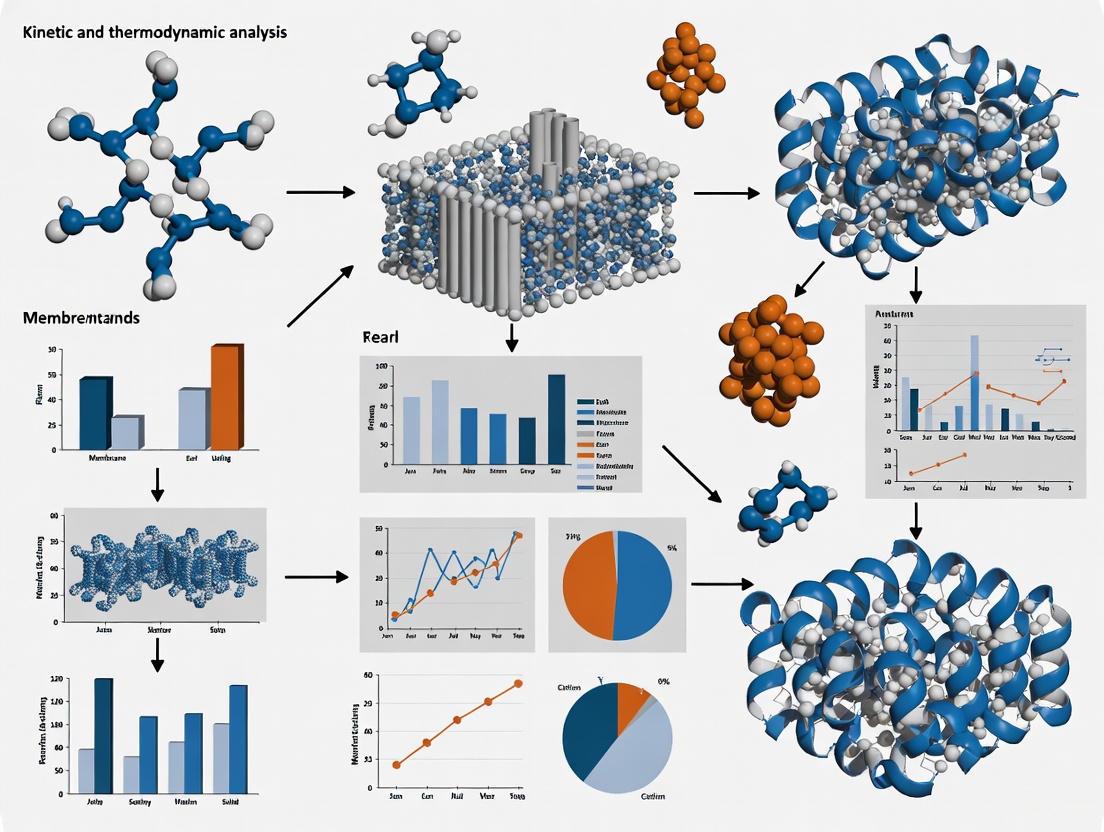

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis of Membrane Formation: Principles, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the kinetic and thermodynamic principles governing polymeric membrane formation, primarily via phase inversion processes.

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis of Membrane Formation: Principles, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the kinetic and thermodynamic principles governing polymeric membrane formation, primarily via phase inversion processes. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational theories of phase separation, details advanced modeling and experimental methodologies for membrane fabrication, and presents systematic frameworks for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing insights from foundational concepts, practical applications, and comparative validation techniques, this review serves as a strategic guide for rationally designing next-generation membranes with tailored properties for advanced separations, drug delivery systems, and other biomedical applications.

The Core Principles: Unraveling Thermodynamics and Kinetics in Membrane Formation

Phase inversion is a fundamental demixing process that transforms a homogeneous polymer solution into a solid, porous membrane in a controlled manner [1]. This process is the cornerstone of modern polymeric membrane fabrication, enabling the production of membranes with specific morphologies for a vast range of applications, from water treatment and desalination to biomedical uses and energy storage [2] [3]. The core principle involves the strategic destabilization of a thermodynamically stable polymer solution, leading to its separation into a polymer-lean phase (which forms the membrane pores) and a polymer-rich phase (which forms the solid matrix) [3]. The method of destabilization defines the primary types of phase inversion processes: Non-Solvent Induced Phase Separation (NIPS), Thermally Induced Phase Separation (TIPS), Vapor-Induced Phase Separation (VIPS), and Evaporation Induced Phase Separation (EIPS).

The final membrane's morphology—whether dense, porous, symmetric, or asymmetric—is critically determined by the complex interplay between thermodynamics and kinetics during the phase separation [4]. Thermodynamics, often represented by phase diagrams, dictates the equilibrium conditions for phase separation, such as the binodal and spinodal curves. Kinetics, on the other hand, governs the rate at which the system achieves this new equilibrium, influenced by factors like mass and heat transfer rates, which in turn are controlled by processing parameters [4]. A profound understanding of both aspects is essential for tailoring membrane structure and performance to meet specific application requirements.

Process Fundamentals, Protocols, and Morphological Control

This section details the core principles, standard experimental protocols, and the resulting morphologies for each phase inversion process. The following workflow outlines the logical relationship and key decision points for selecting and executing these fundamental fabrication methods.

Non-Solvent Induced Phase Separation (NIPS)

Fundamentals: The NIPS process, also known as Liquid-Induced Phase Separation (LIPS), is one of the most prevalent methods for fabricating polymeric membranes [1]. It was established by Loeb and Sourirajan and involves the immersion of a homogeneous polymer casting solution into a coagulation bath containing a non-solvent [4]. Phase separation is triggered by the rapid exchange of solvent and non-solvent across the solution-bath interface. The mass transfer dynamics during this exchange are the primary kinetic factor controlling the membrane's final structure [4]. Typically, NIPS produces asymmetric membranes with a dense top layer and a porous, often finger-like, sublayer [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Polymer Dope Solution Preparation. Prepare a homogeneous casting solution by dissolving a specific polymer (e.g., Polyethersulfone/PES, Polysulfone/PS, or Polyvinylidene Fluoride/PVDF) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone/NMP, N,N-Dimethylacetamide/DMAc, or Dimethylformamide/DMF) [4] [2]. Additives like diethylene glycol (DEG) may be incorporated to modulate thermodynamics or act as pore-formers [5]. The solution must be stirred thoroughly until it becomes clear and homogeneous, then degassed to remove air bubbles.

- Step 2: Film Casting. Pour the degassed polymer solution onto a clean, flat substrate (e.g., a glass plate). Use a casting knife (doctor blade) with a precisely controlled gap (e.g., 200 μm) to spread the solution into a uniform thin film.

- Step 3: Immersion Precipitation. Immediately immerse the glass plate with the cast film into a coagulation bath filled with a non-solvent (typically deionized water or an alcohol-water mixture) [1]. The bath temperature should be kept constant (e.g., room temperature, 25°C).

- Step 4: Solvent Exchange and Membrane Formation. Allow the solvent-non-solvent exchange to proceed for a sufficient time (e.g., 24 hours) to ensure complete precipitation of the polymer and removal of residual solvent.

- Step 5: Post-Treatment. Remove the formed membrane from the bath and wash it extensively with deionized water to leach out all remaining solvent. Finally, dry the membrane under controlled conditions (e.g., between filter papers at room temperature).

Thermally Induced Phase Separation (TIPS)

Fundamentals: The TIPS process, developed by Castro, relies on a change in temperature to induce phase separation [4]. A homogeneous polymer solution is prepared at a high temperature using a diluent (a solvent with a high boiling point). Phase separation is then triggered by cooling the solution, which reduces the polymer's solubility in the diluent [4] [3]. The primary mechanism is heat transfer, and the cooling rate is a critical kinetic parameter that strongly influences the resulting crystalline structure and pore size distribution [4]. TIPS is particularly suitable for polymers that are difficult to dissolve at room temperature and is known for producing membranes with high porosity and excellent mechanical strength [4] [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: High-Temperature Homogenization. Mix the polymer (e.g., semi-crystalline polymers like PP or PVDF) with a high-boiling-point diluent (e.g., dioctyl phthalate) in a sealed vessel. Heat the mixture above the melting point of the polymer or the cloud point of the solution (e.g., 180-250°C) with continuous stirring until a homogeneous solution is obtained [4].

- Step 2: Casting or Extrusion. Cast the hot solution onto a support or extrude it through a die to form a sheet or hollow fiber.

- Step 3: Controlled Cooling. Immediately transfer the cast film or fiber into a cooling bath or environment set to a specific temperature below the phase separation threshold. The cooling rate must be precisely controlled (e.g., quench cooling vs. slow cooling).

- Step 4: Diluent Extraction. After solidification, immerse the membrane in a bath of a diluent-extracting solvent (e.g., ethanol or hexane) to remove the primary diluent.

- Step 5: Drying. Dry the membrane to remove the extraction solvent, resulting in a microporous structure.

Vapor-Induced Phase Separation (VIPS)

Fundamentals: In the VIPS process, a cast polymer film is exposed to an atmosphere containing vapor of a non-solvent (typically water vapor in humid air) instead of being immersed in a liquid bath [3] [1]. The vapor penetrates the film, gradually increasing the non-solvent concentration until phase separation occurs [5]. The key distinction from NIPS is the slower mass transfer kinetics, as the diffusion of vapor is much slower than liquid penetration [3]. This allows for better control over the phase separation process, often leading to the formation of a porous surface layer and a bicontinuous, sponge-like sublayer without large macrovoids, which enhances mechanical strength [5] [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Polymer Solution Preparation. Prepare a homogeneous polymer solution as described in the NIPS protocol.

- Step 2: Film Casting. Cast the solution onto a substrate as in the NIPS protocol.

- Step 3: Vapor Exposure. Place the cast film into a climate-controlled chamber where temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and exposure time (Vt, e.g., from 10 seconds to 10 minutes) are precisely regulated [5] [3]. This is the critical VIPS step.

- Step 4: Coagulation Bath Immersion (Optional). In a combined VIPS-NIPS process, the film is subsequently immersed in a liquid coagulation bath to complete the solidification [5].

- Step 5: Washing and Drying. Wash and dry the membrane as in previous protocols.

Evaporation Induced Phase Separation (EIPS)

Fundamentals: The EIPS process, while sometimes confused with VIPS, operates on a different principle. In EIPS, the initial polymer solution contains a volatile solvent and a non-volatile non-solvent [3]. Phase separation is induced by the evaporation of the volatile solvent, which enriches the solution in the non-solvent, thereby destabilizing it and causing the polymer to precipitate [3]. The rate of solvent evaporation is the critical kinetic factor controlling membrane formation in EIPS. This process is distinct from VIPS, where the non-solvent enters the film from the vapor phase; in EIPS, the non-solvent is already present in the casting solution, and the solvent leaves [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Solution Preparation with Non-Solvent. Dissolve the polymer in a mixture of a volatile solvent and a non-volatile non-solvent.

- Step 2: Film Casting. Cast the solution onto a substrate.

- Step 3: Controlled Evaporation. Expose the cast film to a controlled environment (e.g., under a fume hood or in a chamber with specific air flow) to allow the volatile solvent to evaporate. The evaporation time and temperature are critical parameters.

- Step 4: Solidification. The film solidifies as the solvent evaporates and the non-solvent concentration passes the threshold for phase separation.

- Step 5: Post-Treatment. Depending on the residual solvents, a washing step may be required before final drying.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Phase Inversion Processes

| Process | Induction Mechanism | Key Controlling Parameters | Typical Membrane Morphology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIPS/LIPS | Liquid non-solvent influx [4] | Solvent/non-solvent pair, bath composition & temperature, polymer concentration [4] [2] | Asymmetric with dense skin & finger-like pores [5] | Simple, efficient, wide applicability [4] | Rapid kinetics can form undesirable macrovoids; often dense skin limits flux [5] |

| TIPS | Temperature decrease [4] | Cooling rate, polymer/diluent thermodynamics, crystallization temperature [4] | Symmetric or asymmetric with spherical or bicontinuous pores | Good for crystalline polymers; high porosity; narrow pore distribution [4] | High energy consumption; limited diluent choices [5] |

| VIPS | Vapor non-solvent influx [3] | Exposure time (Vt), humidity, temperature, vapor composition [5] [1] | Sponge-like, bicontinuous structure; porous surface [5] | Highly controllable process; improved mechanical strength [5] [3] | Slow process; requires strict environmental control [5] |

| EIPS | Solvent evaporation [3] | Solvent volatility, evaporation rate, non-solvent concentration [3] | Varies (dense to porous) | Simplicity | Limited to specific solvent/non-solvent systems; can form dense membranes [3] |

Table 2: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Considerations in Phase Inversion

| Aspect | NIPS | TIPS | VIPS | EIPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Thermodynamic Driver | Change in chemical potential due to non-solvent mixing | Change in solubility due to temperature shift | Change in chemical potential due to vapor absorption | Change in composition due to solvent loss |

| Primary Kinetic Factor | Rate of solvent/non-solvent exchange (mass transfer) [4] | Rate of cooling (heat transfer) [4] | Rate of vapor absorption (mass transfer) [3] | Rate of solvent evaporation |

| Impact of Slow Kinetics | Formation of a denser skin layer, delayed demixing | Larger pore sizes, more crystalline structures | Formation of bicontinuous, sponge-like structures [5] | Denser, more homogeneous structures |

| Impact of Fast Kinetics | Formation of macrovoids, instantaneous demixing [5] | Smaller pores, amorphous structures | Limited by vapor diffusion, less common | Rapid skin formation, possible defect creation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Selecting appropriate materials is fundamental to successfully fabricating membranes via phase inversion. The following table lists essential reagents and their functions in the preparation of casting solutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phase Inversion Membrane Fabrication

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in Membrane Fabrication | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers | Polyethersulfone (PES), Polysulfone (PS), Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF), Cellulose Acetate (CA) [2] [1] | Forms the structural matrix of the membrane. | Molecular weight, concentration, and inherent properties (hydrophobicity, crystallinity) dictate membrane mechanics and thermodynamics. |

| Solvents | N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), N,N-Dimethylacetamide (DMAc), Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [4] [2] | Dissolves the polymer to create a homogeneous casting solution. | Polarity, boiling point, volatility, and environmental/safety profile are critical. Solvent power affects solution viscosity and thermodynamics. |

| Non-Solvents | Water, Ethanol, Methanol, Diethylene Glycol (DEG) [5] [4] | Induces phase separation in NIPS/VIPS; can be used as an additive in the dope to modify thermodynamics. | Miscibility with the solvent is key. As an additive, it can act as a pore-former and shift the phase diagram. |

| Coagulation Media | Deionized Water, Alcohol-Water Mixtures | The liquid bath (for NIPS) that accepts the solvent and provides the non-solvent for exchange. | Composition and temperature directly impact the rate of phase separation and final morphology [4]. |

| Additives (Polymeric) | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) [1] | Acts as a pore-former and viscosity modifier; can enhance hydrophilicity and antifouling properties. | Molecular weight and concentration are crucial; often leaches out during coagulation, creating additional porosity. |

| Additives (Inorganic) | Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂), Silver Nanoparticles (Ag), Graphene Oxide (GO) [6] [1] | Creates mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) to enhance properties like mechanical strength, permeability, hydrophilicity, or impart antimicrobial activity. | Dispersion stability within the polymer solution is a major challenge to prevent agglomeration and defects. |

Advanced and Combined Processes

To overcome the limitations of individual methods, researchers often combine phase inversion processes. A prominent example is the dual VIPS-RTIPS technique. RTIPS (Reverse Thermally Induced Phase Separation) relies on a system with a Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST), where the solution is homogeneous at low temperatures and demixes upon heating. In a combined approach, the VIPS stage first constructs a porous selective layer under controlled humidity, while the subsequent RTIPS stage (immersion in a warm coagulation bath) efficiently forms a high-strength, spongy support layer [5]. This synergy allows for independent optimization of the surface and bulk structures, resulting in membranes with high flux, superior rejection rates, and improved mechanical properties [5].

Another advanced strategy is the integration of additives via physical blending to create antifouling membranes. In this one-step method, antifouling materials (e.g., hydrophilic polymers, metal nanoparticles, or carbon-based nanomaterials) are blended with the main matrix polymer prior to casting and phase inversion [1]. This approach is highly flexible and can be adapted for NIPS, VIPS, or TIPS processes to create membranes with tailored surface properties that resist the adsorption of foulants like proteins and natural organic matter [1].

Phase diagrams are indispensable tools for understanding the multi-scale behaviour of complex systems, serving as a bridge between the molecular interactions within a mixture and its macroscopic properties [7]. In the context of membrane formation research, a thorough comprehension of ternary phase diagrams is critical. The thermodynamic and kinetic pathways traversed during phase inversion processes directly dictate the final membrane morphology, which in turn controls performance parameters such as permeability, selectivity, and mechanical strength [4]. During membrane fabrication via techniques like Non-Solvent Induced Phase Separation (NIPS) and Thermally Induced Phase Separation (TIPS), a homogeneous polymer solution is systematically driven into a metastable state, leading to its separation into polymer-rich and polymer-lean phases [4] [8]. The boundaries of these stability regions are demarcated by the binodal and spinodal curves within the ternary phase diagram.

The binodal curve defines the boundary between the metastable and immiscible regions, representing points where the chemical potentials of all components are equal in both coexisting phases. The spinodal curve, lying within the binodal envelope, marks the boundary of thermodynamic instability, where phase separation occurs spontaneously via spinodal decomposition without an activation energy barrier [7] [9]. The region between these curves is metastable, where phase separation proceeds by a slower nucleation and growth mechanism. Accurately mapping these curves is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for predicting and controlling membrane structure. This application note details advanced methodologies for the computation and experimental determination of these critical elements, providing a structured protocol for researchers engaged in the kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of membrane formation.

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Methods

Thermodynamic Basis of Phase Separation

The phase behaviour of a ternary system comprising polymer, solvent, and non-solvent is governed by the Gibbs free energy of mixing, ΔGm. For a ternary system, the extended Flory-Huggins theory provides a robust framework for calculating this energy surface [8]:

[ \Delta Gm = RT(n1 \ln \phi1 + n2 \ln \phi2 + n3 \ln \phi3 + g{12}n1\phi2 + g{13}n1\phi3 + g{23}n2\phi3) ]

Here, (ni) and (\phii) are the number of moles and volume fraction of component (i), respectively, (R) is the gas constant, (T) is the absolute temperature, and (g_{ij}) are the binary interaction parameters between components (i) and (j) [8]. The geometry of the ΔGm surface dictates all phase behaviour. The binodal curve is derived from the common tangent planes to this surface, ensuring equality of chemical potentials for all components across two coexisting phases. The spinodal curve is defined by the locus of points where the Gibbs free energy surface becomes concave, satisfying the condition that the second derivative of ΔGm with respect to composition is zero [7] [8].

A Geometrical Approach for Curve Computation

Traditional methods for computing binodal curves often involve mesh-based iterative algorithms, which can be computationally intensive and sensitive to initial guesses. A powerful simplification reformulates the problem in a 4D extended space, where each phase is associated with its own configuration space. Within this framework, the phase coexistence conditions define a smooth curve, and the binodal curve computation is reduced to the numerical integration of a system of four ordinary differential equations (ODEs) [7]. This differential path-following algorithm offers high accuracy and simplifies the process of tracing the entire binodal curve and its associated tie-lines. The spinodal curve can be computed similarly via the integration of a vector field in the 2D composition plane [7]. This method can be implemented with various thermodynamic models, including the Flory-Huggins model, NRTL, or UNIQUAC.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for this geometrical computation method.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for the key experimental and computational procedures required to construct and analyze ternary phase diagrams for membrane-forming systems.

Protocol 1: Determination of the Cloud Point Curve (Binodal)

The cloud point curve, which approximates the binodal, is determined experimentally via the titration method.

- Objective: To experimentally locate the composition at which a homogeneous polymer solution undergoes phase separation upon addition of a non-solvent.

- Materials:

- Polymer (e.g., Polyethersulfone - PES)

- Solvent (e.g., N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone - NMP, or N,N-Dimethylacetamide - DMAc)

- Non-solvent (e.g., double-distilled water)

- Procedure:

- Prepare a series of polymer solutions with concentrations typically ranging from 1 to 30 wt% polymer in solvent [8].

- Place a known mass (e.g., 5 g) of a clear polymer solution in a sealed vial maintained at constant temperature.

- Under continuous stirring, titrate the solution with the non-solvent (water) using a micro-dropper or burette.

- After each addition, allow the solution to equilibrate. The endpoint is reached when the solution turns permanently turbid.

- Record the mass of non-solvent added. The composition at the cloud point is calculated from the masses of all components.

- Repeat the titration for all prepared polymer solutions to obtain a set of cloud point compositions.

- Data Analysis: The cloud point compositions are plotted on a ternary diagram to construct the experimental binodal curve.

Protocol 2: Computation of Phase Diagrams using Flory-Huggins Model

This protocol outlines the steps for theoretically calculating the binodal and spinodal curves.

- Objective: To compute the ternary phase diagram from a thermodynamic model by determining the binary interaction parameters and solving the phase equilibrium equations.

- Materials: Software capable of numerical computation (e.g., MATLAB, Python with SciPy).

- Procedure:

- Determine Binary Interaction Parameters ((g{ij})):

- (g{12}) (non-solvent/solvent): Obtain from vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) data of the binary mixture. It is often concentration-dependent [8].

- (g{13}) (non-solvent/polymer) & (g{23}) (solvent/polymer): These can be determined by fitting the Flory-Huggins model to experimental binary cloud point data or from inverse gas chromatography measurements. They are often considered concentration-independent [8].

- Compute the Binodal Curve:

- Implement the ODE-based geometrical method described in Section 2.2 [7]. Alternatively, use a traditional algorithm that solves the set of non-linear equations expressing chemical potential equality for the two coexisting phases.

- The initial condition for integration can be found by solving the phase equilibrium problem on the binary edges of the ternary diagram (e.g., the solvent/polymer axis).

- Compute the Spinodal Curve:

- Locate the Critical Point: The critical point is located at the point of confluence of the binodal and spinodal curves.

- Determine Binary Interaction Parameters ((g{ij})):

Protocol 3: Tie-Line Determination and Lever Rule Application

- Objective: To determine the composition of coexisting phases and their relative amounts at a given overall composition within the two-phase region.

- Background: A tie-line is a straight line connecting two coexisting phases (nodes) on the binodal curve. All overall compositions lying on the same tie-line will separate into the same two phases, but in different relative amounts.

- Procedure for Determination:

- Tie-lines can be determined experimentally by allowing a mixture of known overall composition to reach full equilibrium, then separately analyzing the compositions of the two coexisting phases (e.g., using spectroscopy or chromatography) [10].

- Theoretically, tie-lines are a direct output of the ODE-based binodal computation, as each point on the generalized 4D curve projects onto a pair of conjugate phase compositions [7].

- Lever Rule Application:

- For an overall mixture at point M on a tie-line connecting phases α and β, the fraction of the α-phase is given by the length of Mβ divided by the total tie-line length αβ. The fraction of the β-phase is given by αM/αβ [10]. This rule is vital for predicting the yield of polymer-rich phase during membrane formation.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Thermodynamic Interaction Parameters

The accuracy of a theoretically calculated phase diagram is entirely dependent on the quality of the binary interaction parameters. The table below summarizes reported parameters for common membrane-forming systems.

Table 1: Flory-Huggins Interaction Parameters for Selected Ternary Systems at 25°C [8].

| System (Non-Solvent (1)/ Solvent (2)/ Polymer (3)) | (g_{12}) (Conc. Dependent) | (g_{13}) | (g_{23}) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water / DMAc / PES | Polynomial from VLE data | ~2.6 | ~0.6 |

| Water / NMP / PES | Polynomial from VLE data | ~2.6 | ~0.45 |

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Phase Diagram Analysis in Membrane Research.

| Item | Function / Role | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer | The membrane-forming material; its interaction with solvent and non-solvent determines the solution thermodynamics. | Polyethersulfone (PES), Polysulfone (PSf), Polyacrylonitrile (PAN), Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) [4] [8] |

| Solvent | Dissolves the polymer to form the initial casting solution. | NMP, DMAc, DMF, DMSO [4] |

| Non-Solvent | Induces phase separation by reducing the solvent power of the continuous phase. | Water, lower alcohols [4] [8] |

| Probes / Additives | Used to study kinetics (e.g., exchange rate) or to detect phases via fluorescence, ESR, etc. [10]. | Fluorescent dyes (e.g., DPH), spin probes. |

Pathway to Membrane Morphology

The journey from a homogeneous casting solution to a solid membrane is governed by the path of the system's composition in the phase diagram. The following diagram visualizes this critical relationship, linking thermodynamic stability to kinetic pathways and final morphology.

As illustrated, the composition path during membrane formation is critical. In NIPS, the path is driven by mass transfer, typically moving from a stable region into the metastable region, leading to nucleation and growth and often resulting in asymmetric membranes with a dense skin and porous sub-layer [4]. In TIPS, the path is driven by heat transfer, often crossing the spinodal boundary and leading to spinodal decomposition, which typically produces a more isotropic, bicontinuous structure [4]. The final membrane morphology—whether desired or not—is a direct record of this kinetic and thermodynamic journey.

The spontaneous formation and stability of membrane structures, along with the conformational changes of proteins within them, are fundamentally governed by the laws of thermodynamics. The Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) serves as the central quantitative indicator that predicts the spontaneity and driving forces of these processes. A negative ΔG value signifies a thermodynamically favorable, spontaneous process, whereas a positive ΔG indicates a non-spontaneous one that requires energy input. In membrane biology, the total free energy change (ΔGtotal) is a composite of multiple contributing factors, including the hydrophobic effect, lipid packing deformations, electrostatic interactions, and the configurational entropy of both lipids and proteins [11] [12] [13].

Understanding these principles is not merely an academic exercise; it provides a powerful framework for rational design in various applied fields. In drug development, the thermodynamic profile of a molecule's interaction with the membrane often dictates its efficacy and mechanism of action [14]. In synthetic biology, the goal of constructing functional artificial cells or protocells relies on controlling the spontaneous self-assembly of lipid bilayers and the incorporation of membrane proteins [15] [16]. Furthermore, in bioseparations and membrane technology, the thermodynamics of phase separation dictates the morphology and performance of synthetic membranes [4]. This protocol details the application of thermodynamic principles to analyze a key biological process: the lipid-modulated dimerization of a membrane protein.

Theoretical Framework: Energetics of Membrane Protein Oligomerization

The oligomerization equilibrium of a membrane protein, such as the dimerization of the CLC-ec1 antiporter, provides an exemplary model for quantifying the thermodynamic driving forces in a membrane environment [12] [17]. The overall reaction can be represented as: 2Monomer ⇌ Dimer

The Gibbs Free Energy change for this process (ΔGdimer) is negative, indicating spontaneity, and is influenced by the lipid composition of the membrane. The total free energy change can be deconstructed into its primary components [11] [12] [13]:

- ΔGprotein: The free energy change from direct protein-protein interactions at the dimer interface.

- ΔGmembrane-deform: The free energy penalty paid to deform the lipid bilayer around the monomeric protein, which is relieved upon dimerization. This includes:

- ΔGcurvature: The energy cost of inducing membrane curvature.

- ΔGthickness: The energy cost associated with hydrophobic mismatch.

- ΔGlipid-solvation: The free energy change arising from the preferential solvation of the protein surface by different lipid species. This is a key regulatory mechanism, where certain lipids (e.g., short-chain lipids like DLPC) can become enriched at the protein interface without specific binding, thereby altering the conformational equilibrium [12] [17].

The relationship is summarized as: ΔGdimer = ΔGprotein + ΔGmembrane-deform + ΔGlipid-solvation

Table 1: Quantitative Contributions to Membrane Protein Dimerization Free Energy

| Free Energy Component | Description | Representative Value | Experimental/Computational Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGcurvature | Energetic penalty for bending the membrane around a monomer. | -79.2 ± 5.2 kcal mol⁻¹ (relieved upon dimerization) [11] | Helfrich continuum model analysis of MD simulations [11] |

| ΔGthickness | Energetic penalty for hydrophobic mismatch. | -2.8 ± 2.0 kcal mol⁻¹ (relieved upon dimerization) [11] | Elastic model analysis of membrane thickness deformations [11] |

| ΔGlipid-solvation | Contribution from preferential solvation by short-chain (DL) lipids. | Favorable for monomer (inhibits dimerization) [12] | Free energy calculations from Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CGMD) [12] |

The following diagram illustrates the thermodynamic cycle of membrane protein dimerization, highlighting the key energetic states and the role of lipid solvation.

Diagram 1: Thermodynamic cycle of protein dimerization in a lipid membrane. The pathway shows how the dimerization free energy (ΔGdimer) is modulated by the preferential solvation of the protein interface by specific lipids (e.g., short-chain DL lipids), which stabilizes the monomeric state and inhibits dimerization.

Application Note: Quantifying Lipid Regulation of CLC-ec1 Dimerization

Background and Objective

The CLC-ec1 chloride/proton antiporter is a model protein for studying the thermodynamics of membrane protein oligomerization. A key finding is that its dimerization is inhibited by the presence of short-chain phospholipids like 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLPC) in a concentration-dependent, non-saturating manner [12] [17]. This suggests a regulatory mechanism distinct from specific, high-affinity lipid binding. The objective of this application note is to provide a protocol for quantifying this effect and to demonstrate that the underlying mechanism is preferential lipid solvation—a dynamic process where the protein surface is transiently enriched in certain lipid species due to differential solvation energetics, rather than long-lived binding [12].

Key Principles and Mechanisms

The inhibition of CLC-ec1 dimerization by DLPC is a classic example of how membranes regulate protein function through thermodynamics. The monomeric protein exposes a membrane-facing surface that is geometrically and chemically challenging to solvate, creating a local membrane defect [12]. This defect is characterized by thinned membrane and requires lipids to tilt, incurring a substantial bending free energy penalty (ΔGcurvature ≈ 10² kcal mol⁻¹) [11]. Dimerization buries this defective interface, thereby relieving the membrane strain.

Short-chain lipids like DLPC are preferentially enriched at this defective interface in the monomer state because they can more easily accommodate the membrane deformation due to their shorter acyl chains. This preferential solvation lowers the free energy of the monomeric state relative to the dimeric state. Since the dimer buries the interface, it derives less solvation benefit from the DLPC. Consequently, an increase in DLPC concentration shifts the equilibrium toward the monomer, inhibiting dimerization without the need for specific binding [12] [17].

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Dimerization Energetics via FCS and CGMD

This integrated protocol combines single-molecule spectroscopy and molecular simulations to quantify the free energy of dimerization and its modulation by lipid composition.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Membrane Protein Thermodynamics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Experiment | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CLC-ec1 Protein (single-Cys mutant) | Target membrane protein for dimerization studies. Allows for site-specific fluorescent labeling. | e.g., N235C mutant for labeling with maleimide-functionalized dyes [12] [13]. |

| Alexa Fluor 488/647 Maleimide | Fluorophore for labeling protein. Enables detection and quantification via Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS). | Bright, photostable dye suitable for single-molecule detection [13]. |

| Lipids (POPC, DLPC) | Components of the model lipid bilayer. POPC provides a background matrix; DLPC is the modulating short-chain lipid. | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) & 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLPC) [12]. |

| Large Unilamellar Vesicles (LUVs) | Model membrane system for experiments. | Prepared by extrusion (diameter ~0.1 μm) to ensure stable, uniform bilayers and avoid artifacts from high curvature [13]. |

| FCS Instrumentation | Confocal microscope-based system to measure diffusion times of fluorescent species. | e.g., MicroTime 200 (PicoQuant) or Alba FCS workstation (ISS). Measures protein dimerization via diffusion shifts [13]. |

Step-by-Step Procedures

Part A: Sample Preparation and Biophysical Measurement

- Protein Labeling and Purification: Label the single-cysteine mutant of CLC-ec1 with Alexa Fluor 488 or 647 maleimide following standard protocols. Purify the labeled protein to remove free dye [13].

- Liposome Preparation: Create lipid mixtures of POPC and DLPC at varying molar ratios (e.g., 100:0, 95:5, 90:10). Prepare LUVs in the desired buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) via extrusion through a 100 nm polycarbonate membrane [13].

- FCS Measurement: a. Dilute the labeled CLC-ec1 protein to a concentration of 0.5–6 nM in the presence of a saturating concentration of LUVs (e.g., 1 mM total lipid) to ensure all protein is membrane-bound. b. Load the sample into the FCS instrument and collect the autocorrelation function, G(τ), at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C). c. Fit the autocorrelation data using a model for two diffusing species (monomer and dimer) to determine the fraction of dimeric protein [13].

- Data Analysis: a. From the dimer fraction, calculate the equilibrium constant Kdimer = [Dimer]/[Monomer]². b. Calculate the standard free energy of dimerization using the fundamental relation: ΔGdimer = -RT ln(Kdimer), where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin. c. Plot ΔGdimer as a function of the DLPC mol% in the membrane to quantify the inhibitory effect.

Part B: Computational Validation via Molecular Dynamics

- System Setup: Build simulation systems of the CLC-ec1 monomer and dimer embedded in a symmetric bilayer of pure POPC and a POPC/DLPC mixture. Use a coarse-grained (CG) forcefield such as Martini for efficient sampling [12].

- Simulation Execution: Run unrestrained MD simulations for multiple replicates, ensuring each system reaches equilibrium (typically hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds in CG time).

- Lipid Dynamics Analysis: a. Calculate the 2D density maps of DLPC around the protein to visualize and confirm its enrichment at the dimerization interface of the monomer. b. Quantify the enrichment by calculating the normalized local concentration of DLPC in the first solvation shell versus the bulk membrane [12].

- Solvation Free Energy Calculation: Employ free energy perturbation (FEP) or thermodynamic integration (TI) methods to compute the difference in solvation free energy of the monomer and dimer in POPC versus the POPC/DLPC mixture. This computationally intensive step directly yields ΔGlipid-solvation and should match the trend observed experimentally [12].

The workflow for the integrated experimental-computational approach is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for measuring and validating the thermodynamics of membrane protein dimerization. The protocol combines Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) for experimental free energy measurement with Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CGMD) for molecular-level analysis.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

- Interpreting FCS Data: A successful experiment will show a clear shift in the autocorrelation curve towards faster diffusion times as the DLPC fraction increases, indicating a higher proportion of the smaller, monomeric species. The calculated ΔGdimer will become less negative (or even positive) with increasing DLPC, quantitatively demonstrating the inhibitory effect [13].

- Interpreting MD Data: The lipid density maps should show a clear "halo" of DLPC enrichment around the monomer's solvent-exposed dimerization interface. This enrichment occurs without forming stable, long-lived bonds, manifesting as a dynamic cloud of lipids. The computed ΔGlipid-solvation should be favorable for the monomer in the DLPC mixture, consistent with the experimental observation that DLPC inhibits dimerization [12].

- Distinguishing Mechanisms: The non-saturating, concentration-dependent effect of DLPC on ΔGdimer is a key signature of preferential solvation. This contrasts with specific binding, which would show saturable behavior at high lipid concentrations, following a hyperbolic binding curve [12] [17].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

- Low FCS Signal-to-Noise: Ensure protein labeling efficiency is high (>90%) and that free dye has been completely removed. Use fluorophores known for high photon counts and photostability (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647) [13].

- No Observed Diffusion Shift: Verify that the protein is fully membrane-associated by using a sufficient lipid concentration. Confirm that the pH and buffer conditions are appropriate for CLC-ec1 stability and function.

- Poor Lipid Mixing in Simulations: Ensure the simulation box is large enough and that the simulation time is sufficient for lipid lateral diffusion to achieve proper mixing. Replicate simulations are essential to confirm observed trends.

This application note establishes a robust framework for applying thermodynamic principles to analyze membrane protein interactions. By quantifying the Gibbs Free Energy of dimerization and demonstrating its regulation through the preferential solvation of specific lipids, we move beyond static structural snapshots to a dynamic, equilibrium understanding of membrane biology.

The implications are broad. In drug development, understanding that membrane composition can allosterically regulate protein equilibria via solvation provides a new axis for drug targeting. For membrane engineering, these principles guide the design of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and synthetic membranes with tailored properties by controlling lipid packing and composition [14] [16]. The integrated experimental-computational approach described here serves as a powerful template for deciphering the complex yet fundamental interplay between membrane proteins and their lipidic environment.

The formation of polymeric membranes via phase inversion is a critical process in separation technology, with applications ranging from water purification to pharmaceutical development. Central to this process is the intricate mass transfer of solvent and non-solvent, which governs the kinetic and thermodynamic pathways leading to the final membrane morphology and performance. This application note details the experimental and computational frameworks for investigating these diffusion phenomena, providing researchers with standardized protocols for the kinetic analysis of membrane formation. Within the broader context of membrane research, understanding these dynamics enables precise control over membrane architecture, facilitating the design of materials with tailored permeability, selectivity, and mechanical properties for specific industrial applications.

Quantitative Data on Diffusion and Morphology

The following tables consolidate key quantitative relationships between process parameters, diffusion characteristics, and resulting membrane properties, as established in experimental studies.

Table 1: Effect of Process Parameters on Diffusion Velocities and Membrane Morphology in ScCO₂ Phase Inversion

| Parameter Variation | Effect on Vo¯ - Vi¯ | Impact on Mean Pore Size | Impact on Porosity | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Polymer Concentration | Decreases [18] | Varies by polymer (e.g., decreases for PMMA; increases for PS, PVDF) [18] | Varies by polymer (e.g., decreases for PMMA; increases for PS) [18] | A lower Vo¯ - Vi¯ promotes the growth of fewer, larger pores, explaining unusual pore size increases with concentration for some polymers [18]. |

| Increased ScCO₂ Pressure | Increases [18] | Decreases [18] | Decreases [18] | A higher Vo¯ - Vi¯ induces more nucleation sites, leading to a finer cellular structure with smaller pores and lower porosity [18]. |

| Increased Temperature | Increases [18] | Decreases [18] | Decreases [18] | Enhanced ScCO₂ in-diffusion velocity at higher temperatures results in a similar morphological trend to increased pressure [18]. |

Table 2: Membrane Properties as a Function of Precipitation Bath Harshness (PVDF-DMAc-Water System)

| DMAc in Precipitation Bath (% wt.) | Mean Pore Size (nm) | Permeance (L m⁻² h⁻¹ bar⁻¹) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Key Morphological Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Pure Water) | ~60 | ~2.8 | ~9 | Standard asymmetric structure [19]. |

| 10-30 | ~150 | ~8.0 | ~9 to 11 | Increased mean pore size and permeance without sacrificing mechanical strength [19]. |

| >30 | ~150 | ~8.0 | ~6 | Appearance of spherulitic structures and degeneration of finger-like pores, reducing mechanical strength [19]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Calculating Average Solvent and Non-Solvent Diffusion Velocities

This protocol outlines a method to calculate the difference between average solvent out-diffusion velocity (Vo¯) and average non-solvent in-diffusion velocity (Vi¯) during phase inversion, based on the work of Wang et al. [18].

3.1.1 Principle

The difference in diffusion velocities, (Vo¯ - Vi¯), can be determined by measuring the dimensional change (thickness) of the polymer film before and after the phase inversion process. This parameter is a critical kinetic indicator for predicting membrane morphology [18].

3.1.2 Materials and Equipment

- Prepared polymer casting solution (e.g., PEI in NMP)

- Supercritical CO₂ unit or liquid non-solvent bath

- Substrate for film casting (e.g., glass plate)

- Doctor blade or film applicator

- Digital micrometer or thickness gauge

- Analytical balance

3.1.3 Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous polymer solution by dissolving the polymer (e.g., Polyetherimide, PEI) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone, NMP). Ensure the solution is thoroughly mixed and degassed.

- Film Casting: Cast the polymer solution onto a clean, flat substrate using a doctor blade to achieve a uniform initial thickness,

L₀. - Phase Inversion: Immediately immerse the cast film into a non-solvent bath (for NIPS) or transfer it to a pressure vessel for supercritical CO₂ (for ScCO₂ phase inversion).

- Membrane Formation: Allow sufficient time for the complete phase separation and solidification of the membrane.

- Thickness Measurement: Carefully retrieve the formed membrane. After drying, measure the final average thickness,

L_T, at multiple points across the membrane. - Process Time Recording: Record the total time,

T, from the initiation of phase inversion (immersion or pressurization) until the membrane structure is fully solidified.

3.1.4 Data Analysis

Calculate the difference between the average diffusion velocities for each experimental condition j using the following formula [18]:

(Vo¯ - Vi¯)j = (L₀ - L_T)j / T_j

Where:

L₀is the initial thickness of the cast solution film (µm)L_Tis the final thickness of the formed membrane (µm)T_jis the total membrane formation time (s)- The result is expressed in µm/s.

A positive value indicates that the solvent is leaving the film faster than the non-solvent is entering, which influences pore nucleation and growth dynamics [18].

Protocol: Investigating the Impact of Precipitation Bath Harshness

This protocol describes a method to systematically study the effect of non-solvent harshness on membrane morphology and properties by modifying the coagulation bath composition [19].

3.2.1 Principle The harshness of the precipitation bath, which governs the rate of phase separation, can be controlled by adding varying amounts of solvent to the non-solvent. This alters the thermodynamics and kinetics of the process, enabling the fabrication of membranes with different pore structures and performance characteristics [19].

3.2.2 Materials and Equipment

- Polymer (e.g., PVDF)

- Solvent (e.g., Dimethyl acetamide, DMAc)

- Non-solvent (e.g., Deionized water)

- Stirring hotplate and magnetic stirrer

- Vacuum oven or desiccator for degassing

- Casting knife and glass plates

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Porosimeter

- Permeability test cell

3.2.3 Procedure

- Dope Solution Preparation: Dissolve PVDF in DMAc to form a homogeneous 15% wt. solution. Heat and stir as needed until the polymer is completely dissolved. Degas the solution to remove air bubbles.

- Coagulation Bath Preparation: Prepare a series of coagulation baths with varying compositions: 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% wt. of DMAc in deionized water.

- Membrane Casting and Immersion: Cast the dope solution on a glass plate with a predefined thickness (e.g., 200 µm). Immediately immerse the cast film along with the plate into the prepared coagulation baths.

- Membrane Post-treatment: After complete phase separation (typically 10-30 minutes), transfer the membrane to a fresh water bath to leach out residual solvent. Finally, dry the membrane under controlled conditions.

- Membrane Characterization:

- Morphology: Analyze the cross-sectional morphology of the membranes using SEM.

- Transport Properties: Measure the pure water permeance (PWP) and mean pore size using a permeability test cell and porosimetry.

- Mechanical Properties: Determine the tensile strength of the membrane samples.

3.2.4 Data Analysis Correlate the composition of the precipitation bath with the measured membrane properties. A harsher bath (lower solvent content) typically leads to instantaneous demixing and finger-like macrovoids, while a softer bath (higher solvent content) promotes delayed demixing and a sponge-like or cellular morphology with different mechanical and transport properties [19].

Visualization of Mass Transfer and Membrane Formation

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key mass transfer phenomena during the Nonsolvent-Induced Phase Separation (NIPS) process.

NIPS Mass Transfer and Demixing Process

This workflow outlines the critical stages of membrane formation via NIPS. The process begins with the immersion of a homogeneous polymer solution into a non-solvent bath, triggering the interdiffusion of solvent (out) and non-solvent (in) [20]. When the system's composition crosses the binodal line on the phase diagram, it becomes metastable and undergoes phase separation into a polymer-rich phase (future matrix) and a polymer-lean phase (future pores) [20] [21]. The subsequent coarsening of these phases is ultimately arrested by solidification (e.g., vitrification or crystallization), locking in the final porous structure [21]. The key morphological outcome is determined by the demixing mechanism, which itself is governed by the relative diffusion velocities: a fast exchange, often corresponding to a high (Vo¯ - Vi¯), leads to instantaneous demixing and finger-like pores, while a slow exchange promotes delayed demixing and a sponge-like structure [18] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Studying Diffusion in Membrane Formation

| Category | Item | Function / Relevance in Diffusion Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Common Polymers | Polyetherimide (PEI) | High-performance polymer; forms cellular pores with ScCO₂ [18]. |

| Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) | Semicrystalline polymer; pore size and morphology highly sensitive to diffusion conditions [19]. | |

| Polyethersulfone (PES) | Common polymer for ultrafiltration membranes; used in NIPS studies with various solvents [22]. | |

| Conventional Solvents | N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) | Strong solvent for many polymers (e.g., PEI, PES); its out-diffusion velocity (Vo) is a key measured parameter [18] [22]. |

| Dimethyl Acetamide (DMAc) | Common solvent for PVDF and PES; used to study thermodynamic affinity and kinetic effects [22] [19]. | |

| Sustainable Solvents | 2-Pyrrolidone (2P) | Readily biodegradable, non-toxic alternative to NMP for PES membranes [22]. |

| Dimethyllactamide (DML) | Bio-derived, non-toxic solvent; potential sustainable alternative for membrane fabrication [22]. | |

| Non-Solvents | Water | Standard liquid non-solvent for NIPS [20]. |

| Supercritical CO₂ (ScCO₂) | Environmentally friendly non-solvent with gas-like diffusivity; allows for rapid, cellular membrane formation [18]. | |

| Polymeric Additives | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Pore-forming agent; alters solution viscosity and diffusive exchange rates, impacting pore size and macrovoid formation [22]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Acts as a polymeric additive to modify kinetics and thermodynamics of phase separation [22]. |

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) has emerged as a fundamental mechanism underlying the formation of membraneless organelles (MLOs) in eukaryotic cells, compartmentalizing biochemical reactions without physical barriers [23]. The kinetic path of LLPS—whether it proceeds through instantaneous or delayed demixing—is critically important for understanding both physiological functions and the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [23] [24] [25]. The kinetic trajectory of LLPS determines the formation, maturation, and potential subsequent liquid-to-solid transition of these biomolecular condensates, which can ultimately lead to pathological aggregation [23] [25].

This application note explores the kinetic profiles of LLPS within the broader context of kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of membrane formation research. We provide a detailed comparative analysis of experimental approaches for inducing and characterizing instantaneous versus delayed phase separation, with specific protocols for studying these processes under near-native conditions. The information presented herein is particularly relevant for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals investigating the role of LLPS in cellular organization and disease pathogenesis.

Kinetic Pathways in LLPS

The demixing of protein solutions via LLPS can follow distinct kinetic pathways, broadly classifiable as instantaneous or delayed, depending on experimental conditions and protein properties. Instantaneous demixing occurs rapidly after a triggering event, leading to the quick appearance of liquid droplets. In contrast, delayed demixing features a significant lag phase before droplet formation becomes detectable, often followed by a slow maturation process [23] [25].

These differential kinetic behaviors are not merely observational curiosities; they fundamentally influence the biological fate and pathological potential of the resulting condensates. Recent research on α-synuclein (α-Syn), a protein central to Parkinson's disease pathology, demonstrates that its LLPS and subsequent liquid-to-solid phase transition are strongly dependent on environmental parameters including salt concentration, pH, presence of multivalent cations, and post-translational modifications such as N-terminal acetylation [25]. These factors collectively determine whether α-Syn undergoes spontaneous (instantaneous) or delayed LLPS, with the latter potentially being more relevant to disease-associated conditions [25].

Method-Dependent Kinetic Behaviors

The method used to initiate LLPS profoundly impacts the observed kinetic trajectory, as demonstrated by comparative studies on the low-complexity domain (LCD) of hnRNPA2 [23]:

Table 1: Comparison of LLPS Induction Methods and Their Kinetic Outcomes

| Induction Method | Time to Droplet Appearance | Salt Dependence | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH Jump | Seconds to minutes | Decelerated by 150 mM NaCl | Electrostatic interactions, Ostwald ripening |

| Urea Dilution | ~1 hour to reach maximum | Accelerated by 150 mM NaCl | Residual denaturant, protein relaxation state |

| Solubility Tag Cleavage | Hours (rate-limited by cleavage) | Negligible effect | Enzymatic cleavage efficiency, component partitioning |

The pH jump method, which involves keeping proteins in solution at carefully selected extreme pH values (e.g., pH 11.0) followed by rapid adjustment to physiological pH (e.g., pH 7.5), enables the study of full kinetic trajectories under near-native conditions without dilution effects or enzymatic interference [23]. This approach has been successfully applied to study LLPS of proteins including the LCD of hnRNPA2, TDP-43, NUP98, and the stress protein ERD14 [23].

Figure 1: Kinetic Pathways in Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation. The diagram illustrates the divergent trajectories from protein solution to functional condensates versus pathological aggregates, highlighting the critical branches where experimental conditions determine functional versus pathological outcomes.

Quantitative Analysis of Demixing Kinetics

Kinetic Parameters in LLPS

Quantitative analysis of demixing kinetics requires monitoring multiple parameters that reflect different aspects of the phase separation process. Turbidity measurements at 600 nm provide a gross indicator of light scattering resulting from droplet formation, while dynamic light scattering (DLS) directly measures particle size distribution over time [23]. For hnRNPA2 LCD undergoing LLPS via pH jump, DLS reveals an initial formation of small droplets (~300 nm diameter) that grow to a maximum of ~1500 nm over approximately 1.5 hours, following an exponential time dependence of t¹′³ characteristic of Ostwald ripening [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Kinetic Parameters for hnRNPA2 LCD LLPS Under Different Induction Conditions

| Kinetic Parameter | pH Jump | pH Jump with 150 mM NaCl | Urea Dilution | Urea Dilution with 150 mM NaCl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Maximum Turbidity | Minutes | Slowed progression | ~1 hour | Accelerated |

| Initial Droplet Size (DLS) | ~300 nm | ~300 nm | Not reported | Not reported |

| Maximum Droplet Size (DLS) | ~1500 nm (after 1.5 h) | ~600 nm (after 1.5 h) | ~600 nm (after 1.5 h) | Not reported |

| Growth Mechanism | Ostwald ripening (t¹′³) | Slowed Ostwald ripening | Not characterized | Not characterized |

The differences in kinetic behaviors illustrated in Table 2 highlight the profound influence of induction methods and solution conditions on LLPS trajectories. The reversal of salt effects between pH jump and urea dilution methods suggests that residual denaturant fundamentally alters the molecular interactions driving phase separation [23].

Computational Analysis of Phase Separation

Beyond experimental approaches, computational methods like the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) provide powerful tools for investigating phase separation kinetics. The Shan-Chen multiphase LBM can simulate the evolution of phase separation from initial random distribution through band-like structures to droplet growth across the entire domain [26]. Quantitative analysis of these processes employs the Fourier structure factor, defined as:

[S(k,t) = \frac{1}{N} \left| \sum_r [q(r,t) - \overline{q(t)}] e^{ik \cdot r} \right|]

where (N) is the total number of grid points, (q(r,t) = n1(r,t) - n2(r,t)) represents the density difference between components, and (k) is the wave vector [26]. This structure factor serves as a quantitative measure of spatial heterogeneity development during phase separation, with higher values indicating greater heterogeneity and more advanced phase separation [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Induction of LLPS via pH Jump

The pH jump method represents a generic approach for studying the full kinetic trajectory of LLPS under near-native conditions [23].

Materials

- Protein of interest: Purified using appropriate chromatography methods

- High-pH buffer: pH 11.0 (e.g., glycine-NaOH or carbonate-bicarbonate buffer)

- Native-pH buffer: pH 7.5 (e.g., HEPES or phosphate buffer)

- Salts: NaCl or other salts for modulating ionic strength

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer for turbidity measurements, dynamic light scattering instrument, fluorescence microscope if using fluorescently tagged proteins

Procedure

Protein Preparation:

- Dissolve or dialyze the protein into high-pH buffer (pH 11.0) to maintain it in a soluble state.

- Determine protein concentration using appropriate methods (BCA, Bradford, or UV absorbance).

LLPS Induction:

- Transfer an appropriate volume of protein solution to a cuvette or microscopy chamber.

- Rapidly induce LLPS by adding 1/10 volume of concentrated native-pH buffer (pH 7.5) and mix immediately.

- Final protein concentration should be optimized for the specific protein under investigation.

Kinetic Monitoring:

- Turbidity Measurements: Immediately monitor absorbance at 600 nm at regular time intervals.

- DLS Measurements: Perform size measurements at predetermined time points to track droplet growth.

- Microscopy: If applicable, image droplet formation and morphology over time.

Data Analysis:

- Plot turbidity versus time to identify the time to maximum turbidity.

- Analyze DLS data to determine droplet size distribution and growth kinetics.

- For reversible LLPS, confirm reversibility by returning to high pH and observing dissolution.

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis via Urea Dilution

This protocol serves as a comparative method to highlight the differences in kinetic behaviors induced by alternative approaches [23].

Materials

- Protein stock solution: Prepared in 8 M urea

- Native buffer: pH 7.5, without denaturant

- Other materials: As in Protocol 4.1.1

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein stock solution in 8 M urea at a concentration 100× higher than the desired final concentration.

LLPS Induction:

- Dilute the protein stock 100-fold into native buffer (pH 7.5) to achieve the final desired protein concentration with residual 80 mM urea.

- Mix immediately after dilution.

Kinetic Monitoring:

- Monitor turbidity, droplet size, and morphology as described in Protocol 4.1.2.

- Compare the kinetic profiles with those obtained from the pH jump method.

Protocol 3: Modulation of α-Synuclein LLPS

This specialized protocol addresses the modulation of α-Syn LLPS by environmental factors, relevant to Parkinson's disease research [25].

Materials

- Purified α-Synuclein: Wild-type or mutant forms, with or without N-terminal acetylation

- Buffers: Various pH values as required

- Salts: NaCl, PD-associated multivalent cations

- Equipment: As in Protocol 4.1.1

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare α-Syn in appropriate buffer conditions, considering purification method effects on LLPS propensity.

LLPS Modulation:

- Systematically vary salt concentrations (0-500 mM) to establish charge neutralization effects.

- Test the effects of PD-associated multivalent cations.

- Examine the influence of pH across physiological and pathological ranges.

- Compare LLPS kinetics of N-terminally acetylated versus non-acetylated α-Syn.

Kinetic Analysis:

- Determine critical concentrations and critical times for droplet formation under each condition.

- Monitor liquid-to-solid transition over extended time periods.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LLPS Kinetics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffers | Glycine-NaOH (high pH), HEPES, Phosphate | pH control and adjustment for LLPS induction | Buffer capacity must accommodate pH jump; minimal interference with protein interactions |

| Salts | NaCl, KCl, Multivalent cations | Modulate electrostatic interactions, ionic strength | Concentration-dependent effects may reverse between induction methods |

| Detergents | Triton X-100, Lubrol WX, Brij series | Membrane raft studies; modulate lipid-protein interactions | Different detergents isolate distinct raft subtypes [27] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Complete protease inhibitor cocktail | Prevent protein degradation during extended kinetics experiments | Add fresh just before experiments |

| Crowding Agents | PEG, Ficoll | Mimic cellular crowding effects; modulate LLPS thermodynamics | Molecular weight and concentration affect exclusion volume |

| Fluorescent Tags | GFP, Alexa Fluor conjugates | Enable visualization of droplet formation and dynamics | Potential alteration of native LLPS behavior; minimal tags preferred |

The kinetic profile of liquid-liquid phase separation—whether instantaneous or delayed—is not merely a methodological observation but fundamentally influences the physiological and pathological consequences of biomolecular condensates. The experimental approaches detailed herein, particularly the pH jump method, provide robust platforms for investigating these kinetic trajectories under near-native conditions. The quantitative frameworks and comparative protocols presented enable researchers to dissect the molecular mechanisms governing LLPS initiation and maturation, with significant implications for understanding cellular organization and developing therapeutic interventions for aggregation-related neurodegenerative diseases. As the field advances, integrating these kinetic analyses with thermodynamic profiling will provide a more complete understanding of the phase behavior of biological systems in health and disease.

The fabrication of advanced polymeric membranes with tailored morphologies is a cornerstone of numerous separation processes in chemical, pharmaceutical, and environmental industries. The pathway from a homogeneous polymer solution to a solid, porous membrane structure is governed by the intricate interplay of thermodynamic equilibria and kinetic processes during phase inversion [4]. Understanding and controlling this pathway is essential for producing membranes with precise structural characteristics—such as pore size distribution, porosity, symmetry, and tortuosity—that directly determine their performance in applications like micro-filtration, ultra-filtration, and nano-filtration [28] [29].

This Application Note provides a structured framework for linking initial dope composition to final membrane morphology through a combination of thermodynamic phase diagrams and kinetic analysis. By detailing specific protocols for membrane fabrication via Nonsolvent-Induced Phase Separation (NIPS) and Thermal-Induced Phase Separation (TIPS), quantitative image analysis, and data interpretation, we equip researchers with the tools to systematically design and optimize membrane structures within a broader thesis context of kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of membrane formation.

Theoretical Framework: Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Membrane Formation

Thermodynamic Principles of Phase Separation

Phase separation in both NIPS and TIPS processes is described by the same fundamental thermodynamic principles. A thermodynamically stable polymer solution is brought into an unstable state, where it de-mixes and precipitates to form a solid membrane [4].

- Phase Diagrams: Ternary phase diagrams (polymer-solvent-nonsolvent) for NIPS and binary temperature-composition diagrams for TIPS are critical tools for mapping the thermodynamic boundaries of stability, such as the binodal curve (demarking the boundary between stable and metastable regions) and the spinodal curve (demarking the boundary between metastable and unstable regions) [4].

- Interaction Parameters: The thermodynamic behavior of a polymeric solution is quantified using interaction parameters (e.g., Flory-Huggins parameters). These parameters determine the polymer-solvent compatibility and the location of the binodal curve [4].

Kinetic Considerations in Morphology Development

While thermodynamics defines the equilibrium end states, kinetics control the pathway and rate at which the system evolves, ultimately determining the final membrane microstructure [4].

- NIPS Kinetics: The rate of solvent-nonsolvent exchange is the primary kinetic factor. A rapid exchange often leads to formation of a top skin layer and macrovoids, while a slow exchange promotes the formation of a more cellular, spongy structure [4].

- TIPS Kinetics: The polymer crystallization temperature and the cooling rate of the cast solution are the dominant kinetic factors. A higher cooling rate generally results in a finer porous structure [4].

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters in Membrane Formation

| Parameter | NIPS Process | TIPS Process | Impact on Final Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Thermodynamic Driver | Chemical potential gradient (Solvent-Nonsolvent exchange) | Temperature (Polymer-diluent miscibility) | Determines equilibrium polymer-lean and polymer-rich phases |

| Primary Kinetic Factor | Solvent & nonsolvent mutual diffusion rates | Cooling rate & polymer crystallization kinetics | Controls pore size, symmetry, and formation of macrovoids or spherulites |

| Critical Solution Temperature | Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST) | Upper Critical Solution Temperature (UCST) or LCST | Governs the temperature-concentration region for phase separation |

| Key Additive Effect | Alters coagulation bath chemistry & diffusion paths | Acts as a nucleating agent or modifies crystal growth | Modifies porosity, surface pore density, and overall permeability |

Quantitative Analysis of Membrane Morphology

The transition from qualitative assessment to quantitative morphology analysis is vital for establishing robust structure-property relationships. Automated image analysis of electron microscopy micrographs enables the precise computation of key morphological properties [28] [29].

Protocol: SEM Micrograph Analysis via Texture Recognition

This protocol details the steps for quantifying membrane morphological parameters from Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) cross-section images [28].

Equipment & Reagents:

- Scanning Electron Microscope

- Membrane samples

- Sample preparation materials (e.g., cryogenic fracture apparatus, sputter coater)

- Computer with image analysis software (e.g., QUANTS framework, IFME, or equivalent MATLAB/Python tools) [28] [29]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation & Imaging:

- Prepare a cross-section of the membrane, typically by cryogenic fracturing under liquid nitrogen to preserve native structure.

- Mount and sputter-coat the sample with a conductive material (e.g., gold) to prevent charging.

- Acquire multiple high-resolution SEM micrographs at different magnifications to capture both the overall asymmetric structure and fine pore details.

Image Pre-processing & Membrane Segmentation:

- Load the SEM micrograph into the analysis software.

- If available, calibrate the pixel dimensions using the image's scale bar.

- Apply image processing algorithms to segment the image, distinguishing the porous membrane region from the background and any non-porous support layers. This often involves texture-based segmentation to identify regions of similar structural patterns [28].

Morphological Parameter Quantification:

- Pore Size Distribution: For each identified pore, calculate its equivalent circular diameter or area. Report the distribution (e.g., mean, median, mode, standard deviation).

- Porosity Profile: Divide the membrane cross-section into parallel strips along its thickness. Calculate the porosity (percentage of pore area) within each strip to generate a profile of porosity versus membrane depth [29].

- Degree of Asymmetry (DA): Analyze the porosity profile to calculate a numerical factor. A perfectly symmetric membrane will have a DA close to 0%, while a highly asymmetric membrane (e.g., with a dense skin and open substructure) will have a DA approaching 100% [28].

- Regularity & Tortuosity: Regularity measures the uniformity of pore size and distribution along directions parallel to the membrane surface. Tortuosity quantifies the convoluted path a fluid must take through the pores, often estimated from the geometry of the pore network [28].

Experimental Protocols for Membrane Fabrication and Characterization

Protocol A: Membrane Fabrication via Nonsolvent-Induced Phase Separation (NIPS)

NIPS is a widely used method where a polymer solution is immersed in a coagulation bath containing a nonsolvent, leading to phase separation via solvent exchange [4].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polymer: Polysulfone (PSf), Polyethersulfone (PES), Polyacrylonitrile (PAN).

- Solvent: Polar aprotic solvents (e.g., N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), Dimethylacetamide (DMAc), Dimethylformamide (DMF)).

- Nonsolvent: Water, lower alcohols (e.g., methanol, isopropanol).

- Additives: Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) to modulate viscosity and pore formation.

Procedure:

- Dope Solution Preparation: Dissolve the polymer (e.g., 15-20 wt%) and any additives (e.g., 5 wt% PVP) in the solvent (e.g., NMP) by mechanical stirring at 50-70°C for 12-24 hours until a homogeneous, bubble-free solution is obtained.

- Casting: Allow the dope solution to cool and de-gas. Cast it onto a clean glass plate using a doctor blade set to a defined thickness (e.g., 200 μm).

- Coagulation & Precipitation: Immediately immerse the cast film along with the glass plate into a coagulation bath of deionized water (or another nonsolvent) maintained at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Post-Treatment: After the membrane detaches and phase separation is complete (typically after 10-30 minutes), transfer it to a fresh water bath to leach out residual solvent. Anneal if required.

Protocol B: Membrane Fabrication via Thermal-Induced Phase Separation (TIPS)

TIPS is suitable for polymers that are hard to dissolve at room temperature, using a temperature quench to induce phase separation [4].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polymer: Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF), Polypropylene (PP).

- Diluent: High-bopoint, low-molecular-weight substances (e.g., Dioctyl phthalate (DOP), Dibutyl phthalate (DBP), γ-Butyrolactone).

- Additives: Inorganic salts (e.g., LiCl) to modify crystallization kinetics.

Procedure:

- Dope Solution Preparation: Mix the polymer (e.g., 20-30 wt%) with the diluent in a sealed container. Heat the mixture to a high temperature (e.g., 180-220°C, depending on the system) with vigorous stirring until a homogeneous solution is formed.

- Casting: Cast the hot solution onto a pre-heated plate using a doctor blade.

- Quenching: Rapidly transfer the cast film to a cooling bath or environment set at a specific temperature to induce phase separation via polymer crystallization.

- Diluent Extraction: Soak the solidified membrane in a volatile solvent (e.g., ethanol) to extract the diluent, followed by air-drying.

Workflow and Parameter Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from initial composition to final membrane properties and the key relationships between thermodynamic/kinetic parameters and morphological outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Membrane Fabrication

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers | Polysulfone (PSf), Polyethersulfone (PES), Polyacrylonitrile (PAN), Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) | Forms the structural matrix of the membrane. Molecular weight and concentration dictate solution viscosity and final mechanical strength. | PSf/PES offer good chemical/thermal stability. PVDF is hydrophobic and has good chemical resistance. |

| Solvents (NIPS) | NMP, DMAc, DMF, DMSO | Dissolves the polymer to form a homogeneous casting dope. The solvent power and solubility parameters affect thermodynamics. | High boiling point, polar aprotic. Consider environmental and health impacts; "green" solvent alternatives are sought [4]. |

| Diluents (TIPS) | Dioctyl phthalate (DOP), Dibutyl phthalate (DBP), Glycerol | Acts as a high-boiling-point solvent that is miscible with the polymer at high T but immiscible at low T. | Must be non-volatile at casting temperature and easily extracted post-solidification. |

| Nonsolvents | Water, Methanol, Ethanol | In NIPS, induces phase separation by diffusing into the cast film while solvent diffuses out. | The solvent-nonsolvent affinity (e.g., miscibility) is a key kinetic parameter. |

| Additives | PVP, PEG, LiCl, Glycerol | Modifies solution viscosity, acts as a pore-former, or influences kinetics by altering solvent-nonsolvent exchange rates. | Typically low molecular weight; can be blended with polymer or added to the coagulation bath. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Systematic data analysis is crucial for correlating synthesis conditions with morphological properties [28] [29]. The following table provides a template for summarizing key quantitative data obtained from image analysis.

Table 3: Template for Quantitative Morphology Data from Image Analysis

| Sample ID & Synthesis Condition | Mean Pore Size (nm) | Porosity (%) | Degree of Asymmetry (DA) | Tortuosity ( - ) | Key Morphological Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSf-15%-Water-25C | 25 ± 5 | 65 ± 3 | 85% | 2.1 | Thin selective skin, porous finger-like substructure |

| PSf-15%-Water-5C | 18 ± 4 | 60 ± 4 | 78% | 2.3 | Finer pores, shorter macrovoids |

| PSf-18%-Water-25C | 15 ± 3 | 55 ± 3 | 70% | 2.5 | Denser matrix, spongy layer |

| PSf-15%-30%Gly-25C | 45 ± 8 | 75 ± 2 | 60% | 1.8 | More open, cellular structure |

Advanced Techniques and Future Perspectives

Advanced Characterization and Modeling

Beyond basic morphology quantification, advanced techniques and computational models are increasingly important for a deeper understanding.

- Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS): Used to characterize the thermodynamics and kinetics of pH-triggered membrane protein insertion by measuring diffusion times of fluorescently labeled molecules, providing insights into free energy of transfer and interfacial interactions [13].

- Digital Holographic Microscopy (DHM): A label-free technique for quantifying 3D morphology and membrane dynamics of cells like red blood cells, providing parameters such as projected surface area, sphericity coefficient, and cell membrane fluctuations [30].

- Computational Simulations: Mesoscopic (e.g., Phase Field model) and molecular scale simulations (e.g., Dissipative Particle Dynamics, Molecular Dynamics) are powerful tools for modeling the membrane formation process and predicting morphology from first principles [4].

Combined NIPS-TIPS Processes and Green Solvents

Emerging trends include hybrid phase separation processes and a shift towards more sustainable solvents [4].