Navigating the Design Space and Activity Cliffs: AI-Driven Strategies for Modern Drug Discovery

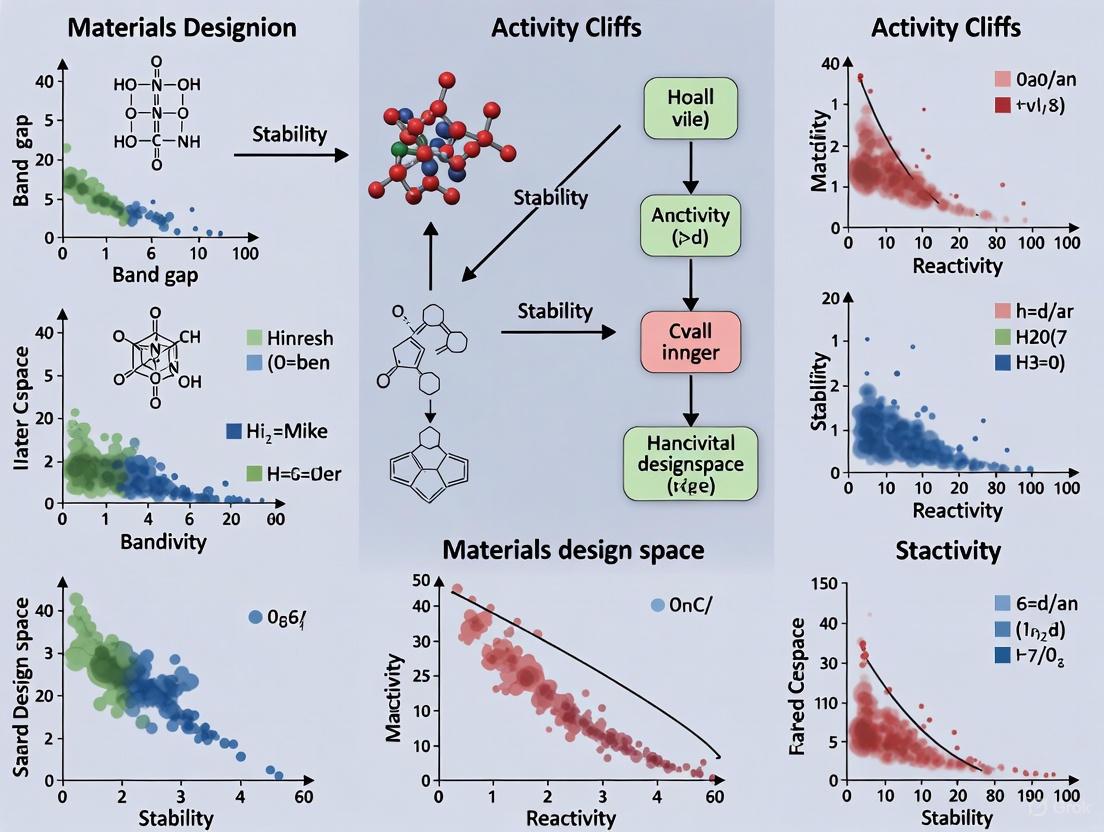

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical concepts of the materials design space and activity cliffs.

Navigating the Design Space and Activity Cliffs: AI-Driven Strategies for Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical concepts of the materials design space and activity cliffs. It explores the foundational principles of design space as a multidimensional region of assured quality and the challenges posed by activity cliffs, where minor structural changes cause significant potency shifts. The content covers the application of advanced AI and machine learning methodologies, including foundation models and reinforcement learning, for property prediction and de novo molecular design. It further addresses practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to improve workflow efficiency and discusses rigorous validation frameworks for comparing model performance. By synthesizing insights from current literature, this article aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to accelerate the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

Laying the Groundwork: Defining Design Space and the Activity Cliff Phenomenon

What is a Design Space? The ICH Q8 Framework and Its Role in Quality Assurance

In the pharmaceutical industry, a Design Space is a fundamental concept of the Quality by Design (QbD) approach outlined in the ICH Q8 (R2) guideline. It is defined as "the multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables (e.g., material attributes) and process parameters that have been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality" [1]. Working within the Design Space is not considered a change, while movement outside of it is considered a change and typically initiates a regulatory post-approval process [2]. For scientists and engineers, the Design Space represents a predictive relationship, often formalized as CQA = f(CMA, CPP) + E, where Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) are a function of Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs), with E representing a modeling error term [2]. This model provides a scientifically-established foundation for understanding process robustness, offering operational flexibility, and ensuring consistent product quality.

The ICH Q8 Framework and Regulatory Context

The ICH Q8 guideline, pertaining to Pharmaceutical Development, provides the core framework for Design Space. ICH Q8 promotes a systematic and proactive approach to development, emphasizing a deep understanding of the product and process based on sound science and quality risk management [3]. It is one part of a cohesive system of guidelines designed to ensure the highest standards of pharmaceutical quality and patient safety. The table below summarizes the role of key ICH guidelines that support the QbD ecosystem:

Table 1: Interconnected ICH Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Quality

| Guideline | Primary Focus | Role in the QbD System |

|---|---|---|

| ICH Q8 (R2) | Pharmaceutical Development | Provides the principles for defining the Design Space and establishing a systematic, science-based approach to product and process understanding [3]. |

| ICH Q9 | Quality Risk Management | Offers the tools for risk assessment, which are used to identify which material attributes and process parameters are critical and should be included in the Design Space [3]. |

| ICH Q10 | Pharmaceutical Quality System | Establishes the overall quality management system that governs the Design Space throughout the product lifecycle, including change management and continuous improvement [3]. |

| ICH Q7 | GMP for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients | Provides the foundational Good Manufacturing Practice requirements for API manufacturing, which the Design Space operates within [3]. |

Key Components and Methodologies for Design Space Characterization

Establishing a Design Space requires a meticulous, data-driven approach to understand the complex relationships between process inputs and quality outputs.

Input Variables and Output Responses

The development of a Design Space involves systematic experimentation and analysis of key variables:

- Input Variables: These include Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) selected through prior risk assessment and process development studies [1].

- Output Responses: The Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) are the measurable properties that define product quality [2].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

A range of advanced methodologies is employed to characterize the Design Space:

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Specific experimental designs, such as central composite design or Doehlert design, are implemented to efficiently explore the multifactor space and determine the relationship

f(·)[2]. - Response Surface Modeling: The function

f(·)is often represented by a response surface model, which provides a visual and mathematical representation of how inputs affect CQAs [2]. - Bayesian Approaches: Computational techniques use process models to determine a feasibility probability, providing a quantitative measure of reliability and risk within the Design Space [2].

- Metamodeling and Global Sensitivity Analysis (GSA): These techniques help reduce model complexity and computational time for identifying and quantifying a probability-based Design Space [2].

Table 2: Core Methodologies for Design Space Characterization

| Methodology | Key Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Design of Experiments (DoE) | Plans efficient and systematic experiments to study the effect of multiple variables and their interactions. | Exploring the effect of kiln temperature and mixing speed on the particle size distribution of a ceramic powder [2] [4]. |

| Response Surface Modeling | Creates a mathematical model and 3D surface to visualize the relationship between process inputs and quality outputs. | Modeling the combined impact of excipient concentration and compression force on tablet hardness and dissolution [2]. |

| Feasibility Probability Analysis | Calculates the probability that a set of input parameters will yield a product meeting all CQA specifications. | Determining the reliability of a crystallization process across different combinations of temperature and cooling rate [2]. |

Defining Design Space Boundaries

The boundaries of a Design Space are determined by both theoretical and practical considerations:

- Theoretical Considerations: Domain knowledge and scientific intuition define feasible and important input parameters, often translated into a set of rules [4].

- Practical Considerations: Real-world constraints, such as equipment capability (e.g., a kiln's maximum temperature), material costs, and customer requirements, set the practical limits of the Design Space [4].

Design Space in Practice: Experimental Protocols and Workflow

The process of defining and using a Design Space follows a logical sequence from risk assessment to regulatory submission and lifecycle management. The following workflow visualizes this journey and the role of key experiments.

Diagram 1: Design Space Development Workflow

Protocol for Design Space Definition via DoE and Modeling

This protocol details the core experimental and computational steps for establishing a Design Space, as shown in the workflow.

Step 1: Risk-Based Variable Selection

- Objective: Identify which material attributes and process parameters have a significant impact on CQAs.

- Procedure: Use risk assessment tools (e.g., FMEA) to screen variables. Only parameters with a potential critical impact are selected for inclusion in the Design Space studies [1].

- Rationale: Focusing on critical parameters ensures efficient use of resources and a more manageable experimental scope.

Step 2: Design of Experiments (DoE) Execution

- Objective: Generate high-quality data to model the relationship between inputs and outputs.

- Procedure:

- Select an appropriate experimental design (e.g., Central Composite Design for response surface modeling).

- Define the characterization range for each input variable, which should be wider than the expected operating range to probe the edges of failure [1].

- Execute the experiments in a randomized order to minimize the impact of confounding variables.

- Data Collection: For each experimental run, record all set input parameters (CPPs, CMAs) and the corresponding measured outputs (CQAs).

Step 3: Mathematical Model Building

- Objective: Develop a quantitative model (

CQA = f(CMA, CPP) + E) that predicts CQAs based on input variables. - Procedure: Employ statistical software to fit the experimental data to a model, typically starting with a second-order polynomial for response surface models. The model's statistical significance (e.g., p-value for terms, R²) is evaluated [2].

- Error Handling: The modeling error

Eis often assumed to be a random variable following a Gaussian distribution, which is considered in confidence interval calculations [2].

- Objective: Develop a quantitative model (

Step 4: Design Space Verification & Regulatory Submission

- Objective: Confirm the predictive accuracy of the model and submit the Design Space for regulatory approval.

- Procedure: Conduct verification runs at critical points within the proposed Design Space (e.g., near edges, center) to confirm that CQAs are met as predicted.

- Documentation: The rationale for the Design Space, including the experimental data, model, and verification results, is described in the regulatory submission [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Characterizing a Design Space requires specific materials and analytical techniques to generate high-fidelity data.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Design Space Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in Design Space Characterization |

|---|---|

| Scale-Independent Parameters | Parameters like shear rate (instead of agitation rate) or dissipation energy (instead of power/volume) are used to define a scale-independent Design Space, facilitating scale-up from lab to commercial production [2]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Tools such as in-line sensors (e.g., FBRM, IR, NIR) and real-time monitoring of temperature and torque provide rich, continuous data streams for understanding process dynamics and building better models [2]. |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | Software platforms (e.g., the Python package DEUS) are used to implement Bayesian approaches, feasibility calculations, and other complex algorithms for quantitative Design Space representation [2]. |

Connecting Design Space to Materials Informatics and Activity Cliffs

The concept of a design space extends beyond pharmaceutical process engineering into materials informatics and drug discovery, particularly in the study of Activity Cliffs (ACs).

In materials science, the design space is "the set of possible input parameters that are to be run through an AI model," such as composition and process conditions for a new material [4]. This space can be high-dimensional and is explored using smart algorithms to identify regions that yield target properties [4].

In drug discovery, an Activity Cliff is defined as a pair of structurally similar compounds active against the same target but with a large difference in potency [5]. These cliffs represent a steep "structure-activity relationship (SAR)" and highlight small chemical modifications that dramatically influence biological activity. The relationship between the chemical structure space and the biological activity landscape can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: Activity Cliffs in the Chemical Design Space

Experimental Protocols for Activity Cliff Research

The systematic study of Activity Cliffs involves specific computational protocols for their identification and analysis, which informs the broader chemical design space.

Protocol 1: Identifying Activity Cliffs using Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs)

- Objective: Systematically find pairs of structural analogs with large potency differences in a compound database.

- Procedure:

- MMP Generation: Use a molecular fragmentation algorithm to identify pairs of compounds that share a common core but differ by a substituent at a single site [6].

- Similarity Criterion: Apply constraints (e.g., maximum substituent size) to ensure the pairs represent meaningful, small modifications [6].

- Potency Difference Criterion: Calculate the potency difference (e.g., ∆pKi) for each MMP. An AC (or "MMP-cliff") is defined by a statistically significant, large potency difference, often derived from the activity class-specific distribution (e.g., mean + 2 standard deviations) [6].

- Advanced Analysis: ACs are rarely isolated pairs. Network analysis can reveal coordinated ACs formed by groups of analogs, providing richer SAR information [5].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Prediction of Activity Cliffs

- Objective: Build a classification model to distinguish ACs from non-ACs among compound pairs.

- Procedure:

- Molecular Representation: Represent each MMP using concatenated molecular fingerprints for the common core and the chemical transformation [6].

- Model Training: Train machine learning models (e.g., Support Vector Machines with specialized MMP kernels, Random Forests, Graph Neural Networks) on a labeled dataset of ACs and non-ACs [6].

- Data Leakage Prevention: Use advanced cross-validation (AXV) that separates compounds (not just pairs) into training and test sets to prevent overestimation of model performance [6].

- Application: Accurate prediction of ACs helps prioritize compounds for synthesis and reveals structural motifs critical for high potency early in the drug design process.

The Design Space, as defined by ICH Q8, is a powerful concept that shifts pharmaceutical quality assurance from a reactive, batch-centric control to a proactive, science-based understanding of product and process. It provides a structured framework for achieving operational flexibility while ensuring robust product quality. The principles of defining and exploring a multidimensional parameter space extend directly into adjacent fields like materials informatics and drug discovery, where understanding the relationship between inputs (e.g., chemical structure) and outputs (e.g., biological activity) is paramount. The study of Activity Cliffs provides a poignant example of how navigating this complex design space requires sophisticated tools and methodologies to uncover critical knowledge and drive efficient development.

In medicinal chemistry, the systematic study of how chemical structural changes affect biological activity is formalized through structure-activity relationships (SAR). These relationships serve as essential guides for optimizing compound properties during drug discovery campaigns. Within SAR landscapes, activity cliffs represent particularly valuable yet challenging phenomena. Activity cliffs are defined as pairs or groups of structurally similar compounds that nonetheless exhibit large differences in biological potency [7]. This paradoxical relationship, where minimal structural changes yield significant activity shifts, presents both exceptional opportunities and substantial challenges for drug discovery researchers. The duality of activity cliffs has been aptly characterized as a "Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde" relationship within drug discovery—they can provide crucial insights for lead optimization while simultaneously confounding predictive computational models [7].

The systematic identification and interpretation of activity cliffs enables medicinal chemists to make critical decisions about which compound series to pursue and what specific structural modifications to implement. However, the same cliffs that provide such valuable chemical insights often disrupt the smooth structure-activity landscapes assumed by many quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and machine learning algorithms [8] [7]. This whitepaper explores the nature of activity cliffs, their detection, their impact on drug discovery workflows, and emerging strategies to harness their potential while mitigating their disruptive effects.

Defining and Characterizing Activity Cliffs

Formal Definitions and Conceptual Framework

Activity cliffs are formally defined as pairs of compounds with high structural similarity but unexpectedly large differences in biological activity or potency [7]. This definition rests on two fundamental components: a similarity metric for quantifying structural resemblance, and a potency difference threshold for identifying "unexpected" changes. The conceptual framework for understanding activity cliffs emerges from the broader concept of activity landscapes, which represent the topographic relationship between chemical structure and biological activity across a compound series or dataset [9].

In practical terms, most activity cliff definitions rely on the activity landscape concept, where compound potency is represented as a third dimension superimposed on a two-dimensional projection of chemical space [7]. Within this three-dimensional landscape, smooth regions correspond to continuous SARs (where structural changes produce gradual activity changes), while rugged regions with sudden "cliffs" represent discontinuous SARs. The most informative activity cliffs typically occur between compounds that share a common core structure but differ at specific substitution sites, often identified through matched molecular pair (MMP) analysis [10] [8].

Quantitative Measures for Activity Cliff Identification

Several quantitative approaches have been developed to systematically identify and categorize activity cliffs:

Similarity-Based Approaches: These methods use molecular similarity metrics (such as Tanimoto similarity based on molecular fingerprints) combined with potency difference thresholds. A commonly used implementation is the Structure-Activity Landscape Index (SALI), which mathematically combines both structural similarity and potency difference into a single value [7].

Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) Approaches: MMPs are defined as pairs of compounds that differ only at a single site (a specific substructure) [10] [8]. When such minimal structural changes result in significant potency differences, they represent particularly informative activity cliffs. The SAR Matrix (SARM) methodology provides a systematic framework for identifying such relationships across large compound datasets [10].

Activity Cliff Index (ACI): Recent advances have introduced specialized indices specifically designed to quantify the intensity of SAR discontinuities. The ACI captures the relationship between structural similarity and biological activity differences, enabling systematic identification of compounds that exhibit activity cliff behavior [8].

Table 1: Quantitative Methods for Activity Cliff Identification

| Method | Basis | Key Metrics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Based | Molecular descriptors/fingerprints | Tanimoto similarity, potency difference | Initial cliff detection across diverse datasets |

| MMP-Based | Structural transformations | Single-site modifications, potency change | Detailed SAR analysis of specific compound series |

| SALI | Combined similarity/potency | SALI value = |Δactivity| / (1 - similarity) | Landscape visualization and cliff ranking |

| ACI | Machine learning optimization | Similarity-distance relationships | AI-driven molecular design |

Computational Methodologies for Activity Cliff Analysis

The SAR Matrix (SARM) Approach

The Structure-Activity Relationship Matrix (SARM) methodology represents a sophisticated computational approach specifically designed to extract, organize, and visualize compound series and associated SAR information from large chemical datasets [10]. This method employs a hierarchical two-step application of the matched molecular pair (MMP) formalism:

Compound MMP Generation: In the initial step, MMPs are generated from dataset compounds by systematically fragmenting molecules at exocyclic single bonds, resulting in core structures and substituents.

Core MMP Generation: The core fragments from the first step are again subjected to fragmentation, identifying all compound subsets with structurally analogous cores that differ only at a single site.

This dual fragmentation scheme identifies structurally analogous matching molecular series (A_MMS), with each series represented in an individual SARM [10]. The resulting matrices resemble standard R-group tables familiar to medicinal chemists but contain significantly more comprehensive structural and potency information. SARMs enable the detection of various SAR patterns, including preferred core structures, SAR transfer events between series, and regions of SAR continuity or discontinuity.

The Compound Optimization Monitor (COMO)

The Compound Optimization Monitor (COMO) approach represents another advanced computational methodology designed to support lead optimization by combining assessment of chemical saturation with SAR progression monitoring [11]. This method introduces the concept of chemical saturation to evaluate how thoroughly an analog series has explored its surrounding chemical space.

COMO operates through several key steps:

Virtual Analog Generation: For a given analog series, large populations of virtual analogs are generated by decorating substitution sites in the common core structure with substituents from comprehensive chemical libraries.

Chemical Neighborhood Definition: Distance-based chemical neighborhoods are established for each existing analog in a multidimensional chemical feature space.

Saturation Scoring: Global and local saturation scores quantify the extent of chemical space coverage by existing analogs, particularly focusing on optimization-relevant active compounds.

The combination of chemical saturation assessment with SAR progression monitoring provides a powerful diagnostic tool for lead optimization campaigns, helping researchers decide when sufficient compounds have been synthesized or when it might be time to discontinue work on a particular analog series [11].

Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning (ACARL)

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have led to the development of specialized computational frameworks that explicitly account for activity cliffs in de novo molecular design. The Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning (ACARL) framework introduces two key innovations [8]:

Activity Cliff Index (ACI): A quantitative metric for detecting activity cliffs within molecular datasets that captures the intensity of SAR discontinuities by comparing structural similarity with differences in biological activity.

Contrastive Loss in RL: A novel loss function within the reinforcement learning framework that actively prioritizes learning from activity cliff compounds, shifting the model's focus toward regions of high pharmacological significance.

This approach represents a significant departure from traditional molecular generation models, which often treat activity cliff compounds as statistical outliers rather than leveraging them as informative examples within the design process [8]. By explicitly modeling these critical SAR discontinuities, ACARL and similar frameworks demonstrate the potential to generate molecules with both high binding affinity and diverse structures that better align with complex SAR patterns observed in real-world drug targets.

Diagram 1: Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning (ACARL) Workflow. This AI-driven framework systematically identifies activity cliffs and incorporates them into the molecular generation process through a specialized contrastive loss function.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Systematic Activity Cliff Detection Protocol

A standardized protocol for systematic activity cliff detection involves the following methodological steps:

Data Curation: Collect and standardize compound structures and associated biological activity data (typically half-maximal inhibitory concentration [IC₅₀], inhibition constant [Kᵢ], or similar potency measures). The ChEMBL database serves as a valuable public resource containing millions of such activity records [8].

Structural Similarity Assessment: Calculate pairwise molecular similarities using appropriate descriptors. Common approaches include:

- Fingerprint-Based Similarity: Using structural fingerprints (such as ECFP4 or FCFP4) with Tanimoto similarity coefficients.

- Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs): Identifying pairs differing only at a single site through systematic fragmentation [10].

Potency Difference Calculation: Convert activity values to a logarithmic scale (pIC₅₀ or pKᵢ) and calculate absolute potency differences between compound pairs.

Cliff Identification: Apply selected criteria to identify activity cliffs:

- Similarity-Based: Thresholds such as Tanimoto similarity ≥0.85 and pIC₅₀ difference ≥2.0 log units.

- MMP-Based: Any MMP with significant potency difference (typically ≥2.0 log units) [8].

Validation and Contextualization: Examine identified cliffs in structural context to exclude potential artifacts and categorize cliffs by structural modification type.

SAR Progression Monitoring Protocol

Monitoring SAR progression within an evolving compound series involves tracking both chemical exploration and resulting activity trends:

Analog Series Definition: Identify compounds sharing a common core structure with variations at specific substitution sites.

Chemical Saturation Assessment:

- Generate virtual analogs by combining core structure with comprehensive substituent libraries.

- Project existing and virtual analogs into chemical descriptor space.

- Calculate chemical saturation scores based on neighborhood coverage [11].

SAR Progression Quantification:

- Track potency improvements over compound synthesis iterations.

- Monitor property changes relative to optimization goals.

- Calculate SAR progression scores based on activity distribution and cliff presence.

Series Characterization: Classify series development stage based on saturation and progression score combinations to inform resource allocation decisions [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Activity Cliff Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Activity Cliff Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Chemical Database | Curated bioactive molecules | Source of compound structures and activity data for cliff analysis |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Software Application | (Q)SAR technology implementation | Hazard assessment, chemical categorization, and SAR analysis [12] |

| Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) Algorithms | Computational Method | Systematic compound fragmentation | Identification of single-site modifications leading to activity cliffs [10] |

| SARM Software | Analytical Tool | SAR matrix generation and analysis | Extraction and organization of SAR information from large datasets [10] |

| 3D-Field QSAR | Modeling Approach | 3D-QSAR using field descriptors | Visualization of favorable/unfavorable molecular features for SAR interpretation [13] |

Impact on Drug Discovery and Optimization

Positive Implications for Medicinal Chemistry

Activity cliffs, despite their challenges, offer significant opportunities for medicinal chemistry:

SAR Interpretation: Activity cliffs provide exceptionally clear insights into critical structural determinants of biological activity. By highlighting specific modifications that dramatically alter potency, they reveal which molecular features most significantly impact target binding [7].

Lead Optimization Guidance: The systematic analysis of activity cliffs helps prioritize synthetic efforts toward modifications with the highest potential for potency improvements. This is particularly valuable in the context of multi-parameter optimization, where multiple properties must be balanced simultaneously [11] [9].

Scaffold Optimization: When activity cliffs occur between compounds with different core structures, they can inform scaffold hopping strategies—identifying alternative molecular frameworks that maintain or enhance desired activities while improving other properties [10].

Chemical Biology Insights: Beyond direct drug design applications, activity cliffs can reveal fundamental aspects of ligand-target interactions, potentially identifying key molecular recognition elements that govern binding affinity and selectivity.

Challenges for Predictive Modeling

The disruptive impact of activity cliffs on computational prediction methods represents a significant challenge:

QSAR Model Disruption: Traditional QSAR approaches generally assume smooth activity landscapes, where structurally similar compounds have similar activities. Activity cliffs violate this fundamental assumption, leading to substantial prediction errors for cliff compounds [7].

Machine Learning Limitations: Both traditional and modern machine learning methods (including deep learning approaches) struggle with activity cliff compounds. Studies demonstrate that neither increasing training set size nor model complexity reliably improves prediction accuracy for these challenging cases [8].

Similarity-Based Reasoning Failures: Methods based on chemical similarity searching often recommend structurally similar analogs as potential candidates, but this approach fails dramatically for activity cliffs, where the most similar compounds may have markedly different activities [7].

Benchmark Limitations: Commonly used benchmarks for molecular design often lack appropriate activity cliff representation, potentially leading to overoptimistic performance estimates for algorithms that would underperform in real-world discovery settings [8].

Emerging Strategies and Future Directions

Approaches to Mitigate Activity Cliff Challenges

Several strategies have emerged to address the challenges posed by activity cliffs:

Explicit Cliff Modeling: Rather than treating activity cliffs as outliers, newer approaches like ACARL explicitly identify and prioritize these compounds during model training, leveraging their informational value rather than suffering from their disruptive effects [8].

Applicability Domain Estimation: Improved methods for defining the domain of applicability for QSAR models help identify when predictions may be unreliable due to proximity to activity cliffs [9].

Consensus Modeling and Ensemble Methods: Combining predictions from multiple models with different strengths and limitations can sometimes mitigate the impact of activity cliffs, though fundamental limitations remain [7].

Structure-Based Augmentation: When structural information about the biological target is available, integrating docking scores or other structure-based approaches can complement ligand-based methods and improve predictions near activity cliffs [8].

Integration with Modern Drug Discovery Workflows

The most effective applications of activity cliff research involve integrating cliff awareness throughout the drug discovery process:

Early Triage of Compound Series: Chemical saturation and SAR progression analysis can help identify series with remaining optimization potential early in discovery campaigns, directing resources toward the most promising leads [11].

Target-Specific Method Selection: Understanding the prevalence and nature of activity cliffs for specific target classes can inform the selection of appropriate computational methods and expectations for model performance.

Automated Design with Cliff Awareness: Incorporating activity cliff detection directly into de novo design systems creates a feedback loop where SAR discontinuities actively inform subsequent compound generation [8].

Diagram 2: SAR Progression and Chemical Saturation Analysis. This conceptual framework helps categorize compound series based on their development stage and informs decisions about continuing or terminating optimization efforts.

Activity cliffs represent both significant challenges and valuable opportunities in drug discovery. Their dual nature as both "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" underscores the importance of developing sophisticated approaches that can leverage their informational value while mitigating their disruptive effects on predictive modeling. The continued development of computational methods specifically designed to address SAR discontinuities—such as the SARM methodology, COMO approach, and ACARL framework—promises to enhance our ability to navigate complex structure-activity landscapes effectively.

As drug discovery increasingly embraces AI-driven approaches, the explicit incorporation of activity cliff awareness into molecular design systems represents a crucial frontier. Rather than treating these discontinuities as problematic outliers, the field is moving toward recognizing them as exceptionally informative landmarks in chemical space that can guide optimization efforts toward more effective therapeutics. The integration of activity cliff analysis throughout the drug discovery workflow will continue to play a vital role in accelerating the identification and optimization of candidate compounds with improved efficacy and safety profiles.

In the realm of computational drug design and materials discovery, the similarity property principle is a foundational concept, positing that structurally similar compounds tend to exhibit similar biological properties [14] [15]. However, activity cliffs (ACs) present a significant challenge to this principle. Defined as pairs or groups of structurally similar compounds that display a large and unexpected difference in biological potency against the same target, activity cliffs create abrupt discontinuities in the structure-activity landscape [14] [15]. From a materials design perspective, these phenomena represent critical inflection points where minute structural changes lead to dramatic functional consequences, thereby complicating predictive modeling and optimization efforts [16].

The seminal work of Maggiora first articulated the landscape view of structure-activity relationship (SAR) data, conceptualizing chemical structure and biological activity in a three-dimensional representation where the X-Y plane corresponds to chemical structure and the Z-axis represents activity [15]. Within this landscape, smoothly rolling surfaces indicate regions where the similarity property principle holds, while sharp peaks or gorges represent activity cliffs, signifying SAR discontinuities [15]. This dual character of activity cliffs makes them both problematic and invaluable: they challenge the predictive accuracy of computational models like quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) and machine learning, yet they encode high information content for guiding compound optimization by revealing critical structural modifications that significantly impact potency [14] [16].

Quantifying and Characterizing Activity Cliffs

Fundamental Metrics and Definitions

The accurate identification of activity cliffs requires robust quantitative definitions that establish thresholds for both structural similarity and potency difference. While early studies often applied a general 100-fold potency difference as an AC criterion, recent research has refined this approach using statistically significant, activity class-dependent potency differences derived from class-specific compound potency distributions [6]. For antimicrobial peptides, the AMPCliff framework defines ACs using a normalized BLOSUM62 similarity score threshold of ≥0.9 between aligned peptide pairs coupled with at least a two-fold change in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [17].

Several quantitative indices have been developed to characterize activity cliffs:

Structure-Activity Landscape Index (SALI): This pairwise measure calculates the ratio of potency difference to structural dissimilarity: SALI(i,j) = |Ai - Aj| / (1 - sim(i,j)), where Ai and Aj represent the activities of compounds i and j, and sim(i,j) is their structural similarity [15]. Larger SALI values indicate more pronounced activity cliffs.

Extended SALI (eSALI): To address computational limitations of pairwise comparisons in large datasets, eSALI provides a scalable alternative that quantifies the roughness of the activity landscape for an entire set with O(N) scaling: eSALI = 1/(N(1-se)) × Σ|Pi - P̄|, where se is the extended similarity of the set, Pi is the property of molecule i, and P̄ is the average property [18].

Structure-Activity Relationship Index (SARI): This metric evaluates both continuous and discontinuous SAR trends by combining a potency-weighted mean similarity (continuity score) with the product of average potency difference and pairwise ligand similarities (discontinuity score) [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Indices for Activity Cliff Characterization

| Index | Formula | Application Scope | Key Advantage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SALI | Ai - Aj | / (1 - sim(i,j)) | Pairwise compound comparison | Intuitive interpretation of individual cliffs | |

| eSALI | [1/(N(1-s_e))] × Σ | P_i - P̄ | Entire compound sets | O(N) scaling for large datasets | |

| SARI | ½(scorecont + (1 - scoredisc)) | Target-specific compound groups | Identifies continuous and discontinuous SAR trends | ||

| AMPCliff | BLOSUM62 ≥0.9 + ≥2× MIC change | Antimicrobial peptides | Domain-specific definition for peptides |

Prevalence and Impact of Activity Cliffs

Large-scale analyses across diverse compound classes reveal that activity cliffs are widespread phenomena with significant implications for predictive modeling. A comprehensive study spanning 100 activity classes from ChEMBL demonstrated that AC prevalence varies substantially across targets, with certain protein families exhibiting higher densities of cliff-forming compounds [6]. In antimicrobial peptides, systematic screening has revealed a significant prevalence of ACs, challenging the assumption that the similarity property principle uniformly applies to pharmaceutical peptides composed of canonical amino acids [17].

The impact of activity cliffs on machine learning models is profound and multifaceted. Traditional QSAR models and modern deep learning approaches both struggle with regions of the chemical space containing activity cliffs, often exhibiting poor extrapolation performance when structural nuances lead to dramatic potency changes [18] [19]. This vulnerability stems from the fundamental challenge that activity cliffs create discontinuities in the structure-activity function that statistical models must learn, violating the smoothness assumptions underlying many algorithmic approaches [15].

Computational Methodologies for Activity Cliff Analysis

Efficient Identification Algorithms

Conventional pairwise approaches for activity cliff identification scale quadratically (O(N²)) with dataset size, becoming computationally prohibitive for large compound libraries [14]. To address this challenge, novel algorithms have been developed:

BitBIRCH Clustering: This approach leverages the BitBIRCH clustering algorithm to group structurally similar compounds, then performs exhaustive pairwise analysis only within each cluster [14]. This strategy transforms the global O(N²) problem into multiple local searches with improved O(N) + O(N²max) scaling, where Nmax is the size of the largest cluster. The method can be enhanced through iterative refinement and similarity threshold offsets to achieve >95% accuracy in AC retrieval across diverse fingerprint representations [14].

Extended Similarity Framework: The eSIM framework facilitates linear scaling similarity assessment through column-wise summation of molecular fingerprints [18]. This approach classifies molecular features into similarity or dissimilarity counters based on established coincidence thresholds, enabling rapid quantification of structural variance across entire compound sets without exhaustive pairwise comparisons [18].

Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs): The MMP formalism provides an intuitive representation of structurally analogous compounds, defined as pairs sharing a common core structure with substituent variations at a single site [6]. MMP-based ACs (MMP-cliffs) capture small chemical modifications with large consequences for specific biological activities, making them particularly relevant for medicinal chemistry applications [6].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Efficient Activity Cliff Identification. The process begins with structural clustering using BitBIRCH, followed by localized pairwise analysis within clusters to identify activity cliffs while avoiding O(N²) computational complexity.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning have introduced diverse methodologies for activity cliff prediction:

Traditional Machine Learning: Large-scale benchmarking across 100 activity classes has revealed that support vector machines (SVM) with specialized MMP kernels achieve competitive performance in AC prediction, with accuracy often exceeding 80-90% [6]. Simpler approaches including random forests, decision trees, and nearest neighbor classifiers also demonstrate robust performance, with the surprising finding that prediction accuracy does not necessarily scale with methodological complexity [6].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Traditional GNN architectures face challenges with activity cliffs due to representation collapse—the tendency for similar molecular structures to converge in feature space, making it difficult to distinguish cliff pairs [19]. As molecular similarity increases, the distance in GNN feature spaces decreases rapidly, limiting their discriminative capacity for subtle structural variations with significant activity consequences [19].

Image-Based Deep Learning: The MaskMol framework represents an innovative approach that transforms molecular structures into images and employs vision transformers with knowledge-guided pixel masking [19]. This method leverages convolutional neural networks' sensitivity to local features, effectively amplifying differences between structurally similar molecules. MaskMol incorporates multi-level molecular knowledge through atomic, bond, and motif-level masking tasks, achieving significant performance improvements (up to 22.4% RMSE improvement) over graph-based methods on activity cliff estimation benchmarks [19].

Self-Conformation-Aware Graph Transformer (SCAGE): This architecture integrates 2D and 3D structural information through a multitask pretraining framework incorporating molecular fingerprint prediction, functional group annotation, atomic distance prediction, and bond angle prediction [20]. By learning comprehensive conformation-aware molecular representations, SCAGE achieves significant performance improvements across 30 structure-activity cliff benchmarks [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods for Activity Cliff Prediction

| Method Category | Representative Approaches | Key Strengths | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficient Clustering | BitBIRCH with local pairwise | Scalable to large libraries; >95% AC retrieval | 80-95% accuracy with iterative refinement [14] |

| Traditional ML | SVM with MMP kernels, Random Forest | Interpretable; handles diverse representations | 80-90% AUC across 100 activity classes [6] |

| Graph Neural Networks | GCN, GAT, MPNN | Direct structure learning; end-to-end training | Limited by representation collapse on similar pairs [19] |

| Image-Based DL | MaskMol, ImageMol | Amplifies subtle structural differences | 11.4% overall RMSE improvement on ACE benchmarks [19] |

| Multimodal DL | SCAGE, Uni-Mol | Integrates 2D/3D structural information | State-of-the-art on 30 SAC benchmarks [20] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Handling

Data Splitting Strategies for Robust Model Evaluation

The presence of activity cliffs in datasets necessitates careful data splitting strategies to avoid overoptimistic performance estimates and ensure model generalizability:

Activity Cliff-Aware Splitting: Conventional random splitting can lead to data leakage when activity cliff pairs are divided between training and test sets, artificially inflating performance metrics [6]. Advanced cross-validation (AXV) approaches address this by first holding out 20% of compounds, then assigning MMPs to training sets only if neither compound is in the hold-out set, and to test sets only if both compounds are in the hold-out set [6].

Stratified AC Distribution: For liquid crystal monomers binding to nuclear hormone receptors, studies have demonstrated that stratified splitting of activity cliffs into both training and test sets enhances model learning and generalization compared to assigning them exclusively to one set [21]. This approach ensures models encounter AC patterns during training while maintaining realistic evaluation conditions.

Scaffold-Based Splitting: Particularly challenging but practical evaluation scenarios involve scaffold-based splits, where test molecules are structurally distinct from training compounds [19] [20]. This approach provides a rigorous assessment of model generalizability across different regions of chemical space, though performance typically decreases compared to random splits due to the extrapolation required [19].

Benchmark Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

Standardized benchmarks have been developed to facilitate rigorous comparison of activity cliff prediction methods:

MoleculeACE: This activity cliff estimation benchmark incorporates 30 datasets from ChEMBL corresponding to different macromolecular targets, encompassing diverse chemical and biological activities [14] [19]. The platform provides predefined training/test splits and evaluation protocols specifically designed for assessing performance on activity cliffs [19].

AMPCliff: Specifically designed for antimicrobial peptides, this benchmark establishes a quantitative AC definition for peptides and provides a curated dataset of paired AMPs with associated minimum inhibitory concentration values [17]. The framework includes AC-aware data splitting and appropriate evaluation metrics for the peptide domain [17].

Evaluation Metrics: Beyond standard regression (RMSE, MAE) and classification (AUC, accuracy) metrics, activity cliff prediction requires specialized evaluation approaches. The roughness index (ROGI) quantifies the roughness of activity landscapes by monitoring loss in dispersion when clustering with increasing thresholds, correlating with ML model error [18].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Activity Cliff Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in AC Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| BitBIRCH | Clustering Algorithm | Efficient clustering of ultra-large molecular libraries | Identifies structurally similar compound groups for localized AC analysis [14] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Molecular fingerprint generation & manipulation | Computes ECFP, MACCS, and RDKIT fingerprints for similarity assessment [14] [18] |

| MoleculeACE | Benchmark Platform | Standardized evaluation of AC prediction methods | Provides 30 curated datasets with AC-aware splitting protocols [14] [19] |

| MaskMol | Deep Learning Framework | Molecular image pre-training with pixel masking | Enhances AC prediction through vision-based representation learning [19] |

| SCAGE | Graph Transformer | Molecular property prediction with conformation awareness | Integrates 2D/3D structural information to improve AC generalization [20] |

| ESM2 | Protein Language Model | Protein sequence representation learning | Predicts ACs in antimicrobial peptides through sequence embeddings [17] |

Visualization and Interpretation of Activity Landscapes

Activity Landscape Models

Activity landscape models provide intuitive visualization frameworks for interpreting structure-activity relationships:

Structure-Activity Similarity (SAS) Maps: These 2D plots depict molecular similarity against activity similarity, divided into four quadrants representing different SAR characteristics [15]. The upper-right quadrant (high structural similarity, large activity difference) contains activity cliffs, while the lower-right quadrant (high structural similarity, small activity difference) represents smooth SAR regions [15].

3D Activity Landscapes: These models combine a 2D projection of chemical space with compound potency values interpolated into a continuous surface [22]. The resulting topography reveals SAR patterns through its topology: smooth regions indicate SAR continuity, while rugged regions containing peaks and valleys correspond to SAR discontinuity and activity cliffs [22].

SALI Networks: Derived from thresholded SALI matrices, these network representations connect compounds forming significant activity cliffs [15]. Interactive implementations allow dynamic threshold adjustment, enabling researchers to focus on the most prominent cliffs or explore the full complexity of SAR discontinuities [15].

Quantitative Landscape Comparison

Going beyond qualitative visualization, image-based analysis enables quantitative comparison of activity landscapes:

Heatmap Grid Analysis: Converting 3D activity landscapes into top-down heatmap views enables pixel-intensity-based quantification of topological features [22]. By mapping heatmaps to standardized grids and categorizing cells based on color intensity thresholds, researchers can compute similarity scores between different activity landscapes [22].

Convolutional Neural Network Features: Deep learning approaches can extract informative features from activity landscape images, enabling machine learning classification of landscape types and quantitative comparison of SAR information content across different datasets [22].

Diagram 2: Activity Landscape Visualization Workflow. The process transforms structural and activity data into interpretable 3D landscapes and derived analytical representations (heatmaps, SALI matrices) to identify SAR patterns and activity cliffs.

Activity cliffs represent critical challenge points in materials design space that defy conventional similarity-based prediction paradigms. While they complicate computational modeling efforts, their strategic importance in understanding structure-activity relationships cannot be overstated. The continued development of specialized algorithms—from efficient clustering approaches to sophisticated deep learning architectures—is progressively enhancing our ability to identify, predict, and interpret these phenomena.

Future research directions likely include greater integration of 3D structural and conformational information, development of cross-modal foundation models that simultaneously leverage sequence, graph, and image representations of molecules, and the creation of increasingly sophisticated benchmarking frameworks that reflect real-world discovery scenarios. Furthermore, as the field advances, we anticipate growing emphasis on interpretable AI approaches that not only predict activity cliffs but also provide mechanistic insights into the structural and electronic features that give rise to these dramatic potency changes.

As Maggiora's original landscape conceptualization continues to evolve, the research community is building increasingly sophisticated quantitative frameworks for navigating the complex topography of chemical space. By directly addressing the challenges posed by activity cliffs, computational methods are transforming these apparent obstacles into valuable guidance for rational design across drug discovery and materials science.

In the fields of drug discovery and materials science, large-scale chemical databases have become indispensable infrastructure, serving as the foundational bedrock upon which research and development are built. These repositories, including flagship resources like ChEMBL and PubChem, provide systematically organized chemical and biological data that enable scientists to navigate the vast molecular space, understand structure-activity relationships (SARs), and identify critical patterns such as activity cliffs—pairs of structurally similar compounds with large differences in potency that are focal points for SAR analysis [23] [5]. The sheer scale of available chemical information necessitates robust databases; for example, as of 2013, ChEMBL contained over 1.25 million distinct compound records, while PubChem aggregates data from multiple sources including ChEMBL, DrugBank, and the Therapeutic Target Database (TTD), creating an extensive network of chemical information [24]. These resources transform raw data into actionable knowledge, powering machine learning algorithms and chemoinformatic analyses that accelerate the identification of promising compounds and materials. This technical guide explores the composition, application, and experimental protocols associated with these databases, with a specific focus on their pivotal role in activity cliff research and materials design space exploration.

Database Landscape: A Comparative Analysis of Major Chemical Repositories

The ecosystem of chemical databases comprises both public repositories and commercial resources, each with distinct strategic purposes, data profiles, and access models. Public databases like PubChem and ChEMBL form the cornerstone of open science, aggregating chemical and biological data from scientific literature, patent offices, and large-scale government screening programs [25]. These resources provide free access to vast amounts of curated data, making them indispensable starting points for academic and industrial research initiatives. ChEMBL specializes in manually curating bioactive molecules with drug-like properties from medicinal chemistry literature, incorporating high-confidence activity data (e.g., Ki, IC50, Kd) and explicitly mapped relationships between compounds and protein targets [24]. In contrast, PubChem operates as a comprehensive public resource containing information on biological activities of small molecules, integrating data from hundreds of sources including high-throughput screening assays and other molecular repositories [26] [24].

Specialized databases complement these general resources by focusing on specific domains or data types. The Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) provides detailed information about small molecule metabolites found in the human body, while the Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) offers information on known therapeutic protein and nucleic acid targets, targeted disease, pathway information, and corresponding drugs [24]. DrugBank uniquely blends detailed drug data with comprehensive drug target information, making it particularly valuable for drug discovery and repositioning studies [24]. Commercial databases typically offer enhanced curation, specialized analytics, and integration with proprietary tools, often available through licensing models that provide additional value through data quality assurance and advanced computational access.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Chemical Databases

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Content | Unique Features | 2013 Structure Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Bioactive drug-like molecules | 1.25M+ compounds; 9.5K+ targets; 10.5M+ activities | Manually curated SAR from literature; Confidence-scored targets | 1,251,913 |

| PubChem | Comprehensive chemical information | 100M+ compounds; 1M+ bioassays | Aggregates multiple sources; Confirmatory bioassays | N/A |

| DrugBank | Drug and target data | 6,516 compounds; 4,233 protein IDs | Drug-mechanism data; FDA approval status | 6,516 |

| HMDB | Human metabolites | 40,409 metabolites; 5,650 protein IDs | Metabolic pathways; Reference concentrations | 40,209 |

| TTD | Therapeutic targets & drugs | 15,009 compounds; 2,025 targets | Development stage indexing | 15,009 |

The strategic selection and combination of these databases enable researchers to address specific questions throughout the drug discovery pipeline. During target identification and validation, databases with comprehensive target information like ChEMBL and DrugBank are essential. For lead optimization and SAR studies, the high-quality potency data in ChEMBL becomes particularly valuable, especially when analyzing activity landscapes and cliffs [6] [23]. The integration of these diverse data sources creates a powerful ecosystem for chemical research, with each database contributing unique elements that collectively enable a more comprehensive understanding of the chemical-biological interface.

Chemical Data in Action: Illuminating Activity Cliffs

Defining and Classifying Activity Cliffs

Activity cliffs (ACs) represent a critical concept in structure-activity relationship analysis, traditionally defined as pairs of structurally similar compounds that are active against the same target but exhibit large differences in potency [23] [5]. These molecular pairings encapsulate extreme SAR discontinuity where minimal structural modifications result in dramatic changes in biological activity, making them highly informative for compound optimization. The accurate identification and analysis of ACs depend on two fundamental criteria: a structural similarity criterion specifying how molecular resemblance is assessed, and a potency difference criterion defining what constitutes a significant activity change [23]. While early AC assessments typically relied on Tanimoto similarity calculations using molecular fingerprints like ECFP4 or MACCS keys, more recent approaches have adopted matched molecular pairs (MMPs) as a more chemically intuitive similarity criterion [6] [23]. An MMP defines a pair of compounds that share a core structure and differ only at a single site through the exchange of substituents, creating a straightforward and interpretable similarity relationship [6].

The potency difference criterion for AC definition has evolved from a fixed threshold (traditionally a 100-fold difference) to more sophisticated, statistically-driven approaches. Recent large-scale analyses have adopted activity class-dependent potency difference criteria derived from class-specific compound potency distributions, where statistically significant potency differences are determined as the mean compound potency per class plus two standard deviations [6]. This approach acknowledges that what constitutes a meaningful potency difference may vary across different target families and compound classes. When confirmed inactive compounds are included in the analysis, the activity cliff concept can be extended to heterogeneous pairs comprising both active and inactive compounds, which significantly increases the frequency of cliff identification and provides additional SAR insights [26].

Table 2: Activity Cliff Classification and Characteristics

| Cliff Type | Similarity Criterion | Potency Relationship | SAR Information Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional AC | High fingerprint similarity (e.g., ECFP4 Tc >0.56) | Both compounds active with ≥100-fold potency difference | High - identifies critical modifications |

| MMP-Cliff | Matched molecular pair (single substitution site) | Large potency difference between structural analogs | High - chemically interpretable |

| 3D-Cliff | Similar binding modes (3D alignment) | Large potency difference despite similar binding | High - structural rationale often available |

| Scaffold Hop | Different core structures | Similar potency against same target | High - identifies novel chemotypes |

| Heterogeneous Cliff | Structural similarity | Active compound paired with confirmed inactive | Medium - identifies critical features for activity |

Systematic Identification and Analysis of Activity Cliffs

The systematic identification of activity cliffs requires specialized computational approaches that can efficiently process large chemical datasets. The standard methodology begins with the extraction of compound activity classes from databases like ChEMBL, typically applying stringent data quality filters such as molecular mass limits, high-confidence target annotations, and the use of specific potency measurements (Ki or Kd values) to ensure data reliability [6]. For each qualifying activity class, matched molecular pairs (MMPs) are generated using molecular fragmentation algorithms, with typical parameters limiting substituents to a maximum of 13 non-hydrogen atoms and requiring the core structure to be at least twice as large as the substituents [6].

The resulting MMPs are then classified as MMP-cliffs or non-cliffs based on the applied potency difference criterion. In recent large-scale analyses, only MMPs with a less than tenfold difference in potency (∆pKi < 1) are classified as nonACs, while those exceeding the class-dependent threshold are designated as activity cliffs [6]. This systematic approach has revealed that activity cliffs are rarely formed by isolated pairs of compounds; instead, most ACs (>90%) occur within networks of structural analogs with varying potency, forming coordinated activity cliffs that reveal more extensive SAR information than isolated pairs [5]. These networks can be represented as AC network diagrams where nodes represent compounds and edges represent pairwise AC relationships, often revealing densely connected hubs or "AC generators" – compounds that form activity cliffs with high frequency [5].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Large-Scale Activity Cliff Analysis

Protocol 1: Systematic Activity Cliff Identification

Objective: To systematically identify and categorize activity cliffs across multiple compound activity classes using data from ChEMBL.

Materials and Reagents:

- ChEMBL Database (Version 29 or newer): Primary source of compound structures and activity data [6].

- Molecular Fragmentation Algorithm: For generating matched molecular pairs (e.g., Hussain and Rea algorithm) [6].

- Fingerprint Generation Tool: RDKit or similar cheminformatics toolkit for calculating ECFP4 fingerprints [6].

- Computational Environment: Python/R programming environment with chemoinformatics libraries (e.g., RDKit, CDK).

Methodology:

- Data Extraction and Curation:

- Query ChEMBL for compounds meeting specific criteria: molecular mass <1000 Da, target confidence score of 9, interaction type 'D', and numerically specified Ki or Kd values [6].

- Apply additional filters to ensure data quality: exclude compounds with conflicting activity annotations, calculate average potency for compounds with multiple measurements within one order of magnitude.

Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) Generation:

- Apply molecular fragmentation algorithm to identify MMPs within each activity class.

- Use standard parameters: maximum substituent size of 13 non-hydrogen atoms, core structure at least twice as large as substituents, maximum difference of 8 non-hydrogen atoms between exchanged substituents [6].

- Discard MMPs with cores containing fewer than 10 non-hydrogen atoms.

Activity Cliff Classification:

- Calculate potency difference threshold for each activity class as mean pKi plus two standard deviations [6].

- Classify MMPs as activity cliffs if their potency difference exceeds the class-specific threshold.

- Classify MMPs with ∆pKi < 1 as nonACs.

Data Analysis and Visualization:

- Construct activity cliff networks with compounds as nodes and pairwise AC relationships as edges.

- Identify AC generators (highly connected nodes) and analyze their structural features.

- Calculate network metrics to characterize coordinated AC formation.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Prediction of Activity Cliffs

Objective: To develop machine learning models for predicting activity cliffs using molecular representation and classification algorithms.

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound Data Set: Pre-processed MMPs with activity cliff annotations from Protocol 1.

- Molecular Descriptors: ECFP4 fingerprints or alternative representations (Morgan fingerprints, CDDD, RoBERTa embeddings) [6] [27].

- Machine Learning Algorithms: CatBoost, Support Vector Machines, Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks [6] [27].

- Validation Framework: Conformal prediction framework for model calibration and evaluation [27].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation and Feature Engineering:

- Represent each MMP using concatenated fingerprints encoding core structure, unique features of exchanged substituents, and common features of substituents [6].

- Address compound overlap in MMPs by implementing advanced cross-validation (AXV) that ensures no shared compounds between training and test sets [6].

Model Training and Optimization:

- Train multiple classifier types (CatBoost, SVM, RF, DNN) using increasingly complex architectures.

- For deep learning approaches, implement graph neural networks or convolutional neural networks using MMP images as input [6].

- Optimize hyperparameters through cross-validation for each activity class.

Model Evaluation and Validation:

- Apply conformal prediction framework with Mondrian binning to ensure validity for both majority and minority classes [27].

- Evaluate models using sensitivity, precision, efficiency, and prediction error rate metrics.

- Assess model performance across 100 activity classes to determine generalizability [6].

Experimental Validation:

- Select top predictions for biological testing against target proteins.

- Determine experimental potency values using standardized assay protocols.

- Compare predicted versus experimental activity cliffs to validate model accuracy.

Effective utilization of chemical databases for activity cliff research requires a suite of specialized tools and resources that enable data access, processing, analysis, and visualization. The following table summarizes key solutions available to researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Database Mining and Activity Cliff Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application in AC Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Chemical informatics and machine learning | MMP generation, fingerprint calculation, descriptor computation |

| CatBoost | Machine Learning Library | Gradient boosting on decision trees | AC prediction with optimal speed-accuracy balance [27] |

| Datagrok | Analytical Platform | Interactive chemical data exploration | Chemical space visualization, SAR analysis, dataset curation [28] |

| CDD Vault | Data Management | Compound registration and assay data management | Secure storage and analysis of proprietary SAR data [28] |

| Conformal Prediction | Statistical Framework | Model calibration with confidence levels | Reliable AC prediction with controlled error rates [27] |

| ChEMBL Web Interface | Database Portal | Direct database query and compound retrieval | Extraction of high-confidence activity data for AC analysis [29] |

| PubChem Power User Gateway | Programmatic Access | Automated querying and data download | Large-scale compound data acquisition for benchmarking |

| NGL Viewer | Visualization Tool | 3D structure and interaction visualization | Analysis of 3D-cliffs and binding mode differences [28] |

These tools collectively enable the end-to-end processing of chemical data from initial extraction through to advanced analysis and visualization. Platforms like Datagrok provide integrated environments that support the entire analytical workflow, including built-in connectors to multiple data sources, automatic structure detection, chemically-aware data viewers, and interactive chemical space visualization capabilities [28]. For machine learning-guided approaches, the combination of CatBoost classifiers with conformal prediction has demonstrated particular effectiveness, achieving substantial reductions in computational requirements for virtual screening while maintaining high sensitivity in identifying top-scoring compounds [27].

Large-scale chemical databases like ChEMBL and PubChem have fundamentally transformed the practice of chemical research and drug discovery by providing comprehensive, well-organized data resources that serve as the foundation for understanding the materials design space. The systematic analysis of activity cliffs exemplifies how these databases enable the extraction of critical SAR insights from large chemical datasets, revealing the subtle relationships between molecular structure and biological activity that drive compound optimization. As these databases continue to grow and evolve, and as new computational approaches like machine learning and conformal prediction become increasingly sophisticated, the research community's ability to navigate chemical space and identify meaningful patterns will continue to accelerate. The integration of robust experimental protocols with powerful analytical tools creates a virtuous cycle of knowledge generation that promises to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of drug discovery and materials science in the years to come.

AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Modeling and Molecular Design

Leveraging Foundation Models for Materials Property Prediction and Inverse Design

The discovery and development of new materials have long been characterized by painstaking experimental effort and computationally intensive simulations. However, a transformative shift is underway, propelled by the emergence of foundation models—large-scale machine learning models pre-trained on extensive datasets that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks [16]. In materials science, these models are demonstrating remarkable capabilities in property prediction and inverse design, the process of designing materials with predefined target properties [30]. This paradigm is particularly crucial for navigating the complex "materials design space," where subtle structural changes can lead to dramatic property shifts—a phenomenon known as activity cliffs [16] [8].

Activity cliffs, defined as pairs or groups of structurally similar compounds that exhibit unexpectedly large differences in biological activity or material properties, represent both a challenge and an opportunity [14] [8]. They defy the traditional similarity-property principle, which posits that structurally similar molecules should have similar properties, and they frequently cause the failure of conventional machine learning models that rely on smooth structure-property relationships [8]. This technical guide examines how foundation models, trained on broad data and capable of capturing complex, non-linear relationships, are being engineered to recognize, learn from, and even exploit these critical discontinuities to accelerate the discovery of novel materials and therapeutics.

Foundation Models in Materials Science: Architecture and Mechanisms

Foundation models in materials science are characterized by their pre-training on vast, often unlabeled, datasets followed by adaptation to specific tasks. The transformer architecture, first introduced in 2017, serves as the foundational building block for many of these models, enabling them to handle complex, sequential data representations of materials, such as Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings or atomic coordinates [16].

Model Architectures and Training Paradigms

The field has largely diverged into two complementary architectural approaches, each suited to different aspects of the materials discovery pipeline:

Encoder-only models, inspired by the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) architecture, focus on understanding and generating meaningful representations from input data. These models are particularly well-suited for property prediction tasks, where they create rich, contextualized embeddings that capture essential material characteristics [16]. These embeddings can then be used as input to smaller, task-specific prediction heads.

Decoder-only models are designed for generative tasks, predicting and producing one token at a time based on given input and previously generated tokens. This architecture is ideal for inverse design, as it can systematically generate novel molecular structures by sequentially adding atoms or bonds [16].

A more recent advancement is the emergence of multimodal foundation models, such as MultiMat, which enable self-supervised training across different types of material data [31]. These models can simultaneously process and correlate multiple data modalities—including textual descriptions, structural information, and spectral data—creating a unified latent representation that captures richer material characteristics than any single modality could provide [31]. The training process typically involves an initial pre-training phase on broad data using self-supervision, followed by fine-tuning on labeled datasets for specific property prediction tasks, and optionally, an alignment phase where model outputs are refined to meet specific criteria such as chemical stability or synthesizability [16].

The Critical Challenge of Activity Cliffs

Defining and Identifying Activity Cliffs

In the context of materials science and drug discovery, activity cliffs present a significant challenge for predictive modeling. Formally, an activity cliff occurs when two molecules with high structural similarity (typically measured by Tanimoto similarity ≥0.9 using molecular fingerprints) exhibit a large difference in a target property or biological activity—often differing by at least an order of magnitude [14] [8]. This phenomenon is visually represented by the distribution of activity differences versus pairwise molecular distances, where activity cliffs appear as outliers significantly above the expected correlation trend [8].

The fundamental challenge posed by activity cliffs stems from their violation of the core assumption underlying most machine learning models in materials science: that small changes in input features should result in proportionally small changes in output properties. When this principle fails, conventional quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models exhibit significant prediction errors, as they tend to generate analogous predictions for structurally similar molecules [8]. Research has demonstrated that neither enlarging training set sizes nor increasing model complexity inherently improves predictive accuracy for these challenging compounds [8].

Computational Frameworks for Activity Cliff Management

Recent research has produced specialized computational frameworks designed specifically to address the activity cliff challenge:

Table 1: Computational Frameworks for Activity Cliff Management

| Framework | Core Methodology | Application | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| BitBIRCH [14] | Highly efficient clustering using binary fingerprints and Tanimoto similarity | Identifying or avoiding activity cliffs in large compound libraries | Converts O(N²) pairwise problem to O(N) + O(Nₘₐₓ²) via clustering |

| ACARL [8] | Reinforcement learning with contrastive loss and Activity Cliff Index (ACI) | De novo molecular design focused on high-impact SAR regions | Explicitly prioritizes activity cliff compounds during model optimization |

| MPNN_CatBoost [21] | Message Passing Neural Network + Categorical Boosting | Predicting binding affinities of Liquid Crystal Monomers | Stratified splitting of activity cliffs into training and test sets |

The BitBIRCH framework exemplifies how algorithmic innovation can transform computational bottlenecks into tractable problems. By clustering molecules first and then performing exhaustive pairwise analysis only within clusters, it dramatically reduces the computational burden of identifying activity cliffs across large libraries [14]. For generative tasks, the Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning (ACARL) framework introduces a quantitative Activity Cliff Index (ACI) to detect SAR discontinuities and incorporates them directly into the reinforcement learning process through a specialized contrastive loss function [8]. This approach actively shifts the model's optimization focus toward regions of high pharmacological significance, effectively leveraging activity cliffs rather than treating them as problematic outliers.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Workflow for Multimodal Foundation Model Training

The development of effective foundation models for materials science follows a systematic workflow that integrates data from multiple sources and modalities. The following Graphviz diagram illustrates this comprehensive process:

Diagram 1: Multimodal Foundation Model Training Workflow