Machine Learning in Inorganic Materials Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery from Lab to Application

This article explores the transformative role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in revolutionizing the synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials.

Machine Learning in Inorganic Materials Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery from Lab to Application

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in revolutionizing the synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials. It systematically covers the foundational shift from traditional trial-and-error methods to data-driven intelligent synthesis paradigms. The content details the integration of automated hardware, such as microfluidic systems and robotic chemists, with advanced ML algorithms for parameter optimization and inverse design. It further addresses key challenges including data scarcity and model interpretability, while presenting validation case studies on quantum dots, gold nanoparticles, and zeolites. Finally, it discusses the future implications of this interdisciplinary field for accelerating the development of novel functional materials in biomedicine and beyond.

The New Synthesis Paradigm: From Trial-and-Error to Data-Driven Intelligence

The development of novel inorganic materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement across fields such as electronics, energy storage, and catalysis. However, the transition from laboratory discovery to industrial application is systematically constrained by the inherent limitations of conventional synthesis methods [1]. These traditional approaches, often reliant on manual operation and trial-and-error experimentation, face significant challenges in achieving adequate batch-to-batch reproducibility and scalable production [1]. This application note examines these critical limitations within the broader context of emerging machine-learning-assisted research, which aims to establish a new paradigm for efficient, precise, and reproducible nanomanufacturing.

Core Limitations of Traditional Synthesis Approaches

Traditional synthesis methods for inorganic nanomaterials, including those for quantum dots (QDs), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), and silica (SiO2) nanoparticles, achieve staged progress but encounter persistent bottlenecks that hinder their widespread industrial adoption [1]. The primary constraints are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Inorganic Nanomaterial Synthesis Methods

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenges | Impact on Research and Development |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Reproducibility | Low reproducibility between batches due to manual operations and subtle parameter variations [1]. | Difficulties in establishing reliable structure-property relationships; inconsistent experimental results. |

| Scaling Challenges | Difficulties in macroscopic preparation while maintaining material properties (e.g., particle size uniformity, dispersion) [1]. | Restricts supply for downstream applications; creates a "valley of death" between lab-scale and industrial-scale production. |

| Complex Quality Control | Inadequate control over critical quality attributes like particle size distribution, structural stability, and dispersion [1]. | Compromises performance and reliability in final applications. |

| Inefficient Resource Use | Heavy reliance on manual trial-and-error experimentation [1]. | Consumes significant workforce, time, and material resources; slows discovery cycles. |

| Precursor Selection | Half of all target materials require at least one "uncommon" precursor, and precursor choices are highly interdependent, defying simple rules [2]. | Makes synthesis design non-intuitive and heavily dependent on specialist heuristic knowledge. |

The Intelligent Synthesis Framework: A Machine Learning-Driven Paradigm

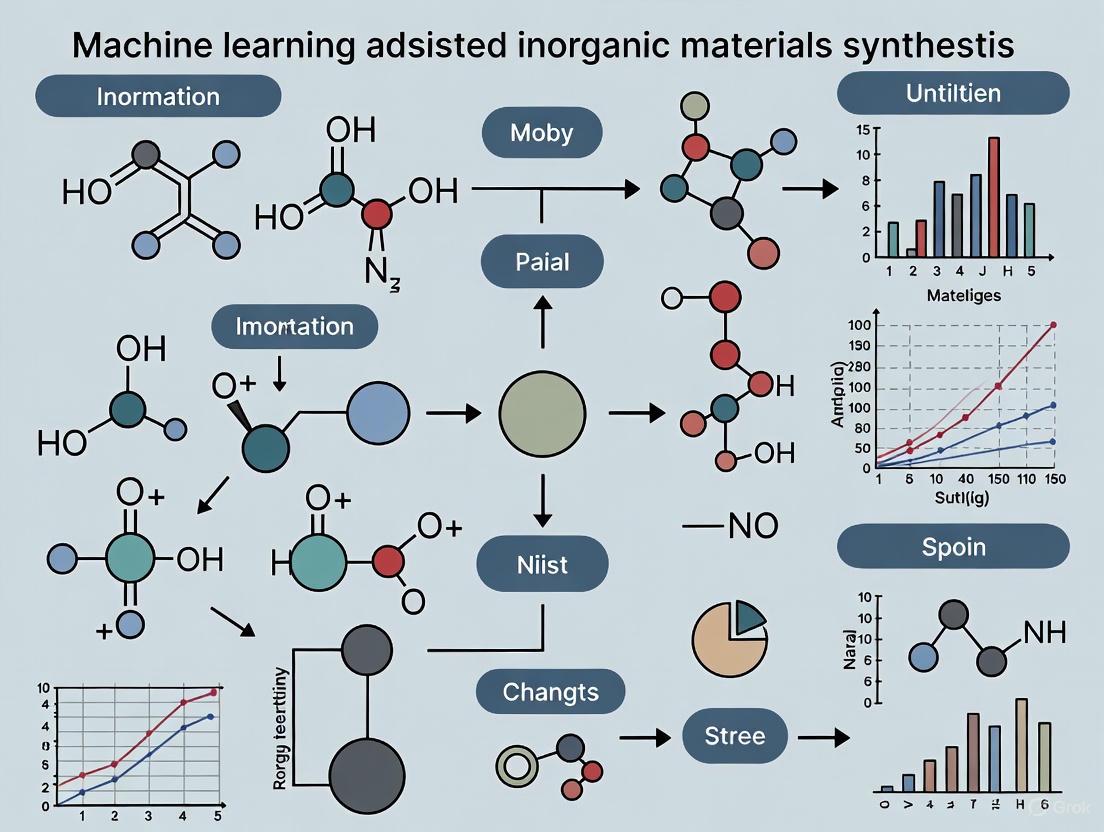

To address these challenges, the field is evolving toward a paradigm of intelligent synthesis. This framework integrates automated hardware, data-driven software, and human-machine collaboration to create a closed-loop system for material optimization and discovery [1]. The core components of this framework are visualized below.

Figure 1: The Intelligent Synthesis Framework. This diagram illustrates the integration of automated hardware, data resources, and AI software that enables closed-loop, reproducible nanomaterial production.

Experimental Protocols for Intelligent Synthesis Systems

Protocol: Automated Synthesis of Silica Nanoparticles Using a Dual-Arm Robotic System

This protocol benchmarks the automated synthesis of ~200 nm SiO2 nanoparticles against traditional manual methods, demonstrating enhanced reproducibility and efficiency [1].

- Objective: To achieve reproducible, high-throughput synthesis of silica nanoparticles with minimal human intervention.

- Principle: A dual-arm robot executes a converted manual synthesis protocol, handling all routine wet chemistry steps such as mixing and centrifugation within a modular hardware environment [1].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robotic SiO2 Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Alkoxide Precursor | Primary silica source for nanoparticle formation. | Common precursors include tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS). |

| Catalyst (e.g., Ammonia) | Catalyzes the hydrolysis and condensation reactions. | Concentration critically controls particle size and distribution. |

| Solvent (e.g., Ethanol) | Reaction medium for homogenizing reagents. | Purity affects nucleation kinetics and final product quality. |

| Washing Solvents | Purify synthesized nanoparticles via centrifugation. | Typically deionized water and ethanol; robotic arms automate transfer. |

Workflow Steps:

- System Initialization: Calibrate the dual-arm robot and initialize all modular units (liquid handlers, stirrers, centrifuges).

- Precursor Dispensing: The robot precisely measures and transfers specified volumes of silicon alkoxide precursor, catalyst, and solvent to the main reaction vessel.

- Reaction Control: The system maintains predetermined temperature and mixing speed for the specified reaction time.

- Quenching & Washing: Upon completion, the robot transfers the reaction mixture to a centrifuge tube, executes washing cycles, and re-disperses the purified nanoparticles.

- Product Characterization: Automated or offline analysis of particle size, distribution, and yield.

Outcome: The robotic system produces SiO2 nanoparticles with significantly higher batch-to-batch reproducibility and operates continuously, handling a workload difficult for a human to sustain [1].

Protocol: Microfluidic Synthesis and Optimization of Quantum Dots

This protocol utilizes an automated microfluidic platform for the high-throughput optimization and synthesis of semiconductor quantum dots, enabling real-time kinetic studies [1].

- Objective: To rapidly screen synthesis conditions and study the nucleation/growth kinetics of colloidal quantum dots.

Principle: A microfluidic or millifluidic reactor enables precise control over reagent mixing and residence time on a small scale, integrated with in-situ UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy for real-time monitoring [1].

Workflow Steps:

- Chip Priming: The microfluidic channels are primed with solvent to remove air bubbles.

- Droplet Generation: Precursor solutions are introduced to form discrete droplets or segmented flows within the reactor, minimizing residence time distribution.

- Oscillatory Flow (Optional): In some platforms, oscillatory motions of droplets are controlled to fine-tune reaction times without continuous flow, ideal for kinetic studies [1].

- In-Situ Characterization: The integrated UV-Vis spectrometer collects absorption data in real-time as the QDs form and grow within the flow system.

- Data Collection & ML Analysis: The spectral data is fed into machine learning algorithms to model the reaction kinetics and predict optimal synthesis parameters for desired QD properties [1].

Outcome: The platform drastically reduces reagent consumption and enables the rapid mapping of synthesis parameter spaces, providing high-quality data for understanding and optimizing nanocrystal growth [1].

The experimental workflow for this protocol is detailed below.

Figure 2: Microfluidic QD Synthesis Workflow. This diagram shows the closed-loop process from precursor injection to ML-driven optimization for quantum dot synthesis.

Data-Driven Methods and Precursor Recommendation

Overcoming the heuristic nature of precursor selection is a major hurdle. Machine learning models can learn materials similarity from large historical datasets to recommend viable precursor sets for novel target compounds [2]. One successful strategy involves:

- Encoding: Using a self-supervised neural network to create a vector representation of a target material based on its composition and known synthesis contexts.

- Similarity Query: Identifying the most similar material to a novel target within a knowledge base of over 29,900 text-mined solid-state synthesis recipes.

- Recipe Completion: Recommending and ranking precursor sets by adapting those used for the similar reference material, ensuring element conservation [2].

This data-driven recommendation pipeline achieves a remarkable success rate of at least 82% when proposing five precursor sets for each of 2,654 unseen test materials, effectively capturing decades of heuristic synthesis knowledge in a mathematical form [2]. The logic of this approach is illustrated in the following diagram.

Figure 3: Data-Driven Precursor Recommendation. This diagram outlines the ML-based workflow for recommending synthesis precursors for novel inorganic materials.

The limitations of traditional inorganic nanomaterial synthesis—poor reproducibility, scaling challenges, and heuristic-dependent design—present significant barriers to industrial application and rapid discovery. The integration of automated hardware systems, machine learning algorithms, and large-scale, text-mined synthesis data is establishing a new paradigm of intelligent synthesis. This framework moves beyond manual trial-and-error, enabling closed-loop optimization, predictive precursor recommendation, and ultimately, autonomous discovery. This shift is critical for accelerating the development of next-generation functional materials.

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are pivotal for addressing global challenges in energy, computing, and national security. Traditional material discovery, reliant on empirical studies and trial-and-error, is often a time-consuming process that can take decades from conception to application [3] [4]. This manual, serial approach creates significant bottlenecks in the research cycle. However, a new paradigm is emerging: Intelligent Synthesis. This methodology represents the convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), high-performance computing, and robotic automation to create a closed-loop, autonomous system for materials discovery and optimization [4]. This article details the application notes and experimental protocols underpinning this transformative approach, framed within the broader context of machine learning-assisted inorganic materials synthesis research for an audience of scientists and development professionals.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The adoption of Intelligent Synthesis is driven by compelling quantitative improvements over conventional methods. The table below summarizes key performance metrics as demonstrated by recent research and operational autonomous laboratories.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Intelligent Synthesis Systems

| Metric | Traditional Approach | Intelligent Synthesis Approach | Reference/System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Prediction Success Rate | N/A (Human intuition-based) | 82% (Top-5 precursor recommendation) | PrecursorSelector Model [2] |

| Stable Materials Discovered | ~20,000 known crystals | >2.2 million new stable crystals predicted | Google DeepMind GNoME [5] [6] |

| High-Throughput Experimental Throughput | Low (Manual processing) | 20x increase in sample fabrication and testing | Autonomous Researcher for Materials Discovery (ARMD) [7] |

| Precursor Selection Coverage | Limited by expert knowledge | ~50% of targets use at least one uncommon precursor | Text-Mined Recipe Analysis [2] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Data-Driven Precursor Recommendation for Solid-State Synthesis

Principle: This protocol uses a self-supervised machine learning model to recommend precursor sets for a target inorganic material by learning from a knowledge base of historical synthesis recipes [2]. It mimics the human approach of repurposing recipes for similar materials but does so quantitatively and at scale.

Materials:

- Knowledge Base: A dataset of 29,900 solid-state synthesis recipes extracted from scientific literature [2].

- Target Material: The chemical formula of the novel material to be synthesized.

- Computing Environment: Standard computing resources capable of running neural network inference.

Procedure:

- Encoding: Input the composition of the target material into the PrecursorSelector encoding model. The model projects the composition into a latent vector representation based on synthesis context learned from the knowledge base [2].

- Similarity Query: Compute the cosine similarity between the latent vector of the target material and the vectors of all materials in the knowledge base. Identify the k-nearest neighbors (reference materials) with the highest similarity scores.

- Recipe Completion: a. Referral: Propose the precursor set from the most similar reference material. b. Element Conservation Check: Verify if the proposed precursors contain all elements present in the target material. c. Conditional Prediction: If elements are missing, use a masked precursor completion (MPC) task to predict the most likely precursors to complete the set, conditioned on the already-referred precursors [2].

- Ranking & Output: Output a ranked list (e.g., top 5) of recommended precursor sets for experimental validation.

Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis and Characterization Loop

Principle: This protocol integrates AI-driven prediction with robotic synthesis and high-throughput characterization to create a closed-loop system for accelerated materials discovery, as implemented in systems like A-Lab and ARMD [4] [7].

Materials:

- AI Prediction Models: Trained models for predicting stable crystal structures and synthesis pathways (e.g., GNoME, MatterGen) [5] [6].

- Robotic Synthesis System: Automated platform for sample fabrication, such as a blown powder directed energy deposition (DED) additive manufacturing system [7].

- High-Throughput Characterization: Automated test rigs (e.g., robotic arms with lasers for high-temperature testing, X-ray diffraction (XRD), automatic porosimetry) [7].

- Data Management Platform: Centralized database to store all experimental data and outcomes.

Procedure:

- AI-Driven Design: Use generative AI or graph neural networks to propose candidate materials with desired target properties (e.g., high-temperature stability) [6] [7].

- Down-Selection: Apply physics-based and synthesizability filters to narrow the candidate list to a feasible number for experimental validation [7].

- Autonomous Synthesis: a. Program the robotic synthesis system (e.g., DED) to fabricate hundreds of unique samples on a single build plate, varying composition and processing parameters [7]. b. Use custom-designed sample geometries tailored for subsequent mechanical testing.

- Robotic Characterization: a. Transfer the build plate to an automated test station. b. Execute predefined property tests (e.g., tensile strength, high-temperature performance) using a robotic arm. The arm can be equipped with tools like lasers to apply thermal stress during testing [7].

- Data Analysis & Bayesian Optimization: a. Automatically analyze characterization data (e.g., XRD patterns, stress-strain curves). b. Feed the results into a Bayesian optimization model. The model suggests the next, more promising set of candidates and parameters to synthesize and test, balancing exploration and exploitation [4].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 until a material meets the target performance criteria or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the logical relationships and workflows central to Intelligent Synthesis.

Diagram 1: Intelligent Synthesis Closed Loop

Diagram 2: Precursor Recommendation Engine

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This section details key computational and experimental "reagents" essential for implementing Intelligent Synthesis workflows.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Solutions for Intelligent Synthesis

| Item | Function / Description | Example Tools / Models |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Knowledge Base | A database of historical synthesis recipes used to train ML models for precursor recommendation and condition prediction. | Text-mined datasets from scientific literature (e.g., 29,900 recipes) [2]. |

| Materials Foundation Models (FMs) | Large, pretrained AI models for general-purpose tasks like property prediction, crystal structure generation, and synthesis planning. | GNoME, MatterGen, MatterSim [5] [6]. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | An AI architecture used for inverse design, generating candidate material structures that meet a target property. | Samsung's patented inverse design system [5]. |

| Automated Synthesis Platform | Robotic systems that fabricate material samples with minimal human intervention, enabling high-throughput experimentation. | Blown Powder Directed Energy Deposition (DED) [7]. |

| High-Throughput Characterization Rig | Automated systems for rapidly testing the properties (e.g., mechanical, thermal) of synthesized samples. | Robotic arm with integrated laser heating for high-temperature testing [7]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | An AI model that suggests the most promising experiments to run next, optimizing the discovery process. | Custom models for active learning and candidate prioritization [4]. |

Intelligent synthesis systems represent a paradigm shift in inorganic materials research, moving from traditional trial-and-error methods towards a data-driven, closed-loop approach. These systems integrate advanced hardware, sophisticated software algorithms, and comprehensive data management to accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel materials. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated framework addresses critical bottlenecks in nanomaterial synthesis, including poor batch reproducibility, scaling challenges, and complex quality control requirements [8]. The core components work synergistically to enable autonomous experimentation, dramatically reducing development timelines and resource consumption while improving success rates in materials innovation.

Hardware Architecture for Automated Synthesis

The hardware foundation of an intelligent synthesis system enables precise parametric control, real-time monitoring, and automated execution of experimental procedures. Two predominant architectures have emerged: microfluidic-based platforms and robot-assisted workstations.

Microfluidic Reactor Systems

Microfluidic technology provides exquisite control over reaction conditions at microscopic scales, enabling high-throughput experimentation with minimal reagent consumption [8]. These systems are particularly valuable for optimizing semiconductor nanocrystals and metal nanoparticles.

Key Implementation Protocol: Millifluidic Reactor for Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis

- Apparatus Setup: Assemble a millifluidic reactor with integrated UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy and tangential flow filtration capabilities [8]. The reactor should include ports for functionality expansion and enhancement upgrades.

- Fluidic Control: Implement precise pumping systems for controlled reagent introduction and mixing. Utilize oscillatory droplet motion to eliminate residence time limitations in continuous-flow systems [8].

- In Situ Monitoring: Integrate online optical detection systems (e.g., UV-Vis spectroscopy) for real-time monitoring of nanoparticle formation and growth kinetics.

- Quality Control: Implement automated sampling and characterization loops using integrated filtration systems for size-selective separation and purification.

- Scalability: Design with parallelization capabilities for gram-scale production while maintaining precise control over morphological parameters such as aspect ratio in gold nanorods [8].

Robotic Automation Platforms

Robotic systems provide flexible automation for conventional laboratory equipment, enabling the execution of complex synthesis protocols with minimal human intervention.

Key Implementation Protocol: Dual-Arm Robotic System for Oxide Nanoparticle Synthesis

- System Configuration: Deploy a dual-arm robotic system with modular design for interfacing with standard laboratory equipment (vortex mixers, centrifuges, heating blocks) [8].

- Protocol Translation: Convert manual synthesis protocols (e.g., for SiO₂ nanoparticles) into automated processes by decomposing steps into discrete robotic actions [8].

- Environmental Control: Implement controlled workspace with scheduling algorithms to coordinate robotic movements and equipment access.

- Exception Handling: Program error recovery routines for common failure modes (clogged dispensers, misaligned containers).

- Validation: Benchmark automated synthesis against manual protocols by comparing product quality (size distribution, yield) and process efficiency [8].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Intelligent Synthesis Hardware Platforms

| Platform Type | Throughput Capacity | Reagent Consumption | Synthesis Scale | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Systems | High (parallel reactors) | Very Low (µL-mL range) | Milligram to Gram | Quantum dots, gold nanoparticles, perovskite NCs [8] |

| Robot-Assisted Workstations | Medium (sequential experiments) | Standard laboratory scale | Gram to Multigram | Silica nanoparticles, metal oxides, solid-state materials [8] |

| Modular Dual-Arm Robots | Flexible (modular) | Standard laboratory scale | Gram scale | Reproducible synthesis of various inorganic nanomaterials [8] |

Software and Algorithmic Infrastructure

The software layer transforms automated hardware into intelligent systems through machine learning algorithms that plan experiments, optimize parameters, and extract knowledge from multidimensional data.

Machine Learning Approaches

Intelligent synthesis employs diverse machine learning paradigms, each with distinct strengths for materials research applications:

- Supervised Learning: Used to map synthesis parameters to material properties using algorithms including random forest, support vector regression, and graph neural networks [9]. Applications include predicting processing temperatures and final material characteristics.

- Generative Models: Create novel molecular structures and synthesis pathways conditioned on desired properties. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) learn joint probability distributions of structure-property relationships to propose candidate materials with optimized characteristics [5].

- Reinforcement Learning: Optimizes synthesis protocols through iterative experimentation, where the algorithm receives rewards for improvements in target properties [9].

- Language Models: Recently demonstrated capability to recall synthesis conditions and propose precursor combinations for inorganic materials, achieving up to 53.8% Top-1 accuracy in precursor prediction [10].

Data Augmentation with Language Models

The limited size of experimental datasets constrains ML model performance. Language models (LMs) can generate synthetic synthesis recipes to expand training data as detailed below.

Diagram 1: Data augmentation workflow with language models

Key Implementation Protocol: LM-Generated Data Augmentation for Solid-State Synthesis

- Model Selection: Employ ensemble of off-the-shelf language models (GPT-4.1, Gemini 2.0 Flash, Llama 4 Maverick) without task-specific fine-tuning [11].

- Prompt Engineering: Design context-rich prompts with 40 in-context examples from held-out validation datasets to guide recipe generation [11].

- Ensemble Method: Combine predictions from multiple LMs to enhance accuracy and reduce inference cost by up to 70% [11].

- Dataset Curation: Generate 28,548 synthetic solid-state synthesis recipes, representing a 616% increase over existing literature-mined datasets [11].

- Model Fine-tuning: Pretrain transformer-based models (SyntMTE) on combined literature-mined and synthetic data, then fine-tune for specific prediction tasks [11].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Synthesis Prediction Models

| Model Type | Precursor Prediction Accuracy (Top-1) | Calcination Temperature MAE (°C) | Sintering Temperature MAE (°C) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language Model (Ensemble) | Up to 53.8% [11] | <126 [11] | <126 [11] | Leverages implicit chemical knowledge, requires no fine-tuning |

| SyntMTE (Fine-tuned) | N/A | 98 [11] | 73 [11] | Specialized for synthesis condition prediction, highest accuracy |

| Reaction Graph Network | N/A | ~90 [11] | ~90 [11] | Graph-based representation of reactions |

| Tree-based Regression | N/A | ~140 [11] | ~140 [11] | Handles non-linear parameter relationships |

Data Management and Experimental Workflows

Effective data management forms the critical bridge connecting hardware execution and algorithmic intelligence in synthetic workflows.

Closed-Loop Experimental Workflow

The integration of hardware and software components creates an autonomous materials discovery pipeline as shown below.

Diagram 2: Closed-loop workflow for autonomous synthesis

Key Implementation Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization for Nanomaterial Synthesis

- Target Definition: Specify desired material properties (optical, electronic, structural) as optimization targets.

- Candidate Generation: Use generative models (GANs, diffusion models) to propose novel material structures matching target properties [5].

- Synthesis Planning: Employ ML models for precursor recommendation and condition prediction, using ensemble methods to improve reliability [11].

- Automated Execution: Execute synthesis protocols on robotic or microfluidic platforms with minimal human intervention.

- High-Throughput Characterization: Integrate inline characterization (spectroscopy, scattering) for real-time quality assessment.

- Data Analysis and Feedback: Apply ML to correlate process parameters with outcomes and update models to guide next experiment selection.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Intelligent Nanomaterial Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis | Compatibility Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Gold chloride (HAuCl₄), lanthanum nitrate (La(NO₃)₃), zirconyl chloride (ZrOCl₂) | Source of metallic elements in nanoparticle formation | Aqueous and organic phase compatibility; stability in microfluidic environments [8] |

| Shape-Directing Agents | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Control morphological development in nanocrystals | Critical for anisotropic structures; concentration optimization via ML [8] |

| Reducing Agents | Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄), ascorbic acid, citric acid | Convert metal precursors to elemental forms | Reduction kinetics impact nucleation and growth; temperature-sensitive [8] |

| Solvents & Carriers | Water, toluene, oleylamine, ethylene glycol | Reaction medium with tunable polarity and boiling point | Microfluidic compatibility requires viscosity and surface tension considerations [8] |

| Solid-State Precursors | Metal carbonates, oxides, hydroxides | Starting materials for solid-state reactions | Reactivity depends on surface area and morphology; ML predicts optimal combinations [11] |

Integrated Case Study: Solid-State Electrolyte Development

The power of intelligent synthesis systems is exemplified in the development of Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂ (LLZO) solid-state electrolytes, where traditional methods struggle with phase stability issues.

Key Implementation Protocol: Dopant-Dependent Sintering Optimization for LLZO

- Problem Definition: Cubic phase LLZO requires specific dopants and sintering conditions for optimal ionic conductivity [11].

- Data Collection: Curate literature data on LLZO synthesis with various dopants (Al, Ga, Ta, Nb) and their sintering profiles.

- Model Training: Fine-tune SyntMTE model on LLZO-specific data to predict dopant-dependent sintering temperatures [11].

- Validation: Compare model predictions with experimental observations of dopant effects on phase formation and conductivity.

- Optimization: Use model to recommend novel dopant combinations and sintering profiles for enhanced performance.

- Result: SyntMTE successfully reproduces experimentally observed dopant-dependent sintering trends, confirming its utility in guiding synthesis of complex functional ceramics [11].

Intelligent synthesis systems represent a transformative approach to inorganic materials research, integrating specialized hardware platforms, sophisticated AI algorithms, and comprehensive data management into cohesive discovery engines. The continued development of these systems—addressing challenges in data quality, model generalization, and cross-platform integration—promises to accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel materials for energy, electronics, and biomedical applications. As these technologies mature, they will increasingly enable researchers to navigate complex synthesis spaces with unprecedented efficiency and insight, fundamentally changing the paradigm of materials innovation.

The Evolution from Automated to Autonomous and Finally to Intelligent Synthesis Systems

The synthesis of novel inorganic materials is a critical driver of innovation across numerous sectors, including electronics, energy storage, and drug development. However, the traditional trial-and-error approach to discovery is often hindered by the limitations of conventional synthesis methods, which typically exhibit poor batch stability, significant scaling challenges, and complex quality control requirements [12]. This slow, resource-intensive process creates a major bottleneck in the material discovery pipeline.

The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally transforming this paradigm, enabling a progression from simple automation to fully intelligent synthesis systems. This evolution is marked by a growing capability for closed-loop operation, adaptive optimization, and sophisticated human-machine collaboration, dramatically accelerating the development of novel functional materials [12] [3]. These Application Notes detail this technological progression, providing structured data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows to guide researchers in implementing these advanced systems.

Defining the Evolutionary Stages

The transition to data-driven material synthesis can be categorized into three distinct, progressive stages, each characterized by increasing operational independence and decision-making complexity.

Table 1: Characteristics of Automated, Autonomous, and Intelligent Synthesis Systems

| Feature | Automated Systems | Autonomous Systems | Intelligent Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Execute pre-programmed, repetitive tasks | Self-optimize parameters for a single, predefined objective | Learn underlying principles; propose and explore novel synthesis pathways |

| Human Role | Direct supervision and intervention | High-level oversight and goal-setting | Collaborative partnership; interpretation of AI-generated insights |

| Data Utilization | Logs process data for offline analysis | Uses real-time data for iterative feedback and parameter adjustment | Synthesizes data across experiments to build predictive models and extract new knowledge |

| Key Technologies | Robotic arms, programmable controllers | Sensors, ML models (e.g., for Bayesian optimization), closed-loop control | Generative AI, mechanistic modeling, cross-domain knowledge integration [12] |

| Output | High-throughput, consistent reproductions of known materials | An optimized material or process for a specific target | Newly discovered materials and novel, efficient synthesis recipes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing advanced synthesis systems requires a foundation of specific hardware, software, and data resources.

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for ML-Assisted Inorganic Synthesis Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Synthesis Hardware | Enables rapid experimental iteration by parallelizing reactions. | Robotic liquid handlers, automated solid-dosing systems, multi-reactor arrays. |

| In Situ/Operando Characterization | Provides real-time data on material formation for closed-loop control. | In situ XRD [3], Raman spectroscopy, or mass spectrometry integrated into reactors. |

| Unified Language of Synthesis Actions (ULSA) | Standardizes the description of synthesis procedures for AI processing [13]. | A labeled dataset of 3,040+ procedures; enables NLP parsing of scientific literature. |

| Machine Learning Models | Predicts synthesis outcomes and recommends optimal experimental parameters. | Tree-based Ensembles (e.g., XGBoost, CatBoost): Often outperform other models on tabular data from experiments [14] [15]. Deep Learning: Can excel with complex, high-dimensional data or for generative tasks [15]. |

| Computational & Data Resources | Provides foundational data for feasibility prediction and model training. | Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [3], material databases (e.g., ICSD, Materials Project). |

Experimental Protocols for Intelligent Synthesis

Protocol: Autonomous Optimization of Quantum Dot Synthesis

This protocol outlines a closed-loop procedure for optimizing the properties of colloidal quantum dots, such as emission wavelength and quantum yield [12].

- Objective Definition: Define the target property (e.g., photoluminescence peak at 550 nm) and the parameter search space (e.g., precursor concentrations: 0.1-10 mM; temperature: 150-350°C; reaction time: 1-30 minutes).

- Initial Dataset & Model Training: Populate an initial dataset with 10-20 experiments based on a Design of Experiments (DoE) or historical data. Train a machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression or a Gradient Boosting Machine) to map synthesis parameters to the target property.

- Autonomous Optimization Loop: a. Suggestion: The ML model suggests the next set of synthesis parameters expected to yield the greatest improvement, often using an acquisition function like Expected Improvement. b. Execution: An automated synthesis platform (e.g., a continuous-flow or segmented-flow reactor) executes the suggested experiment. c. Characterization: An inline spectrophotometer measures the photoluminescence spectrum of the synthesized quantum dots. d. Update: The new parameter-outcome data pair is added to the dataset, and the ML model is retrained.

- Termination: The loop continues until the target property is achieved or performance plateaus (typically after 50-200 iterations).

- Validation: Manually validate the top-performing synthesis conditions with 3-5 replicate experiments to confirm reproducibility.

Protocol: Synthesis Feasibility Prediction for Novel Compounds

This protocol uses ML to assess the likelihood that a theoretically proposed inorganic compound can be successfully synthesized, guiding experimental prioritization [3].

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of known synthesized and non-synthesized (or "failed") materials from databases like the ICSD. Incorporate theoretically predicted compounds labeled as "unsynthesized."

- Feature Engineering: Calculate a set of descriptive features for each compound, including:

- Structural Descriptors: Formation energy from DFT, energy above the convex hull [3].

- Compositional Descriptors: Elemental properties (electronegativity, ionic radius), charge-balancing criteria [3].

- Synthetic Descriptors: Precursor properties, similarity to known synthetic routes (extractable via ULSA-based NLP [13]).

- Model Training and Selection: Train multiple ML classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, and a Neural Network) on the curated dataset. Use stratified k-fold cross-validation to evaluate performance metrics (ROC-AUC, F1-score). Select the best-performing model, where tree-based ensembles often lead for such tabular data [14] [15].

- Prediction and Interpretation: Apply the trained model to a list of candidate materials. The model outputs a synthesisability score. Use feature importance analysis (e.g., SHAP values) to understand which factors (e.g., low energy above hull) most influenced the prediction.

- Experimental Cross-Check: Recommend the top 5-10 candidates with the highest synthesisability scores for experimental validation.

Workflow Visualization of an Intelligent Synthesis System

The following diagram illustrates the integrated data flow and decision-making processes within an intelligent synthesis system, capable of both optimizing known procedures and proposing novel materials.

Quantitative Benchmarks for Model Selection

Selecting the appropriate machine learning model is critical for the success of synthesis prediction and optimization tasks. Performance varies significantly across model types and is highly dependent on dataset characteristics.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Models on Tabular Data Tasks

| Model Category | Example Models | Typical Accuracy (Classification) | Key Strengths | Ideal Use Case in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree-Based Ensemble | XGBoost, CatBoost, Random Forest | Often highest [14] [15] | Robust, handles tabular data well, efficient with categorical features (CatBoost) | Synthesis outcome prediction, parameter optimization from experimental data [14] |

| Deep Learning (DL) | MLP, TabNet, FT-Transformer | Variable (Can outperform others on specific data types) [15] | Excels with high-dimensional data (many parameters); potential for generative design | Complex inverse design, systems with rich, non-tabular sensor data |

| Classical/Linear Models | Logistic Regression, SVM | Competitive on small datasets | Highly interpretable, computationally efficient | Preliminary analysis, settings with severe computational constraints [14] |

Table 4: Dataset Characteristics Favoring Deep Learning Models

| Characteristic | Favors Deep Learning? | Practical Implication for Synthesis Data |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Rows (Samples) | Fewer rows can favor DL [15] | DL may be tested in early-stage projects with limited historical data. |

| Number of Columns (Features) | More columns can favor DL [15] | DL could be advantageous when using high-dimensional descriptor sets or raw spectral data. |

| High Kurtosis | Higher kurtosis can favor DL [15] | DL might perform better with data where features have peaky distributions with heavy tails. |

| Task Type | DL performance gap smaller for Classification vs. Regression [15] | Tree-based models may have a stronger advantage for predicting continuous outcomes (e.g., yield, particle size). |

The evolution from automated to intelligent synthesis systems represents a paradigm shift in inorganic materials research. By leveraging unified description languages like ULSA, implementing closed-loop autonomous optimization, and strategically applying machine learning models tailored to specific data characteristics, researchers can dramatically accelerate the discovery and development of next-generation materials. This transition from a human-led, trial-and-error process to a human-AI collaborative partnership not only enhances efficiency but also deepens our fundamental understanding of synthesis science, paving the way for previously unimaginable technological advancements.

AI in Action: Hardware, Algorithms, and Real-World Material Case Studies

The integration of advanced hardware architectures is revolutionizing the synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials, paving the way for a new paradigm of intelligent, data-driven research. Automated systems, particularly microfluidic reactors and dual-arm robotic platforms, are overcoming the limitations of traditional synthesis methods, which often suffer from poor reproducibility, scaling challenges, and complex quality control requirements [1]. When framed within the context of machine learning-assisted research, these hardware systems transform from mere automated executors to active participants in a closed-loop discovery cycle. They enable the high-throughput, reproducible generation of experimental data essential for training robust machine learning models, which in turn can autonomously optimize synthesis parameters and predict novel material properties [1] [16]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging these automated hardware architectures to accelerate inorganic materials discovery and development.

Microfluidic Reactors for Nanomaterial Synthesis

Microfluidic reactors are devices that manipulate small volumes of fluids through geometrically controlled environments at the micron scale, typically featuring channels between 10 and 300 microns [17]. Their operation under laminar flow conditions (low Reynolds number) eliminates back-mixing caused by fluid turbulence and enables diffusion-controlled reactions [17]. The key advantage of microfluidics lies in the high surface-area-to-volume ratio, which allows for rapid heat and mass transfer, leading to more efficient and controlled reactions compared to conventional bulk-batch systems [17].

This technology has proven particularly valuable for the synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs), which are defined as materials ranging from 1 to 100 nm in at least one dimension and are pivotal in industries ranging from pharmaceuticals to electronics [18]. The precise control over reaction conditions afforded by microfluidic devices directly influences critical NP characteristics such as size, polydispersity, and zeta potential, which are essential for applications in drug delivery, where targeting ability and intracellular delivery are highly size-dependent [18] [16].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Microfluidic Reactors in Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Performance Metric | Traditional Batch Reactor | Microfluidic Reactor | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer Efficiency | Lower due to larger volumes | High surface-area-to-volume ratio enables rapid heat transfer [17] | Improved thermal homogeneity; safer execution of exothermic reactions |

| Reagent Consumption | High volumes | Significantly reduced volumes (microliter to milliliter scale) [17] | Cost savings, especially for expensive reagents; greener synthesis |

| Reaction Control & Reproducibility | Lower due to mixing inefficiencies | Laminar flow and diffusion-controlled mixing enable precise parameter control [17] | Enhanced reproducibility and batch-to-batch consistency [1] |

| Synthesis Throughput | Single reactions | Capable of high-throughput screening via parallel "scale-out" [17] | Faster exploration of synthesis parameter space |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of Quantum Dots in an Oscillatory Microfluidic Platform

The following protocol is adapted from studies on the automated synthesis and optimization of semiconductor nanocrystals (Quantum Dots, QDs) [1].

1. Objective: To synthesize high-quality quantum dots (e.g., CdSe) and rapidly screen/optimize reaction parameters using an integrated microfluidic platform with in-situ characterization.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials: Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for QD Synthesis

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Metal Precursor Solution (e.g., Cadmium Oleate in 1-Octadecene) | Source of metal cations (Cd²⁺) for QD formation. |

| Chalcogenide Precursor (e.g., Trioctylphosphine Selenide, TOP-Se) | Source of anions (Se²⁻) for QD formation. |

| Coordinating Solvents (e.g., 1-Octadecene, Oleylamine) | Act as reaction medium and surface ligands to control nanocrystal growth and stability. |

| PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) Tubing Reactor | Core component of the microfluidic system; chemically inert. |

| Syringe Pumps | For precise delivery of reagent solutions into the reactor. |

| In-line UV-Vis Absorption Spectrophotometer | For real-time, in-situ monitoring of QD nucleation and growth kinetics. |

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: System Priming. Clean and purge the entire PTFE tubing-based microfluidic system with an inert solvent (e.g., toluene) followed by the coordinating solvent to remove any contaminants and moisture.

- Step 2: Precursor Preparation. Prepare the metal and chalcogenide precursor solutions in an inert atmosphere glovebox to prevent oxidation.

- Step 3: Reaction Execution.

- Load the precursor solutions into separate syringes mounted on precision syringe pumps.

- Initiate the flow of both precursors, allowing them to meet at a T-junction to form a segmented or continuous flow stream within the PTFE reactor.

- Instead of a single-pass continuous flow, utilize an oscillatory flow strategy. The platform controls the oscillatory motions of the reaction slugs/droplets within a temperature-controlled zone, precisely controlling the reaction residence time without being limited by the physical length of the reactor [1].

- Step 4: In-situ Monitoring & Data Collection. The oscillating reaction mixture passes through a flow cell integrated with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Absorbance spectra are collected at high frequency throughout the reaction, providing real-time data on the kinetics of nanocrystal nucleation and growth [1].

- Step 5: Product Collection & Analysis. Collect the synthesized QDs at the outlet. Analyze the final product using ex-situ techniques such as Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for size and morphology, and Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy for optical properties. This data is used to validate the in-situ UV-Vis measurements.

4. Integration with Machine Learning: The high-throughput, real-time dataset (UV-Vis kinetics and corresponding reaction parameters) generated by this platform is ideal for training machine learning models. These models can map synthesis parameters (e.g., temperature, precursor concentration, residence time) to product outcomes (e.g., particle size, optical properties), enabling the autonomous optimization of reaction conditions for desired QD characteristics [1] [16].

Dual-Arm Robotic Systems for Automated Workflows

Dual-arm robotic systems represent a flexible and modular approach to automating complex laboratory synthesis protocols. These systems, often housed in custom-built enclosures, use two articulated arms that mimic human dexterity to serve as a connecting link between various standardized laboratory equipment such as liquid handlers, centrifuges, vortexers, and heating stations [19]. This architecture is designed to translate manual synthesis protocols, typically documented as Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), into fully automated, code-driven processes [19].

A primary advantage of this platform is its exceptional flexibility. Unlike dedicated, single-purpose automation workstations, a modular dual-arm robot can be reprogrammed and reconfigured to perform a wide variety of chemical synthesis tasks, making it ideal for research environments where protocols change frequently [1] [19]. This flexibility directly addresses the challenges of reproducibility and scalability in nanomaterial synthesis by removing anthropomorphic variations and enabling continuous, unattended operation.

Table 3: Benchmarking Performance of Dual-Arm Robotic Synthesis

| Performance Metric | Manual Synthesis (Lab Technician) | Dual-Arm Robotic Synthesis | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel Time & Cost | Baseline | Reduction of up to 75% [19] | Frees expert personnel for higher-value tasks; reduces operational costs. |

| Dosing Accuracy | Subject to human error | High accuracy, enhanced via calibration curves for liquid handling [19] | Improved reproducibility and product quality (e.g., narrow size distribution). |

| Process Reproducibility | Lower due to operational variance | High, as all steps are parameterized and automated [19] | Essential for industrial application and quality control. |

| Operational Flexibility | High (cognitive ability) | High (modular design and programmable steps) [1] | Suitable for complex, multi-step synthesis protocols. |

Experimental Protocol: Reproducible Synthesis of Silica Nanoparticles

This protocol details the automated synthesis of monodisperse silica nanoparticles (SiO₂ NPs, ~200 nm) using a dual-arm robotic platform, as established in recent feasibility studies [19].

1. Objective: To automate the synthesis and purification of silica nanoparticles with high reproducibility and reduced personnel time, suitable for applications such as photonic crystals which require a very small size distribution [19].

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials: Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Automated Silica NP Synthesis

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Silicon alkoxide precursor for silica nanoparticle growth via hydrolysis and condensation. |

| Ethanol, Deionized Water | Solvent system for the reaction. |

| Aqueous Ammonia Solution (NH₄OH) | Catalyzes the hydrolysis and condensation of TEOS. |

| Dual-Arm Robot (e.g., with linear electric grippers) | Core system for transporting vessels and tools between modules [19]. |

| Programmable Liquid Handling Unit | For accurate dosing of liquids (ethanol, water, ammonia, TEOS). |

| Heating Stirrer with Magnetic Stirring | For mixing and heating the reaction mixture. |

| Laboratory Centrifuge | For purifying the synthesized nanoparticles via washing cycles. |

| Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) | The central control unit that coordinates all devices and executes the workflow [19]. |

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: System Initialization. Power on the robotic cell and all integrated devices. Initialize the PLC and the Human-Machine Interface (HMI). The robot performs a system check to confirm the positions of all tools and consumables.

- Step 2: Dosing of Solvents and Catalyst.

- The robot picks up a clean glass reaction vessel and places it under the liquid handling unit.

- The liquid handler dispenses precise volumes of ethanol, deionized water, and aqueous ammonia into the vessel as per the programmed recipe.

- Step 3: Mixing and Pre-heating.

- The robot places the vessel onto the heating stirrer, which activates magnetic stirring to mix the contents.

- The heating block is pre-heated to 80°C for 30 minutes to ensure a stable starting temperature for the reaction [19].

- Step 4: Initiation of NP Growth.

- The robot moves the vessel to the liquid handler for the addition of TEOS.

- The vessel is returned to the heating stirrer, which is now set to 69°C to maintain an internal reaction temperature of 60°C. The reaction proceeds with stirring for 2 hours to allow for NP growth [19].

- Step 5: NP Purification.

- Post-reaction, the robot transfers the NP suspension to centrifuge tubes.

- The tubes are placed in the centrifuge for a washing cycle: centrifugation, robot-assisted decanting of supernatant, and re-dispersion in deionized water using a vortexer. This wash cycle is repeated four times [19].

- Step 6: Product Storage.

- The final, purified NP dispersion is transferred to a storage container, which is capped and labeled by the robot, ready for subsequent analysis or use.

4. Integration with Machine Learning: The robotic platform is a foundational element for a machine-learning-driven laboratory. Every action and parameter (weights, volumes, temperatures, times) is digitally recorded by the PLC, creating a structured, high-fidelity dataset for every synthesis attempt. This data is crucial for building ML models that can identify critical process parameters and their correlations with product outcomes, ultimately enabling autonomous process optimization and quality control [1].

The discovery and synthesis of new inorganic materials are pivotal for advancements in aerospace, energy, and defense technologies. Traditional experimental approaches are often slow, costly, and struggle to explore vast compositional spaces efficiently. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful, data-driven tool to accelerate this process, enabling the prediction of material properties and the generation of novel candidate structures before laboratory synthesis. This Application Note details the implementation of two key ML algorithms—XGBoost and Transformer-based models—within the context of inorganic materials research. We provide structured protocols, quantitative performance data, and essential workflows to guide researchers in leveraging these tools for materials discovery and design.

Algorithm Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

XGBoost: Extreme Gradient Boosting

XGBoost is an advanced implementation of the gradient boosting framework, designed for efficiency, scalability, and high performance. It operates by sequentially building an ensemble of decision trees, where each new tree is trained to correct the errors made by the previous ones. The final prediction is the sum of the predictions from all trees in the ensemble [20] [21].

The algorithm's objective function incorporates both a loss function, which measures the model's prediction error, and a regularization term, which penalizes model complexity to prevent overfitting. The general form of the objective function is: ( obj(\theta) = \sum{i}^{n} l(y{i}, \hat{y}{i}) + \sum{k=1}^K \Omega(f{k}) ) where ( l(y{i}, \hat{y}{i}) ) is the loss function, and ( \Omega(f{k}) ) is the regularization term [21]. A key feature of XGBoost is its sparsity-aware algorithm for handling missing data, which allows it to make informed decisions about whether to send a missing value to the left or right child node during a tree split [20].

Transformer-Based Models

Transformer-based models represent a different class of ML algorithms, originally developed for natural language processing. These models utilize a self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of different parts of the input data, enabling them to capture complex, long-range dependencies [22]. In materials science, these models are trained on large datasets of material compositions, such as those from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), Materials Project, and Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), to learn the underlying "language" of inorganic chemistry [22]. Once trained, they can generate novel, chemically valid material compositions, offering a powerful tool for generative materials design.

Algorithm Comparison

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of XGBoost and Transformer-based models for materials science applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of XGBoost and Transformer-Based Models for Materials Science

| Feature | XGBoost | Transformer-Based Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Property prediction (regression/classification) | Generative design of new compositions |

| Underlying Principle | Ensemble of sequential decision trees with gradient boosting | Deep learning with self-attention mechanisms |

| Typical Input | Feature vectors (composition, structure, elastic moduli) [23] | Textual representations of chemical formulas [22] |

| Key Strength | High predictive accuracy, handles small datasets well, provides feature importance [23] [20] | High novelty, capable of de novo design, captures complex patterns [22] |

| Notable Performance | R² of 0.82 for oxidation temperature prediction [23] | Up to 97.54% of generated compositions are charge neutral [22] |

| Data Efficiency | Effective on datasets of hundreds to thousands of samples [23] | Requires large datasets (e.g., tens of thousands) for effective training [22] |

| Interpretability | Moderate (feature importance analysis possible) | Low ("black-box" nature) |

| Computational Demand | Moderate | High |

Application Notes for Inorganic Materials Research

Application 1: Predicting Multifunctional Properties with XGBoost

Predicting material properties such as Vickers hardness (HV) and oxidation temperature (Tp) is crucial for identifying candidates suitable for harsh environments. Hickey et al. demonstrated a workflow using two XGBoost models for this purpose [23].

Table 2: XGBoost Model Performance for Property Prediction [23]

| Property Predicted | Training Set Size | Key Descriptors | Model Performance (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vickers Hardness (H_V) | 1225 compounds | Composition, structure, predicted bulk/shear moduli [23] | Details not specified in source |

| Oxidation Temperature (T_p) | 348 compounds | Composition, structure, MBTR descriptors [23] | 0.82 |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental process for discovering new materials using these models.

Application 2: Generative Design with Transformer Models

For the generative design of novel inorganic materials, Transformer models learn composition patterns from existing crystal structure databases. Fu et al. benchmarked several transformer architectures, including GPT, GPT-2, GPT-Neo, GPT-J, BLMM, BART, and RoBERTa [22]. Their study showed that these models can generate chemically valid compositions with high rates of charge neutrality (up to 97.54%) and electronegativity balance (up to 91.40%), which is a significant enrichment over random sampling [22]. The training data can be tailored to bias the generation towards materials with specific properties, such as high band gaps [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building an XGBoost Model for Property Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for developing an XGBoost model to predict a target material property, such as hardness or oxidation temperature.

Pre-experiment Requirements:

- Computing Environment: Python environment with libraries:

xgboost,scikit-learn,pandas,numpy. - Data: A curated dataset of known materials and their target property.

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Feature Generation:

- Compile a dataset of inorganic compounds with known target property values. For hardness modeling, ensure data is from bulk polycrystalline samples and Vickers hardness tests [23].

- For each compound, generate a comprehensive set of descriptors. These typically include:

- Compositional Features: Elemental properties (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity) averaged over the composition.

- Structural Features: Derived from CIF files, such as packing fraction, density, and symmetry information [23].

- Elastic Descriptors: Predicted bulk and shear moduli, which can be obtained from DFT calculations or pre-trained ML models [23].

- Handle missing values and normalize the feature set.

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Split the data into training and testing sets.

- Utilize a grid search or randomized search with cross-validation (e.g.,

GridSearchCVin scikit-learn) to optimize key XGBoost hyperparameters [23]. Critical parameters include:max_depth: Maximum depth of a tree.learning_rate(eta): Step size shrinkage.subsample: Fraction of samples used for training each tree.colsample_bytree: Fraction of features used for training each tree.reg_alpha(alpha): L1 regularization term.reg_lambda(lambda): L2 regularization term.

- For enhanced robustness, employ a bagging strategy (e.g., averaging predictions from models trained with different random seeds) [23].

Model Validation:

- Validate the final model on a held-out test set of compounds that were not used during training or hyperparameter tuning.

- For high-confidence discovery, perform experimental validation by synthesizing top candidate materials predicted by the model and measuring their target properties [23].

Protocol 2: Hyperparameter Optimization with Improved PSO

The performance of XGBoost is highly dependent on its hyperparameters. This protocol describes an Improved Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO) method to automate and enhance this tuning process [24].

Pre-experiment Requirements:

- Software: Implementation of the standard PSO and XGBoost algorithms.

- Data: A labeled dataset for the classification or regression task.

Procedure:

- IPSO Initialization:

- Define the search space for the XGBoost hyperparameters to be optimized (e.g.,

max_depth,learning_rate,reg_alpha). - Initialize a swarm of particles, where each particle's position represents a potential set of hyperparameters.

- Implement improvements to the standard PSO:

- Master-Slave Groups: Divide the swarm into groups to strengthen local search capabilities [24].

- Adaptive Inertia Weight: Use a linear adaptive strategy to dynamically adjust the inertia weight, balancing global and local search [24].

- Adaptive Acceleration Factor: Adjust the acceleration factor during iterations to improve convergence [24].

- Define the search space for the XGBoost hyperparameters to be optimized (e.g.,

Fitness Evaluation:

- For each particle's hyperparameter set, train an XGBoost model on the training data.

- Evaluate the model's performance on a validation set (e.g., using accuracy or F1-score for classification).

- Use this performance metric as the fitness value for the particle.

Swarm Update and Convergence:

- Update the velocity and position of each particle based on its own best-known position and the swarm's global best-known position.

- Repeat the fitness evaluation and update steps until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations or no improvement in global fitness for a set number of rounds).

- The global best position upon termination provides the optimized hyperparameter set for the XGBoost model.

This section lists key computational "reagents" and resources required for implementing the machine learning workflows described in this note.

Table 3: Essential Resources for ML-Assisted Materials Discovery

| Resource / Solution | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Information File (CIF) | Standard format for storing crystal structure information; the primary source for structural descriptors. | Materials Project [23], ICSD |

| Elastic Tensor Data | Provides mechanical properties like bulk and shear moduli, which are critical descriptors for hardness models. | Computed via DFT in high-throughput databases [23] |

| Compositional Descriptors | Numerical features representing elemental properties (e.g., electronegativity, atomic radius) of a compound. | Magpie descriptors [23] |

| Structural Descriptors | Numerical features representing crystal structure (e.g., packing fraction, symmetry, density). | Derived from CIF files [23] |

| Materials Database | Source of training data for both predictive and generative models. | Materials Project [23], OQMD, ICSD [22] |

| Optimization Algorithm | Method for tuning ML model hyperparameters to maximize predictive performance. | Improved Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO) [24] |

Workflow Visualization: Integrated ML-Driven Materials Discovery

The following diagram synthesizes the protocols and applications above into a unified workflow for machine learning-assisted inorganic materials discovery, highlighting the complementary roles of predictive and generative models.

High-Throughput Data Acquisition and Real-Time In Situ Characterization

The integration of high-throughput data acquisition and real-time in situ characterization is revolutionizing inorganic materials synthesis within machine learning (ML)-assisted research frameworks. These methodologies are pivotal for overcoming traditional limitations in materials discovery, which often rely on slow, sequential trial-and-error approaches. By generating rich, continuous streams of high-fidelity experimental data, these techniques provide the essential fuel for training robust ML models, enabling the rapid identification of optimal synthesis parameters and the discovery of novel functional materials. This paradigm shift accelerates the development of advanced materials for applications in clean energy, electronics, and sustainable chemicals while significantly reducing resource consumption and experimental timelines [25] [26] [3].

This document details practical applications and standardized protocols for implementing these advanced methodologies, with a specific focus on their role in autonomous and ML-driven materials research. It provides a quantitative comparison of data acquisition strategies, step-by-step experimental workflows for both batch and continuous-flow systems, and a comprehensive toolkit of essential research solutions to facilitate adoption and implementation in research and development settings.

Quantitative Comparison of Data Acquisition Methodologies

The choice of data acquisition strategy profoundly impacts the volume, quality, and type of data available for ML training. The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of prevalent methodologies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of High-Throughput Data Acquisition Methodologies

| Methodology | Data Acquisition Rate | Key Measurable Outputs | Chemical Consumption per Data Point | Primary Application in ML Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Steady-State Screening [27] | ~100,000 tests/day (uHTS) | End-point measurements (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence intensity) | Microliters to milliliters | Primary screening and hit identification |

| Quantitative HTS (qHTS) [27] | Varies with concentration gradients | Full concentration-response curves (EC~50~, maximal response, Hill coefficient) | Higher than steady-state due to multiple concentrations | Pharmacological profiling and structure-activity relationship (SAR) modeling |

| Dynamic Flow Experiments [25] [26] | ≥10x higher than steady-state self-driving labs | Real-time, in-situ kinetic profiles (e.g., optical properties, reaction progression every 0.5s) | Dramatically reduced (nanoliters to microliters) | Continuous learning and high-resolution optimization of synthesis parameters |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening (HTS) for Material Property Optimization

This protocol outlines the use of automated HTS for identifying "hits"—compounds or synthesis conditions that produce a material with a desired property, forming the foundation for subsequent ML analysis.

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for HTS and Microfluidic Screening

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (96, 384, 1536-well) [27] | Standardized labware for parallel experimentation; well density dictates throughput. |

| Stock Plate Library [27] | A carefully catalogued collection of source plates containing diverse chemical compounds or precursor solutions. |

| Liquid Handling Robots [27] [28] | Automated pipetting systems for precise, nanoliter-scale transfer of liquids to create assay plates from stock plates. |

| Integrated Robotic System [27] | Transports assay plates between stations for sample addition, mixing, incubation, and final readout. |

| Sensitive Detectors [27] | Plate readers or high-content imagers for measuring spectroscopic, optical, or morphological properties of the synthesized materials. |

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Methodology

- Assay Plate Preparation: Using an automated liquid handler, transfer small volumes (nanoliters) of precursor or compound solutions from a stock plate library into the wells of a clean microtiter plate (96 to 1536 wells) to create an assay plate [27].

- Reaction Initiation: Dispense a consistent volume of a standardized reagent, such as a biological target (e.g., enzymes, cells) or a chemical precursor mixture, into all wells of the assay plate [27].

- Incubation and Automation: Incubate the plate under controlled conditions (e.g., temperature, atmospheric gas). An integrated robotic system moves the plate between stations for mixing and incubation as needed [27].

- End-Point Data Acquisition: After the incubation period, use a dedicated plate reader or imager to measure a specific signal from each well (e.g., fluorescence, absorbance, luminescence) [27].

- Data Processing and Hit Identification: Process the raw data grid (where each value corresponds to a well) using quality control (QC) metrics like the Z-factor or Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) to identify statistically significant "hits" from negative controls. Perform hit selection using methods such as z-score for screens without replicates or SSMD/t-statistic for screens with replicates [27].

3.1.3 Workflow Diagram: HTS Process

Protocol 2: Real-Time, Dynamic Flow Synthesis and Characterization

This protocol describes a cutting-edge "data intensification" strategy for self-driving labs, which captures continuous kinetic data of material synthesis, providing a rich dataset for ML models.

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

- Continuous Flow Reactor: A microfluidic chip or capillary system where precursors are continuously mixed and react while flowing [25].

- Precursor Solutions: Concentrated stock solutions of chemical precursors (e.g., Cd and Se precursors for CdSe quantum dots) [26].

- Precision Syringe Pumps: For controlled, continuous injection and variation of precursor solutions into the flow reactor [25].

- In-situ Spectrophotometer/Fluorometer: An integrated flow cell connected to a spectrometer for real-time monitoring of optical properties (e.g., absorbance, photoluminescence) [25] [26].

- Machine Learning Control Software: Custom software (e.g., Python-based) that controls the pumps and receives sensor data, using algorithms like Bayesian optimization to decide the next experiment [25] [26].

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Methodology

- System Priming: Prime the microfluidic flow reactor and all fluidic lines with an inert solvent to remove air bubbles and ensure stable flow conditions.

- Dynamic Flow Experiment Initiation: Program the syringe pumps to continuously vary the composition, flow rate, or temperature of the precursor streams entering the reactor. This creates a continuous gradient of reaction conditions over time, rather than discrete steps [25] [26].

- Real-Time In Situ Characterization: As the reacting solution flows through the microchannel, direct it through a flow cell integrated with analytical probes. Collect characterization data (e.g., UV-Vis absorption spectra, photoluminescence intensity) at a high frequency (e.g., every 0.5 seconds). This transforms a single continuous experiment into a dataset comprising thousands of time-resolved data points [25].

- Data Streaming to ML Model: Stream the high-volume characterization data and the corresponding experimental parameters in real-time to the ML control software.

- Autonomous Decision-Making: The ML algorithm uses the incoming data to update its internal model of the synthesis process. Based on the research objective (e.g., maximizing photoluminescence quantum yield), it calculates and autonomously implements the next set of optimal conditions by adjusting the pump parameters, creating a tight feedback loop [25] [26].

3.2.3 Workflow Diagram: Dynamic Flow Experiment in a Self-Driving Lab

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of these protocols relies on a suite of specialized tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Materials Synthesis

| Tool/Solution | Function in ML-Assisted Workflow |

|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handlers (e.g., Beckman Coulter Biomek i7) [28] | Enables precise, reproducible, and rapid dispensing of precursor solutions for both batch (HTS) and flow synthesis preparation, eliminating manual variability. |

| Integrated Robotic Workcells (e.g., with PreciseFlex robots) [28] | Provides full walk-away automation by physically linking incubators, liquid handlers, and imagers, ensuring standardized and continuous operation for long-term autonomous campaigns. |

| Automated Centrifuges (e.g., Bionex HiG4) [28] | Prepares samples (e.g., pellets cells or solid products) in a high-throughput manner for downstream analysis, integrating seamlessly into automated workcells. |

| High-Content Screening Systems (e.g., ImageXpress HCS.ai) [28] | Captures multiparametric data (morphology, fluorescence) from complex material systems or biological models, providing rich feature sets for ML analysis. |

| Microplate Readers (e.g., SpectraMax with SoftMax Pro) [28] | Provides rapid, quantitative end-point measurements (absorbance, fluorescence) for high-throughput validation and primary screening in plate-based formats. |

| Scheduling Software (e.g., Biosero Green Button Go) [28] | The "orchestrator" of the self-driving lab, managing the scheduling and execution of all hardware components to run complex, multi-step workflows without human intervention. |

The integration of machine learning (ML) into materials science has ushered in a new paradigm for the efficient discovery and synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials, moving beyond traditional, often inefficient, trial-and-error methods [29]. This data-driven approach is particularly transformative for optimizing synthesis processes with complex, multidimensional parameter spaces, such as the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) of two-dimensional (2D) materials. Among these, molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) is a layered transition metal dichalcogenide with promising applications in next-generation nanoelectronics, optoelectronics, and sensors due to its unique electronic properties and direct bandgap in monolayer form [30]. However, the large-area, controlled synthesis of high-quality MoS₂ via CVD remains challenging, as the final material's area and layer count are highly sensitive to a complex interplay of growth parameters [31]. This case study details the application of the XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) algorithm, a powerful and versatile machine learning tool, to model and optimize the CVD synthesis of 2D MoS₂. We frame this specific application within the broader context of advancing intelligent synthesis systems, which combine automated hardware, algorithmic intelligence, and human-machine collaboration to accelerate nanomaterial development and elucidate underlying synthesis mechanisms [1].

Background

The XGBoost Algorithm

XGBoost is a scalable, tree-based ensemble algorithm that implements gradient boosting with several key optimizations, including regularization, parallel processing, and tree pruning [32] [33]. Its ability to handle complex, non-linear relationships and provide feature importance rankings makes it exceptionally well-suited for tackling multifaceted materials synthesis problems. The algorithm's parameters can be categorized to guide the optimization process:

- General Parameters: Guide the overall booster type (e.g.,

gbtree,gblinear). - Booster Parameters: Control the individual tree construction (e.g.,

max_depth,learning_rate,subsample). - Learning Task Parameters: Define the learning objective and evaluation metrics [34] [33].

CVD Synthesis of MoS₂

The CVD growth of MoS₂ involves the reaction of molybdenum and sulfur precursors at high temperatures within a carrier gas flow. Critical parameters that influence the final material's area, layer count, and quality include [30]:

- Reaction temperature (

T) - Molybdenum-to-sulfur precursor ratio (

R) - Carrier gas flow rate (

Fr) - Reaction time (

Rt)

The complexity of interactions among these parameters makes ML an ideal tool for navigating this design space efficiently.

Experimental Protocols

Data Acquisition and Curation

Objective: To compile a robust dataset for training and validating the XGBoost model. Methodology:

- Data Collection: A total of 200 sets of experimental conditions and corresponding results for CVD-synthesized MoS₂ were collated from laboratory records and published literature [30].

- Data Preprocessing: Duplicate entries and inconsistent data were removed to ensure data quality.

- Feature and Target Definition:

- Input Features: Four key growth parameters were selected as model inputs: molybdenum-to-sulfur ratio (

R), carrier gas flow rate (Fr), reaction temperature (T), and reaction time (Rt) [30]. - Target Variable: The side-length of the synthesized triangular MoS₂ crystal was used as the target, serving as a direct proxy for the material's area [30].

- Input Features: Four key growth parameters were selected as model inputs: molybdenum-to-sulfur ratio (