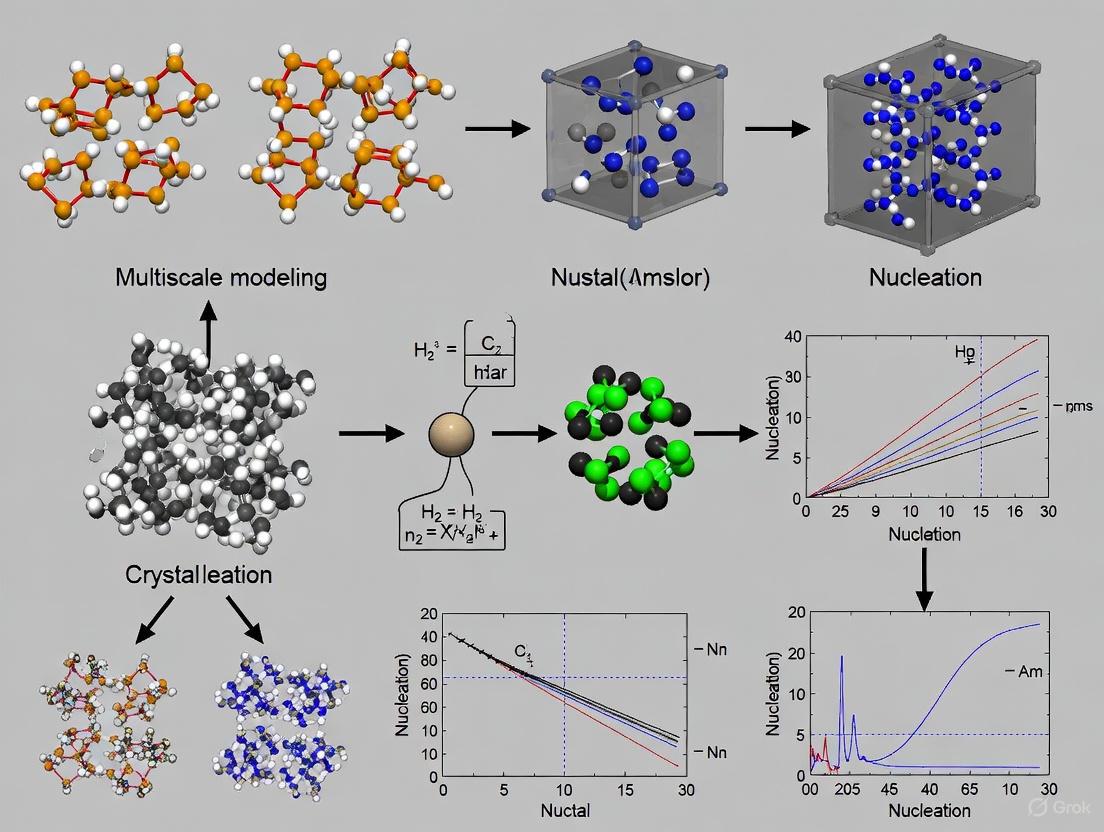

Multiscale Modeling of Inorganic Crystal Nucleation: From Atomic Mechanisms to Advanced Materials Design

This article comprehensively reviews the field of multiscale modeling for inorganic crystal nucleation, a critical process in materials science, chemical engineering, and pharmaceutical development.

Multiscale Modeling of Inorganic Crystal Nucleation: From Atomic Mechanisms to Advanced Materials Design

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the field of multiscale modeling for inorganic crystal nucleation, a critical process in materials science, chemical engineering, and pharmaceutical development. It explores the fundamental theoretical frameworks, including Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT), and details advanced computational methodologies such as quantum-accurate molecular dynamics enhanced by machine learning. The content addresses significant challenges in simulating rare nucleation events and overcoming time-scale limitations, while also presenting innovative strategies for process intensification and optimization. Furthermore, it examines rigorous model validation techniques and comparative analyses across different computational approaches. By synthesizing insights from atomistic simulations to industrial-scale process control, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a unified perspective on how multiscale modeling is revolutionizing the prediction and control of inorganic crystallization for designing next-generation materials.

Theoretical Foundations and Atomic-Scale Mechanisms of Inorganic Crystal Nucleation

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) stands as the primary theoretical framework for quantitatively describing the kinetics of phase transitions, a fundamental process in materials science, geology, and pharmaceutical development [1]. Formed in the 1930s based on the works of Becker, Döring, Volmer, and Weber, which in turn built upon Gibbs' ideas, CNT seeks to explain and quantify the immense variation observed in the time required for a new thermodynamic phase to spontaneously appear from a metastable state [2]. This initial step of nucleation often dominates the kinetics of new phase formation, determining whether a transformation occurs within experimental timescales or requires geological eons [1]. Within the context of multiscale modeling of inorganic crystal nucleation research, CNT provides a crucial, though simplified, thermodynamic and kinetic bridge between atomistic interactions and macroscopic crystallization phenomena. While its simplified assumptions are increasingly scrutinized, CNT remains a robust and widely used tool for comprehending and predicting nucleation behavior across diverse scientific and industrial applications [2].

Core Principles of Classical Nucleation Theory

The Thermodynamic Barrier

The central concept in CNT is the nucleation barrier, an energy hurdle that must be overcome for a stable nucleus of the new phase to form. The theory models the free energy change, ΔG, associated with the formation of a spherical nucleus of radius r as the sum of a bulk volume term and a surface term [1]:

ΔG = (4/3)πr³Δgᵥ + 4πr²σ

Here, Δgᵥ is the Gibbs free energy change per unit volume associated with the phase transition (negative under supersaturated conditions), and σ is the interfacial free energy per unit area (positive) [1]. The competition between these two terms results in a free energy profile that initially increases with radius, reaches a maximum, and then decreases. The initial increase is due to the dominance of the positive surface energy term for small clusters. Upon reaching a critical size, the negative bulk energy term prevails, making further growth energetically favorable [1].

The Critical Nucleus and the Nucleation Work

The maximum of the free energy curve corresponds to the critical nucleus, characterized by its critical radius, r_c, and the nucleation work, W (also denoted ΔG), which is the free energy required to form this critical nucleus [1] [3]. The critical radius is derived by setting the derivative of ΔG with respect to *r to zero:

r_c = 2σ / |Δgᵥ|

Substituting this back into the free energy equation yields the work of critical nucleus formation for a spherical nucleus [1]:

ΔG* = W* = (16πσ³) / (3|Δgᵥ|²)

This work of formation can also be expressed in terms of the number of molecules, n, in the critical nucleus and the thermodynamic driving force, Δμ (the difference in chemical potential between the parent and new phases). For a spherical critical nucleus, it is given by [3]:

W* = (4π/3γ) r_c² = (16π/3) γ³ / (ρ² Δμ²) = n |Δμ| / 2

where ρ* is the inverse of the molecular volume of the crystal. The nucleation work represents one-third of the total surface energy of the critical nucleus [3].

The Nucleation Rate

The central result of CNT is a prediction for the steady-state nucleation rate, R (or J), defined as the number of viable nuclei formed per unit volume per unit time [1] [3]. The CNT expression for the rate is:

R = Nₛ Z j exp( -ΔG* / kₚT )

The components of this equation are:

- ΔG*: The free energy barrier for forming a critical nucleus.

- Nₛ: The number of potential nucleation sites per unit volume.

- j: The rate at which atoms or molecules attach to the critical nucleus.

- Z: The Zeldovich factor, a dimensionless factor that accounts for the dissolution of a fraction of supercritical nuclei due to the curvature of ΔG near the critical size. It is given by Z = (W* / 3πn*² kₚT)^{1/2} [3].

The pre-exponential factor, Nₛ Z j, represents the dynamic part of the nucleation process and has a weaker temperature dependence compared to the exponential term. For condensed systems, this term typically ranges from 10⁴¹ to 10⁴³ s⁻¹m⁻³ [3].

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters in Classical Nucleation Theory

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Role in CNT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Radius | rc_ | The smallest radius of a stable nucleus. | Nuclei smaller than rc_ dissolve; larger nuclei grow. |

| Nucleation Work | ΔG, W | Free energy required to form the critical nucleus. | Determines the exponential term in the nucleation rate. |

| Interfacial Free Energy | σ, γ | Free energy per unit area of the interface between phases. | The primary source of the nucleation barrier. |

| Thermodynamic Driving Force | Δgᵥ, Δμ | Free energy difference per unit volume or molecule. | Provides the driving force for the phase transition. |

| Zeldovich Factor | Z | Accounts for the dissolution of supercritical nuclei. | A kinetic correction factor (typically 10⁻² to 10⁻³). |

| Attachment Frequency | j | Rate at which molecules join the critical nucleus. | Part of the dynamic pre-exponential factor. |

Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation

CNT distinguishes between two primary nucleation modes: homogeneous and heterogeneous. Homogeneous nucleation occurs spontaneously and randomly within the bulk of the parent phase, without the involvement of foreign surfaces. It is conceptually simpler but requires surmounting a significant energy barrier, making it relatively rare [1].

Heterogeneous nucleation is far more common and occurs on pre-existing surfaces, such as container walls, dust particles, or seed crystals [1]. The presence of these surfaces reduces the effective surface area of the nascent nucleus, thereby lowering the nucleation barrier. The reduction is quantified by a catalytic factor, f(θ), which depends on the contact angle, θ, between the nucleus and the substrate. The free energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation is given by [1]:

ΔGʰᵉᵗ = f(θ) ΔGʰᵒm

where f(θ) = (2 - 3cosθ + cos³θ) / 4. This factor is always less than 1, explaining why heterogeneous nucleation is kinetically favored. Imperfections like cracks and pores can further reduce the barrier by decreasing the exposed surface area of the nucleus [1].

Modern Re-evaluations and Advances

Computational Validation and Machine Learning

Modern computational approaches are rigorously testing and validating CNT's predictions. A landmark 2025 study on aluminum crystallization used a machine learning (ML) molecular dynamics (MD) model trained exclusively on liquid-phase Density Functional Theory (DFT) configurations [3]. This "crystal-unbiased" approach avoided the limitations of empirical interatomic potentials. The researchers identified emergent crystalline clusters using the pair entropy fingerprint (PEF) method, independent of predefined crystal patterns [3]. The key finding was that the homogeneous nucleation rate calculated directly from MD simulations showed excellent agreement with the CNT prediction that used MD-derived properties without any fitting parameters [3]. This strongly corroborates the validity of CNT's fundamental framework when accurate input parameters are used.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools in Modern Nucleation Studies

| Item / Method | Category | Function in Nucleation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) Interatomic Potentials | Computational Model | Enables quantum-accurate MD simulations of large systems by learning from DFT data. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Computational Method | Models atomic-scale kinetics and dynamics of nucleation and growth. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Method | Provides highly accurate quantum-mechanical calculations for training ML potentials. |

| Pair Entropy Fingerprint (PEF) | Analytical Method | Identifies emergent crystalline structures in simulations without predefined crystal patterns. |

| In situ Microscopy/Spectroscopy | Experimental Technique | Allows real-time monitoring and characterization of nucleation events. |

| Microreactors / Continuous Flow Systems | Process Technology | Enhances mixing and control to intensify nucleation processes. |

Limitations and Theoretical Extensions

Despite its conceptual utility, CNT is based on significant simplifications that often lead to quantitative discrepancies with experimental data [2]. A primary criticism is the "capillary assumption," which treats small, nanoscale nuclei as microscopic droplets with the same macroscopic properties, such as interfacial tension (σ) and density [2]. This assumption ignores the atomic structure of both the nucleus and the parent phase.

Statistical mechanical treatments have been developed to provide a more rigorous foundation. These approaches define the partition function for the system and consider the work of cluster formation without relying on the capillary assumption, offering a pathway to more accurate descriptions [1] [2].

Furthermore, CNT is being extended to more complex scenarios. For example, research on hard spheres under simple shear flow demonstrated that the impact of shear on crystallization kinetics could be rationalized within CNT by adding an elastic work term proportional to the droplet volume, alongside considering the change in interfacial work [4].

Non-Classical Nucleation Pathways

Evidence is mounting for non-classical pathways that deviate from the CNT model of atom-by-atom addition. One prominent mechanism is the aggregation of pre-nucleation clusters [2]. In this pathway, stable solute species (clusters) form and aggregate, eventually reaching a stable size. This allows the system to "tunnel" through the high energy barrier predicted by CNT, particularly when cluster collision rates are high [2]. A well-studied example is the crystallization of calcium carbonate, which is now understood to often proceed through a series of stepwise phase transitions involving liquid-precursor phases and amorphous intermediates, rather than a direct transformation to a crystalline phase [2].

Experimental Protocols for Validating CNT

Protocol: Quantum-Accurate MD Simulation of Nucleation

This protocol is based on the recent study of aluminum crystallization [3].

- Model Development: Train a machine-learning interatomic potential (e.g., an artificial neural network) exclusively on DFT configurations of the liquid phase. This ensures the model is unbiased toward any specific solid crystal structure.

- System Preparation: Initialize a large-scale MD simulation cell (containing thousands to millions of atoms) with the material in the liquid phase at the desired temperature and pressure.

- Spontaneous/Seeded Crystallization:

- For homogeneous nucleation, simply run the simulation in a deeply supercooled state and await spontaneous nucleation.

- For seeded studies, manually insert a crystalline cluster of a specific size into the liquid.

- Cluster Identification and Analysis: Use a pattern-free method like the Pair Entropy Fingerprint (PEF) to identify and characterize emergent crystalline clusters throughout the simulation trajectory. This method analyzes the local entropy around each atom to distinguish crystal-like environments from liquid-like ones.

- Rate Calculation:

- Direct MD Measurement: Perform multiple independent simulations to statistically determine the nucleation rate, J, by measuring the average time for a critical nucleus to form and the volume of the simulation box.

- CNT Prediction: Use MD simulations to independently calculate all properties in the CNT rate equation: the interfacial free energy (γ), the thermodynamic driving force (Δμ), the atomic transport coefficient (D), and the critical nucleus size (n). Compute J using the CNT formula.

- Validation: Compare the nucleation rate obtained from direct MD observation with the rate predicted by CNT using the simulation-derived parameters. The close agreement in the aluminum study validated CNT at the atomic scale [3].

Multiscale modeling of inorganic crystals relies heavily on structural databases for validation and input.

- Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD): The world's largest database of fully evaluated published inorganic crystal structures, now also including peer-reviewed theoretical structures [5]. It is essential for comparing simulated nucleation outcomes with experimental crystal data.

- Materials Project & AFLOW: Open-access databases containing millions of calculated crystal structures and material properties, useful for high-throughput screening and computational design of materials [5].

Classical Nucleation Theory continues to be a foundational pillar in the multiscale modeling of inorganic crystal nucleation. Its core principles, built around the concepts of a critical nucleus and a thermodynamic barrier, provide an intuitive and powerful framework for understanding and predicting phase transition kinetics. While its historical simplifications can limit quantitative accuracy, modern re-evaluations using advanced computational methods like machine-learning-driven molecular dynamics are demonstrating a remarkable resilience and validity of the CNT framework when provided with accurate input parameters. The emergence of non-classical pathways and the development of more sophisticated statistical mechanical models are not rendering CNT obsolete but are rather refining its domain of applicability and integrating it into a more complete picture of nucleation. For researchers and engineers, CNT remains an indispensable tool, whose ongoing evolution, fueled by computational and experimental advances, continues to enhance our ability to design and control materials at the most fundamental level.

Within the framework of multiscale modeling of inorganic crystal nucleation, a critical challenge lies in the experimental validation of model predictions. This is particularly acute when probing the initial stages of nucleation—the formation and evolution of nascent nuclei—under non-ambient, extreme conditions such as high temperature, high pressure, or extreme supersaturation. These conditions are ubiquitous in industrial processes, from pharmaceutical crystallization to materials synthesis. The transient nature, minute size (often < 2 nm), and low concentration of these initial aggregates make direct observation a formidable task, creating a significant gap between theoretical models and empirical verification.

Core Experimental Challenges and Quantitative Data

The primary challenges in observing nascent nuclei are summarized in the table below, which contrasts the ideal observables with the current experimental limitations.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Probing Nascent Nuclei

| Challenge | Description | Typical Scale/Value | Experimental Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Direct imaging of critical nuclei and sub-critical clusters. | 0.5 - 2 nm | Standard TEM struggles; atomic resolution required. |

| Temporal Resolution | Capturing nucleation events, which are stochastic and fast. | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Many techniques (e.g., XRD) are too slow for initial kinetics. |

| Stochasticity | Nucleation is a rare event per unit volume; observing a statistically significant number of events is difficult. | ~1-100 events/cm³/s | Requires high-throughput methods or long observation times. |

| Condition Control | Precisely generating and maintaining extreme T, P, or S. | T: > 150°C; P: > 1 GPa; S: > 10 | Sample environment can limit probe access or introduce gradients. |

| Probe Sensitivity | Detecting the weak signal from a small number of atoms against the background of the mother phase. | ~10-1000 atoms/cluster | Signals (X-ray scattering, vibrational spectra) are exceedingly weak. |

Advanced Methodologies for Probing Nucleation

To overcome these challenges, several advanced techniques have been developed. The following table outlines their core principles, applications, and detailed protocols.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Probing Nascent Nuclei

| Technique | Core Principle | Key Application in Nucleation | Detailed Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ Liquid-Phase Transmission Electron Microscopy (LP-TEM) | A liquid cell with electron-transparent windows enables real-time imaging of processes in solution within a TEM. | Visualizing the trajectory and growth kinetics of individual metal and semiconductor nanocrystals. | 1. Cell Fabrication: Assemble a liquid cell with two SiNx membrane windows. 2. Solution Loading: Inject a precursor solution (e.g., HAuCl₄ for gold) into the cell cavity via microfluidic ports. 3. Sealing: Secure the cell in a specialized TEM holder. 4. Imaging: Insert holder into TEM. Use a low electron dose rate (5-50 e⁻/Ų/s) to minimize radiolysis. 5. Triggering: Nucleation is often induced by the electron beam itself or by heating the cell. 6. Data Acquisition: Record a video stream at 1-30 frames per second. |

| X-Ray Photon Correlation Spectroscopy (XPCS) | Uses coherent X-rays to measure the speckle pattern fluctuations from a sample, which report on its dynamics. | Probing the dynamics and aging of pre-nucleation clusters and the onset of nucleation in glasses and solutions. | 1. Sample Preparation: Load a supersaturated solution or glass into a capillary or diamond anvil cell (DAC) for high-pressure studies. 2. Beamline Setup: At a synchrotron, select a coherent X-ray beam (e.g., ~10 keV). 3. Measurement: Focus the beam on the sample and collect a series of sequential diffraction patterns with a 2D detector. 4. Analysis: Compute the two-time correlation function from the speckle patterns to extract relaxation times and dynamical information related to cluster formation. |

| Fast Scanning Calorimetry (FSC) | Utilizes ultra-high heating and cooling rates (up to 1,000,000 K/s) to study phase transitions in minute samples. | Determining crystal nucleation rates in deeply supercooled liquids and polymers, avoiding crystallization during cooling. | 1. Sample Preparation: Deposit a nanogram-scale film of the material onto the sensitive area of the microchip sensor. 2. Conditioning: Melt the sample and equilibrate. 3. Quenching: Apply a ultra-fast cooling pulse to achieve a deep supercooled state without crystallization. 4. Reheating: Apply a linear heating scan to crystallize and melt the sample. The nucleation rate is derived from the analysis of the exothermic crystallization peak upon reheating. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride (SiNx) Membranes | Electron-transparent windows for LP-TEM cells, containing the liquid sample while allowing beam penetration. |

| Diamond Anvil Cell (DAC) | Generates extreme static pressures (>> 1 GPa) for studying nucleation under high-pressure conditions. |

| Microfluidic Chips | Precisely mix reagents to generate controlled supersaturation and observe nucleation in a confined, flow-controlled environment. |

| Metal Salt Precursors (e.g., HAuCl₄, AgNO₃) | Common model systems for studying inorganic (metal) nucleation kinetics and pathways in solution. |

| Synchrotron-Grade X-Ray Beams | Provides the high flux and coherence required for techniques like XPCS and SAXS to detect weak signals from nanoscale clusters. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Title: Experimental-Modeling Iterative Workflow

Title: Multiscale Modeling Data Flow

In the multiscale modeling of inorganic crystal nucleation research, supersaturation stands as the fundamental thermodynamic driver without which crystallization cannot occur. It represents the essential deviation from equilibrium, creating the chemical potential gradient that forces molecules from the solution state to organize into stable solid phases. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering supersaturation is crucial for controlling crystal size, morphology, and polymorph selection—factors directly impacting drug bioavailability, stability, and manufacturability. This technical guide examines supersaturation's role across scales, from molecular-level thermodynamics to industrial process control, providing both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for its quantification and application in crystalline product design.

Thermodynamic Foundations of Supersaturation

Fundamental Definitions and Equations

Supersaturation originates from the difference in chemical potential between a solute in solution and in the crystalline state. At the molecular level, this relationship is defined by:

Saturated Solution: ( μi^{crys} = μi^{sol} = μi^0 + RT \lnγi c_i ) where the chemical potential of species i is identical in both solution and crystalline phases [6].

Supersaturated Solution: ( μi^{sol} > μi^{crys} ) where the chemical potential in solution exceeds that in the crystal, creating the thermodynamic driving force for crystallization [6].

The degree of supersaturation (β) quantifies this driving force and is incorporated into the energy barrier for nucleation (ΔGn) through the expression: [ ΔGn = \left[-\frac{kT(4πr^3)}{V\lnβ}\right] + 4πr^2γ ] where k is Boltzmann's constant, γ represents the interfacial free energy between nucleus and solution, r is the effective radius of the crystal nucleus, and V is the molecular volume [6].

Phase Behavior and Metastable Zone

The simplified phase diagram for crystallization reveals critical operational zones:

- Undersaturated Zone: Crystals dissolve; no growth occurs

- Metastable Zone: Crystal growth occurs without spontaneous nucleation

- Labile Zone: Spontaneous nucleation and growth occur

This diagram illustrates why supersaturation must be carefully controlled—rapid entry deep into the labile zone produces numerous small crystals, while maintained operation in the metastable zone enables controlled growth of larger crystals [6].

Supersaturation in Crystallization Kinetics

Nucleation Mechanisms

Supersaturation directly governs nucleation rates through its influence on the energy barrier to stable nucleus formation. The nucleation rate (Jn) follows: [ Jn = Bs \exp\left(-\frac{ΔGn}{kT}\right) ] where Bs incorporates kinetic factors related to solubility and diffusion [6]. Higher supersaturation reduces ΔGn, exponentially increasing nucleation rates.

Advanced research reveals nucleation often proceeds through multi-step pathways rather than direct organization from solution. Evidence from alumina cluster formation in Fe-O-Al melts demonstrates how various cluster types form depending on saturation ratios, leading to different crystallization pathways [7]. This challenges Classical Nucleation Theory and explains phenomena like the appearance of metastable γ- and δ-alumina phases alongside stable α-Al₂O₃ [7].

Crystal Growth and Habit Modification

Once stable nuclei form, supersaturation controls growth kinetics and ultimately crystal habit. The relative growth rates of different crystal faces determine the final morphology, with slow-growing faces typically dominating the crystal habit [8]. However, contrary to conventional understanding, recent studies show that fast-growing faces can sometimes increase in size and encompass the crystal while slow-growing faces may disappear from the morphology [8].

In industrial applications, this relationship is crucial—needle-like crystals caused by high supersaturation can create filtration difficulties, while optimized supersaturation profiles can produce crystals with improved flow and packaging properties [8].

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters for Inorganic Salt Crystallization

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Experimental Range | Determination Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleation rate constant | k_b | #/m³·s | System-dependent | Population balance modeling |

| Nucleation order | b | - | 1-2 | Parameter estimation |

| Growth rate constant | k_g | m/s | System-dependent | Desupersaturation curves |

| Growth order | g | - | 1-2 | Parameter estimation |

| Activation energy | E_a | kJ/mol | Temperature-dependent | Multiple temperature trials |

Experimental Determination of Kinetic Parameters

Automated Kinetic Parameter Determination

Recent advances enable automated determination of crystallization kinetics through standardized equipment and models. This approach, demonstrated for potassium chloride and potassium sulfate in ethanol-water mixtures, involves:

- Equipment: Technobis Crystalline system with in situ imaging

- Measurement: Automated crystal count and size determination

- Modeling: Population balance equations incorporating activity coefficients for strong electrolytes

- Output: Secondary nucleation and crystal growth kinetic constants [9]

This methodology addresses the critical challenge of comparability between kinetic parameters determined through different experimental approaches, enabling direct comparison of organic and inorganic solutes based on their nucleation and growth constants [9].

Parameter Estimation Workflow

For batch cooling crystallization, parameter estimation follows a systematic protocol:

- Experimental Design: Conduct multiple isothermal desupersaturation experiments at varying initial supersaturation levels

- Data Collection: Monitor concentration and crystal size distribution (CSD) throughout the process

- Model Specification: Define population balance equations with nucleation ( B = kb (S-1)^b ) and growth ( G = kg (S-1)^g ) rate expressions

- Parameter Estimation: Use facilities like gEST in gPROMS to determine optimal parameter set θ = {kb, b, kg, g} [10]

- Model Validation: Compare predictions with experimental data not used in parameter estimation [10]

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for Crystallization Studies

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Technobis Crystalline | Automated crystallization monitoring | In situ imaging for crystal count and size |

| gPROMS with gEST | Parameter estimation platform | Kinetic parameter optimization from experimental data |

| Population Balance Model (PBM) | Crystal size distribution prediction | Linking micro-scale kinetics to macro-scale CSD |

| Activity Coefficient Models | Accounting for non-ideal solution behavior | Strong electrolyte systems in mixed solvents |

| In-situ Particle Size Analyzer | Real-time CSD monitoring | Tracking crystallization progress without sampling |

Supersaturation Control in Process Optimization

Cooling Strategy Design

In batch cooling crystallization, temperature serves as the primary manipulated variable for supersaturation control. The cooling profile directly impacts nucleation and growth kinetics, ultimately determining the crystal size distribution (CSD) [10]. Research demonstrates that:

- Fast cooling generates high supersaturation, favoring nucleation over growth and producing numerous small crystals

- Controlled cooling maintains moderate supersaturation in the metastable zone, favoring growth and producing larger crystals with narrower size distribution [10]

Advanced implementations use dynamic optimization with validated kinetic models to compute optimum cooling profiles for specific objectives like maximizing mean crystal size or achieving target CSD [10].

Multiscale Modeling Framework

Supersaturation functions as the connecting variable across scales in crystallization process modeling:

- Microscale: Population balance models predict crystal size distribution using supersaturation-dependent kinetic expressions

- Mesoscale: Fluid dynamics and heat transfer models determine local supersaturation distribution within crystallizers

- Macroscale: Flow and temperature control systems manipulate bulk supersaturation through cooling or antisolvent addition [10]

This integrated approach enables using crystallization models as soft sensors for predicting crystal size and designing model-based control schemes—critical for efficient separations and purifications in pharmaceutical manufacturing [10].

Supersaturation serves as the fundamental thermodynamic driver throughout the crystallization process, from initial nucleation to final crystal growth. Its careful control enables manipulation of critical product attributes including crystal size distribution, morphology, and polymorphic form. Recent advances in automated kinetic parameter determination, multiscale modeling, and understanding of multi-step nucleation pathways provide researchers with powerful tools for supersaturation management. For pharmaceutical scientists, mastering these relationships is essential for designing robust crystallization processes that consistently deliver products with desired performance characteristics, particularly as drug substances increasingly challenge conventional crystallization approaches with complex solid-form landscapes and demanding quality requirements.

The transition from a liquid to a solid phase, known as crystal nucleation, is the foundational first step in microstructure evolution that determines the ultimate properties and performance of a vast range of materials, from metallic alloys to pharmaceutical compounds [11]. Within the context of multiscale modeling of inorganic crystal nucleation, understanding the precise atomistic pathways and the nature of the critical nucleus—the smallest stable seed of the new phase—presents a central challenge. Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) has long provided the fundamental framework for describing this process, but its quantitative predictions often fall short, particularly in solid-state transformations where atomic mobility is limited and the thermodynamic landscape is complex [11] [12].

This whitepaper delves into the advanced computational and theoretical approaches that are illuminating the atomistic mechanisms of nucleation. We explore how modern numerical algorithms are enabling researchers to map the intricate energy landscapes of transforming systems, identify the critical nucleus, and quantify the kinetic pathways that bypass the limitations of traditional CNT. By integrating insights from cutting-edge research, we provide a technical guide for scientists and engineers seeking to control nucleation processes in materials design and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Moving Beyond Classical Theory

The Limits of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT)

CNT describes nucleation as a thermally activated process where stochastic fluctuations in a supersaturated parent phase lead to the formation of a nascent particle of the new phase. The theory posits a continuous increase in free energy until the cluster reaches a critical size, beyond which growth becomes thermodynamically favorable. The free energy barrier, ΔG, and the critical radius, r, are given by: ΔG* = (16πγ³)/(3ΔGᵥ²) and r = -2γ/ΔGᵥ where γ is the interfacial energy and ΔG*ᵥ is the volumetric free energy driving force [12].

A core, and often strong, assumption of CNT is that all possible compositional fluctuations are accessible and that the properties of the nascent nucleus are identical to those of the bulk new phase [11]. This assumption breaks down in many inorganic and solid-state systems, particularly at low temperatures where atomic mobility is limited. In such kinetically-constrained systems, thermally-induced stochastic clusters may not form on relevant timescales.

A Paradigm Shift: Geometric Cluster Activation and Alternative Pathways

Recent models propose complementary mechanisms to CNT. One such approach is the "geometric cluster" model, which suggests that in systems with limited atomic mobility, the statistical geometric clusters inherent to any solution can serve as the origin of nuclei [11]. Instead of forming purely from stochastic fluctuations, these pre-existing clusters can be "activated" to grow, providing a pathway that circumvents the high energy barriers predicted by CNT. This model has demonstrated success in predicting phase competition in Al-Ni-Y metallic glasses and precipitate number densities in Cu-Co and Fe-Cu alloys [11].

Furthermore, nucleation is increasingly recognized as a multistep process that may involve intermediate phases, such as dense liquid droplets or metastable crystalline phases, which lower the overall activation barrier by providing a more favorable kinetic route to the stable phase [12] [13].

Computational Methodologies for Mapping Nucleation Pathways

Owing to the transient nature and nanoscale of critical nuclei, computational modeling has become an indispensable tool for probing nucleation events at the atomistic level [12]. The key challenge is that the critical nucleus represents a saddle point on the multidimensional free energy landscape—a maximum in one direction and a minimum in all others. Advanced algorithms are required to locate these saddle points and compute the Minimum Energy Paths (MEPs) that connect the liquid and solid phases.

Table 1: Key Computational Methods for Locating Saddle Points and Minimum Energy Paths

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Core Principle | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Walking Methods | Gentlest Ascent Dynamics (GAD) [12], Dimer Method [12], Shrinking Dimer Dynamics (SDD) [12] | Starts from an initial state (e.g., liquid) and iteratively climbs the energy landscape to a saddle point using the lowest eigenmode of the Hessian matrix. | Does not require a priori knowledge of the final state (solid). Efficient for finding index-1 saddle points. |

| Path-Finding Methods | Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) [12], String Method [12] | Defines a discrete path (a "band" or "string") between two known states (liquid and solid) and relaxes it to the MEP. | Provides the entire transition pathway, not just the saddle point. Offers a more complete picture of the nucleation mechanism. |

Surface Walking Methods: Climbing the Energy Landscape

Surface walking methods are powerful for locating saddle points starting from a single initial state. A key development in this class is the Shrinking Dimer Dynamics (SDD), which refines the classic dimer method [12]. In SDD, a "dimer"—two images of the system separated by a small distance—is used to approximate the lowest curvature mode. The algorithm proceeds through alternating rotation and translation steps:

- Rotation Step: The dimer is rotated to align with the direction of the lowest eigenmode (the direction of negative curvature).

- Translation Step: The dimer's center is moved along this direction, with the component of the force parallel to the dimer reversed, effectively pushing it uphill toward the saddle point.

The system is described by the following dynamics [12]:

μ₁ẋᵃ = (I - 2vvᵀ)((1-α)F₁ + αF₂)(Translation)μ₂v̇ = (I - vvᵀ)(F₁ - F₂)/l(Rotation) wherevis the orientation vector,lis the dimer length,F₁andF₂are forces on the dimer images, andμare relaxation constants.

Path-Finding Methods: Tracing the Minimum Energy Path

The String Method is a prominent path-finding approach that has been widely applied to nucleation problems [12]. It involves the following workflow, which is also depicted in Figure 1:

- Initialization: A discrete path (the "string") is initialized between the liquid (parent) and solid (product) basins.

- Evolution: The images comprising the string are evolved according to the driving forces, typically by gradient descent:

ẋ = -∇V(x). - Reparameterization: After each evolution step, the images are redistributed along the path to maintain equal arc-length spacing, which prevents clustering and ensures an accurate resolution of the MEP across the entire path.

Figure 1: The String Method Workflow for determining the Minimum Energy Path (MEP) between liquid and solid states.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation. Advanced characterization and process intensification techniques are crucial for probing nucleation at relevant time and length scales.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

- In Situ Microscopy and Spectroscopy: Techniques like in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-speed atomic force microscopy (AFM) allow for the direct, real-time observation of nucleation events, providing insights into kinetics and structural evolution [13]. These methods can capture the formation and growth of pre-nucleation clusters and critical nuclei.

- Fast Scanning Chip Calorimetry (FSC): FSC enables the study of crystallization kinetics over a wide range of cooling rates and temperatures. For instance, it has been used to identify a transition in the nucleation mechanism of Polyamide 11 (PA 11) at high supercooling, linked to a shift from heterogeneous to homogeneous nucleation [13].

Process Intensification Strategies

Innovative processing methods are being developed to enhance control over nucleation:

- Membrane Crystallization (MCr): This hybrid technology uses membranes to supersaturate a solution and act as a heterogeneous nucleation interface. MCr allows for precise control over crystal nucleation and is an energy-efficient method for producing high-purity solids, with applications in desalination and wastewater treatment [13].

- Microreactors and Continuous Flow Systems: These systems enhance micromixing and heat transfer, significantly reducing mixing times compared to conventional batch reactors. This enables superior control over the supersaturation distribution, a key factor governing nucleation and final particle properties [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Nucleation Research |

|---|---|

| Metallic Glass Alloys (e.g., Al-Ni-Y) | Model systems for studying phase competition and the kinetics of solid-state nucleation in kinetically-constrained environments [11]. |

| Stoichiometric Nd₂Fe₁₄B Alloy | A key material for investigating competitive multiphase nucleation and crystal growth under rapid solidification conditions, relevant for permanent magnets [14]. |

| Polyamide 11 (PA 11) | A polymer used to study temperature-dependent nucleation mechanisms (homogeneous vs. heterogeneous) and polymorphism [13]. |

| Protic and Solvate Ionic Liquids | Advanced solvents for the potential-driven growth of metal crystals, allowing for fine control over electrochemical nucleation [13]. |

| Calcium-Silicate-Hydrate (C-S-H) | The main binding phase in cement; studied via nucleation and growth models to understand and control the early hydration of alite [13]. |

Case Studies in Inorganic Materials

The integration of advanced computational methods with experimental data has led to profound insights in specific material systems.

Solid-State Precipitation in Alloys

In solid-state phase transformations, long-range elastic interactions arising from misfit strains between the nucleus and the matrix can profoundly influence the morphology and orientation of critical nuclei. Computational studies using the methods outlined in Section 3 have predicted non-spherical, often plate-like or needle-like, critical nuclei to minimize the total strain energy [12]. This deviates strongly from the spherical cap model often assumed in CNT.

Crystallization of Metallic Glasses

The "geometric cluster" model has been successfully applied to predict phase competition during the crystallization of Al-Ni-Y metallic glasses [11]. This model considers the statistical distribution of atomic clusters that are inherent to the glassy structure. The activation and growth of these clusters, rather than the formation of entirely new stochastic fluctuations, can explain the observed nucleation densities and the selection between competing crystalline phases.

Competitive Nucleation in Undercooled Melts

Research on the rapid solidification of Nd-Fe-B alloys demonstrates the critical role of competitive nucleation between multiple phases (e.g., the pro-peritectic γ-Fe, the metastable χ phase, and the stable ϕ phase) [14]. Multiscale modeling that couples nucleation kinetics with heat transfer and fluid flow can accurately predict the phase selection in atomized droplets. The modeling reveals that in smaller droplets, nucleation of γ-Fe occurs first at low undercooling, while in highly undercooled droplets, the ϕ and χ phases nucleate simultaneously, avoiding the formation of the soft magnetic α-Fe phase and optimizing magnetic properties [14]. This competitive landscape is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Competitive Nucleation Pathways in an Undercooled Nd-Fe-B Melt. Phase selection is governed by the level of undercooling.

The field of nucleation research is being shaped by several emerging trends. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence (ML/AI) is accelerating the discovery process, enabling data-driven modeling, predictive analytics, and automated optimization of crystal growth parameters [15]. Furthermore, the use of microgravity environments, such as those in reduced gravity symposiums and space station experiments, provides a unique platform to study nucleation phenomena in the absence of buoyancy-driven convection and sedimentation, thereby validating ground-based models [15].

In conclusion, the journey from liquid to solid is governed by complex atomistic pathways and the formation of a critical nucleus, a process that modern multiscale modeling has shown to be far richer than previously envisioned by Classical Nucleation Theory. The synergy of advanced computational algorithms—such as the String Method and Shrinking Dimer Dynamics—with innovative experimental techniques like in situ microscopy and membrane crystallization is providing unprecedented insights. For researchers in materials science and drug development, mastering these tools and concepts is key to designing materials with tailored microstructures and optimizing processes for crystal formation, ultimately enabling the precise control of material properties from the atom up.

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) has long provided the foundational framework for understanding crystallization, describing it as a process where atoms or molecules form stable nuclei that then grow through the sequential, monomer-by-monomer addition of building blocks [16] [13]. However, advanced experimental and computational techniques have revealed numerous crystallization phenomena in inorganic, organic, and biological systems that cannot be adequately explained by this classical model [16] [17]. These observations have led to the identification of non-classical crystallization pathways, which involve intermediate, metastable states and particle-based aggregation mechanisms [16] [18]. Concurrently, the study of dendritic structures—highly branched, fractal morphologies—has emerged as a critical area for understanding how non-classical pathways influence final crystal morphology and properties [19] [20]. This guide examines these interconnected concepts within the context of multiscale modeling for inorganic crystal nucleation research, providing technical depth on mechanisms, characterization methods, and computational approaches relevant to scientists and drug development professionals.

Non-Classical Crystallization Pathways: Mechanisms and Intermediates

Non-classical crystallization diverges from CNT through the involvement of complex, multi-stage processes and transient intermediate phases. The following table summarizes the primary non-classical pathways and their characteristics.

Table 1: Key Non-Classical Crystallization Pathways and Characteristics

| Pathway | Key Intermediate | Governing Principle | Impact on Final Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Nucleation Clusters | Stable solute clusters existing before nucleation [18] | Continuous density fluctuations; no defined nucleation barrier [16] | Influences polymorphism and crystal size distribution [16] |

| Two-Step Nucleation | Dense liquid or amorphous precursor phase [16] [18] | Nucleation occurs within a metastable dense liquid phase [16] | Can enable crystal forms inaccessible via direct nucleation [17] |

| Oriented Attachment | Nanoparticles or "meso-crystals" [20] | Aligned crystallographic fusion of nanoparticles [16] [20] | Creates single crystals with internal defects or strain [16] |

| Polymer-Induced Precursor Stabilization | Amorphous polymer-mineral composite [17] [20] | Organic molecules stabilize transient amorphous phases [17] | Generates complex biomimetic morphologies [17] |

These pathways are not mutually exclusive and can intertwine during crystallization. For instance, an amorphous precursor may form via a two-step mechanism and then subsequently undergo growth via oriented attachment. The shift between classical and non-classical pathways can be modulated by synthesis conditions, such as the H2O/SiO2 and ethanol/SiO2 ratios in zeolite crystallization [21].

Dendritic Growth as a Non-Classical Phenomenon

Dendritic morphologies represent a clear manifestation of non-classical growth, where kinetic factors dominate over thermodynamic equilibrium. These fractal, tree-like structures form under diffusion-limited conditions where the rate of particle diffusion to the growing crystal is slower than the rate of incorporation at the crystal surface.

Quantitative Analysis of Dendritic Fractals

Reaction-diffusion frameworks (RDF) provide an ideal system for studying dendritic growth. Quantitative studies on the fractal crystallization of benzoic acid in gelatin-based systems have demonstrated a direct link to Diffusion-Limited Aggregation (DLA) theory [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Dendritic Fractal Growth in Benzoic Acid (Gelatin System) [19]

| Parameter | Impact on Dendritic Morphology | Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Fractal Dimension (D) | Measures branch density; D ~1.71 for ideal DLA [19] | Converged toward 1.71–1.74 at high supersaturation |

| Inner [Benzoate] Concentration | Controls supersaturation and branching density [19] | Higher [BZ] led to denser aggregation, branch thickening |

| Gel Matrix Chemistry | Modulates interfacial energy and diffusion [19] | Gelatin promoted DLA dendrites; Agar yielded spherulites |

| Diffusion Rate | Determines tip splitting and branch thickness [19] | Slower diffusion promoted branch thickening, reduced D |

Integration with Oriented Aggregation for 1D Crystal Growth

A significant advancement is the integration of dendritic growth with the non-classical mechanism of oriented aggregation to achieve continuous, high-aspect-ratio single crystals. This hybrid pathway overcomes the inherent randomness of conventional dendrites.

Diagram 1: Oriented aggregation for 1D crystal growth workflow.

This process yields dendrite branches with a uniform diameter and crystallographic orientation, achieving aspect ratios exceeding 10,000:1 [20]. The resulting structures are single crystals, distinct from polycrystalline aggregates, due to the perfect crystallographic alignment during oriented attachment.

The Experimental Toolkit: Probing Non-Classical Pathways

Elucidating non-classical pathways requires advanced in situ and ex situ techniques capable of detecting transient intermediates and quantifying crystal growth in real-time.

Key Experimental Methodologies

- In Situ Liquid-Phase Electron Microscopy: Allows direct observation of nucleation and growth dynamics in inorganic nanomaterials at nanoscale resolution. However, it can be challenging for beam-sensitive soft materials [16].

- In Situ Spectroscopy (e.g., NMR, FTIR): Monitors solution speciation and the evolution of molecular clusters during the early stages of nucleation, providing information on pre-nucleation clusters [13].

- Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM): Essential for characterizing the size, structure, and alignment of nanoscale precursors and meso-crystals in a vitrified, native state without beam damage [20].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) & Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD): SEM reveals crystal morphology and surface features, while PXRD confirms crystallographic structure, phase purity, and can detect embedded strain from non-classical growth [19] [20].

Detailed Protocol: Fractal Crystallization in a Reaction-Diffusion Framework

This protocol outlines the procedure for quantitatively studying dendritic growth of benzoic acid (BA) in a gel matrix [19].

1. Reactor Setup:

- Use a custom 2D plexiglass reactor with a thin circular cavity (e.g., 0.7 mm thick, 8.8 cm diameter).

- Prepare the inner gel phase by dissolving gelatin (8% w/w) or agar (1% w/w) in an aqueous sodium benzoate solution at the desired concentration (e.g., 0.05 M to 0.20 M).

- Heat the mixture with stirring until homogenized, maintaining temperature below 45°C for gelatin to prevent denaturation.

- Pour 18 mL of the solution into the reactor and seal it. Allow gelation for 2 hours (agar) or 24 hours (gelatin) at a controlled temperature of 19 ± 1°C.

2. Initiating Crystallization:

- Remove the gel from the inner circle of the reactor to create a defined reaction-diffusion interface.

- Carefully add 3 mL of the outer HCl solution (e.g., 1.00 M) to this inner reservoir.

3. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Monitor fractal growth optically using a digital camera with a macro lens at fixed time intervals.

- For fractal dimension analysis, threshold the images to binary and use the box-counting method (e.g., with the FracLac plugin in ImageJ).

- Plot ln N(ε) against ln (ε), where N(ε) is the number of boxes of size ε that contain crystal. The negative slope of the linear fit is the fractal dimension (D).

- Wash the resulting crystals carefully for subsequent SEM and PXRD characterization to correlate morphology with crystal structure and strain.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Non-Classical Crystallization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental System | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin & Agar | Forms a 3D gel matrix to suppress convection, creating a diffusion-controlled environment [19] | Reaction-diffusion frameworks for fractal crystallization [19] |

| Water-Soluble Polymers (e.g., PVA, Silk Fibroin) | Stabilizes nano-sized meso-crystals and enables oriented aggregation mechanism [20] | Production of high-aspect-ratio single crystals via regulated dendrite growth [20] |

| Silicon-Containing Organic Structure-Directing Agents | Templates the formation of specific zeolite frameworks during synthesis [16] | Investigation of intertwined classical/non-classical pathways in ZSM-5 formation [21] |

| Biomolecules from Mineralized Tissues | Serves as a native organic scaffold to structure amorphous precursor phases in vitro [17] | Remineralization studies to understand biological crystal growth [17] |

Computational Modeling of Nucleation and Growth

Computational approaches are indispensable for understanding the multiscale nature of nucleation, providing atomistic insights and bridging the gap between theory and experiment [12] [13].

Key Algorithmic Approaches

A primary challenge in simulating nucleation is that it is a "rare event." Specialized algorithms have been developed to efficiently locate transition states and pathways [12]:

- Path-Finding Methods: These algorithms compute the Minimum Energy Path (MEP) between initial and final states.

- String Method: Evolves a discrete path (a "string") in the high-dimensional configuration space until it converges to the MEP, effectively mapping the reaction coordinate [12].

- Nudged Elastic Band (NEB): Connects two known states with a band of images that is optimized to find the saddle point [12].

- Surface Walking Methods: These methods locate saddle points starting from a single initial state without prior knowledge of the final state.

- Dimer Method: Uses a first-order algorithm (requiring only energy and force calculations) to find saddle points by rotating and translating a "dimer" of two closely spaced images [12].

- Gentlest Ascent Dynamics (GAD): A dynamical system that evolves the system configuration and a direction vector to climb the energy landscape along the softest mode [12].

- Advanced Sampling Techniques: Methods like metadynamics and forward flux sampling are used to overcome large energy barriers and sample rare transition events in complex systems with rough energy landscapes [12].

Diagram 2: Computational methods for nucleation analysis.

Application to Multiscale Modeling

These computational methods enable the prediction of critical nucleus morphology in solid-state phase transformations, including the effects of long-range elastic strain [12]. They can also be used to explore complex, non-classical events, such as multiple barrier-crossing during solid melting [12]. By computing saddle points and transition paths, models can be developed that connect atomistic-scale interactions to the microstructural evolution observed in experiments, forming the core of a true multiscale modeling approach for inorganic crystal nucleation research.

The paradigm of crystal formation has expanded significantly beyond the confines of Classical Nucleation Theory. The established existence of non-classical pathways involving pre-nucleation clusters, amorphous intermediates, and particle-based assembly provides a more nuanced and accurate framework for understanding and controlling crystallization across materials science, geochemistry, and pharmaceutical development. Dendritic growth, particularly when integrated with mechanisms like oriented aggregation, exemplifies how these pathways can be harnessed to create materials with extreme and tailored properties, such as ultra-high aspect ratio single crystals.

Future research will likely focus on the intelligent design of polymers and additives to precisely direct crystallization along desired non-classical routes [20]. Furthermore, the tighter integration of advanced experimental characterization with powerful computational models, particularly those capable of handling complex, multi-step pathways on multiple length and time scales, will be crucial for building predictive capabilities. This will ultimately enable the rational design of crystalline materials, from highly selective zeolite catalysts to pharmaceuticals with optimized bioavailability, by mastering the full spectrum of crystallization pathways.

Computational Methodologies and Industrial Applications Across Scales

Understanding and controlling the nucleation and growth of inorganic crystals from aqueous solution represents a fundamental challenge in materials science, with significant implications for drug development and industrial applications. The process is inherently multiscale, spanning from the rapid, discrete interactions of atoms and molecules to the emergence of macroscopic crystal properties. Recent advances have revolutionized our understanding of these pathways, highlighting the role of pre-nucleation clusters and non-classical crystallization routes that deviate from traditional models [18] [13]. Multiscale modeling has emerged as a crucial tool for integrating these discoveries, enabling researchers to bridge quantum-level interactions with continuum-scale phenomena to design materials with tailored properties and functionalities.

The core challenge in modeling crystallization lies in the vast separation of time and length scales involved. Quantum mechanical events at the sub-nanometer scale, occurring in femtoseconds, ultimately dictate bulk material properties observable at the micrometer scale and beyond over seconds, hours, or days. No single computational method can efficiently span this entire spectrum. Consequently, a hierarchical approach that synergistically combines specialized modeling techniques at each scale is essential for a comprehensive understanding. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for constructing and applying such a hierarchy of modeling approaches within inorganic crystal nucleation research, presenting detailed methodologies, quantitative comparisons, and visualization tools for scientists and drug development professionals.

The Multiscale Modeling Hierarchy: Techniques and Integration

Multiscale modeling techniques for composite materials and chemical processes can be systematically classified into three primary categories based on their integration methodology: sequential, parallel, and synergistic methods [22]. In the context of inorganic crystal nucleation, these frameworks facilitate the seamless transfer of information across scales.

Sequential Methods: Also known as hierarchical methods, these employ a bottom-up approach where information from a finer scale is passed to a coarser scale, typically through homogenization. For example, atomistic simulation results can be used to parameterize a continuum model. This approach is efficient for studying systems where scales are weakly coupled.

Parallel Methods: These techniques, including concurrent methods, model different regions of a system simultaneously using different scales. The domain decomposition couples various scale models, such as embedding a quantum mechanical region within a molecular dynamics field, to focus computational resources on critical areas.

Synergistic Methods: These advanced frameworks involve a tight, iterative coupling between scales, allowing for bidirectional feedback. While computationally demanding, they offer the most accurate representation of systems where coarse-scale behavior influences fine-scale dynamics.

Table 1: Classification of Multiscale Modeling Approaches

| Method Category | Integration Logic | Key Advantage | Typical Application in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential (Hierarchical) | Information passes one-way from fine to coarse scale | Computational efficiency | Using DFT-calculated energy barriers to parameterize kinetic Monte Carlo models |

| Parallel (Concurrent) | Different scales model different regions simultaneously | High accuracy in critical regions | QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) modeling of solute-solvent interfaces |

| Synergistic | Tight, iterative coupling with bidirectional feedback | Captures cross-scale feedback loops | Adaptive resolution simulations where nucleation events trigger scale refinement |

Diagram: Information Flow in Sequential-Synergistic Hybrid Modeling

The Modeling Spectrum: From Quantum to Continuum

A comprehensive multiscale strategy for crystal nucleation employs a series of interlinked modeling techniques, each operating at its native scale.

Quantum Scale (Electronic Structure) At the finest scale, Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations reveal the quantum-level interactions between ions, molecules, and potential catalytic surfaces. DFT is indispensable for calculating activation energies for reaction steps, identifying stable intermediate complexes in solution, and modeling the electronic structure of early nucleation clusters [23]. These calculations provide fundamental parameters for coarser-scale models.

Atomistic Scale (Molecular Dynamics) Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations extend the scope to thousands or millions of atoms over nanoseconds, capturing the collective dynamics and solvation shells critical to nucleation. MD can simulate the aggregation of pre-nucleation clusters and the role of water entropy in driving crystallization [18]. Transition State Theory (TST) applied to MD trajectories helps quantify reaction rates for incorporation of ions into growing clusters [23].

Mesoscale (Stochastic and Statistical Methods) Bridging the atomistic and continuum scales, the Kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) method simulates the stochastic evolution of a crystal surface or the growth of a nucleus over much longer timescales than MD. KMC uses a catalog of possible events (e.g., adsorption, desorption, migration) and their DFT- or MD-derived rates to model time evolution [23]. Microkinetic Modeling provides a more coarse-grained approach, using a set of differential equations to describe the population dynamics of various species on a surface, often fed by DFT-calculated energetics [23].

Continuum Scale (Macroscopic Phenomena) At the macroscopic level, partial differential equations describe the transport of mass and energy within a crystallizer. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) models the hydrodynamics, temperature gradients, and concentration fields in a reactor, which directly impact supersaturation and hence nucleation and growth [23]. These models can incorporate population balance equations to track the evolving crystal size distribution, with growth and nucleation rates informed by lower-scale models.

Table 2: Modeling Techniques Across the Scales in Crystal Nucleation

| Scale & Model | Length Scale | Time Scale | Key Outputs for Nucleation Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT | Ångströms (Å) | Femtoseconds-Picoseconds | Reaction pathways, energy barriers, binding energies, electronic structure of clusters |

| MD | Nanometers (nm) | Nanoseconds-Microseconds | Pre-nucleation cluster dynamics, solute-solvent interactions, free energy landscapes |

| KMC | Nanometers-Micrometers (μm) | Microseconds-Seconds | Nucleation rates, crystal growth morphology, surface evolution |

| Microkinetics | Micrometers (μm) | Milliseconds-Seconds | Rate-determining steps, surface coverages, reaction rates |

| CFD | Millimeters-Meters (m) | Seconds-Hours | Reactor-scale supersaturation profiles, temperature distributions, mixing efficiency |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Density Functional Theory for Cluster Stability

Objective: To calculate the binding energy and structure of a putative calcium carbonate pre-nucleation cluster in aqueous solution.

System Preparation:

- Construct initial coordinates for a

Ca(CO3)2cluster (or other stoichiometry of interest). - Place the cluster in a periodic simulation box (e.g., 15×15×15 ų) and solvate it with explicit water molecules (e.g., ~100 H₂O molecules).

- Ensure a minimum distance of 10 Å between periodic images of the cluster to avoid spurious interactions.

- Construct initial coordinates for a

Computational Settings:

- Software: VASP, CP2K, or Quantum ESPRESSO.

- Functional: Use a generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional like PBE. Include van der Waals corrections (e.g., D3) to account for dispersion forces, which are critical in molecular aggregation.

- Basis Set/Pseudopotentials: Employ plane-wave basis sets with a kinetic energy cutoff of 400-500 eV and projector-augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials.

- Solvation: Implicit solvation models (e.g., VASPsol) can be used for initial screening, but explicit solvation is preferred for final, accurate results.

Calculation Workflow:

- Geometry Optimization: Fully relax the ion positions and cell shape until the forces on each atom are below 0.01 eV/Å.

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a vibrational frequency analysis on the optimized structure to confirm it is a minimum on the potential energy surface and to obtain thermodynamic corrections.

- Single-Point Energy: Calculate the total energy of the optimized cluster-solvent system,

E(total). - Reference Calculations: Perform identical calculations on the isolated ions (

Ca²⁺andCO3²⁻) in the same sized water box.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the binding energy,

ΔE(bind), using the formula:ΔE(bind) = E(total) - [E(Ca²⁺) + 2*E(CO3²⁻)]. - A negative

ΔE(bind)indicates a stable cluster. Analyze the electron density to characterize bonding.

- Calculate the binding energy,

Protocol: Kinetic Monte Carlo for Nucleation Kinetics

Objective: To simulate the time-dependent nucleation rate of a crystal from a supersaturated solution.

Lattice and Event Definition:

- Define a 3D lattice (e.g., 100×100×100 sites) to represent the simulation volume.

- Enumerate all possible processes ("events"): (1) Attachment of a solute unit to a lattice site adjacent to an existing cluster, (2) Detachment of a unit from a cluster, and (3) Diffusion of a unit along a cluster surface.

Rate Constant Assignment:

- Obtain the activation barriers (

E_a) for each event from MD simulations (e.g., using umbrella sampling) or DFT calculations. - Calculate the rate constant

kfor each event using Transition State Theory:k = (k_B*T/h) * exp(-E_a/(k_B*T)), wherek_Bis Boltzmann's constant,Tis temperature, andhis Planck's constant.

- Obtain the activation barriers (

KMC Algorithm:

- Step 1: Create a list of all possible events

iin the system and their corresponding ratesr_i. - Step 2: Calculate the cumulative rate

R = Σ r_i. - Step 3: Generate two random numbers

u1, u2between 0 and 1. - Step 4: Select the event

μto execute such thatΣ^(μ-1) r_i < u1*R ≤ Σ^(μ) r_i. - Step 5: Execute the event and update the system configuration and the list of possible events.

- Step 6: Advance the simulation clock by

Δt = -ln(u2)/R. - Step 7: Repeat from Step 1.

- Step 1: Create a list of all possible events

Data Analysis:

- Track the number and size of clusters as a function of simulation time.

- The nucleation rate is calculated from the steady-state slope of the number of super-critical clusters formed per unit volume per unit time.

Diagram: Sequential Multiscale Modeling Workflow for Crystal Nucleation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental validation of multiscale models requires precise control over crystallization. The following reagents and tools are essential for modern inorganic crystal nucleation research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Crystal Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Example in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Inorganic Salts | Source of ions for supersaturated solutions; minimizes interference from impurities. | CaCl₂ and Na₂CO₃ for calcium carbonate nucleation studies [18]. |

| Ultrapure Water (HPLC Grade) | Solvent medium; purity is critical to avoid heterogeneous nucleation on dust particles. | Used in all aqueous crystallization experiments to ensure reproducible nucleation kinetics. |

| Protic Ionic Liquids (PILs) | Advanced solvents that can lower energy barriers and modify crystal morphology. | Employed in potential-driven growth of metal crystals from solution [13]. |

| Microreactors / Continuous Flow Systems | Process intensification devices that enhance mixing, heat transfer, and provide uniform supersaturation. | Enables production of nanocrystals with narrow size distribution; improves nucleation rate control [13]. |

| Polymer Membranes | Act as structured heterogeneous nucleation interfaces in Membrane Crystallization (MCr). | MCr technology for desalination brine concentration and high-purity chemical production [13]. |

| Fast Scanning Chip Calorimetry (FSC) | Technique to study crystallization kinetics over a wide temperature range with high cooling/heating rates. | Used to study the bimodal temperature dependency of polyamide 11 crystallization [13]. |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, several challenges persist in the multiscale modeling of inorganic crystal nucleation. A primary issue is the computational expense of modeling efficiently and the trade-off between low-cost approaches and accurate predictions of material behavior [22]. While modeling tools like DFT, KMC, and CFD are well-developed individually, they often exhibit weaknesses in their linkage, and a comprehensive, fully integrated model is still lacking [23]. Another critical challenge is the representation of the interface between different phases, as the interfacial zone has a crucial determining effect on global composite properties, and its numerical representation must accurately interpret interfacial mechanics and bonding nature [22].

Future research will focus on overcoming these limitations through several promising avenues. The integration of cutting-edge experimental techniques like in situ microscopy and spectroscopy with computational models will provide real-time validation and refine model accuracy [13]. The development of synergistic multiscale frameworks that enable tighter, more efficient coupling between scales will move the field beyond the current sequential parameterization paradigm [22]. Furthermore, the application of machine learning potentials trained on DFT data can dramatically accelerate MD and KMC simulations, bridging the time-scale gap without sacrificing quantum-level accuracy. Finally, the experimental implementation of process intensification strategies like microreactors and membrane crystallization will continue to provide controlled environments for testing model predictions and achieving precise control over nucleation and growth [13]. The continued advancement along these paths will enable the rational design of crystals with bespoke properties for applications ranging from pharmaceutical development to advanced materials engineering.

Quantum-Accurate Molecular Dynamics (MD) with Machine-Learned Potentials

Understanding and controlling the atomistic mechanisms of inorganic crystal nucleation from supercooled liquids or glasses is a fundamental challenge in materials science. The initial stages of this process involve overcoming thermodynamic and kinetic barriers to form stable critical nuclei, events that occur at nanoscopic scales and picosecond resolutions, making them notoriously difficult to probe experimentally [24]. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, typically based on Density Functional Theory (DFT), provide the high accuracy needed to model these events but are computationally prohibitive for the required system sizes and time scales [25] [26]. This creates a critical bottleneck for in silico discovery and design of materials like glass-ceramics.

Machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a transformative solution, acting as surrogate models that achieve near-DFT accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [25] [26]. By learning the potential energy surface (PES) from reference DFT data, MLIPs enable quantum-accurate molecular dynamics simulations over larger spatial and temporal scales, thereby bridging a crucial gap in the multiscale modeling of crystal nucleation. This technical guide details the methodologies, workflows, and tools required to develop and deploy MLIPs for this specific, demanding application.

Core Concepts: Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials

Under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the potential energy of an atomic system is a function of the nuclear coordinates and atomic numbers. MLIPs learn this functional relationship from quantum mechanical data. A standard formalism expresses the total energy (E) as a sum of local, atom-wise contributions [26]:

[ E = \sum{i} E{i} ]

Each atomic energy (E{i}) is inferred from a mathematical descriptor that captures the local chemical environment of atom (i), ensuring model invariance to translation, rotation, and permutation of like atoms. Atomic forces ((\vec{fi})) are then calculated as the negative gradient of the total energy with respect to atomic positions, which is critical for MD simulations [26]:

[ \vec{fi} = -\nabla{\vec{x_i}}E ]

The accuracy of an MLIP hinges on the quality of its descriptors, the size and diversity of its training set, and the model's capacity to capture complex atomic interactions [25].

A Workflow for Developing and Deploying Quantum-Accurate MLIPs

Constructing a robust MLIP for studying rare events like crystal nucleation requires a meticulous, iterative workflow focused on sampling relevant configurations.

Workflow Diagram: MLIP Development for Nucleation Studies

The following diagram outlines the core iterative cycle for developing a reliable MLIP, with a particular focus on capturing the transition states relevant to crystal nucleation.

Key Methodological Components

Initial Configuration Sampling with AIMD: The workflow begins by running short, computationally expensive AIMD simulations on a small system. For nucleation studies, this should be performed on the supercooled liquid or glass phase at the temperature and pressure of interest to capture pre-nucleation clusters and local structural motifs [27].

Active Learning and Training Set Construction: A critical challenge is ensuring the training data encompasses all relevant local environments the system will explore during long-time MLIP-MD, including high-energy transition states during nucleation. An active learning loop is essential [25].

- Strategy: After initial MLIP training, the model is used to run MD simulations. Configurations where the model's uncertainty is high (often estimated by committee models or other metrics) are selected for DFT single-point calculations to obtain accurate energies and forces, which are then added to the training set [25].

- Structured Descriptor Tracking: For complex materials like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) or multi-component glasses, tracking the diversity of the training set using structural descriptors—such as unit cell parameters, bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals (CBAD)—ensures all relevant local environments are represented, creating a balanced and comprehensive training set [25].

Validation and Nucleation Analysis: The validated MLIP enables nanosecond-scale MD simulations to observe nucleation events directly. Key analyses include:

- Free Energy Calculation: Methods like the Free-Energy Seeding Method (FESM) can be used. This involves embedding a spherical crystal cluster of varying radius (r) in the glass model and computing the associated free energy change (\Delta G(r)), allowing for the identification of the critical nucleus size (r^) and nucleation barrier (W^) [27]: [ \Delta G(r) = 4\pi r^2\sigma - \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3\rho|\Delta\mu| ]

- Structural Analysis: Algorithms to identify and characterize crystal-like atoms or embryos within the amorphous matrix are used to track the evolution and structure of nuclei over time [27].

Case Study: Crystal Nucleation in a Lithium Disilicate Glass

A study on lithium disilicate (LS2) glass exemplifies the application of MLIPs (in this case, a classical forcefield was used, but the methodology is directly transferable to MLIPs) to unravel complex nucleation mechanisms [27].

- Objective: Resolve the long-standing debate on whether the stable Li₂Si₂O₅ (LS2) crystal nucleates directly or via a metastable Li₂SiO₃ (LS) precursor phase.

- Methodology:

- Embryo Searching: A specialized algorithm scanned bulk and surface glass models to identify pre-structured crystalline embryos.

- Free-Energy Seeding (FESM): The free energy change as a function of crystal cluster radius was computed for both LS and LS2 crystals embedded in the glassy matrix.

- Key Findings: The study identified embryos of both LS2 and LS crystals. Notably, LS embryos were predominantly found on the glass surface, while LS2 formed in the bulk. The free energy profiles for both exhibited the maximum predicted by Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT), with critical sizes and barrier heights agreeing well with experimental data [27]. This provided atomistic validation of CNT for this system and clarified the nucleation pathway.

The development of accurate MLIPs relies on large-scale, high-quality datasets and robust, flexible software frameworks.

Public Datasets for Training MLIPs

The table below summarizes key datasets containing quantum chemistry calculations suitable for training MLIPs.

Table 1: Key Quantum Chemistry Datasets for MLIP Training.

| Dataset | Description | Content Highlights | Relevance to Nucleation Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChemQCR [26] | Largest public dataset of DFT relaxation trajectories for small organic molecules. | ~3.5M trajectories, ~300M conformations with energy and force labels. | Contains off-equilibrium conformations crucial for learning the full PES. |

| QM7-X [26] | Extension of the QM7 dataset. | ~4.2M conformations for ~7,000 molecules with force labels. | Limited to 7 heavy atoms but provides diverse conformational data. |