Improving Molecular Validity in Generative AI: Strategies for Clinically Relevant Drug Design

Generative artificial intelligence holds transformative potential for accelerating drug discovery by designing novel molecular structures.

Improving Molecular Validity in Generative AI: Strategies for Clinically Relevant Drug Design

Abstract

Generative artificial intelligence holds transformative potential for accelerating drug discovery by designing novel molecular structures. However, ensuring the generation of chemically valid, stable, and synthesizable compounds remains a significant challenge that separates theoretical models from practical application. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of molecular validity, advanced methodological frameworks that integrate chemical knowledge, practical troubleshooting techniques to eliminate non-synthesizable outputs, and robust validation strategies to bridge the gap between algorithmic design and real-world drug discovery pipelines. By addressing these critical aspects, we chart a path toward more reliable and clinically applicable generative molecular design.

Defining Molecular Validity: From Chemical Rules to Clinical Relevance

The Critical Challenge of Molecular Validity in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My generative model produces molecules with high predicted affinity, but our chemists deem them unsynthesizable. How can I improve synthetic accessibility?

- Answer: This is a common challenge where models optimize for biological activity without chemical feasibility constraints. To address this:

- Integrate Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Scores: Incorporate a synthetic accessibility score (SAscore) as a direct objective or a filter during the generative process. This penalizes molecules with complex, unstable, or rare functional groups [1].

- Use Robust Molecular Representations: Employ molecular representations like SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings) instead of traditional SMILES. SELFIES are designed to generate 100% syntactically valid molecular structures by construction, drastically reducing invalid outputs [1].

- Apply Post-Generation Filtering: Implement a robust post-processing pipeline that screens generated molecules using rule-based checks and SAscore thresholds before they are presented to chemists for review [2].

FAQ 2: My model performs well on training data but fails to generalize to new target classes or tissue types. What could be causing this?

- Answer: This typically indicates a data distribution shift or a lack of context-awareness in your model.

- Identify Data Biases: Check if your training data is representative of the deployment context. For example, models trained on data from one tissue type may not generalize to another, and models trained predominantly on genomic data from European populations perform poorly on other ancestries [2].

- Incorporate Context-Aware Learning: Enhance your model's adaptability by incorporating multi-modal data. For instance, integrate gene expression profiles alongside molecular structures to create a more context-aware model that can predict drug responses across different biological conditions [2] [3].

- Employ Transfer Learning: Fine-tune a model pre-trained on a large, general chemical dataset on your specific, smaller, domain-specific dataset. This can help the model adapt to new data distributions with limited samples [1].

FAQ 3: How can I trust my model's predictions and understand the reasoning behind a generated molecule?

- Answer: Improving model trustworthiness is critical for adoption.

- Quantify Uncertainty: Implement methods that quantify the model's prediction uncertainty, such as Bayesian deep learning or ensemble methods. This alerts users when predictions are unreliable [2].

- Utilize Explainable AI (XAI): Apply "open box" or explainable models to interpret the model's outputs. Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or attention mechanisms can highlight which molecular substructures or protein residues the model deems important for the interaction, providing a realistic picture of its internal reasoning [2] [3].

FAQ 4: My generated molecules are valid but lack the diversity needed to explore the chemical space effectively. How can I overcome this "mode collapse"?

- Answer: Mode collapse, common in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), occurs when the generator produces limited diversity.

- Use Alternative Architectures: Consider using Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) or Diffusion Models, which are less prone to mode collapse. These models learn a smooth latent space of molecular structures, facilitating the exploration of diverse and novel compounds [1] [4].

- Implement Information Entropy Maximization: Add a regularization term to your model's objective function that encourages the generation of molecules with diverse properties, thereby explicitly promoting diversity [1].

- Leverage Reinforcement Learning (RL): Use RL frameworks with rewards that balance multiple objectives, including not just binding affinity but also novelty and diversity compared to the existing training set [1].

Key Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Synthesizability and Novelty of AI-Generated Molecules

- Objective: To experimentally verify that molecules generated in silico can be synthesized and represent novel chemical entities.

Methodology:

- AI Molecular Generation: Use a generative model (e.g., VAE, GAN, Diffusion Model) to produce a library of candidate molecules for a specific target [1] [4].

- Computational Filtering:

- Apply a synthetic accessibility (SAscore) filter to remove overly complex structures [1].

- Perform virtual screening via molecular docking to predict binding affinity to the target protein [5] [6].

- Check against databases like ChEMBL or ZINC to ensure structural novelty and avoid rediscovering known compounds.

- Retrosynthesis Analysis: Use AI-based retrosynthesis tools (e.g., AIZYNTH, IBM RXN) to propose feasible synthetic routes for the top candidates [4].

- Medicinal Chemistry Review: Have expert chemists evaluate and refine the proposed synthetic routes.

- Laboratory Synthesis: Attempt the synthesis of the highest-priority molecules in the lab.

- Characterization: Confirm the structure and purity of the synthesized compounds using analytical techniques (NMR, LC-MS).

Validation Metrics:

- Synthesis Success Rate: Percentage of proposed molecules successfully synthesized.

- Novelty: Structural dissimilarity from known actives in relevant databases.

- Potency: Experimentally measured IC50 or Ki from subsequent biochemical assays.

Protocol 2: Experimental Workflow for Context-Aware Model Validation

- Objective: To validate that an AI model accurately predicts drug-target interactions across different biological contexts (e.g., cell types, genetic backgrounds).

Methodology:

- Multi-Modal Data Collection: Gather diverse datasets, including drug structures, target protein sequences, and context-specific data such as gene expression profiles from different cell lines or tissue types [2] [3].

- Model Training: Train a hybrid AI model (e.g., a model that concatenates convolutional neural networks for genetic profiles and recurrent neural networks for molecular representations) on the multi-modal data [2] [3].

- Cross-Context Validation: Evaluate the trained model's performance on hold-out test sets from biological contexts not seen during training (e.g., a model trained on liver tissue data is tested on kidney tissue data).

- Experimental Corroboration:

- Select a subset of model-predicted drug-target interactions from the new context.

- Test these predictions empirically using functional assays in the relevant cell lines (e.g., a cell viability assay for an oncology target) [6].

- Use target engagement assays like CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) in intact cells to confirm direct binding in a physiologically relevant environment [6].

Validation Metrics:

- Predictive Accuracy: Precision, Recall, and AUC-ROC of the model on the cross-context test set.

- Experimental Hit Rate: Percentage of model-predicted interactions that are confirmed in the wet-lab experiments.

- Functional Correlation: How well the predicted affinity correlates with the measured functional response in cells.

Quantitative Data on Molecular Validity Challenges

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings and metrics related to challenges and solutions in AI-driven molecular design.

Table 1: Common Challenges in AI-Driven Molecular Generation

| Challenge | Quantitative Impact | Source & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability | Only 6 reasonable molecules selected from 40 candidates, after filtering an initial 30,000 generated by a deep learning model. | [2] |

| Data Imbalance | Active to inactive drug response ratio in a common dataset can be as imbalanced as 1:41. | [2] |

| Data Scarcity | A frequently used benchmark dataset for Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) prediction contains less than 1000 drug molecules. | [2] |

| Generalization (Bias) | 79% of genomic data are from patients of European descent, who comprise only 16% of the global population, leading to biased models. | [2] |

Table 2: Performance of Advanced AI Models in Drug Discovery

| Model / Strategy | Performance Metric | Result / Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Context-Aware Hybrid Model (CA-HACO-LF) | Accuracy | 98.6% in drug-target interaction prediction [3]. |

| AI-Integrated Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) Cycles | Timeline Compression | Reduced hit-to-lead optimization from months to weeks [6]. |

| Generative AI for DDR1 Kinase Inhibitors | Timeline | Novel, potent inhibitors designed in months, not years [7]. |

| Pharmacophore-Feature Integrated AI | Hit Enrichment | 50-fold increase compared to traditional virtual screening methods [6]. |

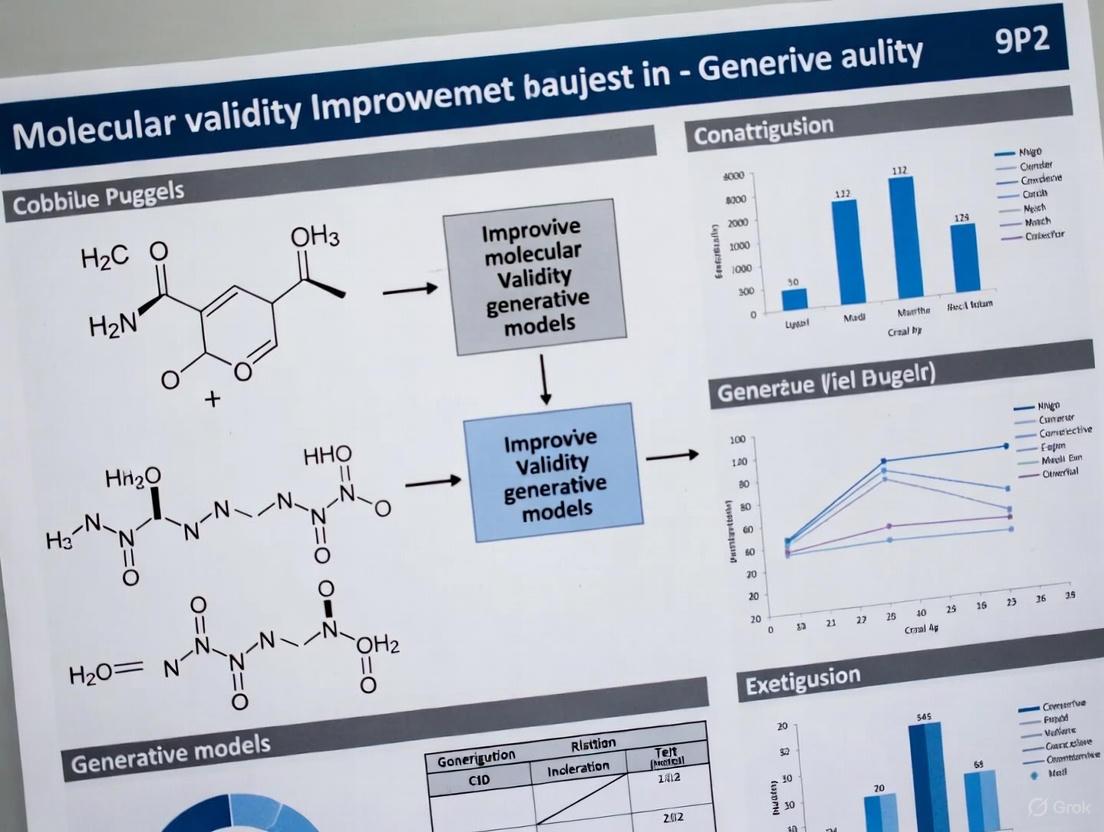

Workflow Visualization for Molecular Validity

The following diagram illustrates a robust, context-aware workflow for generating and validating molecules with high synthetic and biological validity.

AI-Driven Molecular Generation and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental Reagents for AI-Driven Discovery

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Generative AI Models (VAEs, GANs, Diffusion) | De novo molecular design. | Generating novel chemical structures with predefined properties for a target protein [1] [4]. |

| SELFIES Representation | Molecular string format. | Ensuring 100% syntactical validity in generated molecular structures, overcoming SMILES limitations [1]. |

| Synthetic Accessibility Score (SAscore) | Computational metric. | Quantifying the ease of synthesis for a given molecule; used to filter AI-generated candidates [1]. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Target engagement assay. | Confirming direct drug-target binding and measuring engagement in a physiologically relevant cellular context [6]. |

| Multi-objective Optimization (Reinforcement Learning) | AI optimization strategy. | Simultaneously optimizing multiple drug properties (e.g., potency, solubility, SAscore) during molecular generation [1]. |

| AlphaFold / Protein Structure Predictors | Protein modeling tool. | Providing accurate 3D protein structures for structure-based virtual screening when experimental structures are unavailable [5]. |

| FP-GNN (Fingerprint-Graph Neural Network) | Hybrid predictive model. | Combining molecular fingerprints and graph structures to accurately predict drug-target interactions and anticancer drug efficacy [3]. |

This guide addresses the critical challenges of molecular validity that researchers encounter when transitioning from AI-generated molecular designs to viable therapeutic candidates. Moving beyond basic predictive metrics, we focus on the experimental hurdles of synthesizability, stability, and drug-likeness that determine real-world success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Our generative model designs novel protein binders with high predicted affinity, but they fail during experimental validation. What are we missing? A: This common issue often stems on the model's training data and constraints. Ensure your model incorporates:

- Physical and Chemical Constraints: The model should have built-in rules to avoid generating molecules that defy fundamental laws of physics or chemistry [8].

- Rigorous External Validation: Test generated molecules on challenging, "undruggable" targets that are dissimilar to the training data, and conduct wetlab experiments early to confirm functionality [8].

- Generalist Design: Prefer models that unify structure prediction and protein design, as they often learn more generalizable, physics-based patterns compared to modality-specific models [8].

Q: How can we better predict and avoid clinical failure due to poor pharmacokinetics or toxicity early in the discovery process? A: Over 90% of clinical drug development fails, with approximately 40-50% due to lack of efficacy and 30% due to unmanageable toxicity [9]. Shift from a singular focus on Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) to a Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) framework [9]. This classifies drug candidates based on both potency/specificity and tissue exposure/selectivity, helping to identify compounds that require high doses (and carry higher toxicity risks) early on [9].

Q: Can AI help us prioritize synthetic lethal targets beyond PARP inhibitors? A: Yes. Newer approaches are improving the discovery and validation of synthetic lethal pairs [10].

- Advanced Screening: Use combinatorial CRISPR screens, base editing, and saturation mutagenesis to discover new, tractable interactions [10].

- Machine Learning: Apply models to prioritize candidate pairs and identify biomarkers for patient stratification, which is crucial given the cell- and tissue-specific nature of these interactions [10].

- Phenotypic Readouts: Employ high-content imaging and single-cell profiling to dissect complex phenotypes beyond simple cell growth [10].

Q: What is the single most important data type for improving the success of AI-discovered drug targets? A: Genetic evidence. The odds of a drug target successfully advancing to a later stage of clinical trials are estimated to be 80% higher when supported by human genetic evidence [11]. Always integrate genomic and genetic data into your target discovery and validation pipeline.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol 1: Assessing In Vitro Metabolic Stability

Objective: To determine the metabolic stability of a novel compound in liver microsomes, predicting its in vivo clearance.

Methodology:

- Incubation: Incubate the test compound (1 µM) with liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL) in the presence of NADPH-regenerating system in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C [9].

- Sampling: Aliquot the reaction mixture at pre-determined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes) and quench with an equal volume of ice-cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the quenched samples and analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to determine the peak area ratio of the compound to the internal standard.

- Data Processing: Plot the natural logarithm of the remaining compound percentage against time. The slope of the linear regression is the elimination rate constant (k). Calculate the in vitro half-life using: ( t_{1/2} = \frac{ln(2)}{k} ).

Success Criteria: A half-life (t1/2) greater than 45 minutes is generally preferred for promising lead compounds [9].

Protocol 2: Kinetic Aqueous Solubility Measurement

Objective: To measure the kinetic solubility of a compound in aqueous buffer, a key determinant for oral bioavailability.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the compound in DMSO. Add a small volume of this stock to phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to achieve a final concentration, typically below 100 µM, with final DMSO concentration not exceeding 1%.

- Agitation and Equilibrium: Shake the mixture for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Filtration: Pass the solution through a pre-wetted filter (e.g., 0.45 µm PVDF or cellulose membrane) to separate the undissolved precipitate.

- Quantification: Dilute the filtrate appropriately and quantify the compound concentration using a validated UV/Vis spectrophotometry or HPLC-UV method against a standard curve.

Success Criteria: A solubility > 10 µM is often considered a minimum for further development, though higher is typically required for good oral absorption [9].

Quantitative Data on Drug Development and Candidate Profiling

Table 1: Analysis of Clinical Drug Development Failures (2010-2017)

| Failure Cause | Percentage of Failures | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Clinical Efficacy | 40% - 50% | Poor target validation in humans; biological discrepancy between animal models and human disease; inadequate tissue exposure [9]. |

| Unmanageable Toxicity | ~30% | On-target or off-target toxicity in vital organs; poor tissue selectivity; accumulation in non-target tissues [9]. |

| Poor Drug-Like Properties | 10% - 15% | Low solubility; inadequate metabolic stability; poor permeability [9]. |

| Commercial & Strategic | ~10% | Lack of commercial need; poor strategic planning [9]. |

Table 2: STAR (Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity–Activity Relationship) Drug Candidate Classification

| Class | Specificity/Potency | Tissue Exposure/Selectivity | Required Dose | Clinical Outcome & Success Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Low | Superior efficacy/safety; high success rate [9]. |

| Class II | High | Low | High | Moderate efficacy with high toxicity; requires cautious evaluation [9]. |

| Class III | Adequate | High | Low | Good efficacy with manageable toxicity; often overlooked [9]. |

| Class IV | Low | Low | N/A | Inadequate efficacy/safety; should be terminated early [9]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Experimental Validation

| Reagent / Assay | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes | In vitro assessment of metabolic stability and prediction of human clearance [9]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | An in vitro model of the human intestinal mucosa to predict oral absorption and permeability [9]. |

| hERG Inhibition Assay | A critical safety pharmacology assay to predict potential for cardiotoxicity (torsade de pointes) [9]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screening Libraries | For functional genomic validation of novel targets and identification of synthetic lethal interactions [10]. |

| Pan-Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | A collection of cancer cell lines with extensive genomic data used for profiling genetic dependencies and drug sensitivity [10]. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

STAR Framework Drug Candidate Selection

AI Driven Target Validation Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Ring Strain and Stability in Cycloalkanes

Q: Why are some ring sizes more unstable than others? A: Ring instability is primarily due to ring strain, which is the total energy from three factors: angle strain, torsional strain, and steric strain. Smaller rings like cyclopropane and cyclobutane are highly strained because their bond angles deviate significantly from the ideal tetrahedral angle of 109.5°, forcing eclipsing conformations. Rings of 14 carbons or more are typically strain-free [12].

Q: How is ring strain measured experimentally? A: The strain energy of a cycloalkane is determined by measuring its heat of combustion and comparing it to a strain-free reference compound. The extra heat released by the cycloalkane corresponds to its strain energy [12] [13]. The table below summarizes key data.

Table 1: Strain Energies and Properties of Small Cycloalkanes [12] [13]

| Cycloalkane | Ring Size | Theoretical Bond Angle (Planar) | Strain Energy (kJ/mol) | Major Strain Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclopropane | 3 | 60° | 114 | Severe angle strain, torsional strain |

| Cyclobutane | 4 | 90° | 110 | Angle strain, torsional strain |

| Cyclopentane | 5 | 108° | 25 | Little angle strain, torsional strain |

| Cyclohexane | 6 | 120° | 0 | Strain-free (adopts puckered conformations) |

Q: What was the flaw in Baeyer's Strain Theory? A: Baeyer's theory incorrectly assumed all cycloalkanes are flat. In reality, most rings (especially those with 5 or more carbons) adopt non-planar, puckered conformations that minimize strain by allowing bond angles to approach 109.5° and reducing eclipsing interactions [12] [13].

FAQ: Hazards and Instability of Reactive Functional Groups

Q: Which functional groups are most associated with instability and hazardous reactions? A: Instability often arises from high-energy bonds (e.g., strained rings), or groups prone to undesirable reactions like polymerization, oxidation, or decomposition. The following table outlines common problematic functional groups and their failure modes, which must be considered for both laboratory safety and molecular stability in generative models [14].

Table 2: Common Failure Modes of Reactive Functional Groups [14]

| Functional Group Class | Common Failure Modes & Hazards | Key Instability Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Azides, Fulminates, Acetylides | Explosive decomposition; shock- and heat-sensitive | Formation of highly energetic salts with heavy metals (e.g., lead azide); can explode spontaneously or from light exposure |

| Epoxy Compounds (Epoxides) | Polymerization; strong irritants; toxic | Ring strain of the 3-membered oxirane ring; polymerization catalyzed by acids or bases, generating heat and pressure |

| Aliphatic Amines | Caustic; severe irritants; highly flammable | Strong basicity causes corrosion; lower amines have flashpoints below 0°C |

| Aldehydes | Toxic; flammable; reactive | Low molecular weight aldehydes (e.g., formaldehyde) are highly reactive and flammable |

| Ethers | Form explosive peroxides; highly flammable | Peroxides form upon standing in air, which can explode upon heating or shock |

| Alkali Metals | Water and air reactive; flammable | Vigorous reaction with water produces hydrogen gas and strong bases (e.g., KOH) |

Q: How can I manage reactive or interfering functional groups during synthesis? A: The standard strategy is functional group protection and deprotection. This involves temporarily converting a reactive group into a less reactive derivative (protection) and later restoring the original group (deprotection). Sustainable methods using electrochemistry or photochemistry are emerging as greener alternatives to traditional approaches [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Strain Energy via Heat of Combustion

Purpose: To determine the strain energy of a cycloalkane by measuring the heat released during its complete combustion [12].

Principle: The heat of combustion (ΔH°comb) for a strained cycloalkane is more exothermic than for a strain-free reference (e.g., a long-chain alkane). The difference, when normalized per CH₂ group, quantifies the ring strain.

Procedure:

- Calibration: Calibrate a bomb calorimeter using a standard material with a known heat of combustion (e.g., benzoic acid).

- Combustion: Precisely weigh a pure sample of the cycloalkane (e.g., cyclopropane) and load it into the calorimeter bomb. Pressurize the bomb with excess oxygen.

- Measurement: Ignite the sample electronically and record the temperature change (ΔT) of the surrounding water jacket in the calibrated calorimeter.

- Calculation:

- Calculate the heat released using the calorimeter's heat capacity (C_cal):

q_comb = -C_cal * ΔT. - Normalize this value per mole of compound and per CH₂ group.

- Compare the per-CH₂ heat of combustion to that of a strain-free reference. The strain energy is:

Strain Energy = [ΔH°comb (cycloalkane) - ΔH°comb (reference)] * n, wherenis the number of CH₂ units in the ring [12] [13].

- Calculate the heat released using the calorimeter's heat capacity (C_cal):

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Deprotection of Functional Groups

Purpose: To remove a protecting group using electrochemical methods, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional reagents [15].

Principle: Electrochemical deprotection uses electron transfer at an electrode surface to drive the cleavage of a protecting group, avoiding stoichiometric chemical oxidants or reductants and improving functional group tolerance.

Procedure:

- Cell Setup: Assemble an undivided electrochemical cell equipped with appropriate electrodes (e.g., carbon felt or RVC as working electrode, platinum as counter electrode).

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the protected substrate in a suitable electrolyte solution (e.g., LiClO₄ in a mixture of methanol and water). Add the solution to the cell.

- Electrolysis: Apply a constant current or controlled potential under an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ or Ar). Monitor the reaction progress (e.g., by TLC or LCMS).

- Work-up: Once the reaction is complete, turn off the power. Dilute the reaction mixture with water and extract with an organic solvent. Remove the electrolyte by washing with water or through filtration.

- Purification: Purify the crude product using standard techniques (e.g., column chromatography or recrystallization) to obtain the deprotected product.

Molecular Design Visualizations

Diagram 1: Molecular Stability Failure Map

Diagram 2: Ring Strain Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Stability Assessment and Mitigation

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Failure Modes |

|---|---|---|

| Bomb Calorimeter | Measures heat of combustion to quantify ring strain energy. | Provides experimental data on the stability of novel ring systems generated in silico [12] [13]. |

| Electrochemical Cell | Provides a sustainable platform for redox-based protection and deprotection reactions. | Enables manipulation of sensitive functional groups under mild conditions, improving synthetic success rates [15]. |

| Silylating Agents (e.g., TBS-Cl, TIPS-Cl) | Protect hydroxyl groups (-OH) as silyl ethers, stable under basic and oxidative conditions. | Prevents unwanted side reactions from alcohols during multi-step syntheses, a key strategy in complex molecule assembly [15]. |

| Urethane-Based Protecting Groups (e.g., Boc, Fmoc) | Protect amine groups (-NH₂) with groups that can be cleanly removed under specific acidic (Boc) or basic (Fmoc) conditions. | Crucial for amino acid and peptide chemistry, preventing side reactions and enabling controlled synthesis [15]. |

| ZINC / ChEMBL / GDB-17 Databases | Large-scale public databases of purchasable and bioactive molecules. | Provide real-world chemical data for training and validating generative models, helping them learn stable molecular patterns [16]. |

| Perlast (FFKM) O-Rings | High-performance seals resistant to extreme temperatures and aggressive chemicals. | Practical engineering solution for handling reactive chemicals and extreme conditions in the laboratory, mitigating physical failure modes [17]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Addressing Invalid SMILES Generation in Generative Models

- Problem: My generative model produces a high percentage of invalid or nonsensical SMILES strings.

- Explanation: SMILES is a precise notation with strict syntactic rules (e.g., balanced parentheses for branches, paired numbers for rings). Models can struggle with these long-term dependencies, leading to invalid structures that violate chemical valence rules [18].

- Solution:

- Pre-process Data: Use canonical SMILES for training to ensure consistency and reduce the complexity the model must learn [19] [20].

- Consider Alternative Representations: Evaluate more robust representations like SELFIES, which are designed to always produce syntactically valid strings, or fragment-based approaches like t-SMILES that reduce the probability of invalid structures [18] [1].

- Implement Post-Generation Validation: Always include a chemical validator in your pipeline to check the validity of generated SMILES before further analysis [20].

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Handling Graph Representation Limitations for Molecular Generation

- Problem: My Graph Neural Network (GNN) generates valid molecules but fails to capture complex long-range interactions or higher-order structures.

- Explanation: The expressive power of standard GNNs is bounded by their inability to distinguish certain graph structures (the Weisfeiler-Leman graph isomorphism limit). This can restrict their ability to model complex molecular properties [18].

- Solution:

- Incorporate Advanced Graph Techniques: Implement subgraph-based methods or message-passing simple networks that enhance the model's ability to learn richer topological features [18].

- Hybrid Models: Use a graph-based encoder to capture local connectivity and a sequence-based decoder (like a Transformer) to model the long-range dependencies in the molecular structure [18] [1].

Troubleshooting Guide 3: Managing Computational Complexity of 3D Molecular Representations

- Problem: Training generative models on 3D molecular structures is computationally expensive and slow.

- Explanation: 3D representations contain rich spatial information (atomic coordinates, bond angles, dihedrals) which significantly increases the dimensionality and complexity of the data compared to 1D (SMILES) or 2D (graph) representations [18].

- Solution:

- Leverage Pre-trained Models: Utilize existing pre-trained models for 3D structure prediction or generation, such as those based on diffusion models, to bootstrap your research [1] [8].

- Adopt Equivariant Architectures: Use equivariant neural networks (e.g., SE(3)-equivariant GNNs) which are specifically designed for 3D data and can be more data-efficient [1].

- Curriculum Learning: Start training on simpler, smaller molecules or use curriculum learning strategies to progressively increase the complexity of the training data [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between canonical and isomeric SMILES?

Canonical SMILES refers to a unique, standardized string representation for a given molecular structure, ensuring that the same molecule always has the same SMILES string across different software [19] [20]. Isomeric SMILES includes additional stereochemical information, specifying configuration at tetrahedral centers and double bond geometry, which is necessary to distinguish between isomers [19].

FAQ 2: My model generates molecules with correct connectivity but incorrect stereochemistry. How can I enforce 3D validity?

This indicates that your representation or model lacks awareness of spatial configuration. To address this:

- Use Isomeric SMILES: Train your model using isomeric SMILES strings that include stereochemical descriptors like

@,@@,/, and\[20]. - Incorporate 3D Information: Move beyond 2D graphs to representations that explicitly include spatial coordinates, allowing the model to learn the energetic feasibility of different conformations [18] [1].

- Integrate Physical Constraints: Use models like BoltzGen that have physical and chemical constraints built-in to ensure generated structures are physically plausible [8].

FAQ 3: When should I choose a fragment-based representation like t-SMILES over classical SMILES?

Consider t-SMILES or other fragment-based approaches when:

- Validity is Critical: You need near 100% theoretical validity in your generated molecules [18].

- Working with Low-Resource Data: You have limited labeled data, as fragment-based methods can help avoid overfitting and improve generalization [18].

- Goal-Directed Design is Key: You are optimizing for specific properties, as t-SMILES has shown superior performance in goal-directed tasks compared to classical SMILES [18].

FAQ 4: How can I quantitatively evaluate the improvement in molecular validity after implementing a new representation?

You should track the following metrics before and after the change [18] [1]:

- Validity Rate: The percentage of generated strings that correspond to a chemically valid molecule.

- Uniqueness: The proportion of valid molecules that are distinct from one another.

- Novelty: The fraction of generated valid molecules not present in the training set.

- Frechet ChemNet Distance (FCD): Measures the similarity between the distributions of generated and real molecules based on their chemical and biological properties.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Molecular Representation Performance on Benchmark Tasks

This table compares the performance of different molecular representations across key metrics as reported in systematic evaluations [18].

| Representation Type | Theoretical Validity (%) | Uniqueness (%) | Novelty (%) | Performance on Goal-Directed Tasks (vs. SMILES baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | Can be low, model-dependent | Varies | Varies | Baseline |

| DeepSMILES | Higher than SMILES | Varies | Varies | Mixed results |

| SELFIES | 100% | Varies | Varies | Improved |

| t-SMILES (TSSA, TSDY, TSID) | ~100% (Theoretical) | High | High | Significantly Outperforms |

| Graph-Based (GNN) | 100% (with valence checks) | High | High | Strong performance |

Table 2: Key Fragmentation Algorithms for Fragment-Based Representations

This table outlines common algorithms used to break down molecules for frameworks like t-SMILES [18].

| Algorithm Name | Description | Key Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| JTVAE | Junction Tree Variational Autoencoder fragmentation. | Generating valid molecular graphs. |

| BRICS | A retrosynthetic combinatorial fragmentation scheme. | Creating chemically meaningful, synthesizable fragments. |

| MMPA | Matched Molecular Pair analysis for fragmentation. | Analyzing structure-activity relationships. |

| Scaffold | Separates the core molecular scaffold from side chains. | Scaffold hopping and core structure-based design. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Molecular Representation Validity on a Low-Resource Dataset

Objective: To compare the validity, novelty, and uniqueness of molecules generated by models trained on different molecular representations (e.g., SMILES, SELFIES, t-SMILES) using a limited amount of data.

Methodology:

- Dataset Selection: Use a labeled, low-resource dataset such as JNK3 or AID1706 [18].

- Model Training: Train identical generative model architectures (e.g., Transformer) on the dataset, where the only variable is the input representation (SMILES, SELFIES, t-SMILES).

- Generation: Use each trained model to generate a fixed number of molecular structures (e.g., 10,000).

- Validation & Analysis:

- Pass all generated strings through a chemical validator (e.g., RDKit) to calculate the Validity Rate.

- Remove duplicates from the valid set to calculate Uniqueness.

- Check the valid, unique set against the training set to calculate Novelty.

- Comparison: Compare the results across the different representations to determine which maintains higher validity and diversity with limited data.

Protocol 2: Goal-Directed Molecular Optimization Benchmarking

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of a molecular representation in a practical drug discovery context by optimizing for a specific property.

Methodology:

- Task Definition: Choose a goal-directed task from a benchmark like those on ChEMBL, for example, optimizing for a specific biological activity or a combination of properties like QED (drug-likeness) and SAscore (synthetic accessibility) [1].

- Model Setup: Implement a generative model (e.g., a Reinforcement Learning-based framework) with the representation under test (e.g., t-SMILES TSDY).

- Optimization Loop: Run the model for a fixed number of steps, where the reward function is based on the desired property.

- Evaluation:

- Measure the success rate (percentage of generated molecules above a property threshold).

- Evaluate the diversity of the successful molecules.

- Compare the performance against baseline models using classical SMILES or graph representations [18].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Molecular Representation Pathways

t-SMILES Generation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Relevance to Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used for parsing SMILES, molecular validation, calculating descriptors (e.g., QED, LogP), and performing fragmentation [18]. |

| Chemical Validation Suite | Software to check valency, ring structure, and stereochemistry. | A critical post-generation step to quantify the validity rate of molecules produced by a generative model [20]. |

| Fragmentation Algorithm (e.g., BRICS) | A rule-based method to break molecules into chemically meaningful substructures. | Used to create the fragment dictionary for generating t-SMILES or other fragment-based representations [18]. |

| t-SMILES Coder | The algorithm implementation for converting fragmented molecules into t-SMILES strings (TSSA, TSDY, TSID). | Provides the specific string-based representation for model training, enhancing validity and performance [18]. |

| Pre-trained Language Model (Transformer) | A neural network architecture adept at handling sequence data. | Serves as the core generative model for learning from and producing SMILES, SELFIES, or t-SMILES sequences [18] [1]. |

Architectural Innovations for Intrinsically Valid Molecule Generation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our generative model produces chemically valid molecules, but they lack biological relevance. How can knowledge graphs (KGs) help?

A1: Biomedical KGs capture structured relationships between biological entities (e.g., genes, proteins, diseases, drugs). Integrating these embeddings directly into the generative process steers molecular generation toward candidates with higher therapeutic potential. For instance, the K-DREAM framework uses Knowledge Graph Embeddings (KGEs) from sources like PrimeKG to augment diffusion models, ensuring generated molecules are not just chemically sound but also aligned with specific biological pathways or therapeutic targets [21].

Q2: What are the most common data-related issues when training knowledge-enhanced models, and how can we troubleshoot them?

A2: Common data issues and solutions are summarized below [22] [21] [23]:

| Data Issue | Impact on Model | Troubleshooting Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Data | Poor generalization and inability to learn complex patterns [24]. | Use data augmentation (e.g., atomic or bond rotation for molecular graphs) [24] and transfer learning from pre-trained models [24]. |

| Noisy/Biased Data | Models learn and propagate incorrect or skewed associations, leading to invalid outputs [24] [23]. | Implement rigorous data cleaning; use statistical techniques to detect outliers [24]; ensure training data is representative of real-world distributions [23]. |

| Incomplete Knowledge Graph | The model's biological knowledge is fragmented, limiting its reasoning capability [21]. | Use techniques like the stochastic Local Closed World Assumption (sLCWA) during KGE training to mitigate overfitting from inherent KG incompleteness [21]. |

Q3: Our model suffers from "mode collapse," generating a limited diversity of molecules. How can we resolve this?

A3: Mode collapse, where the generator produces a narrow range of outputs, is a known instability in adversarial training [24]. To troubleshoot:

- Tune the Loss Function: Experiment with different loss functions. A combination of adversarial loss and feature matching loss can enhance diversity [24].

- Apply Batch Normalization: This technique helps stabilize the training process and improve convergence [24].

- Leverage KGs: The rich, multi-relational data in knowledge graphs provides a diverse guidance signal, naturally pushing the model to explore a broader region of the chemical-biological space [21].

Q4: How can we effectively validate that our generated molecules are both novel and therapeutically relevant?

A4: Retrospective validation based solely on chemical similarity has limitations [22]. A robust validation protocol should include:

- Standard Metrics: Calculate validity, uniqueness, and novelty relative to the training set [22].

- Docking Studies: Perform in-silico docking against the intended protein target to assess binding affinity and predicted efficacy [21].

- Knowledge Graph Validation: Cross-reference generated molecules against structured biomedical knowledge. One proposed method uses KGs as a check against harmful or incorrect content, validating stochastically generated outputs against hard-coded biological relationships [23].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Integrating Knowledge Graph Embeddings with a Generative Model

This protocol outlines the methodology for the K-DREAM framework [21].

1. Objective: Augment a diffusion-based molecular generative model with biomedical knowledge to produce biologically relevant drug candidates.

2. Materials and Representations:

- Molecular Representation: Represent a molecule as a graph G = (X, E), where X is a node feature matrix for N heavy atoms, and E is an adjacency matrix denoting bonds [21].

- Knowledge Graph: Use a structured biomedical KG (e.g., PrimeKG). A KG is a set of triples: (subject, relation, object).

3. Methodology: 1. Generate Knowledge Graph Embeddings (KGEs): * Use a KGE model like TransE to map entities and relations from the KG into a continuous vector space [21]. * Train the TransE model on the PrimeKG dataset for a set number of epochs (e.g., 100) with a defined learning rate (e.g., 0.001) using the stochastic Local Closed World Assumption (sLCWA) for negative sampling [21]. 2. Train the Unconditional Generative Model: * Implement a score-based graph diffusion model. The forward process is defined by a Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) that gradually adds noise to the graph Gₜ [21]. 3. Integrate KGEs into the Generative Process: * The trained KGEs are incorporated into the diffusion model's framework. These embeddings guide the reverse diffusion process, steering the generation of novel molecular graphs (G₀) so that their inferred biological characteristics align with the structured knowledge [21].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this integration process:

Protocol: Simulating a Data-Poisoning Attack for Robustness Evaluation

This protocol is based on a study that highlights the vulnerability of models trained on web-scale data [23].

1. Objective: Assess a medical generative model's susceptibility to propagating false information and evaluate mitigation strategies.

2. Materials:

- Training Dataset: A public dataset like The Pile [23].

- Model: A generative model architecture (e.g., an autoregressive, decoder-only transformer).

- Misinformation Corpus: AI-generated false medical articles created via API calls (e.g., using OpenAI's GPT-3.5-turbo) [23].

3. Methodology: 1. Corrupt the Training Data: * Select target medical concepts (e.g., from the Unified Medical Language System). * Replace a small, defined fraction (e.g., 0.001% to 1.0%) of the original training tokens with tokens from the misinformation corpus [23]. 2. Train the Model: * Train the model on the corrupted dataset. For comparison, train a baseline model on the clean dataset. 3. Evaluate Model Harm: * Benchmark Performance: Use standard medical question-answering benchmarks (e.g., MedQA). Note that these may not detect the poisoning [23]. * Manual Clinical Review: Have clinicians (blinded to the model's status) review generated text for medically harmful content [23]. * KG-based Harm Detection: Implement an algorithm that cross-checks the model's outputs against a biomedical knowledge graph to flag contradictory or harmful statements. This method has been shown to capture a high percentage of harmful content [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources for building and testing knowledge-enhanced generative models.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| PrimeKG | A comprehensive biomedical knowledge graph containing millions of relationships between genes, drugs, diseases, and phenotypes. Used to train Knowledge Graph Embeddings (KGEs) that provide biological context to generative models [21]. |

| TransE Model | A knowledge graph embedding algorithm that models relationships as translations in a vector space. Its interpretability and efficiency make it suitable for integrating biological relationships into the generative process [21]. |

| The Pile | An 825 GiB diverse, open-source language modeling dataset. Often used for pre-training large language models; can be used to study data poisoning vulnerabilities in a medical context [23]. |

| PyKEEN | A Python library designed to train and evaluate Knowledge Graph Embeddings. It provides implementations of KGE models like TransE and standardized interfaces to datasets like PrimeKG [21]. |

| Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) | A compendium of controlled medical vocabularies. Used to build a diverse concept map of medical terms for vulnerability analysis and data-poisoning simulations [23]. |

| REINVENT | A widely used RNN-based generative model for de novo molecular design. Useful as a benchmark model in comparative studies, for instance, to evaluate the ability to recapitulate late-stage project compounds from early-stage data [22]. |

Workflow: Knowledge Graph-Based Harm Detection

To counter the risk of models generating incorrect or harmful medical information, the following detection system can be implemented. This workflow cross-references model outputs against a trusted knowledge graph [23].

Reinforcement Learning and Multi-Objective Optimization for Property-Guided Generation

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

This section addresses specific challenges you might encounter when building and training RL and MOO models for molecular generation.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

| Problem Category | Specific Issue & Symptoms | Potential Cause | Solution & Recommended Action | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Training & Stability | Unstable learning or failure to converge.Reward signals fluctuate wildly, policy performance collapses. | High-variance gradient estimates from policy gradient methods; poorly scaled reward functions [25] [26]. | Use value function-based methods (e.g., DQN) for greater stability where applicable [25]. Implement a reward normalization strategy. | Conduct a full hyperparameter sweep, particularly on learning rates and discount factors (γ). |

| Molecular Validity | Generated molecular structures are chemically invalid.Atoms have incorrect valences, bonds are impossible. | Action space allows chemically invalid transitions (e.g., violating valence constraints) [25]. | Design the action space to exclude chemically invalid actions entirely. Define actions for atom/bond addition and removal that respect chemical rules [25]. | Use a chemistry-aware toolkit (e.g., RDKit) to validate every proposed action in the environment. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | Model converges to a single objective, ignoring others.Generated molecules excel in one property but perform poorly on the rest. | Simple scalarization (e.g., weighted sum) fails to capture trade-offs; one objective dominates the reward signal [26] [27]. | Employ Pareto-based optimization schemes (e.g., Clustered Pareto) to find optimal trade-off solutions instead of scalarization [26]. Integrate evolutionary algorithms to maintain a diverse Pareto front [27]. | Analyze the correlation between target objectives beforehand and adjust the optimization framework accordingly. |

| Sample Efficiency & Diversity | Low diversity in generated molecules (Mode Collapse).Model produces very similar structures, lacking chemical novelty. | Pre-training on a biased dataset limits exploration; policy gets stuck in a local optimum [25] [26]. | Use a fixed-parameter exploration model for sampling to improve internal diversity [26]. Reduce reliance on pre-training or use a larger, more diverse dataset [25]. | Implement a novelty metric or diversity penalty as part of the reward function. |

| Reward Design | Agent exploits reward function without true improvement (Reward Hacking).Metrics improve, but generated molecules are not useful. | The reward function is not perfectly correlated with the true, complex objective of drug-likeness or synthetic accessibility. | Use a multi-faceted reward from an ensemble of predictive models. Conduct post-hoc physical validation (e.g., molecular simulation) to verify results [28] [29]. | Design reward functions that are as aligned as possible with the final experimental goal, even if they are more costly to compute. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using Reinforcement Learning (RL) over other generative models like VAEs or GANs for molecular generation? RL provides a natural framework for goal-directed generation. Unlike VAEs that learn a distribution of existing data, RL agents can be trained to optimize specific properties (rewards) through trial-and-error, exploring regions of chemical space not present in the training data [25]. This allows for true inverse design, where you start with a desired property profile and the model finds structures that match it [28] [30].

Q2: How can I ensure my model performs true multi-objective optimization instead of just single-objective optimization with a combined score? Traditional methods use scalarization (e.g., weighted sums) to combine objectives, which requires pre-defining weights and often finds only one point on the Pareto front. Advanced MOO methods instead aim to find a set of non-dominated solutions, known as the Pareto front, which represents the optimal trade-offs between objectives. Techniques like Clustered Pareto-based RL (CPRL) [26] or Multi-Objective Evolutionary RL (MO-ERL) [27] are specifically designed for this. They maintain a population of diverse solutions, allowing a researcher to see multiple optimal choices without re-running experiments.

Q3: My RL agent generates a high proportion of invalid molecules. How can I improve chemical validity? There are two primary strategies. The first and most effective is to constrain the action space so that every possible action (e.g., adding an atom, changing a bond) is guaranteed to result in a chemically valid molecule. This can be done by using chemistry-aware rules to define valid actions [25]. The second strategy is to incorporate a validity penalty into the reward function, discouraging the agent from generating invalid structures.

Q4: What are some best practices for designing a good reward function? A robust reward function is crucial for success. Key practices include:

- Sparse vs. Dense Rewards: Providing small, intermediate rewards (dense rewards) can guide the agent more effectively than a single reward at the end of an episode [25].

- Discounting: Use a discount factor (γ) to weigh immediate rewards more heavily than long-term ones, helping the agent learn effective strategies [25].

- Multi-objective Rewards: Combine multiple property predictions into the reward. For example, optimize for drug-likeness while maintaining similarity to a starting molecule [25] [26].

- Validation: Always validate the generated molecules using independent, high-fidelity methods like molecular dynamics simulations or density functional theory (DFT) to ensure the reward function correlates with real-world properties [28] [29] [30].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing a Clustered Pareto-based RL (CPRL) Framework

This protocol is based on the method described by Wang & Zhu (2024) [26] for multi-objective molecular generation.

Objective: To generate novel, valid molecules that optimally balance multiple, potentially conflicting, target properties.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Pre-training:

Reinforcement Learning Fine-tuning:

- Initialize the RL agent with the weights from the pre-trained model.

- The agent interacts with the environment by generating molecules step-by-step.

Clustered Pareto Optimization (Performed on a batch of sampled molecules):

- Molecular Clustering: Use an aggregation-based clustering algorithm (e.g., based on molecular fingerprints) to group molecules with similar patterns. This helps filter out "unbalanced" molecules that are poor trade-off candidates [26].

- Pareto Frontier Ranking: From the clustered molecules, construct the Pareto frontier. A molecule is on the Pareto frontier if no other molecule is better in all target properties. Assign a ranking to molecules based on their dominance.

- Reward Calculation: Calculate a final reward for each molecule based on its Pareto rank and a Tanimoto-inspired similarity measure to balance diversity and performance. This reward is used to update the RL agent [26].

Policy Update and Exploration:

- Update the agent's policy using the calculated final rewards (e.g., via policy gradient methods).

- To enhance diversity, use an exploration policy where a separate, fixed-parameter model co-controls the sampling probability distribution [26].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from CPRL Protocol [26]

| Metric | Description | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Validity | The fraction of generated molecules that are chemically valid. | 0.9923 |

| Desirability | The fraction of generated molecules that satisfy all target property thresholds. | 0.9551 |

| Diversity | Internal diversity of the generated set of molecules (e.g., based on Tanimoto similarity). | Improved via exploration policy |

Protocol: Molecular Dynamics Validation of Generated Polymers

This protocol outlines how to validate polymer candidates generated by models like PolyRL [28] or TopoGNN [29] using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

Objective: To computationally verify that generated polymer structures exhibit the target properties (e.g., specific radius of gyration, gas separation performance) predicted by the machine learning model.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Coarse-Grained Model Construction:

- Map the atomistic structure of the generated polymer to a coarse-grained (CG) model, such as the Kremer-Grest model, to reduce computational cost [29].

- Define the CG interaction potentials and parameters.

System Equilibration:

- Place the polymer in a simulation box with an appropriate solvent or gas mixture.

- Run energy minimization and equilibration simulations (e.g., in the NPT or NVT ensemble) to relax the system to a stable state.

Production Run:

- Perform a long-timescale MD simulation to sample the polymer's configurational space.

- For gas separation membranes, this may involve simulating the diffusion and solubility of gas molecules through the polymer matrix [28].

Property Analysis:

- Size/Shape: Calculate the mean squared radius of gyration (\langle {R}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}^{2}\rangle) from the trajectory [29].

- Gas Permeability: Compute the permeability and selectivity of target gases from free energy and diffusion calculations [28].

- Rheology: Analyze the shear viscosity or stress relaxation modulus for melt or solution properties [29].

Validation:

- Compare the simulated properties with the target values used to guide the generative model. A successful candidate will have simulated properties that match the targets within statistical error.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RL-based Molecular Generation

| Tool / Resource Name | Function / Purpose | Brief Description of Role |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics & Validation | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics used to handle molecular representations (SMILES, graphs), ensure chemical validity, calculate molecular descriptors, and perform operations like scaffold analysis [25]. |

| OpenMM / LAMMPS | Molecular Simulation | High-performance MD simulation engines used for the physical validation of generated molecules or polymers. They calculate target properties like (\langle {R}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}^{2}\rangle) or gas permeability [28] [29]. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep Learning Framework | The foundational ML libraries used to build, pre-train, and fine-tune generative models (GPT-2, LSTM, VAE) and RL agents (REINFORCE, DQN) [28] [25] [26]. |

| REINVENT | RL Framework for Chemistry | A specialized RL framework for de novo molecular design, which can be adapted for multi-objective optimization tasks [28]. |

| Pareto Optimization Library (e.g., PyMOO) | Multi-Objective Optimization | Provides algorithms for calculating Pareto frontiers and selecting optimal trade-off solutions, which can be integrated into the RL loop [26] [27]. |

Diffusion Models for 3D Molecular Structure Generation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my generated 3D molecule have distorted or physically implausible ring structures?

A1: This is a common issue where models produce energetically unstable structures like three- or four-membered rings or fused rings. The problem often stems from atom-bond inconsistency. Many models first generate atom coordinates and then assign bond types based on canonical lengths. Minor errors in atom placement can lead to incorrect bond identification, distorting the final molecular structure [31].

- Solution: Implement a bond diffusion process. Instead of treating bonds as a secondary step, integrate bond type generation directly into the diffusion process alongside atom types and coordinates. This explicitly models the interdependence between atoms and bonds, guiding coordinate generation with bond information and significantly improving structural plausibility [31].

Q2: How can I steer the generation process toward molecules with specific, desired properties like high binding affinity or optimal drug-likeness?

A2: Pure generative models trained on general datasets may not consistently yield molecules with optimal target properties. The solution is to incorporate explicit property guidance into the training and sampling cycles [31].

- Solution: Use guidance mechanisms during the reverse diffusion process.

- Classifier-Free Guidance: Condition the model directly on properties like binding affinity (Vina Score), quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), and synthetic accessibility (SA). This allows you to steer sampling by adjusting the conditioning signal [32] [31].

- Property-Conditioned Training: Augment your training data by introducing intentionally distorted molecules and annotating each sample with a quality label (e.g., extent of distortion). Training the model to distinguish between favorable and unfavorable conformations enables selective sampling from high-quality regions of the latent space [33].

Q3: My model training is computationally expensive and slow. How can I make model adaptation more efficient for new tasks?

A3: The high cost of training 3D equivariant diffusion models from scratch is a significant barrier. A practical solution is to leverage pre-trained models and modular frameworks [32].

- Solution: Utilize frameworks that offer pre-trained models on large, diverse 3D molecular datasets. These models have already learned fundamental chemical rules and can be adapted to new, specific tasks (like targeting a new protein) without full retraining. Look for frameworks that support curriculum learning, where the model first learns simple concepts before progressing to complex chemical environments, and offer modular guidance for easy application to new problems [32].

Q4: The molecules generated for a protein pocket lack diversity and novelty. What can I do?

A4: This can occur when the model's sampling is overly constrained. To address this, you can use structured guidance techniques to explore the chemical space around a reference.

- Solution: Implement molecular inpainting and outpainting.

- Inpainting: Hold a core part of a molecule (e.g., a known scaffold) fixed and allow the model to generate structural variants around it. This is useful for exploring R-group variations [32].

- Outpainting: Start with an existing fragment and allow the model to extend it by adding new chemical groups, facilitating lead optimization and scaffold hopping [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Validity Scores (e.g., RDKit Parsability, PoseBusters Test)

Problem: Generated molecules fail basic chemical validity checks or have clashing atoms.

Diagnosis and Steps for Resolution:

Verify the Integration of Bond Information:

- Symptom: High rates of invalid valency or unnatural bond lengths/angles.

- Action: Ensure your model uses a joint diffusion process for both atoms and bonds. Ablation studies confirm that models lacking bond diffusion perform significantly worse on validity metrics [31].

- Protocol: Follow the two-phase diffusion framework from DiffGui [31]:

- Phase 1: Diffuse bond types toward a prior distribution while only marginally disrupting atom types and positions. This allows the model to learn bond types from dynamic atom distances.

- Phase 2: Heavily perturb atom types and positions to their priors. An E(3)-equivariant GNN must be modified to update both atom and bond representations simultaneously during message passing.

Inspect and Augment Training Data:

- Symptom: Model consistently generates molecules with strained geometries, even with a correct architecture.

- Action: Apply a data-centric solution by augmenting your training set with distorted molecular conformations. Annotate each molecule (both valid and distorted) with a label representing its structural quality. This conditions the model to recognize and avoid low-quality regions [33].

- Protocol: Use tools like RDKit to systematically generate distorted conformers. Train the model with these annotated examples, using the quality label as a conditioning signal. During sampling, guide the generation toward high-quality labels [33].

Issue: Poor Generated Molecular Properties (Low QED, High SA Score)

Problem: Molecules are chemically valid but do not possess desired drug-like properties.

Diagnosis and Steps for Resolution:

Implement Property Guidance:

- Symptom: Generated molecules have high binding affinity but poor synthetic accessibility or drug-likeness.

- Action: Integrate property guidance into the reverse diffusion process. Do not rely on the model to implicitly learn these from data alone [31].

- Protocol: Use classifier-free guidance. During training, randomly drop the property condition (e.g., QED, SA) to allow the model to learn an unconditional distribution. During sampling, use the guidance scale to push the generation toward the desired property values. The formula for the guided prediction (\hat{\epsilon}) is often: (\hat{\epsilon} = \epsilon{\text{uncond}} + w \cdot (\epsilon{\text{cond}} - \epsilon_{\text{uncond}})) where (w) is the guidance scale that controls the strength of property conditioning [31].

Evaluate with a Comprehensive Metric Suite:

- Action: Move beyond single metrics. Implement a standard evaluation suite to get a holistic view of model performance.

- Protocol: For every generation experiment, calculate the following key metrics as shown in the table below [31].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Generated 3D Molecules

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Quality | Bond/Angle/Dihedral JS Divergence | Measures if the model reproduces realistic distributions of fundamental structural elements. Lower is better [31]. |

| RMSD to Reference | Measures the geometric deviation from a known stable conformation. Lower is better [31]. | |

| Basic Validity | RDKit Validity | Percentage of generated molecules that RDKit can parse as valid chemical structures [33] [31]. |

| PoseBusters Validity (PB-Validity) | Percentage of generated molecules that pass all structural plausibility checks (no clashes, good bond lengths, etc.) [33] [31]. | |

| Molecular Stability | Percentage of molecules where all atoms have correct valency [31]. | |

| Drug-like Properties | Vina Score | Estimated binding affinity to the target protein. More negative is better [31]. |

| QED | Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (0 to 1). Higher is better [31]. | |

| SA Score | Synthetic Accessibility (1 to 10). Lower is easier to synthesize [31]. |

Issue: High Computational Cost and Long Training Times

Problem: Training a model from scratch is prohibitively slow and resource-intensive.

Diagnosis and Steps for Resolution:

- Utilize a Pre-trained Model and Fine-tune:

- Action: Avoid training from scratch. Start with a model pre-trained on large-scale datasets like QM9, GEOM, and drug-like subsets of ZINC [33] [32].

- Protocol: Use frameworks like MolCraftDiffusion, which provide pre-trained weights. For a new task (e.g., conditioned on a specific protein family), you can fine-tune the pre-trained model on a smaller, task-specific dataset, drastically reducing compute time and data requirements [32].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a robust 3D molecular generation workflow that integrates the solutions discussed in this guide, such as bond diffusion and property guidance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for 3D Molecular Generation Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ZINC Database [16] | Small-Molecule Database | A massive collection of commercially available, "drug-like" compounds. Used for pre-training generative models and learning fundamental molecular patterns [33] [16]. |

| QM9 & GEOM Datasets [33] | 3D Molecular Datasets | Standard benchmark datasets containing quantum chemical properties (QM9) and diverse conformers (GEOM). Essential for training and validating 3D generative models [33]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | An open-source toolkit used for critical tasks like parsing SMILES strings, checking molecular validity, generating conformers, and calculating molecular descriptors [33] [31]. |

| EDM / DiffGui Model [33] [31] | Generative Model Framework | EDM is a foundational E(3)-equivariant diffusion model. DiffGui is an advanced extension that integrates bond diffusion and property guidance, serving as a state-of-the-art benchmark and a starting point for new projects [33] [31]. |

| PoseBusters Test Suite [33] | Validation Suite | A specialized tool to check the physical plausibility of generated 3D molecular structures, identifying issues like atomic clashes and incorrect bond lengths [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Mode Collapse in Hybrid GAN-Transformer Models

Problem: The generator produces molecules with low diversity, repeatedly generating a few similar structures.

Explanation: Mode collapse is a known failure state of GANs where the generator fails to explore the full data distribution, instead optimizing for a few modes that fool the discriminator [34] [35]. In a hybrid context, this can be exacerbated if the Transformer's attention mechanism is not properly regularized.

Solution:

- Implement Mini-Batch Discrimination: Modify the discriminator to assess an entire batch of samples rather than individual molecules. This allows it to detect and penalize a lack of diversity in the generator's output, encouraging the generation of a wider range of molecular structures [35].

- Adjust Training Schedule: Use an adaptive training ratio between the generator and discriminator. If the discriminator becomes too strong too quickly, it can overwhelm the generator, leading to collapse. Monitor the loss functions and ensure they remain balanced [34].

- Leverage the VAE Component: Use the probabilistic latent space of the VAE to inject structured noise into the generator's input. The continuous and smooth nature of the VAE's latent space can help the generator explore a broader region of the molecular design space [36] [16].

Guide 2: Mitigating Blurry or Invalid Molecular Output from VAE

Problem: The VAE decoder generates molecules that are structurally invalid (violating chemical rules) or outputs blurry, non-sharp features in their latent representations.

Explanation: The standard VAE loss function, which includes a Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence term, can overly constrain the latent space, leading to a failure in capturing distinct molecular features. This often results in "averaged" or invalid molecular structures [34] [16].

Solution:

- Anneal the KL Loss: Gradually increase the weight of the KL divergence term during training. This allows the encoder to first learn a meaningful mapping to the latent space before being heavily regularized, improving the quality of reconstructions and novel generations [16].

- Incorporate Validity Constraints: Integrate valency checks and other chemical rule-based penalties directly into the decoder's loss function. This guides the model to prioritize chemically plausible structures during generation [36].

- Switch to Graph-Based Representations: If using SMILES strings, consider switching to a graph-based molecular representation. Graphs more naturally encode atom-bond relationships, inherently reducing the probability of generating invalid structures compared to sequence-based models [16].

Guide 3: Managing Unstable Training in Complex Hybrid Architectures

Problem: Training loss oscillates wildly or diverges entirely, making it impossible to converge to a stable solution.

Explanation: Hybrid models combine components with different convergence properties and loss landscapes. The adversarial training of GANs is inherently unstable, and when coupled with the reconstruction loss of a VAE and the complex attention of a Transformer, gradients can become unmanageable [34] [36] [35].

Solution:

- Apply Gradient Penalty (e.g., Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty - WGAN-GP): This replaces the standard GAN discriminator's loss with one that enforces a Lipschitz constraint via a gradient penalty, leading to more stable and reliable training dynamics [35].

- Use a Phased Training Strategy: Do not train all components simultaneously from the start.

- Pre-train the VAE on the molecular dataset to learn a stable initial latent space.

- Pre-train the Transformer on the task of predicting molecular properties from the VAE's latent representations.

- Finally, fine-tune the entire system (VAE, GAN, Transformer) jointly with a lower learning rate [36].

- Implement Gradient Clipping: Cap the magnitude of gradients during backpropagation to prevent explosive updates that can derail training, especially in the Transformer components [34].

Guide 4: Poor Generalization to Unseen Molecular Targets

Problem: The model performs well on training data but fails to generate valid or effective molecules for novel protein targets.

Explanation: The model has overfitted to the specific patterns in its training data and lacks the robustness to handle the diversity of the true biochemical space. This can occur if the training data is insufficiently diverse or the model architecture lacks global reasoning capabilities [37] [36].

Solution:

- Integrate a Transformer for Global Context: Specifically, incorporate a Transformer module after the CNN/VAE feature extractor. The Transformer's self-attention mechanism excels at capturing long-range dependencies within the data, allowing the model to understand complex, non-local relationships between different parts of a molecule or its interaction with a target [37] [38].

- Employ Advanced Data Augmentation: Use techniques like

RandAugandmixupon the molecular feature space to artificially increase the diversity and effective size of your training dataset, forcing the model to learn more robust and generalized features [37]. - Utilize a Morphological Feature Extractor: Design a module that acts like a "domain expert," explicitly highlighting structural features critical for molecular validity and target binding (e.g., pharmacophores, functional groups). This bridges a gap that purely data-driven models might miss [37].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why should I combine a VAE with a GAN instead of using just one? VAEs and GANs have complementary strengths and weaknesses. VAEs are excellent at learning a smooth, structured latent space of the data, which is useful for interpolation and ensuring generated samples are synthetically feasible. However, they often generate blurry or averaged outputs. GANs, conversely, can produce highly realistic and sharp data samples but suffer from training instability and mode collapse. By combining them, you can use the VAE to create a robust latent space and the GAN to refine samples from that space into high-quality, diverse molecular structures [36] [35] [16].

FAQ 2: What is the most computationally expensive part of these hybrid models? The training phase is typically the most resource-intensive. Specifically, the adversarial training process of GANs requires multiple iterations and can be unstable, consuming significant time and compute. Furthermore, the self-attention mechanism in Transformers has a quadratic computational complexity with respect to input size, which becomes very costly when processing large molecular graphs or long sequences [34] [35]. Using window-based attention or sparse transformers can help mitigate this cost.

FAQ 3: How can I quantitatively evaluate the improvement from a hybrid architecture? You should use a combination of metrics tailored to your task:

- For Molecular Validity: Calculate the percentage of generated molecules that are chemically valid (e.g., pass valency checks).

- For Diversity: Use metrics like internal distance (MMD) between generated and training sets.

- For Model Performance: Standard metrics like Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score on a held-out test set are essential. The VGAN-DTI framework, for example, demonstrated the value of its hybrid approach by achieving an F1 score of 94%, a significant improvement over non-hybrid baselines [36].

FAQ 4: My model generates valid molecules, but they don't have the desired drug-like properties. What can I do? Incorporate reinforcement learning (RL) or conditional generation. After the model generates a molecule, use a predictive MLP or another property predictor to score it based on the desired properties (e.g., binding affinity, solubility). You can then use this score as a reward signal to fine-tune the generator (RL) or as a conditioning label during the generation process (conditional GAN/VAE) to steer the model towards regions of the chemical space that possess those properties [36] [16].

The following table summarizes key quantitative results from the cited VGAN-DTI experiment, which combines VAEs and GANs for Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) prediction [36].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the VGAN-DTI Hybrid Model

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGAN-DTI (VAE+GAN+MLP) | 96% | 95% | 94% | 94% |

Experimental Protocol: VGAN-DTI Framework

This protocol details the methodology for replicating the hybrid VAE-GAN architecture as described in the research for DTI prediction [36].

Objective: To predict novel drug-target interactions (DTIs) with high accuracy by generating diverse and valid molecular structures and predicting their binding affinities.

Workflow Overview:

1. Molecular Representation:

- Input: Represent molecules as fingerprint vectors or SMILES strings [36] [16].

- Target: Represent target proteins using sequence or structural descriptors.

2. VAE Component Training:

- Architecture:

- Encoder: A network with 2-3 fully connected hidden layers (e.g., 512 units each) using ReLU activation. The output layer produces the mean (μ) and log-variance (log σ²) of the latent distribution.

- Latent Space: A probabilistic distribution, typically Gaussian. A sample

zis drawn using the reparameterization trick:z = μ + σ * ε, where ε ~ N(0,1). - Decoder: A network mirroring the encoder structure, which reconstructs the input molecular features from the latent sample

z.

- Loss Function: Combine reconstruction loss (e.g., binary cross-entropy) and KL divergence to regularize the latent space.

ℒ_VAE = 𝔼[log p(x|z)] - D_KL[q(z|x) || p(z)][36] [16].

3. GAN Component Training:

- Architecture: