Kinetic Analysis of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases: Methods, Applications, and Advances in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the kinetic analysis of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs), essential enzymes in protein synthesis and prime targets for therapeutic development.

Kinetic Analysis of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases: Methods, Applications, and Advances in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the kinetic analysis of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs), essential enzymes in protein synthesis and prime targets for therapeutic development. It covers foundational principles, including the two-step aminoacylation reaction and the distinct kinetic mechanisms of Class I and Class II AARSs. The scope extends to detailed methodologies for steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic assays, troubleshooting common experimental challenges, and validating data through comparative analysis. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes classic and contemporary techniques to support fundamental research, antibiotic discovery, and the engineering of synthetic biological systems.

Foundational Principles of AARS Catalysis and Kinetic Mechanisms

Aminoacylation is the vital two-step enzymatic process through which an amino acid is covalently linked to its corresponding transfer RNA (tRNA), creating a charged tRNA (aminoacyl-tRNA) that serves as the substrate for protein synthesis on the ribosome [1]. This reaction, catalyzed by the family of enzymes known as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs), is often termed "tRNA charging" and represents a critical interpretive step in the translation of genetic information from nucleic acid sequence to protein sequence [2] [3]. The two-step mechanism ensures both the fidelity of amino acid selection and the thermodynamic driving force necessary for peptide bond formation [1]. This application note details the kinetic analysis methodologies essential for investigating these fundamental reactions, providing researchers with current protocols for characterizing AARS function in basic research and drug discovery contexts.

Core Reaction Mechanism

The aminoacylation reaction proceeds through two discrete chemical steps, both catalyzed by the same AARS enzyme [4].

Step 1: Amino Acid Activation

The first step involves activation of the amino acid carboxyl group via adenylation. The AARS enzyme catalyzes the condensation of an amino acid with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to form an aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate (aa-AMP), releasing inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) [1] [5]. This reaction occurs while the intermediate remains bound to the enzyme active site (E•AA~AMP).

Net Reaction: AA + ATP → E•AA~AMP + PPi

Step 2: Aminoacyl Transfer

The second step involves transfer of the activated amino acid to the 3' end of the cognate tRNA molecule. The 2'- or 3'-OH group of the terminal adenosine ribose (A76) of tRNA performs a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the aminoacyl-adenylate, forming aminoacyl-tRNA and releasing adenosine monophosphate (AMP) [1] [4].

Net Reaction: E•AA~AMP + tRNA^AA → AA-tRNA^AA + AMP

The overall reaction conserves energy through the formation of the high-energy aminoacyl-tRNA ester bond, which subsequently drives peptide bond formation on the ribosome [1].

Enzyme Classes and Structural Considerations

AARS enzymes are divided into two structurally and mechanistically distinct classes (Class I and Class II) based on catalytic domain architecture [1] [6].

- Class I AARS typically function as monomers, contain characteristic HIGH and KMSKS signature motifs, bind the tRNA acceptor stem from the minor groove, and generally aminoacylate the 2'-OH of A76 [1] [5].

- Class II AARS typically function as dimers or tetramers, contain three divergent signature motifs, bind the tRNA acceptor stem from the major groove, and exclusively aminoacylate the 3'-OH of A76 [1] [5].

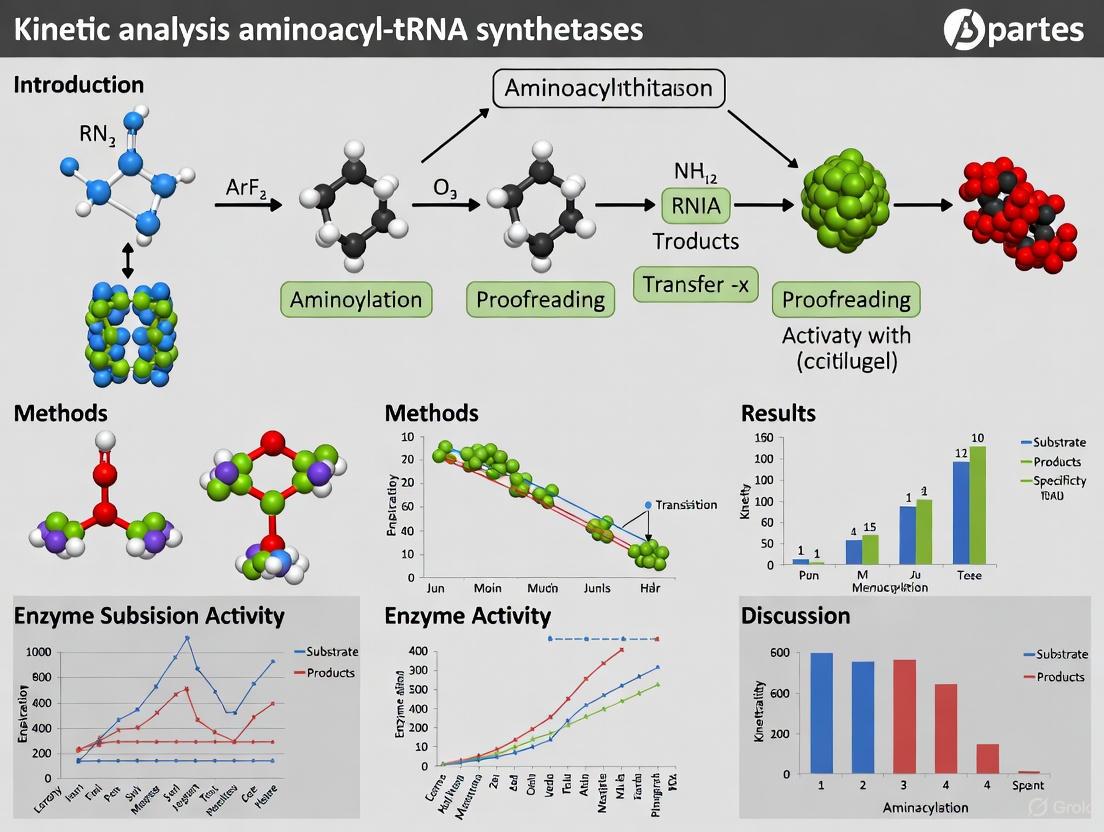

Figure 1: The Two-Step Aminoacylation Reaction and AARS Enzyme Classification. The pathway illustrates the sequential activation and transfer steps catalyzed by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, which are divided into two structurally distinct classes.

Quantitative Kinetic Analysis

Kinetic analysis of AARS enzymes reveals distinct mechanistic behaviors between the two classes and provides essential parameters for characterizing enzyme function and inhibitor interactions.

Steady-State Kinetic Parameters

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for Representative AARS Enzymes

| Enzyme | Class | kcat (s⁻¹) | Km (AA) (μM) | Km (ATP) (μM) | Km (tRNA) (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CysRS | I | 2.4 | 21.2 | 87.5 | 1.6 | [6] |

| ValRS | I | 2.8 | 48.0 | 110.0 | 0.5 | [6] |

| AlaRS | II | 3.3 | 12.0 | 120.0 | 24.0 | [6] |

| ProRS | II | 1.9 | 52.0 | 60.0 | 2.8 | [6] |

Transient Kinetic Parameters

Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis provides insight into individual steps of the reaction mechanism, revealing significant class-dependent differences [6].

Table 2: Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for AARS Enzymes

| Enzyme | Class | kchem (s⁻¹) | ktrans (s⁻¹) | Burst Kinetics | Rate-Limiting Step | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CysRS | I | 13.4 | 13.4 | Yes | Product release | [6] |

| ValRS | I | 9.5 | 9.5 | Yes | Product release | [6] |

| AlaRS | II | 16.2 | 16.2 | No | Amino acid activation | [6] |

| ProRS | II | 7.6 | 7.6 | No | Amino acid activation | [6] |

Key Kinetic Observations:

- Class I AARS typically exhibit burst kinetics, where the initial rate of aminoacyl-tRNA formation exceeds the steady-state rate, indicating that product release is rate-limiting [6] [7].

- Class II AARS generally do not exhibit burst kinetics, with the chemical step of amino acid activation typically being rate-limiting [6] [7].

- The single turnover rate (kchem) representing the composite rate of the two chemical steps is significantly faster than the steady-state kcat for both classes, indicating that physical steps (substrate binding or product release) limit overall turnover [6].

Figure 2: Kinetic Mechanism Differences Between AARS Classes. Class I and Class II AARS enzymes demonstrate distinct kinetic behaviors, particularly in their pre-steady-state kinetics and rate-limiting steps.

Experimental Protocols

ATP/PPi Exchange Assay for Activation Step Kinetics

The ATP/PPi exchange assay specifically measures the first step of aminoacylation (amino acid activation) by monitoring the reversible incorporation of labeled pyrophosphate into ATP [2] [3].

Principle: At equilibrium, the AARS-catalyzed reaction rapidly interconverts ATP+AA and AMP-AA+PPi. The incorporation of radiolabel from [³²P]PPi into ATP provides a direct measure of the amino acid activation rate [3].

Modified Protocol Using γ-[³²P]ATP ( [2] [3]):

Reaction Mixture:

- 20-50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5)

- 10 mM MgCl₂

- 25 mM KCl

- 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)

- 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA)

- 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate (PPi)

- 2 mM ATP

- 0.1-1.0 μM AARS enzyme

- Variable amino acid concentration (for Km determination)

- γ-[³²P]ATP (tracer quantity)

Procedure:

- Incubate reaction mixture at 25°C or 37°C

- Remove aliquots at specified time intervals (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120, 300 seconds)

- Quench reactions with 2% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 40 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0)

- Separate [³²P]ATP from [³²P]PPi by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on polyethyleneimine-cellulose plates

- Develop TLC plates in 0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) with 0.35 M urea

- Visualize and quantify using phosphor storage screens and Typhoon biomolecular imager

Data Analysis:

- Calculate initial velocities from time course of [³²P]ATP formation

- Determine Km and kcat values by fitting velocity versus substrate concentration to Michaelis-Menten equation

Applications: This assay is particularly valuable for initial kinetic characterization, large-scale inhibitor screening, and determining amino acid selectivity, especially for AARS that activate amino acids in the absence of tRNA [2] [3].

Aminoacylation Assay for Complete Reaction Kinetics

The aminoacylation assay measures the overall two-step reaction by monitoring the formation of aminoacyl-tRNA [4].

Protocol Using Radiolabeled Amino Acids:

Reaction Mixture:

- 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5)

- 20 mM MgCl₂

- 5 mM DTT

- 2 mM ATP

- 0.1-0.5 mg/mL BSA

- ¹⁴C- or ³H-labeled amino acid (cognate substrate)

- Purified tRNA (produced by in vitro transcription or natural purification)

- AARS enzyme (concentration dependent on activity)

Procedure:

- Initiate reaction by adding AARS enzyme

- Incubate at 37°C

- Remove aliquots at timed intervals

- Quench by spotting on acidified filter papers (for trichloroacetic acid precipitation)

- Wash filters extensively to remove unincorporated radiolabeled amino acid

- Quantify radioactivity by scintillation counting

Data Analysis:

- Plot aminoacyl-tRNA formed versus time

- Determine initial velocity from linear portion of progress curve

- Calculate steady-state kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) by varying substrate concentrations

Rapid Kinetic Techniques for Mechanistic Studies

Pre-steady-state kinetic methods provide resolution of individual steps in the reaction mechanism [4] [6].

Rapid Chemical Quench Flow:

- Application: Measures chemical steps of the reaction on millisecond to second timescales

- Method: Rapidly mix enzyme and substrates, then quench with acid or denaturant after precise time intervals

- Information Gained: Direct measurement of aminoacyl-adenylate and aminoacyl-tRNA formation rates; identification of transient intermediates

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence:

- Application: Monitors conformational changes associated with substrate binding and catalysis

- Method: Rapidly mix enzyme and substrates while monitoring intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence changes

- Information Gained: Rates of substrate-induced conformational changes; binding constants; sequence of substrate addition

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for AARS Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Protocol Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiolabeled Substrates | γ-[³²P]ATP, [³²P]PPi, ¹⁴C/³H-amino acids | Tracing reaction progress; quantifying rates of activation and transfer | [2] [3] [4] |

| AARS Enzymes | Purified recombinant synthetases (e.g., CysRS, ValRS, AlaRS) | Catalyzing the aminoacylation reaction; target for kinetic characterization | [4] [6] |

| tRNA Substrates | In vitro transcribed tRNA; purified native tRNA | Amino acid acceptor in second step; contains identity elements for recognition | [4] |

| Chromatography Materials | Polyethyleneimine-cellulose TLC plates | Separation of nucleotide species (ATP vs. PPi) in exchange assays | [2] [3] |

| Detection Systems | Phosphor storage screens, Typhoon biomolecular imager | Visualization and quantification of radiolabeled compounds | [2] [3] |

Emerging Methodologies and Applications

Novel Sequencing-Based Approaches

Recent advances in tRNA sequencing technologies enable comprehensive analysis of tRNA aminoacylation states in complex biological samples [8] [9].

Charge tRNA-Seq (tRNA-Seq) combines periodate oxidation (Whitfeld reaction) with high-throughput sequencing to quantify aminoacylation levels across the entire tRNA pool [9]. Deacylated tRNAs undergo periodate oxidation of the 3'-terminal ribose, followed by β-elimination that truncates the molecule by one nucleotide, while aminoacylated tRNAs are protected. The differential sequencing signals allow precise quantification of charging levels [9].

Nanopore Sequencing of Intact Aminoacylated tRNAs represents a cutting-edge methodology that directly sequences native tRNA molecules without prior manipulation [8]. The "aa-tRNA-seq" method uses chemical ligation to sandwich the amino acid between the tRNA body and an adaptor oligonucleotide, stabilizing the labile ester linkage. Machine learning models then identify amino acid identities based on unique signal distortions generated as the amino acid-modified RNA passes through the nanopore [8].

Applications in Drug Discovery

AARS enzymes are established targets for antibiotic development, with the ATP/PPi exchange assay serving as a primary screen for identifying AARS inhibitors [2] [3]. The kinetic parameters and mechanistic insights obtained through these protocols facilitate structure-based drug design and optimization of inhibitor specificity. The distinct active site architectures of Class I and Class II AARS enable the development of class-specific inhibitors with broad-spectrum activity against bacterial pathogens [5].

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs) are essential and universally distributed enzymes that catalyze the esterification of transfer RNAs (tRNAs) with their cognate amino acids, thereby enabling the translation of genetic information into functional proteins [10]. These enzymes implement the genetic code by pairing each amino acid with the correct tRNA molecule bearing the corresponding anticodon, forming aminoacyl-tRNAs (aa-tRNAs) that serve as substrates for protein synthesis on the ribosome [10] [11]. The reaction catalyzed by AARSs occurs in two distinct steps: first, the activation of the amino acid with ATP to form an aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate (AA-AMP), and second, the transfer of the aminoacyl moiety to the 3' end of the appropriate tRNA [12] [10]. The accuracy of this process is critical for maintaining translational fidelity, and AARSs have evolved sophisticated substrate discrimination and proofreading mechanisms to ensure the correct pairing of amino acids with their corresponding tRNAs. Beyond their canonical role in translation, AARSs have also been implicated in numerous non-canonical cellular processes, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention in infectious diseases, cancer, and other pathological conditions [13] [14].

Classification Basis: Structural and Functional Dichotomy

The 20 canonical aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are divided into two structurally distinct classes (Class I and Class II) that are evolutionarily unrelated and exhibit fundamental differences in their catalytic architectures, signature motifs, and mechanisms of action [15] [16] [10]. This classification system, established based on mutually exclusive sets of sequence motifs and later confirmed by X-ray crystallography, reveals an ancient evolutionary divergence within the AARS family [15] [17]. Table 1 summarizes the key differentiating characteristics between these two enzyme classes.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Class I and Class II Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases

| Characteristic | Class I AARSs | Class II AARSs |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Domain Architecture | Rossmann fold (parallel β-sheet) [15] [10] | Anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by α-helices [16] [10] |

| Characteristic Signature Motifs | HIGH and KMSKS [10] | Motifs 1, 2, and 3 (less conserved) [16] [10] |

| Typical Oligomeric State | Mostly monomeric [15] [16] | Mostly dimeric or multimeric [16] [10] |

| Site of Aminoacylation on tRNA A76 | 2′-OH group (except TyrRS and TrpRS) [12] [10] | 3′-OH group (except PheRS) [12] [10] |

| tRNA Acceptor Stem Interaction | Minor groove (except TyrRS and TrpRS) [10] | Major groove [10] |

| ATP Binding Configuration | Extended conformation [10] | Bent conformation (γ-phosphate folds over adenine ring) [10] |

| Rate-Limiting Step in Aminoacylation | Aminoacyl-tRNA release (except IleRS and some GluRS) [10] | Amino acid activation [10] |

The evolutionary conservation of an ATP binding site underscores the functional unity within each class despite their structural differences [17]. The complementary recognition of the major and minor grooves of the tRNA acceptor stem by Class II and Class I enzymes, respectively, suggests an evolutionary model where both classes arose from a single ancestral gene, subsequently diverging to form the two distinct structural lineages we observe today [10].

Detailed Structural Analysis of AARS Classes

Class I AARSs: Rossmann Fold and Domain Organization

Class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are characterized by a catalytic domain featuring a classic Rossmann fold (RF), a nucleotide-binding motif composed of a five-stranded parallel β-sheet connected by α-helices that is also found in dehydrogenases and kinases [15] [10] [17]. This catalytic domain is typically located at or near the amino terminus of the protein and contains two highly conserved signature sequences: the HIGH motif (His-Ile-Gly-His) and the KMSKS motif (Lys-Met-Ser-Lys-Ser), which are separated by a connecting domain termed connective peptide 1 (CP1) [10]. The HIGH motif participates in ATP binding and pyrophosphate hydrolysis, while the KMSKS loop contributes to the stabilization of the transition state during aminoacyl adenylate formation.

Class I enzymes can be further subdivided into three subclasses (a, b, and c) based on phylogenetic analysis and structural characteristics [10]. Subclass Ia includes enzymes for the aliphatic amino acids (Leu, Ile, Val) and sulfur-containing amino acids (Met, Cys); Subclass Ib comprises those for the charged amino acids (Glu, Gln) and Arg; and Subclass Ic encompasses synthetases for the aromatic amino acids (Tyr, Trp) and Val [15] [10]. A notable structural feature of many Class I AARSs is the presence of an editing domain within the CP1 insertion, which provides a proofreading function to hydrolyze misactivated amino acids or misacylated tRNAs [10].

Class II AARSs: Antiparallel β-Sheet Architecture

Class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases possess a catalytic domain organized around a six- to seven-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by α-helices, a unique structural fold not found in other enzyme families [16] [10] [17]. This class is characterized by three conserved motifs (1, 2, and 3) that are less conserved than their Class I counterparts but play crucial roles in substrate binding and enzyme structure [16] [17]. Motif 1 forms a hinge that helps dimerize Class II enzymes, while Motif 2 contains residues that contact the adenosine moiety of ATP and the tRNA acceptor stem.

Class II synthetases are divided into three subgroups (a, b, and c) with distinct functional correlations [10]. Subclass IIa includes Ser, Thr, Pro, and HisRSs; Subclass IIb encompasses Asn, Asp, and LysRSs; and Subclass IIc contains Ala, Gly, Phe, and SepRSs [10]. Unlike Class I enzymes, Class II AARSs typically function as dimers or higher-order oligomers, with their active sites formed at the subunit interfaces in some cases. The editing activities in Class II enzymes can be located in various domains rather than a conserved insertion like the CP1 domain of Class I enzymes [10].

Kinetic Mechanisms and Analysis Methodologies

Reaction Kinetics and Catalytic Mechanisms

The aminoacylation reaction follows a bi-bi sequential mechanism in which both ATP and the amino acid bind to the enzyme before products are released. For most AARSs, the reaction proceeds through a ping-pong mechanism involving the aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate [12]. However, notable exceptions include GlnRS, GluRS, ArgRS, and Class I LysRS, which require the presence of tRNA for productive amino acid activation [12] [10].

The kinetic mechanisms of Class I and Class II AARSs exhibit fundamental differences that extend beyond their structural variations. For Class I enzymes, the rate-limiting step is typically the release of the aminoacyl-tRNA product, whereas for Class II enzymes, the amino acid activation rate (first step) is generally rate-limiting [10]. This distinction has important implications for the design and interpretation of kinetic experiments targeting these enzyme classes.

Experimental Approaches for Kinetic Analysis

Kinetic analysis of AARS function employs both steady-state and pre-steady-state approaches, each providing complementary information about the catalytic mechanism [12] [4].

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Kinetic Analysis of AARSs

| Method Type | Specific Assay | Measured Parameters | Applications and Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State Kinetics | Pyrophosphate exchange assay [12] [4] | kcat, Km for amino acid activation | Measures reverse reaction of adenylate formation; useful for specificity studies |

| Aminoacylation assay [12] [4] | kcat, Km for overall aminoacylation | Direct measurement of aa-tRNA formation; assesses catalytic efficiency | |

| Pre-Steady-State Kinetics | Rapid chemical quench [12] [4] | Elementary rate constants for single-turnover reactions | Direct measurement of chemical steps; identification of rate-limiting steps |

| Stopped-flow fluorescence [12] [4] | Conformational changes correlated with reaction steps | Monitoring substrate binding, isomerization, and product release in real-time |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for comprehensive kinetic analysis of AARSs, integrating both steady-state and pre-steady-state approaches:

Preparation of tRNA Substrates for Kinetic Studies

The preparation of high-quality tRNA substrates is crucial for reliable kinetic analysis of AARS function. Three primary methods are employed for tRNA preparation, each with characteristic advantages and limitations [12] [4]:

Purification from Overexpressing Cells: This method involves inserting the tRNA gene into a plasmid with a highly transcribed promoter, followed by purification from cell extracts using phenol extraction and chromatographic techniques. The principal advantage is that the tRNA contains natural post-transcriptional modifications that may be essential for efficient recognition by some AARSs. The main disadvantage is the potential heterogeneity in modification patterns and difficulty in separating isoaccepting tRNAs [12].

In Vitro Transcription using T7 RNA Polymerase: This widely used method allows preparation of large quantities of homogeneous tRNA transcripts of virtually any sequence. The limitation is that these transcripts lack natural modifications, which may affect kinetics for some systems. Transcription yields can be optimized by fine-tuning NTP concentrations, temperature, and enzyme concentration [12].

Chemical Synthesis and Ligation: This approach involves chemical synthesis of tRNA half molecules followed by ligation using T4 RNA ligase. While offering complete control over sequence and incorporation of modified nucleotides, this method is technically demanding and low-yielding, making it suitable for specialized applications rather than routine kinetic studies [12].

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AARS Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| AARS Expression Systems | Recombinant AARS from E. coli, yeast, or baculovirus | Source of purified enzyme for kinetic studies |

| tRNA Preparation Methods | In vivo overexpression, T7 in vitro transcription | Substrate preparation with or without modifications |

| Radiolabeled Substrates | [α-32P]ATP, [32P]-PPi, 3H- or 14C-labeled amino acids | Detection of reaction intermediates and products |

| Kinetic Assay Reagents | Pyrophosphate exchange buffer components | Measurement of amino acid activation rates |

| Specialized Equipment | Rapid quench instruments, stopped-flow spectrofluorometers | Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis |

| Class I AARS Inhibitors | AN2690 (benzoxaborole) for LeuRS [13] | Mechanistic probes and therapeutic leads |

| Class II AARS Inhibitors | Halofuginone for ProRS [13] | Mechanistic probes and therapeutic leads |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The essential role of AARSs in protein synthesis and their structural differences between pathogens and humans make them attractive targets for antibiotic and therapeutic development [13] [18] [14]. Several class-specific inhibitors have been developed that exploit the unique structural and mechanistic features of each AARS class:

Class I-Targeted Inhibitors: Benzoxaboroles, such as AN2690, target leucyl-tRNA synthetase (LeuRS) through an oxaborole tRNA-trapping (OBORT) mechanism, forming a stable tRNALeu-benzoxaborole adduct where the boron atom interacts with the 2'- and 3'-oxygen atoms of the terminal tRNA adenosine [13]. This mechanism capitalizes on the 2'-OH regioselectivity of Class I enzymes. GSK656 (compound 8) is a 3-aminomethylbenzoxaborole derivative that has progressed to phase 2 clinical trials for tuberculosis, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of Class I AARS inhibitors [13].

Class II-Targeted Inhibitors: Halofuginone and its derivatives inhibit prolyl-tRNA synthetase (ProRS) and are under investigation for treatment of cancer, fibrosis, and inflammatory diseases [13]. Cladosporin, a natural product inhibitor, targets lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LyRS) in Plasmodium falciparum and exhibits potent antimalarial activity by exploiting structural differences between the parasitic and human enzymes [13].

The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanisms of representative Class I and Class II AARS inhibitors:

In trypanosomatid diseases (Leishmaniasis, Human African Trypanosomiasis, and Chagas disease), AARSs have emerged as promising drug targets due to unique structural features that distinguish parasite enzymes from their human counterparts [14]. These include unique insertion sequences, additional domains, and divergent amino acid residues in substrate binding sites. Gene knockout and knockdown studies have validated the essentiality of several AARS genes (LysRS, TyrRS, LeuRS, MetRS, ThrRS) for parasite survival, further supporting their potential as therapeutic targets [14].

The structural and functional division of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases into Class I and Class II enzymes represents a fundamental paradigm in molecular biology with far-reaching implications for basic research and therapeutic development. The distinct catalytic folds, signature motifs, oligomeric states, and kinetic mechanisms of these two enzyme classes underscore their independent evolutionary origins while highlighting their convergent functional roles in implementing the genetic code. Comprehensive kinetic analysis using both steady-state and pre-steady-state approaches provides powerful insights into the catalytic mechanisms and specificity determinants of both enzyme classes. The expanding repertoire of class-specific AARS inhibitors in clinical development validates these enzymes as promising therapeutic targets and underscores the importance of understanding their distinct structural and kinetic properties for future drug discovery efforts.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) are essential enzymes responsible for charging tRNAs with their cognate amino acids, thereby enabling the accurate translation of genetic information into proteins [10] [19]. The kinetic parameters that govern these enzymatic reactions—kcat, Km, kchem, and ktran—provide critical insights into the catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, and rate-limiting steps of aminoacylation. Quantitative analysis of these parameters is fundamental for basic enzymology studies, investigating translational fidelity, and developing therapeutics that target protein synthesis [12] [3]. This application note details the core kinetic parameters for aaRSs, outlines established protocols for their determination, and presents a framework for data interpretation within the broader context of aaRS research.

Defining the Core Kinetic Parameters

The aminoacylation reaction occurs in two discrete steps: 1) amino acid activation and 2) aminoacyl transfer [10] [12]. Distinct kinetic parameters describe the efficiency of each step and the overall reaction.

Table 1: Definition of Key Kinetic Parameters in Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Research

| Parameter | Definition | Reaction Phase | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| kcat | Turnover number: the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time. | Overall reaction (steady-state) | A measure of the enzyme's maximal catalytic efficiency when saturated with substrate. |

| Km | Michaelis constant: the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax. | Overall reaction (steady-state) | An inverse measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate; a lower Km indicates higher affinity. |

| kchem | The rate constant for the chemical step of adenylate formation (activation). | Pre-steady state (first step) | Represents the intrinsic speed of the bond-making/breaking event that creates the aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate [20]. |

| ktran | The rate constant for the transfer of the aminoacyl moiety from the adenylate to the tRNA. | Pre-steady state (second step) | Represents the intrinsic speed of the transesterification reaction that produces aminoacyl-tRNA [7]. |

A critical distinction exists between steady-state (e.g., kcat, Km) and pre-steady-state (e.g., kchem, ktran) parameters. Steady-state kinetics describes the overall catalytic cycle under conditions where the enzyme is not saturated, typically using enzyme concentrations much lower than substrate. In contrast, pre-steady-state kinetics examines the initial transient phase of the reaction, often with enzyme concentration exceeding substrate, to isolate and measure the rates of individual chemical steps [12].

Furthermore, aaRSs are historically divided into two classes (I and II) based on structural differences, which also manifest as distinct kinetic mechanisms. A key mechanistic signature is that class I aaRSs are typically rate-limited by aminoacyl-tRNA product release, whereas class II aaRSs are typically rate-limited by a step prior to transfer, often the amino acid activation [21]. This difference often results in "burst kinetics" observed in class I enzymes, where an initial rapid burst of product formation is followed by a slower steady-state rate [7] [21].

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Analysis

ATP/PPi Exchange Assay (Amino Acid Activation)

The ATP/PPi exchange assay is a steady-state method that specifically monitors the first step of the reaction: amino acid activation [12] [3].

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Mixture: Prepare a master mix containing:

- 20-50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5

- 10-20 mM MgCl2

- 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)

- 1-5 mM ATP

- Variable concentrations of cognate amino acid

- 0.1-2 mM sodium pyrophosphate (PPi) spiked with a radioactive tracer (historically [32P]PPi; see Scientist's Toolkit for a modern alternative)

- Purified aaRS enzyme (quantity depends on specific activity) [3].

- Incubation: Initiate the reaction by adding enzyme. Incubate at 37°C.

- Quenching: At designated time points (e.g., 0, 2, 5, 10, 20 minutes), remove aliquots and quench the reaction with a solution containing 0.4 M sodium acetate and 0.1% SDS [3].

- Separation & Detection:

- Spot quenched samples onto a polyethyleneimine (PEI) cellulose thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate.

- Separate [32P]ATP from [32P]PPi using a mobile phase (e.g., 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0).

- Visualize and quantify the radioactive spots using a phosphorimager [3].

- Data Analysis: The rate of [32P]ATP formation is proportional to the rate of the activation reaction. Plot the initial velocity (v0) against amino acid concentration and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to extract kcat and Km for the activation step.

The aminoacylation assay measures the cumulative two-step reaction, yielding aminoacyl-tRNA [12].

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Mixture: Combine:

- 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5

- 20 mM MgCl2

- 150 mM KCl

- 2-5 mM ATP

- Variable concentrations of cognate tRNA

- A fixed, saturating concentration of cognate amino acid (often radiolabeled with 14C or 3H)

- Purified aaRS enzyme.

- Incubation & Quenching: Start the reaction with enzyme. At time points, quench aliquots on filter pads pre-soaked in 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA).

- Detection: Wash the filters to remove unincorporated radiolabeled amino acid. Measure the radioactivity retained on the filter (corresponding to aminoacyl-tRNA) using a scintillation counter.

- Data Analysis: Plot the initial velocity of aminoacyl-tRNA formation against tRNA concentration. Fitting to the Michaelis-Menten equation provides the overall kcat and Km for the tRNA substrate.

Pre-Steady State Rapid Kinetics (kchemand ktran)

Rapid kinetic techniques, such as stopped-flow fluorescence or rapid chemical quench, are required to resolve the individual chemical steps and determine kchem and ktran [12].

Protocol Overview (Rapid Chemical Quench):

- Loading: Solutions containing enzyme, ATP, and amino acid are rapidly mixed with a solution containing tRNA in a specialized quench-flow instrument.

- Reaction & Quench: The reaction is allowed to proceed for very short, defined time periods (milliseconds to seconds) before being forcibly quenched with acid or base.

- Analysis: The quenched samples are analyzed to quantify the amount of product (e.g., aminoacyl-AMP or aminoacyl-tRNA) formed at each time point. This can be done via TLC (similar to the ATP/PPi assay) or by other separation methods [20].

- Data Fitting: The time-dependent formation of the intermediate (AA-AMP) or final product (AA-tRNA) is fitted to exponential equations. The observed rate constant for AA-AMP formation provides kchem, while the rate for AA-tRNA formation provides ktran [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for aaRS Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| γ-[32P]ATP | Radiolabeled substrate for the modified ATP/PPi exchange assay. | A readily available alternative to discontinued [32P]PPi; allows monitoring of ATP conversion [3]. |

| Purified tRNA | Substrate for aminoacylation and tRNA-dependent activation. | Can be purified from native sources (contains modifications) or via in vitro transcription (homogeneous, may lack modifications) [12]. |

| Inorganic Pyrophosphatase | Enzyme added to ATP/PPi exchange reactions. | Hydrolyzes PPi product, shifting equilibrium forward and driving the reaction towards ATP formation, enhancing assay sensitivity [3]. |

| PEI-Cellulose TLC Plates | Stationary phase for separating nucleotide species (ATP, ADP, AMP, PPi). | Essential for radiometric assays like ATP/PPi exchange and analysis of quenched rapid-kinetic samples [3]. |

| Rapid Chemical Quench Instrument | Apparatus for mixing and quenching reactions on millisecond timescales. | Required for pre-steady state kinetic measurements to determine kchem and ktran [12]. |

Data Interpretation and Application

Interpreting kinetic data for aaRSs requires consideration of their class-specific mechanisms. The observation of a burst phase in a pre-steady state experiment is a hallmark of class I aaRS kinetics, indicating that a step after chemistry (typically product release) is rate-limiting for the overall cycle [7] [21]. The amplitude of the burst provides an estimate of the concentration of active enzyme.

The parameters kcat/Km (the specificity constant) for amino acid and tRNA substrates are crucial for understanding how synthetases achieve high fidelity. This ratio reflects the enzyme's efficiency in discriminating between cognate and non-cognate substrates. Single-turnover experiments measuring kchem and ktran allow researchers to pinpoint which elementary step is most affected by mutations in the enzyme or tRNA, providing deep mechanistic insights into substrate recognition and specificity [22].

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs) are essential enzymes that catalyze the covalent attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs, ensuring the accurate translation of genetic information into proteins. These enzymes are phylogenetically divided into two distinct classes (Class I and Class II) based on structural features and catalytic mechanisms. Beyond these classical distinctions, transient burst kinetics has emerged as a crucial experimental signature that mechanistically differentiates the two classes [21]. This pre-steady state kinetic phenomenon provides profound insights into the rate-limiting steps of the aminoacylation reaction, with significant downstream implications for the efficiency of protein synthesis and the potential for therapeutic intervention [21] [7]. For researchers investigating AARS function, the presence or absence of burst kinetics serves as a critical diagnostic tool for elucidating catalytic mechanisms and designing targeted inhibitors.

Fundamental Principles of Burst Kinetics in AARS Reactions

Defining Burst Kinetics

Burst kinetics describes a characteristic pre-steady state phenomenon wherein the initial rapid formation of a product occurs at a rate exceeding the enzyme's steady-state turnover rate (kcat). This burst phase is followed by a slower, linear phase of product generation limited by the enzyme's overall catalytic cycle [7]. In practical terms, when enzyme concentration significantly exceeds substrate concentration under single-turnover conditions, the burst amplitude directly correlates with the concentration of active enzyme sites, while the subsequent linear phase reflects the rate-limiting step that controls multiple turnovers [21].

Class I vs. Class II AARS: A Kinetic Dichotomy

The division between Class I and Class II AARS enzymes based on burst kinetics reflects fundamental mechanistic differences:

- Class I AARS (including CysRS, ValRS, MetRS, and others) typically display pronounced burst kinetics in aminoacyl-tRNA formation [21] [7]. This indicates that the chemical step of aminoacyl transfer is faster than the subsequent product release.

- Class II AARS (including AlaRS, ProRS, HisRS, and others) generally exhibit no burst kinetics, instead progressing directly to steady-state product formation [21] [7]. This suggests that a step prior to aminoacyl transfer, often associated with amino acid activation, limits their overall catalytic rate.

Table 1: Classification of Representative AARS Enzymes and Their Kinetic Properties

| Class | AARS Families | Burst Kinetics | Rate-Limiting Step | Site of Aminoacylation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | CysRS, ValRS, MetRS, IleRS, TyrRS | Present | Aminoacyl-tRNA release | 2'-OH of terminal ribose |

| Class II | AlaRS, ProRS, HisRS, SerRS, ThrRS | Absent | Step prior to transfer (activation) | 3'-OH of terminal ribose |

Mechanistic Basis for Burst Kinetics

Kinetic Mechanism of Class I AARS Enzymes

For Class I AARS enzymes, the observed burst kinetics follows a characteristic sequence:

- Rapid substrate binding and formation of the enzyme-aminoacyl adenylate complex

- Fast aminoacyl transfer to the 2'-OH of the tRNA terminal ribose

- Slow release of the aminoacyl-tRNA product, which becomes rate-limiting for multiple turnovers [21]

This mechanistic pathway was clearly demonstrated in studies of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CysRS), where product release was identified as the primary constraint on catalytic efficiency [21] [7]. The tight binding of aminoacyl-tRNA products by Class I enzymes has significant biological implications, particularly in their interactions with elongation factor EF-Tu. This tight binding correlates with EF-Tu's ability to form ternary complexes specifically with Class I synthetases and even enhance their aminoacylation rates [21].

Structural Correlates of Kinetic Behavior

The structural foundations for these kinetic differences stem from the distinct protein folds and active site architectures of the two classes. Class I enzymes feature a Rossmann fold catalytic domain characterized by parallel β-sheets flanked by α-helices, while Class II enzymes exhibit a catalytic fold built around antiparallel β-sheets [12]. These topological differences dictate not only their kinetic mechanisms but also their regioselectivity—Class I enzymes primarily aminoacylate the 2'-OH of the terminal ribose, whereas Class II enzymes prefer the 3'-OH position [12].

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Burst Kinetics

Rapid Chemical Quench-Flow Technique

The rapid chemical quench-flow method allows researchers to monitor reaction progress on millisecond timescales, essential for capturing the burst phase [12].

Protocol 4.1.1: Rapid Quench-Flow Assay for Burst Kinetics

Principle: This technique rapidly mixes enzyme and substrate solutions, then quenches the reaction at precise time intervals to quantify product formation during the initial catalytic cycle.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified AARS enzyme (≥95% purity)

- Cognate tRNA transcript (prepared by in vitro transcription)

- Radioactive [α-32P]ATP or [³H]amino acid

- Rapid quench-flow instrument (e.g., KinTek RQF-3)

- Quench solution (1-2 N acetic acid or 5 M urea)

- Separation materials for product analysis (TLC plates, cellulose filters)

Procedure:

- Enzyme-TRNA Complex Formation: Pre-incubate 10-50 μM AARS enzyme with 2-5 μM cognate tRNA in reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM DTT) for 2 minutes at 25°C.

- Reaction Initiation: Rapidly mix equal volumes (20-50 μL) of the enzyme-tRNA complex with a solution containing 1 mM ATP and 50 μM cognate amino acid (including trace radioactive label) in the quench-flow instrument.

- Time-Course Quenching: Quench reactions at time intervals from 5 ms to 30 s using acidic or denaturing quench solution.

- Product Quantification: Separate aminoacyl-tRNA from unincorporated label using TLC or acid-precipitation methods and quantify using scintillation counting.

- Data Analysis: Plot product concentration versus time and fit to the burst equation: [[AA-tRNA] = A(1 - e^{-k1 t}) + k2 t] where A is burst amplitude, k₁ is the burst rate constant, and k₂ is the steady-state rate.

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Stopped-flow fluorescence exploits intrinsic protein fluorescence changes that accompany catalytic steps, providing real-time monitoring of the reaction sequence [12].

Protocol 4.2.1: Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Detection of Burst Kinetics

Principle: Conformational changes during the aminoacylation reaction alter the microenvironment of tryptophan residues in the AARS active site, causing measurable fluorescence quenching or enhancement.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Stopped-flow spectrofluorometer

- Purified AARS enzyme with native tryptophan residues

- Cognate tRNA (in vitro transcript or purified native tRNA)

- ATP, amino acid substrates

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Configure stopped-flow instrument for excitation at 295 nm (tryptophan-specific) and emission detection above 320 nm using appropriate cut-off filters.

- Sample Loading: Load one syringe with 2-5 μM AARS enzyme in reaction buffer. Load second syringe with substrate mixture containing 50 μM tRNA, 1 mM ATP, and 100 μM cognate amino acid.

- Rapid Mixing and Data Collection: Rapidly mix equal volumes (50-100 μL) while monitoring fluorescence changes with time resolution of 1-10 ms.

- Data Fitting: Analyze fluorescence traces using double-exponential equations characteristic of burst kinetics: [F(t) = A1 e^{-k1 t} + A2 e^{-k2 t} + C] where k₁ represents the rapid burst phase and k₂ the slower steady-state phase.

Table 2: Key Kinetic Parameters Obtainable from Burst Kinetics Experiments

| Parameter | Interpretation | Method of Determination | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burst Amplitude (A) | Concentration of catalytically active enzyme sites | Extrapolation of burst phase to t=0 | Active site quantification, functional purity assessment |

| Burst Rate Constant (k₁) | Intrinsic rate of aminoacyl transfer | Exponential fitting of burst phase | Chemical step efficiency, transition state stability |

| Steady-State Rate (k₂ or kcat) | Turnover rate limited by product release | Linear phase slope after burst | Overall catalytic efficiency in multiple cycles |

| Km for tRNA | Apparent binding affinity | Variation of substrate concentration | tRNA recognition specificity, ground state binding |

Research Reagent Solutions for AARS Kinetic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AARS Burst Kinetics Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| tRNA Preparations | In vitro T7 transcripts, Native tRNA from overexpressing strains, Chemically synthesized tRNA halves | Substrate for aminoacylation, structural studies | Transcripts lack modifications but offer homogeneity; native tRNA contains natural modifications but may be heterogeneous [12] |

| Radiolabeled Substrates | [α-³²P]ATP, [γ-³²P]ATP, ³H- or ¹⁴C-labeled amino acids | Quantification of reaction products via scintillation counting | [α-³²P]ATP for aminoacylation assays; [γ-³²P]ATP for pyrophosphate exchange [12] |

| Specialized Equipment | Rapid chemical quench instrument, Stopped-flow spectrofluorometer | Pre-steady state kinetic measurements | Quench-flow for direct product quantification; stopped-flow for conformational changes [12] |

| Purified AARS Enzymes | Recombinant His-tagged enzymes, Wild-type and mutant variants, Full-length and truncated forms | Functional and structural studies | C-terminal tags often preserve function; site-directed mutants for mechanistic studies [23] |

| Separation Materials | Cellulose filters, TLC plates, Acidic precipitation solutions | Product separation and purification | TLC for adenylate intermediates; acidic precipitation for aminoacyl-tRNA [12] |

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Kinetic Quality Control in Eukaryotic AARS Systems

The burst kinetics signature has revealed sophisticated regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic AARS enzymes. Research on human cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CysRS) demonstrated that a eukaryotic-specific C-terminal extension domain enhances anticodon recognition specificity but concomitantly slows the aminoacylation rate [23]. This creates a previously unrecognized kinetic quality control mechanism where improved specificity is achieved at the expense of catalytic speed—an evolutionary adaptation potentially linked to changes in codon usage patterns from prokaryotes to eukaryotes [23].

Implications for Drug Discovery

The distinct kinetic mechanisms of Class I and Class II AARS enzymes present unique opportunities for targeted inhibitor development. Class I AARS enzymes, with their characteristic product release limitation, may be particularly susceptible to transition state analogs that mimic the aminoacyl-tRNA product. Several AARS enzymes are established targets for antibacterial and antifungal agents, and understanding their burst kinetics can guide the optimization of inhibitor residence times and therapeutic efficacy [21] [7].

Burst kinetics provides a fundamental mechanistic signature that distinguishes Class I from Class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, with Class I enzymes exhibiting this characteristic due to rate-limiting product release. The experimental approaches outlined—particularly rapid quench-flow and stopped-flow fluorescence techniques—enable researchers to quantify these kinetic phenomena and extract critical parameters governing catalytic efficiency. As research advances, the application of these kinetic principles continues to reveal sophisticated quality control mechanisms in eukaryotic systems and informs the development of novel therapeutics targeting pathogen-specific AARS enzymes. The continued investigation of burst kinetics remains essential for a comprehensive understanding of translation fidelity and its modulation in health and disease.

The Biological Significance of AARS Kinetics in Translation Fidelity

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs) are essential enzymes that interpret the genetic code by catalyzing the covalent attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs, forming aminoacyl-tRNAs (aa-tRNAs) [24] [12]. This reaction, known as aminoacylation, provides the correct substrates for ribosomal protein synthesis. The fidelity of this process is fundamental to cellular integrity, as inaccuracies can lead to protein misfolding and aggregation, which have been associated with neurodegenerative diseases [25]. AARSs achieve remarkable specificity through high-fidelity substrate selection and proofreading (editing) mechanisms [24] [26]. Kinetic analysis of AARSs is therefore crucial for understanding the mechanistic basis of translational fidelity. This application note details the key kinetic principles, experimental protocols, and analytical tools for investigating AARS function, framed within the context of a broader thesis on kinetic analysis methods.

Kinetic Mechanisms of AARSs and Translational Fidelity

The Two-Step Aminoacylation Reaction

AARSs catalyze aminoacylation via two sequential steps [12] [4]:

- Amino Acid Activation: The amino acid (AA) is activated by ATP to form an enzyme-bound aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate (AA-AMP), releasing inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi).

E + AA + ATP ⇄ E•AA~AMP + PPi - Aminoacyl Transfer: The aminoacyl moiety is transferred from the adenylate to the 2' or 3' hydroxyl group of the terminal adenosine (A76) of the cognate tRNA.

E•AA~AMP + tRNA^AA ⇄ E + AA-tRNA^AA + AMP

The regiochemistry of the transfer step is a key distinguishing feature between the two AARS classes: Class I synthetases primarily aminoacylate the 2'-OH, while Class II synthetases generally use the 3'-OH [6].

Kinetic Partitioning and Proofreading Mechanisms

For many AARSs, selective amino acid activation in the synthetic site is insufficient to achieve the required fidelity for protein synthesis. Approximately half of AARSs employ proofreading (editing) mechanisms to clear noncognate products [24]. These pathways can be categorized as:

- Pre-transfer Editing: Hydrolysis of the noncognate aminoacyl-adenylate (aa-AMP) before transfer to tRNA. This can occur via selective release followed by nonenzymatic hydrolysis, or via enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis within the synthetic site [26].

- Post-transfer Editing: Translocation and hydrolysis of the misacylated tRNA (aa-tRNA) within a dedicated editing domain (e.g., the CP1 domain in class I IleRS, ValRS, and LeuRS) [26].

The balance between these pathways is governed by kinetic partitioning, where the relative rates of transfer versus hydrolysis of the noncognate aa-AMP determine the predominant editing route [26]. For instance, E. coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase (LeuRS) relies almost entirely on post-transfer editing to clear the nonproteinogenic amino acid norvaline, whereas isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (IleRS) utilizes significant tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for noncognate valine [26].

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters for Representative AARSs

| AARS (Organism) | Class | Aminoacyl Transfer Rate (k~chem~, s⁻¹) | Steady-State Turnover (k~cat~, s⁻¹) | Rate-Limiting Step | Primary Editing Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CysRS (E. coli) [6] | I | ~25 | ~4 | Product Release (Burst Kinetics) | N/A |

| ValRS (E. coli) [6] | I | ~7 | ~2 | Product Release (Burst Kinetics) | Post-transfer |

| LeuRS (E. coli) [26] | I | Not Specified | Not Specified | Post-transfer Editing Product Release | Post-transfer (for norvaline) |

| AlaRS (E. coli) [6] | II | ~20 | ~6 | Chemistry (No Burst) | Pre-transfer |

| ProRS (D. radiodurans) [6] | II | ~3 | ~0.7 | Chemistry (No Burst) | Pre-transfer |

Distinct Kinetic Behaviors of Class I and Class II AARSs

Pre-steady-state kinetic studies reveal a fundamental mechanistic distinction between the two AARS classes. Class I synthetases (e.g., CysRS, ValRS, GlnRS) typically exhibit burst kinetics, where the rapid chemical step (aminoacyl transfer) is followed by a slower, rate-limiting product release step (often release of aa-tRNA) [6]. In contrast, Class II synthetases (e.g., AlaRS, ProRS, HisRS) generally do not show a burst, indicating that a step prior to aminoacyl transfer, most likely the activation step itself, is rate-limiting for the overall reaction [6]. This distinction has biological implications, as the tight product binding in Class I enzymes may necessitate the elongation factor EF-Tu (eEF1A in eukaryotes) to facilitate the release of aa-tRNA from the synthetase for efficient delivery to the ribosome [6].

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Analysis

Preparation of tRNA Substrates

The quality of tRNA is critical for reliable kinetics. Three primary methods are employed [12] [4]:

- Purification from Overexpressing Cells: Yields tRNA with natural nucleobase modifications, which can be essential for efficient recognition by some AARSs (e.g., GluRS, ThrRS). The main challenge is achieving homogenous preparations.

- In Vitro Transcription using T7 RNA Polymerase: The most general method for producing large quantities of homogenous tRNA. The resulting transcripts lack modified nucleotides, which can affect kinetics for some systems.

- Chemical Synthesis and Ligation: Used for producing specific tRNA variants or fragments, allowing for the incorporation of non-standard nucleotides.

Steady-State Kinetic Assays

Steady-state kinetics provides an initial, quantitative characterization of AARS function and is advantageous for screening large numbers of enzyme or tRNA variants [12] [4].

Protocol 1: ATP/PPi Exchange Assay (Measures Activation Step)

- Principle: This equilibrium-based assay monitors the amino acid-dependent incorporation of radiolabeled (^{32})P from [(^{32})P]PPi into ATP during the reversible activation reaction [2].

- Modern Variation ([(^{32})P]ATP/PPi Assay): Due to the discontinuation of [(^{32})P]PPi, a modified assay using readily available γ-[(^{32})P]ATP has been developed. The reaction is quenched with acidic charcoal, which binds nucleotides (ATP, ADP, AMP). The unreacted [(^{32})P]ATP is adsorbed, while the synthesized [(^{32})P]PPi remains in the supernatant for scintillation counting [2].

- Application: Ideal for initial characterization and large-scale inhibitor screens, as it does not require tRNA [2].

Protocol 2: Aminoacylation Assay (Measures Overall Aminoacylation)

- Principle: This assay directly measures the formation of aminoacyl-tRNA. The reaction uses a radiolabeled amino acid (e.g., [(^{35})S]-Cysteine, [(^{3})H]-Isoleucine) [6].

- Procedure: Reaction aliquots are quenched on acidified filter papers. The charged tRNA is precipitated and retained on the filter, while uncharged amino acid is washed away. The radioactivity retained on the filter is quantified by scintillation counting [12] [6].

- Data Analysis: Initial velocities are determined at varying substrate concentrations and fitted to the Michaelis-Menten model to derive (Km) and (k{cat}) values.

Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Assays

Pre-steady-state kinetics is required to dissect individual elementary steps (e.g., substrate binding, chemical catalysis, product release) and determine their kinetic and thermodynamic contributions [12].

Protocol 3: Rapid Chemical Quench Flow

- Principle: Reactants (e.g., AARS, ATP, amino acid, tRNA) are rapidly mixed and the reaction is halted after very short time intervals (milliseconds to seconds) by a quenching agent (e.g., acid, denaturant) [6].

- Analysis: The quenched samples are analyzed for product formation (e.g., AA-tRNA, AMP) using methods like the aminoacylation assay or HPLC. The time course of product formation reveals the rate constants for chemical steps ((k_{chem})).

- Application: Used to demonstrate burst kinetics in Class I AARSs, where a rapid, single-turnover "burst" of AA-tRNA formation is followed by slower steady-state turnover [6].

Protocol 4: Stopped-Flow Fluorescence

- Principle: Changes in the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of the AARS, which often occur upon substrate binding or conformational changes, are monitored in real-time after rapid mixing.

- Analysis: The fluorescence transients are recorded and fitted to exponential functions to obtain observed rate constants ((k_{obs})). By varying substrate concentrations, the mechanism of binding and conformational changes can be elucidated.

- Application: Useful for studying the kinetics of substrate association/dissociation and induced-fit conformational transitions [12].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Kinetic Assays for AARS Research

| Assay Type | Measured Parameter | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP/PPi Exchange [2] [4] | Rate of amino acid activation | Does not require tRNA; good for initial screens | Indirect measurement; does not assess transfer step | High |

| Aminoacylation [12] [4] | Overall rate of AA-tRNA synthesis | Directly measures physiological product | Requires high-quality tRNA preparation | Medium |

| Rapid Chemical Quench [12] [6] | Rate constants for chemical steps (e.g., (k_{chem})) | Direct measurement of elemental steps | Requires specialized instrument & large amounts of materials | Low |

| Stopped-Flow Fluorescence [12] | Rates of conformational changes & binding | High temporal resolution; observes intermediates | Requires a fluorescent signal change; can be indirect | Low |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AARS Kinetics

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in AARS Research |

|---|---|---|

| γ-[(^{32})P]ATP [2] | Radiolabeled cofactor | Tracer for the modern [(^{32})P]ATP/PPi exchange assay to study the activation step. |

| [(^{35})S]-Amino Acids [6] | Radiolabeled substrates | Tracer for aminoacylation assays and single-turnover quench-flow experiments. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase [12] | RNA synthesis enzyme | Production of homogenous, unmodified tRNA transcripts for kinetic studies. |

| Rapid Quench Instrument | Stopping reactions on millisecond timescale | Essential apparatus for pre-steady-state kinetics to measure chemical step rates ((k_{chem})). |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrofluorimeter | Monitoring rapid fluorescence changes | Studying real-time conformational dynamics and substrate binding events. |

Software for Kinetic Data Analysis

- Commercial SPR Software: Tools like Carterra Kinetics Software and others are optimized for high-throughput kinetics screening (e.g., of up to 1,152 antibody-antigen interactions), offering robust global fitting algorithms for binding data [27] [28].

- Open-Source Solutions: IOCBIO Kinetics is an open-source Python program designed for reproducible primary analysis of time-course data. It facilitates data storage, fitting, and visualization, supporting FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles [29].

- Custom Scripting Tools: Packages like TitrationAnalysis for Mathematica provide a flexible environment for high-throughput fitting of binding kinetics data from multiple label-free platforms (SPR, BLI), serving as a powerful alternative to commercial software [28].

Steady-State and Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Assays: A Practical Guide

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs) are essential enzymes that decode genetic information by coupling cognate amino acids to their corresponding tRNAs, a prerequisite for ribosomal protein synthesis [2] [3]. The aminoacylation reaction catalyzed by AARSs proceeds in two discrete chemical steps: first, the activation of the amino acid by ATP to form an aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate (aa-AMP) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi); and second, the transfer of the aminoacyl moiety to the 3' end of the cognate tRNA [3] [12].

The ATP/PPi exchange assay is a cornerstone method in enzymology, specifically designed to monitor the first activation step independently of the subsequent transfer step [12]. This assay provides critical insights into the kinetic parameters and substrate specificity of AARSs and is widely used in screens for AARS-targeting inhibitors [2] [3]. For decades, the standard protocol relied on radiolabelled [32P]PPi. However, with its recent discontinuation, a modified assay using the readily available γ-[32P]ATP has been developed, ensuring the continued utility of this method [2] [3].

This application note details the principles, protocols, and key applications of the modern ATP/PPi exchange assay, framing it within the broader context of kinetic analysis for AARS research.

Principle of the Assay

Biochemical Basis

The ATP/PPi exchange assay is an isotopic equilibrium exchange method that tracks the reverse reaction of the adenylation step [12]. In the presence of AARS, the amino acid activation reaction is reversible. The assay measures the incorporation of a radioactive label from PPi into ATP or, in the modern format, from ATP into PPi.

The core reversible reaction is: Amino Acid + ATP ⇄ Aminoacyl-AMP + PPi

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and principle of the modified [32P]ATP/PPi exchange assay.

Evolution from Standard to Modified Assay

The classic ATP/[32P]PPi exchange assay introduced in the 1960s used [32P]PPi as the radioactive tracer. The discontinuation of this reagent in 2022 necessitated an adaptation. The modern [32P]ATP/PPi assay inverts the labeling strategy by using γ-[32P]ATP as the labeled substrate and tracking the formation of [32P]PPi. Studies have confirmed that kinetic constants obtained with this modified assay are in excellent agreement with those from the traditional method [2] [3].

Experimental Protocol

Reagents and Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for the [32P]ATP/PPi Exchange Assay

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in the Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Buffer | HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), MgCl₂, KCl, DTT, BSA | Maintains optimal pH, ionic strength, and reducing conditions; stabilizes the enzyme [3]. |

| Unlabeled Substrates | Amino Acid (e.g., L-Leucine), ATP, Sodium Pyrophosphate (PPi) | Substrates for the enzymatic activation reaction [3]. |

| Radiolabeled Substrate | γ-[32P]ATP | Tracer for monitoring the exchange reaction; its conversion to [32P]PPi is measured [2] [3]. |

| Quench Solution | Sodium Acetate, Acetic Acid, Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate (SDS) | Stops the enzymatic reaction and denatures the protein [3]. |

| Chromatography | Polyethylenimine (PEI) TLC Plates, Urea, KH₂PO₄, H₃PO₄ | Stationary and mobile phases for separating [32P]PPi from γ-[32P]ATP [3]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Reaction Mixture Setup: Prepare the master mix on ice. A standard mixture contains:

- Reaction Buffer (e.g., 20-50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5)

- Magnesium chloride (e.g., 10 mM)

- Potassium chloride (e.g., 50 mM)

- Dithiothreitol (DTT, e.g., 2 mM)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, e.g., 100 µg/mL)

- Amino acid substrate (at desired concentration)

- Unlabeled ATP (e.g., 2-5 mM)

- Unlabeled sodium pyrophosphate (e.g., 1-5 mM)

- Purified AARS enzyme [3].

Initiation and Incubation: Start the reaction by adding γ-[32P]ATP. Mix thoroughly and incubate at the desired temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C). Use a dry block heater or thermostated water bath [3].

Quenching: At predetermined time intervals, withdraw an aliquot (e.g., 5-10 µL) from the reaction and transfer it to a tube containing a larger volume (e.g., 10-20 µL) of quench solution (e.g., 2 M sodium acetate, 2% SDS, pH 5.0). This step immediately halts the enzymatic activity [3].

Separation by Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC):

- Spot the quenched reaction samples onto a Polyethylenimine (PEI) TLC plate.

- Develop the plate in a glass chamber containing a mobile phase, typically composed of urea and potassium dihydrogen phosphate, adjusted to pH with phosphoric acid [3].

- Allow the mobile phase to migrate sufficiently to separate ATP (which remains near the origin) from PPi (which migrates farther).

Visualization and Quantification:

- Dry the TLC plate thoroughly.

- Expose a phosphor storage screen to the plate.

- Scan the screen using a biomolecular imager (e.g., Typhoon imager).

- Quantify the intensity of the [32P]PPi spots using software such as ImageQuant [3].

Data Analysis and Kinetic Parameter Calculation

The rate of [32P]PPi formation is proportional to the rate of the adenylation reaction. To determine the steady-state kinetic parameters, ( Km ) (Michaelis constant) and ( k{cat} ) (catalytic constant), the initial velocity of the exchange reaction is measured at varying concentrations of one substrate (e.g., the amino acid) while keeping the other substrates (ATP and PPi) at saturating concentrations.

Table 2: Example Kinetic Data for AARS Enzymes Obtained via the [32P]ATP/PPi Exchange Assay

| AARS Enzyme | Amino Acid Substrate | Apparent ( K_m ) (μM) | ( k_{cat} ) (s⁻¹) | ( k{cat}/Km ) (s⁻¹ M⁻¹) | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IleRS | Isoleucine | 5 - 50 | 1 - 10 | ~2.0 × 10⁵ | Representative range; data agrees with classic assay [2] [3] |

| LeuRS | Leucine | 10 - 100 | 2 - 20 | ~2.5 × 10⁵ | Representative range; data agrees with classic assay [2] [3] |

| Class I AARS (e.g., IleRS) | Cognate AA | Generally lower ( K_m ) | Often exhibits burst kinetics | Varies by enzyme | [7] |

| Class II AARS (e.g., SerRS) | Cognate AA | Generally higher ( K_m ) | No burst kinetics | Varies by enzyme | [7] |

The data are typically fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression to extract ( Km ) and ( V{max} ). The ( k{cat} ) is then calculated from ( V{max} ) and the known enzyme concentration [12].

Applications in AARS Research and Drug Discovery

The ATP/PPi exchange assay is a versatile tool with several critical applications in basic and applied research:

Initial Kinetic Characterization: It allows for the rapid determination of an AARS's affinity (( Km )) and catalytic efficiency (( k{cat}/K_m )) for its amino acid substrate without the need for purified tRNA, which can be laborious to produce [2] [3].

Investigation of Substrate Specificity and Fidelity: The assay is ideal for probing the enzyme's ability to discriminate against non-cognate or non-standard amino acids. This helps elucidate the mechanisms that ensure translational fidelity and is fundamental to understanding AARS editing functions [30] [12].

High-Throughput Inhibitor Screening: As AARSs are validated targets for antibiotic and therapeutic development, the assay can be adapted to screen large libraries of small molecules for inhibitors that block the amino acid activation step [2] [30]. The modified [32P]ATP/PPi assay, using a readily available radiolabel, facilitates this crucial drug discovery application.

Comparison with Other Kinetic Methods

While powerful, the ATP/PPi exchange assay is one of several methods used for AARS kinetic analysis. The table below compares key techniques.

Table 3: Comparison of Key Kinetic Assays for Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Research

| Assay Name | Reaction Step Measured | Key Readout | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32P]ATP/PPi Exchange | Amino Acid Activation | Formation of [32P]PPi from γ-[32P]ATP | Does not require tRNA; uses readily available γ-[32P]ATP [2] [3]. | Measures equilibrium exchange, not single-turnover rates; uses radioactivity. |

| Aminoacylation (Radioactive) | Cumulative Two-Step Reaction | Formation of AA-[3H/14C/35S]-tRNA or [32P]-AA-tRNA | Measures the overall, biologically relevant reaction [30] [12]. | Requires purified tRNA; results can be complex due to two-step mechanism. |

| Coupled Spectrophotometric/Luminescent | Amino Acid Activation (via PPi) | Absorbance/Luminescence change from coupled enzymes (e.g., MESG/Malachite Green) [30]. | Avoids radioactivity; amenable to HTS. | Potential interference from test compounds; additional components increase complexity. |

| Pre-steady-state Kinetics (Rapid Quench) | Elementary Steps (e.g., chemistry) | Direct chemical quantification of intermediates/products (e.g., aa-AMP) at millisecond timescales [12]. | Reveals individual rate constants and transient kinetics. | Requires specialized, expensive equipment; high enzyme consumption. |

| Stopped-Flow Fluorescence | Conformational Changes & Binding | Change in intrinsic (tryptophan) or extrinsic fluorescence | Very high temporal resolution; probes dynamics beyond chemistry. | Requires a fluorescence signal change; can be complex to interpret. |

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) are essential enzymes that covalently link transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules with their cognate amino acids, forming aminoacyl-tRNAs (aa-tRNAs). This process, known as aminoacylation or tRNA charging, is a critical step in protein synthesis, ensuring the accurate translation of genetic information from messenger RNA into polypeptide sequences [31]. The aaRS enzymes catalyze a two-step reaction: first, they activate the amino acid using ATP to form an aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate (aa-AMP); second, they transfer the activated amino acid to the 3'-end of the appropriate tRNA [4] [32]. Cumulative aminoacylation assays monitor the overall formation of aa-tRNA through this complete two-step process, providing researchers with crucial insights into the kinetics, fidelity, and regulation of protein synthesis. These assays are fundamental tools for characterizing aaRS function, studying translational fidelity, and screening for potential therapeutics that target these essential enzymes [2] [32].

The Central Role of Aminoacylation in Protein Synthesis

The accurate charging of tRNAs by aaRSs represents a key checkpoint for the fidelity of the genetic code. Each of the 20 standard amino acids has a corresponding aaRS that specifically recognizes both the amino acid and its cognate tRNA(s) [31]. The reaction follows a conserved mechanism:

Step 1: Amino Acid Activation [ \text{Amino Acid + ATP} \xrightarrow{\text{aaRS, Mg}^{2+}} \text{aa-AMP + PP}_i ] In this initial activation step, the carboxyl group of the amino acid attacks the α-phosphate of ATP, forming an aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate (aa-AMP) and releasing inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) [4].

Step 2: tRNA Charging [ \text{aa-AMP + tRNA}^{AA} \xrightarrow{\text{aaRS}} \text{aa-tRNA}^{AA} + \text{AMP} ] The activated amino acid is then transferred from aa-AMP to the 2'- or 3'-hydroxyl group of the terminal adenosine of the cognate tRNA, resulting in the formation of aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) and AMP [4].

The cumulative aminoacylation assay monitors the final product of this two-step process—the formation of aa-tRNA—making it a direct measure of the functional output of the aaRS enzyme [7].

Established Methods for Monitoring Cumulative aa-tRNA Formation

Radioactive Assay Using Radiolabeled Amino Acids

The classical and most direct method for monitoring cumulative aa-tRNA formation utilizes radiolabeled amino acids. This approach provides high sensitivity and is considered a gold standard in the field [4] [7].

Experimental Protocol:

Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mixture containing:

- Purified aaRS enzyme

- Total tRNA or specific cognate tRNA

- ATP and Mg²⁺ as essential cofactors

- Amino acid mixture including the radiolabeled cognate amino acid (e.g., ³H, ¹⁴C, or ³⁵S-labeled)

- Appropriate reaction buffer (typically HEPES or Tris, pH 7.5, with KCl and DTT)

Incubation and Quenching: Incubate the reaction at the desired temperature (e.g., 37°C). At predetermined time intervals, withdraw aliquots and spot them onto filter discs pre-treated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or another acidic quenching solution.

Washing and Quantification: Wash the filter discs extensively with cold TCA to remove unincorporated radiolabeled amino acid. The charged aa-tRNA is precipitated and retained on the filter. Dry the discs and quantify the radioactivity using a scintillation counter.

Data Analysis: Plot the amount of radiolabeled aa-tRNA formed versus time. From this progress curve, steady-state kinetic parameters ((k{cat}) and (Km)) for the amino acid, ATP, and tRNA can be determined [4].

Diagram 1: Workflow for radioactive aminoacylation assay.

Continuous Colorimetric and Coupled Enzyme Assays

To circumvent the use of radioactivity, several continuous, label-free assays have been developed. These methods typically monitor the consumption of ATP or the formation of reaction byproducts (AMP or PPi) that are stoichiometric with aa-tRNA formation [32].

Common Continuous Assay Strategies:

- AMP Detection: Couples AMP formation to the oxidation of NADH, which is monitored by a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm. This requires the coupling enzymes AMP deaminase and IMP dehydrogenase [32].

- PPi Detection: Involves two common approaches:

- Malachite Green Method: Inorganic pyrophosphatase (PPase) converts PPi to inorganic phosphate (Pi), which is then detected using the malachite green reagent, resulting in a colorimetric shift [32].

- Enzymatic Coupling: Uses purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNPase) with the substrate MESG. The PPi is converted to Pi by PPase, and PNPase uses this Pi to convert MESG to a product that can be monitored spectrophotometrically [32].

Experimental Protocol (PPi Detection via Malachite Green):

- Reaction Setup: Assemble the aminoacylation reaction as described in section 3.1, but with non-radioactive amino acids. Include inorganic pyrophosphatase in the reaction mixture.

- Continuous Monitoring: After initiating the reaction, add aliquots of the reaction mix to the malachite green solution at various time points.

- Signal Measurement: Immediately measure the absorbance at 620-660 nm. The increase in absorbance is proportional to the amount of Pi released, which in turn is equivalent to the amount of aa-tRNA formed.

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve with known Pi concentrations to convert absorbance values to nmoles of aa-tRNA.

Novel High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assays

For drug discovery efforts targeting aaRSs, HTS-compatible assays are essential. A recent innovative approach leverages the natural editing activity of some aaRSs to create a sensitive, continuous, and multi-enzyme assay [32].

Experimental Protocol (Editing-Based HTS Assay):

- Reaction Principle: This assay simultaneously monitors the synthetic and editing activities of up to four different aaRSs. For an aaRS with editing capability, a mischarged tRNA (e.g., Tyr-tRNA^Phe) is hydrolyzed (edited) in the proofreading site, releasing the non-cognate amino acid and free tRNA. The free tRNA is then available for another round of (correct) aminoacylation by its cognate aaRS.

- Reaction Setup: Combine multiple aaRSs, their cognate tRNAs, amino acids, and ATP in a single well. The recycling of tRNAs through successive rounds of mischarging and editing amplifies the signal (ATP consumption/AMP production).

- Signal Detection: Monitor the reaction using one of the continuous ATP/AMP detection methods described above (e.g., luciferase-based ATP depletion or enzymatic coupling for AMP detection).

- Application: This method allows for the simultaneous screening of inhibitors targeting the synthetic sites of multiple aaRSs and/or the editing sites of proofreading aaRSs in a single experiment, dramatically increasing screening efficiency [32].

Key Kinetic Parameters and Data Interpretation

Cumulative aminoacylation assays provide the steady-state kinetic parameters that define an aaRS's catalytic efficiency and substrate affinity. The most common parameters obtained are (k{cat}) (the catalytic turnover number) and (Km) (the Michaelis constant for a substrate). The ratio (k{cat}/Km) represents the catalytic efficiency.

Table 1: Key Steady-State Kinetic Parameters from Cumulative Aminoacylation Assays

| Parameter | Definition | Interpretation in Aminoacylation |

|---|---|---|

| (k_{cat}) (s⁻¹) | The maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per second. | Represents the overall turnover rate of the complete two-step aminoacylation reaction under saturating substrate conditions. |

| (K_m) (M) | The substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of (V_{max}). | Reflects the apparent affinity of the aaRS for a given substrate (amino acid, ATP, or tRNA). A lower (K_m) indicates higher affinity. |

| (k{cat}/Km) (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | The specificity constant, measuring the enzyme's catalytic efficiency. | Determines the efficiency with which the enzyme converts a specific substrate to aa-tRNA at low substrate concentrations. |

It is important to note that the observed (k{cat}) and (Km) are global parameters that reflect a combination of all the microscopic rate constants for the individual steps in the catalytic cycle, including substrate binding, chemistry, and product release [4]. For class I aaRSs, the aminoacylation reaction often exhibits burst kinetics, where a rapid, initial formation of aa-tRNA (the burst phase) is followed by a slower, linear steady-state phase. The burst phase reflects the fast initial charging of enzyme-bound tRNA, while the slower linear phase is often limited by the release of the charged tRNA from the enzyme [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Aminoacylation Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|