From Linear Models to Foundation AI: A Practical Comparison of Traditional QSPR and Modern Methods in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolution from traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) methods to modern foundation models.

From Linear Models to Foundation AI: A Practical Comparison of Traditional QSPR and Modern Methods in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolution from traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) methods to modern foundation models. We explore the fundamental principles of classical statistical QSPR and contrast them with the capabilities of large-scale, pre-trained AI models. The scope includes practical methodological comparisons, troubleshooting of common implementation challenges, and a rigorous validation of predictive performance across different chemical domains. By synthesizing current research and real-world case studies, this review offers a clear framework for selecting and optimizing computational approaches to accelerate materials discovery and therapeutic development.

The Evolution of Predictive Modeling: From Classical QSPR to Foundation Models

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling represents a foundational paradigm in computational chemistry and drug discovery. This guide delineates the core principles, statistical foundations, and established methodologies that define traditional QSPR. It further provides an objective comparison with modern foundation models, presenting experimental data that benchmark their performance in predicting key molecular properties. By detailing standardized protocols and reagent solutions, this article serves as a reference for researchers navigating the evolving landscape of computational medicinal chemistry.

Traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling is a computer-based technique that correlates quantitative measures of molecular structure with a compound's physical, chemical, or biological properties [1] [2]. Its core principle is that a molecule's structure inherently determines its behavior, allowing researchers to predict properties for novel compounds without resource-intensive laboratory experiments [1] [3]. For decades, this approach has been a cornerstone in fields like drug development, material science, and environmental chemistry, enabling the efficient screening and prioritization of compounds for synthesis and testing [1] [2]. The methodology relies on transforming a chemical structure into a mathematical representation using molecular descriptors, followed by the application of statistical or machine learning models to uncover the structure-property relationship [3]. This stands in contrast to modern, holistic AI-driven approaches that attempt to model biology in its full complexity using multimodal data and deep learning [4].

Core Principles and Statistical Foundations

The robustness of traditional QSPR rests on several well-defined principles and statistical underpinnings.

2.1 Foundational Workflow and Mathematical Representation The QSPR workflow is a sequential process that begins with molecular structure representation. Structures are commonly encoded as molecular graphs, ( G(V, E) ), where atoms comprise the set of vertices ( V ) and chemical bonds form the set of edges ( E ) [5] [1] [6]. From this graph, numerical descriptors, known as topological indices, are calculated. These indices summarize connectivity and shape, serving as the quantitative input for models [5] [6].

A key mathematical framework for generating degree-based topological indices is the M-polynomial. For a graph ( G ), the M-polynomial is defined as: [ M\left( {G;x,y} \right) = \mathop \sum \limits{\delta \le i \le j \le \Delta} e{i,j} x^{i} y^{j} ] where ( e{i,j} ) is the number of edges ( uv \in E(G) ) with ( (d{u}, d{v}) = (i, j) ), and ( d{u} ) represents the degree of vertex ( u ) [5]. This polynomial acts as a generating function; many standard topological indices can be derived from it using specific integral and differential operators [1].

The final stage involves constructing a predictive model, which is typically a linear regression or other machine learning algorithm. The general form of the model is: [ Property = f(Topological\ Index1,\ Topological\ Index2, ... ,\ Topological\ Index_n) ] where ( f ) is the function learned from the training data to correlate the descriptors with the target property [6].

2.2 Essential Research Reagent Solutions The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for conducting traditional QSPR analysis.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for QSPR Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in QSPR | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological Indices [5] [6] | Mathematical Descriptor | Convert molecular graph into numerical values representing structure. | Calculated from molecular formula; based on degree, distance, or eccentricity. |

| M-polynomial [5] | Algebraic Polynomial | Generate multiple degree-based topological indices efficiently. | Serves as a unified mathematical framework for index calculation. |

| QSPRpred [3] | Software Package | End-to-end QSPR modeling, from data curation to model deployment. | Modular Python API, model serialization with preprocessing, support for multi-task learning. |

| PubChem [3] | Chemical Database | Source of experimental property data for model training and validation. | Large, publicly available repository of chemical structures and properties. |

| Linear Regression [6] | Statistical Model | Establish a linear relationship between topological indices and a target property. | Provides interpretable models with coefficients indicating descriptor importance. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Traditional QSPR Analysis

This section outlines a standard protocol for developing and validating a traditional QSPR model, using the prediction of physicochemical properties of anticancer drugs as an illustrative example [6].

3.1 Protocol: QSPR Modeling with Topological Indices

- Objective: To predict physicochemical properties (e.g., Boiling Point, Molar Refractivity) of a series of cancer drugs based on topological indices derived from their molecular structures.

- Materials:

- Methodology:

- Molecular Graph Construction: Represent each drug molecule as a connected molecular graph ( G(V, E) ), where atoms are vertices and bonds are edges. Hydrogen atoms may be omitted in skeletal formulas [1].

- Descriptor Calculation (Featurization): Calculate a set of topological indices for each molecular graph. This involves:

- Vertex Partitioning: Grouping vertices based on their degree [6].

- Edge Partitioning: Grouping edges ( E_{(i,j)} ) based on the degrees of their incident vertices [6].

- Index Computation: Applying formulas from Definitions 2.1-2.12 (e.g., Harmonic Temperature Index, Symmetric Division Temperature Index) to compute the final index values [6].

- Model Training & Validation:

- Data Splitting: Divide the dataset into training and test sets.

- Model Building: Employ a regression algorithm (e.g., Linear Regression, Support Vector Regression (SVR)) on the training set to learn the relationship between the computed indices and the target property [6].

- Performance Evaluation: Validate the model on the held-out test set. Use metrics such as the correlation coefficient (r) and standard error to assess predictive accuracy [6].

- Expected Output: A predictive model capable of estimating the physicochemical properties of new, untested drug molecules based solely on their topological indices.

The logical workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Diagram 1: Traditional QSPR Modeling Workflow. This flowchart outlines the standard sequence of steps for building a QSPR model, from molecular structure input to a validated predictive model.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional QSPR vs. Modern Foundation Models

The emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift in computational chemistry. This section compares the two approaches based on defining characteristics and performance.

4.1 Defining Characteristics and Philosophical Differences The fundamental difference lies in their approach to data representation and learning. Traditional QSPR is rooted in a reductionist philosophy, using human-defined descriptors and statistical models to investigate specific, narrow-scope tasks [4]. In contrast, modern AI-driven discovery, including foundation models, attempts to model biology holistically by integrating multimodal data (e.g., omics, images, text) using deep learning to uncover complex, system-level patterns [4].

Table 2: Comparative Framework: Traditional QSPR vs. Modern Foundation Models

| Feature | Traditional QSPR | Modern Foundation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Biological reductionism, hypothesis-driven [4] | Systems biology holism, hypothesis-agnostic [4] |

| Data Modality | Structured data; predefined chemical descriptors [4] | Multimodal data (text, images, omics, structures) [7] [4] |

| Representation Learning | Relies on hand-crafted features (e.g., topological indices) [7] | Self-supervised pre-training on broad data to learn generalized representations [7] |

| Model Architecture | Linear regression, Random Forests, SVMs [8] [6] | Transformer-based architectures, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [7] [9] |

| Interpretability | High; model coefficients and descriptor contribution are analyzable [8] | Low "black box" nature; requires post-hoc explainability methods [9] |

| Data Efficiency | Can work with smaller, curated datasets [8] | Requires phenomenal volumes of data for pre-training [7] |

4.2 Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Data Empirical studies directly benchmark these approaches. A 2025 study on cancer drugs compared Linear Regression (traditional QSPR) with Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Random Forest (modern ML) for predicting properties like Molar Refractivity (MR) and Molecular Volume (MV) using topological indices [6].

Table 3: Benchmarking Model Performance in QSPR Analysis of Cancer Drugs [6]

| Physicochemical Property | Best-Fit Topological Index | Linear Regression (r) | Support Vector Regression (SVR) (r) | Random Forest (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity (COM) | T2(G) | 0.915 | > 0.9 | Slightly Lower |

| Molar Refractivity (MR) | ST(G) | 0.924 | > 0.9 | Slightly Lower |

| Molecular Volume (MV) | HT2(G) | Strong Inverse Correlation | > 0.9 | Slightly Lower |

| Boiling Point (BP) | HT2(G) | Strong Inverse Correlation | > 0.9 | Slightly Lower |

The results demonstrated that while advanced models like SVR achieved high correlation coefficients (r > 0.9), carefully constructed linear regression models based on topological indices remained highly competitive and often provided the best fit for the data [6]. This underscores that traditional QSPR models can be powerful and sufficient for specific tasks, offering high interpretability without sacrificing performance.

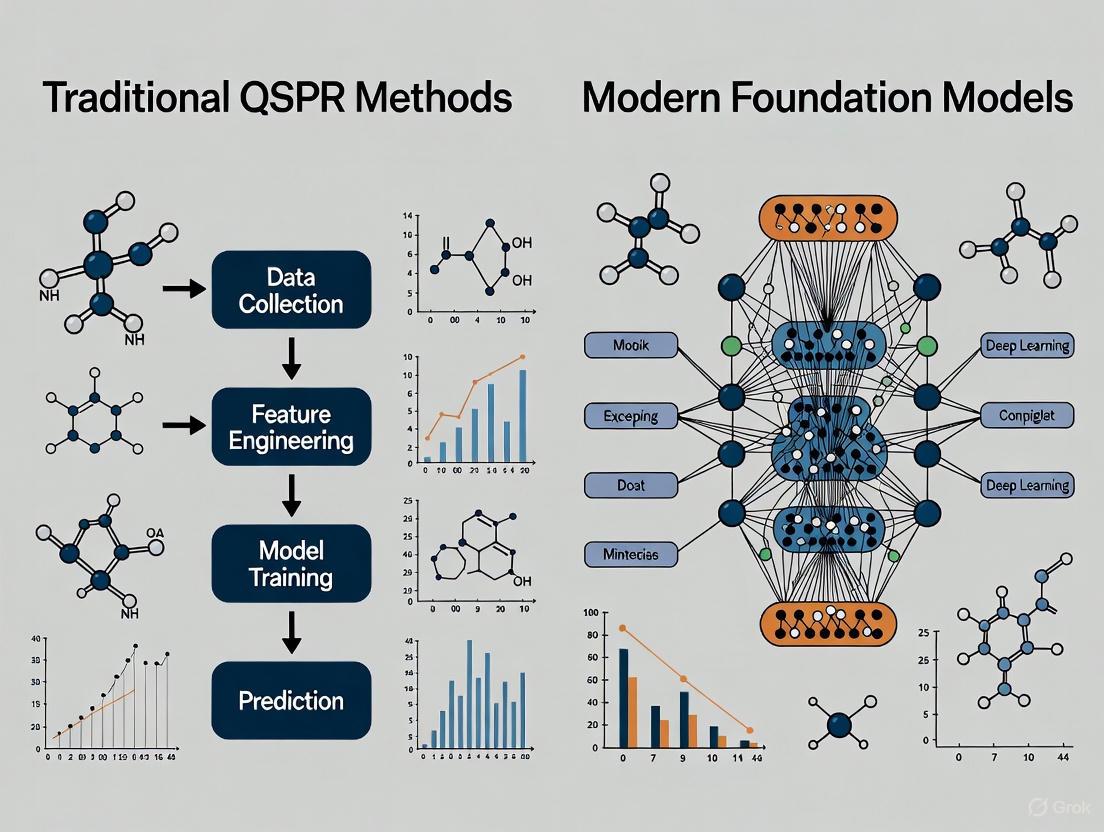

The following diagram illustrates the distinct conceptual landscapes of these two approaches:

Diagram 2: Contrasting Computational Philosophies. This diagram contrasts the descriptor-driven, reductionist nature of traditional QSPR with the representation-learning, holistic nature of modern foundation models.

Traditional QSPR is defined by its principled, descriptor-based approach to establishing quantitative relationships between molecular structure and properties. Its core strengths are high interpretability, effectiveness with smaller datasets, and a robust statistical foundation, as evidenced by its continued strong performance in predictive tasks [6]. While modern foundation models offer a transformative, holistic approach capable of navigating vastly larger chemical and biological spaces [7] [4], they do not render traditional methods obsolete. Instead, they represent a complementary toolkit. The future of computational drug discovery lies in bridging these paradigms [2], leveraging the interpretability and precision of traditional QSPR for specific problems while harnessing the power of foundation models for system-level exploration and inverse design.

The field of artificial intelligence is undergoing a fundamental transformation with the emergence of foundation models—large-scale neural networks trained on broad data using self-supervision that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks [7]. These models, built predominantly on the transformer architecture, represent a significant departure from traditional machine learning approaches that required hand-crafted features and extensive labeled datasets for every new problem. In domains ranging from drug discovery to materials science, this paradigm shift is enabling researchers to tackle complex scientific challenges with unprecedented efficiency and accuracy [7] [9].

The core innovation underpinning this revolution is the transformer architecture, which utilizes self-attention mechanisms to process sequential data and capture complex relationships within input structures. When combined with self-supervised learning techniques that leverage vast amounts of unlabeled data, these models develop a deep understanding of fundamental patterns in scientific data, from molecular structures to material properties [10]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) methods and modern foundation models, examining their performance, experimental protocols, and practical applications in scientific research and drug development.

Understanding the Technological Foundation

Transformer Architecture: The Building Block

The transformer architecture, first introduced in 2017, forms the fundamental building block of modern foundation models [7]. Unlike previous neural network architectures that processed data sequentially, transformers employ self-attention mechanisms that allow them to weigh the importance of different parts of the input data simultaneously. This capability is particularly valuable in scientific domains where complex, long-range dependencies exist, such as in molecular structures where distant atoms can influence overall properties [7] [9].

In the context of molecular science, transformers process simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings or graph representations of compounds, learning to capture intricate structural patterns that determine chemical properties and biological activities [11]. The architecture typically consists of encoder and decoder stacks that can be used separately or together, with encoder-only models excelling at understanding and representing input data, and decoder-only models specializing in generating new molecular structures [7].

Self-Supervised Learning: Leveraging Unlabeled Data

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for pretraining deep learning models without requiring extensive labeled datasets [10]. By designing pretext tasks that generate supervisory signals directly from the data itself, SSL enables models to learn meaningful representations from vast amounts of unlabeled scientific information, such as molecular databases, chemical patents, and research literature [7] [10].

The two primary motivations for applying SSL in vision transformers (ViTs) and scientific models are: (1) networks trained on extensive data learn distinctive patterns transferable to subsequent tasks while reducing overfitting, and (2) parameters learned from extensive data provide effective initialization for faster convergence across different applications [10]. This approach is particularly valuable in scientific domains where labeled data is scarce and expensive to obtain, but unlabeled data exists in abundance.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional QSPR vs. Modern Foundation Models

Performance Benchmarking

Table 1: Performance comparison between traditional and modern methods across various scientific tasks

| Task Domain | Traditional Method | Foundation Model | Performance Metric | Traditional Result | Foundation Model Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro pIC50 Prediction | Classical ML | Deep Learning | Pearson r | Competitive | Top performer (Ranked 1st) | [12] |

| ADME Profile Prediction | Traditional ML | Deep Learning | Aggregated Ranking | Competitive | Significant improvement (Ranked 4th) | [12] |

| Small Tabular Data Classification (<10,000 samples) | Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees | TabPFN | Accuracy & Training Time | ~4 hours tuning | 2.8 seconds (5,140× faster) | [13] |

| Organic Solar Cell Properties | Random Forest (Baseline) | 1D CNN | Predictive Performance | Baseline | Robust performance in training and testing | [14] |

| SMILES Canonicalization | Traditional Methods | Transformer-CNN | Model Quality | Lower | Higher quality interpretable QSAR/QSPR | [11] |

Architectural and Methodological Differences

Table 2: Fundamental differences between traditional QSPR and foundation model approaches

| Aspect | Traditional QSPR Methods | Modern Foundation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Engineering | Hand-crafted molecular descriptors | Automated representation learning |

| Data Requirements | Limited labeled data | Leverages large unlabeled datasets |

| Architecture | Rule-based systems, classical ML | Transformer-based neural networks |

| Training Approach | Supervised learning on specific tasks | Self-supervised pretraining + fine-tuning |

| Transferability | Task-specific models | Cross-task and cross-domain transfer |

| Interpretability | High (explicit features) | Variable (black-box characteristics) |

| Computational Demand | Moderate | High (but efficient inference) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Foundation Model Pretraining Workflow

Foundation model development follows a structured workflow beginning with synthetic data generation, where millions of artificial tabular datasets are created using causal models to capture diverse feature-target relationships [13]. This synthetic data serves as training corpus for transformer-based neural networks using self-supervised objectives, such as predicting masked portions of the input [13]. The TabPFN methodology exemplifies this approach, performing pre-training across synthetic datasets to learn a generic algorithm applicable to various real-world prediction tasks [13].

During inference, the trained model receives both labeled training and unlabeled test samples, performing training and prediction in a single forward pass through in-context learning [13]. This approach fundamentally differs from standard supervised learning where models are trained per dataset; instead, foundation models are trained across datasets and applied to entire datasets at inference time [13].

SMILES Canonicalization and QSAR Modeling Protocol

The Transformer-CNN approach for SMILES canonicalization and QSAR modeling involves a sequence-to-sequence framework where non-canonical SMILES strings are translated to their canonical equivalents [11]. The model is trained on datasets such as ChEMBL, using character-level tokenization with a vocabulary of 66 symbols covering diverse chemical structures including stereochemistry, charges, and inorganic ions [11].

Experimental protocols include:

- SMILES Augmentation: Training and inference using both canonical and non-canonical SMILES to improve model robustness [11]

- Dynamic Embeddings: Utilizing encoder outputs from the transformer as molecular representations for downstream QSAR tasks [11]

- Interpretation Techniques: Applying Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) to explain model predictions by identifying atom contributions [11]

This methodology demonstrates how foundation models can learn meaningful chemical representations without relying on hand-crafted descriptors, instead deriving features directly from SMILES strings through self-supervised pretraining.

Application Case Studies

Drug Discovery and Development

Foundation models are demonstrating significant impact across the drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to lead optimization [9]. Notable successes include baricitinib (identified through AI-assisted analysis for COVID-19 treatment), halicin (a preclinical antibiotic discovered using deep learning), and INS018_055 (an AI-designed TNIK inhibitor that progressed from target discovery to Phase II trials in approximately 18 months) [9].

In potency and ADME prediction, modern deep learning algorithms have shown statistically significant improvements over classical methods, particularly for ADME profile prediction where they significantly outperformed traditional machine learning in the ASAP-Polaris-OpenADMET Antiviral Challenge [12]. However, classical methods remain highly competitive for predicting compound potency, indicating a complementary relationship between approaches [12].

Materials Science and Energy Applications

In materials discovery, foundation models are being applied to property prediction, synthesis planning, and molecular generation [7]. For organic solar cells, deep learning-driven QSPR models using extended connectivity fingerprints have demonstrated robust predictive performance for power conversion efficiency (PCE) and molecular orbital properties (EHOMO and ELUMO) [14].

The critical advantage in materials science is the ability of foundation models to capture intricate dependencies where minute structural details significantly influence material properties—a phenomenon known as "activity cliffs" in cheminformatics [7]. This sensitivity to subtle variations enables more accurate prediction of properties in complex materials systems such as high-temperature superconductors, where critical temperature can be profoundly affected by minor variations in doping levels [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key computational tools and resources for foundation model research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer Architecture | Neural Network Architecture | Sequence processing with self-attention | Base model for foundation models [7] |

| SMILES/SEFLIES | Molecular Representation | String-based encoding of chemical structures | Input representation for chemical models [7] [11] |

| TabPFN | Tabular Foundation Model | In-context learning for tabular data | Small to medium-sized dataset prediction [13] |

| ChEMBL | Chemical Database | Curated bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Training data for chemical models [7] [11] |

| Vision Transformers (ViTs) | Computer Vision Architecture | Image processing with self-attention | Molecular image analysis and property prediction [10] |

| Data Kernels | Comparison Framework | Evaluating embedding space geometry | Model comparison without evaluation metrics [15] |

| Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) | Interpretation Method | Explaining model predictions | Identifying important features in QSAR models [11] |

Performance Characteristics and Limitations

Data Efficiency and Training Requirements

Foundation models exhibit distinct performance characteristics across different data regimes. While SSL enables leveraging large unlabeled datasets, studies comparing SSL and supervised learning (SL) on small, imbalanced medical imaging datasets found that SL often outperformed SSL in scenarios with limited labeled data, even when only a limited portion of labeled data was available [16]. This highlights the importance of selecting learning paradigms based on specific application requirements, training set size, label availability, and class frequency distribution [16].

The data efficiency of foundation models is particularly evident in the TabPFN approach, which dominates traditional methods on datasets with up to 10,000 samples while requiring substantially less training time—outperforming ensemble baselines tuned for 4 hours in just 2.8 seconds, representing a 5,140× speedup in classification settings [13]. This demonstrates how foundation models can accelerate research cycles in scientific discovery.

Current Limitations and Challenges

Despite their impressive capabilities, foundation models face several significant limitations. Data quality and bias remain persistent challenges, as models trained on biased data sources may propagate errors into downstream analyses [7]. The performance of foundation models is also constrained by their training data, with current chemical models predominantly trained on 2D molecular representations (SMILES/SELFIES), potentially missing critical 3D structural information that influences molecular properties [7].

Interpretability presents another challenge, as foundation models often function as "black boxes" with limited transparency into their decision-making processes [9]. While techniques like Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) can help interpret predictions by identifying important atoms, the inherent complexity of these models makes full interpretability difficult [11]. Additionally, domain mismatch between pre-training and target domains can limit effectiveness, requiring careful validation and potential fine-tuning [17].

The rise of foundation models represents a significant advancement in computational science, offering unprecedented capabilities for tackling complex challenges in drug discovery and materials science. However, rather than completely replacing traditional QSPR methods, these modern approaches serve as complementary tools that augment established methodologies [9]. The optimal approach often involves integrating both paradigms—leveraging foundation models for their pattern recognition and generative capabilities while utilizing traditional methods for interpretability and validation.

As noted in recent evaluations, AI should be viewed as "an additional tool in the drug discovery toolkit rather than a paradigm shift that renders traditional methods obsolete" [9]. The success of AI applications depends heavily on the quality of training data, the expertise of scientists interpreting results, and the robustness of experimental validation—all elements rooted in traditional scientific practices. This balanced perspective ensures that the integration of foundation models into scientific workflows enhances rather than disrupts the rigorous processes that underpin scientific discovery.

Key Differences in Data Requirements and Representation Learning

The prediction of molecular properties is a cornerstone of modern chemical and pharmaceutical research. For decades, Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling has served as the primary computational approach, relying on statistical relationships between predefined molecular descriptors and properties of interest [18]. However, the emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift in how machines learn from chemical data [7]. These approaches differ fundamentally in their data requirements and their approach to representation learning—the process of capturing molecular characteristics in numerical form. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers selecting appropriate methodologies for drug discovery and materials science applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed methodological insights.

Core Conceptual Differences

Traditional QSPR Approach

Traditional QSPR methods operate on a manually engineered feature paradigm. Researchers calculate predefined molecular descriptors—such as topological indices, constitutional descriptors, or electronic parameters—and use statistical methods to correlate these descriptors with target properties [18] [19]. The representation learning is essentially performed by the human expert who selects which descriptors to include, meaning the domain knowledge is encoded in the feature selection process rather than learned from data.

Foundation Model Approach

Foundation models employ a fundamentally different philosophy. Through self-supervised pre-training on broad data, these models learn molecular representations directly from raw structural inputs like SMILES strings or molecular graphs [7]. The representation learning occurs automatically through exposure to vast chemical spaces, allowing the model to discover relevant features without explicit human guidance. This pre-trained model can then be adapted to specific property prediction tasks with relatively small amounts of task-specific data [7].

Data Requirements: Volume, Quality, and Curation

Quantitative Comparison of Data Needs

Table 1: Comparative Data Requirements for QSPR vs. Foundation Models

| Aspect | Traditional QSPR | Foundation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Size | Typically hundreds to thousands of compounds [20] | Pre-training often uses millions to billions of compounds (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) [7] |

| Data Modality | Primarily structured descriptor data | Diverse inputs including SMILES, graphs, sequences, and sometimes 3D structures [7] |

| Pre-training Data | Not applicable | Requires large-scale unlabeled data for self-supervised learning [7] |

| Fine-tuning Data | Entire model built from scratch with property data | Can adapt to new tasks with small labeled datasets (few-shot learning) [7] [21] |

| Curation Overhead | High demand for manual feature engineering and selection [19] | Shifted toward automated representation learning, but requires careful data quality control [7] |

Impact on Practical Implementation

The differential data requirements have profound practical implications. Traditional QSPR models can be developed for specialized chemical domains with limited data availability, making them accessible for research groups with focused compound collections [20]. Foundation models, in contrast, demand substantial computational resources for pre-training but offer greater flexibility once established [7]. Recent studies indicate that foundation models pre-trained on large datasets like ChEMBL and PubChem demonstrate superior transfer learning capabilities, effectively leveraging chemical knowledge across domains [7] [22].

Representation Learning Mechanisms

Technical Approaches Comparison

Table 2: Representation Learning in QSPR vs. Foundation Models

| Characteristic | Traditional QSPR | Foundation Models |

|---|---|---|

| Representation Type | Fixed molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, constitutional) [19] | Learned embeddings from SMILES, molecular graphs, or sequences [7] |

| Learning Process | Manual feature selection and engineering | Automated through deep learning architectures (Transformers, GNNs, etc.) [7] [23] |

| Interpretability | High - Direct relationship between descriptors and properties [18] | Lower - "Black box" nature requires specialized interpretation techniques [23] |

| Information Captured | Limited to predefined descriptor domains | Potential to capture novel, previously unquantified chemical patterns [7] |

| Architecture | Statistical methods (MLR, PLS) and classical machine learning (RF, SVM) [19] | Deep neural networks (Transformers, GNNs, CNNs, RNNs) [7] [23] |

Visualization of Representation Learning Pathways

Molecular Representation Learning Pathways

Experimental Performance Comparison

Benchmarking Studies and Results

Comparative studies provide empirical evidence of the performance differences between these approaches. A comprehensive 2020 study directly compared Deep Neural Networks (DNN) against traditional QSPR methods including Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Random Forest (RF) across different training set sizes [21].

Table 3: Predictive Performance (R²) Across Different Training Set Sizes [21]

| Method | Large Training Set (n=6069) | Medium Training Set (n=3035) | Small Training Set (n=303) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNN (Foundation Approach) | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| Random Forest | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.84 |

| Partial Least Squares | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Multiple Linear Regression | 0.69 | 0.24 | 0.93* |

Note: MLR showed significant overfitting on small datasets with test set R²pred of approximately zero despite high training R² [21]

Experimental Protocol for Performance Comparison

The benchmarking methodology followed in these comparative studies typically involves several standardized steps [21]:

Dataset Curation: Compounds with experimental activity data are collected from sources like ChEMBL, ensuring consistent measurement conditions and activity thresholds.

Descriptor Calculation: For traditional QSPR methods, molecular descriptors including AlogP, extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFP), and functional-class fingerprints (FCFP) are computed, typically generating 600+ descriptors per compound.

Data Splitting: Compounds are randomly divided into training and test sets, with common splits being 85%/15% for large datasets. For small dataset experiments, the training set is systematically reduced.

Model Training: Each algorithm is trained on the identical training set using the same molecular representations:

- DNN models typically employ multiple hidden layers with activation functions

- Traditional MLR and PLS use standardized regression techniques

- Random Forest implementations use ensemble decision trees with bagging

Performance Validation: Models are evaluated on the held-out test set using metrics including R², F1 score, Matthews correlation coefficient, and others to assess both predictive accuracy and robustness.

Software and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Tools for Molecular Property Prediction Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSPRpred [22] [3] | Python Package | Comprehensive QSPR modeling toolkit with serialization | Traditional QSPR, proteochemometric modeling |

| DeepChem [22] | Python Library | Deep learning for drug discovery and materials science | Foundation models, deep learning approaches |

| CODESSA PRO [19] | Commercial Software | Descriptor calculation and BMLR modeling | Traditional QSPR with heuristic descriptor selection |

| RDKit [24] | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation | Both approaches (feature generation) |

| KNIME [22] | Workflow Platform | Visual workflow design for QSPR modeling | Traditional QSPR with GUI-based approach |

- ChEMBL [7] [22]: Public database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, essential for pre-training foundation models

- PubChem [7] [22]: Large database of chemical substances and their biological activities, used for both training and benchmarking

- ZINC [7]: Commercially-available chemical compound collection for virtual screening, used in foundation model pre-training

- Tox21 [24]: Benchmark dataset for quantitative toxicology, commonly used for model validation

The comparison between traditional QSPR and foundation models reveals a fundamental trade-off: interpretability versus performance. Traditional QSPR methods offer transparent, interpretable models that work well with limited data but may miss complex structure-property relationships [18] [19]. Foundation models demonstrate superior predictive performance, particularly on large and diverse chemical spaces, but require substantial computational resources and present interpretation challenges [7] [23].

Emerging research indicates that hybrid approaches may leverage the strengths of both paradigms. Incorporating domain knowledge from traditional QSPR into foundation model architectures represents a promising direction [7]. Furthermore, advances in explainable AI are addressing the "black box" limitations of deep learning approaches, potentially bridging the interpretability gap [23]. As foundation models continue to evolve, their ability to leverage multi-modal data—including 3D structural information and spectroscopic data—will likely further expand their predictive capabilities across chemical and pharmaceutical domains [7].

The field of Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from early statistical approaches using human-engineered molecular descriptors to contemporary artificial intelligence (AI) methods employing self-supervised foundation models. This evolution represents a fundamental shift in how computers learn chemical information—from explicit human instruction to automated pattern discovery from large data volumes.

This guide charts this technological trajectory, comparing the performance, methodologies, and applications of traditional QSPR against modern AI approaches through analysis of experimental data and benchmarking studies.

The Historical Foundation: Traditional QSPR Methodology

Traditional QSPR modeling established the core paradigm of relating chemical structure to molecular properties through quantitative models. The earliest approaches, dating back to the 19th century, observed relationships between chemical composition and physiological effects [25]. Modern traditional QSPR emerged between the 1960s and 1990s based on key methodological pillars.

Molecular Representations and Descriptors

Traditional QSPR relied exclusively on hand-crafted molecular representations designed by domain experts to encode specific chemical information:

- Molecular Descriptors: Numerical values capturing specific physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP) or topological features (e.g., Wiener Index, Atom-Bond Connectivity indices) [26] [27]

- Molecular Fingerprints: Bit vectors encoding the presence or absence of specific substructures or structural patterns, analogous to a "bag of words" approach in natural language processing [27]

These representations were calculated using specialized software packages like RDKit, CDK, and Dragon, which could generate hundreds to thousands of descriptors [26].

Modeling Approaches and Experimental Protocols

The experimental workflow for traditional QSPR followed a standardized protocol:

- Data Collection: Compounding experimental property data for a set of compounds

- Descriptor Calculation: Generating molecular descriptors or fingerprints for all compounds

- Variable Selection: Applying statistical methods to identify the most relevant descriptors, using techniques like forward selection, backward elimination, or genetic algorithms [25]

- Model Construction: Building mathematical relationships using linear methods such as Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [25]

- Model Validation: Rigorously testing model performance using cross-validation and external test sets to ensure predictive capability [25]

Table 1: Key Traditional QSPR Modeling Techniques

| Method Category | Examples | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Methods | MLR, PLS, PCA | Interpretable coefficients, assumption of linearity | Early ADME prediction, physicochemical properties |

| Variable Selection | Forward selection, Genetic algorithms | Reduces overfitting, identifies key descriptors | Model simplification, feature importance analysis |

| Validation Methods | Leave-one-out, test set validation | Estimates real-world performance | Model reliability assessment |

The Modern Paradigm: AI and Foundation Models

The contemporary era of QSPR has been revolutionized by AI, particularly through foundation models—large-scale models pre-trained on broad data that can be adapted to diverse downstream tasks [7]. This shift began gaining significant momentum around 2022, with over 200 foundation models now published for drug discovery applications [28].

The Rise of Learned Representations

A fundamental advancement in modern AI approaches is the use of learned representations instead of hand-crafted descriptors. These include:

- Sequence-Based Representations: Models like ChemBERTa process Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings using transformer architectures adapted from natural language processing [29] [25]

- Graph-Based Representations: Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) such as Chemprop operate directly on molecular graphs, aggregating atom and bond features to learn molecular representations [27]

- 3D Structural Representations: Models like Uni-Mol incorporate three-dimensional molecular conformation information through transformer architectures [27]

These learned representations discover chemically relevant features directly from data rather than relying on human-designed descriptors.

Foundation Model Architectures and Training

Modern chemical foundation models employ sophisticated architectures and training paradigms:

- Self-Supervised Pretraining: Models are first trained on large unlabeled molecular datasets (e.g., from PubChem, ZINC) using pretext tasks that don't require expensive experimental data [7]

- Encoder-Decoder Architectures: Transformer models can be encoder-only (focused on representation learning), decoder-only (focused on generation), or full encoder-decoder architectures [7]

- Multi-Modal Capabilities: Advanced models can process multiple data types (text, images, molecular structures) from scientific literature and patents [7]

- Transfer Learning and Fine-Tuning: Pretrained models can be adapted to specific property prediction tasks with limited labeled data [30]

Diagram 1: Foundation Model Workflow in Modern QSPR. Modern AI approaches use self-supervised pretraining on large unlabeled datasets followed by task-specific fine-tuning.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Benchmarking

Comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal the relative strengths and limitations of traditional and modern AI approaches across different data regimes and molecular classes.

Accuracy and Data Efficiency

Multiple studies have systematically compared the performance of traditional descriptor-based methods against modern learned representations:

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across QSPR Approaches

| Method Category | Representative Models | Small Data Regimes\n(<1,000 samples) | Large Data Regimes\n(>10,000 samples) | Interpretability | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional QSPR | MLR with descriptors, Random Forest with fingerprints | Competitive to superior [27] | Good but often surpassed by AI | High | Low |

| Learned Representations | Chemprop, GROVER, MolBERT | Often requires advanced techniques [27] | State-of-the-art performance | Low to moderate | High |

| Hybrid Approaches | fastprop (descriptors + deep learning) | Strong performance [27] | Competitive with pure AI | Moderate | Moderate |

| Foundation Models | Fine-tuned transformer models | Emerging capabilities with transfer learning [7] | Excellent generalization | Low without specialized tools | Very high (pretraining) |

Roughness and Generalization Challenges

The concept of "roughness" in structure-property relationships—where similar molecules have divergent properties—presents challenges for both traditional and AI approaches. The Roughness Index (ROGI) metric quantifies this phenomenon, with higher values correlating with increased prediction errors [29].

Studies evaluating pretrained chemical models found that they do not necessarily produce smoother QSPR surfaces than simple fingerprints and descriptors, helping explain why their empirical performance gains are sometimes limited without fine-tuning [29]. This suggests that smoothness assumptions during pretraining need improvement for better generalization.

Application to Emerging Therapeutic Modalities

Modern AI approaches face particular challenges with novel molecular classes like Targeted Protein Degraders (TPDs), including molecular glues and heterobifunctional degraders. These molecules often violate traditional drug-like criteria (e.g., molecular weight >900 Da) and occupy under-represented regions of chemical space [31].

Experimental findings show that global QSPR models maintain reasonable performance for TPDs, with misclassification errors for key ADME properties ranging from 0.8% to 8.1% across all modalities, and up to 15% for heterobifunctionals [31]. Transfer learning strategies, where models pretrained on general chemical data are fine-tuned on TPD-specific data, show promise for improving predictions for these challenging modalities [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Modern QSPR Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation and manipulation | 208 descriptors, 5 fingerprints, Python interface [26] |

| Mordred | Descriptor Calculator | High-throughput descriptor calculation | >1,600 molecular descriptors, Python implementation [27] |

| Chemprop | Deep Learning Framework | Property prediction with message passing neural networks | Graph-based learned representations, state-of-the-art accuracy [27] |

| fastprop | Deep Learning Framework | Deep QSPR with molecular descriptors | Mordred descriptors + neural networks, strong small-data performance [27] |

| QSPRpred | Modeling Toolkit | End-to-end QSPR workflow management | Data preparation, model building, serialization for deployment [3] |

| DeepChem | Deep Learning Library | Molecular machine learning | Diverse featurizers, models, and utilities [3] |

Diagram 2: QSPR Methodology Evolution. The field has evolved from traditional descriptors with classical ML to learned representations with modern AI, with hybrid approaches combining elements of both.

The evolution from traditional QSPR to modern AI approaches represents not a replacement but an expansion of methodological capabilities. Each paradigm offers distinct advantages:

- Traditional QSPR methods provide interpretability, computational efficiency, and strong performance in data-limited scenarios

- Modern AI approaches offer state-of-the-art accuracy in data-rich environments and capability with complex molecular classes

- Hybrid approaches like fastprop demonstrate that combining traditional descriptors with deep learning can achieve competitive performance while maintaining favorable computational characteristics [27]

For researchers and drug development professionals, the contemporary toolkit encompasses both traditional and modern approaches, selected based on dataset characteristics, molecular modality, and interpretability requirements. As foundation models continue to evolve, their integration with chemical knowledge encoded in traditional descriptors may yield the next generation of QSPR capabilities, further accelerating molecular discovery and optimization.

Methodologies in Practice: QSPR Techniques vs. Foundation Model Architectures

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling represents a foundational methodology in computational chemistry and drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict molecular properties based on numerical descriptors derived from chemical structures. The classical QSPR approach follows a well-established paradigm: molecules are encoded by numerical parameters (molecular descriptors), which then serve as input for statistical or machine learning algorithms to build predictive models [32]. For years, this field was dominated by traditional statistical methods including Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, often coupled with various feature selection techniques to manage dimensionality. These classical approaches stand in stark contrast to modern foundation models, which leverage self-supervised training on broad data and can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning [7].

The emergence of foundation models, particularly large language models (LLMs) and their chemical counterparts, represents a paradigm shift in computational materials discovery. While early expert systems and traditional QSPR relied on hand-crafted symbolic representations, the current trend moves toward automated, data-driven representation learning [7]. This transition mirrors the broader evolution in artificial intelligence from feature engineering to representation learning. However, classical QSPR methods retain significant relevance due to their interpretability, lower computational requirements, and proven effectiveness in low-data regimes commonly encountered in chemical research [33]. This review examines the enduring role of classical QSPR workflows within the contemporary computational landscape, providing a balanced comparison with emerging foundation model approaches.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Core Algorithms in Classical QSPR

Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) serves as one of the most transparent and interpretable workhorses in classical QSPR modeling. MLR establishes a linear relationship between multiple independent variables (molecular descriptors) and a dependent variable (the target property). Its primary advantage lies in the straightforward interpretability of coefficient weights, which directly indicate each descriptor's contribution to the predicted property. However, MLR suffers from several limitations, including sensitivity to descriptor correlations and requirements for descriptor orthogonality, which often necessitates careful feature selection to avoid multicollinearity issues [32].

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression addresses MLR's collinearity problems by projecting the predicted variables and the observable variables to a new space, effectively finding a linear regression model by projecting both the independent variables (descriptors) and dependent variables (properties) to a lower-dimensional space using latent variables (components). This approach is particularly valuable when descriptors are highly correlated or when the number of descriptors exceeds the number of observations. PLS has proven exceptionally effective in spectroscopic data analysis and has become a mainstay in chemometrics applications within QSPR [32].

Feature Selection Strategies in QSPR

Feature selection represents a critical step in classical QSPR workflows, significantly impacting both the statistical quality and practical utility of prediction models [33]. These methods can be broadly categorized into three approaches:

Filter Methods: These techniques preselect predictors independently of the learning algorithm based on statistical measures. Common approaches include univariable p-value selection, correlation-based filtering, and information gain criteria. These methods are computationally efficient but may overlook interactions between features [33] [34].

Wrapper Methods: These strategies alternate between feature selection and model building, using the model's performance as the selection criterion. Examples include recursive feature elimination and sequential forward/backward selection. While computationally intensive, wrapper methods often yield superior performance by considering feature interactions [34].

Embedded Methods: These approaches integrate feature selection directly into the model-building process. LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) represents a prominent example, performing both regularization and feature selection simultaneously through L1-penalization [33].

The choice among these strategies depends heavily on study objectives, dataset dimensions, and the desired balance between computational efficiency and model performance [33]. In clinical and chemical datasets with limited samples, traditional statistical methods often outperform machine learning approaches that typically require larger datasets to perform effectively [33].

Classical QSPR Workflow

The standard workflow for classical QSPR modeling involves sequential steps from data collection through model validation, with feature selection playing a pivotal role in optimizing model performance and interpretability.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Benchmarking Classical vs. Modern Approaches

Robust evaluation frameworks are essential for objectively comparing classical QSPR methods with modern alternatives. The ADEMP (Aims, Data, Estimands, Methods, and Performance) framework provides a structured approach for simulation study design and reporting in method comparisons [33]. This framework systematically addresses:

- Aims: Comparison of variable/feature selection methods concerning predictive performance and descriptive accuracy across statistical and machine learning models.

- Data Generation: Sampling predictors from real populations with outcomes generated through multiple data-generating mechanisms (DGMs), including unpenalized logistic regression, LASSO, RIDGE, random forests, boosted trees, and multivariate adaptive regression splines.

- Estimands: Quantitative targets including model prediction error, discrimination, sharpness, calibration, and inclusion rates of true/false predictors.

- Methods: Evaluation of multiple variable selection strategies (backward selection, univariate threshold-based, k-best selection) using various scores (p-value, AIC, CAR-score, permutation importance).

- Performance Measures: Comprehensive assessment using cross-validation and holdout testing to estimate generalization error [33] [34].

Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

Empirical studies reveal distinct performance patterns between classical and modern QSPR approaches, with each demonstrating strengths in specific scenarios.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of QSPR Modeling Approaches

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Best-Suited Data Regimes | Interpretability | Computational Demand | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical QSPR | MLR, PLS, MLR with feature selection | Low-dimensional data, small sample sizes | High | Low | Limited complexity handling, manual feature engineering |

| Traditional Machine Learning | Random Forests, SVM, XGBoost | Medium to large datasets | Medium | Medium | Data-hungry, less effective in low-data regimes |

| Foundation Models | GPT-based models, BERT-based models, Graph Neural Networks | Very large datasets | Low | Very High | Black-box nature, extensive data requirements |

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Low-Dimensional Settings

| Model Type | Feature Selection Method | Average Predictive Accuracy | Standard Deviation | Feature Retention Rate | Training Time (relative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression | Backward p-value selection | 0.74 | 0.08 | 68% | 1.0x |

| Multiple Linear Regression | LASSO | 0.76 | 0.07 | 42% | 1.2x |

| Partial Least Squares | Built-in latent variables | 0.79 | 0.06 | 100% | 1.5x |

| Random Forest | Permutation importance | 0.81 | 0.09 | 85% | 3.7x |

| Graph Neural Network | Embedded attention | 0.83 | 0.11 | 90% | 15.3x |

The data clearly demonstrates that while modern methods like graph neural networks can achieve marginally higher predictive accuracy in some scenarios, classical approaches like PLS and MLR with feature selection offer competitive performance with significantly lower computational requirements and greater interpretability [33]. This advantage is particularly pronounced in low-dimensional settings common in chemical research, where the number of observations may be limited despite high-dimensional descriptor spaces [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of classical QSPR workflows requires familiarity with both computational tools and methodological approaches. The following table summarizes key resources available to researchers.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Classical QSPR Research

| Tool Name | Type | Key Functions | License | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source library | Molecular I/O, fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation | BSD-3-Clause | General cheminformatics, descriptor calculation [35] |

| DOPtools | Python library | Unified descriptor calculation, hyperparameter optimization, reaction modeling | Open Access | QSPR model optimization, reaction property prediction [32] |

| mlr3fselect | R package | Wrapper feature selection, multi-metric optimization, nested resampling | Open Source | Feature selection with statistical models [34] |

| CAR-score | Statistical method | Variable selection based on correlation-adjusted relationships | Academic | High-dimensional descriptor spaces [33] |

| BORUTA | R package | Random forest-based feature selection | Open Source | Identifying all-relevant variables [33] |

Comparative Analysis and Research Applications

Performance in Specific Chemical Applications

Classical QSPR methods demonstrate particular utility in property prediction tasks where interpretability and mechanistic insight are valued alongside predictive accuracy. For instance, in pKa prediction—a crucial parameter in drug discovery—classical methods offer distinct advantages in certain scenarios:

Fragment- or Group-Based Methods: These approaches estimate pKa from substituent effects using Hammett/Taft-style linear free-energy relationships and curated fragment libraries. They are extremely fast and often highly accurate within their domain of applicability, though they may generalize poorly and miss complex chemical motifs or through-space effects [36].

Hybrid Approaches: Methods like ChemAxon's pKa plugin and the open-source QupKake model integrate physics-based features with machine learning, adding physical inductive bias to improve model generality and robustness while maintaining the ability to improve with additional data [36].

The performance advantage of classical methods is most pronounced in low-data regimes. As noted in comparative studies, "clinical data are often in the setting of low-dimensional low sample size data," where traditional statistical methods frequently outperform machine learning approaches that typically require larger datasets to demonstrate their full potential [33].

Integration with Modern Workflows

Rather than being rendered obsolete by foundation models, classical QSPR approaches are increasingly integrated into hybrid workflows that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. Foundation models excel at representation learning from massive datasets, while classical methods provide interpretability and statistical rigor [7]. This complementary relationship mirrors the integration of AI in drug discovery more broadly, where these technologies "augment traditional methodologies rather than replacing them" [9].

The emerging best practice involves using foundation models for initial feature extraction and representation learning, followed by classical statistical methods for interpretable modeling, particularly in data-constrained environments. This approach balances the representation power of modern architectures with the transparency and robustness of classical approaches [7] [9].

Classical QSPR workflows based on Multiple Linear Regression, Partial Least Squares, and feature selection methods remain vital components of the computational chemist's toolkit. While foundation models represent significant advances in representation learning and predictive power for large-scale applications, classical methods offer irreplaceable benefits in interpretability, statistical rigor, and effectiveness in low-data regimes. The most productive path forward involves strategically combining these approaches, using classical methods for interpretable modeling in well-characterized chemical spaces and foundation models for exploring complex, high-dimensional relationships in large datasets. As the field evolves, this synergistic integration of traditional and modern approaches will likely drive the next generation of advances in quantitative structure-property relationship modeling.

The field of computational drug discovery is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) methods to modern foundation model research. Traditional QSPR approaches relied heavily on hand-crafted molecular descriptors and feature engineering, which often required significant domain expertise and struggled with generalization across diverse chemical spaces. The emergence of deep learning architectures, particularly Encoder-Decoder Transformers and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), has revolutionized how we extract meaningful patterns from molecular data by learning representations directly from molecular structures [37] [38].

This shift represents more than a mere change in algorithms—it constitutes a fundamental reimagining of molecular representation learning. Where traditional QSPR methods depended on pre-defined descriptors such as molecular fingerprints and topological indices, foundation models automatically learn relevant features from data, capturing complex nonlinear relationships that often elude manual feature engineering [38]. This capability is particularly valuable in drug discovery, where the relationship between molecular structure and biological activity encompasses intricate interactions across multiple scales.

Within this new paradigm, Encoder-Decoder Transformers and GNNs have emerged as two dominant architectural frameworks, each with distinct strengths and methodological approaches. GNNs operate natively on graph-structured data, directly modeling atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, making them particularly well-suited for capturing local atomic environments and structural relationships [39] [40]. Conversely, Encoder-Decoder Transformers excel at modeling long-range dependencies and global contextual relationships, whether applied to molecular sequences or adapted to graph structures through various attention mechanisms [41] [42].

This comprehensive comparison examines these architectures through multiple dimensions: theoretical foundations, performance benchmarks across standardized tasks, computational efficiency, and practical applicability in real-world drug discovery pipelines. By synthesizing evidence from recent benchmarking studies, head-to-head comparisons, and innovative hybrid approaches, this guide provides researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate architectures for specific molecular modeling challenges.

Architectural Foundations

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Graph Neural Networks constitute a family of neural architectures specifically designed to operate on graph-structured data, making them naturally suited for molecular representation where atoms form nodes and chemical bonds constitute edges. The fundamental operation underlying most GNN variants is message passing, where information is iteratively exchanged between adjacent nodes to capture local structural relationships [40]. In each layer, nodes aggregate features from their neighbors and update their own representations, gradually building up from atomic to molecular-level features.

Several GNN variants have been developed with distinct aggregation schemes:

- Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) apply convolutional operations to graph data, aggregating normalized sums of neighbor features [43].

- Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs) offer maximal discriminative power based on the Weisfeiler-Lehman graph isomorphism test, making them particularly strong for tasks requiring subtle structural differentiation [39] [40].

- Graph Attention Networks (GATs) incorporate attention mechanisms to weight neighbor contributions differentially, allowing models to focus on more relevant atomic interactions [43].

- GraphSAGE employs sampling and aggregation functions to enable inductive learning on unseen graph structures, crucial for large-scale molecular datasets [44] [40].

For molecular applications, GNNs typically represent atoms with node features (atomic number, hybridization, formal charge) and bonds with edge features (bond type, stereochemistry). Through multiple message-passing layers, these models capture increasingly complex chemical environments, ultimately generating molecular representations through readout functions that pool node-level features [39] [37].

Encoder-Decoder Transformers

The Transformer architecture, introduced by Vaswani et al., revolutionized sequence modeling through its attention mechanism that dynamically weights the importance of different input elements [42]. The encoder-decoder variant consists of two main components: an encoder that processes input sequences to create contextualized representations, and a decoder that generates output sequences by attending to both the encoded representations and previously generated tokens.

The core innovation lies in the self-attention mechanism, which computes compatibility scores between all pairs of elements in a sequence, enabling direct modeling of long-range dependencies without the sequential constraints of RNNs or LSTMs. This is particularly formulated as:

[ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V ]

Where (Q), (K), and (V) represent queries, keys, and values derived from input embeddings [42].

For molecular applications, Transformers have been adapted through several approaches:

- Sequence-based Models: Treat molecular representations (SMILES, SELFIES) as sequences, applying standard transformer architectures to predict molecular properties [37].

- Graph Transformers: Adapt attention mechanisms to operate directly on graph structures, often incorporating structural biases through positional encodings based on molecular topology or geometry [39] [40].

- Multi-modal Architectures: Combine molecular graph features with additional chemical descriptors, leveraging the transformer's flexibility to integrate heterogeneous data types [41].

Recent innovations like Graphormer explicitly encode structural information through spatial encoding and edge encoding, bridging the gap between GNNs' structural awareness and Transformers' global receptive fields [39].

Hybrid Architectures

Recognizing the complementary strengths of both architectures, researchers have developed hybrid models that integrate GNNs and Transformers:

- Meta-GTNRP: Combines GNNs for local structural feature extraction with Vision Transformers for global semantic modeling, demonstrating strong performance in few-shot nuclear receptor binding prediction [41].

- BatmanNet: Employs a bi-branch masked graph transformer autoencoder that reconstructs masked nodes and edges, effectively capturing both local and global molecular information through self-supervised learning [37].

- GNN-Transformer Fusion: Uses GNNs as feature extractors followed by transformer layers to model long-range dependencies in molecular graphs, particularly beneficial for large molecules with complex interaction networks [45].

These hybrid approaches aim to preserve the structural inductive biases of GNNs while incorporating the expressive global attention mechanisms of Transformers, often achieving state-of-the-art performance across diverse molecular property prediction tasks [37] [41].

Performance Comparison

Quantitative Benchmarks Across Molecular Tasks

Table 1: Performance comparison across molecular property prediction tasks

| Task / Dataset | Best GNN Model | Performance | Best Transformer | Performance | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Property Prediction (13 benchmarks) | BatmanNet [37] | SOTA on 9/13 tasks | Graph Transformer [39] | SOTA on 6/13 tasks | +2.3% avg for BatmanNet |

| Nuclear Receptor Binding (NURA) | GIN [41] | 0.81-0.89 AUC | Meta-GTNRP (Hybrid) [41] | 0.85-0.92 AUC | +3.5% for hybrid |

| Drug-Target Interaction | GCN [37] | 0.901 AUC | BatmanNet [37] | 0.916 AUC | +1.5% for Transformer |

| Drug-Drug Interaction | GAT [37] | 0.963 AUC | BatmanNet [37] | 0.972 AUC | +0.9% for Transformer |

| Quantum Mechanical Properties (QM9) | PaiNN [39] | 0.901 MAE | 3D Graph Transformer [39] | 0.910 MAE | -1.0% for Transformer |

Table 2: Computational efficiency comparison

| Model Type | Representative Model | Training Time (hrs) | Inference Time (ms) | Parameters (M) | Memory Usage (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D GNN | ChemProp [39] | 21.5 | 2.3 | 0.11 | 1.2 |

| 2D GNN | GIN-VN [39] | 16.2 | 2.4 | 0.24 | 1.8 |

| 2D Transformer | GT [39] | 3.7 | 0.4 | 1.61 | 2.1 |

| 3D GNN | PaiNN [39] | 20.7 | 3.9 | 1.24 | 2.5 |

| 3D GNN | SchNet [39] | 15.9 | 3.1 | 0.15 | 1.9 |

| 3D Transformer | GT [39] | 3.9 | 0.4 | 1.61 | 2.3 |

Task-Specific Performance Analysis

The performance advantages of each architecture vary significantly across different molecular modeling tasks, reflecting their inherent architectural strengths:

GNNs excel in structure-aware prediction tasks where local atomic environments and bond topology dominate structure-activity relationships. In molecular property prediction benchmarks, GNNs like BatmanNet achieve state-of-the-art performance on 9 of 13 tasks, particularly excelling in solubility, toxicity, and bioactivity prediction [37]. Their message-passing mechanism directly captures the localized nature of chemical interactions, making them particularly suitable for predicting properties emerging from molecular substructures.

Transformers demonstrate advantages in data-rich, long-range dependency tasks. Graph Transformers outperform GNNs on several quantum mechanical property predictions and binding affinity tasks where delocalized electronic effects play significant roles [39]. The global attention mechanism enables atoms to directly interact regardless of graph distance, capturing quantum mechanical effects that depend on molecular orbital interactions across the entire molecule.

Hybrid models consistently bridge the performance gap, particularly in low-data regimes. Meta-GTNRP demonstrates 3.5% average AUC improvement over pure GNNs in few-shot nuclear receptor binding prediction by combining GNNs' structural modeling with Transformers' capacity to capture global patterns across related tasks [41]. This suggests hybrid approaches effectively combine GNNs' sample efficiency with Transformers' generalization capability.

Efficiency and Scalability Considerations

Computational efficiency represents a crucial practical consideration for real-world deployment:

Training Efficiency: Graph Transformers demonstrate significantly faster training times compared to GNNs (3.9 vs. 20.7 hours for 3D models), attributed to their parallelization capabilities and optimized attention implementations [39]. This advantage grows with dataset size, making Transformers increasingly attractive for large-scale molecular screening.

Inference Speed: Transformers maintain efficiency advantages during inference (0.4ms vs. 3.9ms for 3D models), though GNNs have closed the gap through optimized inference frameworks like GraphSAGE [44] [39]. For real-time virtual screening applications, this difference can become significant at scale.

Memory Requirements: Transformers typically require more parameters (1.61M vs. 0.11-1.24M for GNNs) and greater memory utilization, potentially limiting their application to extremely large molecules or high-throughput screening environments with hardware constraints [39].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Robust benchmarking requires standardized datasets, evaluation metrics, and training protocols to ensure fair comparisons:

Dataset Curation: Most comparative studies employ established molecular benchmarks including QM9 for quantum mechanical properties, NURA for nuclear receptor binding, and MoleculeNet for various biophysical and physiological properties [39] [41]. These datasets undergo rigorous preprocessing including duplicate removal, structural standardization, and scaffold splitting to assess generalization.

Splitting Strategies: Three data splitting approaches evaluate different generalization capabilities: random splits measure interpolative performance, scaffold splits assess generalization to novel chemotypes, and temporal splits simulate real-world prospective validation [37] [41].

Evaluation Metrics: Task-appropriate metrics include AUC-ROC for classification tasks, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression, and additional domain-specific metrics like F1 score for imbalanced data and Pearson R for correlation analysis [12] [41].

Model Training and Optimization

GNN Training Protocols: Modern GNN implementations typically use Adam or AdamW optimization with learning rate warmup and decay, gradient clipping, and early stopping [39]. Regularization techniques include dropout on node features, edge dropout, and stochastic depth. Hyperparameter optimization focuses on message-passing depth (typically 3-8 layers), hidden dimension (128-512), and aggregation function selection [37].

Transformer Training Protocols: Transformers employ similar optimizers but often require lower learning rates (1e-5 vs 1e-4 for GNNs) and larger batch sizes when possible [39]. Regularization includes attention dropout, hidden state dropout, and weight decay. Positional encoding strategies (learned, Laplacian eigenvectors, spatial distances) represent crucial hyperparameters requiring careful ablation [39].

Self-Supervised Pretraining: Both architectures benefit from self-supervised pretraining on large unlabeled molecular datasets (10M+ compounds) [37]. GNNs employ strategies like node masking, context prediction, and contrastive learning, while Transformers use masked token/language modeling objectives. BatmanNet's bi-branch masking approach demonstrates how reconstruction objectives can simultaneously capture local and global information [37].

Architectural Workflows

The workflow diagram illustrates three distinct pathways for molecular representation learning, highlighting key architectural differences and integration points. The GNN pathway (green) operates directly on molecular graphs, employing message-passing layers to capture local atomic environments before global readout functions generate molecular-level predictions. The Transformer pathway (blue) processes sequential representations (SMILES) through token and positional embedding layers, followed by encoder blocks that model global dependencies through self-attention. The Hybrid pathway combines features from both architectures, leveraging GNNs' structural awareness and Transformers' global context modeling through various fusion strategies [39] [37] [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential computational tools for molecular representation learning

| Tool Category | Representative Solutions | Primary Function | Architecture Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, PyTorch Geometric, TensorFlow | Model implementation and training | GNNs & Transformers |

| Molecular Representation | RDKit, OpenBabel, DeepChem | Molecular graph generation and featurization | GNNs & Transformers |

| GNN Libraries | PyTorch Geometric, DGL, GraphNets | GNN model implementations | GNNs |

| Transformer Libraries | Hugging Face Transformers, Graphormer | Transformer model implementations | Transformers |

| Benchmarking Suites | MoleculeNet, OGB, TDC | Standardized datasets and evaluation | GNNs & Transformers |

| Pretrained Models | MoleculeBERT, GROVER, Pretrained GNNs | Transfer learning starting points | GNNs & Transformers |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | Weights & Biases, Optuna, Ray Tune | Model optimization and experiment tracking | GNNs & Transformers |

| Visualization Tools | GNNExplainer, BertViz, RDKit | Model interpretability and explanation | GNNs & Transformers |

The comparative analysis between Encoder-Decoder Transformers and Graph Neural Networks reveals a nuanced landscape where architectural advantages manifest differently across molecular modeling tasks. GNNs maintain strengths in structure-aware prediction tasks with limited data, leveraging their inherent molecular inductive biases through localized message passing. Transformers excel in data-rich environments requiring global dependency modeling, particularly for quantum mechanical properties and complex binding interactions. Hybrid architectures increasingly demonstrate that combining these approaches yields synergistic benefits, outperforming either architecture alone across diverse benchmarks.

For researchers and drug development professionals, selection criteria should consider multiple factors: dataset size and diversity, target properties' dependence on local versus global molecular features, computational resources, and interpretability requirements. GNNs offer greater sample efficiency for small datasets and more intuitive structural interpretability, while Transformers provide superior scalability and representation power for complex, delocalized molecular interactions. The emerging class of hybrid models presents a promising path forward, potentially obviating the need for strict architectural dichotomies.

As foundation models continue to evolve in computational drug discovery, the distinction between architectural paradigms will likely blur further through cross-pollination of mechanisms. Attention-enhanced GNNs, structure-aware Transformers, and flexible hybrid frameworks represent the vanguard of molecular representation learning, moving the field closer to comprehensive in silico molecular design and optimization capabilities.