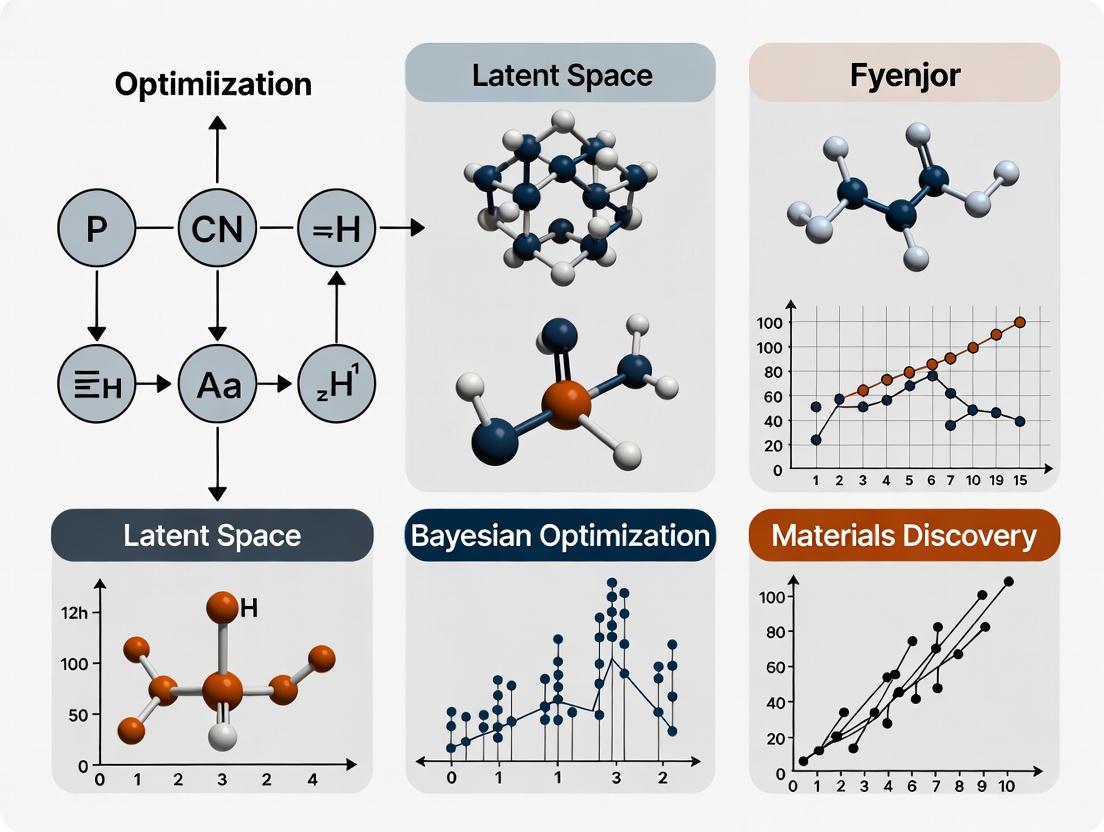

Latent Space Bayesian Optimization: Accelerating Advanced Materials and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative potential of Bayesian Optimization (BO) within latent spaces for accelerating the discovery and design of novel materials and molecules.

Latent Space Bayesian Optimization: Accelerating Advanced Materials and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of Bayesian Optimization (BO) within latent spaces for accelerating the discovery and design of novel materials and molecules. We first establish the foundational principles of BO and the necessity of latent representations for navigating complex, discrete scientific spaces. The core of the article details cutting-edge methodologies, including graph neural network encodings of chemical space and multi-level optimization frameworks that balance exploration and exploitation. We further address critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as the curse of dimensionality from expert knowledge and the selection of surrogate models. Finally, the article provides a rigorous validation of these techniques through benchmarking studies and comparative analyses of multi-task and deep Gaussian processes against conventional approaches, offering a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement these efficient optimization strategies.

The Foundations of Bayesian Optimization and Latent Space Representations

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful, sample-efficient strategy for optimizing black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate, a common scenario in materials science research and development [1]. By building a probabilistic surrogate model of the objective function and using an acquisition function to guide the search, BO can find optimal solutions with a minimal number of experiments [2]. This approach has become a cornerstone technique for accelerating materials discovery and design, enabling researchers to navigate complex, high-dimensional design spaces that include compositions, processing parameters, and microstructural variables [1] [3].

Recent advances have extended BO capabilities to handle the mixed quantitative and qualitative variables inherent in materials design problems [2]. Furthermore, the integration of BO with latent space representations has emerged as a particularly promising direction, allowing for the optimization of structured and discrete materials such as molecules and crystal structures by working in a continuous, meaningful latent space [4] [5]. This primer introduces the core concepts of Bayesian optimization with a specific focus on its application in materials science, detailing practical protocols and highlighting how latent space approaches are transforming the field.

Fundamental Principles and Algorithmic Workflow

Core Components of Bayesian Optimization

The Bayesian Optimization framework consists of two fundamental components:

Surrogate Model: Typically a Gaussian Process (GP), which provides a probabilistic distribution over the possible functions that fit the observed data. For a set of observations, the GP can make predictions for new points with associated uncertainty estimates [6]. The model uses a covariance function (kernel) to capture the similarity between data points, which is crucial for modeling complex material property relationships [2].

Acquisition Function: A criterion that uses the surrogate model's predictions to select the next point to evaluate by balancing exploration (sampling in uncertain regions) and exploitation (sampling where the model predicts high performance) [6]. Common acquisition functions include Expected Improvement (EI), Knowledge Gradient, and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [7].

The BO Cycle in Materials Design

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative BO process adapted for materials design:

Advanced BO Methodologies for Materials Science

Latent Space Bayesian Optimization

Latent Space BO addresses the challenge of optimizing structured, discrete, or hard-to-enumerate materials search spaces by leveraging deep generative models like variational autoencoders (VAEs) [4] [5]. These models map complex structured inputs (e.g., molecules, crystal structures) into a continuous latent space where standard BO techniques can be applied more effectively.

Key Advancement: The Correlated latent space Bayesian Optimization (CoBO) method introduces Lipschitz regularization, loss weighting, and trust region recoordination to minimize the inherent discrepancy between the latent space and objective function space, particularly around promising areas [4]. This approach has demonstrated strong performance in discrete data optimization tasks such as molecule design and arithmetic expression fitting.

Implementation Consideration: A significant challenge is that the latent space often remains high-dimensional. The LOL-BO algorithm adapts trust region concepts to the structured input setting by reformulating the encoder to serve both as a global encoder for the deep autoencoder and as a deep kernel for the surrogate model within a trust region, better aligning local optimization in the latent space with local optimization in the input space [5].

Multi-Objective and Target-Oriented BO

Materials design frequently involves balancing multiple, often competing objectives. Multi-objective BO identifies Pareto-optimal solutions representing the best trade-offs between objectives [1] [8].

Hierarchical Multi-Objective Optimization: The BoTier framework implements a tiered objective structure that reflects practical experimental hierarchies, where primary objectives (e.g., reaction yield) are prioritized over secondary objectives (e.g., minimizing expensive reagent use) [8]. This approach uses a composite scalarization function that ensures subordinate objectives contribute only after superordinate objectives meet satisfaction thresholds.

Target-Oriented Optimization: Many materials applications require achieving specific property values rather than simply maximizing or minimizing properties. Target-oriented BO (t-EGO) employs a target-specific Expected Improvement (t-EI) acquisition function that samples candidates based on their potential to reduce the difference from the target value, significantly improving efficiency for finding materials with predefined properties [7].

Handling Mixed Variable Types

Materials design naturally involves both quantitative variables (e.g., temperatures, concentrations) and qualitative variables (e.g., material types, processing methods). The Latent Variable GP (LVGP) approach maps qualitative factors into underlying numerical latent variables with strong physical justification, providing an inherent ordering and structure that captures complex correlations between qualitative levels [2]. This method enables more accurate modeling and efficient optimization compared to traditional dummy variable encoding approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Multi-Objective Optimization of Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys

This protocol outlines the methodology for applying BO to design magnesium alloys with optimized mechanical properties and corrosion resistance [1].

- Objective: Synergistically optimize Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS), Elongation (EL), and Corrosion Potential (Ecorr) of biodegradable Mg alloys.

- Design Variables: Alloy compositions (wt.%) and process parameters (extrusion temperature, extrusion ratio).

- Data Collection: Compile dataset from published literature and experimental results.

- Model Training: Train machine learning models (e.g., XGBoost) on the collected data to predict properties based on compositions and process parameters.

- BO Implementation:

- Construct multi-objective BO framework using Gaussian Process surrogates.

- Employ acquisition function to navigate the high-dimensional design space.

- Iteratively suggest candidate alloys for experimental validation.

- Experimental Validation: Prepare suggested alloy compositions, conduct tensile tests, and perform electrochemical measurements to verify predictions.

- Model Interpretation: Apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to interpret the machine learning model and identify critical factors influencing properties.

Protocol: Microstructure-Aware Bayesian Materials Design

This protocol incorporates microstructural descriptors as latent variables to enhance the mapping from design variables to material properties [3].

- Objective: Optimize material properties by explicitly incorporating microstructural information in the BO framework.

- Microstructural Characterization: Quantify microstructural features using descriptors such as grain size, phase fractions, and spatial correlations.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Active Subspace Method to identify key subspaces within the latent microstructural space that most influence property variability.

- Latent-Space-Aware BO: Integrate reduced microstructural descriptors as latent variables in the Gaussian Process model to improve probabilistic modeling and design performance.

- Validation: Compare optimization performance between traditional (microstructure-agnostic) and microstructure-aware BO approaches.

Application Examples and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Bayesian Optimization Applications in Materials Science

| Material System | Design Variables | Target Properties | BO Method | Key Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Mg Alloys | Composition, Extrusion parameters | UTS, EL, Ecorr | Multi-objective BO | Identified high-performance alloys; Experimental validation | [1] |

| Shape Memory Alloys | Composition | Transformation temperature | Target-oriented BO (t-EGO) | Ti0.20Ni0.36Cu0.12Hf0.24Zr0.08 with ΔT = 2.66°C from target in 3 iterations | [7] |

| Quasi-random Solar Cells | Pattern parameters, Material selection | Light absorption | LVGP-BO | Concurrent materials selection and microstructure optimization | [2] |

| Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Perovskites | Material constituents | Device performance | LVGP-BO | Combinatorial search for optimal compositions | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BO-Driven Materials Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Elemental Metal Powders | Starting materials for alloy synthesis via arc melting or powder metallurgy | Mg alloy development [1] |

| High-Temperature Furnaces | For homogenization and thermal processing of alloy samples | Control of microstructure evolution [3] |

| Extrusion Equipment | Thermo-mechanical processing to refine microstructure and improve properties | Mg alloy processing [1] |

| Electrochemical Workstation | Corrosion potential (Ecorr) measurements to assess corrosion resistance | Evaluation of biodegradable alloys [1] |

| Universal Testing Machine | Mechanical property characterization (UTS, Elongation) | Validation of predicted mechanical properties [1] |

| Microscopy Equipment | Microstructural characterization (grain size, phase distribution) | Quantification of microstructural descriptors [3] |

Implementation Considerations and Computational Framework

Software and Computational Tools

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow integrating various software tools for implementing BO in materials research:

Best Practices and Practical Recommendations

Initial Experimental Design: Begin with space-filling designs (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to build an initial surrogate model when no prior data exists [2].

Kernel Selection: Choose appropriate covariance functions for the Gaussian Process based on the nature of the design space. Matérn kernels often work well for materials properties with moderate smoothness.

Dimensionality Management: For high-dimensional problems (e.g., multi-component alloys), incorporate dimensionality reduction techniques or active subspaces to improve BO efficiency [3].

Constraint Handling: Incorporate known physical constraints or domain knowledge directly into the BO framework to avoid exploring infeasible regions of the design space.

Batch Optimization: When parallel experimental capabilities exist, implement batch BO approaches to suggest multiple candidates for simultaneous evaluation.

Uncertainty Quantification: Leverage the probabilistic nature of BO to quantify and communicate uncertainty in predictions, which is crucial for experimental planning and decision-making.

Bayesian Optimization represents a paradigm shift in materials discovery, enabling efficient navigation of complex design spaces with minimal experimental iterations. The integration of latent space approaches further extends these capabilities to structured materials design problems, offering powerful new strategies for accelerating the development of advanced materials with tailored properties.

Why Latent Space? Navigating High-Dimensional and Discrete Scientific Landscapes

Latent spaces—low-dimensional representations learned from high-dimensional data—are revolutionizing how researchers navigate complex scientific problems. In fields ranging from materials science to drug development, these compressed embeddings capture the essential, underlying features of data, transforming intractable problems into manageable ones. The core premise is that while scientific data may be high-dimensional and discrete in its raw form (e.g., molecular structures, microstructural images, or clinical patient profiles), its true structure often resides on a much lower-dimensional manifold. By projecting this data into a latent space, scientists can perform efficient optimization, identify meaningful patterns, and make predictions that would be impossible in the original high-dimensional space. This approach is particularly powerful when integrated with Bayesian optimization (BO), creating a framework for data-driven experimental design and discovery that explicitly accounts for uncertainty in sparse-data regimes common in scientific research.

Theoretical Foundations

The Mathematical Framework of Latent Space Embeddings

Latent space approaches fundamentally rely on learning a mapping from a high-dimensional observation space (\mathcal{X} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d) to a lower-dimensional latent space (\mathcal{Z} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^{d'}) where (d' \ll d). This mapping (f: \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{Z}) preserves essential structural relationships while discarding redundant information. In scientific applications, this process typically involves either:

- Dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA, autoencoders) that compress while preserving variance

- Generative model embeddings (e.g., VAEs, diffusion models) that learn the data distribution

- Task-specific embeddings optimized for particular scientific objectives

The mathematical power of this approach stems from the manifold hypothesis, which posits that most high-dimensional scientific data actually lies on or near a low-dimensional manifold. Latent space identification effectively parameterizes this manifold, enabling efficient navigation and optimization.

Bayesian Optimization in Latent Space

Bayesian optimization provides a principled framework for global optimization of expensive black-box functions. When combined with latent space representations, it becomes particularly powerful for scientific applications. The standard BO process in latent space involves:

- Learning a latent representation (z = f(x)) of the scientific data

- Constructing a probabilistic surrogate model (typically Gaussian Process) in latent space

- Using an acquisition function to select promising candidates for evaluation

- Updating the model with new data and repeating

This approach addresses the "curse of dimensionality" that plagues high-dimensional optimization, as the surrogate model operates in a lower-dimensional space where data is less sparse and relationships are more easily learned.

Applications Across Scientific Domains

Materials Science and Microstructure Design

In materials science, latent space approaches have enabled microstructure-aware design, moving beyond traditional composition-property relationships to explicitly incorporate structural information.

Table 1: Latent Space Applications in Materials Design

| Application Area | Key Latent Variables | Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermoelectric Materials | Grain size, phase distribution, defect concentration | Enhanced conversion efficiency | [3] |

| Advanced Alloys | Grain boundaries, phase distributions | Improved strength-toughness balance | [3] |

| Polymer-Bonded Explosives | Statistical microstructure descriptors | Accurate shock prediction with reduced simulation | [3] |

The microstructure-aware Bayesian materials design framework demonstrates how latent microstructural descriptors create a more direct pathway through the Process-Structure-Property-Performance (PSPP) chain, traditionally a fundamental challenge in materials science [3]. By treating microstructural features as tunable design parameters rather than emergent by-products, researchers can more efficiently navigate toward materials with desired properties.

Drug Development and Treatment Personalization

In pharmaceutical research, latent space approaches have shown particular promise for treatment personalization, especially for complex disorders where traditional subgrouping approaches fail.

Table 2: Treatment Selection Performance in Major Depressive Disorder

| Method | Personalization Paradigm | Improvement over Random Allocation | Patient Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Personalized | Individual-level ITE estimation | Not specified | [9] |

| Sub-grouping | Cluster-level optimization | Not specified | [9] |

| DPNN (Latent-Space Prototyping) | Balanced personalization & prototyping | 8% absolute, 23% relative | 4,754 MDD patients [9] |

The Differential Prototypes Neural Network (DPNN) exemplifies how latent space prototyping strikes a balance between fully personalized and sub-grouping paradigms [9]. By identifying "actionable prototypes" in latent space—groups that differ in their expected treatment responses—this approach achieved clinically significant improvements for Major Depressive Disorder patients, addressing the heterogeneity that has long challenged psychiatric treatment optimization.

Molecular Design and Protein Engineering

Modern generative AI models have created new opportunities for latent space optimization in molecular design. Sample-based approaches like diffusion and flow matching models can generate diverse molecular structures, while latent space optimization enables efficient navigation toward molecules with desired properties.

The surrogate latent space approach allows researchers to define custom latent spaces using example molecules, creating low-dimensional Euclidean embeddings that maintain biological relevance while being convenient for optimization tasks [10]. This method has shown particular promise in protein generation, where it enabled successful generation of proteins with greater length than previously feasible, demonstrating the scalability of latent space approaches for complex biomolecular design problems.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Microstructure-Aware Bayesian Optimization for Materials Design

Objective: Identify material processing parameters that yield optimal properties by incorporating microstructural descriptors as latent variables.

Materials and Reagents:

- Material precursor compounds (composition-dependent)

- Processing equipment (e.g., furnaces, mills)

- Characterization tools (e.g., SEM, EBSD, XRD)

- Computational resources for simulation and modeling

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Feature Extraction

- Collect historical data on processing parameters, microstructural features, and properties

- Extract relevant microstructural descriptors using image analysis (grain size, phase distribution, etc.)

- Normalize all features to zero mean and unit variance

Latent Space Construction

- Apply Active Subspace Method to identify dominant directions in microstructure space

- Construct latent variables (z = W^T \cdot \text{microstructure features}) where (W) contains eigenvectors of the gradient covariance matrix

- Validate latent space preservation of property-relevant information

Bayesian Optimization Loop

- Initialize Gaussian Process surrogate model linking processing parameters to properties through latent space

- For each iteration: a. Select next processing parameters using Expected Improvement acquisition function b. Execute experimental processing (e.g., heat treatment, deformation) c. Characterize resulting microstructure d. Measure target properties e. Update surrogate model with new data

- Continue until convergence or resource exhaustion

Validation and Interpretation

- Validate optimal materials through independent replication

- Interpret active subspaces to identify microstructural features most critical to performance

- Document process-structure-property relationships revealed by the optimization

Troubleshooting:

- If optimization stagnates, consider expanding the latent dimensionality

- For noisy property measurements, increase the regularization in the GP model

- If experimental variance is high, implement batch sampling to account for uncertainty

Protocol 2: Latent-Space Treatment Personalization for Clinical Applications

Objective: Identify optimal treatment assignments for individual patients based on latent patient prototypes.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Patient baseline characteristics (demographic, clinical, biomarker)

- Treatment response data

- Computational infrastructure for deep learning model training

- Validation cohort data

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing and Integration

- Clean and normalize patient baseline characteristics

- Handle missing data using appropriate imputation methods

- Encode categorical variables and ensure data quality

DPNN Model Architecture and Training

- Implement neural network with parallel structure for prototype identification and outcome prediction

- Configure multifaceted loss function balancing prediction accuracy and prototype cohesiveness

- Train model using historical patient-treatment-outcome data

- Validate prototype quality and predictive performance on holdout set

Treatment Assignment Optimization

- For new patient, encode baseline characteristics into latent space

- Identify relevant prototypes and their membership weights

- Compute personalized outcome predictions for each available treatment

- Select treatment with highest predicted probability of success

Validation and Model Updating

- Implement prospective validation in clinical setting

- Continuously monitor treatment outcomes and model performance

- Update model with new data following appropriate validation protocols

Ethical Considerations:

- Ensure diverse representation in training data to avoid biased recommendations

- Maintain physician oversight of all treatment decisions

- Implement transparent documentation of model limitations and uncertainties

Computational Tools and Implementation

Workflow Visualization: Microstructure-Aware Materials Design

Diagram 1: Microstructure-aware Bayesian optimization workflow for materials design

Workflow Visualization: Latent-Space Treatment Personalization

Diagram 2: Latent-space treatment personalization using differential prototyping

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Latent Space Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | Diffusion Models, Flow Matching, VAEs | Learn latent representations from high-dimensional data | Molecular design, microstructure generation [10] |

| Optimization Frameworks | Bayesian Optimization, CMA-ES | Efficient navigation in latent space | Materials design, treatment optimization [3] [9] |

| Dimensionality Reduction | Active Subspaces, PCA, Autoencoders | Construct lower-dimensional latent spaces | Microstructure descriptor compression [3] |

| Surrogate Modeling | Gaussian Processes, Bayesian Neural Networks | Probabilistic modeling in latent space | Predicting material properties, treatment outcomes [11] |

| Inversion Tools | DDIM, Probability Flow ODE | Map data to latent representations | Protein design, molecular optimization [10] |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite promising results, latent space approaches face several significant challenges. The distribution mismatch between original and reconstructed spaces can lead to suboptimal performance, particularly in high-dimensional Bayesian optimization [11]. Methods like HiPPO-based space consistency aim to address this by preserving kernel relationships during latent space construction, but general solutions remain elusive. Interpretability presents another challenge—while latent spaces enable efficient optimization, understanding what specific features they capture requires additional analysis techniques like active subspaces.

Future work will likely focus on improving the robustness of latent space representations, developing better methods for handling multi-modal data, and creating more interpretable latent representations. The integration of physical constraints and domain knowledge into latent space learning represents another promising direction, particularly for scientific applications where fundamental principles are known. As generative AI models continue to advance, their integration with latent space optimization will likely open new frontiers in materials design, drug development, and scientific discovery.

Bayesian optimization (BO) is a powerful strategy for the global optimization of expensive, black-box functions, making it particularly suited for advanced materials research and drug development where physical experiments or complex simulations are costly and time-consuming [12] [13]. The core challenge it addresses is finding the global optimum of a function whose analytical form is unknown and whose derivatives are unavailable, with as few evaluations as possible [13] [14]. This is achieved through a synergistic interplay of three key components: a surrogate model that statistically approximates the black-box function, an acquisition function that guides the selection of future experiments by balancing exploration and exploitation, and an active learning loop that iteratively updates the model with new data [12] [13]. Within materials science, this framework has been successfully applied to tasks such as discovering shape memory alloys with specific transformation temperatures [7] and identifying novel phase-change memory materials with superior properties [15].

Surrogate Models: Gaussian Processes and Beyond

The surrogate model forms the probabilistic foundation of BO, providing a computationally cheap approximation of the expensive objective function and quantifying the uncertainty of its own predictions [12] [13].

Gaussian Process Models

Gaussian Processes (GPs) are the most widely used surrogate models in Bayesian optimization. A GP defines a prior over functions and can be updated with data to form a posterior distribution. For a set of data points (\mathcal{D}{1:t} = {(\mathbf{x}1, y),...,(\mathbf{x}t, y_t)}), the GP posterior predictive distribution at a new point (\mathbf{x}) is characterized by a mean (\mu(\mathbf{x})) and variance (\sigma^2(\mathbf{x})) [13]. The mean function provides an estimate of the objective, while the variance represents the model's uncertainty. This explicit uncertainty quantification is crucial for the function of acquisition functions. GPs are distinguished by their mathematical explicitness, flexibility, and straightforward uncertainty quantification [12].

Advanced and Adaptive Surrogate Models

While GPs are powerful, their performance can be challenged by high-dimensional design spaces or non-smooth objective functions. Consequently, more adaptive and flexible Bayesian models have been explored as surrogates to enhance the BO framework's robustness and efficiency [12].

- Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART): BART is an ensemble-learning-based method that fits unknown functional patterns through a sum of small trees. It is equipped with automatic feature selection techniques, making it particularly useful when the objective function is very complex [12].

- Bayesian Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (BMARS): BMARS is a flexible nonparametric approach based on product spline basis functions. It can effectively model non-smooth functions with sudden transitions, a common occurrence in many materials science challenges where phase changes occur [12].

- Correlated Latent Space Models (CoBO): For structured or discrete data, such as molecular structures, optimization can be performed in a latent space learned by deep generative models like variational autoencoders. The CoBO framework introduces techniques to strengthen the correlation between distances in the latent space and distances in the objective function, minimizing the inherent gap that can lead to suboptimal solutions [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Surrogate Models for Bayesian Optimization.

| Model Type | Key Features | Best-Suited Problems | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Explicit uncertainty, smooth interpolation [12]. | Low-to-moderate dimensional, smooth objective functions. | Benchmark method; performance can degrade with high dimensions or non-smoothness [12]. |

| BART | Ensemble of trees, automatic feature selection [12]. | Complex, high-dimensional functions with interactions. | Enhanced search efficiency and robustness compared to GP on complex test functions (e.g., Rastrigin) [12]. |

| BMARS | Spline-based, nonparametric, handles non-smoothness [12]. | Functions with sudden transitions or non-smooth patterns. | Superior to GP-based methods on non-smooth objectives; efficient in high dimensions [12]. |

| Correlated Latent BO | Operates in generative model's latent space [4]. | Structured/discrete data (e.g., molecules, chemical formulas). | Effectively optimizes discrete structures by learning a correlated latent representation [4]. |

Acquisition Functions: Guiding the Experiment

The acquisition function (u(\mathbf{x})) is the decision-making engine of BO. It uses the surrogate model's posterior to compute the utility of evaluating a candidate point (\mathbf{x}), balancing the need to explore regions of high uncertainty (to reduce model error) and exploit regions with promising predicted values (to refine the optimum) [13]. The next point to evaluate is chosen by maximizing the acquisition function: (\mathbf{x}{t+1} = \operatorname{argmax}{\mathbf{x}} u(\mathbf{x})) [13].

Common Acquisition Functions

Several acquisition functions have been developed, each with a slightly different mechanism for balancing exploration and exploitation.

Expected Improvement (EI): EI measures the expected amount by which the observation at (\mathbf{x}) will improve upon the current best observation (f(\mathbf{x}^+)). It is one of the most widely used acquisition functions and can be evaluated analytically under the GP surrogate [13] [16]: [ \operatorname{EI}(\mathbf{x}) = \begin{cases} (\mu(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+) - \xi)\Phi(Z) + \sigma(\mathbf{x})\phi(Z) &\text{if}\ \sigma(\mathbf{x}) > 0 \ 0 & \text{if}\ \sigma(\mathbf{x}) = 0 \end{cases} ] where (Z = \frac{\mu(\mathbf{x}) - f(\mathbf{x}^+) - \xi}{\sigma(\mathbf{x})}), and (\Phi) and (\phi) are the CDF and PDF of the standard normal distribution, respectively. The parameter (\xi) controls the exploration-exploitation trade-off, with higher values leading to more exploration [13].

Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Also known as the lower confidence bound for minimization, UCB is a straightforward function that combines the mean and uncertainty of the prediction [16]: [ \operatorname{UCB}(\mathbf{x}) = \mu(\mathbf{x}) + \beta \sigma(\mathbf{x}) ] Here, (\beta) is a parameter that controls the weight given to exploration.

Probability of Improvement (PI): PI measures the probability that a new sample will improve upon the current best value [16]: [ \operatorname{PI}(x) = \Phi\left( \frac{\mu(x) - f(x^+) - \xi}{\sigma(x)} \right) ]

Specialized Acquisition Functions for Materials Science

The standard acquisition functions are designed for finding global maxima or minima. However, many materials applications require finding a material with a specific target property value, not merely an optimum.

Target-Oriented Expected Improvement (t-EI): Developed for target-specific property values, t-EI aims to sample candidates whose property value is closer to a predefined target (t) than the current best candidate [7]. It is defined as: [ t-EI = E\left[\max (0, |y{t.min} - t| - |Y - t| )\right] ] where (y{t.min}) is the value in the training set closest to the target, and (Y) is the predicted random variable. This method has been shown to require significantly fewer experimental iterations to reach a target value compared to reformulating the problem as a minimization of (|y-t|) using standard EI [7].

Multi-Objective and Constrained Acquisition Functions: In real-world materials design, it is often necessary to optimize multiple properties simultaneously or subject to constraints. Multi-objective acquisition functions (MOAF) seek a Pareto-front solution, while constrained EGO (CEGO) uses a constrained expected improvement (CEI) to incorporate feasibility [7].

Table 2: Key Acquisition Functions and Their Applications in Research.

| Acquisition Function | Mathematical Formulation | Primary Use-Case | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | (\operatorname{EI}(\mathbf{x}) = (\mu - f^+ - \xi)\Phi(Z) + \sigma\phi(Z)) [13] [16] | General-purpose global optimization (default choice). | ||||

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | (\operatorname{UCB}(\mathbf{x}) = \mu(\mathbf{x}) + \beta \sigma(\mathbf{x})) [16] | Optimization with an explicit exploration parameter. | ||||

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | (\operatorname{PI}(x) = \Phi\left( \frac{\mu(x) - f(x^+) - \xi}{\sigma(x)} \right)) [16] | Finding the region of the optimum quickly; less used than EI. | ||||

| Target-oriented EI (t-EI) | (E\left[\max (0, | y_{t.min} - t | - | Y - t | )\right]) [7] | Finding a material with a specific target property value. |

| Multi-Objective AF (MOAF) | Seeks Pareto-front solution for multiple acquisition values [7]. | Simultaneously optimizing multiple material properties. |

The Active Learning Loop in Practice

The active learning loop is the iterative procedure that integrates the surrogate model and acquisition function into a closed-loop experimental design system [15]. A typical implementation of this loop for materials research is as follows [13]:

- Initialization: A small initial dataset is collected, often using a space-filling design like a Latin Hypercube Sample (LHS) to get a rough initial model of the design space [14].

- Model Fitting: A surrogate model (e.g., a GP) is trained on all data collected so far.

- Acquisition Optimization: The acquisition function (e.g., EI) is computed based on the surrogate's predictions and is then maximized to propose the next experiment (\mathbf{x}_{t+1}).

- Experiment Execution: The proposed experiment is performed (e.g., a new material composition is synthesized and characterized), and the objective function value (y_{t+1}) is obtained.

- Data Update: The new data pair ((\mathbf{x}{t+1}, y{t+1})) is added to the training dataset.

- Iteration: Steps 2-5 are repeated until a stopping criterion is met, such as the exhaustion of an experimental budget, convergence, or the discovery of a material satisfying the target criteria.

This closed-loop system has been embodied in platforms like the Autonomous System for Materials Exploration and Optimization (CAMEO), which operates at synchrotron beamlines to autonomously discover new materials, demonstrating a ten-fold reduction in the number of experiments required [15].

Diagram 1: The Bayesian Optimization Active Learning Loop.

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Discovering a Shape Memory Alloy with a Target Transformation Temperature

Objective: To discover a Ni-Ti-based shape memory alloy (SMA) with a phase transformation temperature as close as possible to a target of 440°C for use as a thermostatic valve material [7].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Elemental Precursors: High-purity Nickel (Ni), Titanium (Ti), Copper (Cu), Hafnium (Hf), and Zirconium (Zr) for alloy synthesis.

- Synthesis Platform: An arc melter or a high-throughput synthesis robot for rapid sample preparation.

- Characterization Tool: A differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) for accurate measurement of the phase transformation temperature.

Methodology:

- Initial Design: Prepare a small set (e.g., 5-10) of initial Ni-Ti-X alloy samples with compositions selected via a space-filling design over the feasible composition space.

- Characterization: Measure the transformation temperature for each initial sample using DSC.

- Model Configuration: Implement a BO loop using a GP surrogate model and the target-oriented Expected Improvement (t-EI) acquisition function, with the target value (t) set to 440°C.

- Active Learning Loop: For each iteration: a. Model Training: Train the GP model on all available (composition, temperature) data. b. Suggestion: Propose the next alloy composition to synthesize by maximizing the t-EI function. c. Synthesis & Measurement: Synthesify the proposed alloy and measure its transformation temperature. d. Update: Add the new data point to the training set.

- Termination: Stop the loop after a fixed budget of experiments (e.g., 10-15 iterations) or when a material with a transformation temperature within an acceptable tolerance (e.g., ±5°C) is found.

Outcome: This protocol led to the discovery of SMA (\text{Ti}{0.20}\text{Ni}{0.36}\text{Cu}{0.12}\text{Hf}{0.24}\text{Zr}_{0.08}) with a transformation temperature of 437.34°C, only 2.66°C from the target, within just 3 experimental iterations [7].

Protocol 2: Autonomous Discovery of a Novel Phase-Change Material

Objective: To find a Ge-Sb-Te (GST) ternary composition with the largest possible change in optical bandgap ((\Delta E_g)) between its amorphous and crystalline states for superior photonic switching devices [15].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Materials Library: A composition spread wafer library covering the Ge-Sb-Te ternary system, fabricated via combinatorial sputtering.

- Characterization Setup: A synchrotron beamline for high-throughput X-ray diffraction (XRD) to determine the crystal structure and phase map, and an ellipsometer for measuring optical properties.

- Automation Framework: The CAMEO algorithm installed on the beamline's control computer for real-time, closed-loop operation.

Methodology:

- Prior Integration: Incorporate any prior knowledge (e.g., from ellipsometry spectra) into the initial phase mapping model.

- Dual-Objective Acquisition: Implement the CAMEO algorithm, which uses a specialized acquisition function, (g), that balances two objectives: maximizing knowledge of the phase map (P(\mathbf{x})) and optimizing the functional property (F(\mathbf{x})) (here, (\Delta Eg)). The next point is selected as (\mathbf{x}* = \mathrm{argmax}_{\mathbf{x}} \, g(F(\mathbf{x}), P(\mathbf{x}))) [15].

- Closed-Loop Execution: The algorithm autonomously: a. Analyzes the latest XRD data to update the phase map. b. Selects the most informative composition to measure next based on the dual objective. c. Directs the beamline to perform the measurement.

- Human-in-the-Loop: Optionally, a human expert can monitor the process and provide guidance, which the algorithm can incorporate.

- Validation: Promising compositions identified by the autonomous loop are then validated by fabricating and testing actual device prototypes.

Outcome: This protocol resulted in the discovery of a novel, stable epitaxial nanocomposite phase-change material at a phase boundary, which exhibited an optical contrast up to three times larger than the well-known Ge(2)Sb(2)Te(_5) (GST225) compound [15].

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of Bayesian Optimization Methods.

| Optimization Method / Strategy | Test Problem / Application | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target-Oriented BO (t-EGO) [7] | Synthetic functions & 2D materials database (HER catalysts). | Average iterations to reach target (vs. EGO/MOAF). | Required 1 to 2 times fewer experimental iterations [7]. |

| BO with BART/BMARS [12] | Rosenbrock & Rastrigin function optimization. | Minimum observed value vs. number of function evaluations. | Showed faster decline and better performance than GP-based methods, especially with small initial datasets [12]. |

| CAMEO [15] | Discovery of phase-change memory material (Ge-Sb-Te system). | Number of experiments required for discovery. | Achieved a ten-fold reduction in the number of experiments required compared to traditional methods [15]. |

The exploration of chemical space for molecular and materials discovery is fundamentally a challenge of navigating discrete, combinatorial structures. However, key computational methodologies, particularly Bayesian optimization (BO), operate most effectively within continuous domains. This application note examines the critical need for and advantages of creating continuous representations of discrete chemical structures to accelerate discovery campaigns. We detail how latent space Bayesian optimization frameworks address this representational challenge, enabling efficient navigation of vast molecular search spaces. Within the context of an overarching thesis on Bayesian optimization in latent space for materials research, we provide specific protocols for implementing these approaches, including quantitative performance comparisons and detailed workflows for representing discrete molecular graphs as continuous vectors suitable for probabilistic modeling and optimization.

The set of possible molecules and materials is fundamentally discrete and combinatorially vast. Individual molecular structures are distinct, separate entities, much like the distinct values that define discrete data [17]. However, the properties and functions of these materials often depend on continuous physical phenomena. This creates a fundamental tension: how can we efficiently search a discrete, high-dimensional chemical space using optimization frameworks that typically require continuous input representations?

Bayesian optimization (BO) has emerged as a powerful, sample-efficient framework for guiding materials discovery within an active learning loop, particularly when experiments or simulations are expensive [7] [18]. BO relies on a probabilistic surrogate model, such as a Gaussian Process, to model an unknown objective function and an acquisition function to decide which experiments to perform next. However, the performance of BO is heavily influenced by the representation of the input material [18]. A fixed, high-dimensional discrete representation can lead to poor performance due to the curse of dimensionality, while an overly simplified representation may lack the chemical detail necessary to predict performance accurately.

Consequently, there is a pressing need for continuous representations of these discrete structures. A continuous representation embeds discrete objects (like molecules) into a continuous space where similarities and distances are meaningfully preserved. This allows for the application of powerful continuous optimization techniques, such as BO, to problems of a discrete nature. The following sections detail the methodologies, applications, and protocols for successfully implementing this paradigm.

Theoretical Foundations: Bridging the Discrete-Continuous Divide

Discrete vs. Continuous Mathematical Frameworks

- Discrete Structures: Molecules and crystalline materials are naturally represented as discrete graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) or combinatorial sets of building blocks. These structures are countable and possess distinct, separable states [19] [17].

- Continuous Representations: These are function representations that map positional coordinates or latent variables to a response value. They offer inherent advantages for optimization, including resolution flexibility, inherent smoothness, and parameter efficiency [20]. In machine learning, this often involves creating a smooth, continuous latent space where similar molecules are clustered together.

Latent Space Bayesian Optimization

The core solution involves compressing discrete chemical structures into a smooth, continuous latent space where Bayesian optimization can be performed efficiently.

- Multi-level Bayesian Optimization: One advanced approach uses transferable coarse-grained models to compress chemical space into varying levels of resolution. Discrete molecular spaces are first transformed into smooth latent representations. Bayesian optimization is then performed within these latent spaces, using simulations to calculate target properties. This multi-level approach effectively balances exploration (at lower resolutions) and exploitation (at higher resolutions) [21].

- Joint Composite Latent Space BO (JoCo): For complex, high-dimensional outputs, the JoCo framework jointly trains neural network encoders and probabilistic models to adaptively compress both high-dimensional inputs and outputs into manageable latent representations. This enables effective BO on these compressed representations [22].

- Feature Adaptive Bayesian Optimization (FABO): Instead of relying on a fixed representation, FABO dynamically identifies the most informative features influencing material performance at each BO cycle. This enables autonomous exploration of the search space with minimal prior information about the best representation [18].

Application Notes and Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the performance of various latent space BO methods across different molecular and materials optimization tasks, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Continuous Representation Methods in Bayesian Optimization

| Method | Core Approach | Application Domain | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-level BO with Hierarchical Coarse-Graining [21] | Transforms discrete molecules into multi-resolution latent spaces for BO. | Enhancing phase separation in phospholipid bilayers. | Effective navigation of chemical space for free energy-based optimization. | Balances combinatorial complexity & chemical detail. |

| Target-Oriented BO (t-EGO) [7] | Uses acquisition function t-EI to sample candidates based on distance to a target property value. | Discovering shape memory alloys with a target transformation temperature. | Achieved a temperature difference of only 2.66°C from target in 3 experimental iterations. | Superior for finding materials with specific target properties, not just optima. |

| Feature Adaptive BO (FABO) [18] | Dynamically adapts material representations throughout BO cycles. | MOF discovery for CO2 adsorption and band gap optimization. | Outperforms BO with fixed representations, especially in novel tasks. | Automatically identifies relevant features without prior knowledge. |

| Joint Composite Latent BO (JoCo) [22] | Jointly compresses high-dimensional input and output spaces into latent representations. | High-dimensional BO in generative AI, molecular design, and robotics. | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods on a variety of simulated and real-world problems. | Effectively handles high-dimensional input and output spaces. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Level Bayesian Optimization with Coarse-Graining

This protocol is adapted from methods used to optimize molecules for enhancing phase separation in phospholipid bilayers [21].

1. Problem Definition:

- Objective: Identify molecules that maximize or minimize a target property (e.g., free energy of binding, phase separation propensity).

- Search Space: Define the discrete set of molecular structures or modifications to be considered.

2. Multi-Resolution Representation:

- Step 1: Hierarchical Coarse-Graining. Develop or apply transferable coarse-grained models that represent molecules at multiple levels of resolution (e.g., atomistic, united-atom, ultra-coarse-grained).

- Step 2: Latent Space Transformation. For each resolution level, use an encoder (e.g., a variational autoencoder or other neural network) to transform the discrete molecular representation into a continuous latent vector. The latent space should be smooth, meaning small changes in the latent vector correspond to small changes in the molecular structure and its properties.

3. Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Step 3: Initialization. Populate a dataset with an initial set of molecules and their measured properties. This can be a small, random set or based on prior knowledge.

- Step 4: Lower-Resolution Exploration. Use a lower-fidelity, coarse-grained model to perform Bayesian optimization in the corresponding latent space. This step is computationally cheaper and aims to identify promising neighborhoods in the chemical space.

- Step 5: Higher-Resolution Exploitation. Use the promising regions identified at the coarse level to guide a more focused BO campaign in a higher-resolution latent space. The surrogate model at this level uses more accurate (and expensive) simulations or experiments.

- Step 6: Iteration and Selection. Iterate between exploration and exploitation across resolution levels until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., no significant improvement after a set number of iterations). The best-performing molecule from the high-fidelity evaluations is selected.

Diagram 1: Multi-level BO workflow

Protocol 2: Target-Oriented Bayesian Optimization for Specific Properties

This protocol is designed for discovering materials with a specific target property value, rather than simply a maximum or minimum, as demonstrated in the discovery of shape memory alloys [7].

1. Problem Definition:

- Objective: Find a material

xsuch that its propertyy(x)is as close as possible to a predefined target valuet(e.g., a transformation temperature of 440°C). - Search Space: Define the compositional or structural space of materials (e.g., the proportions of Ti, Ni, Cu, Hf, Zr in an alloy).

2. Gaussian Process Modeling:

- Step 1: Model Training. Train a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model using the available data. The input is the material representation (e.g., composition), and the output is the measured property

y. - Model Specification: A GP is defined as

f(x) ~ GP(0, k(x, x')), wherekis a kernel function. The predictive meanμ(x)and varianceσ²(x)for a new candidatexare given by:μ(x) = k_x(K + σ²_εI)⁻¹yσ²(x) = k(x,x) - k_x(K + σ²_εI)⁻¹k_xᵀ

3. Target-Oriented Acquisition:

- Step 2: Calculate Target-specific Expected Improvement (t-EI). Instead of the standard Expected Improvement (EI), use the t-EI acquisition function.

- Definition: Let

y_t.minbe the current property value closest to the targett. The improvement is defined asI = max( |y_t.min - t| - |Y - t|, 0 ), whereYis the random variable of the GP prediction atx. The expected improvement is then:t-EI(x) = E[I] - Step 3: Candidate Selection. Select the next material to test by maximizing the t-EI function:

x_next = argmax t-EI(x).

4. Iteration:

- Step 4: Experiment and Update. Synthesize and test the candidate

x_next, measure its propertyy_next, and add the new data point(x_next, y_next)to the training dataset. Update the GP model and repeat from Step 2 until a material satisfying the target criterion is found.

Protocol 3: Feature Adaptive Bayesian Optimization (FABO)

This protocol is used when the optimal representation of a material is not known in advance, as in the discovery of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [18].

1. Initialization:

- Step 1: Define a Complete Feature Pool. Start with a high-dimensional, comprehensive set of features that describe the materials. For MOFs, this could include chemical descriptors (e.g., Revised Autocorrelation Calculations - RACs) and pore geometric characteristics.

2. Bayesian Optimization Cycle:

- Step 2: Data Labeling. Perform an experiment or simulation to measure the property of interest for an initial set of materials.

- Step 3: Feature Selection. Using only the data acquired during the BO campaign so far, apply a feature selection method to identify the most relevant features.

- Method A: Maximum Relevancy Minimum Redundancy (mRMR). Selects features that maximize relevance to the target

y(e.g., using F-statistic) while minimizing redundancy with already-selected features. - Method B: Spearman Ranking. A univariate method that ranks features based on the absolute value of their Spearman rank correlation coefficient with the target variable.

- Method A: Maximum Relevancy Minimum Redundancy (mRMR). Selects features that maximize relevance to the target

- Step 4: Surrogate Model Update. Train the GP surrogate model using the currently selected, reduced feature set.

- Step 5: Candidate Selection. Use a standard acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement or Upper Confidence Bound) to select the next material to test based on the updated model.

- Step 6: Iterate. Repeat steps 2-5 until the optimization budget is exhausted or performance converges.

Diagram 2: Feature adaptive BO cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key computational "reagents" and their functions in constructing continuous representations for Bayesian optimization.

Table 2: Essential Components for Continuous Representation workflows

| Tool / Method | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) [7] [18] | Probabilistic Model | Serves as a surrogate model to predict material properties and quantify uncertainty. | Core to all BO protocols for regression and uncertainty estimation. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Neural Network | Encodes discrete structures (e.g., molecular graphs) into a continuous latent vector; can decode vectors back to structures. | Creating the latent space for multi-level BO [21] and JoCo [22]. |

| Coarse-Grained Molecular Model [21] | Simplified Physical Model | Provides a low-fidelity, computationally cheap representation of a molecule for initial screening. | The lower-resolution level in multi-level BO. |

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., RACs) [18] | Feature Vector | Numerically encodes chemical and topological aspects of a molecule into a fixed-length vector. | Forms the initial feature pool in FABO for representing MOFs and molecules. |

| Maximum Relevancy Minimum Redundancy (mRMR) [18] | Feature Selection Algorithm | Dynamically selects an informative and non-redundant subset of features from a large pool. | Adapting the representation in the FABO protocol. |

| Target-specific Expected Improvement (t-EI) [7] | Acquisition Function | Guides the search towards candidates whose predicted property is close to a specific target value. | Core component of the target-oriented BO protocol. |

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Chemistry and Biomedicine

The exploration of chemical space, estimated to contain over 10^60 drug-like molecules, represents one of the most significant challenges in modern materials research and drug discovery [23]. This vastness necessitates sophisticated computational approaches that can efficiently navigate molecular structures and properties. Graph neural networks (GNNs) and autoencoders have emerged as transformative technologies for molecular representation, directly addressing the inherent graph-based structure of molecules where atoms constitute nodes and bonds form edges. When integrated with Bayesian optimization (BO) frameworks, these encoding techniques enable accelerated materials discovery by constructing informative latent spaces that dramatically reduce the dimensionality and complexity of molecular design challenges.

Key Architectures for Molecular Representation

Graph Autoencoders for Molecular Generation

Autoencoders have proven effective as deep learning models that can function as both generative models and representation learning tools for downstream tasks. Specifically, graph autoencoders with encoder and decoder implemented as message-passing networks generate permutation-invariant graph representations—a critical property for handling molecular structures [24]. However, this approach faces significant challenges in decoding graph structures from single vectors and requires effective permutation-invariant similarity measures for comparing input and output graphs.

Recent innovations address these limitations through transformer-based message passing graph decoders. These architectures leverage global attention mechanisms to create more robust and expressive decoders compared to traditional graph neural network decoders [24]. The precision of graph matching during training has been shown to significantly impact model behavior and is essential for effective de novo molecular graph generation [24].

The Transformer Graph Variational Autoencoder (TGVAE) represents another architectural advancement that employs molecular graphs as direct input, capturing complex structural relationships more effectively than string-based models like Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) [25]. This approach combines transformers, GNNs, and variational autoencoders (VAEs) to generate chemically valid and diverse molecular structures while addressing common training issues like over-smoothing in GNNs and posterior collapse in VAEs [26] [25].

Kolmogorov-Arnold Graph Neural Networks (KA-GNNs)

A novel framework called Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs) integrates Kolmogorov-Arnold networks (KANs) into the three fundamental components of GNNs: node embedding, message passing, and readout [27]. This integration replaces conventional multi-layer perceptrons with learnable univariate functions on edges, enabling more accurate and interpretable modeling of complex molecular functions.

The KA-GNN architecture employs Fourier-series-based univariate functions within KANs to enhance function approximation capabilities. This approach effectively captures both low-frequency and high-frequency structural patterns in graphs, enhancing the expressiveness of feature embedding and message aggregation [27]. Theoretical analysis demonstrates that this Fourier-based KAN architecture possesses strong approximation capability for any square-integrable multivariate function, providing solid mathematical foundations for molecular property prediction [27].

Two architectural variants have been developed: KA-Graph Convolutional Networks (KA-GCN) and KA-Graph Attention Networks (KA-GAT). Experimental results across seven molecular benchmarks show that KA-GNNs consistently outperform conventional GNNs in prediction accuracy and computational efficiency while offering improved interpretability by highlighting chemically meaningful substructures [27].

Table 1: Key Architectural Innovations in Molecular Graph Representation

| Architecture | Core Innovation | Advantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer-based Graph Decoder [24] | Global attention mechanisms in decoding | Robustness, expressivity, improved graph matching | De novo molecular graph generation |

| TGVAE [26] [25] | Combines transformer, GNN, and VAE | Chemical validity, diversity, handles graph inputs | Drug discovery, molecular design |

| KA-GNN [27] | Integrates KAN modules into GNN components | Accuracy, parameter efficiency, interpretability | Molecular property prediction |

| DeeperGAT-VAE [26] | Lightweight, deep graph-attention blocks | Prevents over-smoothing, works on small datasets | Small-data molecular generation |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Active Learning for Electrolyte Discovery

This protocol demonstrates how machine learning can explore massive chemical spaces with minimal initial data, achieving efficient molecular discovery through iterative experimentation [28].

Workflow Overview:

- Initialization: Begin with a small set of 58 experimentally validated data points covering diverse molecular structures.

- Model Training: Train an active learning model on available data points to predict electrolyte performance.

- Candidate Selection: Use the model to select promising electrolyte candidates from a virtual search space of 1 million potential molecules.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize predicted high-performing electrolytes and test in actual battery systems, measuring cycle life and discharge capacity.

- Data Integration: Feed experimental results back into the model for refinement.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 through seven active learning campaigns, testing approximately 10 electrolytes per campaign.

- Final Selection: Identify top-performing electrolytes that rival state-of-the-art performance.

Key Considerations:

- Address model uncertainty through experimental verification at each cycle

- Focus on real-world performance metrics rather than computational proxies

- Overcome human bias toward previously studied chemical spaces

Protocol 2: KA-GNN Implementation for Property Prediction

This protocol details the implementation of Kolmogorov-Arnold Graph Neural Networks for molecular property prediction, combining the strengths of GNNs and KANs [27].

Workflow Overview:

- Data Preparation:

- Curate molecular datasets with annotated properties

- Represent molecules as graphs with node features (atomic number, radius) and edge features (bond type, length)

Model Configuration:

- Select KA-GCN or KA-GAT variant based on task requirements

- Initialize Fourier-based KAN layers with specified harmonic components

- Configure node embedding, message passing, and readout components with KAN modules

Training Procedure:

- Implement residual connections in KAN layers for stable training

- Use task-specific loss functions (e.g., mean squared error for regression, cross-entropy for classification)

- Employ adaptive optimization algorithms with gradient clipping

Interpretation and Analysis:

- Visualize learned KAN functions to identify important molecular features

- Analyze attention weights in KA-GAT for substructure importance

- Validate chemically meaningful patterns in latent representations

Implementation Details:

- Replace fixed activation functions with learnable Fourier series

- Initialize node embeddings by concatenating atomic features with neighborhood bond features

- Use residual KAN connections in message passing steps

- Implement graph-level readout through adaptive pooling and KAN transformations

Bayesian Optimization in Latent Chemical Space

Joint Composite Latent Space Bayesian Optimization (JoCo)

The JoCo framework addresses the challenge of optimizing high-dimensional composite functions common in molecular design, where ( f = g \circ h ), with ( h ) mapping to high-dimensional intermediate outputs [29]. Traditional Bayesian optimization struggles with high-dimensional spaces, but JoCo jointly trains neural network encoders and probabilistic models to adaptively compress both input and output spaces into manageable latent representations.

This approach enables effective BO on compressed representations, significantly outperforming state-of-the-art methods for high-dimensional problems with composite structure [29]. Applications include optimizing generative AI models with text prompts as inputs and complex outputs like images, molecular design problems, and aerodynamic design with high-dimensional output spaces of pressure and velocity fields.

Microstructure-Aware Bayesian Materials Design

A novel microstructure-sensitive BO framework enhances materials discovery efficiency by explicitly incorporating microstructural information as latent variables [3]. This approach moves beyond traditional chemistry-process-property relationships to establish comprehensive process-structure-property mappings.

The methodology employs active subspace methods for dimensionality reduction to identify influential microstructural features, reducing computational complexity while maintaining accuracy [3]. Case studies on Mg(2)Sn(x)Si(_{1-x}) thermoelectric materials demonstrate the framework's ability to accelerate convergence to optimal material configurations with fewer iterations.

Table 2: Bayesian Optimization Frameworks for Latent Space Exploration

| Framework | Core Approach | Dimensionality Handling | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| JoCo [29] | Joint encoding of inputs/outputs | Adaptive compression | High-dimensional composite functions |

| Microstructure-Aware BO [3] | Active subspace methods | Dimensionality reduction | Materials design with structural descriptors |

| Conformal Prediction [23] | Mondrian conformal predictors | Uncertainty-calibrated selection | Virtual screening of billion-molecule libraries |

Performance Benchmarks and Quantitative Analysis

Molecular Generation Performance

Recent advancements in graph-based autoencoders demonstrate significant improvements in generation metrics. The TGVAE and DeeperGAT-VAE models achieve high validity, uniqueness, diversity, and novelty while reproducing key drug-like property distributions [26]. The incorporation of SMILES pair-encoding rather than character-level tokens captures larger chemically relevant substructures, supporting generation of more diverse and novel molecules [26].

Evaluation against PubChem confirms that SMILES pair-encoding greatly expands the space of scaffolds and fragments unseen in public databases, significantly broadening accessible chemical space [26].

Virtual Screening Acceleration

Machine learning-guided docking screens enable rapid virtual screening of billion-compound libraries. The combination of conformal prediction with molecular docking achieves more than 1,000-fold reduction in computational cost compared to traditional structure-based virtual screening [23].

In application to G protein-coupled receptors (important drug targets), this approach successfully identified ligands with multi-target activity tailored for therapeutic effect [23]. The CatBoost classifier with Morgan2 fingerprints provided optimal balance between speed and accuracy, screening 3.5 billion compounds with high efficiency.

Table 3: Performance Benchmarks of Molecular Machine Learning Approaches

| Method | Dataset/Task | Key Metrics | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| KA-GNN [27] | 7 molecular benchmarks | Prediction accuracy | Consistent outperformance vs. conventional GNNs |

| Active Learning [28] | Electrolyte discovery (1M library) | Experimental validation | 4 new electrolytes rivaling state-of-the-art |

| ML-Guided Docking [23] | 3.5B compound library | Computational efficiency | 1000-fold cost reduction |

| Conformal Prediction [23] | 8 protein targets | Sensitivity/Precision | 0.87-0.88 sensitivity at ~10% library screening |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Molecular Representation Learning

| Tool/Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks | Learn molecular representations directly from graph structure | Message passing networks [24] |

| Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks | Learnable activation functions for improved expressivity | Fourier-based KAN layers [27] |

| Variational Autoencoders | Generative modeling and latent space learning | TGVAE, DeeperGAT-VAE [26] [25] |

| Active Learning Frameworks | Efficient exploration of chemical space with minimal data | Iterative experiment-model loops [28] |

| Conformal Prediction | Uncertainty-calibrated molecular screening | Mondrian conformal predictors [23] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Sample-efficient black-box optimization | JoCo framework [29] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Feature representation for machine learning | Morgan fingerprints, CDDD, RoBERTa embeddings [23] |

| Docking Software | Structure-based virtual screening | Molecular docking calculations [23] |

The integration of graph neural networks and autoencoders for molecular representation has created powerful frameworks for encoding chemical space into meaningful latent representations. Architectures such as KA-GNNs, transformer-based graph autoencoders, and deep graph variational autoencoders demonstrate significant advantages over traditional methods in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability. When combined with Bayesian optimization in latent spaces, these approaches enable accelerated discovery of novel materials and drug candidates by efficiently navigating vast chemical landscapes. The continued development of these methodologies, particularly with emphasis on uncertainty quantification, interpretability, and integration with experimental validation, promises to further transform materials research and drug discovery pipelines.

Molecular discovery within the vast chemical space remains a significant challenge due to the immense number of possible molecules and limited scalability of conventional screening methods [21] [30] [31]. The combinatorial complexity of atomic arrangements creates a search space too large for exhaustive exploration through traditional experimental or computational approaches. To address this challenge, researchers have developed multi-level Bayesian optimization (BO) with hierarchical coarse-graining, an active learning-based method that uses transferable coarse-grained models to compress chemical space into varying levels of resolution [31]. This approach effectively balances the competing demands of combinatorial complexity and chemical detail by employing a funnel-like strategy that progresses from low-resolution exploration to high-resolution exploitation.

Framed within the broader context of Bayesian optimization in latent space for materials research, this methodology represents a significant advancement for computational molecular discovery. By transforming discrete molecular spaces into smooth latent representations and performing Bayesian optimization within these spaces, the technique enables efficient navigation of chemical spaces for free energy-based molecular optimization [21]. The multi-level approach has demonstrated particular effectiveness in optimizing molecules to enhance phase separation in phospholipid bilayers, showcasing its potential for drug development and materials science applications [30] [31].

Theoretical Framework

Hierarchical Coarse-Graining of Chemical Space

Coarse-graining addresses the complexity of chemical space by grouping atoms into pseudo-particles or beads, effectively compressing the vast combinatorial possibilities into manageable representations [31]. This process consists of two fundamental steps: mapping groups of atoms to beads, and defining interactions between these beads based on underlying atomistic fragments. The resolution of coarse-graining can be varied through both steps, with lower resolutions assigning larger groups of atoms to single beads and employing fewer transferable bead types for interactions.

The hierarchical approach employs multiple coarse-grained (CG) models with varying resolutions, all using the same atom-to-bead mapping but differing in the assignment of transferable bead types [31]. Higher-resolution models feature more bead types, capturing finer chemical details while still reducing combinatorial complexity compared to the atomistic level. This reduction enables enumeration of all possible CG molecules corresponding to specific regions of chemical space at each resolution. Critically, the hierarchical model design allows systematic mapping of higher-resolution molecules to lower resolutions, creating an interconnected framework for navigating chemical space.

Table: Coarse-Graining Resolution Levels and Characteristics

| Resolution Level | Number of Bead Types | Chemical Detail | Combinatorial Complexity | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Resolution | Fewer bead types | Limited structural information | Reduced complexity | Broad exploration |

| Medium Resolution | Moderate bead types | Balanced detail | Moderate complexity | Guided optimization |

| High Resolution | More bead types (e.g., 96 in Martini3) | Fine chemical details | Higher complexity | Detailed exploitation |

Latent Space Representation and Bayesian Optimization

The transformation of discrete molecular structures into continuous latent representations represents a crucial step in enabling efficient chemical space exploration [31]. This encoding is typically achieved through graph neural network (GNN)-based autoencoders, with each coarse-graining resolution encoded separately. The resulting smooth latent space ensures meaningful molecular similarity measures essential for subsequent Bayesian optimization, where molecules with similar properties are positioned close to each other in the latent representation.

Bayesian optimization operates within these latent spaces, using molecular dynamics simulations to calculate target free energies of coarse-grained compounds [31]. The multi-level approach effectively balances exploration and exploitation across resolutions, with lower resolutions facilitating broad exploration of chemical neighborhoods and higher resolutions enabling detailed optimization. This Bayesian framework provides an intuitive mechanism for combining information from different resolutions into the optimization process, relating to multi-fidelity BO approaches but utilizing varying coarse-graining complexities rather than different evaluation costs [31].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Hierarchical Coarse-Grained Models

Purpose: To define multiple coarse-grained models with varying resolutions for representing chemical space.

Materials and Reagents:

- Atomistic molecular structures

- Coarse-graining software (e.g., Martini3 [31])

- Computational resources for molecular dynamics simulations

Procedure:

- Define High-Resolution Model: Begin with establishing the high-resolution CG model, specifying available bead types based on relevant elements and chemical fragments from atomistic chemical space. The Martini3 CG model with 32 bead types per bead size (96 total, excluding water and divalent ions) serves as an appropriate starting point [31].

- Establish Medium and Low Resolutions: Create medium and low-resolution models using the same atom-to-bead mapping as the high-resolution model, but with progressively fewer bead types. This ensures systematic mapping between resolutions.

- Validate Transferability: Confirm that interaction parameters remain transferable across the chemical space of interest, enabling consistent force field application.

- Enumerate CG Molecules: For each resolution level, enumerate all possible CG molecules corresponding to the target region of chemical space, leveraging the reduced complexity at lower resolutions.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If transferability validation fails, review bead type definitions and ensure consistent mapping conventions.

- For enumeration challenges at higher resolutions, consider constraining the chemical space or employing sampling rather than exhaustive enumeration.

Protocol 2: Latent Space Embedding of Coarse-Grained Structures

Purpose: To embed coarse-grained structures into a continuous latent space for Bayesian optimization.

Materials and Reagents:

- Enumerated CG structures from Protocol 1

- Graph neural network-based autoencoder framework

- Computational resources for deep learning

Procedure:

- Structure Representation: Represent each CG molecule as a graph where nodes correspond to beads and edges represent connections.

- Encoder Training: Train separate GNN-based encoders for each resolution level to map CG structures to latent vectors. Use reconstruction loss to ensure meaningful representations.

- Latent Space Validation: Verify that the latent space preserves chemical similarity by measuring distances between related molecular structures.

- Smoothness Assessment: Confirm the latent space provides smooth transitions between molecular structures, enabling effective Bayesian optimization.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If reconstruction accuracy is poor, increase encoder capacity or adjust hyperparameters.

- For inadequate chemical similarity preservation, consider incorporating metric learning approaches into the training objective.

Protocol 3: Multi-Level Bayesian Optimization for Molecular Discovery

Purpose: To identify optimal molecular compounds through multi-level Bayesian optimization.

Materials and Reagents:

- Latent space representations from Protocol 2

- Molecular dynamics simulation software

- Free energy calculation methods (e.g., thermodynamic integration)

- Bayesian optimization framework

Procedure: