Inverse Molecular Design Using Generative AI: A New Paradigm for Accelerated Drug and Material Discovery

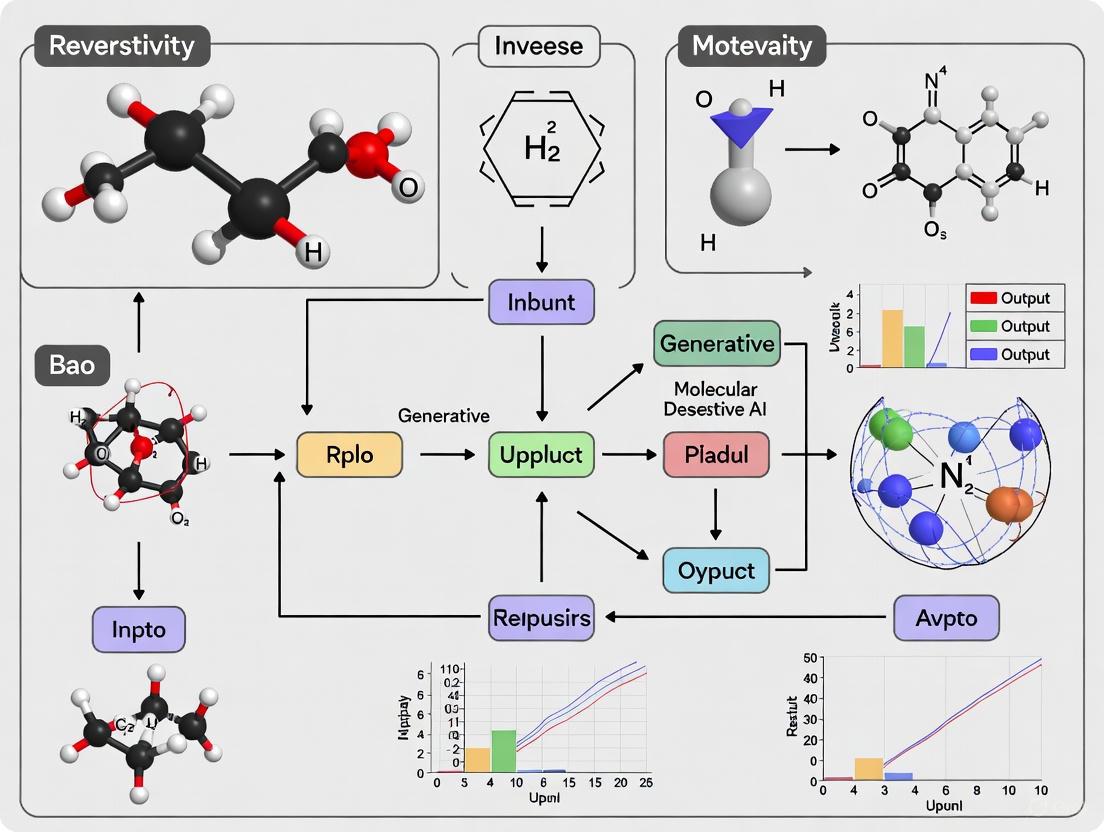

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative field of inverse molecular design powered by generative artificial intelligence (GenAI).

Inverse Molecular Design Using Generative AI: A New Paradigm for Accelerated Drug and Material Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative field of inverse molecular design powered by generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). Moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods, GenAI enables the de novo creation of molecules tailored to specific properties. We explore the foundational principles of this paradigm shift, detail key generative architectures like diffusion models, GANs, and VAEs, and examine their application in designing small molecules and materials. The content addresses critical optimization strategies and persistent challenges, including data scarcity and model interpretability. Finally, we present rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of state-of-the-art models, offering researchers and drug development professionals a roadmap for leveraging GenAI to expedite the discovery of novel therapeutics and functional materials.

From Rational Design to AI-Driven Generation: The Foundations of Inverse Molecular Design

The discovery of new molecules for pharmaceuticals and advanced materials has long been a painstaking process, largely dependent on serendipity and laborious trial-and-error experimentation. This traditional approach, sometimes characterized as "looking for a key under the lamppost," is fundamentally limited by human bias, high costs, and extensive timelines. The emergence of inverse molecular design powered by generative artificial intelligence (AI) represents a definitive paradigm shift in this field. Unlike traditional methods that proceed from structure to property, inverse design flips this relationship entirely, starting with desired properties and working backward to generate optimal molecular structures that meet these specifications. This approach leverages powerful AI models to efficiently navigate the vast chemical space, which is estimated to contain up to 10^60 feasible compounds, a scope utterly intractable for traditional methods [1]. The result is a dramatic acceleration in the pace of molecular discovery, with applications spanning from drug development to materials science.

Core Principles: Contrasting the Traditional and Inverse Design Approaches

Traditional Molecular Design Approach

The traditional molecular design process follows a linear, iterative cycle that heavily relies on researcher intuition and prior knowledge of structure-property relationships. This process typically begins with a hypothesis about which molecular structures might exhibit a desired property, such as therapeutic activity against a specific biological target. Researchers then synthesize candidate compounds based on known chemical templates or minor modifications of existing active compounds. These candidates undergo experimental testing, and the results inform the next round of structural modifications, creating a slow, costly cycle of "design-make-test-analyze" that can repeat numerous times before identifying a viable candidate.

This approach faces several fundamental limitations:

- Heavy reliance on existing chemical knowledge, limiting exploration to known structural regions

- High experimental burden requiring synthesis and testing of numerous candidates

- Long development timelines often spanning several years for a single optimization campaign

- Prohibitive costs associated with extensive laboratory work and compound characterization

- Human cognitive bias that restricts exploration of chemically novel territories

Inverse Molecular Design Approach

Inverse molecular design fundamentally reengineers this discovery process through a targeted, computational-first methodology. Rather than iterating from structure to property, it begins by defining the target property profile and employs generative AI models to directly propose molecular structures that satisfy these requirements. This represents a true inversion of the traditional design paradigm.

The core enabling technology is generative AI, which learns the complex relationships between chemical structures and their properties from existing datasets. Once trained, these models can propose novel molecular structures optimized for specific target properties, dramatically accelerating the exploration of chemical space. Key methodological frameworks enabling this approach include:

- Conditional generative neural networks that learn to sample 3D molecular structures conditioned on specified chemical and structural properties [2]

- Markov molecular sampling with multi-objective optimization (exemplified by the MEMOS framework) for targeted molecular generation [3]

- Retro drug design (RDD) strategies that work backward from desired drug properties to molecular structures [4]

- Physics-informed generative AI that embeds fundamental scientific principles directly into the learning process [5]

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Traditional and Inverse Molecular Design Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Inverse Design Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Known molecular structures or templates | Desired properties or performance criteria |

| Discovery Process | Sequential design-make-test-analyze cycles | Direct generation of candidates meeting targets |

| Chemical Space Exploration | Local exploration around known actives | Global exploration of vast chemical territories |

| Primary Driver | Chemist intuition and experience | Data-driven AI generation and optimization |

| Experimental Role | Primary discovery mechanism | Validation of computationally-predicted candidates |

| Typical Timeline | Years for lead optimization | Weeks to months for candidate generation [6] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent studies directly demonstrate the superior efficiency and success rates of inverse molecular design compared to traditional approaches. The performance differential is particularly evident in hit rates, novelty of generated compounds, and reduction in development timelines.

In pharmaceutical applications, inverse design has shown remarkable results. The Retro Drug Design (RDD) approach generated 180,000 chemical structures targeting μ opioid receptor (MOR) activation and blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, with 78% being chemically valid and 31% falling within the target property space. From 96 commercially available compounds selected for testing, 25 demonstrated MOR agonist activity alongside excellent BBB scores – a hit rate substantially higher than traditional screening methods [4]. This represents a significant reduction in the typical attrition rates seen in conventional drug discovery.

In materials science, the MEMOS framework for designing narrowband molecular emitters demonstrated the ability to efficiently traverse millions of molecular structures within hours, identifying thousands of target emitters with success rates up to 80% as validated by density functional theory calculations [3]. This high-throughput capability stands in stark contrast to traditional materials discovery, which might evaluate only dozens or hundreds of candidates over similar timeframes.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Inverse Design vs. Traditional Approaches

| Performance Metric | Traditional Approach | Inverse Design Approach | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Success Rate/Validation | Low (typically <5% hit rate) | High (up to 80% success rate in validation) [3] | >16x |

| Chemical Novelty | Incremental modifications | High novelty (e.g., 267 of 42,000 AI-generated compounds commercially available) [4] | Significant expansion |

| Exploration Scale | Hundreds to thousands of compounds | Millions of structures in hours [3] | >1000x |

| Development Timeline | 3-6 years for lead optimization | 25-50% reduction in discovery timeline [6] | ~2x acceleration |

| Cost Requirements | High (billions per approved drug) | Significant reduction in early R&D costs | Estimated 25-50% cost savings [6] |

Application Notes: Protocols for Inverse Molecular Design

Protocol 1: Conditional 3D Molecular Generation with cG-SchNet

Application Objective: Generate novel 3D molecular structures with specified electronic properties, structural motifs, or atomic composition.

Background and Principles: Conditional G-SchNet (cG-SchNet) is a generative neural network that addresses the inverse design of 3D molecular structures by learning conditional distributions based on target properties [2]. Unlike graph-based or SMILES-based representations, cG-SchNet operates directly on 3D molecular configurations, making it particularly valuable for systems where bonding is ambiguous or where 3D conformation directly influences properties.

Methodology:

Condition Specification: Define target conditions Λ = (λ₁, ..., λₖ), which may include:

- Scalar electronic properties (e.g., HOMO-LUMO gap, polarizability)

- Vector-valued molecular fingerprints

- Atomic composition constraints

Condition Embedding:

- Embed each condition into a latent vector space

- Scalar properties are expanded on a Gaussian basis

- Vector-valued properties are processed directly by the network

- Atomic composition is represented via weighted atom type embeddings

Autoregressive Structure Generation:

- The model assembles molecules sequentially through the factorization: p(R≤n, Z≤n | Λ) = ∏ᵢ₌₁ⁿ p(rᵢ, Zᵢ | R≤i-1, Z≤i-1, Λ)

- At each step, the model: a. Predicts the next atom type: p(Zᵢ | R≤i-1, Z≤i-1, Λ) b. Predicts the next position based on distances to existing atoms: p(rᵢ | R≤i-1, Z≤i, Λ)

Focus and Origin Tokens:

- Utilize origin tokens to mark the molecular center of mass

- Employ focus tokens to localize atom placement predictions

- These stabilize generation and enable scalable processing

Validation: Generated structures are validated through density functional theory (DFT) calculations to verify that they exhibit the targeted electronic properties within acceptable error margins.

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Molecular Generation with MEMOS Framework

Application Objective: Discover novel molecular emitters with tailored narrowband spectral emissions for organic display technology.

Background and Principles: The MEMOS framework combines Markov molecular sampling with multi-objective optimization to address the inverse design challenge of creating molecules capable of emitting narrow spectral bands at desired colors [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for developing next-generation organic display materials with extensive color gamut and unparalleled color purity.

Methodology:

Target Definition:

- Specify target emission wavelengths or colors

- Define narrowband emission criteria

- Set additional objectives (e.g., stability, synthetic accessibility)

Self-Improving Iterative Process:

- Initialize with a diverse set of molecular structures

- Employ Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling to explore chemical space

- Apply multi-objective optimization to steer generation toward target properties

- Iteratively refine the model based on successful candidates

Chemical Space Navigation:

- Efficiently traverse millions of molecular structures within hours

- Prioritize regions of chemical space with high potential for target properties

- Apply chemical validity constraints throughout the process

Validation and Retrieval:

- Validate candidates using density functional theory calculations

- Compare against known experimental literature for verification

- Assess novelty and performance relative to existing compounds

Key Advantage: MEMOS successfully retrieved well-documented multiple resonance cores from experimental literature and identified new tricolor narrowband emitters enabling a broader color gamut than previously achievable [3].

Successful implementation of inverse molecular design requires both computational tools and experimental resources for validation. The following table details key components of the modern inverse design toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Inverse Molecular Design

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | cG-SchNet [2], MEMOS [3], GENTRL | Conditional 3D structure generation, multi-objective optimization, novel molecular design |

| Molecular Representation | Atom-type-based descriptors (ATP) [4], SMILES, 3D coordinates | Encoding molecular structures for machine learning processing |

| Property Prediction | Density Functional Theory (DFT), Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models [7] | Validating generated molecules, predicting properties without synthesis |

| Sampling Algorithms | Markov Chain Monte Carlo, Best-first search [8] | Efficient navigation of chemical space to identify optimal candidates |

| Validation Assays | cAMP assay [4], Biochemical activity screens, Optical characterization | Experimental confirmation of AI-predicted molecular properties |

| Data Resources | Chemical databases, AlphaFold protein structures [7], Experimental literature | Training data for models, benchmarking generated compounds |

The paradigm shift from traditional molecular design to inverse molecular design represents a fundamental transformation in how we approach chemical discovery. By leveraging generative AI to start from desired properties and work backward to optimal structures, researchers can now navigate chemical space with unprecedented efficiency and precision. The quantitative evidence demonstrates substantial improvements in success rates, chemical novelty, exploration scale, and development timelines across both pharmaceutical and materials science applications.

As the field continues to evolve, key challenges remain in data quality, model interpretability, and integration with experimental workflows. However, the rapid advancement of conditional generative models, multi-objective optimization frameworks, and physics-informed AI promises to further accelerate this paradigm shift. Inverse molecular design is poised to become the dominant approach for molecular discovery across therapeutic development, materials science, and beyond, ultimately enabling more targeted solutions to some of our most pressing scientific and technological challenges.

The concept of "chemical space" represents the total universe of all possible organic molecules, a domain estimated to encompass up to 10^60 theoretically feasible compounds [1]. This vastness presents a fundamental challenge for traditional scientific methods. Conventional, human-led discovery processes, which often rely on trial-and-error or incremental modifications of known structures, are intractable for navigating such an immense landscape [3] [9]. This challenge has catalyzed a paradigm shift in molecular research, moving from direct design to inverse design using generative artificial intelligence (AI). Inverse design inverts the traditional discovery protocol: it starts by defining a set of desired properties and then uses computational models to generate molecular structures that satisfy those requirements [10] [1]. This approach is now reshaping fields from drug discovery and development to the design of advanced materials, such as organic emitters for displays and metal halide perovskites for photovoltaics [3] [9] [11].

Generative AI and Inverse Design Methodologies

Generative AI provides the engine for inverse design, enabling the exploration of chemical space with unprecedented speed and scale. These models learn the complex relationships between molecular structures and their properties from existing data, allowing them to sample novel molecules from a learned conditional distribution [2].

Key Algorithmic Approaches

Several generative modeling approaches have demonstrated significant promise for molecular design, each with distinct strengths as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Generative AI Approaches for Inverse Molecular Design

| Method | Core Principle | Key Applications | Notable Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional Generative Neural Networks [2] | Autoregressively assembles 3D molecular structures atom-by-atom based on specified property conditions. | Inverse design of 3D molecular structures with targeted electronic properties. | cG-SchNet |

| Markov Molecular Sampling with Multi-Objective Optimization [3] | Uses a self-improving iterative process to traverse millions of structures, optimizing for multiple objectives simultaneously. | Precise engineering of molecules for specific functions, e.g., narrowband molecular emitters. | MEMOS framework |

| Best-First Search (BFS) [10] | A discrete heuristic search that optimizes a target property on a site-by-site basis within a molecular scaffold. | Rational functionalization of molecular scaffolds for properties like nonlinear optical (NLO) contrast. | Design of hexaphyrin-based NLO switches |

| Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNNs) [12] | Learns from crystal structures represented as graphs to predict material properties. | Discovery and optimization of stable inorganic materials with targeted optoelectronic properties. | Exploration of all-inorganic perovskites |

Experimental Protocol: Inverse Design of 3D Molecular Structures using cG-SchNet

Application Note: This protocol details the use of the conditional Generative SchNet (cG-SchNet) for the inverse design of 3D molecular structures with user-specified chemical and structural properties. It is particularly useful for discovering novel molecules in sparsely populated regions of chemical space where reference data are scarce [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Hardware: A high-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration is recommended for training and generation.

- Software: Python environment with PyTorch or TensorFlow, and the cG-SchNet codebase.

- Training Data: A dataset of 3D molecular structures (e.g., from the QM9 database) with computed values for the properties you wish to use as conditions (e.g., HOMO-LUMO gap, polarizability, atomic composition).

Procedure:

- Model Configuration:

- Define the target conditions ( \Lambda = (\lambda1, ..., \lambdak) ). These can be scalar electronic properties, molecular fingerprints, or atomic compositions.

- Configure the embedding networks for each condition type. Scalar properties are expanded on a Gaussian basis, while vector-valued properties are processed directly.

- Model Training:

- Train cG-SchNet on the dataset of molecular structures and their associated property values.

- The model learns the conditional distribution ( p(\mathbf{R}{\le n}, \mathbf{Z}{\le n} | \Lambda) ), which is the joint probability of atom positions and types given the target properties.

- Conditional Generation:

- Input the desired property values ( \Lambda ) into the trained model.

- The model autoregressively generates a new molecule: a. It predicts the type of the next atom, ( Zi ), based on the conditions and any already placed atoms. b. It then predicts the position of the new atom, ( \mathbf{r}i ), by modeling its distance to previously placed atoms, ensuring rotational and translational invariance.

- The generation process utilizes "origin" and "focus" tokens to localize atom placement and stabilize the growth of the molecule from the inside out.

- Validation:

- Validate the generated structures and their properties using quantum mechanical calculations, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), to confirm they meet the design targets.

Visualization of Workflow:

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Objective Optimization for Molecular Emitters

Application Note: The MEMOS (Markov molecular sampling) framework demonstrates how generative AI can be combined with multi-objective optimization for the inverse design of functional molecules, such as narrowband emitters for organic displays, achieving an impressive success rate of 80% as validated by DFT [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Implementation of the MEMOS generative framework.

- Validation Tools: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculation software for validation.

Procedure:

- Objective Definition: Define the multi-objective optimization targets, for example, narrow spectral emission at a specific color (wavelength) and high color purity.

- Generative Sampling: Employ Markov chain sampling to efficiently traverse the chemical space of potential molecular structures.

- Iterative Optimization: Utilize a self-improving iterative process that evaluates generated structures against the target objectives, refining the search towards optimal regions of the chemical space.

- Target Identification: Within hours, the framework can pinpoint thousands of candidate emitter molecules from a search space of millions.

- Theoretical Validation: Validate the predicted properties of top-ranking candidates using DFT calculations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful inverse design relies on a suite of computational tools and resources that form the essential "reagents" for a modern computational scientist.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for AI-Driven Inverse Design

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Inverse Design |

|---|---|---|

| cG-SchNet [2] | Generative Neural Network | Generates novel 3D molecular structures conditioned on specific target properties. |

| MEMOS Framework [3] | Generative AI & Optimization | Combines Markov sampling with multi-objective optimization to discover functional molecules. |

| Best-First Search (BFS) [10] | Heuristic Search Algorithm | Optimizes the functionalization of a known molecular scaffold for a target property. |

| Crystal Graph CNN (CGCNN) [12] | Graph Neural Network | Serves as a surrogate model to predict material properties (e.g., stability, bandgap) for rapid screening. |

| Chemical Databases (e.g., PubChem, DrugBank) [9] | Virtual Chemical Space | Provides open-access repositories of known molecules and their properties for model training and validation. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [3] [12] | Quantum Mechanical Method | Provides high-fidelity validation of AI-generated molecules' properties, such as stability and electronic structure. |

Advanced Applications and Workflow Integration

The power of inverse design is fully realized when integrated into a broader, automated discovery workflow. This is exemplified in the field of materials science, where generative models and surrogate predictors are chained together to rapidly screen vast compositional spaces.

Visualization of an Integrated DFT/ML Discovery Pipeline:

Application Example: This workflow has been successfully deployed for the discovery of all-inorganic perovskites for photovoltaics [12]. Researchers used DFT to create a initial dataset of 3,159 perovskite structures. A Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) was then trained on this data to predict key properties like decomposition energy and bandgap. The trained model was subsequently used to exhaustively explore over 41,400 candidate compositions and their configurations, identifying 10 particularly stable compounds with optimal bandgaps for solar cell applications, which were finally validated with higher-fidelity hybrid-DFT calculations. This approach highlights the critical advantage of AI: the ability to explore not just composition, but also atomic configuration, to find the globally optimal structure.

The challenge of navigating the近乎无限的化学空间(10^60 molecules)is no longer insurmountable. The advent of generative AI and inverse design methodologies has initiated a new era of molecular discovery. Frameworks like cG-SchNet, MEMOS, and CGCNNs enable researchers to move beyond slow, serendipitous discovery to a targeted, rational, and accelerated design process. By starting with the desired functionality, these AI-powered tools efficiently generate candidate structures that meet complex multi-objective criteria, as validated by high-fidelity theoretical methods. As these technologies continue to mature, focusing on sustainability [13] [14], data efficiency, and model interpretability, they promise to dramatically accelerate the development of new drugs, materials, and technologies, fundamentally reshaping the scientific landscape.

The field of molecular science is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from a paradigm of passive computational analysis to one of active AI-driven creation. Traditional approaches in drug discovery and materials science have largely relied on forward design principles: researchers modify existing compounds and then computationally or experimentally test their properties in a iterative, often time-consuming cycle. Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) is revolutionizing this process through inverse design, a methodology where desired properties are specified first, and AI algorithms then generate molecular structures satisfying those constraints [2] [15]. This shift is accelerating the exploration of the vast chemical space, estimated to contain up to 10^60 feasible compounds, a scale that makes traditional screening methods intractable [1].

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing generative AI in inverse molecular design. It is structured to equip researchers and drug development professionals with both the theoretical foundation and practical methodologies needed to leverage these technologies, framed within the broader thesis that generative AI represents a move from passive prediction to active creation in molecular science.

Generative AI Architectures for Molecular Design

Generative AI encompasses a range of model architectures, each with distinct strengths for molecular design tasks. The following table summarizes the primary architectures and their applications in molecular science.

Table 1: Key Generative AI Architectures in Molecular Design

| Architecture | Core Principle | Molecular Representation | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [16] | Encodes inputs into a latent space and decodes to generate new data. | SMILES strings, Molecular graphs | Learning smooth latent spaces for molecular interpolation and property optimization. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [16] | A generator and discriminator network are trained adversarially. | SMILES strings, 2D/3D structures | Generating novel molecular structures with desired chemical properties. |

| Autoregressive Models (e.g., RNNs, Transformers) [15] | Generates sequences token-by-step, with each step conditioned on previous outputs. | SMILES strings, SELFIES | De novo molecular design, scaffold hopping, R-group replacement. |

| Diffusion Models [17] [18] | Generates data by progressively denoising a random initial state. | 3D atomic coordinates, Crystalline structures | Generating stable 3D molecular geometries and inorganic crystals. |

Conditional Generation for Targeted Design

A critical advancement is the development of conditional generative models. These models learn the probability distribution of molecular structures conditioned on specific properties, allowing for targeted sampling. For instance, Conditional G-SchNet (cG-SchNet) learns the distribution ( p(\mathbf{R}{\le n}, \mathbf{Z}{\le n} | \mathbf{\Lambda}) ), where (\mathbf{R}) and (\mathbf{Z}) represent atom positions and types, and (\mathbf{\Lambda}) represents target conditions like electronic properties or composition [2]. This enables the generation of 3D molecular structures with specified motifs or electronic properties, even in sparsely populated regions of chemical space.

Quantitative Performance of Generative AI Models

The efficacy of generative AI models is measured by their ability to produce valid, unique, novel, and stable structures that meet target properties. The table below summarizes quantitative benchmarks from recent state-of-the-art models.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Generative AI Models in Molecular Design

| Model / Framework | Key Performance Metrics | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|

| MatterGen [18] | 78% of generated structures are stable (<0.1 eV/atom from convex hull). 61% are new, previously unknown structures. Over 10x closer to DFT energy minimum than previous models. | Inorganic Materials Design |

| MEMOS [3] | Up to 80% success rate in identifying target narrowband molecular emitters, as validated by DFT calculations. | Organic Molecular Emitters |

| cG-SchNet [2] | Demonstrated targeted sampling of novel molecules with specified structural motifs and multiple joint electronic properties beyond the training data regime. | Small Molecule Drug Design |

| REINVENT 4 [15] | Successfully used in production for de novo design, molecule optimization, and proposing realistic 3D molecules in docking benchmarks. | Small Molecule Drug Discovery |

Application Notes and Detailed Protocols

Protocol 1: Conditional 3D Molecule Generation with cG-SchNet

This protocol details the process for generating 3D molecular structures with target properties using a conditional generative neural network.

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for cG-SchNet Implementation

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| cG-SchNet Architecture | The core deep learning model that autoregressively places atoms in 3D space conditioned on property inputs [2]. |

| Condition Embedder | A sub-network that embeds scalar, vector, or compositional property targets into a latent vector for conditioning. |

| Origin & Focus Tokens | Auxiliary tokens that stabilize generation by marking the molecular center and localizing atom placement [2]. |

| Training Dataset | A curated set of molecular structures with associated computed properties (e.g., QM9, MD-17). |

| Property Predictor | Pre-trained model (e.g., for HOMO-LUMO gap, polarizability) to validate generated molecules if ground truth is unknown. |

4.1.2 Workflow Diagram

4.1.3 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Condition Specification: Define the target properties, ( \Lambda = (\lambda1, \ldots, \lambdak) ). These can be scalar electronic properties (e.g., polarizability), vector-valued fingerprints, or atomic compositions.

- Condition Embedding: Process each condition through the embedding network. Scalar properties are expanded on a Gaussian basis, while compositional data are embedded via weighted atom type embeddings. The embedded vectors are concatenated and processed by a fully connected layer to form a unified conditioning vector [2].

- Structure Initialization: Initialize the generation process by placing the origin token at (0,0,0). This token marks the center of mass and guides outward growth.

- Autoregressive Generation: For each step ( i ) until generation is complete: a. Focus Token Assignment: Randomly assign the focus token to an already placed atom ( j ). This localizes the subsequent position prediction. b. Atom Type Prediction: The model computes a probability distribution over the next atom type: ( p(Zi | \mathbf{R}{\le i-1}, \mathbf{Z}{\le i-1}, \Lambda) ). Sample from this distribution to select ( Zi ) [2]. c. Atom Position Prediction: Given the new atom type, the model predicts distributions over distances to all existing atoms: ( p(r{ij} | \mathbf{R}{\le i-1}, \mathbf{Z}{\le i}, \Lambda) ). The full 3D position distribution is the product of these distance distributions, ensuring rotational and translational equivariance [2]. d. Position Sampling and Placement: Sample a position ( \mathbf{r}i ) and place the new atom of type ( Z_i ).

- Termination: The generation is complete when the model produces a termination token. The final output is a fully specified 3D molecular structure.

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Molecule Optimization with REINVENT 4

This protocol outlines the use of REINVENT 4's reinforcement learning (RL) framework for optimizing molecules against multiple objective functions, such as binding affinity, solubility, and synthetic accessibility.

4.2.1 Workflow Diagram

4.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Prior Model Selection: Start with a "prior" agent, a generative model (e.g., RNN or Transformer) pre-trained on a large corpus of SMILES strings to understand general chemical rules and syntax [15]. This model serves as the initial policy.

- Reward Function Definition: Design a composite reward function ( R(m) ) that encapsulates all desired objectives for a generated molecule ( m ). For example:

- ( R(m) = w1 \cdot \text{ActivityPred}(m) + w2 \cdot \text{SolubilityPred}(m) + w3 \cdot \text{SAscore}(m) )

- Weights ( wi ) balance the importance of each objective. The scoring subsystem can incorporate external software and predictive models via a plugin mechanism [15].

- Agent Sampling: Use the current agent to generate a batch of molecules. The agent produces molecules auto-regressively according to its internal policy [15].

- Reinforcement Learning Update: Adjust the parameters of the agent to increase the likelihood of generating molecules with high reward scores. This is typically done using a policy gradient method like Augmented Likelihood or Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). The loss function often includes a component to keep the agent close to the prior, preventing over-optimization toward unrealistic chemicals [15] [16].

- Iteration and Convergence: Repeat steps 3 and 4. The agent's policy is progressively refined over many iterations. Training stops when the generated molecules consistently meet the target objectives or performance plateaus.

Protocol 3: Inverse Design of Inorganic Materials with MatterGen

This protocol describes the use of a diffusion model for the inverse design of stable, novel inorganic crystals with targeted properties.

4.3.1 Workflow Diagram

4.3.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Base Model Pretraining: The MatterGen model is first pretrained on a large and diverse dataset of stable inorganic crystals (e.g., Alex-MP-20 with ~600k structures) [18]. The diffusion process is customized for crystals, corrupting and denoising atom types ((A)), fractional coordinates ((X)), and the periodic lattice ((L)) in a symmetry-respecting manner.

- Adapter-Based Fine-Tuning: For a specific inverse design task (e.g., targeting a high magnetic density), the base model is fine-tuned on a smaller dataset labeled with the target property. This is done efficiently using adapter modules—small, tunable components injected into the base model—rather than retraining the entire network [18].

- Conditional Generation: To generate a material, the reverse diffusion process is initiated from noise. The generation is steered towards the desired condition (y) (e.g., "magnetic density > X") using classifier-free guidance, which amplifies the direction in latent space associated with the target [18].

- Structure Output: The output of the denoising process is a full crystal specification, including its unit cell and atomic positions.

- Validation: The stability and properties of the generated crystal must be validated using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. MatterGen generates structures that are typically very close to their local energy minimum, making DFT relaxation efficient [18]. Successful synthesis and experimental validation, as demonstrated in one proof-of-concept, provide the ultimate confirmation [18].

Generative AI has fundamentally redefined the process of molecular innovation, transitioning the role of computation from a supportive tool for prediction to a core engine for active creation. Frameworks like cG-SchNet, REINVENT 4, and MatterGen demonstrate the practical implementation of inverse design, enabling researchers to directly generate stable, novel, and functional molecules and materials from a set of desired properties. The detailed application notes and protocols provided herein serve as a roadmap for scientists to integrate these powerful methodologies into their research pipelines. As these models continue to evolve through advancements in architecture, optimization strategies, and integration with automated laboratory systems, they promise to significantly accelerate the discovery of new therapeutics, materials, and chemicals, ultimately supercharging the capabilities of researchers across the molecular sciences.

The design of novel molecules is a fundamental challenge in drug discovery and materials science. Traditional approaches, which often rely on costly and inefficient high-throughput screening, are limited in their ability to explore the vast chemical space, estimated to contain up to 10^60 theoretically feasible compounds [19] [1]. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) offers a paradigm shift by enabling de novo molecular creation guided by data-driven optimization, a process known as inverse design [19] [15]. Unlike forward design, which modifies existing compounds until they satisfy specific criteria, inverse design first states the properties a molecule must possess and then informs an algorithm on how to create it [15]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the key generative architectures—Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Transformers, and Diffusion Models—that are catalyzing this transformation in molecular science.

Core Generative Architectures: Mechanisms and Molecular Applications

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

Mechanism: Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are probabilistic generative models that learn to compress data into a latent (hidden) representation and then reconstruct it. Introduced by Kingma and Welling in 2013, VAEs consist of an encoder and a decoder [20]. The encoder maps input data to a latent space, learning a probability distribution (typically Gaussian) characterized by a mean and standard deviation. The decoder then takes a sample from this latent distribution and reconstructs it back into the original data format. The model is trained by minimizing two loss functions: a reconstruction loss, which ensures the decoder can accurately reconstruct the input, and a KL-divergence loss, which encourages the latent distributions to be close to a standard normal distribution, facilitating smooth sampling and interpolation [20].

Molecular Application: In molecular design, the input data is typically a molecular representation, such as a SMILES string or a graph. Gómez-Bombarelli et al. demonstrated how VAEs could learn continuous representations of molecules, facilitating the generation and optimization of novel molecular entities within unexplored chemical spaces [21]. The probabilistic nature and smooth latent space of VAEs make them particularly useful for tasks like molecular generation and optimization [19] [15].

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Mechanism: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), introduced by Ian Goodfellow and colleagues in 2014, consist of two neural networks, a generator and a discriminator, trained in a competitive setting [20]. The generator takes random noise as input and tries to produce data that resembles the real data distribution. The discriminator acts as a binary classifier, evaluating whether the data it receives is real (from the dataset) or fake (produced by the generator). The two networks are trained simultaneously: the generator improves by learning to create more convincing fakes, while the discriminator improves at distinguishing real from fake. This adversarial process continues until the generator produces outputs that the discriminator cannot reliably tell apart from real data [20].

Molecular Application: GANs are known for generating high-fidelity, realistic samples. In molecular design, they have been applied to generate molecular structures, including for tasks like data augmentation and style transfer [20] [19]. However, their training can be unstable and prone to mode collapse, where the generator produces limited varieties of outputs [20].

Transformers

Mechanism: Transformers are a deep learning architecture that relies on a mechanism called self-attention, allowing each token in a sequence to dynamically focus on other tokens. Introduced by Vaswani et al. in 2017, the architecture consists of layers of multi-head self-attention, feedforward networks, layer normalization, and residual connections. This design enables transformers to model long-range dependencies efficiently and in parallel, unlike sequential models like RNNs [20].

Molecular Application: In generative molecular design, transformers are often trained autoregressively. They predict the next token in a sequence, making them ideal for generating SMILES strings [15]. For example, the REINVENT 4 framework utilizes transformer architectures to drive molecule generation, capturing the probability of generating tokens in an auto-regressive manner [15]. The KPGT framework also uses a graph transformer architecture with a knowledge-guided pre-training strategy to produce robust molecular representations for drug discovery [21].

Diffusion Models

Mechanism: Diffusion Models (DMs) generate data through a two-step process inspired by non-equilibrium thermodynamics [20] [22]. In the forward process (diffusion), noise is progressively added to real data over many steps until it becomes nearly pure Gaussian noise. In the reverse process (denoising), a neural network is trained to reverse this diffusion process, step-by-step, transforming noise back into coherent data. During generation, the model starts with random noise and iteratively denoises it to produce realistic samples [20]. For 3D molecular generation, equivariant diffusion models ensure that the generated structures are equivariant to rotations and translations (E(3)-equivariance), meaning the model's outputs transform consistently with its inputs, which is critical for modeling 3D molecular geometry [23] [22].

Molecular Application: Diffusion models have shown remarkable success in generating 3D molecular structures. They are used for conformation generation and directly generating molecules with specific geometric properties or high binding affinity for a target protein [22]. For instance, DiffGui is a target-conditioned E(3)-equivariant diffusion model that integrates bond diffusion and property guidance to generate novel 3D molecules with high binding affinity and desirable drug-like properties inside given protein pockets [23].

Comparative Analysis of Architectural Performance

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of each generative architecture in the context of molecular design.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Generative Architectures for Molecular Design

| Architecture | Core Mechanism | Key Strengths | Key Weaknesses | Exemplary Molecular Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [20] | Encoder-Decoder with probabilistic latent space | Stable training; Smooth, interpretable latent space; Effective for interpolation & exploration | Can produce blurry or less detailed outputs; May struggle with complex data distributions | Learning continuous molecular representations [21]; Molecular generation & optimization [19] [15] |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [20] | Adversarial training between Generator & Discriminator | High-fidelity, realistic outputs; Flexible architecture | Unstable training dynamics; Prone to mode collapse | Generating realistic molecular structures [19]; Data augmentation [20] |

| Transformers [20] [15] | Self-attention for sequence modeling | Captures long-range dependencies; Highly parallelizable; Versatile across data types | Requires large datasets & computational resources | Auto-regressive generation of SMILES strings [15]; Knowledge-guided pre-training (KPGT) [21] |

| Diffusion Models [20] [23] [22] | Iterative denoising from noise | High-quality, diverse outputs; Stable training; Strong in 3D & equivariant generation | Slow inference due to iterative sampling; Computationally intensive | 3D molecule & conformation generation [22]; Target-aware design (DiffGui) [23] |

A unified benchmarking of diffusion models on datasets like QM9, GEOM-Drugs, and CrossDocked2020 reveals performance variations. Metrics such as validity (the proportion of generated molecules that are chemically valid), uniqueness, novelty, and molecular stability are commonly used [22]. For 3D target-aware generation, metrics also include the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of generated geometries and quantitative estimates of drug-likeness (QED) and binding affinity (Vina Score) [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Target-Aware 3D Molecular Generation with Equivariant Diffusion

This protocol is adapted from the DiffGui framework for generating 3D molecules within a protein binding pocket [23].

1. Objective: To generate novel, valid, and synthetically accessible 3D ligand molecules with high binding affinity and desirable drug-like properties for a specific protein target.

2. Materials and Inputs:

- Protein Structure: A 3D structure of the target protein in PDB format, with a defined binding pocket.

- Reference Ligands: A set of known ligands for the target (optional, for validation and comparison).

- Software & Libraries: DiffGui codebase (or equivalent equivariant diffusion framework), PyTorch, RDKit, OpenBabel, and a molecular docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina) for affinity estimation.

3. Procedure:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Prepare the protein structure file, ensuring hydrogen atoms are added.

- Define the centroid and dimensions of the binding pocket.

- If using a pre-trained model, ensure the input data format matches the model's requirements.

Step 2: Model Configuration

- Configure the diffusion process parameters: number of timesteps (T), noise schedules for atoms and bonds.

- Set up the E(3)-equivariant Graph Neural Network (GNN) as the denoising network. This network should update representations for both atoms and bonds.

- Enable property guidance by specifying the target properties (e.g., Vina Score, QED, Synthetic Accessibility (SA), LogP) and their respective weights in the guidance function.

Step 3: Sampling and Generation

- Initialize the ligand generation process by sampling a pure noise distribution within the defined pocket space.

- Run the reverse diffusion process. The equivariant GNN iteratively denoises the atom positions (coordinates) and atom/bond types (categorical features).

- The bond diffusion module explicitly models the interdependencies between atoms and bonds during this process to ensure chemical validity.

- Property guidance is applied at each denoising step to steer the generation towards molecules with the desired attributes.

Step 4: Post-processing and Validation

- Assemble the generated atoms and bonds into complete molecules.

- Validate the chemical correctness of generated molecules using RDKit (e.g., RDKit validity).

- Filter molecules based on structural feasibility and the absence of strained rings or unrealistic geometries.

- Evaluate key metrics: binding affinity via docking, drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility (SA), and novelty compared to the training set.

4. Output: A set of novel 3D molecular structures in SDF or PDB format, optimized for the target protein pocket with predicted high affinity and drug-like properties.

Protocol: Molecular Optimization using Reinforcement Learning (RL) with Transformer Agents

This protocol is based on the REINVENT 4 framework for optimizing lead compounds [15].

1. Objective: To optimize a starting molecule (scaffold) by improving specific properties (e.g., potency, solubility) while maintaining its core structural features.

2. Materials and Inputs:

- Prior Agent: A pre-trained transformer or RNN model on a large corpus of SMILES strings (extensive general chemical knowledge).

- Target Molecule: The SMILES string of the starting molecule to be optimized.

- Scoring Function: A function that calculates a score based on the desired molecular properties (e.g., a composite score of LogP, QED, and a predicted activity from a QSAR model).

3. Procedure:

Step 1: Agent Initialization

- The prior agent serves as the foundation model. It can be used directly or fine-tuned on a set of molecules similar to the desired chemical space.

Step 2: Reinforcement Learning Loop

- The agent (e.g., a transformer) generates a batch of molecules auto-regressively, token-by-token.

- Each generated SMILES string is scored by the scoring function.

- The agent's likelihood of generating the molecules is adjusted using the REINVENT loss function, which combines the prior likelihood and the reinforcement learning reward signal. This increases the probability of generating high-scoring molecules and decreases the probability of low-scoring ones in subsequent rounds.

- This loop (generate -> score -> update) is repeated for a specified number of iterations.

Step 3: Sampling and Analysis

- Sample the optimized agent to generate a focused library of proposed molecules.

- Analyze the generated molecules for validity, uniqueness, and improvement in the target properties compared to the starting molecule.

4. Output: A set of optimized molecular structures (as SMILES strings) with enhanced property profiles.

Visualization of Workflows and Architectures

Diagram: Equivariant Diffusion for 3D Molecular Generation

The following diagram illustrates the forward and reverse diffusion process for generating 3D molecules, as implemented in models like DiffGui [23].

Diagram 1: 3D Equivariant Diffusion Workflow. This illustrates the noising (forward) and denoising (reverse) process for generating a 3D ligand within a protein pocket, conditioned on properties.

Diagram: Reinforcement Learning for Molecular Optimization

This diagram outlines the closed-loop DMTA (Design-Make-Test-Analyze) cycle used in frameworks like REINVENT for molecular optimization [15].

Diagram 2: Reinforcement Learning Cycle. This shows the iterative process of generating molecules, scoring their properties, and updating the generative agent to improve future designs.

Table 2: Key Software Tools and Resources for Generative Molecular Design

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevant Architecture(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| REINVENT 4 [15] | Software Framework | Open-source platform for molecular generation & optimization using RNNs/Transformers and RL. | Transformers, RNNs |

| DiffGui [23] | Algorithmic Model | Target-aware 3D molecular generation model using bond & property-guided equivariant diffusion. | Diffusion Models |

| OpenBabel [23] | Chemistry Toolkit | Handles chemical file format conversion and molecular manipulation; often used for post-processing. | All |

| RDKit [23] | Cheminformatics Library | Provides functions for molecular validation, descriptor calculation (QED, LogP), and fingerprinting. | All |

| AlphaFold [23] | Protein Structure DB | Provides predicted 3D protein structures for targets without experimental structures. | Target-aware Models |

| QM9, GEOM-Drugs, CrossDocked2020 [22] | Benchmark Datasets | Curated datasets of 3D molecular structures and protein-ligand complexes for training and evaluation. | All (esp. 3D & Diffusion) |

Inverse molecular design represents a paradigm shift in materials science and drug discovery. Traditional design relies on explicit human knowledge to navigate chemical space, a vast domain estimated to contain up to 10^60 feasible compounds [1]. In contrast, generative artificial intelligence enables inverse design by starting with desired properties and automatically identifying molecules that satisfy them [1]. This approach operates through a "design-without-understanding" mechanism—not due to a lack of capability, but because AI systems learn implicit chemical rules directly from data, discovering complex patterns that may not be explicitly encoded by human experts. This Application Note details the protocols and methodologies for implementing this approach, with a focus on generative AI for molecular design.

Theoretical Foundation: How AI Learns Chemical Grammar

The Data-Driven Paradigm

Deep learning models learn chemistry through representation learning, performing multiple nonlinear transformations on raw molecular data to extract hierarchical patterns [24]. Unlike hand-encoded rules-based systems that require human intervention to define chemical constraints, generative models independently learn to produce molecules with specific properties by identifying structural patterns such as valency rules, reactive groups, molecular conformations, and hydrogen bond donors/acceptors [24]. This capability enables exploration of regions in chemical space that might be counter-intuitive to human designers.

Molecular Representations as Language

Chemical language models typically use one-dimensional string representations of molecules as inputs, treating molecular generation as a sequence modeling problem [24]:

- SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System): A prevalent ASCII character string representation that encodes molecular structure using tokens based on chemical structure [24]

- Molecular Graphs: Represent molecules as nodes (atoms) and edges (bonds) in graph structures, capturing topological information [24]

- IUPAC Nomenclature: Systematic naming conventions that can be processed by language models [24]

These representations enable AI systems to learn the "syntax" and "grammar" of chemistry much as large language models learn human language.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing the MEMOS Framework for Molecular Emitters

The MEMOS (Markov molecular sampling with multi-objective optimization) framework demonstrates the inverse design paradigm for developing narrowband molecular emitters for organic displays [3] [25].

Materials and Computational Requirements

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- Software: Density functional theory (DFT) calculation packages for validation

- Data: Initial dataset of known molecular emitters with spectral properties

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Initialization: Define desired target properties (emission color, bandwidth, quantum efficiency)

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo Sampling: Deploy stochastic sampling to explore chemical space:

- Set transition probabilities based on molecular similarity metrics

- Implement metropolis criterion for state acceptance

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Simultaneously optimize for multiple target properties:

- Define fitness function combining spectral properties and synthetic accessibility

- Apply Pareto optimization to identify non-dominated solutions

- Self-Improving Iteration: Execute iterative refinement cycles:

- Generate candidate structures

- Evaluate against objective functions

- Incorporate successful candidates into training set for subsequent iterations

- Validation: Confirm predicted properties using DFT calculations with specified exchange-correlation functionals

Key Parameters

- Exploration Rate: Balance between exploitation of known scaffolds and exploration of novel chemotypes

- Population Size: Maintain diversity while managing computational cost

- Termination Criteria: Convergence threshold or maximum number of generations

Protocol 2: Privacy-Aware Retrosynthesis with CKIF

The Chemical Knowledge-Informed Framework (CKIF) enables collaborative model training without sharing proprietary reaction data [26].

System Architecture

- Federated Learning Setup: Distributed clients with local reaction datasets

- Central Coordinator: Manages aggregation without accessing raw data

- Encrypted Communication Channels: Secure parameter exchange

Implementation Steps

- Local Model Initialization: Each participant trains initial model on proprietary data

- Chemical Knowledge-Informed Weighting (CKIW):

- Compute molecular fingerprint similarities (ECFP, MACCS keys) between predicted and ground truth reactants

- Generate adaptive weights quantifying model relevance

- Federated Aggregation:

- Transmit model parameters to coordinator

- Perform weighted averaging based on CKIW assessments

- Distribute updated models to participants

- Personalized Model Refinement: Each client fine-tunes aggregated model on local data

- Iterative Improvement: Repeat for multiple communication rounds (typically 50-100)

Evaluation Metrics

- Top-K Accuracy: Proportion of ground truth reactants in top-K predictions

- Maximal Fragment Accuracy: Relaxed metric focusing on main compound transformations

- RoundTrip Accuracy: Verification that predicted reactants synthesize target product using forward synthesis model

Diagram 1: CKIF federated learning workflow for privacy-preserving retrosynthesis. Clients share only model parameters, not raw chemical data [26].

Performance Metrics and Validation

Quantitative Performance of Generative AI Models

Table 1: Performance benchmarks of AI-driven molecular design platforms

| Platform/Framework | Application Domain | Success Rate | Throughput | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEMOS [3] | Narrowband molecular emitters | Up to 80% | Millions of structures in hours | DFT calculations |

| CKIF [26] | Retrosynthesis prediction | Outperforms centralized training | Distributed across multiple clients | Top-K accuracy, RoundTrip validation |

| DeepVS [9] | Molecular docking | Exceptional performance with 95,000 decoys | Not specified | Receptor-ligand docking benchmarks |

| AI-QSAR Models [9] | ADMET prediction | Significant improvement over traditional QSAR | Large-scale dataset processing | Clinical trial outcome correlation |

Model Architecture Comparison

Table 2: Deep learning architectures for molecular generation

| Architecture | Strengths | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformers [24] | Captures long-range dependencies, parallel processing | High computational requirements, data hunger | Sequence-based molecular generation |

| RNNs [24] | Handles sequential data effectively, memory capability | Vanishing gradient problem, slower training | SMILES string generation |

| GANs [24] | High-quality sample generation, adversarial training | Training instability, mode collapse | De novo molecule design |

| VAEs [24] [1] | Continuous latent space, stable training | Blurry outputs, simpler distributions | Molecular optimization |

| Diffusion Models [1] | State-of-the-art sample quality, training stability | Computationally intensive sampling | High-fidelity molecule generation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key resources for implementing AI-driven molecular design

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representations | SMILES, SELFIES, Molecular Graphs [24] | Encode chemical structure for AI processing | Standardized formats ensure interoperability |

| Benchmarking Platforms | MOSES, GuacaMol [24] | Evaluate quality, diversity, and fidelity of generated molecules | Enables comparative analysis between models |

| Privacy-Preserving Frameworks | CKIF [26] | Enable collaborative training without sharing proprietary data | Addresses IP protection concerns |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, ChemBank, DrugBank [9] | Provide training data and reference structures | Varying levels of accessibility and licensing |

| Validation Tools | DFT calculations, MD simulations [3] | Verify predicted molecular properties | Computational resource intensive |

| Architecture Libraries | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Transformers | Implement and train deep learning models | Open-source availability with community support |

Advanced Implementation: Workflow Visualization

Diagram 2: End-to-end workflow for generative AI molecular design, highlighting the iterative nature of inverse design [3] [1].

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Implementation Challenges

- Data Quality and Quantity: Ensure sufficient, well-curated training data with minimal experimental error [9]

- Model Validation: Always complement computational predictions with experimental validation (e.g., DFT calculations, synthesis testing) [3]

- Chemical Reality: Implement rules or constraints to ensure generated molecules are synthetically accessible and stable [24]

- Evaluation Rigor: Use multiple metrics (validity, novelty, uniqueness, diversity) to comprehensively assess model performance [24]

Performance Optimization Strategies

- Transfer Learning: Leverage pre-trained models on large chemical datasets before fine-tuning on specific domains [24]

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Balance competing properties (e.g., potency vs. solubility) using Pareto optimization techniques [3]

- Ensemble Methods: Combine multiple architectures or models to improve robustness and performance [24]

- Active Learning: Intelligently select which candidates to validate experimentally to maximize information gain

The "design-without-understanding" paradigm represents a fundamental shift in molecular design, where AI systems learn implicit chemical rules directly from data rather than relying exclusively on human expertise. The protocols and frameworks outlined in this Application Note provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these approaches, enabling accelerated discovery of novel materials and therapeutic compounds with tailored properties. As these technologies continue to mature, they hold the potential to dramatically reduce the time and cost associated with traditional discovery workflows while exploring regions of chemical space that might otherwise remain inaccessible.

Generative AI in Action: Architectures, Models, and Real-World Applications

Inverse molecular design represents a paradigm shift in materials science and drug discovery. Unlike traditional methods that predict properties from a known molecular structure, inverse design starts with a set of desired properties and aims to engineer molecules that exhibit those characteristics. This approach is crucial for addressing challenges in various applications, ranging from drug design and catalysis to energy materials. The core challenge lies in the vastness of chemical compound space, which makes exhaustive exploration infeasible. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, enabling researchers to efficiently navigate this complex space and discover novel molecules with tailored functionalities. These AI models learn the underlying distribution of chemical structures and properties from existing data, allowing them to sample new molecules with desired characteristics, thus dramatically accelerating the discovery process [2].

This application note provides a detailed technical examination of three dominant architectures in generative AI for inverse molecular design: cG-SchNet, MEMOS, and Equivariant Diffusion Models (EDM). Each framework employs distinct strategies for molecular generation and optimization, making them suitable for different applications and research objectives. We present structured comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and implementation guidelines to empower researchers in selecting and applying these advanced tools effectively.

Architectural Framework Deep Dive

cG-SchNet: Conditional Generative Neural Networks for 3D Molecular Structures

cG-SchNet is an autoregressive deep neural network that generates diverse molecules by sequentially placing atoms in Euclidean space. The model learns conditional distributions based on structural or chemical properties, enabling sampling of 3D molecular structures with specified characteristics. A key innovation of cG-SchNet is its factorization of the conditional distribution of molecules. The joint distribution of atom positions (R≤n) and atom types (Z≤n) conditioned on target properties (Λ) is factorized as follows:

$$ p({{{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}}{\le n},{{{{{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}}}}{\le n}| {{{{{\mathbf{\Lambda}}}}}})=\mathop{\prod }\limits{i=1}^{n}p\left({{{{{{{{\bf{r}}}}}}}}}{i},{Z}{i}| {{{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}}}}}_{\le i-1},{{{{{\mathbf{\Lambda}}}}}}\right) $$

This joint probability is further decomposed into the probability of the next atom type and the probability of the next position given that type:

$$ p \left({{{{{{{{\bf{r}}}}}}}}}{i},{Z}{i}| {{{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{\mathbf{\Lambda}}}}}}\right)=p({Z}{i}| {{{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{\mathbf{\Lambda}}}}}})\,p({{{{{{{{\bf{r}}}}}}}}}{i}| {{{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}}}}}{\le i},{{{{{\mathbf{\Lambda}}}}}}) $$

To guarantee equivariance with respect to translation and rotation, the model approximates the distribution over absolute positions from distributions over distances to already placed atoms:

$$ p({{{{{{{{\bf{r}}}}}}}}}{i}| {{{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}}}}}{\le i},{{{{{\mathbf{\Lambda}}}}}})=\frac{1}{\alpha }\mathop{\prod }\limits{j=1}^{i-1}p({r}{ij}| {{{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}}}{\le i-1},{{{{{{{{\bf{Z}}}}}}}}}_{\le i},{{{{{\mathbf{\Lambda}}}}}}) $$

where α is the normalization constant and rij = ∣∣ri − rj∣∣ is the distance between the new atom i and previously placed atom j [2].

The architecture employs two auxiliary tokens to stabilize generation: an origin token that marks the molecular center of mass and guides outward growth, and a focus token that localizes position predictions to ensure scalability and break symmetries in partial structures. This approach is particularly valuable because it's agnostic to chemical bonding, making it suitable for systems with ambiguous bonding like transition metal complexes or conjugated systems [2].

Table 1: Key Architectural Components of cG-SchNet

| Component | Function | Technical Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Conditioning Mechanism | Embeds target properties into generation process | Each condition embedded into latent vector space, concatenated, processed through fully connected layer |

| Autoregressive Generation | Sequentially builds molecular structure | Places atoms one-by-one, with each new atom dependent on all previous atoms |

| Equivariance Handling | Ensures invariance to rotation/translation | Approximates absolute positions from pairwise distance distributions |

| Auxiliary Tokens | Stabilizes generation process | Origin token (center of mass), Focus token (localizes next position prediction) |

| Property Conditioning | Enables targeted molecular generation | Supports scalar electronic properties, vector-valued fingerprints, atomic composition |

MEMOS: Generative AI with Multi-Objective Optimization

MEMOS is a cutting-edge molecular generation framework that harnesses Markov molecular sampling techniques alongside multi-objective optimization for inverse design of molecules. Specifically developed for designing narrowband molecular emitters for organic displays, MEMOS enables precise engineering of molecules capable of emitting narrow spectral bands at desired colors. The framework employs a self-improving iterative process that can efficiently traverse millions of molecular structures within hours, identifying thousands of target emitters with remarkable success rates up to 80% as validated by density functional theory calculations [3] [25].

The key innovation of MEMOS lies in its integration of efficient Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling with multi-objective optimization. This combination allows the framework to explore a nearly boundless chemical space while maintaining focus on specific target properties. MEMOS has demonstrated particular effectiveness in retrieving well-documented multiple resonance cores from experimental literature and achieving broader color gamuts with newly identified tricolor narrowband emitters [25]. This capability addresses a critical challenge in organic display technology - the development of next-generation molecular emitters capable of delivering an extensive color gamut with unparalleled color purity, which traditionally relied on time-consuming and costly trial-and-error methods [3].

EDM: Equivariant Diffusion Models

Equivariant Diffusion Models (EDM) represent another powerful approach to inverse molecular design that leverages recent advances in diffusion models. While detailed architectural information from the search results is limited, these models combine equivariant graph neural networks with diffusion processes to generate molecular structures conditioned on desired properties [27]. The fundamental principle involves a forward process that gradually adds noise to molecular structures, and a reverse process that learns to reconstruct molecules from noise while respecting physical symmetries.

The "guided diffusion" approach conditions the generation process on target properties, enabling the design of novel molecules with desired characteristics. The method has demonstrated capability in generating new molecules with desired properties and, in some cases, even discovering molecules that outperform those present in the original training dataset of 500,000 molecules [27]. This approach benefits from the inherent stability of diffusion models and their ability to generate diverse, high-quality samples.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Analysis

Each architecture demonstrates distinct performance characteristics across various inverse design tasks. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Inverse Molecular Design Frameworks

| Framework | Primary Application Domain | Success Rate/Performance | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| cG-SchNet | General molecular design with focus on 3D structure-dependent properties | Demonstrated capability for generating molecules with specified motifs, composition, and multiple electronic properties | Agnostic to chemical bonding; enables targeted sampling even in sparse data regions |

| MEMOS | Narrowband molecular emitters for display technology | Up to 80% success rate (DFT-validated); traverses millions of structures in hours | High efficiency in targeting specific optical properties; self-improving iterative process |

| EDM | General molecular design tasks | Capable of discovering molecules superior to training set examples | Benefits from diffusion model stability; equivariant to physical symmetries |

cG-SchNet has demonstrated particular strength in generating molecules with specified structural motifs and jointly targeting multiple electronic properties beyond the training regime. Its conditioning approach allows flexible targeting of different properties without retraining, enabling efficient exploration of sparsely populated regions in chemical space that are hardly accessible with unconditional models [2].

MEMOS shows exceptional performance in its specialized domain of narrowband emitters, achieving an impressive success rate that significantly accelerates the design pipeline for organic optoelectronics. The framework's ability to rapidly explore vast chemical spaces and identify target molecules with high precision addresses a critical bottleneck in materials discovery for display technologies [3] [25].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

cG-SchNet Implementation Protocol

Training Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Utilize the QM9 dataset or custom molecular datasets with associated properties. QM9 contains approximately 130,000 small organic molecules with up to nine heavy atoms (C, N, O, F) along with various quantum chemical properties [28].

- Conditioning Specification: Define target properties in a JSON configuration file. Supported conditions include scalar electronic properties, molecular fingerprints, and atomic compositions.

- Model Configuration: Set network parameters (feature dimensions, interaction layers). Recommended baseline: 128 features and 6 interaction layers for QM9-scale molecules.

- Training Execution: Execute training script with specified conditions. Typical training requires approximately 40 hours on an A100 GPU for full convergence on QM9 [28].

Molecular Generation Protocol:

- Condition Specification: Provide target conditions as command-line arguments. For composition conditioning, specify atom counts as "h c n o f" (e.g., "7 0 0 2 10" for C₇O₂H₁₀).

- Generation Execution: Run generation script with trained model. For hardware with limited VRAM, reduce batch size using the

--chunk_sizeparameter (default: 1000). - Post-processing: Filter generated structures for chemical validity and remove duplicates using the provided filtering script, which checks valency constraints and molecular connectedness [28].

MEMOS Implementation Protocol

Molecular Generation Workflow:

- Property Target Definition: Specify target emission properties (wavelength, narrowband characteristics) for the desired molecular emitters.

- Markov Sampling Initialization: Configure the Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling parameters to balance exploration and exploitation of the chemical space.

- Multi-objective Optimization: Define the objective function incorporating target properties and synthetic feasibility constraints.

- Iterative Refinement: Execute the self-improving iterative process, which continuously refines candidate molecules toward the target properties.

- Validation: Validate top candidates using density functional theory (DFT) calculations to verify target properties [25].

EDM Implementation Protocol

Implementation Guidelines:

- Data Preparation: Curate molecular dataset with associated 3D structures and target properties.

- Diffusion Process Configuration: Define forward noising and reverse denoising schedules with appropriate noise levels.

- Equivariant Network Setup: Implement equivariant graph neural network layers to ensure generated structures respect physical symmetries.

- Conditioning Integration: Incorporate property conditioning into the diffusion process through cross-attention or feature concatenation.

- Training: Optimize the model to learn the reverse diffusion process conditioned on target properties.

- Sampling: Generate novel molecules by sampling from the learned conditional distribution [27].

Workflow Visualization

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Components | Function/Role |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | QM9 dataset (~130k small organic molecules) | Training and evaluation dataset providing molecular structures and quantum chemical properties |

| Molecular Representations | SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings) | Guarantees molecular validity during generation; used in TrustMol's SGP-VAE [29] |

| Property Prediction | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Ground-truth property validation; used in MEMOS with 80% success rate [25] |

| Validation Tools | Valency checks, connectedness analysis, duplicate removal | Post-generation filtering to ensure chemical validity and novelty [28] |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Ensemble methods, epistemic uncertainty measurement | Enhances trustworthiness by quantifying prediction reliability [29] |

| 3D Structure Processing | ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment), Open Babel | Molecular visualization, manipulation, and format conversion [28] |

The three frameworks examined—cG-SchNet, MEMOS, and EDM—represent the cutting edge of generative AI for inverse molecular design, each with distinct strengths and application domains. cG-SchNet excels in generating 3D molecular structures with precise control over composition and electronic properties, particularly valuable for quantum chemical applications. MEMOS demonstrates remarkable efficiency in specialized domains like molecular emitters, with exceptionally high validation success rates. EDM leverages the power of diffusion models to discover novel molecules beyond the training distribution.

A critical consideration across all architectures is trustworthiness – the alignment between model predictions and actual molecular behavior as determined by the native forward process (ground-truth physics) [29]. Recent approaches like TrustMol address this through uncertainty quantification and latent space regularization, important directions for future development.

As these technologies mature, we anticipate increased integration with experimental validation pipelines, expansion to more complex molecular systems, and development of multi-scale modeling approaches that bridge electronic, atomic, and mesoscopic scales. The continued advancement of these frameworks holds tremendous potential for accelerating the discovery of functional molecules that address pressing challenges in medicine, energy, and materials science.