Machine Learning for Predictive Materials Synthesis: From Data to Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in accelerating the prediction and synthesis of novel materials, a critical bottleneck in fields from drug development to renewable energy.

Machine Learning for Predictive Materials Synthesis: From Data to Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in accelerating the prediction and synthesis of novel materials, a critical bottleneck in fields from drug development to renewable energy. It examines the foundational shift from trial-and-error methods to data-driven design, detailing key ML algorithms and their application in predicting material properties and optimizing synthesis pathways. The content addresses central challenges, including data quality and model generalizability, while evaluating the efficacy of different ML approaches through comparative analysis and validation techniques like autonomous laboratories. Finally, it synthesizes key takeaways and discusses future implications for creating a tightly-coupled, AI-driven discovery pipeline in biomedical and clinical research.

The New Paradigm: How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Materials Discovery

The Bottleneck of Traditional Materials Synthesis

The discovery of novel functional materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, from next-generation batteries to sustainable cement. For decades, high-throughput computational methods have matured to the point where researchers can rapidly screen thousands of hypothetical materials for desirable properties using first-principles calculations [1]. However, a critical bottleneck has emerged in the materials discovery pipeline: predicting how to synthesize these computationally designed materials in the laboratory [1] [2]. While computational tools can identify promising materials with targeted properties, they provide minimal guidance on practical synthesis—selecting appropriate precursors, determining optimal reaction temperatures and times, or choosing suitable synthesis routes [1]. This gap between computational prediction and experimental realization represents the most significant impediment to accelerated materials discovery.

The synthesis bottleneck is particularly pronounced because materials synthesis remains largely guided by empirical knowledge and trial-and-error approaches [2]. Traditional methods rely heavily on researcher intuition and documented precedents, which are often limited in scope and accessibility. As the chemical space of potential materials continues to expand with complex multi-component systems, the conventional approach becomes increasingly inadequate [3]. The problem is further exacerbated by the metastable nature of many advanced materials, where subtle variations in synthesis parameters can lead to dramatically different outcomes [2]. This challenge has stimulated urgent interest in developing machine learning (ML) approaches for predictive materials synthesis, leveraging the vast but underutilized knowledge embedded in the scientific literature and experimental data [1] [2].

Quantifying the Bottleneck: Data Limitations in Materials Synthesis

The Volume and Veracity Challenge

The materials science literature contains millions of published synthesis procedures, which would appear to provide a robust foundation for training machine learning models. However, when researchers text-mined synthesis recipes from the literature, significant limitations emerged in both volume and data quality that fundamentally constrain predictive capabilities.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Text-Mined Synthesis Data Limitations

| Metric | Solid-State Synthesis | Solution-Based Synthesis | Overall Extraction Yield | Data Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracted Recipes | 31,782 recipes [1] | 35,675 recipes [1] | 28% of classified paragraphs [1] | Only 30% of random samples contained complete information [1] |

| Literature Source | 4,204,170 papers scanned [1] | 4,204,170 papers scanned [1] | 15144 solid-state paragraphs with balanced reactions [1] | Manual annotation of 834 paragraphs for training [1] |

| Classification Basis | 53,538 paragraphs classified as solid-state synthesis [1] | 188,198 total inorganic synthesis paragraphs [1] | 6,218,136 total experimental paragraphs scanned [1] | 100-paragraph sample validation set [1] |

The data reveals critical limitations in both dataset size and quality. The overall extraction pipeline yield of 28% indicates that nearly three-quarters of potentially valuable synthesis information is lost during text mining due to technical challenges in parsing and interpretation [1]. Even when recipes are successfully extracted, a manual assessment revealed that only 30% of randomly sampled paragraphs contained complete synthesis information, highlighting significant veracity issues [1]. These limitations stem from both technical challenges in natural language processing and fundamental issues in how synthesis information is reported in the literature, including inconsistent terminology, ambiguous material representations, and incomplete procedural descriptions [1].

Variety and Velocity Constraints

Beyond volume and veracity, the available synthesis data suffers from significant limitations in variety and velocity—two additional dimensions critical for robust machine learning. The scientific literature exhibits substantial anthropogenic bias, reflecting how chemists have historically explored materials space rather than providing comprehensive coverage of possible synthesis approaches [1]. This bias manifests in the overrepresentation of certain material classes, precursor types, and synthesis conditions, while other regions of chemical space remain sparsely populated in the data.

The velocity dimension—referring to the flow of new data—presents another constraint. The pace at which new synthesis knowledge is generated and incorporated into databases lags significantly behind computational materials design cycles [1]. While high-throughput computations can screen thousands of hypothetical materials in days, experimental validation and publication of synthesis recipes occurs on much longer timescales. This velocity mismatch further exacerbates the synthesis bottleneck, as ML models trained on historical data may lack information about novel material classes identified through computational screening.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Data Extraction and Analysis

Natural Language Processing Pipeline for Synthesis Information

Overcoming the synthesis bottleneck requires extracting structured synthesis data from unstructured scientific literature. Between 2016-2019, researchers developed a sophisticated natural language processing pipeline to text-mine synthesis recipes, which involved multiple technically complex steps [1]:

Full-Text Literature Procurement: The pipeline began with obtaining full-text permissions from major scientific publishers (Springer, Wiley, Elsevier, RSC, etc.), enabling large-scale downloads of publication texts. Only papers with HTML/XML formats published after 2000 were selected, as older PDF formats proved difficult to parse reliably [1].

Synthesis Paragraph Identification: To identify which paragraphs contained synthesis procedures, researchers implemented a probabilistic assignment based on keyword frequency. The system scanned paragraphs for terms commonly associated with inorganic materials synthesis, then classified them accordingly [1]. From 6,218,136 total experimental paragraphs scanned, 188,198 were identified as describing inorganic synthesis [1].

Target and Precursor Extraction: Using a bi-directional long short-term memory neural network with a conditional random field layer (BiLSTM-CRF), the system replaced all chemical compounds with <MAT> tags and used sentence context clues to label targets, precursors, and other reaction components [1]. This model was trained on 834 manually annotated solid-state synthesis paragraphs [1].

Synthesis Operation Classification: Through latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), the system clustered synonyms into topics corresponding to specific synthesis operations (mixing, heating, drying, shaping, quenching) [1]. This approach identified relevant parameters (times, temperatures, atmospheres) associated with each operation type [1].

Recipe Compilation and Reaction Balancing: Finally, all extracted information was combined into a JSON database with balanced chemical reactions, including volatile atmospheric gasses where necessary to maintain stoichiometry [1].

Case Study: Zeolite Synthesis Modeling

The application of this data extraction pipeline to zeolite synthesis demonstrates both the challenges and opportunities in predictive synthesis. Zeolites are crystalline, microporous aluminosilicates with applications in catalysis, carbon capture, and water decontamination [2]. Their synthesis is particularly challenging due to metastability and complex kinetics, where minor condition changes significantly impact final structure [2].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Zeolite Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis | Extraction Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Sources | Sodium aluminate, aluminum hydroxide | Provides framework aluminum atoms | Multiple chemical names and formulations |

| Silicon Sources | Sodium silicate, tetraethyl orthosilicate | Provides framework silicon atoms | Abbreviations and commercial naming variations |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Tetraalkyl ammonium cations | Templates specific pore architectures | Proprietary formulations and inconsistent reporting |

| Mineralizing Agents | Sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide | Controls solution pH and silicate speciation | Concentration variations and measurement inconsistencies |

| Reaction Medium | Water, mixed solvents | Provides reaction environment | Incomplete specification of solvent systems |

Using random forest regression on the extracted zeolite synthesis data, researchers demonstrated the ability to model the connection between synthesis conditions and resulting zeolite structure [2]. The tree models provided interpretable pathways for synthesizing low-density zeolites, offering guidance beyond conventional trial-and-error approaches [2]. This case study illustrates how data-driven methods can begin to address the synthesis bottleneck even for complex material systems with sensitive formation kinetics.

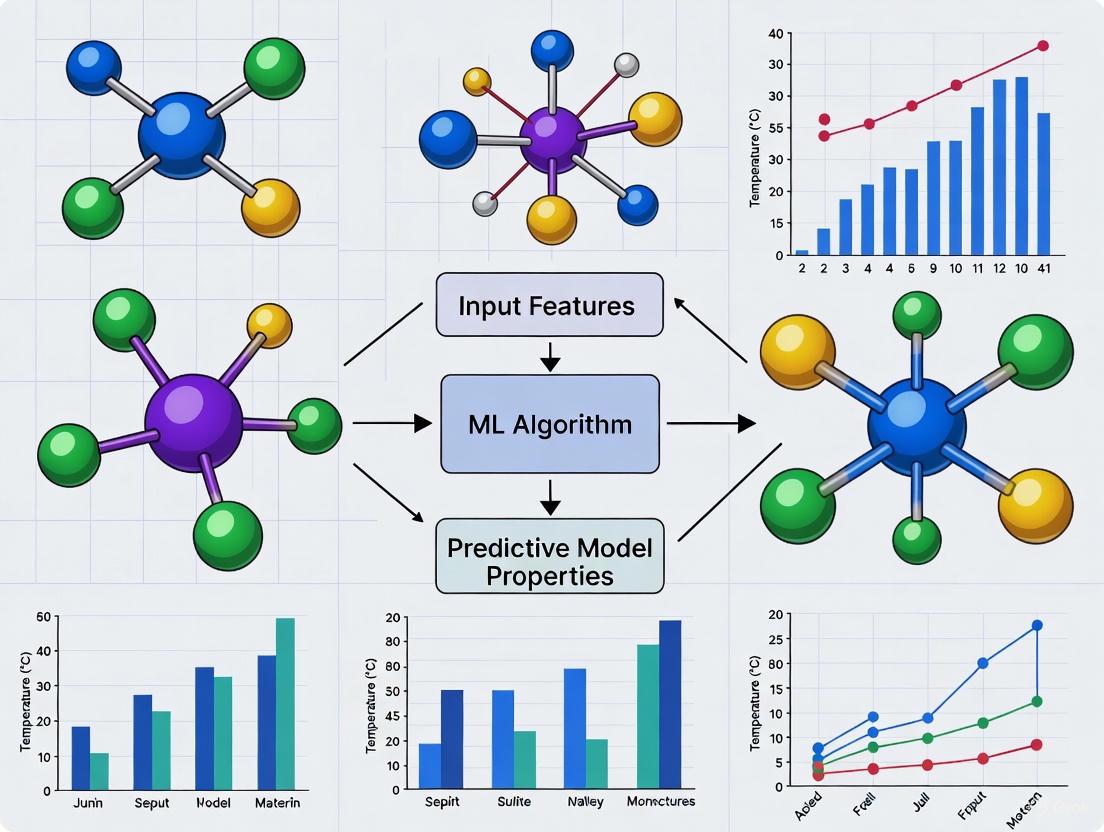

Diagram 1: Zeolite Synthesis and ML Prediction Workflow (86 characters)

Machine Learning Approaches to Overcome Synthesis Bottlenecks

From Text Mining to Predictive Models

The transformation of text-mined synthesis data into predictive ML models represents the cutting edge of materials informatics. Current approaches leverage diverse algorithmic strategies to extract meaningful patterns from historical synthesis data:

Foundation Models for Materials Discovery: Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) and foundation models show promise for materials synthesis prediction [4]. These models, pre-trained on broad scientific corpora, can be adapted to downstream tasks such as predicting synthesis conditions for novel materials [4]. The separation of representation learning from specific prediction tasks enables more efficient use of limited synthesis data [4].

Anomaly Detection for Hypothesis Generation: Interestingly, the most valuable insights from text-mined synthesis data often come not from common patterns but from anomalous recipes that defy conventional intuition [1]. Manual examination of these outliers has led to new mechanistic hypotheses about solid-state reactions, which were subsequently validated experimentally [1]. This suggests that ML approaches should prioritize not only common patterns but also strategically important anomalies.

Multi-Modal Data Integration: Advanced ML pipelines now integrate multiple data modalities—text, tables, images, and molecular structures—to construct comprehensive synthesis datasets [4]. Specialized algorithms extract data from spectroscopy plots, convert visual representations to structured data, and process Markush structures from patents [4]. This multi-modal approach significantly expands the usable data for training synthesis models.

Emerging Solutions and Dataset Developments

The research community has responded to synthesis data limitations by developing specialized datasets and models:

MatSyn25 Dataset: A recently introduced large-scale open dataset specifically addresses the need for structured synthesis information for two-dimensional (2D) materials [5]. MatSyn25 contains 163,240 pieces of synthesis process information extracted from 85,160 research articles, providing basic material information and detailed synthesis steps [5]. This specialized resource enables more targeted development of synthesis prediction models for the strategically important 2D materials class.

Autonomous Experimental Systems: ML-driven robotic platforms represent another approach to overcoming synthesis bottlenecks by generating high-quality, standardized synthesis data through autonomous experimentation [3]. These systems can conduct experiments, analyze results, and optimize processes with minimal human intervention, simultaneously accelerating discovery and creating rich datasets for model training [3].

Diagram 2: ML Pipeline for Synthesis Prediction (76 characters)

Table 3: Machine Learning Solutions for Synthesis Bottlenecks

| ML Approach | Application in Synthesis | Advantages | Current Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest Regression | Zeolite structure prediction [2] | Interpretable pathways, handles mixed data types | Limited extrapolation beyond training data |

| Foundation Models | Cross-domain synthesis planning [4] | Transfer learning, minimal fine-tuning needed | Requires massive computational resources |

| Graph Neural Networks | Crystal structure prediction [3] | Captures spatial relationships | Limited 3D structural data availability |

| Generative Models | Inverse design of synthesis routes [3] | Creates novel synthesis pathways | Challenge in validating proposed routes |

| Autonomous Laboratories | Real-time synthesis optimization [3] | Generates standardized high-quality data | High initial infrastructure investment |

The bottleneck of traditional materials synthesis represents a critical challenge at the intersection of computational materials design and experimental realization. While computational methods can rapidly identify promising hypothetical materials, transitioning these predictions to synthesized materials remains slow and resource-intensive. The limitations of available synthesis data—in volume, variety, veracity, and velocity—fundamentally constrain the development of robust predictive models. However, emerging approaches in natural language processing, machine learning, and autonomous experimentation offer promising pathways forward. By leveraging text-mined historical data, detecting scientifically valuable anomalies, generating new standardized datasets through autonomous labs, and developing specialized foundation models, the research community is building the necessary infrastructure to overcome the synthesis bottleneck. As these approaches mature, they will ultimately enable the closed-loop materials discovery pipeline, where computational prediction and experimental synthesis operate in tandem to accelerate the development of novel functional materials.

The application of machine learning (ML) to materials science represents a fundamental shift from traditional trial-and-error experimentation to a data-driven, predictive discipline. In predictive materials synthesis research, ML serves as a powerful accelerator, learning complex relationships between material compositions, synthesis parameters, and resulting properties. This paradigm enables researchers to navigate the vast chemical space more efficiently, identifying promising candidates for advanced applications in drug development, energy storage, and electronics before undertaking costly physical experiments. The core principle underpinning this transformation is representation learning—where models automatically discover the meaningful features and patterns from raw materials data that are most relevant for prediction tasks [4].

Foundation models, trained on broad data that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks, are particularly transformative. These models decouple the data-hungry task of representation learning from target-specific prediction tasks. Philosophically, this approach harks back to an era of expert-designed features but uses an "oracle" trained on phenomenal volumes of data, enabling powerful predictions with minimal additional task-specific training [4]. For materials researchers, this means a single base model can be fine-tuned for diverse applications—from predicting novel stable crystals to planning synthesis routes for organic molecules.

Core Learning Paradigms in Materials Informatics

Machine learning approaches materials data through several distinct learning paradigms, each with specific mechanisms for extracting knowledge from experimental and computational data sources.

Supervised Learning for Property Prediction

Supervised learning operates on labeled datasets where each material is associated with specific target properties. This paradigm dominates property prediction tasks, where models learn the functional relationship between material representations (e.g., chemical formulas, crystal structures) and properties of interest (e.g., band gap, catalytic activity, toxicity). The model's training objective is to minimize the difference between its predictions and known experimental or computational values. For example, models can be trained to predict formation energies of crystalline compounds from their structural descriptors, enabling high-throughput screening of potentially stable materials from large databases [6] [4].

The predictive capability heavily depends on data representation. While early approaches relied on hand-crafted features (descriptors), modern foundation models learn representations directly from fundamental representations such as SMILES strings, crystal graphs, or elemental compositions. Current literature is dominated by models trained on 2D molecular representations, though this omits critical 3D conformational information. The scarcity of large-scale 3D structure datasets remains a limitation, though inorganic crystals more commonly leverage 3D structural information through graph-based representations [4].

Unsupervised and Self-Supervised Learning for Pattern Discovery

Unsupervised learning identifies hidden patterns and structures in unlabeled materials data. In materials discovery, this paradigm is particularly valuable for clustering similar materials, dimensionality reduction, and anomaly detection. Self-supervised learning—a variant where models generate their own labels from the data structure—enables pretraining on vast unlabeled corpora of scientific literature and databases. For instance, models can be trained to predict masked portions of SMILES strings or atomic coordinates, thereby learning fundamental chemical rules and relationships without explicit property labels [4].

This approach is crucial for addressing the data scarcity problem in materials science. By pretraining on large unlabeled datasets (e.g., from PubChem, ZINC, or ChEMBL), models learn transferable representations of chemical space that can be fine-tuned for specific property prediction tasks with limited labeled examples. Encoder-only models based on architectures like BERT have shown particular promise for this purpose [4].

Multimodal Learning for Heterogeneous Data

Materials information exists in diverse formats—textual descriptions in research articles, numerical property data, molecular structures, synthesis protocols, and characterization images. Multimodal learning integrates these disparate data types into unified representations. For example, advanced data extraction systems combine text parsing with computer vision to identify molecular structures from patent images and associate them with properties described in the text [4].

Vision Transformers and Graph Neural Networks can identify molecular structures from images in scientific documents, while language models extract contextual information from accompanying text. This multimodal approach is essential for constructing comprehensive datasets that capture the complexity of materials science knowledge, particularly for synthesis planning where procedural details are often described narratively and illustrated schematically [4].

Current Frontiers: Specialized Models and Datasets

The field of ML for materials discovery is rapidly evolving, with specialized models and datasets emerging to address specific challenges in predictive synthesis.

Table 1: Key Foundation Model Architectures for Materials Discovery

| Model Type | Architecture | Primary Materials Applications | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | BERT-based models | Property prediction, materials classification | Generates meaningful representations for regression/classification tasks [4] |

| Decoder-Only | GPT-based models | Molecular generation, synthesis planning | Autoregressive generation of novel structures and synthesis pathways [4] |

| Encoder-Decoder | T5-based models | Cross-modal tasks, reaction prediction | Translates between different representations (e.g., text to SMILES) [4] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Message-passing networks | Crystal property prediction, molecular modeling | Naturally handles non-Euclidean data like atomic structures [4] |

Table 2: Notable Materials Datasets for Training ML Models

| Dataset | Scale | Data Modality | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatSyn25 | 163,240 synthesis processes from 85,160 articles | Textual synthesis procedures with material information | Training models for synthesis reliability prediction [5] |

| AlphaFold Database | >200 million protein structures | 3D protein structures | Biological materials design, drug development [7] |

| GNoME | 400,000 predicted new substances | Crystal structures | Discovery of novel stable materials [7] |

| PubChem/ZINC/ChEMBL | ~109 molecules each | 2D molecular structures (SMILES) | General-purpose molecular foundation models [4] |

Specialized models are emerging for distinct challenges. AlphaGenome aims to decipher non-coding DNA functions, while materials discovery models like GNoME predict novel stable crystals. The end goal is an era where "AI can basically design any material with any sort of magical property that you want, if it is possible" [7]. These models increasingly employ a "security-first" design with responsibility committees conducting thorough reviews of potential misuse scenarios, particularly important for materials with dual-use potential [8] [7].

Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

Implementing ML for materials discovery follows a structured experimental workflow that integrates data curation, model training, validation, and experimental verification.

Data Extraction and Curation Protocols

The foundation of effective ML is quality data. Automated extraction pipelines process heterogeneous sources:

- Text Mining: Named Entity Recognition (NER) models identify material names, properties, and synthesis conditions from scientific literature [4].

- Image Processing: Vision Transformers and specialized algorithms like Plot2Spectra extract data from spectroscopy plots and molecular structures in documents [4].

- Multimodal Fusion: Advanced pipelines combine textual and visual information, crucial for interpreting complex representations like Markush structures in patents that define key intellectual property [4].

Data quality challenges include inconsistent naming conventions, ambiguous property descriptions, and noisy or incomplete information. Robust curation must address these issues through normalization and validation steps, often leveraging schema-based extraction with modern LLMs for improved accuracy [4].

Model Training and Validation Framework

Training materials foundation models follows a multi-stage process:

- Pretraining: Self-supervised learning on large unlabeled datasets (e.g., using masked language modeling for SMILES strings or atomic coordinates) to learn fundamental chemical principles [4].

- Fine-tuning: Supervised training on labeled datasets for specific property prediction tasks, leveraging transfer learning from the pretrained model [4].

- Alignment: Conditioning model outputs to meet scientific constraints (e.g., chemical validity, synthesizability) through reinforcement learning or constrained sampling [4].

Validation requires rigorous benchmarking on held-out test sets with domain-relevant metrics. For generative tasks, this includes assessing synthetic accessibility and structural diversity. For predictive tasks, performance is measured against experimental data or high-fidelity simulations. Cross-validation strategies must account for data splits that evaluate generalization to novel chemical spaces rather than random splits that may leak information [4].

Experimental Verification Loop

Predictions require experimental validation to establish real-world relevance:

- High-Confidence Prediction Selection: Identifying candidates with the highest predicted performance and synthetic accessibility.

- Synthesis Planning: Using models like MatSyn AI to propose viable synthesis routes for predicted materials [5].

- Physical Characterization: Measuring actual properties of synthesized materials to validate predictions and identify discrepancies.

- Model Refinement: Incorporating experimental results as additional training data to improve model accuracy iteratively.

This closed-loop approach accelerates the discovery cycle while generating valuable data to address distributional gaps in training datasets.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Materials Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation Models | GNoME, AlphaFold, MatSyn AI | Predict material properties, structures, and synthesis pathways [5] [7] [4] |

| Data Resources | MatSyn25, PubChem, AlphaFold Database | Provide structured datasets for training and benchmarking ML models [5] [7] [4] |

| ML Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Develop, train, and deploy custom ML models for materials applications [6] |

| Analysis Libraries | Pandas, NumPy, Scikit-learn | Perform data manipulation, numerical computations, and traditional ML [9] [6] |

| Deployment Tools | Flask, FastAPI, Docker | Containerize and serve trained models as web services for broader use [6] |

| Specialized Hardware | GPUs, TPUs | Accelerate training of computationally intensive deep learning models [8] |

| Benchmarking Platforms | AI4Mat Workshop Challenges | Standardized evaluation of ML methods on meaningful materials tasks [10] |

Visualizing ML Workflows for Materials Discovery

The following diagrams illustrate key workflows and relationships in ML-driven materials discovery.

Diagram 1: Foundation Model Workflow for Materials Discovery

Diagram 2: Multimodal Data Processing for Materials Science

Machine learning represents a paradigm shift in materials discovery, moving from serendipitous experimentation to targeted, predictive design. The core principle enabling this transformation is representation learning—where models automatically extract meaningful patterns from complex materials data. As foundation models continue to evolve and incorporate diverse data modalities, they offer the promise of accelerating the discovery and development of novel materials for addressing critical challenges in drug development, energy storage, and sustainable technology. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core ML principles is no longer optional but essential for leveraging the full potential of computational-guided materials design.

Key Machine Learning Algorithms for Materials Science (CNNs, GNNs, etc.)

The discovery and development of new materials are fundamental to technological progress, from energy storage to aerospace. Traditional methods, reliant on trial-and-error or computationally expensive simulations, often act as a bottleneck in research. The emergence of machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing this paradigm, offering powerful tools for predicting material properties, designing novel structures, and accelerating synthesis. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core machine learning algorithms—including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and transformer-based foundation models—that are reshaping predictive materials synthesis research. By framing these algorithms within the context of a broader thesis on ML for materials research, we aim to equip scientists and engineers with the knowledge to leverage these tools for groundbreaking discoveries.

Core Machine Learning Algorithms and Architectures

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Concept and Principle: CNNs are a class of deep neural networks specifically designed to process data with a grid-like topology, such as images or, in the context of materials science, spatial data representing microstructures. Their architecture is built around convolutional layers that apply filters across the input to detect local patterns and hierarchical features, making them highly effective for tasks involving spatial relationships [11].

Key Applications in Materials Science:

- Microstructure-Property Linkage: CNNs serve as efficient surrogates for physics-based models. For instance, a 3D CNN can be trained on finite element (FE) simulation data to rapidly predict the bulk elastic properties (e.g., elastic moduli, Poisson's ratios) of complex material systems like carbon nanotube (CNT) bundle microstructures, bypassing the need for computationally expensive FE analyses in the design phase [11].

- Interpretation of Mechanical Tests: CNNs can translate data from non-destructive, small-sample testing methods into standard material properties. A recent study demonstrated that a 1D CNN could be trained on paired experimental data from Small Punch Tests (SPT) and Uniaxial Tensile Tests (UTT) to predict UTT-equivalent stress-strain curves for boiler steels, effectively reducing the systematic bias inherent to the SPT method [12].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Concept and Principle: GNNs incorporate a natural inductive bias for representing a collection of atoms. In a graph representation, atoms are treated as nodes, and the chemical bonds between them are treated as edges. GNNs perform a sequence of message-passing operations (or graph convolutions), where information is exchanged and updated between connected nodes. This allows the model to learn a rich representation of the material's structure that is invariant to translation, rotation, and permutation of atoms [13] [14].

Key Applications and Libraries:

- Universal Property Prediction: GNNs are a foundational technology for predicting a wide array of material properties directly from atomic structure. Architectures like the Materials Graph Network (MEGNet) and Materials 3-body Graph Network (M3GNet) have been successfully applied to predict properties such as formation energies, band gaps, and elastic moduli [13].

- Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIP): GNNs form the backbone of modern MLIPs, which parameterize potential energy surfaces to enable highly accurate, large-scale atomistic simulations at a fraction of the computational cost of methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT). The rise of foundation potentials (FPs)—universal MLIPs trained on a vast spectrum of the periodic table—is a direct result of GNNs' ability to handle diverse chemistries [13].

- The Materials Graph Library (MatGL): This open-source library, built on the Deep Graph Library (DGL) and Pymatgen, provides a unified and extensible platform for developing GNN models in materials science. It offers implementations of state-of-the-art models like M3GNet, MEGNet, and CHGNet, along with pre-trained models and potentials for out-of-the-box usage [13].

Generative Models and Reinforcement Learning

Concept and Principle: While discriminative models learn ( p(y|x) ) (the probability of a property given a structure), generative models learn ( p(x) ) (the probability distribution of structures themselves). This enables the inverse design of new materials. Reinforcement Learning (RL) further enhances this by fine-tuning generative models to optimize for specific, often conflicting, target properties.

Key Applications:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for Data Augmentation: In scenarios with sparse experimental data, VAEs can learn a compressed, latent representation of a material (e.g., based on composition and crystal structure) and generate synthetic, credible data points. This approach has been used to expand a dataset of 234 ferroelectric ceramic samples to 20,000 data points, significantly improving the predictive accuracy for remanent polarization [15].

- Reinforcement Learning for Property Optimization: RL can be used to fine-tune generative models using rewards from discriminative models. For example, CrystalFormer-RL is an autoregressive transformer model for crystal generation that was fine-tuned using RL. The reward signal was provided by MLIPs and property prediction models, guiding the generator to produce crystals with enhanced stability and desirable properties, such as a high dielectric constant and a large band gap simultaneously [16].

Transformer-Based Foundation Models

Concept and Principle: Inspired by large language models, transformer-based foundation models are trained on broad data (often using self-supervision) and can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks. They can process sequential representations of materials, such as text-based descriptors or simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings [4].

Key Applications:

- Flexible Property Prediction: Models like AlloyBert, built on the RoBERTa architecture, demonstrate that transformers can effectively predict alloy properties like elastic modulus and yield strength from simple English-language descriptors of composition and processing conditions. This offers a flexible alternative to models requiring rigid, structured input formats [17].

- Multimodal Data Extraction: Foundation models are being developed to extract materials information from the vast, unstructured scientific literature. They can parse text, tables, and images (e.g., molecular structures from patents) to build comprehensive materials databases, addressing a critical bottleneck in data curation [4].

Table 1: Summary of Core Machine Learning Algorithms in Materials Science

| Algorithm | Primary Function | Key Example | Reported Performance/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Mapping microstructure to properties; Curve-to-curve translation | Prediction of UTT curves from SPT data; Surrogate model for CNT bundle elastic properties | Reduced systematic bias of SPT; Accurate prediction of bulk moduli, bypassing FE analysis [12] [11] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Predicting properties from atomic structure; ML Interatomic Potentials | MatGL library (M3GNet, MEGNet); Foundation Potentials (FPs) | State-of-the-art accuracy for formation energy, band gaps; Enables large-scale, accurate atomistic simulations [13] |

| Generative Model (VAE/Disentangling AE) | Inverse design; Data augmentation; Unsupervised feature learning | Data augmentation for ferroelectric ceramics; Discovery of PV materials from spectra | Expanded dataset from 234 to 20,000 samples; Identified top PV candidates with 43% of search space [15] [18] |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Optimizing generative models for target properties | Fine-tuning of CrystalFormer generator (CrystalFormer-RL) | Generated crystals with high stability and conflicting properties (high dielectric constant & band gap) [16] |

| Transformer | Property prediction from text descriptors; Data extraction from literature | AlloyBert for predicting alloy properties | Flexible prediction of elastic modulus and yield strength from textual input [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CNN for SPT to UTT Curve Translation

This protocol outlines the methodology for using a Convolutional Neural Network to translate Small Punch Test data into equivalent Uniaxial Tensile Test curves, as demonstrated in recent research [12].

1. Objective: To train a 1D CNN model that reduces the systematic bias of the SPT and predicts UTT-equivalent force-displacement curves, from which yield strength and ultimate tensile strength can be extracted.

2. Materials and Data Preparation:

- Materials: Three boiler steels (10H2M, 13HMF, 15HM) in both new and service-degraded states.

- Data Collection: Create an experimental database containing paired SPT and UTT data from the same material.

- Preprocessing: The paired SPT and UTT curves form unique training examples. To prevent overfitting due to the relatively small experimental dataset, techniques like data augmentation and dropout regularization are applied throughout the CNN architecture.

3. Model Architecture and Training:

- Architecture: A 1D convolutional neural network is designed for curve-to-curve prediction. The model exploits local features in the input SPT curve.

- Training: The CNN is trained exclusively on the experimentally measured paired data. The working hypothesis is that the CNN can learn the complex, nonlinear relationship between the SPT response and the UTT response.

4. Validation and Evaluation:

- Validation: The predicted force-displacement curves from the CNN are transformed into stress-strain data.

- Key Properties: Yield strength and ultimate tensile strength are extracted from the predicted stress-strain curves.

- Success Criterion: Predictions are considered successful if the CNN-predicted UTT properties are closer to the actual UTT reference data than the estimates derived directly from conventional SPT analysis.

Protocol 2: GNN-Based Property Prediction with MatGL

This protocol describes the standard workflow for using the Materials Graph Library (MatGL) to train a Graph Neural Network for material property prediction [13].

1. Objective: To train a GNN model (e.g., MEGNet) to predict a target material property (e.g., formation energy) from a crystal structure.

2. Data Pipeline and Preprocessing:

- Input: A set of

PymatgenStructureorMoleculeobjects. - Graph Conversion: Use a graph converter (e.g.,

MGLDataset) to transform each atomic configuration into a DGL graph. - Graph Definition: Nodes represent atoms, with each node featurized by a learned embedding vector for its element. Edges represent bonds, defined based on a cutoff radius.

- Labels: A list of target properties (e.g., formation energy in eV/atom) for training.

3. Model Architecture and Training:

- Architecture: Utilize a pre-implemented GNN architecture in

matgl.models, such as MEGNet. This model will perform message passing on the graph and use a set2set or average pooling operation to create a structure-wise feature vector. - Training Module: Leverage the PyTorch Lightning (PL) training modules provided by MatGL for efficient model training and validation.

- Output: The pooled structural feature vector is passed through a final multilayer perceptron (MLP) to generate the property prediction.

4. Application:

- The trained model can be used to make instant predictions on new, unseen crystal structures by using the

predict_structuremethod.

Protocol 3: Reinforcement Fine-Tuning of Generative Models

This protocol details the procedure for using Reinforcement Learning to fine-tune a generative model for property-optimized material design, as exemplified by CrystalFormer-RL [16].

1. Objective: To fine-tune a pre-trained crystal generative model (the policy network) to generate structures that maximize a reward signal based on desired properties.

2. Components:

- Base Generative Model: A pre-trained model, such as CrystalFormer, which provides the prior distribution of stable crystals, ( p_{\text{base}}(x) ).

- Reward Model: A discriminative model that provides the reward signal, ( r(x) ). This can be an ML interatomic potential (to reward stability, e.g., low energy above convex hull) or a property prediction model (to reward a high band gap or dielectric constant).

3. Reinforcement Learning Algorithm:

- Objective Function: Maximize ( \mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}{x \sim p{\theta}(x)} [r(x) - \tau \ln \frac{p{\theta}(x)}{p{\text{base}}(x)} ] ).

- ( \mathbb{E}{x \sim p{\theta}(x)} [r(x)] ): The expected reward from the policy.

- ( \tau \ln \frac{p{\theta}(x)}{p{\text{base}}(x)} ): A KL divergence regularization term that prevents the fine-tuned model from deviating too far from the base model, controlled by the coefficient ( \tau ).

- Algorithm: Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is used to maximize this objective.

4. Outcome: The fine-tuned model, CrystalFormer-RL, learns to generate novel crystals with a higher probability of exhibiting the desired properties encoded in the reward function, effectively implementing Bayesian inference with ( p_{\text{base}}(x) ) as the prior.

Workflow Visualization and Diagrams

CNN for Mechanical Property Prediction

The diagram below illustrates the workflow for using a CNN to predict mechanical properties from experimental test data or microstructural images.

CNN Workflow for Property Prediction

GNN for Materials Property Prediction

The following diagram outlines the standard GNN-based property prediction pipeline, as implemented in libraries like MatGL.

GNN Property Prediction Pipeline

Reinforcement Learning for Material Design

This diagram visualizes the reinforcement fine-tuning loop for guiding a generative model towards materials with desired properties.

RL Fine-Tuning for Material Design

Table 2: Essential Software Tools and Libraries for ML in Materials Science

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatGL [13] | Software Library | Graph Deep Learning for Materials | "Batteries-included" library; Pre-trained GNNs & potentials; Built on DGL and Pymatgen. |

| MatGPT [4] | Foundation Model | Multi-task Materials AI | Adapts GPT architecture for materials; Used for property prediction and generation. |

| AlloyBert [17] | Transformer Model | Alloy Property Prediction | Fine-tuned RoBERTa model; Predicts properties from flexible text descriptors. |

| CrystalFormer-RL [16] | Generative Model | RL-Optimized Crystal Design | Autoregressive transformer for crystals; Fine-tuned with RL for target properties. |

| Disentangling Autoencoder (DAE) [18] | Algorithm | Unsupervised Feature Learning | Learns interpretable latent features from spectral data (e.g., for PV discovery). |

| Python Materials Genomics (Pymatgen) [13] | Library | Materials Analysis | Core library for representing and manipulating crystal structures; integrates with MatGL. |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) [13] | Library | Graph Neural Network Framework | Backend for MatGL; Provides efficient graph operations and message passing. |

The integration of machine learning into materials science is no longer a nascent trend but a core disciplinary shift. As detailed in this whitepaper, algorithms like CNNs, GNNs, and transformer-based models provide powerful, complementary tools for interpreting experimental data, predicting properties from atomic structure, and, most profoundly, generatively designing new materials. The emergence of integrated software libraries like MatGL and sophisticated paradigms like reinforcement fine-tuning are making these technologies more accessible and effective. For researchers in predictive materials synthesis, mastering this algorithmic toolkit is essential for leading the next wave of discovery, enabling a future where materials are designed with precision to meet the world's most pressing technological challenges.

Major Materials Databases Fueling Discovery (Materials Project, AFLOW, OQMD)

High-throughput density functional theory (HT-DFT) calculations have revolutionized materials discovery by enabling rapid computational screening of novel compounds. Three major databases—The Materials Project (MP), AFLOW, and the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD)—serve as foundational pillars in this paradigm, providing pre-computed properties for hundreds of thousands of materials. These repositories are indispensable for machine learning-driven materials research, supplying the extensive, structured datasets necessary for training accurate predictive models. While these databases share common foundations in DFT, methodological differences in their calculation parameters lead to variances in predicted properties that researchers must consider. The integration of these databases with advanced machine learning algorithms is now accelerating the discovery of functional materials for energy, electronics, and beyond, demonstrating an emergent capability to identify stable crystals orders of magnitude faster than traditional approaches.

The development of new materials is critical to continued technological advancement across sectors including clean energy, information processing, and transportation [19] [20]. Traditional empirical experiments and classical theoretical modeling are time-consuming and costly, creating bottlenecks in innovation cycles [3]. The Materials Genome Initiative represents a fundamental shift in this paradigm, emphasizing the creation of large sets of shared computational data to accelerate materials development [19]. Density functional theory (DFT) provides the theoretical framework for accurately predicting electronic-scale properties of crystalline solids from first principles, but for decades, calculating even single compounds required substantial expertise and computational resources [19].

With advances in computational power and algorithmic efficiency, it became feasible to predict properties of thousands of compounds systematically, leading to the emergence of high-throughput DFT calculations and materials databases [3] [19]. These databases now serve as the foundation for modern materials informatics, enabling researchers to screen candidate materials in silico before synthesis and characterization. The integration of machine learning with these rich datasets has further transformed the discovery process, allowing for the identification of complex patterns and relationships beyond human chemical intuition [21]. This whitepaper examines three major databases—Materials Project, AFLOW, and OQMD—that are central to this data-driven revolution in materials science.

Database Profiles

The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) is a high-throughput database developed in Chris Wolverton's group at Northwestern University containing DFT-calculated thermodynamic and structural properties of 1,317,811 materials as of recent counts [22] [19]. The OQMD distinguishes itself by providing unrestricted access to its entire dataset without limitations, supporting the open science goals of the Materials Genome Initiative [19]. The database contains calculations for compounds from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) alongside decorations of commonly occurring crystal structures, making it particularly valuable for predicting novel stable compounds [19].

The Materials Project (MP), established in 2011 by Dr. Kristin Persson of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, is an open-access database offering computed material properties to accelerate technology development [23]. MP includes most of the known 35,000 molecules and over 130,000 inorganic compounds, with particular emphasis on clean energy applications including batteries, photovoltaics, thermoelectric materials, and catalysts [23]. The project uses supercomputers to run DFT calculations, with commonly computed values including enthalpy of formation, crystal structure, and band gap [23].

AFLOW (Automatic FLOW) is another major high-throughput computational materials database that provides calculated properties for a vast array of inorganic materials. While specific current statistics for AFLOW were not highlighted in the search results, it is consistently referenced alongside MP and OQMD as one of the three primary HT-DFT databases [24] [3]. AFLOW provides robust infrastructure for high-throughput calculation and data management, supporting materials discovery through automated computational workflows.

Quantitative Database Comparison

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Materials Databases

| Database | Primary Institution | Materials Count | Primary Focus | Access Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OQMD | Northwestern University | ~1,300,000 [22] | DFT formation energies, structural properties | Full database download [19] |

| Materials Project | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | ~130,000 inorganic compounds [23] | Clean energy materials, battery research | Web interface, API [23] |

| AFLOW | Duke University (Consortium) | Not specified in results | High-throughput computational framework | Online database access [24] |

Table 2: Reproducibility of Properties Across Databases (Median Relative Absolute Difference) [24]

| Property | Formation Energy | Volume | Band Gap | Total Magnetization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRAD | 6% (0.105 eV/atom) | 4% (0.65 ų/atom) | 9% (0.21 eV) | 8% (0.15 μB/formula unit) |

A comprehensive comparison of these databases reveals both convergence and divergence in their predicted properties. Formation energies and volumes show higher reproducibility across databases (MRAD of 6% and 4% respectively) compared to band gaps and total magnetizations (MRAD of 9% and 8%) [24]. Notably, a significant fraction of records disagree on whether a material is metallic (up to 7%) or magnetic (up to 15%) [24]. These variances trace to several methodological choices: pseudopotentials selection, implementation of the DFT+U formalism for correlated electron systems, and elemental reference states [24]. The differences between databases are comparable to those between DFT and experiment, highlighting the importance of understanding these computational parameters when utilizing the data [24].

Methodologies: Computational Foundations and Protocols

DFT Calculation Methodologies

The fundamental methodology underlying these databases is density functional theory, which provides the foundation for high-throughput property calculation. The Materials Project primarily employs the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP), which implements DFT to calculate properties from first principles [25]. OQMD also utilizes VASP, with calculation parameters optimized for efficiency while maintaining accuracy across diverse material classes [19].

A critical challenge in HT-DFT is selecting input parameters and post-processing techniques that work across all materials classes while managing accuracy-cost tradeoffs [24]. Extensive testing on sample structures has led to established calculation flows that ensure converged results efficiently for various material classes (metals, semiconductors, oxides) [19]. The settings are consistent across all calculations within each database, ensuring that results between different compounds are directly comparable—essential for predictions of energetic stability [19].

Key methodological considerations include:

- Pseudopotentials: Most databases use projector augmented-wave (PAW) pseudopotentials within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA), typically with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) parameterization [20]

- DFT+U formalism: Applied for systems with localized electrons (e.g., transition metal oxides) to correct for self-interaction error, though implementation varies between databases [24]

- k-point sampling: Determines the resolution of reciprocal space integration, affecting convergence of electronic properties

- Elemental reference states: Choices in reference states impact formation energy calculations and consequent stability predictions [24]

Accuracy Assessment and Validation

The accuracy of DFT-predicted properties is routinely validated against experimental measurements. For the OQMD, the apparent mean absolute error between experimental measurements and calculations is 0.096 eV/atom across 1,670 experimental formation energies of compounds—representing the largest comparison between DFT and experimental formation energies to date when published [19]. Interestingly, comparison between different experimental measurements themselves reveals a mean absolute error of 0.082 eV/atom, suggesting that a significant fraction of the error between DFT and experiments may be attributed to experimental uncertainties [19].

Recent advances in computational methods are addressing accuracy limitations of standard GGA functionals. All-electron calculations using beyond-GGA density functional approximations, such as hybrid functionals (HSE06), provide more reliable data for certain classes of materials and properties not well-described by GGA [20]. These higher-fidelity calculations are particularly important for electronic properties of systems with localized electronic states like transition-metal oxides [20].

Integration with Machine Learning for Predictive Materials Synthesis

Machine Learning Paradigms in Materials Science

Machine learning has become a transformative tool in modern materials science, offering new opportunities to predict material properties, design novel compounds, and optimize performance [3]. ML addresses fundamental limitations of traditional methods by training models on extensive datasets to automate property prediction and reduce experimental efforts [3]. Deep learning techniques, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs), have achieved highly accurate predictions even for complex crystalline structures [3] [21].

The materials databases discussed provide the essential training data for these ML approaches. Modern algorithms utilize diverse data sources—high-throughput simulations, experimental measurements, and database information—to develop robust models that predict material characteristics under varied conditions [3]. A key advantage of ML is cost efficiency; while traditional DFT demands significant computational resources, ML models trained on existing data provide rapid preliminary assessments, ensuring only promising candidates undergo detailed analysis [3].

Database-Driven Discovery Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-materials discovery pipeline:

Diagram 1: Integrated materials discovery pipeline showing how databases fuel ML-driven prediction.

Case Study: Graph Networks for Materials Exploration (GNoME)

A landmark demonstration of database-powered ML discovery is the Graph Networks for Materials Exploration (GNoME) framework, which has dramatically expanded the number of known stable crystals [21]. Through large-scale active learning, GNoME models have discovered 2.2 million crystal structures stable with respect to previous computational collections, with 381,000 entries on the updated convex hull—an order-of-magnitude expansion from all previous discoveries [21].

The GNoME approach relies on two pillars: (1) generating diverse candidate structures through symmetry-aware partial substitutions (SAPS) and random structure search, and (2) using state-of-the-art graph neural networks trained on database materials to predict stability [21]. In an iterative active learning cycle, these models filter candidates, DFT verifies predictions, and the newly calculated structures serve as additional training data. Through this process, GNoME achieved unprecedented prediction accuracy of energies to 11 meV atom⁻¹ and improved the precision of stable predictions to above 80% with structure information [21].

The following diagram illustrates this active learning workflow:

Diagram 2: Active learning workflow for materials discovery, showing the iterative data flywheel process.

This framework demonstrates emergent generalization capabilities, accurately predicting structures with five or more unique elements despite their underrepresentation in training data [21]. The scale and diversity of hundreds of millions of first-principles calculations also enable highly accurate learned interatomic potentials for molecular-dynamics simulations and zero-shot prediction of ionic conductivity [21].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Materials Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Relevance to Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Software | DFT calculation package | Primary computation engine for MP, OQMD [19] [25] |

| FHI-aims | Software | All-electron DFT code | Higher-accuracy calculations beyond pseudopotentials [20] |

| pymatgen | Library | Python materials analysis | Data extraction and analysis from databases [19] |

| qmpy | Framework | Django-based database management | OQMD infrastructure [19] |

| GNoME | ML Framework | Graph neural network models | Stability prediction trained on database contents [21] |

| SISSO | ML Algorithm | Sure-Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator | Interpretable models using database properties [20] |

| AIRSS | Method | Ab initio random structure searching | Structure generation for compositional predictions [21] |

Future Directions and Challenges

The field of computational materials discovery continues to evolve, with several emerging trends and persistent challenges. Beyond-GGA density functionals, including meta-GGA (e.g., SCAN) and hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06), are addressing accuracy limitations for certain material classes and properties [20]. All-electron calculations provide enhanced reliability across diverse material systems, though at increased computational cost [20].

Machine learning models face challenges including data quality and quantity limitations, model interpretability, and transferability to unexplored chemical spaces [3]. The variance between major databases highlights the need for continued standardization of HT-DFT methodologies to improve reproducibility [24]. Furthermore, the integration of ML with automated laboratories (self-driving labs) is creating new paradigms for closed-loop materials discovery and optimization [3].

As these databases grow and ML techniques advance, we are witnessing the emergence of materials foundation models—pre-trained neural networks that can be fine-tuned for diverse property prediction tasks. The scaling laws observed with GNoME suggest that further expansion of datasets and model complexity will continue to improve prediction accuracy and generalization [21]. This progress promises to accelerate the discovery of functional materials for critical technologies including energy storage, quantum computing, and environmental remediation.

The Materials Project, AFLOW, and OQMD have established themselves as indispensable infrastructure for modern materials research, collectively providing calculated properties for millions of compounds. These databases have transitioned materials discovery from serendipitous experimental finds to systematic computational screening, dramatically accelerating the identification of promising candidates for specific applications. Their integration with machine learning represents a paradigm shift, enabling predictive materials synthesis that transcends traditional chemical intuition. As these resources continue to expand and improve, they will play an increasingly central role in addressing global challenges through the development of novel functional materials, ultimately demonstrating the power of data-driven science to transform a foundational technological domain.

ML in Action: Predictive Models for Property Prediction and Synthesis Design

In the evolving paradigm of data-driven materials science, feature engineering constitutes the foundational process of translating complex chemical information into structured, computable numerical representations known as descriptors. This translation enables machine learning (ML) algorithms to discern patterns and relationships within material data, thereby accelerating the discovery and development of novel materials and pharmaceuticals. Within the broader thesis of machine learning for predictive materials synthesis, descriptors serve as the critical bridge between raw chemical data and predictive models, allowing researchers to move beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches toward more efficient, principled design strategies [26]. The transformative potential of this approach is evidenced by its application across diverse domains, from nanomaterial research to drug discovery, where it significantly reduces the time, cost, and labor associated with experimental approaches [27] [26].

The central challenge in materials informatics (MI) lies in effectively capturing the intricate relationships between a material's composition, structure, synthesis conditions, and its resulting properties. Feature engineering addresses this challenge by creating standardized numerical representations that encode essential chemical information in forms amenable to machine learning algorithms. These descriptors enable the application of ML across the materials development pipeline, from initial property prediction to the optimization of synthesis parameters and the identification of promising candidate materials for targeted applications [28] [26]. As the field progresses, the development of more sophisticated, automated descriptor extraction methods continues to enhance the accuracy and scope of predictive materials modeling.

Molecular Descriptors: Fundamental Concepts and Typologies

Molecular descriptors are quantitative representations of molecular structure and properties that serve as input features for machine learning models in materials science and drug discovery. These descriptors can be broadly categorized into two primary approaches: knowledge-based feature engineering, which relies on domain expertise to select chemically meaningful features, and automated feature extraction, where neural networks learn relevant representations directly from raw structural data [26].

Knowledge-based descriptors encompass a wide range of chemically significant properties, including molecular weight, atom counts, topological indices, electronegativity, and van der Waals radii. For inorganic materials, features often include statistical aggregates (mean, variance) of elemental properties like atomic radii and electronegativity across the composition [26]. These human-engineered features provide interpretability and perform robustly even with limited data, though their selection must often be tailored to specific material classes or properties.

In contrast, automated feature extraction methods, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), have gained prominence for their ability to learn optimal representations directly from data without explicit human guidance. GNNs represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, automatically learning feature representations that encode information about local chemical environments, spatial arrangements, and bonding relationships [26]. This approach achieves high predictive accuracy, especially for complex structure-property relationships where manual feature design is challenging, though it typically requires larger datasets for effective training.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Descriptor Approaches

| Feature Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge-Based Descriptors | Features derived from chemical knowledge and domain expertise | Interpretable, robust with small datasets, physically meaningful | Requires domain expertise, may need optimization for different material classes | PaDEL-Descriptor, alvaDesc, RDKit [29] |

| Automated Feature Extraction | Features learned automatically from raw structural data | High accuracy, eliminates manual feature engineering, captures complex patterns | Requires large datasets, less interpretable, computationally intensive | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), MatInFormer [26] [30] |

| Hybrid Approaches | Combines knowledge-based and automated features | Balances interpretability with performance | Increased complexity in model design | Translation-based autoencoders [31] |

A third, emerging category involves hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. For instance, the Materials Informatics Transformer (MatInFormer) incorporates crystallographic information through tokenization of space group data, blending domain knowledge with learned representations [30]. Similarly, neural translation models have been developed that learn continuous molecular descriptors by translating between equivalent chemical representations, effectively compressing shared information into low-dimensional vectors that demonstrate competitive performance across various quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling tasks [31].

Methodologies for Descriptor Generation and Validation

Knowledge-Based Feature Engineering Protocols

The implementation of knowledge-based descriptor generation follows a systematic workflow beginning with data collection and culminating in model-ready features. For organic molecules, standard protocols involve processing chemical structures (often in SMILES format) through computational tools that calculate predefined molecular properties. The experimental methodology typically employs software packages such as RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor, or alvaDesc, which generate extensive descriptor sets encompassing topological, electronic, and structural characteristics [29].

A representative experimental protocol for generating knowledge-based descriptors involves these key stages:

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of molecular structures in standardized formats (e.g., SMILES, SDF) or material compositions with precise stoichiometries.

- Descriptor Calculation: Process structures through descriptor calculation software (e.g., PaDEL-Descriptor) to generate initial feature vectors. For inorganic materials, this may involve computing statistical moments of elemental properties across the composition.

- Feature Selection: Apply correlation analysis and domain knowledge to reduce dimensionality by removing highly correlated or non-informative descriptors.

- Model Training & Validation: Implement machine learning models using the selected descriptors and evaluate performance through appropriate cross-validation strategies, paying careful attention to dataset redundancy issues [32].

This approach was effectively demonstrated in a study on Cu-Cr-Zr alloys, where feature engineering identified aging time and Zr content as critically important for hardness prediction, while aging time alone predominantly controlled electrical conductivity – findings that aligned well with established metallurgical principles [33].

Automated Feature Extraction with Graph Neural Networks

Automated feature extraction using Graph Neural Networks represents a paradigm shift from manual descriptor engineering. The experimental workflow for GNN-based feature extraction involves several standardized steps:

- Graph Representation: Convert molecular structures into graph representations where atoms constitute nodes (with features like atom type, hybridization) and bonds constitute edges (with features like bond type, conjugation).

- Graph Encoding: Process the molecular graph through multiple GNN layers where node representations are iteratively updated by aggregating information from neighboring nodes using message-passing mechanisms.

- Graph-Level Representation: Generate a global molecular representation by pooling node-level features through summation, averaging, or attention-based methods.

- Property Prediction: Feed the final graph representation into a prediction layer (typically a fully connected neural network) to estimate target properties.

The Materials Informatics Transformer (MatInFormer) exemplifies an advanced implementation of this approach, adapting transformer architecture – originally developed for natural language processing – to materials property prediction by tokenizing crystallographic information and learning representations that capture essential structure-property relationships [30]. Benchmark studies demonstrate that these automated approaches achieve competitive performance across diverse property prediction tasks, though they require careful attention to dataset construction and model architecture selection.

Performance Evaluation and Validation Strategies

Robust validation of descriptor performance is essential for reliable materials informatics. Standard evaluation metrics include Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for regression tasks, which measures the average magnitude of prediction errors, and the Coefficient of Determination (R²) that quantifies how well the model explains variance in the target property [34]. For classification tasks, metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are commonly employed.

A critical consideration in performance evaluation is addressing dataset redundancy, which can lead to overly optimistic performance estimates. Materials databases often contain many highly similar structures due to historical "tinkering" approaches in materials design [32]. Standard random splitting of such datasets can cause data leakage between training and test sets, inflating perceived model performance. The MD-HIT algorithm addresses this by controlling redundancy through similarity thresholds, ensuring more realistic performance evaluation that better reflects a model's true predictive capability, particularly for out-of-distribution samples [32].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Descriptor Evaluation

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | $\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}(yi-\hat{y}_i)^2}$ | Average prediction error magnitude | Closer to 0 is better |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | $1 - \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(yi-\hat{y}i)^2}{\sum{i=1}^{n}(y_i-\bar{y})^2}$ | Proportion of variance explained by model | Closer to 1 is better |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | $\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}|yi-\hat{y}_i|$ | Average absolute prediction error | Closer to 0 is better |

| Recovery Rate | $\frac{\text{Number of top compounds correctly identified}}{\text{Total number of top compounds}}$ | Effectiveness in identifying high-value candidates | Closer to 1 is better |

Beyond standard metrics, applicability domain analysis helps determine the boundaries within which a model's predictions are reliable, while techniques like leave-one-cluster-out cross-validation provide more realistic performance estimates for materials discovery scenarios where the goal is often extrapolation to genuinely new materials rather than interpolation within known chemical spaces [32].

Implementing effective feature engineering for materials informatics requires both computational tools and conceptual frameworks. The following essential resources constitute the core toolkit for researchers in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Descriptor Generation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics library | Calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints | General-purpose small molecule characterization [29] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software wrapper | Compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints | High-throughput descriptor calculation [29] |

| alvaDesc | Commercial software | Molecular descriptor calculation and analysis | Comprehensive descriptor generation for QSAR [29] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Deep learning architecture | Automated feature learning from molecular graphs | Complex structure-property relationship modeling [26] |

| MatInFormer | Transformer model | Materials property prediction using crystallographic data | Inorganic materials and crystal structure analysis [30] |

| MD-HIT | Data preprocessing algorithm | Dataset redundancy control for materials data | Robust model evaluation and training [32] |

These tools enable the transformation of chemical structures into computable descriptors through various approaches. For instance, RDKit provides comprehensive functionality for calculating topological, constitutional, and quantum chemical descriptors, while PaDEL-Descriptor offers a streamlined interface for high-throughput descriptor calculation [29]. For more specialized applications, tools like the Materials Informatics Transformer (MatInFormer) adapt language model architectures to materials science by tokenizing crystallographic information and learning representations that capture essential structure-property relationships [30].

As dataset quality fundamentally limits model performance, tools like MD-HIT address the critical issue of redundancy in materials databases by controlling similarity thresholds during dataset construction, ensuring more realistic performance evaluation and improved model generalizability [32]. This is particularly important given the historical tendency of materials databases to contain numerous highly similar structures due to incremental modification approaches in traditional materials design.

Advanced Applications in Materials Science and Drug Discovery

Nanomaterials Design and Synthesis Optimization

Feature engineering plays a pivotal role in nanomaterials research, where it helps navigate the complex synthesis-structure-property relationships that govern material performance. Machine learning approaches employing carefully crafted descriptors have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in predicting synthesis parameters, characterizing nanomaterial structures, and forecasting properties of nanocomposites [27]. This data-driven paradigm represents a fundamental shift from traditional trial-and-error methods, enabling more efficient exploration of the vast design space in nanotechnology.

The application of descriptors in nanomaterials research follows the synthesis-structure-property-application framework, where descriptors encoding synthesis conditions (precursor concentrations, temperature, time) and structural characteristics (size, morphology, surface chemistry) are linked to functional properties (catalytic activity, optical response, mechanical strength) [27]. For instance, in designing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with architectured porosity, descriptors capturing topological features and metal-cluster chemistry have proven essential for predicting gas adsorption capacity and selectivity. Similarly, for electrospun PVDF piezoelectrics and 3D-printed mechanical metamaterials, descriptors encoding processing parameters and structural features enable accurate prediction of functional performance [28].

Active Learning in Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening

In pharmaceutical research, descriptor engineering enables more efficient drug discovery through active learning approaches to molecular docking. The tremendous size of chemical space – with libraries often containing hundreds of millions of compounds – makes exhaustive virtual screening computationally prohibitive [34]. Active learning strategies address this challenge by iteratively selecting the most informative compounds for docking simulations based on predictions from surrogate models trained on molecular descriptors.

The standard workflow for active learning in molecular docking involves:

- Initial Sampling: A random selection of compounds is screened through molecular docking to generate initial training data.

- Surrogate Model Training: Machine learning models (using descriptors as input features) are trained to predict docking scores.

- Informed Compound Selection: Acquisition functions (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound, Uncertainty Sampling) use the surrogate model's predictions to select the next compounds for docking, balancing exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of promising areas.

- Iterative Refinement: New docking results are incorporated into the training set, and the process repeats until computational budgets are exhausted or satisfactory hits are identified [34].

This approach demonstrates how thoughtfully engineered descriptors, even without explicit 3D structural information, can effectively guide exploration of chemical space in drug discovery. Surrogate models tend to memorize structural patterns associated with high docking scores during acquisition steps, enabling efficient identification of active compounds from extensive libraries like DUD-E and EnamineReal [34].

Explainable AI for Interpretable Materials Design

Recent advances in explainable AI (XAI) techniques have enhanced the interpretability of descriptor-based models, providing crucial insights into structure-property relationships. Methods such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) quantify the contribution of individual descriptors to model predictions, helping researchers validate models against domain knowledge and identify potentially novel physical relationships [33].