Multi-Objective Optimization in Molecular Generation: AI-Driven Strategies for Balanced Drug Design

The design of novel drug candidates necessitates balancing multiple, often competing, molecular properties such as potency, selectivity, metabolic stability, and low toxicity.

Multi-Objective Optimization in Molecular Generation: AI-Driven Strategies for Balanced Drug Design

Abstract

The design of novel drug candidates necessitates balancing multiple, often competing, molecular properties such as potency, selectivity, metabolic stability, and low toxicity. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of state-of-the-art artificial intelligence methodologies for multi-objective molecular optimization. We explore foundational concepts, a diverse landscape of computational techniques—including evolutionary algorithms, reinforcement learning, and latent space optimization—and their practical applications in de novo drug design. The content further addresses critical challenges such as handling constraints and avoiding local optima, and provides a rigorous comparative evaluation of current methods based on benchmarks like the Pareto front and success rate. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how these advanced computational strategies are revolutionizing the search for optimally balanced therapeutic molecules, thereby accelerating the drug discovery pipeline.

The Imperative for Multi-Objective Optimization in Modern Drug Discovery

Drug discovery necessitates the simultaneous improvement of multiple, often conflicting, molecular properties. While single-objective optimization (SingleOOP) offers a straightforward approach for optimizing one property, it fundamentally misrepresents the complex nature of designing a viable drug candidate. This application note delineates the theoretical and practical limitations of SingleOOP in drug design. It further presents detailed protocols for implementing multi-objective and many-objective optimization frameworks, which are more adept at identifying molecules that represent a balanced compromise between essential pharmacological characteristics.

The primary goal of de novo drug design (dnDD) is to create novel molecular compounds from scratch that satisfy a multitude of desired properties [1]. A successful drug candidate must exhibit high potency against a specific biological target, possess a favorable pharmacokinetic profile (encompassing absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion), demonstrate low toxicity, and have reasonable synthetic accessibility [1] [2]. These properties are often conflicting; for example, increasing molecular weight to improve binding affinity might adversely affect solubility or permeability [1].

Single-objective optimization methods are designed to find the optimal solution for a single metric, which is an oversimplification of this complex, multi-faceted challenge [3] [4]. This note details why SingleOOP is inadequate for modern drug discovery and provides robust methodological frameworks for the superior multi-objective approach.

Key Limitations of Single-Objective Optimization

The application of SingleOOP to drug design introduces several critical shortcomings:

- Oversimplification of Goals: SingleOOP cannot natively handle multiple objectives. The common workaround, scalarization, involves aggregating multiple properties into a single weighted-sum function (e.g.,

f = w1 * Potency + w2 * QED - w3 * Toxicity) [3] [4]. This approach is highly sensitive to the chosen weights and risks biasing the optimization campaign towards a suboptimal region of the chemical space [3]. - Lack of Trade-off Analysis: SingleOOP yields a single "best" solution, providing no insight into the alternative compromises between objectives [3] [4]. In contrast, multi-objective optimization (MultiOOP) identifies a Pareto front—a set of non-dominated solutions where improvement in one objective leads to deterioration in another [1] [3]. This allows researchers to make informed decisions based on project priorities.

- Inability to Navigate Complex Constraints: Practical drug design requires adherence to stringent drug-like constraints, such as specific ring sizes or the absence of problematic substructures [5]. SingleOOP typically handles these via penalty functions in the objective, which can be inefficient. Multi-objective frameworks can dynamically balance objective optimization with constraint satisfaction [5].

Table 1: Core Deficiencies of Single-Objective Optimization in Drug Design

| Deficiency | Impact on Drug Design Process |

|---|---|

| Oversimplification via Scalarization | Leads to molecules that are optimal only for an arbitrary weighted function, not necessarily viable as drugs. Weight tuning is non-trivial and can bias results [3]. |

| Provides a Single Solution | Fails to reveal the landscape of possible compromises (e.g., how much potency must be sacrificed for a significant reduction in toxicity). Limits options for lead selection [4]. |

| Poor Handling of Constraints | Treats hard chemical constraints as soft penalties, potentially generating chemically infeasible or unstable molecules that must be filtered out later [5]. |

| Neglects the "Many-Objective" Reality | Drug design is often a "many-objective" problem (>3 objectives), involving potency, multiple ADMET properties, synthesizability, and cost. SingleOOP is fundamentally unsuited for this [1] [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization

This section outlines protocols for two advanced computational methods that effectively address the multi-objective challenge in drug design.

Protocol: Constrained Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization (CMOMO)

The CMOMO framework is designed to balance the optimization of multiple properties with the satisfaction of critical drug-like constraints [5].

- Objective: To identify molecules with improved multi-property profiles while strictly adhering to predefined structural and chemical constraints.

Materials:

- Lead Molecule: A starting compound, represented as a SMILES string.

- Pre-trained Molecular Encoder-Decoder: A model (e.g., based on VAEs or Transformers) to map molecules to a continuous latent space and back [5].

- Property Prediction Models: QSAR models or deep learning networks to predict objective properties (e.g., QED, binding affinity, toxicity) [5].

- Constraint Definitions: Explicit mathematical definitions of constraints (e.g.,

5 ≤ Number_of_Rings ≤ 7).

Procedure:

- Population Initialization:

a. Encode the lead molecule into its latent vector representation,

z_lead. b. Construct a "Bank" library of high-property molecules similar to the lead from a public database and encode them. c. Generate an initial population by performing linear crossover betweenz_leadand the latent vectors of molecules in the Bank library [5]. - Dynamic Cooperative Optimization: a. Stage 1 - Unconstrained Scenario: Optimize the population in the latent space for the multiple objectives (e.g., using an evolutionary algorithm) without considering constraints. The goal is to rapidly explore the chemical space for high-performance regions [5]. b. Stage 2 - Constrained Scenario: Switch to a constrained optimization mode. Solutions are evaluated based on both their objective performance and their constraint violation (CV) value. The framework uses a dynamic constraint handling strategy to balance the drive for better properties with the need to satisfy all constraints [5]. c. Evolutionary Reproduction: Employ the Vector Fragmentation-based Evolutionary Reproduction (VFER) strategy. This involves splitting latent vectors into fragments and recombining them to generate novel offspring molecules, enhancing search efficiency [5].

- Evaluation and Selection: a. Decode the latent vectors of offspring molecules back to SMILES strings using the pre-trained decoder. b. Validate the chemical structures and filter out invalid molecules using a toolkit like RDKit. c. Calculate the objective values and CV values for each valid molecule. d. Select the best molecules for the next generation based on a multi-objective selection criterion (e.g., non-dominated sorting) [5].

- Termination: Repeat steps 2-3 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of generations or convergence of the Pareto front).

- Output: A set of Pareto-optimal molecules that represent the best trade-offs between the multiple objectives while adhering to all constraints.

- Population Initialization:

a. Encode the lead molecule into its latent vector representation,

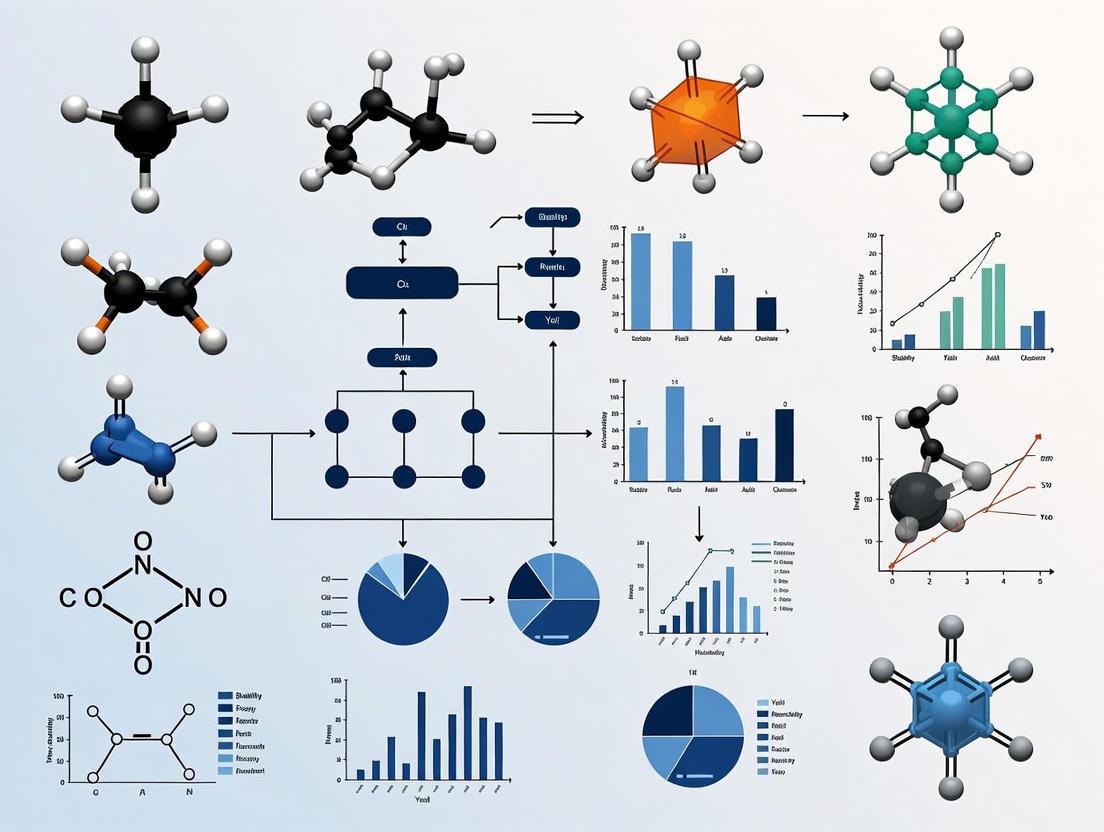

The following workflow diagram illustrates the two-stage CMOMO process:

Protocol: Many-Objective Optimization with Transformers and Evolutionary Algorithms

This protocol integrates a latent Transformer model for molecular generation with many-objective metaheuristics to handle more than three objectives simultaneously [2].

- Objective: To generate novel drug candidates optimized for four or more objectives, such as binding affinity and key ADMET properties.

Materials:

- Generative Transformer Model: A model like ReLSO or FragNet, which provides an organized latent space for molecular representation and generation [2].

- Many-Objective Metaheuristics: Optimization algorithms such as MOEA/DD (Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Dominance and Decomposition) or PSO (Particle Swarm Optimization) [2].

- Molecular Docking Software: e.g., AutoDock Vina, for estimating binding affinity.

- ADMET Prediction Suite: Software or models for predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties.

Procedure:

- Model Selection and Training: Train or fine-tune a latent Transformer model (e.g., ReLSO) on a large corpus of chemical structures (e.g., SMILES or SELFIES strings) to ensure it can accurately reconstruct and generate valid molecules [2].

- Define Objective Space: Specify the four or more objectives for optimization (e.g.,

[Docking_Score, QED, Synthetic_Accessibility_Score, Toxicity_Score, HBA_Count]). - Initialization: Generate an initial population of molecules by sampling points from the well-structured latent space of the Transformer model and decoding them.

- Many-Objective Search: a. Encode the population of molecules into the latent space. b. Use a many-objective metaheuristic (e.g., MOEA/DD) to evolve the population of latent vectors. c. The metaheuristic's goal is to maximize the hypervolume of the objective space, which ensures the expansion of the Pareto front and promotes diversity among solutions [2] [3].

- Evaluation: a. For each generation, decode the latent vectors of candidate molecules. b. Employ docking simulations and ADMET prediction models to evaluate each molecule against the defined objectives.

- Termination and Analysis: Continue the search until the hypervolume indicator converges. The final output is a diverse set of non-dominated molecules, providing multiple candidate options for downstream experimental validation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Objective Drug Design

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Validates chemical structures, calculates molecular descriptors (e.g., MW, LogP, HBD), and handles molecular fingerprints [5]. |

| Transformer Autoencoder (e.g., ReLSO) | Deep Learning Model | Creates a continuous, organized latent representation of molecules, enabling efficient search and optimization in a lower-dimensional space [2]. |

| Evolutionary Algorithm (e.g., MOEA/DD) | Optimization Algorithm | Drives the search for Pareto-optimal solutions by evolving a population of candidate molecules in the latent or chemical space [2] [5]. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Simulation Tool | Predicts the binding affinity and mode of a molecule to a protein target, a key objective for potency [2]. |

| ADMET Prediction Model | Predictive AI Model | Estimates key pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles of generated molecules, crucial for avoiding clinical failure [2]. |

| ZINC/ChEMBL Databases | Chemical Database | Provides source data for pre-training generative models and constructing "Bank" libraries for population initialization [5]. |

Single-objective optimization provides a conceptually simple but practically inadequate framework for the complex challenge of drug design. Its inability to represent and navigate the inherent trade-offs between multiple, conflicting objectives limits its utility in discovering viable, well-balanced drug candidates. The experimental protocols outlined for CMOMO and many-objective optimization with Transformers provide robust, scalable, and practical frameworks for the research community. By adopting these multi-objective paradigms, scientists can more effectively explore the vast chemical space and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutics.

Molecular discovery, particularly in drug development, is fundamentally a multi-objective optimization problem. The goal is to identify molecules that simultaneously excel at multiple, often competing, properties—such as binding affinity for a target protein, minimal off-target interactions, and favorable pharmacokinetic profiles [6]. Pareto optimality, a concept named after the economist Vilfredo Pareto, provides a powerful framework for tackling these problems. A state is Pareto optimal if no alternative state exists where at least one participant's well-being is higher and nobody else's well-being is lower [7]. In the context of molecular design, a molecule is considered Pareto optimal if it lies on the Pareto front—the set of solutions for which improving one objective (e.g., binding affinity) necessarily leads to the deterioration of at least one other objective (e.g., synthetic accessibility) [6] [7]. This front defines the ultimate trade-off frontier in chemical space, illustrating the best possible compromises between competing goals. Unlike scalarization methods that combine multiple objectives into a single score using predefined weights, Pareto optimization reveals the entire set of optimal trade-offs, empowering researchers to make informed decisions without prior commitment to the relative importance of each property [6].

Methodological Approaches for Pareto Optimization

Navigating the high-dimensional chemical space to uncover the Pareto front requires sophisticated computational strategies. These methods can be broadly categorized into Bayesian optimization, evolutionary algorithms, and other metaheuristics, each with distinct mechanisms for balancing exploration and exploitation.

Bayesian Optimization and Active Learning

Bayesian optimization is particularly well-suited for multi-objective virtual screening when property evaluations (e.g., docking scores) are computationally expensive. This approach uses surrogate models, such as Gaussian processes, to predict objective functions across a virtual library. An acquisition function then guides the selection of the most promising molecules to evaluate next, dramatically reducing the number of full computations required.

- Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions: Extensions of single-objective acquisition functions are used for Pareto optimization.

- Probability of Hypervolume Improvement (PHI): Estimates the likelihood that evaluating a new molecule will increase the total hypervolume dominated by the Pareto front.

- Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHI): Estimates the expected amount by which the hypervolume will increase upon evaluating a new molecule.

- Non-Dominated Sorting (NDS): Ranks molecules based on their Pareto front, giving priority to those on the best non-dominated fronts [6].

- Implementation with MolPAL: The tool MolPAL implements a pool-based active learning workflow for multi-objective virtual screening. It begins by calculating objective values for a small, initial subset of a virtual library. Surrogate models are trained on these observations and used to predict objectives for all candidate molecules. A multi-objective acquisition function selects a batch of promising molecules for full evaluation, the surrogate models are retrained, and the loop repeats. This method has been shown to acquire 100% of the Pareto front after exploring only 8% of a 4-million-molecule library in a search for selective dual inhibitors [6].

Evolutionary and Fragment-Based Algorithms

Evolutionary algorithms leverage principles of natural selection—mating, mutation, and selection—to evolve a population of molecules toward the Pareto front over multiple generations.

- CMOMO (Constrained Molecular Multi-objective Optimization): This framework specifically addresses the challenge of optimizing multiple properties while satisfying strict drug-like constraints (e.g., ring size, substructure alerts). CMOMO employs a two-stage dynamic optimization process:

- Unconstrained Scenario: It first performs multi-objective optimization in an unconstrained latent space to find molecules with excellent property values.

- Constrained Scenario: It then considers both properties and constraints to identify feasible molecules that retain promising properties. This is achieved through a latent vector fragmentation-based evolutionary reproduction (VFER) strategy for efficient optimization in a continuous implicit space [5].

- STELLA (Systematic Tool for Evolutionary Lead optimization Leveraging Artificial intelligence): STELLA combines an evolutionary algorithm for fragment-based chemical space exploration with a clustering-based conformational space annealing (CSA) method. Its workflow involves:

- Initialization: Generating an initial pool from a seed molecule using fragment-based mutation (FRAGRANCE).

- Molecule Generation: Creating variants via FRAGRANCE mutation, maximum common substructure (MCS)-based crossover, and trimming.

- Scoring: Evaluating molecules with a user-defined objective function.

- Clustering-based Selection: Selecting top-scoring molecules from each cluster to maintain diversity. The distance cutoff for clustering is progressively reduced, shifting the focus from exploration to exploitation over successive cycles [8].

Monte Carlo Tree Search and LLM-Driven Frameworks

- PMMG (Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search Molecular Generation): PMMG integrates a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) molecular generator with a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) guided by the Pareto principle. The MCTS iteratively performs four steps:

- Selection: Traversing the tree from the root by selecting nodes with the highest Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) score.

- Expansion: Adding new child nodes (potential molecular actions) to the tree.

- Simulation: Running a randomized simulation (using the RNN) from the new node to a terminal state (complete molecule) to estimate its value.

- Backpropagation: Updating the node statistics in the path with the simulation results, propagating the multi-objective rewards back up the tree. This allows PMMG to efficiently explore high-dimensional objective spaces, achieving a 51.65% success rate in simultaneously optimizing seven distinct objectives [9].

- MOLLM (Multi-Objective Large Language Model): This framework leverages the domain knowledge and in-context learning capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) for multi-objective molecular optimization. MOLLM uses an LLM as a mating operator within a genetic algorithm framework, generating novel molecules through prompt engineering that incorporates parent molecules and optimization instructions, without requiring additional task-specific training [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Objective Optimization Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MolPAL [6] | Bayesian Optimization & Active Learning | Pool-based screening, multi-objective acquisition functions (PHI, EHI, NDS) | Identified 100% of Pareto front after evaluating 8% of a 4M-member library. |

| CMOMO [5] | Evolutionary Algorithm (Two-Stage) | Dynamic constraint handling, latent space optimization (VFER strategy) | Two-fold improvement in success rate for GSK3 optimization task vs. benchmarks. |

| STELLA [8] | Evolutionary Algorithm & Clustering | Fragment-based exploration, clustering-based conformational space annealing | Generated 217% more hit candidates with 161% more unique scaffolds vs. REINVENT 4. |

| PMMG [9] | Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) | MCTS with RNN generator, direct Pareto front search in high-dimensional space | 51.65% success rate for 7 objectives; Hypervolume (HV) of 0.569. |

| MOLLM [10] | Large Language Model (LLM) | In-context learning, no additional training, acts as an intelligent crossover/mutation operator | Outperformed state-of-the-art GA, BO, and RL models, especially with more objectives. |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Objective Virtual Screening for Selective Inhibitors with MolPAL

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying selective dual inhibitors of EGFR and IGF1R from the Enamine Screening Collection (4M+ molecules) using docking scores as objectives [6].

1. Objective Definition: * Primary Objective (f₁): Docking score against the primary target (e.g., EGFR). To be minimized. * Selectivity Objective (f₂): Difference between docking scores for on-target (EGFR) and off-target (e.g., IGF1R). To be maximized. * Note: Objectives can be redefined as maximization problems for consistency with Pareto front literature.

2. Software and Library Setup: * Virtual Library: Prepare the SMILES strings and 3D conformers for the Enamine Screening Collection. * Docking Software: Configure molecular docking software (e.g., GOLD, AutoDock Vina) for both EGFR and IGF1R protein structures. * MolPAL: Install the open-source MolPAL package.

3. Initialization and Surrogate Model Training: * Initial Batch: Randomly select a small subset (e.g., 0.1% of the library) and calculate docking scores for all defined objectives. * Model Training: Train initial surrogate models (e.g., Random Forest or Gaussian Process models) for each objective using the initial batch's molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) as features and the docking scores as labels.

4. Iterative Bayesian Optimization Loop:

* Prediction: Use the trained surrogate models to predict the mean (μ(x)) and uncertainty (σ(x)) for all unevaluated molecules in the library.

* Acquisition: Calculate a multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., Expected Hypervolume Improvement - EHI) for all unevaluated molecules.

* Selection: Select the top k molecules (e.g., batch size of 128-256) with the highest acquisition scores.

* Evaluation: Perform full docking calculations for the selected batch against all targets to obtain the true objective values.

* Update: Append the new data (molecules and their true scores) to the training set and retrain the surrogate models.

* Repeat steps a-e for a fixed number of iterations or until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., hypervolume change < threshold).

5. Post-Processing and Analysis: * Pareto Front Identification: Apply non-dominated sorting to all evaluated molecules to identify the final Pareto front. * Hit Selection: Analyze the molecules on the Pareto front for their balanced profile of high EGFR affinity and selectivity over IGF1R.

Protocol 2: Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization with CMOMO

This protocol details the use of CMOMO for optimizing multiple molecular properties while adhering to strict structural or drug-like constraints [5].

1. Problem Formulation:

* Objectives (f(x)): Define properties to optimize (e.g., Bioactivity, QED, Synthetic Accessibility Score).

* Constraints (g(x), h(x)): Define hard constraints (e.g., Ring_Size != 3, Molecular_Weight < 500, presence/absence of specific substructures).

2. Initialization and Bank Library Construction: * Lead Molecule: Input the SMILES string of the lead compound. * Bank Library: Construct a library of molecules structurally similar to the lead from a public database (e.g., ZINC). * Encoder: Use a pre-trained molecular encoder (e.g., JT-VAE) to embed the lead and all Bank library molecules into a continuous latent space. * Initial Population: Generate an initial population by performing linear crossover between the latent vector of the lead molecule and those of molecules in the Bank library. Decode these latent vectors to obtain the initial SMILES population.

3. Dynamic Cooperative Optimization: This stage runs in two phases: unconstrained optimization followed by constrained optimization. * A. VFER Reproduction (in Latent Space): Apply the Vector Fragmentation-based Evolutionary Reproduction (VFER) strategy to the parent population to generate offspring in the latent space. * B. Decoding and Validation: Decode the parent and offspring latent vectors back to SMILES strings. Use RDKit to validate molecular structures and filter out invalid ones. * C. Objective and Constraint Evaluation: Calculate all objective functions and constraint violation (CV) values for the valid molecules. * D. Environmental Selection: * Phase 1 (Unconstrained): Select the best molecules based solely on their multi-objective performance (e.g., using non-dominated sorting and crowding distance). * Phase 2 (Constrained): Prioritize feasible molecules (CV=0) with good objective values. Use a dynamic constraint-handling mechanism to balance property optimization and constraint satisfaction. * Repeat steps A-D for a predefined number of generations.

4. Result Analysis: * The final output is a set of Pareto-optimal molecules that represent the best trade-offs between the multiple objectives while satisfying all defined constraints.

Table 2: Key Software and Resources for Pareto Optimization in Molecular Design

| Category | Item / Software | Primary Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Frameworks | MolPAL [6] | Open-source Python tool for pool-based active learning and multi-objective Bayesian optimization. | Ideal for large-scale virtual screening campaigns to reduce docking computation cost. |

| CMOMO [5] | A deep multi-objective optimization framework with dynamic constraint handling. | Best for problems with strict, hard constraints (e.g., structural alerts, ring size). | |

| STELLA [8] | A metaheuristics-based framework combining evolutionary algorithms and clustering-based CSA. | Excels in fragment-level chemical space exploration and generating diverse scaffolds. | |

| Molecular Generators | PMMG [9] | Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search Molecular Generation. | Effective for navigating very high-dimensional objective spaces (e.g., 7+ objectives). |

| MOLLM [10] | Multi-Objective Large Language Model using in-context learning. | Leverages pre-trained chemical knowledge without fine-tuning; useful as an intelligent operator. | |

| Property Prediction & Evaluation | Molecular Docking Software (e.g., GOLD, AutoDock Vina) [8] | Predicts binding affinity and pose of a ligand to a protein target. | Used as an expensive objective function evaluator in virtual screening. |

| RDKit [5] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used for fundamental operations: SMILES validation, fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation. | |

| QED, SA_Score, etc. | Calculates quantitative estimate of drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility score. | Standard objectives for ensuring generated molecules are drug-like and synthesizable. | |

| Data & Representations | ZINC Database [10] | Publicly available database of commercially available compounds. | Source for initial molecules and for constructing seed libraries. |

| SMILES / SELFIES [10] | String-based representations of molecular structure. | Standard representations for most generative models. | |

| Molecular Fingerprints (eCFP) [6] | Fixed-length vector representations of molecular structure. | Used as features for surrogate models in Bayesian optimization. |

The principal challenge in modern drug discovery lies in designing novel small-molecule therapeutics that successfully balance multiple, often competing, pharmacological properties. A compound must demonstrate not only strong binding affinity for its intended target but also possess favorable drug-like qualities, including appropriate lipophilicity (LogP), high quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), and low toxicity profiles. The pursuit of molecules active against multiple targets further complicates this optimization landscape. Traditional sequential optimization methods are often inadequate for navigating this complex trade-off space, making multi-objective optimization (MOO) not merely an enhancement but a necessity for efficient drug discovery [11] [12].

This Application Note details the computational methodologies and experimental protocols for implementing multi-objective optimization in molecular generative modeling. It provides a structured framework for researchers to generate de novo compounds predicted to exhibit an optimal balance between conflicting properties such as binding affinity, QED, LogP, and toxicity, even when working with limited public data [11] [13].

Key Properties and Quantitative Benchmarks

A critical first step in multi-objective optimization is defining the key properties and their target values. The table below summarizes the primary objectives discussed in this note and their quantitative benchmarks for drug-like molecules.

Table 1: Key Molecular Properties in Multi-Objective Optimization

| Property | Description | Optimization Goal | Typical Drug-like Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity | Strength of interaction with a protein target, often predicted by docking scores or QSAR models [13]. | Maximize (e.g., higher docking score indicates stronger binding) [12] | N/A (Target-dependent) |

| QED | Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness; a unified measure combining several desirable properties [12]. | Maximize (Closer to 1.0 is more drug-like) | 0 to 1 (Higher is better) |

| LogP | Partition coefficient measuring lipophilicity; critical for membrane permeability and solubility [12]. | Optimize to a specific range | -0.4 to +5.6 [12] |

| Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score | Estimate of how easily a molecule can be synthesized [12]. | Minimize (Easier to synthesize) | 1 to 10 (Lower is better) |

| NP-likeness | Score indicating similarity to natural products, which can be favorable [12]. | Maximize | N/A (Higher is better) |

Computational Methodologies for Multi-Objective Optimization

Several advanced computational strategies have been developed to navigate the high-dimensional chemical space and balance the properties outlined in Table 1.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) with Generative Models

Reinforcement learning frameworks train a generative model to produce molecules with desired properties by using a scoring function as a reward. The SGPT-RL method exemplifies this approach, using a Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) as the policy network [13].

- Workflow: A prior model is first pre-trained on a large dataset of drug-like molecules (e.g., the MOSES benchmark dataset) to learn the general chemical space. This model is then fine-tuned via RL, where it generates molecules, receives a reward based on a multi-property scoring function, and updates its parameters to increase the likelihood of generating high-scoring compounds [13].

- Application: This method has shown success in optimizing for binding affinity using both QSAR models and molecular docking as scoring functions, achieving superior results in tasks like generating inhibitors for the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) [13].

Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)

For explicit multi-objective optimization, Pareto MCTS provides a powerful solution for discovering molecules on the Pareto front—the set of solutions where no single objective can be improved without worsening another [12].

- Workflow: The algorithm, implemented in tools like ParetoDrug, performs an atom-by-atom search through chemical space. It uses a pretrained autoregressive generative model to guide the search and a novel selection scheme (ParetoPUCT) to balance the exploration of new regions with the exploitation of known high-scoring molecular fragments [12].

- Application: This method is particularly effective for multi-target multi-objective drug discovery, such as designing dual-inhibitor compounds like Lapatinib, where affinity for multiple targets must be balanced with other drug-like properties [12].

Multi-Objective Latent Space Optimization (LSO)

This approach enhances generative models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) by optimizing in the continuous, low-dimensional latent space of the model.

- Workflow: An iterative weighted retraining process is used. Molecules are generated and ranked based on their Pareto efficiency, which then determines their weight in the subsequent retraining of the generative model. This effectively biases the model towards regions of the chemical space containing Pareto-optimal molecules [14].

- Application: This method has demonstrated a significant improvement in the joint optimization of multiple molecular properties, pushing the Pareto front for a given set of objectives [14].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for a multi-objective optimization campaign using a reinforcement learning approach, which can be adapted to other methodologies.

Protocol 1: Multi-Objective Optimization via Reinforcement Learning

Objective: To generate novel molecules with optimized binding affinity (docking score), QED, and LogP.

Materials & Computational Tools:

- Hardware: Computer workstation with a high-performance GPU (e.g., NVIDIA A100 or equivalent) for efficient model training and docking simulations [13].

- Software & Libraries:

- SGPT-RL or REINVENT software framework [13] [12].

- Molecular Docking Software: Smina, for calculating binding affinity scores [12].

- Cheminformatics Library: RDKit, for calculating QED, LogP, and other physicochemical properties [12].

- Programming Environment: Python 3.8+ with deep learning libraries (PyTorch/TensorFlow).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation

- Obtain a dataset of drug-like molecules for pre-training, such as the ~1.9 million lead-like molecules from the MOSES benchmark [13].

- For the target of interest (e.g., ACE2), gather a set of known active molecules from public databases like ChEMBL or ExCAPE-DB to validate the optimization process [13].

Prior Model Pre-training

- Train a generative model (e.g., a Generative Pre-trained Transformer, GPT) on the MOSES dataset. The objective is for the model to learn the syntax of molecular representations (SMILES) and the distribution of drug-like chemical space.

- Validate the model by generating a set of molecules and checking for validity, uniqueness, and novelty against the training set [13].

Define the Multi-Objective Scoring Function

- Develop a composite scoring function,

S(m), that combines the target properties. For example:S(m) = w1 * Docking_Score(m) + w2 * QED(m) + w3 * (1 - |LogP(m) - 3|) - Here,

w1,w2, andw3are weights that reflect the relative importance of each objective. The LogP term is structured to penalize deviation from an ideal value (e.g., 3). All objectives should be normalized to a common scale.

- Develop a composite scoring function,

Reinforcement Learning Fine-Tuning

- Initialize the RL agent with the pre-trained prior model.

- For each training step:

a. The agent generates a batch of molecules (e.g., 100-1000).

b. For each valid molecule, compute the multi-objective score

S(m). c. The agent's policy is updated using a policy gradient method (e.g., PPO) to maximize the expected rewardS(m), often tempered by a prior likelihood term to prevent excessive deviation from drug-like chemical space [13]. - Monitor the training by tracking the scores of generated molecules over time.

Validation and Analysis

- Select top-scoring generated molecules for further in silico validation.

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability.

- Evaluate synthetic accessibility and potential off-target effects using specialized tools.

- Propose the most promising candidates for in vitro synthesis and biochemical assay testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Brief Description of Role |

|---|---|---|

| Smina | Docking Software | Used for structure-based virtual screening to calculate binding affinity (docking score) of generated molecules [12]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | An open-source toolkit used for calculating molecular descriptors (LogP), drug-likeness (QED), and handling molecular operations [12]. |

| GPT / MolGPT | Generative Model | A transformer-based architecture that serves as the core engine for generating novel molecular structures, often used as a prior model in RL [13] [12]. |

| REINVENT | Reinforcement Learning Framework | A popular RL framework for benchmark comparisons in goal-directed molecular generation [13]. |

| ParetoDrug | Multi-objective Optimization Algorithm | An algorithm using Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search to explicitly find molecules on the Pareto front for multiple objectives [12]. |

| PyMOL/Chimera | 3D Visualization Tool | Critical for visually analyzing and interpreting the predicted binding modes of generated compounds within the protein target's active site [15]. |

| R Shiny / Spotfire | Interactive Dashboard | Platforms for building custom interactive applications to explore and analyze the multi-dimensional data from the optimization campaign [15]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for multi-objective molecular optimization, combining the methodologies and protocols described in this note.

Diagram 1: Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization Workflow. The process integrates data preparation, iterative model training, and multi-property evaluation to identify optimal compounds.

The pursuit of novel therapeutic compounds requires navigation of an almost inconceivably vast chemical space, estimated to contain approximately 10^60 pharmacologically sensible molecules [16]. This enormity presents a fundamental challenge in drug discovery, as synthesizing and testing even a minute fraction of these candidates is computationally and practically intractable [16]. Modern drug discovery further complicates this task by aiming to design compounds that actively engage multiple targets, necessitating a careful balance between often-conflicting properties such as potency, safety, metabolic stability, and pharmacodynamic profile [11]. This Application Note details how computational methodologies, particularly multi-objective optimization (MOO), are leveraged to navigate this expansive search space and generate novel small molecules optimized for complex, multi-faceted pharmacological requirements.

Quantitative Characterization of Chemical Space

Understanding the scale and composition of chemical space is a critical first step in developing strategies to explore it. The table below summarizes key concepts and quantitative measures.

Table 1: Characterization of Chemical Space for Drug Discovery

| Aspect | Description | Estimated Size/Figure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Drug-like Space | Space of potential pharmacologically active molecules (C, H, O, N, S, MW < 500). | ~10^60 molecules | [16] |

| Known Chemical Space | Molecules reported in literature and assigned a CAS Registry Number. | ~219 million molecules (as of 2024) | [16] |

| Annotated Bioactive Space | Distinct molecules with recorded biological activities in the ChEMBL database. | ~2.4 million molecules | [16] |

| Key Concept | Description | Application | Reference |

| Known Drug Space (KDS) | Molecular descriptor space defined by marketed drugs. | Predicts boundaries for drug development and assesses design candidates. | [16] |

Computational Frameworks for Multi-Objective Navigation

Navigating chemical space requires computational models that can generate novel molecular structures and optimize them against multiple objectives simultaneously. Several advanced frameworks have been developed to address this challenge.

Table 2: Multi-Objective Optimization Frameworks for Molecular Design

| Framework/Method | Core Approach | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constrained MOO (CMOMO) | Deep multi-objective optimization with dynamic constraint handling. | Two-stage optimization: first optimizes properties, then finds feasible molecules satisfying constraints. | Optimizes multiple properties while adhering to strict drug-like criteria (e.g., ring size, substructure). [5] |

| MolSearch | Search-based using Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). | Two-stage search: HIT-MCTS improves biological properties; LEAD-MCTS optimizes non-biological properties. | Hit-to-lead optimization; computationally efficient multi-objective generation. [17] |

| Pareto Optimization | Identifies a set of non-dominated solutions (Pareto front). | Reveals trade-offs between competing objectives without requiring weight assignment. | Robust alternative to scalarization methods for conflicting property optimization. [18] |

| Functional Group-Based Reasoning (FGBench) | Leverages Large Language Models (LLMs) with functional-group level data. | Provides interpretable, structure-aware reasoning linking molecular sub-structures to properties. | Predicts property changes from functional group modifications. [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking and Evaluation

Robust benchmarking is essential for comparing the performance of different generative and optimization models. The following protocols outline standardized evaluation procedures.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking with the MOSES Platform

The Molecular Sets (MOSES) platform provides a standardized benchmarking pipeline for molecular generation models [20].

- Data Preparation: Utilize the provided training and testing datasets, which are pre-processed and curated from public sources.

- Model Training: Train the generative model on the MOSES training set. Models can be based on various molecular representations (e.g., SMILES strings, molecular graphs).

- Generation: Use the trained model to generate a large set of novel molecular structures (e.g., 30,000 valid molecules).

- Evaluation Metrics Calculation:

- Validity: Fraction of generated strings that correspond to valid molecules.

- Uniqueness: Fraction of unique molecules among valid generated structures.

- Novelty: Fraction of generated molecules not present in the training set.

- Diversity: Measures the structural variety of generated molecules using internal Tanimoto diversity.

- Frèchet ChemNet Distance (FCD): Measures the distance between distributions of generated and test set molecules in the activations of the ChemNet network.

- Comparison: Compare the calculated metrics against the reference points provided by baseline models in the MOSES benchmark.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Local Chemical Space Exploration with a Transformer Model

This protocol assesses a model's ability to exhaustively explore the "near-neighborhood" of a source molecule [21].

- Model Training: Train a source-target molecular transformer model on a large dataset of molecular pairs (e.g., derived from PubChem). Incorporate a similarity-based regularization term into the loss function to correlate generation probability with molecular similarity.

- Beam Search Sampling: For a given source molecule, use beam search to generate all target molecules up to a user-defined Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL) threshold.

- Analysis of Near-Neighborhood:

- Calculate the Tanimoto similarity (e.g., based on ECFP4 fingerprints) between the source molecule and all generated targets.

- Plot the similarity against the NLL (precedence) of generation. A strong negative correlation indicates the model efficiently generates similar, chemically plausible molecules.

- Evaluate metrics like Top Identical (ability to reproduce the source molecule) and Rank Score (quality of the similarity-precedence ranking).

MOSES Benchmarking Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for conducting research in molecular generation and optimization.

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Molecular Optimization

| Resource Name | Type | Function & Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOSES (Molecular Sets) | Benchmarking Platform | Standardized dataset, metrics, and baselines for training and comparing molecular generative models. | https://github.com/molecularsets/moses |

| MoleculeNet | Benchmark Suite | Curated collection of multiple public datasets for molecular machine learning tasks (e.g., QM9, ESOL). | Integrated into DeepChem [22] |

| Chemical Universe Database (GDB) | Virtual Molecular Library | Enumerates billions of theoretically possible small molecules for virtual screening and idea generation. | www.gdb.unibe.ch |

| DeepChem | Open-Source Library | Provides high-quality implementations of molecular featurizations, learning algorithms, and model training. | https://deepchem.io |

| FGBench Dataset | Specialized Dataset | QA pairs for molecular property reasoning at the functional group-level, enabling interpretable SAR. | Reference [19] |

| Molecular Quantum Numbers (MQN) | Molecular Descriptors | A set of 42 integer-based descriptors for chemical space classification and mapping. | www.gdb.unibe.ch |

Visualization of a Multi-Objective Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a constrained multi-objective optimization process, as implemented in frameworks like CMOMO, which balances property optimization with constraint satisfaction [5].

Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization

A Landscape of AI Techniques: From Evolutionary Algorithms to Generative Models

The discovery and optimization of novel molecules for pharmaceutical and materials science applications present a complex multi-objective challenge. Researchers often need to balance conflicting objectives, such as maximizing potency while minimizing toxicity or optimizing pharmacokinetic properties. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), particularly multi-objective variants, have emerged as powerful tools for navigating this complex chemical space. Within this field, the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) has established itself as a benchmark algorithm for finding optimal trade-off solutions, while newer approaches like MoGA-TA incorporate specialized similarity measures to enhance performance. The Tanimoto similarity index plays a critical role in maintaining molecular diversity throughout the optimization process, preventing premature convergence and ensuring broad exploration of chemical space. This application note details the operational principles, experimental protocols, and practical implementation of these key technologies within molecular generation research, providing researchers with the tools needed to advance multi-objective optimization in their discovery pipelines.

Algorithmic Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Key Algorithm Specifications

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms in Molecular Optimization

| Feature | NSGA-II | MoGA-TA |

|---|---|---|

| Core Innovation | Fast non-dominated sorting with crowding distance [23] [24] | Tanimoto-based crowding distance & dynamic acceptance probability [25] |

| Diversity Mechanism | Crowding distance (Manhattan distance in objective space) [26] [24] | Tanimoto similarity-based crowding distance [25] |

| Selection Pressure | Binary tournament selection comparing rank and crowding distance [23] | Balances exploration and exploitation via dynamic acceptance probability [25] |

| Molecular Representation | Molecular graphs or string representations (SMILES, SELFIES) [24] | Implicitly operates within a defined chemical space [25] |

| Primary Application | General multi-objective optimization; finding well-distributed Pareto fronts [26] [23] | Drug molecule optimization with enhanced structural diversity [25] |

| Reported Advantage | Efficient handling of large populations; well-distributed Pareto fronts [23] | Higher success rate and efficiency in molecular optimization; avoids local optima [25] |

The Role of Tanimoto Similarity in Maintaining Diversity

The Tanimoto index is a cornerstone metric for quantifying molecular similarity in cheminformatics. In the context of multi-objective EAs, it serves as a crucial tool for preserving population diversity. The index is calculated using molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP fingerprints) and is defined for two molecules, A and B, as:

Tanimoto(A, B) = c / (a + b - c)

where a and b are the number of bits set in the fingerprints of molecules A and B, respectively, and c is the number of common bits set in both [27]. This metric is particularly appropriate for molecular similarity because it accounts for the relative sizes of the molecules being compared, helping to mitigate a bias toward selecting smaller compounds that can occur with other metrics [27]. Its effectiveness has been validated in large-scale studies, which identified it as one of the best-performing metrics for molecular similarity calculations, alongside the Dice index and Cosine coefficient [27]. In MoGA-TA, this measure is adapted to calculate a Tanimoto crowding distance, which more accurately captures structural differences between molecules in a population, thereby guiding the search toward a more diverse set of solutions in chemical space [25].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing NSGA-II for Molecular Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps for applying the NSGA-II algorithm to a multi-objective molecular optimization problem, such as simultaneously optimizing a molecule's binding affinity and synthetic accessibility.

I. Initialization and Representation

- Define the Search Space: Select a starting population of molecules from a source like the ZINC or ChEMBL database [24].

- Choose Molecular Representation: Decide on a representation scheme. Molecular graphs are often used in Graph-Based Genetic Algorithms (GB-GA) and allow for intuitive crossover and mutation operations [24].

- Set Population Parameters: Initialize a population of N molecules (e.g., N=100-500). Larger populations aid in diversity but increase computational cost.

II. Algorithmic Execution Loop Table 2: NSGA-II Workflow Steps and Operations

| Step | Operation | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Evaluation | Calculate objective functions | Evaluate each molecule in the population against all defined objectives (e.g., using QSAR models or property predictors). |

| 2. Non-Dominated Sorting | Classify solutions into Pareto fronts | Assign each solution a non-domination rank. Front 1 contains all non-dominated solutions; Front 2 contains those dominated only by Front 1, etc. [23] [24]. |

| 3. Crowding Distance | Calculate diversity within fronts | For each front, sort solutions for each objective and compute the crowding distance as the normalized sum of distances between a solution's neighbors [23]. |

| 4. Selection | Choose parent molecules | Use binary tournament selection: pick two solutions at random; the one with the better (lower) non-domination rank wins. If ranks are equal, the solution with the larger crowding distance wins [23]. |

| 5. Crossover & Mutation | Generate new offspring | Crossover: Combine molecular graphs or SELFIES strings from two parents to create new offspring molecules [24].Mutation: Apply stochastic modifications to an offspring's structure (e.g., altering atoms or bonds in a graph) to introduce novelty [24]. |

| 6. Survivor Selection | Create the next generation | Combine the parent and offspring populations. Fill the new population by selecting individuals from the best Pareto fronts. Use crowding distance as a tie-breaker for the last front that can be partially accommodated [26] [23]. |

III. Termination and Analysis

- Loop: Repeat steps 1-6 for a predefined number of generations or until convergence is observed.

- Output: The final population provides the Pareto front, representing the best trade-offs between the objectives. The "best" solution can be selected as the one closest to the utopia point (the point with the optimal value for all objectives) [28].

Figure 1: NSGA-II Molecular Optimization Workflow

Protocol 2: Implementing MoGA-TA for Drug Molecule Optimization

This protocol details the application of MoGA-TA, a specialized algorithm designed to address the challenges of high data dependency and low molecular diversity in traditional optimization methods [25].

I. Pre-Optimization Setup

- Define Multi-Objective Problem: Establish the key objectives for the drug molecule (e.g., binding affinity, solubility, metabolic stability).

- Configure MoGA-TA Parameters: Set parameters for the population size, stopping condition (e.g., number of generations, performance plateau), and the dynamic acceptance probability function.

II. Core Optimization Loop

- Decoupled Crossover and Mutation: Execute crossover and mutation operations within the defined chemical space. This decoupled strategy allows for more controlled exploration [25].

- Tanimoto Crowding Distance Calculation: For the diversity preservation step, replace the standard crowding distance with the Tanimoto-based variant. This involves: a. Generating molecular fingerprints for all individuals in a front. b. Calculating the pairwise Tanimoto similarity between all solutions. c. The crowding distance for a solution is based on the sum of Tanimoto distances to its k-nearest neighbors, favoring solutions in less densely populated structural regions [25].

- Dynamic Population Update: Employ the dynamic acceptance probability strategy to decide whether new candidate molecules are accepted into the population. This strategy probabilistically balances the exploration of new regions of chemical space with the exploitation of known promising areas [25].

III. Validation and Output

- Loop until Stopping Condition: Continue the process until the predefined stopping condition is met.

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the final population using metrics such as success rate, dominating hypervolume, geometric mean of objectives, and internal similarity to quantify the diversity and quality of the Pareto front [25].

- Output: The algorithm outputs a set of optimized candidate molecules with high performance across all objectives and significant structural diversity.

Figure 2: MoGA-TA Drug Optimization Workflow

Table 3: Key Software and Data Resources for Molecular EA Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Relevance to EAs |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyMoo [26] | Software Library | Provides a comprehensive implementation of NSGA-II and other multi-objective algorithms. | Allows researchers to rapidly prototype and deploy NSGA-II for custom optimization problems. |

| GB-GA/NSGA-II/III [24] | Open-Source Algorithm | A state-of-the-art, open-source implementation of graph-based NSGA-II and NSGA-III for molecular design. | Specifically designed for the inverse design of small molecules, using a graph representation. |

| MACCS/ECFP Fingerprints [27] [29] | Molecular Descriptor | Structural keys or circular fingerprints that encode molecular structure as a bit string. | Serves as the fundamental representation for calculating Tanimoto similarity between molecules. |

| ZINC/ChEMBL [24] | Compound Database | Publicly available databases of commercially available and bioactive molecules. | Typically used as a source for initial populations in graph-based genetic algorithms. |

| SELFIES [24] | String Representation | A robust molecular string representation where every string corresponds to a valid molecule. | Used in algorithms like STONED to prevent evolutionary stagnation through high mutational diversity. |

| Dominated Hypervolume [25] [24] | Performance Metric | Measures the volume of objective space dominated by a Pareto front, relative to a reference point. | A key metric for benchmarking and comparing the performance of different multi-objective EAs. |

The design of novel drug candidates requires the simultaneous optimization of multiple, often competing, molecular properties, such as binding affinity, solubility, and low toxicity. This multi-objective optimization presents a fundamental challenge in molecular generation research. Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful tool to navigate this complex landscape. This document details the application of two advanced RL paradigms: Policy Optimization for continuous latent space navigation and Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) for discrete structural optimization, providing structured protocols and data for their implementation in a research setting.

Quantitative Comparison of RL Paradigms in Molecular Optimization

The table below summarizes the performance outcomes of various RL paradigms as reported in recent literature, highlighting their effectiveness in different molecular optimization scenarios.

Table 1: Performance Summary of RL Paradigms in Molecular Generation

| RL Paradigm / Method | Key Properties Optimized | Reported Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Optimization (MOLRL) [30] | pLogP, Synthetic Accessibility | Achieved comparable or superior performance to state-of-the-art in constrained benchmark tasks. | Single-property optimization under structural constraints. |

| Pareto MCTS (ParetoDrug) [12] | Docking Score, QED, SA, LogP | Generated molecules with satisfactory binding affinity and drug-like properties; demonstrated high uniqueness (>90% in benchmarks). | Multi-objective, target-aware drug discovery. |

| Uncertainty-Aware RL-Diffusion [31] | QED, SA, Binding Affinity | Outperformed baselines on QM9, ZINC15, and PubChem datasets; generated candidates with promising ADMET profiles and binding stability. | De novo 3D molecular design with multi-objective constraints. |

| Multi-Turn RL (POLO) [32] | Multi-property score, Structural Similarity | 84% average success rate on single-property tasks (2.3x better than baselines); 50% success on multi-property tasks with only 500 oracle calls. | Sample-efficient lead optimization. |

| RL with Genetic Algorithm (RLMolLM) [33] | QED, SA, ADMET (e.g., hERG) | Achieved up to 31% improvement in QED scores; 4.5-fold reduction in predicted hERG toxicity. | Inverse molecular design with multi-property optimization and scaffold constraints. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Optimization via Latent Space Policy Optimization

This protocol is adapted from the MOLRL framework, which uses Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to optimize molecules in the continuous latent space of a pre-trained generative model [30].

1. Pre-trained Model Preparation: - Objective: Employ a generative model with a well-structured, continuous latent space. - Procedure: a. Select a model architecture (e.g., Variational Autoencoder (VAE) with cyclical annealing or MolMIM) [30]. b. Pre-train the model on a large molecular database (e.g., ZINC). c. Validate the model's latent space by ensuring a high reconstruction rate (>90% Tanimoto similarity) and a high validity rate (>90% for decoded random latent vectors) [30].

2. Reinforcement Learning Agent Setup:

- Objective: Configure the PPO algorithm to explore the latent space.

- Procedure:

a. State Space (sₜ): Define the state as the current latent vector representation of the molecule.

b. Action Space (aₜ): Define the action as a step (perturbation) within the continuous latent space.

c. Reward Function (rₜ): Design a scalarized reward function. For multiple objectives, use: R = w₁*Property₁ + w₂*Property₂ + ..., where wᵢ are user-defined weights [34]. The reward can be set to 0 if the generated molecule violates constraints [35].

d. Policy Network (π): Initialize a stochastic policy network that outputs a mean and variance for the action distribution.

3. Optimization Loop:

- Objective: Iteratively refine the latent vector to maximize the reward.

- Procedure:

a. Encode: Start with a lead molecule and encode it into the latent space to get an initial latent vector z₀.

b. Step: The policy network proposes an action (a perturbation), leading to a new latent vector zₜ.

c. Decode & Evaluate: Decode zₜ into a molecule and use property prediction oracles (e.g., for QED, SA) to compute the reward rₜ.

d. Update: After collecting a batch of trajectories, update the policy network parameters using the PPO objective, which maximizes expected reward while preventing overly large policy updates.

4. Termination and Validation: - Objective: Obtain and validate optimized molecules. - Procedure: Terminate after a fixed number of episodes or when reward convergence is observed. Decode the final latent vector and validate the resulting molecule's properties and structural validity using tools like RDKit.

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Optimization via Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)

This protocol is based on the ParetoDrug algorithm, which uses MCTS to generate molecules that are Pareto-optimal with respect to multiple target properties [12].

1. Initialization: - Objective: Set up the search tree and Pareto pool. - Procedure: a. Initialize Root: Create a root node representing an initial molecular fragment or a empty state. b. Initialize Pareto Pool: Create a data structure to maintain a set of non-dominated molecules (the Pareto front) found during the search.

2. Tree Traversal and Node Selection:

- Objective: Navigate from the root to a leaf node using a selection policy.

- Procedure: At each node, select the child node that maximizes the ParetoPUCT score [12]:

Score = Q + U

where:

- Q is the average scaled reward from previous rollouts.

- U is an exploration bonus, U ∝ √(ln(N_parent) / N_child), which encourages less-visited paths.

3. Node Expansion and Rollout: - Objective: Expand the tree and evaluate a new candidate molecule. - Procedure: a. Expansion: Upon reaching a leaf node, if it is non-terminal, expand it by adding child nodes for all possible next atoms or fragments. b. Rollout/Simulation: Complete the molecule from the leaf node. ParetoDrug uses a pre-trained, atom-by-atom autoregressive model to guide this completion, ensuring the generation of chemically plausible molecules [12].

4. Backpropagation and Pareto Pool Update:

- Objective: Update the tree nodes and the global Pareto pool.

- Procedure:

a. Evaluate Molecule: Calculate all target properties (e.g., Docking Score, QED, SA) for the fully generated molecule.

b. Scalarized Reward: Compute a reward, for instance, using the geometric mean: Reward = (v₁^w₁ * v₂^w₂ * ...)^(1/Σwᵢ), where vᵢ are property values and wᵢ are weights [12]. Alternatively, a constraint-based reward can be used (e.g., reward=0 if any property is outside its desired threshold) [35].

c. Backpropagate: Update the Q-values and visit counts of all nodes along the traversed path with the scalarized reward.

d. Update Pareto Pool: Compare the new molecule with the existing pool. If it is not dominated by any molecule in the pool, add it, and remove any molecules it dominates.

5. Termination and Output: - Objective: Finalize the search and return results. - Procedure: Terminate after a predefined number of iterations or computational budget. The final output is the set of molecules in the Pareto pool, representing the best trade-offs among the target properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The table below catalogs key computational tools and resources essential for implementing the described RL paradigms in molecular generation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Description | Relevance to Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Generative Model (VAE, MolMIM) | Provides a continuous, structured latent space for molecular representation, enabling smooth optimization. | Critical for Protocol 1 (Latent Space Optimization). Serves as the environment and decoder [30]. |

| Property Prediction Oracles (e.g., QED, SA, Docking) | Computational models that predict key molecular properties from structure. Act as the reward function. | Essential for both protocols. Used to evaluate generated molecules and compute rewards [12] [31]. |

| Autoregressive Generative Model | A model that constructs molecules atom-by-atom, providing a prior for chemically valid structures. | Critical for Protocol 2 (Pareto MCTS). Guides the rollout phase to complete molecules [12]. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) Filter | A reliability measure (e.g., based on Tanimoto similarity) to ensure predictions are made within the model's reliable scope. | Used to prevent reward hacking by setting reward to 0 for molecules outside the AD [35]. |

| Pareto Pool Data Structure | A collection (e.g., a list) that maintains a set of non-dominated solutions during an optimization run. | Core component of Protocol 2. Stores the evolving Pareto front [12]. |

| smina | A software tool for molecular docking, used to predict binding affinity and pose. | Commonly used as an oracle for the "Docking Score" objective in target-aware generation [12]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for handling molecular data, validity checks, and descriptor calculation. | Used across both protocols for processing molecules, checking validity, and calculating properties [30] [33]. |

Latent Space Optimization (LSO) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for navigating the complex landscape of molecular design. By leveraging the continuous latent representations learned by generative models such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), LSO transforms the discrete challenge of molecular optimization into a tractable continuous optimization problem [30]. This approach is particularly valuable within multi-objective optimization frameworks, where the goal is to identify molecules that optimally balance multiple, often competing, properties such as potency, metabolic stability, and synthetic accessibility [11] [14].

The significance of LSO is underscored by the fundamental challenge in drug discovery: the chemical space is astronomically vast, while the region containing viable drug candidates is exceedingly small and sparsely distributed. Traditional methods struggle to efficiently explore this space. However, by operating in a smooth, continuous latent space, LSO enables efficient navigation and identification of promising candidates that satisfy multiple objectives simultaneously, thereby accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel therapeutic compounds [30] [36].

Fundamental Principles of Latent Space Optimization

LSO relies on several key characteristics of a well-structured latent space to enable effective optimization. The performance of any LSO method is contingent upon the quality of this underlying space, which is defined by the following properties:

- Reconstruction Accuracy: This measures a model's ability to accurately encode a molecule into a latent vector and then decode it back to its original structure without significant loss of information. High reconstruction accuracy ensures that the latent representation faithfully captures the essential structural features of the molecule, which is a prerequisite for meaningful optimization [30].

- Latent Space Validity: A critical requirement is that a high proportion of randomly sampled points from the latent space decode to valid, chemically plausible molecular structures. Optimization algorithms navigating a space with low validity would waste significant computational resources evaluating invalid candidates [30].

- Latent Space Continuity (Smoothness): This property ensures that small perturbations in the latent vector result in small, continuous changes in the decoded molecular structure. A continuous space allows gradient-based or policy-based optimization algorithms to make coherent, incremental steps toward improved solutions, rather than jumping erratically between structurally disparate molecules [30].

Quantitative assessments of these properties for different generative models are essential for selecting the appropriate foundation for LSO. The table below summarizes typical performance metrics for two common model types: a Variational Autoencoder with Cyclical Annealing (VAE-CYC) and a Mutual Information Machine (MolMIM) model [30].

Table 1: Quantitative Evaluation of Generative Model Latent Spaces for LSO

| Model | Reconstruction Rate (Avg. Tanimoto Similarity) | Validity Rate (%) | Continuity (Avg. Tanimoto at σ=0.1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAE-CYC | High (Precise value dataset-dependent) | High | Smooth decline (~0.8) |

| MolMIM | High (Precise value dataset-dependent) | High | Minimal change (~0.95) |

The continuity is often evaluated by adding Gaussian noise with variance ( \sigma ) to latent vectors and measuring the structural similarity (Tanimoto) between the original and perturbed molecules. For instance, with ( \sigma = 0.1 ), the VAE-CYC model shows a smooth decline in similarity, while the MolMIM model exhibits high robustness, indicating a very continuous space [30].

Multi-Objective LSO Frameworks and Comparative Performance

Multi-objective optimization requires frameworks that can effectively identify trade-offs between conflicting goals. Several advanced LSO methods have been developed for this purpose, each with distinct mechanisms and strengths.

Table 2: Comparison of Multi-Objective Latent Space Optimization Frameworks

| Framework | Core Methodology | Key Advantages | Reported Application/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOLRL (Latent Reinforcement Learning) | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) in latent space [30] [37] | Sample-efficient; handles continuous, high-dimensional spaces; agnostic to model architecture [30] [37]. | Comparable or superior to state-of-the-art on single-property and scaffold-constrained optimization [30] [37]. |

| Multi-Objective LSO (Iterative Weighted Retraining) | Iterative retraining weighted by Pareto efficiency [14] [38] [39] | Effectively pushes the Pareto front; improves model sampling for multiple properties [14]. | Generated DRD2 inhibitors with superior in silico performance to known drugs [14]. |

| CMOMO (Constrained Molecular Multi-objective Optimization) | Two-stage deep evolutionary algorithm with dynamic constraint handling [5] | Explicitly balances property optimization with strict drug-like constraint satisfaction [5]. | Two-fold improvement in success rate for GSK3β inhibitor optimization; high feasibility rates [5]. |

| VAE-Active Learning (AL) Workflow | Nested AL cycles using chemoinformatic and physics-based oracles [36] | Integrates reliable physics-based predictions (docking); enhances synthetic accessibility and novelty [36]. | For CDK2: 8 out of 9 synthesized molecules showed in vitro activity, including one nanomolar potency [36]. |

| Decoupled Bayesian Optimization | Decouples generative model (VAE) from GP surrogate [40] | Allows each component to focus on its strengths; improved candidate identification under budget constraints [40]. | Shows improved performance in molecular optimization with constrained evaluation budgets [40]. |

These frameworks demonstrate that LSO is a versatile concept that can be successfully implemented using a variety of optimization paradigms, from reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms to Bayesian optimization and active learning.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Objective Optimization via Latent Reinforcement Learning (MOLRL)

This protocol outlines the procedure for using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to optimize molecules in the latent space of a pre-trained autoencoder [30] [37].

Required Research Reagents & Computational Tools:

- Pre-trained Generative Model: A VAE or other autoencoder model trained on a large chemical database (e.g., ZINC), with demonstrated high reconstruction accuracy and validity [30].

- Property Prediction Oracles: Computational models or functions to calculate target properties (e.g., LogP, QED, synthetic accessibility score, biological activity predictor) [30] [37].

- Reinforcement Learning Library: A software framework implementing the PPO algorithm (e.g., OpenAI Spinning Up, Stable-Baselines3) [30].

- Chemical Informatics Toolkit: RDKit or similar for handling molecular structures and calculating basic descriptors [30].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initialization:

- Pre-train a generative autoencoder (e.g., VAE with SMILES representation) on a large molecular dataset to obtain a continuous latent space.

- Define a multi-objective reward function ( R(m) ) that combines the target properties for a generated molecule ( m ). This can be a weighted sum or a more complex function.

- Initialize the PPO policy network (e.g., a multivariate Gaussian policy) with parameters ( \theta ).

Latent Space Exploration:

- For each episode, the agent (policy) selects an action, which is a step ( \Delta z ) in the latent space from the current state (latent vector ( z_t )).

- The new state is updated: ( z{t+1} = zt + \Delta z ).

Molecular Decoding and Reward Calculation:

- Decode the new latent vector ( z{t+1} ) into a molecule ( m{t+1} ) using the generative model's decoder.

- If the decoded SMILES is invalid, assign a large negative reward and terminate the episode.

- If the molecule is valid, compute the reward ( R(m_{t+1}) ) using the property prediction oracles.

Policy Update:

- After collecting a batch of trajectories (sequences of states, actions, and rewards), update the policy parameters ( \theta ) using the PPO clipping objective to maximize the expected cumulative reward.

- The update rule aims to increase the probability of actions that lead to high-reward regions of the latent space.

Iteration and Termination:

- Repeat steps 2-4 for a predetermined number of episodes or until the performance plateaus.

- Output the set of molecules generated by the highest-reward latent points visited.

Protocol 2: Iterative Weighted Retraining for Multi-Objective LSO

This protocol uses iterative retraining of a generative model based on Pareto efficiency to bias the latent space towards regions containing molecules with optimal property trade-offs [14] [38].

Required Research Reagents & Computational Tools:

- Initial Pre-trained Model: A generative model (e.g., VAE) pre-trained on a broad chemical dataset.

- Property Predictors: Functions or models for all target objectives.

- Pareto Ranking Algorithm: Code to identify the Pareto front and rank molecules by their Pareto efficiency.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initial Sampling:

- Sample an initial set of molecules ( D0 ) from the pre-trained generative model.

- Evaluate all molecules in ( D0 ) against the multiple target objectives.

Pareto Analysis and Weighting:

- Identify the non-dominated set (Pareto front) from the pooled data of all molecules sampled so far.

- Assign a weight to each molecule in the training pool. This weight is typically based on its Pareto efficiency, with molecules on the front receiving the highest weight. The weighting scheme ensures that the model prioritizes learning from the most optimal candidates.

Model Retraining:

- Fine-tune or retrain the generative model on the weighted dataset. This step shifts the model's latent space distribution towards the high-performing regions identified by the Pareto analysis.

Informed Sampling:

- Sample a new set of molecules from the newly retrained model. These molecules are biased towards the Pareto-optimal regions.

- Evaluate the new molecules using the property predictors.

Iteration:

- Combine the new molecules with the existing pool.

- Repeat steps 2-5 for a fixed number of iterations. With each cycle, the Pareto front is expected to advance, yielding molecules with progressively better property balances.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for LSO

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LSO

| Item Name | Type/Class | Primary Function in LSO | Exemplars & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Autoencoder | Computational Model | Creates a continuous latent representation of molecular structures; serves as the map for optimization. | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [30] [36], Mutual Information Machine (MolMIM) [30]. Quality is critical (see Table 1). |

| Property Prediction Oracle | Computational Model or Function | Provides the objective function(s) for optimization by scoring generated molecules on desired properties. | QSAR models, docking scores (e.g., for KRAS, CDK2) [36], calculated properties (e.g., QED, LogP, SAscore) [30] [5]. |

| Optimization Algorithm | Algorithm | The "engine" that navigates the latent space by proposing new latent vectors likely to improve objectives. | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [30] [37], Evolutionary Algorithms [5], Bayesian Optimization (e.g., Gaussian Processes) [40]. |