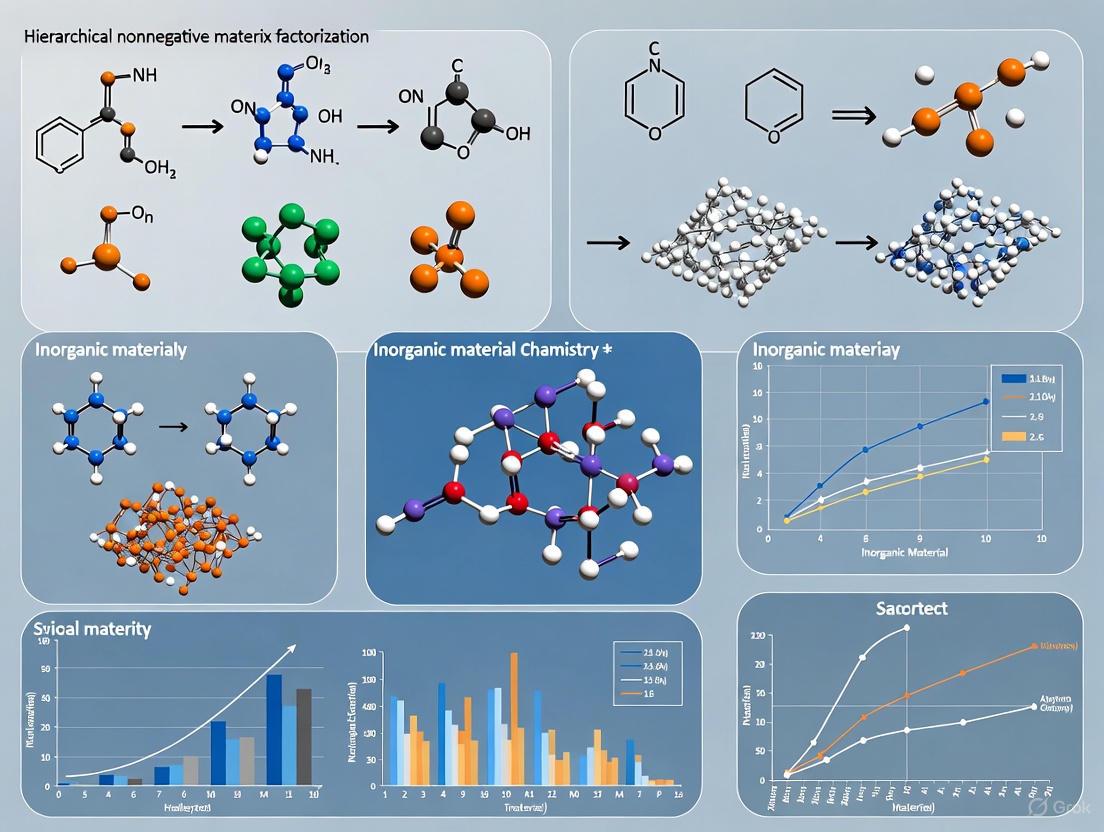

Hierarchical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization: Unraveling Complex Material Structures for Advanced Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Hierarchical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (HNMF), a powerful unsupervised machine learning technique for discerning multi-level structures within complex scientific data.

Hierarchical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization: Unraveling Complex Material Structures for Advanced Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Hierarchical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (HNMF), a powerful unsupervised machine learning technique for discerning multi-level structures within complex scientific data. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we cover foundational principles, methodological implementations across domains like electron microscopy and hyperspectral imaging, and strategies for optimizing performance and mitigating artifacts. The content further addresses critical validation and comparative analysis with other dimensionality reduction techniques, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for applying HNMF to accelerate discovery in materials science and biomedical research.

What is Hierarchical NMF? Core Principles and Advantages for Materials Science

Modern materials characterization techniques, particularly four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy (4D-STEM), generate extremely large datasets that capture complex, hierarchical material structures [1] [2]. These datasets contain information spanning multiple scales—from atomic arrangements to mesoscale precipitates and domain structures. Conventional flat dimensionality reduction techniques, such as principal component analysis (PCA) and basic nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF), prove insufficient for extracting these nested hierarchical relationships [2]. They often produce mathematically valid but physically implausible components with negative intensities or unrealistic downward-convex peaks that violate fundamental electron microscopy physics [2].

Hierarchical nonnegative matrix factorization (HNMF) addresses these limitations by recursively applying NMF to discover overarching topics encompassing lower-level features [3]. This approach mirrors the natural hierarchical organization found in material systems, where atomic-scale patterns form nanoscale precipitates, which subsequently organize into larger microstructural features. By framing hierarchical NMF as a neural network with backpropagation optimization, researchers can learn meaningful hierarchical structures that illustrate how fine-grained topics relate to coarse-grained themes [3]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding complex material phenomena where different levels of structural organization directly influence material properties and performance.

The Limitations of Conventional Analysis Methods

Traditional flat analysis methods suffer from significant limitations when applied to complex materials data:

Physical Interpretability Challenges

Conventional NMF produces sparse components that may not align with physical reality [2]. When experimental results consist of continuous intensity profiles with additional sharp peaks—common in scientific measurements—primitive NMF introduces downward-convex peaks (unnatural intensity drops) that represent known artifacts rather than true physical signals [2]. These mathematical artifacts misrepresent the actual material structure and can lead to incorrect interpretations.

Handling of Spectral Variability

In hyperspectral imaging and 4D-STEM, endmember variability presents a significant challenge [4]. The linear mixing model assumes a single spectrum fully characterizes each material class, but in reality, spectral signatures vary due to illumination conditions, intrinsic variability, and measurement artifacts [4]. Flat decomposition methods cannot adequately represent this variability, leading to oversimplified representations that lose critical information about material heterogeneity.

Multi-Scale Analysis Limitations

Complex materials exhibit relevant features at multiple scales simultaneously. Metallic glasses containing nanometer-sized crystalline precipitates exemplify this challenge, requiring analysis methods that can detect and classify features across spatial resolutions [1]. Conventional approaches analyze each scale separately, missing important cross-scale relationships that determine material behavior.

Table 1: Comparison of Analysis Methods for Complex Materials Data

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Efficient dimensionality reduction; Established algorithms | Negative intensities physically impossible in electron microscopy; Limited interpretability | Initial data exploration; Noise reduction |

| Basic Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) | Nonnegative components; Parts-based representation | Artifacts with downward-convex peaks; Cannot represent hierarchies | Document clustering; Simple spectral unmixing |

| Hierarchical NMF (HNMF) | Multi-scale representation; Physically interpretable components; Captures nested structures | Higher computational complexity; More parameters to tune | Metallic glass precipitates; Microbial communities; Topic hierarchies |

Hierarchical NMF Framework for Materials Science

Theoretical Foundation

Hierarchical NMF recursively applies matrix factorization to create layered representations of complex data. Given a nonnegative data matrix X ∈ ℝ₊^(N×M), single-layer NMF approximates it as the product of two nonnegative matrices X ≈ AS, where A ∈ ℝ₊^(N×K) contains basis components and S ∈ ℝ₊^(K×M) contains coefficients [3]. Hierarchical NMF extends this by recursively factorizing the coefficient matrix:

X ≈ A^(1)S^(1) S^(1) ≈ A^(2)S^(2) ... S^(L-1) ≈ A^(L)S^(L)

The resulting approximation is X ≈ A^(1)A^(2)⋯A^(L)S^(L), with the final basis matrix given by A = A^(1)A^(2)⋯A^(L) [3]. This cascaded structure naturally represents hierarchical relationships in material systems.

Domain-Specific Constraints for Materials Data

Incorporating domain knowledge is crucial for physically meaningful factorization. For electron microscopy data, constraints include spatial resolution preservation and continuous intensity features without downward-convex peaks [2]. These constraints eliminate physically implausible components that violate the fundamental principle that detected electron counts cannot be negative. The integration of domain-specific knowledge effectively mitigates artifacts found in conventional machine learning techniques that rely solely on mathematical constraints [2].

Multi-Layer Architecture

Neural NMF implements hierarchical factorization using a multi-layer architecture similar to neural networks [3]. This approach enables:

- Backpropagation optimization across layers

- Improved hierarchical structure learning

- Better inter-layer relationships

- Enhanced topic interpretability

The neural framework allows for supervised extension where label information guides the factorization process, improving the separation of relevant material features [3].

Experimental Protocols for Hierarchical Materials Analysis

Protocol 1: HNMF for Metallic Glass Precipitate Analysis

Objective: Detect and classify nanometer-sized crystalline precipitates embedded in amorphous metallic glass (ZrCuAl) using 4D-STEM data [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Four-dimensional STEM instrument

- Metallic glass sample (ZrCuAl system)

- High-performance computing workstation

- DigitalMicrograph software with custom HNMF scripts [2]

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Collect 4D-STEM dataset I₄D(x,y,u,v) where (x,y) are real-space coordinates and (u,v) are reciprocal-space coordinates [2].

- Data Transformation: Reshape 4D data into 2D matrix X ∈ ℝ₊^(Nuv×Nxy) where rows correspond to diffraction patterns and columns to spatial positions [2].

- Constraint Definition: Implement domain-specific constraints including:

- Spatial smoothness constraints for real-space maps

- Continuous intensity profile constraints for diffraction patterns

- Non-negativity constraints for all components [2]

- Hierarchical Factorization:

- Set the hierarchy levels (typically 2-3 for material systems)

- Initialize A^(1), A^(2), ..., A^(L) with positive random values

- Apply multiplicative update rules with domain constraints [2]: A^(ℓ) ← A^(ℓ) ⊛ (X(S^(ℓ))ᵀ) ⊘ (A^(ℓ)S^(ℓ)(S^(ℓ))ᵀ) S^(ℓ) ← S^(ℓ) ⊛ ((A^(ℓ))ᵀX) ⊘ ((A^(ℓ))ᵀA^(ℓ)S^(ℓ))

- Hierarchical Clustering: Apply polar coordinate transformation and uniaxial cross-correlation to cluster diffraction patterns by similarity [1].

- Precipitate Identification: Identify crystalline precipitates through analysis of factorized diffraction components and their spatial distributions [1].

Expected Outcomes: Successful decomposition will yield interpretable diffractions and maps that reveal precipitate structures not achievable with PCA or primitive NMF [1].

Protocol 2: Bayesian Hierarchical NMF for Microbial Communities

Objective: Analyze microbial metagenomic data to discover underlying community structures and their associations with environmental factors [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Microbial abundance data (OTU table)

- Host environmental factor data

- BALSAMICO software package

- R statistical computing environment

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Format microbial abundance data as nonnegative matrix Y ∈ ℝ₊^(N×K) where N is samples and K is taxa [5].

- Model Specification: Implement hierarchical Bayesian model:

- hl ∼ Dirichlet(α) (community abundance profiles)

- B = exp(-XV) (environmental factor effects)

- w(n,l) ∼ Gamma(aw, B(n,l)) (community contributions)

- t(n,l) ∼ Poisson(w(n,l)τn) (latent counts)

- s(n,l) ∼ Multinomial(t(n,l), hl) (species assignments)

- y(n,k) = ∑(l=1)^L s_(n,l,k) (observed abundances) [5]

- Variational Inference: Estimate parameters W, H, a_w, and V using variational Bayesian inference [5].

- Hierarchical Structure Analysis: Examine the relationship between environmental factors and community structures through the estimated V matrix [5].

- Community Detection: Identify key microbial communities associated with specific environmental conditions or disease states.

Expected Outcomes: Accurate detection of bacterial communities related to specific conditions (e.g., colorectal cancer) with estimation of uncertainty through credible intervals [5].

Visualization of Hierarchical NMF Workflows

Diagram 1: Hierarchical NMF Workflow for Materials Data. This workflow illustrates the sequential factorization process from raw 4D-STEM data to hierarchical structure identification.

Diagram 2: Constraint Integration in Hierarchical NMF. The diagram shows how mathematical, physical, and domain-specific constraints are integrated to produce physically meaningful factorizations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Hierarchical NMF

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 4D-STEM Instrumentation | Acquires four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy data | Metallic glass precipitate analysis [1] [2] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging Systems | Captures spatial and spectral information simultaneously | Mineral identification; Phase mapping [4] |

| DigitalMicrograph with Custom Scripts | Implements HNMF algorithms with domain-specific constraints | Electron microscopy data analysis [2] |

| BALSAMICO Software Package | Bayesian latent semantic analysis of microbial communities | Microbial community analysis with environmental factors [5] |

| Neural NMF Framework | Implements hierarchical NMF as neural network with backpropagation | Multi-layer topic modeling; Hierarchical feature extraction [3] |

| scikit-learn NMF Implementation | Provides standard NMF algorithms (multiplicative updates, ALS) | Baseline comparisons; Preliminary analysis [2] |

Hierarchical nonnegative matrix factorization represents a paradigm shift in the analysis of complex materials data by moving beyond flat structures to embrace the multi-scale nature of material systems. By incorporating domain-specific constraints and leveraging recursive factorization, HNMF enables researchers to extract physically meaningful hierarchical structures from 4D-STEM, hyperspectral imaging, and other advanced characterization techniques. The experimental protocols and tools outlined in this application note provide a foundation for implementing hierarchical analysis approaches that can reveal previously hidden relationships in complex materials data, ultimately accelerating materials discovery and development.

Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) is a cornerstone unsupervised learning technique for parts-based representation and dimensionality reduction across diverse scientific domains. In its fundamental form, NMF factorizes a given non-negative data matrix X into two lower-rank, non-negative matrices W (basis matrix) and H (coefficient matrix) such that X ≈ WH [2] [3]. The nonnegativity constraint fosters intuitive, additive combinations of features, enabling a more interpretable parts-based representation compared to other matrix factorization methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [3]. This mathematical framework finds extensive application in topic modeling, feature extraction, and hyperspectral imaging, particularly within materials science research where interpreting underlying physical components is paramount [2] [3].

Hierarchical NMF (HNMF) extends this core concept by recursively applying factorization to learn latent topics or features at multiple levels of granularity [3]. This multi-layer approach captures overarching themes encompassing lower-level features, thereby illuminating the hierarchical structure inherent in many complex datasets [6] [3]. Unlike standard hierarchical clustering, which forcibly imposes structure, HNMF naturally discovers these relationships, avoiding Procrustean behavior [7]. Within materials research, this capability is invaluable for deciphering complex structure-property relationships, such as identifying hierarchical microstructural features from electron microscopy data or linking multi-scale material characteristics to performance metrics [2].

Fundamental NMF Algorithms and Mathematical Foundations

Core Mathematical Principles

The NMF optimization problem aims to find non-negative matrices W ∈ ℝ⁺^{m×k} and H ∈ ℝ⁺^{k×n} that minimize the reconstruction error for a given data matrix X ∈ ℝ⁺^{m×n}. Formally [3]:

The rank k is chosen such that (n+m)k < nm, ensuring a lower-dimensional representation [7]. The solution provides a parts-based decomposition where the columns of W represent fundamental components (e.g., topics in text, spectral profiles in microscopy), and H contains the coefficients to reconstruct each data point via additive combinations of these components [3].

Standard Optimization Algorithms

Two primary algorithmic approaches dominate NMF implementations:

Table 1: Core NMF Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Update Rules | Key Characteristics | Common Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplicative Update (MU) | W ← W ⊛ (XHᵀ) ⊘ (WHHᵀ)H ← H ⊛ (WᵀX) ⊘ (WᵀWH) | Element-wise operations (⊛, ⊘)Maintains nonnegativity automaticallyPart of majorization-minimization framework [2] | MATLAB ('mult' in nnmf)scikit-learn ('mu' in NMF) [2] |

| Alternating Least Squares (ALS) | W ← [(XHᵀ)(HHᵀ)⁻¹]₊H ← [(WᵀW)⁻¹(WᵀX)]₊ | Solves nonnegative least squares alternatelyProjection [·]₊ = max{0,·} enforces nonnegativityMore flexible for constraints [2] | MATLAB ('als' in nnmf)scikit-learn ('cd' in NMF) [2] |

The convergence of these algorithms is typically monitored using cost functions based on the Frobenius norm ‖X - WH‖₂² or the Kullback-Liebler divergence [2] [7]. A critical challenge with primitive NMF is its tendency to produce sparse components that may not align with physical reality, sometimes generating implausible artifacts like downward-convex peaks in continuous intensity profiles [2].

Advanced Hierarchical NMF Frameworks

Neural NMF for Hierarchical Multilayer Topic Modeling

Neural NMF represents a significant advancement by framing hierarchical factorization within a neural network architecture. This approach recursively applies NMF across multiple layers to discover relationships between topics at different granularity levels [6] [3]. The forward propagation process can be represented as:

where each layer ℓ progressively captures more abstract representations. A key innovation of Neural NMF is its derivation of a backpropagation-style optimization scheme that jointly learns all layer parameters, substantially reducing approximation error compared to sequential HNMF application [3]. This method has demonstrated superior performance in learning interpretable hierarchical topic structures on document datasets (20 Newsgroups) and biomedical data (MyLymeData symptoms), outperforming other HNMF methods in both reconstruction accuracy and classification performance [3].

Deep Non-negative Matrix Factorization (Deep-NMF)

Deep-NMF extends the hierarchical concept further through multiple layers of decomposition to learn non-linear parts-based representations [8]. Unlike semi-NMF frameworks that allow negative values, Deep-NMF maintains strict nonnegativity, preserving the intuitive parts-based interpretation crucial for scientific applications [8]. This approach has shown particular promise in multi-view clustering, where it simultaneously decomposes data from multiple sources or perspectives through a shared hierarchical structure. The Deep-NMF framework can be enhanced with manifold learning techniques that preserve the intrinsic geometric structure of data across all layers, ensuring that local neighborhood relationships are maintained in the learned representations [8].

Orthogonal Diverse Deep NMF (ODD-NMF)

The ODD-NMF framework incorporates several crucial constraints to enhance multi-view learning [8]:

- Orthogonal Constraints: Applied via normalized cut-type relaxation to ensure learning of unique, complementary information from each view

- Diversity Constraints: Enhance learning of diverse information across view pairs in the low-rank representations

- Optimal Manifold Integration: Preserves the most consensed geometric structure across all layers

This combination effectively learns both view-shared and view-specific information, producing more meaningful clusters in complex datasets such as multi-view text and image collections [8].

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Experimental Protocol for Constrained NMF in Electron Microscopy

Modern scientific instruments like 4D-Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (4D-STEM) generate extremely large datasets requiring specialized NMF approaches [2]. The following protocol outlines the application of domain-aware constrained NMF for materials characterization:

Table 2: Protocol for 4D-STEM Data Analysis via Constrained NMF

| Step | Procedure | Parameters | Domain-Specific Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Preparation | Transform 4D data I₄D(x,y,u,v) to matrix XReshape 2D diffractions I₂D(u,v) to 1D column vectors | nₓy = nₓny, nᵤv = nᵤnv [2] | Maintain spatial relationships between real and reciprocal spaces |

| 2. Initialization | Initialize W and H with non-negative valuesSet number of components nₖ (nₖ << nₓy) | W ∈ ℝ⁺^{nᵤv×nₖ}H ∈ ℝ⁺^{nₖ×nₓy} [2] | Incorporate physical prior knowledge where available |

| 3. Constrained Factorization | Apply MU or ALS updates with embedded constraints | Monitor convergence via ‖X - WH‖₂² [2] | Enforce:• Spatial smoothness in H maps• Continuous intensity profiles in W diffractions• No downward-convex peaks [2] |

| 4. Component Interpretation | Transform W columns to 2D diffractions wₖ(u,v)Reshape H rows to 2D maps hₖ(x,y) | k = 0,1,...,nₖ-1 [2] | Relate components to physical structures• Crystalline precipitates• Amorphous phases• Defect regions |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for HNMF Research

| Tool Name | Environment/Language | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn | Python | NMF implementations ('mu', 'cd')Model evaluation utilities [2] | General machine learning pipeline integration |

| HyperSpy | Python | Multi-dimensional data analysisSignal processing for microscopy [2] | Electron microscopy data analysis |

| DigitalMicrograph | Gatan Inc. proprietary | MU/ALS NMF scripts [2] | In-situ STEM data processing |

| BALSAMICO | R | Bayesian NMF with clinical covariate integration [5] | Microbial community analysis with environmental factors |

| ODD-NMF | MATLAB | Deep multi-view clustering with orthogonal constraints [8] | Multi-view data integration |

Domain-Specific Applications in Materials and Biomedical Research

Materials Characterization via 4D-STEM

The application of constrained NMF to 4D-STEM data has demonstrated remarkable success in extracting physically interpretable components from complex nanoscale phenomena [2]. In a notable study analyzing ZrCuAl metallic glass, domain-constrained NMF successfully identified and classified nanometer-sized crystalline precipitates embedded within the amorphous matrix by decomposing both simulated and experimental data into interpretable diffractions and maps [2]. This approach overcame critical limitations of PCA and primitive NMF, which produced physically implausible results with negative intensities or artifact-laden components. The integration of domain knowledge—specifically spatial resolution constraints and continuous intensity profile characteristics—proved essential for generating scientifically meaningful decompositions [2].

Biomedical Applications

HNMF methods have shown significant utility in biomedical domains, particularly for analyzing complex, high-dimensional biological data. The BALSAMICO framework exemplifies this application, employing a hierarchical Bayesian NMF approach to model microbial communities and their associations with clinical factors [5]. This method effectively identified bacteria related to colorectal cancer by decomposing microbial abundance data while incorporating clinical covariates, demonstrating how hierarchical factorization can reveal relationships between microbial community structures and disease states [5].

Critical Implementation Considerations

Rank Selection Methodologies

Determining the optimal number of components (k) remains a fundamental challenge in NMF applications. Several methods have been evaluated for estimating k in synthetic and empirical data [7]:

- Brunet's Cophenetic Correlation Coefficient: Measures stability of clustering assignments across multiple runs

- Velicer's Minimum Average Partial (MAP): Originally developed for factor analysis, adapted for NMF

- Minka's Laplace-PCA: Bayesian model selection approach

- Euclidean Distance Reduction Analysis: Examines reconstruction error versus complexity trade-off

Research indicates that when underlying components are orthogonal, PCA-based methods and Brunet's approach achieve highest accuracy [7]. However, normalization techniques can unpredictably affect rank estimation, suggesting that unnormalized data may provide more reliable component number estimates [7].

Hierarchical Component Relationships

A key advantage of hierarchical NMF methods is their ability to illustrate relationships between topics learned at different granularity levels without requiring multiple separate NMF runs [3]. This hierarchical representation immediately reveals how finer-grained topics relate to broader thematic categories, providing valuable insights into the latent structure of complex datasets. In materials research, this capability enables multi-scale characterization, linking atomic-scale features to microstructural domains and ultimately to macroscopic material properties.

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Hierarchical NMF Conceptual Framework

Hierarchical NMF Framework: Illustrating the multi-layer decomposition process where each layer factorizes the coefficient matrix from the previous layer.

Domain-Constrained NMF for Materials Science

Domain-Constrained NMF Workflow: Demonstrating the integration of physical constraints into the NMF process for scientifically interpretable results in materials characterization.

Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) is a powerful unsupervised learning technique for parts-based representation and dimensionality reduction. By decomposing a non-negative data matrix into two lower-dimensional, non-negative factor matrices, NMF provides intuitive and interpretable latent features. Recent advancements have extended this core methodology into more sophisticated frameworks—Multi-layer NMF, Neural NMF, and Constrained NMF—which offer enhanced hierarchical representation, deep learning integration, and incorporation of prior knowledge, respectively. These algorithms are pivotal in modern materials research and drug development, enabling researchers to uncover complex, hierarchical patterns in high-dimensional data. This note details the key algorithms, their experimental protocols, and applications.

Key Algorithm Specifications and Comparisons

The table below summarizes the core architectures, optimization methods, and primary applications of three advanced NMF algorithms.

Table 1: Specification and Comparison of Key NMF Algorithms

| Algorithm Name | Core Architecture & Model | Optimization Method | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-layer NMF [9] [3] | Cascaded decomposition: V ≈ A(1)A(2)...A(L)X(L)• Key Parameters: Number of layers (L), ranks (k(1), k(2), ..., k(L)) |

• Multiplicative Update• Backpropagation-style• Inspired by physical chemistry (e.g., Boltzmann probability for convergence) [9] | • Hierarchical topic modeling [3]• Crystal orientation mapping in 4D-STEM [10]• Cardiorespiratory disease clustering [9] |

| Neural NMF [3] | Framed as a neural network with L layers.• Key Parameters: Ranks per layer (k(ℓ)), regularization parameters (μ, λ) |

• Alternating Multiplicative Updates• Gradient Descent via backpropagation [3] | • Hierarchical multilayer topic modeling [3]• Document classification (e.g., 20 Newsgroups) [3]• Biomedical symptom analysis (e.g., MyLymeData) [3] |

| Constrained NMF (DSNMF) [11] | Standard NMF with added regularization terms.• Key Parameters: Decomposition rank (k), regularization coefficients (λ1, λ2) for pointwise and pairwise constraints | • Alternating Multiplicative Updates• Graph and Label Regularization [11] | • Multi-view data clustering [11]• Image clustering (e.g., COIL20, LandUse21) [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hierarchical Material Analysis using Neural NMF

This protocol outlines the application of Neural NMF for extracting hierarchical structure from 4D-STEM data for crystal orientation mapping [3] [10].

- Objective: To determine the optimal number of hierarchical components (clusters) and their relationships in a 4D-STEM dataset.

- Materials and Data Preprocessing:

- Input Data: A 4D-STEM dataset, which is a four-dimensional array (x, y, diffraction pattern x, diffraction pattern y) [10].

- Preprocessing: Convert the 4D dataset into a 2D matrix

Vof size (number of pixels per diffraction pattern × number of probe positions). Apply data reduction and noise reduction techniques to handle the inherent sparsity of diffraction patterns [10].

- Procedure:

- Initialization: Specify the number of layers

Land the rank (number of components/topics) for each layer,k(1),k(2), ...,k(L). Initialize the factor matricesA(1),A(2), ...,A(L), andX(L)with non-negative values, potentially using nonnegative double singular value decomposition (NNDSVD) for stability [3] [12]. - Forward Propagation (Neural NMF Model): Execute the layered decomposition:

V ≈ A(1) * A(2) * ... * A(L) * X(L)The output of one layer serves as the input for the next [3]. - Backward Propagation (Optimization): Minimize the total reconstruction error

||V - A(1)A(2)...A(L)X(L)||²using an alternating optimization scheme. For Neural NMF, this involves calculating gradients with respect to all factor matrices and updating them iteratively, similar to backpropagation in neural networks [3]. - Stopping Criterion: Iterate until the change in the reconstruction error falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 1e-6) or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

- Component and Cluster Analysis:

- Use the

K-component lossmethod combined with Image Quality Assessment (IQA) metrics to evaluate the quality of the decomposition for different values ofkand select the optimal number of components [10]. - Analyze the basis matrix

W(the product ofAmatrices) for spectral templates and the coefficient matrixH(X(L)) for their activations to generate spatial distribution maps of different crystal orientations [10].

- Use the

- Initialization: Specify the number of layers

- Troubleshooting: High reconstruction error may indicate an incorrect choice of ranks; reevaluate using the K-component loss method. Uninterpretable components may suggest a need for increased sparsity constraints or improved data preprocessing [10].

Protocol 2: Multi-view Data Integration using Dual Constraint NMF (DSNMF)

This protocol describes using DSNMF for clustering multi-view data by leveraging limited supervisory information [11].

- Objective: To perform clustering on multi-view data by effectively integrating both pointwise and pairwise constraints into the NMF framework.

- Materials and Data Preprocessing:

- Input Data: Multiple feature matrices

{X(1), X(2), ..., X(V)}fromVdifferent views, representing the same set ofndata points. A small set of known labels for partial data. - Preprocessing: Normalize each view's data matrix. Construct a binary label matrix

Yfrom the available labels. Calculate similarity matricesS_dandS_efor drugs/diseases or data points within each view [13] [11].

- Input Data: Multiple feature matrices

- Procedure:

- Multi-view Dual Constraint (MDC) Algorithm: For each view, use the limited label information to:

- Model Formulation: Solve the DSNMF optimization problem, which integrates graph and label regularization [11]:

min ||X - USV^T||² + α||U||² + β||V||² + λ( Tr(S^T L S) ) + μ( Pointwise Constraint Term )whereLis the graph Laplacian derived from the similarity matrices. - Optimization: Use an alternating multiplicative update algorithm to iteratively solve for the factor matrices

U,S, andVuntil convergence [11]. - Clustering: Apply a classical clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means) to the learned consensus representation

Sor use the label matrix directly for classification to obtain the final clusters [11].

- Validation: Use ground-truth labels to compute clustering metrics like Accuracy, Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI). Conduct cross-validation to assess robustness [11].

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Hierarchical NMF Decomposition Workflow

Dual Constraint NMF Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for NMF Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 4D-STEM Datasets [10] | Raw input data for hierarchical structure analysis in materials science. Contains spatial and diffraction information. | Identifying crystal orientations and phases in polycrystalline materials [10]. |

| Multi-view Datasets (e.g., COIL20, LandUse21) [11] | Benchmark datasets comprising the same objects from multiple views or feature sets. | Testing and validating multi-view clustering algorithms like DSNMF [11]. |

| Gold-Standard Association Datasets (e.g., Cdataset, Fdataset) [13] [14] | Curated matrices of known associations (e.g., drug-disease, virus-drug). | Training and benchmarking predictive models for computational drug repositioning [13] [14]. |

| Similarity/Networks (Drug/Disease Similarity) [13] [14] | Precomputed matrices capturing functional or semantic relationships between entities. | Incorporated as graph regularization terms in constrained NMF to guide factorization [13]. |

| NMF Software Packages (R, Python Nimfa) [15] | Open-source libraries providing optimized implementations of various NMF algorithms. | Rapid prototyping, testing, and deployment of NMF models in research [15]. |

Hierarchical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (HNMF) represents a significant advancement in the analysis of complex materials science data. By decomposing a non-negative data matrix into multiple layers of latent features, HNMF moves beyond standard NMF to uncover intricate 'parts-of-parts' structures inherent in material systems. This hierarchical approach provides materials scientists with an unparalleled interpretability advantage, enabling the dissection of multi-scale phenomena—from atomic-scale interactions in electron microscopy data to compositional variations in microbial communities affecting material biosynthesis.

The core mathematical principle of NMF involves approximating a data matrix ( \mathbf{X} ) as the product of two lower-rank, non-negative matrices: ( \mathbf{X} \approx \mathbf{WH} ) [2]. HNMF extends this framework by imposing additional structural constraints or further factorizing the components matrices, creating a hierarchy that reveals how broader patterns are composed of finer, constituent sub-patterns. This is particularly powerful for materials research, where properties emerge from interactions across different spatial and compositional scales. Unlike methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) that often yield components with physically unrealistic negative intensities, HNMF ensures all decomposed components maintain non-negativity, resulting in physically plausible and directly interpretable features such as diffraction patterns, elemental maps, or community structures [2] [5].

Theoretical Foundations: From Standard NMF to Hierarchical Decomposition

The Primitive NMF Framework

Standard NMF algorithms aim to minimize a cost function, typically the Frobenius norm of the reconstruction error: [ D(\mathbf{X} \| \mathbf{WH}) = \frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf{X} - \mathbf{WH}\|F^2 ] This is achieved through iterative update procedures, with two common approaches being the Multiplicative Update (MU) and Alternating Least Squares (ALS) algorithms [2]. The MU algorithm updates the matrices via elementwise operations: [ \mathbf{W} \leftarrow \mathbf{W} \circledast \mathbf{XH}^T \oslash \mathbf{WHH}^T ] [ \mathbf{H} \leftarrow \mathbf{H} \circledast \mathbf{W}^T\mathbf{X} \oslash \mathbf{W}^T\mathbf{WH} ] where ( \circledast ) and ( \oslash ) denote elementwise multiplication and division, respectively. The ALS algorithm, on the other hand, employs a projection-based approach: [ \mathbf{W} \leftarrow [(\mathbf{XH}^T)(\mathbf{HH}^T)^{-1}]+ ] [ \mathbf{H} \leftarrow [(\mathbf{W}^T\mathbf{W})^{-1}(\mathbf{W}^T\mathbf{X})]+ ] where ( [\cdot]+ ) represents the nonnegativity constraint projection [2].

Incorporating Domain Knowledge through Constraints

While mathematically sound, primitive NMF can produce artifacts that contradict domain knowledge, such as downward-convex peaks in continuous intensity profiles or high-frequency noise interpreted as signal [2]. This limitation is particularly problematic in materials characterization techniques like electron microscopy, where signals must adhere to specific physical constraints.

Constrained NMF addresses this by integrating domain-specific knowledge directly into the factorization process. For 4D-STEM data, this includes incorporating knowledge about spatial resolution and continuous intensity features, yielding decomposed components that are not only mathematically valid but also physically interpretable [2]. This philosophy of adding constraints forms the foundation for more complex hierarchical models.

The Hierarchical Extension

Hierarchical NMF frameworks introduce additional layers of decomposition, often through Bayesian probabilistic models or sequential factorization. The BALSAMICO framework, for instance, models microbiome data using a hierarchical structure where the factor matrices themselves are influenced by external covariates [5]: [ \mathbf{W} \approx a_w \exp(\mathbf{XV}) ] Here, the contribution matrix ( \mathbf{W} ) is governed by clinical covariates ( \mathbf{X} ) and their coefficients ( \mathbf{V} ), creating a hierarchy where observed environmental factors influence the latent communities, which in turn explain the observed data [5]. This approach successfully detected bacteria related to colorectal cancer, demonstrating its power to uncover meaningful biological structures with direct clinical relevance.

Table 1: Comparison of NMF Variants for Materials Research

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive NMF | Non-negative factors, sparsity | Simple implementation, physically plausible components | May produce artifacts; no domain knowledge | Initial data exploration, basic feature extraction |

| Constrained NMF | Domain-specific constraints | Physically interpretable results, removes artifacts | Requires domain expertise to define constraints | 4D-STEM analysis, hyperspectral imaging |

| Hierarchical NMF | Multi-layer decomposition, incorporation of covariates | Reveals 'parts-of-parts' structures, models complex relationships | Computationally intensive, complex implementation | Microbial communities, multi-scale materials analysis |

Application Notes: HNMF for 4D-STEM Data Analysis in Metallic Glasses

Experimental Background and Data Preparation

Four-dimensional Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (4D-STEM) represents a cutting-edge characterization technique that generates massive datasets containing bimodal information from both real and reciprocal spaces [2]. Each 4D dataset ( \mathbf{I}{4D}(x, y, u, v) ) consists of 2D electron diffractions ( \mathbf{I}{2D}(u, v) ) acquired at varying probe positions ( (x, y) ), where ( (u, v) ) and ( (x, y) ) are reciprocal and real-space coordinates, respectively.

To apply HNMF, the 4D data must first be transformed into an appropriate matrix representation. The 2D experimental diffractions ( \mathbf{I}{2D}(u, v) ) are reshaped into one-dimensional column vectors, forming the matrix ( \mathbf{X} ), where rows correspond to reciprocal-space coordinates and columns correspond to real-space coordinates [2]. For data points of size ( (nx, ny, nu, nv) ) and an assumed number of components ( nk ), the matrix dimensions become ( \mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{n{uv} \times n{xy}} ), where ( n{xy} = nx ny ) and ( n{uv} = nu nv ).

Workflow for Hierarchical Decomposition

The following diagram illustrates the complete HNMF workflow for analyzing 4D-STEM data from metallic glasses, from data acquisition through hierarchical decomposition:

Constrained Factorization Protocol

The hierarchical decomposition begins with a constrained NMF step that incorporates electron microscopy domain knowledge:

Initialization: Initialize matrices ( \mathbf{W} ) and ( \mathbf{H} ) with non-negative random values or using smart initialization algorithms.

Multiplicative Updates with Constraints: Implement the MU algorithm while applying domain-specific constraints:

- Spatial Smoothing Constraint: Apply Gaussian filtering to the columns of ( \mathbf{H} ) (real-space maps) between iterations to enforce realistic spatial continuity.

- Intensity Profile Constraint: Apply median filtering to the rows of ( \mathbf{W} ) (diffraction patterns) to eliminate physically implausible downward-convex peaks while preserving sharp diffraction features.

Convergence Monitoring: Iterate until the relative change in the cost function falls below a threshold (typically ( 10^{-6} )) or until a maximum number of iterations is reached.

Hierarchical Decomposition: Take the resulting matrix ( \mathbf{W}1 ) and apply a second NMF decomposition: ( \mathbf{W}1 \approx \mathbf{W}2 \mathbf{H}2 ), revealing the sub-structure within the primary components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for HNMF in Materials Science

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 4D-STEM Dataset | Primary experimental data | Pre-process: flat-field correction, background subtraction |

| Constrained NMF Algorithm | Core decomposition engine | Implement MU or ALS with domain constraints |

| Spatial Smoothing Filter | Enforces realistic spatial continuity in maps | Gaussian kernel with σ = 1-2 pixels |

| Intensity Profile Filter | Removes unphysical intensity artifacts | Median filter with 3×3 kernel |

| Hierarchical Clustering | Classifies decomposed components | Polar coordinate transformation + cross-correlation |

| DigitalMicrograph Script | Execution environment for electron microscopists | Gatan Inc. platform with custom HNMF scripts |

Results Interpretation and Precipitate Classification

Applying this HNMF protocol to ZrCuAl metallic glass data successfully decomposes both simulated and experimental 4D-STEM data into physically interpretable diffractions and maps that cannot be achieved using PCA or primitive NMF [2]. The hierarchical decomposition reveals nanometer-sized crystalline precipitates embedded within the amorphous matrix, with the 'parts-of-parts' structure showing how different precipitate types share common sub-structural motifs.

For classification, hierarchical clustering is optimized based on diffraction similarity using a combination of polar coordinate transformation and uniaxial cross-correlation [2]. This enables precise classification of precipitates according to their diffraction patterns, demonstrating HNMF's capability to detect and categorize subtle structural features that would remain hidden in conventional analysis.

Advanced Protocol: Bayesian HNMF for Complex Material Systems

Theoretical Framework for Bayesian HNMF

For more complex material systems with external covariates or prior knowledge, a Bayesian hierarchical approach provides a powerful extension to standard HNMF. The BALSAMICO framework offers a template for such an approach, modeling the data generation process as [5]: [ \mathbf{h}l \sim \text{Dirichlet}(\boldsymbol{\alpha}) ] [ \mathbf{B} = \exp(-\mathbf{XV}) ] [ w{n,l} \sim \text{Gamma}(aw, B{n,l}) ] [ t{n,l} \sim \text{Poisson}(w{n,l} \taun) ] [ \mathbf{s}{n,l} \sim \text{Multinomial}(t{n,l}, \mathbf{h}l) ] [ y{n,k} = \sum{l=1}^{L} s{n,l,k} ] where ( \mathbf{X} ) represents covariates, ( \mathbf{V} ) their coefficients, ( \taun ) is an offset term, and ( \mathbf{S} = {s_{n,l,k}} ) are latent variables introduced to facilitate inference [5].

Implementation Workflow

The Bayesian HNMF implementation involves the following steps:

Model Specification: Define the hierarchical structure based on domain knowledge, identifying which covariates should influence which levels of the decomposition.

Variational Inference: Implement an efficient variational Bayesian inference procedure to estimate parameters, using Laplace approximation to reduce computational cost.

Posterior Analysis: Examine the posterior distributions of the parameters to identify significant relationships between covariates and latent components.

Validation: Use synthetic data with known ground truth to validate the accuracy of parameter estimation before applying to experimental data.

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical Bayesian structure for modeling complex relationships in material systems:

Application to Microbial-Material Systems

In an analysis of clinical metagenomic data, the BALSAMICO framework successfully detected bacteria related to colorectal cancer, demonstrating its power to uncover meaningful biological structures with direct clinical relevance [5]. For materials research, similar approaches can be applied to systems where microbial communities interact with material surfaces, or in the study of biomaterials where biological and material factors jointly determine performance.

Comparative Analysis and Implementation Guidelines

Performance Comparison Across Domains

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of HNMF Across Application Domains

| Application Domain | Data Type | Comparison Methods | Key HNMF Advantages | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4D-STEM of Metallic Glasses | Electron diffraction patterns | PCA, Primitive NMF | Eliminates negative intensities, reveals precipitate structures | Successful classification of nanometer-sized crystalline precipitates [2] |

| Microbial Communities | OTU abundance data | BioMiCo, Supervised NMF | Incorporates multiple environmental factors, handles sparse data | Accurate detection of CRC-related bacteria [5] |

| LLM Interpretability | MLP activations | Sparse Autoencoders | Better causal steering, aligns with human-interpretable concepts | Outperforms SAEs and supervised baselines on concept steering [16] |

Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of HNMF for materials research requires careful attention to several practical aspects:

Data Preprocessing: Normalize data appropriately for the specific domain. For 4D-STEM, apply flat-field correction and background subtraction. For compositional data, use appropriate transformations to handle sparsity.

Constraint Design: Collaborate with domain experts to identify appropriate constraints. Spatial smoothness, intensity continuity, and known physical boundaries are common starting points.

Model Selection: Determine the appropriate hierarchical depth through cross-validation. Deeper hierarchies offer more detailed decomposition but require more data and computational resources.

Validation Strategy: Employ multiple validation approaches, including synthetic data with known structure, experimental controls, and comparison with complementary characterization techniques.

Computational Optimization: Leverage GPU acceleration for large-scale problems, and consider variational inference methods for Bayesian approaches to reduce computational burden.

Hierarchical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization represents a powerful paradigm for extracting meaningful, interpretable patterns from complex materials science data. By revealing the 'parts-of-parts' structure inherent in multi-scale material systems, HNMF provides researchers with an unparalleled ability to connect microscopic features to macroscopic properties and performance. The protocols and application notes presented here offer a roadmap for implementing these advanced analytical techniques across diverse materials characterization domains, from electron microscopy of metallic glasses to the analysis of complex microbial communities relevant to biomaterials development. As materials research continues to generate increasingly large and complex datasets, hierarchical decomposition approaches will play an ever more critical role in unlocking the scientific insights contained within.

In the field of materials research, the analysis of spectral data from techniques such as mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) and hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is crucial for understanding material composition and properties. Dimensionality reduction methods are indispensable tools for interpreting these complex datasets. While Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and standard Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) have been widely used, Hierarchical Non-negative Matrix Factorization (HNMF) has emerged as a superior approach for extracting meaningful, hierarchical information from spectral data. This application note details the comparative strengths of HNMF, provides experimental protocols for its implementation, and visualizes its advantages through structured data and workflow diagrams.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Strengths

Fundamental Limitations of PCA and Standard NMF

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is an unconstrained factorization method that projects data onto orthogonal principal components. However, it does not account for the non-negative nature of spectral data, which can result in components with negative values that lack physical interpretability in contexts like spectral intensities or chemical concentrations [17].

Standard Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) factorizes a data matrix ( \mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times N}+ ) into two non-negative factor matrices: a spectral basis matrix ( \mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times K}+ ) and a coefficient matrix ( \mathbf{H} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times N}_+ ), such that ( \mathbf{X} \approx \mathbf{WH} ). The non-negativity constraint enhances interpretability, providing a parts-based representation [17] [15]. Despite this advantage, standard NMF is a single-layer decomposition that assumes a flat structure in the data, limiting its ability to capture hierarchical relationships and making it prone to local minima and sensitivity to noise [3] [18].

The Hierarchical NMF (HNMF) Advantage

Hierarchical NMF (HNMF) recursively applies NMF in multiple layers to discover overarching topics encompassing lower-level features. In a typical two-layer HNMF, the input data matrix ( \mathbf{X} ) is first factorized into ( \mathbf{W}1 ) and ( \mathbf{H}1 ). The coefficient matrix ( \mathbf{H}1 ) is then further factorized into ( \mathbf{W}2 ) and ( \mathbf{H}2 ), resulting in the overall factorization ( \mathbf{X} \approx \mathbf{W}1 \mathbf{W}2 \mathbf{H}2 ) [3]. This structure provides several key advantages over both PCA and standard NMF for spectral data analysis, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Qualitative comparison of PCA, Standard NMF, and Hierarchical NMF for spectral data analysis.

| Feature | PCA | Standard NMF | Hierarchical NMF (HNMF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretability | Low (negative components) | High (additive parts) | Very High (multi-level structure) |

| Data Structure Model | Linear, global structure | Linear, flat structure | Linear, hierarchical structure |

| Noise Robustness | Moderate | Low to Moderate | High (with robust variants) |

| Handling of Mixed Pixels | Poor | Good | Excellent |

| Application Flexibility | General purpose | Domain-specific | Domain-specific with hierarchy |

Quantitative Performance Evidence

The theoretical advantages of HNMF are substantiated by empirical evidence from various applications. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 2: Quantitative performance comparison of PCA, NMF, and HNMF in different applications.

| Application Domain | Metric | PCA | Standard NMF | HNMF / Robust DNMF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Unmixing [18] | Reconstruction Error (Synthetic Data) | - | High | Low ((\ell_{2,1})-RDNMF) |

| Mineral Identification [19] | Average Accuracy | - | - | 84.8% (Clustering-Rank1 NMF) |

| Document Classification [3] | Classification Accuracy (20 Newsgroups) | - | Lower than HNMF | Higher than HNMF (Neural NMF) |

| Mass Spectrometry Imaging [17] | Match to UMAP Distributions | Poor | Good | Best (KL-NMF recommended) |

Experimental Protocols for HNMF in Spectral Analysis

Protocol 1: Basic HNMF for Spectral Unmixing

This protocol outlines the steps for applying a two-layer HNMF to decompose a hyperspectral image dataset ( \mathbf{X} ) (with rows representing spectral bands and columns representing pixels) into endmembers and hierarchical abundances [3] [18].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Hyperspectral Image Data Cube: A 3D data matrix (x, y, λ) reshaped into a 2D matrix ( \mathbf{X} ) of size (number of spectral bands × number of pixels).

- HNMF Software Toolbox: Python (

Nimfalibrary,scikit-learn) or R (NMFpackage) with HNMF capabilities. - Spectral Library: A known library of pure component spectra (e.g., USGS, JPL/NASA) for endmember identification.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Reshape the HSI data cube ( \mathbf{I}(x, y, \lambda) ) into a 2D matrix ( \mathbf{X} ) where each column is the spectrum of a single pixel [2].

- Perform necessary pre-processing: noise reduction, dead pixel removal, and normalization.

Rank Selection (k1, k2):

- Determine the ranks for the first (( k1 )) and second (( k2 )) layers. Use methods like analysis of singular values or the stability of NMF solutions across multiple runs [17]. The condition ( k2 < k1 < < \text{min}(M, N) ) must hold.

Layer 1 Factorization:

- Factorize ( \mathbf{X} \approx \mathbf{W}1 \mathbf{H}1 ).

- ( \mathbf{W}1 ) (size: #bands × ( k1 )) contains the first-level spectral basis.

- ( \mathbf{H}1 ) (size: ( k1 ) × #pixels) contains the first-level abundance coefficients.

Layer 2 Factorization:

- Use ( \mathbf{H}1 ) as the new data matrix for the second layer: ( \mathbf{H}1 \approx \mathbf{W}2 \mathbf{H}2 ).

- ( \mathbf{W}2 ) (size: ( k1 ) × ( k_2 )) describes the composition of first-level components from more fundamental second-level components.

- ( \mathbf{H}2 ) (size: ( k2 ) × #pixels) contains the final, second-level abundance maps.

Result Interpretation:

- The overall decomposition is ( \mathbf{X} \approx \mathbf{W}1 \mathbf{W}2 \mathbf{H}_2 ).

- The final endmember spectra can be interpreted as ( \mathbf{W} = \mathbf{W}1 \mathbf{W}2 ) [18].

- The abundance maps for each of the ( k2 ) fundamental components are the rows of ( \mathbf{H}2 ). Reshape each row back to the original 2D spatial dimensions to visualize abundance maps.

Protocol 2: Robust HNMF for Noisy Data

Real-world spectral data is often contaminated by noise. This protocol modifies the basic HNMF using the ( \ell_{2,1} )-norm to improve robustness [18].

Procedure:

- Pretraining Stage (Forward Pass):

- For each layer ( l ), minimize the objective function ( O{RNMF} = \Vert \mathbf{H}{l-1} - \mathbf{V}l \mathbf{H}l \Vert{2,1} ), where ( \mathbf{H}0 = \mathbf{X} ).

- Use multiplicative update rules tailored for the ( \ell{2,1} )-norm to compute ( \mathbf{V}l ) and ( \mathbf{H}_l ). This norm reduces the influence of outlier pixels by assigning them lower weight during updates [18].

- Fine-Tuning Stage (Global Optimization):

- After pretraining all layers, fine-tune the entire network by minimizing the global reconstruction error ( O{deep} = \Vert \mathbf{X} - \mathbf{V}1 \mathbf{V}2 \cdots \mathbf{V}L \mathbf{H}L \Vert{2,1} ).

- This stage propagates information backward, adjusting earlier layers based on the performance of all subsequent layers, which enhances the overall factorization quality [18].

Workflow Visualization and Data Interpretation

HNMF Spectral Unmixing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete two-stage workflow for robust HNMF applied to hyperspectral unmixing, integrating both the pretraining and fine-tuning stages.

Hierarchical Structure of HNMF

This diagram illustrates the conceptual hierarchical decomposition of data in HNMF, showing how the model reveals multi-level structure compared to standard NMF.

Hierarchical NMF represents a significant advancement over both PCA and standard NMF for the analysis of spectral data in materials research. Its capacity to model the intrinsic hierarchical structure of complex mixtures, coupled with superior interpretability and robustness to noise, makes it an indispensable tool for researchers. The provided protocols and visualizations offer a practical foundation for implementing HNMF, enabling deeper insights into material composition and accelerating discovery in fields ranging from pharmaceuticals to geology. As HNMF algorithms continue to evolve, their integration with domain-specific knowledge will further unlock the potential of spectral data analysis.

Implementing HNMF: Methods and Real-World Applications in Research

Within the domain of unsupervised machine learning, Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) serves as a pivotal tool for parts-based data representation. The objective of NMF is to approximate a given nonnegative data matrix ( \mathbf{V} ) as the product of two lower-dimensional, nonnegative factor matrices: ( \mathbf{V} \approx \mathbf{W}^T \mathbf{H} ) [20]. This constraint of nonnegativity is crucial for materials research and many scientific fields, as it yields sparse, parts-based representations that are often more physically interpretable than those from methods permitting negative values (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) [2] [21]. Among the many algorithms developed to compute NMF, the Multiplicative Update (MU) and Hierarchical Alternating Least Squares (HALS) frameworks stand out for their widespread use and distinct characteristics.

The MU algorithm, popularized by Lee and Seung, is renowned for its simplicity of implementation [20] [22]. It operates through element-wise update rules that ensure the nonnegativity of the factors without requiring explicit projection steps. For the commonly used Frobenius norm loss, the updates for ( \mathbf{W} ) and ( \mathbf{H} ) are given by: [ \mathbf{W}{i,j} \leftarrow \mathbf{W}{ij} \frac{(\mathbf{V}\mathbf{H}^T){ij}}{(\mathbf{W}\mathbf{H}\mathbf{H}^T){ij}} \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbf{H}{i,j} \leftarrow \mathbf{H}{ij} \frac{(\mathbf{W}^T\mathbf{V}){ij}}{(\mathbf{W}^T\mathbf{W}\mathbf{H}){ij}} ] These multiplicative rules can be derived from gradient descent by using adaptive learning rates that eliminate subtraction and thus prevent negative elements [22]. A key advantage of MU is its adaptability to various loss functions and regularizations, making it a versatile tool. However, a significant drawback is that its convergence can be slow for some problems, particularly when minimizing the Frobenius norm [20].

In contrast, the HALS algorithm is a block coordinate descent method that optimizes one column of ( \mathbf{W} ) and one row of ( \mathbf{H} ) at a time [21]. Instead of updating the entire matrices simultaneously, HALS solves a series of constrained subproblems. For each column ( \mathbf{w}k ) of ( \mathbf{W} ) and each row ( \mathbf{h}k ) of ( \mathbf{H} ), the updates are: [ \mathbf{w}k \leftarrow \left[ \frac{ (\mathbf{V} - \sum{j \neq k} \mathbf{w}j \mathbf{h}j) \mathbf{h}k^T }{ \|\mathbf{h}k\|2^2 } \right]+ \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbf{h}k \leftarrow \left[ \frac{ \mathbf{w}k^T (\mathbf{V} - \sum{j \neq k} \mathbf{w}j \mathbf{h}j) }{ \|\mathbf{w}k\|2^2 } \right]+ ] where ( [\cdot]_+ ) denotes the projection onto the nonnegative orthant. This hierarchical approach often yields faster convergence and superior numerical performance compared to MU, as it more effectively exploits the structure of the problem [23] [21].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The theoretical differences between MU and HALS translate into distinct practical performance. Empirical assessments, particularly in fields like electroencephalography (EEG) analysis, provide quantitative measures for comparing these algorithms across key metrics including estimation accuracy, stability, and computational time.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of NMF Algorithms on Simulated Data (SNR = 20 dB)

| Algorithm | Average Correlation Coefficient* | Stability (Iq Index) | Relative Computation Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| lraNMF_HALS | ~0.95 | ~0.90 | 1.0x (Fastest) |

| HALS | ~0.85 | ~0.75 | ~1.5x |

| lraNMF_MU | ~0.75 | ~0.65 | ~2.0x |

| NMF_MU | ~0.65 | ~0.50 | ~3.0x |

*Correlation of estimated components with ground truth. Higher is better. Data derived from assessment of NMF algorithms for EEG analysis [23].

The data in Table 1 demonstrates that HALS-based methods, particularly the low-rank approximation variant (lraNMFHALS), comprehensively outperform MU algorithms. The lraNMFHALS algorithm achieves the highest accuracy in recovering true underlying components, exhibits the greatest stability (as measured by the Iq index, where a higher value indicates more consistent results across multiple runs), and requires the least computational time [23]. This superior performance is attributed to HALS's more effective update strategy, which avoids the slow convergence often associated with the multiplicative updates.

Table 2: General Algorithmic Characteristics and Applicability

| Feature | Multiplicative Updates (MU) | Hierarchical ALS (HALS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Simultaneous updates via multiplication | Cyclic, column/row-wise updates |

| Convergence Speed | Slower, especially for Frobenius loss [20] | Faster [23] [21] |

| Stability of Results | Lower, higher variability between runs [23] | Higher, more reproducible results [23] |

| Implementation Complexity | Simple, easy to code [20] | More complex, requires careful optimization |

| Best-Suited For | Quick prototyping; KL divergence loss [20] | Large-scale data; high accuracy & stability required [23] [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Materials Research

The application of NMF in materials science, particularly for techniques like 4D-Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (4D-STEM), requires specific protocols to ensure the extracted components are physically interpretable [2].

Protocol 1: Primitive NMF for 4D-STEM Data Factorizatio

Objective: To decompose a 4D-STEM dataset ( I_{4D}(x, y, u, v) ) into a set of nonnegative basis diffractions and their corresponding spatial maps to identify distinct material phases or orientations.

Materials and Data Preparation:

- Input Data: A 4D data array ( I_{4D}(x, y, u, v) ) where ( (x, y) ) are real-space coordinates and ( (u, v) ) are reciprocal-space coordinates.

- Data Reshaping: Reconstruct the 4D array into a 2D matrix ( \mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{n{uv} \times n{xy}} ), where ( n{uv} = nu \times nv ) is the total number of pixels in a single diffraction pattern, and ( n{xy} = nx \times ny ) is the total number of probe positions [2].

Procedure:

- Initialization: Randomly initialize or use smart initialization for the matrices ( \mathbf{W} ) (diffraction basis) and ( \mathbf{H} ) (coefficient maps). Set the target rank ( k ), which corresponds to the expected number of distinct physical components.

- Algorithm Selection and Iteration: Choose either MU or HALS and iterate until convergence (e.g., until the relative change in the Frobenius norm loss falls below a threshold of ( 10^{-4} ) or for a maximum of 100 iterations).

- Post-processing and Interpretation: Reshape each column of ( \mathbf{W} ) back into a 2D diffraction pattern ( \mathbf{w}k(u, v) ). Reshape each row of ( \mathbf{H} ) back into a 2D spatial map ( \mathbf{h}k(x, y) ). Analyze these components to correlate specific diffractions with material features in real space.

Protocol 2: Constrained NMF with Domain Knowledge

Objective: To perform NMF with constraints that incorporate domain-specific knowledge from electron microscopy, such as spatial smoothness in maps and specific intensity profiles in diffractions, to avoid physically implausible artifacts.

Rationale: Primitive NMF can produce components with "downward-convex peaks" or high-frequency noise that are not physically meaningful in the context of electron diffraction [2]. This protocol integrates constraints to mitigate these issues.

Procedure:

- Preprocessing and Primitive Factorization: Follow Protocol 1 to obtain an initial factorization using an unconstrained algorithm.

- Constraint Implementation via Alternating Least Squares (ALS): Transition to an ALS-based solver (the core of HALS) which allows flexible projection of constraints [2].

- Spatial Smoothness Constraint: For each spatial map in ( \mathbf{H} ), apply a Gaussian or median filter during each update to suppress high-frequency noise and enforce spatial coherence, reflecting the finite probe size in STEM.

- Intensity Profile Constraint: For the diffraction basis in ( \mathbf{W} ), enforce non-sparsity or apply a smoothing kernel to prevent the algorithm from representing a continuous background as a set of sparse, sharp peaks.

- Convergence Check: Monitor the cost function to ensure the constrained optimization is converging. The final output will be a set of smoothed, physically plausible components.

Figure 1: Workflow for 4D-STEM data factorization using primitive and constrained NMF.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successfully implementing NMF in a materials research context involves both data and software resources. The following table lists key "research reagents" for computational experiments.

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for NMF in Materials Science

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Analysis | Example Platform/Library |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4D-STEM Data Acquisitio | Raw Data | Provides the initial nonnegative matrix ( \mathbf{V} ) for factorization [2] | Electron Microscope |

| Data Reshaping Script | Preprocessing | Transforms 4D data array ( I_{4D} ) into 2D matrix ( \mathbf{X} ) for NMF [2] | Python (NumPy), MATLAB |

| NMF Algorithm Solver | Core Algorithm | Computes the factorization ( \mathbf{X} \approx \mathbf{W} \mathbf{H} ) using MU, HALS, or other variants [2] [23] | scikit-learn ('mu', 'cd'), MATLAB ('nnmf'), Custom HALS [23] |

| Smoothing & Constraint Functions | Post-processing/Constraint | Enforces domain knowledge (e.g., spatial smoothness) on ( \mathbf{W} ) or ( \mathbf{H} ) [2] | Custom Image Processing Filters |

| Stability Validation Script | Validation | Assesses the reliability of extracted components via multiple runs and clustering [23] | Python, MATLAB |

The choice between Multiplicative Update and Hierarchical Alternating Least Squares algorithms for Nonnegative Matrix Factorization has a direct and significant impact on the quality and efficiency of data analysis in materials research. While MU offers simplicity and ease of implementation, comprehensive benchmarks show that HALS and its variants (like lraNMF_HALS) provide superior performance in terms of convergence speed, stability, and estimation accuracy [23]. For researchers working with complex materials characterization data such as 4D-STEM, starting with a primitive NMF analysis (using either MU or HALS) and then progressing to a constrained NMF framework that incorporates domain-specific knowledge is a powerful approach to extract physically meaningful and interpretable components from high-dimensional datasets [2].

Four-Dimensional Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (4D-STEM) has emerged as a revolutionary technique in materials characterization, enabling the acquisition of a two-dimensional diffraction pattern at every probe position during a two-dimensional raster scan, thus generating a complex four-dimensional dataset [24]. This method captures all available information from the probe's interaction with the sample, going beyond conventional STEM imaging which integrates large portions of the diffraction pattern to generate a single intensity value per probe position, thereby discarding vast amounts of structural and electrostatic information [25]. The 4D-STEM technique allows researchers to visualize the distribution of crystalline phases, crystal orientations, and the directions of magnetic and electric fields by leveraging differences in diffraction data at specific spatial positions [24].

However, this advanced capability comes with significant computational challenges. A typical 4D-STEM dataset can contain tens of thousands of diffraction patterns, often reaching gigabyte-scale sizes (e.g., 128⁴ pixels with 4 bytes per pixel) [26]. For instance, datasets comprising 3,364 diffractions with 128×128 pixels in diffraction space are common, creating substantial computational burdens for analysis [26]. This deluge of information necessitates sophisticated statistical and machine learning approaches to extract meaningful crystallographic insights with nanometer spatial resolution, pushing the boundaries of conventional electron microscopy data analysis methods [27] [26].

Hierarchical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (HNMF) Framework

Theoretical Foundation of NMF for 4D-STEM

Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) provides a powerful framework for decomposing complex 4D-STEM datasets into interpretable components. The core mathematical principle involves representing the experimental data matrix X as a linear combination of essential diffraction patterns S and their spatial distributions C through the equation X = SC [26]. In this formulation, X ∈ ℝ₊^{nuv × nxy} represents the transformed 4D-STEM data where each experimental diffraction pattern s(u,v) at position (x,y) is transformed into a one-dimensional column vector, with nxy = nx × ny representing the total number of probe positions and nuv = nu × nv representing the dimensionality of each diffraction pattern [26].

The matrices S ∈ ℝ₊^{nuv × nk} and C ∈ ℝ₊^{nk × nxy} contain the factorized diffraction patterns and their spatial distributions (maps), respectively, with nk representing the number of components and nk << n_xy ensuring dimensionality reduction [26]. The non-negativity constraints on all matrices are physically meaningful for electron microscopy data since diffraction intensities and spatial concentrations cannot be negative, leading to more interpretable components compared to other factorization methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) where components often include unphysical negative values [27].

Hierarchical Clustering with Crystallographic Similarity

The hierarchical aspect of HNMF addresses a critical challenge in conventional NMF: determining the optimal number of components. Hierarchical clustering generates a nested set of clusters represented as a dendrogram, allowing researchers to explore the data structure at different levels of granularity without pre-specifying the final number of clusters [26]. Unlike conventional clustering that uses Euclidean distances or cosine similarity, the optimized HNMF approach employs a crystallographic similarity measure based on cross-correlation of diffraction patterns transformed into polar coordinates (r-φ space) [26].

This specialized similarity metric accounts for the physics of electron diffraction governed by Bragg's law (2dsinθ = λ), where the scattering angle θ is directly proportional to the inverse lattice constant of the material [26]. By allowing shifts only along the φ axis during cross-correlation computation, this approach automatically corrects for in-plane rotations of crystal domains, a common occurrence in real specimens that would otherwise complicate analysis using conventional distance measures [26]. The cross-correlation values range from -1 to 1, with peaks indicating perfect similarity and off-centering reflecting misalignment that can be computationally corrected.

Domain-Constrained NMF Formulation

Recent advances have incorporated domain-specific constraints inherent to electron microscopy to further enhance the interpretability and physical relevance of the factorization results. These constraints include spatial resolution limits and continuous intensity features without downward-convex peaks, which reflect physical knowledge about how materials scatter electrons [1]. This constrained NMF approach has demonstrated superior performance in decomposing both simulated and actual experimental 4D-STEM data into interpretable diffractions and maps that cannot be achieved using PCA and primitive NMF methods [1].

The domain knowledge integration helps mitigate common artifacts found in conventional machine learning techniques that rely solely on mathematical constraints without incorporating physical understanding of electron microscopy principles [1]. By embedding these domain-specific constraints directly into the factorization algorithm, researchers can obtain results that are not only mathematically sound but also physically meaningful, bridging the gap between pure data analysis and materials science interpretation.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Data Acquisition Parameters for 4D-STEM

The acquisition of high-quality 4D-STEM data requires careful optimization of experimental parameters to ensure sufficient signal-to-noise ratio while minimizing electron dose damage to sensitive specimens. The following table summarizes key acquisition parameters used in published studies applying HNMF to 4D-STEM data:

Table 1: Typical 4D-STEM Data Acquisition Parameters

| Parameter | Specification | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Accelerating Voltage | 200 kV | High-resolution imaging of titanium oxide nanosheets [27] |

| Spatial Scan Dimensions | 58×58 pixels (3,364 diffractions) | Metallic glass analysis [26] |

| Diffraction Pattern Dimensions | 128×128 pixels | Standard for balance of resolution & file size [26] |

| Detector Type | Fast, high-sensitivity camera (CCD/CMOS) | Ptychography and orientation mapping [24] |

| Convergence Angle | Small (non-overlapping disks) to large (overlapping disks) | Application-dependent [24] |

HNMF Algorithm Implementation

The implementation of HNMF for 4D-STEM data follows a multi-step procedure that combines alternating least-squares NMF with hierarchical clustering:

Data Preprocessing: The 4D data I₄D(x,y,u,v) is transformed into a 2D matrix X where each column represents an unraveled diffraction pattern [26].

Dimensionality Reduction via NMF:

- The number of components n_k is assumed (typically starting with an overestimate) [26].

- Matrix C is initialized with non-negative random numbers [26].

- Alternate updating of S and C matrices:

- Row vectors of C are sorted by their L2 norm, with corresponding reordering of S columns [26].

- Mean Square Error (MSE) is calculated as MSE = (nxy × nuv)⁻¹∑(X - SC)² [26].

- Multiple computations with different initial values are performed to avoid local minima [26].

Hierarchical Clustering:

HNMF Workflow for 4D-STEM Data Analysis

Research Reagents and Essential Materials

The successful application of HNMF to 4D-STEM data analysis requires both physical specimens and computational tools, as detailed in the following table:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen Systems | Titanium oxide nanosheets, Zr-Cu-Al metallic glass, Mn-Zn ferrite | Model systems for method validation [27] [26] |

| Software Platforms | DigitalMicrograph (Gatan) with custom scripts, Python/scikit-learn | Implementation of NMF and clustering algorithms [26] |

| Computational Methods | Alternating Least Squares (ALS) NMF, Cross-correlation similarity | Core factorization and similarity measurement [26] |

| Detector Systems | Fast pixelated detectors (CCD/CMOS), Timepix3 event-based detectors | Data acquisition with high temporal resolution [28] |

| Preprocessing Tools | Polar coordinate transformation, Intensity normalization | Data preparation for crystallographic analysis [26] |

Applications and Case Studies

Analysis of Titanium Oxide Nanosheets

In a foundational study, NMF was applied to 4D-STEM data acquired from titanium oxide nanosheets with overlapping domains [27]. The experimental data contained diffraction patterns from both pristine Ti₀.₈₇O₂ and topotactically reduced domains, which were successfully factorized into interpretable components using the HNMF approach [27]. The analysis revealed that NMF provided lower Mean Square Errors (MSEs) compared to PCA for up to 9 components, demonstrating its superior capability for identifying a small number of essential components from complex 4D-STEM data [27]. This case study established HNMF as a valid approach for mining useful crystallographic information from big data obtained using 4D-STEM, particularly for systems with overlapping structural domains.

Metallic Glass Nanostructural Analysis

The combination of 4D-STEM and optimized unsupervised machine learning enabled comprehensive bimodal analysis of a high-pressure-annealed metallic glass, Zr-Cu-Al [26]. This investigation revealed an amorphous matrix and crystalline precipitates with an average diameter of approximately 7 nm, which were challenging to detect using conventional STEM techniques [26]. The HNMF approach successfully decomposed the complex dataset into physically meaningful diffraction patterns and spatial maps, demonstrating the power of this method for analyzing nanostructures that deviate from perfect crystallinity and would be difficult to characterize using traditional methods.

Battery Material Interfaces

Recent advances have applied randomized NMF (RNMF) with QB decomposition preprocessing to map complex battery interfaces, specifically between amorphous Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂ (LGPS) and crystalline LiNi₀.₆Co₀.₂Mn₀.₂O₂ (NMC) [29]. This approach addressed the significant computational challenges of analyzing large 4D-STEM datasets, achieving scaling independent of the largest data dimension (∼O(nk)) instead of the conventional O(nmk) scaling of standard NMF [29]. The successful application to this technologically important material system highlights the potential of HNMF for investigating mixed crystalline-amorphous interfaces in functional materials.

HNMF Application Domains in Materials Research

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Computational Challenges and Solutions