Machine Learning for Solid-State Synthesis: Predicting Routes and Accelerating Materials Discovery

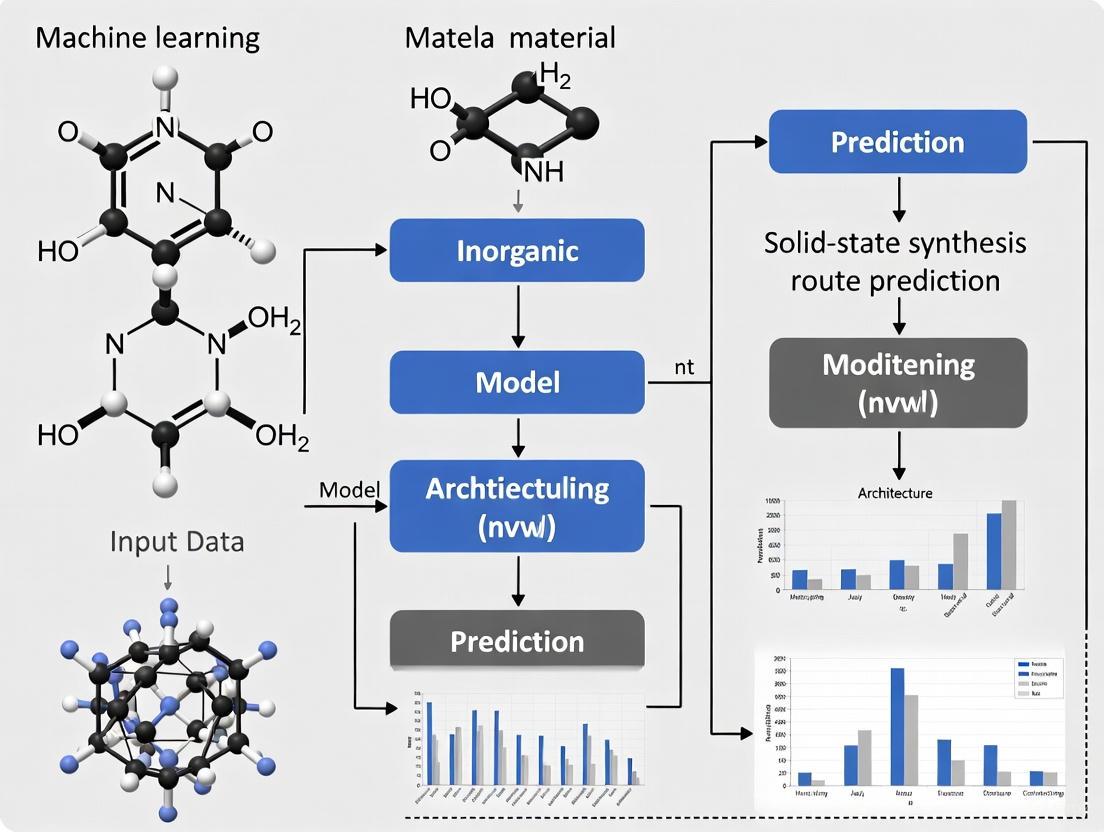

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting and planning solid-state synthesis routes, a critical bottleneck in materials discovery.

Machine Learning for Solid-State Synthesis: Predicting Routes and Accelerating Materials Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting and planning solid-state synthesis routes, a critical bottleneck in materials discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview from foundational concepts to advanced applications. We cover the core challenges in traditional synthesis methods and the fundamental principles of applying ML to this domain. The article delves into specific methodologies like positive-unlabeled learning and the use of text-mined and human-curated datasets for training predictive models. It further addresses practical aspects of model debugging, optimization, and handling data limitations. Finally, we present the critical frameworks for validating and benchmarking ML models against traditional computational methods like DFT, evaluating their real-world efficacy in prospective materials discovery campaigns. This guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to leverage ML for developing novel materials, including those with potential biomedical applications.

The Synthesis Bottleneck and AI Foundations in Materials Science

In the pursuit of novel materials for pharmaceuticals, energy storage, and electronics, solid-state synthesis serves as a fundamental method for creating crystalline inorganic compounds, including many active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and functional materials. Unlike solution-phase reactions where molecules freely diffuse and interact, solid-state reactions occur between solid reactants, presenting a unique set of challenges. The core challenge, and the primary reason this method is often a rate-limiting step in materials discovery and development, lies in its inherent dependence on solid-state diffusion. This process is notoriously slow and energy-intensive, often requiring days or even weeks of continuous high-temperature treatment to reach completion [1]. This bottleneck severely constrains the rapid experimental validation of promising candidate materials identified through high-throughput computational screenings, creating a significant pacing issue in fields like drug development where speed-to-market is critical [2].

The transition towards data-driven research, including the application of machine learning (ML) for predicting synthesis routes, aims to overcome this barrier. However, the effectiveness of ML is heavily dependent on the quality and quantity of reliable synthesis data [2]. This application note details the fundamental reasons behind the rate-limiting nature of solid-state synthesis, provides quantitative data on the associated challenges, outlines standard and emerging experimental protocols, and discusses how machine learning is being leveraged to predict synthesizability and optimize reactions, thereby accelerating the entire materials development pipeline for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Fundamental Rate-Limiting Step: Solid-State Diffusion

In solid-state synthesis, reactant molecules are fixed in a constrained, relatively stable conformation within their crystal lattices. Based on topochemical theory, these reactions typically progress through four distinct stages, as illustrated in Figure 1.

- Stage 1 (Nucleation): Crystal defects, deformations, and molecular "looseness" are initiated within one or several crystal nuclei.

- Stage 2 (Bond Breaking/Forming): Old chemical bonds break and new bonds form under the applied conditions (e.g., heat, light).

- Stage 3 (Solid Solution Formation): A small amount of the product forms a solid solution within the original crystal matrix.

- Stage 4 (Crystallization & Separation): The product crystallizes and separates from the reactant matrix [1].

The rate-limiting step in this sequence is universally recognized as the diffusion of atoms, molecules, or ions through the crystalline phases of the reactant, intermediate, and product [1]. This process is inherently slow because it requires constituent species to overcome significant energy barriers to move through rigid, tightly packed crystal structures, rather than mixing freely as in a liquid solvent.

Quantitative Energy and Time Requirements

The following table summarizes the typical resource demands for conventional solid-state synthesis, highlighting its intensive nature.

Table 1: Characteristic Parameters of Conventional Solid-State Synthesis

| Parameter | Typical Requirement or Characteristic | Impact on Process |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Duration | Days to weeks [1] | Drastically extends discovery timelines. |

| Energy Input | High-temperature treatment, often prolonged [1] | High energy consumption and cost. |

| Process Acceleration | Grinding, milling, ultrasonic irradiation, high-temperature melting [1] | Introduces mechanochemistry, which may not be desirable for all products. |

| Synthesizability Proxy | Energy above convex hull (E$__{hull}$) | Not a sufficient condition; ignores kinetics and reaction conditions [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Solid-State Synthesis

This section provides a detailed methodology for a standard solid-state reaction and an advanced, light-driven alternative that directly addresses the diffusion bottleneck.

Protocol 1: Conventional High-Temperature Solid-State Synthesis

This is a foundational method for synthesizing ternary oxides and other inorganic compounds.

- 1. Precursor Preparation: Weigh out solid powdered precursors (typically metal carbonates or oxides) in the desired stoichiometric ratios. For a typical reaction, 1-5 grams of total product mass is common for lab-scale synthesis.

- 2. Mixing and Grinding: Combine the powders in an agate mortar and pestle or a mechanical mill (e.g., a ball mill). Grind for 30-60 minutes to achieve a homogeneous, finely powdered mixture. This step increases surface contact and reduces diffusion pathways.

- 3. Pelletization (Optional): The mixed powder may be pressed into a pellet using a hydraulic press at pressures of 1-5 tons. This improves inter-particle contact but can also reduce surface area for gas-solid reactions.

- 4. Calcination: Place the powder or pellet in a suitable crucible (e.g., alumina, platinum) and transfer it to a high-temperature furnace.

- Heating Profile: Heat the sample to a target temperature (often 800-1500 °C, depending on the material) at a controlled ramp rate (e.g., 3-5 °C/min).

- Atmosphere: Maintain the reaction in a controlled atmosphere (air, oxygen, nitrogen, or argon) for several hours to days.

- Intermediate Grinding: After the first heating cycle, the sample is often cooled, reground to expose fresh surfaces and mitigate the diffusion barrier, and then reheated. This cycle may be repeated multiple times to ensure complete reaction.

- 5. Cooling and Product Characterization: After the final heating cycle, cool the product to room temperature, either naturally in the furnace (annealed cooling) or by being removed and quenched. The final product is characterized by techniques such as X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm phase purity [2].

Protocol 2: Photoactivated Solid-State Synthesis of Aromatic Amines

This emerging protocol leverages light to overcome the diffusion barrier under mild conditions, representing a significant advance in green chemistry. The workflow is depicted in Figure 2.

1. Catalyst Preparation (12R-Pd-NCs):

- Synthesis: Reduce Pd species bonded to laurylbenzene (e.g., dodecylbenzene) via a homogeneous reduction method using sodium borohydride. This creates palladium nanoclusters (12R-Pd-NCs) with a monolayer organic capping via [Pd-C(sp²)] bonds, characterized by strong lipophilicity and high flexibility [1].

- Characterization: Confirm the asymmetric defect structure of the nanoclusters, which enhances visible light absorption, using techniques like Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and UV-Vis spectroscopy.

2. Reaction Setup:

- Reactants: Use solid nitroarene substrates (e.g., nitrobenzene).

- Mixing: Combine the solid nitroarene substrate with a small quantity of the 12R-Pd-NCs catalyst (e.g., 75 mg catalyst per 15 g substrate) without any solvent or mechanical grinding.

- Conditions: Transfer the solid mixture to a suitable reactor. Purge the system and maintain a hydrogen atmosphere (1 atm H₂) at ambient temperature (25 °C) [1].

3. Photoactivation and Reaction:

- Light Source: Irradiate the reaction vessel with a natural light source (≥100 W) to trigger Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) in the 12R-Pd-NCs.

- Mechanism: The SPR effect induces directional adsorption of solid nitroarenes and facilitates spontaneous, ultrafast electron transfer through a "photon-induced electron tunneling-proton-coupled interface" mechanism. This bypasses the need for thermal diffusion.

- Monitoring: The reaction proceeds spontaneously without external force. Monitor completion by the disappearance of the nitroarene starting material, typically via Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) or Gas Chromatography (GC).

4. Product Isolation and Analysis:

- Isolation: The product (aromatic amine) is obtained directly from the reaction vessel. The catalyst can be recovered and reused for multiple cycles.

- Analysis: Determine yield and chemical selectivity (typically >99% for both) using GC-MS or NMR spectroscopy [1].

Figure 2: Workflow for photoactivated solid-state synthesis, showing how light energy bypasses traditional diffusion limits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Advanced Solid-State Synthesis

| Research Reagent | Function / Role in Overcoming Rate-Limiting Step |

|---|---|

| Plasmonic Nanoclusters (e.g., 12R-Pd-NCs) | Acts as a photocatalyst; absorbs light to generate energetic electrons that drive reactions at room temperature, bypassing thermal diffusion [1]. |

| Solid Powdered Precursors (Oxides, Carbonates) | Primary reactants. Finely ground and mixed to minimize diffusion path length. |

| High-Temperature Furnace | Provides the thermal energy required to overcome kinetic barriers and facilitate solid-state diffusion in conventional synthesis. |

| Controlled Atmosphere (O₂, N₂, H₂) | Prevents unwanted side reactions (e.g., oxidation/reduction) and can be a key reactant in certain solid-state syntheses. |

| Ball Mill / Mechanical Grinder | Applies mechanochemical force to mix reactants, create crystal defects, and reduce particle size, thereby accelerating diffusion. |

Integrating Machine Learning for Prediction and Acceleration

The slow and resource-intensive nature of solid-state synthesis creates a perfect use case for machine learning. A primary application is in synthesizability prediction, which helps prioritize candidate materials likely to be realized in the lab.

Data-Driven Synthesizability Prediction

A major challenge is the lack of negative data (failed attempts) in the literature. Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning, a semi-supervised ML technique, is used to address this. In one study, a human-curated dataset of 4,103 ternary oxides was used to train a PU learning model. The model was tasked with predicting which hypothetical compositions from a large database (like the Materials Project) are likely to be synthesizable via solid-state reactions. This approach successfully identified 134 promising compositions out of 4,312, providing a powerful pre-screening tool that minimizes futile lab experimentation [2].

Key ML-Generated Features and Metrics

ML models rely on specific input features to make predictions. The most common proxy for thermodynamic stability is the Energy Above Hull (E$_{hull}$). However, as highlighted in Table 3, E$_{hull}$ is an insufficient predictor on its own, as it does not account for kinetic barriers or synthesis conditions [2]. ML models therefore incorporate a wider range of features, from composition-based descriptors to text-mined synthesis parameters, to build more accurate predictors.

Table 3: Key Metrics for Predicting Solid-State Synthesizability

| Metric/Feature | Description | Utility and Limitation in Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Above Hull (E$__{hull}$) | Thermodynamic stability metric; energy difference from the most stable decomposition products. | Common first filter; low E$__{hull}$ is necessary but not sufficient for synthesizability [2]. |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Parameters | Data on heating temperature, time, precursors, etc., extracted from literature using NLP. | Provides real-world context; but dataset quality is variable (e.g., one dataset had 51% overall accuracy) [2]. |

| Human-Curated Synthesis Data | Manually extracted, high-quality data from scientific papers, including synthesis route and conditions. | High reliability but time-consuming to produce; ideal for training robust ML models [2]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning | ML approach that learns from confirmed positive examples (synthesized materials) and unlabeled data. | Mitigates the critical lack of reported failed experiments, enabling practical synthesizability classification [2]. |

The title "The Core Challenge: Why Solid-State Synthesis is a Rate-Limiting Step" is fundamentally anchored in the immutable physical reality of solid-state diffusion. This process dictates the slow kinetics and high energy demands that create a major bottleneck in materials development cycles. While conventional methods rely on brute-force application of heat and mechanical energy to overcome this barrier, innovative approaches like photoactivated catalysis are demonstrating that the underlying kinetics can be dramatically altered.

The integration of machine learning offers a transformative path forward. By leveraging high-quality data and techniques like PU learning, ML models can predict solid-state synthesizability with increasing accuracy, guiding researchers to invest resources in the most promising candidate materials. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these emerging protocols and data-driven tools is essential for de-risking the solid-state synthesis process, accelerating discovery timelines, and ultimately bringing new materials and pharmaceuticals to market more efficiently.

The pursuit of new functional materials, from high-temperature superconductors to advanced battery components, relies fundamentally on our ability to synthesize predicted compounds. For decades, computational materials science has leaned heavily on thermodynamic stability metrics, particularly the Energy Above Hull (Ehull), to predict synthesizability. This metric, derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations, indicates a compound's thermodynamic stability relative to competing phases on the convex hull formation energy diagram [3]. Materials with Ehull = 0 meV/atom are considered thermodynamically stable, while those with positive values are metastable or unstable [4] [3].

However, the persistent materials synthesis bottleneck – where computationally predicted materials with favorable properties fail experimental realization – exposes critical limitations in relying solely on thermodynamic metrics. Synthesis is a kinetic process governed by complex reaction pathways, precursor selection, and processing conditions that thermodynamics alone cannot capture [5] [6]. This application note examines the fundamental limitations of E_hull as a standalone synthesizability predictor and presents emerging machine learning frameworks that integrate broader contextual factors to bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental synthesis.

Fundamental Limitations of the Energy Above Hull Metric

Thermodynamic Ground State Assumption

The Ehull metric operates on the fundamental principle of thermodynamic equilibrium at 0 K, where phases lying on the convex hull are stable and those above it are unstable. While theoretically sound, this approach ignores the reality of metastable materials synthesis. Many technologically crucial materials – including photovoltaics, structural alloys, and specific polymorphs – are metastable under ambient conditions but remain synthesizable through kinetic control [5] [6]. For instance, BaTaNO2 oxynitride, calculated to be 32 meV/atom above hull, represents a real example of a metastable phase that can be synthesized despite its positive Ehull value [4].

Kinetic and Pathway Blindness

The most significant limitation of E_hull is its inability to account for kinetic barriers and reaction pathways that dictate actual synthesis outcomes:

- Inert Byproducts: Highly stable intermediate phases can form during reactions, consuming the thermodynamic driving force and preventing target material formation regardless of the target's final E_hull value [5].

- Precursor Dependency: Experimental synthesis outcomes vary dramatically based on precursor selection, a factor completely absent from Ehull calculations [5]. A target material may form from one precursor set while failing from another, despite identical final composition and Ehull.

- Synthesis Conditions: Temperature, time, atmosphere, and heating rates critically influence which phases form, yet these parameters are unrepresented in the E_hull metric [5].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Energy Above Hull Metric

| Limitation Category | Specific Deficiency | Impact on Synthesis Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Scope | Assumes 0 K equilibrium | Overlooks metastable phases that are synthetically accessible |

| Kinetic Blindness | Ignores reaction activation barriers | Cannot predict kinetic trapping or formation of inert intermediates |

| Pathway Ignorance | Independent of precursor selection | Fails to predict which precursor combinations will successfully yield target |

| Condition Insensitivity | Unaffected by temperature, pressure, atmosphere | Cannot guide experimental parameter optimization |

| Time Independence | Contains no temporal component | Cannot predict phase evolution or transformation sequences |

False Positives and Negatives in Synthesis Prediction

The E_hull metric generates both false positives (materials predicted synthesizable that are not) and false negatives (materials predicted unsynthesizable that are):

- False Positives: Compounds with E_hull = 0 may remain unsynthesizable due to kinetic competition from other phases or the lack of a viable synthesis pathway [4] [6].

- False Negatives: Materials with E_hull > 0 (metastable) may be successfully synthesized through low-temperature routes or precursor selections that bypass thermodynamic bottlenecks [5].

Beyond E_hull: Machine Learning Approaches for Synthesis Route Prediction

Network Analysis and Synthesizability Prediction

Novel approaches analyze the materials stability network – the complex web of tie-lines connecting stable phases on the convex hull – to extract synthesizability insights beyond simple Ehull values. This network exhibits scale-free topology with hub materials (e.g., O2, Cu, H2O) playing disproportionately important roles in synthesis [6]. By tracking the historical evolution of this network and applying machine learning to network properties (degree centrality, eigenvector centrality, clustering coefficient), researchers have developed models that predict synthesis likelihood with greater accuracy than Ehull alone [6].

Network-Based Synthesis Prediction

Active Learning and Precursor Optimization: The ARROWS3 Framework

The ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization for Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm represents a paradigm shift from static thermodynamic prediction to dynamic, experimentally-guided optimization [5]. This framework integrates initial DFT-based precursor ranking with active learning from experimental outcomes to avoid intermediates that consume thermodynamic driving force.

ARROWS3 Active Learning Workflow

Quantitative Comparison: E_hull vs. Advanced ML Approaches

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Synthesis Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Basis of Prediction | Experimental Iterations Needed | Precursor Selection Guidance | Metastable Phase Handling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E_hull Alone | Thermodynamic stability at 0 K | High (No guidance) | None | Poor (False negatives) |

| Network Analysis | Historical discovery patterns & connectivity | Moderate (Prioritized candidate list) | Indirect (via similar materials) | Moderate (Historical precedent) |

| ARROWS3 Framework | Active learning from failed experiments | Low (Adapts from outcomes) | Direct (Optimizes selection) | High (Kinetic pathway control) |

| Bayesian Optimization | Black-box parameter optimization | Moderate to High | Limited (Parameter tuning) | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis Route Prediction

Protocol: ARROWS3-Guided Synthesis Optimization

Purpose: To systematically identify optimal precursor combinations for target materials through active learning from experimental outcomes.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-purity precursor powders

- Automated powder mixing system

- Programmable furnace with controlled atmosphere

- X-ray diffractometer (XRD)

- Machine learning-enabled phase analysis software

Procedure:

- Precursor Set Generation: Enumerate all stoichiometrically balanced precursor combinations for target composition.

- Initial Ranking: Calculate thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) for each precursor set using DFT-computed energies.

- First Experimental Iteration:

- Select top-ranked precursor sets for testing

- Mix powders and heat at multiple temperature plateaus (e.g., 600°C, 700°C, 800°C, 900°C)

- Perform XRD analysis after each temperature step

- Identify intermediate phases using ML-based phase analysis

- Pairwise Reaction Analysis:

- Determine which pairwise reactions led to observed intermediates

- Calculate remaining driving force (ΔG') after intermediate formation

- Updated Ranking:

- Re-rank precursor sets based on predicted ΔG' values

- Prioritize sets that avoid high-driving-force-consuming intermediates

- Subsequent Iterations:

- Test newly top-ranked precursor sets

- Repeat steps 3-5 until target forms with sufficient purity or all sets exhausted

Validation: This protocol was successfully validated on YBa2Cu3O6.5 (188 experiments), Na2Te3Mo3O16 (46 experiments), and LiTiOPO4 (120 experiments), identifying all effective synthesis routes with fewer iterations than black-box optimization methods [5].

Protocol: Network-Based Synthesis Likelihood Assessment

Purpose: To predict synthesizability of hypothetical materials using network centrality metrics.

Materials and Equipment:

- Access to materials database (e.g., Materials Project, OQMD)

- Network analysis software (e.g., NetworkX)

- Machine learning environment (e.g., Python/scikit-learn)

Procedure:

- Network Construction:

- Build materials stability network from convex hull data

- Include all stable materials and connecting tie-lines

- Feature Calculation:

- Compute degree centrality for target material

- Calculate eigenvector centrality

- Determine mean shortest path length to known materials

- Compute clustering coefficient in local composition space

- Model Application:

- Input network features into pre-trained synthesizability classifier

- Obtain synthesis likelihood score (0-1 scale)

- Experimental Prioritization:

- Rank hypothetical materials by synthesis likelihood

- Prioritize high-likelihood candidates for experimental testing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesis Prediction Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursor Powders | Starting materials for solid-state reactions | Y2O3, BaCO3, CuO for YBCO synthesis [5] |

| DFT-Computed Formation Energies | Thermodynamic reference data | Initial precursor ranking in ARROWS3 [5] |

| XRD Reference Patterns | Phase identification standards | ICDD database for intermediate phase detection [5] |

| Machine Learning-Enabled Phase Analysis Software | Automated interpretation of diffraction data | Rapid identification of reaction intermediates [5] |

| Materials Network Database | Historical synthesis data source | Training synthesizability prediction models [6] |

The limitations of Energy Above Hull as a standalone synthesizability metric underscore a fundamental truth: materials synthesis is a multidimensional challenge that cannot be captured by thermodynamics alone. The emerging paradigm integrates thermodynamic calculation with kinetic pathway analysis, historical data mining, and active learning from experimental failures to create more accurate synthesis prediction frameworks.

Future advancements will likely focus on multi-fidelity prediction that combines high-throughput computation with real-time experimental feedback, ultimately enabling fully autonomous materials synthesis platforms. For researchers in solid-state chemistry and drug development, embracing these integrated approaches promises to significantly accelerate the translation of computationally predicted materials into functional realities.

How AI is Reshaping the Materials Discovery Pipeline

The discovery and synthesis of new solid-state materials are undergoing a revolutionary transformation through the integration of artificial intelligence. Traditional materials discovery has been constrained by time-consuming trial-and-error approaches and the computational expense of high-throughput screening methods. AI, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning, is now reshaping this entire pipeline—from initial material design and property prediction to synthesis planning and experimental validation [7]. This paradigm shift is especially impactful for solid-state synthesis route prediction, where AI models are learning the complex relationships between composition, structure, and synthesizability that have traditionally required extensive human expertise [8] [2].

The integration of AI addresses fundamental challenges in materials science: the vast combinatorial space of possible materials, the resource intensity of density functional theory (DFT) calculations, and the critical gap between computational predictions and experimental realization [9] [10]. By leveraging diverse data sources—from scientific literature to experimental results—AI systems can now accelerate the discovery of materials with tailored properties while predicting viable synthesis pathways [11].

AI Methodologies for Materials Discovery

Machine Learning Approaches and Their Applications

Table 1: AI Methodologies in Materials Discovery and Their Specific Applications

| AI Methodology | Primary Function | Applications in Solid-State Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | Inverse materials design | Proposing novel crystal structures with desired properties [7] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Structure-property prediction | Estimating material stability and functional properties [9] |

| Gaussian Processes | Learning expert intuition | Translating experimental knowledge into quantitative descriptors [8] |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning | Synthesizability prediction | Identifying synthesizable materials from limited positive data [2] |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Synthesis route prediction | Predicting synthetic methods and precursors from text representations [12] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Experimental design | Optimizing materials recipes and reaction conditions [11] |

| Universal Interatomic Potentials | Stability screening | Pre-screening thermodynamically stable hypothetical materials [9] |

Specialized Frameworks and Tools

Several specialized AI frameworks have been developed to address specific challenges in materials discovery. The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework translates human expertise into quantitative descriptors by training on curated, measurement-based data [8]. This approach has successfully reproduced established expert rules for identifying topological semimetals while revealing new chemical descriptors.

For experimental optimization, the Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists (CRESt) platform incorporates information from diverse sources including scientific literature, chemical compositions, and microstructural images to optimize materials recipes and plan experiments [11]. This system uses robotic equipment for high-throughput testing, with results fed back into models for continuous improvement.

In generative materials design, SCIGEN (Structural Constraint Integration in GENerative model) enables popular diffusion models to create materials following specific geometric design rules [13]. This is particularly valuable for quantum materials where certain atomic structures (like Kagome lattices) are associated with exotic properties.

AI for Synthesis Route Prediction and Synthesizability Assessment

Predicting Solid-State Synthesizability

A critical bottleneck in materials discovery is predicting which computationally designed materials can be successfully synthesized. Traditional approaches relying on thermodynamic stability metrics like energy above hull (Ehull) have limitations, as many metastable materials are synthesizable while some thermodynamically favorable structures are not [2]. AI approaches are now addressing this challenge through various innovative methods:

Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning has shown particular promise for predicting solid-state synthesizability from limited data. Chung et al. applied PU learning to a human-curated dataset of 4,103 ternary oxides, extracting synthesis information from literature including whether materials were synthesized via solid-state reaction and associated reaction conditions [2]. Their model successfully identified synthesizable compositions while highlighting limitations in text-mined datasets.

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a breakthrough in synthesizability prediction, achieving 98.6% accuracy in predicting whether arbitrary 3D crystal structures can be synthesized [12]. This system utilizes three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, possible synthetic methods, and suitable precursors respectively, significantly outperforming traditional thermodynamic and kinetic stability assessments.

Quantitative Performance of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods and Their Performance

| Prediction Method | Accuracy | Dataset Size | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework [12] | 98.6% | 150,120 structures | Predicts methods and precursors; handles complex structures | Requires balanced training data |

| Traditional Ehull Screening [12] | 74.1% | N/A | Physically intuitive; widely available | Misses metastable phases; poor synthesizability proxy |

| Phonon Stability [12] | 82.2% | N/A | Assesses kinetic stability | Computationally expensive; false negatives |

| PU Learning [2] | >87.9% | 4,103 oxides | Works with limited negative data; human-curated features | Limited to studied compositions |

| Teacher-Student Dual Network [12] | 92.9% | Varies by application | Improved generalization | Architecture complexity |

Experimental Protocol: Predicting Solid-State Synthesizability Using PU Learning

Purpose: To predict the synthesizability of novel ternary oxides via solid-state reactions using positive-unlabeled learning when only limited positive data is available.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Curated dataset of known synthesized materials (positive examples)

- Large pool of unlabeled candidate materials

- Features: compositional descriptors, structural parameters, thermodynamic properties

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Manually extract solid-state synthesis information from literature for a focused materials class (e.g., ternary oxides). For each entry, record:

- Successful synthesis via solid-state reaction (positive label)

- Highest heating temperature, atmosphere, precursors, number of heating steps

- Non-solid-state synthesized or undetermined materials (separate categories) [2]

Feature Engineering: Calculate or extract relevant features including:

Model Training:

- Implement PU learning algorithm (e.g., tree-based classifiers)

- Use known synthesized materials as positive examples

- Treat materials without confirmed synthesis as unlabeled

- Apply bagging approach to reduce false positives [2]

Validation:

Prospective Prediction:

- Apply trained model to hypothetical materials

- Prioritize candidates with high synthesizability scores for experimental testing

- Refine model with experimental feedback

Workflow Visualization: AI-Driven Materials Discovery Pipeline

Diagram 1: AI-driven materials discovery workflow. The pipeline shows the integrated approach from initial design to discovery, highlighting key AI components and their interactions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | DiffCSP, GNoME | Propose novel crystal structures with target properties [13] [10] |

| Synthesizability Predictors | CSLLM, PU Learning Models | Assess likelihood of successful experimental synthesis [12] [2] |

| Precursor Recommenders | Precursor LLM (from CSLLM) | Identify suitable solid-state synthesis precursors [12] |

| Stability Screeners | Universal Interatomic Potentials (UIPs) | Pre-screen thermodynamic stability of hypothetical materials [9] |

| Experimental Platforms | CRESt, Autonomous Labs | Execute robotic synthesis and characterization [11] |

| Benchmarking Tools | Matbench Discovery | Standardized evaluation of ML model performance [9] |

| Data Resources | ICSD, Materials Project | Provide training data and ground truth for AI models [8] [2] |

| Text Mining Tools | NLP pipelines | Extract synthesis parameters from scientific literature [2] |

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Case Study: Discovering Fuel Cell Catalysts with CRESt

The CRESt platform was applied to develop electrode materials for direct formate fuel cells, demonstrating a complete AI-driven discovery cycle:

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective Identification: Target was to find multielement catalysts with reduced precious metal content while maintaining high power density [11].

AI-Guided Exploration:

- CRESt explored over 900 chemistries using active learning

- Incorporated literature knowledge and experimental feedback

- Used robotic systems for high-throughput synthesis and testing

- Performed 3,500 electrochemical tests over three months [11]

Results: Discovery of an eight-element catalyst delivering:

- 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar over pure palladium

- Record power density with one-fourth the precious metals of previous devices [11]

This case study demonstrates how AI systems can efficiently navigate complex multidimensional search spaces that would be prohibitive for traditional approaches.

Case Study: Predicting and Synthesizing Quantum Materials with SCIGEN

The SCIGEN framework was applied to generate materials with specific geometric patterns (Archimedean lattices) associated with quantum properties:

Experimental Protocol:

- Constraint Definition: Applied structural constraints for Archimedean lattices known to host exotic quantum phenomena [13].

AI Generation and Screening:

- Generated over 10 million material candidates with target lattices

- Screened for stability, resulting in ~1 million candidates

- Performed detailed simulations on 26,000 materials using Oak Ridge National Laboratory supercomputers

- Identified magnetism in 41% of simulated structures [13]

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesized two previously undiscovered compounds (TiPdBi and TiPbSb)

- Confirmed AI-predicted properties aligned with actual material behavior [13]

This approach demonstrates how AI can be steered to discover materials with specific target properties rather than simply optimizing for stability.

Implementation Framework and Benchmarking

Evaluation Framework for ML Models in Materials Discovery

The Matbench Discovery framework addresses critical challenges in evaluating AI models for materials discovery:

Key Evaluation Principles:

- Prospective Benchmarking: Using test data generated through the intended discovery workflow rather than artificial splits [9]

- Relevant Targets: Focusing on thermodynamic stability (distance to convex hull) rather than formation energy alone [9]

- Informative Metrics: Emphasizing classification performance near decision boundaries rather than regression accuracy [9]

- Scalability Assessment: Testing models on problems where the test set exceeds the training set [9]

Performance Insights: Universal interatomic potentials (UIPs) currently outperform other methodologies including random forests, graph neural networks, and Bayesian optimizers for stability prediction [9]. This highlights the importance of physics-informed models alongside purely data-driven approaches.

Workflow Visualization: Synthesizability-Driven Crystal Structure Prediction

Diagram 2: Synthesizability-driven crystal structure prediction. This specialized workflow integrates symmetry guidance with ML synthesizability assessment to bridge computational prediction and experimental realization.

AI is fundamentally reshaping the materials discovery pipeline by creating an integrated, data-driven ecosystem that connects computational design with experimental synthesis. The frameworks and methodologies discussed—from synthesizability prediction using PU learning and LLMs to autonomous experimental platforms—demonstrate a paradigm shift toward more efficient, targeted materials discovery.

Future advancements will likely focus on improving model generalizability across diverse material classes, developing standardized data formats for synthesis information, and creating more sophisticated autonomous laboratories. The integration of AI throughout the entire materials discovery workflow promises to accelerate the development of novel materials for applications ranging from energy storage to quantum computing, ultimately bridging the critical gap between computational prediction and experimental realization.

The field of materials science is undergoing a significant transformation driven by machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and generative models. These technologies are revolutionizing the prediction of material properties, the discovery of novel compounds, and the optimization of material structures, thereby accelerating scientific progress beyond the capabilities of traditional experimental and computational methods [14]. The traditional Edisonian approach to materials discovery is characteristically slow, often relying on trial-and-error or serendipity [15] [16]. In contrast, data-driven methods leverage large-scale datasets from experiments, simulations, and open materials databases to uncover complex relationships between chemical composition, microstructure, and functional properties [14] [15]. This paradigm shift is crucial for developing next-generation functional materials for applications in energy, electronics, and nanotechnology, and is particularly relevant for addressing the urgent bottleneck of predictive synthesis in the computational materials discovery pipeline [17].

Table 1: Core Machine Learning Paradigms in Materials Science

| Learning Type | Primary Objective | Common Algorithms | Example Materials Science Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Find a function that maps known inputs to known outputs [15]. | Decision Trees, Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks [14]. | Predicting material properties (e.g., bandgap, formation energy) from composition or crystal structure [14] [15]. |

| Unsupervised Learning | Find hidden patterns or structures in unlabeled data [15]. | Clustering (e.g., K-means), Dimensionality Reduction (e.g., PCA) [14]. | Identifying novel material classes or grouping similar synthesis pathways from text-mined data [17]. |

| Generative Modeling | Learn the underlying distribution of data to generate new, similar data points [16]. | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [14] [16]. | Inverse design of new, theoretically stable crystal structures with targeted properties [16]. |

Key Concepts and Algorithms

Fundamental Machine Learning and Deep Learning

Machine learning provides a collection of statistical methods that optimize task performance using examples or past experience [15]. A critical challenge in materials informatics is the choice and construction of descriptors—numerical representations that encode a material's key features, such as its composition, crystal structure, or physicochemical attributes [15] [16]. Deep learning, a subset of ML based on deep neural networks, offers a powerful advantage by automatically learning relevant features and representations directly from raw or minimally processed data, bypassing the need for manual feature engineering [14] [15]. For instance, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting properties of complex crystalline structures by directly modeling the atomic bonding relationships within a material [14].

Generative Models for Inverse Design

Generative models represent a frontier in AI-driven materials discovery. Unlike traditional models that predict properties for a given structure, generative models perform inverse design: they generate new material structures based on a set of desired properties [18] [16]. The two most prominent architectures are:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): These consist of an encoder that compresses a material representation into a lower-dimensional latent space, and a decoder that reconstructs the material from this space. By strategically sampling and manipulating points in the latent space, VAEs can generate novel and valid material designs [16].

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): This framework involves two competing neural networks—a generator that creates new material structures and a discriminator that evaluates their authenticity against real data. This competition drives the generator to produce increasingly realistic candidates [14] [16].

A significant challenge for inorganic materials is the complexity of structure representation compared to organic molecules, making the "fingerprinting" for inverse design considerably more difficult [16].

Application Notes for Solid-State Synthesis Route Prediction

The application of these AI/ML techniques to predict solid-state synthesis routes is an active and challenging area of research. The core objective is to move beyond thermodynamic stability predictions (e.g., from density functional theory) and provide actionable guidance on precursor selection, reaction temperatures, and heating times [17].

Workflow for a Data-Driven Synthesis Prediction Project

The following diagram illustrates a generalized protocol for building an ML model to predict synthesis routes.

Protocol 1: Building a Dataset via Text-Mining of Synthesis Literature

This protocol outlines the process of creating a structured dataset from unstructured scientific text, a foundational step for training synthesis prediction models [17].

Objective: To extract and structure solid-state synthesis recipes from published literature into a machine-readable format. Materials and Data Sources:

- Full-text scientific papers (post-2000, in HTML/XML format) from publishers like Springer, Wiley, Elsevier, RSC, etc. [17].

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) Libraries: SpaCy, NLTK, or specialized transformers.

- Computational Resources: Standard workstation or computational cluster.

Procedure:

- Literature Procurement: Secure permissions and download full-text articles from participating publishers [17].

- Identify Synthesis Paragraphs: Scan papers to locate paragraphs describing experimental synthesis procedures. Use a probabilistic model based on the presence of keywords commonly associated with inorganic synthesis (e.g., "calcined," "sintered," "precursor") [17].

- Extract Targets and Precursors: Replace all chemical compounds with a general

<MAT>token. Use a neural network model (e.g., a Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory with a Conditional Random Field layer, or BiLSTM-CRF) trained on manually annotated data to classify each<MAT>token as a target material, a precursor, or another reaction component (e.g., atmosphere, solvent) based on sentence context [17]. - Construct Synthesis Operations: Apply topic modeling techniques like Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to cluster synonyms of synthesis operations (e.g., 'fired', 'heated', 'annealed' all map to "heating"). Extract associated parameters (time, temperature, atmosphere) for each operation [17].

- Compile Recipes and Balance Reactions: Combine the extracted information into a structured JSON database. Attempt to balance the chemical reaction for the identified precursors and target, potentially including volatile gases, to enable calculation of reaction energetics using data from sources like the Materials Project [17].

Notes: This process is non-trivial and has a relatively low yield; one study reported that only 28% of identified solid-state synthesis paragraphs resulted in a balanced chemical reaction [17]. The resulting datasets often face challenges related to data veracity (accuracy of extraction) and variety (anthropogenic bias in how chemists report synthesis) [17].

Protocol 2: Inverse Design of a Novel Solid-State Material using a VAE

This protocol describes a generative approach for designing new, stable crystalline materials.

Objective: To generate a novel, theoretically stable inorganic crystal structure with a user-specified property (e.g., a target band gap) using a Variational Autoencoder. Materials and Software:

- Training Dataset: A large database of known crystal structures and their properties (e.g., Materials Project, AFLOW, OQMD) [14] [16].

- Representation: A suitable numerical representation for inorganic crystals, such as crystal graphs [16].

- Software Framework: Deep learning libraries like TensorFlow or PyTorch, and materials informatics toolkits.

- Validation Tool: Density Functional Theory (DFT) code for stability and property verification.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Representation: Select a dataset of stable crystalline structures from a materials database. Convert each crystal structure into a chosen representation that the VAE can process (e.g., a graph, a voxelated 3D image, or a simplified compositional descriptor) [16].

- Model Architecture Definition:

- Encoder: Design a neural network (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) that encodes the input crystal structure into a mean and variance vector, defining a probability distribution in the latent space.

- Sampler: Sample a point z from this distribution.

- Decoder: Design a network that takes the latent vector z and attempts to reconstruct the original crystal structure [16].

- Model Training: Train the VAE by minimizing a loss function that combines reconstruction loss (how well the output matches the input) and the Kullback-Leibler divergence (which regularizes the latent space to be continuous) [16].

- Latent Space Exploration and Generation: After training, sample random points from the latent space or interpolate between points corresponding to materials with desired traits. Decode these points to generate new crystal structures [16].

- Property Prediction and Filtering: Use a separate property prediction model (a "predictor") to screen the generated candidates for the target property. Alternatively, a conditional VAE can be trained to generate materials directly from a property label [16].

- Validation: Perform DFT calculations on the top candidate structures to verify their thermodynamic stability (e.g., energy above the convex hull) and predicted properties [16].

Notes: The main challenge is designing a model that can generate crystallographically valid and synthesizable structures. The "invertibility" of the structure representation is critical—it must be possible to decode the model's output back into a full crystal structure with atomic coordinates and lattice parameters [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key computational and data resources essential for research in ML-driven materials discovery.

Table 2: Essential Resources for ML-Driven Materials Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Solid-State Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [17] | Materials Database | Provides computed thermodynamic and electronic properties for a vast array of known and predicted inorganic crystals. | Source data for training property prediction models; used to calculate reaction energetics for text-mined recipes. |

| AutoGluon, TPOT, H2O.ai [14] | Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) | Automates the process of model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and feature engineering. | Accelerates the development of robust predictive models for synthesis parameters or material properties without deep ML expertise. |

| Text-mined Synthesis Dataset [17] | Curated Dataset | A collection of extracted synthesis recipes (precursors, targets, conditions) from scientific literature. | Serves as the primary training data for models aiming to predict synthesis routes for novel materials. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [14] | Machine Learning Algorithm | Deep learning models that operate directly on graph structures, ideal for representing crystal structures. | Used for highly accurate prediction of material properties and as encoders/decoders in generative models for materials. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [14] [16] | Generative Model | A framework for generating new data through an adversarial process between two neural networks. | Applied to inverse design of new material compositions and structures with targeted functional properties. |

| AI-Driven Robotic Laboratory [14] | Experimental System | Automated platforms that execute high-throughput synthesis and characterization based on ML-generated hypotheses. | Closes the loop in an autonomous discovery pipeline by providing rapid experimental validation of predicted materials. |

The effective application of ML requires high-quality, well-structured data. The tables below summarize key quantitative aspects of datasets and model performance in the field.

Table 3: Characteristics of a Text-Mined Synthesis Dataset [17]

| Metric | Value | Context / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-State Recipes Mined | 31,782 | Total number of solid-state synthesis recipes extracted from the literature. |

| Solution-Based Recipes Mined | 35,675 | Total number of solution-based synthesis recipes extracted. |

| Overall Extraction Yield | 28% | Percentage of identified synthesis paragraphs that successfully produced a balanced chemical reaction, highlighting data quality challenges. |

| Manually Annotated Paragraphs for Training | 834 | Human-annotated examples used to train the BiLSTM-CRF model for target/precursor identification. |

Table 4: Representative ML Tasks and Performance in Materials Science

| Prediction Task | Input Data Type | Typical ML Algorithm(s) | Reported Performance/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Property Prediction | Composition, Crystal Structure | Random Forests, GNNs [14] [15] | Enables rapid screening of vast chemical spaces, drastically reducing reliance on computationally expensive DFT calculations [14]. |

| Crystal Structure Generation | Latent Vector, Property Target | VAEs, GANs [16] | Demonstrated capability to propose novel, DFT-validated inorganic crystal structures, enabling inverse design [16]. |

| Synthesis Condition Prediction | Text-Mined Recipes, Target Composition | Regression/Classification Models [17] | Models capture historical trends but may offer limited utility for predicting synthesis of truly novel materials due to data biases [17]. |

| Reaction Outcome Prediction | Precursor Identities and Ratios | Bayesian Optimization [14] | Guides autonomous laboratories in optimizing synthesis conditions and discovering new synthetic pathways with minimal human intervention [14]. |

Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite the promising advances, several significant challenges remain in the application of ML to materials discovery, particularly for synthesis prediction.

- Data Quality and Availability: The "4 Vs" of data science—Volume, Variety, Veracity, and Velocity—are often not satisfied by text-mined synthesis datasets. Issues include extraction errors (veracity) and inherent biases in how and what chemists have chosen to synthesize and publish (variety) [17].

- Model Interpretability: Many powerful ML models, especially deep learning, operate as "black boxes." Gaining physical understanding and chemical insights from these models is difficult but essential for building trust and guiding scientific hypothesis generation [14] [15].

- Synthesizability: A major open challenge is bridging the gap between computationally designed materials and their actual synthesis. Predicting that a material is thermodynamically stable is different from predicting a viable kinetic pathway to make it [17].

- Integration with Experiments: The future lies in closing the loop between computation and experiment. This involves integrating ML models with AI-driven robotic laboratories and high-throughput computing to establish a fully automated pipeline for rapid synthesis and validation, drastically reducing the time and cost of discovery [14].

The integration of machine learning with traditional computational and experimental methods is creating hybrid models with enhanced predictive power. As algorithms, data resources, and automated platforms continue to mature, AI/ML is poised to become an indispensable part of materials research, ultimately leading to the efficient design of sustainable materials for the technologies of the future [14].

Data-Driven Methods and ML Models for Synthesizability Prediction

In the field of machine learning for solid-state synthesis route prediction, the adage "garbage in, garbage out" is particularly pertinent. The development of accurate and reliable models is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the training data. While computational advances have enabled the high-throughput generation of millions of hypothetical material candidates, the experimental validation of these materials represents a major bottleneck in the discovery pipeline. Data-driven approaches promise to predict synthesis pathways and assess synthesizability, but their performance is critically limited by the quality of the underlying data. This application note examines the central role of high-quality, curated datasets in advancing solid-state synthesis research, providing quantitative comparisons, detailed protocols, and essential tools for the research community.

The Data Quality Imperative: Quantitative Evidence

The materials science community has increasingly recognized that data quantity cannot compensate for poor data quality. The following evidence illustrates the significant performance gap between models trained on noisy, automated extracts versus carefully curated data.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Models Trained on Different Data Quality Levels

| Data Source / Model | Data Quality Approach | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text-mined solid-state dataset [2] | Automated extraction | Overall entry accuracy | 51% |

| Human-curated ternary oxides [2] | Manual expert curation | Outlier analysis accuracy | 15% (text-mined) vs. 100% (curated) |

| CAS Reactions + Bayer collaboration [19] | Scientist-curated enrichment | Prediction accuracy for rare reaction classes | Improved from 16% to 48% (+32 points) |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [12] | Domain-adapted fine-tuning | Synthesizability prediction accuracy | 98.6% |

| PU Learning on human-curated data [2] | Curated positive-unlabeled learning | Hypothetical compositions predicted synthesizable | 134/4312 |

The performance disparities revealed in Table 1 underscore a critical finding: even modestly-sized, high-quality datasets can dramatically outperform large, noisy datasets. In the Bayer-CAS collaboration, enriching training data with scientist-curated reactions improved prediction accuracy for rare reaction classes by 32 percentage points [19]. This demonstrates that data quality particularly impacts model performance in underrepresented chemical spaces where patterns are sparse.

Furthermore, a direct comparison between text-mined and human-curated data revealed significant quality issues. When analyzing 156 outliers from a text-mined dataset containing 4,800 entries, only 15% were correctly extracted, compared to 100% accuracy for the human-curated dataset [2]. These extraction errors include misassigned stoichiometries, omitted precursor references, and conflation of precursor and target species—issues that profoundly limit model generalizability.

Experimental Protocols for Data Curation and Utilization

Protocol: Manual Data Curation for Solid-State Synthesis Records

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating high-quality, human-curated datasets for solid-state synthesis, adapted from established approaches in the literature [2].

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Data Curation

| Item | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Project database | Source of candidate materials | Version 2020-09-08 or newer |

| ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) | Proxy for synthesized materials | Filter for entries with ICSD IDs |

| Scientific literature access | Primary data source | Web of Science, Google Scholar, publisher databases |

| Data organization system | Structured data storage | CSV, JSON, or database formats |

Stepwise Procedure

Candidate Identification: Download ternary oxide entries from the Materials Project database using pymatgen. Identify entries with ICSD IDs as an initial proxy for synthesized materials [2].

Composition Filtering: Remove entries containing non-metal elements and silicon to focus on relevant ternary oxide systems.

Literature Review: For each candidate composition:

- Examine papers corresponding to the ICSD IDs

- Search Web of Science with the chemical formula as input (review first 50 results sorted oldest to newest)

- Search Google Scholar with the chemical formula (review top 20 relevant results)

Data Extraction and Labeling:

- Solid-State Synthesized: Label if at least one record confirms synthesis via solid-state reaction

- Non-Solid-State Synthesized: Label if material synthesized but not via solid-state reactions

- Undetermined: Label if insufficient evidence exists, with reasons documented in comments

Reaction Condition Documentation: For confirmed solid-state syntheses, extract available details including:

- Highest heating temperature and pressure

- Atmosphere conditions

- Mixing/grinding methods

- Number of heating steps and cooling processes

- Precursors used

- Single-crystalline status of product

Data Validation: Randomly select 100 solid-state synthesized entries for independent verification by a second researcher to ensure labeling consistency and accuracy.

Protocol: Positive-Unlabeled Learning for Synthesizability Prediction

This protocol utilizes curated datasets to train models that can identify synthesizable materials from hypothetical candidates, addressing the critical lack of negative examples (failed syntheses) in literature [2] [12].

Materials and Software Requirements

- Python machine learning environment (scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch)

- Curated dataset of confirmed synthesized materials (positive examples)

- Hypothetical materials database (unlabeled examples)

- Feature descriptors (formation energy, structural fingerprints, elemental properties)

Stepwise Procedure

Data Preparation:

- Compile positive examples (P) from human-curated solid-state synthesized materials

- Compile unlabeled examples (U) from hypothetical materials in computational databases

- Compute feature descriptors for all materials

Model Training:

- Implement PU learning algorithm that treats unlabeled data as weighted negative examples

- Use bagging approaches with base classifiers to reduce variance

- Apply cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters

Prediction and Validation:

- Generate synthesizability scores for hypothetical compositions

- Select high-probability candidates for experimental validation

- Iteratively refine model with new experimental results

Visualization of Data Curation Workflows

Data Curation Workflow for Solid-State Synthesis

Table 3: Key Databases and Tools for Solid-State Synthesis Research

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [2] | Computational Database | High-throughput calculated materials properties | Public |

| ICSD [2] | Experimental Database | Experimentally determined crystal structures | Subscription |

| Kononova Text-Mined Dataset [20] | Text-Mined Dataset | Automatically extracted synthesis recipes | Public |

| CSLLM Framework [12] | AI Tool | Synthesizability prediction via fine-tuned LLMs | Research |

| CAS Reactions [19] | Curated Database | Scientist-curated reaction data | Subscription |

| Huo et al. Synthesis Dataset [21] | Text-Mined Dataset | Solid-state synthesis parameters | Public |

The advancement of machine learning for solid-state synthesis prediction hinges on the development and utilization of high-quality, curated datasets. Evidence consistently demonstrates that models trained on carefully curated data significantly outperform those trained on larger but noisier automated extracts. The protocols and resources outlined in this application note provide researchers with practical methodologies for building these essential data foundations. As the field progresses, the community must prioritize investments in data quality through expert curation, domain adaptation techniques, and robust validation processes—only then can we truly accelerate the journey from computational prediction to synthesized material.

The discovery of novel functional materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, yet the experimental validation of computationally predicted candidates remains a significant bottleneck. A central challenge in this process is accurately predicting solid-state synthesizability—whether a hypothetical compound can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory. Traditional proxies for synthesizability, such as thermodynamic stability (e.g., energy above the convex hull, or E hull), are insufficient alone, as they fail to account for kinetic barriers, entropic effects, and specific synthesis conditions [22] [2]. Furthermore, data-driven approaches are hamstrung by a fundamental lack of negative data; scientific literature almost exclusively reports successful syntheses, while failed attempts are rarely published [2] [23] [24].

Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning has emerged as a powerful semi-supervised machine learning framework to overcome this data scarcity. It enables the training of robust classification models using only known, synthesized materials (positive examples) and a large set of hypothetical compounds whose synthesizability status is unknown (unlabeled examples) [25] [23] [24]. This application note details the core principles, performance, and experimental protocols for applying PU learning to predict the synthesizability of solid-state materials, particularly within the context of a broader research thesis on machine learning for synthesis route prediction.

Performance of PU Learning Models

PU learning models have demonstrated superior performance in predicting synthesizability compared to traditional physical heuristics and stability metrics. The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of several recently developed models.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PU Learning Models for Synthesizability Prediction

| Model Name | Material Class | Key Methodology | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynCoTrain | Oxide Crystals | Co-training with two GCNNs (ALIGNN & SchNet) | High recall on internal and leave-out test sets [24] | |

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | General 3D Crystals | Fine-tuned Large Language Model | 98.6% accuracy; outperforms E hull (74.1%) and phonon stability (82.2%) [26] | |

| SynthNN | Inorganic Crystalline Materials | Deep learning on chemical compositions | 7x higher precision than DFT formation energies; outperformed human experts [23] | |

| Human-Curated Model | Ternary Oxides | PU learning on manually extracted literature data | Identified 134 likely synthesizable compositions out of 4312 hypotheticals [25] [2] | |

| Jang et al. Model | 3D Crystals (Materials Project) | PU Learning | Achieved 87.9% accuracy in synthesizability prediction [26] |

Experimental Protocols

This section outlines detailed methodologies for implementing a PU learning workflow for solid-state synthesizability prediction, based on established protocols from recent literature.

Protocol 1: Data Curation and Feature Engineering

Objective: To construct a high-quality dataset for training a PU learning model, specifically for ternary oxides [2].

Materials and Software:

- Source Databases: Materials Project API, Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Software Tools: Pymatgen for materials analysis.

- Search Engines: Web of Science, Google Scholar for manual literature validation.

Procedure:

- Initial Data Extraction:

- Download all ternary oxide entries from the Materials Project.

- Filter for entries possessing ICSD IDs, as an initial proxy for synthesized materials.

- Data Refinement:

- Remove entries containing non-metal elements and silicon.

- This results in a candidate set (e.g., 4,103 ternary oxides).

- Manual Literature Curation:

- For each candidate composition, examine the scientific literature.

- Label as "Solid-State Synthesized" if at least one publication confirms synthesis via solid-state reaction. Record relevant details like heating temperature, atmosphere, and precursors.

- Label as "Non-Solid-State Synthesized" if the material was synthesized but not via a solid-state route.

- Label as "Undetermined" if there is insufficient evidence for classification.

- Feature Calculation:

- For all entries, compute compositional and structural features. These may include:

- Stoichiometric ratios.

- Elemental properties (e.g., electronegativity, atomic radius).

- Thermodynamic descriptors (e.g., energy above the convex hull, E hull).

- For all entries, compute compositional and structural features. These may include:

Protocol 2: Positive-Unlabeled Learning Model Training

Objective: To train a classifier that distinguishes synthesizable materials using only positive and unlabeled data [23] [24].

Materials and Software:

- Programming Language: Python.

- Machine Learning Libraries: Scikit-learn, PyTorch, or TensorFlow.

- Specialized Architectures: Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNNs) like ALIGNN or SchNet for structure-based models.

Procedure:

- Dataset Splitting:

- Split the human-curated dataset. All "Solid-State Synthesized" entries form the Positive (P) set.

- A large pool of hypothetical materials from sources like the Materials Project, which lack confirmed synthesis reports, is treated as the Unlabeled (U) set. This set is assumed to contain a mix of synthesizable and unsynthesizable materials.

- Model Selection and Training:

- Choose a Base Classifier: Select a suitable algorithm (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, or a Neural Network).

- Apply PU Learning Strategy: Implement an algorithm such as the "bagging" approach by Mordelet and Vert [24].

- Train an ensemble of classifiers.

- Each classifier is trained on a bootstrap sample of the positive data and a random subset of the unlabeled data.

- The final model aggregates predictions from the ensemble.

- Advanced Co-Training (SynCoTrain Framework):

- To reduce model bias, employ two different GCNNs (e.g., ALIGNN and SchNet) as base classifiers [24].

- Let each classifier predict labels for a portion of the unlabeled set.

- Iteratively exchange the most confident positive predictions between the classifiers to refine the training set for the next round.

- The final prediction is an average of the outputs from both models.

Protocol 3: Model Validation and Synthesizability Screening

Objective: To validate model performance and screen hypothetical material databases for synthesizable candidates.

Procedure:

- Validation:

- Hold out a portion of the human-curated positive data as a test set.

- Evaluate standard metrics like precision and recall on this test set. High recall ensures most known synthesizable materials are correctly identified.

- Screening:

- Deploy the trained model on a large database of hypothetical compositions (e.g., from high-throughput DFT calculations).

- The model outputs a synthesizability score or probability for each candidate.

- Rank candidates by this score and select the top-ranking materials for further experimental or computational study. For example, the model from Protocol 1 identified 134 high-priority ternary oxides for synthesis [2].

Workflow Visualization

The logical workflow for a PU Learning-based synthesizability prediction pipeline, incorporating the co-training framework, is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data "reagents" essential for building PU learning models for synthesizability prediction.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PU Learning in Synthesizability

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) | Data Source | Provides a comprehensive set of confirmed positive samples (synthesized materials) for model training. | [26] [23] |

| Materials Project / OQMD | Data Source | Provides a large source of unlabeled data (hypothetical materials with computed properties) and stability metrics (E hull). | [22] [2] [24] |

| Pymatgen | Software Library | A Python library for materials analysis used for parsing crystal structures, calculating features, and managing data. | [2] [24] |

| ALIGNN | Model Architecture | A Graph Neural Network that incorporates atomic bond and angle information, providing a "chemist's perspective" on crystal structures. | [24] |

| SchNet | Model Architecture | A Graph Neural Network using continuous-filter convolutional layers, providing a "physicist's perspective" on atomic systems. | [24] |

| PU Bagging Algorithm | Algorithm | The core PU learning method that enables training on positive and unlabeled data by aggregating multiple weak classifiers. | [23] [24] |

The acceleration of materials discovery, particularly in the domain of solid-state synthesis, is currently hampered by a critical bottleneck: the experimental validation of computationally predicted candidate materials. While high-throughput calculations can generate millions of promising candidates, their synthesis often remains a process guided by trial-and-error and expert intuition [2] [26]. A vast reservoir of synthesis knowledge exists within the published scientific literature; however, this information is predominantly in unstructured text format, making it inaccessible to large-scale computational analysis. Natural Language Processing (NLP) has emerged as a transformative technology to bridge this gap, turning unstructured text into structured, actionable knowledge. When framed within a broader thesis on machine learning for solid-state synthesis route prediction, NLP serves as the foundational step that enables data-driven approaches to synthesizability prediction, precursor recommendation, and reaction condition optimization. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for applying NLP to scientific literature, with a specific focus on supporting research in solid-state synthesis route prediction.

NLP Approaches and Workflow for Materials Science

Natural Language Processing is a subfield of artificial intelligence that enables computers to understand and process human language [27]. Its application in materials science typically follows a structured pipeline, from text preprocessing to feature extraction and model training.

Core NLP Techniques and Tasks

The following table summarizes key NLP techniques and their relevance to materials science applications:

Table 1: Key NLP Techniques and Their Applications in Materials Science

| NLP Technique | Description | Application in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|

| Named Entity Recognition (NER) | Identifies and classifies key entities (e.g., material names, properties) in text [27]. | Extracting material formulas, synthesis conditions, and precursors from literature [28]. |

| Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging | Labels words with their corresponding parts of speech (noun, verb, etc.) [27]. | Aiding in the parsing of complex synthesis descriptions and action sequences. |

| Dependency Parsing | Analyzes grammatical relationships between words in a sentence [27]. | Understanding the relationship between synthesis actions and parameters (e.g., "heat at 1000°C"). |

| Word Sense Disambiguation | Determines the correct meaning of words with multiple meanings [27]. | Differentiating between a material's "phase" and a research "phase". |

| Text Classification | Categorizes entire documents or paragraphs into predefined classes [29]. | Identifying papers relevant to solid-state synthesis or classifying synthesis methods. |

The NLP Pipeline for Synthesis Information Extraction

The process of extracting synthesis knowledge from text can be systematized into a standard workflow. The following diagram illustrates the key stages from data collection to model application.

Experimental Protocols for NLP in Synthesis Prediction

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments and processes in building an NLP pipeline for solid-state synthesis prediction.

Protocol: Manual Data Curation for Model Training and Validation

Objective: To create a high-quality, human-curated dataset of solid-state synthesis parameters from scientific literature for training and validating NLP models.

Materials and Reagents:

- Literature Sources: Access to the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Data Storage System: A structured database (e.g., SQL, CSV) for recorded data.

Procedure:

- Candidate Identification: Download a set of candidate material entries from computational databases (e.g., Materials Project). Filter for entries with associated ICSD IDs as an initial proxy for synthesized materials [2].

- Literature Search: For each candidate material, perform a systematic literature search:

- Examine papers associated with the ICSD ID.

- Query Web of Science with the chemical formula, reviewing the first 50 results sorted from oldest to newest.

- Query Google Scholar with the chemical formula, reviewing the top 20 most relevant results [2].

- Data Extraction and Labeling: For each relevant article, extract the following information into the database:

- Synthesizability Label: Determine if the material was synthesized via a solid-state reaction. Label as "solid-state synthesized," "non-solid-state synthesized," or "undetermined" if evidence is insufficient [2].

- Reaction Conditions: If solid-state synthesized, record:

- Highest heating temperature (°C)

- Atmosphere (e.g., air, O₂, Ar)

- Number of heating steps and dwell times

- Mixing/grinding method (e.g., mortar and pestle, ball milling)

- Cooling process (e.g., furnace cooling, quenching)

- Precursor materials [2].

- Product Characterization: Note if the final product was single-crystalline or polycrystalline.

- Data Validation: Perform random checks on a subset of the curated data (e.g., 100 entries) to ensure labeling accuracy and consistency [2].

Protocol: Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning for Synthesizability Prediction

Objective: To train a machine learning model to predict the solid-state synthesizability of hypothetical materials, addressing the challenge of lacking negative data (failed syntheses) in the literature.