often outperforms purely greedy strategies. EI inherently balances the mean prediction and the model's uncertainty, making it more resilient to noise compared to methods that only consider the predicted mean [37].

FAQ 2: How should we allocate our limited experimental budget between testing new compounds and retesting existing ones?

There is no universal fixed ratio, as the optimal allocation depends on your specific noise level. The strategy should be adaptive.

- A robust method is to treat retests as an integral part of the batch selection process. When constructing a new batch of experiments, the algorithm should select a mix of new candidate compounds (based on the acquisition function) and existing compounds flagged for verification. The total number of experiments in the batch should remain constant to maintain the budget. Research indicates that this dynamic retest policy consistently allows more active compounds to be correctly identified when noise is present [37].

FAQ 3: Our assays have vastly different costs and fidelities (e.g., computational docking vs. single-point assays vs. dose-response curves). How can Bayesian optimization account for this?

A Multifidelity Bayesian Optimization (MF-BO) approach is designed for this exact scenario. MF-BO extends the standard BO framework to optimize across different levels of experimental fidelity [38].

- The surrogate model learns the correlation between low-fidelity, high-throughput assays (like docking) and high-fidelity, low-throughput assays (like IC50 measurements) across the chemical space.

- The acquisition function is modified to select not only which compound to test but also at which fidelity to test it, explicitly weighing the cost of an experiment against the potential information gain. This allows the algorithm to cheaply screen large areas of chemical space with low-fidelity methods and strategically invest in high-fidelity experiments only for the most promising candidates [38].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Batched Bayesian Optimization with a Dynamic Retest Policy for Noisy Assays

This protocol is adapted from successful applications in drug design where assay noise is a significant factor [37].

1. Initialization:

- Input: A large chemical library (e.g., 5000-10000 compounds).

- Initial Batch: Randomly select and test an initial batch of 100 compounds to provide baseline data.

- Surrogate Model: Train an initial surrogate model (e.g., Random Forest or Gaussian Process with Morgan fingerprints) on this data.

2. Iterative Batch Selection and Testing: For each subsequent batch (e.g., 100 experiments per batch):

- Model Prediction: Use the current surrogate model to predict the activity (mean, μ̂(x)) and uncertainty (σ̂(x)) for all untested compounds.

- Acquisition Function: Calculate an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound) for all untested compounds.

- Candidate Selection: Rank the untested compounds by their acquisition score.

- Dynamic Batch Construction:

- Select the top

N_newcompounds from the ranked list for first-time testing. - Identify

N_retestcompounds from previously tested batches that have high predicted activity but high uncertainty or are candidates for verification. The sumN_new + N_retestequals the batch size (e.g., 100). - Retest Policy Note: The selection of retest candidates can be based on criteria such as high model prediction with a previously high noise reading, or compounds near the current best-performing ones.

- Select the top

- Experiment Execution: Perform the assays for the selected

N_newnew compounds andN_retestretest compounds. - Model Update: Add the new experimental results (including retest data) to the training set and update the surrogate model.

- Repeat until the experimental budget is exhausted or a performance criterion is met.

3. Key Parameters:

- Batch Size: Typically 100 for large libraries [37].

- Acquisition Function: Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) with β=2 have proven effective in noisy settings [37].

- Retest Ratio: Dynamically determined each batch; not a fixed percentage.

Protocol 2: Multifidelity Bayesian Optimization for Drug Discovery

This protocol leverages experiments of different costs and accuracies to accelerate discovery, as demonstrated in autonomous platform screening for histone deacetylase inhibitors [38].

1. Fidelity Definition and Cost Assignment:

- Define at least two levels of experimental fidelity. A common setup is:

- Low-Fidelity (LF): Computational docking (Cost = 0.01).

- Medium-Fidelity (MF): Single-point percent inhibition assay (Cost = 0.2).

- High-Fidelity (HF): Dose-response IC50 assay (Cost = 1.0).

- Set a per-iteration budget (e.g., 10.0 cost units).

2. Initialization:

- Obtain initial data for all fidelities for a small, random subset of molecules (e.g., 5% of the library) to allow the model to learn inter-fidelity correlations.

3. Iterative Molecule-Fidelity Pair Selection: For each iteration until the total budget is spent:

- Surrogate Modeling: Train a Multifidelity Gaussian Process model on all accumulated data. The model uses a Tanimoto kernel with Morgan fingerprints and learns to predict the outcome at the highest fidelity based on all lower-fidelity data.

- Acquisition Function Optimization: Use a multi-step Monte Carlo approach (e.g., based on Expected Improvement) to select the next set of experiments. The acquisition function evaluates the utility of testing a specific molecule at a specific fidelity, considering the cost.

- Experiment Execution: Synthesize and test the selected molecule-fidelity pairs without exceeding the iteration budget.

- Data Integration: Add the new results to the training dataset.

4. Outcome: The process identifies high-performing molecules (e.g., submicromolar inhibitors) while strategically using cheaper assays to explore the chemical space and expensive assays only for validation [38].

Workflow Diagrams

Batched Bayesian Optimization with Retest Policy

Multifidelity Experimental Funnel

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational and experimental reagents for implementing Bayesian optimization in drug discovery.

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Function in the Workflow | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints | Molecular Descriptor | Represents chemical structure for the surrogate model. A 1024-bit, radius 2 fingerprint is commonly used [37] [38]. | Generated using toolkits like RDKit. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Surrogate Model | Probabilistic model that predicts compound activity and associated uncertainty. Essential for acquisition functions like EI. | Can use a Tanimoto kernel for molecular fingerprints [38]. |

| Random Forest | Surrogate Model | An alternative machine learning model for activity prediction, often used in batched BO for QSAR [37]. | Implemented in scikit-learn. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Acquisition Function | Guides experiment selection by balancing predicted performance and uncertainty; robust in noisy settings [37]. | A key alternative to purely greedy selection. |

| Multi-fidelity Model | Surrogate Model | Extends GP to learn correlations between different assay types (e.g., docking scores and IC50 values) [38]. | Core of the MF-BO approach. |

| CHEMBL / PubChem | Data Source | Provides publicly available bioactivity data for building initial models and validating approaches [37]. | AID-1347160, AID-1893 are example assays. |

Diagnosing and Overcoming Common Pitfalls in Bayesian Optimization

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Robust Experimental Optimization. This resource is designed for researchers and scientists employing Bayesian Optimization (BO) to guide expensive and complex experiments, particularly in domains like drug development and materials science. A central challenge in these settings is experimental noise—random variations in measurements that can obscure the true objective function and misguide the optimization process. This article provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you implement strategies that make your BO workflows robust to such noise.

#2 Core Concepts: Noise and Its Impact on Bayesian Optimization

FAQ: What types of noise are most problematic for BO?

Experimental noise in BO can be broadly categorized, each requiring a specific mitigation strategy:

- Measurement Noise: Inherent variability in the instrument or process used to evaluate a sample. This is often a function of experimental time or parameters.

- System Variability: Uncontrolled fluctuations in experimental conditions (e.g., ambient temperature, reagent batch effects).

- Process Noise: Intrinsic stochasticity of the system under study.

FAQ: How does noise specifically degrade the performance of Bayesian Optimization?

Noise directly impacts the two core components of the BO loop [39]: