Machine Learning-Accelerated Genetic Algorithms (MLaGA): Revolutionizing Nanoparticle Discovery for Biomedical Applications

This article explores the transformative integration of Machine Learning (ML) with Genetic Algorithms (GA) to accelerate the discovery and optimization of nanoparticles for drug delivery and biomedical applications.

Machine Learning-Accelerated Genetic Algorithms (MLaGA): Revolutionizing Nanoparticle Discovery for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of Machine Learning (ML) with Genetic Algorithms (GA) to accelerate the discovery and optimization of nanoparticles for drug delivery and biomedical applications. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of MLaGA foundations, from core principles to advanced methodologies. The content details practical applications in optimizing materials like PLGA and gold nanoparticles, addresses key challenges in troubleshooting and optimizing these computational workflows, and offers a critical validation against traditional methods. By synthesizing recent research and case studies, this article serves as a strategic guide for leveraging MLaGA to navigate vast combinatorial design spaces, significantly reduce development timelines, and usher in a new era of data-driven nanomedicine.

The Foundation of MLaGA: Core Principles and the Drive for Efficiency in Nanomedicine

In the pursuit of advanced therapeutics, the discovery and optimization of nanoparticles for drug delivery present a complex, multi-parameter challenge. Traditional experimental approaches are often slow, costly, and struggle to navigate the vast design space of material compositions, sizes, and surface properties. Machine Learning-accelerated Genetic Algorithms (MLaGAs) represent a powerful synergy of evolutionary computation and machine learning, engineered to overcome these limitations. This paradigm integrates the global search prowess of Genetic Algorithms (GAs) with the predictive modeling and pattern recognition capabilities of ML, creating a robust framework for intelligent design and optimization. Within nanoparticle discovery research, this hybrid approach is transforming the pace at which researchers can formulate stable, effective, and safe nanocarriers, de-risking the development pipeline and unlocking novel therapeutic possibilities [1] [2].

Theoretical Foundation

Core Components of the MLaGA Paradigm

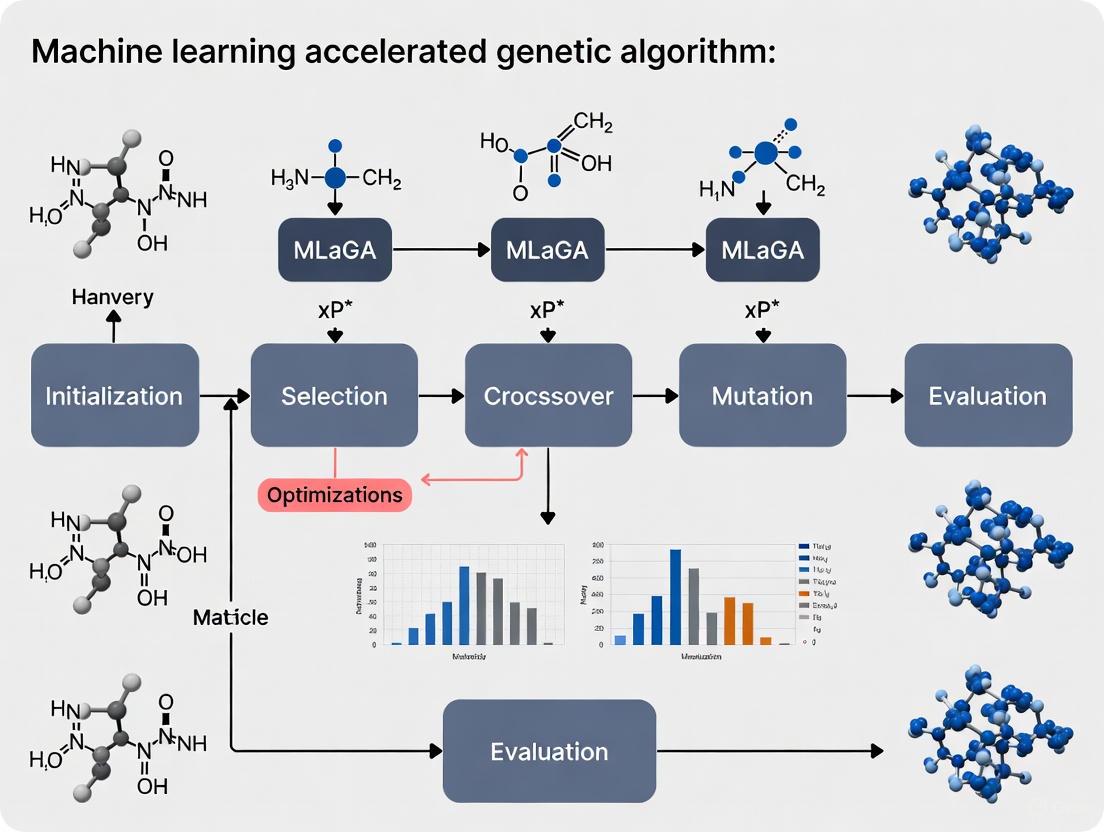

A Machine Learning-accelerated Genetic Algorithm is an advanced optimization engine that uses machine learning models to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of a traditional genetic algorithm. The core components of this hybrid paradigm are:

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): A population-based metaheuristic inspired by natural selection. It operates on a population of candidate solutions (e.g., different nanoparticle formulations), applying selection, crossover (recombination), and mutation operators to evolve increasingly fit solutions over generations [3]. GAs excel at global exploration of complex search spaces where gradient information is unavailable or the problem is a "black box."

- Machine Learning (ML) Model: A predictive algorithm, such as XGBoost or Support Vector Machines (SVM), that is integrated into the GA workflow [4] [3]. Its primary role is to act as a surrogate model, approximating the fitness function—which is often a costly and time-consuming wet-lab experiment. By rapidly predicting the performance of candidate formulations, the ML model drastically reduces the number of physical experiments required.

The Acceleration Mechanism

The "acceleration" in MLaGA is achieved by leveraging the ML model as a computationally cheap proxy for evaluation. Instead of synthesizing and testing every candidate nanoparticle in a lab, a large proportion of the GA population is evaluated using the ML model's prediction. This allows the algorithm to explore a much wider design space and converge to high-performing solutions in a fraction of the time. The ML model can be trained on initial experimental data and updated iteratively as new data is generated, progressively improving its predictive accuracy and guiding the GA more effectively [2] [3].

Performance and Quantitative Benchmarks

The superiority of hybrid approaches like MLaGA is demonstrated by their performance against traditional methods in both data generation and nanoparticle optimization tasks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Data Generation Techniques for Imbalanced Datasets

| Method | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | ROC-AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-based Synthesis [3] | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| XGBoost [4] | >96% | High | High | High | - |

| SMOTE [3] | <90% | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Lower |

| ADASYN [3] | <90% | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Lower |

| SVM / k-NN [4] | <90% | Lower | Lower | Lower | - |

Table 2: Efficacy of an AI-Guided Platform (TuNa-AI) in Nanoparticle Optimization

| Metric | Standard Approaches | TuNa-AI Platform [2] | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful Nanoparticle Formation | Baseline | +42.9% | 42.9% increase |

| Excipient Usage Reduction | Baseline | Reduced a carcinogenic excipient by 75% | Safer formulation |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Baseline | Improved solubility and cell growth inhibition | Enhanced |

Application Notes: MLaGA for Nanoparticle Discovery

Primary Application Areas

In nanoparticle research, MLaGAs are primarily deployed for two critical tasks:

- Optimizing Formulation Recipes: The platform can simultaneously optimize both the identity of ingredients (e.g., polymers, lipids, drugs) and their quantitative ratios, a capability beyond many existing AI tools. This was validated in the development of a venetoclax-loaded nanoparticle for leukemia, which showed improved solubility and efficacy [2].

- Addressing Data Imbalance: In discovery screens, high-performing formulations are often rare, creating an imbalanced dataset. GAs can be used to generate high-quality synthetic data representing the minority class (high-performing nanoparticles), which then trains a more robust ML model for subsequent screening rounds [3].

Experimental Protocol: MLaGA-Driven Nanoparticle Optimization

The following workflow, implemented using an automated robotic platform and AI, outlines the process for discovering and optimizing a therapeutic nanoparticle formulation [2].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define Design Space: Identify the variables to be optimized, including the types of therapeutic molecules, excipients (e.g., lipids, polymers), and their allowable concentration ranges [2].

- Generate Initial Library & High-Throughput Synthesis: Use an automated liquid handling robot to systematically prepare a library of distinct formulations (e.g., 1275 distinct formulations) by combining ingredients across the defined design space [2].

- Performance Assays: Characterize each formulation for critical performance attributes. Key assays include:

- Encapsulation Efficiency: Measure the percentage of the active drug successfully incorporated into the nanoparticle.

- Stability & Solubility: Assess physical stability in solution and dissolution profile.

- In Vitro Efficacy: Test the formulation's ability to inhibit target cell growth (e.g., leukemia cells) [2].

- Curate Training Dataset: Compile the data from steps 2 and 3 into a structured dataset where the input variables are the formulation recipes and the output/target variables are the performance metrics.

- Train Surrogate ML Model: Train a machine learning model (e.g., a hybrid kernel machine like TuNa-AI or a tree-based model like XGBoost) on the curated dataset. This model will learn to predict formulation performance based on the recipe [2].

- Run Genetic Algorithm:

- Initialization: Create an initial population of nanoparticle formulations.

- Evaluation: Use the trained surrogate ML model to rapidly predict the fitness (e.g., encapsulation efficiency, stability) of each candidate, instead of running a wet-lab experiment.

- Selection, Crossover, Mutation: Apply GA operators to create a new generation of candidate formulations [3].

- Iteration: Repeat the evaluation and evolution cycle for multiple generations.

- Select Promising Candidates: After the GA converges, select the top-performing candidate formulations from the final population.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize and physically test the top candidates in the lab using the assays from Step 3 to confirm the ML model's predictions.

- Update Dataset & Model: Incorporate the new experimental results into the training dataset and retrain the ML model to improve its accuracy for subsequent optimization cycles.

- Deliver Optimized Formulation: The candidate that meets all pre-defined efficacy and safety criteria proceeds to further development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MLaGA-Driven Nanoparticle Discovery

| Category / Item | Function / Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Molecules | The active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) to be delivered. | Venetoclax (for leukemia) [2]. |

| Excipients (Lipids, Polymers) | Inactive substances that form the nanoparticle structure, control drug release, and enhance stability. | PLGA, chitosan, lipids; optimized for safety and biodistribution [2] [5]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | A robotic system for high-throughput, precise, and reproducible preparation of nanoparticle formulation libraries. | Systematic creation of 1275+ distinct formulations for initial dataset generation [2]. |

| AI/ML Software Stack | Software and algorithms for building surrogate models and running genetic algorithms. | EvoJAX, PyGAD for GAs; XGBoost, SVM for classification and regression [1] [4] [3]. |

| Characterization Assays | Experiments to measure nanoparticle properties and performance. | Encapsulation efficiency, stability/solubility tests, in vitro cell-based efficacy assays [2]. |

Advanced Protocol: Synthetic Data Generation for Imbalanced Formulation Data

A significant challenge in applying ML to nanoparticle discovery is the "imbalanced dataset" problem, where successful formulations are rare. This protocol uses a GA to generate synthetic data representing high-performing nanoparticles, which can then be used to augment training data for a secondary ML model.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Initial Imbalanced Dataset: Begin with a dataset of formulated nanoparticles where the minority class represents the successful/high-performing formulations.

- Fit ML Model to Minority Class: Train a machine learning model, such as a Support Vector Machine (SVM) or Logistic Regression, solely on the feature vectors of the minority class. This model learns the underlying distribution and patterns of the successful formulations [3].

- Derive Fitness Function: Use the trained ML model to create the fitness function for the GA. A candidate solution's (a synthetic data point's) fitness can be its proximity to the decision boundary of the SVM or its probability as assigned by the logistic regression model. The goal is to maximize this fitness, generating data that is convincingly part of the minority class [3].

- Initialize GA Population: Create an initial population of random candidate solutions (synthetic data vectors).

- Evaluate Fitness: Calculate the fitness of each candidate using the ML-derived fitness function.

- Apply GA Operators: Use selection, crossover, and mutation to create a new generation of candidates. Elitist GA variants, which preserve the best-performing candidates from one generation to the next, are often particularly effective [3].

- Iterate and Check Convergence: Repeat steps 5 and 6 until the population converges or a performance plateau is reached.

- Output and Augment: The final GA population represents a set of high-quality synthetic data for the minority class. This data is then combined with the original imbalanced dataset to create a balanced dataset, which is used to train a more robust and accurate final predictive model for nanoparticle screening.

Machine Learning-accelerated Genetic Algorithms represent a paradigm shift in computational design and optimization for nanoparticle discovery. By fusing the global search power of evolutionary algorithms with the predictive precision of machine learning, MLaGAs create a highly efficient, iterative discovery loop. This approach directly addresses two of the most significant bottlenecks in the field: the astronomical size of the possible formulation space and the scarcity of high-performance training data. As a result, MLaGAs empower researchers to extract latent value from complex biological and chemical constraints, de-risking the development pipeline and accelerating the creation of next-generation nanotherapeutics. The continued development and application of this hybrid paradigm promise to significantly shorten the timeline from therapeutic concept to viable, optimized nanoparticle drug product.

The Scale of the Combinatorial Problem

The design of nanoparticles, particularly for advanced applications like drug delivery, is governed by a vast number of interdependent parameters. These include, but are not limited to, core composition, size, shape, surface chemistry, and functionalization with targeting ligands. The number of possible combinations arising from these parameters creates a search space so large that it becomes practically impossible to explore exhaustively using traditional experimental methods.

For example, in the development of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)—essential carriers for genetic medicines—optimization is plagued by nearly infinite design variables. Performance relies on a complex series of tasks:

- Encapsulation of nucleic acids

- Stable particle formation

- Stable circulation in the bloodstream

- Favorable interaction and endosomal uptake in target cells

- Endosomal escape to the cytoplasm [6].

Each of these tasks is influenced by subtle, interdependent changes to parameters such as lipid structure, lipid composition, cargo-to-vehicle material ratio, particle fabrication process, and surface surfactants [6]. This multi-scale and multi-parameter complexity makes leveraging computational power essential for rational design and optimization [6].

To put this into perspective, consider the challenge of optimizing a simple binary nanoalloy, such as a PtxAu147-x nanoparticle. The number of possible atomic arrangements, or homotops, for each composition is given by the combinatorial formula: $$HN = \frac{{N!}}{{N{\mathrm{A}}!N_{\mathrm{B}}!}}$$ For all 146 compositions, this results in a total of 1.78 × 10^44 homotops [7]. The number of possibilities rises combinatorially toward the 1:1 composition, making a brute-force search for the most stable structure entirely infeasible [7].

The Inefficiency of Traditional Optimization Methods

Traditional nanoparticle discovery often relies on a trial-and-error approach in the laboratory. This method is time-consuming, costly, and challenging, as it depends on finding the optimum formulation under controlled experimental conditions with high equipment supplies and practical experience [8]. These "brute-force" methods are inefficient because they require a large number of experiments or calculations and are often limited by the researcher's intuition and prior knowledge.

The impracticality is evident when considering computational searches. A traditional Genetic Algorithm (GA) used to locate the most stable structures (the convex hull) for the 147-atom Pt-Au system required approximately 16,000 candidate minimizations [7]. While this is significantly lower than the total number of homotops, it is still prohibitively high when using computationally expensive energy calculators, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), which provides accurate results but is resource-intensive [7].

The following table quantifies the inefficiency of a traditional GA for a specific nanoalloy search and contrasts it with a machine-learning accelerated approach.

Table 1: Comparison of Search Methods for Locating the Convex Hull of PtxAu147-x Nanoparticles

| Search Method | Number of Energy Calculations Required | Computational Cost | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brute-Force | 1.78 x 10^44 (Total homotops) [7] | Theoretically impossible | Evaluates all possible combinations |

| Traditional Genetic Algorithm (GA) | ~16,000 [7] | High, often prohibitive for accurate methods like DFT | Metaheuristic, inspired by Darwinian evolution |

| Machine Learning Accelerated GA (MLaGA) | ~280 - 1,200 [7] | 50-fold reduction compared to traditional GA [7] [9] | Uses a machine learning model as a surrogate fitness evaluator |

This table demonstrates that even advanced metaheuristic algorithms like GAs can be inefficient, requiring thousands of expensive evaluations. This inefficiency forms the core of the combinatorial challenge, making the discovery of optimal nanoparticle designs slow and resource-intensive.

Experimental Protocol: Traditional "Brute-Force" Screening for Nanoparticle Properties

This protocol outlines a standardized, iterative process for experimentally determining the optimal formulation parameters for a polymer-based nanoparticle, such as Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), to achieve a target size and drug encapsulation efficiency.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for Traditional Nanoparticle Screening

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| PLGA (50:50) | A biodegradable and biocompatible copolymer used as the primary matrix material for nanoparticle formation [8]. |

| Solvent (e.g., Acetone, DCM) | An organic solvent used to dissolve the polymer. |

| Aqueous Surfactant Solution (e.g., PVA) | A stabilizer that prevents nanoparticle aggregation during formation. |

| Antiviral Drug Candidate | The active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) to be encapsulated. |

| Dialysis Tubing or Purification Columns | For purifying formed nanoparticles from free drugs and solvents. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | For measuring nanoparticle hydrodynamic size and Polydispersity Index (PDI) [8]. |

| Ultracentrifuge | For separating nanoparticles from the suspension for further analysis. |

| HPLC or UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | For quantifying drug loading and encapsulation efficiency [8]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Formulation Variation: Systematically vary one or two critical formulation parameters at a time while holding others constant. Key parameters to vary include:

- Polymer concentration

- Drug-to-polymer ratio

- Aqueous-to-organic phase volume ratio

- Surfactant type and concentration

- Homogenization speed and time

Nanoparticle Synthesis: For each unique formulation, synthesize nanoparticles using a standard method such as single or double emulsion-solvent evaporation.

Purification: Purify the nanoparticle suspension via dialysis or centrifugation to remove the organic solvent and unencapsulated drug.

Characterization and Analysis: For each batch, characterize the nanoparticles by:

- Size and PDI: Measure using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [8].

- Drug Loading (DL) and Encapsulation Efficiency (EE): Determine by lysing a known amount of purified nanoparticles and quantifying the drug content using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC). Calculate using [8]:

Drug Loading (%) = (Weight of drug in nanoparticles / Weight of total nanoparticle) x 100Encapsulation Efficiency (%) = (Weight of drug in nanoparticle / Initial weight of blank drug) x 100

Data Compilation and Iteration: Compile the data from all formulations. Analyze results to identify trends. Based on the outcomes, design a new set of formulations for the next round of iterative testing, attempting to converge on the optimal parameters.

Limitations in Practice

This one- or two-parameter-at-a-time approach is inherently inefficient. It fails to capture complex, non-linear interactions between three or more parameters. For instance, as shown in Table 1, the relationship between nanoparticle size, PDI, and encapsulation efficiency for PLGA 50:50 is highly non-linear, with efficiency fluctuating significantly across different sizes and PDIs [8]. Discovering these complex relationships through trial-and-error is a major contributor to the combinatorial challenge, consuming significant time and resources.

A Paradigm Shift: Machine Learning Accelerated Genetic Algorithms (MLaGA)

The core innovation that addresses the combinatorial challenge is the integration of a machine learning model directly into the optimization workflow. This creates a Machine Learning Accelerated Genetic Algorithm (MLaGA), which combines the robust, global search capabilities of a GA with the rapid predictive power of ML [7].

How MLaGA Works

The MLaGA operates with two tiers of energy evaluation: one by the ML model (a surrogate) providing a predicted fitness, and the other by the high-fidelity energy calculator (e.g., DFT) providing the actual fitness [7]. A key implementation uses a nested GA to search the surrogate model, acting as a high-throughput screening function that runs within the "master" GA. This allows the algorithm to make large steps on the potential energy surface without performing expensive energy evaluations [7].

Diagram 1: MLaGA workflow reduces costly calculations. The algorithm cycles between rapid ML-guided search and high-fidelity validation, filtering the vast search space before committing to expensive computations.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an MLaGA for Nanoparticle Discovery

This protocol details the steps for setting up an MLaGA search, using the example of finding the lowest-energy chemical ordering in a nanoalloy.

Materials and Computational Tools

- Genetic Algorithm Framework: Software capable of performing crossover, mutation, and selection operations on a population of candidate structures [7].

- Machine Learning Model: A probabilistic model, such as a Gaussian Process (GP), to act as the surrogate fitness evaluator [7] [8]. The GP defines a prior over functions and, after observing data, provides a posterior prediction for new input candidates, including uncertainty estimates [8].

- High-Fidelity Energy Calculator: A method like Density Functional Theory (DFT) for accurate but expensive energy evaluations [7].

- Descriptor Generation: A method to convert the atomic structure of a nanoparticle into a numerical vector (descriptor) that the ML model can process.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initialization:

- Generate an initial population of candidate nanoparticle structures with random chemical ordering.

- Perform a high-fidelity energy calculation (e.g., DFT) on this small initial set to create a seed dataset.

ML Model Training:

- Train the Gaussian Process (or other ML) model on the current dataset of structures and their calculated energies.

Nested Surrogate Search:

- Launch a nested genetic algorithm where the fitness of candidates is evaluated using the trained ML model, not the expensive calculator.

- Run the nested GA for multiple generations, rapidly exploring the search space based on predicted fitness.

High-Fidelity Validation:

- Select the final population from the nested GA and evaluate their energies using the high-fidelity DFT calculator.

Data Augmentation and Iteration:

- Add the new candidates and their validated energies to the training dataset.

- Retrain the ML model on the augmented dataset.

- Repeat steps 3-5 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., the ML search can no longer find new candidates predicted to be significantly better).

Quantifiable Efficacy of MLaGA

The MLaGA methodology provides a dramatic reduction in computational cost. As shown in Table 1, it can locate the full convex hull of minima using only ~280-1,200 energy calculations, a reduction of over 50-fold compared to the traditional GA [7] [9]. This makes searching through the space of all homotops and compositions of a binary alloy particle feasible using accurate but expensive methods like DFT [7].

This approach is not limited to metallic nanoalloys. The Gaussian Process model has also been successfully applied to predict the properties of polymer nanoparticles like PLGA, generating graphs that predict drug loading and encapsulation efficiency based on nanoparticle size and PDI, thereby eliminating the need for extensive trial-and-error experimentation [8].

The discovery and optimization of novel materials, particularly nanoparticles for drug delivery, represent a critical frontier in advancing human health. However, the computational cost of accurately evaluating candidate materials often renders traditional search methods impractical. Within this challenge lies a powerful synergy: Machine Learning (ML) surrogate models are revolutionizing the efficiency of Genetic Algorithms (GAs), creating a feedback loop that dramatically accelerates computational discovery. This paradigm, known as the Machine Learning accelerated Genetic Algorithm (MLaGA), transforms the discovery workflow. By replacing expensive physics-based energy calculations with a fast-learned model during the GA's search process, the MLaGA framework achieves orders-of-magnitude reduction in computational cost, making previously infeasible searches through vast material spaces not only possible but efficient [7]. This Application Note details the quantitative benchmarks, core protocols, and essential tools for deploying MLaGA in nanoparticle discovery research.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The integration of ML surrogates within a GA framework leads to dramatic improvements in computational efficiency, as quantified by benchmark studies on nanoparticle optimization.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional GA vs. MLaGA for Nanoparticle Discovery

| Algorithm Type | Number of Energy Calculations | Reduction Factor | Key Features | Reported Search Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional GA | ~16,000 | 1x (Baseline) | Direct energy evaluation for every candidate; robust but slow [7]. | Searching for stable PtxAu147-x nanoalloys across all compositions [7]. |

| MLaGA (Generational) | ~1,200 | ~13x | Uses an on-the-fly trained ML model as a surrogate for a full generation of candidates [7]. | Same as above, using a Gaussian Process model [7]. |

| MLaGA (Pool-based) | ~310 | ~50x | A new ML model is trained after each new energy calculation, maximizing information gain [7]. | Same as above, with serial evaluation [7]. |

| MLaGA (Uncertainty-Aware) | ~280 | ~57x | Incorporates prediction uncertainty into the selection criteria, guiding exploration [7]. | Same as above, using the cumulative distribution function for fitness [7]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for implementing an MLaGA to discover optimized nanoparticle alloys, as validated in recent literature.

Protocol: MLaGA for Nanoalloy Catalyst Discovery

Application: Identification of stable, compositionally variant Pt-Au nanoparticle alloys for catalytic applications. Primary Objective: To locate the convex hull of stable minima for a 147-atom Mackay icosahedral template structure across all PtxAu147−x (x ∈ [1, 146]) compositions with a minimal number of Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [7].

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Initial Dataset: A small, initial population of nanoparticle candidates with known compositions and atomic arrangements (genotypes) and their associated fitness (e.g., energy calculated via DFT or a cheaper potential like EMT).

- Fitness Evaluator: A high-fidelity, computationally expensive energy calculator (e.g., DFT) used sparingly.

- ML Framework: A regression model capable of learning from sequential data (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression, Neural Networks).

- GA Engine: A custom or library-based GA capable of supporting nested or pool-based populations.

Procedure:

Initialization:

- a. Define the search space: a 147-atom binary alloy with a fixed icosahedral geometry but variable chemical ordering and composition [7].

- b. Generate an initial population of candidate nanoparticles with random chemical ordering.

- c. Evaluate the fitness (excess energy) of each candidate in the initial population using the high-fidelity DFT calculator.

ML Surrogate Model Training:

- a. Train an initial ML surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process) on the current dataset of nanoparticle genotypes and their corresponding DFT-validated energies [7].

- b. The model learns the complex mapping between the atomic configuration (feature space) and the resulting energy (fitness).

Nested Surrogate GA Search:

- a. Within the main ("master") GA, initiate a nested GA.

- b. The nested GA uses the trained ML surrogate as its fitness function, which is computationally cheap to evaluate.

- c. Run the nested GA for multiple generations. In this phase, candidate offspring are generated via crossover and mutation, and their fitness is predicted by the ML model without performing any new DFT calculations [7].

- d. This step acts as a high-throughput screening, exploring the potential energy surface broadly and cheaply.

Candidate Selection and Validation:

- a. After the nested GA concludes, select the final population of unrelaxed candidates predicted by the surrogate to be the most fit.

- b. Pass these top candidates to the master GA.

- c. Evaluate these candidates using the high-fidelity DFT calculator to obtain their true fitness.

- d. Add these new genotype-true fitness pairs to the growing dataset.

Model Retraining and Iteration:

- a. Retrain the ML surrogate model on the updated, enlarged dataset.

- b. The model's accuracy improves as it learns from more DFT-validated data.

- c. Repeat steps 3-5 until a convergence criterion is met. Convergence is typically signaled when the ML surrogate can no longer find new candidates predicted to be significantly better than the existing best, indicating the search has stabilized [7].

Advanced Protocol: Uncertainty-Aware Pool-Based MLaGA

For maximum efficiency in serial computation, the following variant can be implemented.

Modifications to Base Protocol:

- Population Model: Switch from a generational population to a pool-based population.

- Sequential Training: Train a new ML surrogate model after every single new DFT calculation.

- Uncertainty Exploitation: Use the ML model's predictive uncertainty (e.g., from a Gaussian Process) in the fitness function. A common strategy is to maximize the Expected Improvement (EI) or use the Cumulative Distribution Function of the prediction, which balances exploration (probing uncertain regions) with exploitation (refining known good regions) [7]. This approach can reduce the required energy calculations to approximately 280, a 57-fold improvement over the traditional GA [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Experimental Tools for MLaGA-driven Nanoparticle Research

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Function in MLaGA Workflow | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Calculator | Provides high-fidelity, quantum-mechanical energy and property evaluation for training the ML surrogate and validating final candidates [7]. | Gold-standard for accurate nanoalloy stability and catalytic property prediction [7]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regression | Machine Learning Model | Serves as the surrogate model; provides fast fitness predictions and, crucially, quantifies prediction uncertainty [7]. | Ideal for data-efficient learning in early stages of MLaGA search [7]. |

| Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) | Nanoparticle Polymer | A biodegradable and biocompatible polymer used to form nanoparticle drug delivery carriers [10] [11]. | A key material for formulating nanoparticles designed to deliver small-molecule drugs across biological barriers [11]. |

| Liposomes | Nanoparticle Lipid Vesicle | Spherical vesicles with aqueous cores, used for encapsulating and delivering therapeutic drugs or genetic materials [10] [12]. | Basis for FDA-approved formulations (e.g., Doxil) and modern mRNA vaccine delivery (LNPs) [12]. |

| Mass Photometry | Analytical Instrument | A single-particle characterization technique that measures the molecular mass of individual nanoparticles, revealing heterogeneity in drug loading or surface coating [12]. | Critical quality control for ensuring batch-to-batch consistency of targeted nanoparticle formulations [12]. |

The integration of machine learning surrogate models with genetic algorithms represents a transformative advancement in computational materials discovery. The MLaGA framework, as detailed in these protocols and benchmarks, enables researchers to navigate the immense complexity of nanoparticle design spaces with unprecedented efficiency, reducing the number of required expensive energy evaluations by over 50-fold [7]. This synergy between robust evolutionary search and rapid machine learning prediction creates a powerful, adaptive feedback loop. For researchers in drug development and nanomedicine, adopting the MLaGA approach and the associated toolkit—from uncertainty-aware ML models to single-particle characterization techniques—provides a tangible path to accelerate the rational design of next-generation nanoparticles, ultimately shortening the timeline from conceptual design to clinical application.

The discovery of novel nanomaterials, such as nanoalloy catalysts, is often impeded by the immense computational cost associated with exploring their vast structural and compositional landscape. Genetic algorithms (GAs) are robust metaheuristics for this global optimization challenge, but their requirement for thousands of energy evaluations using quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) renders comprehensive searches impractical [7]. This application note details a proof-of-concept case study, framed within a broader thesis on Machine Learning Accelerated Genetic Algorithms (MLaGA), which successfully demonstrated a 50-fold reduction in the number of required energy calculations. By integrating an on-the-fly trained machine learning model as a surrogate for the potential energy surface, the MLaGA methodology makes exhaustive nanomaterial discovery searches feasible, significantly accelerating research and development timelines [7].

Key Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the quantitative results from benchmarking the MLaGA approach against a traditional genetic algorithm for a specific computational challenge: identifying the convex hull of stable minima for all compositions of a 147-atom PtxAu147−x icosahedral nanoparticle. The total number of possible atomic arrangements (homotops) for this system is approximately 1.78 × 10^44, illustrating the scale of the search space [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Efficiency Between Traditional GA and MLaGA Variants

| Algorithm / Method | Approximate Number of Energy Calculations | Computational Reduction (Compared to Traditional GA) |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional "Brute Force" GA | ~16,000 | 1x (Baseline) |

| MLaGA (Generational Population) | ~1,200 | ~13-fold |

| MLaGA with Tournament Acceptance | <600 | >26-fold |

| MLaGA (Pool-based with Uncertainty) | ~280 | >57-fold |

The data shows a clear hierarchy of efficiency, with the most sophisticated MLaGA implementation, which uses a pool-based population and leverages the prediction uncertainty of the machine learning model, achieving a reduction of more than 57-fold, surpassing the 50-fold target [7].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

The Machine Learning Accelerated Genetic Algorithm (MLaGA) Workflow

The core innovation of the MLaGA is its two-tiered evaluation system, which combines the robust search capabilities of a GA with the rapid screening power of a machine learning model. The general workflow is illustrated below.

Diagram 1: MLaGA workflow integrating machine learning surrogate model for accelerated discovery.

Protocol 1: Traditional GA Baseline [7]

- Initialization: Generate a population of random candidate nanoparticle structures.

- Fitness Evaluation: Relax each candidate structure and compute its energy using a quantum mechanical calculator (e.g., DFT). This is the most computationally expensive step.

- Selection: Select parent structures based on their fitness (lower energy is better).

- Genetic Operations: Create a new generation of candidates by applying crossover (combining parts of two parents) and mutation (random perturbations) operators.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 for many generations until the population converges on the lowest-energy (global minimum) structure.

- Output: The algorithm requires ~16,000 energy calculations to map the full convex hull for the benchmark system.

Protocol 2: MLaGA with Generational Population [7]

- Initialization & Initial DFT: Initialize a population and evaluate a small set of candidates with DFT to create an initial training set.

- ML Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model on the collected DFT data. This model learns to predict the energy of a structure based on its features.

- Nested Surrogate GA: A "nested" GA runs for multiple generations using the ML model as the fitness evaluator. This allows for rapid exploration of the potential energy surface without DFT calculations.

- Injection to Master GA: The best candidates from the nested GA are passed to the "master" GA.

- DFT Validation & Model Update: These candidates are evaluated with DFT for validation, and the new data is used to retrain and improve the ML model.

- Convergence: The process repeats until the ML model can no longer find new candidates predicted to be better than the existing ones. This approach reduces the required DFT calculations to ~1,200.

Protocol 3: Advanced MLaGA with Pool-based Active Learning [7] [13]

- Serial Execution: The GA progresses one candidate at a time in a serial, pool-based manner.

- Per-Candidate Model Update: The ML model is updated after every single DFT calculation, making it highly adaptive.

- Uncertainty Quantification: The GP model provides an uncertainty estimate (variance) for its predictions alongside the predicted energy (mean).

- Informed Selection: The next candidate for DFT evaluation is chosen based on a function that balances predicted energy (exploitation) and prediction uncertainty (exploration). A common method is to use the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) or the cumulative distribution function.

- Output: This most efficient protocol locates the convex hull in approximately 280-310 DFT calculations.

The Active Learning Loop for On-the-Fly Training

A critical component of the advanced MLaGA is the active learning loop, which ensures the machine learning model is trained on the most informative data points. This workflow is detailed below.

Diagram 2: Active learning loop for on-the-fly training of machine learning potential.

Protocol 4: On-the-Fly Active Learning for Geometry Relaxation [13]

This protocol is used within tools like Cluster-MLP to accelerate the individual geometry relaxation steps in the GA.

- Initial DFT Query: For a new candidate cluster geometry, a single-point DFT calculation is performed to obtain initial energy and forces.

- ML Potential Initialization: This data is used to initialize a machine learning potential (e.g., FLARE++).

- ML-Guided Relaxation: The atomic configuration is updated using an optimizer (e.g., BFGS) driven by the forces predicted by the ML potential.

- Uncertainty Monitoring: The ML potential provides the mean force prediction and the associated uncertainty for each atom.

- Decision Point:

- If the maximum uncertainty of the force prediction is above a set threshold, a new DFT single-point calculation is triggered at the current geometry. This new data is used to retrain the ML potential, improving its accuracy in that region of the potential energy surface.

- If the uncertainty is low and the relaxation is converged (based on ML-predicted forces), the final structure is accepted.

- Output: The fully relaxed structure, verified by DFT at key points, is added to the GA population. This method drastically reduces the number of DFT steps required for each relaxation trajectory.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

This section outlines the key software, algorithms, and computational methods that form the essential "toolkit" for implementing an MLaGA for nanomaterial discovery.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MLaGA Implementation

| Tool / Solution | Type | Function in MLaGA Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Metaheuristic Algorithm | Core global search engine for exploring nanocluster configurations via selection, crossover, and mutation [7] [13]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Quantum Mechanical Calculator | Provides accurate, reference-quality energy and forces for training the ML model and validating key candidates; the computational bottleneck [7] [13]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regression | Machine Learning Model | Serves as the surrogate energy predictor; chosen for its ability to provide uncertainty estimates alongside predictions [7] [14]. |

| FLARE++ ML Potential | Machine Learning Potential | An interatomic potential used in active learning frameworks for on-the-fly force prediction and uncertainty quantification during geometry relaxation [13]. |

| Birmingham Parallel GA (BPGA) | Genetic Algorithm Code | A specific GA implementation offering diverse mutation operations, modified and integrated into frameworks like DEAP for cluster searches [13]. |

| DEAP (Distributed Evolutionary Algorithms in Python) | Computational Framework | Provides a flexible Python toolkit for rapid prototyping and implementation of evolutionary algorithms, including GAs [13]. |

| ASE (Atomistic Simulation Environment) | Python Library | Interfaces with electronic structure codes and force fields, simplifying the setup and analysis of atomistic simulations within the GA workflow [13]. |

| Active Learning (AL) | Machine Learning Strategy | Manages on-the-fly training of the ML model by strategically querying DFT calculations only when necessary, maximizing data efficiency [13]. |

This proof-of-concept case study establishes the MLaGA framework as a transformative methodology for computational materials discovery. By achieving a 50-fold reduction in the number of required DFT calculations—from ~16,000 to ~280—the approach overcomes a critical bottleneck in the unbiased search for stable nanoclusters and nanoalloys [7]. The detailed protocols for generational and pool-based MLaGA, complemented by active learning for geometry relaxation, provide a clear roadmap for researchers. Integrating robust genetic algorithms with efficient, uncertainty-aware machine learning models renders previously intractable searches feasible, paving the way for the accelerated design of next-generation nanomaterials, such as high-performance nanoalloy catalysts [7] [13].

The discovery and optimization of novel nanoparticles represent a significant challenge in materials science and drug development. The process requires navigating complex, high-dimensional design spaces where evaluations using traditional experimental methods or high-fidelity simulations are prohibitively time-consuming and expensive. This application note details key methodologies—Surrogate-Assisted Evolutionary Algorithms (SAEAs) and Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO)—that, when integrated as a Machine Learning Accelerated Genetic Algorithm (MLaGA), dramatically enhance the efficiency of computational nanoparticle discovery research. We frame these concepts within a practical workflow, provide structured quantitative comparisons, and outline detailed experimental protocols for researchers.

Core Terminology and Concepts

Surrogate Models in Optimization

A surrogate model (also known as a metamodel or emulator) is an engineering method used when an outcome of interest cannot be easily measured or computed directly. It is a computationally inexpensive approximation of a computationally expensive simulation or experiment [15]. In the context of MLaGA for nanoparticle discovery:

- Purpose: To mimic the behavior of a high-fidelity model (e.g., Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations of nanoparticle energy) as closely as possible while being cheaper to evaluate [15].

- Function: It acts as a surrogate fitness evaluator within a Genetic Algorithm (GA), drastically reducing the number of expensive fitness evaluations required [16] [17]. One study on Pt-Au nanoparticles reported a 50-fold reduction in required energy calculations using this approach [16].

Surrogate models can be broadly classified into two categories used in Single-Objective SAEAs [18]:

- Absolute Fitness Models: Directly approximate the exact fitness value of candidate solutions.

- Relative Fitness Models: Estimate the relative rank or preference of candidates rather than their absolute fitness values.

Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO)

Multi-Objective Optimization is an area of multiple-criteria decision-making concerned with mathematical optimization problems involving more than one objective function to be optimized simultaneously [19]. In nanoparticle design, conflicting objectives are common, such as maximizing catalytic activity while minimizing cost or material usage.

Key MOO concepts include:

- Pareto Optimality: A solution is Pareto optimal if no objective can be improved without degrading at least one other objective [19] [20]. A solution is dominated if another solution exists that is better in at least one objective and at least as good in all others [20].

- Pareto Frontier: The set of all Pareto optimal solutions, representing the optimal trade-offs between the conflicting objectives [19] [21].

Quantitative Data and Model Comparison

Performance of Surrogate Models in SAEAs

The selection of a surrogate model involves a critical trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy. The following table summarizes the characteristics of common surrogate types used in SAEAs, based on empirical comparisons [18] [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Surrogate Model Characteristics for SAEAs

| Surrogate Model Type | Computational Cost | Typical Accuracy | Key Strengths | Considerations for Nanoparticle Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Response Surfaces | Very Low | Medium | Simple, fast to build and evaluate | May be insufficient for complex, rugged energy landscapes |

| Kriging / Gaussian Processes | High | High | Provides uncertainty estimates, good for adaptive sampling | High cost may negate benefits for very cheap surrogates |

| Radial Basis Functions (RBF) | Low to Medium | Medium to High | Good balance of accuracy and speed | A common and versatile choice for initial implementations |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Medium (Training) | Medium to High | Effective for high-dimensional spaces | Ranking SVMs can preserve optimizer invariance |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | High (Training) | Very High | High flexibility and accuracy for complex data | Requires large training sets, risk of overfitting |

| Physical Force Fields (e.g., AMOEBA, GAFF) | Medium | Variable (System-Dependent) | Incorporates physical knowledge | Accuracy can be system-dependent; requires careful validation [17] |

MLaGA Efficiency Gains

The core benefit of integrating a surrogate model is a dramatic reduction in computational resource consumption.

Table 2: Documented Efficiency Gains from MLaGA Applications

| Study Context | Traditional Method Cost | MLaGA Cost | Efficiency Gain | Key Surrogate Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Distribution of Pt-Au Nanoparticles [16] | ~X Expensive Energy Calculations | 50x fewer calculations | 50-fold reduction | Machine Learning Model (unspecified) |

| Peptide Structure Search (GPGG, Gramicidin S) [17] | Months of DFT-MD Simulation | A few hours for GA search + DFT refinement | Reduction from months to hours | Polarizable Force Field (AMOEBApro13) |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Surrogate-Assisted Genetic Algorithm for Nanoparticle Discovery

This protocol outlines the steps for using an MLaGA to identify low-energy nanoparticle configurations, adapted from successful applications in peptide structure search [17].

1. Objective Definition: * Define the primary objective, e.g., find the atomic configuration of a Pt-Ligand nanoparticle that minimizes the system's potential energy.

2. Initial Sampling and Surrogate Training: * Design of Experiments (DoE): Use a sampling technique (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to select an initial set of nanoparticle configurations (50-200 individuals) across the design space. * High-Fidelity Evaluation: Run the expensive, high-fidelity simulation (e.g., DFT) on this initial population to obtain accurate fitness values (energy). * Surrogate Model Construction: Train a chosen surrogate model (e.g., a polarizable force field or an RBF network) on the input-output data (nanoparticle configuration -> energy) from the initial sample.

3. Iterative MLaGA Loop: * GA Search with Surrogate: Run a standard Genetic Algorithm (with selection, crossover, and mutation). The surrogate model, not the high-fidelity simulation, is used to evaluate the fitness of candidate solutions. * Infill Selection: From the GA population, select a small subset (e.g., 5-10) of the most promising candidates based on surrogate-predicted fitness (and uncertainty, if available). * High-Fidelity Validation & Update: Evaluate the selected candidates using the high-fidelity simulator (DFT). * Database Update: Add the new [configuration, true fitness] data pairs to the training database. * Surrogate Model Update: Re-train the surrogate model on the enlarged database to improve its accuracy for the next iteration. * Convergence Check: Repeat steps a-d until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations, no improvement in best fitness for several generations, or a target fitness is reached).

4. Final Analysis: * The best-performing configurations validated by high-fidelity simulation are the final output of the optimization.

Protocol: Multi-Objective Optimization for Nanoparticle Design

This protocol describes how to generate a Pareto frontier for a multi-objective problem, such as designing a nanoparticle for both high efficacy and low cytotoxicity.

1. Objective Definition:

* Define the conflicting objectives. For a drug delivery nanoparticle:

* Objective 1: Maximize Drug Loading Capacity (f_load).

* Objective 2: Minimize Predicted Cytotoxicity (f_tox).

2. Method Selection and Implementation (Weighted Sum Method):

* Aggregate Objective: Combine the multiple objectives into a single scalar objective function:

F_obj = w1 * (f_load / f_load0) - w2 * (f_tox / f_tox0)

where w1 and w2 are weighting coefficients ( w1 + w2 = 1), and f_load0, f_tox0 are scaling factors to normalize the objectives to similar magnitudes [21].

* Systematic Weight Variation: Perform a series of single-objective optimizations (using a GA or MLaGA) where the weights (w1, w2) are systematically varied (e.g., (1.0, 0.0), (0.8, 0.2), ..., (0.0, 1.0)).

* Solution Collection: Each optimization run with a unique weight vector will yield one (or a few) Pareto optimal solution(s). Collect all non-dominated solutions from all runs.

3. Post-Processing and Decision Making:

* Construct Pareto Frontier: Plot the objective values of all collected non-dominated solutions. This scatter plot represents the Pareto frontier.

* Trade-off Analysis: Analyze the frontier to understand the trade-offs. For example, how much must f_tox increase to achieve a unit gain in f_load?

* Final Selection: Use domain expertise or higher-level criteria to select the single best-compromise solution from the Pareto frontier.

Visualizing the MLaGA Workflow for Nanoparticle Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the iterative interaction between the genetic algorithm, the surrogate model, and the high-fidelity simulator.

Visualizing Multi-Objective Optimization and Pareto Concepts

This diagram clarifies the core concepts of Pareto optimality and the structure of a multi-objective optimization process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers implementing an MLaGA pipeline for nanoparticle discovery, the following computational and material "reagents" are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MLaGA-driven Nanoparticle Discovery

| Category | Item / Software / Method | Function / Purpose in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Environments | Python (with libraries like NumPy, Scipy) / Julia | Primary programming languages for implementing the GA, surrogate models, and workflow automation. |

| Surrogate Modeling Libraries | Surrogate Modeling Toolbox (SMT) [15] / Surrogates.jl [15] | Provides a library of pre-implemented surrogate modeling methods (e.g., Kriging, RBF) for easy integration and benchmarking. |

| High-Fidelity Simulators | Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes (e.g., VASP, Gaussian) [17] | Provides the "ground truth" evaluation of nanoparticle properties (e.g., energy, stability) for training and validating the surrogate model. |

| Approximate Physical Models | Classical Force Fields (e.g., GAFF, AMOEBA) [17] / Semi-Empirical Methods (e.g., PM6, DFTB) | Serves as a physics-informed, medium-accuracy surrogate to pre-screen candidates before final DFT validation. |

| Optimization Algorithms | Genetic Algorithm / Evolutionary Algorithm Libraries | Provides the core search engine for exploring the configuration space of nanoparticles. |

| Nanoparticle Characterization | Scanning/Transmission Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) [22] [23] | Used for experimental validation of predicted nanoparticle size, shape, and morphology. |

| Nanoparticle Synthesis | Bottom-Up Synthesis (e.g., Chemical Vapor Deposition) [22] [24] | Physical methods to synthesize the computationally predicted optimal nanoparticle structures. |

From Code to Cure: Implementing MLaGA Workflows for Real-World Nanoparticle Design

The discovery and optimization of functional nanomaterials, such as nanoparticle (NP) alloys, are impeded by the vastness of the compositional and structural search space. Conventional methods, like density functional theory (DFT), are computationally prohibitive for exhaustive exploration. This Application Note details a integrated experimental-computational pipeline that synergizes machine learning-accelerated genetic algorithms (MLaGA), droplet-based microfluidics, and high-content imaging (HCI) to establish a high-throughput platform for the discovery of bimetallic nanoalloy catalysts. We present validated protocols and data handling procedures to accelerate materials discovery, with a specific focus on Pt-Au nanoparticle systems.

The convergence of computational materials design and experimental synthesis is pivotal for next-generation material discovery. Genetic algorithms (GAs) are robust metaheuristic optimization algorithms inspired by Darwinian evolution, capable of navigating complex search spaces to find ideal solutions that are difficult to predict a priori [7]. However, their application with accurate energy calculators like DFT has been limited due to computational cost [7].

The machine learning-accelerated genetic algorithm (MLaGA) surmounts this barrier by using a machine learning model, such as Gaussian Process regression, as a surrogate fitness evaluator, leading to a 50-fold reduction in required energy calculations compared to a traditional GA [7] [25] [9]. This computational efficiency enables the feasible discovery of stable, compositionally variant nanoalloys.

This protocol describes the integration of this computational search with two advanced experimental techniques: microfluidics for controlled, high-throughput synthesis and high-content imaging for deep morphological phenotyping. This pipeline creates a closed-loop system for rapid nanoparticle discovery and characterization.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and data flow within the integrated discovery pipeline.

Protocols and Methodologies

Computational Search with MLaGA

The MLaGA protocol is designed to efficiently locate the global minimum energy structure and the convex hull of stable minima for a given nanoparticle composition.

Key Materials & Software

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Search

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) Framework | A metaheuristic that performs crossover, mutation, and selection on a population of candidate structures to evolve optimal solutions [7]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regression Model | A machine learning model that acts as a fast, surrogate fitness (energy) evaluator, dramatically reducing the number of expensive energy calculations required [7]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | The high-fidelity, computationally expensive energy calculator used to validate candidates and train the ML model [7]. |

| Effective-Medium Theory (EMT) | A less accurate, semi-empirical potential used for initial benchmarking and rapid testing of the algorithm [7]. |

Detailed Protocol: MLaGA for Pt-Au Nanoalloys

- Problem Initialization: Define the template structure (e.g., 147-atom Mackay icosahedron) and the compositional range (e.g., PtxAu147-x for (x \in \left[ {1,146} \right])) [7].

- Initial Population Generation: Create a starting population of candidate nanoparticles with random chemical ordering (homotops).

- Fitness Evaluation (Initial): Calculate the excess energy of the initial population using an energy calculator (e.g., EMT or DFT).

- ML Model Training: Train the GP regression model on the initial dataset of structures and their calculated energies.

- Nested Surrogate GA:

- A nested GA performs multiple generations of evolution (crossover, mutation, selection) using the trained ML model as a cheap fitness predictor.

- This step screens thousands of candidates computationally without performing expensive energy calculations.

- Master GA Evaluation: The final population from the nested GA is evaluated with the high-fidelity energy calculator (DFT).

- Population Update & Iteration: The master GA population is updated with the new, fit candidates. Steps 4-6 are repeated until convergence.

- Convergence Criteria: The search is considered converged when the ML surrogate model can no longer find new candidates predicted to be better than the current best, effectively stalling the search [7].

Performance Data

Table 2: MLaGA Performance Benchmark for a 147-Atom Pt-Au Icosahedral Particle

| Search Method | Approx. Number of Energy Calculations | Reduction Factor vs. Traditional GA |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional 'Brute Force' GA | ~16,000 | 1x (Baseline) [7] |

| MLaGA (Generational) | ~1,200 | 13x [7] |

| MLaGA (Pool-based with Uncertainty) | ~280 | 57x [7] |

Microfluidic Synthesis of Nanoparticles

Intelligent microfluidics enables the automated, high-throughput synthesis of candidate nanoparticles identified by the MLaGA with precise control over reaction conditions [26].

Key Materials

- Photolithography Setup: For fabricating high-precision silicon masters with intricate microchannel designs [26].

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS): A biocompatible, transparent elastomer used for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices via soft lithography [26].

- Metal Precursor Solutions: Chloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6) and Gold(III) chloride (HAuCl4) solutions in controlled concentrations.

- Reducing Agent Solution: Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) or ascorbic acid.

- Syringe Pumps: For precise control of fluid flow rates.

Detailed Protocol: Droplet-Based Synthesis

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a PDMS-based droplet microfluidic device using standard soft lithography techniques, featuring flow-focusing geometry for droplet generation [26].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare the aqueous phase containing the metal precursors and the oil phase (continuous phase) containing a surfactant.

- Device Priming: Load the oil phase into the device to prime the channels.

- Droplet Generation: Simultaneously pump the aqueous and oil phases into the device at optimized flow rates. The flow-focusing geometry will break the aqueous stream into monodisperse droplets.

- In-situ Reduction: Introduce the reducing agent solution via a separate inlet to mix with the droplet stream, initiating nanoparticle synthesis within each droplet.

- Collection & Analysis: Collect the emulsion at the outlet and break the droplets to retrieve the synthesized nanoparticles for characterization.

High-Content Imaging and Phenotypic Analysis

High-content imaging (HCI) provides deep morphological phenotyping of synthesized nanoparticles or biological systems affected by them, generating rich data for validation and model retraining [27].

Key Materials

- High-Content Imager: Automated high-resolution microscope system (e.g., confocal or widefield).

- Cell Stains (for biological assays):

- Image Analysis Software: Software capable of segmenting individual cells/particles and extracting morphological features.

Detailed Protocol: Morphological Profiling

- Sample Preparation: For biological susceptibility testing (e.g., Salmonella Typhimurium), expose isolates to the synthesized nanoparticles or antimicrobials over a time course (e.g., 24 hours, sampling every 2 hours) [27].

- Staining: Treat samples with a panel of fluorescent stains to mark different cellular compartments.

- Automated Imaging: Plate samples in multi-well plates and use the HCI system to automatically capture high-resolution images from multiple sites per well.

- Image Analysis & Feature Extraction: Use the analysis software to segment individual cells and extract ~65 morphological, intensity, and texture features (e.g., cell length, area, fluorescence intensity) for each cell [27].

- Data Aggregation: Average the features from all cells in a field of view to create a single datapoint for analysis.

The workflow for HCI data acquisition and analysis is detailed below.

Data Analysis and ML Classification

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) to visualize high-dimensional imaging data and observe clustering by treatment or susceptibility [27].

- Machine Learning Classification: Train a random forest classifier on the aggregated imaging features. The model can learn to predict properties like antimicrobial susceptibility based solely on morphological characteristics, without prior knowledge of the resistance phenotype or direct exposure to the drug [27]. This model can be used to rapidly characterize new samples.

Data Integration and Closing the Loop

The power of this pipeline is realized by integrating data from all three modules. The morphological data from HCI serves as a rapid, high-throughput validation step for the nanoparticles synthesized by the microfluidic platform. This experimental data can be fed back into the MLaGA to refine the surrogate model, constraining the search space with real-world observations and creating an active learning loop that continuously improves the discovery process.

The discovery and optimization of novel nanoparticles represent a formidable challenge in nanomedicine, characterized by vast combinatorial design spaces and complex, often non-linear, structure–function relationships. Traditional trial-and-error approaches are notoriously resource-intensive, time-consuming, and often fail to predict clinical performance [28]. Within this landscape, active learning (AL) has emerged as a powerful machine learning (ML) paradigm to accelerate discovery. By strategically selecting which experiments to perform, AL aims to maximize learning or performance while minimizing the number of costly experimental iterations [29] [30].

The core challenge in applying active learning lies in navigating the exploration-exploitation trade-off. Exploration involves selecting samples to minimize the uncertainty of the surrogate ML model, thereby enhancing its global predictive accuracy. In contrast, exploitation focuses on selecting samples predicted to optimize the target objective function, such as high cellular uptake or a specific plasmonic resonance [29] [30]. Striking the right balance is critical for the efficient navigation of the design space. This application note details protocols and frameworks for implementing active learning, with a specific focus on balancing this trade-off for optimal nanoparticle formulation within a broader thesis investigating Machine Learning Accelerated Genetic Algorithms (MLaGA).

Core Active Learning Framework and the Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off

Active learning operates through an iterative, closed-loop workflow. A surrogate model is initially trained on a small dataset. This model then guides each subsequent cycle by selecting the most informative samples to test next based on an acquisition function. The new experimental results are added to the training set, and the model is updated, creating a continuous feedback loop that refines the understanding of the design space [29] [30].

The acquisition function is the primary mechanism for managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off. The table below summarizes common strategic approaches to this dilemma.

Table 1: Strategic Approaches to the Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off in Active Learning

| Strategy | Core Principle | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration-Based | Selects samples where the model's prediction uncertainty is highest. Aims to improve the overall model accuracy [29]. | Early stages of learning or when the design space is poorly understood. |

| Exploitation-Based | Selects samples predicted to have the most desirable property (e.g., highest uptake, target resonance) [29]. | When the primary goal is immediate performance optimization. |

| Balancing Strategies | Explicitly considers both uncertainty and performance to select samples [29]. | The most common approach for robust and efficient optimization. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) | Frames exploration and exploitation as explicit, competing objectives and identifies the Pareto-optimal set of solutions, avoiding the bias of a single scalar score [31]. | For complex design spaces where the trade-off is not well-defined; provides a unifying perspective. |

A generic workflow for an active learning-driven discovery platform, integrating the key technological components, is illustrated below.

Application Note: Active Learning for High-Uptake Nanoparticle Design

Integrated Workflow for PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles

Ortiz-Perez et al. (2024) demonstrated a seminal integrated workflow for designing PLGA-PEG nanoparticles with high cellular uptake in human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-468) [30]. This protocol successfully combines microfluidic formulation, high-content imaging (HCI), and active machine learning into a rapid, one-week experimental cycle.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from the PLGA-PEG Active Learning Study [30]

| Metric | Initial Training Set | After Two AL Iterations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Uptake (Fold-Change) | ~5-fold | ~15-fold | Measured as normalized fluorescence intensity per cell. |

| Cycle Duration | - | 1 week per iteration | From formulation to next candidate selection. |

| Key Technologies | Microfluidics, HCI, Active ML | Microfluidics, HCI, Active ML | Integrated into a semi-automated platform. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Objective: To identify a PLGA-PEG nanoparticle formulation that maximizes cellular uptake using an active learning-guided workflow.

Materials and Reagents

- Polymers: PLGA, PLGA-PEG, PLGA-PEG-COOH, PLGA-PEG-NH₂.

- Solvents: Acetone (or other suitable water-miscible solvent), DiH₂O (anti-solvent).

- Microfluidic Device: Hydrodynamic Flow Focusing (HFF) chip with Y-junction.

- Cell Line: MDA-MB-468 human breast cancer cells.

- Staining Reagents: Hoechst (nuclei), CellMask (membrane), fluorescent dye (e.g., Cy5) for nanoparticle encapsulation.

- Equipment: Programmable syringe pumps, rotary valve, automated fluorescence microscope, CellProfiler software.

Procedure

Initial Library Design & Microfluidic Formulation:

- Define the design space by varying the ratios of the four polymer components and the solvent/anti-solvent Flow Rate Ratio (FRR).

- Use the automated microfluidic setup. The polymer mixtures are loaded into separate reservoirs connected to a rotary valve on the solvent pump. DiH₂O is loaded into the anti-solvent pump.

- For each formulation, the syringe pumps and rotary valve are programmed to mix the specified polymer combination and inject it into the middle channel at a constant flow rate. The anti-solvent flow rate is adjusted to achieve the target FRR, controlling nanoparticle size.

- Encapsulate a fluorescent dye in situ during the nanoprecipitation process to enable subsequent imaging.

High-Content Imaging (HCI) and Analysis:

- Seed MDA-MB-468 cells in a 96-well plate and incubate with the formulated nanoparticles.

- After incubation, fix the cells and stain nuclei and membranes.

- Acquire widefield fluorescence images using an automated microscope with appropriate channels (DAPI for nuclei, Cy5 for nanoparticles, etc.).

- Process images using a CellProfiler pipeline:

- Nuclear Segmentation: Identify individual cells using the nuclei channel.

- Membrane Segmentation: Define cytoplasmic regions using the membrane stain.

- Intensity Quantification: Measure the mean fluorescent intensity from the nanoparticle channel within the segmented cell areas. The distribution of cell intensities is expected to fit a gamma distribution [30].

Active Machine Learning Cycle:

- Model Training: Train a surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression, Random Forest) on the current dataset, where the inputs are the formulation parameters (component ratios, FRR) and the output is the measured cellular uptake.

- Candidate Selection: Use an acquisition function on the trained model to select the next set of promising formulations.

- For a balanced approach, use the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) or Expected Improvement (EI).

- For a more advanced, bias-free approach, implement a Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) that treats predicted performance (exploitation) and predictive uncertainty (exploration) as separate objectives to identify a Pareto front of optimal candidates [31]. The final candidate can be selected from this front using a method like the knee point or a reliability estimate [31].

- Iteration: The selected formulations are synthesized and tested (return to Step 1), and the data is used to update the model. This loop continues until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., uptake exceeds a target threshold, or performance plateaus).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Active Learning-Driven Nanoparticle Formulation

| Item | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| PLGA-PEG Copolymer Library | The core building blocks for self-assembling nanoparticles; varying ratios and end-groups (COOH, NH₂) control physicochemical properties like PEGylation, charge, and stability [30]. |

| Hydrodynamic Flow Focusing (HFF) Microfluidic Chip | Enables reproducible, automated, and size-tunable synthesis of highly monodispersed nanoparticles by controlling the solvent/anti-solvent mixing rate [30]. |

| Programmable Syringe Pumps with Rotary Valve | Provides automated and precise fluid handling for high-throughput formulation of different polymer compositions without manual intervention [30]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Cy5) | Used for in situ encapsulation during nanoprecipitation to label nanoparticles, enabling quantification of biological responses like cellular uptake via fluorescence microscopy [30]. |

| Automated Fluorescence Microscope | The core of High-Content Imaging (HCI); allows for rapid, automated acquisition of multiparametric data from cell-based assays in multi-well plates [30]. |

| CellProfiler Software | Open-source bioimage analysis software used to create automated pipelines for segmenting cells and quantifying nanoparticle uptake or other biological responses from HCI data [30]. |

Integration with Genetic Algorithms for MLaGA

The principles of active learning dovetail seamlessly with evolutionary strategies like Genetic Algorithms (GAs), forming a powerful MLaGA framework for nanoparticle discovery. GAs are population-based global optimization algorithms inspired by natural selection, where a population of candidate solutions (e.g., nanoparticle formulations) evolves over generations [32].

In an MLaGA framework, the active learning surrogate model can dramatically accelerate the GA's convergence. Instead of physically testing every individual in a population—a process that is often prohibitively slow and expensive—the ML model can be used to pre-screen and evaluate the fitness of candidate formulations [32]. This allows the algorithm to explore a much larger region of the design space computationally and only validate the most promising individuals experimentally. The experimental results then feedback to retrain and improve the surrogate model, creating a virtuous cycle. This hybrid approach is particularly potent for navigating high-dimensional design spaces where traditional methods struggle [28] [32].

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of this integrated MLaGA system.

Biomedical Rationale and Significance

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-polyethylene glycol (PLGA-PEG) nanoparticles represent a cornerstone of modern nanomedicine, offering a powerful platform for targeted drug delivery. These nanoparticles synergistically combine the biodegradable, biocompatible, and drug-encapsulating properties of PLGA with the stealth characteristics conferred by PEGylation, which reduces opsonization and recognition by the immune system [33]. This extended circulation time significantly increases the likelihood of nanoparticles reaching their intended target site, a crucial advantage in applications such as cancer therapy where it enables reduced dosage frequency while simultaneously improving therapeutic efficacy [33]. The versatility of PLGA-PEG nanoparticles allows for the encapsulation of a wide spectrum of therapeutic agents, including small molecules, proteins, and nucleic acids, protecting them from degradation and enhancing their absorption [33].

The optimization of these nanoparticles for targeted cellular uptake is paramount for overcoming fundamental challenges in drug delivery, particularly the specific targeting of cancer cells while protecting healthy tissues in conventional chemotherapy [33]. This targeting is achieved through a two-pronged approach: passive and active targeting. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect facilitates passive accumulation within tumor tissues due to their leaky vasculature and poor lymphatic drainage [34]. More precise active targeting is accomplished by functionalizing the nanoparticle surface with specific ligands, such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers, that preferentially bind to receptors overexpressed on target cells [33]. This active targeting enhances cellular uptake and intracellular drug release, leading to higher drug concentrations at the disease site and minimized off-target effects [33]. The optimization of nanoparticle properties—such as size, surface charge, PEG density, and ligand orientation—is therefore a critical determinant of their success, creating a complex, multi-variable problem ideally suited for advanced computational optimization methods like Machine Learning accelerated Genetic Algorithms (MLaGA).

Key Characteristics and Optimization Parameters

The performance of PLGA-PEG nanoparticles in targeted drug delivery is governed by a set of interdependent physicochemical properties. These properties must be carefully balanced to achieve optimal systemic circulation, tissue penetration, and cellular uptake. The following table summarizes the core parameters that require optimization.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Optimizing PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Type | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size [33] | 10 - 200 nm | Influences circulation time, tissue penetration, and cellular uptake; smaller particles typically exhibit deeper tissue penetration. |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) [33] | Near-neutral or slightly negative | Reduces non-specific interactions with serum proteins and cell membranes, prolonging circulation time. |

| PEG Molecular Weight & Density [33] | Tunable (e.g., 2k - 5k Da) | Forms a hydrophilic "stealth" corona that minimizes opsonization and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system. |