Gaussian Process Models for Material Property Prediction: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Gaussian Process (GP) models for predicting material properties, with a special focus on applications relevant to drug development.

Gaussian Process Models for Material Property Prediction: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Gaussian Process (GP) models for predicting material properties, with a special focus on applications relevant to drug development. It covers foundational concepts, explores advanced methodologies like Multi-Task and Deep GPs for handling correlated properties, and addresses practical challenges such as uncertainty quantification for heteroscedastic data and model optimization. The guide also offers a comparative analysis of GP models against other machine learning surrogates, validating their performance in real-world materials discovery scenarios. Designed for researchers and scientists, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to implement robust, data-efficient predictive models that accelerate innovation in biomaterials and therapeutic agent design.

Gaussian Process Fundamentals: Mastering Uncertainty Quantification in Materials Science

Gaussian Processes (GPs) represent a powerful, non-parametric Bayesian approach for regression and classification, offering a principled framework for uncertainty quantification essential for computational materials science. In material property prediction, where experimental data is often sparse and costly to obtain, GPs provide not only predictions but also reliable confidence intervals, guiding researchers in decision-making and experimental design [1]. Their flexibility to incorporate prior knowledge and model complex, non-linear relationships makes them particularly suited for navigating vast design spaces, such as those found in high-entropy alloys (HEAs) and polymer design [2] [3]. This article details the core methodologies and applications of GPs, from foundational Bayesian principles to advanced hierarchical models, providing structured protocols for researchers aiming to deploy these techniques in material discovery and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: From Bayesian Inference to Non-Parametric Models

Bayesian Inference and Non-Parametric Basics

Bayesian inference forms the theoretical backbone of Gaussian Processes. In a Bayesian framework, prior beliefs about an unknown function are updated with observed data to form a posterior distribution. Traditional parametric Bayesian models are limited by their fixed finite-dimensional parameter space. Bayesian nonparametrics overcomes this by defining priors over infinite-dimensional function spaces, providing the flexibility to adapt model complexity to the data [4]. A Gaussian Process extends this concept to function inference, defining a prior directly over functions, where any finite collection of function values has a multivariate Gaussian distribution [4].

A GP is completely specified by its mean function ( m(\mathbf{x}) ) and covariance kernel ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') ), expressed as: ( f(\mathbf{x}) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(\mathbf{x}), k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}')) ) The mean function is often set to zero, while the kernel function encodes prior assumptions about the function's smoothness, periodicity, and trends. This non-parametric approach avoids the need to pre-specify a functional form (e.g., linear, quadratic), allowing the model to discover complex patterns from the data itself.

Key Kernel Functions and Selection

The choice of kernel function is critical as it dictates the structure of the functions a GP can fit. Below is a comparison of common kernels used in materials informatics:

Table 1: Common Kernel Functions in Gaussian Process Regression

| Kernel Name | Mathematical Form | Hyperparameters | Function Properties | Typical Use Cases in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigma_f^2 \exp\left(-\frac{|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|^2}{2\ell^2}\right) ) | ( \ell ) (length-scale), ( \sigma_f^2 ) (variance) | Infinitely differentiable, very smooth | Modeling smooth, continuous properties like formation energy or bulk modulus [2]. |

| Matérn 5/2 | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigma_f^2 \left(1 + \frac{\sqrt{5}|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|}{\ell} + \frac{5|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|^2}{3\ell^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\sqrt{5}|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|}{\ell}\right) ) | ( \ell ) (length-scale), ( \sigma_f^2 ) (variance) | Twice differentiable, less smooth than RBF | Modeling properties with more roughness or noise, such as yield strength or hardness [5]. |

| Linear | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigma_f^2 + \mathbf{x}^T \cdot \mathbf{x}' ) | ( \sigma_f^2 ) (variance) | Results in linear functions | Useful as a component in kernel combinations to capture linear trends. |

Advanced Gaussian Process Models for Materials Research

Multi-Task and Deep Gaussian Processes

Real-world materials design involves predicting multiple correlated properties from heterogeneous data sources. Standard, single-task GPs are insufficient for this. Multi-Task Gaussian Processes (MTGPs) model correlations between related tasks (e.g., yield strength and hardness) using connected kernel structures, allowing information transfer between tasks and improving data efficiency [2]. For instance, an MTGP can leverage the correlation between strength and ductility to improve predictions for both properties, even when data for one is sparser [2].

Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs) offer a hierarchical, multi-layer extension. A DGP is a composition of GP layers, where the output of one GP layer serves as the input to the next. This architecture enables the model to capture highly complex, non-stationary, and hierarchical relationships in materials data [1] [5]. DGPs have demonstrated superior performance in predicting properties of high-entropy alloys from hybrid computational-experimental datasets, effectively handling heteroscedastic noise and missing data [1].

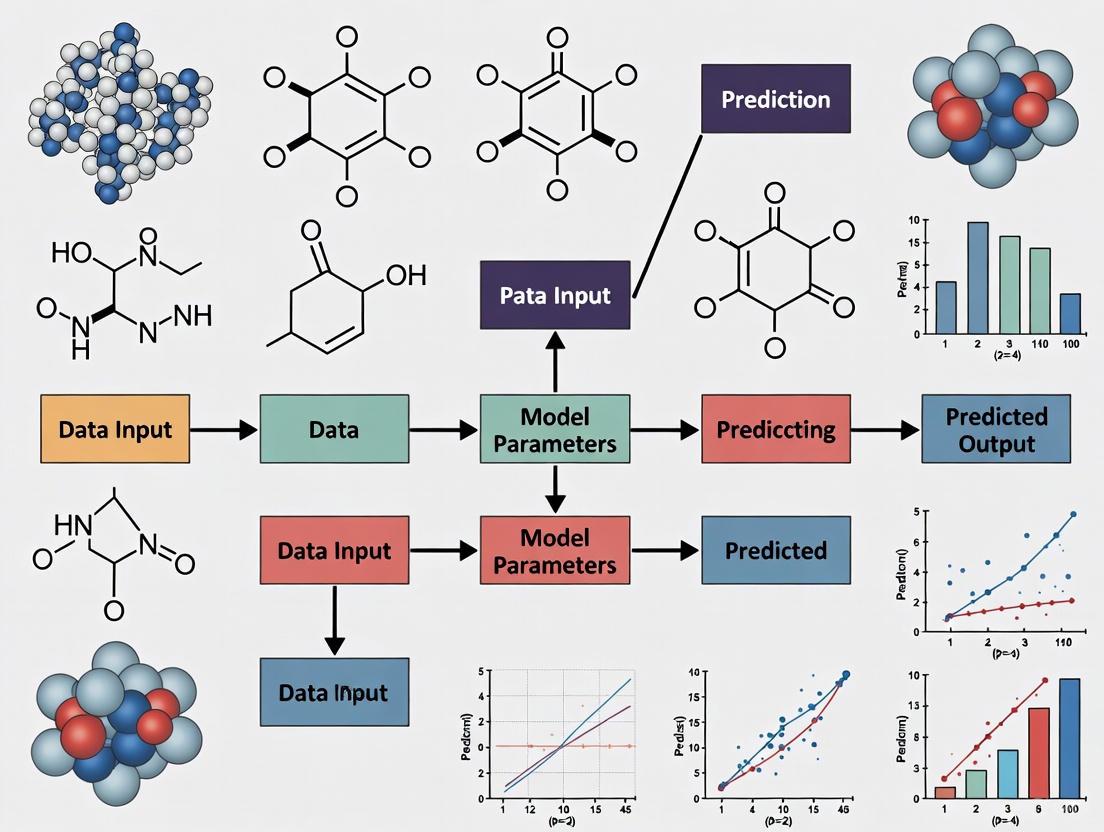

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual architecture and data flow of a Deep Gaussian Process model as applied to material property prediction.

Hybrid and Enhanced GP Models

Integrating GPs with other modeling paradigms leverages their respective strengths. The Group Contribution-GP (GCGP) method is a prominent example in molecular design. It uses simple, fast group contribution (GC) model predictions and molecular weight as input features to a GP. The GP then learns and corrects the systematic bias of the GC model, resulting in highly accurate predictions with reliable uncertainty estimates for thermophysical properties like critical temperature and enthalpy of vaporization [3].

Another powerful synergy combines GPs with Bayesian Optimization (BO). In this framework, the GP serves as a surrogate model for an expensive-to-evaluate objective function (e.g., a experiment or a high-fidelity simulation). The GP's predictive mean and uncertainty guide an acquisition function to select the most promising candidate for the next evaluation, dramatically accelerating the discovery of optimal materials, such as HEAs with targeted thermal and mechanical properties [2] [5].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Predicting HEA Properties using Deep Gaussian Processes

This protocol outlines the application of a Deep Gaussian Process model for multi-property prediction in the Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V high-entropy alloy system, based on the BIRDSHOT dataset [1].

1. Problem Definition and Data Preparation

- Objective: Simultaneously predict correlated mechanical properties: yield strength (YS), hardness, modulus, ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and elongation.

- Data Context: Utilize a hybrid dataset containing sparse experimental measurements and more abundant computational property estimates.

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize all alloy compositions to sum to 1 (or 100%).

- Standardize all target property values (mean-center and scale to unit variance).

- Handle missing data: The DGP model can natively accommodate heterotopic data, where not all properties are measured for every sample.

2. Model Selection and Architecture

- Model: Employ a 2-layer Deep Gaussian Process.

- Kernels: Use Matérn 5/2 kernels for each layer for a balance of flexibility and smoothness.

- Prior Guidance: Infuse the model with a machine-learned prior, such as the features from an encoder-decoder neural network, to improve initialization and performance [1].

3. Model Training and Inference

- Inference Method: Use variational inference to approximate the posterior distribution, as exact inference is intractable in DGPs.

- Optimization: Train the model by maximizing the evidence lower bound (ELBO) using a stochastic gradient-based optimizer (e.g., Adam).

- Uncertainty Quantification: Extract predictive mean and variance from the posterior predictive distribution.

4. Model Validation and Analysis

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation on the experimental data.

- Benchmarking: Compare performance against benchmarks like conventional GP, XGBoost, and encoder-decoder neural networks using metrics like RMSE and negative log-likelihood.

- Analysis: Examine the learned correlation structure between output properties to gain scientific insights.

Protocol 2: Bayesian Optimization for HEA Discovery

This protocol describes using a Multi-Task GP within a Bayesian Optimization loop to discover HEAs in the Fe-Cr-Ni-Co-Cu system with optimal combinations of thermal and mechanical properties [2].

1. Problem Setup

- Design Space: Define the 5-dimensional compositional space for the HEA system.

- Objectives: Define the target properties. Example 1: Minimize the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) and maximize the bulk modulus (BM). Example 2: Maximize both CTE and BM [2].

- Evaluation Source: Use high-throughput atomistic simulations to query material properties.

2. Surrogate Modeling with MTGP

- Model: Construct a Multi-Task Gaussian Process surrogate.

- Kernel: Use a coregionalization kernel to capture correlations between CTE and BM.

- Data Incorporation: Update the MTGP model with new (composition, {CTE, BM}) data after each BO iteration.

3. Acquisition Function and Candidate Selection

- Acquisition: Use the Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) to handle the multi-objective nature of the problem.

- Balancing Act: EHVI naturally balances exploration (sampling uncertain regions) and exploitation (sampling near predicted optima).

- Selection: Choose the next composition to evaluate by maximizing the EHVI.

4. Iterative Optimization Loop

- Iteration: Repeat the cycle of surrogate model update, acquisition function maximization, and expensive function evaluation until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., budget exhaustion or performance convergence).

- Output: The final output is a Pareto front of non-dominated alloys representing the best trade-offs between the target properties.

The workflow for this Bayesian Optimization process is summarized in the following diagram.

Performance Comparison of Surrogate Models

The selection of a surrogate model has a significant impact on prediction accuracy and optimization efficiency. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of different models applied to HEA data, as reported in recent literature.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Surrogate Models for HEA Property Prediction [1] [2]

| Model | Key Characteristics | Uncertainty Quantification | Handling of Multi-Output Correlations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional GP (cGP) | Single-layer, probabilistic. | Native, well-calibrated. | No (requires separate models). | Suboptimal in multi-objective BO; ignores property correlations [2]. |

| Multi-Task GP (MTGP) | Single-layer, multi-output. | Native, well-calibrated. | Yes, explicitly models correlations. | Outperforms cGP in BO by leveraging correlations; more data-efficient [2]. |

| Deep GP (DGP) | Hierarchical, multi-layer, highly flexible. | Native, propagated through layers. | Yes, can learn complex shared representations. | Superior accuracy and uncertainty handling on hybrid, sparse HEA datasets [1]. |

| XGBoost | Tree-based, gradient boosting. | Not native (requires extensions). | No (requires separate models). | Often easier to scale but outperformed by DGP/MTGP on correlated property prediction [1]. |

| Encoder-Decoder NN | Deterministic, deep learning. | Not native. | Yes, through bottleneck architecture. | High accuracy but lacks predictive uncertainty, limiting use in decision-making [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the key computational tools and data resources essential for implementing Gaussian Process models in materials research.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for GP-Based Materials Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| BIRDSHOT Dataset | Material Dataset | A high-fidelity collection of mechanical and compositional data for over 100 distinct HEAs in the Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V system, used for training and benchmarking surrogate models [1]. |

| High-Throughput Atomistic Simulations | Data Generation Tool | Provides a source of abundant, albeit sometimes lower-fidelity, data on material properties (e.g., from DFT calculations) which can be used as auxiliary tasks in MTGP/DGP models [2] [6]. |

| Group Contribution (GC) Models | Feature Generator/Base Predictor | Provides simple, interpretable initial predictions for molecular properties (e.g., via Joback & Reid method). These predictions serve as inputs to a GC-GP model for bias correction and uncertainty quantification [3]. |

| Variational Inference Algorithms | Computational Method | A key technique for approximate inference in complex GP models like DGPs, where exact inference is computationally intractable [1]. |

| Multi-Objective Acquisition Function (q-EHVI) | Optimization Algorithm | Guides the selection of candidate materials in multi-objective Bayesian optimization by quantifying the potential improvement to the Pareto front [5]. |

Gaussian process (GP) models have emerged as a powerful tool in the field of materials informatics, providing a robust framework for predicting material properties and accelerating the discovery of new compounds. As supervised learning methods, GPs solve regression and probabilistic classification problems by defining a distribution over functions, offering a non-parametric Bayesian approach for inference [7]. Unlike traditional parametric models that infer a distribution over parameters, GPs directly infer a distribution over the function of interest, making them particularly valuable for modeling complex material behavior where the underlying functional form may be unknown [7].

The versatility of GP models has been demonstrated across diverse materials science applications, from predicting properties of high-entropy alloys (HEAs) to optimizing material structures through high-throughput computing [6] [1]. Their ability to quantify prediction uncertainty is especially crucial in materials design, where decisions based on model predictions can significantly impact experimental direction and resource allocation. A GP is completely specified by its mean function and covariance function (kernel), which together determine the shape and characteristics of the functions in its prior distribution [8]. Understanding these core components—kernels, mean functions, and hyperparameters—is essential for researchers aiming to leverage GP models effectively in material property prediction.

Core Components of Gaussian Processes

Kernel Functions: The Engine of Generalization

The kernel function, also known as the covariance function, serves as the fundamental component that defines the covariance between pairs of random variables in a Gaussian process. It encodes our assumptions about the function being learned by specifying how similar two data points are, with the fundamental assumption that similar points should have similar target values [9]. The choice of kernel determines almost all the generalization properties of a GP model, making its selection one of the most critical decisions in model specification [10].

In mathematical terms, a Gaussian process is defined as: $$y \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x),k(x,x'))$$ where $m(x)$ is the mean function and $k(x,x')$ is the kernel function defining the covariance between values at inputs $x$ and $x'$ [8]. The kernel function must be positive definite to ensure the resulting covariance matrix is valid and invertible [8].

kWN(x, x') = σ² In White Noise Kernel

- Models independent and identically distributed noise

- Covariance matrix has non-zero values only on the diagonal

- All covariances between samples are zero as noise is uncorrelated [8]

kSE(x, x') = σ² exp(-||xa - xb||² / 2ℓ²) Exponentiated Quadratic Kernel (Squared Exponential, RBF, Gaussian)

- Results in smooth, infinitely differentiable functions

- Lengthscale ℓ determines the length of 'wiggles' in the function

- Output variance σ² determines average distance of function from its mean [10]

kRQ(x, x') = σ² (1 + ||x - x'||² / 2αℓ²)−α Rational Quadratic Kernel

- Equivalent to adding many SE kernels with different lengthscales

- Models functions varying smoothly across many lengthscales

- Parameter α determines weighting of large-scale vs small-scale variations [10]

kPer(x, x') = σ² exp(-2sin²(π|x - x'|/p) / ℓ²) Periodic Kernel

- Models functions that repeat themselves exactly

- Period p determines distance between repetitions

- Lengthscale ℓ determines smoothness within each period [10]

kLin(x, x') = σb² + σv²(x - c)(x' - c) Linear Kernel

- Non-stationary kernel (depends on absolute location of inputs)

- Results in Bayesian linear regression when used alone

- Offset c determines point where all lines in posterior intersect [10]

Kernel Selection and Combination Strategies

Selecting an appropriate kernel is crucial for building an effective GP model for material property prediction. The Squared Exponential (SE) kernel has become a popular default choice due to its universality and smooth, infinitely differentiable functions [10]. However, this very smoothness can be problematic for modeling functions with discontinuities or sharp changes, which may occur in certain material properties. In such cases, the Exponential or Matern kernels may be more appropriate, producing "spiky," less smooth functions that can capture such behavior [11].

For materials data that exhibits periodic patterns, such as crystal structures or nanoscale repeating units, the Periodic kernel provides an excellent foundation [10]. When combining different types of features or modeling complex relationships in materials data, kernel composition becomes essential. Multiplying kernels acts as an AND operation, creating a new kernel with high value only when both base kernels have high values, while adding kernels acts as an OR operation, producing high values if either kernel has high values [10].

Table 1: Common Kernel Combinations and Their Applications in Materials Science

| Combination | Mathematical Form | Resulting Function Properties | Materials Science Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear × Periodic | $k{\textrm{Lin}} \times k{\textrm{Per}}$ | Periodic with increasing amplitude away from origin | Modeling cyclic processes with trending behavior |

| Linear × Linear | $k{\textrm{Lin}} \times k{\textrm{Lin}}$ | Quadratic functions | Bayesian polynomial regression of any degree |

| SE × Periodic | $k{\textrm{SE}} \times k{\textrm{Per}}$ | Locally periodic functions that change shape over time | Modeling seasonal patterns with evolving characteristics |

| Multidimensional Product | $kx(x, x') \times ky(y, y')$ | Function varies across both dimensions | Modeling multivariate material properties |

| Additive Decomposition | $kx(x, x') + ky(y, y')$ | Function is sum of one-dimensional functions | Separable effects in material response |

In materials informatics, a common approach is to start with a simple kernel such as the SE and progressively build more complex kernels by adding or multiplying components based on domain knowledge and data characteristics [10]. For high-dimensional material descriptors, the Automatic Relevance Determination (ARD) variant of kernels can be particularly valuable, as it assigns different lengthscale parameters to each input dimension, effectively performing feature selection by identifying which descriptors most significantly influence material properties [9].

Mean Functions: The Often Overlooked Component

While kernels typically receive more attention in GP modeling, the mean function plays an important role in certain applications. The mean function represents the expected value of the GP prior before observing any data. In practice, many GP implementations assume a zero mean function, as the model can often capture complex patterns through the kernel alone [11]. However, this approach has limitations, particularly when making predictions far from the training data.

As noted in GP literature, "the zero mean GP, which always converges to 0 away from the training set, is safer than a model which will happily shoot out insanely large predictions as soon as you get away from the training data" [11]. This behavior makes the zero mean function a conservative choice that avoids extreme extrapolations. Nevertheless, there are compelling reasons to consider non-zero mean functions in materials science applications.

When physical considerations suggest asymptotic behavior should follow a specific form, incorporating this knowledge through the mean function can significantly improve model performance. For example, if domain knowledge indicates that a material property should approach linear behavior at compositional extremes, using a linear mean function incorporates this physical insight directly into the model [11]. Additionally, mean functions make GP models more interpretable, which is valuable when trying to derive scientific insights from the model.

Hyperparameters: Optimization and Interpretation

Hyperparameters control the behavior and flexibility of kernels and mean functions. Each kernel has specific hyperparameters that determine its characteristics, such as lengthscale ($\ell$), variance ($\sigma^2$), and period ($p$) [7]. Proper optimization of these hyperparameters is crucial for building effective GP models that balance underfitting and overfitting.

Table 2: Key Hyperparameters and Their Effects on Model Behavior

| Hyperparameter | Controlled By | Effect on Model | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lengthscale ($\ell$) | SE, Periodic, RQ kernels | Controls smoothness; decreasing creates less smooth, potentially overfitted functions | Balance between capturing variation and avoiding noise fitting |

| Variance ($\sigma^2$) | All kernels | Determines average distance of function from mean | Affects scale of predictions and confidence intervals |

| Noise ($\alpha$ or $\sigma_n^2$) | White kernel or alpha parameter | Represents observation noise in targets | Moderate noise helps with numerical stability via regularization |

| Period ($p$) | Periodic kernel | Sets distance between repetitions in periodic functions | Should align with known periodicities in material behavior |

| Alpha ($\alpha$) | RQ kernel | Balances small-scale vs large-scale variations | Higher values make RQ resemble SE more closely |

Hyperparameters are typically optimized by maximizing the log-marginal-likelihood (LML), which automatically balances data fit and model complexity [9]. Since the LML landscape may contain multiple local optima, it is common practice to restart the optimization from multiple initial points [9]. The number of restarts (n_restarts_optimizer) should be specified based on the complexity of the problem and computational resources available.

For critical applications in materials design, Bayesian hyperparameter optimization combined with K-fold cross-validation has been shown to enhance accuracy significantly. In land cover classification tasks, this approach improved model accuracy by 2.14% compared to standard Bayesian optimization without cross-validation [12]. This demonstrates the value of robust hyperparameter tuning strategies in scientific applications where prediction accuracy directly impacts research outcomes.

Experimental Protocols for Gaussian Process Modeling

Standard GPR Implementation Workflow

Implementing Gaussian process regression follows a systematic workflow that integrates the core components discussed previously. The following protocol outlines the key steps for building and validating a GP model for material property prediction.

Protocol 1: Gaussian Process Regression for Material Property Prediction

Materials and Software Requirements

- Python environment with GP libraries (scikit-learn, GPy, GPflow, or GPyTorch)

- Material dataset with features and target properties

- Computational resources appropriate for dataset size

Procedure

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

- Collect and preprocess material descriptors (compositional, structural, electronic features)

- Handle missing values through imputation or removal

- Normalize or standardize features to comparable scales

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets (typical ratio: 70/15/15)

Kernel Selection and Initialization

- Start with simple kernels (e.g., SE) and progressively increase complexity

- Consider physical constraints (periodicity, smoothness, discontinuities)

- Initialize hyperparameters based on domain knowledge or data statistics

- For multiple input types, consider additive or multiplicative kernel combinations

Mean Function Specification

- For local interpolation tasks, use zero mean function

- When physical models suggest asymptotic behavior, incorporate appropriate mean functions

- For extrapolation tasks, consider constant or linear mean functions

Hyperparameter Optimization

- Maximize log-marginal-likelihood using preferred optimizer (L-BFGS-B is common)

- Use multiple restarts (typically 5-10) to avoid local optima

- Set appropriate bounds for hyperparameters based on data characteristics

- For production models, consider Bayesian optimization with cross-validation [12]

Model Fitting and Validation

- Fit GP model using optimized hyperparameters

- Validate on holdout set using appropriate metrics (RMSE, MAE, negative log-likelihood)

- Check uncertainty calibration - 95% confidence intervals should contain ~95% of actual values

- Perform residual analysis to identify systematic patterns

Prediction and Uncertainty Quantification

- Generate posterior predictive distribution for new material compositions

- Extract both mean predictions and uncertainty estimates

- Use uncertainty estimates to guide experimental design and active learning

Timing Considerations

- Data preparation: 1-2 days

- Kernel design and initial modeling: 1-3 days

- Hyperparameter optimization: 2-5 days (depending on dataset size and complexity)

- Validation and iteration: 2-4 days

Advanced Protocol: Nested Cross-Validation for Robust Hyperparameter Tuning

For high-stakes applications in materials design, particularly when dataset sizes are limited, nested cross-validation provides a more robust approach for hyperparameter optimization and model evaluation.

Protocol 2: Nested Cross-Validation for Gaussian Processes

Purpose To obtain unbiased performance estimates while optimizing hyperparameters, particularly important for small material datasets where standard train-test splits may introduce significant variance.

Materials

- Material property dataset with limited samples (typically <1000)

- Computational resources for repeated model fitting

- GP software supporting kernel customization and hyperparameter optimization

Procedure

Outer Loop Configuration

- Split full dataset into K folds (typically 5 or 10)

- For each fold i = 1 to K:

- Set aside fold i as test set

- Use remaining K-1 folds as working data for inner loop

Inner Loop Hyperparameter Optimization

- Split working data into L folds (typically 3-5)

- For each hyperparameter configuration:

- Train on L-1 folds, validate on held-out fold

- Repeat for all L validation folds

- Compute average validation performance across folds

- Select hyperparameters with best average validation performance

Outer Loop Evaluation

- Train model on all K-1 working folds using selected hyperparameters

- Evaluate model performance on held-out test fold i

- Store performance metrics and hyperparameter values

Final Model Training

- Compute average of best hyperparameters across outer folds

- Train final model on entire dataset using averaged hyperparameters

- This final model is used for subsequent predictions on new materials

Critical Notes

- Nested cross-validation provides essentially unbiased performance estimates but is computationally expensive

- The final model should always be trained on the complete dataset using hyperparameters determined through the nested procedure

- This approach prevents the optimistic bias that occurs when hyperparameters are optimized using the entire dataset [13]

Application in Materials Science: Case Studies

Predicting High-Entropy Alloy Properties

Gaussian processes have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting properties of complex material systems such as high-entropy alloys (HEAs). In a comprehensive study comparing surrogate models for HEA property prediction, conventional GPs, Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs), and other machine learning approaches were evaluated on a hybrid dataset containing both experimental and computational properties [1]. The DGPs, which compose multiple GP layers to capture hierarchical nonlinear relationships, showed particular advantage in modeling the complex composition-property relationships in the 8-component Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V system [1].

The kernel selection for such multi-fidelity problems often involves combining stationary kernels (like SE) with non-stationary components to capture global trends and local variations. For HEA properties that exhibit correlations (e.g., yield strength and hardness often relate to underlying strengthening mechanisms), multi-task kernels that model inter-property correlations can significantly improve prediction accuracy, especially when some properties have abundant data while others are data-sparse [1].

Land Cover Classification with Hyperparameter Optimization

In remote sensing applications for material-like classification tasks, combining Bayesian hyperparameter optimization with K-fold cross-validation has demonstrated significant improvements in model accuracy. Researchers achieved a 2.14% improvement in overall accuracy for land cover classification using ResNet18 models when implementing this enhanced hyperparameter optimization approach [12]. The study optimized hyperparameters including learning rate, gradient clipping threshold, and dropout rate, demonstrating that proper hyperparameter tuning is as crucial as model architecture for achieving state-of-the-art performance [12].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Gaussian Process Modeling in Materials Research

| Tool Name | Implementation | Key Features | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn | Python | Simple API, built on NumPy, limited hyperparameter tuning options | Quick prototyping, educational use, small to medium datasets [7] |

| GPflow | TensorFlow | Flexible hyperparameter optimization, straightforward model construction | Production systems, complex kernel designs, TensorFlow integration [7] |

| GPyTorch | PyTorch | High flexibility, GPU acceleration, modern research features | Large-scale problems, custom model architectures, PyTorch ecosystems [7] |

| GPML | MATLAB | Comprehensive kernel library, well-established codebase | MATLAB environments, traditional statistical modeling [10] |

| STK | Multiple | Small-scale, simple problems, didactic purposes | Learning GP concepts, small material datasets [9] |

Gaussian process models offer a powerful framework for material property prediction, combining flexible function approximation with inherent uncertainty quantification. The core components—kernels, mean functions, and hyperparameters—work in concert to determine model behavior and predictive performance. Kernel selection defines the fundamental characteristics of the function space, with composite kernels enabling the modeling of complex, multi-scale material behavior. While often secondary to kernels, mean functions provide valuable incorporation of physical knowledge, particularly for extrapolation tasks. Hyperparameter optimization completes the model specification, with advanced techniques like nested cross-validation providing robust performance estimates for scientific applications.

As materials informatics continues to evolve, the thoughtful integration of domain knowledge through careful specification of these core GP components will remain essential for extracting meaningful insights from increasingly complex material datasets. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a foundation for researchers to implement Gaussian process models effectively in their material discovery workflows.

Uncertainty quantification (UQ) has emerged as a cornerstone of reliable data-driven research in materials science. It provides a framework for assessing the reliability and robustness of predictive models, which is crucial for informed decision-making in materials design and discovery [14]. In this context, uncertainties are often categorized into aleatoric and epistemic types, a distinction with roots in 17th-century philosophical papers [15]. Aleatoric uncertainty stems from inherent stochasticity or noise in the system, while epistemic uncertainty arises from a lack of knowledge or limited data [14] [16]. However, recent research reveals that this seemingly clear dichotomy is often blurred in practice, with definitions sometimes directly contradicting each other and the two uncertainties becoming intertwined [15] [17].

The deployment of Gaussian process (GP) models has become particularly valuable for UQ in materials research, especially in "small data" problems common in the field, where experimental or computational results may be limited to several dozen outputs [18]. Unlike data-hungry neural networks, GPs provide good predictive capability based on relatively modest data needs and come with inherent, objective measures of prediction credibility [18] [14]. This application note explores the critical role of UQ, examines the aleatoric-epistemic uncertainty spectrum within materials research, and provides detailed protocols for implementing GP models that effectively quantify both types of uncertainty.

Theoretical Foundation: The Aleatoric-Epistemic Spectrum

Contradictions in the Uncertainty Dichotomy

The conventional definition of epistemic uncertainty describes it as reducible uncertainty that can be decreased by training a model with more data from new regions of the input space. In contrast, aleatoric uncertainty is often defined as irreducible uncertainty caused by noisy data or missing features that prevent definitive predictions regardless of model quality [15]. However, several conflicting schools of thought exist regarding how to precisely define and measure these uncertainties, leading to practical challenges.

Table 1: Conflicting Schools of Thought on Epistemic Uncertainty

| School of Thought | Main Principle | Contradiction |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Possible Models | Epistemic uncertainty reflects how many models a learner believes fit the data [15]. | A learner with only two possible models (θ=0 or θ=1) could represent either maximal or minimal epistemic uncertainty depending on the definition used. |

| Disagreement | Epistemic uncertainty is measured by how much possible models disagree about outputs [15]. | |

| Data Density | Epistemic uncertainty is high when far from training examples and low within the training dataset [15]. |

These definitional conflicts highlight that the strict dichotomy between aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty may be overly simplistic for many practical tasks [15]. As noted by Gruber et al., "a simple decomposition of uncertainty into aleatoric and epistemic does not do justice to a much more complex constellation with multiple sources of uncertainty" [15].

Intertwined Uncertainties in Practice

In real-world materials science applications, aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties often coexist and interact, making their clean separation challenging [19]. For instance, in material property predictions, aleatoric uncertainty often results from stochastic mechanical, geometric, or loading properties that are not adopted as explanatory inputs to the surrogate model [14]. Experimental measurements also contain inherent variability (aleatoric uncertainty), while the models used to interpret them suffer from limited data and approximations (epistemic uncertainty) [1] [16].

Attempts to additively decompose predictive uncertainty into aleatoric and epistemic components can be problematic because these uncertainties are often intertwined in practice [15]. Research has shown that aleatoric uncertainty estimation can be unreliable in out-of-distribution settings, particularly for regression, and that aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties interact with each other in ways that partially violate their standard definitions [15].

Gaussian Process Models for Uncertainty Quantification

GP Fundamentals for Materials Research

Gaussian processes provide a powerful, non-parametric Bayesian framework for regression and uncertainty quantification, making them particularly well-suited for materials research where data is often limited [18] [14]. A GP defines a distribution over functions, where any finite set of function values has a joint Gaussian distribution [20]. This is fully specified by a mean function ( m(\mathbf{x}) ) and covariance kernel ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') ):

$$ f(\mathbf{x}) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(\mathbf{x}), k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}')) $$

The kernel function ( k ) determines the covariance between function values at different input points and encodes prior assumptions about the function's properties (smoothness, periodicity, etc.) [20]. A key advantage of GPs is their analytical tractability under Gaussian noise assumptions, allowing exact Bayesian inference [20].

For materials science applications, GPs offer two crucial capabilities: (1) they provide accurate predictions even with small datasets, and (2) they naturally quantify predictive uncertainty, which is essential for guiding experimental design and materials optimization [14] [1].

Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process Regression

Standard GP models typically assume homoscedastic noise (constant variance across all inputs), which often fails to capture the varying noise levels in real materials data [14]. Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process Regression (HGPR) addresses this limitation by modeling input-dependent noise, providing a more nuanced quantification of aleatoric uncertainty.

Table 2: Comparison of Gaussian Process Variants for Materials Science

| Model | Uncertainty Quantification Capabilities | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional GP (cGP) | Captures epistemic uncertainty well; assumes constant aleatoric uncertainty [1]. | Problems with uniform measurement error; initial exploratory studies. |

| Heteroscedastic GP (HGPR) | Separates epistemic and input-dependent aleatoric uncertainty [14]. | Data with varying measurement precision; multi-fidelity data integration. |

| Deep GP (DGP) | Captures complex, non-stationary uncertainties through hierarchical modeling [1]. | Highly complex composition-property relationships; multi-task learning. |

| Multi-task GP (MTGP) | Models correlations between different property predictions [1]. | Predicting multiple correlated material properties simultaneously. |

HGPR models heteroscedasticity by incorporating a latent function that models the input-dependent noise variance. This approach has been successfully applied to microstructure-property relationships, where aleatoric uncertainty results from random placement and orientation of microstructural features like voids or inclusions [14]. For example, in predicting effective stress in microstructures with elliptical voids, HGPR can capture how uncertainty varies with void aspect ratio and volume fraction, unlike homoscedastic models [14].

Figure 1: HGPR workflow for material property prediction, showing how input features are processed through latent functions to estimate both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Heteroscedastic GP for Microstructure-Property Relationships

This protocol details the implementation of an HGPR model for predicting material properties with quantified uncertainties, specifically designed for microstructure-property relationships where heteroscedastic behavior is observed [14].

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

- Input Features: Extract microstructural characteristics (e.g., volume fraction, aspect ratio of inclusions, spatial distribution metrics) from microscopy images or simulation data.

- Output Variable: Measure or compute the target property (e.g., effective stress, yield strength) through experimental testing or finite element analysis.

- Data Splitting: Partition data into training (70-80%), validation (10-15%), and test sets (10-15%), ensuring representative sampling across the input space. For sparse data, consider cross-validation.

Model Implementation

- Mean Function: Use a constant or linear mean function for simplicity, or a separate GP for the mean if prior knowledge is available.

- Covariance Kernel: Select a stationary kernel (e.g., Radial Basis Function) for the mean function and a separate kernel for the variance function.

Heteroscedastic Noise Model: Implement a polynomial regression noise model to capture input-dependent noise patterns while maintaining interpretability [14]:

$$ \sigma^2(\mathbf{x}) = \exp\left(\sum{i=0}^{d} \alphai \phi_i(\mathbf{x})\right) $$

where ( \phii(\mathbf{x}) ) are polynomial basis functions and ( \alphai ) are coefficients.

- Prior Selection: Place priors on hyperparameters to guide the learning process and prevent overfitting, particularly important with limited data.

Model Training and Inference

- Marginal Likelihood Optimization: Maximize the approximate Expected Log Predictive Density (ELPD) to learn hyperparameters for both mean and variance functions.

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC): For full Bayesian inference, use MCMC methods to sample from the posterior distribution of hyperparameters.

- Predictive Distribution: Generate predictive distributions for new inputs that naturally separate epistemic uncertainty (from posterior over functions) and aleatoric uncertainty (from input-dependent noise).

Protocol: Deep Gaussian Processes for High-Entropy Alloy Design

This protocol implements a DGP framework for predicting multiple correlated properties of high-entropy alloys (HEAs), leveraging hierarchical modeling to capture complex uncertainty structures [1].

Multi-Task Data Integration

- Data Collection: Assemble a hybrid dataset combining experimental measurements (e.g., yield strength, hardness, elongation) with computational predictions (e.g., stacking fault energy, valence electron concentration).

- Handle Missing Data: DGPs naturally accommodate heterotopic data (where different outputs are measured for different inputs) through likelihood functions that only incorporate observed data.

- Feature Selection: Include compositional features (elemental concentrations), processing conditions, and structural descriptors as inputs.

DGP Architecture Design

Layer Composition: Construct a hierarchy of 2-3 GP layers, transforming inputs through composed Gaussian processes:

$$ f(\mathbf{x}) = fL(f{L-1}(\dots f_1(\mathbf{x}))) $$

where each ( f_l ) is a GP.

- Prior Guidance: Infuse machine-learned priors from encoder-decoder networks to initialize the DGP, improving convergence and performance [1].

- Covariance Specification: Use multi-task kernels that model correlations between different material properties, allowing information transfer between tasks.

Model Training and Prediction

- Variational Inference: Employ stochastic variational inference to approximate the posterior, enabling scalability to larger datasets.

- Uncertainty Decomposition: Analyze the predictive variance to distinguish between data noise (aleatoric) and model uncertainty (epistemic) across the composition space.

- Bayesian Optimization Integration: Use the DGP surrogate within a Bayesian optimization loop to guide the search for optimal alloy compositions, leveraging the acquisition function that balances exploration (high epistemic uncertainty) and exploitation (promising mean predictions).

Application Case Studies

Microstructure-Based Effective Stress Prediction

In applying Protocol 4.1 to predict effective stress in microstructures with voids, researchers found that HGPR successfully captured heteroscedastic behavior where uncertainty increased with void aspect ratio and volume fraction [14]. Specifically, microstructures with elliptical voids (aspect ratio of 3) exhibited greater scatter in predicted effective stress compared to those with circular voids (aspect ratio of 1), particularly at higher volume fractions. The HGPR model provided accurate uncertainty estimates that reflected the true variability in the finite element simulation data, enabling more reliable predictions for material design decisions.

Multi-Property HEA Prediction

Implementation of Protocol 4.2 for the Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V HEA system demonstrated that DGPs with prior guidance significantly outperformed conventional GPs, neural networks, and XGBoost in predicting correlated properties like yield strength, hardness, and elongation [1]. The DGP framework effectively handled the sparse, noisy experimental data while leveraging information from more abundant computational predictions, providing well-calibrated uncertainty estimates that guided successful alloy optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Uncertainty-Quantified Materials Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Framework | Provides probabilistic predictions with inherent uncertainty quantification [14] [1]. | Use GPyTorch or GPflow for flexible implementation; prefer DGPs for complex, hierarchical data. |

| Heteroscedastic Likelihood | Models input-dependent noise for accurate aleatoric uncertainty estimation [14]. | Implement with variational inference for stability; polynomial noise models offer interpretability. |

| Multi-Task Kernels | Captures correlations between different material properties [1]. | Essential for multi-fidelity modeling; allows information transfer between data-rich and data-poor properties. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Guides experimental design by balancing exploration and exploitation [1]. | Use expected improvement or upper confidence bound acquisition functions with GP surrogates. |

| Variational Inference | Enables scalable Bayesian inference for large datasets or complex models [1]. | Necessary for training DGPs; provides practical alternative to MCMC for many applications. |

Effective uncertainty quantification through Gaussian process models represents a critical capability for advancing materials research. While the traditional aleatoric-epistemic dichotomy provides a useful conceptual framework, practical applications in materials science require more nuanced approaches that acknowledge the intertwined nature of these uncertainties and their dependence on specific contexts and tasks. Heteroscedastic and deep Gaussian processes offer powerful tools for quantifying both types of uncertainty, enabling more reliable predictions and informed decision-making in materials design and optimization. As the field progresses, moving beyond strict categorization toward task-specific uncertainty quantification focused on particular sources of uncertainty will yield the most significant advances in reliable materials property prediction.

Why GPs for Materials? Advantages in Data-Scarce Regimes and Interpretability

Gaussian Processes (GPs) have emerged as a powerful machine learning tool for material property prediction, offering distinct advantages in scenarios where experimental or computational data are limited. Within the broader context of a thesis on Gaussian Process models, this document details their specific utility in materials science, where research is often constrained by the high cost of data acquisition. GPs excel in these data-scarce regimes by providing robust uncertainty quantification and by allowing for the integration of pre-existing physical knowledge, which enhances their predictive performance and interpretability [21] [22]. These features make GPs particularly well-suited for guiding experimental design and accelerating the discovery of new materials. This application note provides a detailed overview of GP advantages, supported by quantitative data, and offers protocols for their implementation in materials research.

Key Advantages and Quantitative Performance

The core strengths of GP models in materials science lie in their foundational Bayesian framework. The following table summarizes these key advantages and their practical implications for research.

Table 1: Core Advantages of Gaussian Process Models in Materials Science

| Advantage | Mechanism | Benefit for Materials Research |

|---|---|---|

| Native Uncertainty Quantification | Provides a full probabilistic prediction, outputting a mean and variance for each query point [22]. | Identifies regions of high uncertainty in the design space, guiding experiments to where new data is most valuable. |

| Data Efficiency | As a non-parametric Bayesian method, GPs are robust to overfitting, even with small datasets [22]. | Reduces the number of costly experiments or simulations required to build a reliable predictive model. |

| Integration of Physical Priors | Physics-based models can be incorporated as a prior mean function, with the GP learning the discrepancy from this prior [21]. | Leverages existing domain knowledge (e.g., from CALPHAD or analytical models) to improve accuracy and extrapolation. |

| Interpretability & Transparency | Model behavior is governed by a kernel function, whose hyperparameters (e.g., length scales) can reveal the importance of different input features [22]. | Provides insights into the underlying physical relationships between a material's composition/processing and its properties. |

The practical performance of these advantages is evidenced in recent studies. The table below compares the error rates of different models for predicting material properties, highlighting the effectiveness of GPs and physics-informed extensions.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of GP Models in Materials Property Prediction

| Study & Task | Model(s) Evaluated | Performance Metric | Key Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Stability Classification [21] | Physics-Informed GPC (with CALPHAD prior) | Model Validation Accuracy | Substantially improved accuracy over purely data-driven GPCs and CALPHAD alone. |

| Formation Energy Prediction [23] | Ensemble Methods (Random Forest, XGBoost) vs. Gaussian Process (GP) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Ensemble methods (MAE: ~0.1-0.2 eV/atom) outperformed the GP model and classical interatomic potentials. |

| Active Learning for Fatigue Strength [24] | CA-SMART (GP-based) vs. Standard BO | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) & Data Efficiency | Demonstrated superior accuracy and faster convergence with fewer experimental trials. |

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Physics-Informed GP Classifier for Phase Stability

This protocol outlines the methodology for integrating physics-based knowledge into a Gaussian Process Classifier (GPC) to predict the stability of solid-solution phases in alloys, as demonstrated in [21].

- Objective: To create a classification model that accurately predicts the formation of a single-phase solid solution in High-Entropy Alloys by combining CALPHAD simulations with experimental XRD data.

Research Reagents & Computational Tools:

- CALPHAD Software: Generates the initial physics-based probability of phase stability for a given alloy composition [21].

- Experimental Dataset: A publicly available XRD dataset for High-Entropy Alloys, used as ground-truth labels (stable/not stable) [21].

- Gaussian Process Software: A programming environment with GP libraries (e.g., Python's

scikit-learnor GPy) for model implementation.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Generate Prior Data: Use CALPHAD to compute the probability of solid-solution phase stability, ( m(x) ), for all alloy compositions, ( x ), in the training and test sets.

- Define the Latent GP: Construct a latent GP, ( a(x) ), where the prior mean function is set to the CALPHAD-predicted probabilities, ( m(x) ) [21].

- Train the Model: Train the latent GP as a regressor on the binary experimental data (converted to numerical labels, e.g., -5 and 5 for class 0 and 1) using the observed experimental labels, ( tN ), and the CALPHAD priors, ( m(XN) ). The model learns the error between the CALPHAD prior and the experimental truth.

- Compute Posterior: For a new alloy composition ( x^* ), calculate the posterior mean of the latent function, ( μ(x^) ), using the standard GP posterior equation incorporating the prior ( m(x^) ) [21].

- Squash through Sigmoid: Pass the posterior mean ( μ(x^) ) through a logistic sigmoid function, ( σ(·) ), to convert it into a valid class probability between 0 and 1 [21]: ( y(x^) = σ(μ(x^*)) ).

- Model Validation: Validate the final physics-informed GPC model by comparing its predictions against a hold-out set of experimental XRD data.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-step process:

Protocol 2: Active Learning for Constrained Property Prediction with CA-SMART

This protocol details the implementation of the Confidence-Adjusted Surprise Measure for Active Resourceful Trials (CA-SMART), a GP-based active learning framework designed for efficient materials discovery under resource constraints [24].

- Objective: To iteratively and efficiently discover materials that meet a specific property threshold (e.g., minimum yield strength) by selecting the most informative experiments.

Research Reagents & Computational Tools:

- Initial Dataset: A small initial dataset of material compositions/processing parameters and their corresponding property measurements.

- Gaussian Process Model: Serves as the surrogate model to approximate the property landscape.

- Acquisition Function: The Confidence-Adjusted Surprise (CAS) metric, which balances surprise and model confidence.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initialize Surrogate Model: Train a GP model on the initial small dataset of material compositions/processing parameters and their measured properties.

- Query the Design Space: Use the GP to predict the mean and uncertainty (variance) for all candidate materials in the design space.

- Calculate Confidence-Adjusted Surprise (CAS): For each candidate, compute the CAS. This metric amplifies surprises (discrepancies between prediction and observation) in regions where the model is confident, and discounts surprises in highly uncertain regions [24].

- Select Next Experiment: Choose the candidate material with the highest CAS value for the next round of experimental testing.

- Update Model: Incorporate the new experimental data (composition and measured property) into the training set.

- Iterate: Retrain the GP model and repeat steps 2-5 until a material meeting the target property constraint is identified or the experimental budget is exhausted.

The iterative loop of this active learning process is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential computational tools and data resources for implementing GP models in materials science research, as identified in the cited studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Function in GP Modeling | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| CALPHAD Software | Provides physics-informed prior mean function for the GP model [21]. | Predicting phase stability in alloy design. |

| Classical Interatomic Potentials | Used in MD simulations to generate input features for ensemble or GP models when DFT data is scarce [23]. | Predicting formation energy and elastic constants of carbon allotropes. |

| Materials Databases (e.g., Materials Project) | Source of crystal structures and DFT-calculated properties for training and validation [23]. | Providing ground-truth data for model training. |

| GPR Software (e.g., scikit-learn, GPflow) | Core platform for implementing Gaussian Process Regression and Classification. | Building the surrogate model for property prediction and active learning. |

| Active Learning Framework (e.g., CA-SMART) | Algorithm for intelligent selection of experiments based on model uncertainty and surprise [24]. | Accelerating the discovery of high-strength steel. |

Gaussian process (GP) models have emerged as a powerful tool for the prediction of material properties, offering a robust framework that combines flexibility with principled uncertainty quantification. Within materials science, the discovery and development of new alloys, polymers, and functional materials increasingly rely on data-driven approaches where GP models serve as efficient surrogates for expensive experiments and high-fidelity simulations [2] [1]. The workflow for implementing these models—spanning data preparation, model development, prediction, and validation—forms a critical pathway for accelerating materials discovery. This protocol details the comprehensive application of GP workflows specifically within the context of material property prediction, providing researchers with a structured methodology for building reliable predictive models. By integrating techniques such as multi-task learning and deep hierarchical structures, GP models can effectively navigate the complex, high-dimensional spaces typical of materials informatics while providing essential uncertainty estimates that guide experimental design and validation [1] [6].

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

The foundation of any successful GP model lies in the quality and appropriate preparation of the input data. In materials science, data often originates from diverse sources including high-throughput computations, experimental characterization, and existing literature, each with unique noise characteristics and potential missing values.

Data Collection and Preprocessing

Initial data collection should comprehensively capture the relevant feature space, which for material property prediction typically includes compositional information, processing conditions, structural descriptors, and prior knowledge from physics-based models [1] [6]. Handling missing values requires careful consideration of the underlying missingness mechanism; common approaches include multiple imputation, which has been shown to produce better calibrated models compared to complete case analysis or mean imputation [25]. For outcome definition, particularly when using electronic health records or disparate data sources, consistent and validated definitions are crucial. Relying on incomplete outcome definitions (e.g., using only diagnosis codes without medication data) can lead to systematic underestimation of risk, while overly broad definitions may introduce noise [25].

Feature Engineering and Selection

Feature engineering transforms raw materials data into representations more suitable for GP modeling. The group contribution (GC) method is particularly valuable, where molecules or alloys are decomposed into functional groups, and their contributions to properties are learned [3]. These GC descriptors can be combined with molecular weight or other fundamental descriptors to create a compact yet informative feature set. For high-entropy alloys, features often include elemental compositions, thermodynamic parameters (e.g., mixing enthalpy, entropy), electronic parameters (e.g., valence electron concentration), and structural descriptors [1]. Feature selection should prioritize physically meaningful descriptors that align with domain knowledge while avoiding excessive dimensionality that could challenge GP scalability.

Table 1: Common Feature Types in Materials Property Prediction

| Feature Category | Specific Examples | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Compositional | Elemental fractions, Dopant concentrations | Alloy design, Ceramics |

| Structural | Crystal system, Phase fractions, Microstructural images | Polycrystalline materials |

| Thermodynamic | Mixing enthalpy, Entropy, Phase stability | High-entropy alloys |

| Electronic | Valence electron concentration, Electronegativity | Functional materials |

| Descriptors | Group contribution parameters, Molecular weight | Polymer design, Solvent selection |

Data Splitting and Normalization

Appropriate data splitting is essential for validating model generalizability. While random splits are common, for materials data, structured approaches such as stratified sampling based on key compositional classes or scaffold splits that separate chemically distinct structures may provide more realistic assessment of performance on novel materials [3]. Data normalization standardizes features to comparable scales; standardization (centering to zero mean and scaling to unit variance) is typically recommended for GP models to ensure smooth length-scale estimation across dimensions.

Model Development and Training

Selecting and training an appropriate GP model requires careful consideration of architectural choices, kernel functions, and inference methodologies tailored to the specific materials prediction task.

GP Model Selection

The choice of GP architecture should align with the problem characteristics. Conventional GPs (cGP) work well for single-property prediction with relatively small datasets (typically <10,000 points) and provide a solid baseline [1]. For multiple correlated properties, advanced architectures like Multi-Task GPs (MTGP) and Deep GPs (DGP) offer significant advantages. MTGPs explicitly model correlations between different material properties (e.g., strength and ductility), allowing for information transfer between tasks [2] [1]. DGPs employ a hierarchical composition of GPs to capture complex, non-stationary relationships without manual kernel engineering [26]. Recent studies demonstrate that DGP variants, particularly those incorporating hierarchical structures (hDGP-BO), show remarkable robustness and efficiency in navigating complex HEA design spaces [2].

Kernel Selection and Design

The kernel function defines the covariance structure and fundamentally determines the GP's generalization behavior. For materials applications, common choices include:

- Radial Basis Function (RBF): Captures smooth, stationary patterns; suitable for continuous material properties.

- Matérn: Offers flexibility in smoothness control; particularly useful for modeling noisy experimental data.

- Linear: Can encode linear relationships based on physical principles.

- Composite kernels: Combine multiple kernels to capture different characteristics (e.g., RBF + Periodic for crystalline materials).

Kernel selection should be guided by both data characteristics and domain knowledge, with the option to learn hyperparameters through marginal likelihood optimization [26].

Training and Inference

GP training involves optimizing kernel hyperparameters and noise variance by maximizing the marginal likelihood. For DGPs and MTGPs, variational inference approaches provide scalable approximations for deeper architectures [26]. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, particularly hybrid approaches combining Gibbs sampling with Elliptical Slice Sampling (ESS), offer fully Bayesian inference for uncertainty quantification, though at increased computational cost [26] [27]. Computational efficiency can be enhanced through sparse GP approximations when dealing with larger datasets (>10,000 points) [26].

Prediction and Validation

Robust validation methodologies are essential for establishing confidence in GP predictions and ensuring reliable deployment in materials discovery pipelines.

Prediction and Uncertainty Quantification

The primary advantage of GP models in materials science is their native uncertainty quantification alongside point predictions. For a new material composition ( x_* ), the GP predictive distribution provides both the expected property value (mean) and the associated uncertainty (variance) [3] [26]. This uncertainty decomposition includes epistemic uncertainty (from model parameters) and aleatoric uncertainty (inherent data noise), which is particularly valuable for guiding experimental design through Bayesian optimization [2]. In DGP architectures, uncertainty propagates through multiple layers, potentially providing more calibrated uncertainty estimates for complex, non-stationary response surfaces [26].

Validation Techniques and Metrics

Comprehensive validation should assess both predictive accuracy and uncertainty calibration using appropriate techniques:

- Holdout Validation: Reserving a portion of data exclusively for testing provides an unbiased performance estimate [28].

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: Particularly valuable for smaller materials datasets, this approach assesses model stability across different data partitions [28].

- Bootstrap Methods: Resampling with replacement evaluates model stability and uncertainty estimation reliability, especially beneficial with limited data [28].

Performance metrics should be selected based on the specific application:

- Accuracy, Precision, Recall: For classification tasks (e.g., phase prediction).

- R², RMSE, MAE: For continuous property prediction.

- ROC-AUC: For evaluating class separation capability.

- Negative Log Predictive Density (NLPD): Assesses quality of probabilistic predictions.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for GP Model Validation

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation in Materials Context |

|---|---|---|

| R² (Coefficient of Determination) | ( 1 - \frac{\sum(y-\hat{y})^2}{\sum(y-\bar{y})^2} ) | Proportion of property variance explained by model |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | ( \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum(y-\hat{y})^2} ) | Average prediction error in property units |

| MAE (Mean Absolute Error) | ( \frac{1}{n}\sum|y-\hat{y}| ) | Robust measure of average error |

| NLPD (Negative Log Predictive Density) | ( -\frac{1}{n}\sum\log p(y|x) ) | Quality of probabilistic predictions (lower is better) |

| Coverage Probability | ( \frac{1}{n}\sum I(y \in CI_{1-\alpha}) ) | Calibration of uncertainty intervals (should match (1-\alpha)) |

Advanced Validation Considerations

For materials-specific applications, several advanced validation approaches are recommended:

- Temporal Validation: When data is collected over time, validate on the most recent time periods to assess performance on future materials.

- Domain-Specific Validation: Test model performance on specific material classes or composition ranges of particular interest [28].

- External Validation: Evaluate the model on completely independent datasets from different sources or measurement techniques.

Validation should also assess calibration of uncertainty estimates—how well the predicted confidence intervals match the empirical coverage. miscalibrated uncertainty can mislead downstream decision-making in materials design [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a GP Model for HEA Property Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a GP model to predict mechanical properties in high-entropy alloys, based on methodologies successfully applied in recent studies [2] [1].

Materials and Data Sources

- Collect alloy composition data (elemental fractions for 5+ principal elements)

- Obtain property measurements (yield strength, hardness, modulus, etc.) from experiments or high-throughput calculations

- Compute derived descriptors (VEC, mixing enthalpy, atomic size difference)

- Software Requirements: Python with GPyTorch or GPflow, MATLAB with GPML, or R with GauPro for emulation [29]

Procedure

- Data Preparation (2-3 days)

- Clean data, handle missing values using multiple imputation [25]

- Compute additional features (thermodynamic/electronic parameters)

- Standardize all features to zero mean and unit variance

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

Model Selection and Training (1-2 days)

- Start with a conventional GP with RBF kernel as baseline

- For multiple properties, implement MTGP or DGP to capture correlations

- Optimize hyperparameters by maximizing marginal likelihood

- For Bayesian inference, implement MCMC sampling (2000-5000 iterations)

Validation and Testing (1 day)

- Evaluate on test set using R², RMSE, and NLPD

- Assess uncertainty calibration using coverage probability

- Compare against baseline models (linear regression, random forests)

Troubleshooting Tips

- For convergence issues in DGP training, reduce learning rate or use variational inference

- If predictions show high bias, consider more expressive kernels or deeper hierarchies

- For poor uncertainty calibration, adjust likelihood parameters or prior distributions

Protocol 2: Group Contribution-GP for Thermophysical Properties

This protocol details the hybrid GC-GP approach for predicting thermophysical properties of organic compounds and materials, building on recent advances in hybrid modeling [3].

Materials and Data Sources

- Gather experimental property data (boiling point, melting point, critical properties) from databases like CRC Handbook

- Compute group contribution descriptors using established methods (Joback-Reid, Marrero-Gani)

- Software Requirements: Python with scikit-learn or specialized GC-GP packages

Procedure

- Descriptor Calculation (1 day)

- Decompose molecular structures into functional groups

- Calculate group contribution values using established parameters

- Combine with molecular weight as additional descriptor

Model Development (2 days)

- Train GP using GC descriptors and molecular weight as inputs

- Compare against GC-only model to assess improvement

- Optimize kernel hyperparameters through likelihood maximization

Validation (1 day)

- Test on held-out compounds not in training set

- Evaluate using leave-one-group-out cross-validation

- Assess applicability domain through uncertainty examination

Expected Outcomes

- The GC-GP model should significantly outperform GC-only predictions (e.g., R² ≥0.85 for most properties) [3]

- Reliable uncertainty estimates that grow appropriately for molecules outside the training domain

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GP Workflows

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| GP Software Libraries | GPyTorch, GPflow (Python), GPML (MATLAB), GauPro (R) [29] | Core implementation of GP models and inference algorithms |

| Optimization Frameworks | Bayesian Optimization (BayesianOptimization, BoTorch) | Efficient global optimization for materials design using GP surrogates |

| Materials Databases | Materials Project, AFLOW, ICSD, CSD | Source of training data for composition-structure-property relationships |

| Descriptor Generation | RDKit, pymatgen, Matminer | Generate molecular and crystalline descriptors for feature engineering |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), Variational Inference | Bayesian inference for parameter and prediction uncertainties |

| Validation Tools | scikit-learn, custom calibration metrics | Model performance assessment and uncertainty calibration checking |

Workflow Visualization

GP Workflow for Materials Property Prediction

This comprehensive protocol has detailed the complete GP workflow for material property prediction, from initial data preparation through final model validation. The structured approach emphasizes the importance of appropriate data handling, thoughtful model selection, and rigorous validation—all essential components for building reliable predictive models in materials science. The integration of advanced GP architectures like DGPs and MTGPs with domain knowledge through group contribution methods or physical constraints represents the cutting edge of data-driven materials discovery [2] [3] [1]. By providing detailed experimental protocols and validation methodologies, this workflow serves as a practical guide for researchers seeking to implement GP models for their specific materials challenges. The inherent uncertainty quantification capabilities of GPs, combined with their flexibility to model complex nonlinear relationships, position them as invaluable tools in the accelerating field of materials informatics, particularly when deployed within active learning or Bayesian optimization frameworks for iterative materials design and discovery.

Advanced GP Methodologies and Their Applications in Material Informatics

Multi-Task Gaussian Processes (MTGPs) represent a powerful extension of conventional Gaussian Processes (cGPs) designed to model several correlated output tasks simultaneously. Unlike cGPs, which model each material property independently, MTGPs use connected kernel structures to learn and exploit both positive and negative correlations between related tasks, such as material properties that depend on the same underlying arrangement of matter [2]. This capability allows information to be shared across tasks, significantly improving prediction quality and generalization, especially when data for some properties is sparse [1] [30] [2]. In materials science, where properties like yield strength and hardness are often intrinsically linked, this approach provides a more efficient and data-effective paradigm for discovery and optimization.

Theoretical Foundation and Comparative Advantages

The mathematical rigor of MTGPs lies in their use of a shared covariance function that models the correlations between all pairs of tasks across the input space. This is often achieved through the Intrinsic Coregionalization Model (ICM), which uses a positive semi-definite coregionalization matrix to capture task relationships [2]. This framework enables MTGPs to perform knowledge transfer; a property with abundant data can improve the predictive accuracy for a data-sparse but correlated property [1] [30].

The table below summarizes a systematic comparison of MTGPs against other prominent surrogate models, highlighting their suitability for materials informatics challenges.

Table 1: Comparison of Surrogate Models for Material Property Prediction

| Model | Key Mechanism | Handles Multi-Output Correlations? | Uncertainty Quantification? | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Task GP (MTGP) | Connected kernel structures & coregionalization matrix [2] | Yes, explicitly [2] | Yes, native and calibrated [2] | Efficient knowledge transfer between correlated properties [1] [2] | Suboptimal for deeply hierarchical, non-linear data relationships [1] [2] |

| Conventional GP (cGP) | Single-layer Gaussian Process with a standard kernel | No, models properties independently [2] | Yes, native and calibrated [1] | Mathematical rigor and simplicity [2] | Inefficient for multi-task learning; ignores property correlations [2] |

| Deep GP (DGP) | Hierarchical composition of multiple GP layers [1] [2] | Yes, in a hierarchical manner [1] | Yes, native and calibrated [1] | Captures complex, non-linear and non-stationary behavior [1] [2] | Higher computational complexity [1] |

| Encoder-Decoder Neural Network | Deterministic encoding of input to latent space, then decoding to multiple outputs [1] [30] | Yes, implicitly through the latent representation [30] | No, unless modified (e.g., Bayesian neural networks) [1] | High expressive power; scalable for large datasets [1] | Requires large data to generalize; uncertainty is not native [1] [30] |

| XGBoost | Ensemble of boosted decision trees | No, requires separate models for each property [1] [30] | No, native [1] | High predictive accuracy and scalability [1] | Ignores inter-property correlations and lacks native uncertainty [1] |

Application in High-Entropy Alloy Design