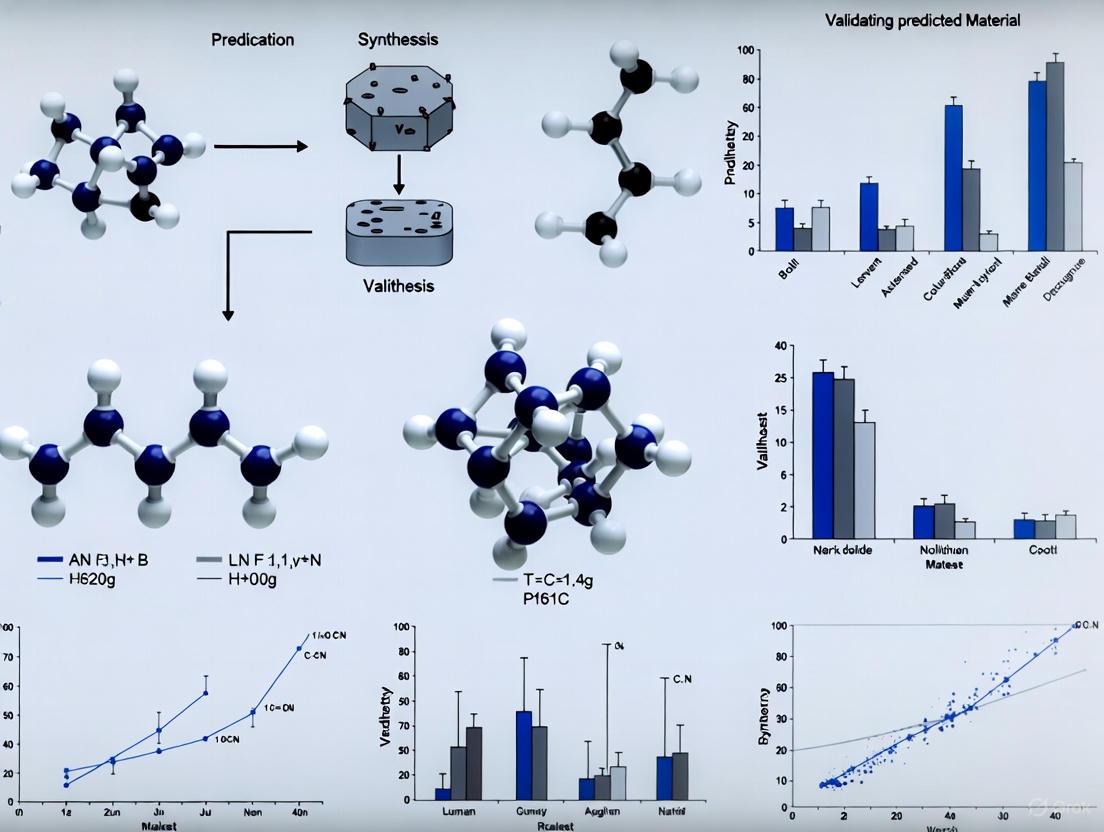

From Prediction to Lab: A Modern Guide to Validating Material Properties Through Synthesis

This article addresses the critical challenge of bridging the gap between computationally predicted materials and their successful synthesis in the laboratory.

From Prediction to Lab: A Modern Guide to Validating Material Properties Through Synthesis

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of bridging the gap between computationally predicted materials and their successful synthesis in the laboratory. Aimed at researchers and professionals in materials science and drug development, we explore the foundational limitations of traditional stability metrics, showcase cutting-edge AI models like CSLLM and SynthNN that predict synthesizability with over 98% accuracy, and detail robust methodological frameworks for experimental validation. By providing troubleshooting strategies for synthesis bottlenecks and comparative analyses of validation techniques, this guide serves as a comprehensive resource for accelerating the transition of theoretical discoveries into tangible, validated materials.

The Synthesis Bottleneck: Why Predicted Materials Often Fail in the Lab

The acceleration of computational materials discovery has created a significant bottleneck at the stage of experimental realization. While advanced algorithms can generate millions of candidate structures with promising properties, the crucial challenge lies in identifying which of these theoretically predicted materials can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory. This guide examines the critical distinction between thermodynamic stability—a long-standing cornerstone of computational materials screening—and practical synthesizability, an emerging field that incorporates kinetic, experimental, and pathway-dependent factors to better predict which materials can actually be made.

Defining the Concepts: Stability Versus Synthesizability

Thermodynamic Stability

Thermodynamic stability assesses a material's inherent stability at absolute zero temperature, typically determined through density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The most common metric is the energy above the convex hull (ΔEhull), which represents the energy difference between a compound and the most stable combination of other phases in its chemical space. Materials with ΔEhull = 0 eV/atom are considered thermodynamically stable, while those with positive values are metastable or unstable [1] [2].

This approach assumes that synthesizable materials will not have thermodynamically stable decomposition products. However, this method captures only approximately 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials, failing to account for kinetic stabilization and pathway-dependent synthesis outcomes [2].

Practical Synthesizability

Practical synthesizability represents a more comprehensive framework that evaluates whether a material can be experimentally realized using current laboratory methods. This incorporates not just thermodynamic factors but also kinetic barriers, precursor availability, reaction pathways, and experimental constraints [3] [4]. Synthesizability depends on finding a viable "pathway" to the target material, analogous to finding a mountain pass rather than attempting to climb directly over a peak [3].

The development of synthesizability prediction models represents a paradigm shift from "Is this structure stable?" to "Can this structure be made, and how?" [4].

Quantitative Comparison of Screening Methods

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of different screening approaches for identifying synthesizable materials, based on recent research findings:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Material Screening Methods

| Screening Method | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | Energy above convex hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% accuracy [1] | Fails for many metastable phases; ignores kinetic factors |

| Kinetic Stability | Lowest phonon frequency (≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% accuracy [1] | Computationally expensive; some synthesizable materials have imaginary frequencies |

| Charge Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge | 37% of known compounds are charge-balanced [2] | Overly restrictive; poor performance across diverse material classes |

| SynthNN (Composition-based) | Synthesizability classification | 7× higher precision than formation energy [2] | Lacks structural information |

| CSLLM Framework | Synthesizability accuracy | 98.6% accuracy [1] | Requires specialized training data |

| Unified Synthesizability Score | Experimental success rate | 7 of 16 targets synthesized (44%) [4] | Combines composition and structure |

The performance advantage of dedicated synthesizability models is evident across multiple studies. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework demonstrates particularly high accuracy (98.6%), significantly outperforming traditional stability-based screening methods [1]. Similarly, the SynthNN model identifies synthesizable materials with 7× higher precision than DFT-calculated formation energies [2].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

High-Throughput Experimental Validation

Recent research has established robust protocols for validating synthesizability predictions. One comprehensive pipeline screened approximately 4.4 million computational structures, applying a unified synthesizability score that integrated both compositional and structural descriptors [4]. The experimental workflow included:

- Candidate Prioritization: Selection of high-synthesizability candidates (rank-average > 0.95) excluding platinoid elements and toxic compounds

- Retrosynthetic Planning: Application of precursor-suggestion models (Retro-Rank-In) to generate viable solid-state precursors

- Condition Prediction: Use of models (SyntMTE) trained on literature-mined synthesis data to predict calcination temperatures

- Automated Synthesis: Execution of reactions in a high-throughput laboratory setting using a muffle furnace

- Characterization: Verification of products via X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm target phase formation

This pipeline successfully synthesized 7 out of 16 characterized targets, including one completely novel structure and one previously unreported phase [4].

Robotic Laboratory Validation

A separate approach validated synthesizability predictions using robotic inorganic materials synthesis. Researchers developed a novel precursor selection method based on phase diagram analysis and pairwise precursor reactions, then tested this approach across 224 reactions spanning 27 elements with 28 unique precursors targeting 35 oxide materials [5].

The robotic laboratory (Samsung ASTRAL) completed this extensive experimental matrix in weeks rather than the typical months or years, demonstrating that precursors selected with the new criteria produced higher yield of the targeted phase for 32 of the 35 materials compared to traditional precursors [5].

Computational Frameworks and Workflows

The emerging paradigm for synthesizability-aware materials discovery integrates multiple computational approaches, as illustrated in the following workflow:

Synthesizability Prediction Workflow: Integrating composition and structure-based screening with pathway planning.

Specialized Language Models for Synthesis

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework employs three specialized LLMs to address different aspects of the synthesis prediction problem [1]:

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure is synthesizable (98.6% accuracy)

- Method LLM: Classifies possible synthetic methods (solid-state or solution) with >90% accuracy

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable solid-state synthetic precursors for binary and ternary compounds with >90% accuracy

This framework utilizes a novel text representation called "material string" that efficiently encodes essential crystal information for LLM processing, integrating lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry information [1].

In-House Synthesizability Scoring

For drug discovery applications, researchers have developed in-house synthesizability scores that account for limited building block availability in small laboratory settings. This approach successfully transferred computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) from 17.4 million commercial building blocks to a constrained environment of approximately 6,000 in-house building blocks with only a 12% decrease in success rate, albeit with synthesis routes typically two steps longer [6].

When incorporated into a multi-objective de novo drug design workflow alongside quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, this synthesizability score facilitated the generation of thousands of potentially active and easily synthesizable candidate molecules [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Synthesizability Prediction

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework [1] | Predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors | General inorganic materials discovery |

| SynthNN [2] | Composition-based synthesizability classification | High-throughput screening of hypothetical compositions |

| AiZynthFinder [6] | Computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) | Retrosynthetic analysis for organic molecules and drugs |

| Unified Synthesizability Score [4] | Combined composition and structure scoring | Prioritization for experimental campaigns |

| Retro-Rank-In [4] | Precursor suggestion model | Solid-state synthesis planning |

| SyntMTE [4] | Synthesis condition prediction | Calcination temperature optimization |

The distinction between thermodynamic stability and practical synthesizability represents a critical evolution in computational materials science. While thermodynamic stability remains a valuable initial filter, dedicated synthesizability models that incorporate structural features, precursor availability, and reaction pathway analysis demonstrate significantly improved performance in identifying experimentally accessible materials. The integration of these approaches into materials discovery pipelines—complemented by high-throughput experimental validation—is accelerating the translation of theoretical predictions to synthetic realities. As synthesizability prediction capabilities continue to advance, researchers can increasingly focus experimental resources on candidates with the highest probability of successful realization, ultimately bridging the gap between computational design and laboratory synthesis.

In the field of computational materials science, formation energy and charge-balancing have long served as foundational proxies for predicting material stability and properties. These computational shortcuts allow researchers to screen thousands of candidate materials before committing resources to synthesis. However, as the demand for more complex and specialized materials grows, significant limitations in these traditional approaches have emerged. This guide objectively compares the performance of these traditional computational proxies against emerging hybrid and machine learning methods, focusing specifically on their effectiveness in predicting synthesizable materials with target properties.

The validation of computationally predicted materials through actual synthesis represents the critical bridge between theoretical promise and practical application. Within this context, we examine how overreliance on traditional proxies can lead to high rates of false positives and failed syntheses, while also exploring advanced methodologies that offer improved predictive accuracy and better alignment with experimental outcomes.

Performance Comparison: Traditional Proxies vs. Advanced Methods

Table 1: Comparative analysis of computational methods for predicting material properties.

| Method Category | Key Features | Accuracy Limitations | Computational Cost | Experimental Validation Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-local DFT with Traditional Proxies | Uses formation energy and charge-balancing as stability proxies; relies on a-posteriori corrections for band gap errors | Quantitative accuracy limited for defect energetics; struggles with charge delocalization errors; requires careful benchmarking [7] | Moderate to High (depending on system size) | Limited quantitative accuracy for defect properties; often requires correction schemes [7] |

| Hybrid Functional DFT | Mixes exact exchange with semi-local correlation; better band gap description | Considered "gold standard" but may require fine-tuning to experimental values [7] | High (3-5x more expensive than semi-local) | High accuracy; used as reference for benchmarking other methods [7] |

| ML-Guided Workflows (e.g., GNN/DFT Hybrid) | Combines graph neural networks with DFT; enables high-throughput screening of vast composition spaces | Limited by training data quality and domain specificity | Low for screening, High for validation | Successfully predicted Ta-substituted tungsten borides with experimentally confirmed increased hardness [8] |

| Physics-Informed Charge Equilibration Models (e.g., ACKS2) | Includes flexible atomic charges and potential fluctuations; improved charge distribution description | Computationally expensive to solve; may exhibit numerical instabilities in MD simulations [9] | Low to Moderate | Improved physical fidelity for charge distributions and polarizability compared to simple QEq models [9] |

Table 2: Performance benchmarks for defect property predictions (adapted from [7]).

| Property Type | Semi-local DFT with Proxies | Hybrid DFT (Gold Standard) | Qualitative Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Transition Levels | Limited quantitative accuracy; significant deviations from reference | High accuracy | Moderate to Poor |

| Formation Energies | Systematic errors due to band gap underestimation | Quantitative reliability | Poor for absolute values |

| Fermi Levels | Moderate qualitative agreement | High accuracy | Good for trends |

| Dopability Limits | Useful for screening applications | Reference standard | Fair for classification |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Benchmarking Defect Property Calculations

The performance data presented in Table 2 derives from rigorous benchmarking protocols [7]. The reference dataset consists of 245 hybrid functional calculations across 23 distinct materials, which serves as the "gold standard" for comparison. The benchmarking workflow involves:

- Automated Point Defect Calculation: Defect formation energies are computed using semi-local Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a-posteriori corrections within an automated workflow.

- Correction Schemes: Application of three different correction sets to address band gap errors and electrostatic interactions between periodic images.

- Property Extraction: Calculation of four key defect properties: thermodynamic transition levels, formation energies, Fermi levels, and dopability limits.

- Statistical Comparison: Qualitative and quantitative comparison against hybrid functional reference data using correlation analysis and classification accuracy metrics.

This protocol reveals that while traditional semi-local DFT with proxy-based corrections can provide useful qualitative trends for screening purposes, it shows limited quantitative accuracy for definitive property prediction [7].

Hybrid AI-DFT Validation Workflow

A more robust methodology that successfully bridges computational prediction and experimental validation combines graph neural networks (GNNs) with density functional theory (DFT) in an iterative workflow [8]. The protocol comprises distinct stages of computational prediction and experimental verification, illustrated in the diagram below.

Computational Prediction Phase:

- Data Preparation: Construction of a search space comprising over 375,000 inequivalent crystal structures for solid solutions, beginning with a supercell of the base crystal structure (e.g., WB₄.₂) [8].

- Model Training: Training geometric graph neural networks (GNNs) on DFT-derived properties from approximately 200 entries, followed by fine-tuning using the Allegro architecture [8].

- High-Throughput Screening: Using validated GNN models to screen for stable compositions, followed by DFT calculations of mechanical properties for the most promising predicted structures [8].

Experimental Validation Phase:

- Synthesis: Guided by theoretical predictions, synthesis of powder and ceramic samples using methods such as the vacuumless arc plasma technique [8].

- Characterization: Application of multiple characterization techniques including X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and structural analysis [8].

- Property Verification: Measurement of target properties (e.g., Vickers microhardness) to confirm predicted enhancements. In the case of Ta-substituted tungsten borides, this protocol verified a significant increase in hardness with increasing Ta content, confirming the theoretical predictions [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key computational and experimental reagents for advanced materials prediction and validation.

| Reagent/Solution | Category | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Computational Model | Learns patterns from materials data; predicts properties without full DFT calculations | High-throughput screening of composition spaces; identifying promising doping candidates [8] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Method | Calculates electronic structure and energetics of materials systems | Determining formation energies, electronic properties, and defect energetics [8] [7] |

| Hybrid Functionals | Computational Method | Mixes exact exchange with DFT functionals for improved accuracy | Gold standard for point defect calculations; benchmarking simpler methods [7] |

| Charge Equilibration Models (e.g., ACKS2) | Computational Method | Models charge transfer and polarization efficiently in large systems | Molecular dynamics simulations of charge-dependent phenomena [9] |

| Vacuumless Arc Plasma System | Synthesis Equipment | Enables rapid synthesis of predicted ceramic materials | Synthesizing metal borides and other high-temperature materials [8] |

| Vickers Microhardness Tester | Characterization Instrument | Measures mechanical hardness of synthesized materials | Validating predicted enhancements in mechanical properties [8] |

Limitations of Traditional Proxies: Key Evidence

Formation Energy Shortcomings

The limitations of formation energy as a standalone proxy are particularly evident in defect calculations using semi-local DFT. These methods suffer from a well-known underestimation of band gaps, which compounds for charged defects whose energy levels typically reside near band edges [7]. This fundamental electronic structure error propagates through subsequent predictions, limiting the quantitative accuracy of traditional formation energy calculations. While a-posteriori corrections can partially mitigate these issues, they remain an imperfect solution that cannot fully address the underlying physical inaccuracies.

Furthermore, traditional approaches struggle with charge delocalization errors that impact their ability to qualitatively describe charge localization around defects [7]. This affects the accuracy of formation energy calculations for charged systems and consequently impacts predictions of material stability and properties based on these proxies.

Charge-Balancing Challenges

Traditional charge equilibration (QEq) models, while computationally efficient, exhibit systematic physical limitations that affect their predictive value [9]. These models frequently produce unphysical fractional charges in isolated molecular fragments and demonstrate significant deviations from expected macroscopic polarizabilities in dielectric systems [9]. Such fundamental physical inaccuracies limit the reliability of traditional charge-balancing proxies, particularly for applications where high physical fidelity is required.

The computational implementation of traditional QEq approaches also presents challenges. Solving the system of linear equations required by these models becomes prohibitively expensive for large systems, necessitating iterative solvers that must be tightly converged to avoid introducing non-conservative forces and numerical errors that lead to instabilities and systematic energy drift in molecular dynamics simulations [9].

Emerging Solutions and Alternative Approaches

Advanced Charge Equilibration Frameworks

Next-generation charge equilibration models address many limitations of traditional proxies. The ACKS2 framework extends conventional QEq approaches by incorporating not only flexible atomic partial charges but also on-site potential fluctuations, which more accurately modulate the ease of charge transfer between atoms [9]. This extension provides more physically correct charge fragmentation and polarizability scaling, significantly improving the physical fidelity of charge distribution predictions.

To address computational limitations, shadow molecular dynamics approaches based on these advanced charge equilibration models have been developed [9]. These methods replace the exact potential with an approximate "shadow" potential that allows exact solutions to be computed directly without iterative solvers, thereby reducing computational cost and preventing error accumulation while maintaining close agreement with reference potentials.

Machine Learning Accelerated Discovery

The integration of machine learning with traditional computational methods creates powerful alternatives to standalone proxy-based approaches. The ME-AI (Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence) framework demonstrates how machine learning can leverage experimentally curated data to uncover quantitative descriptors that move beyond traditional proxies [10]. This approach combines human expertise with AI to identify patterns that correlate with target properties, creating more reliable prediction pipelines.

Hybrid AI-DFT workflows exemplify this paradigm shift, using GNNs to rapidly screen vast composition spaces (over 375,000 configurations) before applying higher-fidelity DFT calculations to only the most promising candidates [8]. This hierarchical approach maintains physical accuracy while dramatically reducing computational costs compared to traditional high-throughput methods reliant solely on DFT with simple proxies.

The limitations of traditional proxies like formation energy and charge-balancing present significant challenges for computational materials discovery, particularly as researchers target increasingly complex material systems. The evidence presented in this comparison guide demonstrates that while these proxies offer computational efficiency, they frequently lack the quantitative accuracy and physical fidelity required for reliable prediction of synthesizable materials.

The most promising paths forward involve multiscale validation frameworks that integrate computational predictions with experimental synthesis, and hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of machine learning, physical modeling, and experimental validation. These methodologies successfully address the limitations of traditional proxies while providing more reliable pathways to experimentally viable materials with target properties, ultimately accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation materials for energy, electronics, and other critical applications.

The process of materials discovery and drug development is fundamentally constrained by a critical data deficit. This deficit is characterized by a severe scarcity of two types of data: comprehensive reports on failed experiments and large-scale, standardized synthesis data. While predictive artificial intelligence (AI) models for material properties have advanced significantly, their validation is hampered by this lack of reliable, experimental ground truth. The absence of negative results (failed experiments) leads to repeated efforts and wasted resources, as researchers unknowingly pursue untenable synthesis paths. Simultaneously, the incompleteness of synthesis data prevents the rigorous validation of AI-predicted properties against real-world outcomes, creating a bottleneck in the development of high-performance materials and pharmaceuticals. This guide examines the current state of this data deficit, compares emerging solutions, and provides experimental protocols for validating AI predictions within this challenging landscape.

Quantifying the Data Deficit and Its Impact on AI

The reliability of AI-driven materials discovery is directly limited by the quality and completeness of the data on which it is trained. The following table summarizes the key challenges arising from the data deficit and their tangible impact on predictive modeling.

Table 1: Core Challenges of the Materials Data Deficit and Their Impact on AI

| Challenge | Description | Impact on AI/ML Models |

|---|---|---|

| Scarcity of Failed Data | Publication bias favors successful experiments, creating massively skewed datasets that lack information on unsuccessful synthesis routes or conditions [11]. | Models learn only from "positive" examples, losing the ability to predict feasibility or identify boundaries of synthesis, leading to unrealistic candidate suggestions [12]. |

| Discrepancy in Training Data | AI models are often trained on large-scale Density Functional Theory (DFT)-computed data, which can have significant discrepancies from experimental measurements [13]. | Models inherit the systematic errors of their training data, limiting their ultimate accuracy and creating a gap between predicted and experimentally-validated properties [13]. |

| Data Comparability Issues | Existing data from various human biomonitoring (HBM) and synthesis studies often lack harmonization in sampling, collection, and analytical methods [11]. | Inconsistent data formats and protocols complicate the creation of large, unified training sets, hindering model generalizability and performance [11]. |

| Model Collapse | A degenerative condition where successive generations of AI models are trained on data that increasingly includes AI-generated outputs [14]. | Leads to a feedback loop of degradation, causing a loss of diversity, factual accuracy, and overall quality in model predictions [14]. |

The error discrepancy between standard computational methods and reality is not merely theoretical. A 2022 study highlighted that DFT-computed formation energies in major databases like the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) and Materials Project (MP) have Mean Absolute Errors (MAE) of >0.076 eV/atom when compared to experimental measurements. In a landmark demonstration, an AI model leveraging transfer learning achieved an MAE of 0.064 eV/atom on an experimental test set, significantly outperforming DFT itself [13]. This shows that AI can bridge the accuracy gap, but only when effectively trained on and validated against high-quality experimental data.

Comparative Analysis of Emerging Data Solutions

To address the data deficit, several complementary approaches are being developed. The table below compares three key strategies, evaluating their primary function, advantages, and inherent limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Emerging Solutions for the Materials Data Deficit

| Solution | Primary Function | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data [14] [12] | Generates artificial data that mimics the statistical properties of real-world data. | - Solves data scarcity for rare events/defects [14].- Reduces costs associated with manual data annotation and collection [14] [12].- Enhances data privacy by avoiding use of real, sensitive information [14]. | - Risk of lacking realism and omitting subtle real-world nuances [12].- Difficult to validate accuracy and fidelity [12].- Can perpetuate biases present in the original, underlying real data [12]. |

| Harmonized Data Initiatives (e.g., HBM4EU) [11] | Coordinates and standardizes data collection procedures across studies and institutions. | - Improves data comparability and reliability [11].- Enables creation of larger, more robust datasets for analysis [11].- Systematically identifies and addresses data gaps [11]. | - Technically and administratively complex to establish and maintain [11].- Captures primarily "white literature," potentially missing unpublished studies (grey literature) [11]. |

| Curated Public Datasets (e.g., MatSyn25) [15] | Provides large-scale, structured datasets extracted from existing research literature. | - Offers a centralized, open resource for the research community [15].- Specifically designed to train and benchmark AI models for specialized tasks (e.g., synthesis prediction) [15]. | - Dependent on the quality and completeness of the source literature [15].- May still reflect publication bias, though to a lesser extent than manual curation. |

A critical practice when using these solutions, particularly synthetic data, is to combine them with a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) review process. Human oversight is essential for validating the quality and relevance of synthetic datasets and for identifying subtle biases or inaccuracies that AI models might miss, thereby preventing model drift or collapse [14].

Experimental Protocols for Validating AI Predictions

For researchers aiming to validate AI-predicted material properties, the following protocols provide a methodological foundation. These procedures emphasize the critical role of experimental data in closing the AI validation loop.

Protocol 1: Experimental Validation of Formation Energy Predictions

This protocol is designed to test the accuracy of an AI model predicting the formation energy of a crystalline material, a key property for determining stability [13].

1. Hypothesis: An AI model, trained via deep transfer learning on both DFT-computed and experimental datasets, can predict the formation energy of a novel crystalline material with a lower error (MAE < 0.07 eV/atom) compared to standard DFT computations.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- AI Model: A Deep Neural Network (DNN), such as IRNet, capable of processing both composition and crystal structure [13].

- Training Datasets: Source domain data from a large DFT database (e.g., OQMD, MP, JARVIS) and target domain data from a curated set of experimental formation energy measurements [13].

- Test Material: A candidate crystalline material with a known structure but excluded from training datasets.

- Characterization Equipment: Equipment for X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm crystal structure and a calorimeter for experimental measurement of formation enthalpy.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Model Training: Pre-train the DNN on the large DFT-computed source dataset. Subsequently, fine-tune the model parameters on the smaller, more accurate experimental dataset [13].

- Step 2 - AI Prediction: Input the crystal structure and composition of the test material into the fine-tuned model to obtain the predicted formation energy.

- Step 3 - Experimental Ground Truth: Synthesize the test material and measure its formation energy experimentally using calorimetry, ensuring phase purity with XRD.

- Step 4 - Comparison & Validation: Calculate the absolute error between the AI-predicted value and the experimentally measured value. Compare this error to the known discrepancy of a standard DFT computation for the same material.

4. Data Analysis: The model's performance is evaluated on a hold-out test set of experimental data. The primary metric is the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in eV/atom, which should be statistically lower than the MAE of DFT computations on the same test set [13].

Protocol 2: Reliability Assessment for Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol assesses not just the accuracy, but the reliability of a property prediction for a novel molecule, which is crucial for prioritizing candidates for synthesis [16].

1. Hypothesis: A property prediction model that uses a molecular similarity-based framework can provide a quantitative Reliability Index (R) that correlates with prediction accuracy, allowing for high-confidence screening of molecular candidates.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Property Model: A foundational model such as a Group Contribution (GC) method, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), or Support Vector Regression (SVR) [16].

- Similarity Framework: A defined molecular similarity coefficient (e.g., based on Jaccard similarity or molecular structure descriptors) to select a tailored training set [16].

- Database: A existing compound property database (e.g., for refrigerants, solvents).

- Test Molecule: A novel molecule not present in the database.

- Experimental Setup: Apparatus suitable for measuring the target property (e.g., critical temperature, solubility parameter).

3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Similarity Calculation: Compute the molecular similarity between the target molecule and all molecules in the existing property database [16].

- Step 2 - Tailored Training: Select the most similar molecules from the database to form a custom, relevance-weighted training set for the property model [16].

- Step 3 - Prediction & Reliability Index: Use the tailored model to predict the property for the target molecule. Calculate the Reliability Index (R) based on the similarities of the molecules in the training set [16].

- Step 4 - Experimental Validation: Synthesize or source the test molecule and measure its property experimentally.

- Step 5 - Correlation Analysis: Analyze the correlation between the predicted Reliability Index (R) and the absolute prediction error.

4. Data Analysis: The framework's success is measured by a strong inverse correlation between the Reliability Index (R) and the observed prediction error. Molecules with a high R value should show significantly lower prediction errors, providing a trustworthy metric for molecular screening [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental validation of AI predictions requires a suite of reliable tools and data resources. The following table details key solutions essential for this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI Validation in Materials Science

| Tool / Solution | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| MatSyn25 Dataset [15] | A large-scale, open dataset of 2D material synthesis processes for training and benchmarking AI models. | - Contains 163,240 synthesis entries from 85,160 articles.- Provides basic material info and detailed synthesis steps.- Aims to bridge the gap between theoretical design and reliable synthesis. |

| Synthetic Data Platforms [14] | Generates artificial data to augment training sets for AI models, particularly for rare events or privacy-sensitive data. | - Reduces manual annotation costs.- Generates edge cases (e.g., rare material defects).- Often integrated with MLOps workflows for continuous model retraining. |

| Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Review [14] | A workflow that incorporates human expertise to validate and correct AI-generated outputs, such as synthetic data or model predictions. | - Prevents model collapse by maintaining ground-truth integrity.- Identifies subtle biases and inaccuracies AI may miss.- Often used in an "Active Learning" loop to iteratively improve models. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Databases (e.g., OQMD, MP) [13] | Large repositories of computationally derived material properties, serving as a primary source for pre-training AI models. | - Provide data on 10^4 to 10^6 materials.- Contain both experimentally-observed and hypothetical compounds.- Inherent discrepancy with experiment is a key limitation. |

| Molecular Similarity Framework [16] | A methodology to quantify the structural similarity between molecules, used to build reliable, tailored property models. | - Enables creation of custom training sets for target molecules.- Provides a quantitative Reliability Index (R) for predictions.- Helps prioritize molecules for experimental testing. |

The discovery of new functional materials and bioactive compounds is increasingly powered by sophisticated computational screens that can virtually explore thousands of candidates in silico. However, a significant validation gap persists between these computational predictions and their confirmation through laboratory experimentation. This gap represents the disconnect that occurs when computationally identified candidates fail to demonstrate their predicted properties under real-world experimental conditions. Bridging this gap requires a systematic approach to validation, ensuring that predictions from virtual screens translate reliably into synthesized materials with verified characteristics [17].

The stakes for closing this validation gap are substantial, particularly in fields like drug development and energy materials where the cost of false leads is high. While computational methods have dramatically accelerated the initial discovery phase, experimental validation remains the irreplaceable cornerstone of confirmation, providing the empirical evidence necessary to advance candidates toward application [18] [17]. This guide examines the methodologies, performance characteristics, and practical frameworks essential for navigating the critical path from computational prediction to laboratory-confirmed material properties.

Understanding the Validation Gap in Materials Science

Conceptual and Technical Origins

The validation gap emerges from several fundamental challenges in matching computational predictions with experimental outcomes. Computationally, limitations often arise from inaccurate force fields in molecular dynamics simulations, approximate density functionals in quantum chemical calculations, or incomplete feature representation in machine learning models [19]. For instance, a systematic evaluation of computational methods for predicting redox potentials in quinone-based electroactive compounds revealed that even different DFT functionals yield varying levels of prediction accuracy, with errors potentially exceeding practical acceptable thresholds for energy storage applications [19].

Experimentally, the gap can manifest through irreproducible synthesis pathways, unaccounted for environmental factors during testing, or discrepancies between idealized computational models and complex real-world systems. In omics-based test development, this has led to stringent recommendations that both the data-generating assay and the fully specified computational procedures must be locked down and validated before use in clinical trials [20]. Similarly, in materials science, a model trained solely on square-net topological semimetal data was surprisingly able to correctly classify topological insulators in rocksalt structures, demonstrating that transferability across material classes is possible but often unpredictable without explicit validation [10].

Impact on Research and Development

The consequences of an unaddressed validation gap are particularly pronounced in drug discovery and materials development pipelines. In pharmaceutical research, insufficient validation can lead to late-stage failures where compounds showing promising computational profiles ultimately prove ineffective or unsafe in biological systems. This discrepancy often stems from the limitations of static binding models that fail to capture dynamic physiological conditions, off-target effects, or complex metabolic pathways [18] [17].

For energy materials, the gap may appear as promising computational candidates that cannot be synthesized with sufficient purity, stability, or scalability. Studies on quinone-based electroactive compounds for energy storage reveal how computational predictions must account for synthetic accessibility, degradation pathways, and performance under operational conditions—factors often omitted from initial virtual screens [19]. The resulting inefficiencies prolong development timelines and increase costs, emphasizing the need for robust validation frameworks integrated throughout the discovery process.

Comparative Performance of Computational Screening Methods

Methodologies and Theoretical Foundations

Virtual screening employs diverse computational approaches to identify promising candidates from large chemical libraries. The most established methods include:

Molecular Docking: A structure-based approach that predicts the binding orientation and affinity of small molecules to target macromolecules. It requires 3D structural information of the target (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or homology modeling) and involves sampling possible ligand conformations and positions within the binding site, scored using empirical or knowledge-based functions [18].

Pharmacophore Modeling: A ligand-based method that identifies the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition. According to IUPAC, "a pharmacophore is the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [18].

Shape-Based Similarity Screening: Compares molecules based on their three-dimensional shape and electrostatic properties. The Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures (ROCS) algorithm is a prominent example that can be optimized by incorporating chemical information alongside shape characteristics [18].

Machine Learning Approaches: These include both supervised learning for property prediction and generative models for novel compound design. Recent advances incorporate physically grounded descriptors like electronic charge density, which shows promise for universal material property prediction due to its fundamental relationship with material behavior through the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem [21].

Prospective Performance Evaluation

Comparative studies provide critical insights into the relative strengths and limitations of different virtual screening methods. A prospective evaluation of common virtual screening tools investigated their performance in identifying cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors, with biological activity confirmed through in vitro testing [18].

Table 1: Prospective Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods

| Method | Representative Tool | Key Principles | Reported Advantages | Identified Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout | Steric/electronic feature mapping | High interpretability; Enables scaffold hopping | Limited to known pharmacophores; Sensitivity to model construction |

| Shape-Based Screening | ROCS | Molecular shape/electrostatic similarity | Does not require structural target data | Dependent on query compound quality; May overlook key interactions |

| Molecular Docking | GOLD | Binding pose prediction and scoring | Explicit modeling of protein-ligand interactions | Scoring function inaccuracies; High computational cost |

| 2D Similarity Search | SEA, PASS | Structural fingerprint comparison | Rapid screening of large libraries | Limited to structurally similar compounds |

| Machine Learning | ME-AI, MSA-3DCNN | Pattern recognition in feature space | Ability to learn complex relationships; High throughput | Data hunger; Limited interpretability; Transferability challenges |

The study revealed considerable differences in hit rates, true positive/negative identification, and hitlist composition between methods. While all approaches performed reasonably well, their complementary strengths suggested that a rational selection strategy aligned with specific research objectives maximizes the likelihood of success [18]. This highlights the importance of method selection in initial computational screens and the value of employing orthogonal approaches to mitigate methodological biases.

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

Systematic evaluations of computational methods provide crucial data on their predictive accuracy across different material classes. A comparison of computational chemistry methods for discovering quinone-based electroactive compounds for energy storage examined the performance of various methods in predicting redox potentials—a critical property for energy storage applications [19].

Table 2: Accuracy of Computational Methods for Redox Potential Prediction

| Computational Method | System | Accuracy (RMSE vs. Experiment) | Computational Cost | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field (FF) | OPLS3e | Not reported (geometry only) | Very Low | Initial conformation generation |

| Semi-empirical QM (SEQM) | Various | Moderate | Low | Large library pre-screening |

| Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) | DFTB | Moderate | Low-Medium | Intermediate accuracy screening |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | PBE | 0.072 V (gas), 0.051 V (solv) | High | Lead candidate validation |

| DFT | B3LYP | 0.068 V (gas), 0.052 V (solv) | High | High-accuracy prediction |

| DFT | M08-HX | 0.065 V (gas), 0.050 V (solv) | High | Benchmark studies |

The study found that geometry optimizations at lower-level theories followed by single-point energy DFT calculations with implicit solvation offered comparable accuracy to high-level DFT methods at significantly reduced computational costs. This modular approach presents a practical strategy for balancing accuracy and efficiency in computational screening pipelines [19].

Experimental Validation Frameworks and Protocols

Analytical Method Validation

For computational predictions to gain scientific acceptance, they must be validated using rigorously characterized experimental methods. Analytical method validation establishes documented evidence that a specific method consistently yields results that accurately reflect the true value of the analyzed attribute [22].

Key validation parameters include:

Specificity: The ability to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of other components. This must be evaluated in all method validations, as it is useless to validate any method if it cannot specifically detect the targeted analyte [22].

Accuracy: The agreement between the accepted reference value and the value found. This is typically assessed by spiking a clean matrix with known analyte amounts and measuring recovery rates [22].

Precision: The degree of scatter between multiple measurements of the same sample, evaluated under repeatability (same conditions) and intermediate precision (different days, analysts, instruments) conditions [22].

Range: The interval between the upper and lower concentration of analyte for which suitable accuracy, linearity, and precision have been demonstrated [22].

Robustness: The capacity of a method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in procedural parameters, identifying critical control points [22].

The validation process should begin by defining quality requirements in the form of allowable error, selecting appropriate experiments to reveal expected error types, collecting experimental data, performing statistical calculations to estimate error sizes, and comparing observed errors with allowable limits to judge acceptability [23].

Regulatory and Quality Standards

In regulated environments like clinical diagnostics or pharmaceutical development, specific standards govern test validation to ensure reliability and patient safety:

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA): Establishes quality standards for all clinical laboratory testing. CLIA certification is required for any laboratory performing testing on human specimens for clinical care, providing a baseline level of quality assurance more stringent than research laboratory settings [20].

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Oversight: For tests used to direct patient management in clinical trials, an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) application must typically be filed with the FDA. The agency recommends early consultation during test development to ensure appropriate validation strategies [20].

Professional Society Guidelines: Organizations like the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) develop practice standards that often exceed regulatory minimums, including proficiency testing programs and method validation guidelines [20].

For omics-based tests, recommendations specify that validation should occur in CLIA-certified laboratories using locked-down computational procedures defined during the discovery phase. This ensures clinical quality standards are applied before use in patient management decisions [20].

Hierarchical Validation Workflow

A systematic approach to bridging the computational-experimental gap employs hierarchical validation spanning multiple confirmation stages:

Diagram 1: Hierarchical validation workflow for bridging the computational-experimental gap.

This workflow begins with computational screening of virtual compound libraries, progressing through successive validation stages with increasing stringency. At each stage, compounds failing to meet criteria are eliminated, focusing resources on the most promising candidates [18] [17]. The hierarchical approach efficiently allocates resources by applying less expensive assays earlier in the pipeline and reserving resource-intensive methods for advanced candidates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful validation requires specific research tools and materials tailored to confirm computationally predicted properties. The following table details essential components of the validation toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Certified reference materials (CRMs), USP standards | Establish measurement traceability and accuracy | Method validation and qualification |

| Analytical Instruments | GC/MS, LC/MS/MS, NMR systems | Definitive compound identification and quantification | Confirmatory testing after initial screens |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Reporter gene assays, high-content screening platforms | Functional assessment of biological activity | Drug discovery target validation |

| Characterization Tools | XRD, XPS, SEM/TEM, FTIR | Material structure, composition, and morphology analysis | Materials science property confirmation |

| Bioinformatics Tools | SEA, PASS, PharmMapper, PharmaDB | Bioactivity profiling and off-target prediction | Computational biology cross-validation |

| Biological Reagents | Recombinant proteins, enzyme preparations | Target engagement and mechanistic studies | Biochemical validation of binding predictions |

The selection of appropriate tools depends on the specific validation context. For drug screening applications, initial immunoassay-based screens offer speed and cost-effectiveness, while GC/MS or LC/MS/MS confirmation provides definitive, legally defensible identification when needed [24]. In materials characterization, techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) and electron microscopy provide structural validation of predicted crystal phases and morphologies [10] [25].

Integrated Workflows for Computational-Experimental Translation

Machine Learning-Driven Discovery Frameworks

Modern materials discovery increasingly leverages machine learning frameworks that integrate computational prediction with experimental validation. The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework exemplifies this approach by translating experimental intuition into quantitative descriptors extracted from curated, measurement-based data [10].

The ME-AI workflow involves:

- Expert curation of refined datasets with experimentally accessible primary features

- Selection of interpretable features based on chemical knowledge (electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count)

- Model training using chemistry-aware algorithms

- Experimental validation of predictions to close the learning loop [10]

This approach successfully reproduced established expert rules for identifying topological semimetals while revealing hypervalency as a decisive chemical lever in these systems. Remarkably, the model demonstrated transferability by correctly classifying topological insulators in rocksalt structures despite being trained only on square-net compounds [10].

Cross-Disciplinary Integration Strategies

Bridging the validation gap requires deep integration between computational, experimental, and data science domains:

Iterative Feedback Loops: Experimental results should continuously inform and refine computational models. This iterative process helps identify systematic errors in predictions and improves model accuracy over time [17].

Multi-scale Modeling Approaches: Combining quantum mechanical calculations with mesoscale and continuum modeling addresses different aspects of the validation challenge, creating a more comprehensive prediction framework [25] [19].

High-Throughput Experimental Validation: Automated synthesis and characterization platforms enable rapid experimental verification of computational predictions, dramatically accelerating the discovery cycle [25].

Standardized Data Reporting: Implementing consistent data formats and metadata standards enables more effective knowledge transfer between computational and experimental domains, facilitating model refinement [20] [25].

These integrated approaches facilitate what has been termed "accelerated materials discovery," where ML-driven predictions guide targeted synthesis, followed by rapid experimental validation in a continuous cycle [25].

The journey from computational prediction to validated material requires navigating a complex pathway with multiple decision points. A successful navigation strategy includes:

- Methodical computational screening using complementary approaches to generate robust candidate lists

- Tiered experimental validation that applies appropriately rigorous methods at each stage

- Iterative refinement of computational models based on experimental feedback

- Adherence to established standards for analytical method validation where applicable

The increasing integration of machine learning and AI offers promising avenues for reducing the validation gap. These technologies can help identify more reliable descriptors, predict synthetic accessibility, and even guide autonomous experimental systems for faster validation cycles [10] [25] [17]. However, even as computational methods advance, experimental validation remains the essential bridge between in silico promise and real-world utility, ensuring that predicted materials translate into functional solutions for energy, medicine, and technology.

AI and Robotic Labs: Next-Generation Tools for Synthesis Prediction and Validation

The discovery of new functional materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, impacting fields from energy storage to electronics. While computational methods and machine learning have dramatically accelerated the identification of candidate materials with promising properties, a significant challenge remains: predicting whether a theoretically designed crystal structure can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory. This synthesizability gap often halts the journey from in-silico prediction to real-world application. Traditional approaches to screening for synthesizability have relied on assessing thermodynamic stability (e.g., energy above the convex hull) or kinetic stability (e.g., phonon spectrum analysis). However, these methods are imperfect; numerous metastable structures are synthesizable, while many thermodynamically stable structures remain elusive [1].

The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) presents a transformative opportunity. By fine-tuning these general-purpose models on comprehensive materials data, researchers can now build powerful tools that learn the complex, often implicit, rules governing material synthesis. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework is a state-of-the-art example of this approach, achieving a remarkable 98.6% accuracy in predicting the synthesizability of arbitrary 3D crystal structures [1] [26]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of CSLLM's performance against traditional and alternative machine learning methods, outlining its experimental protocols, and situating its impact within the broader research paradigm of validating predicted material properties.

Performance Comparison: CSLLM vs. Alternative Methods

The performance of CSLLM can be objectively evaluated by comparing its predictive accuracy against established traditional methods and other contemporary machine-learning approaches. The following tables summarize key quantitative comparisons based on experimental results.

Table 1: Overall Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Specific Method/Model | Reported Accuracy | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Stability | Energy Above Hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% [1] | Strong physical basis | Misses many metastable materials [1] |

| Traditional Stability | Phonon Spectrum (Lowest freq. ≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% [1] | Assesses dynamic stability | Computationally expensive; stable structures can have imaginary frequencies [1] |

| Bespoke ML Model | PU-CGCNN (Graph Neural Network) | ~92.9% (Previous SOTA) [1] | Directly learns from structural data | Limited by heuristic crystal graph construction [27] |

| Fine-tuned LLM | CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | 98.6% [1] [26] | High accuracy, excellent generalization, predicts methods & precursors | Requires curated dataset for fine-tuning |

| LLM-Embedding Hybrid | PU-GPT-Embedding Classifier | Outperforms StructGPT-FT & PU-CGCNN [27] | Cost-effective; powerful representation | Two-step process (embedding then classification) |

Table 2: Detailed Performance of the CSLLM Framework Components

| CSLLM Component | Primary Task | Reported Performance | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability LLM | Binary classification (Synthesizable vs. Non-synthesizable) | 98.6% accuracy [1] | Tested on a hold-out dataset; generalizes well to complex structures [1] |

| Method LLM | Classification of synthesis routes (e.g., solid-state vs. solution) | 91.0% accuracy [1] | Guides experimentalists on viable synthesis pathways |

| Precursor LLM | Identification of suitable solid-state precursors | 80.2% success rate [1] [26] | Focused on binary and ternary compounds |

Beyond raw accuracy, a critical advantage of CSLLM is its generalization ability. The model was trained on structures containing up to 40 atoms but maintained an average accuracy of 97.8% when tested on significantly more complex experimental structures containing up to 275 atoms, far exceeding the complexity of its training data [28]. This demonstrates that the model learns fundamental synthesizability principles rather than merely memorizing training examples.

Other LLM-based approaches also show promise. For instance, fine-tuning GPT-4o-mini on text descriptions of crystal structures (a model referred to as StructGPT-FT) achieved performance comparable to the bespoke PU-CGCNN model, while a hybrid method using GPT embeddings as input to a PU-learning classifier (PU-GPT-embedding) surpassed both [27]. This highlights that using LLMs as feature extractors can be a highly effective and sometimes more cost-efficient strategy than using them as direct classifiers.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The development and validation of CSLLM involved several critical, reproducible steps. The following workflow diagram outlines the core experimental process.

Dataset Curation and Construction

A robust and balanced dataset is the foundation of CSLLM's performance.

- Positive Samples: The positive data consisted of 70,120 experimentally verified synthesizable crystal structures obtained from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). The selection criteria included structures with a maximum of 40 atoms and seven different elements per unit cell, and disordered structures were excluded [1].

- Negative Samples: Constructing a reliable set of non-synthesizable structures is a known challenge. The researchers employed a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to generate a "CLscore" for over 1.4 million theoretical structures from databases like the Materials Project. The 80,000 structures with the lowest CLscores (below 0.1) were selected as high-confidence negative examples, creating a balanced dataset of 150,120 structures [1].

Material String: A Novel Text Representation for Crystals

A key innovation enabling the use of LLMs for this task is the development of the "material string" representation. Traditional crystal file formats like CIF or POSCAR contain redundant information. The material string condenses the essential information of a crystal structure into a concise, reversible text format [1] [28]. It integrates:

- Space group (SP)

- Lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ)

- Atomic species (AS), Wyckoff site symbols (WS), and Wyckoff positions (WP)

This efficient representation allows LLMs to process structural information effectively during fine-tuning without being overwhelmed by redundancy [1].

Model Fine-Tuning and Evaluation

The CSLLM framework is not a single model but comprises three specialized LLMs, each fine-tuned for a specific sub-task [1]:

- Synthesizability LLM: A binary classifier for synthesizability.

- Method LLM: A classifier for probable synthesis methods (e.g., solid-state or solution).

- Precursor LLM: A model to identify suitable chemical precursors.

The models were fine-tuned on the comprehensive dataset using the material string representation. Evaluation was performed on a held-out test set. The remarkable generalization was further tested on complex experimental structures with unit cell sizes far exceeding those in the training data [1] [28].

The Researcher's Toolkit for LLM-Driven Synthesis Prediction

Implementing and utilizing models like CSLLM requires a suite of computational and data resources. The following table details the key components of the research toolkit in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for CSLLM-like Workflows

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure Databases | Data Source | Provide positive (synthesizable) examples for training. | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1], Materials Project (MP) [27] |

| Theoretical Structure DBs | Data Source | Source of potential negative (non-synthesizable) samples. | Materials Project, Computational Material Database, OQMD, JARVIS [1] |

| PU-Learning Models | Computational Tool | Screen theoretical databases to identify high-confidence non-synthesizable structures for balanced datasets. | Pre-trained model from Jang et al. used to calculate CLscore [1] |

| Material String | Data Representation | Converts crystal structures into a concise, LLM-friendly text format for efficient fine-tuning. | Custom representation developed for CSLLM [1] [28] |

| Pre-trained LLMs | Base Model | General-purpose foundation models that can be customized via fine-tuning for domain-specific tasks. | Models like LLaMA [1]; GPT-3.5-turbo and GPT-4o have been fine-tuned for similar tasks [27] |

| Fine-tuning Techniques | Methodology | Process to adapt a general LLM to specialized tasks like synthesizability prediction. | Includes methods like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) for parameter-efficient tuning [28] |

| Robocrystallographer | Software Tool | Generates text descriptions of crystal structures from CIF files, an alternative input for LLMs. | Used in studies to create prompts for fine-tuning LLMs like StructGPT [27] |

The development of Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science. By achieving 98.6% accuracy in synthesizability prediction, CSLLM directly addresses the critical bottleneck in the materials discovery pipeline: transitioning from a promising theoretical design to a tangible, synthesizable material [1] [26]. Its integration into larger AI-driven frameworks, such as the T2MAT (text-to-material) agent, underscores its role as a vital validation step, ensuring that designed materials are not only high-performing but also practically realizable [29].

The experimental data clearly shows that fine-tuned LLMs like CSLLM significantly outperform traditional stability-based screening and set a new benchmark compared to previous bespoke machine learning models. Furthermore, the ability of these models to also predict synthesis methods and precursors with high accuracy provides experimentalists with a tangible roadmap, effectively bridging the gap between computation and the laboratory bench [1] [30]. As the field progresses, the focus will expand beyond mere prediction to enhancing the explainability of these models, allowing scientists to understand the underlying chemical and physical principles driving the synthesizability decisions, thereby fostering a deeper, more collaborative human-AI discovery process [27].

The discovery of new functional materials and potent drug molecules is often hampered by a critical bottleneck: determining how to synthesize them. For decades, researchers have relied on personal expertise, literature mining, and laborious trial-and-error experiments to identify viable precursors and reaction pathways. This process is both time-intensive and costly, particularly when working with novel, complex molecular structures.

Artificial intelligence is now transforming this landscape by providing computational frameworks that can predict synthetic feasibility, identify suitable starting materials, and propose viable reaction pathways with increasing accuracy. These systems are becoming indispensable tools for closing the gap between theoretical predictions of material properties and their practical realization through synthesis. This guide objectively compares the performance, methodologies, and experimental validation of leading AI platforms in precursor prediction for materials science and pharmaceutical research.

Comparative Analysis of AI Platforms for Synthesis Prediction

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics and capabilities of several prominent AI systems for synthesis planning and precursor prediction.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Platforms for Synthesis and Precursor Prediction

| AI System / Model | Primary Application | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation | Unique Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRESt (MIT) [31] | Materials recipe optimization & experiment planning | 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar; explored 900+ chemistries, 3,500+ tests in 3 months | Discovery of 8-element catalyst with record power density in formate fuel cells | Multimodal data integration (literature, experiments, imaging); robotic high-throughput testing; natural language interface |

| CSLLM Framework [1] | 3D crystal synthesizability & precursor prediction | 98.6% synthesizability prediction accuracy; >90% accuracy for synthetic methods & precursor identification | Successfully screened 45,632 synthesizable materials from 105,321 theoretical structures | Specialized LLMs for synthesizability, method, and precursor prediction; material string representation for crystals |

| EditRetro (Zhejiang University) [32] | Molecular retrosynthesis planning | 60.8% top-1 accuracy; 80.6% top-3 accuracy (USPTO-50K dataset) | Validated on complex reactions including chiral, ring-opening, and ring-forming reactions | String-based molecular editing; iterative sequence transformation; explicit edit operations |

| ChemAIRS [33] | Pharmaceutical retrosynthesis | Multiple feasible synthetic routes in minutes; considers FG compatibility, chirality | Integrated pricing and sourcing information for precursors | Commercial platform with industry-specific workflows; real-time precursor pricing |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

CRESt: Multimodal Learning for Materials Synthesis

The CRESt platform employs a sophisticated methodology that integrates diverse data sources to optimize materials recipes and plan experiments [31]:

Data Integration: The system incorporates information from scientific literature, chemical compositions, microstructural images, and experimental results. It creates knowledge embeddings for each recipe based on prior literature before conducting experiments.

Experimental Workflow:

- Principal component analysis reduces the search space in the knowledge embedding domain

- Bayesian optimization suggests new experiments in this reduced space

- Robotic systems execute synthesis (liquid-handling, carbothermal shock) and characterization (automated electron microscopy)

- Newly acquired data and human feedback are incorporated to refine the knowledge base

Visual Monitoring: Computer vision and language models monitor experiments, detecting issues like sample misplacement and suggesting corrections to improve reproducibility.

Figure 1: CRESt System Workflow for Materials Synthesis Planning

CSLLM: Crystal Synthesis Prediction Framework

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model framework employs three specialized LLMs, each fine-tuned for specific aspects of synthesis prediction [1]:

Dataset Curation:

- Positive examples: 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from ICSD (≤40 atoms, ≤7 elements)

- Negative examples: 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified via PU learning from 1.4M+ theoretical structures

Material String Representation: A novel text representation encoding essential crystal information (space group, lattice parameters, atomic species with Wyckoff positions) in a compact format suitable for LLM processing.

Model Architecture:

- Synthesizability LLM: Binary classification of synthesizability using fine-tuned transformer architecture

- Method LLM: Multiclass classification of synthesis method (solid-state vs. solution)

- Precursor LLM: Identification of appropriate solid-state precursors for binary/ternary compounds

Training Protocol: Models fine-tuned on the curated dataset using standard transformer training procedures with attention mechanisms aligned to material features critical to synthesizability.

EditRetro: Molecular Retrosynthesis via String Editing

EditRetro implements a novel approach to molecular retrosynthesis prediction by reformulating it as a string editing task [32]:

Molecular Representation: Molecules represented as SMILES strings, which provide a linear notation of molecular structure.

Edit Operations: Three explicit edit operations are applied iteratively:

- Sequence Relocation: Moving substrings within the molecular representation

- Placeholder Insertion: Adding special markers to indicate bond cleavage points

- Symbol Insertion: Adding atomic symbols to complete precursor structures

Model Inference:

- Relocation sampling identifies diverse reaction types

- Sequence augmentation creates varied edit paths through different molecular graph enumerations

- Iterative refinement progressively transforms target molecule into potential precursors

Figure 2: EditRetro's Iterative String Editing Process

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Validation in Functional Materials Discovery

The CRESt system was experimentally validated through a 3-month campaign to discover improved electrode materials for direct formate fuel cells [31]. The platform:

- Explored over 900 different chemical compositions

- Conducted more than 3,500 electrochemical tests

- Discovered an 8-element catalyst composition that achieved a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar compared to pure palladium

- Demonstrated record power density with only one-fourth the precious metals of previous devices

This validation confirmed CRESt's ability to navigate complex, high-dimensional composition spaces and identify non-intuitive yet high-performing material combinations that might be overlooked by human intuition alone.

Accuracy in Crystalline Materials Prediction

The CSLLM framework achieved exceptional performance in predicting synthesizability and precursors [1]:

Table 2: CSLLM Performance on Synthesis Prediction Tasks

| Prediction Task | Accuracy | Baseline Comparison | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal synthesizability | 98.6% | Outperforms energy above hull (74.1%) and phonon stability (82.2%) | 150,120 structures |

| Synthesis method classification | 91.0% | N/A | 70,120 ICSD structures |

| Precursor identification | 80.2% | N/A | Binary/ternary compounds |

| Generalization to complex structures | 97.9% | Maintains high accuracy on large-unit-cell structures | Additional test set |

The Synthesizability LLM demonstrated remarkable generalization capability, maintaining 97.9% accuracy when predicting synthesizability for experimental structures with complexity significantly exceeding its training data.

Performance in Organic Synthesis Planning

EditRetro was extensively evaluated on standard organic synthesis benchmarks [32]:

- USPTO-50K dataset: Achieved 60.8% top-1 accuracy (correct precursor in first prediction) and 80.6% top-3 accuracy (correct precursor in top three predictions)

- USPTO-FULL dataset: Maintained strong performance on the larger dataset with 1 million reactions, demonstrating scalability

- Complex reaction types: Successfully handled challenging transformations including stereoselective reactions, ring formations, and cleavage reactions

The model's iterative editing approach proved particularly effective at exploring diverse retrosynthetic pathways while maintaining chemical validity throughout the transformation process.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation of AI-predicted synthesis pathways requires specific experimental capabilities and resources. The table below details key reagents, instruments, and computational tools referenced across the validated studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Guided Synthesis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic Synthesis Systems | Liquid-handling robots; Carbothermal shock systems | High-throughput synthesis of predicted material compositions | Materials discovery (CRESt) [31] |

| Characterization Equipment | Automated electron microscopy; XRD; Electrochemical workstations | Rapid structural and functional analysis of synthesized materials | Materials validation [31] |

| Chemical Databases | ICSD; PubChem; Enamine; ChEMBL | Sources of known synthesizable structures and compounds for model training | All platforms [1] [34] |

| Computational Resources | GPU clusters; Cloud computing | Training and inference with large language models and neural networks | CSLLM, EditRetro [1] [32] |

| Precursor Libraries | Commercial chemical suppliers; In-house compound collections | Experimental validation of predicted precursor molecules | Pharmaceutical applications [33] [35] |

The integration of AI-driven precursor prediction with experimental validation represents a paradigm shift in materials and pharmaceutical research. The systems examined demonstrate that AI can not only predict viable synthetic pathways with remarkable accuracy but also discover non-intuitive solutions that elude human experts.

Critical to the adoption of these technologies is the recognition that they function most effectively as collaborative tools rather than autonomous discovery engines. The CRESt system's natural language interface and the CSLLM framework's user-friendly prediction interface exemplify this collaborative approach, enabling researchers to leverage AI capabilities while applying their domain expertise to guide and interpret results.

As these systems continue to evolve, their impact on accelerating the transition from theoretical material properties to synthesized realities will only grow. The experimental validations documented herein provide compelling evidence that AI-guided synthesis planning has matured from conceptual promise to practical tool, ready for adoption by research teams seeking to overcome the synthesis bottleneck in materials and drug discovery.

Leveraging Robotic Laboratories for High-Throughput Experimental Validation

The field of materials science and drug discovery is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the integration of robotic laboratories and high-throughput experimentation. This paradigm shift addresses the limitations of traditional research, which has long relied on manual, trial-and-error approaches that are often slow, labor-intensive, and prone to human error. Robotic laboratories automate the entire experimental workflow, from sample preparation and synthesis to analysis and data collection, enabling researchers to conduct orders of magnitude more experiments in a fraction of the time. This capability is crucial for the rapid validation of predicted material properties, a critical step in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to the design of advanced alloys and functional materials.