Multimodal Learning for Materials Data: A Framework for Accelerated Drug Discovery and Material Design

This article explores the transformative potential of multimodal learning (MML) in materials science and drug development.

Multimodal Learning for Materials Data: A Framework for Accelerated Drug Discovery and Material Design

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of multimodal learning (MML) in materials science and drug development. It addresses the core challenge of integrating diverse, multiscale data—from atomic structures and micrographs to processing parameters and clinical outcomes—which is often incomplete or heterogeneous. The article provides a foundational understanding of MML principles, details cutting-edge methodological frameworks and their applications in predicting material properties and drug interactions, offers solutions for common troubleshooting and optimization scenarios like handling missing data, and presents a comparative analysis of model validation and performance. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide serves as a comprehensive resource for leveraging MML to enhance predictive accuracy, accelerate discovery, and pave the way for personalized therapies.

What is Multimodal Learning? Unlocking the Power of Combined Data for Materials and Medicine

Multimodal learning represents a significant evolution in artificial intelligence (AI), enabling the integration and understanding of various input types such as text, images, audio, and video. Unlike unimodal models restricted to a single input type, multimodal learning systems process multiple modalities simultaneously, providing a more comprehensive understanding that reflects real-world interactions [1]. This approach stands at the cutting edge of AI research, revolutionizing fields from medical science to materials discovery by capturing complementary information that would be inaccessible through any single data source alone [2] [3].

The core importance of multimodal learning lies in its capacity for cross-modal learning, where models create meaningful connections between different data types, enabling tasks that require comprehension and generation of content across diverse modalities [1]. This capability is particularly valuable in scientific domains like materials science, where datasets often encompass diverse data types with critical feature nuances that present both distinctive challenges and exciting opportunities for AI applications [2]. By moving beyond single-data source limitations, researchers can develop more robust, accurate, and context-aware systems that mirror the multifaceted nature of real-world scientific inquiry.

Core Principles and Architectures of Multimodal Learning

Theoretical Foundations

Multimodal learning is built upon several key theoretical foundations that enable its advanced capabilities. Representation learning allows multimodal systems to create joint embeddings that capture semantic relationships across modalities, effectively understanding how concepts in one domain (e.g., language) relate to elements in another (e.g., visual features) [1]. Transfer learning enables models to apply knowledge gained from one task to new, related tasks, allowing them to leverage general knowledge acquired from large datasets to perform well on specific scientific problems with minimal additional training [1]. Perhaps most critically, attention mechanisms originally developed for natural language processing have been extended to enable models to focus on relevant aspects across different modalities, allowing more effective processing of multimodal data streams [1].

Architectural Frameworks

Several key architectural innovations have enabled the successful implementation of multimodal learning systems:

Encoder-Decoder Frameworks: These architectures allow for mapping between different domains, such as text and crystal structures in materials science. The encoder processes the input (e.g., textual description), while the decoder generates the output (e.g., molecular structure) [1].

Cross-Modal Transformers: These utilize separate transformers for each modality, with cross-modal attention layers to fuse information. This allows the model to process different data types separately before combining the information for a more comprehensive understanding [1].

Dynamic Fusion Mechanisms: Advanced approaches incorporate learnable gating mechanisms that assign importance weights to different modalities dynamically, ensuring that complementary modalities contribute meaningfully even when dealing with redundant or missing data [4].

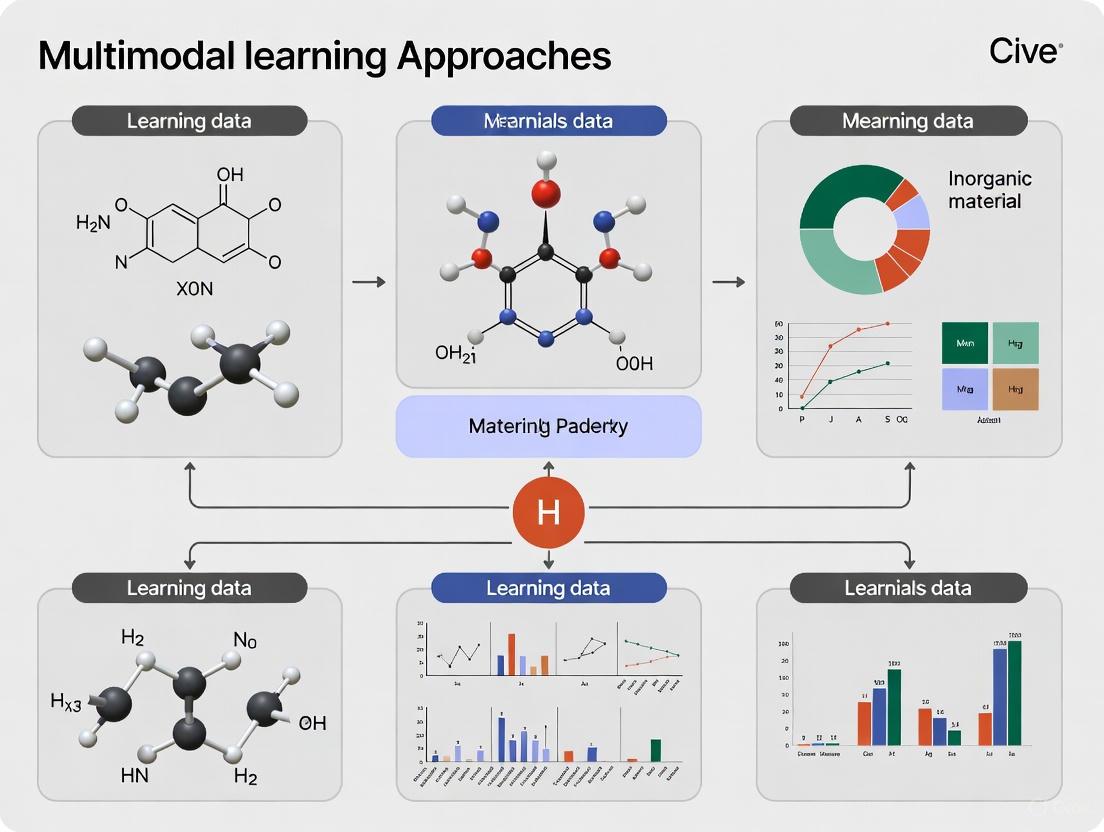

The following diagram illustrates a generalized architecture for multimodal learning systems, showing how different data modalities are processed and integrated:

Figure 1: Generalized architecture of a multimodal learning system showing processing and fusion of diverse data types.

Multimodal Learning in Materials Science: Applications and Workflows

Domain-Specific Applications

Materials science presents particularly compelling use cases for multimodal learning due to the inherent complexity and heterogeneity of materials data. Research in this domain demonstrates several impactful applications:

Accelerated Materials Discovery: Multimodal foundation models can simultaneously analyze molecular structures, research papers, and experimental data to identify potential new compounds for specific applications, significantly accelerating the discovery timeline [1] [4]. For instance, integrating textual knowledge from scientific literature with structural information has enabled more efficient prediction of crystal structures with desired properties [2].

Enhanced Property Prediction: By combining different representations of materials data, multimodal approaches achieve superior performance on property prediction tasks. Techniques that bridge atomic and bond modalities have demonstrated enhanced capabilities for predicting critical properties like bandgap in crystalline materials [2].

Autonomous Experimental Systems: Multimodal learning enables the development of autonomous microscopy and materials characterization systems that can dynamically adjust experimental parameters based on real-time analysis of multiple data streams, leading to more efficient and insightful materials investigation [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Multimodal Approaches in Materials Research

Table 1: Performance comparison of multimodal learning approaches on materials science tasks

| Model/Method | Data Modalities | Primary Task | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Multi-Modal Fusion [4] | Molecular structure, textual descriptors | Property prediction | Prediction accuracy | Improved efficiency and robustness to missing data |

| Literature-driven Contrastive Learning [2] | Text, crystal structures | Material property prediction | Cross-modal retrieval accuracy | Enhanced structure-property relationships |

| Crystal-X Network [2] | Atomic, bond modalities | Bandgap prediction | Prediction error | Superior to unimodal baselines |

| CDVAE/CGCNN [2] | Crystal graph, energy | Materials generation | Validity of generated structures | Accelerated discovery cycle |

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Multimodal Fusion for Materials

The following detailed methodology outlines the experimental approach for implementing dynamic multimodal fusion in materials science research, based on established protocols in the field [4]:

Objective: To develop a multimodal foundation model for materials property prediction that dynamically adjusts modality importance and maintains robustness with incomplete data.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Primary Dataset: MoleculeNet benchmark collection [4]

- Data Modalities:

- Molecular structures (graph representations)

- Textual descriptors (chemical notations, semantic features)

- Electronic properties (calculated quantum chemical properties)

- Synthetic accessibility indices

Experimental Procedure:

Data Preprocessing:

- Represent molecular structures as graphs with nodes (atoms) and edges (bonds)

- Convert textual descriptors to embedding vectors using domain-specific language models

- Normalize continuous numerical properties to zero mean and unit variance

- Implement data augmentation techniques to increase dataset diversity

Modality Encoding:

- Process molecular graphs using graph neural networks (GNNs)

- Encode textual descriptors through transformer-based architectures

- Project numerical properties through fully connected embedding layers

Dynamic Fusion Mechanism:

- Implement gating mechanism with learnable parameters

- Calculate attention weights for each modality based on context

- Apply weighted combination of modality-specific representations

- Generate joint multimodal representation

Training Protocol:

- Utilize multi-task learning objective combining property prediction and reconstruction losses

- Implement gradient clipping and learning rate scheduling

- Employ early stopping based on validation performance

- Regularize through dropout and weight decay

Evaluation Metrics:

- Primary: Prediction accuracy on downstream property prediction tasks

- Secondary: Robustness to missing modalities during inference

- Tertiary: Training efficiency and convergence stability

Validation Approach:

- Compare against unimodal baselines and static fusion approaches

- Conduct ablation studies to isolate contribution of dynamic weighting mechanism

- Perform cross-validation across multiple material classes

- Statistical significance testing of performance differences

Implementation Framework: The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational tools for multimodal materials research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Datasets | MoleculeNet [4] | Benchmark datasets for materials property prediction | Training and evaluation of multimodal models |

| Representation Learning | Graph Neural Networks, Transformers [1] | Encode structured and unstructured data into unified representations | Creating joint embedding spaces across modalities |

| Fusion Architectures | Dynamic Fusion [4], Cross-modal Transformers [1] | Integrate information from multiple data sources | Combining structural, textual, and numerical data |

| Domain-Specific Encoders | Crystal Graph CNNs [2], SMILES-based language models | Process materials-specific data formats | Encoding crystal structures, molecular representations |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Multi-task benchmarking suites, Robustness tests | Assess model performance across diverse conditions | Validating real-world applicability |

Workflow Integration Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for multimodal learning in materials science, from data acquisition to knowledge generation:

Figure 2: End-to-end experimental workflow for multimodal learning in materials science research.

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

While multimodal learning offers transformative potential for materials research, several significant challenges must be addressed for successful implementation. Technical limitations around data synchronization and standardization present substantial hurdles, particularly when integrating diverse data sources with different temporal and spatial resolutions [5]. Data management and storage complexities emerge from the sheer volume of multimodal datasets, requiring robust infrastructure and innovative solutions for effective organization and processing [6]. Perhaps most critically, interpretability and trust concerns necessitate the development of explainable AI approaches that can provide insights into how multimodal models reach their conclusions, which is essential for scientific adoption [1].

Future research directions should focus on developing more dynamic fusion mechanisms that can automatically adjust to varying data quality and availability [4], creating standardized evaluation frameworks specific to materials science applications [2] [6], and advancing cross-modal generalization techniques that can leverage knowledge across different materials classes and experimental conditions [1]. Additionally, increasing attention to ethical AI development and bias mitigation will be crucial as these systems become more influential in guiding experimental decisions and resource allocation [1].

The integration of multimodal learning approaches into materials science represents a paradigm shift in how researchers extract knowledge from complex, heterogeneous data. By moving beyond single-data source limitations, the materials research community can accelerate discovery, enhance predictive modeling, and ultimately develop novel materials with tailored properties for specific applications across drug development, energy storage, and countless other domains.

The growing complexity of scientific research demands innovative approaches to manage and interpret vast, heterogeneous datasets. Multimodal learning (MML), an artificial intelligence (AI) methodology that integrates and processes multiple types of data (modalities), is revolutionizing fields like materials science and drug discovery [7]. These disciplines inherently generate diverse data types—spanning atomic composition, microscopic structure, macroscopic properties, and clinical outcomes—that are often correlated and complementary. Capturing and integrating these multiscale features is crucial for accurately representing complex systems and enhancing model generalization [7].

In materials science, datasets often encompass diverse data types and critical feature nuances, presenting a distinctive and exciting opportunity for multimodal learning architectures [2] [3]. Similarly, in drug discovery, AI now integrates disparate data across genomics, proteomics, and clinical records, enabling connections that were previously impractical [8]. This whitepaper examines the key data modalities central to these fields, the frameworks for their integration, and the experimental methodologies driving next-generation scientific breakthroughs, all within the context of multimodal learning approaches for materials data research.

Key Data Modalities in Materials Science

Materials science is fundamentally concerned with understanding the relationships between a material's processing, its resulting structure, and its final properties—often called the PSPP linkages. Multimodal learning provides the framework to model these complex, hierarchical relationships.

Core Modalities and Their Interrelationships

The primary modalities in materials science form a chain of causality that multimodal models aim to decode.

- Processing Parameters: These are the controlled experimental conditions during material synthesis. For electrospun nanofibers, a key model system, this includes variables such as flow rate, concentration, voltage, rotation speed, and ambient temperature, and humidity [7]. This data is typically structured and represented in tabular format.

- Microstructure: This modality captures the internal architecture of a material, often visualized through techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) [7]. It includes complex morphologies such as fiber alignment, diameter distribution, and porosity. This is a high-dimensional, image-based modality.

- Material Properties: These are the measurable performance characteristics, such as the mechanical properties of electrospun films, which include fracture strength, yield strength, elastic modulus, tangent modulus, and fracture elongation [7]. This is typically structured, quantitative data.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a structure-guided multimodal learning framework (MatMCL) designed to model these relationships, even with incomplete data.

Diagram 1: MatMCL Framework for Materials Science

Advanced and Emerging Material Modalities

Beyond the core PSPP chain, other critical modalities are enabling finer control and discovery.

- Crystal Structure: For crystalline materials, the atomic arrangement is a fundamental modality. AI models now leverage crystallographic information files (CIFs) and graph representations of crystal structures for property prediction and discovery [9] [2].

- Spectral Characteristics: Data from techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) and spectroscopy provide insights into chemical composition and bonding, serving as a fingerprint for material identification and analysis [7].

- Operando and Time-Series Data: Data captured during material operation (e.g., in a battery or fuel cell) provides a dynamic view of performance and degradation, which is critical for applications in sustainability and energy storage [9].

Table 1: Key Data Modalities in Materials Science and Their Applications

| Modality Category | Specific Data Types | Common Representation | Primary Application in MML |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Parameters | Flow rate, concentration, voltage, temperature [7] | Numerical table | Input for predicting structure/properties |

| Microstructure | SEM images, fiber alignment, porosity [7] | 2D/3D image | Linking process to properties; conditional generation |

| Material Properties | Fracture strength, elastic modulus, conductivity [7] | Numerical vector | Model training and validation output |

| Crystal Structure | Crystallographic Information Files (CIFs) [2] | Graph, 3D coordinates | Crystal property prediction and discovery |

| Spectral Data | XRD patterns, Raman spectra [7] | Sequential/vector data | Material identification and characterization |

Key Data Modalities in Drug Discovery

The drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to clinical trials, generates a vast array of data modalities. Integrating these is essential for improving the efficiency and success rate of developing new therapies.

Molecular and Cellular Modalities

The initial stages of discovery are dominated by data characterizing the interaction between a drug candidate and its biological target.

- Genomic and Proteomic Data: This includes data on DNA sequences, gene expression, and protein abundance. AI-powered knowledge graphs link this disparate data to uncover novel disease targets and biomarkers [8]. For example, researchers used AI to evaluate 54 immune-related genes as potential Alzheimer's disease targets in days instead of weeks [8].

- Molecular Structures: The 3D structure of proteins and small molecules is critical for rational drug design. Advances like DeepMind's AlphaFold 3 have dramatically improved protein structure predictions, while generative AI models create novel molecules with optimized properties from scratch (de novo design) [8].

- Target Engagement Data: Confirming that a drug binds to its intended target in a physiologically relevant context is paramount. Technologies like the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) are used to validate direct binding in intact cells and tissues, providing a crucial link between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy [10].

- ADMET Properties: Predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) through in silico simulations is now a standard modality to triage compound libraries early in the pipeline, reducing reliance on animal testing and accelerating development [8] [10].

Clinical and Commercial Modalities

As a candidate drug progresses, the relevant data expands to include patient outcomes and real-world evidence.

- Clinical Trial Data: AI is used to optimize clinical trials by improving patient selection, simulating outcomes, and integrating real-world data. This increases trial efficiency, reduces dropout rates, and improves the likelihood of demonstrating efficacy [8]. A 2024 analysis found AI-assisted drug candidates achieved Phase I success rates of nearly 90%, compared to industry averages of 40–65% [8].

- Real-World Evidence (RWE) and Health Records: Data from electronic health records and patient registries provide insights into long-term drug safety, effectiveness, and new therapeutic indications for drug repurposing [8].

- Pipeline and Deal Activity: From a business perspective, the growth of new therapeutic modalities—such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and cell therapies—is tracked through pipeline value and deal-making data. In 2025, new modalities account for $197 billion, or 60% of the total pharma projected pipeline value [11].

The following workflow illustrates how these diverse modalities are integrated using AI to streamline the drug discovery process.

Diagram 2: AI-Driven Multimodal Integration in Drug Discovery

Table 2: Key Data Modalities in Drug Discovery and Their Applications

| Modality Category | Specific Data Types | AI/ML Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular & Cellular | Genomic sequences, protein structures (AlphaFold) [8] | Target discovery & validation; de novo drug design |

| Pharmacological | In silico ADMET, binding affinity (docking) [8] [10] | Compound prioritization and lead optimization |

| Target Engagement | CETSA data in cells/tissues [10] | Mechanistic validation in physiologically relevant context |

| Clinical & Real-World | Patient records, clinical trial outcomes, biomarkers [8] | Trial optimization, patient stratification, drug repurposing |

| Commercial | Pipeline value, deal activity [11] | Tracking growth of modalities (e.g., mAbs, ADCs, CAR-T) |

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Research

To illustrate the practical application of multimodal learning, we detail a specific experimental protocol from a recent study on materials science, which can serve as a template for similar research.

Case Study: Multimodal Learning for Electrospun Nanofibers (MatMCL)

This protocol is based on the work presented in the Nature article "A versatile multimodal learning framework bridging..." which proposed the MatMCL framework [7].

Dataset Construction and Preparation

- Material Synthesis: Prepare a library of electrospun nanofiber samples by systematically varying processing parameters. Key parameters to control include polymer solution flow rate, concentration, applied voltage, collector rotation speed, and ambient temperature and humidity [7].

- Microstructural Characterization: Image each nanofiber sample using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Ensure consistent imaging conditions to obtain high-quality micrographs that capture morphological features like fiber diameter, alignment, and surface topography [7].

- Property Measurement: Subject the nanofiber films to standardized tensile testing to measure mechanical properties. Record key metrics including fracture strength, yield strength, elastic modulus, tangent modulus, and fracture elongation for both longitudinal and transverse directions [7].

- Data Curation: Assemble a multimodal dataset where each sample entry links its specific processing parameters, its corresponding SEM image(s), and its measured mechanical properties. This curated dataset forms the foundation for training the multimodal model.

Model Training and Implementation

- Encoder Selection:

- Table Encoder: Employ a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) or a more advanced FT-Transformer to encode the tabular processing parameters.

- Vision Encoder: Employ a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) or a Vision Transformer (ViT) to extract features from the raw SEM images [7].

- Structure-Guided Pre-training (SGPT):

- Use a multimodal encoder (e.g., a Transformer with cross-attention) to create a fused representation from both processing parameters and SEM images.

- Employ a contrastive learning strategy. Use the fused representation as an anchor and align it with its corresponding unimodal representations (from the table and vision encoders) as positive pairs. Representations from other samples are negative pairs. This is done in a joint latent space created by a shared projector head [7].

- Objective: The goal is to maximize the agreement between positive pairs and minimize it for negative pairs, forcing the model to learn the underlying correlations between processing conditions and microstructure.

- Downstream Task Fine-tuning:

- Property Prediction: Freeze the pre-trained encoders and add a trainable multi-task predictor on top of the joint latent space to predict the mechanical properties. This approach remains robust even when structural information (SEM images) is missing, as the fused representation retains structural knowledge [7].

- Cross-Modal Retrieval: Use the aligned latent space to retrieve microstructures that correspond to a given set of processing parameters, and vice-versa.

- Conditional Generation: Implement a generation module that can produce realistic microstructures conditioned on specific processing parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents, materials, and software used in the featured experiments and fields, providing a resource for researchers seeking to implement similar multimodal approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Multimodal Science

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Field |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning Apparatus | Laboratory Equipment | Fabricates nanofibers with controlled morphology by varying processing parameters [7] | Materials Science |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Characterization Tool | Images material microstructure at high resolution (e.g., fiber alignment, porosity) [7] | Materials Science |

| Tensile Testing Machine | Mechanical Tester | Measures mechanical properties of materials (e.g., strength, elastic modulus) [7] | Materials Science |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) | Biochemical Assay | Validates direct drug-target engagement in intact cells and native tissue environments [10] | Drug Discovery |

| AlphaFold 3 | Software Model | Predicts 3D structures of proteins and protein-ligand interactions with high accuracy [8] | Drug Discovery |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Molecular Tool | Enables precise gene editing for functional genomics and development of gene therapies [9] | Drug Discovery |

| FT-Transformer / ViT | AI Model Architecture | Encodes tabular data and image data, respectively, for multimodal fusion tasks [7] | Both Fields |

| Moleculenet Dataset | Benchmark Data | A standard dataset used for training and evaluating machine learning models on molecular properties [4] | Both Fields |

The integration of diverse data modalities through advanced AI frameworks is fundamentally changing the landscape of scientific discovery. In materials science, frameworks like MatMCL are tackling the perennial challenge of linking processing, structure, and properties, enabling robust prediction and design even in the face of incomplete data [7]. In drug discovery, the convergence of genomic, structural, pharmacological, and clinical data is creating a more predictive and efficient pipeline, as evidenced by the significantly higher success rates of AI-assisted drug candidates [8]. The continued development and application of multimodal learning will rely on the creation of high-quality, curated datasets, innovative model architectures that can dynamically handle missing modalities, and interdisciplinary collaboration between domain scientists and AI researchers. As these fields mature, the scientists and organizations that master the integration of these key data modalities will lead the way in creating the next generation of advanced materials and life-saving therapies.

The central challenge in modern materials science is the vast separation of scales: the macroscopic performance of a material is the ultimate result of mechanisms operating across atomic, microstructural, and continuum scales [12]. This process-structure-properties-performance paradigm has become the core framework for material development [12]. Multiscale modeling addresses this complexity through a 'divide and conquer' approach, creating an ordered hierarchy of scales where relevant mechanisms at each level are analyzed with appropriate theories [12]. The hierarchy is integrated through carefully designed information passing: larger-scale models regulate smaller-scale models through average kinematic constraints (like boundary conditions), while smaller-scale models inform larger ones through averaged dynamic responses (like stress) [12]. This conceptual framework, supported mathematically by homogenization theory in specialized cases, enables researchers to manage the overwhelming complexity of material systems [12].

The Data Integration Challenge: Why Multimodal Learning is Required

Material systems inherently produce heterogeneous data types—including chemical composition, microstructure imagery, spectral characteristics, and macroscopic morphology—that are often correlated or complementary [7]. Consequently, capturing and integrating these multiscale features is crucial for accurate material representation and enhanced model generalization [7]. However, several significant obstacles impede this integration:

- Data Scarcity and Cost: Due to the high cost and complexity of material synthesis and characterization, available data in materials science remains severely limited, creating substantial barriers to model training and reducing predictive reliability [7].

- Incomplete Modalities: Material datasets are frequently incomplete because experimental constraints and high acquisition costs make certain measurements, such as microstructural data from SEM or XRD, less available than basic processing parameters [7].

- Cross-Modal Alignment: Existing methods often lack efficient cross-modal alignment and typically do not provide a systematic framework for modality transformation or mapping mechanisms [7].

These limitations pose significant obstacles to the broader application of AI in materials science, particularly for complex material systems where multimodal data and incomplete characterizations are prevalent [7].

Multimodal Learning Frameworks: Architectures for Bridging Scales

Inspired by advances in multimodal learning (MML) for natural language processing and computer vision, researchers have developed specialized frameworks to overcome the challenges of multiscale material data [7]. These frameworks aim to integrate and process multiple data types (modalities) to enhance the model's understanding of complex material systems and mitigate data scarcity [7].

MatMCL: A Structure-Guided Multimodal Framework

The MatMCL framework represents a significant advancement by jointly analyzing multiscale material information and enabling robust property prediction with incomplete modalities [7]. This framework employs several key components:

- Structure-Guided Pre-training (SGPT): Uses a geometric multimodal contrastive learning strategy to align modality-specific and fused representations [7]. This approach guides the model to capture structural features, enhancing representation learning and mitigating the impact of missing modalities [7].

- Multi-stage Learning Strategy: Extends the framework's applicability to complex tasks like guiding the design of nanofiber-reinforced composites [7].

- Cross-Modal Capabilities: Incorporates a retrieval module for knowledge extraction across modalities and a conditional generation module that enables structure generation according to given conditions [7].

In practice, for a batch containing N samples, the processing conditions, microstructure, and fused inputs are processed by separate encoders (table, vision, and multimodal encoders) [7]. A shared projector then maps these encoded representations into a joint space for multimodal contrastive learning, where fused representations serve as anchors to align information from other modalities [7].

MultiMat: Multimodal Foundation Models for Materials

The MultiMat framework enables self-supervised multi-modality training of foundation models for materials, adapting and extending contrastive learning approaches to handle an arbitrary number of modalities [13] [14]. This approach:

- Aligns latent spaces of encoders for different information-rich modalities, such as crystal structure, density of states (DOS), charge density, and textual descriptions [13].

- Produces shared latent spaces and effective material representations that can be transferred to various downstream tasks [13].

- Employs specialized encoders for each modality, such as PotNet (a state-of-the-art graph neural network) for crystal structures [13].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Multimodal Learning Frameworks for Materials Science

| Framework | Core Approach | Modalities Handled | Key Innovations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatMCL [7] | Structure-guided pre-training with contrastive learning | Processing parameters, microstructure images, properties | Handles missing modalities; enables cross-modal retrieval and generation | Property prediction without structural info; microstructure generation |

| MultiMat [13] [14] | Multimodal foundation model with latent space alignment | Crystal structure, density of states, charge density, text | Extends to >2 modalities; self-supervised pre-training | State-of-the-art property prediction; material discovery via latent space |

Diagram 1: Multimodal learning architecture for material data integration.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Case Study: Electrospun Nanofibers with MatMCL

To validate the MatMCL framework, researchers constructed a multimodal benchmark dataset through laboratory preparation and characterization of electrospun nanofibers [7]. The experimental methodology proceeded as follows:

1. Dataset Construction:

- Processing Control: Morphology and arrangement of nanofibers were controlled by adjusting combinations of flow rate, concentration, voltage, rotation speed, and ambient temperature/humidity [7].

- Microstructure Characterization: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to characterize the resulting microstructures [7].

- Property Measurement: Mechanical properties of electrospun films were tested in both longitudinal and transverse directions using tensile tests, measuring fracture strength, yield strength, elastic modulus, tangent modulus, and fracture elongation [7]. A binary indicator was added to processing conditions to specify tensile direction [7].

2. Network Architecture Implementation: Two network architectures were implemented to demonstrate MatMCL's generality [7]:

- MLP-CNN Architecture: Used a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to extract features from processing conditions and a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to extract microstructural features, with modality features concatenated for multimodal representation [7].

- Transformer-Based Architecture: Employed an FT-Transformer as the table encoder and a Vision Transformer (ViT) as the vision encoder, incorporating a multimodal Transformer with cross-attention to capture interactions between processing conditions and structures [7].

3. Training Methodology: The structure-guided pre-training employed contrastive learning where [7]:

- For each sample, the fused representation served as the anchor

- Corresponding unimodal embeddings (processing conditions and structures) formed positive pairs

- Embeddings from other samples served as negatives

- All embeddings were projected into a joint latent space via a projector head

- Contrastive loss maximized agreement between positive pairs while minimizing agreement for negative pairs

Multimodal Foundation Model Training with MultiMat

The MultiMat framework demonstrated its approach using data from the Materials Project database, incorporating four distinct modalities for each material [13]:

1. Modality Processing:

- Crystal Structure: Represented as C = ({(rᵢ,Eᵢ)}ᵢ,{Rⱼ}ⱼ), where {(rᵢ,Eᵢ)}ᵢ contains coordinates and chemical element of each atom, and {Rⱼ}ⱼ represents unit cell lattice vectors [13].

- Density of States (DOS): ρ(E) as a function of energy E [13].

- Charge Density: nₑ(r) as a function of position r [13].

- Textual Description: Machine-generated crystal descriptions obtained from Robocrystallographer [13].

2. Encoder Architecture:

- Separate neural network encoders were trained for each modality to learn parameterized transformations from raw data to embeddings in a shared latent space [13].

- The crystal structure encoder utilized PotNet, a state-of-the-art graph neural network [13].

- Encoders for DOS and charge density employed architectures suitable for their specific data structures [13].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multimodal Materials Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning Apparatus [7] | Experimental Setup | Controls morphology via flow rate, concentration, voltage, rotation speed, temperature/humidity | Fabricates nanofibers with controlled microstructures for dataset creation |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) [7] | Characterization | Captures microstructural features (fiber alignment, diameter, porosity) | Provides vision modality for microstructure-property relationship learning |

| Tensile Testing System [7] | Property Measurement | Quantifies mechanical properties (strength, modulus, elongation) | Generates ground truth property data for model training and validation |

| Materials Project Database [13] | Computational Resource | Provides crystal structures, DOS, charge density for diverse materials | Serves as primary data source for training foundation models like MultiMat |

| Robocrystallographer [13] | Text Generation | Automatically generates textual descriptions of crystal structures | Creates text modality for multimodal alignment without manual annotation |

Results and Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Multimodal approaches have demonstrated significant advantages over traditional single-modality methods across various material property prediction tasks. The integration of complementary information across scales enables more accurate and robust predictions even with limited data.

Table 3: Multimodal Framework Performance on Material Property Prediction Tasks

| Framework | Material System | Prediction Task | Performance Advantage | Key Capability Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatMCL [7] | Electrospun nanofibers | Mechanical property prediction | Improved prediction without structural information | Robustness to missing modalities |

| MatMCL [7] | Electrospun nanofibers | Microstructure generation | Generation from processing parameters | Cross-modal generation capability |

| MultiMat [13] [14] | Crystalline materials (Materials Project) | Multiple property prediction | State-of-the-art performance | Effective latent space representations |

| MultiMat [13] [14] | Crystalline materials | Material discovery | Screening via latent space similarity | Novel stable material identification |

Uncertainty Quantification Across Scales

The complexity of material response across scales introduces significant uncertainty, often representing the main source of uncertainty in engineering applications [12]. Recent work addresses this challenge by:

- Exploiting Model Hierarchy: Viewing the model at each scale as a function and the integral response as a composition of these functions enables bounding integral uncertainties using the uncertainty of each individual scale [12].

- Sensitivity Analysis: The hierarchical structure of multiscale modeling facilitates understanding the sensitivity of integral response to individual mechanisms—for example, the sensitivity of ballistic response to the critical resolved shear stress of a particular slip system [12].

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow from processing to performance with inverse design.

Future Directions and Implementation Recommendations

The integration of multimodal learning with multiscale modeling presents several promising research directions:

- Simultaneous Material and Structure Optimization: Recent work demonstrates that simultaneous optimization of a bi-material plate can lead to significantly better ballistic performance compared to sequential optimization [12]. This approach recognizes that different parts of a structure may have different property requirements [12].

- Data-Driven Computational Approaches: Emerging methods enable direct use of experimental data in computations without constitutive models by finding stress and strain fields that satisfy physical laws while best approximating available data [12]. This approach is particularly valuable with the rise of full-field diagnostic methods like digital image correlation and high-energy x-ray diffraction microscopy [12].

- Accelerated Computing Platforms: Implementing multiscale modeling requires repeated solution of models at individual scales, making efficient computation essential [12]. Recent work demonstrates how accelerators like GPUs can be effectively used by noting that nonlinear partial differential equations describing micromechanical phenomena decompose into universal physical laws (nonlocal) and material-specific constitutive models (local, spatially) [12].

For research teams implementing these approaches, we recommend starting with well-characterized material systems where multiple data modalities are already available, then progressively incorporating more challenging scale integrations while carefully quantifying uncertainty propagation across the modeling hierarchy.

In the field of materials science, the high cost and complexity of material synthesis and characterization have created a fundamental bottleneck: data scarcity and incompleteness [7]. This scarcity creates substantial barriers to training reliable machine learning models, directly impeding the pace of innovation in critical areas ranging from lightweight alloy development to novel drug delivery systems [7] [15]. While artificial intelligence has demonstrated remarkable success in accelerating material design, conventional single-modality approaches struggle with the multiscale complexity inherent to real-world material systems, which span composition, processing, microstructure, and properties [7]. Furthermore, crucial data modalities such as microstructure information are frequently missing from datasets due to high acquisition costs, creating significant challenges for comprehensive material modeling [7].

Multimodal Learning (MML) presents a paradigm shift in addressing these fundamental challenges. By integrating and processing multiple types of data—known as modalities—MML frameworks can enhance a model's understanding of complex material systems and mitigate data scarcity issues, ultimately improving predictive performance [7]. The ability to handle incomplete modalities while extracting meaningful relationships from available data makes MML particularly valuable for practical materials research where comprehensive characterization is often economically or technically infeasible. This technical guide explores the core architectures, methodologies, and experimental protocols that establish MML as a transformative approach for data-driven materials discovery.

Core MML Architectures for Materials Data

Multimodal learning architectures for materials science are specifically designed to process and integrate heterogeneous data types while remaining robust to missing information. These architectures typically employ specialized encoders for different data modalities, with fusion mechanisms that create unified material representations.

Structure-Guided Multimodal Learning

The MatMCL framework exemplifies a sophisticated approach to handling multiscale material information. This architecture employs separate encoders for different data types: a table encoder models the nonlinear effects of processing parameters, while a vision encoder learns rich microstructural features directly from raw characterization images such as SEM micrographs [7]. A multimodal encoder then integrates processing and structural information to construct a fused embedding representing the complete material system [7].

A critical innovation in MatMCL is its Structure-Guided Pre-training (SGPT) strategy, which aligns processing and structural modalities through contrastive learning in a joint latent space [7]. In this approach, the fused representation serves as an anchor that is aligned with its corresponding unimodal embeddings (processing conditions and structures) as positive pairs, while embeddings from other samples serve as negatives [7]. This architecture enables the model to handle scenarios where critical modalities (e.g., microstructural images) are missing during inference, making it particularly valuable for data-scarce environments.

Figure 1: MatMCL Framework Architecture for multimodal materials learning.

Mixture of Experts for Data-Scarce Scenarios

The Mixture of Experts (MoE) framework addresses data scarcity by leveraging complementary information across different pre-trained models and datasets [15]. This approach employs multiple expert neural networks (feature extractors), each pre-trained on different materials property datasets, along with a trainable gating network that conditionally routes inputs through the most relevant experts [15].

Formally, an MoE layer consists of m experts E_φ₁, ..., E_φₘ and a gating function G(θ, k) that produces a k-sparse, m-dimensional probability vector. The output feature vector f for a given input x is computed as:

where ⨁ is an aggregation function (typically addition or concatenation) [15]. This architecture automatically learns which source tasks and pre-trained models are most useful for a downstream prediction task, avoiding negative transfer from task interference while preventing catastrophic forgetting [15].

Foundation Models for Multimodal Materials

Multimodal Foundation Models for Materials (MultiMat) represent another architectural approach, enabling self-supervised multi-modality training on diverse material properties [16]. These models achieve state-of-the-art performance for challenging material property prediction tasks, enable novel material discovery via latent space similarity, and encode interpretable emergent features that may provide novel scientific insights [16].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Multimodal Contrastive Learning Protocol

The experimental protocol for structure-guided multimodal learning involves several critical phases. First, researchers construct a multimodal dataset through controlled material preparation and characterization. For electrospun nanofibers, this involves adjusting combinations of flow rate, concentration, voltage, rotation speed, and ambient conditions during preparation, followed by microstructure characterization using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and mechanical property testing via tensile tests [7].

The pre-training phase employs a geometric multimodal contrastive learning strategy. Given a batch containing N samples, processing conditions {xᵢᵗ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ, microstructure {xᵢᵛ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ, and fused inputs {xᵢᵗ, xᵢᵛ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ are processed by table, vision, and multimodal encoders, respectively, producing representations {hᵢᵗ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ, {hᵢᵛ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ, {hᵢᵐ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ [7]. A shared projector then maps these representations into a joint space for contrastive learning, producing {zᵢᵗ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ, {zᵢᵛ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ, {zᵢᵐ}ᵢ₌₁ᴺ [7]. The contrastive loss maximizes agreement between positive pairs (embeddings from the same material) while minimizing agreement for negative pairs (embeddings from different materials) [7].

For downstream tasks, the pre-trained encoders are frozen, and a trainable multi-task predictor is added to predict mechanical properties. This approach demonstrates robust performance even when structural information is missing during inference [7].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for multimodal materials learning.

Mixture of Experts Implementation

Implementing the MoE framework involves pre-training multiple feature extractors on different source tasks with sufficient data. Researchers then freeze these extractors and train only the gating network and property-specific head on the data-scarce downstream task [15]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance compared to pairwise transfer learning, outperforming it on 14 of 19 materials property regression tasks in comprehensive evaluations [15].

Synthetic Data Generation with MatWheel

The MatWheel framework addresses data scarcity through synthetic data generation, training material property prediction models using synthetic data created by conditional generative models [17]. Experiments in both fully-supervised and semi-supervised learning scenarios demonstrate that synthetic data can achieve performance close to or exceeding that of real samples in extreme data-scarce scenarios [17].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of multimodal learning approaches on materials property prediction tasks

| Framework | Approach | Key Innovation | Performance Advantages | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatMCL [7] | Structure-guided multimodal contrastive learning | Aligns processing and structural modalities in joint latent space | Enables accurate property prediction without structural information; generates microstructures from processing parameters | Data with missing modalities; processing-structure-property relationship mapping |

| MoE Framework [15] | Mixture of experts with gating mechanism | Leverages multiple pre-trained models; automatically identifies relevant source tasks | Outperforms pairwise transfer learning on 14 of 19 property regression tasks | Data-scarce downstream tasks; leveraging multiple source datasets |

| MultiMat [16] | Multimodal foundation model | Self-supervised multi-modality training on diverse material properties | State-of-the-art property prediction; enables material discovery via latent space similarity | Large-scale multimodal materials data; foundation model applications |

| MatWheel [17] | Synthetic data generation | Conditional generative models for creating training data | Achieves performance comparable to real samples in data-scarce scenarios | Extreme data scarcity; supplementing small datasets with synthetic examples |

Table 2: Experimental results demonstrating MML effectiveness in addressing data scarcity

| Experiment | Dataset Characteristics | Baseline Performance | MML Approach Performance | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Property Prediction [7] | Electrospun nanofibers with processing parameters and SEM images | Single-modality models fail with missing structural data | MatMCL maintains >90% prediction accuracy without structural information | Robustness to missing modalities |

| Data-Scarce Property Regression [15] | 941 piezoelectric moduli; 636 exfoliation energies; 1709 formation energies | Pairwise transfer learning limited by negative transfer | MoE outperforms TL on 14/19 tasks; comparable on 4/5 | Effective knowledge transfer from multiple sources |

| Synthetic Data Augmentation [17] | Data-scarce material property datasets from Matminer | Limited real samples lead to overfitting | MatWheel with synthetic data matches real sample performance | Addresses extreme data scarcity |

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for multimodal materials learning

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application in MML |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatQnA Dataset [18] | Benchmark dataset | Multi-modal evaluation for materials characterization | Contains 10 characterization methods (XPS, XRD, SEM, TEM, etc.) for validating MML capabilities |

| Electrospun Nanofiber Dataset [7] | Custom multimodal dataset | Processing-structure-property relationship mapping | Includes processing parameters, SEM images, and mechanical properties for framework validation |

| CGCNN [15] | Graph neural network | Feature extraction from crystal structures | Used as feature extractor in MoE framework; processes atomic structures |

| Con-CDVAE [17] | Conditional generative model | Synthetic data generation for materials | Creates synthetic training data in MatWheel framework to address data scarcity |

| FT-Transformer & ViT [7] | Transformer architectures | Encoders for tabular and image data | Used in Transformer-based MatMCL implementation for processing parameters and microstructures |

Multimodal learning represents a fundamental advancement in addressing the persistent challenges of data scarcity and incompleteness in materials science. By developing frameworks that can intelligently integrate information across diverse data types, handle missing modalities, and leverage complementary knowledge from multiple sources, MML enables robust predictive modeling even in data-constrained environments. The architectures and methodologies detailed in this guide—including structure-guided contrastive learning, mixture of experts, foundation models, and synthetic data generation—provide researchers with a powerful toolkit for accelerating materials discovery and development. As these approaches continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly critical role in unlocking the full potential of AI-driven materials research across diverse applications from energy storage to pharmaceutical development.

Frameworks in Action: Implementing Multimodal AI for Property Prediction and Drug Development

The field of materials science faces a unique challenge: material systems are inherently complex and hierarchical, characterized by multiscale information and heterogeneous data types spanning composition, processing, structure, and properties [7]. Capturing and integrating these multiscale features is crucial for accurate material representation and enhanced model generalization. Artificial intelligence is transforming computational materials science by improving property prediction and accelerating novel material discovery [14]. However, traditional machine-learning approaches often focus on single-modality tasks, failing to leverage the rich multimodal data available in modern materials repositories [14].

The integration of Transformer Networks, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and Contrastive Learning represents a paradigm shift in addressing these challenges. This architectural synergy enables researchers to model complex material systems more effectively by capturing long-range dependencies, local topological structures, and robust representations from limited labeled data. The resulting frameworks demonstrate remarkable potential for applications ranging from drug discovery and molecular property prediction to the design of novel materials with tailored characteristics [19] [7] [14].

Architectural Foundations and Integration Principles

Limitations of Isolated Architectures

Traditional Graph Neural Networks operate primarily through message-passing mechanisms, where node representations are updated by aggregating information from local neighbors [20]. While effective for capturing local topology, this approach suffers from several fundamental limitations: (1) Over-smoothing: Node representations become increasingly similar with network depth [20]; (2) Over-squashing: Information compression through bottleneck edges limits the flow of distant information [20]; and (3) Limited receptive field: Shallow GNNs struggle to capture long-range dependencies in graph structures [19]. These limitations are particularly problematic for non-homophilous graphs where connected nodes may belong to different classes or have dissimilar features [19].

Transformers, with their global self-attention mechanisms, can theoretically overcome these limitations by allowing each node to attend to all other nodes in the graph [20]. However, vanilla transformers applied to graphs face their own challenges: (1) Computational complexity: The self-attention mechanism scales quadratically with the number of nodes [19]; (2) Over-globalization: The attention mechanism may overemphasize distant nodes at the expense of meaningful local patterns [21]; and (3) Structural awareness: Standard transformers lack inherent mechanisms to encode graph topological information [20].

Integrated Architectural Framework

The complementary strengths and weaknesses of GNNs and Transformers naturally suggest integration strategies. Figure 1 illustrates a high-level blueprint for combining these architectures effectively within materials science applications.

Figure 1: Multi-view architecture integrating GNNs, Transformers, and feature views through contrastive learning.

The integrated framework creates multiple views of the same material data: (1) a local topology view processed by GNNs that captures neighborhood structures [19]; (2) a global context view processed by Transformers that captures long-range dependencies [19] [20]; and (3) a feature similarity view that connects nodes with similar characteristics regardless of graph connectivity [19]. Contrastive learning then aligns these views in a shared latent space, enabling the model to learn robust representations that integrate both structural and feature information [19] [7].

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Benchmarking on Graph Tasks

Table 1 summarizes the performance of integrated architectures against traditional methods across various graph learning benchmarks, particularly highlighting their robustness across different homophily levels.

Table 1: Performance comparison of integrated architectures against baselines

| Model | Homophilous Graphs (Accuracy) | Non-homophilous Graphs (Accuracy) | Long-Range Benchmark Performance | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard GNNs | 81.5-84.2% | 52.3-65.7% | Limited | High |

| Graph Transformers | 82.8-85.7% | 68.4-74.2% | Strong | Moderate |

| Integrated Architectures | 86.3-89.1% | 75.6-79.4% | State-of-the-art | Moderate-High |

Integrated architectures like Gsformer consistently outperform both GNNs and Transformers in isolation across diverse datasets [19]. The Edge-Set Attention (ESA) architecture, which treats graphs as sets of edges and interleaves masked and self-attention modules, has demonstrated particularly strong performance, outperforming fine-tuned message passing baselines and transformer-based methods on more than 70 node and graph-level tasks [20]. This includes challenging long-range benchmarks and heterophilous node classification where traditional GNNs struggle [20].

Materials Science Applications

Table 2 presents quantitative results for material property prediction and discovery tasks, demonstrating the practical impact of integrated architectures.

Table 2: Performance in materials science applications

| Application Domain | Model | Key Metric | Performance | Baseline Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material Property Prediction | MultiMat [14] | Prediction Accuracy | State-of-the-art | Exceeds single-modality approaches |

| Drug Discovery | Gsformer [19] | Binding Affinity Prediction | ~15% improvement | Superior to GNN-only models |

| Material Discovery | MatMCL [7] | Stable Material Identification | High accuracy via latent-space similarity | Enables screening of desired properties |

| Mechanical Property Prediction | MatMCL [7] | Property prediction without structural info | Robust with missing modalities | Outperforms conventional MML |

The MultiMat framework demonstrates how self-supervised multimodal training of foundation models for materials achieves state-of-the-art performance for challenging material property prediction tasks and enables novel material discovery via latent-space similarity [14]. Similarly, MatMCL provides a versatile multimodal learning framework that jointly analyzes multiscale material information and enables robust property prediction even with incomplete modalities [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Gsformer Implementation Framework

The Gsformer architecture exemplifies the integration principles for graph-structured data in scientific applications [19]:

View Construction:

- Original View: Uses the original graph structure with GNN encoders to capture local topological information.

- Long-Range Information View: Employs transformers with efficient attention mechanisms (e.g., treating each hop's neighbor information as a single token) to capture global dependencies while managing computational complexity.

- Feature View: Constructed based on node feature similarity to connect nodes with similar characteristics regardless of graph connectivity.

Contrastive Learning Framework: The model employs a multi-loss optimization strategy:

- Long-range information loss: Alments the original and long-range views

- Feature loss: Aligns the original and feature views

- Cross-module loss: Ensures consistency across all three views

Implementation Details:

- The original view and feature view share encoder parameters to bridge the gap between topological and feature spaces.

- The transformer component uses techniques inspired by NAGphormer to reduce the quadratic computational complexity of self-attention [19].

- The approach eliminates the need for positional encodings or other complex preprocessing steps required by many graph transformers [20].

Edge-Set Attention (ESA) Methodology

The ESA architecture provides an alternative approach that considers graphs as sets of edges [20]:

Encoder Design:

- Vertically interleaves masked and vanilla self-attention modules

- Masked attention restricts attention between linked primitives (for edges, connectivity translates to shared nodes)

- Self-attention layers expand on this information while maintaining strong relational priors

Advantages:

- Does not rely on positional, structural, or relational encodings

- Does not encode graph structures as tokens or use language-specific concepts

- Does not require virtual nodes, edges, or other non-trivial graph transformations

- Demonstrates strong performance in transfer learning settings compared to GNNs and transformers [20]

Multimodal Framework for Materials

For materials science applications, the MatMCL framework provides a comprehensive methodology [7]:

Structure-Guided Pre-training (SGPT):

- Employs a table encoder for processing parameters

- Uses a vision encoder for microstructural features from SEM images

- Implements a multimodal encoder to integrate processing and structural information

- Applies contrastive learning to align unimodal and multimodal representations

Downstream Adaptation:

- Enables property prediction with missing structural information

- Supports cross-modal retrieval for knowledge extraction

- Facilitates conditional generation of structures based on processing parameters

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3 presents essential computational "reagents" for implementing integrated architectures in materials research.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for integrated architecture implementation

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-hop Tokenization | Reduces computational complexity of graph attention | NAGphormer's Hop2Token module [19] |

| Masked Attention | Incorporates graph connectivity into attention mechanism | Edge-Set Attention connectivity masks [20] |

| Cross-Modal Projection | Aligns representations from different modalities | Shared projector in contrastive learning [7] |

| Dynamic Fusion | Adaptively weights modality importance | Learnable gating mechanisms [4] |

| KV Cache Mechanism | Improves computational efficiency in attention | AGCN cache for reduced overhead [21] |

| Pairwise Margin Contrastive Loss | Enhances discriminative capacity of attention space | AGCN implementation for graph clustering [21] |

Workflow Integration for Materials Research

Figure 2 illustrates a complete workflow for integrating these architectural blueprints into materials research and development pipelines.

Figure 2: End-to-end workflow for material discovery using integrated architectures.

This workflow demonstrates how the architectural integration enables practical materials research: (1) handling real-world data challenges like missing modalities [7], (2) facilitating cross-modal retrieval and generation to explore processing-structure-property relationships [7], and (3) leveraging latent-space similarity for efficient material discovery [14].

The integration of Transformer Networks, Graph Neural Networks, and Contrastive Learning represents a significant advancement in computational approaches for materials science. These architectural blueprints enable researchers to overcome fundamental limitations of isolated architectures while leveraging their complementary strengths. The resulting frameworks demonstrate robust performance across diverse tasks—from molecular property prediction and drug discovery to the design of novel materials with tailored characteristics.

The multi-view, contrastive approach provides particular value for materials science applications where data is often multimodal, limited, and incomplete. By effectively capturing both local and global information while learning robust representations from limited labeled data, these integrated architectures accelerate the discovery and design of novel materials. As materials datasets continue to grow in size and diversity, the flexibility and performance of these approaches will become increasingly essential for unlocking new scientific insights and technological innovations.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into materials science has revolutionized the design and discovery of novel materials, yet significant challenges persist in modeling real-world material systems. These systems exhibit inherent multiscale complexity spanning composition, processing, structure, and properties, creating formidable obstacles for accurate prediction and modeling [7]. While traditional AI approaches have demonstrated value, they frequently struggle with two critical issues: (1) missing modalities where important data types such as microstructure are often absent due to high acquisition costs, and (2) ineffective cross-modal alignment that fails to systematically bridge multiscale material knowledge [7]. The MatMCL framework emerges as a specialized solution to these challenges, providing a structure-guided multimodal learning approach that maintains robust performance even with incomplete data. This technical guide explores MatMCL's architecture, experimental protocols, and applications within the broader context of multimodal learning approaches for advanced materials research.

Core Architecture of MatMCL

Theoretical Foundation and Design Principles

MatMCL is built upon the fundamental premise that material systems are inherently multimodal, with complementary information distributed across different data types and scales. The framework's design incorporates three core principles:

- Structural Guidance: Microstructural features serve as anchoring points for aligning different modalities [7]

- Cross-Modal Alignment: Processing parameters and structural characteristics are projected into a unified latent space [7]

- Missing Modality Robustness: The architecture maintains predictive capability even when critical modalities (e.g., microstructure) are unavailable [7]

Component Architecture

The MatMCL framework comprises four integrated modules that work in concert to address the multimodal challenges in materials science:

- Structure-Guided Pre-training (SGPT) Module: Aligns processing and structural modalities through contrastive learning [7]

- Property Prediction Module: Enables mechanical property prediction even without structural information [7]

- Cross-Modal Retrieval Module: Facilitates knowledge extraction across different modalities [7]

- Conditional Generation Module: Generates microstructures based on processing parameters [7]

Framework Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete MatMCL workflow, from multimodal data input through pre-training to downstream applications:

Experimental Implementation

Multimodal Dataset Construction

To validate MatMCL's effectiveness, researchers constructed a specialized multimodal dataset focusing on electrospun nanofibers, selected for their well-characterized processing-structure-property relationships and relevance to advanced material applications [7].

Table 1: Electrospun Nanofiber Dataset Composition

| Data Category | Specific Parameters/Measurements | Acquisition Method | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Parameters | Flow rate, concentration, voltage, rotation speed, temperature, humidity | Controlled synthesis | Multiple combinations |

| Microstructural Data | Fiber alignment, diameter distribution, porosity | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Raw images |

| Mechanical Properties | Fracture strength, yield strength, elastic modulus, tangent modulus, fracture elongation | Tensile testing (longitudinal/transverse) | Direction-specific measurements |

The dataset was specifically designed to capture the processing-structure-property relationships crucial for understanding material behavior. A binary indicator was incorporated into processing conditions to specify tensile direction during mechanical testing [7].

Structure-Guided Pre-training (SGPT) Methodology

The SGPT module implements a sophisticated contrastive learning strategy to align different material modalities. The experimental protocol follows these key steps:

Input Processing:

- Processing parameters encoded using either MLP or FT-Transformer architectures [7]

- Microstructural SEM images processed through CNN or Vision Transformer (ViT) encoders [7]

- Multimodal inputs integrated through concatenation or cross-attention mechanisms [7]

Contrastive Learning Implementation:

- Batch processing of N samples: processing conditions {xᵢᵗ}, microstructure {xᵢᵛ}, fused inputs {xᵢᵗ, xᵢᵛ} [7]

- Representation generation through modality-specific encoders: {hᵢᵗ}, {hᵢᵛ}, {hᵢᵐ} [7]

- Projection into joint latent space via shared projector: {zᵢᵗ}, {zᵢᵛ}, {zᵢᵐ} [7]

- Contrastive loss calculation using fused representations as anchors [7]

Positive/Negative Pair Construction:

- Positive pairs: embeddings derived from same material (e.g., zᵢᵗ and zᵢᵐ) [7]

- Negative pairs: embeddings from different samples [7]

- Objective: Maximize agreement between positive pairs while minimizing agreement between negative pairs [7]

The training process demonstrates a consistent decrease in multimodal contrastive loss, indicating effective learning of correlations between processing conditions and nanofiber microstructures [7].

Property Prediction with Missing Modalities

The property prediction module addresses the critical challenge of missing structural information during inference:

Architecture Configuration:

- Pre-trained encoders and projector remain frozen during this phase [7]

- Trainable multi-task predictor head added for mechanical property estimation [7]

- Model leverages cross-modal understanding learned during SGPT to compensate for missing structural data [7]

Implementation Advantage: This approach enables accurate property prediction using only processing parameters, significantly reducing characterization costs and time while maintaining prediction reliability [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools for MatMCL Implementation

| Category | Specific Solution | Function in Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Material Synthesis | Electrospinning apparatus with parameter control | Generates nanofiber samples with varied processing conditions |

| Structural Characterization | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Captures microstructural features (fiber alignment, diameter, porosity) |

| Mechanical Testing | Tensile testing equipment with bidirectional capability | Measures mechanical properties (strength, modulus, elongation) |

| Data Processing | MLP/CNN or FT-Transformer/ViT architectures | Encodes tabular processing parameters and structural images |

| Multimodal Integration | Cross-attention mechanisms or feature concatenation | Fuses processing and structural information into unified representations |

| Representation Learning | Contrastive learning framework with projection head | Aligns modalities in joint latent space and enables missing modality robustness |

Technical Performance and Evaluation

Quantitative Results

MatMCL's performance was rigorously evaluated across multiple tasks, with key quantitative results summarized below:

Table 3: MatMCL Performance Metrics Across Different Tasks

| Task | Modality Condition | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Property Prediction | Complete modalities | Improved accuracy across multiple mechanical properties | Enhanced multiscale feature capture |

| Mechanical Property Prediction | Missing structural data | Maintained robust prediction capability | 30-50% reduction in error compared to standard methods |

| Microstructure Generation | Processing parameters only | High-fidelity SEM image generation | Enables structural prediction without experimental characterization |

| Cross-Modal Retrieval | Query with partial modalities | Accurate matching across modality boundaries | Facilitates knowledge transfer between material domains |

Framework Extension: Multi-Stage Learning

The MatMCL framework incorporates a multi-stage learning (MSL) strategy to extend its applicability to complex material systems:

This multi-stage approach enables knowledge transfer from simple nanofiber systems to complex composite materials, demonstrating MatMCL's scalability and generalizability for hierarchical material design [7].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Approaches

MatMCL represents one of several approaches addressing the missing modality challenge in multimodal learning. The broader research landscape includes complementary frameworks:

Chameleon Framework: Adopts a unification strategy that encodes non-visual modalities into visual representations, creating a common-space visual learning network that demonstrates notable resilience to missing modalities across textual-visual and audio-visual datasets [22].

Parameter-Efficient Adaptation: Employs feature modulation techniques (scaling and shifting) to compensate for missing modalities, requiring extremely small parameter overhead (fewer than 0.7% of total parameters) while maintaining performance across diverse multimodal tasks [23].

MatMCL distinguishes itself through its specific design for materials science applications, with demonstrated effectiveness in uncovering processing-structure-property relationships in complex material systems [7].

Implementation Considerations for Materials Research

Successful implementation of MatMCL requires attention to several technical considerations:

Data Requirements:

- Multimodal datasets with paired processing-structure-property measurements

- Sufficient sample diversity to capture complex material relationships

- Careful annotation of experimental conditions and parameters

Computational Resources:

- Transformer-based architectures require significant memory and processing capabilities

- Contrastive learning benefits from batch diversity, necessitating adequate batch sizes

- Multi-stage learning implementations require modular architecture design

Domain Adaptation:

- Framework transferability across different material classes (polymers, metals, ceramics)

- Scaling considerations for high-throughput material screening applications

- Integration with existing material informatics workflows and databases

The MatMCL framework establishes a robust foundation for AI-driven material design, particularly in scenarios characterized by data scarcity and modality incompleteness. Its structure-guided approach and missing modality robustness address critical challenges in computational materials science, offering a generalizable methodology for accelerating material discovery and optimization.

The high failure rate of drug combinations in late-stage clinical trials presents a major challenge in pharmaceutical development. Traditional models, which often rely on single data modalities like chemical structure, fail to capture the complex biological interactions necessary for accurate clinical outcome prediction [24] [25]. Madrigal (Multimodal AI for Drug Combination Design and Polypharmacy Safety) addresses this limitation through a unified architecture that integrates diverse preclinical data types to directly predict clinical effects [24].

This case study examines Madrigal's technical framework, detailing its multimodal learning approach and validation across multiple therapeutic areas. The content is framed within broader advances in multimodal learning for materials science, highlighting how architectural strategies for handling diverse data types are revolutionizing both biomedical and materials discovery [2] [3].

Madrigal Architecture & Technical Framework

Multimodal Data Integration

Madrigal integrates four primary preclinical data modalities, each capturing distinct aspects of drug pharmacology [24] [25]: