Mastering Energy Barriers in Catalysis: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Applications in Sustainable Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of energy barriers in catalytic processes, addressing the critical need for efficient catalyst design in sustainable chemistry and biomedical applications.

Mastering Energy Barriers in Catalysis: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Applications in Sustainable Chemistry

Abstract

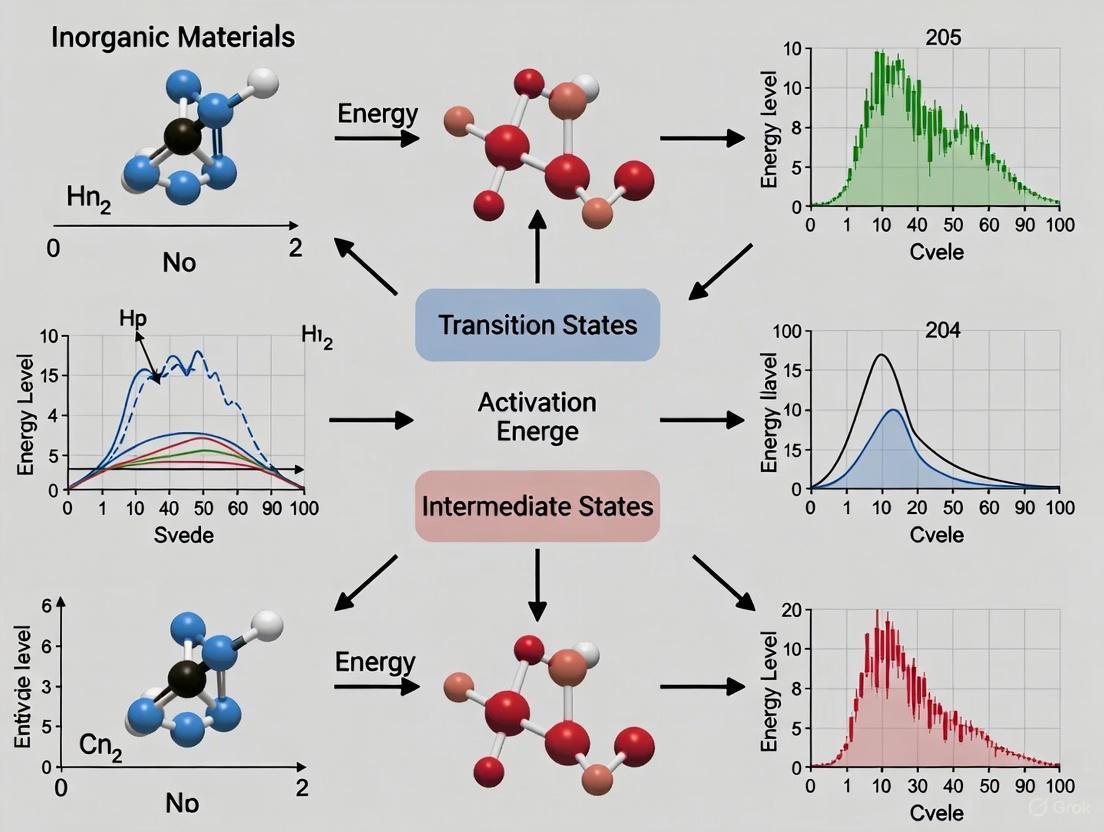

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of energy barriers in catalytic processes, addressing the critical need for efficient catalyst design in sustainable chemistry and biomedical applications. It establishes foundational principles by defining catalytic energy barriers and their role in reaction kinetics and selectivity. The content delves into cutting-edge computational methodologies, including machine learning force fields and active learning protocols, for accurate barrier prediction and reaction pathway exploration. Practical sections address common challenges in catalyst stability and deactivation, offering optimization strategies. Finally, the article covers validation techniques through case studies across energy conversion reactions and comparative analysis of catalyst classes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a robust framework for advancing catalytic efficiency and innovation.

The Fundamental Blueprint: Understanding Catalytic Energy Barriers and Reaction Kinetics

Catalytic processes occupy a central role in modern chemical and biochemical technologies, fundamentally characterized by their ability to accelerate chemical reaction rates without being consumed in the process [1]. The widely accepted mechanistic basis for this catalytic action is the lowering of the activation energy barrier through specific interactions between reactants and catalytic centers [1]. Activation energy is formally defined as the energy barrier that must be surmounted for reactants to transform into products, conceptually represented as the energy difference between the reactant state and the transition state complex [2]. This energy is quantitatively expressed through the Arrhenius equation (k = Ae^(-Ea/RT)), where k is the rate constant, A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature [3]. In catalytic systems, this barrier lowering is achieved through strategic stabilization of the transition state by the catalyst, which influences the energies of frontier molecular orbitals and facilitates easier reactant participation in transformation processes [1].

The interaction strength between catalysts and reactants is often quantified by adsorption heat, which correlates with catalytic activity through the empirical volcano plot relationship based on the Sabatier principle [1]. This principle suggests an optimal intermediate adsorption energy value for maximum catalytic efficiency, balancing reactant binding with product release. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and quantifying activation energies provides critical insights for rational catalyst design, reaction optimization, and predicting enzymatic behavior in biological systems.

Theoretical Frameworks: Transition State Theory

Foundations of Transition State Theory

Transition state theory (TST) provides the fundamental theoretical framework for understanding and quantifying activation energies in chemical reactions [3]. Developed simultaneously in 1935 by Henry Eyring and by Meredith Gwynne Evans and Michael Polanyi, TST explains reaction rates by assuming a special type of chemical equilibrium (quasi-equilibrium) between reactants and activated transition state complexes [3]. The theory posits three core principles: (1) reaction rates can be studied by examining activated complexes near the saddle point of a potential-energy surface; (2) these activated complexes are in quasi-equilibrium with reactant molecules; and (3) the activated complexes can convert into products, with kinetic theory calculating this conversion rate [3].

In mathematical terms, TST leads to the Eyring equation, which expresses the rate constant as k = (kBT/h) × exp(-ΔG‡/RT), where kB is Boltzmann's constant, h is Planck's constant, and ΔG‡ is the standard Gibbs energy of activation [3]. This formulation successfully addresses the physical interpretation of both the pre-exponential factor and activation energy parameters that were empirically observed in the earlier Arrhenius equation. For catalytic applications, TST provides a powerful connection between the thermodynamic properties of the transition state and kinetic observables, enabling researchers to deconstruct activation barriers into enthalpic (ΔH‡) and entropic (ΔS‡) components.

Advanced Theoretical Developments

Several sophisticated extensions to basic TST have been developed to address its limitations and improve accuracy for complex catalytic systems. Variational transition state theory (VTST) optimizes the dividing surface to minimize the TST reaction rate, effectively identifying the reaction coordinate in the vicinity of transition states [4]. For processes with stable intermediates along the pathway or reactions that occur in a non-concerted fashion, VTST provides a more accurate treatment than conventional TST.

Semiclassical transition state theory (SCTST), developed by Miller and coworkers, incorporates quantum effects automatically without requiring ad hoc corrections [4]. Based on the fundamental non-re-crossing assumption of TST, SCTST uses semiclassical correspondence principles to include vital quantum features such as vibrational zero-point energy and tunneling through potential energy barriers, while naturally accounting for inter-mode coupling among all degrees of freedom [4]. This approach achieves high accuracy comparable to extensively corrected conventional TST but with a more fundamental theoretical foundation.

For surface reactions, TST has been specifically adapted to account for the unique constraints of heterogeneous catalysis [4]. This formulation considers that each molecule occupies one elementary space with random distribution, while activated complexes occupy several adjacent elementary sites (s) with several possible positional configurations (g). The resulting statistical thermodynamic treatment enables calculation of reaction rates on surfaces accounting for site coverage and spatial arrangements of adsorbed species.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Frameworks for Analyzing Activation Energies

| Theory | Fundamental Principle | Key Equation | Application in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhenius Equation | Empirical temperature dependence of reaction rates | k = Ae^(-Ea/RT) | Initial estimation of activation barriers from kinetic data |

| Transition State Theory (TST) | Quasi-equilibrium between reactants and transition state | k = (k_BT/h) × exp(-ΔG‡/RT) | Connecting thermodynamic transition state properties with reaction rates |

| Variational TST (VTST) | Optimized dividing surface minimizing reaction rate | kmin = min[kTST(s)] | Improved accuracy for reactions with complex potential energy surfaces |

| Semiclassical TST (SCTST) | Incorporates quantum effects via semiclassical principles | kSCTST = κ·kTST (κ from semiclassical analysis) | Automated inclusion of ZPE, anharmonicity, and tunneling effects |

Computational Approaches for Energy Barrier Determination

Density Functional Theory in Catalysis Research

Density functional theory (DFT) has emerged as a cornerstone computational method for studying activation energies and reaction mechanisms in catalytic systems [5]. Based on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem, which establishes that the electronic energy of a molecular ground state is completely determined by electron density (ρ), DFT enables calculation of energy and electronic structure for molecular systems in different spatial configurations [5]. The fundamental energy expression in DFT is EDFT = T(ρ) + Ene(ρ) + J(ρ) + Exc(ρ), where T(ρ) represents kinetic energy, Ene(ρ) is nucleus-electron attraction energy, J(ρ) is Coulomb energy between electrons, and E_xc(ρ) is the exchange-correlation term [5].

For organic molecules and catalytic systems, the B3LYP hybrid functional has proven particularly successful, combining the Becke, Slater, HF exchange, LYP, and VWN5 correlation functionals to achieve accurate results across diverse chemical systems [5]. More recently, Truhlar's hybrid meta-functionals such as M06 and M06-2X have gained prominence for their broad applicability, particularly in transition metal chemistry and excited-state studies relevant to photocatalytic processes [5]. To address solvation effects critical for enzymatic and homogeneous catalytic systems, implicit solvation models like the Polarized Continuum Model (PCM) and its conductor-like modification (C-PCM) have been developed, treating the solvent as a continuum with uniform dielectric constant [5].

For large biochemical systems such as enzymes, hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approaches provide a practical solution by treating the region where chemical processes occur with accurate QM methods while modeling the larger system environment with computationally efficient molecular mechanics force fields [5]. This enables researchers to study catalytic mechanisms in biologically relevant systems with manageable computational cost.

Machine Learning Force Fields for Reaction Pathways

Recent advances in machine learning force fields (MLFFs) have created new paradigms for calculating activation energies in complex catalytic systems [6]. MLFFs bridge the gap between highly accurate but computationally expensive ab initio methods and empirically parameterized force fields that often lack sufficient accuracy for reaction barrier prediction [6]. Rather than performing new electronic structure calculations for each simulation step, MLFFs predict energy and forces for novel configurations using models trained on reference datasets, offering computational speedup while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy [6].

A key innovation in this domain is the development of automated training protocols for MLFFs capable of accurately determining energy barriers across entire catalytic reaction pathways [6]. These protocols employ active learning strategies where the model's uncertainty metric guides the selection of new configurations for DFT evaluation and inclusion in the training set [6]. When the local energy uncertainty of individual atoms exceeds a predefined threshold (typically 50 meV), new configurations are sampled and incorporated into the training dataset, systematically improving model accuracy in relevant regions of the potential energy surface [6]. This approach has been successfully validated for the hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to methanol over indium oxide, where the final force field achieved energy barriers within 0.05 eV of DFT reference values while enabling discovery of alternative reaction paths with significantly reduced activation energies [6].

Diagram 1: MLFF Training Workflow. Flowchart illustrating the iterative active learning protocol for developing machine learning force fields capable of accurately determining catalytic energy barriers [6].

Experimental Methods for Activation Energy Analysis

Kinetic Isotope Effects as Mechanistic Probes

Kinetic isotope effects (KIE) represent one of the most essential and sensitive experimental tools for studying reaction mechanisms and activation barriers [7]. Formally defined as the ratio of rate constants for reactions involving light (kL) and heavy (kH) isotopically substituted reactants (KIE = kL/kH), these effects arise primarily because heavier isotopologues have lower vibrational frequencies and consequently higher zero-point energies [7]. This ZPE difference translates to varying energy requirements to reach the transition state, thereby affecting reaction rates.

KIEs are classified as either primary kinetic isotope effects (PKIE), observed when a bond to the isotopically labeled atom is being formed or broken, or secondary kinetic isotope effects (SKIE), occurring when no bond to the labeled atom is broken or formed [7]. The magnitude of PKIEs can be substantial, especially for hydrogen/deuterium substitutions where the mass doubling leads to KIE values typically ranging from 6-10, whereas for carbon-12/carbon-13 substitutions, the effect is much smaller (approximately 4% rate difference) due to the smaller relative mass change [7]. For nucleophilic substitution reactions, SKIEs at the α-carbon provide a direct means to distinguish between SN1 and SN2 mechanisms, with SN1 reactions typically exhibiting large SKIEs approaching the theoretical maximum of about 1.22, while SN2 reactions yield SKIEs close to unity [7].

The theoretical foundation for interpreting KIEs was first formulated by Jacob Bigeleisen in 1949, employing transition state theory and statistical mechanical treatment of translational, rotational, and vibrational levels to calculate isotopic rate differences [7]. Modern applications combine experimental KIE measurements with computational chemistry, where accurate prediction of deuterium KIEs using density functional theory calculations has become routine, providing powerful mechanistic insights for catalytic reaction design [7].

Temperature-Dependent Kinetic Analysis

The temperature dependence of reaction rates provides direct experimental access to activation parameters through the Arrhenius equation [2]. By measuring rate constants at multiple temperatures and plotting ln(k) against 1/T, researchers obtain the activation energy (Ea) from the slope of the resulting line (-Ea/R). For catalytic systems, this approach enables quantification of how catalysts lower the activation barrier relative to the uncatalyzed reaction.

For enzyme-catalyzed reactions, the temperature dependence of catalytic rates follows the same fundamental principles but may exhibit more complex behavior due to the protein structural environment. The action of chorismate mutase, for example, provides a paradigm for understanding enzyme catalysis, as this structurally simple protein accelerates the concerted rearrangement of chorismate to prephenate by approximately 10^6- to 10^7-fold [8]. Studies applying the near-attack conformation (NAC) concept to this system have revealed that enzyme interactions stabilize a transition-state-like conformation, with the entirety of the catalytic acceleration attributable to this stabilization effect [8].

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Activation Energy Determination

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Key Measurements | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature-Dependent Kinetics | Arrhenius equation relationship between rate and temperature | Reaction rates at multiple temperatures | Experimental activation energy (E_a) from slope of ln(k) vs. 1/T plot |

| Primary Kinetic Isotope Effects | Vibrational frequency differences affecting ZPE | Rate ratio for light/heavy isotopes | Evidence of bond cleavage/formation to labeled atom in rate-determining step |

| Secondary Kinetic Isotope Effects | Hyperconjugation and steric effects in transition state | Rate ratio for light/heavy isotopes without bond cleavage | Transition state structure and degree of rehybridization |

| Transition State Analog Binding | Pauling's principle of transition state stabilization | Inhibition constants for transition state analogs | Quantitative assessment of transition state binding affinity |

Quantum Effects in Catalytic Energy Barriers

Quantum Catalysts and Non-Classical Interactions

Emerging research in quantum catalysts reveals the significant influence of non-classical quantum effects on activation energies in catalytic processes [9]. Quantum materials exhibit properties that cannot be explained by classical interactions alone, frequently involving non-weak (strong) electronic correlations, electronic orders (superconducting, spin-orbital), and multiple coexisting interdependent phases associated with quantum phenomena such as superposition and entanglement [9]. These quantum correlated catalysts (QCC) often arise from open-shell orbital configurations with unpaired electrons and demonstrate distinctive catalytic behaviors that transcend classical descriptions.

The fundamental electronic interactions in quantum catalysts include quantum spin exchange interactions (QSEI) and quantum excitation interactions (QEXI), which collectively constitute the non-classical quantum correlations between electrons [9]. QSEI represents the most relevant part of electronic quantum correlations, historically referred to as "exchange interaction" in orbital physics, while QEXI provides a clearer physical meaning for the traditionally undefined "correlation energy" concept [9]. These quantum corrections to electronic repulsions arise from quantum entanglement between electrons with the same spin (QSEI) and quantum superposition of configurations (QEXI), producing tangible energetic influences on catalytic activation barriers [9].

The advanced incorporation of fundamental orbital physics in solid-state quantum catalysts is increasingly leading the technological transition toward a greener and more sustainable economy [9]. As the field progresses, direct recognition of the differentiating role of quantum correlations promises more complete theoretical descriptions of catalytic action beyond simplified models of non-correlated electrons, parametrizations, and linearizations that have traditionally dominated catalysis science [9].

Tunneling and Nuclear Quantum Effects

Quantum tunneling represents another significant quantum phenomenon that influences activation energies in catalytic systems, particularly for reactions involving hydrogen transfer [8]. During the enzymatically catalyzed rearrangement of chorismate to prephenate, for instance, quantum tunneling plays a vital role in hydrogen transfer processes, challenging purely classical interpretations of activation barriers [8]. This realization has prompted the development of theoretical formulations that incorporate tunneling contributions to reaction rates, moving beyond "ultrasimple" versions of transition-state theory [8].

The contribution of quantum tunneling to chemical reactions becomes particularly significant for reactions with high activation barriers and light particles, where classical mechanics would predict negligible reaction rates at physiological temperatures. For enzyme-catalyzed reactions, the protein environment appears to optimize not only transition state stabilization but also tunneling pathways, enhancing reaction rates beyond what would be expected from classical Arrhenius behavior [8]. Computational approaches such as semiclassical transition state theory automatically incorporate these tunneling effects, providing more accurate predictions of reaction rates without requiring ad hoc corrections [4].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Energy Barrier Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds (^2H, ^13C, ^15N, ^18O) | KIE studies for mechanistic analysis | Experimental determination of rate-limiting steps and transition state structure |

| Transition State Analog Inhibitors | Quantitative assessment of transition state stabilization | Measurement of enzyme-transition state binding affinity |

| Density Functional Theory Codes (Gaussian, ORCA, VASP) | Computational calculation of reaction pathways and barriers | Prediction of activation energies and transition state geometries |

| Machine Learning Force Field Platforms (AMPTorch, SchNet) | High-throughput screening of catalytic reaction pathways | Rapid exploration of complex reaction networks with quantum accuracy |

| Quantum Chemistry Basis Sets (cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, 6-31G*) | Atomic orbital basis for electronic structure calculations | Balanced accuracy/efficiency for catalytic cluster calculations |

| Continuum Solvation Models (PCM, SMD, COSMO) | Incorporation of solvent effects in computational studies | Realistic modeling of homogeneous catalytic and enzymatic systems |

Diagram 2: Catalytic Energy Barrier Reduction. Illustration of how catalysts provide an alternative reaction pathway with reduced activation energy (E_a) compared to the uncatalyzed reaction (E_a⁰) through transition state stabilization [1] [2].

The concept of activation energy remains fundamental to understanding and designing catalytic processes across heterogeneous, homogeneous, and enzymatic systems. Transition state theory provides the theoretical foundation for quantifying these energy barriers, while modern computational methods like density functional theory and machine learning force fields enable precise prediction of activation energies across diverse catalytic systems. Experimental techniques such as kinetic isotope effects and temperature-dependent kinetics provide critical validation of computational predictions and mechanistic hypotheses. Emerging recognition of quantum effects in catalysis—including strong electronic correlations, entanglement, and tunneling—promises to expand our understanding beyond classical descriptions, enabling more sophisticated catalyst design strategies. For drug development professionals and researchers, mastering these complementary approaches to activation energy analysis provides powerful tools for rational optimization of catalytic processes in both industrial and biological contexts.

The Role of Energy Barriers in Determining Reaction Rates and Selectivity

In the realm of chemical engineering and catalysis research, energy barriers represent the fundamental kinetic parameters that dictate the feasibility, rate, and selectivity of chemical reactions. These barriers, quantitatively expressed as activation energy (Eₐ), constitute the minimum energy input required to transform reactant molecules into products through a high-energy transition state [10]. Catalysts function primarily by providing alternative reaction pathways with significantly reduced activation energies, thereby accelerating reaction rates without being consumed in the process [10]. The profound impact of these barriers extends beyond simple rate enhancement to precisely control which reaction pathways become accessible among competing options, ultimately determining product distribution in complex reaction networks. This principle is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical development, where selective catalysis can dictate the efficiency of synthetic routes and the purity of final drug compounds.

Within the framework of Transition State Theory (TST), the transition state is conceptualized as a high-energy, short-lived configuration of atoms that exists during the conversion of reactants to products [10]. The energy required to reach this state from the reactants is the activation energy. By lowering this energy, catalysts increase the reaction rate by enabling more molecular collisions to overcome the energy barrier at a given temperature. This relationship is mathematically captured by the Arrhenius equation: ( k = A e^{-Ea/RT} ), where ( k ) represents the rate constant, ( A ) is the pre-exponential factor (frequency of collisions), ( R ) is the universal gas constant, and ( T ) is the temperature in Kelvin [10]. From this equation, it is evident that even modest reductions in Eₐ yield substantial increases in reaction rates, underscoring the transformative power of effective catalyst design.

Theoretical Foundations: From Single Transition States to Complex Ensembles

The Evolution of Transition State Theory

Traditional Transition State Theory has historically operated on the assumption of a well-defined, unique transition state structure representing the saddle point on a potential energy surface [11]. However, contemporary research reveals that this model represents an oversimplification for many complex systems, particularly in enzymatic and condensed-phase environments. The recognition that proteins and catalytic systems exist as large ensembles of conformations has necessitated a paradigm shift toward understanding the implications of this structural diversity on the nature of the transition state [12].

Transition-State Ensembles in Enzyme Catalysis

Groundbreaking research on adenylate kinase (Adk) has provided compelling evidence for the existence of a transition-state ensemble (TSE) rather than a single, unique transition state. Through quantum-mechanics/molecular-mechanics (QM/MM) calculations, researchers discovered a structurally diverse set of energetically equivalent configurations along the reaction coordinate for the phosphoryl-transfer step [12]. This broad TSE, characterized by a conformationally delocalized set of structures including asymmetric transition states, is rooted in the macroscopic nature of the enzyme. The study demonstrated that the fully charged nucleotide state exhibited a much smaller free energy of activation (ΔfG‡ of 13 ± 0.9 kcal/mol) compared to the monoprotonated state (ΔfG‡ of 23 ± 0.9 kcal/mol), establishing the charged state as the more reactive configuration [12]. This TSE model resolves what would otherwise be a significant entropic bottleneck if enzymes had to pass through a single, unique transition state amidst their vast conformational landscape.

Virtual Transition States for Complex Reaction Networks

For reactions involving multiple elementary steps either in series or parallel, the concept of virtual transition states provides a powerful framework for interpreting experimental kinetic data. When multiple transition states have similar energies, experimental measurements provide information not about any individual transition state but rather about a weighted average of them—the virtual transition state [11]. Schowen defined this entity as a 'virtual transition-state structure,' which represents the statistically weighted average of contributing real transition states [11]. This concept considerably simplifies the treatment of kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) for enzymatic reactions and enhances the application of computational methods to interpret experimental kinetics for complex mechanisms. The key principles governing virtual transition states include:

- Multiple TSs in parallel: The virtual TS is lower in energy than each individual real TS

- Multiple TSs in series: The virtual TS is higher in energy than each individual real TS [11]

Diagram: Virtual TS in Parallel vs. Series Pathways

Quantitative Analysis of Catalytic Performance

Performance Metrics for Single-Atom Catalysts in CO-SCR

The selective catalytic reduction of NO by CO (CO-SCR) represents an environmentally important reaction where single-atom catalysts (SACs) demonstrate exceptional performance by optimizing energy barriers for specific pathways. The table below summarizes the catalytic performance of various SACs under different reaction conditions, highlighting the critical relationship between catalyst structure, energy barriers, and resultant selectivity [13].

Table 1: Catalytic Performance of Single-Atom Catalysts in CO-SCR

| Catalyst Sample | Reaction Conditions | Temperature (°C) | NO Conversion (%) | N₂ Selectivity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ir₁/m-WO₃ | 0.1% NO, 0.2% CO, 2% O₂, GHSV=50,000 h⁻¹ | 350 | 73 | 100 | [13] |

| 0.3Ag/m-WO₃ | 0.1% NO, 0.4% CO, 1% O₂, GHSV=50,000 h⁻¹ | 250 | ~73 | 100 | [13] |

| 5Ag/m-WO₃ | 0.1% NO, 0.4% CO, 1% O₂, GHSV=50,000 h⁻¹ | 250 | ~64 | 100 | [13] |

| Cr₀.₁₉Rh₀.₀₆CeO₂ | 0.5% NO, 1.0% CO, GHSV=6,500 h⁻¹ | 120 | 100 | ~34 | [13] |

| Cr₀.₁₉Rh₀.₀₆CeO₂ | 0.5% NO, 1.0% CO, GHSV=6,500 h⁻¹ | 200 | 100 | 100 | [13] |

| Fe₁/CeO₂-Al₂O₃ | 0.05% NO, 0.6% CO, GHSV=30,000 h⁻¹ | 250 | 100 | 100 | [13] |

| Fe₁/Al₂O₃ | 0.05% NO, 0.6% CO, GHSV=30,000 h⁻¹ | 400 | 100 | ~100 | [13] |

| 0.2Rh/CeO₂-Octahedron | 0.09% NO, 0.11% CO, 2.5% H₂O, 225 L·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ | 266 | 100 | / | [13] |

| Cu₁-MgAl₂O₄ | 2.6% NO, 2.9% CO, 12 L·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ | 300 | ~93 | ~92 | [13] |

The performance data reveals several critical trends in energy barrier manipulation. First, the presence of single atoms significantly enhances the adsorption and activation of NO through synergistic interactions with the support material, thereby lowering the activation energy for the rate-determining step [13]. Second, the coordination environment and metal-support interactions can be systematically tuned to further reduce energy barriers for desired pathways while increasing barriers for competing reactions, resulting in enhanced selectivity [13]. The remarkable N₂ selectivity observed across multiple SAC systems demonstrates the precise control over reaction pathways achievable through atomic-level catalyst design.

Mathematical Modeling of Energy Barriers

The quantitative relationship between energy barriers and reaction rates is mathematically formalized through the Arrhenius equation and its derivations. The fundamental Arrhenius equation, ( k = A e^{-Ea/RT} ), directly correlates the rate constant ( k ) with the activation energy ( Ea ) [10]. A more sophisticated treatment incorporates both enthalpic (ΔH‡) and entropic (ΔS‡) contributions through the Eyring equation: [ k = \frac{kB T}{h} e^{-\frac{ΔH‡}{RT} + \frac{ΔS‡}{R}} ] where ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant and ( h ) is Planck's constant [10]. This equation highlights that the activation free energy ΔG‡ = ΔH‡ - TΔS‡ represents the true kinetic bottleneck, with catalysts functioning to minimize this composite parameter rather than just the enthalpic component.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Advanced Computational Workflows for Energy Barrier Mapping

Modern computational approaches have revolutionized our ability to map complex energy landscapes and identify transition states with high precision. The autoplex framework represents an automated implementation of iterative exploration and machine-learning interatomic potential (MLIP) fitting through data-driven random structure searching [14]. This approach enables the comprehensive mapping of potential energy surfaces, including highly unfavorable regions essential for understanding reaction pathways and energy barriers.

Protocol: Automated Potential-Energy Surface Exploration with autoplex

- Initialization: Define the chemical system and relevant stoichiometric space

- Random Structure Searching (RSS): Generate diverse initial configurations covering possible minima and transition regions

- Quantum Mechanical Evaluation: Perform DFT single-point calculations on selected structures (typically requiring 100s-1000s of evaluations)

- Machine Learning Potential Training: Iteratively fit MLIPs (e.g., Gaussian Approximation Potentials) to the accumulating DFT data

- Active Learning: Use error estimates to identify underrepresented regions of configuration space for subsequent sampling

- Validation: Assess model performance on known benchmark structures and experimental data [14]

This automated workflow has demonstrated remarkable efficiency, achieving quantum-mechanical accuracy (errors < 0.01 eV/atom) for diverse systems including silicon allotropes, TiO₂ polymorphs, and complex binary titanium-oxygen phases [14]. The framework significantly reduces the manual effort traditionally required for comprehensive potential-energy surface mapping, enabling researchers to focus on mechanistic interpretation rather than computational technicalities.

Diagram: autoplex Workflow for MLIP Development

QM/MM Protocol for Enzymatic Energy Barriers

For enzymatic systems, hybrid quantum-mechanics/molecular-mechanics (QM/MM) approaches provide the methodological foundation for computing energy barriers with chemical accuracy while accounting for the complex protein environment.

Protocol: QM/MM Calculation of Phosphoryl-Transfer in Adenylate Kinase

- System Preparation:

- Obtain starting structure from X-ray crystallography (e.g., PDB: 2RGX)

- Build substrate coordinates (ADP-ADP) using inhibitor complexes (Ap5A) as templates

- Replace native metal ions with physiologically relevant species (e.g., Zn²⁺ to Mg²⁺)

QM/MM Partitioning:

- QM Region: Diphosphate moiety of both ADP molecules, Mg²⁺ ion, four coordinating water molecules (described with SCC-DFTB)

- MM Region: Remainder of protein and solvent (described with AMBER ff99sb force field, TIP3P water)

Free Energy Calculations:

- Perform Multiple Steered Molecular Dynamics in both forward (ADP/ADP to ATP/AMP) and reverse directions

- Determine free energy profiles using Jarzynski's Relationship: ( e^{-\beta ΔF} = \langle e^{-\beta W} \rangle )

- Compare multiple protonation states to identify most reactive configuration [12]

This protocol enabled the identification of the transition-state ensemble for the phosphoryl-transfer reaction and revealed the dramatically reduced free energy of activation (ΔfG‡ of 13 ± 0.9 kcal/mol) for the fully charged nucleotide state compared to the monoprotonated state (ΔfG‡ of 23 ± 0.9 kcal/mol) [12].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Energy Barrier Studies

| Category | Item/Software | Specific Function in Energy Barrier Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Methods | QM/MM (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) | Models chemical reactions in protein environments with quantum accuracy for active site [12] |

| Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Enables large-scale simulations with quantum fidelity for complex systems [14] | |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Provides reference electronic structure calculations for training MLIPs [14] | |

| Random Structure Searching (RSS) | Explores configurational space to identify minima and transition states [14] | |

| Software Frameworks | autoplex | Automated workflow for MLIP development and potential-energy surface exploration [14] |

| eSEN Neural Network Potentials | Equivariant transformer architecture for molecular modeling [15] | |

| Datasets & Resources | Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) | Massive dataset of 100M+ quantum calculations for biomolecules, electrolytes, metal complexes [15] |

| Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) | Pre-trained neural network potential unifying multiple datasets [15] | |

| Experimental Validation | Temperature-Dependent Kinetics | Determines activation parameters (Eₐ, ΔH‡, ΔS‡) from Arrhenius/EYring plots [12] |

| Kinetic Isotope Effects (KIEs) | Probes transition state structure through isotopic substitution [11] |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Foundational Models and Large-Scale Datasets

The recent release of Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) represents a transformative development in the computational analysis of energy barriers. This massive dataset comprises over 100 million quantum chemical calculations requiring over 6 billion CPU-hours to generate, with unprecedented coverage of biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes [15]. All calculations were performed at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory, ensuring consistent high accuracy across diverse chemical spaces [15]. The accompanying Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) implements a novel Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) architecture that enables knowledge transfer across disparate datasets computed with different theoretical methods, significantly advancing the accuracy and transferability of machine-learned interatomic potentials [15].

Implications for Pharmaceutical and Catalyst Development

The evolving understanding of energy barriers, particularly the recognition of transition-state ensembles rather than unique transition states, has profound implications for rational drug and catalyst design. In pharmaceutical development, the TSE concept suggests new strategies for designing transition-state analog inhibitors that account for the dynamic nature of enzyme active sites [12]. For industrial catalysis, the ability to precisely manipulate energy barriers through atomic-level control of coordination environments—as demonstrated by SACs in CO-SCR—enables the design of catalysts with unprecedented selectivity profiles [13]. The integration of automated computational workflows like autoplex with experimental validation creates a powerful feedback loop for accelerating the discovery and optimization of catalytic systems tailored to specific energy barrier landscapes.

The continued advancement in mapping and manipulating energy barriers promises to unlock new reaction pathways with optimized selectivity and efficiency, directly impacting pharmaceutical synthesis, renewable energy technologies, and environmental remediation. As computational methods become increasingly integrated with automated experimentation, the precise engineering of energy barriers will undoubtedly emerge as the central paradigm for controlling chemical reactivity across diverse applications.

The Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relationship represents one of the most fundamental principles in catalysis research, establishing a quantitative connection between reaction thermodynamics and kinetics. This empirical linear relationship between activation energy and reaction enthalpy provides researchers with a powerful predictive tool for estimating kinetic barriers from readily computable thermodynamic properties. This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundation of BEP relations, their application across heterogeneous and electrocatalysis, experimental and computational validation methodologies, and emerging strategies for overcoming their limitations in catalyst design. Within the broader context of energy barrier optimization in catalytic processes, understanding BEP principles has become indispensable for rational catalyst development across energy conversion, chemical synthesis, and environmental technologies.

The Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) principle, also referred to as the Bell-Evans-Polanyi principle or Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi principle, represents a cornerstone concept in physical chemistry that quantitatively links the kinetics and thermodynamics of chemical reactions [16]. This linear energy relationship formally states that the difference in activation energy between two reactions of the same family is proportional to the difference in their enthalpy of reaction [16].

The BEP relationship can be mathematically expressed as:

Ea = E0 + αΔH

Where:

- Ea represents the activation energy of the reaction

- E0 denotes the intrinsic activation energy barrier when the reaction enthalpy is zero

- ΔH signifies the reaction enthalpy

- α is a transfer coefficient (0 ≤ α ≤ 1) that indicates the position of the transition state along the reaction coordinate [16]

The fundamental physical significance of the α parameter lies in characterizing how closely the transition state resembles the reactants or products. When α approaches 0, the transition state occurs early along the reaction coordinate and resembles the reactants. When α approaches 1, the transition state occurs late and resembles the products. The BEP model operates under the key assumption that the pre-exponential factor in the Arrhenius equation and the position of the transition state remain consistent for all reactions within a particular family [16].

Theoretical Foundation and Historical Context

The BEP relation emerged from independent work by Brønsted in acid-base catalysis and by Evans and Polanyi in hydrogen atom transfer reactions, establishing that reactions within the same family exhibit predictable linear correlations between activation energies and thermodynamic driving forces. This principle has since been validated across diverse reaction classes, from simple elementary steps to complex catalytic processes.

The theoretical underpinning of BEP relations arises from the linear dependence of potential energy surfaces near the transition state. For elementary reactions involving bond cleavage or formation, the activation barrier often correlates linearly with the thermochemistry of the process. This correlation enables researchers to extrapolate kinetic information from thermodynamic data, significantly reducing the computational and experimental burden in catalyst screening.

In the context of catalyst design, BEP relations provide a foundational framework for understanding volcano plots, where catalytic activity reaches a maximum at intermediate adsorption energies. This connection arises because the BEP relation directly links the adsorption energy of intermediates (a thermodynamic property) to the activation barriers for elementary steps (kinetic properties) [17]. The mathematical formulation enables high-throughput computational screening of catalyst materials by leveraging easily computable thermodynamic descriptors to predict kinetic performance.

Applications in Catalysis Research

Heterogeneous Catalysis

In heterogeneous catalysis, BEP relations have proven particularly valuable for understanding and predicting catalyst performance across transition metal surfaces. A seminal study by Bligaard et al. demonstrated that universal BEP relations exist for the dissociation of diatomic molecules (N2, CO, NO, O2) on stepped transition metal surfaces [17]. This discovery revealed that despite chemical differences, these dissociation reactions follow similar linear correlations between activation energy and reaction energy across different metal catalysts.

The application of BEP relations naturally leads to the emergence of volcano curves in heterogeneous catalysis when catalytic activity is plotted against the dissociative chemisorption energy of key reactants [17]. This pattern reflects the Sabatier principle, where optimal catalysts bind reaction intermediates neither too strongly nor too weakly. For CO hydrogenation to methane, the BEP relation explains why metals with intermediate CO dissociation energies (such as Co and Ru) exhibit maximum activity, while metals with very strong (Re) or very weak (Cu) CO binding show lower activity [18].

Table 1: BEP Parameters for Diatomic Molecule Dissociation on Transition Metal Surfaces

| Molecule | Reaction Family | Typical α Value | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO | Carbon monoxide dissociation | ~0.9 | Methanation, Fischer-Tropsch synthesis |

| N2 | Nitrogen dissociation | ~0.8 | Ammonia synthesis |

| H2 | Hydrogen dissociation | ~0.3-0.5 | Hydrogenation reactions |

| O2 | Oxygen dissociation | ~0.7 | Oxidation reactions |

Electrochemical Reactions

The BEP framework has been successfully extended to electrochemical systems, particularly the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), a critical process for sustainable hydrogen production [19]. For HER, the activation free energy (ΔG‡) follows a BEP-type relationship with the hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH):

ΔG‡ = ΔG0‡ + α|ΔGH|

Where ΔG0‡ represents the intrinsic activation barrier for the optimal catalyst with ΔGH = 0 (approximately 0.7 eV) [19]. This relationship holds for both Volmer-Heyrovsky and Volmer-Tafel mechanisms and enables prediction of HER activity across different metal electrodes.

Recent studies using constant electrode potential density functional theory calculations have confirmed that HER kinetic barriers correlate strongly with hydrogen adsorption energies, validating the BEP relationship for electrocatalytic systems [20]. The research revealed that adsorption energies at less favorable sites (e.g., top sites) sometimes provide better correlation with kinetic barriers than strongly binding sites (e.g., hollow sites), offering improved accuracy for predicting HER performance [20].

Photocatalysis

BEP relationships have also been identified in photocatalytic processes. In photocatalytic H2O2 production, a BEP-like relation governs the adsorption and desorption of H+ species on modified graphitic carbon nitride surfaces [21]. This relationship mirrors patterns observed in thermal catalytic processes like ammonia synthesis, where stronger adsorption lowers dissociation barriers but increases desorption energies, creating an optimization challenge.

The observation of BEP relations in photocatalysis suggests that similar fundamental principles govern energy barriers across thermal, electrochemical, and photocatalytic systems. This unifying framework enables knowledge transfer between different catalysis subfields and provides consistent strategies for catalyst optimization.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Computational Determination of BEP Relations

Density functional theory calculations serve as the primary tool for establishing BEP relationships in modern catalysis research. The standard protocol involves:

Surface Modeling: Construct representative surface models (e.g., fcc(111), fcc(100), fcc(110) for metals) with appropriate periodic boundary conditions.

Adsorption Energy Calculations: Compute the adsorption energies of reactants, products, and key intermediates at multiple surface sites.

Transition State Optimization: Locate transition states using nudged elastic band (NEB) or dimer methods to determine activation barriers.

BEP Correlation Analysis: Plot activation energies (Ea) against reaction energies (ΔE or ΔH) for a series of similar catalysts to establish linear relationships.

For electrochemical systems, constant electrode potential DFT methods are essential for accurately modeling potential-dependent activation barriers [20]. This approach maintains a constant electron chemical potential during calculations, more closely mimicking experimental electrochemical conditions.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Computational BEP Analysis

| Parameter | Calculation Method | Significance in BEP Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energy (ΔEads) | DFT energy difference between adsorbed and gas-phase species | Serves as descriptor for reaction energy |

| Activation Energy (Ea) | NEB or dimer method between initial and transition states | Dependent variable in BEP correlation |

| d-Band Center | Projected density of states of surface d-orbitals | Electronic descriptor linking structure to activity |

| Reaction Energy (ΔE) | DFT energy difference between products and reactants | Independent variable in BEP correlation |

Experimental Validation Techniques

Experimental validation of BEP relationships requires precise measurement of both kinetic and thermodynamic parameters:

Activation Energy Determination:

- Temperature-dependent reaction rate measurements following Arrhenius analysis

- Transient kinetic analysis for complex reaction networks

- Steady-state isotopic transient kinetic analysis (SSITKA) for surface residence times

Thermodynamic Parameter Assessment:

- Calorimetric measurements of adsorption heats

- Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) for binding energies

- In situ spectroscopy for intermediate identification and quantification

For HER catalysis, experimental validation involves correlating exchange current densities (kinetic parameter) with hydrogen binding energies (thermodynamic parameter) determined from desorption peak potentials or theoretical calculations [19]. The resulting volcano-shaped relationship provides strong experimental support for the BEP principle in electrocatalysis.

Advanced Concepts and Current Research Frontiers

Breaking BEP Relations with Advanced Catalyst Designs

While BEP relations provide valuable predictive power, their linear scaling also imposes fundamental limitations on catalyst optimization by tightly coupling activation energies to reaction energies. Recent research has focused on designing catalyst architectures that break these scaling relations to achieve unprecedented activity [22].

Dual-metal site catalysts (DMSCs) have demonstrated particular promise for breaking BEP relations. In methane coupling reactions, heteronuclear DMSCs on ceria supports enable decoupling of activation energies from overall reaction energies through mixed low-affinity/high-affinity coadsorption of reaction intermediates [22]. This architecture allows one metal site to primarily determine the activation barrier while both sites collectively influence the reaction energy, breaking the conventional BEP scaling.

Machine Learning and Data Analytics Approaches

Advanced data analytics methods are increasingly being applied to identify descriptors beyond conventional BEP relationships. The SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) algorithm can identify optimal descriptors from billions of candidate features by combining primary physical properties with mathematical operators [23]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for single-atom alloy catalysts, where conventional d-band center models and BEP relations often fail due to the unique electronic structures of isolated metal atoms on host surfaces [23].

Compressed-sensing data analytics enables rapid screening of catalyst candidates by identifying simple mathematical expressions that accurately predict adsorption energies and activation barriers based solely on properties of host surfaces and guest single atoms [23]. This methodology reduces computational costs by several orders of magnitude compared to conventional DFT-based screening.

Limitations and Boundary Conditions

While BEP relations apply broadly across catalysis, important exceptions and limitations exist:

Reactions with changing mechanisms across different catalysts may not follow consistent BEP relationships.

Single-atom and highly structured catalysts often deviate from BEP correlations observed on extended surfaces due to their unique electronic structures [23].

Reactions involving significant electronic reorganization or multiple electron transfers may violate simple BEP scaling.

Solvent effects in electrochemical systems can complicate BEP relationships by introducing additional thermodynamic contributions.

Understanding these boundary conditions is essential for appropriate application of BEP principles in catalyst design.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for BEP Relationship Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Chemistry Software | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, GPAW | DFT calculations of adsorption energies and activation barriers |

| Transition State Search Tools | Nudged Elastic Band (NEB), Dimer Method | Location of transition states and minimum energy pathways |

| Electronic Structure Analysis | d-Band Center Calculation, Bader Charge Analysis | Electronic descriptor determination for catalyst properties |

| Experimental Characterization | Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD), Calorimetry | Measurement of adsorption energies and reaction heats |

| Electrochemical Analysis | Rotating Disk Electrode (RDE), Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Determination of exchange current densities and activation barriers |

| Data Analytics Tools | SISSO Algorithm, Principal Component Analysis | Identification of optimal descriptors from high-dimensional data |

The Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi relationship continues to serve as a fundamental pillar in catalysis research, providing an essential bridge between reaction thermodynamics and kinetics. Its quantitative formulation enables efficient computational screening of catalyst materials and offers deep theoretical insights into activity trends across different catalyst families. While traditional BEP relations have proven remarkably transferable across diverse catalytic systems, emerging research focuses on developing advanced catalyst architectures that break these scaling relationships to achieve unprecedented catalytic performance. As computational methods advance and fundamental understanding of catalytic mechanisms deepens, the BEP framework will continue to evolve, maintaining its central role in the rational design of energy-efficient catalytic processes for chemical synthesis, energy conversion, and environmental protection.

The pursuit of sustainable energy solutions is inextricably linked to the development of advanced catalytic processes. Heterogeneous catalysis, which involves distinct phases for catalysts and reactants, has emerged as a cornerstone for green energy generation and conversion technologies [24]. At the heart of these processes lies the fundamental relationship between a catalyst's atomic structure and the energy landscape it creates for chemical transformations. The precise arrangement of atoms at the catalyst surface directly dictates the energy barriers for reactant adsorption, surface diffusion, chemical bond rearrangement, and product desorption. Understanding and controlling this relationship represents the central challenge in rational catalyst design for overcoming kinetic limitations in energy-related applications.

Industrial catalyst development has traditionally relied on empirical methods such as impregnation strategies, where metal salt precursors are deposited on supports followed by pyrolysis. These approaches typically yield catalysts with broad size distributions, inhomogeneous surface structures, and poor interaction with supports, resulting in average catalytic performance that obscures fundamental structure-activity relationships [24]. The heterogeneity and complexity of conventional catalysts' atomic and chemical structures present significant challenges for elucidating catalytic mechanisms at the atomic scale. This review examines how advanced synthesis techniques, characterization methods, and computational approaches are enabling unprecedented control over catalyst architecture at the atomic level, thereby permitting direct modulation of energy landscapes in catalytic processes.

Atomic-Level Characterization of Catalytic Structures

Structural Complexity in Heterogeneous Catalysts

The surfaces of conventional heterogeneous catalysts present a complex array of coordination environments that significantly influence their catalytic properties. A typical metal nanoparticle contains various atoms with different edges, faces, and coordination environments, each exhibiting distinct reactivity [24]. This structural diversity is further complicated by the presence of defects including vacancies, kinks, atomic steps, stacking faults, and twin boundaries. These features create a heterogeneous energy landscape where different surface sites exhibit varying activation barriers for elementary reaction steps, making precise determination of active centers exceptionally challenging [24].

The presence of multiple active site types complicates mechanistic studies and hinders the rational optimization of catalytic performance. Without atomic-level structural control, catalysts inevitably contain a distribution of active sites, each with different catalytic properties. This structural ambiguity represents a fundamental limitation in conventional catalyst design and underscores the critical need for synthetic methods capable of producing well-defined atomic architectures.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Modern catalyst characterization has increasingly relied on in situ and operando spectroscopy techniques combined with theoretical calculations to probe active sites under realistic reaction conditions. These approaches have revealed that metal/oxide interface structures possess unique and complicated electronic states, interactions, and boundary structures arising from polarization, hybridization, and charge transfer [24]. Even minor modifications at these interfaces can significantly alter material properties and catalytic performance due to the interplay of multiple factors including composition, particle size, electronic state of interface elements, and microstructures [24].

The integration of computational modeling with experimental characterization has proven particularly valuable for understanding how atomic structure influences energy landscapes. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide insights into electronic structure changes during catalysis, as demonstrated in studies of O₂ adsorption on bimetallic surfaces where sp-band interactions proved crucial despite minimal d-band changes [25].

Atomic-Level Synthesis Techniques

Atomic Layer Deposition for Precision Catalyst Design

Atomic layer deposition (ALD) has emerged as a powerful technique for designing heterogeneous catalysts with atomic precision. As a self-limiting layer-by-layer chemical reaction between gaseous metal precursors and solid substrates, ALD enables precise control over deposited film thickness or nanoparticle size with exceptional conformity, reproducibility, and uniformity [24]. The technique has generated significant research interest, with 1,393 publications on ALD and catalysis in the past decade alone out of 1,794 total articles on the subject [24].

ALD facilitates the creation of uniform metal/oxide interfaces with isolated and size-controllable metal particles, alloys, and single atoms on various supports. This precision enables researchers to systematically investigate structure-activity relationships that were previously obscured by structural heterogeneity. The technique has proven particularly valuable for interface engineering through nano-alloying, heteroatom doping, and heterojunction formation, all of which significantly influence catalytic efficiency [24]. Core-shell structures with tailored coating thickness and catalyst loading can be fabricated to anchor catalyst nanoparticles and prevent agglomeration or migration during operation, addressing critical stability challenges in electrochemical applications [24].

Table 1: Atomic Layer Deposition Applications in Catalyst Design

| Application Domain | ALD Contribution | Impact on Catalytic Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Supported Nanoparticles | Size-controlled deposition with atomic precision | Enhanced activity and selectivity through precise surface structure control |

| Metal/Oxide Interfaces | Creation of uniform interface structures with controlled electronic properties | Optimized charge transfer and binding energy landscape |

| Core-Shell Structures | Tailored coating thickness to anchor catalyst nanoparticles | Improved stability against agglomeration, dissolution, and sintering |

| Single-Atom Catalysts | Site-selective deposition of isolated metal atoms | Maximum atom efficiency and unique coordination environments |

| Alloy Catalysts | Sequential precursor deposition with controlled stoichiometry | Fine-tuned electronic structure and surface composition |

Despite its significant advantages, ALD faces challenges including high cost, slow deposition rates, and limited materials deposition capabilities [24]. Scalability remains a particular concern for industrial catalyst production, though recent advances in energy-efficient ALD techniques and modular systems compatible with conventional fabrication methods show promise for addressing these limitations [24].

High-Throughput Computational-Experimental Screening

The integration of high-throughput computation with experimental validation has emerged as a powerful paradigm for accelerating catalyst discovery. A 2021 study demonstrated a screening protocol that evaluated 4,350 bimetallic alloy structures using DFT calculations to identify candidates with electronic density of states (DOS) patterns similar to palladium, a prototypical catalyst for hydrogen peroxide synthesis [25]. This approach leveraged electronic structure similarity as a descriptor for predicting catalytic properties, enabling efficient down-selection from thousands of candidates to eight promising alloys [25].

Experimental validation confirmed that four of these alloys exhibited catalytic properties comparable to palladium, with the Pd-free Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ catalyst achieving a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity [25]. This success demonstrates how electronic structure-based screening can efficiently identify catalyst materials with tailored energy landscapes for specific applications. The full DOS pattern serves as an effective descriptor because it contains comprehensive information about both d-states and sp-states, which was shown to be crucial for reactions like O₂ adsorption where sp-band interactions dominate [25].

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening Results for Bimetallic Catalysts

| Catalyst Composition | DOS Similarity to Pd(ΔDOS) | Catalytic Performance Relative to Pd | Cost-Normalized Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ | <2.0 | Comparable | 9.5-fold enhancement |

| Au₅₁Pd₄₉ | <2.0 | Comparable | Not specified |

| Pt₅₂Pd₄₈ | <2.0 | Comparable | Not specified |

| Pd₅₂Ni₄₈ | <2.0 | Comparable | Not specified |

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

High-Throughput Screening Protocol

The discovery of high-performance bimetallic catalysts requires a systematic approach combining computational and experimental methods. The following workflow outlines a proven protocol for identifying alloy catalysts with tailored energy landscapes:

Candidate Generation: Select binary systems from transition metals in periods IV, V, and VI. Consider 435 binary systems with 1:1 composition and 10 ordered phases for each combination (B1, B2, B3, B4, B11, B19, B27, B33, L10, L11), totaling 4,350 crystal structures [25].

Thermodynamic Screening: Calculate formation energy (ΔEf) for each phase using DFT. Filter systems with ΔEf < 0.1 eV to ensure thermodynamic stability and synthetic feasibility [25].

Electronic Structure Analysis: Compute density of states (DOS) patterns projected on close-packed surfaces for thermodynamically stable alloys. Quantify similarity to reference catalyst using the ΔDOS metric: ΔDOS₂₋₁ = {∫[DOS₂(E) - DOS₁(E)]²g(E;σ)dE}¹ᐟ² where g(E;σ) = (1/(σ√(2π)))e^(-(E-E_F)²/(2σ²)) with σ = 7 eV to emphasize states near Fermi energy [25].

Candidate Selection: Identify alloys with lowest ΔDOS values (e.g., <2.0) indicating electronic structure similarity to reference catalyst [25].

Experimental Synthesis and Validation: Prepare selected candidates and evaluate catalytic performance for target reaction. Compare activity, selectivity, and stability to reference materials.

Reactor Selection for Catalyst Testing

Proper reactor selection is essential for obtaining meaningful catalytic performance data that can scale to industrial applications. Chemical engineering principles provide guidance for selecting appropriate test reactors based on several criteria: high productivity and selectivity, high efficiency, high safety, high reliability, and low costs [26]. These criteria often lead to conflicting requirements, necessitating careful optimization for specific applications.

For catalyst testing, scaled-down reactor systems must faithfully represent the behavior of commercial-scale units. In some cases, such as riser reactors for fluid catalytic cracking, the "Dinky Toy" approach – creating geometrically similar reactors at different scales – is appropriate [26]. For structured reactors, scaled-down versions can effectively simulate commercial units as they maintain similar flow characteristics and temperature profiles [26]. The historical trend in catalyst testing has moved from individual reactors requiring full human attention to automated systems with increased parallelization, dramatically increasing research productivity [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Atomic-Level Catalyst Design

| Material/Reagent | Function in Catalyst Development | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Layer Deposition Precursors | Provide metal sources for controlled deposition of catalytic materials | Metalorganic compounds (e.g., trimethylaluminum), metal halides for oxide deposition |

| High-Surface-Area Supports | Anchor catalytic sites and provide tailored metal-support interactions | Alumina, silica, carbon nanotubes, graphene, zeolites |

| Bimetallic Alloy Precursors | Enable formation of alloy catalysts with tailored electronic properties | Metal salt mixtures for co-impregnation, sequential ALD precursors |

| Plasma-Enhanced ALD Systems | Facilitate low-temperature deposition and unique material structures | Plasma generators, radical sources for low-temperature processing |

| In Situ/Operando Characterization Cells | Enable real-time monitoring of catalytic structure under reaction conditions | XRD cells, FTIR cells, XAS cells with controlled atmosphere and temperature |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Allow parallel testing of multiple catalyst formulations | Multi-reactor arrays, automated product analysis systems |

The precise control of catalyst atomic structure represents a paradigm shift in heterogeneous catalysis, enabling direct modulation of energy landscapes for optimized catalytic performance. Techniques such as atomic layer deposition and high-throughput computational-experimental screening are providing unprecedented opportunities to design catalysts with tailored active sites, interface structures, and electronic properties. These advances are gradually overcoming the traditional limitations of heterogeneous catalysts, including structural heterogeneity, poor atom efficiency, and insufficient stability.

Future progress in catalyst design will require enhanced integration of synthesis, characterization, and computation to establish comprehensive structure-activity relationships. Scalability challenges for atomic-precision techniques must be addressed to bridge the gap between laboratory discoveries and industrial applications. The development of more sophisticated operando characterization methods will provide deeper insights into dynamic structural changes during catalysis, enabling more accurate modeling of energy landscapes. As these techniques mature, the rational design of catalysts with optimized atomic structures for specific energy conversion and storage applications will play an increasingly vital role in transitioning to a sustainable energy future.

Catalysts are pivotal in material synthesis and environmental remediation by regulating reaction rates without being consumed in the process. [27] With recent breakthroughs in nanoscience, catalyst design has evolved from bulk materials to nanoparticles and now to atomic-scale architectures. [28] This progression represents the pursuit of maximum atomic utilization efficiency and precise control over catalytic properties. Single-atom catalysts (SACs), first formally conceptualized in 2011, have revolutionized electrocatalytic processes by providing isolated active sites with exceptional efficiency. [27] [28] Building upon this foundation, diatomic catalysts (DACs) and triatomic catalysts (TACs) have emerged as advanced architectures that leverage synergistic interactions between multiple metal atoms. [27] These developments are particularly relevant within the context of energy barrier research in catalytic processes, as the arrangement of metal atoms at the atomic scale directly influences activation energies and reaction pathways.

The fundamental distinction among these architectures lies in the number of atoms at active sites and their cooperative mechanisms. While SACs maximize atomic utilization with isolated single atoms, they often struggle to regulate multi-step reactions effectively. [27] DACs enhance reaction processes through electronic coupling of dual atoms, though their configuration and electronic regulation remain somewhat limited. [29] TACs represent the next frontier, forming multi-active-site cooperativity with linear or triangular configurations that exhibit substantial electronic delocalization through metal bonds and carrier coordination. [27] This progression from single to multiple atoms in catalyst design reflects an ongoing effort to overcome limitations in activity, selectivity, and stability while providing more sophisticated control over energy barriers in critical reactions for clean energy technologies.

Fundamental Architectures and Properties

Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs)

Single-atom catalysts represent the ultimate limit of atom efficiency, featuring isolated metal atoms dispersed on appropriate support materials. These catalysts have demonstrated remarkable performance across various electrocatalytic reactions, including hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), oxygen evolution reaction (OER), oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), CO₂ reduction reaction (CO₂RR), and nitrogen reduction reaction (N₂RR). [30] The exceptional properties of SACs stem from their maximized atomic utilization, unsaturated coordination environments, quantum size effects, and strong metal-support interactions. [30] These characteristics collectively contribute to lowering activation energy barriers in catalytic processes.

Despite these advantages, SACs face significant challenges. The high surface free energy of isolated atoms often leads to migration and aggregation, compromising stability and durability. [27] [30] Additionally, the single active site in SACs presents intrinsic limitations for complex multi-step reactions that require simultaneous adsorption of multiple intermediates or orchestration of coupled reaction steps. [27] This constraint becomes particularly evident in processes such as CO₂ reduction and nitrogen reduction, where sophisticated coordination of multiple reaction intermediates is essential. Maintaining high reactivity and stability while achieving substantial metal loading remains a critical challenge for SAC development. [30]

Diatomic Catalysts (DACs)

Diatomic catalysts represent a significant advancement beyond SACs, featuring paired metal atoms that enable synergistic effects not possible with isolated single atoms. [29] These catalysts bridge the material gap between single-atom catalysts and nanoparticles, offering superior catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability for complex reactions. [31] The bimetallic synergy in DACs optimizes intermediate adsorption and lowers activation energy, thereby significantly enhancing catalytic performance, particularly in reactions requiring multi-site catalysis. [29] This architecture demonstrates special advantages in oxygen electrocatalysis, CO₂ reduction, and nitrogen reduction reactions.

A critical design parameter in DACs is the interatomic distance between dual atoms, which profoundly influences their electronic structure, coordination environment, and catalytic behavior. [31] Achieving precise spatial control at the sub-nanometer scale remains challenging but essential for optimizing performance. Recent research has explored various distance modulation strategies, including steric confinement, interlayer engineering, lattice distortion, and defect anchoring. [31] For instance, studies on TM₁TM₂N₈@BPN diatomic catalysts supported on nitrogen-doped biphenylene have demonstrated exceptional bifunctional performance for OER and ORR, with remarkably low overpotentials of 0.084/0.129 V and 0.113/0.178 V for Mn-Mn and Mn-Ni pairs, respectively. [29] These values significantly surpass noble-metal benchmarks and conventional SACs, highlighting the advantage of diatomic architectures.

Triatomic Catalysts (TACs)

Triatomic catalysts represent the cutting edge of atomic-scale catalyst design, building upon dual-atom catalysts with three metal atoms arranged in linear or triangular configurations. [27] These advanced architectures demonstrate exceptional catalytic activity toward complex reactions such as oxygen reduction reaction, with particular advantages in multi-electron processes including CO₂ reduction reaction and N₂ reduction reaction. [27] [32] The triatomic sites possess dynamic stability against aggregation and break limitations of single and dual-atom systems through enhanced multi-atom cooperativity and electronic delocalization. [27]

The fundamental advantage of TACs lies in their ability to simultaneously regulate adsorption energies of multiple intermediates through heteronuclear design and multi-atom cooperativity. [27] For example, research on Fe₂/Co-NHCS triple-atom catalysts featuring Fe₂N₅+CoN₄ structures has demonstrated how adjacent CoN₄ sites can optimize the spin state of Fe-Fe double atomic pairs from low to medium spin configuration. [32] This spin state modulation enables catalysts to bind more readily with oxygen reactants, dramatically improving ORR performance with a high half-wave potential of 0.92 V and enabling zinc-air batteries to function effectively even at -40°C. [32] Such sophisticated electronic control exemplifies the unique capabilities of triatomic systems in managing energy barriers for challenging reactions.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Atomic-Scale Catalyst Architectures

| Architecture | Active Sites | Key Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Isolated metal atoms | Maximum atom utilization; Unsaturated coordination; High activity | Difficult to regulate multi-step reactions; Aggregation tendency; Limited metal loading | HER, OER, ORR, CO₂RR [30] |

| Diatomic Catalysts (DACs) | Paired metal atoms | Synergistic effects; Enhanced active sites; Better intermediate adsorption | Stringent substrate requirements; Complex synthesis | OER/ORR bifunctional catalysis; CO₂RR; NRR [29] [31] |

| Triatomic Catalysts (TACs) | Three metal atoms (linear/triangular) | Multi-active-site cooperativity; Electronic delocalization; Anti-aggregation stability | Complex preparation; Precise synthesis challenges | CO₂RR; NRR; Low-temperature ZABs [27] [32] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Synthesis and Fabrication Approaches

The preparation of atomic-scale catalysts requires precise control over metal atom dispersion and coordination environments. For triatomic catalysts, key considerations include selecting appropriate support materials that significantly influence electronic structure modulation, interface effects, and active site regulation. [27] Support materials are broadly categorized into carbon-based materials (graphene, carbon nanotubes), metal oxides (including MOFs), and metallic carriers. [27] Carbon-based supports offer high specific surface area, superior electronic conductivity, and remarkable mechanical stability, though they may exhibit inadequate thermal stability in certain applications. [27] Metal oxide supports establish strong metal-support interactions that stabilize metal catalysts and enhance selectivity. [27]

Defect engineering plays a crucial role in creating effective anchoring sites for metal atoms. Carbon-based carriers possess a high density of defects that can be artificially introduced through methods such as in situ doping and post-modification. [27] These defects significantly increase active site density, regulate adsorption free energy, optimize reactant adsorption and activation processes, and enhance electron transfer efficiency between metal active centers and reactants. [27] For instance, researchers have successfully immobilized free Pt atoms on carbon nitride defects, transforming them into highly reactive species with significantly enhanced activity in semi-hydrogenation reactions. [27] Similar strategies apply to DACs, where nitrogen-doped biphenylene (BPN) substrates have demonstrated excellent stability and metallic properties with n-type Dirac cones, high electrical conductivity, and anisotropic electrical transport. [29]

Characterization and Computational Methods

Advanced characterization techniques are essential for understanding the structure-property relationships in atomic-scale catalysts. In situ X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) has proven particularly valuable for revealing dynamic catalysis mechanisms, such as the wave-like charge variation processes observed in Na-S battery systems with single-atom catalysts. [33] These techniques provide insights into electrocatalytic behavior and intermediate adsorption under operational conditions.

Computational approaches, particularly density functional theory (DFT) calculations, play a crucial role in catalyst design and optimization. First-principles calculations have been extensively employed to investigate the electronic structures and catalytic mechanisms of diatomic and triatomic catalysts. [29] For instance, DFT studies on TM₁TM₂N₈@BPN diatomic catalysts have revealed that exceptional OER/ORR performance originates from optimized intermediate adsorption enabled by Mn-Mn/Mn-Ni synergistic effects, enhanced charge redistribution, and precise d-band center modulation. [29] These computational insights provide essential guidance for experimental synthesis.

Machine learning force fields (MLFFs) represent a recent advancement in computational catalysis, offering accurate energy barriers for catalytic reaction pathways with significantly reduced computational cost compared to direct ab-initio simulations. [6] These methods employ active learning protocols that automatically sample configurations from molecular dynamics, geometry optimization, or nudged elastic band calculations, continuously refining the force field until desired accuracy is achieved. [6] The resulting models can accurately determine energy barriers within 0.05 eV of DFT values while enabling the discovery of alternative reaction pathways with substantially reduced activation energies. [6] This approach is particularly valuable for exploring complex reaction networks and finite temperature effects that were previously computationally prohibitive.

Table 2: Key Experimental and Computational Methods for Atomic-Scale Catalyst Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Notable Advances |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Methods | Defect engineering; Spatial confinement; Atomic layer deposition | High-density atomic site creation; Precise coordination control | N-doped carbon carriers; Biphenylene substrates; Multi-metal coordination [27] [29] |

| Characterization Techniques | In-situ XAFS; STEM; XPS | Dynamic mechanism studies; Local structure identification | Real-time tracking of charge transfer; Atomic-resolution imaging [32] [33] |