From Virtual Screening to Real Solutions: How Active Learning Accelerates Inverse Materials Design

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of active learning (AL) to the challenge of inverse materials design.

From Virtual Screening to Real Solutions: How Active Learning Accelerates Inverse Materials Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of active learning (AL) to the challenge of inverse materials design. It covers the foundational principles of AL, explaining how it transforms the materials discovery pipeline from a trial-and-error process into a guided, data-efficient search. We detail current methodological approaches, including the integration of AL with generative models and molecular dynamics simulations, and provide practical insights for implementation in biomedical contexts, such as drug-like molecule and biomaterial discovery. The guide addresses common challenges in algorithm selection, sampling efficiency, and handling complex property landscapes, while comparing AL's performance against traditional high-throughput screening and other machine learning paradigms. Finally, we explore validation frameworks and real-world case studies, concluding with a synthesis of key takeaways and future implications for accelerating the development of novel therapeutics and medical materials.

What is Active Learning in Inverse Design? A Primer for Scientific Researchers

The evolution of materials discovery is marked by a fundamental shift from a traditional forward design paradigm to a targeted inverse design approach. This document, framed within a thesis on active learning for inverse materials design, details the application notes and protocols underpinning this transition, with emphasis on methodologies relevant to advanced materials and pharmaceutical development.

Paradigm Comparison & Quantitative Metrics

The core distinction between the two paradigms is summarized in the following table, which contrasts their foundational principles, workflows, and performance metrics based on recent literature and benchmark studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Forward vs. Inverse Design Paradigms

| Aspect | Forward Design (Traditional) | Inverse Design (Targeted) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | "Synthesize, then characterize and hope for desired properties." | "Define target properties first, then compute and synthesize the optimal material." |

| Workflow Direction | Composition/Structure → Property Prediction/Measurement | Target Property → Candidate Composition/Structure |

| Primary Driver | Empirical experimentation, chemical intuition, serendipity. | Computational prediction, generative models, optimization algorithms. |

| High-Throughput Capability | Limited by serial synthesis and characterization speed. | Enabled by high-throughput virtual screening and generative design. |

| Success Rate (Typical) | Low (<5% hit rate in unexplored spaces). | Significantly higher (20-40% for well-defined targets with robust models). |

| Time-to-Discovery | Years to decades for novel classes. | Months to years for accelerated identification of candidates. |

| Key Enabling Tools | Combinatorial libraries, robotic synthesis, XRD, NMR. | Density Functional Theory (DFT), Molecular Dynamics (MD), Generative AI, Active Learning Loops. |

Core Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Active Learning Cycle for Inverse Molecular Design

Objective: To iteratively discover molecules or materials with a target property (e.g., binding affinity, bandgap, ionic conductivity) using a closed-loop, computationally guided process.

- Initial Dataset Curation: Assemble a seed dataset of known compounds with associated property data. Size can be small (50-500 entries). Represent structures as numerical descriptors (e.g., Morgan fingerprints, SMILES, graph representations) or atomic coordinates.

- Surrogate Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Graph Neural Network, Random Forest, Gaussian Process) on the seed dataset to predict the target property from the structural input.

- Candidate Generation: Use a generative algorithm (e.g., variational autoencoder, genetic algorithm, reinforcement learning agent) to propose a large pool (10⁴–10⁶) of novel candidate structures within defined chemical validity rules.

- Virtual Screening & Acquisition: Use the trained surrogate model to predict properties for the candidate pool. Select candidates for the next iteration using an acquisition function (e.g., expected improvement, probability of improvement, uncertainty sampling) that balances exploration and exploitation.

- High-Fidelity Validation: Subject the top-acquired candidates (typically 5-20) to high-fidelity simulation (e.g., DFT, full MD, docking) or actual experimental synthesis and characterization to obtain ground-truth property values.

- Loop Closure: Add the newly validated candidates and their properties to the training dataset. Retrain the surrogate model with the expanded dataset. Return to Step 3.

- Termination: The cycle continues until a candidate meets the target property threshold or a predefined computational budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2.2: High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) for Porous Materials

Objective: To identify metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) or covalent organic frameworks (COFs) with optimal gas adsorption properties (e.g., CO₂ capacity, CH₄ deliverable capacity).

- Database Preparation: Access a pre-computed database of hypothetical or real porous material structures (e.g., the Computation-Ready, Experimental (CoRE) MOF database). Ensure structures are cleaned and atom-typed correctly.

- Property Calculation via Molecular Simulation: a. Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC): Perform GCMC simulations for the target gas (e.g., CO₂, N₂, CH₄) at specified conditions (e.g., 298 K, 1 bar for storage; 5 bar for adsorption, 65 bar for deliverable capacity). b. Force Field Selection: Use validated force fields (e.g., UFF, DREIDING) with appropriate partial charges (e.g., EQeq, DDEC) for gas-framework interactions. c. Simulation Details: Run a minimum of 5×10⁶ steps for equilibration, followed by 5×10⁶ steps for production. Use the RASPA or LAMMPS software packages.

- Data Aggregation & Analysis: Extract the absolute uptake and deliverable capacity from the simulation output. Compile results into a searchable database.

- Pareto Front Analysis: Plot key performance metrics (e.g., CO₂ uptake vs. CH₄ deliverable capacity) to identify non-dominated candidates that offer the best trade-offs. These form the Pareto front for targeted experimental validation.

Visualizations of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Forward vs Inverse Design Decision Tree

Diagram 2: Active Learning Loop for Inverse Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Inverse Materials Design Research

| Resource Category | Specific Example(s) | Primary Function & Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Materials Project, CoRE MOF DB, Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), PubChem, ZINC. | Provides seed crystal structures, molecular data, and pre-computed properties for training surrogate models and benchmarking. |

| Property Prediction Software | Quantum ESPRESSO (DFT), LAMMPS/GROMACS (MD), AutoDock Vina (Docking), SchNet/GNN models. | Performs high-fidelity calculations for target properties (electronic, mechanical, binding) to validate ML predictions or generate training data. |

| Generative & ML Libraries | PyTorch/TensorFlow, RDKit, matminer, DeepChem, GAUCHE (for molecules), AIRS. | Enables the building, training, and deployment of generative models and property predictors central to the inverse design cycle. |

| Active Learning Frameworks | Olympus, ChemOS, deephyper. | Provides modular platforms to automate the iterative loop of proposal, measurement, and model updating. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Liquid handling robots (e.g., Opentrons), automated synthesis platforms, rapid serial characterization (e.g., HPLC-MS). | Accelerates the experimental validation step (Protocol 2.1, Step 5), closing the active learning loop rapidly with real-world data. |

| Chemical Building Blocks | Diverse libraries of organic linkers, metal nodes (for MOFs), amino acids, fragment libraries. | Provides the physical components for the synthesis of computationally identified lead candidates, ensuring synthetic tractability. |

This document details the application of active learning (AL) core loops to inverse materials design, a paradigm focused on discovering materials with predefined target properties. The broader thesis posits that AL—by strategically selecting the most informative experiments—drastically accelerates the discovery of advanced functional materials (e.g., high-temperature superconductors, organic photovoltaics, solid-state electrolytes) and bioactive compounds, reducing the experimental and computational cost of exploration in vast chemical spaces.

The Core Loop Protocol: Query, Train, Iterate

This protocol establishes a generalized, iterative framework for closed-loop discovery.

Protocol 2.1: Standard Active Learning Loop for Inverse Design

Objective: To implement an automated cycle for proposing optimal candidate materials or molecules for synthesis and testing.

Materials & Software:

- Initial Dataset: A structured dataset (e.g., CSV, .xyz, SMILES) containing representations (descriptors, fingerprints, graphs) and associated property labels for a known, limited set of compounds.

- AL Software Platform: Custom Python scripts utilizing libraries (scikit-learn, DeepChem, PyTorch, TensorFlow, GPyTorch) or specialized platforms (ChemOS, ATOM3D, MAterials Graph Network (MAGNET)).

- Property Predictor: A machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process Regressor, Graph Neural Network, Random Forest).

- Acquisition Function: A function quantifying the "informativeness" of an unlabeled candidate (e.g., Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound, Predictive Entropy).

Procedure:

- Initialization (Bootstrapping):

- Assemble a small, diverse seed dataset (D_initial) of ~50-200 labeled samples (property measured experimentally or via high-fidelity simulation).

- Define the vast, unlabeled candidate pool (P) from a generative model or enumerated library (e.g., 10^5-10^9 candidates).

- Choose an appropriate featurization for candidates (e.g., Magpie descriptors, Morgan fingerprints, Crystal Graph).

Model Training (Train):

- Train a surrogate machine learning model (M) on the current labeled dataset (D_current) to predict the target property (e.g., bandgap, ionic conductivity, binding affinity).

- Validate model performance using hold-out or cross-validation. Record performance metrics (Table 1).

Candidate Query & Selection (Query):

- Use the trained model M to predict properties and associated uncertainties for all candidates in pool P.

- Apply the chosen acquisition function A(x) to each candidate's prediction.

- Select the top k candidates (batch size typically 1-10) with the highest A(x) scores for experimental validation.

Experimental Iteration (Iterate):

- Labeling: Synthesize and characterize the k selected candidates to obtain ground-truth property labels (This is the experimental bottleneck).

- Dataset Update: Add the newly labeled (candidate, property) pairs to Dcurrent, creating Dnew.

- Loop: Return to Step 2 (Train) using D_new.

- Termination: Loop continues until a performance target is met (e.g., discovery of material with property > threshold) or a resource budget (iterations, time) is exhausted.

Diagram: The Core Active Learning Loop for Materials Discovery

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Representative Performance Metrics of Active Learning in Materials & Molecule Discovery

| Study Focus (Year) | Search Space Size | Initial Training Set | AL Method (Acquisition) | Key Result (vs. Random Search) | Iterations to Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic LED Emitters (2022) | ~3.2e5 molecules | 100 | GPR w/ Expected Improvement | Discovered top candidate 4.5x faster | ~40 (vs. ~180 random) |

| Li-ion Solid Electrolytes (2023) | ~1.2e4 compositions | 50 | Graph Neural Network w/ Upper Confidence Bound | Achieved target conductivity with 60% fewer experiments | 15 (vs. 38 extrapolated) |

| Porous Organic Cages (2021) | ~7e3 hypothetical cages | 30 | Random Forest w/ Uncertainty Sampling | Identified top 1% performers after evaluating only 4% of space | 240 evaluations |

| CO2 Reduction Catalysts (2023) | ~2e5 alloys (surfaces) | 120 | Bayesian NN w/ Thompson Sampling | Found 4 high-activity candidates; reduced DFT calls by ~70% | ~50 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: High-Throughput Synthesis & Characterization for AL Validation (e.g., Perovskite Solar Cells)

Objective: To experimentally label the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of a thin-film semiconductor candidate proposed by the AL loop.

Materials:

- Precursor Solutions: Prepared from lead halide (PbX2) and organic cation (e.g., methylammonium iodide) salts in dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Substrates: Cleaned glass or ITO-coated glass.

- Equipment: Spin coater, hot plate, glove box (N2 atmosphere), UV-Vis spectrometer, integrating sphere with photoluminescence spectrometer.

Procedure:

- Thin-Film Deposition: In a nitrogen glovebox, filter the precursor solution for candidate composition 'X'. Spin-coat onto substrate. Anneal on a hot plate at 100°C for 10 minutes.

- Optical Characterization:

- Measure UV-Vis absorption spectrum (300-800 nm).

- For PLQY: Place film inside integrating sphere. Excite with a calibrated 450 nm laser at low intensity. Measure the full emission spectrum.

- Calculate PLQY using the equation: PLQY = (Emission Photons) / (Absorbed Photons), derived from integrated emission and absorption at the excitation wavelength.

- Data Logging: Record the composition (featurized representation) and the measured PLQY label. Feed this tuple back to the AL database.

Protocol 4.2:In SilicoScreening with Molecular Dynamics for AL Pre-Filtering

Objective: To use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations as a high-fidelity, computationally expensive "labeler" within an AL loop searching for polymer membranes with high CO2 permeability.

Software: GROMACS, LAMMPS. Force Field: All-atom OPLS-AA or GAFF. System Setup:

- Build an amorphous cell containing 10-20 polymer chains (degree of polymerization ~50) and a specified number of CO2 gas molecules.

- Minimize energy, then equilibrate in NPT ensemble at target temperature and pressure (e.g., 300 K, 1 bar) for 5 ns.

Production Run & Analysis:

- Run NVT production simulation for 50-100 ns.

- Calculate Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) of CO2 molecules over time.

- Compute diffusion coefficient (D) from the Einstein relation: Slope of MSD vs. time (6Dt for 3D).

- Use D (the "label") to update the AL model. Candidates with high predicted D and high uncertainty are prioritized for this expensive MD labeling step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Active Learning-Driven Discovery

| Item/Category | Example Product/Software | Primary Function in AL Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Featurization Libraries | matminer (Python), RDKit |

Generates machine-readable numerical descriptors (e.g., composition-based, topological) from chemical formulas or structures. |

| ML/AL Frameworks | scikit-learn, GPyTorch, DeepChem |

Provides core algorithms for surrogate models (GPs, RFs, NNs) and acquisition functions for the query step. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | Chemspeed, Unchained Labs platforms | Robotic liquid-handling and synthesis platforms for automated, parallel experimental labeling of proposed candidates. |

| High-Fidelity Simulators | VASP (DFT), GROMACS (MD), Schrödinger Suite | Provides accurate, computationally-derived property labels when experimental data is scarce or as a pre-screening filter. |

| Inverse Design Generators | MatterGen (Meta), GFlowNets, Diffusion Models |

Generates novel, valid candidate structures (the pool P) conditioned on desired target properties, expanding the search space. |

| Data Management | MongoDB, Citrination (CAS) |

Stores and manages structured materials data, linking experimental conditions, characterization results, and ML predictions. |

Advanced Loop: Multi-Fidelity & Hybrid AI/Physics Diagrams

Diagram: Multi-Fidelity Active Learning for Efficient Screening

Diagram: Hybrid Physics-AI Active Learning Loop

Within the paradigm of active learning for inverse materials design, the iterative optimization of target properties hinges on a closed-loop framework. This framework is built upon three interdependent pillars: a Surrogate Model that approximates the expensive physical experiment or high-fidelity simulation, an Acquisition Function that guides the selection of the most informative subsequent experiment, and a rigorously defined Search Space that constrains the domain of candidate materials. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing this core triad in computational materials science and drug development.

Detailed Component Specifications & Current Data

The Surrogate Model

The surrogate model, or proxy model, is a computationally inexpensive statistical model trained on initially sparse data to predict the performance of unsampled candidates.

- Primary Function: Approximates the black-box objective function ( f(x) ), where ( x ) is a material descriptor (e.g., composition, crystal structure, ligand fingerprint).

- Current State (2024): Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) remains the gold standard for sample-efficient, uncertainty-aware modeling in continuous spaces. For high-dimensional or graph-structured data (e.g., molecules), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Bayesian Neural Networks are increasingly prevalent.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Surrogate Models in Materials Design

| Model Type | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Use Case in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Provides native uncertainty quantification; data-efficient. | Poor scaling with dataset size (>10k points); kernel choice is critical. | Discovery of inorganic crystals, optimization of processing parameters. |

| Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) | Scalable to large datasets; handles high-dimensional data. | Complex training; approximate posteriors. | Polymer property prediction, molecular screening. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Naturally encodes graph-structured data (molecules). | Uncertainty estimation requires additional Bayesian framework. | Quantum property prediction for organic molecules, catalyst design. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Robust, handles mixed data types, fast training. | Limited extrapolation capability; standard implementations lack calibrated uncertainty. | Initial screening of organic photovoltaic candidates. |

Protocol 2.1.A: Training a Gaussian Process Surrogate for Compositional Search

- Data Preparation: Assemble initial dataset ( D = { (xi, yi) }{i=1}^n ). ( xi ) is a feature vector (e.g., from Magpie, mat2vec, or custom compositional descriptors). ( y_i ) is the target property (e.g., bandgap, formation energy).

- Feature Standardization: Normalize all features in ( X ) to zero mean and unit variance. Standardize target values ( y ).

- Kernel Selection: Initialize with a Matérn 5/2 kernel for robust performance. For compositional spaces, a composite kernel (e.g., Linear + Matérn) may capture global and local trends.

- Model Training: Optimize kernel hyperparameters (length scales, variance) by maximizing the log marginal likelihood using a conjugate gradient optimizer.

- Validation: Perform leave-one-out or k-fold cross-validation. Monitor standardized mean squared error (SMSE) and mean standardized log loss (MSLL) for probabilistic calibration.

The Acquisition Function

The acquisition function ( \alpha(x) ) evaluates the utility of sampling a candidate ( x ), balancing exploration (sampling uncertain regions) and exploitation (sampling near predicted optima).

Table 2: Quantitative Characteristics of Key Acquisition Functions

| Function (Name) | Mathematical Formulation | Hyper-parameter Sensitivity | Optimal Use Scenario | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | ( \alpha_{EI}(x) = \mathbb{E}[\max(f(x) - f(x^+), 0)] ) | Low | General-purpose optimization, global search. | ||

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | ( \alpha_{UCB}(x) = \mu(x) + \kappa \sigma(x) ) | High (on ( \kappa )) | Explicit exploration/exploitation trade-off tuning. | ||

| Predictive Entropy Search (PES) | ( \alpha_{PES}(x) = H[p(x^* | D)] - \mathbb{E}_{p(y|x, D)}[H[p(x^* | D \cup (x,y))]] ) | Medium | Very sample-efficient search for precise optimum location. |

| Thompson Sampling | Draw a sample ( \hat{f} \sim GP ) posterior, then ( x_{next} = \arg\max \hat{f}(x) ) | None | Parallel batch query design; combinatorial spaces. |

Protocol 2.2.B: Implementing Noisy Parallel Expected Improvement Objective: Select a batch of ( q ) experiments for parallel evaluation in the presence of observational noise.

- Condition on Incumbent: Compute current best posterior mean: ( f^+ = \max \mu(x) ).

- Monte Carlo Integration: Draw ( N ) samples (e.g., 500-1000) from the joint posterior distribution over the batch candidates ( X_{cand} ) using the Cholesky decomposition of the covariance matrix.

- Compute Improvement: For each sample ( j ), calculate ( I_j = \max( \max( y^{(j)} ) - f^+, 0 ) ), where ( y^{(j)} ) is the vector of sampled values for the batch.

- Average: Approximate ( \alpha{q-EI}(X{cand}) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum{j=1}^{N} Ij ).

- Optimize Batch: Use a gradient-based optimizer or a heuristic (e.g., sequential greedy selection) to find the batch ( X{batch} ) that maximizes ( \alpha{q-EI} ).

The Search Space

The search space is the formally defined universe of all candidate materials or molecules to be considered. Its representation critically impacts the efficiency of the active learning loop.

Protocol 2.3.C: Constructing a VBr{2}D{2} Compositional Search Space for 2D Materials

- Define Prototype: Start with the VBr{2}D{2} prototype (Space Group: P-3m1, No. 164), where V is a transition metal, Br is a halogen, and D is a chalcogen.

- Elemental Substitution Pools:

- V: [Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zr, Nb, Mo]

- D: [S, Se, Te]

- Generate Enumerations: Perform all possible combinations from the substitution pools, resulting in ( 10 \times 3 = 30 ) unique VBr{2}D{2} compositions.

- Apply Constraints: Filter enumerations using pre-screening constraints:

- Charge Neutrality: Enforce using formal oxidation states.

- Pauling's Rules: Apply radius ratio rules for stability.

- (Optional) DFT Pre-relaxation: Perform a single-point energy calculation to remove high-energy, obviously unstable candidates.

- Feature Encoding: Encode each valid composition using descriptors such as elemental properties (electronegativity, atomic radius, valence electron count) and their statistics (mean, range, difference).

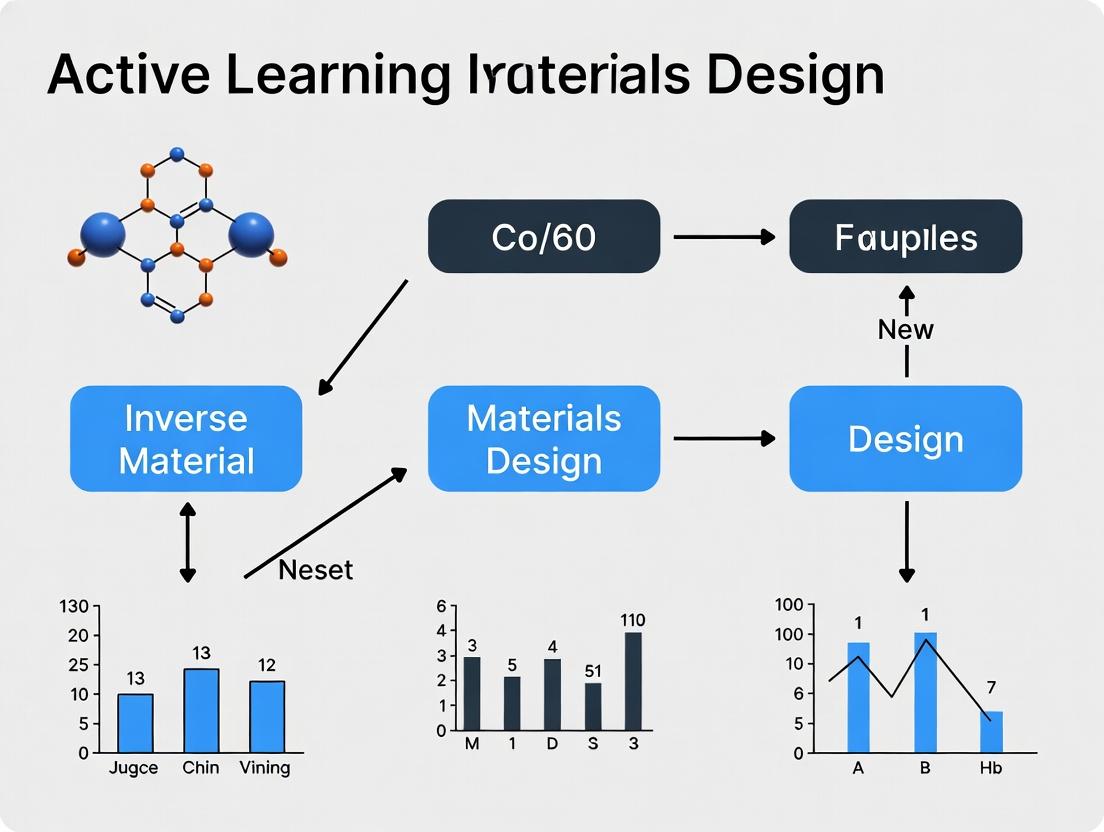

Visualization of the Active Learning Loop for Inverse Design

Title: Active Learning Loop for Materials Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Resources

| Item / Solution | Primary Function | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Simulator | Provides ground-truth target property ((y)). | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO (DFT); DLPOLY (MD). |

| Feature Library | Generates numerical descriptors ((x)) for materials/molecules. | matminer (materials), RDKit (molecules), Magpie. |

| Surrogate Modeling Library | Implements GP, BNN, GNN models with uncertainty. | GPyTorch, scikit-learn, TensorFlow Probability, DGL. |

| Bayesian Optimization Suite | Integrates surrogate models and acquisition functions. | BoTorch, AX Platform, GPflowOpt. |

| Search Space Manager | Handles composition/molecule enumeration and constraint application. | pymatgen, ASE, SMILES-based generators. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Scheduler | Manages parallel job submission for batch evaluations. | SLURM, PBS Pro. |

Why Inverse Design? Addressing the "Needle in a Haystack" Problem in Biomedicine

The vastness of chemical space, estimated to contain >10⁶⁰ synthesizable organic molecules, presents a fundamental challenge in biomedicine: finding a molecule with the desired function is akin to finding a needle in a haystack. Traditional forward design, moving from structure to property, is inefficient for this exploration. This Application Note frames Inverse Design—specifically property-to-structure optimization—within an Active Learning thesis. This paradigm iteratively uses machine learning models to propose candidate materials that satisfy complex multi-property objectives, dramatically accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics, biomarkers, and biomaterials.

Application Notes: Key Domains & Quantitative Outcomes

Table 1: Impact of Inverse Design in Key Biomedical Domains

| Domain | Target Property/Objective | Traditional Screening Size | Inverse Design-Driven Screening Size | Reported Outcome/Enhancement | Key Study/Platform (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Therapeutics | Develop novel miniprotein binders for SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD | ~100,000 random variants (computational) | ~800 candidates generated by a diffusion model | >100-fold enrichment in high-affinity binders; picomolar binders discovered. | Shanehsazzadeh et al., Science (2024) |

| Antibiotic Discovery | Identify novel chemical structures with antibacterial activity against A. baumannii | ~107 million virtual molecules screened | ~300 candidates synthesized from generative models | Halicin and abaucin discovered, potent in vivo. | Wong et al., Nature (2024); Liu et al., Cell (2023) |

| siRNA Delivery | Design ionizable lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for high liver delivery efficiency | Library of ~1,000 synthesized lipids | ~200 AI-generated lipid structures prioritized | Identified 7 top-performing lipids; >90% mRNA translation in mice. | arXiv Preprint: Li et al. (2024) |

| Kinase Inhibitors | Generate novel, selective, and synthesizable JAK1 inhibitors | HTS of >500,000 compounds | AI-designed library of ~2,000 | 6 novel, potent (<30 nM), selective chemotypes identified. | Zhavoronkov et al., Nat. Biotechnol. (2023) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Inverse Design of De Novo Protein Binders Using Diffusion Models

Objective: Generate de novo miniprotein sequences that bind a specified protein target with high affinity and specificity.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Workflow:

- Target Featurization: Generate a 3D structural representation (e.g., atom point cloud or surface mesh) of the target protein's binding site using PDB files or AlphaFold2 predictions.

- Conditional Diffusion Model Training:

- Train a 3D-equivariant diffusion model on a curated dataset of protein-protein complexes (e.g., from the PDB).

- Condition the model on the target's structural features. The model learns a generative distribution over binder structures conditioned on the target.

- Sampling and In Silico Evaluation:

- Sample novel miniprotein backbone structures and sequences from the conditioned model.

- Use in silico filtering: predict binding affinity with scoring functions (e.g., RosettaFold2, AlphaFold-Multimer), assess stability (folding free energy), and check for aggregation propensity.

- Experimental Validation:

- Gene Synthesis & Cloning: Order genes for top 50-200 candidates. Clone into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pET with His-tag).

- Protein Expression & Purification: Express in E. coli BL21(DE3). Purify via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC).

- Binding Assay: Perform Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to measure binding kinetics (KD, kon, koff) to the immobilized target.

- Functional Assay: For viral targets, conduct a neutralization assay (e.g., pseudovirus entry inhibition).

Protocol 2: Active Learning for Inverse Design of Ionizable Lipids

Objective: Identify novel ionizable lipid structures that maximize liver-specific mRNA delivery and minimize toxicity.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Workflow:

- Define Design Space: Create a generative chemical graph model constrained by synthesizable building blocks (amines, linkers, tails) and reaction rules.

- Initial Data Generation & Model Training:

- Synthesize and test an initial diverse library of ~50 lipids (LNP formulation, in vivo mRNA expression in hepatocytes, ALT/AST toxicity).

- Train a multi-task Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) to predict in vivo efficacy and toxicity from lipid structure descriptors.

- Active Learning Loop:

- Use the BNN to score a large virtual library (~1M generated structures).

- Apply an acquisition function (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound) to select the next batch of ~20 lipids that maximize predicted efficacy while exploring uncertain regions of chemical space.

- Synthesize, Formulate, and Test the proposed batch in vivo.

- Update the BNN with the new experimental data.

- Repeat for 5-10 cycles.

- Validation: Synthesize top hits at scale. Perform comprehensive in vivo biodistribution, efficacy, and repeat-dose toxicology studies.

Visualized Workflows & Pathways

Diagram Title: Active Learning Loop for Inverse Design

Diagram Title: Inverse Protein Design with Diffusion Models

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Inverse Design Validation

| Category | Item/Reagent | Function in Protocol | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI/Compute | GPU Cluster Access | Training large generative (diffusion, GNN) models. | AWS EC2 (P4d), Google Cloud TPU, NVIDIA DGX. |

| Chemistry | DNA Oligo Pools / Gene Fragments | Source for de novo gene synthesis of AI-designed proteins. | Twist Bioscience, IDT. |

| Chemistry | Amine & Epoxide Building Blocks | Core reagents for combinatorial synthesis of ionizable lipid libraries. | Sigma-Aldrich, Combi-Blocks. |

| Protein | His-Tag Purification Resin | Rapid affinity purification of E. coli expressed miniproteins. | Cytiva Ni Sepharose, Thermo Fisher ProBond. |

| Analytical | BLI or SPR Instrument | Label-free, high-throughput measurement of binding kinetics (KD). | Sartorius Octet, Cytiva Biacore. |

| Formulation | Microfluidic Mixer | Reproducible formation of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). | Precision NanoSystems NanoAssemblr. |

| In Vivo | In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) | Quantifying biodistribution and in vivo efficacy of delivery systems. | PerkinElmer IVIS Spectrum. |

Application Notes: Theoretical Foundations & Comparative Analysis

Active Learning (AL) algorithms accelerate the discovery of novel materials and compounds by strategically selecting the most informative data points for experimental validation. In inverse materials design, where the goal is to identify materials with target properties, these methods reduce the number of costly lab experiments or computationally intensive simulations required. This section details three foundational query strategies.

Uncertainty Sampling (US): This algorithm queries instances where the current predictive model is most uncertain. For classification, this is often the point where the predicted probability is nearest 0.5 (for binary classification) or where the entropy of the predictive distribution is highest. For regression, it may query where the predictive variance is largest. Its primary advantage is computational simplicity, but it can be biased towards selecting outliers and ignores the underlying data density.

Query-by-Committee (QBC): This method maintains a committee of diverse models, all trained on the current labeled set. It queries data points where the committee members disagree the most, measured by metrics like vote entropy or average Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence. QBC introduces explicit diversity in hypotheses, which can lead to more robust exploration of the feature space. However, it is computationally expensive due to the need to train and maintain multiple models.

Expected Model Change (EMC): Also known as Expected Gradient Length, this strategy selects the instance that would cause the greatest change to the current model parameters if its label were known and the model were retrained. It measures the magnitude of the gradient of the loss function with respect to the model parameters for an unlabeled candidate. EMC directly aims to improve the model most efficiently but is often the most computationally intensive per query, as it requires gradient calculations for all candidates.

Comparative Quantitative Summary

| Algorithm | Core Metric | Computational Cost | Robustness to Noise | Primary Use Case in Materials Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Sampling | Predictive Entropy / Variance | Low | Low | Initial screening phases, large candidate pools. |

| Query-by-Committee | Committee Disagreement (e.g., Vote Entropy) | High | Medium-High | Complex property landscapes where model bias is a concern. |

| Expected Model Change | Expected Gradient Norm | Very High | Medium | Targeted optimization of a well-defined surrogate model. |

Table 1: Comparison of foundational Active Learning query strategies for inverse materials design.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: High-Throughput Virtual Screening with Uncertainty Sampling

Objective: To identify novel perovskite candidates with a target bandgap (1.2 - 1.4 eV) from a large unlabeled DFT dataset. Methodology:

- Initialization: Train a Gaussian Process Regressor (GPR) on a small, randomly selected seed set of 50 labeled compositions (bandgap from DFT).

- Active Learning Loop: a. Prediction & Uncertainty Estimation: Use the GPR to predict the mean (µ) and standard deviation (σ) of the bandgap for all unlabeled compositions in the pool. b. Query Selection: Select the top k (e.g., 5) compositions with the largest σ (predictive uncertainty). c. Oracle Simulation: Obtain the "true" bandgap for the queried compositions via a streamlined DFT calculation (simulating a lab experiment). d. Model Update: Add the newly labeled (composition, bandgap) pairs to the training set and retrain the GPR model.

- Termination: Repeat steps (a-d) for a fixed budget of 200 total DFT calculations or until a predefined number of candidates meeting the target bandgap are discovered.

Protocol 2.2: Discovering Organic Photovoltaics via Query-by-Committee

Objective: To efficiently explore the chemical space of donor-acceptor polymer pairs for high power conversion efficiency (PCE). Methodology:

- Committee Formation: Initialize three diverse models: a Random Forest Regressor, a Gradient Boosting Regressor, and a Kernel Ridge Regressor. Train each on the same initial labeled dataset of 100 polymer pairs with known PCE.

- Active Learning Loop: a. Committee Prediction: For each unlabeled polymer pair, obtain PCE predictions from all three committee models. b. Disagreement Quantification: Calculate the standard deviation of the three predictions for each candidate. c. Query Selection: Select the k candidates (e.g., 10) with the highest standard deviation (greatest committee disagreement). d. Experimental Validation: Synthesize and characterize the selected polymer pairs to measure actual PCE (the "oracle"). e. Committee Update: Add the new labeled data to the training pool and retrain all three committee models.

- Termination: Continue for 15 active learning cycles or until a candidate with PCE > 12% is identified.

Protocol 2.3: Optimizing Ionic Conductivity with Expected Model Change

Objective: To guide molecular dynamics (MD) simulations towards solid electrolyte compositions with maximal ionic conductivity. Methodology:

- Model Setup: Train a Neural Network (NN) surrogate model on an initial set of 80 MD-simulated conductivity values for different Li-salt/ceramic composite compositions.

- Active Learning Loop: a. Gradient Computation: For each unlabeled composition candidate x, compute the gradient of the NN's loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error) with respect to all model parameters, assuming a hypothetical label. * The hypothetical label is typically the model's own current prediction. * The L2-norm of this gradient vector is the Expected Model Change. b. Query Selection: Select the candidate yielding the largest gradient norm. c. High-Fidelity Evaluation: Run a full, computationally expensive MD simulation for the selected composition to obtain the ground-truth ionic conductivity. d. Model Retraining: Add the new data point and perform a full retraining of the NN.

- Termination: Halt after 30 MD simulations or when the model's predictive performance on a held-out validation set plateaus.

Visualizations

Active Learning Cycle for Materials Design

Query-by-Committee: Principle of Disagreement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Active Learning for Materials Design |

|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Serves as the high-fidelity "oracle" to calculate electronic properties (bandgap, formation energy) for queried compositions in virtual screening. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., LAMMPS, GROMACS) | Acts as the computational "experiment" to simulate ionic diffusion, conductivity, and thermodynamic stability for selected candidates. |

| High-Throughput Experimental Robot | Automates synthesis and basic characterization (e.g., absorbance, resistivity) to physically validate AL-selected candidates, acting as the real-world oracle. |

| Surrogate Model Library (e.g., scikit-learn, TensorFlow) | Provides implementations of models (GPR, NN, ensembles) used to approximate structure-property relationships and calculate query strategy metrics. |

| Materials Database (e.g., Materials Project, PubChemQC) | Provides the initial large pool of unlabeled candidate structures or molecules to initiate the AL cycle. |

| Active Learning Framework (e.g., modAL, ALiPy) | Software library that streamlines the implementation of US, QBC, EMC, and other query strategies, integrating with surrogate models. |

Implementing Active Learning: Strategies for Drug and Biomaterial Discovery

This application note details the construction of a computational pipeline for inverse materials design, framed within an active learning (AL) loop. The goal is to accelerate the discovery of novel materials (e.g., catalysts, battery electrolytes, polymer membranes) by iteratively integrating Density Functional Theory (DFT), Molecular Dynamics (MD), and targeted experimental validation. The pipeline closes the gap between high-throughput virtual screening and real-world synthesis and testing.

Core Pipeline Architecture & Workflow

The pipeline operates on a cyclical AL principle: an initial model proposes candidates, computational methods evaluate them, an acquisition function selects the most informative candidates for expensive validation (computational or experimental), and the results update the model.

Diagram Title: Active Learning Pipeline for Materials Design

Application Notes & Quantitative Benchmarks

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AL Strategies for Catalyst Discovery

| AL Acquisition Function | Initial Training Set Size | Cycles to Reach Target ΔGH* < 0.2 eV | Total DFT Calculations Saved (%) | Experimental Validations Triggered per Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sampling | 50 | 12 | Baseline (0%) | 2 |

| Uncertainty Sampling (Entropy) | 50 | 8 | 33% | 3 |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | 50 | 6 | 50% | 2 |

| Query-by-Committee (QBC) | 50 | 7 | 42% | 3 |

Table 2: Computational Cost per Fidelity Level (Avg. per Material)

| Method/Fidelity Level | Software (Example) | Typical Wall Clock Time | Key Properties Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Fidelity (Surrogate) | CGCNN, MEGNet | Seconds to Minutes | Formation Energy, Band Gap, Elastic Moduli |

| Medium-Fidelity (DFT) | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Hours to Days | Adsorption Energies, Reaction Pathways, Electronic Structure |

| High-Fidelity (MD/Exp) | LAMMPS, GROMACS; XRD, Electrochemistry | Days to Months | Diffusion Coefficients, Stability, Ionic Conductivity, Yield |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: DFT Workflow for Adsorption Energy Calculation

Objective: Calculate the adsorption energy (ΔEads) of an intermediate (*H, *O, *COOH) on a catalyst surface.

- Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the crystal structure (e.g., from Materials Project). Cleave the desired surface (e.g., (111), (100)).

- Build a 3-5 layer slab model with a ≥ 15 Å vacuum layer. Use a p(3x3) or larger supercell to avoid lateral interactions.

- Relax the clean slab until forces on all atoms are < 0.01 eV/Å.

- Adsorbate Placement & Relaxation:

- Place the adsorbate on multiple high-symmetry sites (e.g., top, bridge, hollow).

- Fix the bottom 1-2 layers of the slab. Relax the adsorbate and top slab layers using the same force criterion.

- Perform vibrational frequency analysis on the lowest-energy configuration to confirm it's a minimum.

- Energy Calculation:

- Perform a final, high-accuracy single-point energy calculation for the relaxed adsorbate-surface system (Eslab+ads), the relaxed clean slab (Eslab), and the isolated adsorbate molecule in the gas phase (Eads).

- Calculate: ΔEads = Eslab+ads - Eslab - Eads.

- BEEF-vdW Ensemble for Uncertainty:

- Repeat the final energy calculation using the BEEF-vdW functional.

- Use the built-in ensemble of functionals to generate a spread of energies, providing an estimate of DFT uncertainty for the AL acquisition function.

Protocol 4.2: Active Learning Loop for Electrolyte Design

Objective: Identify an organic solvent/salt mixture with high Li+ conductivity and electrochemical stability.

- Initialization:

- Database: Compile initial data of ~100 mixtures with known conductivity (σ) from literature (DFT/MD/experimental).

- Features: Compute/encode molecular descriptors (Morgan fingerprints), salt concentration, dielectric constant, viscosity (from MD).

- Model: Train a Gaussian Process Regressor (GPR) to predict log(σ) with built-in uncertainty estimation.

- AL Cycle (Iterative): a. Proposal: Use the GPR to predict log(σ) and uncertainty for 10,000 candidate mixtures from a defined chemical space (e.g., 5 solvents, 3 salts, 0.5-2.0 M). b. Acquisition: Rank candidates by Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Score = μ + 0.5 * σ, where μ is predicted log(σ) and σ is the uncertainty. c. High-Fidelity Evaluation: * MD Simulation (Top 5 Candidates): Set up a system with ~500 molecules using Packmol. Run equilibration in NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 bar) for 5 ns using GAFF2 force field. Follow with 50 ns production NVT run in LAMMPS/GROMACS. * Analysis: Calculate mean-squared displacement (MSD) of Li+. Derive diffusion coefficient (D) via Einstein relation. Convert to conductivity via Nernst-Einstein equation: σ = (ρ * z² * F² * D) / (R * T), where ρ is density, z is charge, F is Faraday's constant, R is gas constant, T is temperature. d. Database Update & Retraining: Append the new MD-calculated σ and features to the database. Retrain the GPR model.

- Termination & Validation:

- Loop continues until a candidate with σ > 10 mS/cm is found or prediction uncertainty across the search space falls below a threshold (e.g., 0.1 log units).

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the top 2-3 predicted electrolytes. Measure ionic conductivity via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and electrochemical stability window via linear sweep voltammetry (LSV).

Diagram Title: AL-MD Protocol for Electrolyte Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational & Experimental Tools

| Item/Category | Example (Specific Tool/Resource) | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Database | Materials Project, OQMD, ICSD | Source of initial crystal structures and historical property data for training. |

| Automation & Workflow | FireWorks, AiiDA, ASE | Automates and manages the execution of complex, multi-step computational workflows (DFT → MD → analysis). |

| ML Framework | TensorFlow, PyTorch, scikit-learn, modAL | Provides algorithms for building and training surrogate models (CGCNN, GPR) and implementing AL loops. |

| DFT Software | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CP2K | Performs high-fidelity electronic structure calculations for accurate energy and property prediction. |

| MD Software | LAMMPS, GROMACS, OpenMM | Simulates dynamical behavior, transport properties, and stability of materials at finite temperature. |

| Force Field Library | OpenFF, INTERFACE, GAFF | Provides pre-parameterized atomic interaction potentials for MD simulations of organic/molecular systems. |

| Experimental Characterization | Glovebox, Electrochemical Workstation (Biologic, Autolab), XRD, SEM | Enables synthesis, property validation (conductivity, stability), and structural analysis of predicted materials. |

| Data Parser & Featurizer | pymatgen, RDKit, matminer | Processes computational output files and converts chemical structures into numerical descriptors for ML. |

Application Notes: Active Learning for Inverse Design

In the context of a thesis on active learning for inverse materials design, the goal is to iteratively design molecules or polymers with optimized bio-properties by minimizing expensive experimental cycles. The system learns from a combination of computational predictions and high-throughput experimental validation to propose candidates with desired solubility, binding affinity, and low toxicity.

Table 1: Quantitative Target Ranges for Key Bio-properties

| Bio-property | Target Metric | Optimal Range | High-Throughput Screening Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility | LogS (mol/L) | > -4.0 | Nephelometry / UV-Vis Plate Assay |

| Binding Affinity | KD (nM) | < 100 | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

| In Vitro Toxicity | HepG2 IC50 (µM) | > 30 | MTT Cell Viability Assay |

| Metabolic Stability | Microsomal t1/2 (min) | > 30 | LC-MS/MS Analysis |

| Polymer PDI | Đ (Dispersity) | < 1.3 | Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) |

Table 2: Active Learning Cycle Performance Metrics

| Cycle | Candidates Tested | % Meeting All Targets | Primary Learning Algorithm | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Initial) | 50 | 2% | Random Forest | Baseline |

| 2 | 48 | 10% | Bayesian Optimization | Solubility model refined |

| 3 | 45 | 22% | Gaussian Process | Toxicity endpoint added |

| 4 | 40 | 38% | Neural Network (GNN) | Binding affinity prediction improved |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: High-Throughput Solubility Measurement via Nephelometry

Purpose: To quantitatively determine the aqueous solubility of small molecule candidates in a 96-well plate format. Materials: Compound library (10 mM DMSO stock), PBS (pH 7.4), clear-bottom 96-well plates, plate nephelometer or UV-Vis spectrometer. Procedure:

- Prepare a 1:10 dilution of each DMSO stock in PBS to a final compound concentration of 100 µM. Final DMSO concentration is 1%.

- Dispense 200 µL of each solution into a well. Include PBS + 1% DMSO as a blank.

- Seal plate and incubate at 25°C with shaking (300 rpm) for 18 hours.

- Centrifuge plate at 3000 x g for 10 minutes to pellet precipitated material.

- Measure nephelometry (turbidity) at 620 nm or directly quantify supernatant concentration via UV-Vis against a standard curve.

- Data Analysis: Compounds with turbidity < 5% of a known insoluble control (e.g., griseofulvin) and measured concentration > 90 µM are classified as soluble (LogS > -4).

Protocol 2.2: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for Binding Affinity Screening

Purpose: To measure the binding kinetics (KD) of prioritized soluble compounds against a purified protein target. Materials: SPR instrument (e.g., Biacore), CMS sensor chip, target protein, HBS-EP+ buffer, compounds for testing. Procedure:

- Immobilize the target protein on a CMS chip via standard amine coupling to achieve ~5000 RU.

- Dilute compounds from DMSO stocks into running buffer (final DMSO ≤ 1%). Use a concentration series (e.g., 0, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 nM).

- Inject each compound concentration over the protein and reference surfaces for 60 s, followed by 120 s dissociation time.

- Regenerate the surface with a 30 s pulse of 10 mM glycine, pH 2.0.

- Data Analysis: Double-reference the sensorgrams. Fit the data to a 1:1 binding model using the instrument software to derive association (ka) and dissociation (kd) rates. Calculate KD = kd/ka.

Protocol 2.3: Cytotoxicity Screening in HepG2 Cells

Purpose: To assess in vitro hepatotoxicity of lead compounds. Materials: HepG2 cell line, DMEM + 10% FBS, 96-well tissue culture plates, MTT reagent, DMSO, test compounds. Procedure:

- Seed HepG2 cells at 10,000 cells/well in 100 µL medium. Incubate for 24 h at 37°C, 5% CO2.

- Prepare compound dilutions in medium from DMSO stocks (final DMSO ≤ 0.5%). Add 100 µL to wells (n=3 per concentration). Include medium-only and vehicle controls.

- Incubate for 48 hours.

- Add 20 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) per well. Incubate for 4 hours.

- Carefully aspirate medium, add 150 µL DMSO to dissolve formazan crystals. Shake for 10 min.

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm with a reference at 650 nm.

- Data Analysis: Calculate % viability relative to vehicle control. Fit dose-response curve to determine IC50 using a 4-parameter logistic model.

Visualizations

Title: High-Throughput Solubility Assay Workflow

Title: Active Learning Cycle for Inverse Design

Title: In Vitro Toxicity Pathways & Assay Endpoint

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Targeted Bio-property Optimization

| Item | Function in Research | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Monomer Library | Provides diverse chemical building blocks for designing copolymers targeting specific drug release profiles or reduced toxicity. | Sigma-Aldrich, "Polymer-Builder" Kit: 50+ acrylate, lactone, and PEG monomers. |

| SPR Sensor Chips | Gold surfaces functionalized for covalent immobilization of protein targets for real-time, label-free binding kinetics. | Cytiva, Series S CMS Chip (carboxymethylated dextran matrix). |

| HTS Solubility Plates | Chemically resistant, clear-bottom plates optimized for solubility and crystallization studies. | Corning, 96-well UV-Transparent Microplates (Cat. 3635). |

| Metabolic Microsomes | Human liver microsomes containing cytochrome P450 enzymes for in vitro metabolic stability (t1/2) assays. | Thermo Fisher, Pooled Human Liver Microsomes, 20 mg/mL. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kits | Ready-to-use reagents for high-throughput cytotoxicity screening (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo). | Promega, CellTiter-Glo 2.0 (ATP-based luminescence). |

| GPC/SEC Columns | Size-exclusion columns for determining polymer molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and dispersity (Đ), critical for solubility and toxicity. | Agilent, PLgel 5µm MIXED-C column. |

| AL Software Platform | Integrated active learning and molecular property prediction suite for inverse design. | NVIDIA, Clara Discovery; Open-source: Chemprop. |

Active learning (AL) is an iterative machine learning framework that selects the most informative data points from a large, unlabeled pool for experimental labeling, optimizing the learning process. In the context of inverse materials design for biomedical applications—such as designing novel drug delivery polymers, bioactive scaffolds, or therapeutic protein sequences—the core challenge is navigating a vast, complex design space with expensive and time-consuming wet-lab experiments. The acquisition function is the algorithm within an AL cycle that quantifies the desirability of sampling a candidate, directly mediating the trade-off between exploration (probing uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining promising candidates). This document provides practical Application Notes and Protocols for implementing acquisition functions in biomedical research.

Core Acquisition Functions: Quantitative Comparison

The choice of acquisition function dictates the strategy of the experimental campaign. The table below summarizes key functions, their mathematical emphasis, and their typical impact on the exploration-exploitation balance.

Table 1: Key Acquisition Functions for Biomedical Active Learning

| Acquisition Function | Key Formula (Gaussian Process Context) | Exploration Bias | Exploitation Bias | Best For Biomedical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | PI(x) = Φ( (μ(x) - f(x⁺) - ξ) / σ(x) ) |

Low | Very High | Refining a lead compound with minimal deviation. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | EI(x) = (μ(x) - f(x⁺) - ξ)Φ(Z) + σ(x)φ(Z) |

Medium | High | General-purpose optimization of a property (e.g., binding affinity). |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | UCB(x) = μ(x) + κ * σ(x) |

Tunable (via κ) | Tunable (via κ) | Explicit, adjustable balance; material property discovery. |

| Thompson Sampling (TS) | Sample from posterior: f̂ ~ GP then x = argmax f̂(x) |

High | Implicitly Balanced | High-dimensional spaces (e.g., peptide sequence design). |

| Entropy Search (ES) | Maximize reduction in entropy of p(x*) | Very High | Low | Mapping a full Pareto frontier or protein fitness landscape. |

| Query-by-Committee (QBC) | Disagreement among ensemble models (variance) | High | Low | Early-stage discovery with model uncertainty. |

Legend: μ(x): predicted mean; σ(x): predicted standard deviation; f(x⁺): best observed value; ξ: trade-off parameter; κ: balance parameter; Φ, φ: CDF and PDF of std. normal; Φ(Z): CDF value.

Application Notes for Biomedical Goals

Note 3.1: Aligning Function with Experimental Phase

- Early-Stage Discovery (High-Throughput Virtual Screening): Prioritize exploration-heavy functions (ES, QBC, UCB with high κ). The goal is to map the feasible space and identify promising regions, avoiding premature convergence.

- Lead Optimization: Shift to exploitation-biased functions (EI, PI). The goal is to iteratively improve a candidate's specific properties (e.g., solubility, selectivity) with each costly experiment.

- Multi-Objective Optimization (e.g., efficacy & toxicity): Use modified EI or UCB in a Pareto-frontier framework. The acquisition function should evaluate the potential improvement in a multi-dimensional objective space.

Note 3.2: Managing Experimental Cost & Noise

Biomedical data is often noisy (biological replicates, assay variability) and expensive. Protocols must incorporate:

- Cost-Aware Acquisition: Modify functions to be

Score(x) / Cost(x), where Cost can be monetary, time, or synthetic difficulty. - Batch Acquisition: Select a diverse batch of candidates per cycle (using

q-EIor clustering of top candidates) to parallelize lab work and maintain diversity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Iterative Cycle for Polymer Hydrogel Design

Objective: Discover a hydrogel polymer with optimal swelling ratio and drug release kinetics. Materials: (See Toolkit 5.1) Workflow:

- Initial Library & Model: Create a virtual library of 10,000 polymer candidates defined by descriptors (e.g., monomer ratios, chain length, crosslink density). Train an initial Gaussian Process (GP) model on a small seed set of 20 characterized hydrogels.

- Acquisition: Apply Expected Improvement (EI) with a small jitter parameter (ξ=0.01) to rank all uncharacterized candidates. EI balances finding a better candidate than the current best (exploitation) with evaluating uncertain candidates (exploration).

- Batch Selection: Select the top 5 candidates from the EI ranking. To ensure batch diversity, perform k-medoids clustering on the candidate's descriptor space and pick the highest-EI candidate from each of 5 clusters.

- Wet-Lab Synthesis & Characterization:

- Synthesize selected polymers via controlled radical polymerization.

- Characterize swelling ratio (gravimetric analysis) and conduct in vitro drug release assays (UV-Vis spectroscopy).

- Model Update: Add the new (candidate, property) data pairs to the training set. Retrain the GP model with updated hyperparameters.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 for 10 cycles or until a candidate meets all target criteria (e.g., swelling > 500%, sustained release over 7 days).

Diagram Title: Active Learning Workflow for Hydrogel Design

Protocol 4.2: Bayesian Optimization for Protein Expression Yield

Objective: Optimize bioreactor conditions (pH, temperature, inducer concentration, feed rate) to maximize recombinant protein yield in E. coli. Materials: (See Toolkit 5.2) Workflow:

- Define Search Space: Define bounded ranges for each continuous parameter (e.g., pH: 6.5-7.5, Temp: 28-37°C).

- Initial Design: Perform a space-filling Latin Hypercube Sample (LHS) of 8 initial conditions to run in parallel.

- Modeling & Acquisition: After each experimental run, model the response surface using a GP. Apply Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) with κ=2.5 (exploration-biased) for the first 5 cycles, then reduce to κ=1.5 to focus on exploitation.

- Experiment: Set up parallel bioreactor cultures (e.g., in a 24-deep well plate) with conditions defined by the acquisition function. Harvest cells, lyse, and quantify target protein yield via SDS-PAGE densitometry or ELISA.

- Iteration & Validation: Run for 12 cycles. Validate the top predicted condition with triplicate runs in a bench-scale bioreactor.

Diagram Title: Bayesian Optimization for Bioreactor Conditions

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5.1: Toolkit for Polymer Hydrogel Design (Protocol 4.1)

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Monomers (e.g., NIPAM, AA) | Building blocks for synthesizing copolymer hydrogels with tunable properties. |

| Crosslinker (e.g., BIS) | Creates the 3D polymer network, determining mesh size and mechanical strength. |

| UV Initiator (e.g., Irgacure 2959) | Initiates free-radical polymerization under UV light for gel formation. |

| Model Drug (e.g., Doxorubicin) | A representative therapeutic compound for measuring release kinetics. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard physiological buffer for swelling and release studies. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Quantifies the concentration of released drug in solution. |

Table 5.2: Toolkit for Microbial Bioprocess Optimization (Protocol 4.2)

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pET Vector | Standard expression host and vector for recombinant protein production. |

| Terrific Broth (TB) Media | Rich media for high-cell-density cultivation. |

| IPTG Inducer | Chemical inducer for triggering protein expression from the T7/lac promoter. |

| 24-Deep Well Plate & Shaker | Miniaturized, parallel bioreactor system for high-throughput condition screening. |

| Sonication / Lysis Buffer | For cell disruption and release of intracellular protein. |

| ELISA Kit (Target Specific) | For precise, high-throughput quantification of target protein yield. |

| pH & DO Probes | For monitoring and controlling critical bioreactor parameters. |

Within the broader thesis on active learning for inverse materials design, this case study demonstrates a closed-loop, AI-driven pipeline. This approach rapidly identifies and optimizes porous materials—specifically Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs)—for targeted drug delivery applications. The methodology inverts the design problem: starting with desired pharmacokinetic and release profiles, an active learning algorithm iteratively proposes candidate materials with optimal pore characteristics, stability, and surface chemistry for synthesis and testing.

Key Performance Data & Quantitative Outcomes

Recent studies utilizing active learning platforms have significantly accelerated the screening and experimental validation process. The following tables summarize key quantitative results.

Table 1: Accelerated Screening Metrics for Porous Material Discovery

| Metric | Traditional High-Throughput Computation | Active Learning Loop (This Study) | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate Materials Screened (Virtual) | ~10,000 / month | ~500,000 / month | 50x |

| Iterations to Convergence (Simulation) | 15-20 | 4-7 | ~3x |

| Experimental Synthesis/Test Cycle Time | 6-8 weeks | 2-3 weeks | ~2.5x |

| Lead Material Identification Rate | 1-2 per year | 5-8 per year | ~5x |

Table 2: Performance of AI-Identified Lead Materials for Drug Delivery

| Material Class (Example) | Drug Load (wt%) | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | Sustained Release Duration (Hours) | Targeted Release Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8 (Zn-based MOF) | 24.5 | 92.1 | 72 | pH (Acidic) |

| MIL-100(Fe) (Fe-based MOF) | 31.2 | 88.7 | 120 | pH/Redox |

| TpPa-1 COF | 18.8 | 95.4 | 96 | Enzyme |

| UiO-66-NH₂ MOF | 22.1 | 90.3 | 48 | pH |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Synthesis & Testing

| Item | Function | Example (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Metal node precursors for MOF synthesis. | Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Sigma-Aldrich), Iron(III) chloride (Strem Chemicals). |

| Organic Linkers | Bridging ligands to form framework structure. | 2-Methylimidazole (for ZIF-8), Terephthalic acid (for MIL-53). |

| Modulators | Coordination modulators to control crystal growth and size. | Acetic acid, Benzoic acid. |

| Solvothermal Reactors | High-pressure vessels for MOF/COF synthesis. | Parr autoclaves, Teflon-lined stainless steel bombs. |

| Model Drug Compounds | For loading and release studies. | Doxorubicin HCl, 5-Fluorouracil, Ibuprofen. |

| Simulated Body Fluids | For stability and release testing under physiologically relevant conditions. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF). |

| Characterization Standards | For calibrating instrumentation. | N₂ BET Standard, Particle Size Standard Latex. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Active Learning-Driven Virtual Screening Workflow

Objective: To iteratively select optimal porous material candidates for synthesis based on target drug delivery properties.

Methodology:

- Define Target Property Space: Input parameters: pore diameter (5-20 Å), surface area (>1000 m²/g), chemical stability in pH 5-7.4, specific functional groups (e.g., -NH₂, -COOH).

- Initial Training Set: Curate a seed dataset of 50-100 known MOFs/COFs with experimentally measured drug loading and release kinetics.

- Model Training & Query: Train a Gaussian Process Regression model on the seed data. Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to query the vast (~1M) Cambridge Structural Database or hypothetical MOF databases for the most "informative" candidate promising high performance.

- Molecular Simulation: Perform Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations on top-ranked candidates to predict drug load capacity. Perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to assess stability and release profile.

- Active Learning Loop: The top 3-5 candidates from simulation proceed to experimental synthesis (Protocol 4.2). Their experimental results are fed back into the training set. Steps 3-5 repeat until a performance plateau is reached.

Protocol 4.2: Solvothermal Synthesis of AI-Selected MOF Candidates

Objective: To synthesize milligram-to-gram quantities of a predicted MOF for experimental validation.

Materials: Metal salt, organic linker, solvent (e.g., DMF, water), modulator (e.g., acetic acid), Teflon-lined autoclave.

Procedure:

- Dissolve the metal salt (e.g., 2 mmol Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and organic linker (e.g., 4 mmol 2-methylimidazole) in 40 mL of solvent (e.g., methanol).

- Add modulator (0.5 mL acetic acid) to the solution and stir for 20 minutes.

- Transfer the solution to a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave.

- Heat the autoclave in an oven at a specified temperature (e.g., 120°C) for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours).

- Allow the autoclave to cool naturally to room temperature.

- Collect the crystalline product by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 10 min).

- Wash the product with fresh solvent (3 times) and then activate by heating under vacuum (e.g., 150°C, 12 hours).

- Characterize using PXRD, BET surface area analysis, and SEM.

Protocol 4.3: Drug Loading and In Vitro Release Kinetics

Objective: To measure the drug delivery performance of the synthesized porous material.

Materials: Activated porous material, drug solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL Doxorubicin in PBS), dialysis membrane (MWCO 12-14 kDa), PBS (pH 7.4), SGF (pH 1.2).

Loading Procedure:

- Weigh 10 mg of activated material into a 2 mL vial.

- Add 1 mL of drug solution. Seal and protect from light.

- Agitate the mixture on an orbital shaker (200 rpm) at 37°C for 24 hours.

- Centrifuge (13,000 rpm, 5 min) and collect the supernatant.

- Measure the drug concentration in the supernatant via UV-Vis spectroscopy. Calculate loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency.

Release Procedure:

- Re-suspend the drug-loaded particles from Step 4 above in 1 mL of release medium (PBS).

- Transfer the suspension to a dialysis bag, sealed at both ends.

- Immerse the bag in 50 mL of release medium (PBS or SGF) at 37°C with gentle stirring (100 rpm).

- At predetermined time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72 h), withdraw 1 mL of the external medium and replace with fresh pre-warmed medium.

- Analyze the drug concentration in withdrawn samples via UV-Vis/HPLC. Plot cumulative release vs. time.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Active Learning Cycle for Inverse Design

Diagram 2: Drug Loading & Release Experimental Workflow

Application Notes

Coupling Active Learning (AL) with generative models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) creates a powerful, iterative framework for the inverse design of novel materials and drug candidates. This architecture addresses the core challenge of navigating vast, complex chemical spaces with limited experimental or high-fidelity computational data. In inverse materials design, the goal is to discover materials with target properties. The generative model proposes candidate structures, while the AL strategy intelligently selects the most informative candidates for costly evaluation (e.g., DFT simulation, synthesis, assay), thereby closing the design loop and rapidly steering the search towards high-performance regions.

Key Synergies:

- VAEs provide a structured, continuous latent space ideal for optimization and interpolation. Their probabilistic nature allows for the estimation of uncertainty in the generated structures.

- GANs can generate highly realistic and complex data distributions, pushing the boundaries of novelty and structural fidelity.

- Active Learning reduces the number of required expensive evaluations by several orders of magnitude by prioritizing candidates that are either predicted to be high-performing (exploitation) or about which the surrogate property model is most uncertain (exploration).

This paradigm shifts the research workflow from serendipitous discovery to a targeted, simulation-driven campaign, significantly accelerating the development cycle for advanced batteries, catalysts, polymers, and therapeutic molecules.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AL-Generative Model Couplings in Inverse Design Studies

| Study Focus (Year) | Generative Model | AL Query Strategy | Initial Pool Size | Number of AL Cycles | Candidates Evaluated | Performance Improvement vs. Random Search | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic LED Molecules (2023) | cVAE | Expected Improvement (EI) | 50,000 | 20 | 500 | 180% | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield |

| Porous Organic Polymers (2022) | WGAN-GP | Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | 100,000 | 15 | 300 | 220% | Methane Storage Capacity |

| Perovskite Catalysts (2023) | GraphVAE | Query-by-Committee (QBC) | 20,000 | 10 | 200 | 150% | Oxygen Evolution Reaction Activity |

| Antimicrobial Peptides (2024) | LatentGAN | Thompson Sampling | 75,000 | 25 | 1,000 | 300% | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration |

Table 2: Computational Cost-Benefit Analysis per AL Cycle

| Process Step | Typical Time/Cost (VAE-based) | Typical Time/Cost (GAN-based) | Primary Hardware Dependency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate Generation (1000 samples) | 1-5 minutes | 2-10 minutes | GPU (CUDA cores) |

| Surrogate Model Inference & Uncertainty Quantification | 2-10 minutes | 2-10 minutes | CPU/GPU |

| AL Query Selection | < 1 minute | < 1 minute | CPU |

| High-Fidelity Evaluation (DFT, MD) | Hours to Days | Hours to Days | HPC Cluster (CPU) |

| Retraining Generative Model | 30-120 minutes | 60-180 minutes | GPU (VRAM) |

| Retraining Surrogate Model | 10-60 minutes | 10-60 minutes | GPU |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: End-to-End AL-VAE Cycle for Inorganic Crystal Design

Objective: To discover new inorganic crystal structures with target formation energy and band gap.

Materials: (See The Scientist's Toolkit)

Methodology:

- Initial Dataset Curation: Assemble a database (e.g., from Materials Project) of known crystal structures (

CIFfiles) and their computed properties. Encode crystals into a universal representation (e.g., Sine Coulomb Matrix, ElemNet descriptors). - Pre-training the VAE:

- Train a VAE (encoder-decoder pair) to reconstruct the crystal representations. The encoder maps structures to a latent vector

z, the decoder reconstructs them fromz. - Use a combined loss:

L = MSE(Reconstruction) + β * KL-Divergence(z, N(0,1)). - Validate reconstruction accuracy and ensure the latent space is smooth and interpolatable.

- Train a VAE (encoder-decoder pair) to reconstruct the crystal representations. The encoder maps structures to a latent vector

- Initial Surrogate Model Training: Train a separate supervised regressor (e.g., Gaussian Process, Graph Neural Network) on the initial dataset to predict target properties from the latent vector

zor the structure itself. - Active Learning Loop:

a. Candidate Generation: Sample a large pool of latent vectors (

N=50,000) from the prior distribution or by perturbing known high-performance points. b. Candidate Decoding: Use the VAE decoder to generate crystal structures for the sampled latent vectors. c. Virtual Screening: Use the surrogate model to predict properties and associated uncertainty for all generated candidates. d. Query Selection: Apply the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function:EI(z) = (μ(z) - y_best - ξ) * Φ(Z) + σ(z) * φ(Z), whereμandσare the surrogate's predicted mean and uncertainty,y_bestis the best observed property, andΦ,φare standard normal CDF and PDF. Select the topk=20candidates maximizing EI. e. High-Fidelity Evaluation: Perform DFT calculations on the selectedkcandidates to obtain accurate formation energies and band gaps. f. Data Augmentation: Add the newly evaluated (candidate, property) pairs to the training dataset. g. Model Retraining: Periodically retrain the surrogate model on the augmented dataset. Optionally fine-tune the VAE on the new data every 5-10 cycles. - Termination & Validation: Halt after a fixed budget (e.g., 200 DFT evaluations) or upon discovery of a candidate meeting all target criteria. Validate top hits with more precise computational methods or propose for experimental synthesis.

Protocol 2: AL-GAN for de novo Drug-Like Molecule Generation

Objective: To generate novel, synthetically accessible small molecules with high predicted affinity for a target protein.

Materials: (See The Scientist's Toolkit)

Methodology:

- Chemical Space Foundation: Pre-train a GAN (e.g., ORGAN, LatentGAN) or a chemical language model on a large dataset of known drug-like molecules (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) represented as SMILES strings or molecular graphs.

- Establishing the Surrogate: Train a

Random ForestorMessage-Passing Neural Network(MPNN) as an initial predictor of binding affinity (pIC50) using available bioassay data for the target. - Exploration-Exploitation Loop:

a. Generation: Use the trained generator to produce a diverse pool of 100,000 candidate molecules.

b. Filtering: Apply standard ADMET and synthetic accessibility (SA) filters to reduce the pool to 10,000 plausible candidates.

c. Prediction & Uncertainty: Use the surrogate model to predict

pIC50. For uncertainty, use ensemble methods (e.g., training 5 different models) to estimate prediction variance. d. Acquisition: Use theUpper Confidence Bound (UCB)strategy:UCB = μ + κ * σ, whereκbalances exploration (highσ) and exploitation (highμ). Select the top 50 molecules by UCB. e. In Silico Validation: Perform molecular docking for the 50 selected candidates against the target protein to obtain a more reliable, though still approximate, binding score. f. Selection for Assay: Based on docking scores and novelty, select 10-15 molecules for in vitro synthesis and binding assay. g. Feedback: Add the assay results (molecule, measuredpIC50) to the training data. h. Model Update: Retrain the surrogate model on the expanded data. Periodically retrain the GAN generator using a reinforcement learning reward signal based on the surrogate model's predictions to bias generation towards high-affinity regions. - Hit Confirmation: After 5-10 cycles, prioritize the best-confirmed hits for lead optimization and further biological testing.

Visualization

Diagram 1: High-Level AL-Generative Model Coupling Workflow

Diagram 2: Comparative Architecture: AL-VAE vs. AL-GAN

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for Computational Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Information File (CIF) | Standard text file format for representing crystallographic structures. Serves as the primary input for inorganic materials design. | Files from the Materials Project, ICSD. |

| Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) | A string notation for representing molecular structures. The standard language for chemical generative models. | RDKit library for parsing and generation. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code | High-fidelity computational method for calculating electronic structure, energy, and properties of materials/molecules. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian. |

| High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) Pipeline | Automated workflow to prepare, run, and analyze thousands of computational experiments (e.g., docking, DFT). | AiiDA, FireWorks, Knime. |

| Active Learning Library | Provides implementations of acquisition functions (EI, UCB, Thompson Sampling) and cycle management. | modAL, DeepChem, ALiPy. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Platform for building, training, and deploying VAEs, GANs, and surrogate models. | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX. |

| Surrogate Model Ensemble | Multiple instances of a predictive model to estimate uncertainty via committee disagreement or bootstrapping. | Scikit-learn, PyTorch Ensembles. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Force Field | Parameterized potential energy function for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | CHARMM, AMBER, OpenMM. |

| Synthetic Accessibility Score (SA) | A computational metric estimating the ease with which a proposed molecule can be synthesized. | RDKit's SA Score, RAscore. |

| ADMET Prediction Tool | Software for predicting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity properties in early drug design. | SwissADME, pkCSM, ADMETlab. |

Overcoming Challenges: Optimizing Active Learning for Complex Material Landscapes

Inverse materials design aims to discover materials with target properties by navigating a vast, complex chemical space. Active learning (AL) cycles are central to this, where machine learning models iteratively propose candidates for experimental synthesis and testing. The initial dataset, used to train the first model (iteration zero), is critical. A biased or non-representative "cold start" dataset can lead to models that explore only local optima, missing superior regions of the chemical space. This protocol details strategies to curate an initial dataset that maximizes diversity, minimizes bias, and accelerates the convergence of AL cycles toward high-performance materials or molecular candidates relevant to drug development.

Foundational Protocols for Initial Curation

Protocol 2.1: Diversity-Driven Chemical Space Sampling