Optimal Experimental Design for Materials Discovery: Bayesian Methods, AI, and Self-Driving Labs

This article provides a comprehensive overview of optimal experimental design (OED) frameworks that are transforming materials discovery from a traditional, trial-and-error process into an efficient, informatics-driven practice.

Optimal Experimental Design for Materials Discovery: Bayesian Methods, AI, and Self-Driving Labs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of optimal experimental design (OED) frameworks that are transforming materials discovery from a traditional, trial-and-error process into an efficient, informatics-driven practice. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational Bayesian principles that quantify uncertainty and enable intelligent data acquisition. We delve into advanced methodological frameworks like Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) and Mean Objective Cost of Uncertainty (MOCU) for targeting specific material properties. The review also addresses critical challenges in troubleshooting and optimization, such as managing multi-fidelity data and model fusion. Finally, we examine validation strategies and the comparative performance of OED against high-throughput screening, concluding with the transformative potential of self-driving labs in closing the loop between AI-based design and physical validation.

The Principles of Optimal Experiment Design: From Trial-and-Error to Informed Discovery

The field of materials discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving away from brute-force high-throughput screening (HTS) toward intelligent, goal-oriented design strategies. This paradigm shift is driven by the integration of machine learning (ML), optimal experiment design, and physics-based computational models, enabling researchers to navigate complex materials spaces with unprecedented efficiency. Where traditional HTS relies on rapid, parallelized testing of vast compound libraries, goal-oriented approaches leverage adaptive algorithms to select the most informative experiments, dramatically reducing the number of trials needed to identify materials with targeted properties. This article details the theoretical foundations, practical protocols, and essential toolkits for implementing these advanced methodologies, framed within the broader context of optimal experimental design for accelerated materials discovery.

Traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) is defined as the use of automated equipment to rapidly test thousands to millions of samples for biological or functional activity [1]. In materials science and drug development, HTS typically involves testing compounds in microtiter plates (96-, 384-, or 1536-well formats) at single or multiple concentrations (quantitative HTS) to identify "hits" with desired characteristics [1]. While effective for exploring defined chemical spaces, conventional HTS approaches face significant limitations: they are resource-intensive, often test compounds indiscriminately, and struggle with vast, multidimensional design spaces where the interplay of structural, chemical, and microstructural degrees of freedom creates exponential complexity [2] [3].

The emerging paradigm of goal-oriented design addresses these limitations by framing materials discovery as an optimal experiment design problem [3]. This approach does not merely seek to accelerate experimentation but to make it intelligent—using available data and physical knowledge to sequentially select experiments that maximize information gain toward a specific objective. This shift is enabled by key advancements:

- Machine Learning and AI: ML models can predict material properties and identify complex patterns from existing data, guiding exploration [4] [5].

- Optimal Experimental Design (OED): Frameworks like the Mean Objective Cost of Uncertainty (MOCU) quantify how model uncertainty affects design objectives and identify measurements that optimally reduce this uncertainty [2].

- Hybrid Physical-Data-Driven Modeling: Integrating physics-based simulations with data-driven models ensures predictions are both accurate and physically plausible [6] [7].

Table 1: Core Differences Between High-Throughput Screening and Goal-Oriented Design

| Aspect | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Goal-Oriented Design |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Test as many samples as possible; "brute force" exploration | Intelligently select few, highly informative samples; "directed" exploration |

| Data Usage | Analyzes data after collection to identify hits | Uses data and models to actively decide the next experiment |

| Efficiency | High numbers of experiments; can be wasteful | Minimizes number of experiments; resource-efficient |

| Underpinning Tools | Robotics, automation, liquid handling | Machine Learning, Bayesian Optimization, Physics-Based Simulation |

| Best Suited For | Well-defined spaces with clear assays | Complex, multi-parameter optimization with resource constraints |

Foundational Concepts and Frameworks

Bayesian Optimization and Expected Improvement

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a cornerstone of goal-oriented design. It balances the exploitation of known promising regions with the exploration of uncertain regions [3]. A common acquisition function used within BO is Expected Improvement (EI), which selects the next experiment based on the highest expected improvement over the current best outcome.

Mean Objective Cost of Uncertainty (MOCU)

The MOCU framework quantifies the deterioration in the performance of a designed material due to model uncertainty. The core idea is to select the next experiment that is expected to most significantly reduce this cost [2]. The general MOCU-based experimental design algorithm involves:

- Start with a prior distribution

f(θ)over uncertain parametersθ. - Compute the robust design

ζ*that minimizes the expected costJ(ζ)given the current uncertainty. - For each candidate experiment

e, compute the Expected Remaining MOCU after conductinge. - Select and run the experiment

e*that minimizes the Expected Remaining MOCU. - Update the prior distribution

f(θ)with the new experimental result. - Repeat until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., MOCU falls below a threshold) [2].

Goal-Directed Generative Models

For the de novo design of molecular materials, goal-directed generative models use deep reinforcement learning to create novel chemical structures that satisfy multiple target properties. Models like REINVENT are trained on a chemical space of interest and then fine-tuned using a multi-parameter optimization (MPO) scoring function that encodes design objectives [7]. This allows for the inverse design of materials, moving directly from desired properties to candidate structures.

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: MOCU-Based Experimental Design for Shape Memory Alloys

This protocol outlines the application of the MOCU framework to minimize energy dissipation in shape memory alloys (SMAs), as demonstrated by [2].

Objective: Identify material/composition parameters that minimize hysteresis energy dissipation during superelastic loading-unloading cycles.

Background: The stress-strain response of SMAs is modeled using a Ginzburg-Landau-type phase field model. The model parameters (e.g., h and σ) are uncertain and are influenced by chemical doping. The goal is to guide "chemical doping" (parameter variation) to find the optimal configuration [2].

Materials and Computational Tools:

- Phase-field simulation code for SMA hysteresis.

- Statistical computing environment (e.g., Python/R) for MOCU calculation.

Procedure:

- Define Uncertainty Class: Identify the vector of uncertain model parameters

θ = [h, σ]and their joint prior distributionf(h, σ). - Specify Objective Function: Define the cost function

J(ζ)as the energy dissipation (area of hysteresis loop) for a designζ. - Initial Robust Design: Compute the initial robust design

ζ*that minimizes the expected costE_θ[J(ζ)]. - Candidate Experiment Selection: For each candidate experiment (e.g., testing a specific dopant concentration

i), calculate the Expected Remaining MOCU:ERMOCU(i) = E[ MOCU(i) | X_i,c ]whereX_i,cis the (random) outcome of the experiment. - Next Experiment: Select the candidate experiment

i*with the smallest ERMOCU. - Execute and Update: Perform the selected experiment (or simulation), obtain the outcome

x, and update the prior distribution to the posteriorf(h, σ | X_i,c = x)using Bayes' theorem. - Iterate: Repeat steps 3-6 until the MOCU is sufficiently reduced or a performance target is met.

Validation: The performance of this design strategy can be evaluated by comparing it to a random selection strategy, showing a significantly faster reduction of energy dissipation towards the true minimum [2].

Protocol 2: Goal-Directed Generative Design of OLED Materials

This protocol describes a goal-directed generative ML framework for designing novel organic light-emitting diode (OLED) hole-transport materials, based on the work of [7].

Objective: Generate novel molecular structures for hole-transport materials with optimal HOMO/LUMO levels, low hole reorganization energy, and high glass transition temperature.

Background: A recurrent neural network (RNN)-based generative model is used to propose new molecular structures represented as SMILES strings. The model is trained on a chemical space relevant to organic electronics and is then fine-tuned towards the multi-property objective [7].

Materials and Computational Tools:

- Software: REINVENT or similar goal-directed generative ML platform.

- Data: A curated library of core structures and R-groups from known hole-transport materials.

- Computational Chemistry Suite: (e.g., Schrödinger Materials Science Suite) for high-throughput property calculation.

Procedure:

- Prior Network Training:

- Assemble a training set of 2+ million enumerated structures from curated cores and R-groups.

- Train a prior generative neural network on this dataset to learn the general syntax and structural motifs of the chemical space.

- Scorer Network Training:

- Use high-throughput quantum chemistry simulations (e.g., DFT) to compute target properties (HOMO, LUMO, reorganization energy, Tg) for a subset of the training library.

- Train a separate scorer network to accurately predict these properties from a molecular structure.

- Define Multi-Parameter Optimization (MPO):

- Develop a single utility (scoring) function that combines the four target properties into a single MPO score, reflecting the overall desirability of a candidate molecule.

- Fine-Tune with Reinforcement Learning:

- Use the REINVENT protocol to fine-tune the prior network. The model is rewarded for generating structures that the scorer network predicts will have a high MPO score.

- Run the fine-tuned model to generate tens of thousands of novel candidate structures.

- Validation and Downstream Selection:

- Select top-ranking candidates from the generative run.

- Perform more accurate (and computationally expensive) quantum chemistry calculations on these top candidates to validate the predictions before proceeding to synthesis.

Key Advantage: This method explores a vast chemical space with minimal human design bias and directly proposes novel, synthetically accessible candidates optimized for multiple target properties [7].

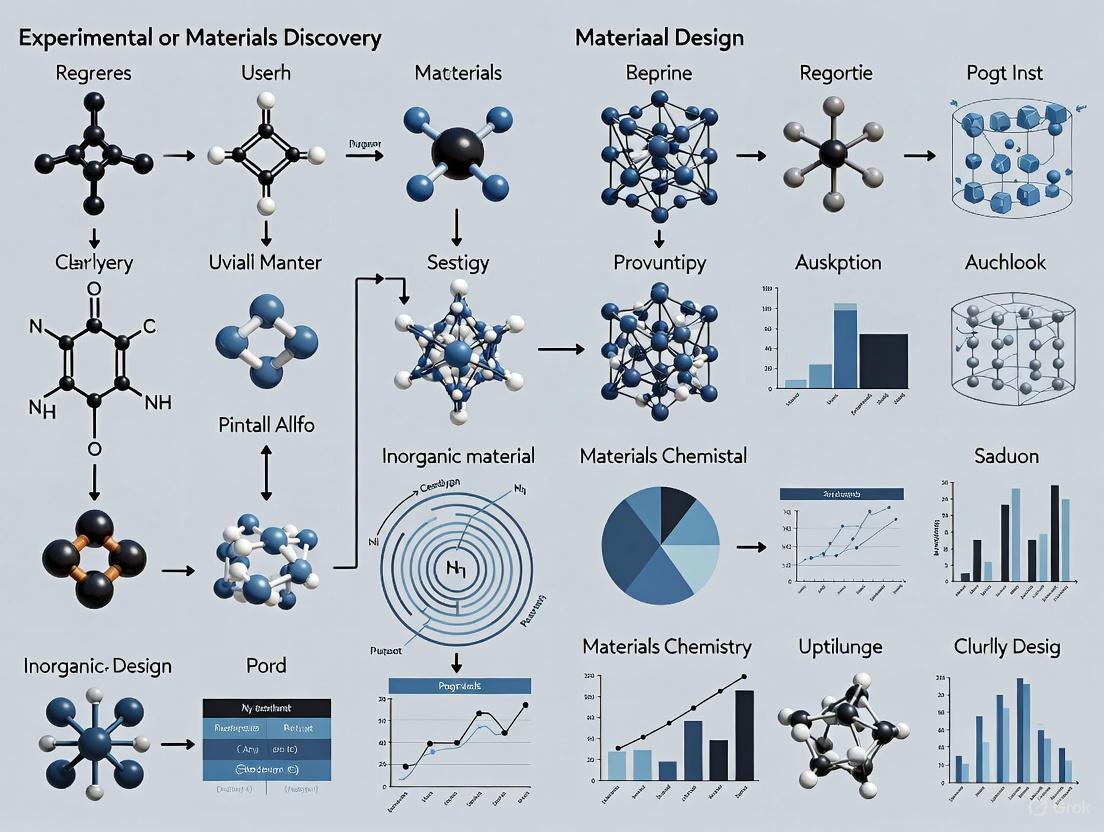

Diagram 1: Generative design workflow for OLED materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Goal-Oriented Materials Discovery

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Quantum Chemistry (HTQC) | Rapid, automated computation of electronic, thermal, and structural properties for thousands of molecules. | Generating training data for the scorer network in generative ML [7]. |

| Gradient Material Libraries | Physical sample libraries where composition or process parameters vary systematically across a single substrate. | Exploring a wide parameter space in additive manufacturing to map process-property relationships [8]. |

| Automated Robotic Platforms (Robot Scientists) | Integrated systems that automate material synthesis, characterization, and testing with minimal human intervention. | Conducting autonomous, closed-loop experiments guided by a Bayesian optimization algorithm [4]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | ML models that operate directly on graph representations of molecules/crystals, learning structure-property relationships. | Accurate prediction of material properties from crystal structure for virtual screening [4] [6]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | Libraries (e.g., GPyOpt, BoTorch) that implement acquisition functions like EI and KG for experiment design. | Sequentially selecting the next synthesis condition to test in a catalyst optimization campaign [3]. |

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

Combining the principles above leads to a powerful, generalized workflow for goal-oriented materials discovery. This integrated framework closes the loop between computation, experiment, and data analysis.

Diagram 2: The iterative cycle of goal-oriented discovery.

The transition from high-throughput screening to goal-oriented design represents a maturation of the scientific process in materials discovery. By leveraging machine learning, optimal experimental design, and high-performance computing, researchers can now move beyond indiscriminate testing to intelligent, adaptive investigation. The protocols and frameworks detailed herein—from MOCU-based sequential design to generative molecular discovery—provide a concrete roadmap for implementing this paradigm shift. As these methodologies continue to evolve and integrate with automated laboratories, they promise to dramatically accelerate the development of next-generation functional materials for applications ranging from energy storage to pharmaceuticals.

The discovery and development of new functional materials are fundamental to advancements across science, engineering, and biomedicine. Traditional discovery processes, which often rely on trial-and-error campaigns or high-throughput screening, are inefficient for exploring vast design spaces due to constraints in time, resources, and cost [9]. A paradigm shift towards informatics-driven discovery is underway, with Bayesian frameworks playing a pivotal role. These frameworks provide a rigorous mathematical foundation for quantifying uncertainty, a critical element for guiding optimal experimental design (OED) under the constraints typical of materials science research [9]. By formally representing uncertainty in models and data, Bayesian methods enable researchers to make robust decisions about which experiment to perform next, significantly accelerating the path to discovering materials with targeted properties.

Core Mathematical Principles

The application of Bayesian principles to experimental design involves a specific mathematical formulation aimed at managing uncertainty to achieve an operational objective.

The Bayesian Framework for Optimal Operators

The core problem can be framed as the design of an optimal operator, such as a predictor or a policy for selecting experiments. When the true model of a materials system is unknown, the goal becomes designing a robust operator that performs well over an entire uncertainty class of models, denoted as Θ. A powerful alternative to minimax robust strategies is the Expected Cost of Uncertainty (ECU) [9]. For an operator ψ, the cost for a particular model θ is C_θ(ψ). If the true model were known, one could design an optimal operator ψ_θ. The cost of uncertainty is thus the difference in performance between the optimal operator for the true model and the robust operator chosen under uncertainty. The ECU is the expectation of this cost over the prior distribution π(θ):

ECU = E_π [C_θ(ψ_θ) - C_θ(ψ)]

The optimal robust operator ψ* is the one that minimizes this expected cost:

ψ* = argmin_ψ E_π [C_θ(ψ_θ) - C_θ(ψ)]

This formulation directly quantifies the expected deterioration in performance due to model uncertainty and selects an operator to minimize it [9]. This objective-based uncertainty quantification is central to the Mean Objective Cost of Uncertainty (MOCU) framework, which has been successfully applied to materials design problems, such as reducing energy dissipation in shape memory alloys by sequentially selecting the most effective "dopant" experiments [2].

Foundational Components of Bayesian Learning and OED

A practical Bayesian OED pipeline integrates several key components [9]:

- Knowledge-Based Prior Construction: Prior knowledge, whether from scientific theory or empirical observation, is encoded into a prior probability distribution

π(θ)over the model parameters. This helps mitigate issues arising from data scarcity. - Model Fusion via Bayesian Inference: As new experimental data

Dis acquired, the prior is updated to a posterior distributionπ(θ|D)using Bayes' theorem:π(θ|D) ∝ L(D|θ) * π(θ), whereL(D|θ)is the likelihood function. This seamlessly integrates domain knowledge with new data. - Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): The posterior distribution inherently captures the remaining uncertainty in the model parameters (epistemic uncertainty) and, when combined with a measurement model, the uncertainty in predictions (aleatoric uncertainty).

Application Protocols in Materials Discovery

Two advanced Bayesian methodologies exemplify the application of these principles for targeted materials discovery.

Protocol 1: Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) for Targeted Subset Discovery

Many materials goals involve finding regions of a design space that meet complex, multi-property criteria, not just a single global optimum. The BAX framework addresses this by allowing users to define their goal via an algorithm, which is then automatically translated into an efficient data acquisition strategy [10].

Detailed Methodology:

Problem Formulation:

- Define the discrete design space

X(e.g., synthesis conditions, composition parameters). - Define the property space

Y(e.g., bandgap, tensile strength, catalytic activity). - Specify the experimental goal as an algorithmic procedure

Athat would return a target subsetT_*of the design space if the true functionf_*: X → Ywere known. For example,Acould be a filter that returns all points where propertyy1is above a thresholdaand propertyy2is below a thresholdb[10].

- Define the discrete design space

Model Initialization:

- Place a probabilistic model, typically a Gaussian Process (GP), as a prior over the unknown function

f_*. The GP is defined by a mean function and a kernel (covariance function) suitable for the data [10].

- Place a probabilistic model, typically a Gaussian Process (GP), as a prior over the unknown function

Sequential Data Acquisition via BAX Strategies:

- Starting with an initial small dataset, iteratively select the next experiment by evaluating one of the following acquisition functions:

- InfoBAX: Estimates the mutual information between the data and the algorithm's output, favoring points that most reduce the uncertainty about the target subset

T_*[10] [11]. - MeanBAX: Uses the posterior mean of the GP to execute the algorithm and selects points that the mean-predicted algorithm identifies as part of the target subset. This is more exploitative and effective in medium-data regimes [10].

- SwitchBAX: A parameter-free strategy that dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX based on their estimated performance, ensuring robustness across different dataset sizes [10].

- InfoBAX: Estimates the mutual information between the data and the algorithm's output, favoring points that most reduce the uncertainty about the target subset

- Perform the experiment at the selected design point

xand measure the corresponding propertiesy. - Update the GP posterior with the new data

(x, y).

- Starting with an initial small dataset, iteratively select the next experiment by evaluating one of the following acquisition functions:

Termination and Output:

- The process is repeated until an experimental budget is exhausted or the target subset is identified with sufficient confidence.

- The final output is the estimated target subset

Tderived from executing the user-defined algorithmAon the final GP posterior.

Application Example: This protocol has been demonstrated for discovering TiO₂ nanoparticle synthesis conditions that yield specific size ranges and for identifying regions in magnetic materials with desired property characteristics [10] [11].

Protocol 2: Physics-Informed Bayesian Neural Networks for Property Prediction

For predicting complex material properties like creep rupture life, integrating physical knowledge directly into the model can greatly enhance predictive accuracy and uncertainty quantification. Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) are well-suited for this task [12].

Detailed Methodology:

Network Specification:

Physics-Informed Integration:

- Feature Engineering: Incorporate physics-based features into the input layer. For creep life prediction, this could include terms derived from governing creep laws (e.g., Larson-Miller parameter) [12].

- Likelihood Definition: Define the likelihood

p(Y|X, w). - For regression, this is often a Gaussian distribution where the mean is the network output and the variance captures aleatoric noise [12].

Posterior Inference:

- Compute the true posterior

p(w|X,Y)is computationally intractable. Use approximate inference techniques:- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC): A gold-standard sampling method that provides accurate posterior estimates but is computationally expensive [12].

- Variational Inference (VI): A faster, more scalable method that approximates the true posterior by optimizing a simpler parameterized distribution

q_θ(w)to be close to the true posterior [12] [13].

- Compute the true posterior

Prediction and UQ:

- For a new input

x*, the predictive distribution for the propertyy*is obtained by marginalizing over the posterior:p(y*|x*, X, Y) = ∫ p(y*|x*, w) p(w|X, Y) dw. - This integral is approximated using samples from the posterior (e.g., from MCMC or VI). The mean of these samples gives the point prediction, and the standard deviation provides a quantitative measure of predictive uncertainty [12].

- For a new input

Application Example: This protocol has been validated on datasets of stainless steel, nickel-based superalloys, and titanium alloys, showing that MCMC-based BNNs provide reliable predictions and uncertainty estimates for creep rupture life, outperforming or matching conventional methods like Gaussian Process Regression [12].

Visual Guide to Bayesian Experimental Design

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, closed-loop workflow of a Bayesian optimal experimental design process, as implemented in protocols like BAX and physics-informed BNNs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues the essential computational and methodological "reagents" required to implement the Bayesian frameworks discussed.

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A probabilistic model used as a surrogate for the unknown material property function. Provides a posterior mean and variance for any design point. | Kernel choice (e.g., Matern) is critical. Scalability to large datasets can be a challenge [10] [3]. |

| Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) | A neural network with distributions over weights. Captures model uncertainty and is highly flexible for complex, high-dimensional mappings. | Inference is approximate (VI, MCMC). More complex to implement than GPs [12] [13]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A class of algorithms for sampling from complex posterior distributions. Considered a gold standard for Bayesian inference. | Computationally expensive, especially for large models like BNNs [12]. |

| Variational Inference (VI) | A faster alternative to MCMC that approximates the posterior by optimizing a simpler distribution. | More scalable but introduces approximation bias. Quality depends on the variational family [12] [13]. |

| Acquisition Function | A utility function that guides the selection of the next experiment by balancing exploration and exploitation. | Choice is goal-dependent (e.g., BAX for subsets, EI for optimization) [10] [3]. |

Quantitative Comparison of UQ Methods

The performance of different UQ methods can be evaluated using standardized metrics for predictive accuracy and uncertainty quality. The following table summarizes a comparative analysis, as demonstrated in studies on material property prediction.

| Method | Predictive Accuracy (R² / RMSE) | Uncertainty Quality (Coverage) | Computational Cost | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | High on small to medium datasets [12] | Good with appropriate kernels [12] | High for large N (O(N³)) |

Ideal for continuous design spaces and smaller datasets [12] [3]. |

| BNN (MCMC) | Competitive, often highest reliability [12] | High, reliable coverage intervals [12] | Very High | Recommended for complex property prediction where data is available (e.g., creep life) [12]. |

| BNN (Variational Inference) | Good, can be slightly inferior to MCMC [12] [13] | Can be over/under-confident [13] | Medium | A practical compromise for larger BNN models and active learning loops [12]. |

| Deep Ensembles | High | Good in practice, but not Bayesian [13] | Medium (multiple trainings) | A strong, easily implemented baseline for predictive UQ [13]. |

Objective-Based Uncertainty Quantification and the Fisher Information Matrix

Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) is a critical component in the optimization of experiments for materials discovery and drug development. Traditional UQ methods often focus on quantifying uncertainty in model parameters without a direct link to the ultimate operational goal. In contrast, Objective-Based Uncertainty Quantification provides a framework for quantifying uncertainty based on its expected impact on a specific operational cost or objective function [9] [14]. This paradigm shift allows researchers to prioritize uncertainty reduction efforts where they matter most for decision-making.

The core mathematical foundation of this approach involves designing optimal operators that minimize an expected cost function considering all possible models within an uncertainty class. Formally, this is expressed as:

ψopt = arg minψ∈Ψ Eθ[C(ψ, θ)]

where Ψ represents the operator class, C(ψ, θ) denotes the cost of applying operator ψ under model parameters θ, and the expectation is taken over the uncertainty class of models parameterized by θ [9]. This formulation naturally leads to the concept of the Mean Objective Cost of Uncertainty (MOCU), which quantifies the expected increase in operational cost induced by system uncertainties [14]. MOCU provides a practical way to quantify the effect of various types of system uncertainties on the operation of interest and serves as a mathematical basis for integrating prior knowledge, designing robust operators, and planning optimal experiments.

The Fisher Information Matrix in Optimal Experimental Design

Theoretical Foundations

The Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) is a fundamental mathematical tool in statistical inference that quantifies the amount of information that an observable random variable carries about an unknown parameter. In the context of optimal experimental design, FIM serves as a powerful approach for predicting uncertainty in parameter estimates and guiding experimental resource allocation [15].

For a statistical model with likelihood function p(y|θ), where y represents observed data and θ represents model parameters, the FIM I(θ) is defined as:

I(θ) = E[ (∂ log p(y|θ)/∂θ) · (∂ log p(y|θ)/∂θ)T ]

According to the Cramér-Rao lower bound, the inverse of the FIM provides a lower bound on the variance of any unbiased estimator of θ, establishing a fundamental connection between information content and estimation precision [15]. This relationship makes FIM invaluable for experimental design, as it allows researchers to predict and minimize expected parameter uncertainties before conducting experiments.

Computational Approaches

In practical applications for complex models such as Non-Linear Mixed Effects Models (NLMEM) commonly used in pharmacometrics, the FIM is typically computed through linearization techniques [15]. Recent methodological advances have extended FIM calculation by computing its expectation over the joint distribution of covariates, incorporating three primary methods:

- Sample-Based Estimation: Using a provided sample of covariate vectors from existing data

- Simulation-Based Estimation: Simulating covariate vectors based on provided independent distributions

- Copula-Based Estimation: Modeling dependencies among covariates using estimated copulas [15]

These approaches enable more accurate prediction of uncertainty on covariate effects and statistical power for detecting clinically relevant relationships, particularly important in pharmacological studies where covariate effects on inter-individual variability must be identified and quantified.

Table 1: Comparison of FIM Computation Methods

| Method | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample-Based | Existing covariate sample | No distributional assumptions | Limited to available covariates |

| Simulation-Based | Independent covariate distributions | Flexible for hypothetical scenarios | Misses covariate dependencies |

| Copula-Based | Data for copula estimation | Captures covariate correlations | Computationally intensive |

Integrated Framework for Materials Discovery

Synergistic Integration of MOCU and FIM

The integration of objective-based UQ and FIM creates a powerful framework for optimal experimental design in materials discovery. While MOCU provides a goal-oriented measure of uncertainty impact, FIM offers a mechanism to quantify how different experimental designs reduce parameter uncertainties that contribute to this impact [9] [15]. This synergy enables researchers to design experiments that efficiently reduce the uncertainties that matter most for specific objectives.

In the context of materials discovery, this integrated approach is particularly valuable for navigating high-dimensional design spaces, where the number of possible material combinations is vast and traditional trial-and-error approaches are impractical [16]. By combining MOCU-based experimental design with FIM-powered uncertainty prediction, researchers can prioritize experiments that maximize information gain for targeted material properties while minimizing experimental costs.

Bayesian Optimization and Active Learning

The MOCU-FIM framework naturally integrates with Bayesian optimization and active learning approaches that have shown significant promise in materials science [16] [17]. These iterative approaches rely on surrogate models together with acquisition functions that prioritize decision-making on unexplored data based on uncertainties [16].

As illustrated in the CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform developed at MIT, this approach can guide the exploration of complex material spaces by incorporating diverse information sources including literature knowledge, experimental results, and human feedback [17]. The system uses Bayesian optimization in a knowledge-embedded reduced space to design new experiments, then feeds newly acquired multimodal data back into models to augment the knowledge base and refine the search space [17].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol: FIM-Based Experimental Design for Pharmacometric Studies

Purpose: To optimize design of Pharmacokinetic (PK) and Pharmacodynamic (PD) studies using FIM to predict uncertainty in covariate effects and power to detect their relevance in Non-Linear Mixed Effect Models.

Materials and Reagents:

- PFIM 6.1 R package or equivalent software for FIM computation

- Population PK/PD model structure with defined parameters and covariates

- Existing covariate data or distributions for simulation

- Clinical trial scenario specifications (dosing regimens, sampling times)

Procedure:

- Model Specification: Define the structural model, parameter distributions, and residual error model. Identify all covariate relationships to be tested.

- Design Space Definition: Specify candidate sampling times, dose levels, and patient population characteristics.

- FIM Computation: Calculate the Fisher Information Matrix using linearization, considering the joint distribution of covariates using one of the three methods (sample-based, simulation-based, or copula-based).

- Uncertainty Prediction: Derive confidence intervals for covariate effect parameters and predicted power of statistical tests to detect significant effects.

- Design Optimization: Evaluate different design scenarios (sample sizes, sampling schedules) to achieve desired precision and power.

- Validation: Conduct simulation studies to verify operating characteristics under the optimized design [15].

Applications: This protocol was successfully applied to a population PK model of the drug cabozantinib including 27 covariate relationships, demonstrating accurate prediction of uncertainty despite numerous relationships and limited representation of certain covariates [15].

Protocol: MOCU-Driven Materials Discovery with Autonomous Experimentation

Purpose: To implement an objective-based active learning loop for accelerated discovery of materials with targeted properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Robotic materials synthesis system (e.g., liquid-handling robot, carbothermal shock system)

- Automated characterization equipment (e.g., electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction)

- High-throughput testing apparatus (e.g., automated electrochemical workstation)

- Computational resources for large multimodal models

- Target material system with defined design variables (elements, processing parameters)

Procedure:

- Objective Definition: Specify target material properties and operational cost function.

- Knowledge Base Construction: Extract relevant information from scientific literature and databases to create initial knowledge embeddings.

- Search Space Reduction: Perform principal component analysis in knowledge embedding space to identify reduced search space capturing most performance variability.

- Bayesian Optimization: Use MOCU-aware acquisition functions to select promising material compositions for experimentation.

- Autonomous Synthesis and Testing: Execute robotic synthesis, characterization, and performance testing of selected candidates.

- Multimodal Data Integration: Incorporate experimental results, literature knowledge, and human feedback to update models.

- Iterative Refinement: Repeat steps 3-6 until performance targets are met or resources exhausted [17].

Applications: This approach was used to develop an electrode material for direct formate fuel cells, exploring over 900 chemistries and conducting 3,500 electrochemical tests to discover an eight-element catalyst with 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar over pure palladium [17].

Workflow Visualization

Experimental Optimization Workflow Integrating MOCU and FIM

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Objective-Based UQ and FIM Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFIM 6.1 | R Package | FIM computation & experimental design | Pharmacometric studies [15] |

| CRESt Platform | AI System | Multimodal data integration & experimental optimization | Materials discovery [17] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Algorithm | Sequential experimental design | Active learning for materials [16] [17] |

| Universal Differential Equations | Modeling Framework | Mechanistic & machine learning model integration | Scientific machine learning [18] |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo | Sampling Method | Bayesian parameter estimation | Uncertainty quantification [18] |

| Deep Ensembles | UQ Method | Epistemic uncertainty estimation | Neural network uncertainty [18] |

Case Studies and Performance Metrics

Pharmacometrics Application

In the application of FIM to a population PK model of cabozantinib with 27 covariate relationships, the method accurately predicted uncertainty on covariate effects and power of tests despite challenges from numerous relationships and limited representation of certain covariates [15]. The approach enabled rapid computation of the number of subjects needed to achieve desired statistical power, demonstrating practical utility for clinical trial design.

Key performance metrics included:

- Accurate prediction of uncertainty on covariate parameters across varying sample sizes

- Reliable power calculations for detecting statistically significant covariate effects

- Efficient determination of subject numbers required for target confidence levels

Materials Discovery Application

The CRESt platform implementation demonstrated substantial acceleration in materials discovery, achieving:

Table 3: Performance Metrics for CRESt Materials Discovery Platform

| Metric | Traditional Approach | MOCU-FIM Approach | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistries Explored | ~100-200 in 3 months | 900+ in 3 months | 4.5-9x |

| Tests Conducted | Limited by manual effort | 3,500 electrochemical tests | Significant acceleration |

| Performance Gain | Incremental improvements | 9.3x power density per dollar | Breakthrough optimization |

| Precious Metal Use | Standard formulations | 75% reduction | Cost efficiency |

The system discovered a catalyst material with eight elements that achieved record power density in a direct formate fuel cell while containing just one-fourth of the precious metals of previous devices [17].

The integration of objective-based uncertainty quantification with Fisher Information Matrix methods provides a powerful framework for optimal experimental design in materials discovery and drug development. By focusing uncertainty reduction efforts where they have the greatest impact on operational objectives, this approach enables more efficient resource allocation and accelerated discovery of solutions to complex scientific challenges.

The protocols and applications detailed in these notes demonstrate the practical implementation of these concepts across different domains, from pharmacometrics to materials science. As autonomous experimentation platforms continue to evolve, the MOCU-FIM framework offers a principled approach for guiding experimental decisions while explicitly accounting for uncertainties and their impact on target objectives.

The process of materials discovery is often limited by the speed at which costly and time-consuming experiments can be performed [10]. Intelligent sequential experimental design has emerged as a promising approach to navigate large design spaces more efficiently. Within this framework, Bayesian optimization (BO) serves as a powerful strategy for iteratively selecting experiments that maximize the probability of discovering materials with desired properties [10]. A critical component of any Bayesian method is the prior distribution, which encapsulates beliefs about the system before collecting new data. This application note details methodologies for integrating scientific insight into Bayesian priors to accelerate materials discovery within the broader context of optimal experimental design.

Theoretical Framework

Bayesian Optimization in Materials Discovery

Bayesian optimization provides a principled framework for navigating complex experimental landscapes. The core components include:

- Probabilistic Surrogate Model: Typically a Gaussian process (GP) that models the unknown function mapping design parameters to material properties, providing both predictions and uncertainty estimates [10].

- Acquisition Function: A criterion that uses the surrogate model's predictions to select the next experiment by balancing exploration (sampling high-uncertainty regions) and exploitation (sampling promising regions) [10].

Traditional acquisition functions include Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), Expected Improvement (EI), and others tailored for single or multi-objective optimization [10].

The Critical Role of Priors

In Bayesian statistics, the prior distribution formalizes existing knowledge about a system. An informative prior can significantly reduce the number of experiments required to reach a target by starting the search process from a more plausible region of the parameter space. Prior knowledge in materials science may come from:

- Physicochemical models

- Previous experimental campaigns on similar material systems

- High-throughput computational simulations

- Scientific literature and domain expertise

Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Encoding Physicochemical Models as Priors

Objective: Incorporate simplified physical models into Gaussian process priors.

Procedure:

- Model Identification: Select a relevant physical model (e.g., Arrhenius equation for reaction rates, phase field models for microstructure evolution).

- Parameter Estimation: Use literature values or coarse-grained simulations to estimate model parameters.

- Mean Function Specification: Implement the physical model as the mean function of the Gaussian process.

- Kernel Selection: Choose a kernel (e.g., Matérn, Radial Basis Function) that captures expected deviations from the physical model.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Set initial length scales and variance parameters based on confidence in the physical model.

Protocol 2: Transfer Learning from Related Material Systems

Objective: Utilize data from previously studied material systems to inform priors for new systems.

Procedure:

- Source Data Collection: Gather experimental data and corresponding models from a well-characterized material system.

- Posterior Extraction: Extract the posterior distribution of parameters from the source system's model.

- Feature Alignment: Establish correspondence between parameters in the source and target systems.

- Prior Adaptation: Scale and adjust the source posterior to account for differences between material systems.

- Uncertainty Inflation: Increase uncertainty estimates to reflect transfer process limitations.

Objective: Systematically capture domain expertise to construct informative priors.

Procedure:

- Parameter Identification: Identify key parameters requiring prior specification.

- Expert Consultation: Engage multiple domain experts to obtain estimates for parameter values and uncertainties.

- Prior Distribution Fitting: Fit appropriate probability distributions to the aggregated expert estimates.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test optimization robustness to variations in prior specifications.

Advanced Bayesian Algorithm Execution

Recent advances in Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) provide frameworks for targeting specific experimental goals beyond simple optimization [10]. These approaches capture experimental goals through user-defined filtering algorithms that automatically convert into intelligent data collection strategies:

- InfoBAX: Selects experiments that provide the most information about the target subset [10].

- MeanBAX: Uses model posteriors to explore the design space [10].

- SwitchBAX: Dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX for robust performance across different data regimes [10].

These methods are particularly valuable for materials design problems involving multiple property constraints or seeking specific regions of the design space rather than single optimal points [10].

Case Study: Nanoparticle Synthesis Optimization

Experimental Setup

Objective: Identify synthesis conditions (precursor concentration, temperature, reaction time) that produce TiO₂ nanoparticles with target size (5-7 nm) and bandgap (3.2-3.3 eV).

Prior Integration:

- Incorporated prior knowledge from literature on similar metal oxide systems

- Used physicochemical model for nanoparticle growth as GP mean function

- Set initial length scales based on known sensitivity of size to temperature variations

Results and Performance

The following table summarizes the performance comparison between Bayesian optimization with informative versus uninformative (default) priors:

Table 1: Performance comparison of Bayesian optimization with different prior specifications for TiO₂ nanoparticle synthesis optimization

| Metric | Uninformative Prior | Informative Prior | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiments to target | 38 | 19 | 50% reduction |

| Final size (nm) | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 19% closer to target |

| Final bandgap (eV) | 3.24 ± 0.04 | 3.26 ± 0.03 | 12% closer to target |

| Model convergence (iterations) | 25 | 12 | 52% faster |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and resources for implementing Bayesian optimization with informative priors in materials discovery

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Framework (e.g., GPyTorch, scikit-learn) | Provides surrogate modeling capabilities with customizable mean functions and kernels | Select kernels that match expected material property smoothness; implement physical models as mean functions |

| Bayesian Optimization Libraries (e.g., BoTorch, Ax) | Offers implementations of acquisition functions and optimization algorithms | Choose acquisition functions aligned with experimental goals; customize for multi-property optimization |

| Domain-Specific Simulators (e.g., DFT calculators, phase field models) | Generates synthetic data for prior construction | Use coarse-grained simulations for computational efficiency; calibrate with limited experimental data |

| Materials Database APIs (e.g., Materials Project, Citrination) | Provides access to existing experimental data for prior formulation | Curate relevant subsets based on material similarity; account for systematic measurement differences |

Implementation Guidelines

Prior Specification Best Practices

- Start Weakly Informative: When domain knowledge is limited, use weakly informative priors that regularize without strongly biasing results.

- Perform Sensitivity Analysis: Test optimization robustness by running with multiple prior specifications.

- Balance Flexibility and Guidance: Ensure priors are flexible enough to discover unexpected phenomena while providing useful guidance.

- Document Prior Justifications: Maintain clear records of prior choices and their scientific rationale.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Overly Restrictive Priors: If optimization consistently fails to find promising regions, consider broadening prior distributions.

- Incorrect Model Assumptions: If experimental data consistently contradicts prior predictions, re-evaluate the physical models embedded in priors.

- Transfer Learning Mismatch: When transferring knowledge between material systems, validate prior predictions with a small number of initial experiments.

Integrating scientific insight into Bayesian priors represents a powerful methodology for accelerating materials discovery. The protocols outlined in this application note provide practical guidance for implementing these approaches across various material systems and experimental goals. By moving beyond uninformative priors and systematically incorporating domain knowledge, researchers can significantly reduce experimental burdens while maintaining the flexibility to discover novel materials with targeted properties. As Bayesian methods continue to evolve, particularly with frameworks like BAX that enable more complex experimental goals, the strategic use of prior knowledge will remain essential for navigating the vast design spaces of materials science.

In the field of materials discovery, the efficiency of experimental campaigns is paramount. Traditional approaches often rely on one-factor-at-a-time experimentation or factorial designs, which can be prohibitively slow and resource-intensive when navigating complex, high-dimensional design spaces. The emergence of intelligent, sequential experimental design strategies, particularly Bayesian optimization (BO), has provided a powerful framework for accelerating this process [10]. These methods use probabilistic models to guide experiments toward the most informative points in the design space. However, the ultimate effectiveness of these strategies is limited not by the model's accuracy, but by how well the guiding objective—formalized as an acquisition function—aligns with the researcher's true, and often complex, experimental goal [10]. This application note charts the evolution of these experimental goals, from foundational single-objective optimization to the more flexible and powerful paradigm of target subset estimation, which uses Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) to directly discover materials that meet multi-faceted, real-world criteria.

Theoretical Foundations: A Hierarchy of Experimental Goals

Intelligent data acquisition requires a precise definition of the experimental goal. These goals can be organized hierarchically, from the simple to the complex, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: A Hierarchy of Experimental Goals in Materials Discovery

| Experimental Goal | Definition | Typical Acquisition Function | Example Materials Science Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Objective Optimization | Find the design point that maximizes or minimizes a single property of interest. | Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [10]. | Find the electrolyte formulation with the largest electrochemical window of stability [10]. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | Find the set of design points representing the optimal trade-off between two or more competing properties (the Pareto front). | Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) [19] [20]. | Maximize the similarity of a 3D-printed object to its target while maximizing layer homogeneity [19]. |

| Full-Function Estimation (Mapping) | Learn the relationship between the design space and property space across the entire domain. | Uncertainty Sampling (US) [10]. | Map a phase diagram to understand system behavior comprehensively [10]. |

| Target Subset Estimation | Identify all design points where measured properties meet specific, user-defined criteria. | InfoBAX, MeanBAX, SwitchBAX [10]. | Find all synthesis conditions that produce nanoparticles within a specific range of monodisperse sizes [10]. |

The transition from single- or multi-objective optimization to target subset estimation represents a significant shift in experimental design. While optimization seeks a single "best" point or a Pareto-optimal frontier, subset estimation aims to identify a broader set of candidates that fulfill precise specifications [10]. This is particularly valuable for mitigating risks like long-term material degradation, as it provides a pool of viable alternative candidates [10].

Protocol: Implementing Target Subset Estimation with the BAX Framework

The following protocol details the steps for applying the BAX framework to a materials discovery problem, enabling the direct discovery of a target subset of the design space.

Principle

The core principle of Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) is to bypass the need for designing a custom acquisition function for every new experimental goal [10]. Instead, the user defines their goal via a simple algorithmic procedure that would return the correct subset of the design space if the underlying property function were known. The BAX framework then automatically converts this algorithm into an acquisition strategy that sequentially selects experiments to execute this algorithm efficiently on the unknown, true function.

Equipment and Data Requirements

- A Discrete Design Space (X): A finite set of N possible synthesis or measurement conditions (e.g., combinations of temperature, pressure, and precursor concentrations) [10].

- Measurement Apparatus: Equipment capable of conducting experiments at specified design points

xand measuring the corresponding m material propertiesy(e.g., electrochemical workstation, electron microscope) [10]. - Computational Resources: Standard computer for running probabilistic models (e.g., Gaussian Processes) and the BAX algorithm.

Reagent Solutions and Research Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Components for an Autonomous Experimentation System

| Item | Function/Description | Example in AM-ARES [19] |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Handling Robot | Automates the precise dispensing of precursor solutions or reagents. | Custom-built syringe extruder for material deposition. |

| Synthesis Reactor | A controlled environment for material synthesis (e.g., heating, mixing). | Carbothermal shock system for rapid synthesis [17]. |

| Characterization Tools | Instruments to measure material properties of interest. | Integrated electrochemical workstation; automated electron microscope [17] [19]. |

| Machine Vision System | Cameras and software for in-situ monitoring and analysis of experiments. | Dual-camera system to capture images of printed specimens for analysis [19]. |

| AI/ML Planner Software | The computational core that runs the BAX or BO algorithm to design new experiments. | Multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MOBO) planner [19]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Initialize: Define the discrete design space

Xand the experimental goal by writing an algorithmAthat takes a functionf(representing the material properties) as input and returns the target subsetT = A(f). For example, an algorithm to find all points where conductivity is greater than a thresholdkwould beA(f) = {x | f(x) > k}[10]. - Modeling: Place a probabilistic model, such as a Gaussian Process (GP), over the unknown function

f*using any initial data. If no data exists, start with a prior distribution [10]. - Acquisition: For a new experiment, use a BAX strategy (e.g., InfoBAX, MeanBAX, or SwitchBAX) to select the next design point

xto evaluate.- InfoBAX selects points that are expected to provide the most information about the target subset

T[10]. - MeanBAX uses the model's posterior mean to estimate

Tand explores points within it [10]. - SwitchBAX dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX for robust performance across different data regimes [10].

- InfoBAX selects points that are expected to provide the most information about the target subset

- Experiment: Conduct the experiment at the selected point

xand measure the propertiesy[10]. - Analysis: Update the probabilistic model (e.g., the GP posterior) with the new data point

(x, y)[10]. - Iterate: Repeat steps 3-5 until the experimental budget is exhausted or the target subset

Tis identified with sufficient confidence. - Conclude: Output the estimated target subset based on the final model [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this closed-loop, autonomous experimentation process.

Diagram 1: Autonomous Experimentation Loop for Target Subset Estimation.

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Case Study: Discovering a Multi-Element Fuel Cell Catalyst

A recent MIT study developed the CRESt platform, which integrates multimodal information (literature, chemical compositions, images) with robotic experimentation. Researchers used this system to find a catalyst for a direct formate fuel cell. The goal was not just to maximize power density, but to find a formulation that achieved high performance while reducing precious metal content—a quintessential target subset estimation problem. CRESt explored over 900 chemistries, ultimately discovering an eight-element catalyst that delivered a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar and a record power density with only one-fourth the precious metals of previous devices [17].

Advanced Framework: Cost-Aware Batch BO with Deep Gaussian Processes

For highly complex problems, standard GPs can be limiting. A recent advanced framework uses Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs) as surrogate models. DGPs stack multiple GP layers, enabling them to capture complex, hierarchical relationships in materials data more effectively than single-layer GPs [20]. This framework is integrated with a cost-aware, batch acquisition function (q-EHVI), which can propose small batches of experiments to run in parallel, while accounting for the different costs of various characterization techniques. This allows the system to use cheap, low-fidelity queries for broad exploration and reserve expensive, high-fidelity tests for the most promising candidates, dramatically improving overall efficiency in campaigns like the design of refractory high-entropy alloys [20].

The move from single-objective optimization to target subset estimation marks a critical advancement in optimal experimental design for materials research. By leveraging frameworks like BAX, scientists can now directly encode complex, real-world requirements into an autonomous discovery workflow. This approach, especially when enhanced with powerful models like Deep GPs and cost-aware batch strategies, provides a practical and efficient pathway to solving the multifaceted challenges of modern materials development.

Frameworks and Algorithms for Targeted Materials Discovery

Bayesian Optimization (BO) has emerged as a powerful machine learning framework for the efficient optimization of expensive black-box functions, a challenge frequently encountered in materials discovery and drug development research. When experimental evaluations—such as synthesizing a new material or testing a biological formulation—are costly or time-consuming, BO provides a sample-efficient strategy for navigating complex design spaces. The core of the BO paradigm consists of two components: a probabilistic surrogate model that approximates the unknown objective function, and an acquisition function that guides the selection of future experiments by balancing the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of known promising areas [21]. This adaptive, sequential design of experiments is particularly suited for optimizing critical quality attributes in materials science and pharmaceutical development, where it can significantly reduce the experimental burden compared to traditional methods like one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) or Design of Experiments (DoE) [22] [23].

Within a broader thesis on optimal experimental design, BO represents a shift from static, pre-planned experimental arrays towards dynamic, data-adaptive protocols. This review focuses on the pivotal role of acquisition functions—specifically Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), and Probability of Improvement (PI). We detail their operational mechanisms, comparative performance, and provide structured protocols for their implementation in real-world research scenarios, with an emphasis on applications in materials and vaccine formulation development.

Theoretical Foundations of Acquisition Functions

Acquisition functions are the decision-making engine of the BO loop. They use the posterior predictions (mean and uncertainty) of the surrogate model, typically a Gaussian Process (GP), to assign a utility score to every candidate point in the design space. The next experiment is conducted at the point that maximizes this utility. Below is a formal description of the three core acquisition functions.

Let the unknown function be ( f(\mathbf{x}) ), the current best observation be ( f(\mathbf{x}^+) ), and the posterior distribution of the GP at a point ( \mathbf{x} ) be ( \mathcal{N}(\mu(\mathbf{x}), \sigma^2(\mathbf{x})) ).

Probability of Improvement (PI): PI seeks to maximize the probability that a new point ( \mathbf{x} ) will yield an improvement over the current best ( f(\mathbf{x}^+) ). A small trade-off parameter ( \xi ) is often added to encourage exploration. [ \alpha_{\text{PI}}(\mathbf{x}) = P(f(\mathbf{x}) > f(\mathbf{x}^+) + \xi) = \Phi\left( \frac{\mu(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+) - \xi}{\sigma(\mathbf{x})} \right) ] where ( \Phi ) is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. PI is one of the earliest acquisition functions but can be overly greedy, often getting trapped in local optima with small, incremental improvements [10].

Expected Improvement (EI): EI improves upon PI by considering not just the probability of improvement, but also the magnitude of the expected improvement. It is defined as: [ \alpha{\text{EI}}(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbb{E}[\max(f(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+), 0)] ] This has a closed-form solution under the GP surrogate: [ \alpha{\text{EI}}(\mathbf{x}) = (\mu(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+) - \xi)\Phi(Z) + \sigma(\mathbf{x})\phi(Z), \quad \text{if } \sigma(\mathbf{x}) > 0 ] where ( Z = \frac{\mu(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+) - \xi}{\sigma(\mathbf{x})} ), and ( \phi ) is the probability density function of the standard normal. EI is one of the most widely used acquisition functions due to its strong theoretical foundation and robust performance [21] [24].

Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): UCB uses an optimism-in-the-face-of-uncertainty strategy. It directly combines the posterior mean (exploitation) and standard deviation (exploration) into a simple, tunable function. [ \alpha_{\text{UCB}}(\mathbf{x}) = \mu(\mathbf{x}) + \beta \sigma(\mathbf{x}) ] The parameter ( \beta \geq 0 ) controls the trade-off between exploration and exploitation. UCB is intuitive and has known regret bounds, making it popular in both theory and practice [25] [24]. Its simplicity also makes it well-suited for parallel batch optimization, leading to variants like qUCB [24].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process of an acquisition function within the BO loop.

Comparative Analysis and Application Selection

The choice of acquisition function is not universal; it depends on the problem's characteristics, such as the landscape of the objective function, the presence of noise, and the experimental mode (serial or batch). The table below synthesizes a quantitative comparison based on benchmark studies to guide researchers in their selection.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Acquisition Functions on Benchmark Problems

| Acquisition Function | Ackley (6D, Noiseless) | Hartmann (6D, Noiseless) | Hartmann (6D, Noisy) | Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells (4D, Noisy) | Key Characteristics & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCB / qUCB | Good performance, reliable convergence [24] | Good performance, reliable convergence [24] | Good noise immunity, reasonable performance [24] | Recommended as default for reliable convergence [24] | Intuitive; tunable via β. Recommended as a default choice when landscape is unknown [24]. |

| EI / qEI / qlogEI | Performance inferior to UCB [24] | Performance inferior to UCB [24] | qlogNEI (noise-aware) improves performance [24] | Not best performer in empirical tests [24] | Strong theoretical foundation; can be numerically unstable. Use noise-aware variants (e.g., NEI) for noisy systems. |

| PI | Prone to getting stuck in local optima [10] | Prone to getting stuck in local optima [10] | Not recommended for noisy problems [10] | Not recommended for empirical problems [10] | Greedy; tends to exploit known good areas. Not recommended for global optimization of unknown spaces. |

| TSEMO (Multi-Objective) | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Shows strong gains in hypervolume [21] | Used for multi-objective optimization (MOBO). Effective but can have high computational cost [21]. |

Beyond the standard functions, recent advances have led to frameworks that automate acquisition for complex goals. The Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) framework allows users to define goals via filtering algorithms, which are automatically translated into custom acquisition strategies like InfoBAX and MeanBAX. This is particularly useful for finding target subsets of a design space that meet specific property criteria, a common task in materials discovery [10]. Furthermore, for problems involving both qualitative (e.g., choice of catalyst or solvent) and quantitative variables (e.g., temperature and concentration), the Latent-Variable GP (LVGP) approach maps qualitative factors to underlying numerical latent variables. Integrating LVGP with BO (LVGP-BO) has shown superior performance for such mixed-variable problems, which are ubiquitous in materials design and chemical synthesis [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides step-by-step protocols for implementing a BO campaign, from initial setup to execution, tailored for real-world laboratory research.

Protocol 1: Setting Up a Bayesian Optimization Campaign for Materials Synthesis

This protocol outlines the procedure for using BO to optimize a materials synthesis process, such as maximizing the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of a perovskite solar cell or the yield of a nanoparticle synthesis [24].

- Objective: To find the set of synthesis parameters ( \mathbf{x}^* ) that maximizes a desired material property ( y ).

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Gaussian Process Model: A probabilistic surrogate, typically using an ARD Matern 5/2 kernel for its flexibility. Functions as the predictive engine.

- Acquisition Function (e.g., qUCB): The decision-making algorithm that proposes the next experiments. qUCB is recommended for batch mode.

- Optimization Library (e.g., BoTorch, Emukit): Software tools for implementing the BO loop and optimizing the acquisition function.

- Initial Dataset (Latin Hypercube Sample): A space-filling design to build the initial surrogate model with minimal bias.

Procedure:

- Define Design Space: Identify all continuous (e.g., temperature, concentration) and categorical (e.g., solvent type, catalyst class) input variables ( \mathbf{x} ) and their valid ranges/levels.

- Generate Initial Dataset: Perform ( n ) initial experiments (e.g., ( n=24 ) for a 6D space) using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to ensure the design space is well-covered [24].

- Build Initial GP Model: Train a GP model on the initial dataset ( {\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{y}} ). Normalize input parameters to [0, 1] and standardize the objective values for numerical stability.

- Iterative BO Loop: For a predetermined number of iterations or until convergence: a. Optimize Acquisition Function: Find the batch of ( q ) points ( {\mathbf{x}1, ..., \mathbf{x}q} ) that jointly maximizes the chosen acquisition function (e.g., qUCB). For serial optimization, select the single point with the highest value. b. Execute Experiments: Conduct the synthesis and characterization experiments at the proposed points to obtain new objective values ( {y1, ..., yq} ). c. Update Model: Augment the dataset with the new ( {\mathbf{x}, y} ) pairs and retrain the GP model.

- Termination and Analysis: Upon completion, analyze the final model to identify the predicted optimum ( \mathbf{x}^* ). Validate this point with confirmatory experiments.

Protocol 2: Application to Vaccine Formulation Development

This protocol adapts BO for the development of biopharmaceutical formulations, such as optimizing a vaccine formulation for maximum stability, as measured by infectious titer loss or glass transition temperature (( T_g' )) [22].

- Objective: To identify the excipient composition that minimizes titer loss of a live-attenuated virus after one week at 37°C [22].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Vaccine Candidate: The live-attenuated virus or antigen to be stabilized.

- Excipients Library: A panel of potential stabilizers (e.g., sugars, polyols, amino acids, polymers, surfactants, buffers).

- Stability-Indicating Assay (e.g., Plaque Assay): The high-cost experimental method used to measure the critical quality attribute (CQA), in this case, infectious titer.

- BO Software with Mixed-Variable Support: A platform capable of handling categorical variables (excipient identities) and continuous variables (excipient concentrations).

Procedure:

- Define Formulation Space: Specify the list of categorical factors (e.g., type of sugar, choice of buffer) and continuous factors (e.g., concentration of each excipient, pH).

- Conform to Constraints: Incorporate any necessary constraints, such as the total solid content in a lyophilized formulation or mutually exclusive excipients.

- Initial High-Throughput Screening: Perform a limited set of experiments based on historical knowledge or a sparse DoE to generate an initial dataset.

- Model and Optimize: a. Use an LVGP model if categorical variables are present to map them to latent numerical spaces [26]. b. Employ a noise-robust acquisition function like Expected Improvement with a noise model. c. Iterate the BO loop: the model suggests a new formulation, which is prepared and tested via the plaque assay, and the results are used to update the model.

- Model Validation: Validate the final model's predictions using a separate test dataset. Use model interpretation tools (e.g., SHAP analysis) to understand the influence of key excipients [22].

The following workflow diagram integrates these protocols into a unified view of the BO process for experimental research.

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

As BO is deployed in more complex research environments, several advanced considerations come to the fore. A critical challenge is high-dimensional optimization (e.g., >5 parameters). In 6D problems, the performance of acquisition functions can vary significantly with the landscape. For "needle-in-a-haystack" problems like the Ackley function, noise can severely degrade optimization, while for functions with "false maxima" like Hartmann, noise increases the probability of converging to a sub-optimal local maximum [25]. This underscores the need for prior knowledge of the domain structure and noise level when designing a BO campaign.

Another frontier is the integration of BO with other AI paradigms. The Reasoning BO framework incorporates large language models (LLMs) to generate and evolve scientific hypotheses, using domain knowledge to guide the optimization. This enhances interpretability and helps avoid local optima, as demonstrated in chemical reaction yield optimization where it significantly outperformed traditional BO [27]. For real-world research and development, these hybrid approaches, combined with robust handling of mixed variables and noise, are setting a new standard for the intelligent and efficient discovery of new materials and therapeutics.

Traditional Bayesian optimization (BO) has revolutionized materials discovery by efficiently finding conditions that maximize or minimize a single property. However, materials design often involves more complex, specialized goals, such as finding all synthesis conditions that yield nanoparticles within a specific range of sizes and shapes, or identifying a diverse set of compounds that meet multiple property criteria simultaneously [10]. These tasks require finding a target subset of the design space, not just a single optimum. Bayesian Algorithm Execution (BAX) is a framework that generalizes BO to address these complex objectives [28].

BAX allows researchers to specify their experimental goal through a straightforward filtering algorithm. This algorithm describes the subset of the design space that would be returned if the true, underlying function mapping design parameters to material properties were known. The BAX framework then automatically converts this algorithmic goal into an intelligent, sequential data acquisition strategy, bypassing the need for experts to design complex, task-specific acquisition functions from scratch [10] [29]. This is particularly valuable in materials science and drug development, where experiments are often costly and time-consuming, and the need for precise control over multiple properties is paramount [30].

Core BAX Algorithms and Their Mechanisms

The BAX framework provides several acquisition strategies, with InfoBAX, MeanBAX, and SwitchBAX being the most prominent for materials science applications. These strategies are tailored for discrete search spaces and can handle multi-property measurements [10] [31].

InfoBAX: Information-Based Bayesian Algorithm Execution

InfoBAX is an information-based strategy that sequentially chooses experiment locations to maximize the information gain about the output of the target algorithm.

- Principle: It selects queries that maximize the mutual information between the collected data and the algorithm's output [28]. In essence, it seeks the experiments that are most likely to reduce uncertainty about the final target subset.

- Process: The method works by first running the user-defined algorithm on multiple samples drawn from a posterior distribution of the black-box function. These "execution path" samples represent plausible outcomes of the algorithm. InfoBAX then estimates which new data point would provide the most information about which execution path is correct [28].

- Typical Use Case: InfoBAX has been shown to exhibit strong performance in the medium-data regime, where a moderate amount of data has already been collected [10].

MeanBAX: Posterior Mean-Based Execution

MeanBAX offers an alternative approach that relies on the posterior mean of the probabilistic model.

- Principle: This strategy executes the target algorithm not on posterior function samples, but directly on the current posterior mean estimate of the black-box function [10]. It then queries points that are accessed by this algorithm execution.

- Process: As the model is updated with new data, the posterior mean becomes a more accurate surrogate for the true function. Running the algorithm on this mean provides an evolving estimate of the target subset, and measurements are focused on the points critical to this estimate.

- Typical Use Case: Empirical results indicate that MeanBAX demonstrates complementary performance to InfoBAX, often excelling in the small-data regime at the start of an experimental campaign [10].

SwitchBAX: A Dynamic Hybrid Strategy

SwitchBAX is a parameter-free, meta-strategy designed to dynamically combine the strengths of InfoBAX and MeanBAX.

- Principle: It automatically and dynamically switches between the InfoBAX and MeanBAX acquisition functions based on their expected performance during the experimental sequence [11] [10].

- Process: The switching mechanism monitors which strategy is likely to be more informative at the current stage of experimentation. This allows it to leverage the rapid early progress often afforded by MeanBAX and the high-information efficiency of InfoBAX as more data accumulates.

- Advantage: By not being tied to a single strategy, SwitchBAX provides robust performance across the full range of dataset sizes, from initial exploration to later stages of refinement [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Core BAX Acquisition Strategies

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| InfoBAX | Maximizes mutual information with algorithm output [28] | High information efficiency | Medium-data regimes |

| MeanBAX | Executes algorithm on the model's posterior mean [10] | Robust performance with little data | Small-data regimes, initial exploration |

| SwitchBAX | Dynamically switches between InfoBAX and MeanBAX [10] | Robust, parameter-free performance across all data regimes | Full experimental lifecycle |

BAX Experimental Protocol and Workflow

Implementing BAX for a materials discovery campaign involves a sequence of well-defined steps. The following protocol outlines the procedure from problem definition to final analysis.

Pre-Experimental Planning

- Define the Design Space (X): Identify the discrete set of all possible synthesis or measurement conditions. This is an ( N \times d ) matrix, where ( N ) is the number of candidate conditions and ( d ) is the dimensionality of the changeable parameters (e.g., temperature, concentration, catalyst type) [10].

- Specify the Property Space (Y): Determine the ( m ) physical properties of interest (e.g., nanoparticle size, electrochemical stability, magnetic coercivity) that will be measured for each experiment [10].

- Formulate the Experimental Goal as an Algorithm (A): Write a simple filtering algorithm that takes the complete function ( f{*} ) (which maps ( X ) to ( Y )) as input and returns the desired target subset ( \mathcal{T}{*} ) of the design space as output. For example, an algorithm could be: "Return all points ( x ) where property ( y1 ) is between ( a ) and ( b ), and property ( y2 ) is greater than ( c )."

Sequential Experimentation Procedure

The core BAX loop is iterative. The procedure below is agnostic to the specific BAX acquisition strategy (InfoBAX, MeanBAX, or SwitchBAX), as the choice of strategy determines how the "next point" is selected in Step 2.

Initialization:

- Start with a small initial dataset ( D0 = {(x1, y1), ..., (xk, y_k)} ), which can be collected via random sampling or a space-filling design.