From Prediction to Lab: A Practical Guide to Experimentally Validating Synthesizability in Drug and Material Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of experimentally validating computational synthesizability predictions.

From Prediction to Lab: A Practical Guide to Experimentally Validating Synthesizability in Drug and Material Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of experimentally validating computational synthesizability predictions. It bridges the gap between in-silico models and real-world synthesis by covering foundational principles, practical methodologies, troubleshooting for failed syntheses, and robust validation techniques. Drawing on the latest research, the content offers a actionable framework for confirming the synthesizability of small-molecule drug analogs and inorganic crystalline materials, thereby increasing the efficiency and success rate of discovery pipelines.

Understanding Synthesizability Prediction: The Bridge Between Computation and Experiment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental limitation of using thermodynamic stability alone to assess synthesizability?

Thermodynamic stability, often assessed via formation energy or energy above the convex hull (E hull ), is an insufficient metric for synthesizability. A material with a favorable, negative formation energy can remain unsynthesized, while metastable structures with less favorable thermodynamics are regularly synthesized in laboratories. Synthesis is a complex process influenced by kinetic factors, precursor availability, choice of synthetic pathway, and reaction conditions—factors that pure thermodynamic calculations do not capture [1] [2].

Q2: What are the primary computational methods for predicting synthesizability, and how do they compare?

Modern approaches move beyond simple heuristics to more direct predictive modeling. The table below summarizes key methods.

| Method | Core Principle | Key Metric/Output | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrosynthesis Models [3] | Predicts viable synthetic routes from target molecule to available building blocks. | Binary outcome: Solved/Not Solved; or a score (e.g., RA score). | Organic small molecules, drug candidates. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) [1] | Fine-tuned on databases of synthesizable/non-synthesizable structures to predict synthesizability directly. | Synthesis probability/classification (e.g., 98.6% accuracy). | Inorganic crystal structures. |

| Heuristic Scores [3] | Assesses molecular complexity based on fragment frequency in known databases. | Score (e.g., SA Score, SYBA). | Initial, fast screening of "drug-like" molecules. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers [2] | Trained on crystal structure data (e.g., FTCP representation) to classify synthesizability. | Synthesizability Score (SC) (e.g., 82.6% precision). | Inorganic crystalline materials. |

Q3: How can I validate a synthesizability prediction for a novel organic molecule?

The most robust validation method involves using a retrosynthesis planning tool, such as AiZynthFinder or IBM RXN, to propose a viable synthetic pathway [3]. The experimental protocol is as follows:

- Input: Provide the SMILES string or structure file of the target molecule.

- Constraint Setting: Define your available building blocks (e.g., common commercial reagents) and permitted reaction types.

- Pathway Evaluation: Run the retrosynthesis algorithm. A molecule is deemed "synthesizable" if the software can propose a complete route from available starting materials.

- Experimental Corroboration: The ultimate validation is to execute the top-ranked proposed synthesis in the lab.

Q4: Why might a molecule with a poor heuristic score (e.g., SA Score) still be synthesizable?

Heuristic scores are based on the frequency of molecular substructures in known databases. They measure "molecular complexity" or "commonness" rather than true synthetic feasibility. A molecule with a rare or complex-looking structure (poor score) may still have a straightforward, viable synthetic route that the heuristic fails to capture [3]. Over-reliance on these scores can overlook promising chemical spaces.

Q5: What specific experimental factors should I consider when moving from a predicted synthesizable material to a lab synthesis?

Beyond a predicted route or score, you must account for:

- Precursor Accessibility: Are the required starting materials commercially available or easily prepared? [1]

- Reaction Conditions: Consider the practicality of the required temperature, pressure, and reaction time [2].

- Chemical Compatibility: Ensure functional groups are compatible with the proposed reaction sequence.

- Purification: Assess the feasibility of isolating the target compound from the reaction mixture.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Synthesizability Score but No Viable Retrosynthetic Pathway

Symptoms

A novel small molecule receives a high synthesizability score from a heuristic or ML model, but a retrosynthesis tool fails to find a pathway.

Diagnostic Steps

- Verify Model Domain: Confirm the synthesizability model was trained on data relevant to your molecule (e.g., drug-like molecules vs. functional materials) [3].

- Check Building Blocks: Retrosynthesis models rely on a defined set of starting materials. Ensure your tool's building block library is comprehensive and includes the necessary reagents for your molecule class [3].

- Analyze Structural Motifs: Manually inspect the molecule for highly strained rings, unstable functional groups, or structural patterns absent from known reaction databases.

Solutions

- Expand Search Parameters: Widen the scope of allowed reactions and building blocks in the retrosynthesis tool.

- Iterative Design: Use the "unsynthesizable" result to inform the design of similar, more accessible analogs. Some models can project unsynthesizable molecules into synthesizable ones [3].

- Expert Consultation: Engage a synthetic chemist to evaluate potential non-algorithmic routes.

Issue 2: Discrepancy Between Thermodynamic and Data-Driven Synthesizability Predictions

Symptoms

A theoretical crystal structure is thermodynamically stable (low E hull ) but is predicted to be non-synthesizable by a data-driven model (e.g., CSLLM or SC score), or vice-versa.

Diagnostic Steps

- Assess Kinetic Stability: Calculate the phonon spectrum of the material. Imaginary frequencies indicate kinetic instability, which can prevent synthesis, even if the structure is thermodynamically stable [2].

- Investigate Training Data: Understand what the data-driven model learned. For instance, a model trained on experimental data (like CSLLM) may identify complex, non-thermodynamic patterns associated with successful synthesis [1].

- Precursor Analysis: Use a precursor prediction model (like the Precursor LLM in CSLLM) to see if suitable solid-state or solution-based precursors exist [1].

Solutions

- Prioritize Data-Driven Predictions: For systems with abundant experimental data, trust the ML model's prediction over E hull alone, as it incorporates more complex, real-world factors [1].

- Explore Alternative Synthesis Routes: If the model suggests synthesizability, investigate non-standard conditions (e.g., high pressure, non-aqueous solvents) suggested by the "Method LLM" [1].

- Validate Experimentally: Proceed with a targeted synthesis attempt for the most promising candidates, using the model's insights to guide the experimental design.

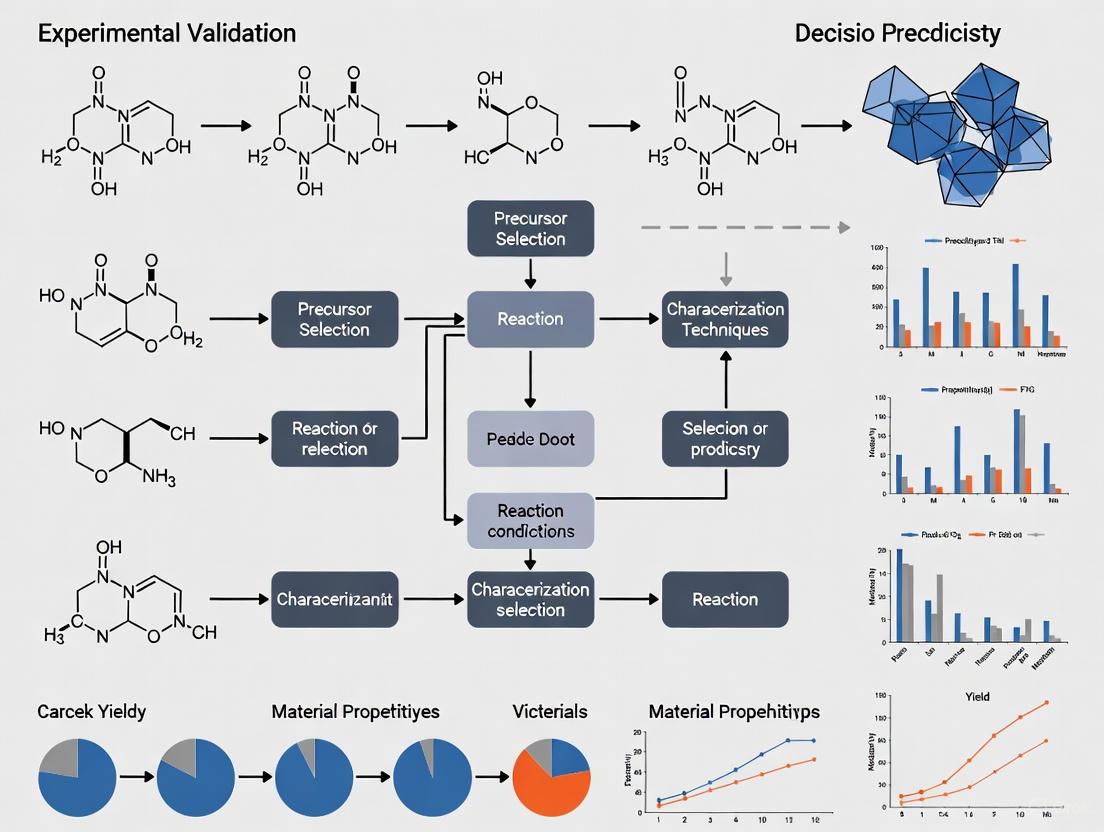

Experimental Validation Workflow

The following diagram outlines a robust workflow for experimentally validating synthesizability predictions, integrating both computational and lab-based steps.

This table details essential computational and experimental resources for conducting synthesizability research.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Retrosynthesis Software (e.g., AiZynthFinder, IBM RXN) [3] | Predicts synthetic pathways for a target molecule. | Check the scope of the built-in reaction template library and building block database. |

| Synthesizability LLMs (e.g., CSLLM) [1] | Directly predicts the synthesizability of crystal structures and suggests precursors. | Requires a text-based representation of the crystal structure (e.g., CIF, POSCAR). |

| Commercial Building Block Libraries (e.g., Enamine, Sigma-Aldrich) | Source of starting materials for proposed synthetic routes. | Prioritize readily available and affordable reagents to increase practical feasibility [3]. |

| Heuristic Scoring Tools (e.g., SA Score, SYBA) [3] | Provides a fast, initial complexity estimate for molecules. | Use for initial triage, not as a definitive synthesizability metric. Can be well-correlated with retrosynthesis in drug-like space [3]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Rigs | Allows for rapid, parallel experimental testing of multiple synthetic conditions or precursors. | Essential for efficiently validating predictions for a large set of candidate materials [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Synthesizability Predictions

FAQ: Addressing Common Experimental-Simulation Gaps

Q1: My DFT simulations show a candidate material is stable on the convex hull (Ehull = 0), but repeated synthesis attempts fail. Why? This common issue arises because the Energy Above Hull is a thermodynamic metric calculated at 0 K, but real synthesis is governed by finite-temperature kinetics and pathways.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Investigate Kinetic Barriers: A zero Ehull confirms thermodynamic stability but does not guarantee a viable kinetic pathway for formation. The material may be trapped in a metastable state.

- Check Phase Competition: Examine if your target phase decomposes into other polymorphs or compounds under your synthesis conditions. The existence of multiple polymorphs with similar energies complicates selective synthesis [2].

- Validate Synthesis Parameters: Recalculate the Ehull using functionals that account for entropic contributions or finite-temperature effects, if computationally feasible. Experimentally, consider alternative synthesis routes like chemical vapor transport or flux methods that can lower kinetic barriers.

Q2: I am screening a ternary oxide, and the charge-balancing rule flags it as "forbidden," yet I found a published paper reporting its synthesis. Is the filter wrong? Yes, the rigid charge-balancing filter can produce false negatives. It is an imperfect proxy because it cannot account for different bonding environments, such as metallic or covalent character, which allow for non-integer oxidation states and charge transfer [4].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Quantify Filter Reliability: Recognize that charge-balancing alone is a weak predictor. One study found only 37% of synthesized inorganic materials in a database were charge-balanced according to common oxidation states [4].

- Use Complementary Filters: Augment the charge neutrality check with other human-knowledge filters, such as electronegativity balance or stoichiometric variation analysis [5].

- Employ a Data-Driven Model: Use a machine learning-based synthesizability model (e.g., SynthNN) that learns the complex relationships between composition, structure, and synthesizability from all known materials, going beyond rigid rules [4].

Q3: How reliable is a slightly positive Energy Above Hull (e.g., 50 meV/atom) as a synthesizability filter? The reliability of a positive Ehull is highly system-dependent. While a high Ehull (e.g., > 200 meV/atom) generally indicates instability, many metastable materials with low positive Ehull are synthesizable.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Consult Experimental Databases: Search the ICSD and literature for analogous materials. If known metastable phases (e.g., diamond, martensite) exist in similar chemical systems, your candidate might be synthesizable [6].

- Consider Synthesis-Derived Stabilization: Materials can be stabilized by kinetics, entropy, or specific synthesis conditions not captured by DFT. High-pressure or low-temperature synthesis can access metastable phases [6].

- Use a Probabilistic Framework: Instead of a hard Ehull cutoff, use a machine learning model that outputs a synthesizability score (SC). One such model reported an 82.6% precision in identifying synthesizable ternary crystals, which is often more accurate than an Ehull threshold [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common Synthesizability Proxies

| Proxy Metric | Underlying Principle | Key Quantitative Limitation | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge Balancing | Chemical intuition (ionic charge neutrality) | Inflexible; ignores covalent/metallic bonding [4]. | Only 37% of known synthesized inorganic materials are charge-balanced [4]. |

| Energy Above Hull (Ehull) | Thermodynamic stability at 0 K | Fails to account for kinetics, entropy, and finite-temperature effects [7] [6]. | Captures only ~50% of synthesized inorganic materials [4]. |

| Machine Learning (SynthNN) | Data-driven patterns from all known materials | Requires large, clean datasets; can be a "black box." [4] | 1.5x higher precision than human experts and completes tasks much faster [4]. |

Table 2: A Toolkit for Experimental Validation of Synthesizability Predictions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Validating Synthesizability |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Automated Laboratory | Executes synthesis recipes from computational planning at scale, enabling rapid experimental feedback on dozens of candidates [7]. |

| Literature-Mined Synthesis Data | Provides real-world reaction conditions (precursors, temperature) to ground-truth computational predictions and plan feasible experiments [7] [6]. |

| Human-Curated Dataset (e.g., Ternary Oxides) | Offers a high-quality, reliable benchmark for evaluating and improving both computational filters and data-driven models, as text-mined data can have low accuracy [6]. |

| Retrosynthesis Models (e.g., AiZynthFinder) | For molecular materials, these models propose viable synthetic routes, offering a more nuanced assessement of synthetic accessibility than simple scores [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating with a Human-Curated Solid-State Synthesis Dataset

This protocol uses high-quality, manually extracted data to assess the false positive/negative rate of your synthesizability filters [6].

Data Curation:

- Source a list of candidate compositions from your computational pipeline.

- Manually extract synthesis information from the literature for these compositions using resources like the ICSD, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- For each composition, label it as "solid-state synthesized" if a solid-state synthesis is reported, or "non-solid-state synthesized" if it was made by other methods (e.g., sol-gel, flux). Record details like highest heating temperature, atmosphere, and precursors.

Model Benchmarking:

- Apply your computational proxies (e.g., Ehull threshold, charge-balancing) to the curated list of compositions.

- Compare the predictions against the manual labels to calculate precision, recall, and identify specific failure cases (e.g., compounds that are synthesizable but violate charge neutrality).

PU Learning Application:

- Use the reliable "solid-state synthesized" data as positive labels.

- Treat a large set of hypothetical compositions from databases like the Materials Project as unlabeled data.

- Train a Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to probabilistically identify synthesizable materials from the unlabeled set, providing a data-driven prioritization list [6].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Experimental Feedback Loop

This protocol, derived from state-of-the-art research, closes the loop between prediction and experimental validation [7].

Candidate Prioritization:

- Screen a large pool of computational structures (e.g., from the Materials Project, GNoME) using an ensemble synthesizability score that combines both compositional and structural models.

- Rank candidates using a rank-average ensemble and apply practical filters (e.g., excluding toxic or rare elements).

Synthesis Planning:

- For the top-ranked candidates, use a precursor-suggestion model (e.g., Retro-Rank-In) to generate a list of viable solid-state precursors.

- Employ a synthesis condition model (e.g., SyntMTE) to predict the calcination temperature required to form the target phase. Balance the reaction and compute precursor quantities.

Automated Synthesis & Characterization:

- Execute the synthesis recipes in a high-throughput automated laboratory.

- Characterize the resulting products using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

- Compare the experimental XRD pattern to the computationally predicted pattern of the target structure to confirm successful synthesis. This process has been shown to successfully synthesize target materials, including novel ones, within days [7].

Protocol 3: Integrating Retrosynthesis Tools for Molecular Materials

For organic molecules or metal-organic frameworks, synthesizability is often assessed by the existence of a plausible synthetic route [8].

Route Solving:

- Input the SMILES string of your target molecule into a retrosynthesis tool (e.g., AiZynthFinder, SYNTHIA).

- Configure the tool to use a library of available building blocks and reaction templates.

- Run the search to determine if the tool can find one or more viable routes to the target molecule.

Synthesizability Optimization:

- In generative molecular design, directly integrate the retrosynthesis tool's output (e.g., a binary "solved/not solved" flag or a score) into the multi-parameter optimization objective.

- This guides the generative model to propose structures that are not only optimal in terms of properties (e.g., binding affinity) but also have a higher likelihood of being synthesizable, as deemed by the retrosynthesis model [8].

Workflow Visualization: From Prediction to Validation

Validating Synthesizability Predictions Workflow

FAQs: Predictive Models and Experimental Validation

What are the fundamental types of predictive models used in research?

Predictive models can be broadly categorized into several types, each suited for different kinds of data and research questions [9]:

- Classification Models: These models place data into specific categories (e.g., yes/no) based on historical data. They are ideal for answering discrete questions, such as "Is this transaction fraudulent?" or "Will this patient respond to the treatment?" [9].

- Clustering Models: These models sort data into separate, nested groups based on similar attributes without pre-defined categories. This is useful for patient stratification or identifying patterns in molecular profiles [9] [10].

- Forecast Models: These are among the most widely used models and deal with metric value prediction. They estimate numerical values for new data based on historical data, such as predicting inventory needs or the volume of experimental results [9].

- Outliers Models: These models are designed to identify anomalous data entries within a dataset. They are critical for detecting fraud, experimental errors, or unusual biological responses [9].

- Time Series Models: This type involves a sequence of data points collected over time. It uses historical data to forecast future values, considering trends and seasonal variations, which is useful for monitoring tumor progression or long-term experimental outcomes [9] [10].

How do I validate a predictive model to ensure its results are reliable for my research?

Proper validation is critical to ensure your predictive model is robust and not overfitted to your initial dataset. Key strategies include [11] [12]:

- Data Splitting: Partition your dataset into a training set (to build the model) and a testing set (to evaluate its performance). The split should be random, and both datasets must be representative of the actual population. A third validation dataset is often used to provide an unbiased evaluation of the final model and to tune model parameters [12].

- Cross-Validation: This technique, such as k-fold cross-validation, repeatedly partitions the data into different training and test sets. It helps ensure that your model's performance is consistent and not dependent on a single, potentially lucky, data split [11] [12].

- Comparison with Experimental Data: For research validation, directly compare the model's predictions against results from experimental models. In oncology, for instance, this involves cross-validating AI predictions with data from patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), organoids, or tumoroids to ensure biological relevance [10].

- Managing Bias and Variance: Strive to balance bias (error from erroneous assumptions) and variance (error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set). A good model should have low bias and low variance [12].

What are common pitfalls when training predictive models, and how can I troubleshoot them?

Researchers often encounter several specific issues during model development. The table below outlines common problems and their solutions.

| Problem | Description | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Overfitting | Model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen test data. It has essentially "memorized" the noise in the training set. | - Simplify the model by reducing the number of parameters [9].- Apply cross-validation to get a better estimate of real-world performance [11] [12].- Increase the size of your training dataset if possible [10]. |

| Data Imbalance | The dataset has very few examples of one class (e.g., active compounds) compared to another (inactive compounds), biasing the model toward the majority class [13]. | - Use resampling techniques (oversampling the minority class or undersampling the majority class) [13].- Utilize algorithms like Random Forest that are relatively resistant to overfitting and can handle imbalance [9].- Employ appropriate evaluation metrics like F1-score instead of just accuracy [9]. |

| Model Interpretability ("Black Box") | It is difficult to understand how a complex model (e.g., deep neural network) arrived at a specific prediction, which is a significant hurdle for scientific acceptance [10]. | - Use Explainable AI (XAI) techniques to interpret model decisions [10].- Perform feature importance analysis to identify which input variables had the most significant impact on the prediction [10].- Consider using inherently more interpretable models like Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) or decision trees where appropriate [9]. |

| Insufficient or Low-Quality Data | The model's performance is limited by a small dataset, missing values, or high experimental error in the training data [14] [10]. | - Perform rigorous data preprocessing: handle missing values, normalize data, and remove outliers [9].- Engage domain experts to guide data curation and feature engineering [9] [12].- Leverage data from public repositories and biobanks to augment your dataset [10]. |

How are Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 being applied in predictive tasks within materials science and drug discovery?

LLMs are moving beyond text generation to become powerful tools for scientific prediction. Key applications include [13]:

- Intelligent Data Extraction: LLMs can mine vast scientific literature to extract valuable, unstructured information such as synthesis conditions and material properties, creating structured, queryable databases for downstream predictive modeling [13].

- Predicting Synthesis Conditions: Fine-tuned LLMs can act as "recommender" tools, predicting feasible synthesis conditions for novel materials based on textual descriptions of their precursors or composition [13].

- Learning Structure-Property Relationships: By training on comprehensive datasets of chemical information, LLMs can learn the complex relationships between a material's structure and its properties. For example, they can achieve high accuracy in predicting hydrogen storage performance or synthesisability from rich text descriptions of atomic-level structures [13].

- Multi-Agent Experimental Systems: The most advanced applications use an LLM as a central "brain" to coordinate research workflows. These systems can plan multi-step procedures, interface with simulation tools, and even operate robotic platforms for automated experimentation [13].

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for using and validating an LLM for synthesizability predictions.

What experimental protocols are used to validate AI-driven predictions in oncology research?

In fields like oncology, computational predictions must be rigorously validated through biological experiments. A standard protocol involves these key methodologies [10]:

Cross-Validation with Patient-Derived Models:

- Purpose: To compare AI predictions against biological responses in models that closely mimic human disease.

- Methodology: Predictions of drug efficacy or tumor behavior are tested in vitro and in vivo using Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs), organoids, and tumoroids. For example, a model predicting the response to a targeted therapy is validated against the actual response observed in a PDX model carrying the same genetic mutation [10].

Longitudinal Data Integration for Model Refinement:

- Purpose: To improve the predictive accuracy of AI algorithms over time by incorporating dynamic, time-series data.

- Methodology: Time-series data from experimental studies, such as tumor growth trajectories from PDX models, is fed back into the AI system. This data is used to retrain and refine the predictive models, ensuring they better reflect real-world biological dynamics [10].

Multi-Omics Data Fusion for Enhanced Prediction:

- Purpose: To capture the complexity of tumor biology by integrating diverse biological datasets.

- Methodology: AI platforms unify data from genomics (mutations), transcriptomics (gene expression), and proteomics (protein interactions). This integrated dataset is used to build and validate models, ensuring predictions account for the multi-faceted nature of cancer [10]. For instance, this approach can identify novel biomarkers that are subsequently validated in clinical studies [10].

The workflow for this validation process is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and computational tools used in developing and validating predictive models for drug discovery and materials science.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) | In vivo models where human tumor tissue is implanted into immunodeficient mice. They are a gold standard for validating predictions of drug efficacy and tumor behavior as they retain the genetic and histological characteristics of the original patient tumor [10]. |

| Organoids & Tumoroids | 3D in vitro cell cultures that self-organize into structures mimicking organs or tumors. They are used for medium-throughput validation of drug responses and for studying biological mechanisms in a controlled environment [10]. |

| Multi-Omics Datasets | Integrated datasets comprising genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. They are used to train AI models and provide a holistic view of tumor biology, enabling more accurate predictions of therapeutic outcomes [10]. |

| Random Forest Algorithm | A popular machine learning algorithm capable of both classification and regression. It is accurate, efficient with large databases, resistant to overfitting, and can estimate which variables are important in classification [9]. |

| Generalized Linear Model (GLM) | A flexible generalization of linear regression that allows for response variables with non-normal distributions. It trains quickly, is relatively straightforward to interpret, and provides a clear understanding of predictor influence [9]. |

| Open-Source LLMs (e.g., Llama, Qwen) | Large language models with publicly available weights and architectures. They offer an alternative to closed-source models, providing greater transparency, reproducibility, cost-effectiveness, and data privacy for scientific tasks like data extraction and prediction [13]. |

The Critical Need for Experimental Validation in the Discovery Workflow

FAQs on Synthesizability Prediction and Validation

Q1: What is the difference between thermodynamic stability and synthesizability? Thermodynamic stability, often assessed via formation energy or energy above the convex hull (Ehull), is a traditional but insufficient proxy for synthesizability. Many metastable structures (with less favorable formation energies) are successfully synthesized, while numerous structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized. Synthesizability is a more complex property influenced by kinetic factors, precursor availability, and specific reaction conditions [1] [2].

Q2: Why is experimental validation crucial for computational synthesizability predictions? Computational models, while powerful, require experimental "reality checks." Validation confirms that the proposed method is practically useful and that the claims put forth are correct. Without it, claims that a newly generated material or molecule has better performance are difficult to substantiate [15].

Q3: A model predicted my compound is synthesizable, but my experiments are failing. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge. The issue often lies in the transfer from general synthesizability to your specific lab context.

- Precursor Availability: The prediction might assume an infinite supply of building blocks, while your in-house resources are limited. Re-run synthesis planning with your specific available precursors [16].

- Synthetic Method: The predicted synthetic route (e.g., solid-state vs. solution) may not be optimal for your compound. Verify that the suggested method aligns with the material's properties [1].

- Reaction Kinetics: While the reaction may be thermodynamically feasible, kinetic barriers could be preventing it. Investigate alternative reaction conditions like temperature, pressure, or catalysts.

Q4: How can I adapt general synthesizability predictions to my laboratory's specific available resources? You can develop a rapidly retrainable, in-house synthesizability score. This involves using Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) tools configured with your specific inventory of building blocks to generate training data. A model trained on this data can then accurately predict whether a molecule is synthesizable with your in-house resources [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Validation

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Investigation & Action |

|---|---|---|

| Failed Synthesis | Incorrect or unavailable precursors. | Verify precursor stability and purity; use CASP with your building block inventory to find viable alternatives [1] [16]. |

| Synthetic method misalignment. | Re-evaluate the recommended method (e.g., solid-state, solution); consult literature for analogous compounds [1]. | |

| Unfavorable reaction kinetics. | Systematically vary reaction conditions (temperature, time, pressure) to overcome kinetic barriers. | |

| Impure Product | Side reactions or incomplete conversion. | Analyze byproducts; optimize reaction stoichiometry and purification protocols (e.g., recrystallization, chromatography). |

| Property Mismatch | Incorrect crystal structure or phase. | Use characterization (XRD, NMR) to confirm the synthesized structure matches the predicted one; check for polymorphs [15]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Synthesizability Assessment Methods

The table below summarizes different approaches to evaluating synthesizability, highlighting the performance of modern machine learning methods.

| Assessment Method | Key Metric | Reported Performance / Limitation | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability [1] [2] | Energy above hull (Ehull) | ~74.1% accuracy; insufficient as many metastable structures are synthesizable. | Assumes thermodynamic stability implies synthesizability. |

| Kinetic Stability [1] | Phonon spectrum (lowest frequency) | ~82.2% accuracy; structures with imaginary frequencies can be synthesized. | Assesses dynamic stability against small displacements. |

| Crystal-likeness Score (CLscore) [2] | ML-based score | 86.2% recall for synthesized materials; used to filter non-synthesizable structures. | Machine learning model trained on existing crystal data. |

| Synthesizability Score (SC) [2] | ML-based classification | 82.6% precision, 80.6% recall for ternary crystals. | Fourier-transformed crystal properties with a deep learning classifier. |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [1] | LLM-based classification | 98.6% accuracy; demonstrates high generalization to complex structures. | Large language model fine-tuned on a comprehensive dataset of crystal structures. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Solid-State Synthesis from Computational Predictions

This protocol provides a general workflow for experimentally validating the synthesizability of a predicted inorganic crystal structure.

1. Precursor Preparation:

- Based on the Precursor LLM output or CASP suggestion, identify solid-state precursors (e.g., metal oxides, carbonates).

- Weigh precursors according to the stoichiometry of the target compound.

- Use a mortar and pestle or a ball mill to mix and grind the precursors thoroughly to ensure homogeneity and increase surface area for reaction.

2. Initial Heat Treatment:

- Place the mixed powder in a high-temperature crucible (e.g., alumina, platinum).

- Insert the crucible into a box furnace or tube furnace.

- Heat the sample at a moderate rate (e.g., 5-10°C per minute) to a target temperature below the final sintering temperature for calcination. This step decomposes carbonates or nitrates and initiates solid-state diffusion.

- After calcination, allow the furnace to cool naturally. Re-grind the powder to ensure homogeneity.

3. Final Sintering and Phase Formation:

- Press the calcined powder into pellets using a hydraulic press to improve inter-particle contact.

- Sinter the pellets at the final, higher temperature (determined from literature or phase diagrams) for an extended period (e.g., 12-48 hours) to facilitate complete reaction and crystal growth.

4. Product Characterization:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Grind a portion of the sintered pellet and analyze its powder XRD pattern. Compare the measured pattern to the computationally predicted crystal structure to confirm successful synthesis and phase purity.

- Additional Techniques: Use techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) for elemental composition analysis.

Protocol 2: Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) for Small Molecules

This protocol outlines using CASP to plan and validate the synthesis of small organic molecules.

1. Input the Target Molecule:

- Provide the structure of the target molecule in a standard format (e.g., SMILES) to a CASP tool (e.g., AiZynthFinder).

2. Configure Building Block Settings:

- For general synthesizability, use a large commercial building block database (e.g., Zinc, ~17.4 million compounds).

- For in-house synthesizability, configure the tool to use your specific, limited inventory of available building blocks (e.g., 6,000 compounds) [16].

3. Execute Retrosynthetic Analysis:

- Run the CASP algorithm. It will recursively deconstruct the target molecule into simpler precursors until it identifies a pathway to your available building blocks.

- Note that using a limited in-house inventory may result in synthesis routes that are, on average, two steps longer than those using a full commercial database [16].

4. Evaluate and Select a Synthesis Route:

- Review the proposed routes based on the number of steps, predicted yields, and the familiarity/reliability of the suggested reactions.

- Use this CASP-generated route as a guide for laboratory synthesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Solid-State Precursors | High-purity powders (e.g., metal oxides, carbonates) that react to form the target inorganic crystal material [1]. |

| Molecular Building Blocks | Commercially available or in-house stockpiled organic molecules used as starting materials in CASP-planned syntheses [16]. |

| CASP Software | Computer-aided synthesis planning tools that deconstruct target molecules into viable synthesis routes using available building blocks [16]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | A curated database of experimentally synthesized crystal structures, used as a source of ground-truth data for training and validating synthesizability models [1] [2]. |

Experimental Validation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates a robust, iterative workflow for validating computational synthesizability predictions through experimentation.

Integrating Prediction with Experimental Validation

This diagram outlines the full discovery pipeline, from initial computational design to experimental validation and model refinement.

A Blueprint for Experimental Validation: From Candidate Selection to Synthesis

FAQs: Core Concepts of Synthesizability and Screening

Q1: What is a synthesizability score, and why is it crucial for my research? A synthesizability score is a computational prediction of the likelihood that a proposed molecular or material structure can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory. It is crucial because it bridges the gap between in-silico design and real-world experimental validation. Relying solely on stable, low-energy structures from simulations like Density Functional Theory (DFT) often leads to candidates that are not experimentally accessible, as these calculations can overlook finite-temperature effects and kinetic factors [7]. Using a synthesizability score helps prioritize candidates that are not just theoretically stable, but also practically makeable, saving significant time and resources [17].

Q2: What is the difference between general and in-house synthesizability? The key difference lies in the availability of building blocks or precursors:

- General Synthesizability assumes a near-infinite supply of commercially available building blocks (e.g., from databases like Zinc with 17.4 million compounds) [18].

- In-House Synthesizability is tailored to a specific laboratory's limited, available stock of building blocks (e.g., 6,000 compounds). This reflects the real-world constraints of a research environment. While using an in-house set may result in synthesis routes that are, on average, two reaction steps longer, the drop in overall synthesis planning success can be as low as -12% compared to a vast commercial library [18].

Q3: What is rank-based screening, and how is it better than using a fixed threshold? Rank-based screening is a method for ordering a large pool of candidate molecules or materials based on their synthesizability scores and other desired properties. Instead of applying a fixed probability cutoff (e.g., >0.8), candidates are ranked relative to each other. A powerful method is the rank-average ensemble (or Borda fusion), which combines rankings from multiple models [7]. This method is superior to a fixed threshold because it provides a relative measure of synthesizability within your specific candidate pool, ensuring you select the most promising candidates for your particular project, even if absolute probabilities are low.

Q4: My top-ranked candidate failed synthesis. What are the most likely reasons? Several factors can lead to this discrepancy:

- Gaps in Training Data: The synthesizability model may not have been trained on data representative of your specific chemical space or synthesis conditions [7].

- Precursor Impurities or Availability: The suggested synthesis route might rely on precursors that are impure, unavailable, or unstable in your lab [18].

- Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control: The model may predict thermodynamic stability, but the synthesis might be kinetically hindered, requiring specific reaction conditions not captured by the plan [7].

- In-House Building Block Mismatch: The general synthesizability score might have ranked the candidate highly, but your specific in-house building block collection may not allow for an efficient route, leading to failure or impure products [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Success Rate in Synthesis Planning (CASP) with In-House Building Blocks

- Symptoms: Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) tools fail to find routes for a high percentage of your candidate molecules when configured with your lab's building block list.

- Investigation Steps:

- Benchmark Your Setup: Test your CASP tool on a standard dataset (e.g., a drug-like ChEMBL subset) using both your in-house blocks and a large commercial library. A performance drop of around 12% is expected; a larger gap indicates an issue [18].

- Analyze Building Block Diversity: Check if your in-house collection lacks diversity in key chemical regions needed for your target candidates.

- Resolution Steps:

- Retrain a Custom Synthesizability Score: Train a rapid, CASP-based synthesizability score specifically on your in-house building blocks. A well-chosen dataset of 10,000 molecules can be sufficient for effective retraining, capturing your lab's specific synthesizability context without high computational cost [18].

- Strategic Building Block Acquisition: Use the failed candidates to identify frequently missing precursor structures and make targeted purchases to expand your in-house library.

Problem 2: Disagreement Between Synthesizability Score and Synthesis Planning

- Symptoms: A candidate receives a high synthesizability score from a learned model, but the CASP tool cannot find a synthesis route (or vice versa).

- Investigation Steps:

- Interrogate the Score's Basis: Determine if the score is compositional, structural, or CASP-based. A composition-only model might miss complex structural synthesis barriers [7].

- Check CASP Parameters: Review the synthesis planning configuration, including the maximum number of reaction steps and the allowed reaction types. Overly restrictive settings can cause false negatives.

- Resolution Steps:

- Implement a Rank-Average Ensemble: Combine the strengths of different models. Use both a general/compositional score and a CASP-based score, then aggregate their outputs using a rank-average to create a more robust priority list [7].

- Manual Route Inspection: For critical high-score candidates that CASP fails on, engage an experienced medicinal chemist to manually evaluate potential retrosynthetic pathways that the AI might have missed.

Problem 3: Successfully Synthesized Compound Lacks Desired Activity

- Symptoms: A candidate, ranked highly for both synthesizability and predicted activity (e.g., via a QSAR model), is successfully made but shows no biochemical efficacy in testing.

- Investigation Steps:

- Verify Compound Purity and Structure: Confirm via analytical methods (e.g., NMR, LC-MS) that the synthesized compound is the intended structure and is pure.

- Re-evaluate the Activity Model: Scrutinize the predictive model used for the biological activity. Was it trained on sufficiently diverse and relevant data? Does the candidate fall outside the model's applicability domain?

- Resolution Steps:

- Adopt Multi-Objective Optimization: Integrate synthesizability and activity predictions into a unified, multi-objective de novo design workflow. This ensures the generative AI creates structures that balance both synthesizability and potency from the outset, rather than just filtering for them post-generation [18].

- Analyze the Broader Candidate Space: Examine other highly-ranked candidates from your generation run. They may reveal alternative, active scaffolds with similar synthesizability that can provide new ligand ideas for your target [18].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Synthesis Planning Performance

This table summarizes the performance of synthesis planning when using a large commercial building block library versus a limited in-house collection, adapted from a real-world case study [18].

| Building Block Set | Number of Building Blocks | Solvability Rate (Caspyrus Centroids) | Average Shortest Synthesis Route (Steps) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial (Zinc) | 17.4 million | ~70% | Shorter by ~2 steps |

| In-House (Led3) | 5,955 | ~60% | Longer by ~2 steps |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validating Synthesizability

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) Tool (e.g., AiZynthFinder) | An open-source toolkit that performs retrosynthetic analysis to deconstruct target molecules into available building blocks and proposes viable synthesis routes [18]. |

| In-House Building Block Collection | A curated, digitally cataloged inventory of chemical precursors physically available in your laboratory. This is the fundamental constraint for defining in-house synthesizability [18]. |

| Synthesizability Prediction Model | A machine learning model (e.g., a graph neural network for structures, transformer for compositions) that outputs a score estimating synthesis probability. An ensemble model combining both is state-of-the-art [7]. |

| High-Throughput Synthesis Laboratory | An automated lab setup (e.g., with a robotic muffle furnace) that allows for the parallel synthesis of multiple candidates based on AI-predicted recipes, drastically speeding up validation [7]. |

| Characterization Equipment (e.g., XRD) | X-ray Diffraction is used to verify that the synthesized product's crystal structure matches the computationally predicted target structure [7]. |

Protocol: Experimental Validation of Synthesizability Predictions

This protocol outlines the key steps for a synthesizability-guided discovery pipeline, integrating elements from both drug and materials discovery [18] [7].

- Candidate Pool Generation: Start with a large, computationally generated pool of candidate molecules or materials (e.g., from a de novo design algorithm or a massive database like GNoME).

- Synthesizability Scoring & Ranking:

- Apply your synthesizability model(s) to the entire candidate pool.

- Use a rank-average ensemble to combine scores from different models (e.g., compositional and structural) into a single, robust ranking.

- Apply filters (e.g., exclude toxic elements, focus on oxides) to narrow the list to a few hundred high-priority candidates.

- Synthesis Planning: For the top-ranked candidates, use a CASP tool to generate specific synthesis routes using your in-house or readily available building blocks.

- Experimental Synthesis: Execute the suggested synthesis routes in the lab. A high-throughput, automated platform is ideal for testing multiple candidates in parallel.

- Characterization & Validation: Analyze the synthesized products using techniques like XRD, NMR, or mass spectrometry to confirm the identity and purity of the target compound.

- Feedback Loop: Use the experimental results (successes and failures) to retrain and improve your synthesizability models, creating a continuous learning cycle.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Synthesizability-Guided Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Architecture of a Unified Synthesizability Model

This diagram details the architecture of a state-of-the-art synthesizability model that integrates both compositional and structural information [7].

This technical support guide outlines the experimental validation of a computational pipeline designed for the rapid identification and synthesis of structural analogs of known drugs [19] [20]. The overarching thesis of this research is to bridge the gap between in silico predictions of synthesizability and experimental confirmation, thereby accelerating drug development [21]. The process involves several key stages: diversification of a parent molecule to create analogs, retrosynthetic analysis to identify substrates, forward-synthesis guided towards the parent, and finally, experimental evaluation of binding affinity and medicinal-chemical properties [20].

The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and protocols are designed to support researchers in experimentally validating such computational predictions, using the documented case studies of Ketoprofen and Donepezil analogs as a foundation [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: The synthesis of my computer-designed analog failed. What are the primary causes? Synthesis failure can often be attributed to the accuracy of the initial retrosynthetic analysis.

- Cause: The retrosynthetic algorithm may have suggested a disconnection that is theoretically valid but practically low-yielding or incompatible with other functional groups in the molecule.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the proposed route manually. Consider using alternative starting materials identified through the "replica" method, where substructure replacements are made to the parent before retrosynthesis to ensure starting materials retain mutual reactivity [20]. Furthermore, employ a synthetic feasibility score (e.g., FSscore) that can be fine-tuned with human expert feedback to rank the synthesizability of proposed analogs before committing to experimental work [22].

FAQ 2: My compound showed poor binding affinity despite favorable computational docking. Why? This is a common challenge, as binding affinity predictions may only be accurate to within an order of magnitude [19] [20].

- Cause: Docking programs primarily predict the binding mode and provide a rough estimate of affinity. They may struggle to accurately calculate solvation effects, entropy, or subtle protein flexibility [20].

- Solution: Use docking scores as a tool for initial prioritization and to discern promising binders from inadequate ones, but do not rely on them to discriminate between moderate (μM) and high-affinity (nM) binders. Always plan for experimental validation [19]. Ensure your docking protocol includes multiple runs and cross-validation with different software where possible.

FAQ 3: I am observing high background noise or non-specific binding (NSB) in my binding assay (e.g., ELISA). What should I check? High background is frequently caused by contamination or improper washing [23].

- Causes and Solutions:

- Contamination: The assays are extremely sensitive. Avoid performing assays in areas where concentrated forms of the analyte (e.g., cell culture media, sera) are handled. Use dedicated, clean pipettes and aerosol barrier tips. Do not use plate washers that have been previously exposed to concentrated analyte solutions [23].

- Incomplete Washing: Ensure the microtiter wells are washed thoroughly according to the kit's protocol. Incomplete washing can lead to carryover of unbound reagent [23].

- Reagent Contamination: If using an alkaline phosphatase-based system (e.g., with PNPP substrate), environmental contaminants can cause high background. Only withdraw the substrate needed for the immediate assay and do not return unused portions to the stock bottle [23].

FAQ 4: My dose-response curve has a poor fit, making IC50/EC50 determination unreliable. How can I improve data analysis? The choice of curve-fitting algorithm is critical for immunoassays and binding data [23].

- Solution: Avoid using simple linear regression, as most bioassays are inherently non-linear. Instead, use robust fitting routines such as Point-to-Point, Cubic Spline, or 4-Parameter Logistic (4PL) regression [23]. To validate your chosen method, "back-fit" your standard curve data as unknowns; the algorithm should recover the nominal values of the standards accurately.

FAQ 5: How can I assess the robustness of my bioassay beyond the size of the assay window? The Z'-factor is a key metric that considers both the assay window and the data variability [24].

- Implementation: The Z'-factor is calculated using the formula:

Z' = 1 - [ (3 * SD_high + 3 * SD_low) / |Mean_high - Mean_low| ]whereSD_highandSD_loware the standard deviations of the high (e.g., maximum signal) and low (e.g., minimum signal) controls, andMean_highandMean_loware their respective mean signals. A Z'-factor > 0.5 is generally considered indicative of a robust assay suitable for screening [24].

Quantitative Data from Validated Case Studies

The following tables summarize the key experimental outcomes from the referenced study, providing a benchmark for successful validation.

Table 1: Experimental Validation of Computer-Designed Syntheses

| Parent Drug | Number of Analogs Proposed for Synthesis | Number of Successful Syntheses | Synthesis Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoprofen | 7 | 7 | 100% |

| Donepezil | 6 | 5 | 83% |

| Total | 13 | 12 | 92% |

Table 2: Experimental Binding Affinity of Validated Analogs

| Parent Drug | Target Protein | Parent Drug Binding Affinity | Best Analog Binding Affinity | Potency of Best Analog vs. Parent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoprofen | COX-2 | 0.69 μM | 0.61 μM | Slightly more potent |

| Donepezil | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | 21 nM | 36 nM | Slightly less potent |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Computational Analog Design and Synthesis Workflow

This protocol describes the core pipeline used to generate and validate the Ketoprofen and Donepezil analogs [20].

- Diversification: Start with the parent molecule. Perform in silico substructure replacements aimed at enhancing biological activity. These replacements can target peripheral groups or internal motifs (e.g., 1,3-disubstituted benzene rings, piperazines).

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Subject the generated "replica" molecules to a retrosynthetic algorithm (e.g., Allchemy) to identify potential substrates.

- Substrate Curation: Augment the set of identified substrates with a small, static set of synthetically versatile "auxiliary" chemicals (e.g., NBS for bromination, bis(pinacolato)diboron for Suzuki couplings, mesyl chloride for activation) to enable a wider range of forward-synthesis reactions.

- Guided Forward-Synthesis:

- Generation 0 (G0): Begin with the curated substrates.

- Network Expansion: Apply a knowledge base of reaction transforms iteratively. To guide the network towards parent-like molecules, in each generation, retain only a pre-determined number (beam width, W) of products that are most structurally similar to the parent.

- Cross-Generation Reactivity: After 1-2 generations, restrict reactions so that molecules in generation Gi can only react with species from earlier generations (G0 to Gi-1) to prevent combinatorial explosion.

- Synthesis Validation: Execute the top-ranked, computer-proposed synthetic routes in the laboratory using standard organic synthesis techniques.

Protocol: Measuring Binding Affinity via a TR-FRET Assay

This is a generalized protocol for binding assays, common in drug discovery [24].

- Plate Setup: Prepare a dilution series of the test compound in a low-volume, white assay plate. Include controls (high signal without inhibitor, low signal with a known potent inhibitor).

- Reaction Assembly:

- Add the target protein (e.g., enzyme) to the wells.

- Add the TR-FRET detection reagents. This typically includes a terbium (Tb)- or europium (Eu)-labeled donor antibody and a fluorescently-labeled acceptor tracer that binds to the target site.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate in the dark to allow the binding reaction to reach equilibrium.

- Reading the Plate: Use a compatible microplate reader with time-resolved (TR) detection and the correct emission filters. For a Tb donor, standard filters are 520 nm (acceptor) and 495 nm (donor).

- Data Analysis:

- For each well, calculate the emission ratio (Acceptor Signal / Donor Signal).

- Plot the emission ratio against the logarithm of the compound concentration.

- Fit the data using a 4-parameter logistic model to determine the IC50 value.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for validating structural analogs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Analog Synthesis & Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetically Versatile Auxiliaries | Enables key reactions in forward-synthesis networks [20] | NBS (electrophilic halogenation), Bis(pinacolato)diboron (Suzuki coupling), Mesyl chloride (alcohol activation). |

| TR-FRET Detection Kit | Measures binding affinity in a homogeneous, high-throughput format [24] | Includes LanthaScreen Eu- or Tb-labeled donor and fluorescent acceptor tracer. |

| Assay-Specific Diluent | Diluting samples for binding assays without introducing matrix effects [23] | Formulated to match the standard curve matrix; prevents analyte adsorption and ensures accurate recovery. |

| Synthetic Feasibility Score (ML-based) | Computational prioritization of analogs based on predicted ease of synthesis [22] | e.g., FSscore; can be fine-tuned with expert feedback for specific chemical spaces (e.g., PROTACs, natural products). |

The discovery of new inorganic crystals is a fundamental driver of innovation in energy storage, catalysis, and electronics. [25] Traditional materials discovery, reliant on experimentation and intuition, has long iteration cycles and limits the number of testable candidates. [25] High-throughput computational screening and generative models have dramatically accelerated the identification of promising hypothetical materials. [26] However, a significant challenge remains: bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization. [27]

This case study establishes a technical support framework for researchers navigating this critical transition. It provides detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and resource information specifically designed to help validate the synthesizability of computationally predicted inorganic crystals, with a particular focus on materials generated by advanced models like MatterGen. [25] [28]

Computational Prediction: Frameworks and Validation

State-of-the-Art Generative Models

The field has moved beyond simple screening to the inverse design of materials using generative models. A leading model, MatterGen, is a diffusion-based generative model designed to create stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table. [25]

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the MatterGen Generative Model for Crystal Prediction [25] [28]

| Metric | Performance | Evaluation Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stability Rate | 78% of generated structures | Energy within 0.1 eV/atom above the convex hull (Materials Project reference) |

| Structural Quality | 95% of structures have RMSD < 0.076 Å | RMSD between generated and DFT-relaxed structures |

| Novelty & Diversity | 61% of generated structures are new | Not matching any structure in the combined Alex-MP-ICSD dataset (850k+ structures) |

| Success Rate (SUN) | More than double previous models | Percentage of Stable, Unique, and New (SUN) materials generated |

Validating Predictions Before Synthesis

Before committing to laboratory synthesis, a rigorous computational validation protocol is essential to prioritize the most promising candidates and avoid wasted resources.

Diagram 1: Computational validation workflow for predicted crystals.

The workflow involves several critical steps, each with a specific methodology:

Initial Pre-screening with Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs): Universal Interatomic Potentials (UIPs) have advanced sufficiently to act as effective and cheap pre-filters for thermodynamic stability before running more computationally expensive Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. [27] This step rapidly eliminates clearly unstable configurations.

DFT Relaxation and Stability Assessment: Candidates passing the initial screen undergo full relaxation using DFT, the computational workhorse of materials science. [27] [26] The key metric for stability is the energy above the convex hull, which quantifies a material's energetic competition with other phases in the same chemical system. A structure is typically considered potentially stable if this value is below 0.1 eV per atom. [25] [27] It is crucial to note that a low formation energy alone does not directly indicate thermodynamic stability; the convex hull distance is the more relevant metric. [27]

Prototype Search and Novelty Check: Finally, stable predicted structures should be compared against extensive crystallographic databases (e.g., ICSD, Materials Project) using structure-matching algorithms to confirm their novelty. [25] This ensures that effort is not spent "re-discovering" known materials.

High-Throughput Synthesis and Experimental Validation

Synthesis Workflow for Novel Inorganics

Once a candidate is computationally validated, it proceeds to the laboratory synthesis phase. A generalized workflow for high-throughput synthesis is outlined below.

Diagram 2: High-throughput synthesis and validation loop.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A high-throughput synthesis lab requires specialized reagents and equipment to efficiently process and characterize multiple candidates.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Synthesis

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Elemental Precursors | Starting materials for solid-state reactions; purity is critical to avoid impurity phases. |

| Solvents (e.g., Water, Ethanol) | Medium for solution-based synthesis methods and precursor mixing. |

| Flux Agents (e.g., Molten Salts) | Lower synthesis temperature and improve crystal growth by providing a liquid medium. |

| Pellet Press Die | To form powdered precursors into dense pellets for solid-state reactions. |

| High-Temperature Furnaces | For annealing, sintering, and solid-state reactions (up to 1600°C+). |

| Controlled Atmosphere Glovebox | For handling air-sensitive precursors (e.g., alkali metals, sulfides). |

| Automated Liquid Handling Robots | To precisely dispense solution precursors for high-throughput experimentation. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: The computational model predicted a stable crystal, but my synthesis attempt resulted in an amorphous powder or a mixture of phases. What went wrong? A1: This is a common challenge. Computational stability represents a thermodynamic ground state, but synthesis is governed by kinetics. The predicted phase might not be the one with the lowest energy barrier to formation. Consider:

- Refining Synthesis Parameters: Systematically vary the annealing temperature, duration, and cooling rate.

- Using a Flux: A flux agent can lower the energy barrier to crystallization and promote the growth of the target phase. [25]

- Alternative Synthesis Routes: Try a different method (e.g., solution precipitation instead of solid-state reaction) that might provide a more direct kinetic pathway.

Q2: My X-ray Diffraction (XRD) pattern matches the predicted structure, but the measured property (e.g., band gap, conductivity) is significantly off. Why? A2: Small defects, impurities, or non-stoichiometry that are not fatal to the overall structure can drastically alter electronic properties.

- Verify Sample Purity: Use techniques like energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to check composition and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to look for secondary phases.

- Check for Defects: Characterize for oxygen vacancies or cation non-stoichiometry, which are common in inorganic crystals.

- Understand Model Limits: Remember that the model's property prediction is based on an ideal, perfect crystal, which is rarely achieved experimentally.

Q3: How reliable are machine learning predictions for entirely new chemical systems not well-represented in training data? A3: This is a key limitation. ML models excel at interpolation but can struggle with extrapolation. [27] The Matbench Discovery framework highlights that accurate regressors can still produce high false-positive rates near decision boundaries. [27] Always treat ML predictions as a powerful pre-screening tool, not a final verdict. DFT validation remains a crucial step before synthesis for novel systems. [27]

Q4: We successfully synthesized a new stable material. How can we contribute back to the community? A4: To close the loop and improve future predictive models, you can:

- Deposit the Structure: Submit your final, refined crystal structure to public databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Share Raw Data: Publish synthesis protocols, XRD patterns, and property measurements.

- Contribute to Databases: Add your calculated DFT formation energy and relaxed structure to open computational databases like the Materials Project. This provides crucial data for re-training and improving generative models. [25]

Advanced Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Advanced Synthesis Issues and Resolution Strategies

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistently Amorphous Products | Insufficient thermal energy for crystallization; kinetic barriers too high. | TGA/DSC to identify crystallization temperature. | Increase annealing temperature/time; use a flux; apply high pressure. |

| Persistent Impurity Phases | Incorrect precursor stoichiometry; local inhomogeneity. | SEM/EDS to map elemental distribution. | Improve precursor mixing (e.g., ball milling); re-calculate and verify stoichiometry. |

| Low Density or Porous Sintered Pellets | Incomplete sintering; insufficient pressure during pressing. | Measure bulk density; SEM for microstructure. | Increase sintering temperature/pressure; use sintering aids. |

| Failed Reproduction of a Published Synthesis | Unreported critical parameters (e.g., cooling rate, atmosphere). | Carefully review literature for subtle details. | Systematically explore parameter space (cooling rates, gas environment) using high-throughput methods. |

The high-throughput synthesis of predicted inorganic crystals represents a paradigm shift in materials discovery. By integrating robust computational validation (Diagram 1) with systematic experimental workflows (Diagram 2) and a structured troubleshooting framework (FAQs and Table 3), researchers can significantly increase the success rate of translating digital designs into physical reality. This end-to-end process, from generative model to characterized crystal, as demonstrated with systems like MatterGen, is forging a faster, more efficient path to the next generation of functional materials. The key to success lies in treating computation and experiment as interconnected partners, where each failed synthesis provides data to refine the next cycle of prediction.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is the primary information XRD provides to confirm a successful synthesis? XRD is used to identify and quantify the crystalline phases present in a synthesized material. By comparing the measured diffraction pattern to databases of known materials, researchers can confirm that the target compound has been formed and identify unwanted impurity phases [29]. The position of the diffraction peaks confirms the crystal structure and lattice parameters, while the intensity of the peaks provides information on the arrangement of atoms within the unit cell [29].

Q2: My binding affinity assay shows inconsistent results between replicates. What are the most common causes? Poor reproducibility in binding assays often stems from three main issues [30] [31]:

- Reagent Quality and Consistency: Degradation or aggregation of the target or ligand can alter apparent affinity. Use high-quality reagents with minimal batch-to-batch variability [32] [31].

- Pipetting Errors: Inaccurate serial dilutions are a major source of variability. Employing automated liquid handling can significantly improve repeatability [32].

- Non-Equilibrium Conditions: If the binding reaction has not reached equilibrium before measurement, the calculated Kd will be inaccurate. The time required for equilibrium depends on the dissociation rate constant (koff) and ligand concentration, and can require extended incubation times for high-affinity interactions [30] [33].

Q3: How can I determine if a low Kd value from my assay reflects true high affinity or is an experimental artifact? A low (high-affinity) Kd should be validated by ensuring key experimental conditions are met [30] [33]:

- Confirm Equilibrium: The reaction must reach equilibrium before measurement. The time to equilibrium can be estimated using the equation involving koff and ligand concentration [30].

- Avoid Ligand Depletion: The concentration of free ligand should not be significantly depleted by binding. This is ensured by using a receptor concentration much lower than the Kd ([R]T << Kd) [30].

- Use a Sensitive, Quantitative Assay: The detection method must be proportional to the concentration of the bound complex and should not disturb the equilibrium, as occurs in wash steps [33].

Q4: Why is my XRD pattern for a supposedly pure sample showing extra, unidentified peaks? Unidentified peaks typically indicate the presence of crystalline impurity phases or an incomplete reaction where starting materials remain [29]. To troubleshoot:

- Consult Reference Databases: Compare your pattern against extensive databases like the ICDD to identify the impurity [29].

- Refine Synthesis Parameters: The presence of impurities often points to suboptimal synthesis conditions, such as incorrect temperature, pressure, or precursor ratios. The synthesis process may need optimization to drive the reaction to completion [7].

Q5: Within a thesis on synthesizability, how do XRD and binding assays complement each other? These techniques validate different aspects of the discovery pipeline for new materials or drugs [7] [34]:

- XRD confirms successful synthesis by verifying that the predicted material has been correctly formed as a crystalline solid with the intended atomic structure [7] [29].

- Binding Affinity Assays confirm successful function by quantifying how effectively the synthesized molecule interacts with its intended biological target, a key parameter for therapeutic or diagnostic utility [30] [32]. Together, they provide a complete picture from computational prediction to structural and functional validation [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting XRD Characterization

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Broad or low-intensity peaks | Very small crystallite size, presence of amorphous material [29] | Optimize synthesis to promote crystal growth (e.g., adjust cooling rate, annealing) [29] |

| High background noise | Fluorescence from the sample, poor sample preparation [29] | Use appropriate X-ray filters, ensure flat and uniform sample mounting [29] |

| Peak shifting | Residual stress or strain in the material, compositional variation [29] | Perform post-synthesis annealing to relieve stress, verify stoichiometry of precursors [29] |

| Unidentified peaks | Impurity phases, incomplete reaction, incorrect phase prediction [7] [29] | Cross-reference with structural databases (ICSD, Materials Project), refine synthesis parameters [7] [29] |

| Poor quantification results | Preferred orientation in the sample, inadequate calibration [29] | Use a rotating sample holder, prepare samples carefully to avoid texture, use certified standards [29] |

Troubleshooting Binding Affinity Assays

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor reproducibility | Pipetting errors, reagent instability, non-equilibrium conditions [30] [32] [31] | Use automated liquid handling, aliquot and quality-control reagents, confirm equilibrium time [30] [32] |

| High background signal | Non-specific binding of the ligand [32] [31] | Optimize blocking agents (e.g., BSA, casein), include detergent in buffers, wash more stringently [31] |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | Low affinity reagents, ligand or target degradation, suboptimal detection settings [31] | Use high-affinity monoclonal antibodies, check reagent integrity (e.g., via size analysis), optimize detector gain [32] [31] |

| Sigmoidal curve not achieved | Concentration range too narrow, incorrect model fitting [30] [33] | Ensure ligand concentrations span several orders of magnitude around the expected Kd, use appropriate fitting models (e.g., 4PL) [30] [31] |

| Evidence of ligand depletion | Receptor concentration too high ([R]T > Kd) [30] | Lower the concentration of receptor in the assay to ensure [R]T << Kd [30] [33] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative Phase Analysis of a Solid Material via XRD

This protocol is used to identify and quantify the crystalline phases in a solid sample, which is critical for confirming the success of a synthesis and detecting impurities [29].

Workflow Overview

Materials and Reagents

- Synthesized Powder Sample: The material to be characterized.

- Flat XRD Sample Holder: Typically made of glass or silicon.

- Standard Reference Material: (Optional) For instrument calibration, such as NIST SRM 674b.

- Mortar and Pestle or McCrone Mill: For reducing particle size.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Gently grind the sample to a fine powder (ideally <10 µm) to minimize preferred orientation and ensure a random distribution of crystallites. Avoid over-grinding, which can induce strain [29].

- Loading: Pack the powder uniformly into the sample holder's cavity. Use a glass slide to create a flat, level surface flush with the holder's edge.

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample holder into the XRD diffractometer. Standard parameters for a routine scan might be:

- X-ray Source: Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å)

- Voltage/Current: 40 kV, 40 mA

- Scan Range (2θ): 5° to 80°

- Step Size: 0.02°

- Time per Step: 1-2 seconds [29]

- Data Collection: Initiate the scan. The instrument will rotate the sample and detector while measuring the intensity of diffracted X-rays.

- Data Analysis:

- Phase Identification: Compare the resulting diffraction pattern (peak positions and relative intensities) to reference patterns in databases like the ICDD PDF or Materials Project [7] [29].

- Quantification: For a mixture of phases, use quantitative methods like the Rietveld refinement, which fits the entire pattern to calculate the weight fraction of each crystalline phase present [29].

Protocol 2: Determining Ligand-Receptor Binding Affinity (Kd) via a Cell-Based Assay

This protocol outlines the steps to measure the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) for a ligand binding to its receptor expressed on the surface of live cells, providing a key functional metric [30].

Workflow Overview

Materials and Reagents

- Cells: Mammalian or yeast cells expressing the receptor of interest on their surface [30].

- Ligand: The purified soluble binding partner, which should be fluorescently labeled for detection [30].

- Binding Buffer: An appropriate physiological buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% BSA to reduce non-specific binding) [31].

- Flow Cytometer or Fluorescence Plate Reader: For quantifying bound ligand.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Prepare Cells: Harvest cells expressing the receptor, wash them, and resuspend in binding buffer at a defined concentration. Keep cells on ice to prevent internalization.

- Prepare Ligand Dilutions: Create a serial dilution of the labeled ligand in binding buffer. The concentration range should ideally span two orders of magnitude above and below the expected Kd [30] [33]. Include a negative control with no ligand.

- Incubate to Equilibrium: Combine a constant number of cells with each ligand dilution in separate tubes. Incubate the mixtures at a constant temperature (e.g., 4°C or 37°C) with gentle agitation for a time confirmed to be sufficient to reach equilibrium (this may require a pilot time-course experiment) [30] [33].

- Measure Bound Ligand:

- For methods without washing (ideal), directly analyze a small aliquot of the cell-ligand mixture by flow cytometry.

- If washing is necessary to remove unbound ligand, wash cells quickly and gently with ice-cold buffer to minimize dissociation of the complex during the process [33]. Then resuspend and analyze.

- Data Analysis:

- For each ligand concentration, calculate the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), which is proportional to the concentration of bound ligand [LR].

- Plot the measured [LR] (or normalized fraction of receptor bound) against the concentration of free ligand [L].

- Fit the data to the equilibrium binding equation (Eq. 8 from [30]) using non-linear regression: