Nucleation Energy Barriers: From Classical Theory to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive examination of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation energy barriers, synthesizing foundational classical theories with modern non-classical extensions and computational methodologies.

Nucleation Energy Barriers: From Classical Theory to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation energy barriers, synthesizing foundational classical theories with modern non-classical extensions and computational methodologies. We explore the critical role of nucleation in diverse biomedical contexts, including protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases and biomineralization processes. The content addresses both theoretical frameworks and practical applications, offering researchers and drug development professionals insights into troubleshooting nucleation challenges, optimizing pathways through geometric confinement and interface engineering, and validating models against experimental data. By comparing classical and non-classical perspectives, this review aims to equip scientists with a multifaceted understanding of nucleation control for advancing therapeutic and materials design.

Deconstructing Nucleation: From Classical Foundations to Non-Classical Realities

Core Principles of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) and the Energy Barrier Concept

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) is the most common theoretical model used to quantitatively study the kinetics of nucleation, which is the initial step in the spontaneous formation of a new thermodynamic phase from a metastable state [1]. First derived in the 1930s by Becker and Döring, with roots in earlier work by Volmer, Weber, and Gibbs, CNT provides a conceptual framework for predicting the rate at which nuclei of a new phase form and overcome the energy barrier to growth [2]. The central result of CNT is a prediction for the nucleation rate (R), expressed as (R = NS Z j \exp\left(-\frac{\Delta G^*}{kB T}\right)), where (\Delta G^*) is the free energy barrier, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, (NS) is the number of potential nucleation sites, (j) is the flux of molecules to the nucleus, and (Z) is the Zeldovich factor [1]. The theory makes several key assumptions, most notably the "capillarity approximation," which treats small, nascent nuclei as structureless, spherical droplets possessing the same interfacial properties as the bulk macroscopic material [2] [3].

The Energy Barrier Concept

The core of CNT is the concept of a free energy barrier, (\Delta G), that must be overcome for a stable nucleus to form. This energy change is modeled as a balance between two competing terms: a volume term that is favorable and proportional to the volume of the new phase, and a surface term that is unfavorable and proportional to the surface area created [2] [1].

For a spherical nucleus, this is given by: [ \Delta G = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 \Delta gv + 4\pi r^2 \sigma ] where (r) is the radius of the nucleus, (\Delta gv) is the Gibbs free energy change per unit volume (which is negative for a stable phase), and (\sigma) is the interfacial tension or surface energy [1].

The following conceptual diagram illustrates the relationship between nucleus size and free energy, highlighting the critical radius (r_c) and energy barrier (\Delta G^*):

As the nucleus grows, the (r^3) dependence of the favorable volume term eventually outweighs the (r^2) dependence of the unfavorable surface term. This relationship creates an energy maximum at a specific critical radius, (rc) [1]. The critical radius and the corresponding energy barrier (\Delta G^*) are given by: [ rc = \frac{2\sigma}{|\Delta gv|} \quad \text{and} \quad \Delta G^* = \frac{16\pi \sigma^3}{3(\Delta gv)^2} ] Nuclei smaller than (rc) (called embryos) are unstable and tend to dissolve, while those larger than (rc) are stable and will likely continue to grow [2] [1]. The height of this energy barrier determines the nucleation rate. A higher barrier makes nucleation less probable, while a lower barrier makes it more likely. The barrier is strongly influenced by the supersaturation ((S)) of the system, with higher supersaturation significantly reducing both (r_c) and (\Delta G^*) [2].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Classical Nucleation Theory

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Role in CNT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Radius | (r_c) | The minimum stable nucleus size | Nuclei > (rc) grow; nuclei < (rc) dissolve |

| Energy Barrier | (\Delta G^*) | Maximum free energy for nucleation | Determines probability of nucleation; (R \propto \exp(-\Delta G^*/k_B T)) |

| Interfacial Tension | (\sigma) | Energy per unit area of interface | Primary resistance to nucleation; higher (σ) increases (\Delta G^*) |

| Supersaturation | (S) | Ratio of actual to equilibrium concentration | Drives nucleation; higher (S) decreases (r_c) and (\Delta G^*) |

| Nucleation Rate | (R) | Number of nuclei formed per unit volume per time | Central output of CNT; depends exponentially on (\Delta G^*) |

Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation

CNT distinguishes between two primary nucleation modes. Homogeneous nucleation occurs spontaneously and randomly within a uniform parent phase, without the aid of a foreign surface. While conceptually simpler, it is much rarer in practice than heterogeneous nucleation because it requires overcoming the full energy barrier described above [1].

Heterogeneous nucleation occurs on surfaces, impurities, or pre-existing interfaces (such as dust particles, container walls, or seed crystals). The presence of these foreign bodies lowers the energy barrier by reducing the amount of new surface area that must be created [1]. The energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation, (\Delta G{het}^*), is related to the homogeneous barrier by a scaling factor: [ \Delta G{het}^* = f(\theta) \Delta G_{hom}^*, \quad f(\theta) = \frac{2 - 3\cos\theta + \cos^3\theta}{4} ] where (\theta) is the contact angle between the nucleus and the substrate, a measure of wettability [1]. The function (f(\theta)) is always less than 1, confirming that the barrier for heterogeneous nucleation is always lower. Recent research has further generalized this framework to include the effect of line tension ((\gamma)), an energy associated with the three-phase contact line at geometric singularities like pore edges, which can further reshape the nucleation energy landscape in confined environments [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation

| Feature | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Occurrence | Rare in practice | Much more common |

| Nucleation Site | Bulk parent phase | Surfaces, interfaces, impurities |

| Energy Barrier | (\Delta G{hom}^* = \frac{16\pi \sigma^3}{3(\Delta gv)^2}) | (\Delta G{het}^* = f(\theta) \Delta G{hom}^*) |

| Barrier Factor | (f(\theta) = 1) | (0 < f(\theta) < 1) |

| Practical Control | Difficult to control | Can be influenced by surface engineering |

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

In-situ Cryo-TEM for Ice Nucleation

Advanced techniques like in-situ cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) allow direct, molecular-resolution observation of nucleation events. A 2025 study used this method to map the pathway of ice formation (Ice I) from vapor deposition on graphene substrates at 102 K and (10^{-6}) Pa pressure [5].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Environment: Water vapor is introduced onto a translucent graphene substrate held at cryogenic temperatures (102 K) within the cryo-TEM.

- Real-Time Imaging: The process is recorded with millisecond temporal and picometer spatial resolution.

- Pathway Analysis: Sequential TEM images and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis of the diffraction patterns are used to identify the structure and orientation of nascent ice nuclei.

Key Observations: The study observed an adsorption-mediated pathway where clusters of amorphous solid water formed first, serving as an adsorption layer. Isolated crystalline nuclei of hexagonal ice (Ice Ih) and cubic ice (Ice Ic) then appeared within this layer. The subsequent growth was governed by competitive processes like Ostwald ripening (where larger nuclei grow at the expense of smaller ones) and oriented aggregation, eventually leading to a mature, faceted ice crystal [5]. This provides direct evidence of a non-classical, multi-step nucleation pathway.

Direct Observation in Colloidal Systems

Another 2025 study used binary colloidal suspensions as a model system to observe non-classical crystallization pathways directly. In this system, oppositely charged microscopic particles act as "model atoms," and their interactions can be finely tuned by changing the salt concentration in the solution [6].

Experimental Workflow:

- System Preparation: Positively and negatively charged colloidal particles are prepared in a precisely controlled salt solution and mixed in a 1:1 ratio.

- Initiation and Imaging: The mixture is transferred to an observation cell, and the assembly process is monitored using bright-field microscopy and 3D confocal microscopy.

- Interaction Control: A continuous dialysis setup is used to gradually lower the salt concentration over time, providing spatiotemporal control over the interaction strength between particles and allowing the identification of optimal conditions for crystal growth [6].

Key Observations: The research revealed a two-step process: 1) rapid condensation of metastable, amorphous "blobs" from the gas phase, and 2) crystal nucleation within these blobs, followed by growth into large faceted crystals. The growth proceeded via four simultaneous mechanisms: monomer addition, Ostwald ripening, direct blob absorption, and oriented attachment of crystals [6].

The following diagram synthesizes the workflows of these two key experimental approaches:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Nucleation Experiments

| Material/Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Translucent Graphene Substrates | Provides an atomically flat, well-defined surface for heterogeneous nucleation. | Serves as the substrate for vapor deposition in cryo-TEM ice nucleation studies [5]. |

| Charged Colloidal Particles | Acts as model atoms or ions with tunable interaction potentials. | Used as monomers in binary colloidal crystal formation studies [6]. |

| Polymer Brush Coatings | Provides steric repulsion to prevent irreversible aggregation of particles. | Coats colloidal particles to control the overall pair potential in combination with electrostatic attraction [6]. |

| Salt Solutions (e.g., NaCl) | Controls the Debye screening length, thereby tuning the range and strength of electrostatic interactions. | Used to precisely control interaction strength in colloidal crystallization experiments [6]. |

| D₂O/H₂O Solvent Mixtures | Creates a density-matched solvent to negate the effects of gravitational settling. | Used in control experiments to confirm that crystallization mechanisms are not influenced by sedimentation [6]. |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | Acts as a dissolved gas to create supersaturation in analog systems. | Used to saturate polymer liquids in experiments modeling bubble nucleation in magmas [7]. |

Limitations and Modern Extensions Beyond CNT

Despite its conceptual utility, CNT has well-documented limitations. It often fails to make accurate quantitative predictions of nucleation rates, sometimes erring by many orders of magnitude [2] [3]. A major source of error is the "capillarity approximation," which assumes that microscopic nuclei have the same interfacial tension ((\sigma)) as a flat, macroscopic interface, an assumption that is questionable for clusters consisting of only a few molecules [2].

These limitations have driven the development of non-classical theories, which have been directly observed in modern experiments. Key non-classical pathways include:

- The Prenucleation Cluster (PNC) Pathway: In this two-step mechanism, ions or molecules first form stable, dynamic clusters that exist as solutes without a defined phase interface. These PNCs then undergo an internal reorganization to form a phase-separated nucleus once a critical ion activity product is reached [2]. This contrasts with CNT's one-step model of stochastic monomer addition.

- Aggregation-Based Pathways: An alternative non-classical mechanism involves the aggregation of pre-nucleation clusters or pre-critical nuclei. When the collision rate of these particles is faster than their dissolution rate, they can aggregate to form a stable nucleus, effectively "tunneling" through the energy barrier predicted by CNT [2] [6]. The 2025 colloidal study provided a clear example, where metastable amorphous blobs condensed from the gas phase before evolving into crystals [6].

- Shear-Induced Nucleation: Recent research has shown that mechanical stress, such as shear forces from flow, can itself trigger nucleation. This mechanism is relevant in volcanic conduits where flowing magma experiences significant shear, inducing bubble formation through mechanical stress alone, not just pressure reduction [7]. This represents a significant departure from the traditional CNT framework.

Classical Nucleation Theory, with its central concept of an energy barrier governed by a volume-surface trade-off, remains a foundational framework for understanding the initial stages of phase transitions. Its principles for both homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation are indispensable for researchers designing processes in fields from drug development to materials science. However, the theory's quantitative shortcomings and simplifying assumptions are now clear. The direct observational power of modern techniques like in-situ cryo-TEM and tunable colloidal models is revealing a rich landscape of non-classical pathways, such as two-step nucleation and aggregation-mediated mechanisms. A comprehensive understanding of nucleation now requires integrating the established principles of CNT with these more complex, yet prevalent, pathways that govern how order emerges from disorder in nature and industry.

Nucleation, the initial formation of a new thermodynamic phase from a metastable parent phase, represents a fundamental process governing phenomena ranging from atmospheric science to pharmaceutical development. The energy barrier required to form a stable nucleus dictates the kinetics and outcome of these phase transitions. This energy barrier differs profoundly between homogeneous nucleation, which occurs spontaneously within a perfect bulk phase, and heterogeneous nucleation, which is catalyzed at interfaces or on impurity surfaces. Understanding the comparative energetic landscape of these two pathways is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for controlling material synthesis, drug crystallization, and industrial processes.

The context of a broader thesis on nucleation energy barriers research reveals a critical knowledge gap: while classical nucleation theory (CNT) provides a foundational framework, modern experimental and simulation techniques demonstrate that real-world systems often deviate significantly from these idealized models. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive energetic analysis of homogeneous versus heterogeneous nucleation, supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and conceptual visualizations.

Theoretical Foundations of Nucleation Energy Barriers

Classical Nucleation Theory Framework

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) serves as the cornerstone for understanding the energetics of phase formation. According to CNT, the total free energy change (ΔG) for nucleus formation comprises two competing terms: a bulk free energy reduction proportional to the volume of the new phase and a surface free energy penalty proportional to the interfacial area. For a spherical nucleus, this relationship is expressed as:

[ \Delta G = -\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 \Delta g_v + 4\pi r^2 \gamma ]

where r is the nucleus radius, Δg_v is the bulk free energy change per unit volume, and γ is the interfacial tension [8].

The maximum of this free energy function defines the critical nucleation barrier (Wc) and critical nucleus size (rc):

[ Wc = \frac{16\pi\gamma^3}{3(\Delta gv)^2} \quad \text{and} \quad rc = \frac{2\gamma}{\Delta gv} ]

These parameters represent the energetic hurdle and minimum stable size that must be overcome for nucleation to proceed [8]. The steady-state nucleation rate (J) follows an Arrhenius-type dependence on this energy barrier:

[ J = J0 \exp\left(-\frac{Wc}{k_B T}\right) ]

where J0 is a kinetic pre-exponential factor, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is absolute temperature [8].

The Energetic Distinction: Homogeneous versus Heterogeneous

The fundamental distinction between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation lies in the modification of the energy landscape by preferential nucleation sites:

- In homogeneous nucleation, the energy barrier must be overcome through random thermal fluctuations alone, requiring high supersaturation levels.

- In heterogeneous nucleation, the presence of a foreign substrate reduces the effective surface area of the nucleus-liquid interface, thereby lowering the activation barrier and enabling nucleation at lower supersaturation.

The reduction factor (f(θ)) depends on the contact angle (θ) between the nucleus and substrate according to:

[ f(\theta) = \frac{(2+\cos\theta)(1-\cos\theta)^2}{4} ]

Thus, the heterogeneous nucleation barrier becomes:

[ Wc^{\text{heter}} = Wc^{\text{homo}} \cdot f(\theta) ]

This relationship explains why heterogeneous nucleation typically dominates in real-world systems containing impurities, containers, or catalytic surfaces [8].

Quantitative Energetic Comparison

The following tables synthesize quantitative data from recent investigations, highlighting key differences in nucleation barriers across various systems.

Table 1: Comparative Nucleation Energy Barriers in Different Systems

| System | Nucleation Type | Temperature (K) | Critical Barrier (W_c) | Critical Size (r_c) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water vapor on SiO₂ | Heterogeneous | 298 | ~10 kBT | ~20 Å | [9] |

| Water vapor (bulk) | Homogeneous | 298 | ~50 kBT | ~50 Å | [9] |

| Al-4at%Cu alloy | Homogeneous | 0.42 Tm* | ~18 kBT | ~30 atoms | [10] |

| Nanobubbles on gold | Heterogeneous | 400-500 | 7.4×10⁻²⁰ J | ~40 nm | [11] |

| Drug compound (example) | Heterogeneous | 310 | ~5 kBT | ~100 Å | [12] |

*Tm represents melting temperature (935 K for Al-4at%Cu) [10]

Table 2: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Parameters for Nucleation Studies

| Parameter | Water-SiO₂ System [9] | Al-Cu Alloy System [10] |

|---|---|---|

| Software | Materials Studio | LAMMPS |

| Ensemble | NPT | NPT |

| Potential | COMB3 + TIP4P | EAM (Embedded Atom Method) |

| System Size | 20 Å SiO₂ particle + gas molecules | 51,200 atoms |

| Simulation Time | 40 ns | 1000 ps |

| Temperature Control | Nose-Hoover thermostat | Nose-Hoover thermostat |

| Analysis Method | Cluster evolution, Interaction energies | Grain segmentation, DXA |

Experimental Methodologies for Energetic Analysis

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Competitive Nucleation

Recent molecular dynamics investigations have provided unprecedented insights into the competitive dynamics between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways. Yang et al. employed sophisticated simulation methodologies to analyze water vapor nucleation on SiO₂ particles in multi-component flue gas systems [9].

Protocol Details:

- System Construction: A 20 Å spherical SiO₂ particle positioned at the center of the simulation box with gas molecules (H₂O, CO₂, N₂, O₂, SO₂) randomly distributed surrounding it.

- Force Field Selection: COMB3 potential for SiO₂ interactions and TIP4P model for water molecules, validated against experimental contact angles.

- Simulation Conditions: NPT ensemble with Nose-Hoover thermostat at temperatures ranging from 260K to 400K and water content varying from 100 to 700 molecules.

- Analysis Technique: Tracking oxygen atom coordination numbers to identify nucleation sites and calculating interaction energies to determine thermodynamic favorability.

This methodology revealed that heterogeneous nucleation preferentially occurs around oxygen atoms on the SiO₂ surface at lower supersaturation, while homogeneous nucleation emerges in the bulk vapor phase only at higher supersaturation levels, with direct competition observed between these pathways [9].

Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy for Nanobubble Nucleation

Innovative optical techniques have enabled direct measurement of nucleation kinetics at previously inaccessible scales. Lin et al. developed a sophisticated apparatus combining optical tweezers with surface plasmon resonance microscopy (SPRM) to quantify heterogeneous nucleation of nanobubbles on gold surfaces [11].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: A coverslip coated with a 50-nm-thick gold film is assembled into a fluid chamber containing pure water.

- Localized Heating: An optical tweezers system focuses a 1064 nm laser beam (25.92 mW power) to a 0.87 μm spot on the gold film, creating rapid local heating.

- Nucleation Detection: SPRM operating at 680 nm continuously monitors the gold-water interface with 1.5 ms temporal resolution, detecting nanobubble formation through characteristic wave-like patterns.

- Temperature Calibration: The same SPRM signals are calibrated against known temperature-dependent refractive index changes of water to determine local temperature at nucleation sites.

- Kinetic Analysis: Repeated heating-cooling cycles (hundreds of repetitions) generate statistical distributions of nucleation induction times from which nucleation rates are calculated.

This approach achieved remarkable spatial resolution (~100 nm) for mapping nucleation rates and directly determined an activation energy barrier of 7.4×10⁻²⁰ J for nanobubble formation, revealing that surface chemistry rather than geometrical roughness primarily regulates heterogeneous nucleation barriers [11].

Isothermal Solidification of Metallic Alloys

Molecular dynamics simulations of metallic alloy solidification provide insights into homogeneous nucleation behavior under controlled conditions. A comprehensive study of Al-4at%Cu alloy employed the following methodology [10]:

Simulation Protocol:

- System Preparation: A quasi-two-dimensional simulation box (32.4 × 32.4 × 0.8 nm) containing 51,200 atoms with 4% Cu randomly distributed in aluminium.

- Melting Procedure: The initial FCC crystal structure is heated from 300K to 1.48 Tm (1383K) and relaxed for 200 ps to ensure complete melting.

- Isothermal Solidification: The uniform melt is rapidly quenched to target temperatures (0.6 Tm to 0.39 Tm) for isothermal solidification with at least 1000 ps simulation time.

- Structural Analysis: The Open Visualization Tool (OVITO) with grain segmentation algorithms identifies nucleation events and tracks microstructure evolution.

- Statistical Validation: Each simulation condition is repeated five times to ensure data reliability.

This approach identified a critical homogeneous nucleation temperature of approximately 0.42 Tm (393K) for the Al-Cu system and revealed a transition from spontaneous nucleation at high temperatures to divergent nucleation at lower temperatures [10].

Visualization of Nucleation Concepts and Methodologies

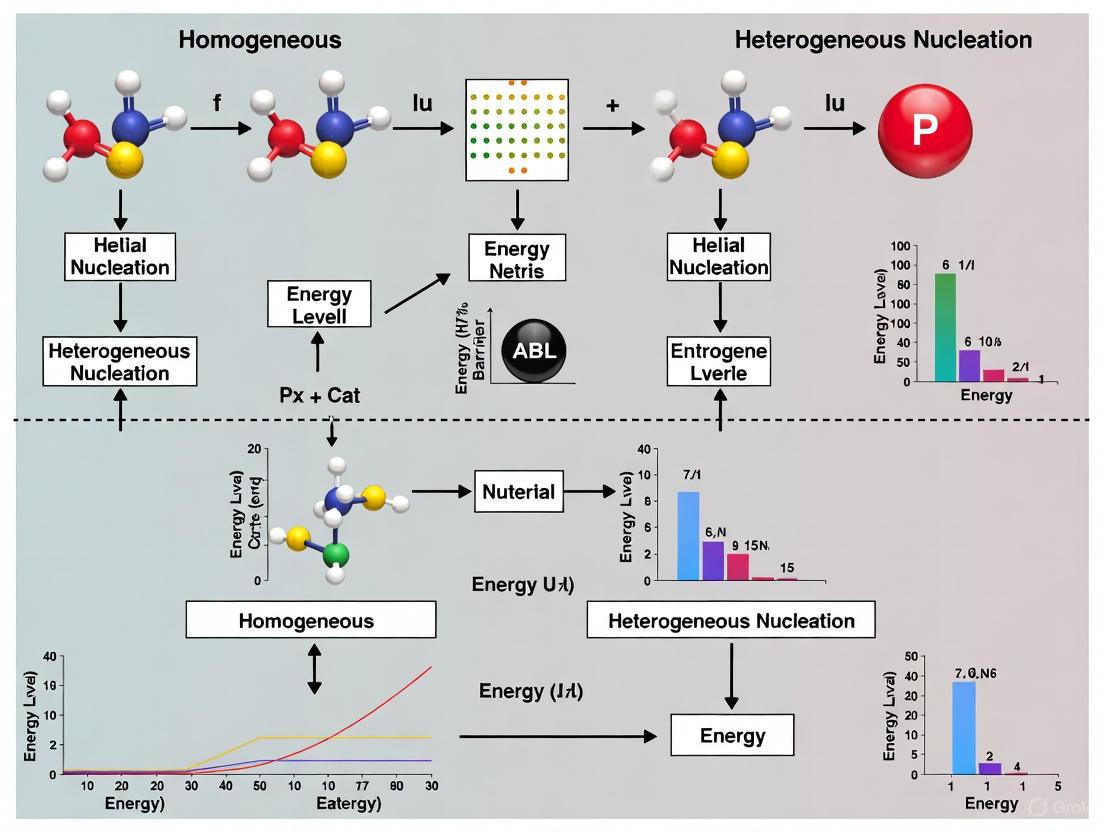

Diagram 1: Comparative Energy Pathways for Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation. The heterogeneous pathway shows a significantly reduced energy barrier due to catalytic surface effects.

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Nucleation Energy Barrier Measurement. The methodology combines computational and experimental approaches for comprehensive analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Nucleation Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| SiO₂ Nanoparticles | Model heterogeneous nucleation substrate with well-defined surface properties | Water vapor condensation studies [9] |

| Gold-coated Coverslips | Plasmonic heating substrate for controlled nanobubble nucleation | SPRM nucleation rate mapping [11] |

| Al-Cu Alloy Precursors | Model system for metallic solidification studies | Homogeneous nucleation in alloy melts [10] |

| COMB3 & EAM Potentials | Molecular dynamics force fields for accurate interatomic interactions | SiO₂ and metallic alloy simulations [9] [10] |

| Pharmaceutical Compounds | Low-solubility drugs for precipitation kinetics studies | Oral absorption simulation [12] |

| Nose-Hoover Thermostat | Temperature control algorithm in molecular dynamics | Maintaining isothermal conditions [9] [10] |

Discussion and Research Implications

The comparative energetic analysis reveals that heterogeneous nucleation typically dominates natural and industrial processes due to its significantly reduced activation barrier. However, the competition between homogeneous and heterogeneous pathways depends critically on system-specific conditions including supersaturation level, temperature, and surface properties [9].

In pharmaceutical development, understanding these nucleation barriers enables controlled crystallization of active ingredients, directly impacting drug bioavailability and stability [12]. For environmental applications, manipulating nucleation pathways improves fine particle removal efficiency from flue gases by promoting favorable condensation growth [9]. In materials science, controlling homogeneous nucleation through extreme supercooling produces unique nanocrystalline structures with enhanced properties [10].

Recent advances in characterization techniques, particularly molecular dynamics simulations and surface plasmon resonance microscopy, have transformed our ability to quantify nucleation energy barriers at previously inaccessible temporal and spatial scales [9] [11]. These methodologies continue to refine our understanding beyond classical nucleation theory, revealing complex relationships between surface chemistry, molecular structure, and nucleation energetics.

This energetic analysis demonstrates that the distinction between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation extends far beyond academic theory to practical applications across scientific and industrial domains. The significantly reduced energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation explains its prevalence in real-world systems, while controlled homogeneous nucleation enables specialized material fabrication. Continued refinement of experimental and computational methodologies will further elucidate the subtle energetic landscapes governing nucleation phenomena, enabling more precise control of phase transitions in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to advanced material synthesis.

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) has served for decades as the foundational framework for understanding phase transitions, from crystallization to ice formation. However, advanced experimental and computational techniques now reveal its limitations in describing the intricate pathways many systems traverse. This review synthesizes growing evidence that non-classical, multi-step nucleation (MSN) pathways are prevalent across diverse fields. We examine molecular-resolution studies that demonstrate how phases often form through intermediate states rather than the direct, single-step transition envisaged by CNT. By integrating quantitative data, experimental protocols, and mechanistic insights from recent research, this analysis underscores the need for revised theoretical models that incorporate complexity, intermediates, and the significant role of interfaces and confinement in reshaping nucleation energy landscapes.

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides a fundamental description of phase transitions, positing that a new phase forms via a stochastic fluctuation that leads to the direct formation of a critical nucleus, beyond which growth becomes thermodynamically favorable. This model simplifies the nucleus as having the same interior state as the macroscopic bulk phase and uses a spherical cap model to describe heterogeneous nucleation at ideal, smooth surfaces [13] [4]. For over half a century, this framework has been widely applied across disciplines from protein crystallization to ice formation.

However, a renaissance in nucleation studies, fueled by advanced characterization techniques and computational methods, has increasingly challenged CNT's core assumptions [13]. A key discovery is the apparent ubiquity of multi-step nucleation (MSN), where systems traverse one or more metastable intermediate states before arriving at the stable phase [13]. This review examines the evidence for these non-classical pathways, exploring how they reshape our understanding of nucleation barriers and offering new principles for controlling phase transitions in fields ranging from materials science to drug development.

Experimental Evidence for Non-Classical Pathways

Insights from Protein Crystallization

Studies on protein crystallization have been pivotal in demonstrating classical nucleation behavior can persist even in systems with complex phase landscapes.

- Molecular Resolution Imaging: Atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies of glucose isomerase protein crystallization on mica revealed that subcritical clusters possessed the same interior state as the crystalline bulk phase. This direct observation validated a key CNT assumption—simultaneous density increase and crystallinity—in a system known for rich phase behavior [13].

- System Characteristics:

- Substrate & Interactions: Crystallization occurred on freshly cleaved muscovite mica, mediated by electrostatic bridges from divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) between the negatively charged protein and mica surface [13].

- Role of a Diffusive Wetting Layer: Beyond a critical cation concentration, a mobile layer of surface-diffusing protein molecules formed, within which crystalline nuclei emerged after an induction period [13].

- Inhibition by Monovalent Salts: The addition of NaCl halted nucleation without significantly altering solution properties, suggesting it disrupts specific protein-protein ionic bridges within nascent clusters [13].

Heterogeneous Ice Nucleation: A Complex Landscape

Ice formation provides compelling examples of non-classical pathways, particularly under heterogeneous conditions.

- Adsorption-Mediated Pathways: In-situ cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) of ice formation from vapor deposition on graphene at 102 K revealed an initial adsorption layer of amorphous solid water. This amorphous precursor subsequently facilitated the spontaneous nucleation of hexagonal ice (Ice Ih) and cubic ice (Ice Ic) nuclei [5].

- Competitive Growth and Ostwald Ripening: The process involved competitive nucleation of multiple ice polymorphs. Smaller nuclei of Ice Ih dissolved while larger ones grew, a signature of Ostwald ripening. Concurrently, transient cubic ice nuclei appeared, competed for molecules, and dissolved without transforming into the stable hexagonal phase, indicating they were not direct intermediates but kinetic competitors [5].

- Formation of Heterostructures: Mature Ice Ih crystallites were found with a thin, epitaxial shell of cubic ice on their prism facets. This stable Ih/Ic heterostructure, formed during the faceting process, highlights the complex interfacial energy minima that govern final crystal morphology and are not captured by CNT [5].

Table 1: Key Experimental Observations in Heterogeneous Ice Nucleation

| Observation | Technique | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Amorphous ice adsorption layer | In-situ cryo-TEM | Demonstrates a non-classical, precursor-mediated pathway [5] |

| Co-nucleation of Ice Ih and Ice Ic | In-situ cryo-TEM & FFT analysis | Shows multiple phases can nucleate independently from a common precursor [5] |

| Ostwald ripening between Ice Ih nuclei | Real-time TEM imaging | Confirms growth is driven by interfacial free energy minimization [5] |

| Epitaxial Ice Ic shell on Ice Ih | HR-TEM & FFT micro-domain analysis | Reveals complex equilibrium structures shaped by interfacial energetics [5] |

The Role of Confinement and Line Tension

Nanoscale confinement introduces additional complexity that challenges classical models. Recent theoretical work has developed a generalized nucleation theory that incorporates line tension—an energy contribution from the three-phase contact line—which becomes significant at geometric singularities like edges and pores [4].

- Beyond the Capillary Approximation: Classical models treat line tension as a constant, leading to ambiguous results. The new theory derives it as a function of Laplace pressure, pore geometry, and wettability, showing it is a geometry-dependent quantity that can significantly reshape the nucleation energy barrier [4].

- Mechanism of Action: In nanopores, the pinning of the contact line at geometric edges creates an effective geometric correction to the Helmholtz free energy. This "pinning-induced line tension" can either increase or decrease the nucleation barrier, offering a tunable, geometry-mediated mechanism to control phase transitions in confined systems [4].

Computational and Theoretical Advances

Computational methods have been instrumental in elucidating molecular-scale mechanisms that are often inaccessible to experiments.

Uncovering Atomic-Scale Mechanisms in Ice Nucleation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have provided detailed insights into the role of substrates in ice nucleation.

- Deep Potential MD for Accuracy: Using a deep neural network potential trained with ab initio accuracy, researchers simulated ice nucleation on silver iodide (AgI), a highly efficient ice-nucleating agent. This approach combined computational efficiency with high accuracy [14].

- Asynchronous Crystallization Mechanism: Simulations revealed that the AgI substrate facilitates the reconstruction of the disordered hydrogen bond network at the interface into an ice-like hexagonal layer. This process occurs asynchronously, with the solid-like layer forming before full crystallization, representing a non-classical pathway [14].

- Substrate Influence on Ice Growth: The influence of the AgI substrate propagates through the hydrogen bond network, creating a pre-ordered region at the ice-water interface. This pre-ordering reduces the ice growth rate to approximately one-third of that under homogeneous conditions [14].

Deterministic Nucleation in Carbon Nanotubes

The synthesis of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) with specific chirality remains a major challenge. Recent theoretical work proposes a shift from stochastic growth models to a deterministic nucleation theory.

- Vector Sum Rule: A universal vector sum rule derived from topological analysis shows that a nanotube's chirality (n, m) is uniquely determined by the vector sum of the coordinates of the six pentagons within the cap structure. This means chirality is encoded at the nucleation stage [15].

- Structural Matching to Catalysts: Preferential formation of specific chiralities, like (12,6), is proposed to result from epitaxial matching between a six-fold symmetric carbon cap and specific catalyst facets (e.g., ⟨1,1,1⟩). This suggests that controlling the catalyst surface structure at nucleation can program the resulting nanotube chirality [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Molecular-Resolution Mapping of Ice Nucleation using In-Situ Cryo-TEM

This protocol outlines the methodology for directly observing ice nucleation pathways [5].

- 1. Substrate Preparation:

- Material: Translucent graphene substrates.

- Preparation: Clean and mount substrates securely within the specialized cryo-TEM holder under controlled atmospheric conditions to prevent contamination.

- 2. In-Situ Chamber Setup:

- Environmental Control: Cool the system to the target temperature (e.g., 102 K) and establish a low-pressure environment (e.g., 10⁻⁶ Pa) within the microscope's environmental chamber.

- Vapor Introduction: Introduce water vapor at a controlled, precise flux to initiate the deposition freezing process.

- 3. Real-Time Imaging and Data Acquisition:

- Image Capture: Use the cryo-TEM's high-resolution real-time imaging capability (millisecond temporal, picometer spatial resolution) to record the nucleation and growth process.

- FFT Analysis: Perform sequential Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on acquired images to identify the crystallographic structure of emerging nuclei (e.g., distinguishing Ice Ih from Ice Ic by their distinct d-spacings and lattice constants).

- 4. Data Analysis:

- Nuclei Tracking: Track the size, morphology, and appearance/disappearance of individual nuclei over time.

- Ostwald Ripening Assessment: Quantify the growth of larger nuclei at the expense of smaller ones.

- Heterostructure Characterization: Analyze high-resolution micrographs and FFT patterns of mature crystallites to identify composite structures, such as the Ice Ic shell on Ice Ih.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Heterogeneous Ice Nucleation

This protocol describes the computational approach to studying ice nucleation on a substrate like AgI [14].

- 1. Potential Development:

- Method: Train a deep neural network potential (Deep Potential) using a dataset generated from ab initio (e.g., Density Functional Theory) calculations of water-substrate interactions. This ensures the MD simulations are both accurate and computationally efficient.

- 2. System Construction:

- Simulation Box: Create a simulation box containing the AgI substrate and a sufficient number of water molecules to model the liquid phase and interface.

- Equilibration: First, equilibrate the system at the target temperature and pressure to establish a stable initial state.

- 3. Umbrella Sampling or Metadynamics:

- Technique: Employ enhanced sampling techniques to overcome the high free energy barrier of nucleation.

- Collective Variables: Define appropriate collective variables (e.g., local bond order parameters like Steinhardt parameters) that distinguish the liquid from the ice phase.

- 4. Trajectory Analysis:

- Free Energy Surface: Calculate the free energy surface as a function of the chosen collective variables to identify metastable intermediates and transition states.

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Quantify the structure and dynamics of the hydrogen bond network at the water-substrate interface to understand the mechanism of the initial ice-like layer formation.

- Growth Rate Calculation: Monitor the evolution of the ice phase over time to compute growth rates under the influence of the substrate.

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Classical vs. Non-Classical Nucleation Pathways

The following diagram contrasts the fundamental mechanisms of Classical Nucleation Theory with a prevalent multi-step nucleation model.

Experimental Workflow for Cryo-TEM of Ice Nucleation

This diagram outlines the key steps in the experimental protocol for mapping ice nucleation pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Muscovite Mica | An atomically flat substrate for heterogeneous crystallization studies. | Provides a defined surface for protein (e.g., glucose isomerase) 2D crystallization [13]. |

| Divalent Cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) | Act as electrostatic bridges between negatively charged surfaces and molecules. | Essential for inducing glucose isomerase crystallization on mica; exhibits Hofmeister series effects [13]. |

| Translucent Graphene Substrates | Electron-transparent substrate for in-situ TEM. | Serves as a defined surface for observing ice nucleation from vapor deposition [5]. |

| Silver Iodide (AgI) | A highly efficient ice-nucleating agent. | Used in computational and experimental studies to understand substrate-mediated ice nucleation [14]. |

| Deep Neural Network Potentials | A machine learning-based force field for molecular dynamics. | Enables accurate and efficient simulation of complex processes like ice nucleation on AgI [14]. |

| Specialized Cryo-TEM Holder | Allows for control of temperature and atmosphere inside the TEM. | Essential for in-situ observation of ice nucleation and growth under controlled non-equilibrium conditions [5]. |

The collective evidence from protein crystallization, ice formation, and carbon nanotube synthesis firmly establishes that non-classical, multi-step nucleation pathways are not exotic exceptions but common phenomena in heterogeneous environments. The persistence of classical behavior in specific systems, such as glucose isomerase on mica, highlights that the dominance of a single-step or multi-step pathway is context-dependent, influenced by specific molecular interactions, substrate properties, and interfacial energies [13].

Future research must continue to develop and integrate advanced experimental and computational tools—like in-situ cryo-TEM and machine-learning-accelerated simulations—to build a more predictive, multi-scale understanding of nucleation. The emerging ability to quantify previously neglected factors, such as geometry-dependent line tension [4], and to deterministically encode outcomes at the nucleation stage, as in CNT chirality control [15], points toward a future where phase transitions can be rationally designed and precisely controlled across a vast range of scientific and industrial applications.

The Role of Metastable Intermediates and the Ostwald Step Rule

The crystallization of solids from solution, melt, or vapor is a fundamental process across diverse scientific and industrial fields, from pharmaceutical development to glaciology. Contrary to simplistic models of direct formation, this process often proceeds through a series of transient, less-stable phases known as metastable intermediates. This whitepaper examines the central role of these intermediates through the lens of Ostwald's rule of stages, which posits that the evolution toward a stable crystalline phase typically occurs through a succession of increasingly stable polymorphs. Within the context of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation energy barriers, we explore the kinetic and thermodynamic principles governing this stepwise progression. By integrating recent experimental breakthroughs in molecular-resolution imaging with advanced computational simulations, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding non-classical nucleation pathways. The insights presented herein are particularly crucial for researchers in drug development and materials science, where controlling polymorphic outcomes determines critical material properties and product efficacy.

Theoretical Framework: Ostwald’s Rule and Nucleation Energy Barriers

Ostwald's rule of stages, formulated in 1897, represents a cornerstone of modern crystallization theory. It describes a common tendency in which a system undergoing a phase transition does not directly form the most thermodynamically stable phase. Instead, it first nucleates into the least stable polymorph that is most kinetically accessible from the parent phase [16]. This initial phase, often characterized by higher solubility and lower stability, subsequently undergoes solid-state transformations through a series of metastable intermediates until the global free energy minimum—the stable phase—is reached.

The prevalence of this pathway is rooted in the interplay between thermodynamic driving forces and kinetic barriers. The initial metastable polymorph more closely resembles the structural state of the parent phase (e.g., a solution or melt), resulting in a lower interfacial free energy and thus a lower nucleation barrier compared to the stable phase [17]. This kinetic advantage allows it to form more rapidly, even though it is thermodynamically disfavored at equilibrium.

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) and Its Limitations: CNT provides a foundational model, describing nucleation as a single-step process where an embryo of the new phase must overcome a single free energy barrier. This barrier arises from the competition between the bulk free energy gain of forming the new phase and the surface free energy cost of creating the interface [17]. However, the widespread observation of metastable intermediates underscores the limitation of this one-step model for many real-world systems.

Non-Classical Nucleation Pathways: Increasing evidence points to the prevalence of non-classical, multi-step nucleation pathways. These often involve the initial formation of metastable liquid or amorphous precursors that serve as a pre-ordering stage before the emergence of long-range crystalline order [17]. For instance, during vapor deposition freezing, the initial formation of clusters of amorphous solid water precedes the spontaneous nucleation of crystalline ice [5]. This amorphous precursor more closely resembles the vapor phase, thereby reducing the initial kinetic barrier to nucleation.

The Role of Heterogeneous Substrates: Heterogeneous nucleation, where a foreign substrate catalyzes the formation of a new phase, profoundly influences the activation of Ostwald's rule. The substrate reduces the overall free energy barrier by lowering the interfacial energy penalty. Recent molecular-resolution studies show that substrates can enable adsorption-mediated nucleation pathways. For example, on cryogenic graphene, water vapor first forms an adsorption layer of amorphous ice, which then facilitates the spontaneous nucleation of crystalline ice I [5]. The nature of the substrate can also alter the progression through metastable intermediates, as demonstrated by the influence of specific phospholipid species on cholesterol crystallization sequences [18].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Nucleation Pathways

| Feature | Classical Nucleation Theory | Non-Classical Nucleation (with Metastable Intermediates) |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway | Single-step | Multi-step |

| Intermediate States | None | Metastable crystalline, amorphous, or liquid states |

| Governing Principle | Minimization of critical free energy barrier | Progression through states of increasing stability (Ostwald's Rule) |

| Energy Landscape | Single barrier | Complex landscape with multiple minima and barriers |

| Role of Interface | Creates a uniform energy barrier | Can stabilize specific intermediates and lower specific transition barriers |

Molecular Mechanisms and Energetics of Metastable Intermediates

The journey from a disordered fluid to a stable crystal is governed by a complex energy landscape, not a simple path. This landscape is spanned by numerous free energy minima corresponding to different polymorphs and metastable intermediate states. The specific pathway a system follows is dictated by the relative heights of the kinetic barriers separating these states, which are influenced by molecular interactions and interfacial energies.

A critical mechanism observed in the evolution of metastable intermediates is Ostwald ripening. This process occurs when larger crystallites grow at the expense of smaller ones due to the higher solubility and surface energy of smaller particles [5]. This surface-energy-driven process was directly observed in the crowded nucleation of ice, where a smaller ice Ih nucleus (Ih2) gradually diminished and disappeared while a nearby larger ice Ih nucleus (Ih1) continued to grow [5]. This ripening process represents a system's progression toward thermodynamic equilibrium by reducing the total interfacial energy.

The following diagram illustrates the typical sequence of stages governed by Ostwald's Rule, from the initial parent phase to the final stable crystal, including key transformation processes.

The final crystal habit, or shape, is a direct manifestation of the system reaching a minimum in interfacial free energy, a principle described by Wulff construction [5]. This was vividly demonstrated in ice formation, where initial convex crystallites without sharp facets eventually transformed into well-formed euhedral hexagonal prisms over time, representing the equilibrium crystal shape for ice Ih under the experimental conditions [5].

Experimental Evidence Across Material Systems

Empirical observations across a wide range of materials consistently validate the operation of Ostwald's rule and the involvement of metastable intermediates.

Ice Formation (Water)

A landmark 2025 study utilizing in-situ cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) provided unprecedented molecular-resolution mapping of ice formation from vapor deposition. The observed pathway was distinctly multi-step [5]:

- Amorphous Adsorption: Clusters of amorphous solid water formed on the cryogenic substrate, creating an initial adsorption layer.

- Spontaneous Crystallization: Multiple crystalline nuclei of hexagonal ice (Ice Ih) and cubic ice (Ice Ic) emerged from this amorphous precursor.

- Competitive Ripening and Growth: A competitive growth phase ensued, where larger Ice Ih nuclei grew at the expense of smaller ones via Ostwald ripening, and transient Ice Ic nuclei dissolved without a solid-state transition.

- Equilibrium Faceting: The initial convex crystallites of Ice Ih eventually transformed into well-faceted, plate-like stout hexagonal prisms, consistent with Wulff's construction.

Notably, the cubic ice (Ice Ic) acted as a competitor for molecular attachment rather than a direct intermediate to the stable hexagonal ice (Ice Ih), highlighting that not all observed metastable phases are necessarily "on-pathway" intermediates in a sequential transformation [5].

Cholesterol Crystallization

The influence of microenvironmental composition on metastable intermediates is starkly evident in cholesterol crystallization from bile. A seminal study demonstrated that phospholipid molecular species significantly impact the crystal habits and transition sequences of metastable intermediates [18].

In bile salt-rich model bile, cholesterol initially crystallized as filamentous crystals, which were covered by a surface layer of specific lecithin molecules. These filamentous crystals then transformed through various metastable intermediates into the classical plate-like cholesterol monohydrate crystals [18]. The molecular species of phospholipids adsorbed onto the initial filamentous crystals were more saturated than those in the whole bile, providing chemical evidence for a vesicular origin of the critical cholesterol nucleus. Furthermore, the type of phospholipid dictated the transformation kinetics: certain species induced rapid precipitation of short filaments that slowly became plate-like, while others markedly retarded crystallization, with filamentous and intermediate crystals appearing only after plate-like crystals had formed [18].

Calcium Carbonate and Other Systems

The precipitation of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) is a classic example of Ostwald's rule. Precipitation often proceeds first through the formation of an unstable colloidal sol or gel, which then evolves into vaterite—the least stable and most soluble polymorph of CaCO₃. Depending on solution temperature, this vaterite subsequently transforms into the more stable aragonite or the most stable polymorph, calcite [16]. This progression—amorphous precursor → vaterite → aragonite/calcite—perfectly illustrates the stepwise stabilization predicted by Ostwald.

Similar complex pathways involving multiple amorphous and crystalline precursors have been observed in the synthesis of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and in the crystallization of proteins and polymers [17].

Table 2: Metastable Intermediates in Different Material Systems

| System | Initial Metastable Intermediate(s) | Final Stable Phase | Key Transformation Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Ice [5] | Amorphous Solid Water, Cubic Ice (Ic) | Hexagonal Ice (Ih) | Ostwald Ripening, Oriented Aggregation |

| Cholesterol [18] | Filamentous Crystals | Plate-like Cholesterol Monohydrate | Arborization Pattern, Solid-State Transition |

| Calcium Carbonate [16] | Amorphous Calcium Carbonate, Vaterite | Calcite (or Aragonite) | Solvent-Mediated Dissolution/Recrystallization |

| Organic Compounds [17] | Metastable Polymorphs (e.g., fibrous benzamide) | Stable Polymorph (e.g., rhombic benzamide) | Solid-State Phase Transition |

Methodologies for Investigating Crystallization Pathways

Advancing the understanding of metastable intermediates requires experimental and computational techniques capable of capturing transient structures and quantifying energy landscapes.

Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Cutting-edge microscopy techniques are at the forefront of directly observing nucleation events.

Protocol: In-Situ Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM) for Ice Nucleation [5]

- Objective: To directly map the microscopic crystallization pathways of ice I from nucleation to equilibrium states at molecular resolution.

- Materials: Translucent graphene substrates (as a heterogeneous nucleation surface), water vapor source, cryo-TEM holder.

- Procedure:

- A graphene substrate is loaded into a specialized in-situ cryo-TEM holder.

- The holder is cooled to a target temperature of 102 K.

- A water vapor is introduced into the system at a controlled pressure of 10⁻⁶ Pa.

- The deposition and crystallization process is recorded in real-time using the cryo-TEM, achieving millisecond temporal and picometer spatial resolution.

- Sequential TEM images and corresponding Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analyses are used to identify the structure (amorphous, Ice Ic, Ice Ih) and orientation of nascent nuclei.

- Key Measurements: Identification of amorphous adsorption layers, nucleation density, crystal structure and orientation of nuclei via FFT, temporal evolution of crystal size and habit, observation of ripening and coalescence events.

Protocol: Studying Phospholipid Influence on Cholesterol Crystallization [18]

- Objective: To determine the effects of specific phospholipid molecular species on early cholesterol crystallization and crystal habit transformation.

- Materials: Dilute (1.2 g/dl total lipid) bile salt-rich (97.5 mole %) model biles supersaturated with cholesterol; various lecithins (egg yolk, soy bean, single molecular species), sphingomyelins.

- Procedure:

- Model bile solutions are prepared with distinct phospholipid profiles.

- Solutions are incubated under controlled conditions to induce crystallization.

- Crystallization is monitored over time, noting the sequence of crystal habit appearance (filamentous, metastable intermediates, plates).

- Crystals are extracted at different time points, and their surface lipid composition is analyzed using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) after derivatization.

- The kinetics of transformation between different crystal habits are quantified.

The following workflow visualizes the key stages of the cryo-TEM protocol for investigating ice nucleation.

Computational and Molecular Simulation Approaches

Molecular simulations provide a complementary framework to compute free energies, kinetic barriers, and visualize mechanisms at the molecular level [17].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD tracks the motion of atoms and molecules over time, allowing direct observation of nucleation events. The use of efficient models like the monoatomic water (mW) model has been instrumental in simulating ice formation due to its ability to reproduce key thermodynamic properties with lower computational cost [5].

- Enhanced Sampling and Machine Learning: Advanced sampling techniques are required to overcome the high free energy barriers associated with nucleation. Machine learning is increasingly used to identify complex "collective variables" that accurately describe the progression of crystallization, including the formation of metastable intermediates [17]. Furthermore, machine-learned potentials are opening the door to high-accuracy free energy calculations for reliable ranking of polymorph stability [17].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Investigation |

|---|---|

| Translucent Graphene Substrates [5] | Provides a well-defined, atomically smooth surface for heterogeneous nucleation studies, allowing high-resolution TEM imaging. |

| Single Molecular Species Lecithins [18] | Used to systematically probe the specific influence of phospholipid acyl chain length and saturation on cholesterol crystallization pathways. |

| Bile Salt-Rich Model Bile [18] | A synthetically controlled solution that mimics the physiological environment for cholesterol crystallization, enabling the isolation of specific variables. |

| Cryo-TEM Holder with In-Situ Capabilities [5] | Enables the direct observation of dynamic crystallization processes under controlled temperature and pressure conditions within the microscope. |

| Coarse-Grained Water Models (e.g., mW) [5] | Computational models that simplify water molecules to a single particle, allowing for longer and larger-scale simulations of nucleation events. |

Implications for Pharmaceutical and Materials Science

The control and understanding of metastable intermediates are not merely academic pursuits; they have profound implications for technology and health.

In pharmaceutical development, different polymorphs of a drug substance can exhibit vastly different properties, including solubility, bioavailability, and physical stability. The inadvertent initial crystallization of a metastable polymorph, followed by a later transition to a more stable form, can compromise product shelf-life and efficacy. Understanding Ostwald's rule allows scientists to design crystallization processes (e.g., by manipulating solvent, temperature, or additives) to either bypass unwanted metastable forms or target a specific, desirable metastable polymorph with optimal properties [17]. The expansion into pharmaceutical co-crystals, composed of an active ingredient and an excipient, further amplifies the complexity and importance of controlling the crystallization landscape [17].

In materials science, the principles govern the synthesis of advanced materials. The formation of metastable intermediates is leveraged in creating materials with unique morphologies and properties. For example, the initial formation of metastable anatase TiO₂ is common before its transformation to stable rutile, a process critical for photocatalysis [16]. Similarly, understanding the amorphous precursors and metastable polymorphs in biomineralization processes, such as in seashells (calcium carbonate), informs the design of novel bio-inspired materials [17].

The journey from a disordered phase to a stable crystal is rarely direct. Ostwald's rule of stages provides a robust conceptual framework for understanding this journey as a progression through a series of metastable intermediates, each acting as a stepping-stone of increasing stability on a complex energy landscape. The investigation of these pathways, powered by advanced in-situ characterization techniques like cryo-TEM and sophisticated molecular simulations, has revealed ubiquitous non-classical nucleation mechanisms involving amorphous precursors, liquid-liquid separation, and competitive ripening.

For researchers focused on homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation energy barriers, the critical insight is that the initial barrier is often the one leading to the most kinetically accessible—not the most thermodynamically stable—state. Subsequent transformations are then governed by the relative barriers between these intermediate states. This nuanced understanding is pivotal for predicting and controlling crystallization outcomes across disciplines, from preventing pathological cholesterol gallstone formation to engineering the next generation of functional pharmaceuticals and advanced materials. The deliberate navigation of the energy landscape through metastable intermediates represents a fundamental shift from trial-and-error crystallization to its rational design.

Solid-state phase transformations are fundamental processes that govern the microstructure and resultant properties of metals and alloys. These transformations typically proceed through three overlapping kinetic mechanisms: nucleation, growth, and impingement [19]. Within this sequence, nucleation represents the critical initial step wherein stable particles of a new phase emerge from a parent matrix. The phenomenon of stepwise nucleation describes a pathway involving intermediate metastable states rather than a direct transition from parent to product phase, presenting significant implications for controlling material microstructure.

Research into homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation energy barriers provides the essential context for understanding stepwise nucleation mechanisms. Heterogeneous nucleation, which occurs at preferential sites such as surfaces, interfaces, or defects, dominates most practical solid-state transformations due to its lower energy barrier compared to homogeneous nucleation [20]. The stochastic nature of nucleation means that even in identical systems, nucleation events occur at different times, with the process rate being highly sensitive to system variables and impurities [20].

This case study examines the theoretical foundations, experimental evidence, and computational insights into stepwise nucleation pathways during solid-state phase transformations, with particular emphasis on the kinetic and thermodynamic factors that govern these processes.

Theoretical Framework

Classical Nucleation Theory and Beyond

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the fundamental framework for describing the initial formation of a new thermodynamic phase. CNT predicts that nucleation rate depends exponentially on the energy barrier ΔG*, which arises from the free energy penalty associated with creating the surface of a growing nucleus [20]. For homogeneous nucleation, the nucleus is approximated as a sphere, whereas heterogeneous nucleation involves reduced barrier due to the catalytic effect of surfaces.

The standard kinetic theory for solid-state phase transformations builds upon the Kolmogorov-Johnson-Mehl-Avrami (KJMA) equation, which describes the overall transformation kinetics under isothermal conditions [19]. However, classical models assume constant kinetic parameters, whereas in practice, these parameters often depend on time and temperature, necessitating more flexible modular analytical models [19].

Stepwise nucleation pathways challenge classical approaches by introducing intermediate stages with distinct energy landscapes. As described in research on amorphous alloys and Fe-based systems, the assumption of invariant thermodynamic states becomes invalid near equilibrium conditions, requiring coupling of chemical and mechanical driving forces for accurate kinetic descriptions [19].

Energy Landscape of Stepwise Nucleation

The concept of stepwise nucleation implies the existence of multiple energy barriers rather than a single activation energy. Experimental investigations of nanocrystalline materials reveal that phenomena such as chemical ordering in undercooled liquids prior to crystal nucleation can reduce the overall energy barrier [20].

In zirconium alloys undergoing α ⇌ β phase transformations, the kinetic path demonstrates complex temperature dependence that cannot be captured by simple CNT approaches. The transformation follows a first-order transition with latent heat approximately ΔH ≈ 4 kJ/mol, with kinetics strongly influenced by alloying elements and microstructure [21].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Solid-State Phase Transformation Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in Nucleation | Experimental Determination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avrami Exponent | n | Mechanism identification (nucleation & growth) | DSC, dilatometry [19] |

| Effective Activation Energy | Q | Overall energy barrier | Kissinger plot, isoconversion method [19] |

| Pre-exponential Factor | K₀ | Frequency factor for nucleation | Model fitting to experimental data [19] |

| Transformed Fraction | f | Progress of transformation | Dilatometry (DIL) [19] |

| Transformation Rate | df/dt, df/dT | Kinetic profile | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [19] |

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Characterization Techniques

Advanced characterization techniques provide direct experimental evidence for stepwise nucleation pathways. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and dilatometry (DIL) serve as primary methods for investigating solid-state phase transformation kinetics experimentally, providing direct information about transformation rate and transformed fraction [19].

For zirconium alloys, systematic studies of α/β phase transformation employ both DSC under quasi-equilibrium conditions (0.002-0.33 K/s) and dilatometric measurements at higher heating/cooling rates (10-100 K/s) [21]. The uncertainty in phase fraction measurement is typically ≤0.05, with temperature uncertainties around ±10 K [21].

Recent innovations in characterization focus on microscopic aspects of heterogeneous nucleation. As Winkler and Wagner describe, techniques for characterizing heterogeneous nucleation from the gas phase include approaches based on the Kelvin equation, cluster properties, microscopic contact angle, and line tension [22]. These methods enable quantification of the fundamental parameters governing nucleation energy barriers.

Novel Measurement Approaches

Cutting-edge techniques have enabled direct measurement of nucleation energy barriers at previously inaccessible scales. An optical apparatus combining optical tweezers for bubble generation and surface plasmon resonance microscopy (SPRM) demonstrated capability to quantify nucleation rate constants and activation energy barriers for single nanosized embryo vapor bubbles [11].

This approach achieved remarkable spatial resolution (~100 nm) and temporal resolution (1.5 ms), allowing mapping of local nucleation rates and revealing that facet structure and surface chemistry—rather than geometrical roughness—regulate the activation energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation [11]. The methodology involves:

- Localized Heating: A focused laser beam (1064 nm, 25.92 mW) heats a gold film with power density of 4.4×10⁷ mW/mm²

- SPRM Detection: A 680-nm detection beam monitors nucleation events via surface plasmon resonance changes

- Stochastic Analysis: Statistical analysis of nucleation induction times across hundreds of heating-cooling cycles

- Temperature Calibration: SPRM signals correlate with refractive index changes to determine local temperature

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Studying Nucleation Kinetics

| Technique | Application | Spatial/Temporal Resolution | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Crystallization kinetics, phase transitions | Bulk measurement, ~ms | Transformation enthalpy, rate (df/dT) [19] |

| Dilatometry (DIL) | Phase transformations in Fe-based alloys | Bulk measurement, ~ms | Transformed fraction (f) [19] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy (SPRM) | Nanobubble nucleation | 100 nm, 1.5 ms | Nucleation rate, local activation energy [11] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulation | Atomic-scale nucleation events | Atomic scale, fs-ps | Critical nucleus size, nucleation rate [10] |

| Resistivity Measurements | Phase boundaries in Zr alloys | Bulk measurement, varies | Transformation temperatures [21] |

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-scale insights into stepwise nucleation pathways that complement experimental observations. Simulations of Al-4at.%Cu alloy solidification using the Embedded Atom Method (EAM) potential reveal distinct nucleation modes dependent on undercooling [10].

At higher temperatures (0.6Tₘ and 0.54Tₘ), the system exhibits spontaneous nucleation with extended incubation periods, while lower temperatures (0.48Tₘ, 0.42Tₘ, 0.39Tₘ) trigger divergent nucleation characterized by rapid formation of numerous crystal nuclei [10]. The critical nucleation temperature for Al-Cu alloy is approximately 0.42Tₘ (where Tₘ is the melting point), determined by calculating nucleation rate and crystal nucleus density [10].

These simulations track the complete solidification process, including homogeneous nucleation, nucleus growth, grain coarsening, and microstructure evolution. The research identifies two growth mechanisms: absorption of smaller heterogeneous crystal nuclei by larger ones, and merging of adjacent crystal nuclei [10]. Microstructural analysis reveals long-period stacking structures composed of FCC and HCP arrangements within all nanocrystalline grains [10].

Kinetic Modeling of Complex Transformations

For engineering applications, modular analytical models with variable kinetic parameters offer improved description of real transformations. These models accommodate time-dependent Avrami exponents (n(t)) and activation energies (Q(t)), extending the concept of "iso-kinetics" to transformations where mechanisms evolve throughout the process [19].

In zirconium alloys, two model variants address phase transformation kinetics:

- Model A: Suitable for constant heating/cooling rates, with parameters explicitly dependent on q = dT/dt

- Model B: Generic formulation for implementation in fuel rod behavior programs for reactor accident scenarios [21]

These models successfully predict phase fractions during both heating and cooling cycles across rates up to 100 K/s, incorporating effects of excess oxygen and hydrogen concentration on transformation kinetics [21].

Diagram Title: Stepwise Nucleation Energy Pathway

Factors Influencing Nucleation Pathways

Material and Composition Effects

Alloy composition significantly impacts nucleation behavior through thermodynamic and kinetic pathways. In Zr-based alloys, excess oxygen and hydrogen concentration measurably influence phase transformation kinetics [21]. For Zircaloy-4, increasing hydrogen content from ~10 wppm to 970 wppm elevates both α/(α+β) and (α+β)/β transus temperatures [21].

Similar effects occur in Al-Cu alloys, where copper content affects nucleation kinetics and solidification microstructure. MD simulations demonstrate that the Al-4at.%Cu system forms nanocrystalline structures with specific FCC/HCP stacking sequences dependent on undercooling [10].

Interface Engineering and Impingement Effects

Modern research increasingly focuses on manipulating nucleation through interface engineering. Hydrogel coatings exemplify this approach, inhibiting heterogeneous nucleation by creating a substantial energy barrier at water-solid interfaces [23]. The mechanism involves:

- High Similarity to Water: Hydrogels contain >90% water, creating minimal interfacial energy difference

- Smooth Surface: Polymer networks provide exceptional surface smoothness

- High Fracture Energy: Polymer networks resist cavity formation

- Strong Adhesion: Covalent bonding to substrates prevents delamination

This approach raises the boiling temperature of water from 100°C to 108°C at atmospheric pressure and significantly reduces cavitation pressure on solid surfaces [23].

Beyond external interfaces, internal impingement effects strongly influence transformation kinetics. Recent modeling incorporates soft impingement (overlapping composition fields) and anisotropic growth, both of which substantially impact transformed fraction evolution and kinetic parameters [19].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleation Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide-based Hydrogel | Interface engineering for nucleation control | >90% water content, smooth surface, high adhesion | [23] |

| Zircaloy-4 | Zr-alloy phase transformation studies | 1.5%Sn, 0.15%Fe, 0.1%Cr, 0.12%O, α/β transformation | [21] |

| Zr1NbO Alloy | Nuclear material kinetics research | Zr1%Nb0.1%O, α/β transformation ~1040-1210K | [21] |

| Al-4at.%Cu Alloy | Solidification nucleation studies | Model system for MD simulations, EAM potential | [10] |

| Gold Film Substrate | Nanobubble nucleation measurements | 50nm thickness, SPRM compatibility | [11] |

Implications and Future Directions

Understanding stepwise nucleation pathways enables precise microstructure control across materials systems. In nuclear applications, accurate modeling of Zr-alloy phase transformations ensures fuel cladding integrity during potential accident scenarios [21]. For advanced manufacturing processes like laser cladding and additive manufacturing, controlling solidification nucleation leads to improved mechanical properties in Al-Cu alloys [10].

Future research directions include:

- Advanced Characterization: Developing techniques with combined atomic-scale and fast temporal resolution

- Multi-scale Modeling: Bridging MD simulations with mesoscale and continuum models

- Interface Design: Creating engineered surfaces and coatings with tailored nucleation properties

- Complex Alloy Systems: Extending fundamental principles to high-entropy alloys and complex concentrated alloys

The continued integration of computational prediction, experimental validation, and theoretical advancement will further illuminate the complex pathways of stepwise nucleation in solid-state transformations.

Diagram Title: Nucleation Research Methodology Framework

Probing Nucleation Barriers: Computational and Experimental Methodologies in Practice

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations for Studying Rare Nucleation Events

Nucleation, the initial process in first-order phase transitions, is fundamental to phenomena ranging from cloud formation and crystallization to protein aggregation in biological systems. The existence of an energy barrier that must be overcome to trigger new phase formation is a common feature of all nucleation phenomena. This nucleation barrier arises from the competition between the energetic cost of creating an interface and the thermodynamic driving force favoring the new phase. Understanding microscopic mechanisms governing nucleation is essential for predicting and controlling phase transitions in natural and engineered systems. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful tool for investigating these processes at atomic resolution, offering insights difficult to obtain through physical experimentation alone [24] [25].

The accurate evaluation of nucleation barriers remains challenging due to intrinsic features of nucleation phenomena. The formation of a critically sized cluster is stochastic and becomes increasingly rare as the barrier height grows. Even when such a cluster appears, it is inherently unstable because its size corresponds to the top of the free-energy barrier. Consequently, it does not persist long enough to reliably measure its properties [25]. This technical challenge has driven the development of specialized MD techniques that can overcome the timescale limitations of conventional simulations and efficiently sample these rare events.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Nucleation

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Free-energy REconstruction from Stable Clusters (FRESC)

The FRESC method is a novel simulation technique that evaluates the nucleation barrier by stabilizing small clusters in the NVT ensemble. Using thermodynamics of small systems, it converts properties of this stable cluster into the Gibbs free energy of formation of the critical cluster. This approach is straightforward to implement, computationally inexpensive, and requires only a small number of particles comparable to the critical cluster size. Notably, it does not rely on Classical Nucleation Theory, cluster definition, or reaction coordinates, opening possibilities for simulating nucleation processes in complex molecules of atmospheric, chemical, or pharmaceutical interest [26] [25].

Experimental Protocol: FRESC Implementation

- System Setup: Prepare a simulation box containing a supersaturated vapor phase. The system size should be sufficient to accommodate a cluster of interest while maintaining vapor phase around it.

- Cluster Stabilization: Perform NVT ensemble simulations to stabilize a small liquid cluster coexisting with its vapor. Appropriate temperature conditions are crucial for achieving stable clusters.

- Property Measurement: Extract thermodynamic properties from the stabilized cluster simulation, including pressure, chemical potential, and interface properties.

- Free Energy Conversion: Apply thermodynamics of small systems to convert measured properties into the Gibbs free energy of formation of the critical cluster using appropriate transformation equations.

- Validation: Compare results with established methods like Umbrella Sampling to verify accuracy, as demonstrated for condensation in Lennard-Jones truncated and shifted fluids [25].

Variational Umbrella Seeding