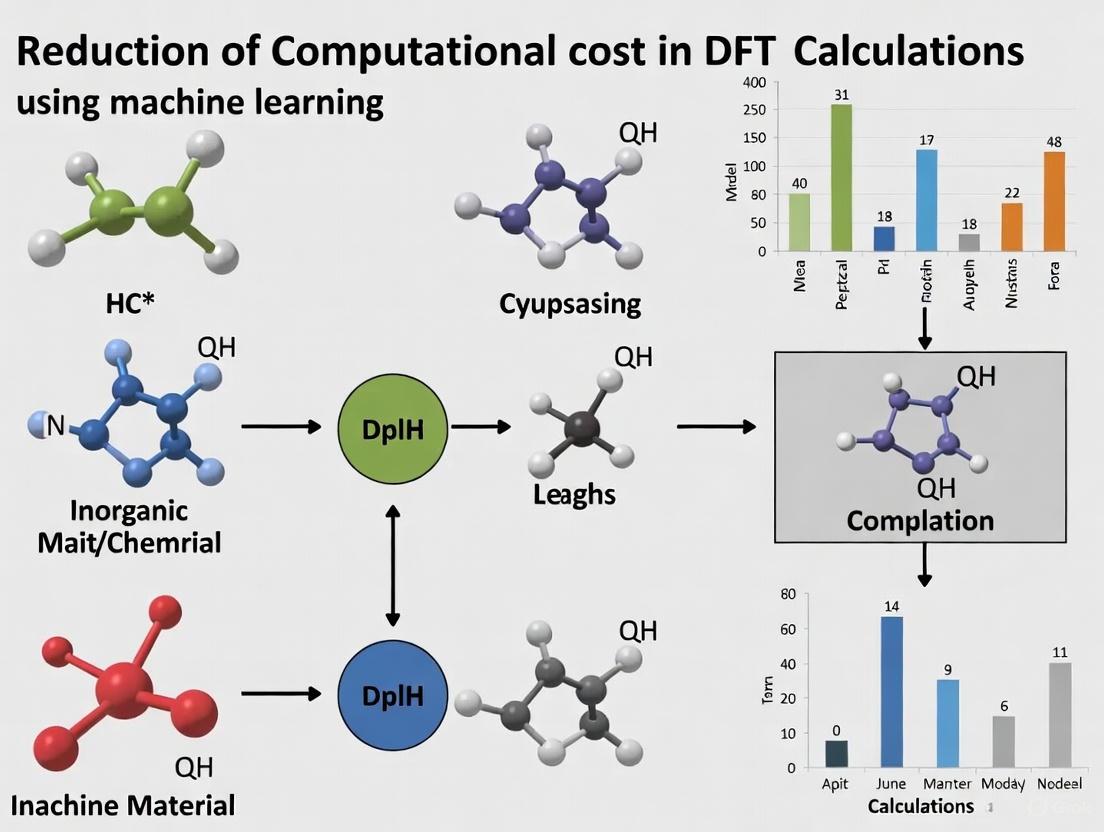

Machine Learning Accelerates Density Functional Theory: Cutting Computational Costs for Drug and Materials Discovery

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and materials science but is plagued by high computational costs that limit its application to large, complex systems.

Machine Learning Accelerates Density Functional Theory: Cutting Computational Costs for Drug and Materials Discovery

Abstract

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and materials science but is plagued by high computational costs that limit its application to large, complex systems. This article explores the transformative integration of machine learning (ML) to overcome this bottleneck. We cover foundational concepts, detailing the limitations of traditional DFT and the emergence of ML as a solution. The review then delves into key methodological approaches, including machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) and surrogate models, highlighting their application in biomedical and materials research. Practical guidance on troubleshooting data and model selection is provided, followed by a critical evaluation of model performance and transferability. By synthesizing these areas, this article serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and professionals seeking to leverage ML-accelerated DFT for accelerated discovery.

The DFT Bottleneck and the Rise of Machine Learning Solutions

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become an indispensable tool for simulating matter at the atomistic level, guiding discoveries in chemistry, materials science, and drug development. Its value lies in transforming the intractable many-electron Schrödinger equation into a solvable problem. However, a fundamental challenge limits its broader application: computational cost that scales cubically with system size (O(N³)) [1] [2]. This means that doubling the number of atoms in a simulation increases the computational cost by a factor of eight. For large systems, this scaling quickly makes calculations prohibitively expensive in terms of time and computational resources.

This article explores the roots of DFT's scalability challenge and how modern research, particularly in machine learning (ML), is creating new pathways to overcome these barriers, enabling the study of larger and more complex systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary source of DFT's high computational cost? The primary cost arises from solving the Kohn-Sham equations, which involves computing the electronic wavefunctions. A critical step is the orthogonalization of these wavefunctions, a mathematical procedure whose cost scales with the cube of the number of electrons (or atoms) in the system, denoted as O(N³) [1] [2]. While the exact reformulation of DFT is elegant, its practical application relies on approximations for the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, and achieving higher accuracy with more complex functionals further increases the computational burden [2].

Q2: What system sizes are currently feasible with conventional DFT? For typical DFT calculations with a high level of approximation, the maximum achievable system size is limited to around 1,000 atoms [1]. Beyond this point, the computational cost and time required become impractical for most research applications. This limits the ability to accurately simulate material phenomena with long-range effects, such as large polarons, spin spirals, and topological defects [1].

Q3: How does the "Jacob's Ladder" of functionals relate to computational cost? Jacob's Ladder classifies XC functionals by complexity and accuracy, from the Local Density Approximation (LDA) up to complex double hybrids. Climbing the ladder towards "chemical accuracy" ( ~1 kcal/mol error) traditionally means incorporating more complex, hand-designed descriptors of the electron density. This inevitably comes at the price of a significantly increased computational cost, creating a trade-off between accuracy and feasibility [2].

Q4: My DFT calculations are too slow. What are my options to reduce computational time? You can consider several strategies:

- Multi-Level Approaches: Use a robust but faster method (e.g., a meta-GGA functional like r2SCAN) for geometry optimization, and a more accurate (but slower) method for single-point energy calculations [3].

- Machine Learning Potentials: Train or use a pre-trained Neural Network Potential (NNP) like EMFF-2025 or the Deep Potential (DP) scheme to run molecular dynamics simulations with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the cost [4].

- ML-Accelerated Screening: For high-throughput screening (e.g., of catalysts), use ML regression models (like XGBoost) to predict key properties like adsorption energy, using a smaller set of DFT calculations for training. This can reduce the number of required DFT runs by orders of magnitude [5] [6].

- Advanced Algorithms: New high-performance computing (HPC) algorithms, like the block linear system solver developed at Georgia Tech, can enhance the efficiency of specific, expensive parts of DFT calculations, such as computing electronic correlation energy within the Random Phase Approximation (RPA) [7].

Q5: Are ML-based methods accurate enough to replace my DFT workflow? In many cases, yes. The field has seen remarkable progress. ML models can now act as surrogates or emulators for DFT, achieving chemical accuracy for specific properties and systems [8] [2]. For instance:

- ML-DFT Emulation: End-to-end models map atomic structure directly to electronic properties and energies, bypassing the explicit solution of the Kohn-Sham equation with orders of magnitude speedup [9].

- Error Correction: ML models can be trained to predict and correct the systematic errors in DFT-calculated properties (e.g., formation enthalpies), improving predictive reliability against experimental data [8]. The key is that these models are trained on high-quality DFT or experimental data and are best suited for applications within the chemical space of their training data.

Machine Learning Solutions: A Comparative Table

The following table summarizes several key machine-learning approaches being developed to overcome DFT's computational bottlenecks.

Table 1: Machine Learning Approaches for Accelerating DFT Calculations

| ML Approach | Core Methodology | Key Advantage | Example Applications | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Based XC Functional [2] | Deep learning is used to learn the XC functional directly from a vast dataset of highly accurate quantum chemical data. | Reaches experimental accuracy without the need for computationally expensive, hand-designed features of Jacob's Ladder. | Accurate prediction of atomization energies for main-group molecules. | Retains the standard O(N³) DFT scaling but with vastly improved accuracy, making each calculation more valuable. |

| DFT Emulation [9] | An end-to-end ML model that maps atomic structure to electronic charge density, from which other properties are derived. | Bypasses the explicit, costly solution of the Kohn-Sham equation entirely. | Predicting electronic properties (DOS, band gap) and atomic forces for organic molecules and polymers. | Linear scaling with system size (O(N)) with a small prefactor, enabling large-scale simulations. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) [4] | A neural network is trained to predict potential energy surfaces and atomic forces from atomic configurations. | Enables molecular dynamics simulations at DFT-level accuracy with the computational cost of a classical force field. | Studying mechanical properties and thermal decomposition of high-energy materials (HEMs). | Linear scaling with system size, allowing simulations of thousands of atoms over long timescales. |

| ML-Accelerated Screening [5] [6] | ML regression models (e.g., XGBoost) are trained on a subset of DFT data to predict properties for a vast materials space. | Dramatically reduces the number of required DFT calculations during high-throughput screening. | Screening high-entropy alloy catalysts for hydrogen evolution or CO₂ reduction. | Decouples the exploration cost (cheap ML predictions) from the validation cost (expensive DFT). |

Experimental Protocol: ML-Accelerated Catalyst Screening

The following workflow diagram and description outline a standard protocol for using machine learning to accelerate the discovery of new catalysts, as applied in recent studies on high-entropy alloys [5] [6].

Diagram Title: ML-Accelerated High-Throughput Screening Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define the Material Space: Identify the compositional space to be explored. For example, in a study on PtPd-based high-entropy alloys (HEAs), the space was defined as PtPdXYZ (where X, Y, Z = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, etc.) [5].

- Generate a Small DFT Training Set: Perform a limited number of ab initio DFT calculations for a representative subset of configurations.

- Train the Machine Learning Model: Use the DFT results to train a regression model.

- Features: Input features typically include elemental concentrations, weighted atomic numbers, and interaction terms [8].

- Model Selection: Test different algorithms (e.g., Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBR) [5], Neural Networks [8]) and use cross-validation (e.g., GridSearchCV) to select the best-performing model [6].

- Predict Properties with ML: Use the trained ML model to predict the target properties for the entire material space (e.g., all 56 possible PtPd-based HEA configurations) [5]. This step is computationally cheap and fast.

- Screen Top Candidates: Rank the predicted materials based on the desired property profile (e.g., optimal adsorption energy for a specific reaction).

- DFT Validation: Perform full DFT calculations on the top-ranked candidate materials from the ML screening to validate the ML predictions. This final step ensures accuracy and reliability before experimental synthesis is considered.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Computational Reagents

Table 2: Essential Software and Methodological "Reagents" for Modern DFT/ML Research

| Tool / Method | Category | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| VASP [9] | DFT Software | A widely used package for performing ab initio DFT calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Often used to generate high-quality training data. |

| SPARC [7] | DFT Software | A real-space electronic structure software package designed for accurate, efficient, and scalable solutions of DFT equations on HPC systems. |

| Deep Potential (DP) [4] | ML Potential | A framework for developing neural network potentials (NNPs) that can achieve DFT accuracy with much lower computational cost for molecular dynamics. |

| XGBoost (XGBR) [5] | ML Model | A powerful and efficient implementation of gradient-boosted decision trees, often used for ML-accelerated property prediction and screening. |

| AGNI Fingerprints [9] | Atomic Descriptor | Machine-readable representations of an atom's chemical environment that are translation, rotation, and permutation invariant. Used as input for ML models. |

| Random Phase Approximation (RPA) [7] | Advanced Algorithm | A highly accurate method for calculating electronic correlation energy. New HPC algorithms are making it more scalable and practical for larger systems. |

| r²SCAN Functional [3] | DFT Functional | A modern, robust meta-GGA functional that offers a good balance of accuracy and computational cost, often recommended in best-practice protocols. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Property Prediction Despite Low Energy/Force Errors

Problem: Your Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) shows excellent root-mean-square error (RMSE) for energies and forces during validation, but produces inaccurate results for key material properties like defect formation energies, diffusion barriers, or elastic constants [10].

Explanation: This occurs because standard training and validation datasets are often dominated by near-equilibrium configurations. Low average energy and force errors do not guarantee accuracy for specific, underrepresented atomic environments critical for certain properties [10].

Solution:

- Implement Targeted Error Metrics: Use metrics beyond overall energy/force RMSE. Evaluate forces on atoms in "rare event" (RE) configurations (e.g., near diffusion pathways or defects). MLIPs scoring poorly on RE-force metrics often show errors in diffusional properties [10].

- Enhance Your Training Dataset: Augment your dataset with configurations relevant to the failing properties. This includes:

- Validate on Properties, Not Just Forces: Directly benchmark the MLIP on a small set of representative physical properties during the validation phase [10].

Guide 2: Managing the Trade-off Between Multiple Property Accuracies

Problem: Improving your MLIP's accuracy for one property (e.g., elastic constants) leads to degraded performance for another (e.g., vacancy formation energy) [10].

Explanation: This is a fundamental challenge. Different material properties probe different aspects of the potential energy surface (PES). Optimizing for one region of the PES can negatively impact the model's performance in another, revealing inherent trade-offs [10].

Solution:

- Identify Representative Properties: Perform a correlation analysis on the errors of multiple MLIP models. Certain property errors are often correlated. Identifying a reduced set of "representative properties" allows for more efficient training to improve joint performance across many properties [10].

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Use Pareto front analysis during model selection. Instead of picking a single "best" model based on one metric, identify models that represent the optimal trade-off (Pareto front) between two or more key properties. This allows you to consciously select a model based on your priority properties [10].

- Leverage a Foundation Model Approach: If available, start from a large, pre-trained foundation model for atomistic simulations. These models, pre-trained on massive and diverse datasets, are more robust and can be fine-tuned with a small amount of system-specific data to achieve good performance across multiple properties, potentially mitigating the need for painful trade-offs [11].

Guide 3: Handling Unphysical Results and Model Extrapolation

Problem: During molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, your MLIP produces unphysical atomic configurations, drastic energy swings, or erroneous forces [10] [12].

Explanation: The MLIP is likely extrapolating—making predictions for atomic environments far outside its training data distribution. MLIPs are interpolative and can be unreliable when they extrapolate [12].

Solution:

- Implement Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): Use methods like the delta method for neural network potentials to calculate a model's uncertainty for a given prediction. A high uncertainty value is a strong indicator of extrapolation [12].

- Employ Active Learning: Use the UQ measure in an active learning loop. When uncertainty exceeds a threshold during a simulation, that configuration is automatically sent for DFT calculation and added to the training dataset. This iteratively builds a more robust and reliable potential [11] [12].

- Ensure Dataset Diversity: Proactively build your training set to cover all relevant chemical and configurational spaces you expect to encounter in production simulations, including defects, surfaces, and liquid phases [9] [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core "Accuracy vs. Cost" trade-off in atomistic simulations?

The trade-off is between the computational cost of a simulation method and its physical accuracy. High-accuracy quantum methods like quantum many-body (QMB) are prohibitively expensive for large systems or long timescales. Density Functional Theory (DFT) offers a cheaper approximation but uses inexact exchange-correlation functionals, limiting its accuracy. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) aim to bridge this gap, offering near-DFT accuracy at a fraction of the cost, but introduce new trade-offs regarding data, transferability, and property-specific accuracy [9] [13] [12].

FAQ 2: How can Machine Learning reduce the cost of my DFT calculations?

ML can reduce cost in two primary ways:

- As a Surrogate Potential: MLIPs are trained on DFT data to learn the relationship between atomic structure and energy/forces. Once trained, they can perform molecular dynamics simulations orders of magnitude faster than AIMD, enabling the study of longer timescales and larger systems [9] [12].

- Emulating DFT Itself: End-to-end ML models can map an atomic structure directly to its electronic charge density and related properties (energy, forces, DOS), effectively bypassing the explicit, iterative solution of the Kohn-Sham equations. This provides a dramatic speedup (linear scaling with system size) while maintaining chemical accuracy [9].

FAQ 3: My MLIP has low validation errors but high property errors. Why?

Standard validation metrics like energy and force RMSE are averaged over your test set, which may lack sufficient examples of the specific atomic configurations that govern the property you are interested in (e.g., transition states for diffusion). A model can be very accurate for common, near-equilibrium structures but fail for rare, high-energy configurations that are critical for certain properties [10]. Refer to Troubleshooting Guide 1 for solutions.

FAQ 4: Is it possible to create a single, universal ML potential that is accurate for everything?

Current evidence suggests this is very difficult. While "universal potentials" like MACE-MP-0 are accurate for a broad range of systems at one level of theory, they are not considered true "foundation models." Achieving high accuracy across a vast array of different properties and chemical spaces simultaneously often involves trade-offs, where improving one property can worsen another [11] [10]. The field is moving towards large-scale foundation models that are more robust and easily fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks [11].

FAQ 5: How can I quantify the reliability of my MLIP's predictions?

You should implement Uncertainty Quantification (UQ). Methods like the delta method can provide an uncertainty measure for a model's energy or force prediction. A high uncertainty signal indicates the model is extrapolating and its prediction may be unreliable. This is crucial for building trust and automating active learning [12].

Table 1: Performance Overview of Different Simulation Methods

| Method | Computational Cost | Key Accuracy Limitation | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Many-Body (QMB) | Extremely High | Computationally prohibitive for most systems | Gold-standard accuracy for small molecules [13] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | High | Approximation in the exchange-correlation functional [13] | High-throughput screening; medium-scale MD [9] |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Low (after training) | Accuracy depends on quality and breadth of training data [12] | Large-scale/long-time MD; property prediction [9] [10] |

| ML-DFT Emulation | Very Low | Transferability to unseen system types [9] | Fast electronic property prediction; energy/force calculation [9] |

Table 2: Analysis of MLIP Performance Trade-offs (based on a study of 2300 models for Si) [10]

| Property Category | Examples | Typical Challenge for MLIPs |

|---|---|---|

| Defect Properties | Vacancy/Interstitial Formation Energy | Often underrepresented in standard training sets [10] |

| Elastic & Mechanical | Elastic Constants, Stress Tensor | Can trade off against accuracy of other properties like defect energies [10] |

| Rare Events | Diffusion Barriers, Transition States | High errors in forces on "rare event" atoms despite low overall force RMSE [10] |

| Thermodynamic | Free Energy, Entropy, Heat Capacity | Derived from dynamics, requiring accurate PES over simulation time [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Robust MLIP for Molecular Dynamics

Objective: To create an MLIP that is accurate and stable for molecular dynamics simulations of a specific material system.

Methodology:

- Initial Data Generation:

- Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) at relevant temperatures to collect diverse atomic configurations.

- Include different system types if applicable (e.g., for organic materials: molecules, polymer chains, crystals) [9].

- Compute reference energies, forces, and stresses using DFT for all configurations.

- Fingerprinting:

- Model Training & Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Train an MLIP model (e.g., NNP, MTP, DeePMD) on ~90% of the data.

- Conduct hyperparameter tuning, saving a large validation pool of models [10].

- Active Learning & Iterative Refinement:

Protocol 2: Emulating DFT with an End-to-End Deep Learning Model

Objective: To bypass the Kohn-Sham equations and directly predict electronic charge density and derived properties.

Methodology:

- Database Creation:

- Generate a database of diverse structures (molecules, polymers, crystals).

- Use DFT to compute the reference electronic charge density on a grid, density of states (DOS), total energy, and atomic forces [9].

- Two-Step Learning Procedure:

- Step 1 - Charge Density Prediction: Train a deep neural network to map atomic structure fingerprints (e.g., AGNI) to a decomposition of the electron charge density, often using a learned basis set like Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) [9].

- Step 2 - Property Prediction: Use the predicted charge density descriptors as auxiliary input to other networks to predict properties like DOS, total energy, and atomic forces. This aligns with the core principle of DFT that the charge density determines all properties [9].

- Validation: Test the model on a held-out set of structures to validate the accuracy of the charge density, energy, forces, and derived electronic properties against DFT [9].

Workflow Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Components for Machine Learning in Atomistic Simulation

| Item | Function | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Data | Serves as the ground truth for training and testing ML models. | DFT-calculated energies, forces, stresses; QMB data for higher accuracy [13] [9]. |

| Atomic Fingerprints/Descriptors | Converts atomic coordinates into a rotation- and translation-invariant representation for the ML model. | AGNI fingerprints [9], Behler-Parrinello descriptors [12], Moment Tensor descriptors [10]. |

| MLIP Architectures | The machine learning models that learn the potential energy surface. | Neural Network Potentials (NNP) [12], Moment Tensor Potential (MTP) [10], Deep Potential (DeePMD) [10]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Method | Identifies when a model is making predictions outside its training domain. | Delta method [12], Bayesian inference, ensemble methods. |

| Active Learning Loop | An iterative process to intelligently and efficiently build training datasets. | Algorithm that uses UQ to select new configurations for DFT calculation [11] [12]. |

| Benchmarking & Error Metrics | Evaluates model performance beyond basic force/energy errors. | Property-based benchmarks (defect energy, elastic constants) [10]; rare-event force metrics [10]. |

This technical support center provides guidance for researchers integrating Machine Learning (ML) to reduce the computational cost of Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. The following guides and FAQs address common challenges in developing and applying ML-driven solutions for quantum mechanical simulations.

# Troubleshooting Guides

# Guide 1: Addressing Poor Predictive Accuracy in ML-Corrected DFT

Problem: Your Machine Learning model, designed to correct DFT formation enthalpies, shows poor accuracy on validation data, leading to unreliable phase stability predictions.

Solution: Systematically check your data and model architecture.

Check 1: Data Quality and Preprocessing

- Action: Audit your dataset for common issues. Handle missing values by either removing data points with multiple missing features or imputing values (using mean, median, or mode) for features with only a few missing entries [14].

- Action: Ensure your dataset is balanced. If it is skewed towards one target class (e.g., one type of crystal structure), use resampling or data augmentation techniques [14].

- Action: Identify and remove outliers using statistical visualization tools like box plots [14].

- Action: Apply feature normalization or standardization to bring all features (e.g., elemental concentrations, atomic numbers) onto the same scale, preventing features with larger magnitudes from dominating the model [14] [8].

Check 2: Feature Selection and Model Tuning

- Action: Select the most relevant features. Use methods like Univariate Selection (e.g.,

SelectKBest) or tree-based algorithms (e.g., Random Forest) to evaluate feature importance and reduce dimensionality [14]. - Action: Perform hyperparameter tuning. Adjust model parameters (e.g., the number of neighbors

kin KNN) by running the learning algorithm over the training dataset to find the optimal values for your specific data [14]. - Action: Use cross-validation to select the best model and avoid overfitting. Divide your data into

ksubsets; usek-1for training and one for validation, repeating the processktimes. This helps create a final model that generalizes well to new data [14] [8].

- Action: Select the most relevant features. Use methods like Univariate Selection (e.g.,

# Guide 2: Managing Computational Cost and Data Efficiency in ML Force Fields

Problem: Creating a Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF) is computationally expensive and requires unfeasibly large quantum datasets, negating the efficiency gains.

Solution: Improve data efficiency by incorporating physical knowledge and using advanced representations.

Check 1: Incorporate Physical Symmetries and Constraints

- Action: Use a model that enforces physical laws and symmetries. The BIGDML framework, for example, employs the full translation and Bravais symmetry group of the crystal, which dramatically reduces the amount of data needed for training [15]. What is known physically does not need to be learned from data [15].

Check 2: Employ Global Representations

- Action: Consider a global representation of your system instead of a local, atom-based one. While many MLFFs use a "locality approximation" that breaks the system into atomic contributions, this can neglect important long-range interactions. A global representation, such as the periodic Coulomb matrix descriptor used in BIGDML, treats the supercell as a whole, capturing long-range correlations and improving accuracy with less data [15].

Check 3: Leverage Small, High-Quality Datasets

- Action: Focus on generating a diverse but compact set of reference configurations. The BIGDML approach has been shown to achieve high accuracy (errors below 1 meV/atom) with training sets of just 10–200 geometries by making maximal use of each data point [15].

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

# DFT and ML Fundamentals

Q1: What is the core motivation for using ML to correct DFT calculations? DFT, while widely used, has intrinsic errors in its exchange-correlation functionals that limit its quantitative accuracy, particularly for predicting formation enthalpies and phase stability in complex alloys [8]. ML models can learn the systematic discrepancy between DFT-calculated and experimentally measured values, providing a corrective function that significantly improves predictive reliability without the cost of higher-level quantum methods [8].

Q2: What is a Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF), and how does it differ from traditional force fields? An MLFF is a model that uses machine learning to predict interatomic forces and energies based on reference data from quantum mechanical methods [16]. Unlike traditional analytical force fields (like EAM or Lennard-Jones), which rely on pre-specified functional forms, MLFFs learn the complex potential energy surface directly from data, allowing them to achieve quantum-level accuracy while being far faster than repeated DFT calculations [16].

Q3: What is the key difference between a local and a global representation in MLFFs? Most MLFFs use a local representation, where the total energy of the system is approximated as a sum of individual atomic contributions, typically within a cutoff radius [15]. This "locality approximation" can miss long-range interactions. In contrast, a global representation (e.g., in BIGDML) treats the entire supercell as a single entity, which can rigorously capture many-body correlations and long-range effects, often leading to greater data efficiency [15].

# Implementation and Best Practices

Q4: My ML-DFT model works well on training data but poorly on new systems. What should I do? This is likely an issue of overfitting and a lack of generalizability. Ensure you are using cross-validation during training [14]. Also, consider incorporating more physically meaningful features (like atomic potentials, not just energies) into your training data, as this can create a more robust and transferable model [13]. Actively managing your dataset through uncertainty quantification can identify underrepresented regions for targeted data addition [16].

Q5: How can I quantify the uncertainty of my MLFF's predictions?

You can implement a distance-based uncertainty measure. For a new atomic configuration, calculate the minimum distance (d_min) between its fingerprint (descriptor) and all fingerprints in your training set. The standard deviation of the force error can be modeled as a function of d_min (e.g., s = 49.1*d_min^2 - 0.9*d_min + 0.05), providing a confidence interval for the prediction [16]. This helps identify where the model is extrapolating and may be unreliable.

Q6: What are the primary speed vs. accuracy trade-offs when developing an MLFF? The goal is an MLFF that is as accurate as quantum mechanics (QM) and as fast as molecular mechanics (MM). Currently, the utility of MLFFs is "primarily bottlenecked by their speed (as well as stability and generalizability)" [17]. While many modern MLFFs surpass "chemical accuracy" (1 kcal/mol), they are still magnitudes slower than MM. The design challenge is to explore architectures that are faster, even if slightly less accurate, to be practical for large-scale biomolecular simulations [17].

# Experimental Protocols

# Protocol 1: Correcting DFT Formation Enthalpies with a Neural Network

This protocol details the methodology for training a neural network to correct systematic errors in DFT-calculated formation enthalpies, as presented in Scientific Reports [8].

1. Reference Data Curation

- Source experimental formation enthalpies (

H_f) for binary and ternary alloys from reliable databases. - Filter the data to exclude entries with missing or unreliable values.

- Compute the target variable for the ML model: the error or discrepancy between the DFT-calculated and experimentally measured

H_f.

2. Feature Engineering For each material in the dataset, construct an input feature vector that includes:

- Elemental Concentrations: The atomic fractions of each element (e.g.,

[x_A, x_B, x_C]) [8]. - Weighted Atomic Numbers: The product of concentration and atomic number for each element (e.g.,

[x_A*Z_A, x_B*Z_B, x_C*Z_C]) [8]. - Interaction Terms: Include pairwise (e.g.,

x_A*x_B) and three-body (e.g.,x_A*x_B*x_C) concentration products to help the model capture multi-element interactions [8]. - Normalization: Scale all input features to prevent variations in magnitude from affecting model performance.

3. Model Training and Validation

- Model Architecture: Implement a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) regressor. The referenced study used a network with three hidden layers [8].

- Training: Train the model in a supervised manner to predict the DFT-experiment discrepancy.

- Validation: Employ rigorous validation techniques to prevent overfitting:

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

# Protocol 2: Building a Data-Efficient Machine Learning Force Field

This protocol outlines the key steps for constructing an accurate MLFF with minimal quantum data, based on the BIGDML framework published in Nature Communications [15].

1. Generate Reference Data with Ab Initio Methods

- Perform accurate quantum many-body (QMB) calculations (or high-fidelity DFT) on a strategically selected set of atomic configurations.

- The training set should include a diverse range of structures (pristine bulk, surfaces, point defects, etc.) to cover the relevant chemical space [15] [16].

- For each configuration, extract the total energy and atomic forces.

2. Construct a Global Descriptor with Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC)

- Use a global descriptor that represents the entire supercell. The BIGDML model uses a periodic Coulomb matrix (

𝒟^(PBC)) [15]. - The matrix elements are defined by:

𝒟_ij^(PBC) = { 1/|r_ij - A mod(A⁻¹ r_ij)| if i≠j ; 0 if i=j }wherer_ijis the vector between atomsiandj, andAis the matrix of supercell translation vectors. This enforces the minimal-image convention for periodic systems [15].

3. Incorporate Physical Symmetries

- The model must be invariant to the full symmetry group of the crystal. This includes:

- Translation symmetry: Invariance to moving the entire system in space.

- Bravais symmetry: Invariance to the rotations and reflections of the crystal's point group [15].

- Building these symmetries directly into the model is a key reason for its high data efficiency.

4. Train the Model and Validate with Molecular Dynamics

- Train the model (using a method like kernel ridge regression) to learn the mapping from the global descriptor to the total energy and forces.

- Validate the resulting MLFF by running extensive path-integral molecular dynamics simulations and comparing the results against experimental observables or direct ab initio dynamics [15].

The following diagram illustrates the symmetric and non-symmetric approaches to building an MLFF:

# The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential computational "reagents" for ML-enhanced DFT and force field research.

| Item | Function / Definition | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation (XC) Functional | The core approximation in DFT that describes electron interactions; its unknown universal form is a primary source of error [13]. | Testing different XC approximations (e.g., PBE25) to gauge their impact on formation enthalpy errors [8]. |

| Quantum Many-Body (QMB) Data | Highly accurate quantum mechanical data used as a "gold standard" for training ML models. | Training an ML model to discover a more universal XC functional, bridging the accuracy of QMB with the speed of DFT [13]. |

| Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) | Molecular dynamics simulations where forces are computed on-the-fly using DFT. | Generating a diverse set of atomic configurations and their reference forces for training an MLFF [16]. |

| Global Descriptor (e.g., Periodic CM) | A numerical representation that encodes the entire atomic structure of a supercell, respecting periodicity [15]. | Serving as the input feature for the BIGDML model to capture long-range interactions without a cutoff [15]. |

| Atomic Fingerprints/Descriptors | Numerical vectors that encode the local atomic environment (radial and angular distributions) around each atom [16]. | Used in local MLFFs (like AGNI) as input for regression models to predict forces on individual atoms [16]. |

| Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) | A non-linear regression algorithm that uses the "kernel trick" to model complex relationships. | Predicting force components directly from atomic fingerprints in MLFFs for elemental systems [16]. |

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) and Surrogate Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using MLIPs over traditional computational methods? MLIPs function as data-driven surrogate models that predict potential energy surfaces with near ab initio accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost. They achieve this by leveraging machine learning to interpolate between reference quantum mechanical calculations, such as those from Density Functional Theory (DFT). This enables ab initio-quality molecular dynamics, structural optimization, and property prediction for large systems and long time-scales that are prohibitively expensive for direct DFT calculations [18] [19] [20].

Q2: My MLIP reports low average errors, but my molecular dynamics simulations show unphysical behavior. Why? Low average errors on a standard test set are necessary but not sufficient to guarantee reliable MD simulations. Conventional error metrics like RMSE for energies and forces are averaged over many configurations and may not reflect accuracy for critical, rare events like defect migrations or chemical reactions. The potential energy surface (PES) in these transition regions is exponentially sensitive to errors, which can lead to inaccurate simulation outcomes even with low overall RMSE. It is crucial to employ enhanced evaluation metrics specifically designed for atomic dynamics and rare events [21].

Q3: How can I model long-range electrostatic or dispersion interactions with standard MLIPs? Standard MLIPs often use a short-range cutoff, which limits their ability to model long-range interactions. This challenge is addressed by advanced MLIP architectures that incorporate explicit physics. Methods like the Latent Ewald Summation (LES) and others decompose the total energy into short-range and long-range components, using latent variables to represent atomic charges and compute long-range electrostatics via Ewald summation, all trained from energies and forces without needing explicit charge labels [22].

Q4: What is active learning, and why is it important for developing robust MLIPs? Active learning is a workflow where the MLIP itself identifies and queries new configurations that are underrepresented in its training data, particularly during MD simulations. This is vital because it is impossible to know a priori all the configurations a system will sample. On-the-fly active learning can trigger new ab initio calculations only when necessary, reducing the number of expensive reference calculations by up to 98% and ensuring the model remains accurate across a broader range of conditions [18].

Q5: Can a single MLIP be used for multiple different materials systems? Yes, multi-system surrogate models are feasible. Research has shown that models trained simultaneously on multiple binary alloy systems can achieve prediction errors that deviate by less than 1 meV/atom compared to models trained on each system individually. This suggests that MLIPs can learn a unified representation of chemical space, which is a step towards more universal potentials [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Transferability and Unphysical Predictions on Unseen Configurations

Problem: The MLIP performs well on its training and standard test sets but fails when simulating new conditions, such as different phases, defect dynamics, or surfaces.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: The training dataset lacks diversity and does not adequately represent the full configuration space of the intended application, including rare events and saddle points.

- Solution 1: Implement Active Learning. Integrate an on-the-fly learning protocol during MLIP-driven MD simulations. Use uncertainty quantification (e.g., ensemble-based methods or Bayesian errors) to detect high-uncertainty configurations and automatically add them to the training set [18] [23].

- Solution 2: Enhance Training with Physics-Informed Losses. Augment standard energy and force loss functions with physical constraints. For example, Physics-Informed Taylor Expansion (PITC) loss enforces energy-force consistency, which can reduce errors by up to a factor of two, improving generalizability even with sparse data [18].

- Solution 3: Systematically Expand Training Data. Use methods like non-diagonal supercells (NDSC) to efficiently sample diverse phonon modes and force constant matrices. For defect migration, explicitly include snapshots from ab initio MD trajectories of migrating vacancies or interstitials in the training pool [18] [21].

Issue 2: Inaccurate Modeling of Long-Range Interactions

Problem: The MLIP fails to reproduce properties in systems where electrostatics or van der Waals forces are significant, such as ionic materials, molecular crystals, or electrolyte interfaces.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: The model is based on a short-range descriptor and cannot capture interactions beyond its cutoff radius.

- Solution: Adopt a Long-Range Equipped MLIP. Select or develop an MLIP that incorporates long-range interactions. The following table compares two modern approaches [22]:

| Method | Key Mechanism | Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Latent Ewald Summation (LES) | Learns latent atomic charges from local features; long-range energy is computed via Ewald summation using these charges. | Does not require reference atomic charges for training; can predict physical observables like dipole moments. |

| 4G-HDNNP | Uses a charge equilibration scheme to assign environment-dependent atomic charges for electrostatic computation. | Explicitly models charge transfer based on atomic electronegativities. |

Issue 3: High Computational Cost of MLIP Inference

Problem: Molecular dynamics simulations with the MLIP are too slow, negating the computational savings over DFT.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: The model architecture might be overly complex (e.g., a very deep neural network or a high-order descriptor) for the application.

- Solution 1: Balance Complexity and Accuracy. Perform a Pareto front analysis to select a model that provides sufficient accuracy for your specific application without excessive computational overhead. Sometimes, a medium-precision DFT reference with an optimal descriptor order offers the best trade-off [18].

- Solution 2: Leverage Efficient Architectures and Hardware. Explore faster model architectures like MACE or Allegro. Run MD simulations on hardware accelerators (GPUs) for which the MLIP code is optimized [20].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking MLIP Performance on Atomic Dynamics

To reliably assess an MLIP's performance beyond average errors, follow this protocol focused on atomic dynamics [21]:

- Generate Specialized Test Sets: From ab initio MD simulations, create testing datasets that capture key rare events. Examples include:

- ( \mathcal{D}{\text{RE-VTesting}} ): 100+ snapshots of a migrating vacancy from high-temperature AIMD.

- ( \mathcal{D}{\text{RE-ITesting}} ): 100+ snapshots of a migrating interstitial.

- Compute Conventional Errors: Calculate the Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) of energies and forces on these test sets.

- Compute Performance Scores for Dynamics: Introduce metrics that focus on the atoms critical to the rare event:

- Identify the "RE migrating atom" in each snapshot (e.g., the atom jumping into a vacancy).

- Calculate the Force Performance Score (FPS) as the normalized error on these specific atoms: ( \text{FPS} = \frac{1}{N{\text{RE}}} \sum{i \in \text{RE}} \frac{|\mathbf{F}{i, \text{MLIP}} - \mathbf{F}{i, \text{DFT}}|}{|\mathbf{F}_{i, \text{DFT}}|} ).

- Validate with Target Properties: Use the MLIP in an MD simulation to compute a macroscopic property (e.g., diffusion coefficient, vacancy migration barrier) and compare it directly to the DFT or experimental value.

Protocol 2: Workflow for Developing a Transferable MLIP

The following diagram illustrates a robust, iterative workflow for developing a reliable MLIP, integrating active learning and rigorous validation.

Quantitative Error Analysis for MLIP Selection

The table below summarizes typical error ranges and benchmarks to aid in model selection and evaluation [18] [19] [21].

| Property / System | Target Accuracy (RMSE) | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (general) | < 5-10 meV/atom | ~7.5 meV/atom for Li-based cathodes [18]; ~10 meV/atom for binary alloys [19] |

| Forces (general) | < 0.05-0.15 eV/Å | ~0.21 eV/Å for MTP on Li-systems [18]; 0.03-0.4 eV/Å for various MLIPs on Si [21] |

| Forces (on RE atoms) | FPS < 0.3 | Critical metric; MLIPs with low general force error can have FPS > 0.5 on migrating atoms [21] |

| Structural (2D vdW) | Interlayer distance MAD < 0.11 Å [18] | Achievable with dispersion-corrected MLIPs [18] |

| Defect Migration Barrier | Error < 0.1 eV | Challenging; errors of ~0.1 eV vs. DFT are common even with relevant structures in training [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential "reagents" – key software components and methodologies – for constructing and applying MLIPs.

| Tool / Component | Function / Description | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Local Atomic Descriptors | Numerically represent an atom's chemical environment, ensuring invariance to rotation, translation, and atom permutation. | SOAP (Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions), MBTR (Many-Body Tensor Representation), MTP (Moment Tensor Potential) [18] [19]. |

| Regression Models | The machine learning core that maps atomic descriptors to energies and forces. | Neural Networks (e.g., Behler-Parrinello, ANI), Kernel Methods (e.g., GAP), Equivariant GNNs (e.g., NequIP, MACE, Allegro) [18] [20]. |

| Long-Range Interaction Methods | Architectures to model electrostatic and dispersion interactions beyond a local cutoff. | Latent Ewald Summation (LES), 4G-HDNNP, LODE, Ewald Message Passing [22]. |

| Active Learning Engines | Algorithms that manage on-the-fly querying of new ab initio calculations during simulation to improve model robustness. | Bayesian errors, ensemble uncertainty metrics [18]. Implemented in workflow managers like pyiron [23]. |

| Workflow Managers | Integrated platforms that automate the process of data generation, training, active learning, and validation. | pyiron: Accelerates prototyping and scaling of MLIP development workflows [23]. |

Key ML Methods and Their Real-World Applications in Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How can I reduce the computational cost of generating training data for my MLIP? A significant portion of MLIP development cost comes from generating reference data with Density Functional Theory (DFT). You can reduce this cost without severely impacting final model accuracy by:

- Using Lower-Precision DFT Calculations: Employing reduced plane-wave energy cut-offs and coarser k-point meshes for your training data generation can decrease computational cost by orders of magnitude. Research shows that with appropriate weighting of energies and forces during training, MLIPs built on lower-precision data can achieve accuracy close to those trained on high-precision data [24].

- Strategic Training Set Selection: Instead of using thousands of random configurations, use advanced sampling methods like DIRECT (DImensionality-Reduced Encoded Clusters with sTratified) sampling [25] or entropy maximization strategies [25] to select a smaller, more diverse, and representative set of structures for DFT calculations. This ensures robust model performance with a minimal training set.

FAQ 2: My MLIP does not generalize well to unseen atomic configurations. What can I do? Poor generalization often stems from insufficient coverage of the configuration space in your training data.

- Implement Robust Sampling: The DIRECT sampling workflow is designed to address this exact problem. By featurizing a large configuration space, reducing its dimensionality, and performing stratified sampling across the resulting clusters, you can create a training set that comprehensively covers the relevant structural and chemical space, leading to more transferable potentials [25].

- Incorporate Active Learning: Use Active Learning (AL) protocols where your MLIP is used to run simulations, and structures on which the model is uncertain (extrapolating) are automatically flagged for DFT calculation and added to the training set in an iterative loop [25].

FAQ 3: Which MLIP architecture should I choose to balance accuracy and computational cost? The choice involves a trade-off. Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based models like NequIP [26] [27], MACE [27], and the Cartesian Atomic Moment Potential (CAMP) [28] have demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy and high data efficiency. However, for applications where simulation speed is paramount, such as high-throughput screening or long-time-scale molecular dynamics, simpler, linear models like the quadratic Spectral Neighbor Analysis Potential (qSNAP) can be a more computationally efficient choice, even if their peak accuracy is lower [24].

FAQ 4: How can I model electronic properties or long-range interactions with MLIPs? Standard MLIPs are primarily designed for short-range interatomic interactions and total energy/force prediction.

- For Electronic Properties: Emerging models are being developed to unify interatomic potentials with electronic structure information. For example, UEIPNet is a GNN trained to predict not only energies and forces but also tight-binding Hamiltonians, enabling the study of strain-tunable electronic structures in materials like graphene and MoS₂ [29].

- For Long-Range Interactions: Be aware that most mainstream MLIPs use a local cutoff radius. Modeling long-range forces like electrostatics requires specialized architectural modifications, which is an active area of research and not yet a standard feature in all MLIP frameworks [20].

MLIP Performance and Computational Cost Comparison

The table below summarizes key characteristics of selected MLIP methods to aid in model selection.

| Model Name | Architecture Type | Key Features | Reported Strengths | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMP [28] | Graph Neural Network | Cartesian atomic moment tensors; Physically motivated, systematically improvable body-order. | Excellent performance across diverse systems (molecules, periodic, 2D); high accuracy and stability in MD. | |

| NequIP [26] | Equivariant GNN | E(3)-equivariant convolutions; uses higher-order geometric tensors. | Remarkable data efficiency (accurate with <1000 training structures); state-of-the-art accuracy. | Higher computational cost than simpler models [24]. |

| MACE [27] | Equivariant GNN | Higher-order body-order messages. | High performance on scientific benchmarks; pre-trained models available. | |

| qSNAP [24] | Descriptor-based (Linear) | Quadratic extension of bispectrum components; rotationally invariant. | High computational efficiency (fast training/evaluation); suitable for high-throughput/long MD. | Lower peak accuracy than state-of-the-art GNNs [24]. |

| UEIPNet [29] | Equivariant GNN | Predicts TB Hamiltonians and interatomic potentials. | Enables study of coupled mechanical-electronic responses. | Specialized for electronic property prediction. |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Robust MLIP with DIRECT Sampling

This protocol outlines the DIRECT sampling methodology [25] for generating a robust training dataset, which is crucial for developing accurate and transferable MLIPs while managing computational cost.

Objective: To select a minimal yet comprehensive set of atomic configurations for DFT calculations that maximally cover the configuration space of interest.

Procedure:

Generate a Candidate Configuration Space:

- Use ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD), or for greater speed, use a pre-trained universal potential (like M3GNet) to run MD simulations of your system at relevant thermodynamic conditions [25].

- Apply random atom displacements and lattice strains to crystalline systems to sample metastable and higher-energy states [25].

- This step should result in a large pool of candidate structures (e.g., 10,000-1,000,000).

Featurization/Encoding:

- Convert each atomic structure in the candidate pool into a fixed-length vector descriptor (feature).

- Recommended Method: Use a pre-trained graph deep learning model (e.g., M3GNet formation energy model) to generate a 128-element feature vector for each structure. This leverages learned, chemically relevant representations [25].

Dimensionality Reduction:

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the entire set of feature vectors.

- Retain the first

mprincipal components (PCs) that have eigenvalues greater than 1 (Kaiser's rule) to create a lower-dimensional representation of your configuration space [25].

Clustering:

- Use a clustering algorithm like BIRCH on the

m-dimensional PC space to group structures with similar features. Weight each PC by its explained variance. - The number of clusters

nis a user choice, balancing desired coverage and computational budget for subsequent DFT.

- Use a clustering algorithm like BIRCH on the

Stratified Sampling:

- From each of the

nclusters, selectkrepresentative structures. - For

k=1, choose the structure closest to the cluster centroid. - This yields your final, robust training set of

M ≤ n × kstructures for DFT calculation.

- From each of the

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The table below lists key software tools and "reagents" essential for MLIP development and application.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| VASP [24] | Software Package | High-accuracy DFT code used to generate reference energies and forces for training data. |

| mlip Library [27] | Software Library | A consolidated environment providing pre-trained models (MACE, NequIP, ViSNet) and tools for efficient MLIP training and simulation. |

| FitSNAP [24] | Software Plugin | Used for training linear MLIP models like SNAP and qSNAP. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [27] | MD Wrapper / Library | A Python package used to set up, run, and analyze atomistic simulations; often integrated with MLIPs. |

| DIRECT Sampling [25] | Methodology / Algorithm | A strategy for selecting a diverse and robust training set from a large configuration space, improving MLIP generalizability. |

| SPICE Dataset [27] | Training Dataset | A large, chemically diverse dataset of quantum mechanical calculations used for training general-purpose MLIPs, especially for biochemical applications. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of using the density matrix as a target for machine learning in electronic structure calculations?

Learning the one-electron reduced density matrix (1-RDM) instead of just the total energy allows for the computation of a wide range of molecular observables without the need for separate, specialized models. From the predicted density matrix, you can directly calculate not only the energy and atomic forces but also other properties like band gaps, Kohn-Sham orbitals, dipole moments, and polarizabilities. This approach bypasses the computationally expensive self-consistent field procedure [30].

Q2: My ML-predicted density matrix leads to inaccurate forces. What could be the issue?

This is often related to the accuracy of the predicted density matrix itself. For forces to be reliable, the density matrix must be learned to a very high degree of accuracy, comparable to that achieved by standard electronic structure software. Small deviations in the density matrix can lead to significant errors in force calculations. You can troubleshoot by:

- Verifying the quality and size of your training set.

- Ensuring your model is learning the rigorous map, (\hat{\gamma}[\hat{v}]), between the external potential and the density matrix [30].

- Considering the "γ + δ-learning" approach, where a second machine-learning model is used to directly learn the map from the density matrix to the energy and forces [30].

Q3: How does the "nearsightedness" property of the density matrix benefit deep learning models?

The density matrix (\rho(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}')) decays significantly with the distance (|\mathbf{r}' - \mathbf{r}|). When represented in a localized basis set (like pseudo-atomic orbitals), this means the matrix (\rho{\alpha\beta}) is sparse. A deep learning model, such as a message-passing graph neural network, can leverage this by only needing to predict the elements (\rho{\alpha\beta}) for which the basis functions (\phi\alpha) and (\phi\beta) overlap. This reduces the complexity of the learning task and improves the efficiency and generalizability of the model [31].

Q4: What is the difference between "γ-learning" and "γ + δ-learning"?

These are two distinct machine learning procedures outlined for surrogate electronic structure methods:

- γ-learning (Map 1): The ML model learns the direct map from the external potential, (\hat{v}), to the 1-RDM, (\hat{\gamma}). The energy and forces are then computed from this predicted (\hat{\gamma}) using standard quantum chemistry expressions [30].

- γ + δ-learning (Map 2): The ML model learns the map from the external potential, (\hat{v}), to the electronic energy, (E), and forces, (F), directly. This approach can be necessary for post-Hartree-Fock methods where no pure functionals of the 1-RDM exist to deliver the energy [30].

Q5: Can a machine-learned density matrix be used for methods beyond standard Kohn-Sham DFT?

Yes. The one-body reduced density matrix is a fundamental quantity in many electronic structure methods. A accurately learned density matrix has broad potential application in hybrid DFT functionals, density matrix functional theory, and density matrix embedding theory [31].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Kernel Ridge Regression for γ-Learning

This protocol details the supervised learning approach for mapping the external potential to the density matrix [30].

Data Generation:

- Use a standard electronic structure software (e.g., QMLearn) to generate a training set.

- For each molecular geometry, compute and store the external potential matrix elements, ({\hat{v}}{i}), and the corresponding one-electron reduced density matrix, ({\hat{\gamma}}{i}), in a Gaussian-type orbital (GTO) basis.

- Ensure the training set covers a diverse and representative range of nuclear configurations.

Model Training:

- Employ Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) with a linear kernel, (K({\hat{v}}{i},\, {\hat{v}}{j}) = {{{{{{{\rm{Tr}}}}}}}}[{\hat{v}}{i}{\hat{v}}{j}]).

- Learn the regression coefficients ({\hat{\beta}}{i}) to construct the model: (\hat{\gamma}[\hat{v}]=\sum{i}^{{N}{{{{{{{{\rm{sample}}}}}}}}}}{\hat{\beta }}{i}K({\hat{v}}_{i},\, \hat{v})).

Prediction and Validation:

- For a new molecular structure, compute its external potential (\hat{v}) in the same GTO basis.

- Use the trained KRR model to predict the density matrix (\hat{\gamma}).

- Validate the model by comparing predicted properties (e.g., energy, charge density) against calculations from the reference electronic structure method.

Protocol 2: DeepH-DM Workflow for Sparse Density Matrix Prediction

This protocol utilizes a deep neural network to learn the sparse representation of the density matrix in a localized basis set [31].

Input Representation:

- Represent the atomic structure as a graph, where nodes are atoms and edges connect atoms within a defined nearsightedness cutoff, (R_{\text{N}}).

- Use atom-centered descriptors that respect the physical symmetries of the system (translational, rotational, and permutational invariance).

Network Architecture and Training:

- Implement a message-passing graph neural network (e.g., based on the DeepH-2 architecture).

- Train the network to predict the elements of the density matrix, (\rho{\alpha\beta}), only for pairs of overlapping basis functions (\phi\alpha) and (\phi_\beta).

- Leverage the "quantum nearsightedness principle" to ensure the model's output is physically constrained and sparse.

Property Calculation:

- Use the predicted sparse density matrix to compute the electron density via (n(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{\alpha\beta}\rho{\alpha\beta}\phi{\alpha}^{*}(\mathbf{r})\phi{\beta}(\mathbf{r})).

- The electron density can then be used to compute the Hamiltonian and other electronic properties in a single, non-self-consistent step.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Quantities in Deep-Learning Electronic Structure

This table compares the three fundamental quantities that can be targeted by machine learning models to represent DFT electronic structure, highlighting their key characteristics and advantages [31].

| Fundamental Quantity | Data Structure | Key Advantage | Computational Cost for Deriving Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hamiltonian ((H_{\alpha\beta})) | Matrix | Efficient for deriving band structures and Berry phases [31]. | Lower cost for topological and response properties [31]. |

| Density Matrix ((\rho_{\alpha\beta})) | Matrix | Sparse representation; efficient derivation of charge density and polarization [31]. | Lower cost for charge-derived properties; (O(N^3)) to derive from (H) [31]. |

| Charge Density ((n(\mathbf{r}))) | Real-space grid | Directly visualizable electron distribution. | Large data size; properties often require further processing [31]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions

A list of essential computational "reagents" and tools for developing machine learning models for electronic structure.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs) | A basis set used to represent the density matrix and external potential, simplifying the calculation of expectation values and handling of molecular symmetries [30]. |

| Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) | A supervised machine learning algorithm used to learn the non-linear map from the external potential to the density matrix [30]. |

| Message-Passing Graph Neural Network | A deep learning architecture that exploits the nearsightedness of electronic structure by processing local atomic environments to predict the density matrix [31]. |

| Pseudo-Atomic Orbitals (PAO) | Atom-centered, localized basis functions with a finite cutoff radius, which ensure the sparsity of the density matrix and Hamiltonian [31]. |

Workflow Visualization

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and materials science, but its accuracy depends entirely on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which accounts for quantum mechanical electron interactions. The quest for a universal, accurate functional has been a long-standing challenge [2]. Machine learning (ML) now offers a transformative approach by learning the XC functional directly from high-accuracy data, moving beyond traditional human-designed approximations to create more accurate and efficient functionals [32] [2] [33].

This paradigm involves learning a mapping from the electron density (or its descriptors) to the XC energy, effectively using data to discover the intricate form of the universal functional [32]. The primary goal within the context of reducing computational cost is to lift the accuracy of efficient baseline functionals towards that of more accurate, expensive quantum chemistry methods, while retaining their favorable scaling [32].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Concepts & Solutions

Table 1: Essential Components for ML-Derived XC Functionals

| Component | Function & Purpose | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Functional | Provides an initial, computationally efficient but approximate XC energy. The ML model learns a correction to this baseline. | PBE [32] |

| Density Descriptors | Mathematical representations of the electron density that encode physical symmetries (rotation, translation, permutation invariance) for the ML model. | Atom-centered basis functions (e.g., spherical harmonics & radial functions) [32], AGNI atomic fingerprints [9] |

| ML Model Architecture | The algorithm that learns the non-linear mapping from density descriptors to the XC energy correction. | Behler-Parrinello neural networks [32], Differentiable Quantum Circuits (DQCs) [34], Deep Neural Networks [9] [33] |

| High-Accuracy Training Data | Reference data from highly accurate (but expensive) quantum methods, used to train the ML model. The functional's accuracy is bounded by the quality of this data. | Coupled-Cluster (CCSD(T)) [32], accurate wavefunction methods (e.g., for atomization energies) [2] [33] |

| Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Engine | The DFT software that performs the self-consistent cycle, updated to use the ML-functional and its potential. | VASP [9], NeuralXC framework [32] |

Table 2: Representative ML-XC Functionals and Their Performance

| Functional Name | Key Innovation | Reported Performance & Cost |

|---|---|---|

| NeuralXC [32] | ML functional built on top of a baseline (e.g., PBE), designed for transferability across system sizes and phases. | Outperforms baseline for water; approaches CCSD(T) accuracy; maintains baseline's computational efficiency. |

| Skala [2] [33] | Deep-learning-based functional trained on an unprecedented volume of high-accuracy data; learns features directly from data instead of using hand-designed ones. | Reaches chemical accuracy (~1 kcal/mol) for atomization energies of small molecules; computational cost is similar to semi-local meta-GGAs for large systems [33]. |

| Quantum-Enhanced Neural XC [34] | Uses quantum neural networks (QNNs) and differentiable quantum circuits (DQCs) to represent the XC functional. | Yields energy profiles for H$2$ and H$4$ within 1 mHa of reference data; achieves chemical precision on unseen systems with few parameters. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Developing a Neural Network-Based XC Functional

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating an ML-based XC functional, such as NeuralXC [32].

Data Generation and Feature Engineering:

- Generate Reference Data: Perform calculations on a diverse training set (e.g., small molecules, clusters) using a high-accuracy method like CCSD(T) to obtain total energies.

- Compute Baseline Density: For each structure in the training set, perform a DFT calculation using an efficient baseline functional (e.g., PBE) to obtain the electron density.

- Project Density onto Descriptors: Represent the electron density by projecting it onto a set of atom-centered, rotationally invariant basis functions. For an atom I at position RI, the descriptor is calculated as: ( {d}{nl}^{I} = \sum{m=-l}^{l} \left[ \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \, \psi{nlm}^{\alphaI}(\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}I) \, d\mathbf{r} \right]^2 ) where ( \psi{nlm} ) is a product of a radial basis function and a real spherical harmonic [32].

Model Training:

- Define Model Architecture: Use a permutationally invariant neural network (e.g., Behler-Parrinello type). The input is the collection of descriptors ( {\mathbf{d}^I} ) for all atoms, and the output is the total ML energy, expressed as a sum of atomic contributions: ( E{ML}[\rho] = \sumI \epsilon{\alphaI}(\mathbf{d}^I) ) [32].

- Train the Model: Train the neural network to minimize the difference between the predicted total energy (( E{base} + E{ML} )) and the high-accuracy reference energy.

Functional Deployment in SCF Calculations:

- Derive the Potential: The functional derivative of the ML energy ( E{ML} ) with respect to the density must be computed to obtain the ML XC potential ( V{ML}[\rho] = \frac{\delta E_{ML}[\rho]}{\delta \rho(\mathbf{r})} ) for use in the Kohn-Sham equations [32].

- Run Self-Consistent Calculations: Integrate the ML functional and its potential into a DFT code. The SCF cycle then proceeds by using this new potential to update the electron density until convergence is achieved.

Workflow for Developing an ML-Based XC Functional

Protocol 2: End-to-End DFT Emulation via Charge Density Prediction

This protocol describes an alternative, comprehensive ML-DFT framework that bypasses the explicit Kohn-Sham equation by directly predicting the electron density [9].

Input Representation: Encode the atomic structure using a rotationally and permutationally invariant fingerprinting scheme (e.g., AGNI atomic fingerprints) that describes the chemical environment of each atom.

Charge Density Prediction (Step 1):

- Train a deep neural network to map the atomic fingerprints directly to a representation of the all-electron charge density.

- The model can learn to represent the density using an optimal set of atom-centered Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs), with coefficients and exponents learned from the data [9].

Property Prediction (Step 2):

- Use the predicted electronic charge density, together with the atomic structure fingerprints, as a joint input to subsequent neural networks.

- These networks then predict a host of other electronic and atomic properties, including the density of states, total potential energy, atomic forces, and stress tensor [9].

This two-step approach emulates the complete DFT workflow with linear scaling and a small prefactor, offering massive speedups while maintaining accuracy for molecular dynamics simulations [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My ML-functional performs well on the training set but fails on new, larger molecules. How can I improve its transferability?

A: This is a common issue related to overfitting and the descriptors used.

- Solution 1: Use a "Delta-Learning" Approach. Frame the ML model to learn the correction to a standard baseline functional (like PBE) rather than the total energy itself. This allows the model to focus on the missing physics and often generalizes better [32].

- Solution 2: Employ Physically Meaningful Density Representations. Instead of using the raw electron density, project it onto atom-centered basis functions that are inherently rotationally and translationally invariant. Using the "neutral density" (the full density minus superposition of atomic densities) can be particularly beneficial as it is smoother and integrates to zero, improving transferability across different chemical environments [32].

- Solution 3: Expand Training Data Diversity. Ensure your training set is not limited to a single class of systems. Include a wide variety of molecular sizes, bonding types, and elements to help the model learn a more universal representation of the XC functional [2] [33].

Q2: The computational cost of my ML-functional is too high for practical SCF calculations. Where are the bottlenecks and how can I address them?

A: The cost primarily comes from evaluating the ML model and its functional derivative for the density at every SCF step.

- Solution 1: Leverage Efficient Atom-Centered Descriptors. Using atom-centered representations and decomposing the energy into atomic contributions allows the computational cost to scale linearly with the number of atoms, which is a significant advantage [32] [9].

- Solution 2: Optimize Model Architecture. Simpler neural networks or exploring different model types can reduce inference time. Note that some advanced ML functionals, like Skala, are designed to have a computational cost comparable to semi-local meta-GGAs, especially for systems with over 1,000 occupied orbitals [33].

- Solution 3: Verify the Cost vs. Accuracy Gain. Compare the cost of your ML-DFT calculation to that of the high-accuracy method you are emulating (e.g., CCSD(T)). Even a 10x cost increase over standard DFT can be a net win if it avoids calculations that are 1000x more expensive.

Q3: How can I ensure my learned XC functional produces physically correct and stable results?

A

Ensuring Physically Correct ML Functionals

A: Guaranteeing physicality is a central research area. The following strategies can help:

- Solution 1: Incorporate Exact Physical Constraints. During the model design, enforce known exact constraints of the true XC functional (e.g., specific scaling behaviors). Some modern ML functionals are built to satisfy these constraints [33].

- Solution 2: Train Using Potentials, Not Just Energies. Using the XC potential (the functional derivative of the XC energy) as part of the training signal provides a much stronger foundation. Potentials are more sensitive to local changes in the density and help the model learn a more physically correct functional form [13].

- Solution 3: Extensive Validation. Always test the functional on well-established benchmark datasets that were not part of the training. Check for unphysical behavior, such as spurious oscillations in the potential or catastrophic failure on simple, known systems [2].

Q4: What are the data requirements for training a generalizable ML-functional, and how can I generate this data?

A: Data requirements are significant, but strategies exist to manage them.

- Requirement: A large and chemically diverse set of molecular structures with their corresponding highly accurate energies (and optionally, potentials) is needed. The "Skala" functional, for instance, was trained on about 150,000 accurate energy differences [33].

- Generation Strategy:

- Collaborate with Experts: Partner with research groups specializing in high-accuracy wavefunction methods to generate reliable data [2].

- Focus on Diversity: Generate structures that sample different bond types, geometries, and elements relevant to your target application space. Using snapshots from molecular dynamics simulations at high temperatures is one effective way to create diverse configurations [9].

- On-the-Fly Learning: For force fields, an "on-the-fly" learning scheme can be used. In this approach, an MD simulation is run, and the algorithm decides when the error of the ML model is large enough to warrant an new, expensive ab initio calculation, which is then added to the training set. This builds a minimal but effective training dataset automatically [35].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Prediction Accuracy for Stable Materials

- Problem: The model's hit rate (precision for predicting stable crystals) is low, particularly for systems with more than four unique elements.

- Diagnosis: This often indicates insufficient diversity in the training data or a model that has not been scaled adequately. The model may not have encountered enough examples of complex chemical environments during training.

- Solution:

- Implement an active learning pipeline where the model's uncertain predictions are validated with DFT calculations and the results are fed back into the training set [36].

- Ensure your training dataset includes a significant number of high-entropy systems or systems generated via random structure searches to broaden chemical diversity [36].

- Scale up the model architecture and training data size. Performance in predicting formation energies has been shown to improve as a power law with increased data [36].

Issue 2: Unphysical Predictions in Electron Density

- Problem: The predicted electron density or derived properties violate known physical constraints.

- Diagnosis: The machine-learned functional may be learning spurious correlations from the data without incorporating physical laws.

- Solution:

- Incorporate exact physical constraints into the model's loss function during training. This guides the learning process to respect fundamental quantum mechanics [2].

- Use potentials (energy derivatives) in addition to energies for training. This provides a stronger foundation and helps the model capture subtle changes more effectively, preventing unphysical results [13].

- Project the predicted atom-based charge densities onto a grid and compare directly with high-fidelity reference DFT data to ensure accuracy in delocalized regions [9].

Issue 3: High Computational Cost of Charge Density Prediction

- Problem: The model for predicting the electronic charge density is too slow, negating the computational benefits of ML-accelerated DFT.

- Diagnosis: Using a grid-based scheme for charge density prediction, while accurate, is computationally expensive for large databases [9].

- Solution:

- Adopt an atom-centered representation of the charge density. Use a basis set like Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs), where the model learns the optimal basis parameters from data. This significantly reduces computational cost [9].

- Ensure the model architecture is designed for efficiency, such as using message-passing graph neural networks that scale linearly with system size [9] [36].

Issue 4: Model Fails to Generalize to Larger Systems

- Problem: A model trained on small molecules performs poorly when applied to polymer chains or crystals.

- Diagnosis: The model lacks transferability, often due to atomic fingerprints or descriptors that do not capture long-range interactions adequately.

- Solution:

- Employ graph neural networks (GNNs) that can naturally handle scale and model interactions in larger systems by passing messages between atoms [36].